A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Analysis: From Basics to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a complete overview of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Analysis: From Basics to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a complete overview of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational concepts, from the basic principles and technological evolution of scRNA-seq to its transformative applications in identifying novel drug targets, understanding disease mechanisms, and stratifying patients. The guide also delves into critical methodological steps, including data preprocessing, cell type identification, and trajectory analysis, while offering practical solutions for common analytical challenges like batch effects and data sparsity. Finally, it presents a comparative evaluation of different scRNA-seq protocols and computational tools, empowering readers to select the most appropriate strategies for their research goals and efficiently translate data into biological insights.

Understanding the Single-Cell Revolution: Principles and Potential

What is scRNA-seq? Moving Beyond Bulk Sequencing to Uncover Cellular Heterogeneity

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a paradigm shift in genomic analysis, enabling researchers to investigate gene expression profiles at the ultimate resolution of individual cells. This transformative technology has revealed unprecedented insights into cellular heterogeneity, rare cell populations, and dynamic biological processes that were previously obscured by bulk RNA sequencing approaches. This technical review provides a comprehensive overview of scRNA-seq methodologies, analytical frameworks, and applications tailored for research scientists and drug development professionals. We examine the complete experimental workflow from single-cell isolation to data interpretation, compare platform capabilities, and explore cutting-edge applications in oncology, immunology, and developmental biology that are advancing precision medicine.

Traditional bulk RNA sequencing measures the average gene expression across populations of thousands to millions of cells, masking the fundamental biological reality of cellular heterogeneity [1] [2]. Even within seemingly homogeneous cell populations, individual cells exhibit remarkable variations in gene expression patterns, metabolic states, and functional properties due to stochastic biochemical processes, microenvironmental influences, and distinct differentiation trajectories [3] [4]. The limitations of bulk approaches became particularly evident in complex biological systems like tumors, neural tissues, and developing embryos, where critical rare cell populations and continuous transitional states drive physiological and pathological processes [2] [5].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) emerged in 2009 as a groundbreaking approach to dissect this complexity by quantifying the complete set of RNA transcripts within individual cells [1] [6]. Since this foundational breakthrough, scRNA-seq technologies have evolved rapidly, with significant improvements in throughput, sensitivity, and accessibility [1] [4]. The core innovation of scRNA-seq lies in its ability to uncover cellular heterogeneity, identify rare cell types, and reconstruct developmental trajectories at single-cell resolution, providing insights that are transforming our understanding of biology and disease mechanisms [3] [6].

Technical Foundations: From Bulk to Single-Cell Resolution

Fundamental Limitations of Bulk RNA Sequencing

Bulk RNA sequencing analyzes RNA extracted from entire tissue samples or cell populations, producing a composite expression profile that represents the population average [2] [5]. While this approach has proven valuable for identifying differentially expressed genes between conditions and has lower cost and simpler data analysis, it possesses inherent limitations:

- Masking of cellular heterogeneity: Expression signals from rare but biologically important cell types (e.g., cancer stem cells, rare immune subsets) are diluted beyond detection in bulk measurements [5]

- Inability to detect cellular subtypes: Distinct subpopulations with different expression patterns are averaged together, obscuring potentially important biological classifications [2]

- Loss of correlated expression information: Co-expression patterns that exist only in specific cell subpopulations cannot be distinguished from random co-variation across cells [6]

These limitations are particularly problematic in complex tissues like tumors, where cellular heterogeneity is a fundamental driver of therapy resistance and disease progression [2].

The scRNA-seq Advantage: Capturing Cellular Diversity

scRNA-seq overcomes these limitations by profiling individual cells, enabling researchers to:

- Identify novel cell types and states based on global expression patterns

- Characterize continuous transitional states during cellular differentiation

- Map the composition of complex tissues and tumor microenvironments

- Discover rare cell populations that may have critical functional roles

- Analyze cell-to-cell variability in gene expression (expression stochasticity) [6] [5]

Table 1: Key Technical Differences Between Bulk RNA-seq and scRNA-seq

| Feature | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average | Individual cell level |

| Cellular Heterogeneity Detection | Limited | High |

| Rare Cell Type Detection | Masked | Possible |

| Cost per Sample | Lower (~$300) | Higher (~$500-$2000) |

| Data Complexity | Lower | Higher |

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | Higher | Lower |

| Sample Input Requirement | Higher | Single cell |

| Applications | Differential expression, splicing analysis | Cell typing, heterogeneity analysis, developmental trajectories |

Core scRNA-seq Methodologies: Experimental Workflows

Single-Cell Isolation and Capture

The initial critical step in any scRNA-seq workflow involves isolating viable single cells from tissues or culture systems. Multiple approaches have been developed, each with distinct advantages and limitations [4]:

- Manual cell picking: Utilizes micromanipulation under microscopic visualization for precise selection of specific cells, particularly useful for rare cells but low throughput [4]

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Employs antibody-conjugated fluorescent markers to sort cells based on surface proteins, offering high throughput but requiring large cell numbers [3] [4]

- Microfluidic technologies: These represent the most advanced approaches, with droplet-based systems (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium) enabling high-throughput encapsulation of thousands of single cells in nanoliter droplets containing barcoded beads [7] [6]

- Laser capture microdissection: Allows precise isolation of individual cells from tissue sections without dissociation, preserving spatial context but with lower throughput [4]

Each method presents trade-offs between throughput, viability, cost, and compatibility with downstream applications, requiring researchers to match isolation techniques to their specific biological questions [6].

Library Preparation and Molecular Barcoding

Following single-cell isolation, the scRNA-seq workflow involves several molecular biology steps to convert minute quantities of cellular RNA into sequencer-compatible libraries:

- Cell lysis and reverse transcription: Individual cells are lysed, and mRNA molecules are captured by poly(T) primers containing unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and cell barcodes [7] [1]

- cDNA amplification: The resulting cDNA is amplified using PCR or in vitro transcription (IVT) to generate sufficient material for sequencing [1]

- Library preparation: Sequencing adapters are added to create final libraries compatible with next-generation sequencing platforms [6]

A critical innovation in scRNA-seq is the implementation of cellular barcoding and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs). Cellular barcodes allow pooling of thousands of cells while maintaining the ability to attribute sequences to their cell of origin, while UMIs enable accurate quantification by distinguishing biological duplicates from PCR amplification artifacts [3] [6].

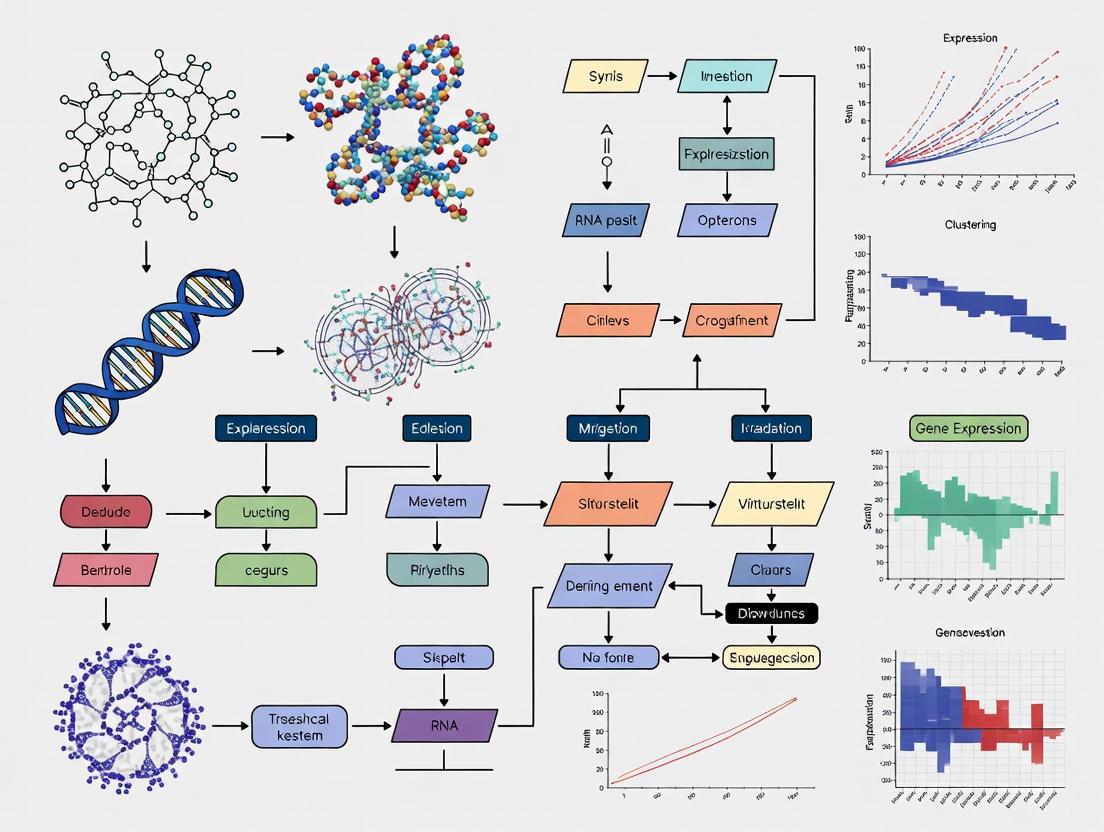

scRNA-seq Experimental Workflow

Commercial scRNA-seq Platforms and Technologies

Several established commercial platforms have standardized scRNA-seq workflows, making the technology accessible to non-specialist laboratories:

- 10x Genomics Chromium: Utilizes microfluidic chips to generate Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) containing single cells, barcoded beads, and RT reagents, currently powered by GEM-X technology with enhanced cell throughput and reduced multiplet rates [7]

- Fluidigm C1: Employs integrated fluidic circuits for automated cell capture, lysis, and library preparation with high sensitivity but lower throughput [6]

- BD Rhapsody: Uses microwell-based cell capture with magnetic bead loading for targeted and whole-transcriptome analysis [6]

The field continues to evolve with newer approaches like split-pool barcoding methods that enable even higher throughput while reducing costs by combinatorially labeling cells across multiple rounds of barcoding [3].

Table 2: Comparison of scRNA-seq Platform Capabilities

| Platform | Throughput (Cells) | Key Technology | Sensitivity | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium X | 80K-960K cells per run | Droplet-based (GEM-X) | Moderate | Large-scale atlas projects, tumor heterogeneity |

| Fluidigm C1 | 96-800 cells per run | Integrated fluidic circuit | High | Detailed single-cell analysis, alternative splicing |

| Smart-seq2 | 96-384 cells per plate | Plate-based, full-length | Very high | Isoform analysis, mutation detection |

| Split-pool Methods | >1 million cells | Combinatorial barcoding | Lower | Massive-scale studies, organ atlases |

Analytical Frameworks: From Sequences to Biological Insights

Primary Data Processing and Quality Control

The computational analysis of scRNA-seq data begins with processing raw sequencing reads into gene expression matrices while accounting for technical artifacts:

- Demultiplexing and alignment: Sequencing reads are assigned to their cell of origin using cellular barcodes and aligned to a reference genome [7]

- UMI counting: Digital gene expression matrices are constructed by counting unique molecular identifiers for each gene and cell, providing noise-resistant quantification [3]

- Quality control metrics: Cells are filtered based on quality thresholds including total UMIs, genes detected, and mitochondrial percentage to remove damaged cells or empty droplets [6]

Multiple computational tools have been developed specifically for these processing steps, including the widely-used Cell Ranger pipeline from 10x Genomics, which transforms barcoded sequencing data into analysis-ready expression matrices [7].

Dimensionality Reduction and Cell Type Identification

The high-dimensional nature of scRNA-seq data (measuring 10,000+ genes across thousands of cells) necessitates specialized computational approaches:

- Dimensionality reduction: Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and non-linear methods (t-SNE, UMAP) project data into 2D or 3D space for visualization and exploration [3]

- Clustering analysis: Graph-based or centroid-based algorithms identify groups of cells with similar expression patterns, representing distinct cell types or states [3] [8]

- Differential expression testing: Statistical methods identify genes that are significantly enriched in specific clusters, enabling biological interpretation of cell populations [6]

These analytical steps transform raw expression data into biologically meaningful insights about cellular composition and identity.

scRNA-seq Data Analysis Pipeline

Advanced Analytical Applications

Beyond basic cell type identification, scRNA-seq enables sophisticated analytical approaches:

- Trajectory inference and pseudotime analysis: Algorithms reconstruct developmental trajectories by ordering cells along differentiation paths based on expression similarity [6]

- Gene regulatory network inference: Computational methods reverse-engineer transcription factor regulatory relationships from expression covariation across cells [6]

- Cellular interaction analysis: Tools like scGraphformer use graph neural networks to model cell-cell communication networks from expression data [8]

These advanced applications extract deeper biological insights regarding developmental processes, disease mechanisms, and cellular decision-making.

Research Applications: Transforming Biomedical Science

Cancer Biology and Tumor Microenvironment Dissection

scRNA-seq has revolutionized cancer research by enabling detailed characterization of tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment:

- Intra-tumor heterogeneity: scRNA-seq reveals distinct subpopulations of cancer cells within individual tumors, including rare treatment-resistant populations [2]

- Tumor microenvironment mapping: Comprehensive profiling of immune, stromal, and endothelial cells within tumors reveals complex cellular ecosystems [2]

- Therapy resistance mechanisms: Identification of rare cell states associated with drug tolerance and resistance, enabling development of combination therapies [2]

For example, scRNA-seq studies of metastatic lung cancer have uncovered plasticity programs induced by cancer cells, while analyses of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma have identified partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition programs associated with metastasis [2].

Immunology and Immune Cell Diversity

The immune system represents a paradigm of cellular heterogeneity, making it ideally suited for scRNA-seq investigation:

- Novel immune subset discovery: scRNA-seq has identified previously unrecognized dendritic cell, monocyte, and T-cell subsets with distinct functional properties [5]

- Immune activation states: Characterization of continuous activation and differentiation states within immune cell populations [6]

- Antigen receptor diversity: Paired with V(D)J sequencing, scRNA-seq enables correlation of clonotype with cellular state in lymphocytes [6]

These applications have particular relevance for immunotherapy development, where understanding the dynamics of immune cell states in response to treatment is critical for improving therapeutic outcomes.

Developmental Biology and Cellular Differentiation

scRNA-seq provides an unprecedented window into developmental processes by capturing transitional cellular states:

- Developmental atlas construction: Comprehensive maps of embryonic and fetal development at cellular resolution across multiple organ systems [6]

- Lineage tracing: Reconstruction of developmental trajectories and lineage relationships from progenitor to differentiated cells [6]

- Stem cell differentiation: Characterization of heterogeneity in stem cell populations and identification of differentiation pathways [5]

These applications have been particularly powerful in neurobiology, where scRNA-seq has revealed unprecedented diversity of neuronal and glial cell types and states [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for scRNA-seq

| Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Isolation Reagents | Collagenase/Dispase enzymes, FACS antibodies, Viability dyes | Tissue dissociation and cell preparation | Optimization required for different tissue types; potential for stress response genes |

| Commercial Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium, Fluidigm C1, BD Rhapsody | Single-cell partitioning and barcoding | Throughput, cost, and sensitivity trade-offs |

| Library Prep Kits | SMARTer kits, Nextera XT | cDNA amplification and library construction | Compatibility with sequencing platform; UMI incorporation |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, NextSeq; PacBio; Oxford Nanopore | High-throughput sequencing | Read length, depth, and cost considerations |

| Analysis Software | Cell Ranger, Seurat, Scanpy, SCANPY | Data processing and visualization | Computational resources required; coding expertise |

| Bimesityl | Bimesityl|High-Purity Research Chemical|RUO | Bimesityl: A high-purity organic compound for research use only (RUO). Explore its applications as a key ligand and synthetic building block. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Parsalmide | Parsalmide, CAS:30653-83-9, MF:C14H18N2O2, MW:246.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

The scRNA-seq field continues to evolve rapidly with several promising technological developments:

- Multi-omics integration: Combining scRNA-seq with measurements of DNA methylation (scNMT-seq), chromatin accessibility (scATAC-seq), and protein expression (CITE-seq) from the same single cells [3]

- Spatial transcriptomics: Integrating single-cell resolution with spatial context through technologies like 10x Genomics Visium and MERFISH [2]

- Computational method advancement: New algorithms like scGraphformer that use transformer-based neural networks to better model complex cell-cell relationships [8]

- Clinical translation: Application of scRNA-seq for biomarker discovery, therapy selection, and disease monitoring in clinical settings [2]

These emerging applications promise to further transform our understanding of cellular biology and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic strategies across diverse disease areas.

Single-cell RNA sequencing has fundamentally transformed our ability to investigate biological systems at their fundamental cellular resolution, revealing unprecedented insights into cellular heterogeneity, developmental processes, and disease mechanisms. While technical challenges remain regarding sensitivity, cost, and computational complexity, ongoing methodological innovations continue to expand the accessibility and applications of this powerful technology. As scRNA-seq approaches become increasingly integrated into both basic research and translational medicine, they promise to accelerate discoveries across immunology, oncology, neuroscience, and developmental biology, ultimately advancing precision medicine through deep molecular characterization of cellular diversity in health and disease.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has fundamentally transformed our capacity to investigate the fundamental unit of biological life—the cell. For decades, transcriptome analysis was confined to bulk RNA-seq, which profiled the average gene expression of thousands to millions of cells, inadvertently masking the unique transcriptional signatures of individual cells [6] [9]. The cellular heterogeneity inherent in complex tissues, from brains to tumors, remained a black box. This limitation was overcome in 2009 with a pioneering study by Tang et al., which marked the birth of single-cell transcriptomics [10]. This breakthrough opened a new avenue for scaling up the number of cells analyzed, making compatible high-throughput RNA sequencing possible for the first time [1].

Framed within a broader thesis on scRNA-seq analysis, this review traces the technical evolution of the field from its conceptual origins to its current status as a mainstream tool in biomedical research and drug development. We explore the key technological advancements that have drastically reduced costs, increased throughput from a single cell to millions per experiment, and enabled the creation of comprehensive cellular atlases [1] [9]. This journey from technical curiosity to indispensable tool underscores how scRNA-seq is now empowering researchers to make exciting discoveries in understanding cellular composition, developmental trajectories, and disease mechanisms [6].

The Foundational Breakthrough: The First scRNA-seq Protocol

The landmark 2009 study by Tang et al., titled "mRNA-Seq whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell," provided the first proof-of-concept that the entire transcriptome of an individual cell could be sequenced [10]. This work established the core experimental paradigm that would underpin all subsequent scRNA-seq methodologies.

Experimental Workflow of the Tang et al. Protocol

The original protocol involved a series of meticulously optimized steps to handle the minute amounts of RNA in a single cell [6] [10]:

- Single-Cell Isolation: A single mouse blastomere or oocyte was manually isolated.

- Cell Lysis: The isolated cell was lysed to release its RNA content.

- Reverse Transcription: The mRNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using an oligo-dT primer that incorporated a template-switching oligo (TSO) sequence. This leveraged the template-switching activity of the reverse transcriptase to add a common sequence to the 3' end of the cDNA.

- cDNA Amplification: The full-length cDNA was then amplified via PCR to generate sufficient material for sequencing.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The amplified cDNA was fragmented, and a sequencing library was constructed for analysis on next-generation sequencing platforms.

A key outcome of this protocol was its dramatic improvement in sensitivity compared to the microarrays available at the time. Tang et al. detected the expression of 75% more genes (5,270 in total) than was possible with microarray techniques from a single mouse blastomere, and identified 1,753 previously unknown splice junctions [10]. This unambiguously demonstrated the complexity of transcript variants at a whole-genome scale in individual cells.

Core Research Reagent Solutions in Tang et al.'s Experiment

The following table details key reagents that enabled this foundational experiment.

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Oligo-dT Primer | Binds to the poly-A tail of mRNA to initiate reverse transcription. |

| Template-Switching Oligo (TSO) | Provides a defined sequence for the reverse transcriptase to add to the 3' end of the cDNA, enabling amplification of all transcripts. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme that converts RNA into more stable cDNA; specific enzymes with template-switching activity are required. |

| PCR Reagents | Nucleotides and polymerase to exponentially amplify the minute amounts of cDNA for sequencing. |

Evolution of scRNA-seq Technologies and Platforms

Following the 2009 breakthrough, the field witnessed a "massive expansion in method development" [11]. These efforts branched into more mature scRNA-seq methods, though the core concept remained the same [1]. The evolution can be categorized by key technological improvements in cell capture and transcript quantification.

Key Technological Advancements

The overarching goal of technological development has been to increase the throughput (number of cells analyzed) while improving quantitative accuracy and reducing costs. The following diagram illustrates the evolutionary trajectory of these platforms.

A critical innovation for improving quantitative accuracy was the introduction of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [1]. UMIs are random nucleotide sequences added to each mRNA molecule during reverse transcription, which allows for the bioinformatic correction of PCR amplification biases, thereby enabling more precise counting of original mRNA molecules [6] [9].

Comparison of Modern High-Throughput scRNA-seq Platforms

The commercialization of droplet-based systems around 2017, such as 10x Genomics, dramatically increased the accessibility of scRNA-seq to the broader research community [12]. The table below summarizes the specifications of some widely used contemporary platforms.

| Platform / Technology | Target Cell Number | Key Input Requirements | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | 500 - 20,000 cells/sample (singleplex) [13] | Fresh or frozen single-cell/nucleus suspensions; fixed cells [13] | 3' and 5' scRNA-seq, immune repertoire profiling, ATAC-seq, Multiome [13] |

| Parse Biosciences | 100,000 - 5,000,000 cells, accommodating up to 384 samples [13] | Fixed single-cell or nucleus suspension [13] | scRNA-seq, scalable for large studies [13] |

| Illumina Single Cell Prep | 100 - 100,000 cells/sample [13] | High-quality single-cell suspension from fresh or cryopreserved cells [13] | 3' scRNA-seq [13] |

| SMART-seq | 1 - 100 cells [13] | 1-10 cells collected in individual tubes [13] | Full-length scRNA-seq and DNA-seq [13] |

The Standardized Modern scRNA-seq Workflow

Despite the diversity of platforms, most contemporary scRNA-seq studies adhere to a general methodological pipeline [6]. The core steps have been streamlined and integrated into user-friendly commercial kits, making the technology more accessible.

From Tissue to Sequencing Data

The modern high-throughput workflow involves a series of interconnected steps, each with critical considerations for data quality.

- Tissue Dissociation and Single-Cell Capture: Tissues are dissociated into a suspension of single cells. A major challenge is minimizing artificial transcriptional stress responses induced by the dissociation process itself. This can be mitigated by performing dissociation at lower temperatures (e.g., 4°C) or by using single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) as an alternative, especially for fragile tissues like the brain [1]. Cells are then captured using high-throughput platforms like droplet-based systems, where each cell is encapsulated in a droplet with a barcoded bead [1] [9].

- Cell Lysis and Barcoded Reverse Transcription: Within the droplet, the cell is lysed, and its mRNA is released. The poly-A tails of the mRNA bind to the poly-T primers on the bead. Each bead contains a unique cell barcode and UMIs. Reverse transcription occurs, creating cDNA molecules that are tagged with the cell barcode and a UMI for each molecule [1] [6].

- cDNA Amplification and Library Preparation: The barcoded cDNA from all cells is pooled. The cDNA is then amplified by PCR to generate sufficient mass for library construction. The final sequencing library is prepared by adding platform-specific adaptors [1].

- Sequencing: The libraries are sequenced on high-throughput next-generation sequencers, typically from Illumina, generating millions of reads where each read contains information about its cell of origin and the specific mRNA molecule it came from [9].

The journey from the first single-cell transcriptome in 2009 to today's high-throughput platforms represents a paradigm shift in biological research. scRNA-seq has matured from a specialized technique to a foundational tool, enabling the construction of detailed cellular atlases of organisms, providing novel biomedical insights into disease pathogenesis, and offering great promise for revolutionizing disease diagnosis and treatment [1].

The future of scRNA-seq lies in its continued evolution and integration with other modalities. Current efforts are focused on pushing the boundaries of multi-omics, where transcriptome data is combined with epigenetic information (e.g., ATAC-seq) from the same single cell [13] [14]. Another frontier is spatial transcriptomics, which preserves the spatial context of gene expression within tissues, thereby bridging the gap between cellular heterogeneity and tissue architecture [11] [14]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence with multi-omics data is poised to unlock deeper biological and clinical insights, particularly in deciphering complex neurological diseases [14].

In conclusion, the history of scRNA-seq is a testament to rapid technological innovation. From its conceptual beginnings with Tang et al., the field has overcome challenges of sensitivity, throughput, and cost to become an indispensable technology. It has provided an unprecedented lens to view the complexity of biological systems, one cell at a time, and continues to be a driving force in the advancement of precision medicine and regenerative medicine [1].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a transformative technological breakthrough that enables the examination of gene expression at the level of individual cells. Unlike traditional bulk RNA sequencing, which averages expression profiles across thousands to millions of cells, scRNA-seq reveals the heterogeneity and complexity of RNA transcripts within individual cells, providing unprecedented resolution for understanding cellular diversity, function, and interactions within tissues and organisms [1] [6]. Since its conceptual debut in 2009, scRNA-seq has rapidly evolved, allowing researchers to classify, characterize, and distinguish cell types at the transcriptome level, leading to the identification of rare but functionally critical cell populations [1] [15]. The technology relies on a sophisticated workflow that integrates single-cell isolation, molecular barcoding, and advanced computational analysis to generate accurate quantitative data from minute amounts of starting material [6]. This technical guide examines the core principles of single-cell isolation, barcoding, and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) that form the foundation of modern scRNA-seq research and its applications in biomedical science and drug development.

Single-Cell Isolation and Capture

The initial and most critical step in any scRNA-seq experiment is the effective isolation of viable, individual cells from the tissue or sample of interest. The method chosen for this process significantly impacts data quality and biological interpretation [1] [6].

Fundamental Isolation Techniques

Single-cell isolation involves separating individual cells from tissue organization or cell culture while maintaining cellular integrity and RNA content. The most common techniques include:

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): This method uses fluorescently labeled antibodies to sort cells based on specific surface markers, providing high purity and the ability to select defined cell populations [1] [6].

- Microfluidic Systems: These platforms employ precisely engineered chips with microscopic channels to isolate individual cells into separate chambers or droplets, enabling high-throughput processing [1] [16].

- Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS): Using magnetic beads conjugated to antibodies, this technique separates cells based on surface markers in a high-throughput manner, though typically with lower resolution than FACS [1].

- Laser Capture Microdissection: This approach uses a laser to precisely isolate specific cells or regions from tissue sections while maintaining spatial context, though with lower throughput than other methods [1] [16].

- Limiting Dilution: A traditional method where cell suspensions are serially diluted until individual wells contain statistically one cell, suitable for low-throughput applications [1].

Advanced Isolation Platforms in 2025

The field of cell isolation has evolved significantly, with current technologies emphasizing higher precision, better scalability, and preservation of native cellular states [16]:

Table 1: Advanced Single-Cell Isolation Methods

| Method | Throughput | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Microfluidics | High (thousands of cells) | Droplet generation, self-optimizing conditions, integrated multi-omic capture | Large-scale single-cell atlas projects, cancer heterogeneity studies |

| AI-Enhanced Cell Sorting | Medium to High | Real-time adaptive gating, morphology-based sorting without labels, predictive state analysis | Rare cell population isolation, stem cell research, clinical diagnostics |

| Spatial Transcriptomics-Integrated | Low to Medium | Maintains architectural context, subcellular precision, location coordinates encoded in data | Tumor microenvironment analysis, developmental biology, neurological circuits |

| Non-Destructive Methods (Acoustic, Optical) | Medium | Maximizes cell viability, label-free separation, minimal cellular stress | Cell therapy manufacturing, live cell biobanking, functional assays |

Technical Considerations and Challenges

Single-cell isolation presents several methodological challenges that researchers must address:

- Artificial Transcriptional Stress Responses: The dissociation process can induce expression of stress genes, potentially altering transcriptional patterns. Performing tissue dissociation at 4°C rather than 37°C and utilizing single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) can minimize these artifacts [1].

- Viability and Integrity: Maintaining cell viability throughout the isolation process is crucial, as compromised cells can release RNA and contaminate the transcriptomic data [6].

- Representation: The isolation method must preserve the original cellular heterogeneity of the sample without introducing selection biases [6].

- Spatial Context Loss: Conventional isolation methods typically discard information about the original spatial organization of cells within tissues, though emerging spatial technologies aim to address this limitation [16].

Molecular Barcoding Strategies

Barcoding technologies form the cornerstone of scRNA-seq, enabling the multiplexing of thousands of individual cells in a single experiment and providing the means to trace sequences back to their cellular origins [17] [18].

Cell Barcodes

Cell barcodes are short oligonucleotide sequences (typically ~16 base pairs) that uniquely label all mRNA molecules from an individual cell [17] [18]. During library preparation, each cell receives a unique barcode sequence through the use of beads or partitions containing distinct barcode combinations. All cDNA molecules generated from a single cell incorporate the same cell barcode, allowing bioinformatic tools to group sequences by cellular origin after sequencing [17]. In droplet-based systems like 10x Genomics, each nanoliter-sized droplet contains a single cell and a barcoded bead, ensuring that all transcripts from that cell share the same barcode [17] [6].

Feature Barcoding

Beyond cell identification, barcoding technology has expanded to capture additional cellular features. Feature barcodes are used to label other molecular aspects, such as cell surface proteins [17]. In this approach, antibodies against specific cell surface targets are conjugated to oligonucleotide barcodes. These tagged antibodies bind to their targets on cells before partitioning, and the feature barcodes are subsequently associated with cell barcodes during the capture process [17]. This enables simultaneous transcriptome and proteome profiling from the same single cell, providing a more comprehensive view of cellular identity and function.

Barcode Implementation in scRNA-seq Protocols

Different scRNA-seq protocols implement barcoding at various stages, with the CEL-Seq2 protocol serving as a representative example [18]. In this paired-end protocol:

- Read 1 contains the barcoding information followed by a polyT tail that binds to the mRNA's polyA tail.

- Read 2 contains the actual cDNA sequence from the transcript.

The barcoding information in Read 1 typically consists of several components: the cell barcode identifying the cell of origin, the UMI identifying the original mRNA molecule, and the polyT sequence for mRNA capture [18]. This structured approach enables precise demultiplexing and accurate quantification during data analysis.

Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs)

UMIs are short, random nucleotide sequences (typically 4-10 base pairs) that provide error correction and enhance quantitative accuracy during sequencing by tagging individual mRNA molecules before amplification [17] [19].

The Purpose and Function of UMIs

The scRNA-seq workflow requires significant amplification of the minute amounts of cDNA derived from single cells, which introduces substantial technical noise and bias [17] [20]. UMIs address this fundamental challenge through several mechanisms:

- Amplification Bias Correction: During PCR amplification, some transcripts are amplified more efficiently than others, creating quantitative distortions. UMIs allow bioinformatics pipelines to identify and count unique molecules rather than total reads, correcting for this amplification bias [17] [18].

- True Variant Discrimination: In variant detection applications, UMIs help distinguish true biological variants from errors introduced during library preparation, target enrichment, or sequencing [19].

- Absolute Quantification: By tagging each original mRNA molecule with a unique identifier, UMIs enable more accurate estimation of transcript abundance in the starting material [17].

Diagram: UMI Workflow for Molecular Counting

UMI Deduplication and Quantitative Analysis

The computational process of UMI deduplication is crucial for accurate gene expression quantification [18]. After sequencing, bioinformatic tools sort reads by their cell barcode and UMI sequence, then collapse reads with identical cell barcode, UMI, and gene mapping into a single count representing one original mRNA molecule [17] [18]. This process effectively distinguishes between technical duplicates (multiple sequencing reads from the same amplified molecule) and biological duplicates (reads from different molecules of the same gene), enabling precise transcript counting [18].

Table 2: Comparison of Quantitative Scenarios With and Without UMIs

| Scenario | Without UMIs | With UMIs | Biological Reality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Even Amplification | Gene A: 4 readsGene B: 4 reads | Gene A: 2 moleculesGene B: 2 molecules | Gene A: 2 transcriptsGene B: 2 transcripts |

| Biased Amplification | Gene A: 6 readsGene B: 3 reads | Gene A: 2 moleculesGene B: 2 molecules | Gene A: 2 transcriptsGene B: 2 transcripts |

| Differential Expression | Gene A: 8 readsGene B: 2 reads | Gene A: 4 moleculesGene B: 1 molecule | Gene A: 4 transcriptsGene B: 1 transcript |

Statistical Advantages of UMI Counting

UMI counting provides significant statistical benefits for scRNA-seq data analysis. Research demonstrates that UMI counts follow a negative binomial distribution, which is simpler to model statistically than read count data that often requires zero-inflated models to account for technical artifacts [20]. This statistical property enables more robust differential expression analysis and improves the detection of true biological signals amidst technical noise [20].

Integrated Workflow and Experimental Design

The power of scRNA-seq technology emerges from the integration of single-cell isolation, barcoding, and UMI strategies into a cohesive workflow. Understanding this integrated process is essential for designing effective experiments and interpreting resulting data.

Comprehensive scRNA-seq Workflow

Diagram: Complete scRNA-seq Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for scRNA-seq

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Microfluidic droplet-based single-cell partitioning | High-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing with integrated cell barcoding |

| BD Rhapsody | Magnetic bead-based cell capture with barcoding | Targeted single-cell analysis with high sensitivity |

| SMARTer Chemistry | mRNA capture, reverse transcription, and cDNA amplification | Full-length transcript coverage with template-switching mechanism |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular barcoding of individual transcripts | Quantitative accuracy by correcting amplification bias |

| Poly[dT] Primers | Capture of polyadenylated mRNA molecules | Selective reverse transcription of mRNA while excluding ribosomal RNA |

| Template Switching Oligo (TSO) | Enable full-length cDNA synthesis | Incorporation of universal adapter sequences during reverse transcription |

| Single-Cell Barcoded Beads | Delivery of cell barcodes to partitioned cells | Cellular demultiplexing in droplet-based systems |

| Perfluorohept-3-ene | Perfluorohept-3-ene, CAS:71039-88-8, MF:C7F14, MW:350.05 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Gambogin | Gambogin, CAS:173792-67-1, MF:C38H46O6, MW:598.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quality Control and Experimental Considerations

Successful scRNA-seq experiments require careful quality control throughout the workflow:

- Cell Viability: Typically >80% viability is recommended to minimize ambient RNA contamination [6].

- Library Complexity: Measured by the number of genes detected per cell and the distribution of UMIs per cell [20].

- Mitochondrial Content: Elevated mitochondrial RNA often indicates stressed or dying cells [6].

- Multiplexing Controls: Using spike-in RNAs or external RNA controls helps monitor technical variability [6].

- Batch Effects: Strategic experimental design should minimize batch effects when processing multiple samples [6].

The core technological principles of single-cell isolation, barcoding, and UMIs form an integrated foundation that enables the precise quantification of gene expression in individual cells. Single-cell isolation methods have evolved from basic techniques to sophisticated platforms that preserve cellular states and increasingly incorporate spatial context [16]. Molecular barcoding strategies allow unprecedented multiplexing capabilities, tracing sequences back to their cellular origins amidst thousands of simultaneously processed cells [17] [18]. UMIs provide the critical quantitative correction needed to overcome the amplification biases inherent in working with minute amounts of starting material, transforming scRNA-seq from a qualitative to a truly quantitative technology [19] [20].

Together, these technologies have created a powerful toolkit for exploring cellular heterogeneity, identifying rare cell populations, understanding developmental trajectories, and unraveling disease mechanisms at unprecedented resolution [1] [6]. As these technologies continue to advance—incorporating multi-omic measurements, spatial context, and computational innovations—they promise to deepen our understanding of biology's fundamental unit, the cell, and accelerate the translation of these insights into clinical applications and therapeutic development [16] [14].

The fundamental unit of life is the cell, and understanding its diversity is a central pursuit in biology. For centuries, classification of the approximately 3.72 × 10^13 cells in the human body relied on morphology and a handful of molecular markers [1]. However, this approach obscured a vast and functionally significant heterogeneity; bulk transcriptome measurements, which average signals across thousands to millions of cells, destroy crucial information and can lead to qualitatively misleading interpretations [21]. The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) represents a paradigm shift, providing an unbiased, high-resolution view of cellular states and their dynamics. For the first time, researchers can assay the expression level of every gene in the genome across thousands of individual cells in a single experiment without the prerequisite of markers for cell purification [21]. This technological revolution is finally making explicit the nearly 60-year-old metaphor proposed by C.H. Waddington, who envisioned cells as residents of a vast "landscape" of possible states, over which they travel during development and in disease [21]. Single-cell technology not only locates cells on this landscape but also illuminates the molecular mechanisms that shape the landscape itself.

This transformative power stems from the technology's ability to overcome fundamental limitations inherent in bulk assays. A key obstacle is Simpson's Paradox, a statistical phenomenon where a trend appears in several different groups of data but disappears or reverses when these groups are combined [21]. In cellular biology, this means that correlations observed in bulk data can be entirely misleading. For instance, a pair of genes might appear negatively correlated in a mixed population, but when the cells are properly separated by type, the genes are revealed to be positively correlated within each subtype [21]. Furthermore, bulk measurements cannot distinguish whether a change in gene expression is due to genuine regulatory shifts within a cell type or merely a change in the relative abundance of cell types in the population [21]. Single-cell genomics circumvents these issues by measuring each cell individually, enabling the precise characterization of cell states and a stunningly high-resolution view of the transitions between them.

Technical Foundations of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

Core Experimental Workflows

The procedures of scRNA-seq involve a series of critical steps designed to capture and amplify the minute amounts of RNA present in a single cell. The primary stages include: (1) single-cell isolation and capture, (2) cell lysis, (3) reverse transcription (conversion of RNA into complementary DNA, or cDNA), (4) cDNA amplification, and (5) library preparation for sequencing [1]. Among these, single-cell capture, reverse transcription, and cDNA amplification are particularly challenging and have been the focus of major technological innovation.

The field has seen a rapid evolution in capture techniques, which significantly determine the scale and type of data that can be obtained. The two most widely used options are microwell-based and droplet-based techniques [22]. Microwell-based platforms, such as the Fluidigm C1 system, transfer cells into micro- or nano-well plates, often using fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS). This allows for visual inspection to exclude damaged cells or doublets but is typically lower in throughput [22]. In contrast, droplet-based methods (e.g., 10x Genomics) use microfluidics to encapsulate individual cells with a barcoded bead in nanoliter-sized droplets. This approach enables extremely high throughput, profiling hundreds of thousands of cells in a single experiment, though with less control over the initial cell input [22].

A critical consideration in sample preparation is the dissociation process. Tissue dissociation into single-cell suspensions can induce artificial transcriptional stress responses, altering the transcriptome and leading to inaccurate cell type identification [1]. For instance, protease dissociation at 37°C has been shown to induce stress gene expression, a issue that can be mitigated by performing dissociation at 4°C [1]. An alternative and increasingly popular method is single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq), which sequences mRNA from the nucleus instead of the whole cytoplasm. snRNA-seq is particularly useful for tissues that are difficult to dissociate (e.g., brain or muscle) or for frozen samples, as it minimizes dissociation-induced artifacts [1].

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for scRNA-seq, highlighting the key steps from tissue to sequencing library.

Key Technological Choices: Protocol Comparisons

The choice of scRNA-seq protocol is not one-size-fits-all; it depends primarily on the scientific question and involves a compromise between cell numbers, informational depth, and overall cost [22] [23]. Two main forms of sequencing techniques exist: full-length and tag-based protocols. Full-length protocols (e.g., Smart-seq2) aim for uniform read coverage across the entire transcript, making them suitable for discovering alternative splicing events, isoform usage, and allele-specific expression [22]. A major disadvantage is the inability to incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs), which are crucial for precise gene-level quantification.

Tag-based protocols (e.g., those used in 10x Genomics), in contrast, only capture either the 5' or 3' end of each RNA molecule. These protocols can be combined with UMIs, which are short random sequences that label each individual mRNA molecule during reverse transcription [1]. This allows for accurate counting of transcript molecules and corrects for amplification biases, thereby improving quantification accuracy. However, being restricted to one end of the transcript makes these protocols less suitable for studies on isoform usage [22].

The following table summarizes the main characteristics of these protocol types to guide experimental design.

Table 1: Comparison of Major scRNA-seq Protocol Types

| Feature | Full-Length Protocols (e.g., Smart-seq2) | Tag-Based Protocols (e.g., 10x Genomics) |

|---|---|---|

| Transcript Coverage | Even coverage across full transcript | Sequences only 5' or 3' end |

| UMI Compatibility | Not possible | Yes, enables precise quantification |

| Isoform/Splicing Analysis | Suitable | Not suitable |

| Primary Applications | In-depth analysis of rare cells, isoform discovery | High-throughput cell type discovery, tissue atlas construction |

| Throughput | Lower (hundreds to thousands of cells) | Very high (tens to hundreds of thousands of cells) |

Computational Analysis of Single-Cell Data

From Raw Data to Biological Insight

The analysis of scRNA-seq data is a multi-step process that transforms raw sequencing reads into interpretable biological findings. Standard data processing can be classified into several key stages: (i) raw data alignment, (ii) quality control and normalization, (iii) data integration and correction, (iv) feature selection, and (v) dimensionality reduction and visualization [22].

Quality control is a vital first step to ensure data reliability. This involves filtering out low-quality cells, which may be identified by a low number of detected genes or a high proportion of mitochondrial reads, indicating cell death or stress [24]. Normalization is then performed to remove technical biases, such as differences in sequencing depth between cells. Methods utilizing UMIs or exogenous spike-in RNAs are particularly effective for this purpose [21] [25].

Due to the high dimensionality of scRNA-seq data (expression levels of thousands of genes per cell), dimensionality reduction techniques are essential for visualization and analysis. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is commonly used to compress the data, followed by methods like t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) or Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) for two- or three-dimensional visualization [22] [24]. These techniques allow cells to be grouped into clusters based on their global transcriptional similarities, with each cluster potentially representing a distinct cell type or state.

A powerful analytical framework for scRNA-seq data is provided by open-source tools such as the R package Seurat and the Python package Scanpy [22]. These toolboxes integrate the various processing steps and provide robust methods for clustering, differential expression analysis, and the discovery of cell type-specific markers.

Advanced Analytical Concepts: Pseudotime and RNA Velocity

Moving beyond static cell type classification, scRNA-seq enables the investigation of dynamic processes such as differentiation and development. Pseudotime analysis is a computational approach that orders individual cells along a trajectory based on their transcriptional progression, effectively reconstructing a developmental continuum from snapshot data [22] [24]. This allows researchers to model the sequence of gene expression changes as a cell transitions from one state to another, for example, from a stem cell to a fully differentiated cell [21].

A related and more recent innovation is RNA velocity, which analyzes the ratio of unspliced (nascent) to spliced (mature) mRNA for each gene to predict the future state of a cell on a timescale of hours [22]. This provides direct insight into the dynamics of gene expression and can reveal the directionality of cell fate decisions, indicating which cell states are transitioning into which others.

The following diagram outlines the key steps in the computational analysis of scRNA-seq data, from raw sequencing output to advanced dynamic modeling.

Key Application: Discovering Novel Cell Types and States

Case Study: Deconstructing the Mouse Crista Ampullaris

A prime example of the power of scRNA-seq in discovering novel cell types and states is the transcriptional profiling of the mouse crista ampullaris, a sensory structure in the inner ear critical for balance [26]. Before this study, the known cellular composition of the crista was limited to a few broad categories: type I and type II hair cells, support cells, glia, dark cells, and several other nonsensory epithelial cells.

Using scRNA-seq on cristae microdissected from mice at four developmental stages (E16, E18, P3, and P7), researchers were able to move beyond this classical taxonomy. Cluster analysis not only confirmed the major cell types but also revealed previously unappreciated heterogeneity within them [26]. For instance, the study identified:

- Two distinct subtypes of hair cells, marked by the specific expression of Ocm (type I) and Anxa4 (type II).

- Two transcriptionally distinct clusters of support cells, both expressing canonical markers like Zpld1 and Otog, but distinguished by the differential expression of genes like Id1.

- Transitional cell states, including a "SC–HC transition" population that co-expressed both support cell and hair cell markers. RNA velocity analysis indicated that these cells were likely in the process of differentiating into type II hair cells, providing a snapshot of active neurogenesis in the postnatal crista [26].

This refined cellular taxonomy was further validated by in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence, which confirmed the spatially restricted expression of the newly discovered marker genes. Furthermore, tracking the proportions of these cell clusters across developmental time revealed dynamic changes, such as a decrease in Id1-positive support cells and an increase in hair cells between E18 and P7, providing a quantitative view of the tissue's maturation [26]. This case study underscores how scRNA-seq can refine existing cell type classifications, reveal continuous developmental trajectories, and identify rare but functionally critical transitional states.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The execution of a successful scRNA-seq experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key components of the experimental toolkit, drawing from the methodologies discussed in the case study and general protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Capture Platform | Physically isolates individual cells for lysis and barcoding. | Droplet-based (10x Genomics), Microwell-based (Fluidigm C1). Choice dictates throughput and cost [22] [1]. |

| Barcoded Beads/Oligos | Uniquely labels all mRNA transcripts from a single cell with a cellular barcode. A UMI labels each molecule to correct for amplification bias. | Essential for multiplexing thousands of cells in a single library [22] [1]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Converts single-cell RNA into first-strand cDNA. | Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (MMLV) RT is common. Template-switching activity is used in some protocols (e.g., Smart-seq2) [1]. |

| PCR/IVT Reagents | Amplifies the tiny amounts of cDNA to a level sufficient for library construction. | Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) or In Vitro Transcription (IVT) are the two main approaches, each with different bias profiles [1]. |

| Library Prep Kit | Prepares the amplified cDNA into a library compatible with next-generation sequencers. | Often platform-specific (e.g., 10x Genomics). Adds sequencing adapters and sample indices [22]. |

| Validated Antibodies & RNA Probes | Used for functional validation of discovered cell types via immunofluorescence (IF) or RNA in situ hybridization (ISH). | e.g., Anti-Id1 and Anti-Myo7a antibodies were used to validate support cell subtypes and hair cells in the crista study [26]. |

| Cesium tellurate | Cesium tellurate, CAS:34729-54-9, MF:Cs2TeO4, MW:457.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pentane-3-thiol | Pentane-3-thiol, CAS:616-31-9, MF:C5H12S, MW:104.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Single-cell RNA sequencing has fundamentally altered our approach to characterizing cellular diversity. By providing an unbiased, high-resolution view of transcriptomes, it has become an indispensable tool for discovering novel cell types, defining transitional states, and reconstructing developmental lineages. As the technology continues to mature, with reductions in cost and increases in throughput and sensitivity, its application will undoubtedly expand.

The future of the field lies in integration. Spatial transcriptomics is a pivotal advancement that addresses a key limitation of standard scRNA-seq: the loss of spatial context due to tissue dissociation [27]. This family of techniques allows for the identification of RNA molecules in their original spatial context within tissue sections, enabling researchers to understand how cellular neighborhoods and geographical location influence cell identity and function [27]. Furthermore, the integration of scRNA-seq with other single-cell modalities—such as epigenomics (ATAC-seq), proteomics, and genomics—will provide a multi-layered, multi-omic view of cellular state, moving beyond the transcriptome to build comprehensive mechanistic models of cell fate regulation.

The ongoing construction of high-resolution cell atlases for humans, model animals, and plants stands as a testament to the power of this technology [1]. These atlases serve as foundational resources for the scientific community, providing a reference framework for understanding normal physiology and the cellular basis of disease. For drug development professionals, the ability to identify rare, disease-driving cell subpopulations or to understand the complex tumor microenvironment at single-cell resolution opens new avenues for therapeutic target discovery and precision medicine. The power of resolution offered by scRNA-seq is not just illuminating the hidden diversity of life's building blocks but is also paving the way for a new era in biomedical research and therapeutic intervention.

From Raw Data to Biological Insights: A Step-by-Step Workflow and Its Impact on Drug Development

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling high-resolution analysis of gene expression at the individual cell level, revealing cellular heterogeneity in complex biological systems [28]. This technology has become indispensable for fundamental and applied research, from characterizing tumor microenvironments to understanding embryonic development [28] [29]. However, the unique nature of scRNA-seq data—characterized by high dimensionality, technical noise, and sparsity—necessitates a robust computational pipeline for meaningful biological interpretation [28] [30].

This technical guide details the core components of the standard scRNA-seq analysis workflow, framed within the context of a broader thesis on scRNA-seq research methodology. We focus specifically on the critical pre-processing stages of quality control, normalization, and dimensionality reduction, which form the foundation for all subsequent biological discoveries. The pipeline transforms raw sequencing data into a structured format ready for exploring cellular heterogeneity, identifying cell types, and uncovering differential gene expression patterns.

The standard computational analysis of scRNA-seq data follows a sequential workflow where the output of each stage serves as the input for the next. While specialized tools exist for specific applications, the core pipeline remains consistent across most studies. The following diagram illustrates the key stages, with this whitepaper focusing on the first three critical components.

Quality Control and Filtering

Objectives and Rationale

The initial quality control (QC) stage aims to distinguish biological signal from technical artifacts by identifying and removing low-quality cells [28] [31]. Technical artifacts primarily arise from two sources: (1) damaged or dying cells that release RNA, resulting in low RNA content and high degradation signatures, and (2) multiple cells captured within a single droplet (doublets or multiplets), which conflate transcriptional profiles from distinct cell types [31]. Effective QC is crucial as these low-quality data points can severely distort downstream analyses, including clustering and differential expression testing.

Key Metrics and Thresholding

QC involves calculating key metrics for each cell and applying appropriate filters. These metrics are computed from the raw count matrix, where rows represent genes and columns represent cells [31].

- Library Size: The total number of reads or UMIs counted per cell. Cells with small library sizes often represent broken or empty droplets.

- Number of Expressed Genes: The count of genes with non-zero expression in a cell. Too few genes suggest a poor-quality cell; too many may indicate a multiplet.

- Mitochondrial Gene Proportion: The percentage of reads mapping to mitochondrial genes. Elevated percentages indicate cellular stress or apoptosis, as mitochondrial membranes rupture more easily during cell death [31].

The table below summarizes these core metrics, their interpretations, and typical filtering strategies.

Table 1: Key Metrics for scRNA-Seq Quality Control

| Metric | Description | Low-Quality Indicator | Common Filtering Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Size | Total UMI counts per cell | Too low: Empty droplet or dead cell | Remove cells in the extreme lower tail of the distribution [31] |

| Number of Genes | Count of genes with >0 UMI per cell | Too low: Poorly captured cellToo high: Multiplets | Remove cells outside an expected range (e.g., 500-5,000 genes) [31] |

| Mitochondrial Ratio | Percentage of UMIs from mitochondrial genes | High: Apoptotic or stressed cell | Remove cells with a percentage significantly above the median [31] |

Practical Implementation

Filtering thresholds are dataset-specific and should be determined by visualizing the distribution of QC metrics across all cells. Tools like CytoAnalyst and Seurat provide interactive interfaces for this purpose, allowing users to dynamically adjust thresholds and observe their effects on the cell population in real-time [31]. After applying filters, the remaining high-quality cells proceed to the normalization stage.

Normalization

The Need for Normalization

Normalization corrects for systematic technical differences between cells to make their gene expression profiles comparable. The primary sources of technical variation include:

- Transcriptome Size Variation: Significant differences in the total RNA content exist across different cell types due to biology (e.g., metabolic activity, cell cycle stage) [32].

- Sequencing Depth: Differences in the total number of reads obtained per cell, which is a technical artifact of the library preparation and sequencing process [32].

A critical challenge is distinguishing biologically meaningful transcriptome size variation from technically induced differences. Failure to account for this can lead to cells clustering by size rather than type.

Common Normalization Methods

The most prevalent method is Counts Per 10 Thousand (CP10K), which scales each cell's counts so that the total counts per cell are equal [32]. While simple and effective for comparing expression within a cell, CP10K assumes all cells have the same "true" transcriptome size. This assumption removes biologically meaningful variation and introduces a scaling effect that can distort comparisons between cell types and confound downstream analyses like bulk deconvolution [32].

Advanced Considerations and the ReDeconv Algorithm

Recent research emphasizes that transcriptome size variation is an intrinsic biological feature that should be preserved when appropriate. The ReDeconv algorithm introduces a novel normalization approach called Count based on Linearized Transcriptome Size (CLTS) designed to correct for technical effects while preserving real biological differences in transcriptome size across cell types [32]. This is particularly important for accurately identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and for using scRNA-seq data as a reference to deconvolute bulk RNA-seq samples, where the scaling effect of CP10K can lead to severe underestimation of rare cell type proportions [32].

Table 2: Comparison of scRNA-Seq Normalization Methods

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Common Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP10K/CPM | Scales counts to a fixed total per cell (e.g., 10,000) | Simple, fast, standard for cell type clustering [32] | Removes biological variation in transcriptome size; causes scaling effect [32] | Seurat, Scanpy [32] |

| SCTransform | Uses regularized negative binomial regression | Models technical noise, improves downstream integration [32] | Computationally intensive; complex parameterization | Seurat |

| CLTS (ReDeconv) | Linearizes transcriptome size based on cross-sample correlations | Preserves biological size variation; improves bulk deconvolution accuracy [32] | Newer method, less integrated into standard pipelines | ReDeconv Package [32] |

Dimensionality Reduction

The "Curse of Dimensionality" in scRNA-Seq

A single scRNA-seq dataset can profile thousands of cells across tens of thousands of genes, creating a high-dimensional space where each gene represents a dimension [30]. Analyzing data in this full space is computationally inefficient and statistically problematic due to the "curse of dimensionality." Furthermore, scRNA-seq data are notoriously sparse, containing a high proportion of zero counts ("dropout events") for genes that are truly expressed but not captured during sequencing [30]. Dimensionality reduction (DR) techniques mitigate these issues by transforming the data into a lower-dimensional space that retains the most biologically relevant information.

Feature Selection and Extraction

DR typically occurs in two stages. First, feature selection identifies a subset of informative genes, usually those with high cell-to-cell variation (Highly Variable Genes or HVGs). This focuses the analysis on genes that are most likely to define cell identities [30]. Second, feature extraction creates a new set of composite "latent variables" by combining the original genes [30].

Core Dimensionality Reduction Techniques

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is a linear, unsupervised technique that performs an orthogonal transformation of the data to create new variables called Principal Components (PCs) [30]. PCs are linear combinations of all original genes that capture decreasing proportions of the total variance in the dataset. The top PCs, which capture the most variance, are retained for downstream analysis, effectively creating a lower-dimensional gene expression matrix with latent genes [30]. The number of PCs to retain is often determined using the "elbow" method on a scree plot [30].

Nonlinear Visualization Methods

While PCA is excellent for initial linear compression, nonlinear methods are preferred for visualization in two or three dimensions.

- t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding): Optimizes the preservation of local structure, making it good for resolving distinct clusters. However, it can be sensitive to parameters and does not preserve global structure (e.g., distances between clusters are not meaningful) [29] [31].

- UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Project): Generally faster than t-SNE and better at preserving both the local and global data structure. It has become the default visualization method in many modern pipelines [29] [31].

Advanced and Emerging Methods

Deep learning approaches are increasingly being applied to DR. Autoencoders (AEs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) are neural networks that compress input data through an "encoder" network into a low-dimensional latent space and then reconstruct it via a "decoder" [30] [29]. They can capture complex nonlinear relationships more effectively than PCA.

A key innovation is the Boosting Autoencoder (BAE), which integrates componentwise boosting into the encoder. This enforces sparsity, meaning each latent dimension is explained by only a small, distinct set of genes [29]. This built-in interpretability helps directly link latent patterns to specific marker genes, moving beyond a "black box" model. The BAE can also be adapted to incorporate structural assumptions, such as expecting distinct cell groups or gradual temporal changes in development data [29].

Table 3: Dimensionality Reduction Techniques for scRNA-Seq Data

| Method | Type | Key Characteristic | Primary Use | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Linear | Finds orthogonal directions of maximum variance | Initial data compression, linear inference [30] | High (component loadings) [29] |

| t-SNE | Nonlinear | Preserves local neighborhood structure | 2D/3D visualization of clusters [31] | Low |

| UMAP | Nonlinear | Preserves local & more global structure | 2D/3D visualization [31] | Low |

| Autoencoder | Nonlinear | Neural network-based compression & reconstruction | Flexible nonlinear DR [30] [29] | Low (typically) |

| Boosting AE (BAE) | Nonlinear | Combines AE with sparse gene selection | Interpretable DR, identifying small gene sets [29] | High (sparse gene sets) [29] ``` |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successfully executing the standard scRNA-seq pipeline requires a combination of wet-lab reagents and dry-lab computational tools. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Tools for scRNA-Seq Analysis

| Category | Item | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short nucleotide tags that label individual mRNA molecules during reverse transcription to correct for PCR amplification bias and enable accurate transcript quantification [28]. |

| Cell Barcodes | Short nucleotide sequences that uniquely label all mRNAs from a single cell, allowing multiplexing and sample demultiplexing after sequencing [28]. | |

| Template-Switching Oligos | Used in SMART-based protocols to ensure full-length cDNA amplification by exploiting the strand-switching activity of reverse transcriptase [28]. | |

| Computational Tools & Platforms | Seurat / Scanpy | Comprehensive R and Python packages, respectively, that provide a complete suite of functions for the entire standard analysis pipeline, from QC to clustering and differential expression [32] [31]. |

| CytoAnalyst | A web-based platform that offers a user-friendly interface for configuring custom analysis pipelines, facilitates team collaboration, and allows parallel comparison of methods and parameters [31]. | |

| ReDeconv | A specialized toolkit for transcriptome-size-aware normalization (CLTS) and improved deconvolution of bulk RNA-seq data using scRNA-seq references [32]. | |

| Cell Ranger | The 10x Genomics official pipeline for processing raw sequencing data (FASTQ) into a gene-cell count matrix, which is the standard starting point for most downstream analyses [31]. | |

| BAE Implementation | A software package for the Boosting Autoencoder, enabling interpretable dimensionality reduction with sparse gene sets for specific biological hypotheses [29]. | |

| N-Isobutylformamide | N-Isobutylformamide|CAS 6281-96-5|C5H11NO | N-Isobutylformamide (N-(2-methylpropyl)formamide) is a chemical compound for research use only (RUO). Explore its properties and applications. |

| Mayosperse 60 | Mayosperse 60|CAS 31075-24-8|Cationic Polymer |

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the characterization of transcriptomes at the fundamental unit of life—the individual cell [6]. This technology moves beyond bulk RNA sequencing, which averages gene expression across thousands to millions of cells, by capturing the high variability in gene expression between individual cells within seemingly homogeneous populations [33] [6]. The ability to profile mRNA levels in individual cells has become a powerful tool for dissecting cellular heterogeneity, identifying previously unknown cell types, revealing subtle transition states during cellular differentiation, and understanding complex biological systems such as tumor microenvironments and immune responses [34] [6].

The core analytical workflow in scRNA-seq analysis revolves around three interconnected processes: clustering cells based on gene expression similarity, identifying marker genes that define distinct cellular populations, and annotating cell types based on these markers [33] [35]. This technical guide explores these fundamental aspects within the broader context of single-cell RNA sequencing analysis research, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for unraveling cellular identity. As the scale and complexity of scRNA-seq datasets continue to grow exponentially, with recent studies profiling over 1.3 million cells, robust and scalable analytical methods have become increasingly crucial for meaningful biological interpretation [36].

Experimental Foundations of scRNA-seq

Technology Platforms and Workflows

ScRNA-seq technologies share common principles but differ in their implementation, each with distinct strengths and limitations. Most platforms involve isolating single cells, capturing their mRNA, reverse transcribing the RNA to cDNA, adding cellular barcodes to track individual cells, amplifying the cDNA, and sequencing [34] [6]. Droplet-based methods, such as DropSeq and the commercial 10X Genomics Chromium platform, use microfluidic chips to isolate single cells along with barcoded beads in oil-encapsulated droplets, enabling high-throughput profiling of thousands of cells simultaneously [34]. These methods employ unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) attached to each transcript during reverse transcription, which allows for accurate digital counting of mRNA molecules by correcting for amplification biases [34].

Alternative approaches include plate-based methods (e.g., Fluidigm C1) that isolate individual cells in nanowells, and split-pooling methods based on combinatorial indexing [6]. The choice of platform significantly impacts downstream analytical decisions and outcomes, as differences in sensitivity, transcript capture efficiency, and cellular throughput can influence the detection of rare cell types and the resolution of cellular heterogeneity [33] [34]. For instance, while 10X Genomics offers high cellular throughput, it typically yields higher data sparsity compared to Smart-seq2, which provides full-length transcript coverage with higher sensitivity but at lower throughput [33].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 1: Key Research Reagents in scRNA-seq Workflows

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(T) Primers | Capture polyadenylated mRNA molecules by binding to poly-A tails | Selective for mRNA; excludes non-polyadenylated RNAs [6] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular barcodes that label individual mRNA molecules | Enable accurate transcript counting by correcting PCR amplification bias [34] |

| Cell Barcodes | DNA sequences that label all mRNAs from a single cell | Allow multiplexing; connect transcripts to cell of origin [34] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes cDNA from mRNA templates | Processivity affects cDNA yield and library complexity [6] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries from amplified cDNA | Commercial kits (e.g., Illumina Nextera) standardize workflow [6] |

Computational Analysis Workflow

The computational analysis of scRNA-seq data follows a structured pipeline that transforms raw sequencing data into biological insights. The quality of results at each stage depends heavily on the proper execution of previous steps.

Diagram 1: scRNA-seq analysis workflow with key stages.

Quality Control and Data Preprocessing

Quality control (QC) forms the critical foundation for all subsequent analyses, ensuring that technical artifacts do not confound biological interpretations. QC metrics are applied to identify and remove low-quality cells while preserving biological heterogeneity [34]. Key parameters include:

- Transcripts per cell: Cells with unusually low or high transcript counts indicate poor capture quality or multiple cells (doublets), respectively. Specific thresholds are experiment-dependent but often exclude cells with fewer than 500 or more than 5,000 transcripts [34].

- Mitochondrial gene content: Elevated proportions of mitochondrial transcripts (often >10-20%) typically indicate stressed, dying, or low-quality cells, as mitochondrial membranes become permeable during apoptosis [34].

- Number of detected genes: Cells with few detected genes may represent empty droplets or low-quality cells, while unexpectedly high numbers may indicate doublets [34].