A Practical Framework for Evaluating Protein Structure Prediction Models in 2025

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate protein structure prediction models. It covers foundational concepts, key evaluation metrics, and practical methodologies for assessing model performance. The content addresses current challenges, including modeling disordered regions and protein complexes, and offers a framework for troubleshooting and comparative analysis using modern benchmarks like DisProtBench and PepPCBench. By integrating validation strategies and confidence metrics, this guide supports reliable model selection for applications in drug discovery and disease research.

A Practical Framework for Evaluating Protein Structure Prediction Models in 2025

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate protein structure prediction models. It covers foundational concepts, key evaluation metrics, and practical methodologies for assessing model performance. The content addresses current challenges, including modeling disordered regions and protein complexes, and offers a framework for troubleshooting and comparative analysis using modern benchmarks like DisProtBench and PepPCBench. By integrating validation strategies and confidence metrics, this guide supports reliable model selection for applications in drug discovery and disease research.

Understanding the Basics: Core Concepts and Evaluation Metrics for Protein Structures

The Sequence-Structure-Function Paradigm and Its Importance in Evaluation

The sequence-structure-function paradigm is a foundational concept in molecular biology, positing that a protein's amino acid sequence determines its three-dimensional structure, which in turn dictates its biological function [1] [2]. For decades, this principle has guided research in structural biology, bioinformatics, and drug discovery, serving as the theoretical basis for predicting protein behavior from genetic information. The paradigm initially operated under the assumption that similar sequences fold into similar structures to perform similar functions, but recent research has revealed a more complex relationship where different sequences and structures can achieve analogous functions [1].

In the context of evaluating protein structure prediction models, this paradigm provides the essential framework for validation. The accuracy of a predicted structure is ultimately validated by how well it explains or predicts the protein's known or hypothesized biological function. This review examines the current understanding of the sequence-structure-function relationship, details experimental methodologies for its evaluation, and discusses its critical importance in assessing the rapidly advancing field of computational protein structure prediction, with a particular focus on AI-based methods that have recently transformed the field [3] [4].

The Evolving Understanding of the Paradigm

From Rigid Hierarchy to Dynamic Relationship

The traditional view of the sequence-structure-function relationship as a linear, deterministic pathway has been substantially refined in recent years. Several key findings have contributed to this evolving understanding:

Functional Diversity from Similar Scaffolds: Large, diverse protein superfamilies demonstrate that a common structural fold can give rise to multiple functions through structural embellishments and active site variations [5]. Some large superfamilies contain more than 10 different structurally similar groups (SSGs) with distinct functional roles [5].

The Challenge of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: A significant proportion of gene sequences code for proteins that are either unfolded in solution or adopt non-globular structures, challenging the assumption that a fixed three-dimensional structure is always necessary for function [6]. These intrinsically unstructured proteins are frequently involved in critical regulatory functions, often folding only upon binding to their target molecules [6].

Sequence-Structure Mismatches: Evidence of chameleon sequences that can adopt multiple structural configurations and remote homologues with different folds complicates the straightforward mapping from sequence to structure [5].

The Continuous Nature of Protein Space

Large-scale structural analyses have revealed that protein structural space is largely continuous rather than partitioned into discrete folds [1] [5]. When representing protein structures as graphs based on C-alpha contact maps and projecting them into low-dimensional space using techniques like UMAP, the resulting protein universe forms a continuous cloud without distinct boundaries between fold types [1]. This continuity highlights the challenge of strictly categorizing protein structures and suggests that functional capabilities may also transition gradually across this space.

Table 1: Key Challenges to the Traditional Sequence-Structure-Function Paradigm

| Challenge | Description | Implications for Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| One-to-Many Sequence-Structure Relationships | Some sequences can adopt multiple stable structures or contain intrinsically disordered regions | Single static models insufficient for evaluating functional predictions |

| Many-to-One Function Mapping | Different sequences and structures can evolve to perform similar functions | Functional assessment cannot rely solely on structural similarity |

| Structural Embellishments | Large insertions/deletions in structurally conserved cores can modify function | Global structure similarity metrics may miss functionally important local variations |

| Continuous Fold Space | Protein structures exist on a continuum rather than in discrete fold categories | Discrete classification systems inadequate for functional annotation |

Quantitative Framework for Evaluating the Paradigm in Structure Prediction

Key Metrics and Benchmarks

The evaluation of protein structure prediction models against the sequence-structure-function paradigm requires multiple complementary metrics that assess different aspects of the relationship:

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating Structure Prediction Models

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Interpretation | Functional Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Structure Quality | TM-score, GDT-TS, RMSD | Measures overall structural accuracy; TM-score >0.5 indicates similar fold, >0.8 indicates high accuracy | High global accuracy suggests correct general fold but doesn't guarantee functional precision |

| Local Structure Quality | lDDT, pLDDT, interface RMSD | Assesses local geometry and stereochemical plausibility | Better indicator of functional site preservation than global metrics |

| Functional Site Preservation | Active site residue geometry, pocket similarity measures (Pocket-Surfer, Patch-Surfer) | Directly evaluates conservation of functionally critical regions | Strongest correlation with functional prediction accuracy |

| Novel Fold Detection | CATH/SCOP novelty, TM-score to known structures | Identifies previously unobserved structural arrangements | Tests ability to predict structures beyond known fold space |

Recent large-scale structure prediction efforts have quantified the current state of protein structure space, identifying approximately 148 novel folds beyond those cataloged in structural databases like CATH [1]. The TM-score metric, with a cutoff of 0.5, has emerged as a standard for determining fold similarity, with scores below this threshold indicating potential novel folds [1].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Large-Scale Structure-Function Mapping

The Microbiome Immunity Project (MIP) demonstrated a comprehensive protocol for large-scale validation of the sequence-structure-function relationship [1]:

Sequence Selection: Curate non-redundant protein sequences from diverse microbial genomes (e.g., GEBA1003 reference genome database) without matches to existing structural databases.

Structure Prediction: Generate multiple structural models using complementary methods (Rosetta, DMPfold) with extensive sampling (20,000 models per sequence for Rosetta).

Quality Assessment: Apply method-specific quality filters (e.g., coil content thresholds: <60% for Rosetta, <80% for DMPfold; model quality assessment scores >0.4).

Functional Annotation: Use structure-based Graph Convolutional Networks (DeepFRI) to generate residue-specific functional annotations.

Novelty Assessment: Compare predicted structures to known folds in CATH and PDB using TM-score cutoffs of 0.5, with verification through independent methods like AlphaFold2.

This protocol successfully predicted ~200,000 microbial protein structures and identified 148 novel folds, demonstrating how large-scale validation can test the boundaries of the sequence-structure-function paradigm [1].

Complex Structure Evaluation

For protein complexes, specialized protocols are required to evaluate interface prediction accuracy [7]:

Paired Multiple Sequence Alignment: Construct deep paired MSAs using sequence-derived structure complementarity information rather than relying solely on co-evolutionary signals.

Interaction Probability Prediction: Use deep learning models (pIA-score) to estimate interaction probabilities between sequences from different subunit MSAs.

Structural Complementarity Assessment: Predict protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score) from sequence information to guide complex assembly.

Interface Accuracy Quantification: Measure interface RMSD and fraction of native contacts recovered in predicted complexes.

The DeepSCFold pipeline has demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach, achieving 11.6% and 10.3% improvement in TM-score over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 respectively on CASP15 targets, and enhancing success rates for antibody-antigen interface prediction by 24.7% and 12.4% over the same methods [7].

Visualization of Key Concepts and Workflows

The Sequence-Structure-Function Evaluation Paradigm

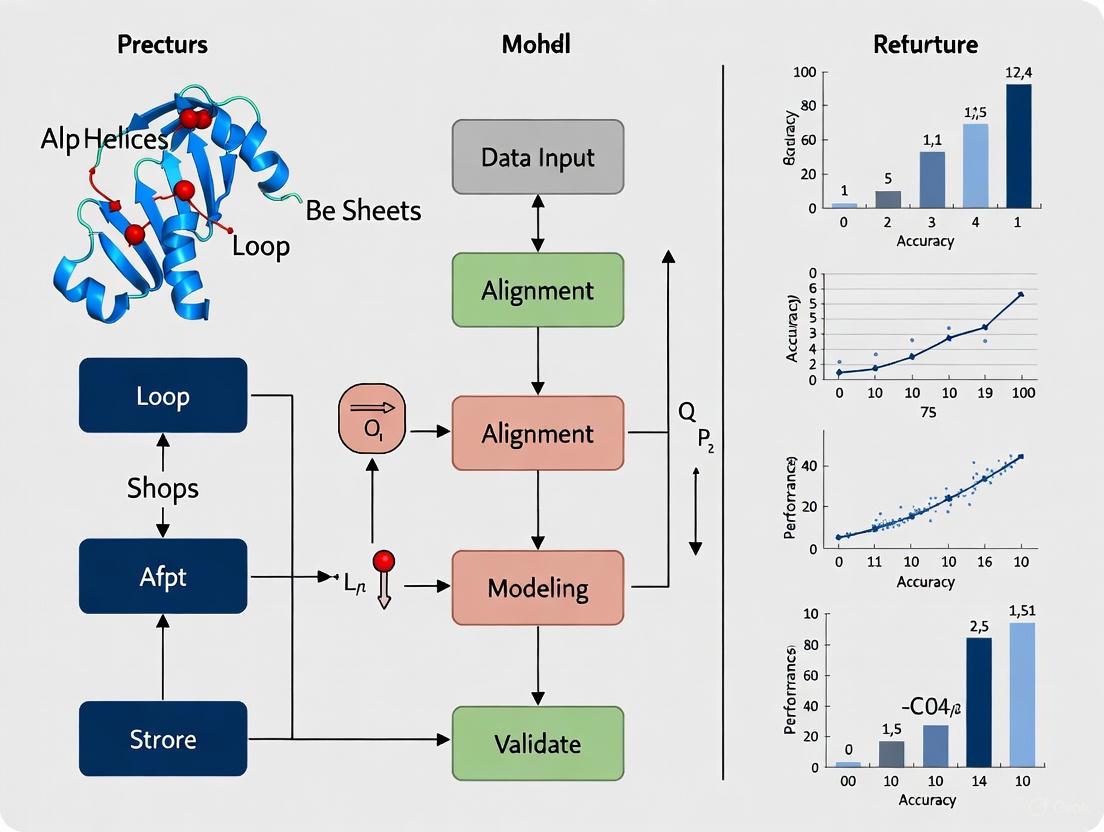

Diagram 1: Sequence-Structure-Function Evaluation

This diagram illustrates the core evaluation paradigm, highlighting both the traditional linear pathway and the modern understanding incorporating challenges like intrinsic disorder and functional plasticity that complicate straightforward sequence-to-function mapping.

Protein Structure Prediction Evaluation Workflow

Diagram 2: Structure Prediction Evaluation

This workflow details the comprehensive evaluation process for protein structure prediction models, highlighting the critical role of functional validation in assessing model performance.

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Sequence-Structure-Function Evaluation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application in Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction Engines | AlphaFold2, AlphaFold3, RoseTTAFold, Rosetta, DMPfold | Generate protein structure models from sequence | Core prediction capability for comparative studies |

| Quality Assessment Tools | MolProbity, Verify3D, ProSA-web, EmaNet (in DGMFold) | Evaluate structural geometry and physicochemical plausibility | Model selection and validation before functional analysis |

| Functional Annotation Resources | DeepFRI, Pocket-Surfer, Patch-Surfer, Catalytic Site Atlas | Predict functional sites and properties from structure | Bridge between predicted structures and functional evaluation |

| Structure-Structure Comparison | TM-align, DALI, CE, STRUCTAL | Quantify similarity between predicted and reference structures | Global and local structural accuracy assessment |

| Specialized Databases | CATH, SCOP, PDB, AlphaFold DB, MIP DB | Provide reference structures and functional annotations | Benchmarking and novelty assessment of predictions |

| Complex-Specific Tools | DeepSCFold, AlphaFold-Multimer, ZDOCK, HADDOCK | Predict and evaluate protein complex structures | Assessment of quaternary structure prediction accuracy |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Fundamental Limitations in Structure-Based Function Prediction

Despite significant advances, several fundamental challenges remain in fully leveraging the sequence-structure-function paradigm for evaluation purposes:

The Dynamic Nature of Protein Conformations: Current AI-based structure prediction methods typically generate single static models, while proteins exist as dynamic ensembles of conformations, especially in functionally relevant regions [3]. The "millions of possible conformations that proteins can adopt, especially those with flexible regions or intrinsic disorders, cannot be adequately represented by single static models" [3].

Environmental Dependence: Protein structures and functions are influenced by their cellular environment, including pH, ionic strength, and binding partners, factors not fully captured by current prediction methods [3].

Limitations of Template-Based Inference: For the approximately one-third of proteins that cannot be functionally annotated by sequence alignment methods, alternative approaches are needed that can extract functional signals from structural predictions even in the absence of clear homology [2] [8].

Emerging Approaches and Methodologies

Promising new directions are emerging to address these challenges:

Integrative Multi-Aspect Learning: Approaches like Protein-Vec that simultaneously learn sequence, structure, and function representations enable more sensitive detection of remote homologs and functional analogies [2]. These systems "provide the foundation for sensitive sequence-structure-function aware protein sequence search and annotation" [2].

Focus on Functional Site Prediction: Methods like Pocket-Surfer and Patch-Surfer that directly compare local structural features of functional sites rather than global folds show promise for predicting function in the absence of global homology [8].

Dynamic and Ensemble Modeling: Increasing emphasis on predicting conformational ensembles rather than single structures may better capture the functional versatility of proteins, especially those with intrinsic disorder or allosteric regulation [3] [6].

Structure-Based Function Prediction: Novel approaches that use predicted structures as input for function prediction models rather than relying solely on sequence information are showing improved performance for detecting remote functional relationships [2].

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with the recent development of AlphaFold3 and open-source alternatives like RoseTTAFold All-Atom and Boltz-1 promising further advances in complex structure prediction [4]. However, the fundamental challenge remains: accurately capturing the dynamic reality of proteins in their native biological environments to enable reliable functional prediction [3]. As these methods improve, the sequence-structure-function paradigm will continue to serve as the essential framework for their critical evaluation, ensuring that advances in structure prediction translate to genuine biological insights and therapeutic applications.

The accurate evaluation of computational protein structure models is a cornerstone of structural bioinformatics, enabling advancements in functional analysis and drug discovery. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of three cornerstone metrics—GDTTS, RMSD, and MolProbity—that form the essential toolkit for assessing model quality. Within the framework of Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP), these metrics offer complementary insights into model accuracy, with GDTTS measuring global fold correctness, RMSD quantifying atomic-level deviations, and MolProbity evaluating stereochemical plausibility. We present standardized methodologies for their calculation, experimental protocols for their application in model selection, and visual workflows to guide researchers in employing these metrics effectively. As protein structure prediction continues to evolve with deep learning methodologies like AlphaFold2, understanding these fundamental assessment tools remains critical for validating models and driving methodological improvements.

Protein structure prediction has emerged as an indispensable complement to experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy, with computational models increasingly informing biological research and therapeutic development [9] [10]. The exponential growth in protein sequence data has dramatically widened the gap between known sequences and experimentally determined structures, making computational modeling not just convenient but essential for leveraging structural information at scale [10]. As the field has progressed, the critical bottleneck has shifted from model generation to model quality assessment (QA), which determines the practical utility of predictions by distinguishing reliable models from incorrect ones [9].

The development and standardization of evaluation metrics occur primarily through CASP, a community-wide blind experiment that has driven progress in the field for over two decades [10] [11]. CASP evaluation recognizes that no single metric can fully capture model quality, leading to the adoption of complementary measures that assess different facets of model accuracy [9] [11]. This whitepaper focuses on three principal metrics—GDT_TS, RMSD, and MolProbity—that collectively provide a multidimensional assessment of protein structure models, balancing global topology, atomic precision, and physical realism.

Core Metrics for Protein Structure Model Evaluation

GDT_TS: Global Distance Test Total Score

GDTTS is a robust measure of global fold correctness that evaluates the structural similarity between a prediction and the native structure. Unlike RMSD, which can be disproportionately affected by small regions with large errors, GDTTS identifies the largest consistent set of residues that superimpose within a series of distance thresholds [11] [12]. The metric is calculated as:

GDTTS = (GDTP1 + GDTP2 + GDTP4 + GDT_P8) / 4

where GDT_Pn denotes the percentage of residues under distance cutoff ≤ n Ångströms [12]. This calculation is performed through multiple superpositions using the LGA (Local-Global Alignment) algorithm to maximize the proportion of Cα atoms that fall within each distance threshold [13].

A related metric, GDTHA (High Accuracy), uses more stringent cutoffs (0.5, 1, 2, and 4 Ã…) to evaluate models that approach experimental resolution [13] [12]. In CASP assessments, GDTTS scores are commonly interpreted as follows: scores above 90 indicate very high accuracy approaching experimental structures; 70-90 represent generally correct folds with some local errors; 50-70 suggest roughly correct topology; and below 50 indicate significant deviations from the native structure [11].

Table 1: GDT_TS Score Interpretation Guidelines

| Score Range | Model Quality | Typical CASP Classification | Utility for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 90 | Very high accuracy | High-accuracy template-based modeling | Suitable for molecular replacement in crystallography, detailed mechanistic studies |

| 70-89 | Correct fold with local errors | Template-based modeling | Reliable for functional annotation, binding site identification |

| 50-69 | Roughly correct topology | Borderline FM/TBM | Useful for fold assignment, low-resolution functional inference |

| < 50 | Significant deviations | Free modeling (FM) | Limited utility; may require further refinement |

RMSD: Root Mean Square Deviation

RMSD measures the average distance between corresponding atoms in superimposed structures, providing a quantitative assessment of atomic-level differences. While conceptually straightforward, RMSD has limitations for global assessment as it is sensitive to outlier regions and can be dominated by small segments with large errors [13]. CASP evaluation employs several RMSD variants:

- RMS_CA: Calculated on Cα atoms using sequence-dependent superposition [12]

- RMS_ALL: Calculated on all atoms using sequence-dependent superposition [12]

- RMSD: Calculated on the subset of Cα atoms that correspond in sequence-independent LGA superposition [12]

For structural biologists, lower RMSD values generally indicate better models, but interpretation must consider the protein size and comparison context. RMSD remains particularly valuable for assessing local structural accuracy and comparing highly similar structures.

MolProbity: Stereochemical Quality Assessment

MolProbity evaluates the physical realism and stereochemical plausibility of protein structures through statistical analysis of high-resolution experimental structures [13] [11]. Unlike GDT_TS and RMSD, which require a native structure for comparison, MolProbity can assess model quality independently, making it particularly valuable for practical applications where the true structure is unknown. The metric combines three components:

- Clashscore: Number of all-atom steric overlaps > 0.4Ã… per 1000 atoms [13]

- Rotamer outlier percentage: Percentage of side-chain conformations classified as outliers [13]

- Ramachandran outlier percentage: Percentage of residues with φ,ψ angles outside favored regions [13]

The final MolProbity score is a composite value where lower scores indicate better stereochemistry [13]. In CASP assessments, MolProbity is incorporated into ranking formulas to ensure selected models are not only accurate but physically realistic [11].

Table 2: Comprehensive Metric Comparison for Protein Model Assessment

| Metric | Calculation Basis | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDT_TS | Largest superimposable residue set at multiple distance thresholds | Robust to local errors; reflects global fold correctness | Less sensitive to local atomic details | Primary model selection, topology assessment |

| RMSD | Average distance between corresponding atoms after superposition | Intuitive interpretation; sensitive to atomic displacements | Disproportionately affected by outlier regions | Local accuracy assessment, comparing similar structures |

| MolProbity | Statistical analysis of high-resolution structures | No native structure required; evaluates physical realism | Does not directly measure accuracy to native | Validating model plausibility, pre-experimental refinement |

Integrated Methodologies for Model Quality Assessment

Experimental Protocol for Comprehensive Model Evaluation

A robust model assessment protocol integrates multiple metrics to balance different aspects of quality. The following workflow represents the standard approach used in CASP evaluations and can be adapted for individual research projects:

Model Preparation: Collect all candidate models for the target protein. Ensure consistent atom naming and residue numbering according to PDB standards.

Structural Alignment: Perform sequence-dependent structural superposition using LGA or similar algorithms to establish residue correspondences between models and native structure [12].

Global Accuracy Assessment:

- Calculate GDT_TS using the four standard distance cutoffs (1, 2, 4, and 8 Ã…)

- Compute GDT_HA for high-accuracy models using stricter cutoffs (0.5, 1, 2, and 4 Ã…)

- Record RMS_CA for Cα atoms after sequence-dependent superposition [12]

Local Quality Evaluation:

Stereochemical Validation:

Comparative Analysis:

Diagram 1: Model quality assessment workflow with key stages.

CASP Ranking Protocol and Z-score Normalization

In CASP evaluations, predictor performance is ranked using normalized scores that enable comparison across diverse targets. The standard approach applies Z-score transformation to mitigate the variable difficulty of different targets [13] [11]. The protocol involves:

- Calculating the mean and standard deviation of a metric (e.g., GDT_TS) for all first models submitted on a target

- Computing initial Z-scores for all models

- Recalculating mean and standard deviation excluding outliers (Z-score > -2.0)

- Computing final Z-scores using the refined statistics

- For metrics where lower values are better (RMSD, MolProbity), inverting the Z-scores so higher values always indicate better quality [13]

The official CASP14 ranking for topology assessment used the formula: 1GDT_TS + 1QCS + 0.1*MolProbity, which balances global accuracy, local alignment quality, and stereochemical plausibility [11].

Table 3: Essential Tools for Protein Structure Model Evaluation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| LGA (Local-Global Alignment) | Algorithm | Structural alignment for GDT_TS calculation | https://predictioncenter.org/ |

| MolProbity | Software Suite | Stereochemical quality assessment | http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu/ |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | Experimental structures for benchmarking | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| CASP Prediction Center | Platform | Assessment results and metrics documentation | https://predictioncenter.org/ |

| AlphaFold DB | Database | Pre-computed models for reference | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

Advanced Considerations in Metric Interpretation

Context-Dependent Metric Selection

The appropriate emphasis on different metrics depends on the research application. For molecular replacement in crystallography, GDT_TS and MolProbity are particularly relevant as they predict the experimental utility of models [11]. For functional site identification, local measures like SphereGrinder and interface-specific scores provide more targeted assessment [13] [7].

Limitations and Complementary Metrics

While GDT_TS, RMSD, and MolProbity form a core assessment toolkit, researchers should recognize their limitations and employ complementary metrics when appropriate:

- LDDT (Local Distance Difference Test): Provides superposition-free assessment by comparing distance maps, valuable for evaluating models without global alignment [13]

- TM-score: Another topology-based measure that is less sensitive to terminal regions [7]

- SphereGrinder: Evaluates local structural similarity by calculating RMSD within 6Å spheres around each Cα atom [13]

- Interface-specific metrics: For protein complexes, measures like iRMSD and DockQ specifically assess binding interface accuracy [7]

Diagram 2: Context-dependent metric selection framework for different research goals.

The multifaceted evaluation of protein structure models using GDTTS, RMSD, and MolProbity provides complementary insights that drive both methodological advancements and practical applications. GDTTS excels at assessing global fold correctness, RMSD provides atomic-level precision measurement, and MolProbity ensures physical realism—together forming a comprehensive assessment framework. As the field evolves with deep learning approaches like AlphaFold2 and its successors [14] [11], these established metrics continue to provide the fundamental benchmarking necessary to validate progress. Researchers should employ these metrics in concert, recognizing their respective strengths and limitations, to make informed decisions about model quality in structural biology and drug discovery applications. The standardized methodologies and protocols presented here offer a roadmap for rigorous, reproducible model evaluation that underpins reliable scientific conclusions.

The advent of sophisticated artificial intelligence systems like AlphaFold2 and its successors has fundamentally transformed the field of protein structure prediction, achieving remarkable accuracy on global distance metrics [15]. These systems have demonstrated performance competitive with experimental methods for many single-chain protein targets, creating an impression within the scientific community that the protein structure prediction problem is largely solved [16]. However, this perception represents a dangerous oversimplification that obscures critical limitations. While global accuracy metrics provide a valuable high-level overview of model quality, they often mask significant deficiencies in biologically crucial regions and functionalities.

This whitepaper argues that a paradigm shift in evaluation methodologies is essential for advancing protein structure prediction from a theoretical exercise to a practical tool for biological discovery and therapeutic development. Global metrics alone provide insufficient insight into model utility for downstream applications. Through systematic analysis of performance gaps in protein complexes, flexible regions, and functional sites, we establish a framework for multi-dimensional assessment that better aligns computational predictions with biological reality. This approach is particularly relevant for researchers in drug development who require accurate structural information for target identification, binding site characterization, and rational drug design.

The Critical Shortcomings of Global Accuracy Measures

The Masked Deficiencies in Protein Complex Prediction

Protein-protein interactions form the foundation of most biological processes, yet current structure prediction methods show substantial performance degradation when modeling complexes compared to single chains. The limitations of global metrics become particularly evident in this context, as they often fail to capture critical errors at interaction interfaces.

Table 1: Performance Gaps in Protein Complex Prediction

| Prediction Method | Global Metric (TM-score) | Interface-Specific Metric | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Baseline | Baseline | Reference |

| AlphaFold3 | -10.3% vs. DeepSCFold | -12.4% success on antibody-antigen interfaces | Significant interface accuracy loss |

| DeepSCFold | +11.6% vs. AlphaFold-Multimer | +24.7% success on antibody-antigen interfaces | Improved interface capture |

As illustrated in Table 1, while global metrics show variations between methods, the discrepancy is markedly more pronounced at interaction interfaces. DeepSCFold demonstrates significantly better performance on antibody-antigen binding interfaces compared to both AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, despite more modest improvements in global TM-score [7]. This indicates that global metrics can conceal substantial deficiencies in critical functional regions.

Independent benchmarking of AlphaFold3 on the SKEMPI 2.0 database, which contains 317 protein-protein complexes and 8,338 mutations, revealed that although AF3-predicted complexes achieved a relatively good Pearson correlation coefficient (0.86) for predicting binding free energy changes, they resulted in an 8.6% increase in root-mean-square error compared to original PDB complexes for binding free energy change prediction [17]. This degradation occurs despite high global accuracy scores, highlighting the disconnect between overall structural correctness and functional precision.

The Flexibility Challenge: Poor Performance in Disordered Regions and Peptides

Intrinsically disordered regions and small peptides represent a significant challenge for structure prediction algorithms, yet their flexibility is often biologically essential. Traditional global metrics heavily penalize structural deviations in these regions without distinguishing between functionally important flexibility and true prediction errors.

Benchmarking AlphaFold2 on 588 peptide structures between 10-40 amino acids revealed distinct patterns of performance degradation. While AF2 predicted α-helical, β-hairpin, and disulfide-rich peptides with reasonable accuracy, it showed several critical shortcomings [18]. The algorithm performed significantly worse on mixed secondary structure soluble peptides compared to their membrane-associated counterparts, and consistently struggled with Φ/Ψ angle recovery and disulfide bond patterns [19].

Most concerningly, the lowest RMSD structures often failed to correlate with the lowest pLDDT ranked structures, indicating that AlphaFold2's internal confidence measure does not reliably identify its most accurate predictions for peptides [18]. This disconnect between confidence metrics and actual accuracy presents a serious challenge for researchers relying on these models without experimental validation.

The Static Conformation Problem: Missing Biological Reality

Proteins are dynamic molecules that sample multiple conformational states to perform their functions, yet current prediction methods typically generate single, static models. A comprehensive analysis comparing AlphaFold2-predicted and experimental nuclear receptor structures revealed systematic limitations in capturing biologically relevant conformational diversity [20].

While AlphaFold2 achieves high accuracy in predicting stable conformations with proper stereochemistry, it shows limited capacity to capture the full spectrum of biologically relevant states, particularly in flexible regions and ligand-binding pockets [20]. Statistical analysis revealed significant domain-specific variations, with ligand-binding domains showing higher structural variability (coefficient of variation = 29.3%) compared to DNA-binding domains (CV = 17.7%) in experimental structures—a diversity that AF2 models fail to replicate.

Notably, AlphaFold2 systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by 8.4% on average and captures only single conformational states in homodimeric receptors where experimental structures show functionally important asymmetry [20]. This has profound implications for drug discovery, as accurate binding site geometry is essential for virtual screening and structure-based drug design.

Beyond Global Scores: A Multi-Dimensional Assessment Framework

Specialized Metrics for Comprehensive Evaluation

Moving beyond global accuracy requires adopting a suite of specialized metrics that evaluate different aspects of model quality relevant to specific research applications.

Table 2: Essential Specialized Metrics for Protein Structure Assessment

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Biological Significance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interface Quality | Interface Contact Score (ICS/F1), ipTM, interface RMSD | Protein-protein interaction accuracy, binding site characterization | Drug discovery, complex analysis |

| Local Quality | pLDDT, per-residue confidence, angular errors | Flexible region accuracy, active site precision | Mutational analysis, enzyme studies |

| Functional Site | Pocket volume, residue geometry, conservation | Ligand binding capability, catalytic functionality | Structure-based drug design |

| Conformational Diversity | Ensemble variation, B-factor correlation | Biological relevance, functional states | Allosteric mechanism studies |

The critical importance of interface-specific metrics is demonstrated by the development of specialized assessment benchmarks like PSBench, which includes over one million structural models annotated with ten complementary quality scores at the global, local, and interface levels [21]. This comprehensive annotation enables developers to identify specific failure modes that global metrics might obscure.

Experimental Protocols for Targeted Benchmarking

Robust validation of prediction methods requires specialized experimental protocols designed to stress-test specific aspects of performance.

Protocol for Protein Complex Interface Assessment

Objective: Quantify accuracy specifically at protein-protein interaction interfaces, which may be obscured by global metrics.

Methodology:

- Dataset Curation: Select diverse protein complexes with known structures, emphasizing non-homologous interfaces to avoid benchmark bias [21].

- Model Generation: Predict structures using multiple state-of-the-art methods (AlphaFold-Multimer, AlphaFold3, DeepSCFold) with consistent settings [7].

- Interface Extraction: Isolate interface residues using distance cutoffs (typically 5-10Ã… between chains).

- Multi-level Evaluation:

- Calculate interface-specific metrics (ICS, ipTM)

- Compute interface RMSD (iRMSD) for structural alignment

- Assess binding site residue geometry

- Evaluate conservation of key interaction motifs

- Functional Correlation: Compare predicted interfaces with experimental binding affinity data or mutational studies when available [17].

This protocol revealed that despite high global accuracy, AlphaFold3 complex structures resulted in an 8.6% increase in RMSE for binding free energy change predictions compared to original PDB structures [17].

Protocol for Flexible Region and Peptide Assessment

Objective: Evaluate performance on intrinsically disordered regions and small peptides where global metrics are particularly misleading.

Methodology:

- Dataset Selection: Curate structured peptides (10-40 residues) with experimental NMR structures, categorized by secondary structure and environment [18].

- Prediction and Ranking: Generate models using both general and specialized predictors, using native confidence metrics for ranking.

- Conformational Analysis:

- Calculate Φ/Ψ angle recovery rates

- Assess disulfide bond geometry accuracy

- Evaluate structural ensemble diversity

- Correlation Analysis: Compare model confidence scores (pLDDT) with actual accuracy metrics to identify discrepancies [19].

Application of this protocol demonstrated that AlphaFold2's lowest pLDDT structures often do not correspond to its most accurate predictions for peptides, highlighting critical limitations in confidence estimation for flexible systems [18].

Protocol for Functional Site Geometry Assessment

Objective: Validate the structural accuracy of functionally critical regions, particularly binding pockets and active sites.

Methodology:

- Functional Annotation: Identify ligand-binding residues or active sites from experimental complexes or conserved motifs.

- Pocket Geometry Analysis:

- Calculate binding pocket volumes and compare to experimental structures

- Measure residue side-chain rotamer accuracy

- Assess catalytic residue geometry

- Conservation Analysis: Evaluate correlation between prediction confidence and evolutionary conservation at functional sites.

- Ligand Docking Validation: Perform computational docking with known ligands/binders to assess practical utility [20].

This approach revealed that AlphaFold2 systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by 8.4% on average, with significant implications for drug discovery applications [20].

Implementing comprehensive benchmarking requires specialized resources and computational tools. The following table details essential components of the modern protein structure assessment pipeline.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Comprehensive Model Assessment

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | PSBench, SKEMPI 2.0, CASP targets | Provide diverse, labeled datasets for training and testing EMA methods |

| Quality Assessment | GATE, DProQA, ComplexQA, DeepUMQA-X | Estimate model accuracy at global, local, and interface levels |

| Specialized Metrics | Interface Contact Score, ipTM, iRMSD | Quantify specific aspects of model quality missed by global metrics |

| Visualization/Analysis | DeepSHAP, Explainable AI approaches | Interpret model predictions and identify influential features |

PSBench deserves particular emphasis as a comprehensive resource containing over one million structural models annotated with ten complementary quality scores, specifically designed to address the limitations of global metrics [21]. For researchers focusing on protein-protein interactions, the SKEMPI 2.0 database provides 317 protein-protein complexes and 8,338 mutations for validating interface predictions [17].

Implementation Workflow: From Prediction to Biological Insight

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for protein structure prediction and validation that addresses the limitations of global accuracy metrics:

Figure 1: Comprehensive Structure Assessment Workflow

The overreliance on global accuracy metrics presents a significant barrier to the practical application of protein structure prediction in biological research and drug development. While these metrics provide valuable summary statistics, they systematically obscure critical deficiencies in functionally important regions including protein-protein interfaces, flexible domains, and ligand-binding pockets.

Moving forward, the field must embrace multi-dimensional assessment frameworks that evaluate models based on their utility for specific research applications rather than abstract global scores. This requires widespread adoption of specialized benchmarks, interface-specific metrics, and application-focused validation protocols. Tools like PSBench [21] and methodologies like those used in independent AlphaFold3 validation [17] provide a foundation for this transition.

For researchers in drug discovery and structural biology, the implications are clear: global accuracy scores alone provide insufficient evidence for model reliability. Comprehensive assessment must include interface analysis for complex targets, binding site validation for drug discovery applications, and flexible region evaluation for signaling proteins. Only through this nuanced, application-aware approach can we fully leverage the revolutionary potential of modern protein structure prediction while recognizing its very real limitations.

Evaluation in Practice: Tools, Benchmarks, and Real-World Applications

The field of computational biology has been revolutionized by the advent of deep learning-based protein structure prediction models (PSPMs). These tools have transitioned from theoretical concepts to practical instruments that are reshaping structural biology, drug discovery, and protein engineering. Among the numerous models developed, three systems have emerged as leaders: AlphaFold, RoseTTAFold, and ESMFold. Each represents a distinct architectural philosophy and approach to solving the protein folding problem, with varying strengths, limitations, and application domains.

This technical analysis provides a comprehensive comparison of these three leading PSPMs, examining their underlying architectures, performance characteristics, and practical applications. Framed within the broader context of how to evaluate protein structure prediction models, this review equips researchers with the critical framework necessary to select appropriate tools for specific scientific inquiries and properly interpret their results.

Core Architectural Frameworks

AlphaFold: The Evoformer-Based Precision Instrument

AlphaFold2 introduced a novel "two-track" neural architecture called the Evoformer that jointly processes evolutionary and spatial relationships using multiple sequence alignment (MSA) and pairwise representations [22]. This architecture enables the model to draw global dependencies between input and output through its attention mechanism, particularly powerful for modeling long-range relationships in protein sequences beyond their sequential neighborhoods. The system is completed by a structure module based on equivariant transformer architecture with invariant point attention that generates atomic coordinates.

The recently released AlphaFold 3 represents a substantial architectural evolution, replacing the Evoformer with a simpler pairformer module and introducing a diffusion-based structure module that operates directly on raw atom coordinates [23]. This shift to diffusion enables AlphaFold 3 to predict complexes containing proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues within a unified deep-learning framework, dramatically expanding its biomolecular scope.

RoseTTAFold: The Three-Track Integrative Approach

RoseTTAFold extended AlphaFold's two-track architecture by adding a third track operating in 3D coordinate space using an SE(3)-transformer [22]. The key innovation is the simultaneous processing of MSA, pairwise, and coordinate information across these three tracks, with information flowing between them to consistently update representations at all levels. This integrative approach allows the network to reason about sequence, distance, and coordinate information in a coordinated manner.

Recent developments have seen RoseTTAFold adapted for sequence space diffusion with ProteinGenerator, enabling simultaneous generation of protein sequences and structures by iterative denoising guided by desired sequence and structural attributes [24]. This approach facilitates multistate and functional protein design, beginning from a noised sequence representation and generating sequence-structure pairs through denoising iterations.

ESMFold: The Language Model Pioneer

ESMFold takes a fundamentally different approach by leveraging a massive protein language model (PLM) called ESM-2 based on an encoder-only transformer architecture [22]. Unlike the other models, ESMFold eliminates dependence on MSAs by leveraging evolutionary information captured during pre-training on millions of protein sequences. It uses a modified Evoformer block from AlphaFold2 but operates without MSAs or known structure templates, significantly reducing computational overhead [25].

The model uses embeddings from protein language models derived from vast sequences, allowing it to excel particularly where limited structural data exists by capturing generalized sequence features and patterns through advanced language modeling techniques [26]. This shift from reliance on direct structural analogs to leveraging learned sequence contexts enables unique advantages for predicting novel or less-characterized protein structures.

Table 1: Core Architectural Comparison of Leading PSPMs

| Architectural Feature | AlphaFold | RoseTTAFold | ESMFold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | Evoformer (AF2) / Pairformer + Diffusion (AF3) | Three-track network (MSA, pair, 3D) | Encoder-only transformer |

| Evolutionary Information | MSA-dependent | MSA-dependent | Protein language model (ESM-2) |

| Structure Generation | Structure module / Diffusion | SE(3)-Transformer | Modified Evoformer block |

| Key Innovation | Two-track joint embedding | Three-track integration | MSA-free prediction |

| Biomolecular Scope | Proteins (AF2) → Complexes (AF3) | Proteins → Sequence-structure design | Single-chain proteins & multimers |

Performance Benchmarks and Comparative Analysis

Accuracy Metrics and CASP Performance

Independent benchmarking on CASP15 targets reveals distinct performance characteristics across the three models. AlphaFold2 achieves the highest mean GDT-TS score of 73.06, convincingly outperforming all other methods [22]. ESMFold attains the second-best performance in backbone positioning with a mean GDT-TS score of 61.62, interestingly outperforming MSA-based RoseTTAFold for more than 80% of cases despite being MSA-free.

For correct overall topology prediction (TM-score > 0.5), AlphaFold2 leads with nearly 80% success, followed by RoseTTAFold at just over 70%, indicating that MSA-based methods maintain an advantage in overall topology prediction compared to PLM-based approaches [22]. In side-chain positioning measured by GDC-SC metric, all methods show considerable room for improvement, with AlphaFold2's mean score falling short of 50, though it still outperformed other methods for more than 80% of cases [22].

Computational Efficiency and Resource Requirements

ESMFold demonstrates a significant speed advantage, achieving inference times of approximately 14 seconds for a 384-residue protein on a single NVIDIA V100 GPU, making it 6-60 times faster than AlphaFold2 depending on sequence length [25]. This efficiency comes from eliminating MSA search overhead, particularly beneficial for shorter sequences (<200 residues).

RoseTTAFold has inspired more efficient variants like LightRoseTTA, which achieves competitive performance with only 1.4M parameters (vs. 130M in RoseTTAFold) and can be trained in one week on a single NVIDIA 3090 GPU compared to 30 days on 8 NVIDIA V100 GPUs for the original RoseTTAFold [27]. This demonstrates the potential for lightweight models in resource-limited environments.

MSA Dependence and Orphan Protein Performance

A critical differentiator among these models is their dependence on multiple sequence alignments. Both AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold exhibit MSA dependence, with RoseTTAFold showing stronger dependence on deep MSAs for optimal performance [22]. This creates challenges for orphan proteins or rapidly evolving proteins with limited homologous sequences.

ESMFold fundamentally overcomes this limitation by leveraging evolutionary information captured in its protein language model during pre-training rather than requiring explicit MSA generation during inference [22]. Similarly, LightRoseTTA incorporates MSA dependency-reducing strategies that achieve superior performance on homology-insufficient datasets like Orphan, De novo, and Orphan25 [27].

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Standardized Benchmarks

| Performance Metric | AlphaFold | RoseTTAFold | ESMFold |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASP15 Mean GDT-TS | 73.06 | Not reported | 61.62 |

| TM-score > 0.5 (%) | ~80% | ~70% | Lower than MSA-based methods |

| Inference Speed (384 res) | ~85 seconds | Not reported | ~14 seconds |

| MSA Dependence | High | Higher | None |

| Stereochemical Quality | High (closer to experimental) | High (closer to experimental) | Lower (physical unrealistic regions) |

| Side-chain Accuracy (GDC-SC) | <50 (but best among methods) | Lower than PLM-based methods | Better than RoseTTAFold |

Specialized Applications and Limitations

Protein Complex Prediction

Predicting protein complexes presents unique challenges beyond monomer prediction. AlphaFold-Multimer (v2.3) and now AlphaFold 3 specifically address this domain, with AF3 demonstrating substantially improved accuracy for protein-protein interactions compared to previous versions [23]. Methods like DeepSCFold that build on these frameworks by incorporating sequence-derived structure complementarity show further improvements, achieving 11.6% and 10.3% higher TM-scores compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 respectively on CASP15 multimer targets [7].

ESMFold has been adapted for protein-peptide docking using polyglycine linkers between receptor and peptide sequences, achieving success rates comparable to traditional methods in specific cases, though generally lower than AlphaFold-Multimer or AlphaFold 3 [26]. The combination of result quality and computational efficiency underscores ESMFold's potential value as a component in consensus approaches for high-throughput peptide design.

Flexible Regions and Conformational Diversity

A significant limitation across all current PSPMs is accurately capturing conformational diversity and flexible regions. Comparative analysis of nuclear receptors reveals that while AlphaFold2 achieves high accuracy for stable conformations with proper stereochemistry, it shows limitations in capturing the full spectrum of biologically relevant states, particularly in flexible regions and ligand-binding pockets [20]. AlphaFold2 systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by 8.4% on average and captures only single conformational states in homodimeric receptors where experimental structures show functionally important asymmetry [20].

Similarly, in ion channel modeling, AlphaFold2 predicts most domains with high confidence (pLDDT >90), ESMFold with good confidence (70

De Novo Protein Design

RoseTTAFold has been successfully adapted for protein design through ProteinGenerator, which performs diffusion in sequence space rather than structure space [24]. This enables guidance using sequence-based features and explicit design of sequences populating multiple states. The system can design thermostable proteins with varying amino acid compositions, internal sequence repeats, and cage bioactive peptides. By averaging sequence logits between diffusion trajectories with distinct structural constraints, ProteinGenerator can design multistate parent-child protein triples where the same sequence folds to different supersecondary structures when intact versus split into child domains.

Experimental Workflows and Research Applications

Standard Protein Structure Prediction Workflow

The following workflow diagram illustrates a generalized experimental protocol for protein structure prediction using modern PSPMs, highlighting key decision points and methodological considerations:

Protein-Peptide Docking Workflow with ESMFold

For protein-peptide docking applications, ESMFold can be implemented with specialized sampling strategies as illustrated in the following workflow:

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Protein Structure Prediction Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction Servers | AlphaFold Server, ColabFold, ESMFold API | Provides accessible interfaces for structure prediction | Rapid model generation without local installation |

| Quality Assessment Tools | pLDDT, pTM, DockQ, MolProbity | Evaluates predicted model accuracy and stereochemical quality | Model validation and selection |

| Specialized Datasets | CASP targets, PDB, SAbDab, PoseBusters | Benchmarking and validation of prediction accuracy | Performance evaluation and method comparison |

| Sampling Enhancement Methods | Random masking, adaptive recycling, multiple seeds | Increases structural diversity and improves model quality | Challenging targets with poor initial predictions |

| Analysis & Visualization | PyMOL, ChimeraX, UCSF Chimera | Structure analysis, visualization, and comparison | Result interpretation and figure generation |

The comparative analysis of AlphaFold, RoseTTAFold, and ESMFold reveals a dynamic ecosystem of protein structure prediction tools with complementary strengths. AlphaFold remains the accuracy leader for most applications but with higher computational costs. RoseTTAFold offers strong performance with greater architectural flexibility for design applications, while ESMFold provides an optimal balance of speed and accuracy for high-throughput applications, particularly for targets with limited evolutionary information.

Future developments will likely focus on several key areas: improved prediction of conformational diversity and flexible regions, more accurate modeling of side-chain packing, reduced computational requirements through lightweight models, and expanded capabilities for modeling complex biomolecular interactions. The integration of these tools into structured workflows that leverage their complementary strengths will maximize their research impact across structural biology, drug discovery, and protein engineering.

As these technologies continue evolving, researchers must maintain critical assessment of model limitations, particularly for applications requiring high precision in flexible regions, binding pockets, and multi-state systems. The framework presented in this analysis provides the necessary foundation for selecting appropriate tools and interpreting their results within specific research contexts.

Recent advances in deep learning have propelled protein structure prediction (PSP) to new heights, with models like AlphaFold2 and ESMFold achieving near-atomic accuracy for well-folded proteins [29]. However, this remarkable progress has revealed a significant limitation: current benchmarks inadequately assess model performance in biologically challenging contexts, especially those involving intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) [30] [29]. This gap is particularly problematic given that IDRs are crucial for critical cellular processes—including signal transduction, transcriptional regulation, and molecular recognition—and frequently mediate transient, context-dependent interactions [29]. The lack of specialized benchmarking frameworks has limited the utility of PSP models in real-world applications such as drug discovery, disease variant interpretation, and protein interface design [30].

DisProtBench addresses this critical need by introducing a comprehensive, disorder-aware benchmark designed to evaluate structure and interaction prediction models under biologically realistic and functionally complex conditions [29]. By capturing diverse interaction modalities spanning disordered regions, multimeric complexes, and ligand-bound conformations, DisProtBench enables more meaningful assessments of model robustness, failure modes, and translational utility in biomedical research [29].

DisProtBench Architecture: A Three-Level Benchmarking Paradigm

DisProtBench adopts a novel three-level benchmarking paradigm that reflects the core stages of protein modeling workflows, from data preprocessing to predictive modeling and decision support [29]. This comprehensive architecture provides researchers with a unified framework for evaluating model utility under real-world biological constraints.

Data Level: Biologically Grounded Input Complexity

The Data Level formalizes biologically grounded input complexity through carefully curated datasets and unified representations [29]. DisProtBench's dataset spans multiple biologically complex scenarios involving IDRs:

- Disease-Associated Human Proteins: Thousands of human proteins with disordered regions linked to disease states [29].

- GPCR-Ligand Interactions: G protein-coupled receptor interactions relevant to drug discovery [29].

- Multimeric Complexes: Protein complexes with disorder-mediated interfaces [29].

This diverse dataset captures the structural heterogeneity critical for evaluating model robustness in realistic biological contexts, moving beyond the simplified single-chain proteins that dominated earlier benchmarks like CASP [29] [10].

Task Level: Model Functionalities and Evaluation Metrics

The Task Level defines model functionalities and implements task-specific evaluation metrics [29]. DisProtBench benchmarks eleven state-of-the-art PSP models across three primary disorder-sensitive tasks:

- Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Prediction: Evaluating model performance in predicting interaction interfaces involving disordered regions [29].

- Ligand-Binding Affinity Estimation: Assessing accuracy in estimating binding affinities for disordered regions involved in molecular recognition [29].

- Inter-Residue Contact Mapping: Measuring precision in identifying contacts within and between disordered regions [29].

The evaluation toolbox supports unified classification, regression, and interface metrics, enabling systematic assessment of functional reliability in domains such as drug discovery and protein engineering [29].

User Level: Interpretability and Accessibility

The User Level emphasizes interpretability, comparative diagnostics, and accessibility through the DisProtBench Portal [29]. This interactive web interface provides:

- Precomputed 3D Structure Visualizations: Allowing users to explore predicted structures without local model execution [29].

- Cross-Model Comparison Heatmaps: Enabling direct performance comparisons across different PSP models [29].

- Interactive Panels for Downstream Task Results: Facilitating investigation of structure-function relationships and error patterns [29].

This user-centered approach lowers the barrier to entry for non-experts and supports hypothesis generation and human-AI collaboration in structural biology research [29].

Figure 1: The three-level architecture of DisProtBench, spanning data complexity, task diversity, and user interpretability.

Experimental Framework and Evaluation Methodology

pLDDT-Based Stratification for Disordered Regions

A key innovation in DisProtBench's evaluation methodology is the formalization of pLDDT-based stratification throughout all assessments [29]. Predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) scores, which range from 0-100, serve as confidence metrics provided by models like AlphaFold2 [29]. DisProtBench systematically isolates model behavior in low-confidence regions (typically pLDDT < 70) that often correspond to intrinsically disordered regions or functionally ambiguous segments [29].

This stratification approach reveals crucial insights into model robustness, as low-confidence regions frequently correlate with functional prediction failures despite high global accuracy metrics [29]. By explicitly tracking performance across different confidence strata, researchers can better assess the reliability of predictions for biologically critical but structurally ambiguous regions.

Unified Evaluation Metrics

DisProtBench employs a comprehensive set of evaluation metrics tailored to different aspects of protein structure prediction. The table below summarizes the core metrics used across different task types:

Table 1: DisProtBench Evaluation Metrics Framework

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Application Context | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification Metrics | F1 Score, Precision, Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Binary disorder classification, interface prediction | Higher values indicate better predictive performance for categorical outcomes [29] |

| Regression Metrics | Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Global Distance Test-Total Score (GDT-TS) | Structural accuracy assessment | Lower RMSD and higher GDT-TS values indicate better structural agreement [29] [15] |

| Interface Metrics | Interface Contact Score (ICS/F1) | Multimeric complex assessment, PPI prediction | Measures accuracy of interface residue identification; higher values indicate better performance [15] |

Benchmarking Protocol

The experimental protocol for using DisProtBench follows a standardized workflow:

- Data Preparation: Input protein sequences are processed through the DisProtBench data pipeline, which incorporates annotations from DisProt and other biological databases [29].

- Model Inference: Multiple PSP models (twelve leading models in the initial benchmark) are run on the standardized dataset [29].

- Stratified Analysis: Predictions are stratified by confidence scores (pLDDT) to isolate performance in disordered versus structured regions [29].

- Task-Specific Evaluation: For each biological task (PPI, ligand binding, contact mapping), appropriate metrics are computed and compared across models [29].

- Visualization and Interpretation: Results are processed through the DisProtBench Portal for comparative analysis and error diagnosis [29].

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Implementing DisProtBench requires specific computational tools and resources. The table below details essential research reagents for conducting benchmark evaluations:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for DisProtBench Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | DisProt, GPCRdb, Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Provides curated protein sequences with annotated disordered regions and complex structures [29] | DisProt: https://disprot.org/GPCRdb: https://gpcrdb.org/PDB: https://www.rcsb.org/ [29] [10] |

| PSP Models | AlphaFold2, AlphaFold3, ESMFold, RoseTTAFold | Generates protein structure predictions from sequence data [29] | AlphaFold: https://github.com/google-deepmind/alphafoldESMFold: https://github.com/facebookresearch/esm [29] |

| Evaluation Framework | DisProtBench Toolbox | Computes standardized metrics across classification, regression, and interface tasks [29] | GitHub: https://github.com/Susan571/DisProtBench [29] |

| Visualization Portal | DisProtBench Portal | Provides precomputed 3D structures, comparative heatmaps, and error analysis [29] | Web interface accessible via project repository [29] |

DisProtBench Workflow: From Data to Interpretable Insights

The complete DisProtBench workflow integrates data curation, model evaluation, and result interpretation into a unified pipeline. The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end process for benchmarking protein structure prediction models:

Figure 2: End-to-end workflow for benchmarking protein structure prediction models using DisProtBench.

Implications for Protein Structure Prediction Research

DisProtBench represents a significant advancement in how the research community evaluates protein structure prediction models. By shifting focus from global accuracy metrics to function-aware evaluation in biologically challenging contexts, DisProtBench addresses critical limitations of existing benchmarks like CASP and CAID [29].

The benchmark's findings reveal substantial variability in model robustness under conditions of structural disorder, with low-confidence regions frequently correlated with functional prediction failures [29]. This insight is particularly valuable for applications in drug discovery, where accurate modeling of disordered regions and their interactions can significantly impact target identification and validation [29].

Furthermore, DisProtBench's integrative approach—spanning data complexity, task diversity, and user interpretability—establishes a new standard for comprehensive model evaluation in computational biology [29]. As the field continues to evolve, specialized benchmarks like DisProtBench will play an increasingly important role in guiding the development of more robust, biologically grounded prediction models that can handle the full complexity of real-world biomedical problems.

Utilizing PepPCBench for Evaluating Protein-Peptide Interaction Predictions

Accurate modeling of protein-peptide interactions is essential for understanding fundamental biological processes and designing peptide-based drugs [31]. However, predicting the complex structures of these interactions remains challenging, primarily due to the high conformational flexibility of peptides [32]. The ability to reliably assess the performance of computational methods in this domain is crucial for advancing the field. To support a fair and systematic evaluation of recent deep learning approaches, researchers have introduced PepPCBench, a specialized benchmarking framework tailored specifically to assess protein folding neural networks (PFNNs) in protein-peptide complex prediction [31]. This framework addresses a critical gap in structural bioinformatics by providing standardized evaluation metrics and datasets specifically designed for the challenging task of modeling protein-peptide interactions, which represent a distinct class of molecular recognition events compared to traditional protein-protein interactions.

The development of PepPCBench comes at a pivotal time when deep learning methods have revolutionized protein structure prediction. Tools like AlphaFold2 have demonstrated remarkable accuracy in predicting monomeric protein structures, but predicting complexes involving multiple chains remains significantly more challenging [7] [33]. This challenge is particularly pronounced for protein-peptide complexes, where the inherent flexibility of peptide chains and the transient nature of many such interactions complicate computational prediction. Within this context, PepPCBench serves as an essential tool for rigorously evaluating method performance, identifying limitations, and guiding future development in this specialized area of structural bioinformatics.

The PepPCBench Framework

Core Components and Design Principles

PepPCBench is structured around several core components designed to ensure comprehensive and unbiased evaluation of prediction methods. At the heart of this framework is PepPCSet, a carefully curated dataset of 261 experimentally resolved protein-peptide complexes with peptides ranging from 5 to 30 residues in length [31] [32]. This size range captures biologically relevant peptide interactions while presenting significant challenges due to increasing conformational flexibility with length. The framework is designed to be reproducible and extensible, enabling robust evaluation of PFNN-based methods and supporting their continued development for peptide-protein structure prediction [31].

The benchmarking methodology within PepPCBench employs comprehensive evaluation metrics that assess various aspects of prediction quality, including global structural accuracy, interface quality, and local geometry. This multi-faceted approach ensures that methods are evaluated across dimensions that are biologically and functionally relevant. The framework also systematically investigates factors that influence prediction accuracy, including peptide length, conformational flexibility, and training set similarity, providing insights into the specific conditions under which different methods succeed or struggle [31].

Benchmarking Dataset: PepPCSet

The PepPCSet dataset represents a significant advancement in resources for protein-peptide interaction studies. Curated from experimentally resolved structures, it provides a standardized testing ground that enables direct comparison between different computational methods. The inclusion of peptides of varying lengths (5-30 residues) allows researchers to assess how method performance scales with increasing peptide flexibility and complexity. Each entry in PepPCSet contains the experimentally determined structure along with associated metadata, enabling controlled investigations into factors affecting prediction accuracy.

Benchmarking Results and Performance Analysis

Comparative Performance of Deep Learning Methods

PepPCBench has been used to evaluate five full-atom protein folding neural networks: AlphaFold3 (AF3), AlphaFold-Multimer (AFM), Chai-1, HelixFold3 (HF3), and RoseTTAFold-All-Atom (RFAA) [31]. The benchmarking reveals meaningful performance differences among these methods, providing valuable insights for researchers selecting tools for their specific applications. While AF3 shows strong performance in structure prediction overall, the results demonstrate that no single method dominates across all evaluation metrics or peptide characteristics.

Table 1: Overview of Protein-Peptide Complex Prediction Methods Evaluated in PepPCBench

| Method | Developer | Key Characteristics | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold3 (AF3) | Google DeepMind | End-to-end deep learning; predicts structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and small molecules | Strong overall performance in structure prediction |

| AlphaFold-Multimer (AFM) | Google DeepMind | Extension of AlphaFold2 specifically designed for multimers | Improved accuracy for complexes compared to monomer-focused versions |

| RoseTTAFold-All-Atom (RFAA) | Baker Lab | End-to-end deep learning; handles proteins, nucleic acids, and small molecules | Competitive accuracy approaching AlphaFold methods |

| HelixFold3 (HF3) | Baidu Research | Combines MSA and protein language model representations | High performance with reduced computational requirements |

| Chai-1 | Unknown | Full-atom protein folding neural network | Evaluated in comprehensive benchmarking |

Key Factors Influencing Prediction Accuracy

The benchmarking analysis using PepPCBench has identified several critical factors that significantly impact prediction accuracy:

- Peptide Length: Performance generally decreases as peptide length increases, reflecting the greater conformational space that must be sampled for longer peptides.

- Conformational Flexibility: Methods struggle most with highly flexible peptides that adopt different conformations upon binding.

- Training Set Similarity: Performance is better for complexes that share similarities with structures in the method's training data, highlighting potential generalization challenges.

- Confidence Metrics: Interestingly, the confidence scores provided by these methods correlate poorly with experimental binding affinities, underscoring a significant limitation in current approaches and the need for improved scoring strategies [31].

Table 2: Factors Affecting Prediction Accuracy in Protein-Peptide Complex Modeling

| Factor | Impact on Prediction Accuracy | Recommendations for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Peptide Length | Inverse correlation; longer peptides (20-30 residues) show reduced accuracy | For longer peptides, consider ensemble docking approaches |

| Conformational Flexibility | High flexibility reduces accuracy due to conformational selection | Utilize enhanced sampling or multi-template approaches |

| Training Set Similarity | Higher similarity to training data improves performance | Assess model training data composition before application |

| Interface Composition | Polar interfaces often better predicted than hydrophobic ones | Analyze interface properties to gauge likely prediction quality |

| Confidence Metrics | Poor correlation with experimental binding affinities | Use confidence scores cautiously; not reliable for affinity prediction |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Benchmarking Workflow

The experimental protocol for utilizing PepPCBench follows a systematic workflow designed to ensure reproducible and comparable results across different prediction methods. The process begins with data preparation, where the PepPCSet dataset serves as the standardized input. Researchers then run structure predictions using the methods being evaluated, ensuring consistent computational resources and parameter settings to enable fair comparisons. The resulting structures are evaluated using the comprehensive metrics built into PepPCBench, which assess both global and local accuracy of the predictions.

A critical component of the protocol is the ablation analysis that systematically investigates factors affecting performance. This involves grouping results by peptide length, flexibility, and similarity to training data to identify specific strengths and limitations of each method. The final stage involves correlation analysis between confidence metrics and structural accuracy measures, providing insights into the reliability of method-specific confidence scores for prioritizing predictions in practical applications.

Implementation Workflow

The following workflow diagram illustrates the standardized benchmarking process implemented in PepPCBench:

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of protein-peptide interaction prediction and benchmarking requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table details essential "research reagents" for this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein-Peptide Interaction Studies

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Protein-Peptide Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| PepPCBench | Benchmarking Framework | Standardized evaluation of prediction methods | Core framework for assessing method performance on protein-peptide complexes |

| PepPCSet | Curated Dataset | 261 experimentally resolved protein-peptide complexes | Standardized test set for comparative evaluations |

| AlphaFold3 | Prediction Method | End-to-end structure prediction of biomolecular complexes | High-performing method for protein-peptide complex prediction |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Prediction Method | Specialized version for multimeric complexes | Optimized for complex structures including protein-peptide interactions |

| RoseTTAFold-All-Atom | Prediction Method | End-to-end prediction of protein complexes with small molecules | Alternative approach for protein-peptide complex modeling |

| AlphaSync | Database | Continuously updated predicted protein structures | Access to updated structures; addresses outdated sequence issues |

| UniProt | Database | Comprehensive protein sequence and functional information | Source of current sequences for accurate structure prediction |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | Experimentally determined protein structures | Source of templates and experimental reference structures |

Integration with Broader Protein Structure Prediction Context

Relationship to General Protein Complex Prediction

Protein-peptide interaction prediction represents a specialized subfield within the broader context of protein complex structure prediction. General protein complex prediction methods have seen significant advances, with tools like DeepSCFold demonstrating improvements of 11.6% and 10.3% in TM-score compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 respectively on CASP15 multimer targets [7]. However, protein-peptide complexes present unique challenges distinct from general protein-protein interactions, necessitating specialized benchmarking approaches like PepPCBench.

The field of protein structure prediction has evolved dramatically, with early methods relying on template-based modeling (TBM) gradually being supplemented or replaced by template-free modeling (TFM) approaches powered by deep learning [34]. Modern AI-based methods like AlphaFold represent a revolutionary advance, though they still face limitations when predicting structures of proteins that lack homologous counterparts in the training data [34]. Understanding this evolutionary context helps situate protein-peptide interaction prediction within the broader landscape of structural bioinformatics.

Methodological Limitations and Future Directions