A Complete Guide to Paired-End RNA-seq Alignment with STAR: From Basics to Advanced Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step protocol for aligning paired-end RNA-seq reads using the Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) software. Tailored for researchers and scientists in drug development and biomedical research, it covers foundational concepts, detailed methodology, critical troubleshooting, and validation techniques. Readers will learn to perform both standard and advanced 2-pass mapping, optimize parameters for specific experimental goals like somatic mutation or fusion transcript detection, and interpret alignment outputs to ensure data quality for downstream differential expression and splicing analysis.

A Complete Guide to Paired-End RNA-seq Alignment with STAR: From Basics to Advanced Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step protocol for aligning paired-end RNA-seq reads using the Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) software. Tailored for researchers and scientists in drug development and biomedical research, it covers foundational concepts, detailed methodology, critical troubleshooting, and validation techniques. Readers will learn to perform both standard and advanced 2-pass mapping, optimize parameters for specific experimental goals like somatic mutation or fusion transcript detection, and interpret alignment outputs to ensure data quality for downstream differential expression and splicing analysis.

Understanding STAR: Why It's the Gold Standard for Spliced RNA-seq Alignment

The alignment of high-throughput sequencing reads to a reference genome represents a critical step in the analysis of both RNA-seq and DNA-seq data. This process enables crucial downstream analyses including gene discovery, gene quantification, splice variant analysis, and the identification of chimeric fusion genes [1]. RNA-seq data alignment presents unique computational challenges, primary among them being the accurate mapping of reads that span non-contiguous genomic regions—a consequence of the splicing mechanism that joins exons together in eukaryotic transcriptomes [2]. Traditional DNA-seq aligners, which assume sequence contiguity, are ill-suited for this task, necessitating the development of specialized "splice-aware" aligners.

Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) is a highly accurate and ultra-fast splice-aware aligner specifically designed to address the mapping challenges inherent to RNA-seq data [1] [2]. First introduced in 2012, STAR employs a novel alignment algorithm based on sequential maximum mappable seed search in uncompressed suffix arrays, followed by seed clustering and stitching procedures [2]. This strategy allows STAR to outperform other splice-aware RNA-seq aligners such as HISAT2 and TopHat2 in terms of mapping rate and speed, though it typically requires more substantial computational memory resources [1]. A key advantage of STAR is its high precision in identifying both canonical and non-canonical splice junctions, alongside its capability to detect chimeric transcripts and accurately map long reads generated by third-generation sequencing technologies [1] [2].

STAR Algorithm and Computational Strategy

Core Algorithmic Principles

The STAR algorithm operates through a two-step process that fundamentally differs from approaches used by earlier aligners. Rather than extending DNA-seq alignment methods, STAR was designed from the ground up to align non-contiguous sequences directly to the reference genome [2]. This core design principle enables its exceptional performance in handling spliced transcripts.

The first phase, seed searching, involves identifying the longest sequences from reads that exactly match one or more locations on the reference genome. For each read, STAR searches for the Maximal Mappable Prefix (MMP)—the longest substring starting from read position i that matches exactly one or more substrings of the reference genome G [2]. When a read contains a splice junction, it cannot be mapped contiguously; thus the first MMP maps to a donor splice site, and the algorithm sequentially searches the unmapped portion of the read to find the next MMP, which maps to an acceptor splice site [3] [2]. This sequential application of MMP search exclusively to unmapped read portions contributes significantly to STAR's computational efficiency.

The second phase, clustering, stitching, and scoring, involves reconstructing complete alignments by stitching together individually mapped seeds. Seeds are clustered based on proximity to selected "anchor" seeds—those with limited genomic mapping locations [2]. A dynamic programming algorithm then stitches seed pairs together within user-defined genomic windows, allowing for mismatches but only one insertion or deletion per seed pair [2]. This approach naturally accommodates paired-end reads by clustering and stitching seeds from both mates concurrently, treating them as pieces of the same sequence, which enhances alignment sensitivity [2].

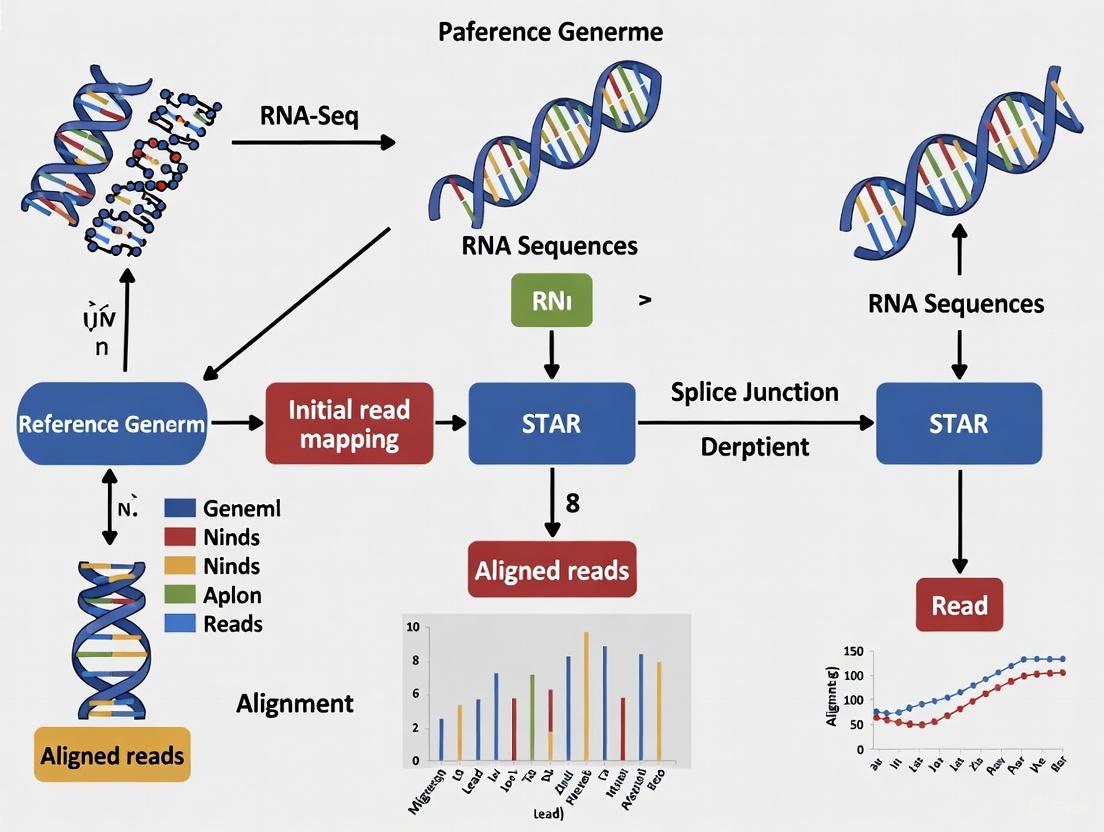

Visualizing the STAR Alignment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete STAR alignment workflow, from initial read processing to final output generation:

Key Algorithmic Advantages

STAR's algorithmic design provides several distinct advantages over traditional approaches. The use of uncompressed suffix arrays enables rapid searching with logarithmic scaling relative to reference genome size, allowing efficient processing even against large genomes [2]. The sequential MMP approach represents a more natural method for identifying splice junction locations compared to arbitrary read-splitting methods used in other aligners [2]. Furthermore, STAR detects splice junctions in a single alignment pass without requiring preliminary contiguous alignment or pre-existing junction databases, enabling unbiased de novo discovery of both canonical and non-canonical splice junctions [2].

The two-step mapping process also provides robustness against sequencing artifacts. When MMP extension fails due to poor sequence quality or adapter contamination, STAR can identify and soft-clip these problematic regions [3] [2]. This capability ensures that alignment quality remains high even with imperfect sequencing data.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Computational Requirements and Installation

STAR requires significant computational resources, particularly memory, for optimal performance. The following table outlines typical system requirements:

Table 1: STAR Computational Requirements for Human Genome Alignment

| Resource Type | Minimum Recommended | Optimal for Human Genome |

|---|---|---|

| RAM | 16 GB | 32 GB or higher |

| Processors | 4 cores | 8-12 cores |

| Storage | 100 GB free space | 500 GB free space |

| Operating System | Linux or Mac OS | Linux or Mac OS |

Installation can be accomplished either by downloading pre-compiled binaries or compiling from source [1]. For Linux systems, the following commands install STAR and add its binaries to the system path:

Genome Index Generation Protocol

STAR requires a genome index before read alignment can commence. The index generation protocol requires both a reference genome sequence in FASTA format and gene annotation in GTF or GFF3 format [1] [3].

Protocol Steps:

- Create a directory for genome indices:

mkdir /path/to/genome_indices - Execute the genomeGenerate run mode with appropriate parameters

- Verify index generation by checking for the presence of output files in the genome directory

The following command provides a template for genome index generation:

Table 2: Critical Parameters for Genome Index Generation

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Value |

|---|---|---|

--runThreadN |

Number of parallel threads to use | 6-12 (based on available cores) |

--genomeDir |

Path to directory for storing genome indices | User-defined directory path |

--genomeFastaFiles |

Reference genome file in FASTA format | Genome sequence file |

--sjdbGTFfile |

Gene annotation file in GTF format | Annotation file matching genome |

--sjdbOverhang |

Length of genomic sequence around annotated junctions | Read length minus 1 |

For read lengths of 150 bp, the --sjdbOverhang parameter should be set to 149, though the default value of 100 often produces similar results [1] [3]. When using GFF3 annotation files instead of GTF, an additional parameter --sjdbGTFtagExonParentTranscript Parent must be included to define parent-child relationships [1].

Read Alignment Protocol

With genome indices prepared, RNA-seq reads can be aligned using STAR's standard mapping mode. The protocol differs slightly for single-end versus paired-end reads.

For single-end reads:

For paired-end reads:

For compressed FASTQ files (.fastq.gz), include the parameter --readFilesCommand zcat or --readFilesCommand gunzip -c to enable on-the-fly decompression [1].

Table 3: Essential Parameters for Read Alignment

| Parameter | Description | Importance |

|---|---|---|

--readFilesIn |

Input read file(s) | Mandatory; specifies sequence data |

--genomeDir |

Path to genome indices | Mandatory; specifies reference |

--outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate |

Output sorted BAM format | Enables efficient downstream processing |

--outFileNamePrefix |

Output file name prefix | Organizes output files by sample |

--quantMode |

Gene-level quantification | Optional: outputs read counts per gene |

For studies focused on novel splice junction discovery or differential splicing analysis, a 2-pass mapping approach is recommended. This involves re-building genome indices using splice junctions identified in an initial mapping step, then repeating alignment with these enhanced indices [1].

Output Files and Interpretation

STAR Output File Types

A successful STAR alignment generates multiple output files, each containing different types of information about the alignment results.

Table 4: STAR Output Files and Their Contents

| Output File | Contents | Downstream Applications |

|---|---|---|

*Aligned.sortedByCoord.out.bam |

Coordinate-sorted alignments | Visualization, variant calling, transcript assembly |

*Log.final.out |

Summary alignment statistics | Quality control, experimental assessment |

*SJ.out.tab |

Filtered splice junction information | Splice junction analysis, novel junction discovery |

*ReadsPerGene.out.tab |

Read counts per gene | Differential expression analysis |

*Log.progress.out |

Alignment progress statistics | Performance monitoring, optimization |

The BAM file containing sorted alignments represents the primary output for most downstream analyses, including transcript assembly with StringTie and differential expression analysis with tools like DESeq2 [4]. The splice junction file (*SJ.out.tab) contains information about all detected junctions, including genomic coordinates, strand information, and annotation status [1].

Interpretation of Alignment Statistics

The *Log.final.out file provides comprehensive alignment statistics essential for quality assessment. The following table illustrates typical alignment rates from a successful experiment:

Table 5: Example STAR Alignment Statistics from Arabidopsis thaliana Data

| Metric | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Number of input reads | 11,889,751 | Total sequencing depth |

| Uniquely mapped reads | 90.48% | High-quality alignment rate |

| Average mapped length | 200.74 bp | Read length after trimming |

| Mismatch rate per base | 0.65% | Acceptable error rate |

| Multi-mapping reads | 6.55% | Reads mapping to multiple loci |

| Splice junctions detected | 7,206,200 | Total splice events |

A uniquely mapped reads percentage above 70-80% generally indicates successful alignment, though this varies by organism and RNA-seq library quality [1] [3]. The splice junction classification provides insights into splicing biology, with canonical GT/AG junctions typically representing the majority of splicing events [1].

Performance Comparison with Alternative Aligners

STAR versus Pseudoaligners

STAR is frequently compared with pseudoalignment tools like Kallisto, particularly in the context of single-cell and bulk RNA-seq analysis. The following table summarizes key differences:

Table 6: Feature Comparison Between STAR and Kallisto

| Feature | STAR | Kallisto |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm type | Splice-aware alignment to genome | Pseudoalignment to transcriptome |

| Accuracy | Higher gene detection rates [5] | Faster with slightly lower detection |

| Computational speed | Fast but memory-intensive | Extremely fast and lightweight |

| Memory usage | High (28GB reported) [6] | Low (3.6GB reported) [6] |

| Novel junction detection | Excellent for canonical and non-canonical | Limited to annotated transcripts |

| Input requirements | Genome sequence + annotations | Transcriptome sequence |

Research comparing these tools on single-cell RNA-seq data from Drop-seq, Fluidigm, and 10x Genomics platforms has demonstrated that STAR generally produces higher gene counts and greater alignment rates (62.40% versus 35.11% in Drop-seq data) [5] [6]. Additionally, STAR shows better correlation with RNA-FISH validation data, particularly for the Gini index, which measures expression distribution across cells [5].

Performance Optimization Strategies

Recent research has identified several strategies for optimizing STAR performance in high-throughput computing environments:

Genome Version Selection: Using newer Ensembl genome releases (e.g., release 111 versus 108) can dramatically reduce index size (85 GB to 29.5 GB) and decrease execution time by more than 12-fold while maintaining nearly identical mapping rates [7].

Early Stopping: Implementing an "early stopping" approach that terminates alignment if less than 30% of the initial read subset maps successfully can reduce total computation time by approximately 19.5% by filtering out low-quality samples early in the process [7].

Cloud-Native Architecture: Implementing STAR in scalable cloud environments using pre-computed indices and spot instances can significantly reduce computational costs while maintaining alignment accuracy for large-scale transcriptomic studies [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the STAR alignment protocol requires several key computational reagents and resources. The following table details these essential components:

Table 7: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Materials for STAR Alignment

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | GRCh38 (human), GRCm39 (mouse), Sorghum_bicolor (plant) | Genomic coordinate system for read alignment |

| Gene Annotation | GTF files from Ensembl, GENCODE, or RefSeq | Defines known gene models and splice junctions |

| Sequence Reads | FASTQ files (single or paired-end) | Raw sequencing data for alignment |

| Alignment Software | STAR (version 2.7.10b or newer) | Core alignment algorithm execution |

| Sequence Manipulation Tools | SAMtools, BEDTools, FASTQC | BAM file processing and quality control |

| Downstream Analysis Packages | StringTie, DESeq2, Ballgown | Transcript assembly and differential expression |

| Rubelloside B | Rubelloside B, MF:C42H66O14, MW:795.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dihydroniloticin | Dihydroniloticin, MF:C30H50O3, MW:458.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The quality and version compatibility of these resources significantly impact alignment success. Using matched versions of genome sequences and gene annotations from the same source (e.g., both from Ensembl release 111) prevents coordinate mismatches and ensures optimal junction annotation [7]. Regular updates to genome assemblies and annotations can improve alignment accuracy and reduce computational requirements.

Advanced Applications and Integration in Research Pipelines

Specialized Applications

STAR supports several advanced analysis modes that extend its utility beyond basic read alignment:

Two-Pass Mapping: For novel splice junction discovery, a two-pass approach first identifies junctions from initial alignment, then incorporates these junctions into the reference for a second alignment round, significantly improving sensitivity for unannotated splicing events [1].

Chimeric Alignment: STAR can detect chimeric (fusion) transcripts by identifying alignments where read segments map to different genomic loci, enabling discovery of gene fusions with important implications in cancer research [2].

Long Read Alignment: Although designed for short reads, STAR can accurately map long reads from third-generation sequencing technologies (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore), making it suitable for full-length transcriptome analysis [2].

Integration with Downstream Analysis Workflows

STAR aligns seamlessly into comprehensive RNA-seq analysis pipelines. A typical integrated workflow might include:

- Quality Control: FastQC for raw read assessment

- Alignment: STAR for genome mapping

- Transcript Assembly: StringTie for transcript model construction [4]

- Quantification: featureCounts or STAR's built-in quantMode for gene-level counts

- Differential Expression: DESeq2 or Ballgown for identifying expression changes [4]

This integration is exemplified in the nf-core/RNA-seq pipeline, which incorporates STAR as a primary aligner alongside comprehensive quality control metrics [8]. The output of STAR—particularly the coordinate-sorted BAM files and junction information—serves as input for diverse downstream applications including variant calling, differential splicing analysis, and visualization in genome browsers.

The following diagram illustrates STAR's role in a comprehensive RNA-seq analysis workflow:

STAR's position as a central component in modern RNA-seq analysis workflows underscores its importance in contemporary genomics research. Its balance of speed, accuracy, and versatility makes it particularly valuable for large-scale transcriptomic studies, including those conducted by major consortia such as ENCODE [2]. As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve, with increasing read lengths and throughput, STAR's unique algorithmic approach positions it to remain a cornerstone of transcriptome analysis for the foreseeable future.

The Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) software package represents a foundational tool in modern transcriptomics, specifically engineered to address the unique computational challenges of RNA-seq data analysis. In the context of paired-end RNA-seq alignment protocol research, STAR's algorithm provides a critical solution for mapping sequences derived from non-contiguous genomic regions, a task essential for accurate transcriptome reconstruction [2]. The strategic importance of STAR lies in its dual capacity for ultra-fast processing and high-sensitivity detection of complex RNA arrangements, enabling researchers to comprehensively analyze the full complexity of cellular transcriptomes. This capability is particularly valuable for drug development professionals investigating disease-specific transcriptional alterations, where discovering novel splice variants and fusion transcripts can reveal potential therapeutic targets.

STAR's performance advantages stem from its novel alignment strategy, which fundamentally differs from earlier approaches that treated RNA-seq alignment as an extension of DNA read mapping [2]. By directly addressing the non-contiguous nature of RNA transcripts, STAR achieves unprecedented mapping speed while maintaining accuracy—processing 550 million 2×76 bp paired-end reads per hour on a standard 12-core server, outperforming other aligners by more than a factor of 50 [2] [3]. This scalability is crucial for large consortia efforts and clinical studies where processing thousands of samples efficiently is paramount. Furthermore, STAR's ability to detect both canonical and non-canonical splices, chimeric (fusion) transcripts, and circular RNAs provides researchers with a comprehensive toolset for exploratory transcriptome analysis in both basic research and clinical applications [9].

Technical Breakdown of Key Advantages

Superior Mapping Rate and Speed

STAR achieves its exceptional mapping performance through an innovative two-step algorithm that maximizes both speed and accuracy. The first phase involves sequential searching for Maximal Mappable Prefixes (MMPs), defined as the longest subsequences from reads that exactly match one or more locations on the reference genome [2] [3]. This approach represents a natural way of identifying precise splice junction locations without prior knowledge of junction loci or properties. The sequential application of MMP search exclusively to unmapped portions of reads distinguishes STAR from other algorithms and underlies its significant speed advantage [2].

The technical implementation utilizes uncompressed suffix arrays (SAs), which provide logarithmic scaling of search time with reference genome length, enabling rapid searching against large genomes [2]. In benchmark comparisons, STAR demonstrates both high mapping sensitivity and precision, with typical mapping rates of 92-95% for human RNA-seq data [9] [3]. The algorithm's efficiency is further enhanced through parallel processing capabilities, allowing researchers to leverage multi-core computing architectures to accelerate analysis timelines—a critical advantage in time-sensitive drug discovery pipelines.

Table 1: Comparative Mapping Performance Metrics

| Performance Metric | STAR Performance | Typical Range for Other Aligners |

|---|---|---|

| Mapping Speed | 550 million PE reads/hour (12-core server) | <10 million PE reads/hour [2] |

| Mapping Rate | 92.2% (example from human RNA-seq) | 70-90% varies by aligner [9] [10] |

| Unique Mapping Rate | 92.2% | 80-95% varies by aligner [9] |

| Multi-Mapping Rate | 6.0% | 5-15% varies by aligner [9] |

| Unmapped Reads | 1.7% | 5-20% varies by aligner [9] |

Comprehensive Splice Junction Discovery

STAR excels in splice junction detection through its ability to identify both annotated and novel splice junctions without prior annotation. The algorithm accomplishes this by stitching separately mapped seeds across intronic regions, with the maximum intron size determined by user-defined genomic windows during the clustering phase [2]. This approach allows STAR to discover novel splice junctions de novo, a capability verified through experimental validation where 1960 novel intergenic splice junctions were confirmed with an 80-90% success rate using Roche 454 sequencing of RT-PCR amplicons [2].

The splice detection sensitivity is further enhanced when using paired-end reads, as seeds from both mates are clustered and stitched concurrently, with each paired-end read represented as a single sequence [2]. This principled utilization of paired-end information reflects the biological reality that mates are fragments of the same RNA molecule, increasing detection sensitivity particularly for junctions where only one mate provides strong alignment evidence. For optimal junction detection, STAR can utilize gene annotations in GTF format during genome indexing, significantly improving identification and accurate mapping across known splice junctions [9]. When annotations are unavailable, STAR's two-pass mapping method enables sensitive novel junction discovery by leveraging splice junctions detected in an initial mapping round to inform a second, more accurate alignment phase [9].

Splice Junction Discovery Workflow: STAR's two-phase algorithm for identifying splice junctions from RNA-seq reads.

Advanced Chimeric RNA Detection

STAR possesses unique capabilities for detecting chimeric RNA molecules, including fusion transcripts that result from chromosomal rearrangements—a phenomenon of particular interest in cancer research and biomarker discovery. The algorithm identifies chimeric alignments by searching for multiple genomic windows that collectively cover the entire read sequence, with different portions mapping to distal genomic loci, different chromosomes, or different strands [2]. This approach allows STAR to detect both internal chimeric junctions within single reads and chimeras where the junction falls between paired-end mates in the unsequenced portion of the RNA molecule [2].

The chimeric detection functionality enables researchers to identify fusion transcripts without additional specialized tools, streamlining analytical workflows. STAR can pinpoint precise locations of chimeric junctions in the genome, providing structural information essential for understanding the molecular consequences of genomic rearrangements [2]. This capability was demonstrated in the detection of BCR-ABL fusion transcripts in K562 erythroleukemia cells, a clinically relevant fusion in hematological malignancies [2]. For comprehensive chimeric detection, STAR includes dedicated options that can be enabled during alignment to systematically report chimeric alignments in separate output files [9].

Application Notes for Experimental Design

Recommended Protocols for Optimal Performance

To maximize STAR's performance advantages in paired-end RNA-seq studies, researchers should follow established best practices for experimental design and computational resource allocation. The quality of input RNA significantly impacts mapping outcomes, with recommendations for assessing RNA integrity number (RIN) and selecting appropriate RNA extraction protocols based on sample type [10]. For eukaryotic samples, researchers must choose between poly(A) selection and ribosomal RNA depletion, with poly(A) selection preferred for high-quality samples and rRNA depletion necessary for degraded samples or bacterial transcriptomes [10].

Library preparation considerations include the use of strand-specific protocols (such as the dUTP method) to preserve information about the transcribed strand, which is particularly valuable for identifying antisense transcripts and accurately quantifying overlapping genes [10]. Paired-end sequencing is strongly recommended over single-end approaches for comprehensive transcriptome characterization, as the additional information significantly enhances splice junction detection and novel isoform discovery [10]. Sequencing depth should be determined based on research objectives, with typical recommendations ranging from 20-50 million reads per sample for standard differential expression studies to 100 million reads or more for comprehensive isoform-level analysis [10].

Table 2: STAR Alignment Parameters for Different Research Applications

| Research Application | Critical STAR Parameters | Recommended Settings | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Gene Expression | --outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate --quantMode GeneCounts |

Sorted BAM, read counts per gene | Fast processing, lower memory |

| Novel Isoform Discovery | --twopassMode Basic --outSAMstrandField intronMotif |

Two-pass mapping, strand information | 2x computation time, higher sensitivity |

| Fusion Transcript Detection | --chimSegmentMin 15 --chimJunctionOverhangMin 15 |

Chimeric alignment enabled | Additional computation, specialized output |

| Clinical RNA-seq | --outFilterScoreMinOverLread 0.3 --outFilterMatchNminOverLread 0.1 |

Strict filtering, quality metrics | Balanced sensitivity/specificity |

| Long Read Analysis | --seedSearchStartLmax 20 --seedPerReadNmax 100000 |

Modified seed parameters | Adapted for emerging technologies |

Computational Requirements and Resource Planning

STAR's exceptional performance requires substantial computational resources, particularly during the genome indexing phase. Memory requirements scale with reference genome size, with approximately 10× genome size bytes needed—for example, ~30 GB for the human genome [9]. The developers recommend 32 GB of RAM for human genome alignments to ensure stable operation [9]. Disk space requirements are also significant, with >100 GB of free space recommended for storing output files, including alignment files, splice junction lists, and logging information [9].

For processing efficiency, STAR supports multi-threaded execution, with the number of threads specified using the --runThreadN parameter [9]. Optimal performance is achieved when this parameter matches the number of physical processor cores available, though some systems with efficient hyper-threading may benefit from increasing threads up to twice the number of physical cores [9]. In high-performance computing environments, researchers should request appropriate resources through job schedulers, typically specifying 6-12 cores and 32-64 GB of RAM for human transcriptome alignment [3].

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Genome Index Generation Protocol

The initial step in any STAR analysis involves generating genome indices, which must be completed before read alignment. This process requires the reference genome sequence in FASTA format and gene annotations in GTF format. The following protocol outlines the critical steps for creating optimized indices:

Necessary Resources:

- Reference genome FASTA file

- Gene annotation GTF file

- Computer with Unix/Linux/Mac OS X operating system

- Sufficient memory (≥ 30 GB for human genome)

- Adequate disk space (≥ 100 GB)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Create and navigate to a directory for genome indices:

- Execute the genome generation command:

The --sjdbOverhang parameter should be set to the maximum read length minus 1, with 100 being a standard value that works well in most cases [3]. For paired-end reads, this parameter should reflect the length of the read that aligns across the splice junction, which is typically the read length minus 1 [9]. The genome indexing process is computationally intensive but only needs to be performed once for each combination of reference genome and annotation set.

Basic Paired-End Read Alignment Protocol

Once genome indices are prepared, researchers can perform the actual read alignment. This protocol describes the essential mapping workflow for paired-end RNA-seq data:

Input Files Requirements:

- Paired FASTQ files (read 1 and read 2)

- Genome indices generated as described in Protocol 4.1

Alignment Command:

Critical Parameter Explanations:

--runThreadN 12: Utilizes 12 computational threads for parallel processing--readFilesCommand zcat: Specifies decompression for gzipped input files--outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate: Outputs alignment in coordinate-sorted BAM format--outSAMunmapped Within: Includes unmapped reads in the output BAM file--outSAMattributes Standard: Includes standard alignment attributes in output

This basic protocol generates a sorted BAM file suitable for downstream analysis, including transcript quantification and visualization. During execution, STAR provides progress updates through both real-time console output and the Log.progress.out file, which displays mapping statistics updated at regular intervals [9].

Two-Pass Mapping for Novel Junction Discovery

For applications requiring maximum sensitivity for novel splice junction detection, the two-pass mapping method provides enhanced performance:

Two-Pass Execution:

The two-pass approach first identifies splice junctions from the data itself, then incorporates these junctions into the genome index for a second, more sensitive alignment round [9]. This method is particularly valuable when analyzing samples with potentially novel splicing patterns, such as disease tissues or uncharacterized biological conditions. The additional computational requirements are substantial (approximately double the alignment time) but yield significantly improved sensitivity for detecting rare or novel splicing events.

STAR Paired-End RNA-seq Analysis Workflow: Complete workflow from raw sequencing data to analysis-ready outputs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for STAR RNA-seq Analysis

| Category | Item/Reagent | Specification/Version | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Materials | Quartet Reference RNA Samples | Multi-center study validated [11] | Cross-laboratory standardization and quality control |

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Controls | 92 synthetic RNAs [11] | Technical performance monitoring and quantification calibration | |

| High-Quality Total RNA | RIN >8.0, minimal degradation [10] | Optimal library preparation input material | |

| Library Preparation | Strand-Specific Kit | dUTP second strand method [10] | Preservation of strand information in sequencing reads |

| Poly(A) Selection Beads | mRNA enrichment protocol [10] | Focus on messenger RNA population | |

| Ribo-Depletion Reagents | rRNA removal protocol [10] | Comprehensive transcriptome including non-polyadenylated RNAs | |

| Computational Resources | Reference Genome | GRCh38/hg38 or current version | Alignment coordinate system and annotation basis |

| Gene Annotations | GTF format (e.g., Ensembl, GENCODE) | Splice junction guidance and feature quantification | |

| High-Performance Computing | 12+ cores, 32+ GB RAM [9] | Execution of memory-intensive alignment algorithms | |

| Software Tools | STAR Aligner | Version 2.4.1a or later [9] | Primary alignment engine with splice-aware capability |

| SAMtools | Version 1.17 or later [12] | BAM file processing and indexing utilities | |

| FastQC | Version 0.12.1 or later [12] | Raw read quality assessment and troubleshooting | |

| Trimmomatic or Cutadapt | Current versions [12] | Adapter trimming and read quality processing | |

| Fupenzic acid | Fupenzic acid, CAS:119725-20-1, MF:C30H44O5, MW:484.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Isohyenanchin | Isohyenanchin | High-purity Isohyenanchin for laboratory research. Investigate its mechanism and applications. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

STAR's combination of superior mapping rates, comprehensive splice junction discovery, and advanced chimeric RNA detection establishes it as a foundational technology in modern transcriptomics research. The algorithms and protocols detailed in this application note provide researchers with a robust framework for extracting maximum biological insight from paired-end RNA-seq data, particularly in contexts where novel transcript discovery and detection of complex RNA arrangements are research priorities.

As RNA-seq applications continue to evolve toward clinical implementation, quality assessment using appropriate reference materials like the Quartet samples becomes increasingly important, particularly for detecting subtle differential expression with diagnostic significance [11]. The ongoing development of long-read sequencing technologies presents new opportunities and challenges for alignment algorithms, and STAR's capacity to handle sequences of any length with moderate error rates positions it well for these emerging applications [9] [2].

For drug development professionals and clinical researchers, STAR's precision in identifying fusion transcripts and alternatively spliced isoforms provides critical capabilities for biomarker discovery and therapeutic target identification. By implementing the optimized protocols and quality control measures described in this application note, researchers can ensure the reliability and reproducibility of their RNA-seq analyses, ultimately accelerating the translation of transcriptomic discoveries into clinical applications.

Within the framework of a broader thesis on paired-end RNA-seq alignment, the selection of the STAR aligner (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) is often dictated by its superior speed and accuracy in handling spliced transcripts [13]. However, its significant computational demands necessitate careful planning to ensure successful and efficient analysis. This application note details the critical hardware preparations and experimental protocols required to execute a STAR-based RNA-seq workflow, specifically tailored for researchers and scientists in drug development who need to process large-scale genomic data. Proper resource allocation is not merely an administrative task; it is a fundamental prerequisite that underpins the validity and reliability of downstream differential expression and transcriptomic analysis.

Quantitative Hardware Requirements

The alignment of RNA-seq reads to a reference genome is one of the most computationally intensive steps in the entire bioinformatics pipeline. The requirements below are specifically curated for aligning human or other similarly sized mammalian genomes, which are the most common use cases in therapeutic and drug discovery research.

The following table synthesizes hardware recommendations for running the STAR aligner under different operational scales, from minimal viable operation to optimal performance for large-scale batch processing.

Table 1: Detailed hardware requirements for STAR RNA-seq alignment

| Component | Minimum Requirement | Recommended for Standard Use | Large-Scale/Batch Processing |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAM (Memory) | 16 GB for mammalian genomes [14] | 32 GB - 38 GB for human genome [15] [16] [14] | 48 GB - 64 GB+ [15] [17] |

| Processor (CPU) | 8-core processor [18] | 16-24 cores [18] | 8 vCPU per task/instance, modern CPU architecture recommended [17] |

| Storage | 500 GB - 1 TB SSD [15] [18] | 1 TB+ high-performance (NVMe) SSD [15] | Large-scale block storage (EBS), 550 GB+ per instance with high IOPS [17] |

| Key Considerations | Risk of failure due to insufficient memory. | Balance of cost and performance for most single-sample analyses. | Essential for parallel processing of multiple samples; older CPU models can significantly slow processing [17]. |

Analysis of Resource Utilization

- Memory (RAM): The primary driver of STAR's high memory usage is the need to load the entire reference genome index into memory. For the human genome, this index is approximately 30 GB in size [17]. The recommended 32-38 GB provides the necessary headroom for the operating system and other concurrent processes, ensuring stable alignment without memory allocation errors. Attempting to run STAR with less than the minimum required RAM will almost certainly result in job failure [14].

- Processor (CPU): STAR is designed to leverage multiple CPU cores effectively. While it can run on fewer cores, performance scales with increased core count, significantly reducing alignment time. It is critical to note that CPU architecture impacts performance; a benchmark study noted that older-generation CPUs available in some serverless configurations led to slower alignment times compared to modern EC2 instances [17].

- Storage: The use of Solid-State Drives (SSD) is strongly recommended over traditional hard drives due to the high I/O demands of reading FASTQ files and writing SAM/BAM outputs [15]. For a dataset of 100 human samples with ~21 million reads each, total storage needs will easily exceed 1 TB when accounting for raw data, intermediate files, and final results.

Experimental Protocols for Resource Management

This protocol assumes prior installation of STAR and preparation of the reference genome index.

- Hardware Allocation: Provision a computational node with at least 32 GB of RAM and 8 CPU cores. Ensure a minimum of 500 GB of free space on a high-speed (SSD) storage volume.

- Input File Preparation: Confirm that paired-end FASTQ files are available. STAR can directly read gzipped files (e.g.,

sample_1.fastq.gz,sample_2.fastq.gz), which saves disk space and I/O time [19]. - STAR Execution Command: Execute a standard alignment command. The

--runThreadNparameter should be set to the number of available CPU cores to maximize parallelization. - Monitoring and Validation: Monitor the system's resource usage (e.g., using

toporhtop) during the initial phase of alignment to verify that memory consumption is within expected limits. Check the generatedLog.final.outfile for alignment statistics and any reported errors.

Protocol: Reprocessing RNA-seq Data Without Realignment

For workflows that involve recalculating gene counts or re-running downstream QC without altering the alignment itself, a BAM reprocessing workflow can save substantial time and computational resources [16]. This is highly relevant for refining analyses in long-term research projects.

- Prerequisite: An initial pipeline run (e.g., using nf-core/rnaseq) must be executed with the

--save_align_intermedsflag, which preserves the genomic and transcriptomic BAM files [16]. - Samplesheet Generation: The pipeline will auto-generate a new samplesheet (e.g.,

samplesheet_with_bams.csv) that includes paths to the previously generated BAM files. - Reprocessing Execution: Launch the pipeline in reprocessing mode, specifying the

--skip_alignmentflag and providing the generated samplesheet. - Outcome: The pipeline will bypass the resource-intensive STAR alignment step and use the existing BAM files for all downstream quantification and quality control steps, drastically reducing compute time and resource consumption [16].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete STAR-based RNA-seq analysis workflow, highlighting the critical pathway and key decision points for resource management.

Diagram 1: STAR RNA-seq analysis workflow

This table details the key computational "reagents" and infrastructure components required for a successful STAR alignment project.

Table 2: Essential computational materials and resources

| Resource / Tool | Function & Application in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| STAR Aligner [14] | The core software for performing spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads to a reference genome. Its high speed comes with significant RAM requirements. |

| Reference Genome Index [17] | A pre-computed data structure from a reference genome (e.g., human GRCh38). For STAR, this is a ~30 GB file that must be loaded into RAM, defining the memory requirement. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) or Cloud Platform [15] [17] | Local computing clusters or cloud services (AWS EC2/ECS) are typically required to meet the memory and CPU demands for mammalian genomes, as standard desktop computers are often insufficient. |

| nf-core/rnaseq Pipeline [16] | A robust, community-maintained Nextflow pipeline that encapsulates the entire RNA-seq analysis, including STAR alignment, quantification, and QC, ensuring reproducibility. |

| Elastic Block Storage (EBS) / SSDs [17] | High-input/output (IOPS) block storage, crucial for handling the large volumes of data involved in reading FASTQ files and writing alignment outputs efficiently. |

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become a foundational tool in modern molecular biology and drug development, enabling comprehensive, genome-wide quantification of transcriptomes [20]. Unlike earlier methods like microarrays, RNA-seq provides finer resolution for dynamic expression changes and allows for the discovery of novel RNA species and splicing events [21]. A critical first step in the analysis of RNA-seq data is the accurate and efficient alignment of millions of short sequencing reads to a reference genome. The Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) software package performs this task with high levels of accuracy and speed, and is uniquely capable of detecting not only annotated and novel splice junctions but also more complex RNA sequence arrangements, such as chimeric and circular RNA [22]. This application note details the core two-step workflow of STAR—genome generation and read mapping—providing researchers and drug development professionals with detailed protocols for performing paired-end RNA-seq alignment within the context of advanced genomic research.

The STAR workflow is fundamentally structured around two primary stages. The first stage involves generating a genome index from a reference genome and annotation file. This index is not a simple lookup table; it is a highly efficient, pre-processed structure that stores the genomic sequences along with crucial junction information, enabling STAR to perform ultra-fast searching during the alignment phase. The second stage uses this custom-generated index to map the RNA-seq reads (typically in FASTQ format) to the reference genome. The process results in aligned read files (BAM) and various output files that can be used for downstream analyses such as differential gene expression, novel isoform reconstruction, and signal visualization [22].

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and data flow between these two core processes:

Step 1: Protocol for Genome Index Generation

The creation of a STAR genome index is a one-time per genome/annotation release pre-processing step. A well-constructed index is crucial for the speed and accuracy of the subsequent mapping.

Experimental Methodology

This protocol requires a reference genome sequence in FASTA format and a gene annotation file in GTF format. The genome is processed into a suffix array, and the annotations are used to create a database of known splice junctions, which STAR uses to guide the alignment of reads across intron boundaries.

Input Files:

genome.fa: Reference genome sequences.annotation.gtf: Gene annotations.

Computational Command:

Key Parameters for Index Generation

The --sjdbOverhang parameter should be set to the read length minus 1. For paired-end reads, this is based on the length of one read. The following table summarizes critical parameters and their functions.

Table 1: Key Parameters for STAR Genome Index Generation

| Parameter | Function | Typical Setting for Paired-End |

|---|---|---|

--runMode genomeGenerate |

Directs STAR to operate in genome index generation mode. | Mandatory |

--genomeDir |

Specifies the directory where the genome index will be stored. | User-defined path |

--genomeFastaFiles |

Provides the path to the reference genome FASTA file(s). | Path to genome.fa |

--sjdbGTFfile |

Provides the gene annotation file to generate splice junction database. | Path to annotation.gtf |

--sjdbOverhang |

Specifies the length of the genomic sequence around annotated junctions. | Read length - 1 (e.g., 99 for 100bp reads) |

Step 2: Protocol for Mapping RNA-seq Reads

Once the genome index is built, it can be used to map the RNA-seq reads from each sample. This protocol is designed for paired-end reads, which provide higher mapping accuracy and better resolution of splice junctions compared to single-end reads.

Experimental Methodology

This protocol takes paired-end FASTQ files and the previously generated genome index as input. STAR performs a two-pass alignment process by default, which significantly improves the detection of novel splice junctions.

Input Files:

sample_R1.fastq: Forward reads.sample_R2.fastq: Reverse reads.- Genome index (from Step 1).

Computational Command:

Key Parameters for Read Mapping

The following parameters control the mapping behavior and output format. Adjusting the number of threads (--runThreadN) can significantly speed up the process on multi-core systems.

Table 2: Key Parameters for STAR Read Mapping

| Parameter | Function | Typical Setting |

|---|---|---|

--genomeDir |

Path to the genome index directory created in Step 1. | Mandatory |

--readFilesIn |

Specifies the paths to the FASTQ files (forward, then reverse). | sample_R1.fastq sample_R2.fastq |

--runThreadN |

Number of parallel threads to use for the alignment. | Dependent on available CPU cores |

--outSAMtype |

Specifies the format of the alignment output. | BAM SortedByCoordinate |

--quantMode |

Directs STAR to output counts for gene expression analysis. | GeneCounts |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of the STAR workflow is predicated on the quality of its inputs. The following table details the essential "research reagents"—the data and software components—required for the featured protocol.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for the STAR Workflow

| Item | Function / Role in the Workflow | Technical Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | The canonical DNA sequence for the organism serves as the alignment template. | Source: Ensembl, UCSC, or NCBI. Must match the annotation file's version. |

| Gene Annotation (GTF) | Provides the coordinates of known genes, transcripts, and exon-intron boundaries. | Critical for guiding splice-aware alignment and quantifying gene-level counts. |

| RNA-seq Reads (FASTQ) | The raw data representing fragments of the transcriptome from the experimental sample. | For paired-end sequencing, two files (R1 and R2) are required per sample [20]. |

| STAR Software | The aligner software that executes the two-step genome generation and mapping workflow. | Open source, available for Unix, Linux, or Mac OS X systems [22]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Computational environment to run the analysis. | STAR is memory-intensive; genome generation for human requires ~32GB RAM [22]. |

| Rubiarbonol B | Rubiarbonol B, MF:C30H50O3, MW:458.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Coronarin B | Coronarin B, CAS:119188-38-4, MF:C20H30O4, MW:334.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integration in the Broader RNA-seq Analysis Context

The STAR alignment protocol is a central component in a larger RNA-seq data analysis pipeline. The outputs from STAR feed directly into multiple downstream applications crucial for biomedical research and drug development.

The following diagram maps STAR's role within the end-to-end analytical workflow, from raw data to biological insight:

As shown, the process begins with raw FASTQ files, which must first undergo quality control (QC) and adapter trimming using tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic to identify technical errors and remove low-quality sequences [20]. The cleaned reads are then passed to STAR for alignment. The resulting BAM files can be used for visualization of sequencing coverage and splice junctions, while the generated count matrix becomes the direct input for statistical analysis of differential gene expression (DGE) using specialized tools like DESeq2 or edgeR [20]. This entire workflow enables researchers to move from raw sequencing data to biologically interpretable results, such as identifying biomarker candidates for disease or targets for therapeutic intervention.

Step-by-Step Protocol: From Genome Indexing to Read Alignment

The initial and most critical computational step in a paired-end RNA-seq alignment protocol using the STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) aligner is the generation of a genome index. This process, executed with the --runMode genomeGenerate command, is not a simple formatting step but a fundamental preprocessing operation that constructs a comprehensive map of the reference genome. This map enables STAR's ultra-fast alignment algorithm, which is based on a strategy of searching for Maximal Mappable Prefixes (MMPs) and subsequently clustering, stitching, and scoring these seeds to generate accurate spliced alignments [3] [2]. For RNA-seq data, this index must be "splice-aware," meaning it incorporates known gene annotations to dramatically improve the accuracy of identifying non-contiguous alignments that span exon-intron boundaries [9] [10]. A properly constructed index is the cornerstone of the entire analysis, influencing the speed, sensitivity, and precision of all downstream results, from gene expression quantification to the discovery of novel splice variants and fusion transcripts [9] [2].

Building a genome index is a resource-intensive process. The primary consideration is RAM memory, as STAR loads the entire genome and its indices into memory during the build process. For complex genomes like human, this requires a substantial amount of memory.

- RAM Requirements: A minimum of 10 x the genome size in bytes is recommended. For the human genome (~3 GigaBases), this translates to approximately 30 GigaBytes of RAM, with 32 GB often recommended for safe operation [9]. In practice, failures in index generation, particularly for large genomes, are frequently due to insufficient RAM.

- Storage and Processing: The process requires sufficient disk space for the resulting index files, which are typically large, and benefits from multiple CPU cores to speed up computation [3] [9]. The table below summarizes the requirements for different genome examples.

Table 1: Example Genome Index Resource Requirements

| Organism | Genome Size (Approx.) | Recommended RAM | Index Directory Size (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human (chr1 only) | ~300 Mbp [3] | 16 GB [3] | Not Specified |

| Human (full) | ~3 Gbp [9] | 30-32 GB [9] | ~30 GB [17] |

| Drosophila | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Input Data Preparation

The genome indexing process requires two primary input files.

- Reference Genome Sequence: A reference genome file in FASTA format (e.g.,

Homo_sapiens.GRCh38.dna.primary_assembly.fa). The file must be uncompressed for STAR to process it [23]. If downloaded in a compressed format (e.g.,.gz), usegunziporzcatto decompress it. - Gene Annotation File: A gene annotation file in GTF or GFF format (e.g.,

Homo_sapiens.GRCh38.92.gtf). This file provides the coordinates of known exons, introns, and genes, which STAR uses to create a database of splice junctions [3] [9]. This file must also be uncompressed.

Command-Line Execution

The following protocol outlines the step-by-step process for generating the genome index.

- Create an Output Directory: First, create a dedicated directory to store the genome indices. It is best practice to use scratch space with large temporary storage capacity if available [3].

- Execute the Genome Generate Command: Run the STAR command with the

genomeGenerateparameters. The following example uses a SLURM job submission script for use on a high-performance computing (HPC) cluster. - Clean Up: After successful index generation, remember to remove the uncompressed FASTA and GTF files if they were created temporarily, to save disk space [23].

The workflow for this entire process is summarized in the following diagram:

Critical Parameters and Optimization

Understanding the key parameters is essential for generating an optimal genome index.

Table 2: Critical Parameters for STAR Genome Index Generation

| Parameter | Function and Explanation | Recommended Setting |

|---|---|---|

--runThreadN |

Number of CPU cores to use for parallel processing. | Match to available physical cores (e.g., 6) [3]. |

--runMode |

Specifies the operation mode; must be set to genomeGenerate. |

genomeGenerate |

--genomeDir |

Path to the directory where the genome indices will be stored. | User-defined directory path. |

--genomeFastaFiles |

Path(s) to the reference genome FASTA file(s). | Path to your .fa file(s). |

--sjdbGTFfile |

Path to the annotation file in GTF format. | Path to your .gtf file [3] [9]. |

--sjdbOverhang |

Specifies the length of the genomic sequence around annotated junctions to be indexed. | Read length minus 1 [3] [23]. For 100bp PE, use 99 [3]. For 51bp PE, use 50 [23]. If unsure, a default of 100 is often suitable [3]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function in Protocol | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | The DNA sequence against which RNA-seq reads are aligned. | Ensure version compatibility with the GTF annotation file (e.g., GRCh38). |

| Gene Annotation (GTF) | Provides coordinates of known genes and splice sites for splice-aware indexing. | Use a version that matches the reference genome. Sources include Ensembl, GENCODE [23]. |

| STAR Aligner | The software package that performs the genome indexing and subsequent read alignment. | Download the latest release from the official GitHub repository [9]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Environment | Provides the necessary computational power, memory, and storage for index generation. | Requires Unix/Linux OS, ~30 GB RAM for human genome, and sufficient disk space [9]. |

| Methyl 2-amino-2-(2-chlorophenyl)acetate | Methyl 2-amino-2-(2-chlorophenyl)acetate, CAS:141109-13-9, MF:C9H10ClNO2, MW:199.63 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Koumine N-oxide | Koumine N-oxide, MF:C20H22N2O2, MW:322.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting and Validation

A successful index generation run will conclude with a log message such as "..... finished successfully" [23]. The primary output is the directory specified by --genomeDir, which will be populated with numerous files (e.g., Genome, SA, SAindex, chromosome-specific files, and junction information files). It is important to note that many of these files are for STAR's internal use and do not require direct interpretation by the researcher [24]. The most reliable validation of the index is its subsequent successful use in a mapping job. If the alignment step runs without errors and produces expected mapping statistics, the index has been built correctly.

Essential Parameters for Genome Indexing ('--sjdbOverhang', '--genomeDir')

In paired-end RNA-seq analysis, the STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) aligner employs a sophisticated two-step process where genome indexing is the critical first step that enables efficient subsequent read mapping [3]. The indexing process creates a pre-computed reference structure that allows STAR to rapidly identify potential mapping locations for sequencing reads, accounting for challenges specific to RNA-seq data, particularly splicing events where exons can be separated by large introns [3]. Proper configuration of the --sjdbOverhang and --genomeDir parameters during this indexing phase is fundamental to the success of the entire alignment workflow, directly impacting mapping sensitivity, accuracy, and computational efficiency [23] [25].

Parameter Deep Dive: --genomeDir and --sjdbOverhang

The --genomeDir Parameter

The --genomeDir parameter specifies the path to the directory where STAR will store and access the generated genome indices. This directory must be created before running the genome generation step and requires sufficient storage space for the index files, which are typically several tens of gigabytes for mammalian genomes [3] [14].

Key considerations for --genomeDir:

- Storage Location: For computational efficiency, particularly with large datasets, place this directory on storage with high I/O throughput [26].

- Memory Mapping: During alignment, STAR loads portions of the index from this directory into memory, making accessible storage crucial for runtime performance [26].

- Path Specification: The same

--genomeDirpath must be provided during both the genome generation and alignment steps [3].

The --sjdbOverhang Parameter

The --sjdbOverhang parameter defines the length of the genomic sequence around annotated splice junctions to be included in the genome index. This "overhang" allows STAR to effectively map reads that cross splice junctions, with the optimal value being read length minus 1 [3] [23].

Calculation and Default Behavior:

The parameter significantly affects splice junction detection. For diverse read lengths, the recommended approach is setting --sjdbOverhang to max(ReadLength)-1 [23] [27]. If unspecified during genome generation with annotations, STAR applies a default value of 100 [25].

Table 1: sjdbOverhang Configuration for Common Read Lengths

| Read Length | Recommended sjdbOverhang | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 51 bp | 50 | Optimal for maximum sensitivity [23] |

| 76 bp | 75 | Standard for shorter paired-end reads |

| 101 bp | 100 | Common default value [25] |

| 151 bp | 150 | Suitable for longer paired-end reads [27] |

| Variable lengths | max(ReadLength)-1 | Recommended for multiple read lengths [27] |

Critical Implementation Constraint: The --sjdbOverhang value must be identical during genome generation and alignment when using pre-indexed annotations. Mismatched values will cause fatal errors [25] [27]. For flexibility with varying read lengths, build the genome index without annotations, then supply the GTF file and --sjdbOverhang during alignment for "on-the-fly" junction inclusion [25].

Experimental Protocol for Genome Indexing

Computational Requirements and Setup

STAR genome indexing is computationally intensive, particularly for mammalian genomes. The following resources are recommended:

Table 2: Computational Requirements for Mammalian Genomes

| Resource | Minimum Requirement | Recommended |

|---|---|---|

| RAM | 16 GB | 32 GB or more [14] |

| CPU Cores | 4-6 | 8+ for faster execution [3] |

| Storage | Sufficient for ~30GB index | High I/O throughput storage [26] |

Software Installation: STAR can be compiled from source or installed via package managers:

Step-by-Step Indexing Protocol

Step 1: Prepare Reference Files

- Obtain genome sequence (FASTA) and annotation (GTF) files from Ensembl or GENCODE

- Ensure chromosome naming consistency between FASTA and GTF files

- Decompress files if necessary:

zcat Homo_sapiens.GRCh38.dna.chromosome.10.fa.gz > genome.fa[23]

Step 2: Create Genome Directory

Step 3: Execute Genome Generation

Critical Parameters Explained:

--runThreadN 8: Number of parallel threads to use [3]--runMode genomeGenerate: Specifies genome indexing mode [3] [23]--genomeDir /path/to/STAR_index: Output directory for indices [3]--genomeFastaFiles /path/to/genome.fa: Input genome sequence [3] [23]--sjdbGTFfile /path/to/annotations.gtf: Gene annotation file [3] [23]--sjdbOverhang 99: Optimal for 100bp reads (100-1=99) [3]

Quality Assessment and Verification

After completion, verify successful index generation by checking for these key files in the --genomeDir directory:

Genome: Binary genome sequenceSA: Suffix arraysjdbInfo.txt: Splice junction database information

Check the log file for successful completion message: "finished successfully" [23].

Integration with Downstream Alignment

Workflow Integration

The genome indexing step directly enables the subsequent read alignment process. Once indexing is complete, the same --genomeDir path is provided to STAR during alignment:

Visualization of the STAR Alignment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete STAR alignment workflow, highlighting the critical role of genome indexing with proper parameter configuration:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources for STAR Genome Indexing

| Resource Type | Specific Solution | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | ENSEMBL (Homosapiens.GRCh38.dna.primaryassembly.fa) | Genomic sequence for read alignment [3] |

| Gene Annotation | GENCODE (gencode.v29.annotation.gtf) | Gene models for splice junction identification [23] |

| Compute Infrastructure | AWS EC2 instances (memory-optimized) | High-RAM computational environment [26] |

| Container Platform | Docker/Singularity | Environment reproducibility for alignment [26] |

| Quality Control | RSeQC, Qualimap | Post-alignment quality assessment [28] |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Implementation Issues

- sjdbOverhang Mismatch Error: If encountering "present --sjdbOverhang=XX is not equal to the value at the genome generation step =YY", ensure consistent values or rebuild the index [25] [27].

- Insufficient Memory: For mammalian genomes, allocate at least 32GB RAM to prevent crashes during indexing [14].

- Storage Considerations: Genome indices require significant storage (~30GB for human); ensure adequate space in

--genomeDirlocation [26].

Performance Optimization Strategies

- Parallel Processing: Use 6-8 threads (

--runThreadN) to reduce indexing time [3]. - Reference Optimization: For large-scale processing, consider distributing pre-built indices to compute nodes to avoid redundant indexing [26].

- Cloud Optimization: On AWS, memory-optimized instances (r-series) provide cost-efficient indexing performance [26].

The alignment of high-throughput sequencing reads to a reference genome is a critical step in RNA-seq data analysis [1]. For paired-end RNA-seq data, this process involves determining the precise genomic origins of millions of short sequence read pairs derived from fragmented RNA transcripts. The Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) software package addresses the unique challenges of RNA-seq mapping through a novel algorithm that enables ultra-fast and accurate alignment of spliced sequences [2] [29]. STAR's ability to detect both annotated and novel splice junctions, combined with its capacity to identify complex RNA arrangements such as chimeric and circular RNAs, makes it particularly suitable for comprehensive transcriptome studies in biomedical and drug development research [9].

Unlike DNA-seq alignment, RNA-seq alignment must account for non-contiguous genomic regions resulting from RNA splicing. Traditional aligners designed for DNA sequences often fail to identify splice junctions accurately, leading to substantial information loss. STAR employs an uncompressed suffix array-based searching method followed by a clustering/stitching procedure that allows it to precisely map reads across intron boundaries without relying exclusively on existing transcript annotations [2]. This capability is especially valuable for drug development professionals investigating novel transcripts or splicing variants that may serve as therapeutic targets or biomarkers.

Theoretical Foundation of the STAR Algorithm

The STAR alignment algorithm operates through two principal phases: seed searching followed by clustering, stitching, and scoring [2]. During the seed search phase, STAR identifies the Maximal Mappable Prefix (MMP)—the longest substring from the read start that matches exactly to one or more genomic locations. When a read contains a splice junction, the initial MMP maps to the donor splice site, and the algorithm repeats the search on the unmapped portion, which typically maps to an acceptor splice site. This sequential MMP search provides a natural mechanism for pinpointing splice junction locations without prior knowledge of junction databases.

In the second phase, STAR clusters the aligned seeds by genomic proximity and stitches them together using a dynamic programming approach that allows for mismatches and small indels [2]. For paired-end reads, seeds from both mates are processed concurrently, significantly enhancing alignment sensitivity. This approach treats paired-end reads as fragments of the same RNA molecule, allowing accurate alignment even when only one mate contains a reliable anchor sequence.

Table 1: Key Algorithmic Features of STAR for Paired-End RNA-seq Alignment

| Algorithmic Feature | Description | Advantage for Paired-End RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Maximal Mappable Prefix (MMP) Search | Identifies longest exact matches between read segments and reference genome | Enables detection of novel splice junctions without prior annotation |

| Sequential MMP Application | Repeatedly searches unmapped portions of reads after each MMP identification | Naturally identifies precise splice junction locations in a single alignment pass |

| Seed Clustering & Stitching | Groups aligned seeds by genomic proximity and connects them via dynamic programming | Allows comprehensive alignment of reads spanning multiple exons with small indels/mismatches |

| Concurrent Mate Processing | Processes both paired-end mates together during clustering/stitching | Increases sensitivity; one reliable mate can guide alignment of the entire fragment |

| Two-Pass Mapping Mode | Uses splice junctions discovered in first pass to inform second alignment pass | Enhances accuracy for novel junction detection without increasing false positive rate |

Computational Requirements and Resource Planning

Effective utilization of STAR requires careful consideration of computational resources, particularly for large-scale studies in pharmaceutical development environments. STAR's memory footprint is substantial due to its use of uncompressed suffix arrays, which trade memory usage for significant speed advantages [2] [9]. For the human genome (approximately 3 gigabases), STAR requires ~30GB of RAM, making 32GB a recommended minimum [9]. Smaller genomes such as mouse or rat require proportionally less memory, while plant genomes with high repetitive content may need additional resources.

STAR efficiently utilizes multiple processor cores, with alignment speed scaling nearly linearly with core count up to physical processor limits [9]. A modest 12-core server can align approximately 550 million 2×76 bp paired-end reads per hour [29], though hyper-threading can sometimes provide additional speed improvements. Disk space requirements are substantial, with output files for large datasets often exceeding 100GB, particularly when storing intermediate files and multiple alignment formats [9].

Table 2: Computational Requirements for STAR with Different Genome Sizes

| Resource Type | Human Genome (3GB) | Mouse Genome (2.7GB) | Arabidopsis (120MB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended RAM | 32GB | 28GB | 8GB |

| Disk Space for Index | ~30GB | ~27GB | ~4GB |

| Typical Alignment Speed | 550M reads/hour (12 cores) | 600M reads/hour (12 cores) | >1B reads/hour (12 cores) |

| Output File Space | 100-500GB | 90-450GB | 20-100GB |

Experimental Protocol: Genome Index Generation

Preparation of Reference Files

Before generating genome indices, researchers must obtain reference genome sequences and annotation files. The reference genome should be in FASTA format (uncompressed), while annotations can be in GTF or GFF3 format [1]. For GFF3 files, additional parameters are required to define parent-child relationships between exons and transcripts [1]. For drug development studies, using comprehensive annotations from sources such as GENCODE (human) or Ensembl is recommended, as these include protein-coding genes, non-coding RNAs, and pseudogenes that may be relevant to disease mechanisms.

Index Generation Command

The following protocol generates a genome index for the human GRCh38 assembly:

Critical Parameters:

--genomeDir: Directory where genome indices will be stored [1]--genomeFastaFiles: Reference genome FASTA file(s) [1]--sjdbGTFfile: Gene annotation file in GTF format [1]--sjdbOverhang: Length of genomic sequence around annotated junctions [9]; should be set to read length minus 1 [1]--runThreadN: Number of parallel threads to use [1]--genomeSAindexNbases: Length of the suffix array index; must be scaled down for small genomes [30]--genomeChrBinNbits: Scaling parameter for genomes with many contigs [30]

For non-model organisms or those with limited annotations, the --sjdbGTFfile parameter can be omitted, though this may reduce junction detection accuracy. In such cases, two-pass mapping is strongly recommended [9].

Figure 1: Genome Index Generation Workflow

Experimental Protocol: Mapping Paired-End Reads

Basic Mapping Protocol

The fundamental protocol for aligning paired-end RNA-seq reads assumes prior genome index generation and quality-checked FASTQ files. The example below processes paired-end reads from a typical drug treatment experiment:

Critical Mapping Parameters:

--readFilesIn: Specifies paired-end read files (read1 then read2) [1]--readFilesCommand: Uncompression command for compressed inputs (zcatfor .gz,bzcatfor .bz2) [1]--outSAMtype: Output format;BAM SortedByCoordinateenables direct use in downstream analysis [1]--outFileNamePrefix: Output file naming convention [1]--outFilterType BySJout: Reduces spurious alignments using junction information [31]--outSAMstrandField intronMotif: Adds strand information for transcript assembly [31]

Two-Pass Mapping for Novel Junction Discovery

For studies investigating novel splicing events or working with non-model organisms where annotation is limited, two-pass mapping significantly improves sensitivity:

Two-pass mapping does not substantially increase the number of detected novel junctions but improves the alignment of reads containing these junctions [31]. This approach is particularly valuable in cancer research or toxicology studies where alternative splicing may reveal disease mechanisms or drug effects.

Figure 2: Two-Pass Mapping Workflow

Output Interpretation and Quality Assessment

Output Files and Their Applications

STAR generates multiple output files that serve different purposes in downstream analysis:

- Aligned Reads (BAM):

*Aligned.sortedByCoord.out.bamcontains coordinate-sorted alignments suitable for variant calling, visualization, and read counting [1] - Junction File:

*SJ.out.tablists detected splice junctions with genomic coordinates and strand information [1] - Alignment Statistics:

*Log.final.outprovides comprehensive mapping summary statistics [1] - Progress Log:

*Log.progress.outenables real-time monitoring of large mapping jobs [9]

Interpretation of Alignment Metrics

The Log.final.out file contains critical quality metrics that researchers should evaluate before proceeding to differential expression analysis:

Table 3: Key Alignment Metrics and Their Interpretation

| Metric | Optimal Range | Biological/Technical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Uniquely Mapped Reads | >70% for complex genomes | Lower percentages may indicate contamination, poor RNA quality, or excessive PCR duplicates |

| Splice Junction Detection | High percentage annotated for well-annotated organisms | Increased novel junctions may indicate alternative splicing or insufficient annotation |

| Canonical Splice Sites | >95% of junctions | Non-canonical sites may indicate technical artifacts or biologically relevant non-canonical splicing |

| Mismatch Rate | <1% with reference genomes | Elevated rates may indicate poor sequencing quality, genetic variation, or incorrect reference |

| Multi-Mapping Reads | Variable by genome complexity | Higher in repetitive regions; may be filtered or handled probabilistically in quantification |

| Insertion/Deletion Rates | <0.1% | Elevated rates may indicate sequencing errors or alignment artifacts |

Table 4: Essential Resources for Paired-End RNA-seq Alignment with STAR

| Resource Category | Specific Example | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | GRCh38 (human), GRCm39 (mouse) | Provides genomic coordinate system for alignment and annotation |

| Gene Annotation | GENCODE, Ensembl GTF | Defines known gene models and splice junctions for guided alignment |

| Quality Control Tools | FastQC, fastp, Trim Galore | Assesses read quality and performs adapter trimming prior to alignment [32] |

| Alignment Software | STAR (v2.7.9a or newer) | Performs splice-aware alignment of RNA-seq reads [33] |

| Sequence Visualization | IGV, UCSC Genome Browser | Enables visual inspection of aligned reads and splicing patterns |

| Downstream Analysis | featureCounts, HTSeq, RSEM | Quantifies reads per gene for differential expression analysis [34] |

| Computational Environment | High-performance computing cluster | Provides necessary memory and processing resources for large datasets |

Advanced Applications in Drug Development Research

STAR's alignment capabilities enable several advanced applications particularly relevant to pharmaceutical research and development. The detection of chimeric (fusion) transcripts can identify oncogenic drivers in cancer studies [2], while comprehensive splice junction analysis can reveal alternative splicing patterns induced by drug treatments or disease states. For quantitative transcriptomics, STAR alignments can be processed by tools like RSEM or Cufflinks to estimate transcript abundances [9], providing crucial data for biomarker discovery and mechanism of action studies.

In large-scale drug screening applications, STAR's speed becomes particularly valuable. The ability to process hundreds of millions of reads per hour on modest computing infrastructure enables rapid turnaround from sequencing to expression analysis [29]. This throughput advantage facilitates time-course studies of drug response or large cohort analyses where dozens or hundreds of samples require processing.

For specialized applications in immuno-oncology or host-pathogen interactions, researchers can employ modified alignment strategies that combine human and pathogen references in a single index. This approach enables simultaneous quantification of host response genes and pathogen transcriptomes from infection models, providing comprehensive insights into drug effects on integrated biological systems.