A Comprehensive Guide to Histone Mark Enrichment Analysis from ChIP-seq Data: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on histone mark enrichment analysis using ChIP-seq technology.

A Comprehensive Guide to Histone Mark Enrichment Analysis from ChIP-seq Data: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on histone mark enrichment analysis using ChIP-seq technology. It covers foundational principles of histone modifications and their biological significance, established and cutting-edge methodological workflows including automated pipelines and quantitative techniques, troubleshooting and optimization strategies to address common challenges, and rigorous validation and comparative analysis frameworks. By integrating current standards from consortia like ENCODE with recent methodological advances such as Micro-C-ChIP and siQ-ChIP, this resource equips scientists with the knowledge to design robust epigenomic studies, accurately interpret histone modification data, and translate findings into biomedical insights.

Understanding Histone Modifications and ChIP-seq Fundamentals

Within the nucleus of every eukaryotic cell, DNA is packaged into chromatin, a complex structure whose fundamental unit is the nucleosome. Each nucleosome consists of ~147 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of core histone proteins (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4). The N-terminal tails of these histones protrude from the nucleosome core and are subject to post-translational modifications (PTMs) that constitute a critical layer of epigenetic regulation [1]. These histone modifications function as a sophisticated "code" that is interpreted by cellular machinery to control DNA accessibility, thereby influencing fundamental processes including gene transcription, DNA replication, and repair [1]. This whitepaper focuses on the core biological roles of key histone marks, framing their functions within the context of histone mark enrichment analysis from ChIP-seq data, a cornerstone technique in modern epigenomic research.

The hypothesis that distinct histone modifications direct unique downstream transcriptional effects is central to epigenetics [2]. However, modifications are often broadly categorized as simply "activating" or "repressing," raising questions about their potential functional redundancy. Recent research, employing sophisticated genomic engineering approaches, has demonstrated that while some functional overlap exists, individual modifications exert unique effects that are highly dependent on the existing chromatin context [2]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the major activating and repressive histone marks, their functional interplay, and the advanced methodologies used to decipher their roles, with particular relevance for researchers and drug development professionals.

Activating Histone Marks and Their Functions

Activating histone marks create a permissive chromatin environment that facilitates transcription. They are typically characterized by a more open, accessible chromatin structure known as euchromatin, which allows transcriptional machinery to bind DNA [1]. The most significant activating marks include acetylation and specific types of methylation.

Histone Acetylation

Histone acetylation is one of the most extensively studied activating modifications. It occurs on lysine residues and is catalyzed by histone acetyltransferases (HATs), while histone deacetylases (HDACs) remove these groups [1]. The primary mechanism of action is charge neutralization: unmodified lysine residues are positively charged, interacting strongly with the negatively charged DNA phosphate backbone. Acetylation neutralizes this positive charge, weakening histone-DNA interactions and causing nucleosomes to unwind. This open conformation allows transcription factors and other regulatory proteins to access the DNA, significantly increasing gene expression [1]. Key acetylation marks include:

- H3K9ac and H3K27ac: These are typically associated with enhancers and promoters of active genes [1]. H3K27ac, in particular, is a hallmark of active enhancers, distinguishing them from their "poised" or inactive counterparts.

Activating Methylation Marks

Contrary to acetylation, histone methylation does not alter the charge of the residue. Its impact on transcription depends critically on the specific lysine or arginine residue that is modified and the degree of methylation (mono-, di-, or tri-methylation) [1]. Key activating methylation marks include:

- H3K4me3: This mark is strongly enriched at active gene promoters and is a key signal for transcriptional initiation [1]. It helps recruit components of the basal transcription machinery.

- H3K36me3: This mark is predominantly found across the gene bodies of actively transcribed genes [2] [1]. It is associated with transcriptional elongation and plays a role in preventing spurious transcription initiation within gene bodies [2].

- H3K79me2: Also associated with active transcription, this mark is found within gene bodies [1].

Table 1: Core Activating Histone Modifications and Their Functions

| Histone Modification | Genomic Location | Primary Function | Associated Enzymes (Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Promoters | Transcriptional activation, initiation | SET1 family methyltransferases |

| H3K36me3 | Gene bodies | Transcriptional elongation, prevents spurious initiation | SETD2 methyltransferase [2] |

| H3K9ac | Enhancers, Promoters | Chromatin relaxation, activation | HATs (e.g., p300/CBP); HDACs |

| H3K27ac | Enhancers, Promoters | Active enhancer marking, activation | HATs (e.g., p300/CBP); HDACs |

| H3K79me2 | Gene bodies | Transcriptional activation | DOT1L methyltransferase |

The following diagram illustrates the canonical genomic distribution of key activating marks during transcriptional activation:

Repressive Histone Marks and Their Functions

Repressive histone marks promote a compact, inaccessible chromatin structure known as heterochromatin, which sterically hinders the binding of transcription factors and RNA polymerase, leading to gene silencing [1]. Two of the most well-characterized repressive marks are H3K27me3 and H3K9me3, which facilitate distinct types of repression.

H3K27me3: A Dynamic Repressive Mark in Development

The H3K27me3 mark is catalyzed by Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), whose core components include EZH2 (the catalytic subunit), EED, SUZ12, and RbAp46/48 [3]. This mark is characterized by:

- Genomic Location: It is found predominantly in gene-rich regions, specifically at the promoters of developmentally critical genes, such as Hox, Pax, and Sox gene families in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [3] [1]. These are often genes that are silent in ESCs but poised for activation upon differentiation.

- Functional Role: H3K27me3 is considered a temporary or "facultative" repression signal [3]. It maintains genes in a transcriptionally silent but reversible state, allowing for precise activation during cellular differentiation and development. Many genes marked by H3K27me3 in ESCs also bear H3K4me3, creating a "bivalent" promoter state that is poised for activation or stable repression upon lineage commitment [1].

- Interaction with DNA Methylation: Genomic regions marked by H3K27me3 are typically protected from DNA methylation, consistent with its role as a reversible silencing mechanism [3].

H3K9me3: A Marker of Stable Heterochromatin

The H3K9me3 mark is established by a different set of enzymes, including SUV39H1, SUV39H2, SETDB1, EHMT1 (GLP), and EHMT2 (G9a) [3]. Its characteristics are distinct from H3K27me3:

- Genomic Location: H3K9me3 is preferentially detected in gene-poor regions, including constitutive heterochromatin such as satellite repeats, telomeres, and pericentromeres [3] [1]. It is also associated with certain retrotransposons and Kruppel-type zinc finger genes [3].

- Functional Role: H3K9me3 is considered a more permanent repression signal that drives the formation of stable, condensed heterochromatin [3]. It is crucial for maintaining genomic integrity by silencing repetitive elements.

- Interaction with DNA Methylation: In contrast to H3K27me3, regions marked by H3K9me3 are often subsequently methylated in somatic cells, reinforcing a stable, long-term silenced state [3].

Recent functional studies highlight the non-redundant nature of these repressive marks. Research in mouse embryonic stem cells has shown that while H3K9me3 can partially substitute for H3K27me3 in repressing target genes, H3K36me3 cannot, despite being accurately recruited. This failure is contingent on the interplay with the existing chromatin environment, particularly the status of H3K4me3, which prevents H3K36me3 from recruiting sufficient DNA methylation to enact repression [2].

Table 2: Core Repressive Histone Modifications and Their Functions

| Histone Modification | Genomic Location | Primary Function | Associated Enzymes (Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K27me3 | Promoters of developmental genes in gene-rich regions | Temporary repression of developmental genes; maintains pluripotency | PRC2 (EZH2, SUZ12, EED) [3] |

| H3K9me3 | Pericentromeres, telomeres, retrotransposons | Permanent heterochromatin formation, genomic stability | SUV39H1/2, SETDB1, G9a (EHMT2) [3] |

| H2AK119ub | Polycomb target genes | Transcriptional repression, PRC2 recruitment | PRC1 complex [1] |

The diagram below summarizes the distinct genomic contexts and functional consequences of the two major repressive histone marks:

Advanced Methodologies for Histone Mark Analysis

Understanding the biological roles of histone marks relies heavily on advanced technologies for mapping and interpreting the epigenome. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has been the gold standard for over a decade.

Standard ChIP-seq Workflow and Analysis

A typical ChIP-seq workflow involves: crosslinking proteins to DNA; fragmenting chromatin (usually by sonication); immunoprecipitating the protein-DNA complexes with antibodies specific to a histone modification; reversing the crosslinks; and sequencing the associated DNA [4] [1]. The resulting data undergoes a standard analysis pipeline:

- Quality Assessment: Checking sequencing quality and library complexity.

- Read Alignment: Mapping sequences to a reference genome.

- Peak Calling: Identifying genomic regions with significant enrichment of the histone mark compared to a background control.

- Downstream Analysis: This includes annotating peaks to genomic features (e.g., promoters, enhancers), comparing patterns between samples, and annotating chromatin states by integrating multiple marks [4].

Cutting-Edge Techniques

Recent technological innovations are pushing the boundaries of epigenetic analysis:

- CUT&Tag: This method replaces sonication with antibody-directed tethering of Tn5 transposase to specific modifications in permeabilized cells. The transposase simultaneously fragments and tags the target chromatin for sequencing. CUT&Tag offers a dramatically improved signal-to-noise ratio and can be performed on low cell inputs, even at the single-cell level [5].

- Single-Cell Multi-Omics (scEpi2-seq): This groundbreaking technique allows for the simultaneous measurement of histone modifications and DNA methylation in the same single cell [6]. It leverages TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS) for bisulfite-free methylation detection, providing unprecedented insight into how these two epigenetic layers interact to define cell states.

- Micro-C-ChIP: This method combines Micro-C (a high-resolution chromosome conformation capture method using MNase digestion) with chromatin immunoprecipitation. It maps 3D genome organization specifically for defined histone modifications at nucleosome resolution, revealing how marks like H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 influence chromatin folding [7].

- Advanced Mass Spectrometry (HiP-Frag): Novel MS workflows like HiP-Frag use unrestrictive search strategies to move beyond canonical modifications, enabling the discovery of previously unannotated histone PTMs, thus expanding the known histone code [8].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Histone Mark Analysis

| Reagent / Resource | Function/Description | Key Examples / Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Modification-Specific Antibodies | Core reagent for immunoprecipitation (ChIP-seq) or tethering (CUT&Tag); specificity is paramount. | Antibodies for H3K4me3, H3K27me3, H3K9me3, H3K27ac, etc. [4] [1] |

| pA-Tn5 Transposase | Engineered protein for tagmentation in CUT&Tag protocols. | Fused to Protein A for antibody-guided recruitment to specific histone marks [5]. |

| pA-MNase Fusion Protein | Enzyme for antibody-directed chromatin digestion in techniques like scEpi2-seq and sortChIC. | Used for targeted MNase digestion in single-cell multi-omics [6]. |

| TET Enzymes & Pyridine Borane | Key reagents for TAPS, a bisulfite-free method for DNA methylation detection. | Enables joint profiling with histone modifications in scEpi2-seq [6]. |

| Validated Cell Lines | Models for studying histone mark dynamics (e.g., during development or disease). | Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (mESCs), K562, RPE-1 hTERT, HCT-116 [2] [6] [7]. |

| Reference Epigenome Datasets | Publicly available data for benchmarking and comparison (e.g., ENCODE, Roadmap). | ENCODE ChIP-seq data for validating specificity of new experiments [6]. |

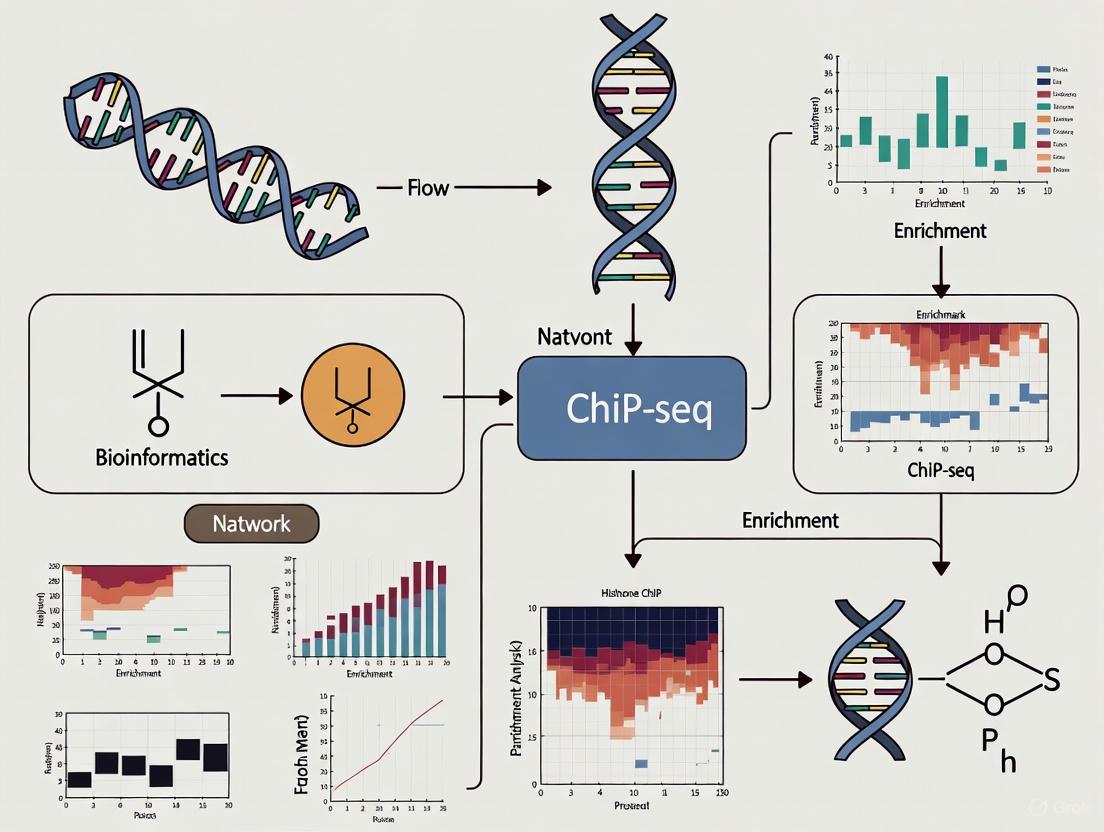

The integrated workflow for a modern, multi-omics approach to histone mark analysis is depicted below:

Applications in Disease and Therapeutic Development

The dynamic and reversible nature of histone modifications makes them attractive therapeutic targets. Aberrations in the enzymatic "writers" and "erasers" of the histone code are implicated in numerous diseases, particularly cancer.

- Cancer: Overexpression of EZH2 (the H3K27me3 methyltransferase in PRC2) is documented in many cancers, leading to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes. Consequently, EZH2 inhibitors have been developed and are in clinical trials [9]. Similarly, inhibitors targeting histone demethylases, such as KDM4, are being investigated for their anti-proliferative effects in cancer models [2].

- Degenerative Skeletal Diseases: In osteoporosis, histone modifications regulate osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation, disrupting bone homeostasis. In osteoarthritis, they drive the expression of matrix-degrading enzymes in chondrocytes. Targeting histone-modifying enzymes is thus being explored as a promising strategy for precision intervention [9].

- Systemic Sclerosis (SSc): Research over the past decade has revealed critical contributions from epigenetic perturbations in SSc pathogenesis. Studies show disease-associated changes in chromatin accessibility in dendritic cells and fibroblasts, suggesting potential for epigenetic therapy [10].

- Forensic Science: The relative stability of histone methylation marks like H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 in degraded samples presents novel applications in forensic epigenetics for analyzing challenging samples, discriminating monozygotic twins, and estimating postmortem intervals [5].

The core biological roles of key histone marks extend far beyond simple activation and repression. They form a complex, interdependent language that dictates cellular identity and function. Marks like H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3 each occupy specific genomic territories and execute unique functions, from maintaining pluripotency to ensuring genomic stability. The interpretation of any single mark is highly context-dependent, influenced by the local combination of other modifications and the broader chromatin environment.

Advances in technology, particularly the shift from bulk ChIP-seq to single-cell multi-omics and high-resolution spatial methods, are rapidly deepening our understanding of this epigenetic language. These tools are revealing the dynamic interplay between histone modifications and other epigenetic layers, such as DNA methylation, in health and disease. For researchers and drug developers, this expanding knowledge base provides a rich source of novel therapeutic targets. The ongoing development of small-molecule inhibitors against histone-modifying enzymes underscores the immense translational potential of deciphering the histone code, paving the way for a new generation of epigenetic medicines.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) stands as a cornerstone methodology in contemporary genomics and epigenetics research, providing unprecedented capability for mapping protein-DNA interactions across the entire genome. This technique integrates the specificity of chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with the robust throughput of next-generation sequencing (NGS), enabling precise localization of DNA binding sites for transcription factors, histone modifications, and other DNA-associated proteins [11]. The fundamental principle underlying ChIP-seq involves capturing protein-DNA interactions within their native chromatin context through in vivo cross-linking, followed by immunoprecipitation using antibodies specific to the protein or histone modification of interest, and ultimately sequencing the bound DNA fragments to generate genome-wide binding maps [11] [12].

The transformative impact of ChIP-seq extends across diverse realms of biological inquiry, particularly in histone mark enrichment analysis. In epigenetics, it has been instrumental in charting genome-wide distributions of histone modifications, offering crucial insights into their regulatory roles in gene expression [11]. In cancer biology, ChIP-seq has pinpointed aberrant binding sites of oncogenic transcription factors and histone modification patterns, shedding light on mechanisms underlying tumorigenesis [11]. The method's exceptional resolution and coverage have revolutionized our ability to decode genomic complexity, offering researchers unprecedented avenues to elucidate fundamental biological processes and disease mechanisms [11] [12].

Core Principles of ChIP-seq

Fundamental Mechanisms

At its core, ChIP-seq functions on the principle of capturing and sequencing protein-DNA interactions preserved under physiological conditions. The methodology begins with chemical cross-linking of proteins to DNA within living cells, effectively freezing these interactions in their native state [11] [13]. The cross-linked chromatin is then fragmented into manageable pieces, typically ranging from 200-600 base pairs, through either sonication (physical shearing) or enzymatic digestion [11]. Antibodies with high specificity for the target protein or histone modification are then employed to immunoprecipitate the protein-DNA complexes of interest, selectively enriching for fragments bound by the target [11]. Following immunoprecipitation, the cross-links are reversed, and the purified DNA fragments are prepared for high-throughput sequencing [11]. The millions of short sequencing reads generated are subsequently aligned to a reference genome, enabling comprehensive mapping of protein binding sites or histone modifications across the entire genome [11].

Key Methodological Variations

Several methodological variations of ChIP-seq have been developed to address specific research needs. Cross-linked ChIP (X-ChIP) utilizes formaldehyde cross-linking to stabilize protein-DNA interactions and is particularly suitable for transcription factors and other non-histone proteins [12] [13]. Native ChIP (N-ChIP), in contrast, avoids cross-linking and uses micrococcal nuclease digestion under gentle conditions to preserve the native chromatin structure, making it ideal for studying histone modifications [12] [13]. While N-ChIP provides high antibody specificity and preserves native chromatin structure, it is unsuitable for non-histone proteins and carries a risk of nucleosome rearrangement during sample preparation [13]. More recently, indexing-first ChIP (iChIP) has emerged, employing a barcoding strategy to index chromatin fragments before immunoprecipitation, enabling multiplexing of samples for high-throughput studies and reducing variability between samples [13].

Comprehensive ChIP-seq Workflow

Experimental Procedures

The standard ChIP-seq protocol encompasses multiple critical stages, each requiring optimization for successful outcomes. The initial stage involves cross-linking and chromatin extraction, where cells are treated with formaldehyde to covalently link proteins to DNA, preserving their interactions [11] [13]. This cross-linking process is time-dependent, typically ranging from 2-30 minutes, and requires careful optimization as excessive cross-linking can hinder antigen accessibility and sonication efficiency [13]. The reaction is terminated using glycine, which quenches the formaldehyde [13].

Following cross-linking, chromatin fragmentation is performed to generate appropriately sized DNA segments. This is typically achieved through either sonication (using ultrasonic waves) or enzymatic digestion with micrococcal nuclease (MNase) [11] [12]. Sonication generally produces fragments ranging from 200-600 base pairs, while MNase digestion preferentially cleaves linker DNA, leaving nucleosomes intact and providing more precise mapping for histone modification studies [12]. The choice between these methods represents a critical consideration: sonication is preferred for transcription factor studies, while MNase digestion is often superior for nucleosome positioning and histone modification analysis [12].

The immunoprecipitation step follows, where an antibody specific to the target protein or histone modification is used to selectively enrich the DNA-protein complexes [11]. The quality and specificity of the antibody are paramount to the success of the experiment, as they directly determine the specificity of the enrichment [11]. These complexes are precipitated from the solution using beads coated with Protein A or G, facilitating separation from the remaining chromatin constituents [13].

After immunoprecipitation, DNA purification and library preparation are performed. The protein-DNA complexes undergo reverse cross-linking to separate DNA from proteins [11]. The resulting purified DNA fragments are then prepared for high-throughput sequencing through the construction of a sequencing library, which entails adding adapters to the ends of the DNA fragments—a crucial step for facilitating the sequencing process [11]. For low-input samples, PCR amplification may be incorporated to bolster fragment quantity [11].

The final experimental stage involves high-throughput sequencing, where the prepared DNA library undergoes sequencing using next-generation sequencing platforms [11]. This generates millions of short sequencing reads that collectively depict the DNA fragments specifically bound by the protein or histone modification of interest [11]. Current sequencing technologies can generate 100-400 million reads in a single run, with 60-80% typically aligning uniquely to the reference genome [12].

Computational Analysis Pipeline

The computational analysis of ChIP-seq data represents a critical component of the workflow, transforming raw sequencing reads into biologically meaningful information. The process begins with quality assessment and read mapping, where raw sequencing reads are evaluated for quality and aligned to a reference genome [4]. This is followed by peak calling, a fundamental step where enriched regions (peaks) are identified statistically by comparing the ChIP sample to input DNA controls [4] [14]. The complexity of analysis increases significantly for histone modifications with broad genomic footprints, such as H3K27me3 and H3K9me3, which require specialized analytical approaches rather than standard peak-calling methods designed for sharp transcription factor binding sites [14] [15].

Advanced analysis includes chromatin state annotation and differential analysis, which are essential for comparative studies between experimental conditions [4]. The final stage involves biological interpretation, integrating ChIP-seq findings with complementary datasets such as gene expression profiles or genetic variants to derive mechanistic insights [4] [14]. The entire computational process demands robust bioinformatics infrastructure and expertise, utilizing programming languages like Python and R along with specialized packages available through platforms such as Bioconductor [13] [15].

Table 1: Key Computational Tools for ChIP-seq Data Analysis

| Analysis Type | Tool Name | Primary Application | Special Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Analysis | histoneHMM | Broad histone marks (H3K27me3, H3K9me3) | Bivariate Hidden Markov Model; unsupervised classification |

| Broad Mark Detection | PBS (Probability of Being Signal) | Broad and narrow histone marks | Bin-based approach (5kB bins); gamma distribution background estimation |

| Peak Calling | Multiple available | Transcription factors, sharp histone marks | Identifies statistically significant enriched regions |

| Quality Control | Various | All ChIP-seq data | Assesses mapping ratios, read depth, background signals |

Figure 1: Comprehensive ChIP-seq Workflow Integrating Experimental and Computational Phases

Advantages and Technical Considerations

Comparative Advantages Over Alternative Methods

ChIP-seq offers significant advantages over its predecessor, ChIP-chip (which uses microarrays for detection), establishing it as the preferred method for genome-wide mapping of protein-DNA interactions. A primary advantage is enhanced resolution and coverage—ChIP-seq achieves base-pair resolution, enabling precise mapping of DNA-binding sites, unlike the limitations imposed by fixed probe sequences in array-based methods [11] [12]. This heightened resolution is crucial for identifying subtle yet biologically significant peaks that may be obscured in array-based methods [11].

Additionally, ChIP-seq demonstrates superior noise reduction and increased sensitivity by minimizing inherent noise associated with hybridization-based techniques like ChIP-chip [11]. The elimination of complexities such as cross-hybridization in nucleic acid interactions yields cleaner and more precise data, enabling detection of nuanced protein-DNA interactions that might be overshadowed in array-based assays [11]. Furthermore, ChIP-seq exhibits a compelling dynamic range and linear signal responses, distinguishing it from array-based methods prone to non-linearities and saturation effects [11] [12]. This characteristic is pivotal for accurately quantifying protein-DNA binding affinities and deciphering intricate regulatory mechanisms [11].

The expanded genome coverage afforded by sequencing-based approaches represents another significant advantage. Unlike microarray technologies that are limited to predefined genomic regions, ChIP-seq can theoretically cover the entire genome, including repetitive regions and heterochromatin typically masked out on arrays [12]. This comprehensive coverage is particularly valuable for studies involving heterochromatin organization, repetitive element regulation, and epigenomic mapping in previously inaccessible genomic regions [12].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of ChIP-seq and Related Technologies

| Parameter | ChIP-seq | ChIP-chip | DAP-seq | ATAC-seq |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Base-pair level [12] | Limited by probe density [12] | High [11] | Nucleosome level [11] |

| Coverage | Entire genome [12] | Limited to probe sets [13] | Entire genome [11] | Open chromatin regions [11] |

| Context | Native chromatin [11] | Native chromatin [13] | In vitro [11] | Native chromatin [11] |

| Primary Application | Protein-DNA interactions, histone modifications [11] | Protein-DNA interactions [13] | Transcription factor binding [11] | Chromatin accessibility [11] |

| Sample Requirements | Moderate [16] | Moderate [13] | Low [11] | Low (including single-cell) [11] |

Methodological Challenges and Solutions

Despite its powerful capabilities, ChIP-seq presents several methodological challenges that require careful consideration. Antibody specificity remains a critical factor, as non-specific antibodies can generate false-positive signals and compromise data interpretation [13]. This challenge is particularly relevant for histone modification studies, where similar epitopes or combinatorial modifications may exist. Solution: rigorous antibody validation using appropriate controls, including knockout cells or competitive peptides [13].

The analysis of broad histone modifications like H3K27me3 presents distinctive computational challenges, as these marks form large domains spanning thousands of base pairs rather than sharp, focused peaks [14] [15]. Standard peak-calling algorithms often fail to detect these broad domains effectively. Solution: implementation of specialized analytical tools such as histoneHMM, a bivariate Hidden Markov Model designed specifically for differential analysis of histone modifications with broad genomic footprints [15], or bin-based methods like PBS (Probability of Being Signal) that use larger genomic bins (e.g., 5kB) to identify enriched regions [14].

Tissue-specific adaptations present another challenge, as performing ChIP-seq in solid tissues remains technically demanding due to cellular heterogeneity, complex extracellular matrices, and difficulties in chromatin fragmentation [16]. Solution: development of optimized protocols specifically designed for solid tissues that incorporate simplified and efficient procedures for tissue preparation, chromatin extraction, immunoprecipitation, and library construction [16]. These refined protocols overcome common limitations related to tissue processing and allow for highly reproducible, sensitive, and scalable analysis of disease-relevant chromatin states in vivo [16].

Advanced Applications in Histone Mark Analysis

Mapping Broad Histone Modifications

ChIP-seq has proven particularly valuable for characterizing broad histone modifications that play crucial roles in gene regulation and chromatin organization. The repressive marks H3K27me3 (associated with Polycomb-mediated silencing) and H3K9me3 (linked to constitutive heterochromatin) typically form extensive domains that can span tens to hundreds of kilobases [14] [15]. These broad domains present unique analytical challenges that require specialized approaches beyond conventional peak-calling algorithms [15].

The histoneHMM methodology represents a significant advancement for analyzing such modifications, employing a bivariate Hidden Markov Model that aggregates short-reads over larger regions and uses the resulting bivariate read counts as inputs for unsupervised classification [15]. This approach outputs probabilistic classifications of genomic regions as being either modified in both samples, unmodified in both samples, or differentially modified between samples, without requiring additional tuning parameters [15]. Similarly, the PBS (Probability of Being Signal) method utilizes a bin-based approach, dividing the genome into non-overlapping 5kB bins and calculating a probability score based on a genome-wide background distribution estimated using a gamma distribution fit to the bottom fiftieth percentile of the data [14]. This method transforms ChIP-seq data into universally normalized values that can be readily visualized and integrated with downstream analysis methods [14].

These specialized approaches have enabled important biological discoveries, particularly in developmental biology and disease research. For example, differential analysis of H3K27me3 in cardiovascular disease models has revealed concordantly differentially expressed and modified genes enriched for functional categories such as "antigen processing and presentation," primarily genes from the MHC class I complex—key components of innate immune response [15]. Such findings highlight how ChIP-seq analysis of histone modifications can identify functionally relevant epigenetic changes underlying complex biological processes and disease states.

Integration with Three-Dimensional Genome Architecture

Recent methodological innovations have further expanded ChIP-seq applications to investigate histone modifications within the context of three-dimensional genome organization. Micro-C-ChIP represents a cutting-edge integration of Micro-C (an MNase-based version of Hi-C) with chromatin immunoprecipitation to map 3D genome organization at nucleosome resolution for defined histone modifications [7]. This strategy enables researchers to explore chromosome folding across chromatin domains marked with specific post-translational modifications, providing unprecedented insights into how histone modifications influence and are influenced by spatial genome architecture [7].

The Micro-C-ChIP protocol involves dually crosslinked nuclei that are MNase-digested, followed by biotin labeling of DNA ends and proximity ligation [7]. The ligated chromatin is then sonicated to solubilize the heavily cross-linked chromatin prior to immunoprecipitation with histone modification-specific antibodies [7]. This approach has revealed extensive promoter-promoter contact networks in multiple cell types and resolved the distinct 3D architecture of bivalent promoters in embryonic stem cells [7]. These advancements demonstrate how ChIP-seq methodologies continue to evolve, enabling increasingly sophisticated investigations of epigenetic regulation.

Figure 2: Computational Analysis Workflow for Narrow and Broad Histone Modifications

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ChIP-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde | Cross-linking protein to DNA | Concentration and incubation time require optimization; typically 1% with 2-30 minute incubation [13] |

| Glycine | Quenching cross-linking reaction | Stops formaldehyde cross-linking by reacting with excess formaldehyde [13] |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Chromatin fragmentation (N-ChIP) | Preferentially digests linker DNA; shows sequence bias but provides precise nucleosome mapping [12] |

| Target-specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of protein-DNA complexes | Critical for specificity; require rigorous validation [11] [13] |

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | Capture of antibody-bound complexes | Facilitate separation and washing of immunoprecipitated complexes [13] |

| Sequencing Adapters | Library preparation | Ligated to DNA fragments to enable sequencing on NGS platforms [11] |

| Cell/Tissue Lysis Buffers | Chromatin extraction and preparation | Composition varies based on sample type (cells vs. tissues) [16] [13] |

| DNA Clean-up Kits | Purification of immunoprecipitated DNA | Remove proteins, salts, and other contaminants prior to library preparation [11] |

| Apiorutin | Apiorutin|Flavonoid Glycoside|For Research Use | Apiorutin, a bioactive flavonoid glycoside for diabetes and virology research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Anthecotuloide | Anthecotuloide | Anthecotuloide is a high-purity chemical reagent for research use only (RUO). It is not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. Explore applications and data. |

ChIP-seq technology continues to evolve, with emerging trends pointing toward increasingly sophisticated applications and methodological refinements. The integration of single-cell ChIP-seq methodologies promises to elucidate the cellular diversity within complex tissues and cancers, moving beyond population-average profiles to reveal epigenetic heterogeneity [4]. Similarly, advanced computational approaches leveraging machine learning and data imputation are being developed to predict gene expression levels and chromatin loops from epigenome data, potentially reducing experimental burdens while extracting maximal information from existing datasets [4].

The ongoing refinement of tissue-optimized protocols addresses a critical need in the field, particularly for clinical and translational research where native tissue contexts are essential for understanding disease mechanisms [16]. These protocols overcome challenges related to tissue heterogeneity, complexity of cell matrices, and low input material, enabling highly reproducible, sensitive, and scalable analysis of disease-relevant chromatin states in vivo [16]. Furthermore, the integration of mass spectrometry-based approaches for comprehensive histone modification characterization complements sequencing-based methods, with novel bioinformatics workflows like HiP-Frag enabling identification of previously unexplored epigenetic marks [17].

In conclusion, ChIP-seq has established itself as an indispensable tool for genome-wide mapping of protein-DNA interactions and histone modifications, providing unprecedented insights into epigenetic regulation. Its principles—combining the specificity of immunoprecipitation with the power of next-generation sequencing—have enabled groundbreaking discoveries across diverse biological domains. As the technology continues to mature through improvements in experimental protocols, computational分æžæ–¹æ³•, and integration with complementary approaches, ChIP-seq will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone methodology for deciphering the complex epigenetic mechanisms that govern gene regulation, development, and disease.

Interpreting Histone Modification Patterns in Gene Regulation and Cell Identity

The genetic information encoded in our DNA plays a major role in specifying our individual phenotypes, but it is becoming increasingly clear that epigenetic information is also an important contributor to our mental and physical attributes [18]. Our epigenome—comprising methylated DNA and modified histone proteins—forms the fundamental regulatory layer that interprets genetic sequence information in a cell-type-specific manner. The dynamic modification of DNA and histones plays a key role in transcriptional regulation through altering the packaging of DNA and modifying the nucleosome surface [18]. These chromatin states are distinctive for different tissues, developmental stages, and disease states and can also be altered by environmental influences [18].

Histone modifications influence nucleosome unwrapping and stability to regulate transcription, DNA replication, and DNA repair [19]. Modifications at histone tail regions affect nucleosome unwrapping and stability, while modifications within the nucleosome DNA entry/exit regions affect unwrapping dynamics. Like epigenetic modifications, histone modifications can be propagated during cell division, playing important roles in the development of various types of cells and tissues [19]. Disturbance of this process interrupts normal cellular activity and causes abnormal cell phenotypes, with aberrations in histone modification patterns being common in cancers and other degenerative diseases in humans [19].

Key Histone Modifications and Their Functional Significance

Major Histone Marks in Transcriptional Regulation

Different nucleosomal regions are associated with different transcriptional activities, characterized by distinct sets of modifications on the histone proteins [19]. The table below summarizes the primary histone modifications, their genomic locations, and functional consequences:

Table 1: Key Histone Modifications and Their Functions

| Histone Modification | Genomic Location | Chromatin State | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Promoter regions | Open chromatin | Active transcription initiation; promoter-proximal pause-release [18] [19] |

| H3K4me1 | Enhancer regions | Open chromatin | Active enhancer elements [18] [19] |

| H3K9ac | Promoter regions | Open chromatin | Active transcription [18] |

| H3K36me3 | Transcribed regions | Open chromatin | Transcriptional elongation [18] |

| H3K27me3 | Polycomb target genes | Compacted/Repressive | Repression of developmental genes, particularly homeobox transcription factors [18] |

| H3K9me3 | Heterochromatic regions | Compacted/Repressive | Repression of repetitive elements and zinc finger transcription factors [18] |

Combinatorial Histone Codes

While individual histone marks provide significant information about chromatin state, it is becoming increasingly clear that different combinations of histone marks can provide even more detailed information [18]. For example, the presence of both the open chromatin mark H3K4me3 and the compacted chromatin mark H3K9me3 at a promoter can identify imprinted genes [18]. Similarly, bivalent promoters in embryonic stem cells containing both H3K4me3 (activating) and H3K27me3 (repressing) marks enable rapid activation during differentiation while maintaining a transcriptionally poised state.

The comprehensive cataloging of histone modifications reveals modification hotspot regions and uneven distribution across histone families, suggesting that particular histone families are more susceptible to certain types of modifications [19]. Recent work has identified 6,612 nonredundant modification entries covering 31 types of modifications and 2 types of histone-DNA crosslinks across human histone variants [19], highlighting the tremendous complexity of the histone code.

Experimental Approaches for Histone Modification Analysis

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Followed by Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) has become the method of choice for studying the epigenome [18]. This powerful technology allows investigators to characterize DNA-protein interactions in vivo and generate genome-wide profiles of histone modifications [18]. The fundamental steps involve:

- Crosslinking: Proteins are covalently crosslinked to their genomic DNA substrates in living cells using formaldehyde [18]

- Chromatin Fragmentation: Chromatin is isolated and fragmented, typically by sonication [18]

- Immunoprecipitation: Protein-DNA complexes are captured using antibodies specific to the histone modification of interest [18]

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: After reversal of crosslinks, the ChIP DNA is purified and prepared for high-throughput sequencing [18]

ChIP-seq has generally replaced ChIP-chip for comprehensive epigenomic studies because it can interrogate the entire genome in one sequencing run, whereas multiple DNA microarrays are needed to cover the entire human genome with ChIP-chip [18]. For the study of primary cells and tissues, epigenetic profiles can be generated using as little as 1 μg of chromatin [18].

Figure 1: ChIP-seq Workflow for Histone Modification Analysis

Advanced Methodologies: Micro-C-ChIP and Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches

Recent technological advances have enabled more sophisticated analyses of histone modification patterns. Micro-C-ChIP represents a significant innovation that combines Micro-C (an MNase-based version of Hi-C) with chromatin immunoprecipitation to map 3D genome organization at nucleosome resolution for defined histone modifications [7]. This strategy enriches for specific histone modifications, enabling focus on functionally relevant genomic regions and enhancing the resolution of key regulatory interactions while reducing the sequencing burden on unrelated genomic regions [7].

Mass spectrometry-based approaches have also advanced histone modification detection. The HiP-Frag workflow integrates closed, open, and detailed mass offset searches to enable unrestricted identification of novel epigenetic marks [8]. This approach has identified 60 novel post-translational modifications (PTMs) on core histones and 13 on linker histones purified from human cell lines and primary samples [8], dramatically expanding our understanding of the potential histone code.

Analytical Frameworks for Histone Modification Data

Differential Analysis with histoneHMM

The comparative analysis of histone modification patterns between biological conditions presents unique computational challenges, particularly for modifications with broad genomic footprints such as H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 [15]. Most ChIP-seq algorithms are designed to detect well-defined peak-like features and perform poorly with broad domains [15]. To address this limitation, histoneHMM implements a bivariate Hidden Markov Model that aggregates short-reads over larger regions and takes the resulting bivariate read counts as inputs for an unsupervised classification procedure [15].

histoneHMM outputs probabilistic classifications of genomic regions as being:

- Modified in both samples

- Unmodified in both samples

- Differentially modified between samples

This method has been extensively validated in the context of broad repressive marks (H3K27me3 and H3K9me3) using qPCR, RNA-seq data, and functional annotation analyses, demonstrating superior performance in detecting functionally relevant differentially modified regions compared to competing methods [15].

Normalization Strategies for Enrichment-Based 3D Genome Mapping

For enrichment-based 3D genome mapping methods like Micro-C-ChIP, conventional normalization methods like ICE are inappropriate because they assume equal coverage across genomic regions—an assumption that doesn't hold for enrichment-based methods where coverage varies inherently [7]. To address this challenge, researchers have implemented input-based normalization, leveraging the corresponding bulk Micro-C as an input and using its scaling factors for plotting Micro-C-ChIP contact matrices [7]. This approach accounts for biases inherent to chromatin accessibility, sequencing, and experimental artifacts, ensuring that observed interactions reflect true protein-mediated enrichment rather than general chromatin features [7].

Figure 2: Computational Analysis Pipeline for Histone Modifications

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Histone Modification Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-H3K4me3 | Anti-Tri-Methyl-Histone H3 (Lys4) (C42D8) rabbit monoclonal antibody (CST #9751S) [18] | Marks active promoter regions |

| Anti-H3K27me3 | Anti-Tri-Methyl-Histone H3 (Lys27) (C36B11) rabbit monoclonal antibody (CST #9733S) [18] | Identifies Polycomb-repressed regions |

| Anti-H3K9me3 | Anti-Tri-Methyl-Histone H3 (Lys9) rabbit antibody (CST #9754S) [18] | Targets heterochromatic regions |

| Anti-H3K36me3 | Anti-Tri-Methyl-Histone H3 (Lys36) rabbit antibody (CST #9763S) [18] | Marks transcribed regions |

| Anti-H3K4me1 | Anti-Mono-Methyl-Histone H3 (Lys4) rabbit antibody (Diagenode #pAb-037-050) [18] | Identifies enhancer elements |

| Anti-H3K9ac | Anti-acetyl-Histone H3 (Lys9) rabbit antibody (Millipore #07-352) [18] | Marks active transcription |

| CHHM Database | Curated catalogue of 6,612 nonredundant human histone modifications [19] | Reference resource for modification sites and types |

| histoneHMM Package | R package for differential analysis of broad histone marks [15] | Computational detection of differentially modified regions |

| Micro-C-ChIP Protocol | Combined Micro-C and ChIP methodology [7] | Mapping histone mark-specific 3D chromatin organization |

Biological Insights from Histone Modification Analysis

Promoter-Originating Connectome and 3D Genome Organization

Micro-C-ChIP analyses of H3K4me3-marked chromatin have revealed extensive promoter-promoter contact networks in both pluripotent (mESC) and differentiated cells (hTERT-RPE1) [7]. Precise, narrow H3K4me3 ChIP-peaks at promoter regions translate into fine stripes in 3D space, forming a grid-like structure [7]. These H3K4me3-based interactions serve as a proxy for promoter-originating interactions and provide high-resolution insights into genome organization at low sequencing depth [7].

The application of Micro-C-ChIP to H3K27me3 has enabled resolution of the distinct 3D architecture of bivalent promoters in mESCs [7]. This is particularly important for understanding how developmental genes poised for activation during differentiation are organized in nuclear space.

Differential Modification in Disease and Development

Comparative histone modification analyses have revealed significant insights into disease mechanisms. In a study comparing spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR/Ola) with Brown Norway rats, differential H3K27me3 regions showed significant overlap with differentially expressed genes, with gene ontology analysis revealing enrichment for "antigen processing and presentation" (GO:0019882) [15]. These differentially modified genes were primarily from the MHC class I complex and located in blood pressure quantitative trait loci, providing a direct link between epigenetic variation and disease phenotype [15].

Similarly, analysis of H3K9me3 patterns between male and female mice revealed sex-specific chromatin states, with 121.89 Mb (4.6% of the mouse genome) identified as differentially modified [15]. These findings highlight the role of histone modifications in establishing and maintaining sexually dimorphic gene expression patterns.

The interpretation of histone modification patterns has evolved from cataloging individual marks to understanding their combinatorial complexity and three-dimensional organizational principles. The development of increasingly sophisticated technologies—from ChIP-seq to Micro-C-ChIP and advanced mass spectrometry workflows—has enabled researchers to decode the histone code with unprecedented resolution.

As the field advances, several challenges and opportunities emerge. First, the integration of multi-omic datasets including histone modifications, DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility, and transcriptomics will provide more comprehensive views of epigenetic regulation. Second, the development of single-cell epigenomic technologies will enable the dissection of cellular heterogeneity in development and disease. Finally, the application of these techniques to clinical samples and large patient cohorts holds promise for identifying epigenetic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

The manually curated catalogue of human histone modifications (CHHM) containing 6,612 nonredundant modification entries underscores the tremendous complexity of the histone code [19]. As new modifications continue to be discovered through unrestrictive search strategies like HiP-Frag [8], our understanding of how histone modifications orchestrate gene regulation and cell identity will continue to deepen, opening new avenues for basic research and therapeutic intervention.

Sequencing Depth and Experimental Design Considerations for Different Mark Types

In chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) experiments, sequencing depth—the number of mapped reads obtained—stands as a fundamental parameter determining data quality and biological validity. Within the broader context of histone mark enrichment analysis, insufficient sequencing depth directly compromises the detection of authentic biological signals, leading to incomplete epigenomic profiles and potentially flawed conclusions. The relationship between required depth and histone mark type stems from fundamental differences in their genomic distribution patterns. "Point-source" marks like H3K4me3 produce localized, sharp peaks, while "broad-source" marks such as H3K27me3 form extensive enrichment domains that present distinct detection challenges [20]. This technical guide synthesizes current evidence and consortium standards to establish rigorous experimental design principles for histone mark ChIP-seq, ensuring researchers can obtain statistically robust results while utilizing resources efficiently.

Classification of Histone Marks and Their Genomic Distributions

Categorization by Spatial Distribution

Histone modifications display characteristic genomic distributions that directly influence their experimental requirements. These patterns fall into two primary categories:

Narrow Marks ("Point-source"): These modifications produce sharp, well-defined peaks typically localized to specific genomic loci. Examples include H3K4me3 (active promoters) and H3K27ac (active enhancers and promoters). Their confined distribution makes them relatively straightforward to detect with moderate sequencing depth [20] [21].

Broad Marks ("Broad-source"): These modifications form extensive enrichment domains that can span large genomic regions. Examples include H3K27me3 (Polycomb-mediated repression), H3K36me3 (transcriptional elongation), and H3K9me2/3 (heterochromatin). Their diffuse nature and lower enrichment ratios necessitate greater sequencing depth for comprehensive detection [20] [22] [21].

Biological Functions and Detection Challenges

The biological functions of histone marks directly correlate with their detection challenges in ChIP-seq experiments. Broad repressive marks like H3K27me3 establish facultative heterochromatin over large genomic regions, requiring sufficient depth to map their entire domains accurately. Similarly, H3K36me3 marks associated with transcriptional elongation distribute across gene bodies of actively transcribed genes, while H3K9me3 defines constitutive heterochromatin that often resides in repetitive regions challenging for read mapping [20] [21]. These distinct biological roles translate into specific technical requirements for their robust detection in experimental settings.

Sequencing Depth Recommendations by Mark Type

Empirical Depth Guidelines

Extensive empirical studies have established mark-specific sequencing depth requirements. These recommendations represent practical minimums informed by saturation analyses—the point where additional sequencing yields diminishing returns in peak detection.

Table 1: Recommended Sequencing Depth for Histone Marks in Human Studies

| Histone Mark Type | Example Marks | Recommended Depth (Mapped Reads) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow Marks | H3K4me3, H3K27ac | 20-25 million | Lower depth required due to concentrated signal [22] [21] |

| Mixed/Broad Marks | H3K36me3, H3K4me1, H3K27me3 | 35-45 million | Extended domains require greater coverage [22] [21] |

| Challenging Broad Marks | H3K9me3 | >55 million | Enrichment in repetitive regions demands extra depth [22] [21] |

Factors Influencing Depth Requirements

Sequencing depth requirements depend on several biological and technical factors beyond mark classification:

Genome Size: The human genome (∼3 billion bp) demands significantly greater sequencing depth than smaller genomes like Drosophila melanogaster (∼180 million bp), where 20 million reads often suffices for saturation [20].

Cellular Context: The abundance and distribution of histone marks vary by cell type, developmental stage, and experimental conditions, potentially affecting depth requirements.

Antibody Quality: High-specificity antibodies with strong signal-to-noise ratios reduce background, potentially lowering depth needs compared to less specific reagents [23].

The principle of "sufficient sequencing depth" proposed by Jung et al. defines the optimal depth as the point where detected enrichment regions increase less than 1% for each additional million sequenced reads [20].

Experimental Design Framework

Comprehensive Experimental Considerations

Robust ChIP-seq experimental design extends beyond sequencing depth to encompass multiple critical factors:

Biological Replicates: Independent biological replicates (minimum of two, preferably three) are essential to distinguish technical artifacts from biological variation and ensure reproducibility [22] [23].

Control Experiments: Input chromatin (sonicated, non-immunoprecipitated DNA) serves as the preferred control for normalizing background signal. Input should be sequenced to at least the same depth as ChIP samples, with each ChIP replicate having its own matched input sequenced separately [22] [23].

Library Construction: While single-end sequencing may suffice for narrow marks, paired-end sequencing is recommended for broad marks as it improves mapping confidence and provides direct fragment size measurement without modeling [22].

The following workflow summarizes the key decision points in ChIP-seq experimental design:

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

Cell number requirements vary based on the abundance of the target mark. While one million cells may suffice for abundant marks like H3K4me3, ten million cells may be necessary for less abundant or diffuse modifications [23]. Chromatin fragmentation should yield fragments between 150-300 bp, optimized for each cell type through sonication condition titration [23]. Critical quality metrics include:

- Library Complexity: Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) >0.9, PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients (PBC1 >0.9, PBC2 >10) [21]

- FRiP Score: Fraction of Reads in Peaks, with higher values indicating better signal-to-noise ratio

- Cross-Correlation: Assessing the fragment size distribution and immunoprecipitation quality

Analytical Approaches for Different Mark Types

Peak Calling Strategies

The analytical approach must align with the histone mark characteristics:

Narrow Marks: Standard peak callers like MACS2 perform well for sharp peaks, identifying statistically significant enrichments against background models [20] [21].

Broad Marks: Specialized approaches are necessary for extended domains. Options include:

- Broad Mode Algorithms: MACS2 with "-broad" parameter or SPP with Z-score thresholds [20]

- Segmentation Methods: Tools that identify extended regions of enrichment without strict peak boundaries

- Bin-Based Methods: The Probability of Being Signal (PBS) approach using 5 kb bins to detect broad, low-enrichment regions [14]

The Probability of Being Signal (PBS) Method

For challenging broad marks, the PBS method offers a robust alternative to conventional peak calling. This approach:

- Divides the genome into non-overlapping 5 kb bins

- Fits a gamma distribution to the background from the bottom 50th percentile of bins

- Calculates for each bin a PBS value (0-1) representing the probability of true signal

- Effectively identifies broad domains of H3K27me3 that might evade detection by standard peak callers [14]

The PBS method facilitates comparison across datasets and integration with other genomic data types, providing a normalized metric less sensitive to technical variations [14].

Advanced Methodologies and Emerging Techniques

Micro-C-ChIP for 3D Chromatin Architecture

Recent advancements like Micro-C-ChIP combine Micro-C (an MNase-based version of Hi-C) with chromatin immunoprecipitation to map histone mark-specific 3D genome organization. This approach:

- Targets specific histone modifications (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27me3) to enrich for functionally relevant interactions

- Achieves high-resolution contact mapping at reduced sequencing depth compared to genome-wide methods

- Identifies promoter-promoter contact networks and distinct 3D architecture of bivalent promoters [7]

CUT&Tag as a ChIP-seq Alternative

Cleavage Under Targets & Tagmentation (CUT&Tag) presents an emerging alternative with potential advantages:

- Higher signal-to-noise ratio with approximately 10-fold reduced sequencing depth requirements

- Adaptation to low cell numbers (∼200-fold reduction compared to ChIP-seq)

- Compatibility with single-cell applications [24]

Benchmarking studies show CUT&Tag recovers approximately 54% of ENCODE ChIP-seq peaks for H3K27ac and H3K27me3, primarily capturing the strongest peaks with similar functional enrichments [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents for Histone Mark ChIP-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Considerations & Selection Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of target histone mark | Verify ChIP-grade qualification; test specificity via knockdown/knockout controls; ≥5-fold enrichment in ChIP-PCR recommended [23] |

| Input Chromatin | Background control for normalization | Sonicated, non-immunoprecipitated DNA from same cell population; should be sequenced to same depth as IP samples [22] [23] |

| Chromatin Fragmentation Reagents | DNA fragmentation to optimal size | MNase for histone marks (nucleosome-resolution); sonication for cross-linked factors [23] |

| Library Preparation Kit | Sequencing library construction | Platform-specific protocols; consider compatibility with low-input materials if needed [23] |

| Quality Control Assays | Assessment of sample quality | qPCR for positive/negative control regions; bioanalyzer for fragment size distribution [23] [24] |

| Ilwensisaponin A | Ilwensisaponin A | Ilwensisaponin A is a saponin for research on anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activity. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| CI7PP08Fln | CI7PP08Fln | High-purity CI7PP08Fln for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Sequencing depth represents just one component of a comprehensive experimental framework for histone mark ChIP-seq. The most sophisticated sequencing depth optimization cannot compensate for poor antibody specificity, inadequate controls, or inappropriate analytical methods. As emerging technologies like CUT&Tag and Micro-C-ChIP evolve, they may shift specific technical requirements, but the fundamental principle remains: understanding the biological characteristics of your target histone mark should drive experimental design decisions. By integrating mark-specific sequencing depth recommendations with rigorous experimental practices and appropriate analytical methods, researchers can generate high-quality, biologically meaningful epigenomic datasets that advance our understanding of chromatin-mediated regulation.

Executing Robust ChIP-seq Analysis: Workflows, Tools, and Advanced Techniques

Within the broader context of histone mark enrichment analysis research, the implementation of standardized processing pipelines represents a critical foundation for generating biologically meaningful and reproducible results. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has emerged as a fundamental methodology for mapping protein-DNA interactions genome-wide, with particular importance for understanding histone modifications that define chromatin states and regulate gene expression. The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) Consortium has established comprehensive guidelines and best practices that serve as the gold standard for ChIP-seq data processing, ensuring consistency across laboratories and enabling valid cross-study comparisons.

The critical importance of standardization in ChIP-seq analysis becomes evident when considering the technical variability inherent in the methodology. This variability spans multiple experimental parameters: antibody quality and specificity, chromatin fragmentation efficiency, immunoprecipitation conditions, sequencing depth, and bioinformatic processing choices. Without standardized pipelines, this technical noise can obscure genuine biological signals and complicate the interpretation of histone modification patterns. The ENCODE guidelines address these challenges by providing a unified framework that encompasses experimental design, quality control metrics, computational processing, and data interpretation, thereby enhancing the reliability of conclusions drawn from histone mark enrichment analyses.

ENCODE Quality Control Standards and Metrics

Fundamental QC Parameters for Histone Mark ChIP-seq

The ENCODE Consortium has established rigorous quality control standards that serve as critical checkpoints throughout the ChIP-seq workflow. For histone mark studies, specific considerations must be addressed due to the distinct characteristics of different chromatin modifications. While transcription factor ChIP-seq typically produces sharp, localized peaks, histone modifications can exhibit either sharp peaks (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K27ac) or broad domains (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K9me3), necessitating appropriate analytical adjustments [25]. The consortium recommends specific thresholds for key QC metrics that researchers must meet for data to be considered ENCODE-compliant.

Table 1: ENCODE Quality Control Metrics and Thresholds for Histone Mark ChIP-seq

| QC Metric | Minimum Requirement | Ideal Target | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Depth | 10 million uniquely mapping reads | 20-50 million reads | Sharp histone marks (H3K4me3, H3K27ac) |

| Read Depth | 40 million uniquely mapping reads | >50 million reads | Broad histone marks (H3K27me3, H3K9me3) |

| Library Complexity | >0.8 | >0.9 | All histone marks (10M reads) |

| Normalized Strand Coefficient (NSC) | >5.0 (sharp), >1.5 (broad) | >10 (sharp), >2 (broad) | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| Background Uniformity (Bu) | >0.8 | >0.9 | Read distribution uniformity |

| GC Bias | Similar to reference genome | Human: ~50% | PCR amplification bias assessment |

The rationale behind these thresholds stems from extensive empirical testing. For example, the higher read depth requirement for broad histone marks like H3K27me3 reflects their distribution across large genomic domains and typically lower signal-to-noise ratios compared to sharp marks. Library complexity, measured as non-redundant fraction of reads, ensures that the data is not overly dominated by PCR duplicates, which would limit effective sequencing depth. The Normalized Strand Coefficient (NSC) serves as a key indicator of signal-to-noise ratio, with higher values indicating stronger enrichment [25].

Implementation of QC Assessment Tools

Practical implementation of ENCODE QC standards utilizes established bioinformatic tools. FastQC provides initial assessment of raw sequencing data quality, evaluating parameters including per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, and GC content [26]. For ChIP-seq-specific metrics, the ChiPQC package offers specialized functionality to quantify data quality, including calculation of the fraction of reads in peaks (FRiP) - a crucial metric indicating the proportion of reads falling within enriched regions compared to background [25]. Additionally, the ATACseqQC package, while designed for ATAC-seq data, provides valuable visualizations for assessing TSS enrichment and fragment size distributions that can be adapted for histone ChIP-seq QC [27].

MultiQC enables researchers to aggregate and visualize QC results from multiple tools and samples into a unified report, facilitating rapid assessment of dataset quality across entire projects [26]. This is particularly valuable for large-scale histone mark studies involving multiple samples, conditions, or time points. The implementation of automated QC pipelines that integrate these tools ensures consistent application of ENCODE standards and early detection of potential issues requiring experimental or computational remediation.

Standardized Processing Workflow for Histone Marks

End-to-End ChIP-seq Analysis Pipeline

The ENCODE guidelines specify a comprehensive workflow for processing histone mark ChIP-seq data from raw sequences to identified enrichment regions. This standardized pipeline ensures consistent application of critical processing steps while allowing for mark-specific parameterization where necessary. The workflow encompasses sequential stages of data processing, each with specific tool recommendations and quality checkpoints.

Key Processing Steps and Methodological Details

Read Preprocessing and Alignment: Raw sequencing reads (FASTQ format) first undergo quality assessment using FastQC to identify potential issues including low-quality bases, adapter contamination, or unusual GC content [26]. Adapter trimming and quality filtering are performed using tools such as Trimmomatic or Cutadapt, with specific parameters determined by the sequencing technology and library preparation method [26]. Processed reads are then aligned to an appropriate reference genome using splice-aware aligners such as Bowtie2 or BWA, with output typically in BAM format [25]. The ENCODE standards recommend an alignment rate of at least 70-80% for human genomes, with higher rates expected for less complex genomes.

Peak Calling Strategies for Different Histone Marks: Peak calling represents a critical step where mark-specific considerations are essential. For sharp histone marks such as H3K4me3 and H3K27ac, MACS2 is the most widely used tool, employing a dynamic Poisson distribution to model background and identify statistically significant enrichment regions [25]. For broad marks such as H3K27me3 and H3K9me3, MACS2 should be used with the "broad" option or alternative tools like SICER or BroadPeak that are specifically designed for diffuse enrichment patterns. The ENCODE guidelines emphasize the importance of using matched input DNA controls when available to account for technical artifacts and genomic biases, though computational alternatives exist for input-less peak calling when necessary.

Replicate Concordance and IDR Analysis: A cornerstone of ENCODE standards is the requirement for biological replicates and their assessment using the Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) framework. The IDR method compares peaks between replicates to distinguish consistent, high-confidence enrichment regions from irreproducible noise [25]. This statistical approach evaluates the rank ordering of peaks based on significance measures (e.g., p-values) between replicates, providing a more robust assessment of reproducibility than simple overlap metrics. Implementation typically involves running MACS2 separately on each replicate and the pooled dataset, then applying IDR analysis to identify a consensus set of peaks that meet stringent reproducibility thresholds (commonly IDR < 0.05).

Experimental Protocols for Histone Mark ChIP-seq

Sample Preparation and Sequencing Considerations

The foundation of successful histone mark analysis begins with rigorous experimental execution. While the computational standardization forms the core of ENCODE guidelines, these recommendations are predicated on proper experimental design and execution. Cell line authentication and mycoplasma testing are essential prerequisites to ensure sample integrity. Cross-linking conditions must be optimized for specific histone marks, with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature serving as a standard starting point, though some histone modifications may benefit from alternative cross-linking strategies [25].

Chromatin fragmentation represents a critical step where methodology significantly impacts downstream results. Sonication parameters must be calibrated to yield fragment sizes of 200-500 bp, with evaluation via agarose gel electrophoresis or bioanalyzer traces. Immunoprecipitation employs antibodies with validated specificity for the target histone modification, with ENCODE recommending verification through knockout controls or comparison to established standards when available. Library preparation for sequencing follows standard protocols, though the use of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) is increasingly recommended to accurately quantify and correct for PCR duplicates [25].

Research Reagent Solutions for Histone Mark Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Histone Mark ChIP-seq

| Reagent/Material | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibodies | Specific enrichment of target histone marks | Verify specificity using knockout controls or peptide competition |

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | Antibody-chromatin complex capture | Optimize bead:antibody ratio for efficient pulldown |

| Formaldehyde | Cross-linking protein-DNA interactions | Standard 1% concentration, 10min RT; optimize for specific marks |

| Cell Line Authentication | Sample identity verification | STR profiling to prevent misidentification |

| Mycoplasma Testing | Culture contamination screening | Regular PCR-based monitoring to maintain cell health |

| Size Selection Beads | Library fragment size selection | Adjust ratios to target 200-500bp insert size |

| Sequencing Spike-ins | Normalization control | Use of S. cerevisiae or D. melanogaster chromatin for cross-species normalization |

The selection of validated antibodies represents perhaps the most critical reagent consideration for histone mark ChIP-seq. Antibodies must demonstrate specificity for the target modification through rigorous validation, preferably using orthogonal methods such as western blotting, peptide spot arrays, or knockout/knockdown controls. The ENCODE guidelines strongly recommend referencing the Histone Antibody Specificity Database when selecting reagents and reporting complete antibody information (catalog numbers, lot numbers) to enhance experimental reproducibility [25].

For quantitative comparisons between conditions, the implementation of spike-in controls has emerged as a valuable strategy. These typically involve adding chromatin from a different species (e.g., Drosophila melanogaster) in standardized amounts to each sample before immunoprecipitation. The resulting exogenous reads provide an internal reference for normalizing technical variations in sample handling and sequencing efficiency, enabling more accurate assessment of absolute changes in histone modification levels between conditions [25].

Advanced Applications in Histone Mark Research

Integration with Complementary Epigenomic Assays

The true power of standardized histone mark analysis emerges when integrated with complementary epigenomic datasets. The Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium has established a framework utilizing five "core" histone modifications (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K36me3, and H3K27me3) to define chromatin states genome-wide through computational approaches such as ChromHMM or Segway [25]. These integrative analyses enable the systematic annotation of regulatory elements including promoters, enhancers, transcribed regions, and repressed domains based on specific combinatorial histone modification patterns.

Advanced applications include the prediction of gene expression levels from histone modification patterns, with H3K4me3 and H3K27ac at promoters showing strong correlation with transcriptional activity. Similarly, the integration of histone modification data with chromatin conformation assays (e.g., Hi-C, ChIA-PET) enables the identification of enhancer-promoter looping interactions and topologically associating domains (TADs) [25]. Such integrative approaches provide mechanistic insights into how histone modifications contribute to three-dimensional genome organization and long-range gene regulation.

Single-Cell and Emerging Methodologies

While traditional bulk ChIP-seq measures average histone modification patterns across cell populations, single-cell ChIP-seq (scChIP-seq) methodologies are emerging to resolve cellular heterogeneity in epigenetic states [25]. These approaches present unique computational challenges related to sparsity, technical noise, and data normalization that require extension of the ENCODE standardization principles. Analytical methods developed for bulk data often require significant adaptation or redevelopment for single-cell applications, particularly regarding dimensionality reduction, clustering, and trajectory inference.

The ongoing development of multi-omics approaches that simultaneously profile histone modifications alongside other molecular features (e.g., RNA expression, DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility) in the same single cells represents the frontier of epigenetic analysis. While these methodologies currently fall outside established ENCODE guidelines, they will undoubtedly incorporate the fundamental principles of standardization, quality control, and reproducibility that define the current best practices for bulk histone mark ChIP-seq analysis.

The ENCODE guidelines for standardized ChIP-seq processing pipelines have fundamentally transformed the analysis of histone mark enrichment by establishing community-wide standards that ensure data quality, analytical reproducibility, and cross-study comparability. As the field continues to evolve with emerging technologies including single-cell epigenomics, spatial chromatin profiling, and multi-modal integration, the core principles embodied by the ENCODE framework - rigorous quality control, appropriate analytical methods for different data types, transparent reporting, and data sharing - will remain essential for advancing our understanding of chromatin biology and its role in health and disease.

The ongoing development of computational methods will need to address several emerging challenges in histone mark analysis, including improved normalization strategies for heterogeneous samples, enhanced algorithms for broad domain detection, and standardized approaches for single-cell and multi-omics data integration. Throughout these technological advances, maintaining commitment to the principles of standardization and reproducibility established by the ENCODE Consortium will ensure continued progress in deciphering the complex language of histone modifications and their functional consequences for genome regulation.