A Comprehensive Guide to ChIP-Seq Data Analysis for Histone Modifications: From QC to Chromatin State Annotation

This article provides a complete workflow for analyzing ChIP-seq data focused on histone modifications, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to ChIP-Seq Data Analysis for Histone Modifications: From QC to Chromatin State Annotation

Abstract

This article provides a complete workflow for analyzing ChIP-seq data focused on histone modifications, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational concepts of histone mark biology and epigenomics, a step-by-step methodological pipeline from quality control to peak calling and annotation, essential troubleshooting and optimization strategies for common pitfalls, and finally, rigorous validation and comparative analysis techniques. By integrating current best practices and standards from consortia like ENCODE, this guide empowers scientists to reliably interpret the epigenomic landscape and its implications in gene regulation and disease.

Understanding Histone Modifications and Epigenomic Landscapes

Histone modifications are post-translational modifications (PTMs) of histone proteins that serve as fundamental epigenetic mechanisms for regulating gene expression and chromatin structure in eukaryotes [1]. These modifications occur on the core histone proteins (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) that form the nucleosome octamer around which DNA is wrapped [2]. The N-terminal tails of histones, which protrude from the nucleosome core, are particularly rich sites for modifications that alter chromatin accessibility and serve as binding platforms for downstream effector proteins [1] [3].

These PTMs play pivotal roles in various cellular processes including transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, DNA replication, and genome stability maintenance [1] [3]. The combinatorial nature of histone modifications creates a complex "histone code" that can be interpreted by reader proteins to elicit specific chromatin states and functional outcomes [1] [2]. Irregularities in histone PTMs are increasingly recognized as contributors to various diseases, including cancer, degenerative disorders, and abnormal developmental phenotypes [4] [5].

Major Types of Histone Modifications and Their Functions

Common Histone Modification Types

Histone modifications encompass a diverse array of chemical groups that can be added or removed from specific amino acid residues. The major types include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, among others [5]. The CHHM database, a manually curated catalogue of human histone modifications, documents 31 distinct types of modifications plus histone-DNA crosslinks, identified across numerous histone variants [2].

The functional consequence of each modification depends on both the specific residue modified and the type of modification installed. For example, methylation can have either activating or repressive effects depending on the position of the methylated residues and the degree of methylation (mono-, di-, or tri-methylation) [1]. Acetylation generally counteracts the positive charge of lysine residues, leading to a more open chromatin structure [4].

Genomic Distributions and Biological Functions

Table 1: Major Histone Modifications, Their Genomic Distributions and Biological Functions

| Modification | Associated Chromatin State | Primary Genomic Location | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Euchromatin | Promoter regions [6] | Transcriptional activation [1] |

| H3K4me1 | Euchromatin | Enhancer regions [6] | Enhancer identification [2] |

| H3K9me3 | Constitutive Heterochromatin | Repetitive regions, TE-rich regions [1] [7] | Transcriptional repression, TE silencing [1] [5] |

| H3K27me3 | Facultative Heterochromatin | Promoters of developmentally regulated genes [1] [6] | Developmental gene regulation [1] [5] |

| H3K27ac | Active Regulatory Elements | Enhancers and promoters [8] | Active enhancer marking [8] |

| H3K36me3 | Transcriptionally Active Regions | Gene bodies of actively transcribed genes [3] [6] | Transcriptional elongation [6] |

| H3K9ac | Euchromatin | Promoter regions [6] | Transcriptional activation [6] |

The genome is broadly divided into euchromatin (less compact, transcriptionally active) and heterochromatin (condensed, transcriptionally repressive), with distinct histone modifications characterizing each state [3]. Euchromatin is typically enriched with histone acetylation and H3K4 methylation, while heterochromatin is marked by H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 [3]. Recent research has revealed further complexity within these broad categories, identifying distinct subcompartments such as K4-facultative heterochromatin (adjacent to euchromatin) and K9-facultative heterochromatin (adjacent to constitutive heterochromatin), each with unique functional properties [1].

Figure 1: Functional Consequences of Major Histone Modifications. Histone modifications alter chromatin structure and recruit effector proteins to drive specific functional outcomes.

Histone Modification Analysis by ChIP-Seq

ChIP-Seq Workflow and Methodology

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is the method of choice for genome-wide analysis of histone modifications [6] [9]. This technique provides a snapshot of histone-DNA interactions in a given cell type, developmental stage, or disease condition [6]. The standard ChIP-seq workflow involves multiple critical steps:

Crosslinking and Cell Lysis: Proteins are crosslinked to their genomic DNA substrates in living cells using formaldehyde. Cells are then lysed to release chromatin [6].

Chromatin Fragmentation: Chromatin is fragmented to mononucleosome-sized fragments, typically by sonication or micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion. Sonication is preferred for mapping transcription factors, while MNase digestion results in more uniform mono-nucleosome sized fragments and higher resolution for histone modifications [10].

Immunoprecipitation: Specific histone modifications are precipitated using validated antibodies. The quality and specificity of antibodies are critical factors for successful ChIP-seq experiments [7] [6].

Library Preparation and Sequencing: After reversal of crosslinks, the ChIP DNA is purified and used to prepare sequencing libraries. The Illumina platform is most commonly used for ChIP-seq studies [6].

Data Analysis: Sequence reads are aligned to a reference genome, and enriched regions are identified using peak-calling algorithms. For histone modifications with broad domains like H3K27me3 and H3K9me3, specialized algorithms such as SICER or ChromaBlocks are required [10].

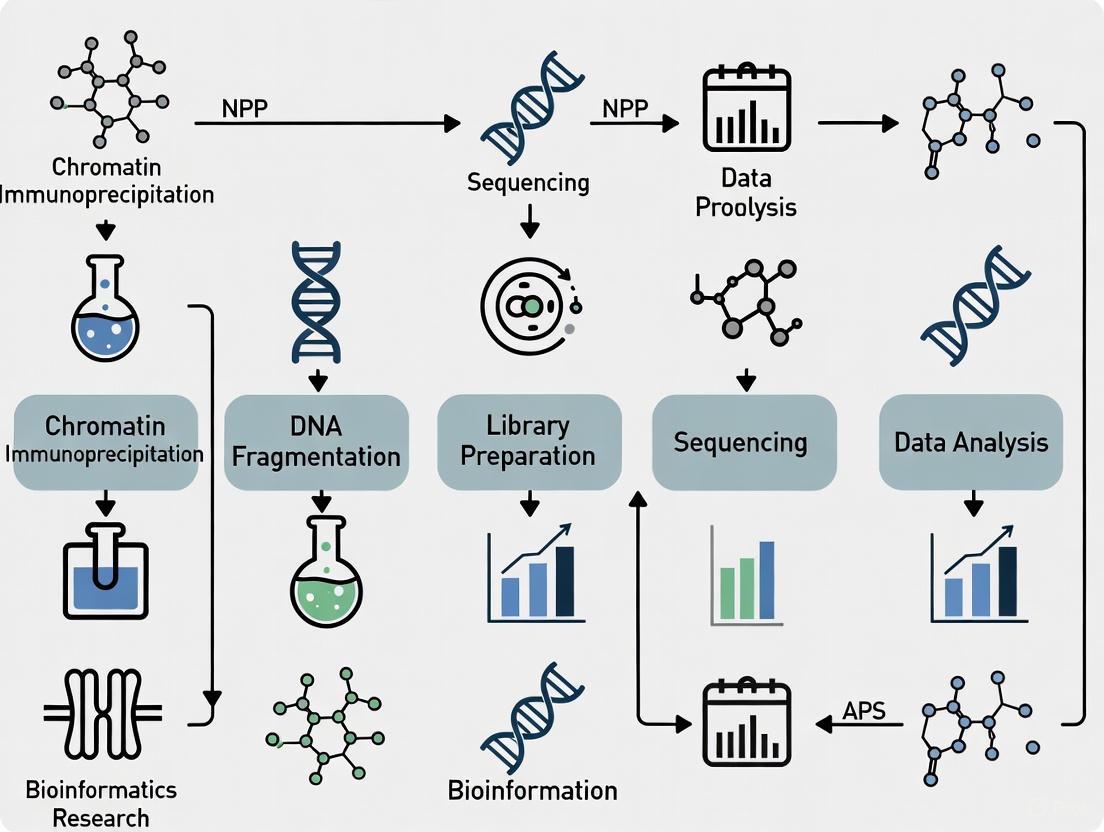

Figure 2: ChIP-seq Experimental Workflow. Key steps in the ChIP-seq protocol for mapping histone modifications genome-wide.

ChIP-Seq Standards and Quality Control

The ENCODE consortium has established comprehensive standards for ChIP-seq experiments to ensure data quality and reproducibility [7]. Key standards include:

- Biological Replicates: Experiments should include two or more biological replicates [7].

- Antibody Validation: Antibodies must be thoroughly characterized according to ENCODE standards [7].

- Input Controls: Each ChIP-seq experiment should have a corresponding input control with matching replicate structure [7] [10].

- Sequencing Depth: For broad histone marks like H3K27me3, each replicate should have 45 million usable fragments, while narrow marks require 20 million fragments per replicate [7]. H3K9me3 represents an exception due to its enrichment in repetitive regions [7].

- Library Complexity: Preferred values are NRF>0.9, PBC1>0.9, and PBC2>10 [7].

Quality control metrics should be collected to determine library complexity, read depth, FRiP score (Fraction of Reads in Peaks), and reproducibility [7].

Analytical Approaches for Histone Modification Data

Different analytical approaches are required depending on the nature of the histone modification being studied. Modifications with sharp, punctate distributions (e.g., H3K4me3) can be analyzed using algorithms designed for peak calling, such as MACS [10]. In contrast, modifications with broad genomic footprints (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K9me3) require specialized tools like SICER, ChromaBlocks, or histoneHMM that can identify large enriched domains [10] [5].

For differential analysis between conditions, several methods have been developed specifically for broad histone marks. The histoneHMM algorithm uses a bivariate Hidden Markov Model to classify genomic regions as modified in both samples, unmodified in both samples, or differentially modified between samples [5]. This approach has been shown to outperform methods designed for peak-like features when analyzing broad histone modifications [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Histone Modification Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Example | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Histone Modification Antibodies | H3K4me3 (CST #9751S), H3K27me3 (CST #9733S), H3K9me3 (CST #9754S) [6] | Immunoprecipitation of specific histone modifications |

| Crosslinking Reagent | Formaldehyde solution (37% w/w) [6] | Crosslinks proteins to DNA in living cells |

| Cell Lysis Buffer | 5 mM PIPES pH 8, 85 mM KCl, 1% igepal [6] | Cell membrane disruption and chromatin release |

| Nuclei Lysis Buffer | 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS [6] | Nuclear membrane disruption |

| Chromatin Shearing Instrument | Bioruptor UCD-200 (Diagenode) or equivalent [6] | Chromatin fragmentation to mononucleosome size |

| Protease Inhibitors | Aprotinin, Leupeptin, PMSF [6] | Prevent protein degradation during processing |

| IP Dilution Buffer | 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% igepal, 0.25% deoxycholic acid, 1 mM EDTA [6] | Dilution of chromatin before immunoprecipitation |

| DNA Purification Kit | QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN) [6] | Purification of ChIP DNA after crosslink reversal |

| SM30 Protein | SM30 Protein|Sea Urchin Spicule Matrix Protein | SM30 Protein is a key matrix protein from sea urchin spicules, vital for biomineralization studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| N-Butyl Nortadalafil | N-Butyl Nortadalafil (CAS 171596-31-9) - Tadalafil Analog | N-Butyl Nortadalafil is a high-purity Tadalafil analog for PDE5 inhibitor research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Advanced Applications and Recent Technological Developments

Single-Cell Histone Modification Analysis

Traditional ChIP-seq requires thousands to millions of cells, masking cellular heterogeneity within samples. Recent advances have enabled single-cell analysis of histone modifications, providing unprecedented resolution for studying epigenetic heterogeneity. The TACIT (Target Chromatin Indexing and Tagmentation) method enables genome-coverage single-cell profiling of multiple histone modifications simultaneously [8].

TACIT has been applied to profile seven histone modifications (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K9me3, and H2A.Z) across mouse early embryo development, revealing cellular heterogeneity and epigenetic reprogramming at single-cell resolution [8]. Further development led to CoTACIT (Combined TACIT), which can profile multiple histone modifications in the same single cell through sequential rounds of antibody binding and tagmentation [8].

These single-cell technologies have revealed that histone modification heterogeneity emerges as early as the two-cell stage in mouse embryos, with H3K27ac profiles showing marked heterogeneity at this stage compared to other modifications [8]. This finding suggests that cells may begin to establish functional heterogeneity immediately after zygotic genome activation.

Integrative Analysis and Chromatin State Annotation

Combining multiple histone modification profiles enables comprehensive annotation of chromatin states across the genome. This approach has been powerfully applied to identify regulatory elements and characterize their dynamics during development and disease [8] [9].

By integrating profiles of six histone modifications with single-cell RNA sequencing data, researchers have developed models that predict the earliest cell lineage branching events during embryonic development and identify novel lineage-specifying transcription factors [8]. Such integrative approaches provide insights into how combinatorial histone modification patterns contribute to cell fate decisions.

Several curated databases provide comprehensive information about histone modifications. The CHHM (Catalogue of Human Histone Modifications) database is a manually curated resource containing 6,612 non-redundant modification entries covering 31 types of modifications and 2 types of histone-DNA crosslinks [2]. This database reveals modification hotspot regions and uneven distribution patterns across histone families, providing insights into the specificity of different modification types [2].

Other valuable resources include the ENCODE Consortium, which provides standardized ChIP-seq data and protocols [7], and specialized tools like PTMViz, which offers an interactive platform for analyzing differential abundance of histone PTMs from mass spectrometry data [4].

Histone modifications represent a crucial layer of epigenetic regulation that controls chromatin structure and function. The development of ChIP-seq technologies has enabled comprehensive mapping of these modifications genome-wide, revealing their complex distributions and functional relationships. As single-cell methods and integrative analytical approaches continue to advance, our understanding of how histone modification patterns contribute to cellular identity, lineage specification, and disease pathogenesis will continue to deepen. The standardized protocols, curated databases, and specialized analytical tools described herein provide researchers with essential resources for exploring the fascinating world of histone modifications and their functional consequences.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is a powerful method for analyzing protein interactions with DNA on a genome-wide scale. This technology combines the specificity of chromatin immunoprecipitation with the comprehensive nature of high-throughput DNA sequencing to precisely map the binding sites of DNA-associated proteins. ChIP-seq has revolutionized epigenetic research by enabling researchers to capture the genomic locations of transcription factors, histone modifications, and chromatin-modifying complexes with unprecedented resolution and sensitivity [11].

The fundamental principle underlying ChIP-seq involves the cross-linking of proteins to DNA in living cells, followed by fragmentation of chromatin and immunoprecipitation of the protein-DNA complexes using specific antibodies. The immunoprecipitated DNA is then purified, sequenced, and mapped to a reference genome to identify enriched regions, known as "peaks," which represent potential protein-binding sites [12] [13]. This approach provides a high-resolution snapshot of the epigenetic landscape and gene regulatory networks operating within a cell, making it indispensable for understanding the molecular mechanisms governing gene expression, cellular differentiation, and disease pathogenesis [11].

Principles of ChIP-seq Technology

Fundamental Workflow

The ChIP-seq procedure consists of a series of meticulously orchestrated steps that transform biological material into quantitative genomic data. The process begins with chemical cross-linking, typically using formaldehyde, to covalently stabilize protein-DNA interactions in intact cells [12] [13]. This cross-linking step preserves transient interactions that might be lost during subsequent processing. The chromatin is then fragmented, usually by sonication or enzymatic digestion, to sizes ranging from 100-300 base pairs, creating smaller fragments that are amenable to immunoprecipitation and sequencing [12].

Following fragmentation, antibody-based immunoprecipitation is performed to enrich for DNA fragments bound by the protein of interest. The specificity and quality of this antibody ultimately determine the success of the entire experiment [12]. After immunoprecipitation, the cross-links are reversed, and the enriched DNA is purified. This DNA then undergoes library preparation, where adapters are ligated for amplification and sequencing [13]. The final library is sequenced using high-throughput platforms, generating millions of short reads that are subsequently aligned to a reference genome for identification of enriched regions [11].

Key Technical Considerations

The quality of a ChIP-seq experiment is governed by multiple technical factors that must be carefully optimized. Antibody specificity stands as the most critical determinant, as antibodies with poor reactivity or cross-reactivity can generate misleading results [12]. The ENCODE consortium has established rigorous validation standards requiring both primary and secondary characterization methods, such as immunoblot analysis and immunofluorescence, to confirm antibody specificity before use in ChIP-seq experiments [12].

Sequencing depth represents another crucial consideration, as it directly impacts the sensitivity and resolution of binding site detection. The optimal depth varies significantly depending on the class of protein being studied, with transcription factors requiring different coverage than histone modifications [14]. The choice between single-end versus paired-end sequencing also influences data quality; while single-end sequencing is often sufficient for transcription factors with punctate binding patterns, paired-end sequencing provides advantages for studying broader chromatin domains by directly measuring fragment size without modeling [14].

Figure 1: ChIP-seq Experimental and Computational Workflow. The process begins with chemical cross-linking of proteins to DNA and progresses through chromatin fragmentation, immunoprecipitation, and library preparation before high-throughput sequencing. Computational analysis includes read alignment, quality control, peak calling, and downstream biological interpretation [12] [13] [11].

Experimental Design Considerations

Replicates and Controls

Sound experimental design forms the foundation of robust ChIP-seq studies, with proper replication and controls being essential for generating biologically meaningful results. Biological replicates—independent samples processed separately through the entire experimental workflow—are crucial for distinguishing consistent biological signals from technical variability. The ENCODE consortium and other expert sources recommend a minimum of two biological replicates, with three being preferable for robust statistical analysis [14] [15]. Technical replicates (repeated sequencing of the same library) are generally not necessary [14].

Appropriate control experiments are equally critical for accurate peak calling and data interpretation. The two primary control types are input chromatin (sonicated genomic DNA without immunoprecipitation) and IgG IP (non-specific immunoglobulin immunoprecipitation) [14]. Input chromatin has become the more widely used control as it appears less biased and provides a better representation of background signal across the genome [14]. Each ChIP replicate should have its own matching input control sequenced separately, as pooling inputs across replicates compromises the ability to assess local background fluctuations [14].

Sequencing Depth Guidelines

Sequencing depth requirements vary substantially depending on the biological target, with different classes of DNA-associated proteins demanding distinct coverage levels. The table below summarizes recommended sequencing depths for various factor types based on established guidelines from the ENCODE consortium and other authoritative sources.

Table 1: Recommended ChIP-seq Sequencing Depth by Target Type [14] [16] [15]

| Protein Class | Examples | Recommended Depth | Read Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point Source Factors | Transcription factors, H3K4me3 | 20-25 million reads | Single-end sufficient |

| Mixed Pattern Factors | H3K36me3 | 35 million reads | Paired-end recommended |

| Broad Signal Factors | H3K27me3, chromatin remodelers | 40-55+ million reads | Paired-end recommended |

For transcription factor studies, the ENCODE consortium specifies that each replicate should contain at least 20 million usable fragments, with 10-20 million considered low depth and fewer than 5 million fragments deemed extremely low depth [16]. It is vital that samples are sequenced to sufficient depth to detect binding events in each replicate independently; if replicates must be pooled to identify peaks, the sequencing was too shallow [14].

Antibody Validation Standards

The success of any ChIP-seq experiment hinges on antibody quality and specificity. The ENCODE consortium has established rigorous validation protocols that require both primary and secondary characterization methods [12]. For antibodies directed against transcription factors, immunoblot analysis serves as the primary characterization method, where the principal reactive band should contain at least 50% of the signal observed on the blot and ideally correspond to the expected size of the target protein [12].

When immunoblot analysis proves unsuccessful, immunofluorescence can serve as an alternative primary characterization method, with staining expected to show appropriate subcellular localization (e.g., nuclear) and expression patterns consistent with the known biology of the target [12]. For histone modifications, the characterization process differs, though the underlying principle of demonstrating specificity remains equally important. These validation standards help ensure that the resulting data truly reflect the binding pattern of the intended target rather than artifacts of antibody cross-reactivity.

ChIP-seq Protocol for Histone Modifications

Sample Preparation and Cross-Linking

The ChIP-seq protocol for histone modifications begins with careful sample preparation. For histone marks, cross-linking conditions may require optimization, though standard formaldehyde cross-linking (1% final concentration for 10-15 minutes at room temperature) is typically sufficient. After cross-linking, the reaction is quenched with glycine, and cells are washed and collected. Cell lysis is performed using an appropriate buffer, and chromatin is fragmented to an average size of 200-500 base pairs [12] [13].

For histone modifications, micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion is often preferred over sonication, as it cleaves chromatin in a more controlled manner at nucleosome-free regions, resulting in primarily mononucleosomal fragments. The extent of digestion should be optimized for each cell type and confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis to ensure the majority of fragments fall within the desired size range [12].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

The immunoprecipitation step requires careful optimization of conditions to maximize specific enrichment while minimizing background. After fragmentation, the chromatin is incubated with the validated antibody specific for the histone modification of interest. Antibody concentration and incubation time should be determined empirically, with typical incubations ranging from 2 hours to overnight at 4°C with rotation [12].

Protein A/G beads are then added to capture the antibody-chromatin complexes, followed by extensive washing with buffers of increasing stringency to remove non-specifically bound chromatin. The cross-links are subsequently reversed by incubation at 65°C for several hours (or overnight) in the presence of NaCl, and the DNA is purified using phenol-chloroform extraction or silica membrane-based kits [13]. The purified DNA should be quantified using sensitive fluorescence-based methods, as yields can be low, particularly for less abundant modifications.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Library preparation for ChIP-seq follows standard protocols for next-generation sequencing, with several considerations specific to histone modification studies. Due to the typically lower DNA yields from ChIP for some histone marks, library amplification may require additional PCR cycles, though care should be taken to minimize amplification biases and duplicates [14].

For broad histone marks like H3K27me3, paired-end sequencing is recommended as it provides more accurate fragment size information and improves mapping confidence across extended genomic domains [14]. The resulting libraries should undergo quality control assessment using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation to confirm appropriate size distribution and absence of adapter dimers before sequencing to the recommended depth for the specific histone mark being studied.

Data Analysis Pipeline

Quality Control and Read Alignment

The computational analysis of ChIP-seq data begins with comprehensive quality assessment of the raw sequencing data. FastQC is commonly employed to evaluate sequence quality, GC content, adapter contamination, and other potential issues [13]. If quality issues are identified, trimming tools may be used to remove low-quality bases or adapter sequences, though this step is optional if data quality is high [11].

Following quality control, reads are aligned to the appropriate reference genome using specialized aligners such as Bowtie2 or BWA [13] [11]. For percentage of uniquely mapped reads, 70% or higher is considered good, whereas 50% or lower is concerning, though these thresholds may vary across organisms [13]. The resulting Sequence Alignment/Map (SAM) files are converted to their binary equivalent (BAM) and sorted by genomic coordinates to facilitate subsequent analysis [13].

Peak Calling and Quality Assessment

Peak calling represents the core analytical step in ChIP-seq data analysis, where enriched regions are identified statistically. For histone modifications with broad domains, such as H3K27me3, specialized peak callers that can detect extended regions of enrichment are preferred over those designed for punctate transcription factor binding sites [12]. MACS2 (Model-based Analysis of ChIP-seq) is widely used for both narrow and broad peaks, with appropriate parameter adjustments for different mark types [13].

The quality of the ChIP-seq experiment should be assessed using established metrics, including the FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks) score, which measures the fraction of all mapped reads that fall within peak regions and serves as an indicator of enrichment efficiency [16]. Library complexity should be evaluated using the Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) and PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients (PBC1 and PBC2), with preferred values of NRF>0.9, PBC1>0.9, and PBC2>10 indicating high-quality libraries [16].

Figure 2: ChIP-seq Data Analysis Pipeline. The computational workflow begins with quality assessment of raw sequencing data, proceeds through alignment and filtering, then to peak calling and annotation, culminating in biological interpretation through visualization and motif analysis [13] [11].

Applications in Epigenetic Research

Mapping Histone Modifications

ChIP-seq has become the gold standard for comprehensively mapping histone modifications across the genome, providing critical insights into the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Different histone modifications are associated with distinct chromatin states and functional elements; for example, H3K4me3 marks active promoters, H3K36me3 is associated with transcriptional elongation, and H3K27me3 denotes facultative heterochromatin maintained by Polycomb group proteins [12]. By generating genome-wide maps of these modifications, researchers can identify regulatory elements, define chromatin states, and understand how epigenetic patterns change during development, differentiation, and disease progression.

The ability to profile histone modifications has been particularly valuable in cancer epigenomics, where aberrant histone methylation and acetylation patterns contribute to oncogene activation and tumor suppressor silencing. ChIP-seq studies have revealed that cancer cells often display widespread redistributions of histone modifications, creating epigenetic signatures that correlate with clinical outcomes and treatment responses [11]. For instance, heterogeneity in chromatin states has been linked to treatment resistance in breast cancer, where resistant cells show distinct histone modification patterns compared to their sensitive counterparts [11].

Integrating Epigenetic Data

Beyond standalone applications, ChIP-seq data for histone modifications gain additional power when integrated with other genomic datasets. Combining histone modification maps with transcriptome data (RNA-seq) allows researchers to directly correlate epigenetic states with gene expression outcomes, revealing how specific modifications regulate transcriptional programs [11]. Similarly, integration with DNA methylation data can uncover interactions between different layers of epigenetic regulation in development and disease.

The ENCODE and modENCODE consortia have demonstrated the value of large-scale integration of ChIP-seq data with other genomic datasets, generating comprehensive maps of regulatory elements and their epigenetic features across multiple cell types and organisms [12]. These integrated approaches have been instrumental in annotating non-coding regulatory elements, elucidating gene regulatory networks, and interpreting disease-associated genetic variants identified through genome-wide association studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ChIP-seq Experiments [12] [13] [15]

| Category | Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | Cross-linking Agent | Formaldehyde (1% final concentration) for stabilizing protein-DNA interactions |

| Chromatin Fragmentation | Sonication equipment or Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) for chromatin shearing | |

| Specific Antibodies | "ChIP-seq grade" antibodies validated per ENCODE guidelines (primary + secondary characterization) | |

| Protein A/G Beads | Magnetic or agarose beads for antibody-immunocomplex capture | |

| Library Prep Kit | Kits compatible with low-input DNA for next-generation sequencing library construction | |

| Computational Tools | Quality Control | FastQC for sequencing data quality assessment |

| Read Alignment | Bowtie2 or BWA for mapping reads to reference genome | |

| Peak Calling | MACS2 for identification of enriched regions (narrow and broad peaks) | |

| Data Visualization | IGV (Integrative Genomics Viewer) for browser-based exploration of results | |

| Motif Analysis | HOMER or MEME Suite for transcription factor binding motif discovery | |

| Dip-Cl | Dip-Cl, CAS:135048-70-3, MF:C24H36Cl4N8, MW:578.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,2'-Dinitrobibenzyl | 2,2'-Dinitrobibenzyl, CAS:16968-19-7, MF:C14H12N2O4, MW:272.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

ChIP-seq technology has fundamentally transformed epigenetic research by providing a robust and comprehensive method for mapping protein-DNA interactions across the genome. When properly designed and executed with appropriate controls, replicates, and sequencing depth, ChIP-seq generates high-quality data that yield important insights into gene regulatory mechanisms. The applications of this powerful technology continue to expand, particularly in understanding the epigenetic basis of human diseases and developing novel therapeutic strategies. As sequencing technologies advance and analytical methods become more sophisticated, ChIP-seq will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone technique for unraveling the complex epigenetic landscape of cells in health and disease.

Within the framework of ChIP-seq data analysis for histone modifications research, accurately categorizing the genomic enrichment patterns of histone marks is a fundamental prerequisite for biological interpretation. Histone post-translational modifications do not distribute uniformly across the genome but rather form distinct spatial patterns that reflect their functional roles in chromatin organization and gene regulation [17]. The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) Consortium has established a systematic guideline for classifying protein-bound regions into three distinct categories: narrow (point source), broad (broad source), and mixed source factors [17]. This classification provides a critical foundation for selecting appropriate bioinformatic tools and analytical parameters, ultimately determining the accuracy and biological relevance of ChIP-seq findings in epigenetic studies and drug development research.

Biological Basis and Functional Significance

The characteristic enrichment patterns of histone modifications directly correspond to their molecular functions and genomic contexts. Narrow marks, such as H3K4me3 and H3K9ac, typically generate sharp, punctate signals concentrated at specific genomic loci like promoters and enhancers [17] [7]. These modifications often denote active regulatory elements with precise genomic positioning. In contrast, broad marks, including H3K27me3 and H3K36me3, form extensive domains that can span entire gene bodies or large chromatin regions [18] [7]. H3K36me3, for instance, is predominantly enriched across the transcribed regions of actively expressed genes, while H3K27me3 characterizes extensive repressive domains associated with facultative heterochromatin [17]. The mixed profile category encompasses histone modifications such as H3K4ac, H3K56ac, and H3K79me1/me2 that exhibit both narrow and broad characteristics, presenting unique challenges for consistent detection and analysis [17].

The following diagram illustrates the characteristic genomic profiles of these three categories of histone modifications:

Quantitative Classification of Histone Modifications

Based on large-scale analyses of ChIP-seq data from human embryonic stem cell lines, histone modifications can be systematically categorized according to their enrichment patterns. The table below summarizes the classification of common histone marks based on their genomic distribution characteristics:

Table 1: Classification of histone modifications by enrichment pattern

| Category | Histone Modifications | Genomic Features | Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow Marks | H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac, H3K4me2 | Sharp, punctate peaks at specific loci | Promoter activation, enhancer marking, transcriptional initiation |

| Broad Marks | H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K9me1, H3K9me2, H3K79me2, H3K79me3, H4K20me1 | Extended domains covering gene bodies or large regions | Transcriptional elongation, polycomb repression, heterochromatin formation |

| Mixed Profiles | H3K4ac, H3K56ac, H3K79me1/me2 | Combination of narrow and broad features | Diverse regulatory roles with variable distribution |

This classification directly informs experimental design, as the ENCODE Consortium has established distinct sequencing depth requirements for different mark types: narrow marks require 20 million usable fragments per replicate, while broad marks require 45 million fragments to adequately capture their extended domains [7]. The exception is H3K9me3, which is enriched in repetitive regions and consequently requires special consideration in read mapping and analysis [7].

Analysis Methods and Peak Calling Strategies

Algorithm Selection for Different Mark Types

The accurate detection of enriched regions in ChIP-seq data requires specialized computational approaches tailored to the distinct characteristics of each histone mark category. For narrow marks, conventional peak callers such as MACS2 effectively identify punctate binding sites by leveraging strand asymmetry and fragment size distribution [19]. These algorithms model the bimodal distribution of reads surrounding transcription factor binding sites or narrow histone marks to precisely localize enrichment summits.

For broad domains, specialized tools or algorithm settings are necessary to capture extended regions of enrichment. MACS2 offers a broad peak calling mode specifically designed for such marks [19]. Alternative programs including hiddenDomains, SICER, and Rseg employ different statistical approaches to identify extended domains without fragmenting them into artificial narrow peaks [18]. The hiddenDomains tool is particularly noteworthy as it utilizes hidden Markov models (HMMs) to simultaneously identify both narrow peaks and broad domains, making it suitable for mixed profiles or when analyzing multiple mark types within a consistent framework [18].

Comparative Performance of Peak Callers

A comprehensive evaluation of five peak calling programs (CisGenome, MACS1, MACS2, PeakSeq, and SISSRs) across 12 histone modifications revealed that performance varies significantly depending on the mark type [17]. While there were no major differences among peak callers when analyzing narrow marks, the results for broad and mixed marks showed considerable variation in sensitivity and specificity [17]. Studies comparing domain calling methods have demonstrated that programs differ substantially in their tendency to fragment broad domains, with some algorithms producing numerous short peaks while others maintain more biologically plausible extended domains [18].

Addressing Artifactual Signals

A critical step in ChIP-seq analysis involves filtering artifactual signals that arise from technical artifacts rather than biological enrichment. The ENCODE project has developed "blacklist" regions for several model organisms—genomic areas with consistently high artifactual signals due to low mappability or repetitive elements [20]. For organisms without established blacklists, the "greenscreen" method provides a versatile alternative that can be generated with as few as two input control samples, effectively removing false positive signals while covering less of the genome than traditional blacklists [20].

The following workflow diagram outlines a comprehensive ChIP-seq analysis pipeline incorporating appropriate tools for different histone mark types:

Experimental Protocols

Standardized ChIP-seq Workflow for Histone Modifications

The ENCODE Consortium has established comprehensive protocols for histone ChIP-seq data analysis, with specific modifications based on mark categorization [7]. The basic workflow begins with quality assessment of raw sequencing data, including evaluation of library complexity metrics such as Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF > 0.9) and PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients (PBC1 > 0.9, PBC2 > 10) [7]. High-quality reads are then mapped to the appropriate reference genome using optimized aligners such as Bowtie, followed by stringent filtering against species-specific artifactual regions using blacklist or greenscreen masks [20].

Peak Calling with MACS2 for Different Mark Types

For narrow histone marks, MACS2 should be run with standard parameters:

For broad histone marks, activate the broad peak calling mode:

The parameter -g represents the effective genome size, which accounts for mappable regions rather than the total genome size [19]. For human (hg38), the effective genome size is approximately 2.7e9. The --broad flag adjusts the algorithm to better capture extended domains characteristic of marks like H3K27me3 and H3K36me3 [19] [7].

hiddenDomains for Mixed Profiles

For histone marks with mixed characteristics or when analyzing multiple mark types consistently, hiddenDomains provides a unified approach:

This HMM-based method generates posterior probabilities for enrichment states, allowing researchers to apply confidence thresholds appropriate to their specific biological questions [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for histone mark analysis

| Category | Item | Specification/Version | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Calling Software | MACS2 | 2.1.0+ | Primary peak caller for narrow and broad marks with specialized modes |

| hiddenDomains | Latest | HMM-based simultaneous detection of narrow and broad domains | |

| SICER | 1.1 | Specialized broad domain caller | |

| Quality Control Tools | FastQC | Latest | Initial read quality assessment |

| Bowtie | 1.1.1+ | Read alignment to reference genome | |

| PhantomPeakQualTools | Latest | Cross-correlation analysis for ChIP-seq quality metrics | |

| Filtering Resources | ENCODE Blacklist | Species-specific | Curated artifactual region masks for model organisms |

| Greenscreen | Custom | Sample-specific artifactual signal identification | |

| Reference Data | Effective Genome Sizes | Species-specific | Mappable genome size parameters for peak callers |

| Histone Mark Classification | ENCODE standards | Guide for experimental design and tool selection | |

| Zinc BiCarbonate | Zinc BiCarbonate, CAS:5970-47-8, MF:C2H2O6Zn, MW:187.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Albaspidin AP | Albaspidin AP, CAS:59092-91-0, MF:C22H26O8, MW:418.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Technologies

Recent methodological advances are expanding the horizons of histone mark profiling. Multiplexed ChIP-seq approaches, such as MINUTE-ChIP, enable quantitative comparison of multiple samples against multiple epitopes in a single workflow, dramatically increasing throughput while reducing technical variability [21]. This is particularly valuable for drug development applications where consistent quantitative assessment of epigenetic changes across conditions is essential.

Single-cell ChIP-seq methodologies are beginning to elucidate the cellular heterogeneity within complex tissues and cancers, revealing how histone modification patterns vary between individual cells [9]. These technologies provide unprecedented resolution for understanding epigenetic diversity in tumor samples or during developmental processes.

Computational advances continue to enhance our ability to extract biological insights from histone modification data. Methods for predicting gene expression levels from epigenomic data, identifying chromatin loops from modification patterns, and imputating missing datasets are increasingly sophisticated, enabling more comprehensive interpretation of the functional consequences of histone mark distributions [9].

The rigorous categorization of histone modifications into narrow, broad, and mixed profiles provides an essential framework for designing, executing, and interpreting ChIP-seq experiments. By selecting analysis tools and parameters appropriate for each category, researchers can maximize the biological insights gained from epigenomic studies. As technologies continue to evolve toward higher throughput and single-cell resolution, consistent classification standards will remain fundamental for comparative analyses and meta-analyses across studies, ultimately accelerating the translation of epigenomic discoveries into therapeutic applications.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has become the standard methodology for mapping in vivo protein-DNA interactions, including transcription factors, histone modifications, and polymerases [22]. The quality of the resulting data, however, is profoundly influenced by upstream experimental design decisions. A robust ChIP-seq experiment for histone modification research rests on three fundamental pillars: rigorous antibody validation, appropriate replication strategies, and well-designed control requirements. Neglecting any of these components can compromise data integrity, leading to irreproducible results and erroneous biological conclusions. This application note provides detailed protocols and guidelines for implementing these critical elements within the context of a comprehensive ChIP-seq data analysis thesis, specifically targeting histone modifications research for a professional scientific audience.

The challenges in ChIP-seq are particularly acute when comparing occupancy levels across different biological conditions, such as various cell types, tissues, or treatment states. Normalization during data analysis is complicated by the potential for global, uniform changes in histone modification occupancy. Common computational normalization methods, such as scaling to total read counts or quantile normalization, may either maintain technical variations or mask genuine biological differences [23]. This underscores the necessity for robust experimental design, including the use of spike-in controls, to provide a reliable foundation for subsequent bioinformatic analysis.

Antibody Validation

The Critical Role of Antibody Specificity

The antibody is the cornerstone of any ChIP-seq experiment, as it specifically enriches the histone modification of interest. Antibody validation is therefore a non-negotiable prerequisite. A poorly validated antibody can lead to high background noise, false-positive peak calls, and a failure to detect genuine binding sites. For histone modifications, the challenge is heightened due to the potential for cross-reactivity with similar histone marks or unmodified histone residues. Key validation parameters include specificity, sensitivity, and lot-to-lot consistency.

Practical Validation Methodologies

Before proceeding with full-scale ChIP-seq, the enrichment and specificity of the antibody should be verified. We recommend the following multi-step approach:

- Verification by Western Blotting: The antibody should produce a single band at the expected molecular weight for the target histone protein in a nuclear extract. This confirms basic specificity.

- Peptide Competition Assay: Pre-incubate the antibody with its target peptide (the modified histone peptide) versus a non-target peptide (e.g., an unmodified or differently modified peptide). A successful ChIP signal should be abolished only by the target peptide, demonstrating immunoprecipitation specificity.

- qPCR Validation Pre-Sequencing: Enrichment should be verified at known positive and negative control genomic regions by quantitative PCR (qPCR) before submitting samples for sequencing [24]. This confirms that the immunoprecipitation worked efficiently in the specific cellular context. Compare the ChIP sample to an input DNA control and calculate the percent input or fold enrichment. A good antibody should show strong enrichment at positive control loci and minimal signal at negative control regions.

- Use of Validated Antibody Databases: Source antibodies from reputable suppliers that provide application-specific validation data (e.g., ChIP-seq grade). Resources like the Histone Antibody Specificity Database can provide independent assessments.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for ChIP-seq Antibody Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ChIP-seq Grade Antibody | Specific immunoprecipitation of the target histone-DNA complex. | Look for antibodies specifically validated for ChIP-seq. Check for lot-specific data. |

| Control Peptides | For competition assays to confirm antibody specificity. | Both target (modified) and non-target (unmodified) histone peptides are required. |

| Positive Control Primers | qPCR primers for genomic regions known to bear the histone mark. | Enables pre-sequencing validation of enrichment (e.g., active promoters for H3K4me3). |

| Negative Control Primers | qPCR primers for genomic regions known to lack the histone mark. | Essential for confirming low background signal (e.g., silent heterochromatin). |

| Cross-linking Reagent (Formaldehyde) | Stabilizes protein-DNA interactions in vivo. | Optimization of cross-linking time is critical to avoid over- or under-fixing. |

Replicates and Sequencing Depth

The Imperative for Biological Replication

Biological replicates—samples derived from independent biological experiments—are essential for distinguishing consistent biological signals from technical noise and random biological variability. Relying on a single replicate makes it impossible to assess the reproducibility of the results. The ENCODE consortium and other best-practice guidelines strongly recommend the use of multiple biological replicates [24] [22]. Recent systematic evaluations of G-quadruplex (G4) ChIP-Seq data have revealed considerable heterogeneity in peak calls across replicates, with only a minority of peaks shared across all replicates in some datasets [25]. This highlights a widespread challenge in ChIP-seq reproducibility that can only be addressed through adequate replication.

Determining the Optimal Number of Replicates and Sequencing Depth

While two biological replicates have been a common minimum, emerging evidence suggests that using at least three replicates significantly improves detection accuracy. A 2025 study demonstrated that four replicates are sufficient to achieve reproducible outcomes, with diminishing returns beyond this number [25]. The required sequencing depth depends on the nature of the histone mark. Broader histone marks (e.g., H3K36me3) require more reads than narrow marks (e.g., H3K4me3).

Table 2: Replicate and Sequencing Depth Guidelines for ChIP-seq

| Factor Type | Minimum Biological Replicates | Recommended Sequencing Depth (Mapped Reads) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point-Source Factors (e.g., Transcription Factors) | 2 [24] | 20 million reads per sample (minimum) [24] [22] | Fewer, highly specific binding sites. |

| Histone Modifications (Narrow Peaks) | 2-3 [24] [25] | 20 million reads per sample [22] | Marks like H3K4me3 have localized distributions. |

| Histone Modifications (Broad Domains) | 3 [25] | Up to 60 million reads per sample [22] | Marks like H3K27me3 cover large genomic regions. |

| CUT&RUN (Alternative Protocol) | 2 | 4 to 8 million read pairs per sample [24] | Lower background and higher sensitivity. |

Figure 1: A workflow for determining the optimal number of replicates and sequencing depth based on the type of histone mark being studied.

Control Requirements

Types of Controls and Their Purpose

A well-designed ChIP-seq experiment incorporates several types of controls to account for technical and biological variability and to enable accurate peak calling during data analysis.

- Input DNA Control: This is a no-antibody control consisting of purified, fragmented chromatin that was not subjected to immunoprecipitation. It is a mandatory control that accounts for sequencing background influenced by chromatin accessibility, DNA sequence-specific biases in sonication, and PCR amplification [22] [11]. It is used by peak-calling algorithms like MACS2 to distinguish true enrichment from open chromatin background.

- Immunoprecipitation Controls:

- Positive Control Antibody: An antibody against a well-characterized histone mark (e.g., H3K4me3 in active promoters) can be used to confirm the entire ChIP procedure was successful.

- Negative Control Antibody: A non-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) from the same host species as the specific antibody is used to assess non-specific binding. This is particularly important for judging background noise.

- Spike-in Controls: For experiments comparing different biological conditions, a spike-in adjustment procedure (SAP) using chromatin from a different organism (e.g., Drosophila chromatin added to human samples) can be invaluable [23]. Added prior to immunoprecipitation, the spike-in chromatin serves as an internal reference to normalize for technical variations in IP efficiency, DNA recovery, and library preparation between samples. This allows for a more accurate quantification of global changes in histone modification levels [23].

Quality Assessment and Data Analysis

Pre- and Post-Sequencing QC

Quality control (QC) is an iterative process that begins before sequencing. Pre-sequencing, the size distribution of the ChIP DNA fragments should be checked on a Bioanalyzer or agarose gel. Ideal fragment lengths should be consistent and between 100-300 bp, resulting in the tightest peaks [24]. After sequencing and read alignment, several key metrics should be evaluated to assess the success of the experiment:

- Strand Cross-Correlation: This analysis calculates the Normalized Strand Coefficient (NSC) and Relative Strand Coefficient (RSC). High-quality, enriched ChIP-seq data shows a strong clustering of reads. NSC > 1.05 and RSC > 0.8 are indicative of a successful experiment [22] [26].

- FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks): The FRiP score measures the fraction of all mapped reads that fall within called peak regions. It is a primary metric for signal-to-noise ratio. For histone marks, a FRiP score above 5% is often considered acceptable, though this can vary with the mark's genomic coverage [26].

- Library Complexity: Tools like the

preseqpackage can predict library complexity and assess whether the experiment has been over-sequenced. A low-complexity library indicates excessive PCR duplication, which can limit the discovery of true binding sites. - Replicate Concordance: The reproducibility between biological replicates should be formally assessed using methods like the Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) for two replicates or tools like MSPC or ChIP-R for three or more replicates [25]. A recent study found MSPC to be an optimal solution for reconciling inconsistent signals in noisy data like G4 ChIP-seq [25].

The ChIP-seq Experimental and Analytical Workflow

The entire ChIP-seq process, from cell culture to data interpretation, involves a series of interconnected steps where quality control is paramount. The following workflow integrates the key design elements discussed in this application note.

Figure 2: An integrated workflow for ChIP-seq experiments, highlighting critical steps for antibody validation, controls, and quality assessment.

Rigorous experimental design is the foundation upon which reliable ChIP-seq data for histone modification research is built. There are no effective computational substitutes for poor upfront experimental choices. By adhering to the guidelines outlined in this application note—employing rigorously validated antibodies, incorporating an adequate number of biological replicates (with evidence now favoring three or more), and utilizing the full suite of necessary controls (Input, IgG, and spike-ins for comparative experiments)—researchers can significantly enhance the validity, reproducibility, and biological insight of their ChIP-seq studies. These practices ensure that the subsequent computational analysis, as part of a broader thesis on ChIP-seq protocols, is grounded in high-quality data, leading to more robust and meaningful conclusions in epigenetics and drug development research.

In chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) experiments, sequencing depth—the number of mapped reads per sample—stands as a fundamental determinant of data quality and biological validity. This parameter is particularly crucial for histone modification studies, where the required depth varies dramatically between marks with narrow genomic footprints (e.g., H3K4me3) and those with broad domains (e.g., H3K27me3). Insufficient depth leads to failure in detecting genuine enrichment regions, poor replicate concordance, and ultimately, biologically misleading conclusions. Conversely, over-sequencing incurs unnecessary costs without meaningful information gain. This application note establishes clear, evidence-based guidelines for determining appropriate sequencing depth within the context of a standardized ChIP-seq data analysis protocol for histone modifications research, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a framework for generating robust, reproducible epigenomic data.

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making workflow for planning a histone ChIP-seq experiment, integrating key considerations for mark classification, depth requirements, and appropriate controls.

Established Sequencing Depth Standards

Consortium-led efforts have systematically evaluated the impact of sequencing depth on histone mark detection, establishing clear standards for the field. The ENCODE Project, a leading authority in epigenomics data generation and analysis, provides definitive guidelines that distinguish between narrow and broad histone marks [7] [27]. These standards are designed to ensure the identification of a comprehensive and reproducible set of enriched regions.

ENCODE Standards for Histone Modifications

The table below summarizes the current ENCODE4 sequencing depth standards for histone ChIP-seq experiments, which are considered the gold standard for the field [27].

Table 1: ENCODE4 Sequencing Depth Standards for Histone ChIP-seq

| Histone Mark Category | Minimum Usable Fragments per Replicate | Recommended Usable Fragments per Replicate | Example Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow Marks | 20 million | >20 million | H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K9ac [7] [27] |

| Broad Marks | 20 million | 45 million | H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K4me1 [7] [27] |

| Exception (H3K9me3) | 45 million | 45 million | H3K9me3 (due to enrichment in repetitive regions) [7] [27] |

These requirements are defined in terms of usable fragments, which are non-duplicate, mapped reads that pass quality filters. The rigorous standards for broad marks reflect the challenge of defining the often diffuse boundaries of large enriched domains, which requires a higher density of sequencing reads for accurate resolution [28]. The exceptional case of H3K9me3, a broad mark enriched in repetitive genomic regions, necessitates high depth (45 million reads) because a significant portion of ChIP-seq reads map to non-unique positions, effectively reducing the complexity of the available data [7].

Empirical Evidence Supporting Depth Standards

Independent research corroborates the ENCODE guidelines. An extensive evaluation of sequencing depth impact found that while saturation points can be organism- and mark-dependent, a practical minimum of 40–50 million reads is advisable for most broad histone marks in human cells [28]. This aligns with the ENCODE recommended standard of 45 million reads. The study defined "sufficient sequencing depth" as the point where detected enriched regions increase by less than 1% for each additional million reads sequenced, providing a data-driven metric for saturation [28].

Experimental Protocol for Reliable Histone ChIP-seq

Adhering to a standardized protocol is essential for generating high-quality ChIP-seq data that meets the aforementioned depth guidelines. The following section outlines a robust workflow, with special emphasis on steps critical for quantitative comparisons.

Standard Histone ChIP-seq Workflow

The core steps of a ChIP-seq experiment are outlined below. While specific protocols may vary by laboratory, the key principles of chromatin fragmentation, specific immunoprecipitation, and library preparation remain consistent.

Advanced Protocol: Spike-in Controlled ChIP-seq

For experiments involving global changes in histone modification levels (e.g., after drug treatment inhibiting histone deacetylases), standard normalization methods fail. In these cases, a spike-in control is essential to accurately capture quantitative changes [29]. The following protocol uses Drosophila chromatin spiked into human samples.

Table 2: Protocol for Spike-in Controlled H3K27ac ChIP-seq [29]

| Step | Procedure | Critical Parameters | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Global Change Assessment | Treat cells (e.g., with HDAC inhibitor SAHA vs. DMSO control). Acid-extract histones and perform Western blot with target antibody (e.g., H3K27-ac). | Confirm robust global increase in modification (>2-fold). | To determine the necessity for spike-in ChIP-seq. |

| 2. Chromatin Preparation | Grow human cells (e.g., PC-3) and Drosophila S2 cells (spike-in). Cross-link with formaldehyde, harvest, and sonicate chromatin. | Sonicate to 100-600 bp fragment size. Measure DNA concentration. | To generate sheared chromatin from both species. |

| 3. Antibody Verification | Perform immunoprecipitation with ChIP-grade antibody on both human and S2 chromatin lysates. Verify by Western blot. | Confirm antibody specifically recognizes the modification in both species. | To ensure antibody efficiency and specificity for spike-in normalization. |

| 4. Spike-in IP | Combine a fixed amount of Drosophila S2 chromatin with each human chromatin sample. Perform a single IP with the target antibody. | Maintain a consistent spike-in to sample chromatin ratio across all samples. | To provide an internal control for normalization during bioinformatic analysis. |

| 5. Library Prep & Sequencing | Prepare sequencing libraries from IP and input DNA. Use barcoding for multiplexing. Sequence to recommended depth. | Follow standard library prep protocols. Use tools like "SPIKER" for analysis. | To generate data scalable for quantitative cross-comparison. |

Successful execution of a ChIP-seq experiment relies on high-quality reagents and specialized software. The following table catalogues key resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Histone ChIP-seq

| Category / Item | Specification / Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Highly characterized, ChIP-seq grade antibodies specific to histone modifications. | Must be validated according to ENCODE standards (e.g., by dot blot, Western). Specificity is paramount [7]. |

| Spike-in Chromatin | Chromatin from an evolutionarily distant species (e.g., Drosophila S2 for human samples). | Provides an internal control for normalization in quantitative experiments [29]. |

| Crosslinking Reagent | Formaldehyde (typically 1-11% solution). | Reversibly cross-links proteins to DNA in living cells. Quenching with glycine is critical [29]. |

| Sonication System | Ultrasonic homogenizer with microtip (e.g., Misonix 3000). | Shears chromatin to 100-600 bp fragments. Conditions require optimization for cell type and crosslinking [29]. |

| Peak Caller (Broad) | SICER, Rseg, hiddenDomains | Algorithms designed to identify diffuse, broad domains of enrichment [18] [5]. |

| Peak Caller (Narrow) | MACS2 (in narrow mode), HOMER | Algorithms optimized for punctate, sharp peaks of enrichment [18]. |

| Differential Analysis | histoneHMM (R package) | A bivariate Hidden Markov Model for differential analysis of histone modifications with broad footprints [5]. |

| Quality Control | CHANCE, Phantompeakqualtools | Tools to assess IP strength and strand cross-correlation (NSC, RSC scores) [22]. |

Adherence to established sequencing depth guidelines is not an arbitrary benchmark but a foundational requirement for scientific rigor in histone ChIP-seq studies. The clear distinction between the requirements for narrow (≥20 million fragments) and broad (≥45 million fragments) marks, as defined by the ENCODE consortium and supported by independent research, should form the basis of experimental design [7] [28] [27]. Furthermore, researchers must be prepared to implement advanced quantitative techniques, such as spike-in controlled ChIP-seq, when studying conditions that induce global changes in histone modification levels [29] [30]. By integrating these standards with robust experimental protocols and appropriate computational tools—such as hiddenDomains or histoneHMM for broad mark analysis [18] [5]—researchers can ensure their data is of high quality, reproducible, and capable of yielding biologically meaningful insights into the epigenetic regulation of gene expression in development and disease.

A Step-by-Step ChIP-seq Analysis Workflow for Histone Marks

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has become an indispensable method for mapping genome-wide protein-DNA interactions, particularly for studying histone modifications in epigenetic research. For histone marks, which often exhibit broad genomic domains, the initial data processing steps—from raw sequencing reads to aligned files—are critical for generating reliable binding patterns. This protocol outlines a standardized workflow for processing ChIP-seq data specifically tailored to histone modification studies, ensuring researchers can generate high-quality aligned BAM files suitable for downstream peak calling and chromatin state annotation. The accuracy of this initial processing phase directly influences all subsequent analyses, including enhancer identification, chromatin state mapping, and interpretation of gene regulatory mechanisms relevant to drug discovery and development.

The processing of ChIP-seq data for histone modifications presents unique challenges compared to transcription factor studies. Histone marks such as H3K27me3 or H3K36me3 often cover broad genomic regions requiring greater sequencing depth—typically 40-60 million reads compared to 20-30 million for transcription factors [31]. Furthermore, specialized normalization approaches like spike-in controls become essential when investigating global chromatin changes, such as those induced by histone deacetylase inhibitors [29]. This protocol addresses these specific requirements while maintaining compatibility with established consortium standards like those from ENCODE, which provide rigorous guidelines for experimental replication, sequencing depth, and quality assessment [7] [12].

Experimental Design and Sequencing Considerations

Sequencing Requirements for Histone Modifications

Appropriate experimental design is paramount for successful ChIP-seq studies of histone modifications. The ENCODE consortium has established target-specific standards distinguishing between broad and narrow histone marks, with different sequencing depth requirements for each category [7]. The table below summarizes these key design considerations:

Table 1: Sequencing Requirements for Histone Modification ChIP-seq

| Factor | Recommended Depth | Mark Type | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad histone marks | 45 million fragments per replicate | Broad domains | H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K9me3 |

| Narrow histone marks | 20 million fragments per replicate | Punctate patterns | H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K9ac |

| H3K9me3 exception | 45 million total mapped reads | Repetitive regions | H3K9me3 (in tissues/primary cells) |

Beyond sequencing depth, library complexity measurements provide crucial quality indicators. The ENCODE consortium recommends Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) > 0.9, PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient 1 (PBC1) > 0.9, and PBC2 > 3 as indicators of high-quality libraries [7]. For studies investigating massive changes in histone acetylation, such as those induced by HDAC inhibitors like SAHA, spike-in controls using chromatin from an ancestral species (e.g., Drosophila S2 cells for human studies) become essential for proper normalization [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ChIP-seq Data Processing

| Category | Item | Function | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment Tools | Bowtie2 | Maps sequencing reads to reference genome | Optimal for reads ≥50bp; supports local alignment [32] |

| BWA | Alternative aligner for shorter reads | Better for reads <50bp; higher mapping rates but potentially more duplicates [32] | |

| Processing Tools | SAMtools | Manipulates SAM/BAM files | Format conversion, sorting, indexing [32] |

| Picard | Processes BAM files | Duplicate marking, QC metrics [31] | |

| Quality Control | FastQC | Initial read quality assessment | Per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination [33] |

| ChIPseeker | Peak annotation and visualization | Genomic feature assignment, functional analysis [34] | |

| Reference Data | Genome indices | Enables efficient read alignment | Pre-built for common genomes (e.g., hg38, mm10) [32] |

| Annotation databases | Genomic context interpretation | TxDb, EnsDb for specific organisms [34] | |

| Senegin II | Senegin II, CAS:34366-31-9, MF:C70H104O32, MW:1457.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 1,2-Diethoxypropane | 1,2-Diethoxypropane, CAS:10221-57-5, MF:C7H16O2, MW:132.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Computational Workflow: From FASTQ to BAM

The journey from raw sequencing data to aligned BAM files involves multiple critical steps that transform short DNA sequences into genomic coordinates. The workflow can be conceptualized as a sequential process with quality checkpoints at each stage to ensure data integrity. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow with key decision points:

Initial Quality Assessment and Preprocessing

The analysis begins with quality assessment of raw FASTQ files using tools like FastQC. This critical first step evaluates per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, GC content, and sequence duplication levels. For histone ChIP-seq data, particular attention should be paid to library complexity metrics, as histone modifications often exhibit diffuse binding patterns requiring high-quality libraries [7] [35].

If quality issues are identified, preprocessing steps such as adapter trimming may be necessary. While some aligners like Bowtie2 offer local alignment modes that can soft-clip poor quality bases or adapters from untrimmed reads, explicit trimming is often recommended for consistent results [32]. For histone modification studies, preserving read length is particularly important as longer reads (≥50bp) improve mappability and genomic coverage, especially in repetitive regions commonly associated with heterochromatic marks like H3K9me3 [7].

Read Alignment and Processing

Alignment to Reference Genome

The core of the processing workflow involves aligning sequencing reads to an appropriate reference genome. Bowtie2 has emerged as a widely adopted aligner for ChIP-seq data due to its speed, accuracy, and ability to handle various read lengths through its local alignment mode [32]. The basic alignment command follows this structure:

Key parameters include:

-p: Number of processor cores for parallel alignment-q: Indicates input is in FASTQ format--local: Enables soft-clipping of adapters/poor quality bases-x: Path to pre-built genome indices-U: Input FASTQ file (single-end)-S: Output SAM file

For histone modification studies, the selection of an appropriate reference genome is critical. The ENCODE consortium recommends mapping to either GRCh38 (human) or mm10 (mouse) assemblies, with consistency between replicates in terms of read length and run type [7]. Pre-built genome indices are available through shared databases, such as those found in the /n/groups/shared_databases/igenome/ directory on high-performance computing clusters [32].

Post-Alignment Processing

Following alignment, several processing steps transform SAM files into filtered BAM files suitable for downstream analysis:

SAM to BAM Conversion: SAM files are converted to compressed BAM format using SAMtools:

Coordinate Sorting: BAM files are sorted by genomic coordinate to enable efficient downstream processing:

Read Filtering: For histone modifications, filtering to retain only uniquely mapping reads increases confidence in binding site identification. While Bowtie2 doesn't directly output only unique mappers, this filtering can be achieved through SAMtools by excluding reads with mapping quality below a threshold (e.g., MAPQ < 10) [32]. The optimal threshold may vary depending on the specific histone mark and genome complexity.

Table 3: Key Alignment Metrics for Quality Assessment

| Metric | Target Value | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Mapping Rate | >70-80% | Indifies efficient alignment to reference |

| Uniquely Mapped Reads | Maximize | Reduces false positives in peak calling |

| Library Complexity (NRF) | >0.9 | Measures PCR duplication levels |

| PCR Bottlenecking (PBC) | PBC1>0.9, PBC2>3 | Indicates library diversity and quality |

| Fragment Size Distribution | Matches expected | Confirms appropriate sonication |

Quality Control and Troubleshooting

Assessing Alignment Quality

Comprehensive quality assessment after alignment is essential for validating data prior to peak calling. Key metrics include mapping statistics, library complexity, and cross-correlation analysis. The Fraction of Reads in Peaks (FRiP) score, while typically calculated during peak calling, provides a crucial quality indicator specific to histone modifications—broad marks generally exhibit lower FRiP scores than punctate marks due to their diffuse nature [7] [35].

For studies investigating global changes in histone acetylation, such as those induced by HDAC inhibitors, specialized normalization approaches like spike-in controls become essential. As demonstrated in spike-in ChIP-seq protocols, adding a constant amount of chromatin from an ancestral species (e.g., Drosophila S2 cells for human studies) enables proper normalization when treatment dramatically alters global acetylation levels [29]. The SPIKER tool provides specialized analysis methods for such spike-in controlled experiments.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Several common issues may arise during ChIP-seq data processing for histone modifications:

- Low mapping rates: Can result from poor read quality, incorrect reference genome, or excessive fragmentation. Verify reference genome compatibility and check FASTQ quality metrics.

- High duplicate rates: May indicate insufficient sequencing depth or PCR overamplification. Consider deeper sequencing or optimizing library preparation.

- Strand cross-correlation peaks: Poor cross-correlation can indicate low antibody specificity or suboptimal fragmentation [35].

- Unusual fragment size distribution: May suggest sonication issues or incomplete size selection.

When encountering these issues, consult the ENCODE guidelines for target-specific recommendations, particularly for challenging marks like H3K9me3 that are enriched in repetitive regions and may require specialized analytical approaches [7].

The processing of raw ChIP-seq data from FASTQ to aligned BAM files represents a critical foundation for all subsequent analyses in histone modification research. By following this standardized protocol—incorporating appropriate quality controls, alignment strategies, and filtering approaches—researchers can generate reliable, high-quality datasets suitable for identifying broad chromatin domains associated with histone marks. The resulting BAM files serve as input for specialized peak callers like MACS2 (with broad peak settings) and downstream analyses including chromatin state annotation, enhancer identification, and correlation with gene expression data.

This protocol emphasizes considerations specific to histone modifications, such as increased sequencing depth requirements for broad marks and spike-in normalization for global acetylation changes. Adherence to these standards ensures generated data meets consortium quality metrics and enables robust biological interpretation relevant to understanding epigenetic mechanisms in development, disease, and drug response.

Within the framework of a comprehensive ChIP-seq data analysis protocol for histone modification research, rigorous quality control (QC) is the cornerstone of generating biologically valid results. Histone modifications, such as H3K27ac or H3K27me3, are fundamental to understanding the epigenomic landscape and its role in cell identity, development, and disease [9] [36]. Unlike transcription factors that bind DNA in a punctate manner, histones often associate with DNA over broader regions, necessitating specific analytical approaches and quality assessments [12] [7]. This application note details three critical QC metrics—Strand Cross-Correlation, FRiP, and Library Complexity—that researchers must evaluate to ensure data integrity before proceeding to advanced biological interpretation.

Key Quality Control Metrics

Strand Cross-Correlation Analysis

Strand Cross-Correlation is a powerful metric used to assess the signal-to-noise ratio of a ChIP-seq experiment and to estimate the average fragment length of the immunoprecipitated DNA. The analysis is based on the premise that genuine ChIP-seq signals from specific protein-DNA interactions will produce clusters of reads on both forward and reverse strands, shifted from each other by the fragment length.

Protocol for Calculation:

- Read Mapping: Map sequenced reads to the reference genome using an aligner such as BWA, Bowtie, or Bowtie2 [37] [13].

- Strand Separation: Separate the aligned reads into forward-strand and reverse-strand BAM files.

- Genome Binning: Divide the genome into consecutive bins (e.g., 1-basepair or 10-basepair resolution).

- Cross-Correlation: Calculate the correlation coefficient between the forward-strand and reverse-strand read coverage profiles at a series of sequential shift values (lags). This creates a cross-correlation profile.

- Peak Identification: Identify two key peaks in the profile:

- A phantom peak at the read length, caused by background noise.

- A cross-correlation peak at the fragment length, indicative of true enrichment.

The quality of the experiment is often summarized by the Normalized Strand Coefficient (NSC) and the Relative Strand Coefficient (RSC). The following table outlines the interpretation of these values, as utilized by pipelines like ChiLin and ENCODE phantompeakqualtools [37].

Table 1: Interpretation of Strand Cross-Correlation Metrics

| Metric | Calculation | High-Quality Data | Marginal Data | Low-Quality Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normalized Strand Coefficient (NSC) | Ratio of the fragment-length cross-correlation to the background cross-correlation. | > 1.05 | 1.0 - 1.05 | < 1.0 |