A Practical Guide to Exploratory Data Analysis in Transcriptomics: From Raw Data to Biological Insights

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) for transcriptomics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

A Practical Guide to Exploratory Data Analysis in Transcriptomics: From Raw Data to Biological Insights

Abstract

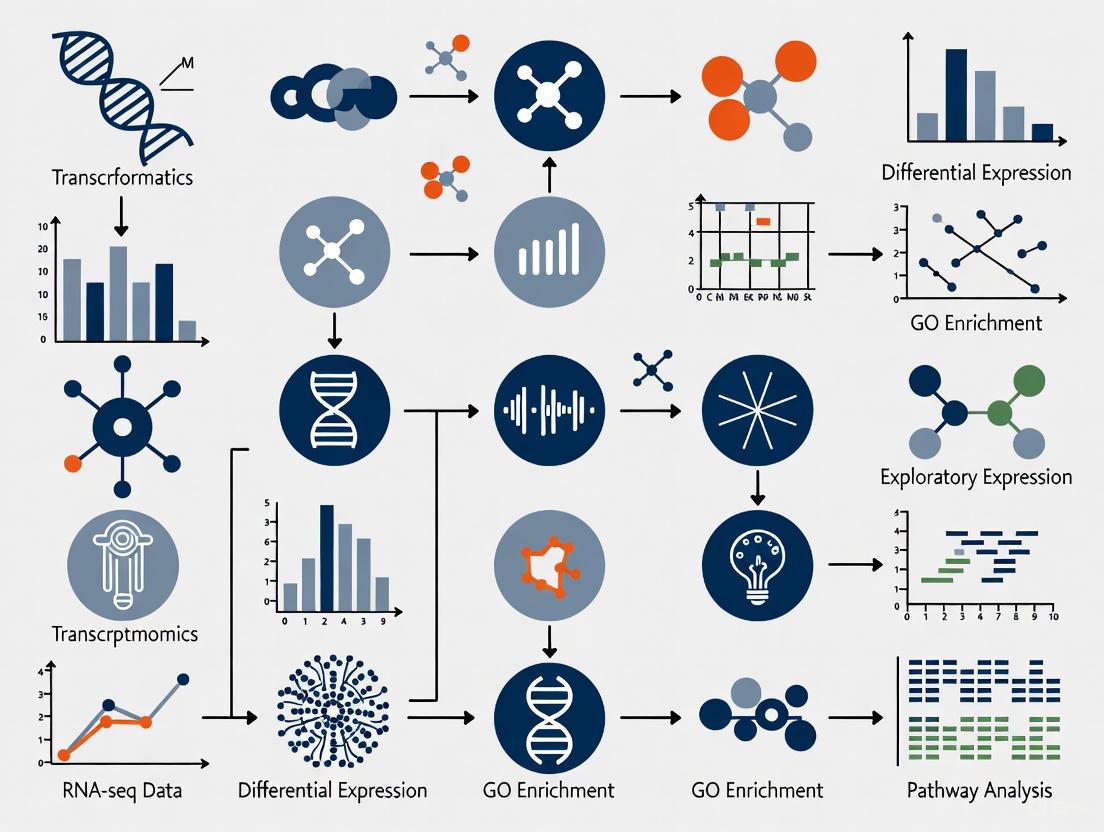

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) for transcriptomics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the entire workflow from foundational data inspection and quality control to advanced methodological applications for differential expression and biomarker discovery. The guide addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges in RNA-seq data and outlines rigorous validation frameworks to ensure robust, reproducible findings. By integrating best practices from computational and statistical approaches, this resource empowers scientists to transform raw sequencing data into reliable biological insights with direct implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Laying the Groundwork: Essential First Steps in Transcriptomics Data Inspection

Data Loading and Multi-Format Compatibility (FASTQ, FASTA, Count Matrices)

In transcriptomics research, the journey from raw sequencing output to biological insight relies on the proficient handling of three fundamental data formats: FASTQ, FASTA, and count matrices. These formats represent critical stages in the data analysis pipeline, each with distinct structures and purposes. The FASTQ format serves as the primary raw data output from next-generation sequencing platforms, containing both sequence reads and their corresponding quality scores. The FASTA format provides reference sequences—either genomic DNA, transcriptomes, or assembled contigs—essential for read alignment and annotation. Finally, count matrices represent the quantified gene expression levels across multiple samples, forming the foundation for downstream statistical analysis and visualization. Mastery of these formats and their interoperability is crucial for ensuring data integrity throughout the analytical workflow and enabling reproducible exploratory analysis in transcriptomics research.

The FASTQ Format: Raw Sequencing Data

Structure and Composition

The FASTQ format has become the standard for storing raw sequencing reads generated by next-generation sequencing platforms. Each sequence read in a FASTQ file consists of four lines, creating a complete record of both the sequence data and its associated quality information [1]:

- Line 1: Always begins with the '@' character followed by the sequence identifier and optional description information

- Line 2: The actual nucleotide sequence

- Line 3: Begins with a '+' character and may contain the same sequence identifier as line 1 (though often omitted in modern files)

- Line 4: Encodes quality scores for each base call in line 2, using ASCII characters to represent Phred quality scores

The quality scores in line 4 follow the Phred quality scoring system, where each character corresponds to a probability that the base was called incorrectly. The quality score is calculated as Q = -10 × logâ‚â‚€(P), where P represents the probability of an incorrect base call [1]. This logarithmic relationship means that a Phred quality score of 10 indicates a 90% base call accuracy (1 in 10 error rate), while a score of 20 indicates 99% accuracy (1 in 100 error rate), and 30 indicates 99.9% accuracy (1 in 1000 error rate) [1].

Quality Control and Preprocessing

Implementing rigorous quality control (QC) procedures for FASTQ files is an essential first step in any transcriptomics workflow. The FastQC tool provides a comprehensive suite of modules that assess multiple aspects of sequencing data quality, generating reports that help researchers identify potential issues arising from library preparation or sequencing processes [2]. Key QC metrics to evaluate include:

- Per-base sequence quality: Assesses the distribution of quality scores at each position across all reads, typically showing a gradual decrease in quality toward the read ends due to decreasing signal-to-noise ratio in sequencing-by-synthesis methods [2]

- Per-sequence quality scores: Examines the distribution of average quality scores per read, where high-quality data should show a single peak near the high-quality end of the scale [2]

- Adapter content: Measures the percentage of reads containing adapter sequences at each position, indicating incomplete adapter removal during library preparation [2]

- Sequence duplication levels: Shows the distribution of read sequence duplication, which in single-cell RNA-seq data may appear high due to PCR amplification and highly expressed genes, though FastQC is not UMI-aware [2]

For paired-end sequencing experiments, proper handling of the two complementary FASTQ files (containing forward and reverse reads) is critical. These files must remain synchronized throughout processing, as misalignment between files can compromise downstream analysis [3]. When extracting data from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA), tools like fastq-dump or fasterq-dump with the --split-files parameter properly separate paired-end reads into two distinct FASTQ files [3].

Table 1: Key FASTQ Quality Control Metrics and Their Interpretation

| QC Metric | Ideal Result | Potential Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Per-base sequence quality | Quality scores mostly in green area (>Q28), gradual decrease at ends | Sharp quality drops may indicate technical issues |

| Per-base N content | Near 0% across all positions | High N content suggests base-calling problems |

| Adapter content | Minimal to no adapter sequences | High adapter content requires trimming |

| GC content | Matches expected distribution for organism | Irregular distributions may indicate contamination |

The FASTA Format: Reference Sequences

Structure and Applications

The FASTA format provides a minimalistic yet powerful structure for storing biological sequence data, including nucleotides (DNA, RNA) and amino acids (proteins). Unlike FASTQ files, FASTA contains only sequence information without quality scores. Each record in a FASTA file consists of a header line beginning with the '>' character, followed by the sequence data on subsequent lines [4]. The header typically contains the sequence identifier and often includes additional descriptive information.

In transcriptomics, FASTA files serve multiple critical functions throughout the analytical pipeline. Reference genomes in FASTA format provide the coordinate system against which sequencing reads are aligned. Transcriptome sequences in FASTA format enable lightweight alignment tools like Kallisto and Salmon to perform rapid quantification without full genomic alignment [5]. Additionally, FASTA files can store assembled transcript sequences from long-read technologies like PacBio or Oxford Nanopore, which require specialized quality control tools such as SQANTI3 for curation and classification [6].

Reference-Based Alignment

The process of aligning FASTQ reads to FASTA reference sequences represents a critical juncture in transcriptomics analysis. Traditional splice-aware aligners like STAR perform base-to-base alignment of reads to the reference genome, accurately identifying exon-exon junctions—a crucial capability for eukaryotic transcriptomes where most genes undergo alternative splicing [4]. STAR employs a sophisticated algorithm that uses sequential maximum mappable seed search followed by seed clustering and stitching, making it particularly suited for RNA-seq alignment [4].

An alternative approach, utilized by tools like Kallisto and Salmon, employs pseudoalignment or lightweight alignment to a transcriptome FASTA file. These methods avoid the computationally intensive process of base-level alignment, instead determining the potential transcripts of origin for each read by examining k-mer compatibility [5]. This strategy offers significant speed advantages (typically more than 20 times faster) with comparable accuracy, making it particularly valuable for large-scale studies or rapid prototyping [1] [5]. The pseudoalignment workflow begins with building a de Bruijn graph index from the reference transcriptome, which is then used to rapidly quantify transcript abundances without generating base-level alignments [5].

Diagram 1: Reference-Based Analysis Workflow

Count Matrices: Gene Expression Quantification

Generation and Structure

The count matrix represents the fundamental bridge between raw sequencing data and biological interpretation in transcriptomics. This tabular data structure features genes or transcripts as rows and samples as columns, with each cell containing the estimated number of reads or molecules originating from that particular gene in that specific sample [2] [5]. In single-cell RNA-seq, the count matrix additionally incorporates cell barcodes (CB) and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish individual cells and account for amplification bias [2].

The process of generating a count matrix involves multiple computational steps depending on the experimental design and analytical approach. For bulk RNA-seq using alignment-based methods, tools like featureCounts (from the Subread package) quantify reads mapping to genomic features defined in annotation files (GTF format) [4]. For lightweight alignment tools like Kallisto and Salmon, the process begins with transcript-level abundance estimation, which must then be aggregated to gene-level counts using annotation mappings [5]. In single-cell RNA-seq, the process involves additional steps for cell barcode identification and correction, UMI deduplication, and empty droplet removal [2].

Table 2: Common Tools for Count Matrix Generation

| Tool | Method | Input | Output | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR [4] | Splice-aware alignment | FASTQ + Genome FASTA | BAM -> Counts | Standard RNA-seq, alternative splicing |

| featureCounts [4] | Read summarization | BAM + GTF | Count matrix | Gene-level quantification |

| Kallisto [5] | Pseudoalignment | FASTQ + Transcriptome FASTA | Abundance estimates | Rapid quantification, isoform analysis |

| Salmon [5] | Lightweight alignment | FASTQ + Transcriptome FASTA | Abundance estimates | Large datasets, differential expression |

| Space Ranger [7] | Spatial transcriptomics | FASTQ + Images | Feature-spot matrix | 10x Genomics spatial data |

Normalization Methods

Raw count matrices require normalization to account for technical variability before meaningful comparisons can be made between samples. Different normalization methods address specific sources of bias, and selecting an appropriate method depends on the analytical goals and downstream applications [1]:

- CPM (Counts Per Million): Simple scaling by total library size, accounting only for sequencing depth differences. Suitable for comparisons between replicates of the same sample group but not recommended for differential expression analysis [1]

- TPM (Transcripts Per Kilobase Million): Accounts for both sequencing depth and gene length, enabling comparisons within a sample or between samples of the same group [1]

- RPKM/FPKM: Similar to TPM but with different calculation order; TPM is now generally preferred for cross-sample comparisons [1]

- DESeq2's Median of Ratios: Uses a sample-specific size factor determined by the median ratio of gene counts relative to geometric mean per gene, accounting for both sequencing depth and RNA composition [1]

- EdgeR's TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values): Applies a weighted trimmed mean of the log expression ratios between samples to account for sequencing depth and RNA composition [1]

Normalization is particularly crucial when dealing with data containing strong composition effects, such as when a few highly differentially expressed genes dominate the total count pool, which can skew results if not properly addressed [1].

Integrated Workflows and Best Practices

Multi-Format Interoperability

Successful transcriptomics analysis requires seamless transitions between the three core data formats throughout the analytical workflow. The journey begins with quality assessment of FASTQ files using FastQC, followed by adapter trimming and quality filtering with tools like Cutadapt [4]. Processed reads are then aligned to reference sequences in FASTA format using either full aligners like STAR or lightweight tools like Salmon, depending on the research question and computational resources [4] [5]. The resulting alignments are processed into count matrices, which serve as input for downstream statistical analysis in tools like DESeq2 or EdgeR [1].

Each format transition point represents a potential source of error that must be carefully managed. When moving from FASTQ to alignment, ensuring compatibility between sequencing platform and reference genome build is essential. The transition from alignments to count matrices requires accurate feature annotation and strand-specific counting when appropriate. Documenting all parameters and software versions at each step is critical for reproducibility, particularly when processing data through multiple format transformations [5].

Diagram 2: Complete Transcriptomics Data Processing Pipeline

Quality Assurance Across Formats

Maintaining data integrity requires quality checks at each format transition. For FASTQ data, this includes verifying expected sequence lengths, base quality distributions, and adapter contamination levels [2]. For FASTA reference files, ensuring compatibility with annotation files and checking for contamination or misassembly is important. For count matrices, quality assessment includes examining mapping rates, ribosomal RNA content, and sample-level clustering patterns [1].

Sample-level QC performed on normalized count data helps identify potential outliers and confirms that experimental groups cluster as expected. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and correlation heatmaps are particularly valuable for visualizing overall similarity between samples and verifying that biological replicates cluster together while experimental conditions separate [1]. These QC steps help ensure that the major sources of variation in the dataset reflect the experimental design rather than technical artifacts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Tools for Transcriptomics Data Processing

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Format Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastQC [2], MultiQC | Assess sequencing data quality | FASTQ |

| Read Processing | Cutadapt [4], Trimmomatic | Adapter trimming, quality filtering | FASTQ |

| Genome Alignment | STAR [4], HISAT2 | Splice-aware read alignment | FASTQ → BAM/SAM |

| Lightweight Alignment | Kallisto [5], Salmon [5] | Rapid transcript quantification | FASTQ → Abundance estimates |

| Read Quantification | featureCounts [4], HTSeq | Generate count matrices | BAM/SAM → Count matrix |

| Normalization | DESeq2 [1], EdgeR [1] | Count normalization for DE analysis | Count matrix → Normalized counts |

| Visualization | bigPint [8], MultiQC | Interactive plots, QC reports | Count matrix, FASTQ stats |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Space Ranger [7] | Process spatial gene expression data | FASTQ + Images → Feature-spot matrix |

| Long-Read QC | SQANTI3 [6] | Quality control for long-read transcriptomes | FASTA/Q → Curated isoforms |

| Bucharidine | Bucharidine | Bucharidine, a natural quinoline alkaloid. Explore its research applications in oncology and virology. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| TSCHIMGANIDINE | Tschimganidine|Potent AMPK Activator|For Research Use | Tschimganidine is a natural terpenoid that reduces lipid accumulation and improves glucose homeostasis via AMPK activation. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Trends

Spatial Transcriptomics

Spatial transcriptomic technologies represent a significant advancement that preserves the spatial context of gene expression measurements, enabling researchers to investigate the architectural organization of tissues and cell-cell interactions [7]. These methods employ various approaches including in situ sequencing, in situ hybridization, or spatial barcoding to recover original spatial coordinates along with transcriptomic information [7]. The data generated from these technologies requires specialized processing pipelines like Space Ranger, which handles alignment, tissue detection, barcode/UMI counting, and feature-spot matrix generation [7].

The integration of spatial coordinates with gene expression matrices creates unique computational challenges and opportunities for visualization. Analysis methods for spatial transcriptomics include identification of spatially variable genes using tools like SpatialDE, which applies Gaussian process regression to decompose expression variability into spatial and non-spatial components [7]. Clustering algorithms must be adapted to incorporate spatial neighborhood information, moving beyond traditional methods that consider only expression similarity [7].

Long-Read Transcriptomics

Long-read sequencing technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore have revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling full-length transcript sequencing, which provides complete information about splice variants and isoform diversity without the need for assembly [6]. However, these technologies introduce new data processing challenges, including higher error rates and the need for specialized quality control tools.

SQANTI3 represents a comprehensive solution for quality control and filtering of long-read transcriptomes, classifying transcripts based on comparison to reference annotations and providing extensive quality metrics [6]. The tool categorizes transcripts into structural classes including Full Splice Match (FSM), Incomplete Splice Match (ISM), Novel in Catalog (NIC), Novel Not in Catalog (NNC), and various fusion and antisense categories [6]. This classification enables researchers to distinguish between genuine biological novelty and technical artifacts, which is particularly important given the higher error rates associated with long-read technologies.

Visualization and Interpretation

Effective visualization of transcriptomic data is essential for exploratory analysis and hypothesis generation. Traditional visualization methods include heatmaps for gene expression patterns, volcano plots for differential expression results, and PCA plots for sample-level quality assessment [9]. More advanced visualization approaches include parallel coordinate plots, which display each gene as a line connecting its expression values across samples, enabling researchers to quickly assess relationships between variables and identify patterns that might be obscured in summarized views [8].

Interactive visualization tools like bigPint facilitate the detection of normalization issues, differential expression designation problems, and common analysis errors by allowing researchers to interact directly with their data [8]. These tools enable researchers to hover over and select genes of interest across multiple linked visualizations, creating a dynamic exploratory environment that supports biological discovery. When creating visualizations, careful attention to color selection is essential, including consideration of color blindness accessibility and appropriate mapping of color scales to data types (categorical vs. continuous) [10].

In transcriptomics research, the initial inspection of data is a critical first step that determines the reliability of all subsequent biological interpretations. This process involves summarizing the main characteristics of a dataset—its structure, dimensions, and basic statistics—to assess quality, identify potential issues, and form preliminary hypotheses. Within a broader Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) framework, this initial inspection provides a foundational understanding upon which further, more complex analyses are built, ensuring that models and conclusions are derived from robust, well-characterized data [11]. For researchers and drug development professionals, rigorous initial inspection is indispensable for transforming raw sequencing output into biologically meaningful insights, guiding decisions on downstream analytical pathways, and ultimately, validating potential biomarkers [12].

Core Concepts of Initial Data Inspection

Initial data inspection serves as the first diagnostic check on a newly loaded dataset. Its primary objectives are to verify that the data has been loaded correctly, understand its fundamental composition, and identify any obvious data integrity issues before investing time in more sophisticated analyses.

- Objective vs. Subjective Data: The data collected in transcriptomics is predominantly objective and quantitative. Objective data is fact-based, measurable, and observable, meaning that if two scientists make the same measurement with the same tool, they would obtain the same answer. This is distinct from subjective data, which is based on opinion, point of view, or emotional judgment [13].

- Key Inspection Metrics: The initial inspection typically focuses on several key metrics:

- Structure: This refers to the format and organization of the data, such as a matrix where rows often represent genes (features) and columns represent samples (observations).

- Dimensions: The size of the dataset, typically expressed as the number of rows and columns (e.g.,

(genes, samples)). - Basic Statistics: Summary statistics that describe the central tendency and dispersion of the data, such as mean, median, and standard deviation [13] [11].

Practical Implementation with Python and Pandas

The following section provides a practical methodology for performing an initial data inspection using the Python Pandas library, which is a standard tool in bioinformatics.

Data Loading and Initial Inspection Commands

After loading transcriptomics data (e.g., from a CSV file), a series of commands provide an immediate overview of the dataset's health and structure.

Code Explanation:

data.shape: This command returns a tuple representing the dimensionality of the DataFrame, crucial for understanding the dataset's scale [14].data.head()anddata.tail(): These functions display the first and last five rows of the DataFrame, respectively, allowing for a visual check of the data's structure and contents [14].data.info(): This provides a concise summary of the DataFrame, including the number of non-null entries in each column and the data types (dtypes), which is vital for identifying columns with missing values or incorrect data types [11].data.describe(): This function generates descriptive statistics that summarize the central tendency, dispersion, and shape of a dataset's distribution, excludingNaNvalues. It is invaluable for quickly spotting anomalies in the data [11].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key outputs of the initial data inspection workflow.

Key Metrics and Quantitative Standards

The initial inspection yields quantitative metrics that must be evaluated against field-specific standards. The table below summarizes these key metrics and their implications in a transcriptomics context.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Initial Data Inspection in Transcriptomics

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Description | Importance in Transcriptomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | Number of Genes (Rows) | Total features measured. | Verifies expected gene coverage from the sequencing assay. |

| Number of Samples (Columns) | Total observations or libraries. | Confirms all experimental replicates and conditions are present. | |

| Data Types | int64, float64 |

Numeric data types for expression values. | Ensures expression counts/levels are in a computable format. |

object |

Typically represents gene identifiers or sample names. | Confirms non-numeric data is properly classified. | |

| Completeness | Non-Null Counts | Number of non-missing values per column. | Identifies genes with low expression or samples with poor sequencing depth that may need filtering [12]. |

| Basic Statistics | Mean Expression | Average expression value per gene or sample. | Helps identify overall expression levels and potential batch effects. |

| Standard Deviation | Dispersion of expression values. | High variance may indicate interesting biological regulation; low variance may suggest uninformative genes. | |

| Min/Max Values | Range of expression values. | Flags potential outliers or technical artifacts in the data. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The wet-lab phase of generating transcriptomics data relies on specific reagents and protocols, which directly impact the quality of the data subjected to initial inspection.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Transcriptomics Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Context in Spatial Transcriptomics |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Barcoding Beads | Oligonucleotide-labeled beads that capture mRNA and assign spatial coordinates. | Core of technologies like the original Spatial Transcriptomics platform; enables transcriptome-wide profiling with positional information [15]. |

| Fluorescently Labeled Probes | Nucleic acid probes that bind target RNA sequences for visualization. | Essential for in situ hybridization-based methods (e.g., MERFISH, seqFISH) to detect and localize specific RNAs [15]. |

| Cryostat | Instrument used to cut thin tissue sections (cryosections) at low temperatures. | Critical for preparing tissue samples for most spatial transcriptomics methods, preserving RNA integrity [15]. |

| Library Preparation Kit | A suite of enzymes and buffers for converting RNA into a sequencer-compatible library. | Standardized kits are used to prepare sequencing libraries from captured mRNA, whether from dissociated cells or spatially barcoded spots. |

| Hept-5-yn-1-amine | Hept-5-yn-1-amine | |

| Cyclopropanethiol | Cyclopropanethiol|CAS 6863-32-7|RUO |

Experimental Protocols for Data Generation

The quality of data for inspection is determined by the preceding experimental workflow. Below is a generalized protocol for a spatial barcoding-based approach, a common modern method.

Protocol: Gene Expression Profiling via Spatial Barcoding

Tissue Preparation:

- Embed fresh-frozen tissue in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound.

- Section tissue to a defined thickness (e.g., 10 µm) using a cryostat and mount onto specific spatially barcoded slides [15].

Fixation and Staining:

- Fix tissue sections with methanol or formaldehyde to preserve morphology and immobilize RNA.

- Stain with histological dyes (e.g., H&E) for morphological assessment and image acquisition.

Permeabilization and cDNA Synthesis:

- Permeabilize tissue with an enzymatic solution (e.g., containing proteases) to allow mRNAs to diffuse from the tissue.

- The released mRNAs are captured by the spatially barcoded oligonucleotides on the slide surface.

- Perform on-slide reverse transcription to synthesize cDNA strands complementary to the captured mRNAs, incorporating the spatial barcode [15].

Library Construction and Sequencing:

- Harvest the cDNA and construct a sequencing library using a standard kit (e.g., incorporating Illumina adapters and sample indices).

- The final library is sequenced on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq).

Data Generation for Inspection:

- Output: The primary output is a digital gene expression matrix. In this matrix, rows represent genes, columns represent spatially barcoded spots (each corresponding to a location on the tissue), and values represent raw or normalized gene expression counts (e.g., UMI counts) [15].

- Associated Metadata: A vital companion file is the spatial coordinates file, which maps each spatial barcode (column in the matrix) to its x,y coordinates on the tissue image. This matrix and its metadata are the direct inputs for the initial data inspection process.

From Inspection to Analysis: Integrating Findings

The findings from the initial inspection directly inform subsequent data cleaning and preprocessing steps in the transcriptomics EDA pipeline. Inconsistent data types identified via info() must be corrected. Missing values, flagged by info() and describe(), may require imputation or filtering [12] [11]. The summary statistics from describe() can help establish thresholds for filtering out lowly expressed genes, a critical step to reduce noise before differential expression analysis [12]. Ultimately, a well-executed initial inspection ensures that the data proceeding to advanced stages like normalization, batch correction, and biomarker discovery is of the highest possible quality, thereby safeguarding the integrity of the scientific conclusions.

Quality control (QC) of raw sequencing data is a critical first step in transcriptomics research that directly impacts the reliability and interpretability of all subsequent analyses. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of best practices for assessing raw read quality and adapter contamination within a comprehensive exploratory data analysis framework. We detail specific QC metrics, methodologies, and computational tools that enable researchers to identify technical artifacts, validate data quality, and ensure the production of biologically meaningful results. By establishing rigorous QC protocols, scientists can mitigate confounding technical variability and enhance the discovery potential of transcriptomics studies in both basic research and drug development applications.

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), the initial assessment of raw read quality forms the foundation for generating accurate gene expression measurements [16]. Sequencing technologies introduce various technical artifacts including base-calling errors, adapter contamination, and sequence-specific biases that can compromise downstream analyses if not properly addressed [17]. Quality control measures serve to identify these issues early in the analytical pipeline, preventing the propagation of technical errors into biological interpretations [18]. Within the broader context of transcriptomics research, rigorous QC is particularly crucial for clinical applications where accurate biomarker identification and differential expression analysis inform diagnostic and therapeutic decisions [18].

The raw data generated from RNA-seq experiments is typically stored in FASTQ format, which contains both nucleotide sequences and corresponding per-base quality scores [17]. Before proceeding to alignment and quantification, this raw data must undergo comprehensive evaluation to assess sequencing performance, detect contaminants, and determine appropriate preprocessing steps. Systematic QC practices enable researchers to distinguish technical artifacts from biological signals, thereby ensuring that conclusions reflect true biological phenomena rather than methodological inconsistencies [16].

Key Metrics for Raw Read Quality Assessment

Primary Sequence Quality Metrics

Table 1: Essential Quality Metrics for Raw RNA-seq Data

| Metric Category | Specific Measurement | Interpretation Guidelines | Potential Issues Indicated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per-base Sequence Quality | Phred Quality Scores (Q-score) | Q≥30: High quality; Q20: 1% error rate; Q10: 10% error rate | Degrading quality over sequencing cycles |

| Nucleotide Distribution | Proportion of A, T, C, G at each position | Expected: Stable distribution across cycles | Overrepresented sequences, random hexamer priming bias |

| GC Content | Percentage of G and C nucleotides | Should match organism/sample expectations (~40-60% for mammalian mRNA) | Contamination, PCR bias [16] |

| Sequence Duplication | Proportion of identical reads | Moderate levels expected; high levels indicate PCR over-amplification | Low library complexity, insufficient sequencing depth |

| Overrepresented Sequences | Frequency of specific k-mers | Should not be dominated by single sequences | Adapter contamination, dominant RNA species [16] |

The Phred quality score (Q-score) represents the fundamental metric for assessing base-calling accuracy, with Q30 indicating a 1 in 1,000 error probability [16]. Per-base quality analysis typically reveals decreasing scores toward read ends due to sequencing chemistry limitations. Nucleotide distribution should remain relatively uniform across sequencing cycles, while significant deviations may indicate random hexamer priming bias or the presence of overrepresented sequences [16]. GC content evaluation provides insights into potential contamination when values deviate more than 10% from expectations based on the target organism's genomic composition [16].

Adapter Contamination Assessment

Adapter contamination occurs when sequencing extends beyond the DNA insert into the adapter sequences ligated during library preparation [19]. In Illumina platforms, this primarily affects the 3' ends of reads when fragment sizes are shorter than the read length [19]. The incidence of adapter contamination varies significantly by protocol, with standard RNA-seq experiencing approximately 0.2-2% affected reads, while small RNA sequencing exhibits nearly universal adapter contamination due to shorter insert sizes [19]. Left unaddressed, adapter sequences can prevent read alignment and increase the proportion of unmappable sequences, ultimately reducing usable data and compromising expression quantification accuracy [19].

Computational Tools and Methodologies

Quality Assessment Tools

Table 2: Bioinformatics Tools for RNA-seq Quality Control

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Input Format | Key Outputs | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastQC [17] | Comprehensive quality check | FASTQ | HTML report with quality metrics | Initial assessment of raw reads |

| HTQC [17] | Quality control and trimming | FASTQ | Quality metrics, trimmed reads | Integrated QC and preprocessing |

| FASTX-Toolkit [17] | Processing and QC | FASTQ | Processed sequences, statistics | Adapter removal, quality filtering |

| FLEXBAR [17] | Adapter trimming | FASTQ | Cleaned reads, trimming reports | Flexible adapter removal |

| RNA-SeQC [17] | Alignment-based QC | BAM | Mapping statistics, coverage biases | Post-alignment quality assessment |

| Qualimap 2 [17] | RNA-seq specific QC | BAM | Alignment quality, 5'-3' bias | Comprehensive post-alignment evaluation |

| RSeQC [17] | Sequence data QC | BAM | Read distribution, coverage uniformity | In-depth QC after mapping |

FastQC provides a broad overview of data quality through multiple modules that assess base quality, GC content, adapter contamination, and other key metrics [17]. The tool generates an intuitive HTML report that highlights potential issues requiring remediation. For specialized RNA-seq QC, tools like RNA-SeQC and RSeQC operate on alignment files (BAM format) to evaluate mapping quality, coverage uniformity, and technical biases such as 5'-3' coverage bias [17]. Qualimap 2 extends these capabilities with multi-sample comparison features, enabling batch effect detection and cross-sample quality assessment [17].

Adapter Trimming Approaches

Adapter trimming strategies fall into two primary categories: adapter trimming to remove known adapter sequences and quality trimming to eliminate low-quality base calls [17]. The FASTX-Toolkit and FLEXBAR implementations provide flexible parameterization for adapter sequence specification, quality thresholds, and minimum read length requirements [17]. The necessity of adapter trimming depends on the specific RNA-seq protocol and insert size distribution. While essential for small RNA sequencing, standard transcriptome sequencing with appropriate size selection may contain minimal adapter contamination (0.2-2%), potentially allowing researchers to skip this step for time efficiency [19].

Figure 1: Workflow for Comprehensive Raw Read QC and Adapter Contamination Assessment

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Step-by-Step Quality Assessment Protocol

Initial Quality Metric Extraction: Process raw FASTQ files through FastQC to generate baseline quality metrics. Examine per-base sequence quality to identify regions requiring trimming and assess nucleotide composition for uniform distribution.

Adapter Contamination Analysis: Within FastQC reports, review the "Overrepresented Sequences" module to identify adapter sequences. Determine the percentage of affected reads and compare against expected thresholds (typically >1% requires intervention) [19].

Quality Trimming Execution: Using FASTX-Toolkit or FLEXBAR, trim low-quality bases from read ends using a quality threshold of Q20 and minimum length parameter of 25-35 bases depending on read length [17].

Adapter Removal Implementation: For datasets with significant adapter contamination, perform adapter trimming with FLEXBAR using platform-specific adapter sequences and a minimum overlap parameter of 3-5 bases.

Post-processing Quality Verification: Re-run FastQC on trimmed FASTQ files to confirm improvement in quality metrics and reduction/elimination of adapter sequences.

Alignment and RNA-specific QC: Map reads to the reference transcriptome or genome using appropriate aligners (STAR, HISAT2), then process BAM files through RNA-SeQC or Qualimap 2 to evaluate RNA-specific metrics including 5'-3' bias, ribosomal RNA content, and coverage uniformity [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function in QC Process |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control Software | FastQC [17] | Comprehensive quality assessment of raw sequences |

| Trimming Tools | FASTX-Toolkit [17] | Adapter removal and quality-based trimming |

| Trimming Tools | FLEXBAR [17] | Flexible adapter detection and removal |

| Alignment-based QC | RNA-SeQC [17] | Post-alignment quality metrics for RNA-seq |

| Alignment-based QC | RSeQC [17] | Evaluation of read distribution and coverage |

| Alignment-based QC | Qualimap 2 [17] | RNA-seq specific quality evaluation |

| Workflow Integration | Snakemake [20] | Automated workflow management for reproducible QC |

| Visualization | PIVOT [21] | Interactive exploration of QC metrics and data quality |

| Azido-PEG4-TFP ester | Azido-PEG4-TFP ester, CAS:1807505-33-4, MF:C17H21F4N3O6, MW:439.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4,5-Acridinediamine | 4,5-Acridinediamine, CAS:3407-96-3, MF:C13H11N3, MW:209.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integration with Exploratory Data Analysis

Quality control metrics should be integrated into a broader exploratory data analysis framework to identify potential confounding factors before conducting formal statistical testing. Tools like PIVOT provide interactive environments for visualizing QC metrics alongside sample metadata, enabling researchers to detect batch effects, sample outliers, and technical artifacts that might influence downstream interpretations [21]. Principal component analysis (PCA) applied to quality metrics can reveal systematic patterns correlated with experimental conditions, sequencing batches, or processing dates.

Within comprehensive transcriptomics workflows, raw read QC represents the initial phase of a multi-stage quality assessment protocol that continues through alignment quantification, and normalization [20]. The establishment of QC checkpoints at each analytical stage ensures data integrity throughout the research pipeline. Modern approaches increasingly incorporate transcript quantification tools like Salmon and kallisto that generate their own QC metrics, providing additional validation of data quality [20].

Figure 2: Integration of Raw Read QC within Comprehensive Transcriptomics Workflow

Comprehensive assessment of raw read quality and adapter contamination establishes the essential foundation for robust transcriptomics research. By implementing systematic QC protocols utilizing established tools and metrics, researchers can identify technical artifacts, prevent erroneous conclusions, and maximize the biological insights gained from sequencing experiments. The integration of these QC practices within broader exploratory data analysis frameworks ensures that technical variability is properly accounted for, ultimately enhancing the validity and reproducibility of transcriptomics findings in both basic research and drug development applications. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, maintaining rigorous quality assessment standards will remain paramount for extracting meaningful biological signals from increasingly complex datasets.

Detecting and Quantifying Missing Data and Technical Artifacts

In transcriptomics research, the accuracy of biological interpretation is fundamentally dependent on data quality. Missing data and technical artifacts can obscure true biological signals, leading to flawed conclusions. Within a framework of best practices for exploratory data analysis, the proactive detection and quantification of these issues is a critical first step. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with advanced methodologies to identify, assess, and mitigate common data quality pitfalls in both bulk and spatial transcriptomics.

Core Concepts and Impact on Analysis

Technical artifacts in transcriptomics are non-biological patterns introduced during sample preparation, sequencing, or data processing. Common types include:

- Batch Effects: Systematic technical variations between experimental batches that can confound true biological differences [22].

- Spatial Artifacts: In spatial transcriptomics, these include border effects (altered gene reads at the border of the capture area) and tissue edge effects (modified reads at the tissue edge), which do not reflect underlying biology [23].

- Sequence-Specific Biases: Includes adapter contamination, PCR artifacts, sequencing errors, and GC content bias, which impact read mappability and quantification accuracy [24].

Missing data often arises from low sequencing depth, inefficient mRNA capture, or probe/probe set limitations, particularly in spatial technologies that profile fewer genes compared to scRNA-seq [25]. These issues can skew differential expression analysis, cluster formation, and pathway analysis if not properly diagnosed and addressed during initial exploratory data analysis.

Methodologies for Detection and Quantification

Statistical Detection of Spatial Artifacts

The Border, Location, and edge Artifact DEtection (BLADE) framework provides a robust statistical method for identifying artifacts in spatial transcriptomics data [23]. The methodology involves the following steps:

- Identify Edge and Interior Spots: Calculate the shortest taxicab distance from each spot to the nearest spot without tissue. BLADE defines edge spots as those with a distance of 1 and interior spots with a distance ≥2 from the tissue edge [23].

- Perform Statistical Testing: Conduct a two-sample unpaired t-test comparing the distribution of total gene read counts between the identified edge spots and interior spots.

- Interpret Results: A significant p-value (after multiple comparison correction, e.g., Bonferroni) below 0.05 indicates the presence of a tissue edge effect artifact. A similar methodology, comparing spots near the capture area border to non-border spots, is used to detect border effects [23].

Table 1: BLADE Detection Workflow Outputs and Interpretation

| Artifact Type | Detection Method | Key Output | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Edge Effect | t-test (edge vs. interior spots) | Corrected P-value | P < 0.05 indicates artifact presence |

| Border Effect | t-test (border vs. non-border spots) | Corrected P-value | P < 0.05 indicates artifact presence |

| Location Batch Effect | Inspection of same location across slides in a batch | Zone of decreased sequencing depth | Consistent low-read zone across a batch |

Uncertainty Quantification for Data Imputation

In spatial transcriptomics, imputing missing genes is common, but assessing the reliability of imputed values is crucial. The Variational Inference for Spatial Transcriptomic Analysis (VISTA) approach quantifies uncertainty directly during imputation [25].

- Model Training: VISTA jointly models scRNA-seq data (as a Zero-inflated Negative Binomial distribution) and spatial data (as a Negative Binomial distribution) using a geometric deep learning framework incorporating Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Variational Inference [25].

- Uncertainty Estimation: The model provides two uncertainty measures:

- VISTAgene: Ranks genes by imputation certainty.

- VISTAcell: Ranks cells by imputation certainty.

- Validation: The reliability of these measures is validated by observing an increase in the Spearman correlation coefficient when genes or cells with uncertainty rankings in the bottom 50% are filtered out [25].

Quality Control in Bulk RNA-seq

A comprehensive quality control (QC) pipeline for bulk RNA-seq involves checkpoints at multiple stages [24]:

- Raw Read QC: Analyze sequence quality, GC content, adapter presence, overrepresented k-mers, and duplicated reads using tools like FastQC or NGSQC. Outliers with over 30% disagreement in metrics should be scrutinized or discarded. Tools like Trimmomatic or the FASTX-Toolkit can remove low-quality bases and adaptors [24].

- Alignment QC: Assess the percentage of mapped reads (70-90% expected for human genome), uniformity of exon coverage, and strand specificity. Tools like RSeQC, Qualimap, or Picard are recommended. Accumulation of reads at the 3' end in poly(A)-selected samples indicates low RNA quality [24].

- Quantification QC: Check for GC content and gene length biases, which may require normalization correction. For well-annotated genomes, analyze the biotype composition of the sample as an indicator of RNA purification quality [24].

Diagram 1: RNA-seq QC workflow with key checkpoints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomics

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Visium Spatial Slide | Contains ~5000 barcoded spots for mRNA capture; spatial barcode, UMI, and oligo-dT domains enable transcript localization and counting. | 10X Visium Spatial Transcriptomics [26] |

| Spatial Barcoded Probes | Target-specific or poly(dT) probes that hybridize to mRNA and incorporate spatial barcodes during cDNA synthesis. | Visium V2 FFPE Workflow [26] |

| CytAssist Instrument | Transfers gene-specific probes from standard slides to Visium slide, simplifying workflow and improving handling. | 10X Visium (FFPE samples) [26] |

| Primary Probes (smFISH) | Hybridize to target RNA transcripts; contain gene-specific barcodes or "hangout tails" for signal amplification/decoding. | Xenium, Merscope, CosMx Platforms [26] |

| Fluorescently Labeled Secondary Probes | Bind to primary probes for signal readout via cyclic hybridization and imaging. | Xenium, Merscope, CosMx Platforms [26] |

| Poly(dT) Primers | Enrich for mRNA by binding to poly-A tails during reverse transcription. | Standard RNA-seq (poly-A selection) [24] |

| Ribo-depletion Kits | Remove abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA), crucial for samples with low mRNA integrity or bacterial RNA-seq. | Standard RNA-seq (rRNA depletion) [24] |

| Strand-Specific Library Kits | Preserve information on the transcribed DNA strand, crucial for analyzing antisense or overlapping transcripts. | dUTP-based Strand-Specific Protocols [24] |

| Cy7.5 | Cy7.5, CAS:847180-48-7, MF:C43H46N2O14S4, MW:943.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| BiDil | BiDil Research Compound: Isosorbide Dinitrate/Hydralazine HCl | BiDil is a fixed-dose combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine HCl for heart failure research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

A Practical Workflow for Exploratory Quality Assessment

Implementing a systematic workflow is essential for effective artifact detection. The following steps integrate the methodologies previously described:

- Assemble a Multidisciplinary Team: Success in spatial transcriptomics requires tight coordination between molecular biologists, pathologists, histotechnologists, and computational analysts from the project's inception [27].

- Perform Initial Data Inspection: Before formal analysis, conduct exploratory visualization of raw data distributions, spatial patterns of total read counts, and PCA to identify major sources of variation that may indicate technical biases [28].

- Run Automated Artifact Detection: Apply frameworks like BLADE for spatial data to statistically test for border, location, and tissue edge effects [23]. For bulk RNA-seq, use tools like FastQC and Qualimap.

- Quantify and Filter Based on Uncertainty: When using imputation methods like VISTA, use the provided uncertainty estimates (VISTAgene and VISTAcell) to filter low-confidence predictions before downstream analysis [25].

- Integrate Pathological Assessment: Correlate computational artifact detection with histological review by a pathologist to distinguish technical noise from genuine biological features like necrosis or fibrosis [27].

Diagram 2: Statistical detection workflow for spatial artifacts.

In transcriptomics research, Exploratory Data Analysis serves as the critical first step for transforming raw data into biological insights. EDA emphasizes visualizing data to summarize its main characteristics, often using statistical graphics and other data visualization methods, rather than focusing solely on formal modeling or hypothesis testing [29]. For transcriptomic data, which is inherently multivariate and high-dimensional, initial visualization through distribution plots and summary statistics allows researchers to assess data quality, identify patterns, detect anomalies, and form initial hypotheses before proceeding to more complex analyses. This approach, championed by John Tukey since 1970, encourages statisticians to explore data and possibly formulate hypotheses that could lead to new data collection and experiments [29]. In the context of modern transcriptomics, where RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) produces massive matrices of read counts across genes and samples, effective EDA is indispensable for reliable downstream interpretation and biomarker discovery [12] [8].

Data Quality Assessment and Preprocessing

Initial Data Inspection and Cleaning

Before generating distribution plots, transcriptomics data must undergo thorough quality assessment and preprocessing. The initial data structure typically consists of a matrix where rows represent genes and columns represent samples, with values being mapped read counts [8]. The first step involves importing and inspecting this data to understand its structure, variable types, and potential issues [30]. Researchers should examine data dimensions (number of genes and samples), identify data types, and check for obvious errors or inconsistencies [30]. This stage often reveals missing values, which must be addressed through appropriate methods such as filtering lowly expressed genes, imputation, or removal of problematic samples [12] [30].

Normalization and Batch Effect Correction

Normalization is crucial for correcting technical biases in transcriptomics data, including differences in library size and RNA composition [12]. Common normalization methods include TPM and FPKM, which adjust for technical variability to enable meaningful comparisons between samples [12]. Following normalization, batch effect correction addresses technical variation introduced by experimental batches that could confound biological signals. Methods such as ComBat or surrogate variable analysis can effectively correct for these batch effects [12]. Without these preprocessing steps, distribution plots may reflect technical artifacts rather than biological truth, leading to erroneous conclusions in downstream analyses.

Table 1: Key Preprocessing Steps for Transcriptomics Data

| Processing Step | Purpose | Common Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Normalization | Correct technical biases (library size, RNA composition) | TPM, FPKM, DESeq2, edgeR |

| Filtering | Remove lowly expressed genes and poor-quality samples | Mean-based thresholding, variance filtering |

| Batch Correction | Adjust for technical variation between experimental batches | ComBat, Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA) |

| Quality Control | Identify and address problematic samples | PCA, sample correlation analysis |

Fundamental Distribution Plots for Transcriptomics

Histograms and Density Plots

Histograms and density plots provide the most straightforward visualization of gene expression distributions across samples. These plots display the frequency of expression values, allowing researchers to assess the overall distribution shape, central tendency, and spread. In transcriptomics, these visualizations help identify whether data follows an expected distribution, detect outliers, and confirm the effectiveness of normalization procedures. For example, after proper normalization, expression distributions across samples should exhibit similar shapes and centers, indicating comparable technical quality. Density plots are particularly valuable for comparing multiple samples simultaneously, as they can be overlaid to facilitate direct visual comparison of distribution characteristics.

Box Plots and Violin Plots

Box plots summarize key distributional characteristics through a five-number summary: minimum, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum [29]. These plots enable quick comparison of expression distributions across multiple samples or experimental conditions. The box represents the interquartile range (IQR) containing the middle 50% of the data, while whiskers typically extend to 1.5 times the IQR, with points beyond indicating potential outliers. In transcriptomics EDA, side-by-side boxplots of samples help identify outliers, assess normalization success, and visualize overall distribution similarities or differences [8]. Violin plots enhance traditional box plots by adding a rotated kernel density plot on each side, providing richer information about the distribution shape, including multimodality that might be biologically significant.

Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function (ECDF) Plots

ECDF plots visualize the cumulative probability of expression values, displaying the proportion of genes with expression less than or equal to each value. These plots are particularly useful for comparing overall distribution shifts between experimental conditions, as they capture differences across the entire expression range rather than just summary statistics. ECDF plots can reveal subtle but consistent changes in distribution that might be missed by other visualization methods, making them valuable for quality assessment and initial hypothesis generation in transcriptomics EDA.

Multivariate Visualization Techniques

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Plots

PCA plots are essential for visualizing high-dimensional transcriptomic data in reduced dimensions, typically 2D or 3D space [31]. PCA identifies the principal components that capture the greatest variance in the data, allowing researchers to project samples into a coordinate system defined by these components. The resulting scatter plots reveal sample clustering patterns, potential outliers, and major sources of variation in the dataset. In transcriptomics EDA, PCA plots help assess whether biological replicates cluster together and whether experimental conditions separate as expected. Unexpected clustering may indicate batch effects, outliers, or previously unrecognized biological subgroups. The proportion of variance explained by each principal component provides quantitative insight into the relative importance of different sources of variation in the dataset.

Parallel Coordinate Plots

Parallel coordinate plots represent each gene as a line across parallel axes, where each axis corresponds to a sample or experimental condition [8]. These plots are particularly powerful for visualizing expression patterns across multiple samples simultaneously. Ideally, replicates should show flat connections (similar expression levels), while different conditions should show crossed connections (differential expression) [8]. This visualization technique can reveal patterns that might be obscured in dimension-reduction methods like PCA, including distinct expression pattern clusters and outlier genes that behave differently from the majority. When combined with clustering analysis, parallel coordinate plots can effectively visualize groups of genes with similar expression profiles across samples, facilitating the identification of co-expressed gene modules and potential regulatory networks [8].

Scatterplot Matrices

Scatterplot matrices display pairwise relationships between samples in a grid format, with each cell showing a scatterplot of one sample against another [8]. In these plots, most genes should fall along the x=y line for replicate comparisons, while treatment comparisons should show more spread, indicating differentially expressed genes [8]. Scatterplot matrices provide a comprehensive overview of data structure and relationships, allowing researchers to quickly identify problematic samples with poor correlation to their replicates and assess the overall strength of biological signals. Interactive versions of these plots enable researchers to hover over and identify specific genes of interest, facilitating the connection between visualization and biological interpretation [8].

Table 2: Multivariate Visualization Techniques for Transcriptomics EDA

| Technique | Key Applications | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| PCA Plot | Identifying major sources of variation, detecting outliers, assessing sample clustering | Biological replicates should cluster tightly; treatment groups should separate along principal components |

| Parallel Coordinate Plot | Visualizing expression patterns across multiple conditions, identifying gene clusters | Flat lines between replicates indicate consistency; crossed lines between treatments indicate differential expression |

| Scatterplot Matrix | Assessing sample relationships, identifying technical artifacts | Points should cluster tightly along diagonal for replicates; more spread expected between treatment groups |

Key Descriptive Statistics

Summary statistics provide quantitative measures of central tendency, dispersion, and shape for gene expression distributions. Essential statistics for transcriptomics EDA include:

- Measures of central tendency: Mean and median expression values across samples

- Measures of dispersion: Variance, standard deviation, and interquartile range

- Distribution shape: Skewness and kurtosis

- Extreme values: Minimum and maximum expression values

These statistics should be calculated for each sample and compared across experimental conditions. Significant differences in these summary measures between similar samples may indicate technical issues requiring investigation before proceeding with downstream analyses. The pandas describe() function in Python provides a convenient method for generating these basic statistical summaries [30].

Sample-Level Quality Metrics

In addition to gene expression distribution statistics, sample-level quality metrics are essential for EDA in transcriptomics:

- Total read counts: Indicates sequencing depth for each sample

- Number of detected genes: Count of genes above expression threshold

- Ratio of reads mapping to specific genomic features: Proportion of ribosomal, mitochondrial, or other specific RNA types

- Sample correlation coefficients: Pairwise correlations between samples based on gene expression

Systematic differences in these metrics between experimental groups may indicate technical biases that could confound biological interpretations. For example, significantly lower total read counts in one treatment group could artificially reduce apparent expression levels rather than reflecting true biological differences.

Implementation and Tools

Programming Languages and Packages

The implementation of EDA for transcriptomics primarily relies on R and Python, which have extensive ecosystems of packages specifically designed for genomic data analysis [32]. R is particularly strong for statistical analysis and visualization, with packages like DESeq2, edgeR, and limma for differential expression analysis, and ggplot2 for visualization [12] [33]. Python offers robust data manipulation capabilities through pandas and numpy, and visualization through matplotlib and seaborn [30]. The choice between these languages often depends on researcher preference and specific analytical needs, with many bioinformatics leveraging both through interoperability tools like reticulate (R) and rpy2 (Python) [32].

Specialized Transcriptomics Tools

Several specialized tools facilitate EDA for transcriptomics data:

- OMnalysis: An R Shiny-based web application that provides a platform for analyzing and visualizing differentially expressed data, supporting multiple visualization types and extensive pathway enrichment analysis [33]

- bigPint: An R package providing interactive visualization tools specifically designed for RNA-seq data, including parallel coordinate plots and scatterplot matrices [8]

- IRIS and iDEP: Integrated systems for RNA-seq data analysis and interpretation that combine preprocessing, visualization, and functional analysis capabilities [33]

These tools enable researchers without advanced programming skills to perform comprehensive EDA, though custom scripts in R or Python offer greater flexibility for specialized analyses.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Transcriptomics EDA

| Tool/Package | Language | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2/edgeR | R | Differential expression analysis | Statistical methods for identifying DEGs, quality assessment features |

| ggplot2 | R | Data visualization | Flexible, layered grammar of graphics for publication-quality plots |

| pandas | Python | Data manipulation | Data structures and operations for manipulating numerical tables and time series |

| matplotlib/seaborn | Python | Data visualization | Comprehensive 2D plotting library with statistical visualizations |

| OMnalysis | R/Shiny | Integrated analysis platform | Multiple visualization types, pathway analysis, literature mining |

| bigPint | R | RNA-seq visualization | Interactive parallel coordinate plots, scatterplot matrices |

Integration with Downstream Analysis

Effective initial visualization and summary statistics create a foundation for all subsequent transcriptomics analyses. The insights gained from EDA inform feature selection strategies, guide the choice of statistical models for differential expression testing, and help determine appropriate multiple testing correction approaches [12]. Distribution characteristics observed during EDA may suggest data transformations needed to meet statistical test assumptions, while outlier detection can prevent anomalous samples from skewing results. Furthermore, patterns identified through multivariate visualizations like PCA can generate biological hypotheses about co-regulated gene groups or previously unrecognized sample subgroups worthy of further investigation. By investing thorough effort in initial visualization and summary statistics, researchers establish a solid basis for rigorous, reproducible, and biologically meaningful transcriptomics research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Transcriptomics EDA

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Transcriptomics EDA |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Expression Packages | DESeq2, edgeR, limma | Identify statistically significant differentially expressed genes between conditions |

| Visualization Libraries | ggplot2, matplotlib, seaborn, plotly | Create static and interactive distribution plots, summary visualizations |

| Data Manipulation Frameworks | pandas, dplyr | Data cleaning, transformation, and summary statistics calculation |

| Interactive Analysis Platforms | OMnalysis, IRIS, iDEP | Integrated environments for visualization and analysis without extensive coding |

| Specialized RNA-seq Visualizers | bigPint, EnhancedVolcano | Domain-specific visualizations for quality control and result interpretation |

| Pathway Analysis Tools | clusterProfiler, ReactomePA | Biological interpretation of expression patterns in functional contexts |

| CpODA | CpODA | High-purity CpODA for research on colorless, high-temperature polyimides. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

From Reads to Insights: Analytical Methods and Their Practical Applications

Within the broader thesis on best practices for exploratory data analysis in transcriptomics research, the preprocessing of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data represents a foundational step whose quality directly determines the validity of all subsequent biological interpretations. This initial phase transforms raw sequencing output into structured, analyzable count data, forming the essential substrate for hypothesis testing and discovery. The preprocessing workflow typically involves three core, sequential stages: the trimming of raw reads to remove low-quality sequences and adapters, the alignment of these cleaned reads to a reference genome or transcriptome, and finally, the quantification of gene or transcript abundances [34] [35]. Variations in tool selection and parameter configuration at each stage can introduce significant technical variability, potentially confounding biological signals [36]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of current standards and methodologies for each step of the bulk RNA-seq preprocessing pipeline, with a focus on equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to make informed, reproducible choices in their transcriptomic studies.

The Trimming and Quality Control Stage

Purpose and Key Considerations

The initial quality control (QC) and trimming step serves to eliminate technical artifacts and sequences that could compromise downstream analysis. Raw RNA-seq reads can contain adapter sequences, poor-quality nucleotides, and other contaminants introduced during library preparation and sequencing. Trimming these elements increases mapping rates and the reliability of subsequent quantification while reducing computational overhead [35]. However, this process must be performed judiciously, as overly aggressive trimming can reduce data volume and potentially alter expression measures, while overly permissive thresholds may leave problematic sequences in the dataset [35].

Essential Quality Metrics and Tools

A robust QC protocol involves checks both before and after trimming. For raw reads, key metrics include sequence quality scores, GC content, the presence of adapters, overrepresented k-mers, and duplicate read levels [34] [37]. FastQC is a widely adopted tool for this initial assessment, providing a comprehensive visual report on these metrics for Illumina platform data [34] [37]. Following inspection, trimming is performed with tools such as Trimmomatic or the FASTX-Toolkit, which can remove adapters, trim low-quality bases from read ends, and discard reads that fall below a minimum length threshold [34] [35].

It is critical to assess for external contamination, particularly when working with clinical or environmental samples. Tools like FastQ Screen can be employed to determine if a portion of the library aligns to unexpected reference genomes (e.g., microbial contaminants), while Kraken can provide detailed taxonomic classification of such sequences [37]. The completeness of this stage is confirmed by re-running FastQC on the trimmed reads to verify improvement in quality metrics.

Table 1: Key Tools for Read Trimming and Quality Control

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Features/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Quality Control Analysis | Generates a comprehensive HTML report with graphs and tables for per-base/read sequence quality, GC content, adapter content, etc. [34] [37] |

| Trimmomatic | Read Trimming | Flexible tool for removing adapters and trailing low-quality bases; can handle paired-end data [34] [35] |

| FASTX-Toolkit | Read Trimming/Processing | A collection of command-line tools for preprocessing FASTQ files [34] |

| FastQ Screen | Contamination Screening | Checks for the presence of reads from multiple genomes (e.g., host, pathogen, etc.) [37] |

The following workflow diagram outlines the sequential steps and decision points in the quality control and trimming process.

The Alignment Stage

Mapping Reads to a Reference

Following trimming, the cleaned reads are aligned (mapped) to a reference genome or transcriptome. The choice between a genome and transcriptome reference depends on the research goals and the quality of existing annotations. Mapping to a genome allows for the discovery of novel transcripts and splicing events, whereas mapping to a transcriptome can be faster and is sufficient for quantification of known transcripts [34]. The alignment process for RNA-seq data is complicated by spliced transcripts, where reads span exon-exon junctions. Therefore, specialized splice-aware aligners are required [34].

Comparison of Splice-Aware Aligners

Several robust tools are available for this task. STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) is a popular aligner known for its high accuracy and speed, though it can be memory-intensive [20] [38] [39]. HISAT2, a successor to TopHat, is notably fast and has a low memory footprint, making it an excellent choice for standard experiments [35]. BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner), while sometimes used for RNA-seq, is more common in genomic DNA analyses. Benchmarking studies often indicate that tools like STAR and HISAT2 achieve high alignment rates and perform well in identifying junctions, with the "best" choice often being a balance of accuracy, computational resources, and project-specific needs [35].

Post-Alignment Quality Control

Once reads are aligned, a second layer of quality control is critical. Key metrics include the overall alignment rate (a low percentage can indicate contamination or poor-quality reads), the distribution of reads across genomic features (e.g., exons, introns, UTRs), and the uniformity of coverage across genes [34] [37]. Tools like Picard Tools' CollectRnaSeqMetrics, RSeQC, and Qualimap are invaluable for this stage [34] [37]. They can reveal issues such as 3' bias (often a sign of RNA degradation in the starting material) or an unusually high fraction of reads aligning to ribosomal RNA, indicating inefficient rRNA depletion [34] [37].

Table 2: Key Tools for Read Alignment and Post-Alignment QC

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Features/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| STAR | Splice-Aware Alignment | Fast, highly accurate, sensitive for junction mapping; requires significant memory [35] [20] [38] |

| HISAT2 | Splice-Aware Alignment | Very fast with low memory requirements; suitable for most standard analyses [35] |

| Picard Tools | Post-Alignment QC | Suite of tools; CollectRnaSeqMetrics reports read distribution across gene features and identifies 3' bias [34] [37] |

| RSeQC | Post-Alignment QC | Comprehensive Python package with over 20 modules for evaluating RNA-seq data quality [34] [37] |

The Quantification Stage

Traditional and Modern Quantification Approaches

The final preprocessing step is quantification, which involves tallying the number of reads or fragments that originate from each gene or transcript. The traditional approach involves processing the aligned BAM files through counting tools like HTSeq or featureCounts, which assign reads to genes based on the overlap of their genomic coordinates with annotated features [35] [39].

A modern and highly efficient alternative is pseudoalignment, implemented by tools such as Salmon and kallisto. These tools perform alignment, counting, and normalization in a single, integrated step without generating large intermediate BAM files [35] [20]. They work by rapidly determining the compatibility of reads with a reference transcriptome, which drastically reduces computation time and resource usage. A key advantage of this approach is its ability to naturally handle reads that map to multiple genes (multi-mapping reads) and to automatically correct for sequence-specific and GC-content biases [20]. Furthermore, when used with the tximport or tximeta R/Bioconductor packages, these tools produce count matrices and normalization offsets that account for potential changes in gene length across samples (e.g., from differential isoform usage), enhancing the accuracy of downstream differential expression analysis [20].

Normalization and Count Matrices

A critical principle at this stage is that the output for statistical analysis of differential expression must be a matrix of raw, un-normalized counts [20] [38] [39]. Methods like DESeq2 and edgeR are designed to model count data and incorporate internal normalization procedures to account for differences in library size. Providing them with pre-normalized data (e.g., FPKM, TPM) violates their statistical models and leads to invalid results [20] [39]. While normalization methods like TMM (from edgeR) and RLE (from DESeq2) are used internally by these packages, the initial input must be integer counts [35].

Table 3: Key Tools for Quantification and Normalization

| Tool | Method | Key Features/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| HTSeq / featureCounts | Alignment-based Counting | Generate raw count matrices from BAM files; standard input for DESeq2/edgeR [35] [39] |

| Salmon / kallisto | Pseudoalignment | Fast, accurate; avoid intermediate BAM files; correct for bias and gene length; require tximport for DESeq2 [35] [20] |

| StringTie | Assembly & Quantification | Can be used for transcript assembly and quantification, often with Ballgown for analysis [35] |

| TMM / RLE | Normalization | Internal normalization methods used by edgeR and DESeq2 respectively; ranked highly in comparisons [35] |

The following diagram summarizes the two primary quantification pipelines, highlighting the integration points with downstream differential expression analysis.

The successful execution of an RNA-seq preprocessing pipeline relies on a combination of software tools and curated biological references. The following table details the essential "research reagents" for a typical analysis.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for RNA-seq Preprocessing

| Category | Item | Function and Description |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | Ensembl, GENCODE, RefSeq | A high-quality, annotated reference genome for the target organism (e.g., GRCh38 for human). Serves as the map for read alignment [20] [39]. |

| Annotation File | GTF/GFF File | A Gene Transfer Format file containing the coordinates and structures of all known genes, transcripts, and exons. Essential for read counting and feature assignment [39]. |

| Transcriptome Index | Salmon/kallisto Index | A pre-built index of the reference transcriptome, required for fast pseudoalignment and quantification [20]. |

| Software Management | Conda/Bioconda, Snakemake | Tools for managing software versions and dependencies, and for creating reproducible, scalable analysis workflows [20]. |

| Data Integration | tximport / tximeta (R) | Bioconductor packages that import transcript-level abundance data from pseudo-aligners and aggregate it to the gene-level for use with differential expression packages [20]. |

The preprocessing of RNA-seq data through trimming, alignment, and quantification is a critical path that transforms raw sequence data into a structured count matrix ready for exploratory data analysis and differential expression testing. While no single pipeline is universally optimal, current best practices favor rigorous, multi-stage quality control and the use of modern, efficient tools like HISAT2 or STAR for alignment and Salmon or kallisto for quantification, integrated into statistical frameworks via tximport. By making informed, deliberate choices at each stage of this pipeline and diligently documenting all parameters, researchers can ensure the generation of robust, reliable data. This solid foundation is a prerequisite for meaningful exploratory analysis and the subsequent extraction of biologically and clinically relevant insights from transcriptomic studies.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has fundamentally transformed transcriptomics research by enabling digital quantification of gene expression at an unprecedented resolution. However, the raw data generated—counts of sequencing reads mapped to each gene—are influenced by multiple technical factors that do not reflect true biological variation. Normalization serves as a critical computational correction to eliminate these non-biological biases, ensuring that observed differences in gene expression accurately represent underlying transcript abundance rather than technical artifacts. Without proper normalization, comparisons between samples can be profoundly misleading, potentially leading to erroneous biological conclusions [40] [24].