A Practical Guide to Selecting Stable Reference Genes Using TPM Values from RNA-Seq Data

Accurate gene expression analysis in biomedical research relies heavily on the use of stable reference genes for normalization.

A Practical Guide to Selecting Stable Reference Genes Using TPM Values from RNA-Seq Data

Abstract

Accurate gene expression analysis in biomedical research relies heavily on the use of stable reference genes for normalization. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging Transcripts Per Million (TPM) values from RNA-sequencing data to systematically identify and validate optimal reference genes. We cover the foundational advantages of TPM over other normalization methods, detail a step-by-step bioinformatics workflow for candidate gene selection, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present rigorous validation strategies integrating RT-qPCR. By moving beyond traditional housekeeping genes, this methodology ensures more reliable and reproducible gene expression data across diverse experimental conditions, from basic research to clinical applications.

Why TPM? The Foundation of Accurate Transcriptome Comparison for Reference Gene Discovery

The Critical Role of Stable Reference Genes in Gene Expression Studies

Accurate measurement of gene expression is fundamental to advancing biological research, particularly in fields ranging from plant biology to cancer therapeutics and drug development. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) has emerged as the gold standard for gene expression analysis due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [1]. However, the reliability of qRT-PCR data critically depends on proper normalization to account for technical variations introduced during RNA quality, cDNA synthesis, and amplification efficiency [1]. Reference genes, often called housekeeping genes, serve as internal controls to normalize these variations, enabling accurate quantification of target gene expression [2] [1].

A pervasive challenge in the field is the assumption that traditional reference genes maintain constant expression across all experimental conditions. Growing evidence demonstrates that this assumption is flawed, as the expression of many commonly used reference genes varies significantly across different tissues, developmental stages, and environmental conditions [1] [3] [4]. The incorrect selection of unstable reference genes can generate misleading data, potentially invalidating experimental conclusions and hampering research progress [4]. This application note outlines a robust, transcriptome-guided framework for identifying and validating stable reference genes, with a specific focus on utilizing TPM (Transcripts Per Million) values from RNA sequencing data to enhance the reliability of gene expression studies.

The Critical Importance of Validated Reference Genes

Consequences of Improper Reference Gene Selection

Using inappropriate reference genes can significantly distort gene expression profiles, leading to erroneous biological interpretations. A striking example comes from cancer research, where inhibiting the mTOR kinase pathway to generate dormant cancer cells dramatically altered the expression of commonly used reference genes. Studies revealed that genes encoding cytoskeletal proteins (ACTB) and ribosomal proteins (RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A) underwent substantial expression changes, rendering them categorically unsuitable for normalization in these experimental conditions [4]. Similarly, in spinach research, traditionally employed genes such as GRP and PPR demonstrated significantly lower stability compared to more suitable candidates like EF1α and H3 across developmental stages [2].

The normalization errors introduced by unstable reference genes are not merely statistical artifacts but can reverse the apparent direction of gene expression changes or magnify insignificant effects. This is particularly critical in preclinical drug development, where accurate gene expression data can influence decisions on candidate therapeutic progression. Furthermore, in diagnostic applications, such imprecision could lead to false positives or negatives with direct clinical implications [1] [4].

Key Criteria for Ideal Reference Genes

An optimal reference gene should exhibit consistent expression across all experimental conditions, unaffected by tissue type, developmental stage, environmental stimuli, or pharmacological treatments [2] [1]. Beyond stability, ideal reference genes should demonstrate:

- Moderate to high expression abundance to ensure reliable detection above technical noise [2] [3]

- Low variance across biological replicates and experimental conditions [2]

- Robustness to experimental manipulations including drug treatments, stress conditions, and genetic modifications [4]

No single universal reference gene fulfills all these criteria across diverse experimental contexts, necessitating systematic validation for each specific research application [1].

Transcriptome-Based Identification of Candidate Reference Genes

Leveraging RNA-Seq Data for Candidate Selection

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) provides a powerful, unbiased approach for identifying novel reference gene candidates with stable expression patterns. The high-throughput nature of transcriptome sequencing enables researchers to survey genome-wide expression stability across multiple conditions, moving beyond the limited panel of traditionally employed housekeeping genes [2] [3] [5].

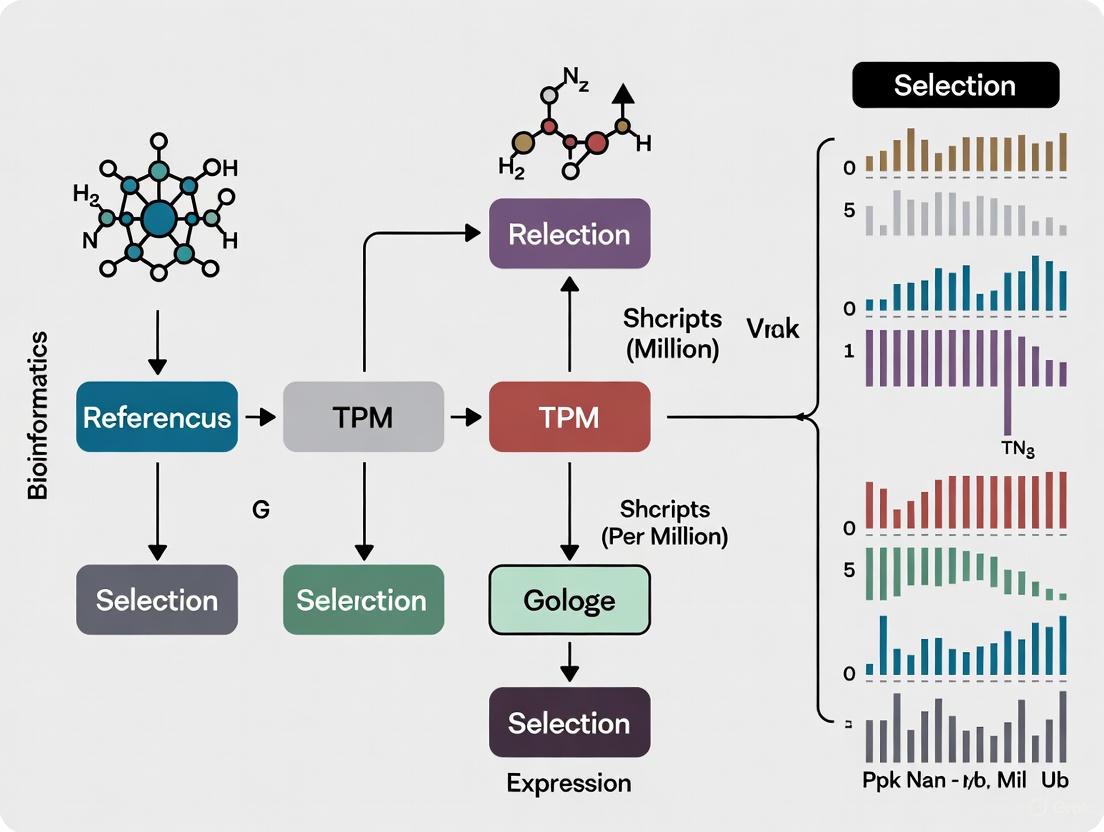

The following workflow illustrates the key steps for transcriptome-based identification of candidate reference genes:

Quantitative Filtering Criteria

The application of stringent quantitative filters to RNA-Seq data enables systematic identification of candidate reference genes with desirable expression characteristics:

Table 1: Quantitative Criteria for Candidate Reference Gene Selection from RNA-Seq Data

| Criterion | Threshold | Rationale | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Level | Mean logâ‚‚(TPM) > 5 | Ensures moderate to high expression for reliable qRT-PCR detection | In Urechis unicinctus, candidate genes had median logâ‚‚(TPM) of 14.16-16.32 [5] |

| Expression Variance | SD logâ‚‚(TPM) < 1 | Selects genes with low variability across samples | Identified 1,196 stable candidates from 25,496 genes in spinach transcriptome [2] |

| Expression Stability | Coefficient of Variation (CV) < 0.2 | Further refines selection to most stable genes | Applied in multiple species including echiuran worm and Japanese flounder [3] [5] |

These criteria have been successfully applied across diverse organisms. In spinach, this approach identified 1,196 stable candidate genes from an initial pool of 25,496 [2]. Similarly, studies in Japanese flounder and the echiuran worm Urechis unicinctus demonstrated the effectiveness of transcriptome-based selection, where candidate reference genes significantly outperformed traditional housekeeping genes in expression stability [3] [5].

Experimental Validation of Candidate Reference Genes

Comprehensive Validation Workflow

Candidate reference genes identified through transcriptome analysis must be experimentally validated using qRT-PCR followed by rigorous statistical analysis. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive validation workflow:

Protocol 1: Reference Gene Validation Protocol

Step 1: Primer Design and Validation

- Design primers with the following characteristics:

- Amplicon length: 75-150 bp

- Primer length: 18-22 nucleotides

- Tm: 60±1°C

- GC content: 40-60%

- Validate primer specificity through:

Step 2: RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

- Extract high-quality RNA (A260/280 ratio: 1.8-2.2, RIN > 7)

- Treat with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination

- Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcriptase with oligo(dT) and/or random primers

- Use uniform RNA input across all samples (e.g., 1 μg) [6] [8]

Step 3: qRT-PCR Amplification

- Perform reactions in technical triplicates

- Include no-template controls for contamination monitoring

- Use standardized thermal cycling conditions:

Step 4: Data Analysis

- Calculate amplification efficiencies from standard curves

- Determine Ct values using consistent threshold settings

- Analyze expression stability using multiple algorithms [2] [6]

Statistical Algorithms for Stability Assessment

No single statistical method comprehensively evaluates reference gene stability. A consensus approach utilizing multiple algorithms provides the most reliable assessment:

Table 2: Statistical Algorithms for Reference Gene Validation

| Algorithm | Primary Metric | Interpretation | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| geNorm | M-value (average expression stability) | Lower M-value indicates greater stability; M < 1.5 generally acceptable | Determines optimal number of reference genes (Vn/Vn+1 < 0.15) [2] [6] |

| NormFinder | Stability value (intra- and inter-group variation) | Lower stability value indicates greater stability | Accounts for sample subgroups within experimental design [2] [6] |

| BestKeeper | Standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) of Ct values | SD < 1 indicates stable expression; lower CV preferred | Based on raw Ct values without transformation [2] [6] |

| RefFinder | Comprehensive ranking (geometric mean) | Integrates results from all above algorithms | Provides consensus ranking from multiple methods [2] [6] |

The following diagram illustrates the multi-algorithm validation process and integration of results:

Condition-Specific Reference Gene Selection

Application Across Biological Contexts

Reference gene stability is highly context-dependent, necessitating condition-specific validation. The table below summarizes optimal reference genes identified through systematic validation across diverse experimental conditions:

Table 3: Condition-Specific Stable Reference Genes

| Experimental Condition | Organism/Cell Type | Most Stable Reference Genes | Least Stable Reference Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Development | Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) | EF1α, H3 [2] | GRP, PPR [2] |

| Abiotic Stress | Japanese Flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) | gatd1, rpl6 [3] | 18S RNA, actb [3] |

| Human Immunology | PBMCs under Hypoxia | RPL13A, S18, SDHA [6] | IPO8, PPIA [6] |

| Cancer Biology | Dormant Cancer Cells (A549) | B2M, YWHAZ [4] | ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A [4] |

| Medicinal Plants | Abelmoschus Manihot | eIF, PP2A1 [7] | TUA [7] |

| Fungal Studies | Inonotus obliquus | VPS (carbon sources), RPB2 (nitrogen sources) [9] | Varies by condition [9] |

These findings underscore that traditional reference genes frequently demonstrate poor stability under specific experimental conditions. For instance, in dormant cancer cells generated through mTOR inhibition, ribosomal protein genes (RPS23, RPS18, RPL13A) and ACTB underwent dramatic expression changes, rendering them unsuitable for normalization [4]. Similarly, in Japanese flounder under temperature stress, transcriptome-identified genes (gatd1, rpl6) significantly outperformed conventionally used genes (18S RNA, actb) [3].

Determining the Optimal Number of Reference Genes

The geNorm algorithm determines the optimal number of reference genes through pairwise variation analysis (Vn/Vn+1). A cut-off value of Vn/Vn+1 < 0.15 indicates that n reference genes are sufficient for reliable normalization [6] [7]. In most cases, the use of two reference genes provides sufficient normalization accuracy, though more complex experimental designs may require three or more reference genes [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Tools for Reference Gene Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | High-quality RNA isolation | Select kits with DNase treatment; assess quality via RIN/RQI [8] |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | cDNA synthesis | Use consistent RNA input; include genomic DNA removal steps [6] [9] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Amplification and detection | SYBR Green for cost-effectiveness; probe-based for multiplexing [1] [6] |

| Reference Gene Validation Algorithms | Stability assessment | Employ multiple algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper) [2] [6] |

| Transcriptome Data | Candidate identification | Filter genes by TPM values (mean logâ‚‚(TPM)>5, SD<1, CV<0.2) [2] [3] |

The systematic identification and validation of stable reference genes is a critical prerequisite for accurate gene expression analysis in all biological research domains. The transcriptome-guided framework presented here, utilizing TPM values from RNA-Seq data combined with rigorous experimental validation, provides a robust methodology for selecting appropriate reference genes tailored to specific experimental conditions. This approach significantly enhances the reliability of qRT-PCR data, ensuring valid biological interpretations and supporting advances in basic research, drug development, and diagnostic applications. As research continues to explore increasingly complex biological systems and interventions, the implementation of these rigorous normalization practices will become ever more essential for generating meaningful and reproducible gene expression data.

Transcripts Per Million (TPM) has emerged as a standard normalization unit for RNA-sequencing data, enabling researchers to account for technical variations in sequencing depth and gene length. This primer provides a comprehensive overview of TPM normalization, its calculation, and its specific application in the critical process of selecting stable reference genes for accurate gene expression analysis. We detail experimental protocols for reference gene validation and present quantitative comparisons of normalization methods to guide researchers in making informed analytical decisions.

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the predominant method for transcriptome profiling, enabling digital gene expression measurement through mapped read counts [10]. However, raw read counts are not directly comparable between genes or samples due to technical biases including sequencing depth (total number of reads per sample) and gene length (longer transcripts accumulate more reads) [10] [11]. Normalization methods are therefore essential to remove these technical artifacts and reveal true biological signals [11].

Several normalization approaches have been developed, with TPM (Transcripts per Million) representing one of the most biologically interpretable units. Unlike earlier methods such as RPKM/FPKM, TPM implements a more logical normalization sequence—first adjusting for gene length, then for sequencing depth—which makes it particularly suitable for comparing the relative abundance of transcripts across samples [12].

Table 1: Common RNA-seq Normalization Methods

| Method | Full Name | Primary Use | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| TPM | Transcripts per Million | Within- and between-sample comparisons (with caution) | Normalizes for gene length first, then sequencing depth; sum is constant across samples [12] |

| RPKM/FPKM | Reads/Fragments Per Kilobase per Million | Within-sample comparisons | Normalizes for sequencing depth first, then gene length; sum varies between samples [10] [12] |

| TMM | Trimmed Mean of M-values | Between-sample comparisons | Assumes most genes are not differentially expressed; robust to outliers [11] [13] |

| RLE | Relative Log Expression | Between-sample comparisons | Uses median of ratios for normalization; implemented in DESeq2 [13] |

Understanding TPM: Calculation and Interpretation

The Mathematics Behind TPM

The TPM calculation involves a two-step process that fundamentally differs from RPKM/FPKM in its operation sequence. For a gene i, TPM is calculated as follows [10] [11]:

Normalize for gene length: Divide the read counts mapped to the gene by the transcript length in kilobases: [ \text{Length-normalized reads} = \frac{\text{Reads mapped to gene}_i}{\text{Transcript length (kb)}} ]

Normalize for sequencing depth: Divide the length-normalized reads by the sum of all length-normalized reads in the sample (in millions): [ \text{TPM}i = \frac{\text{Reads mapped to gene}i / \text{Transcript length (kb)}}{\sum (\text{Reads mapped to all genes} / \text{Respective transcript lengths})} \times 10^6 ]

This calculation produces a normalized value where the sum of all TPM values in a sample equals one million, facilitating interpretation as the number of transcripts that would have been observed if exactly one million full-length transcripts had been sequenced [10] [11].

Advantages and Limitations

TPM offers several advantages over other normalization units. It fulfills the invariance property, meaning the average TPM is constant across samples (approximately 10ⶠdivided by the number of annotated transcripts) [10]. This makes TPM values more comparable across samples than RPKM/FPKM values, whose sums vary between samples.

However, a critical limitation exists: TPM represents relative abundance rather than absolute transcript counts. The relative abundance of a transcript depends on the composition of the entire RNA population in a sample [10]. When samples have significantly different transcriptome compositions—such as those prepared with different protocols (poly(A)+ selection vs. rRNA depletion)—TPM values may not be directly comparable even after normalization [10].

Figure 1: TPM Calculation Workflow. The process involves sequential normalization for transcript length followed by sequencing depth.

The Critical Role of Reference Genes and TPM in Their Selection

The Importance of Reference Genes in Gene Expression Studies

Reference genes (also called housekeeping genes or normalizing genes) serve as internal controls in gene expression studies to correct for technical variations in RNA extraction, reverse transcription efficiency, and overall cDNA input [1] [14]. The fundamental requirement for a reference gene is stable expression across all experimental conditions being studied [1]. Traditional reference genes like ACTB (actin), GAPDH, and TUBB (tubulin) were once widely assumed to have constant expression, but numerous studies have demonstrated that their expression can vary significantly across different tissues, developmental stages, and experimental conditions [1] [14].

The use of inappropriate reference genes that show systematic variation under experimental conditions can lead to inaccurate normalization and consequently, erroneous conclusions about target gene expression [1]. This is particularly critical in fields like drug development, where accurate biomarker quantification directly impacts decisions about compound efficacy and toxicity.

TPM as a Foundation for Reference Gene Selection

RNA-seq data normalized with TPM provides an ideal starting point for identifying stably expressed genes across experimental conditions. The TPM unit offers advantages for this application because it: (1) normalizes for both sequencing depth and gene length, allowing fair comparison across samples; (2) represents relative molar concentration, making it biologically interpretable; and (3) produces values where the sum is constant across samples, facilitating stability assessments [10] [15].

A key metric for evaluating gene expression stability using TPM values is the coefficient of variation (CV), calculated as the standard deviation divided by the mean TPM across samples [15] [14]. Genes with lower CV values demonstrate more stable expression and are therefore stronger candidates as reference genes. Additional statistical measures including fold change (FC) values further help identify genes with minimal expression fluctuation [14].

Table 2: Metrics for Evaluating Reference Gene Stability Using TPM Data

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Optimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Standard Deviation / Mean TPM | Lower values indicate more stable expression | < 0.3-0.5 [14] |

| Fold Change (FC) | Maximum TPM / Minimum TPM | Measures expression range across conditions | Close to 1 [14] |

| Mean TPM | Average TPM across all samples | Filters out lowly expressed genes | > 5 TPM [14] |

Experimental Protocol: Selecting Reference Genes Using TPM Values

Candidate Gene Identification from RNA-seq Data

Purpose: To identify genes with stable expression from RNA-seq data for use as reference genes in qRT-PCR experiments.

Materials and Reagents:

- RNA-seq data (FASTQ files) from all experimental conditions

- Reference genome/transcriptome appropriate for your species

- High-performance computing cluster or workstation

- RNA-seq quantification software (Salmon, Kallisto, or RSEM)

Procedure:

- Process RNA-seq data: Quantify transcript abundance using alignment-free tools like Salmon [10] or Kallisto, or alignment-based tools like RSEM [16]. These tools directly output TPM values.

- Generate TPM matrix: Compile TPM values for all genes across all samples into a single matrix.

- Filter lowly expressed genes: Remove genes with mean TPM < 5 across all samples, as low-expression genes present technical challenges in qRT-PCR validation [14].

- Calculate stability metrics: For each gene, compute:

- Coefficient of variation (CV = standard deviation/mean) of TPM values

- Fold change (FC = maximum TPM/minimum TPM) across samples

- Mean TPM value

- Rank genes by stability: Sort genes by ascending CV values. Genes with CV < 0.5 and FC < 2 typically represent good candidates [14].

- Select top candidates: Choose 10-15 genes with the lowest CV values for experimental validation.

Experimental Validation of Candidate Reference Genes

Purpose: To validate the expression stability of candidate reference genes using qRT-PCR across all experimental conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- RNA samples from all experimental conditions and replicates

- RNA extraction kit (e.g., TRIzol, column-based kits)

- DNase I treatment kit

- Reverse transcription kit with random hexamers and/or oligo-dT primers

- qPCR machine and SYBR Green master mix

- Primer pairs for candidate reference genes and target genes of interest

Procedure:

- RNA extraction and qualification: Extract total RNA from all samples. Quantify RNA concentration and assess purity (A260/A280 ratio ~2.0) and integrity (RIN > 7) [1].

- cDNA synthesis: Perform reverse transcription with consistent RNA input (e.g., 1 µg) across all samples using a high-efficiency reverse transcription kit.

- qPCR optimization: Design and validate primer pairs for each candidate reference gene. Ensure amplification efficiency between 90-110% with single peak in melting curves [14].

- qPCR run: Perform qPCR reactions for all candidate genes across all samples in technical replicates.

- Stability analysis: Analyze Ct values using multiple algorithms:

- geNorm: Calculates expression stability value (M); lower M indicates greater stability [15] [14]

- NormFinder: Estimates intra- and inter-group variation; provides stability value [15] [14]

- BestKeeper: Uses pairwise correlations of Ct values [14]

- ΔCt method: Compares relative expression of pairs of genes [14]

- Comprehensive ranking: Use RefFinder or similar tools to integrate results from all algorithms and generate a comprehensive stability ranking [17].

- Final selection: Choose the top 2-3 most stable genes for normalization in subsequent experiments.

Figure 2: Reference Gene Selection and Validation Workflow. The process integrates computational identification from RNA-seq data with experimental validation using qRT-PCR.

Comparative Analysis of Normalization Methods

Performance in Downstream Applications

Multiple studies have compared the performance of TPM with other normalization methods in various analytical contexts. While TPM is excellent for within-sample comparisons and relative abundance assessment, other methods may outperform it for specific cross-sample applications.

In a comprehensive benchmark study evaluating normalization methods for mapping RNA-seq data to genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), between-sample normalization methods (TMM, RLE) produced more consistent results than within-sample methods (TPM, FPKM) [13]. Specifically, TMM, RLE, and GeTMM (a hybrid method) enabled generation of condition-specific metabolic models with considerably lower variability in the number of active reactions compared to TPM and FPKM [13].

Similarly, in analyzing RNA-seq data from patient-derived xenograft models, hierarchical clustering based on normalized count data (using between-sample methods) grouped replicate samples more accurately than TPM and FPKM data [16]. Normalized count data also demonstrated lower median coefficient of variation and higher intraclass correlation values across replicate samples [16].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Normalization Methods in Various Applications

| Application Context | Recommended Method(s) | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference gene selection | TPM (for initial screening) | TPM enables calculation of coefficient of variation for stability assessment | [15] [14] |

| Metabolic model reconstruction | TMM, RLE, GeTMM | Between-sample methods produced models with lower variability and better captured disease-associated genes | [13] |

| Sample clustering accuracy | Normalized counts (DESeq2, edgeR) | Outperformed TPM/FPKM in grouping replicate samples from same model | [16] |

| Differential expression analysis | Normalized counts (DESeq2, edgeR) | More robust to different library sizes and compositions | [16] |

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TPM-Based Reference Gene Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Products/Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality total RNA with preservation of mRNA integrity | TRIzol, column-based kits (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy) |

| RNA Integrity Assessment | Quality control of RNA samples prior to library preparation | Bioanalyzer, TapeStation (RIN/RQI scores) |

| Library Preparation Kits | Construction of sequencing libraries with minimal bias | Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep, NEBNext Ultra II |

| RNA-seq Quantification Tools | Transcript abundance estimation with TPM output | Salmon, Kallisto, RSEM [10] [16] |

| qPCR Reagents | Experimental validation of candidate reference genes | SYBR Green master mixes, TaqMan assays |

| Stability Analysis Algorithms | Computational assessment of gene expression stability | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, RefFinder [14] [17] |

TPM normalization provides a robust foundation for reference gene selection in transcriptomic studies, particularly through its ability to enable cross-sample comparison of relative transcript abundance while accounting for technical variables. The integration of computational identification of stable genes from TPM-normalized RNA-seq data with experimental validation using qRT-PCR represents a powerful strategy for establishing reliable normalization standards in gene expression research. As transcriptomic applications continue to evolve in complexity—spanning diverse tissues, experimental conditions, and disease states—the rigorous selection of reference genes using TPM-based approaches will remain essential for generating accurate, reproducible biological insights, particularly in critical applications like drug development and clinical biomarker identification.

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, the raw read counts mapped to a gene are dependent not only on the gene's actual expression level but also on the gene's length and the library's sequencing depth [10]. Normalization is, therefore, an essential step to eliminate these technical biases and enable accurate biological interpretation [18]. Reads Per Kilobase Million (RPKM) and its paired-end counterpart, Fragments Per Kilobase Million (FPKM), were among the earliest measures developed for this purpose [19]. More recently, Transcripts Per Million (TPM) has emerged as a superior alternative, particularly for studies comparing expression profiles across different samples [19] [20]. This application note delineates the critical differences between these normalization methods, provides empirical evidence for the superiority of TPM in cross-sample comparison, and details protocols for its application in robust transcriptomic analysis, with a specific focus on the selection of reference genes.

Understanding the Normalization Methods: RPKM, FPKM, and TPM

Core Concepts and Calculations

While RPKM, FPKM, and TPM all aim to correct for sequencing depth and gene length, they differ fundamentally in their order of operations, which has profound implications for their interpretation.

RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads): Developed for single-end RNA-seq, this method calculates normalized expression as follows [19] [20]:

- Normalize for sequencing depth: Divide the read counts by the total number of reads in the sample (in millions), yielding Reads Per Million (RPM).

- Normalize for gene length: Divide the RPM values by the gene length in kilobases.

FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase per Million mapped fragments): This is the direct equivalent of RPKM for paired-end RNA-seq data. It accounts for the fact that two reads can originate from a single fragment, thus preventing double-counting [19]. The calculation steps are identical to RPKM, with "reads" replaced by "fragments."

TPM (Transcripts Per Million): This method involves the same two normalization factors but reverses the order of operations [19] [20]:

- Normalize for gene length: Divide the read counts by the gene length in kilobases, yielding Reads Per Kilobase (RPK).

- Normalize for sequencing depth: Sum all RPK values in a sample, divide by 1,000,000 to get a scaling factor, and then divide each RPK value by this factor.

The distinction in calculation is subtle but critical. TPM normalizes for gene length first, followed by sequencing depth, which results in a normalized value that represents the relative molar concentration of a transcript within the total pool of sequenced transcripts [10].

Comparative Analysis: A Direct Comparison

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each method to facilitate a direct comparison.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of RPKM/FPKM and TPM Normalization Methods

| Feature | RPKM/FPKM | TPM |

|---|---|---|

| Full Name | Reads/Fragments Per Kilobase per Million | Transcripts Per Million |

| Primary Use Case | Gene expression comparison within a single sample [18] | Gene expression comparison both within and between samples [18] |

| Order of Normalization | 1. Sequencing depth2. Gene length | 1. Gene length2. Sequencing depth |

| Sum of All Values | Variable across samples [19] | Constant (1,000,000) across samples [19] |

| Biological Interpretation | Measures reads/fragments per kb per million | Measures the proportion of transcripts in a million transcripts [10] |

| Recommended for Cross-Sample Comparison | No | Yes |

The Critical Advantage of TPM for Cross-Sample Comparison

The Invariance Principle and Proportionality

The most significant advantage of TPM is that the sum of all TPM values in every sample is identical—one million [19]. This invariance property means that TPM values directly represent the relative proportion of each transcript within the total transcribed mRNA pool of a sample. Consequently, if Gene A has a TPM of 5,000 in both Sample 1 and Sample 2, one can confidently conclude that the same fraction of total cellular mRNA in both samples is derived from Gene A [20].

In contrast, the sum of all RPKM or FPKM values can differ from sample to sample. Therefore, an RPKM value of 5,000 for Gene A in two different samples does not guarantee that the gene's relative abundance is the same, as the denominator used to calculate the proportion is different [19] [20]. This makes RPKM/FPKM unreliable for direct comparison of expression levels across samples.

Empirical Evidence from Benchmarking Studies

Evidence from benchmarking studies reinforces the theoretical superiority of TPM. Research evaluating normalization methods for mapping RNA-seq data onto genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) found that within-sample normalization methods like TPM and FPKM can lead to high variability in the resulting models compared to between-sample methods [13]. This variability can obscure true biological signals and increase false positive predictions.

Furthermore, the choice of normalization method is critical when sample preparation protocols differ. For instance, poly(A)+ selection and rRNA depletion result in vastly different RNA population compositions. A study demonstrated that in such scenarios, TPM values for the same original sample are not directly comparable between the two protocols because the underlying transcript repertoires are different [10]. This highlights that even TPM values are a measure of relative abundance within the sequenced population, and researchers must be cautious when comparing data generated using different experimental workflows.

Practical Application: Selecting Reference Genes Using TPM

A pivotal application of robust cross-sample comparison is the identification of stable reference genes for downstream validation techniques like RT-qPCR. Traditional, pre-defined "housekeeping" genes often show variable expression under different experimental conditions, leading to normalization errors [1] [15] [21]. Using TPM values from an RNA-seq dataset allows for the data-driven selection of optimal, custom reference genes specific to the experimental system.

Protocol: A Workflow for Selecting Reference Genes from RNA-seq Data

This protocol describes a method to identify the most stably expressed genes from RNA-seq data for use as reference genes in RT-qPCR validation [15] [21].

1. Input Data Preparation:

- Generate a table containing TPM values for all genes across all samples in your experiment. Replicates should be averaged prior to analysis [21].

2. Software and Tools:

- The "Gene Selector for Validation (GSV)" software is an example of a tool designed for this purpose, though custom R or Python scripts can also be implemented based on the following criteria [21].

3. Step-by-Step Filtering Criteria: Apply the following sequential filters to the TPM data to identify optimal reference gene candidates [21]:

- Filter 1: Presence in All Samples. Retain only genes with a TPM value > 0 in every library analyzed.

- Filter 2: Moderate to High Expression. Retain genes with an average log2(TPM) value greater than 5. This ensures the selected genes are expressed at a level easily detectable by RT-qPCR.

- Filter 3: Stable Expression. Retain genes with a low coefficient of variation (CV) of TPM values across samples (e.g., CV < 0.2) and a standard deviation of log2(TPM) smaller than 1.

- Filter 4: Absence of Exceptional Outliers. Exclude genes where the expression in any single library is more than twice the average log2(TPM) across all libraries.

4. Output:

- The final output is a list of genes that pass all filters, ranked by their stability (lowest CV). The top-ranked genes are the most suitable candidates for use as reference genes in subsequent RT-qPCR experiments [15].

The following workflow diagram summarizes this protocol:

Validation of Selected Reference Genes

Genes selected via the above TPM-based pipeline must be empirically validated using algorithms designed for RT-qPCR data. The expression stability of the candidate genes is typically assessed using software such as geNorm [7], NormFinder [15] [7], and BestKeeper [7], which calculate stability measures based on the quantification cycle (Cq) values from the RT-qPCR experiment [21] [7]. A comprehensive validation study on Abelmoschus Manihot, for example, used these algorithms to confirm that eIF and PP2A1 were superior to traditionally used genes like TUA (tubulin alpha) [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Successful implementation of these protocols requires a combination of specific reagents and computational tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries from purified RNA. | Kits are often optimized for poly(A)+ selection or rRNA depletion, a choice that affects results [10]. |

| RT-qPCR Master Mix | Amplification and fluorescence detection during qPCR. | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, and fluorescent dye (e.g., SYBR Green I) [1]. |

| Reference Gene Primers | Gene-specific amplification for RT-qPCR validation. | Primers must be designed for and validated on candidate genes (e.g., eIF, PP2A1) [7]. |

| GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) Software | Identifies stable reference and variable candidate genes from TPM data. | An open-source tool with a graphical interface that applies the filtering protocol [21]. |

| geNorm / NormFinder / BestKeeper | Algorithms to assess expression stability of candidates from RT-qPCR Cq data. | Used for final validation; often employed in concert for a robust conclusion [7]. |

| Oridonin | Oridonin, CAS:28957-04-2, MF:C20H28O6, MW:364.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PI-3065 | PI-3065, MF:C27H31FN6OS, MW:506.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice of normalization method is not merely a technical formality but a fundamental decision that shapes all downstream biological interpretations of RNA-seq data. While RPKM and FPKM remain valid for assessing relative expression between genes within a single sample, TPM is unequivocally superior for comparing the expression of a gene across multiple samples. Its invariant sum property allows researchers to make direct, proportional comparisons, making it the unit of choice for cross-sample analysis. This advantage is particularly critical in applications like the data-driven selection of reference genes, where accurate identification of stably expressed transcripts is paramount for reliable RT-qPCR validation. Adopting TPM and associated robust protocols ensures that transcriptomic insights are both accurate and reproducible.

The GENCODE project represents a cornerstone of modern genomics, with the primary goal of identifying and classifying all gene features in the human and mouse genomes with high accuracy based on biological evidence [22]. This consortium produces a reference gene annotation that is widely recognized for its comprehensive manual curation and experimental validation, serving as the official annotation for major projects including ENCODE, the 1000 Genomes Project, and the International Cancer Genome Consortium [23]. Unlike purely computational annotations, GENCODE combines manual annotation from the HAVANA group with automated annotation from Ensembl, creating a merged gene set that leverages the strengths of both approaches [23]. This integrated annotation strategy is particularly crucial for the accurate identification and selection of reference genes in transcriptomic studies, forming the foundation for reliable gene expression analysis across diverse biological contexts and experimental conditions.

The Critical Role of Reference Genes in Genomic Analysis

Reference genes, often referred to as housekeeping genes, serve as essential internal controls in gene expression studies to correct for technical variations that occur during sample preparation and analysis. The necessity for robust normalization becomes particularly evident in quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) experiments, where differences in RNA extraction efficiency, reverse transcription efficiency, and sample loading can significantly impact results [1]. Without proper normalization using validated reference genes, biological interpretations of gene expression data can be profoundly misleading.

Traditional reference genes such as actin, tubulin, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) have been widely used based on their presumed stable expression across conditions. However, extensive research has demonstrated that the expression of these canonical reference genes can vary considerably across different tissues, developmental stages, and experimental conditions [1] [15]. This variability has driven the field toward more systematic approaches for identifying stably expressed genes specific to particular biological contexts, moving beyond the assumption that traditionally used housekeeping genes maintain constant expression levels.

A Novel TPM-Based Methodology for Custom Reference Gene Selection

The integration of GENCODE annotations with transcriptomic data enables a powerful methodology for identifying optimal, condition-specific reference genes using Transcripts Per Million (TPM) values. This approach represents a significant advancement over traditional methods that rely on predefined candidate genes, offering instead a data-driven selection process based solely on read counts and gene sizes from RNA-seq data [15].

Computational Workflow for TPM-Based Selection

The following workflow outlines the key steps for implementing this methodology:

Detailed Protocol for Custom Reference Gene Selection

Step 1: TPM Normalization of Read Counts Begin by converting raw RNA-seq read counts to TPM values using standard normalization procedures. This critical step accounts for both sequencing depth and gene length variations, enabling meaningful cross-sample comparisons. The TPM calculation involves normalizing read counts by gene length followed by normalization for sequencing depth, producing values that represent the relative abundance of transcripts in the sample [15].

Step 2: Filtering Weakly Expressed Genes Apply the DAFS (Detection Above Background and Filtering Based on Spot Size) script or similar statistical approaches to establish an expression threshold. This filtering step eliminates genes with low, potentially unreliable expression levels that could introduce noise into the reference selection process. The specific threshold should be determined based on the distribution of TPM values in your dataset [15].

Step 3: Coefficient of Variation Calculation For each gene passing the expression filter, calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) across all samples in the experiment. The CV, defined as the standard deviation divided by the mean, quantifies expression stability, with lower values indicating more stable expression. This metric serves as the primary criterion for reference gene selection [15].

Step 4: Selection of Most Stable Genes Identify the 0.5% of genes with the lowest coefficients of variation as your custom reference gene set. This stringent selection ensures that only the most stably expressed genes are chosen for normalization purposes. The resulting gene set is specifically tailored to your experimental conditions and biological system [15].

Comparative Analysis of Reference Gene Selection Methods

The table below provides a systematic comparison of different approaches to reference gene selection, highlighting the advantages of the custom TPM-based method:

Table 1: Comparison of Reference Gene Selection Strategies

| Method Type | Basis of Selection | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Predefined Genes | Historical convention and presumed biological function | Simple to implement; requires minimal computational resources | Often unstable across different conditions; high false normalization risk | Preliminary studies; when no RNA-seq data available |

| Pre-selected Candidate Panels | Previously published stable gene sets for specific organisms | More reliable than traditional genes; some experimental validation | Limited to specific species/conditions; may not transfer well | Targeted qPCR studies with established model systems |

| Custom TPM-Based Selection | Empirical stability metrics from RNA-seq data | Organism-agnostic; condition-specific; no pre-selection bias | Requires RNA-seq data; computational resources needed | RNA-seq follow-up studies; non-model organisms; novel conditions |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that custom-selected reference genes consistently outperform predefined reference genes in transcriptomic analysis. In validation studies, custom-selected genes exhibited lower coefficients of variation and fold change values compared to commonly used reference genes, along with a broader range of expression levels [15]. When evaluated using established algorithms like NormFinder and geNorm, custom-selected genes demonstrated higher stability rankings than traditional reference genes, confirming their superior performance for normalization purposes [15].

Experimental Protocol for Reference Gene Validation

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Reference Gene Analysis

| Reagent/Kit | Manufacturer | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assays | Applied Biosystems | Target-specific qPCR detection | Provides pre-optimized assays for precise quantification [24] |

| TaqMan MicroRNA Arrays | Applied Biosystems | High-throughput miRNA profiling | Enables verification of miRNA expression patterns [25] |

| NCode miRNA Microarray | Invitrogen | Genome-wide miRNA screening | Useful for discovery phase of reference element identification [25] |

| Trizol Reagent | Invitrogen | RNA preservation and extraction | Maintains RNA integrity during sample processing [25] |

| Poly(A) Tailing Kit | Various | RNA labeling for microarray | Essential for microarray-based expression profiling [25] |

Step-by-Step Validation Workflow

Step 1: RNA Extraction and Quality Control Isolate total RNA using Trizol or equivalent reagents according to established protocols. Assess RNA quality using appropriate methods such as the NanoDrop spectrophotometer for purity measurements and the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) for evaluating degradation. Only proceed with samples showing high-quality RNA (A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0 and RIN > 8) to ensure reliable results [25].

Step 2: Reverse Transcription and cDNA Synthesis Convert RNA to cDNA using reverse transcription kits specifically designed for gene expression analysis. For mRNA quantification, use oligo(dT) or random hexamer primers. For miRNA analysis, employ stem-loop reverse transcription primers as used in the TaqMan MicroRNA Array system to ensure specific cDNA synthesis of small RNA species [25].

Step 3: qPCR Amplification and Data Collection Perform quantitative PCR using selected reference genes and target genes of interest. Utilize either SYBR Green chemistry or TaqMan probe-based detection systems. Run all reactions in technical triplicates to account for pipetting variability, and include appropriate negative controls (no-template controls) to detect potential contamination [1].

Step 4: Stability Analysis and Final Selection Analyze the qPCR data using multiple algorithms to comprehensively evaluate reference gene stability. The following diagram illustrates this multi-algorithm validation approach:

Implement four distinct analytical approaches: the Comparative ΔCt method, which compares relative expression of gene pairs; geNorm, which employs a pairwise comparison strategy to determine the most stable genes; NormFinder, which estimates both intra- and inter-group variation; and BestKeeper, which utilizes a correlation-based approach to identify stable genes [17]. Finally, integrate results from all methods using RefFinder or similar composite tools to generate a comprehensive stability ranking, enabling selection of the optimal reference genes for your specific experimental context.

Application Notes and Best Practices

Condition-Specific Reference Gene Selection

Research has consistently demonstrated that optimal reference genes vary significantly across different experimental conditions. Studies in humpback grouper revealed distinct sets of stable reference genes for normal tissues (RPL35 and EEF1G), salinity stress (RPLP1, FH, and METAP2), embryonic development (EIF5A, EIF3F, and CCNG1), and bacterial infection (RPSA, RPL25A, and GNB211) [17]. This underscores the critical importance of validating reference genes for each specific experimental context rather than relying on universal standards.

Integration with GENCODE Annotations

GENCODE annotations provide a crucial framework for accurate reference gene selection by offering comprehensive information on transcript structures, gene biotypes, and supporting evidence. The GENCODE classification system includes three levels of annotation validity: Level 1 (manually annotated and experimentally validated), Level 2 (manually annotated), and Level 3 (automated annotation) [23]. When selecting potential reference genes, prioritize those with Level 1 or Level 2 classifications, as these have undergone more rigorous curation and validation processes.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

When encountering high variability in reference gene expression, consider these troubleshooting approaches: First, verify RNA quality and ensure minimal degradation, as RNA integrity significantly impacts expression stability metrics. Second, increase sample size to improve the statistical power for detecting stably expressed genes, particularly when working with heterogeneous tissues. Third, apply more stringent expression filters to eliminate genes with low abundance that may exhibit higher relative variability. Finally, consider expanding the candidate gene pool beyond protein-coding genes to include stable non-coding RNAs, which may exhibit more consistent expression patterns in certain contexts.

The integration of comprehensive annotation resources like GENCODE with TPM-based selection methodologies represents a significant advancement in reference gene identification. This approach moves beyond the limitations of traditional housekeeping genes by providing a data-driven, condition-specific framework for normalization that enhances the accuracy and reliability of gene expression studies. As transcriptomic technologies continue to evolve, the synergy between high-quality genome annotations and empirical stability metrics will remain fundamental to valid biological interpretation in functional genomics research.

Accurate gene expression analysis via reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) is a cornerstone of modern molecular biology, drug discovery, and biomedical research. A critical, yet often overlooked, prerequisite for obtaining reliable results is the use of stably expressed reference genes for data normalization. The selection of inappropriate reference genes, a common pitfall, can lead to inaccurate data and misleading biological interpretations [26] [27]. Traditional housekeeping genes, such as GAPDH and β-actin, are not universally stable and their expression can vary significantly across different tissues, developmental stages, or experimental conditions [26] [28].

The advent of high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) provides a powerful foundation for the systematic and unbiased selection of candidate reference genes. This protocol details a robust pipeline for leveraging transcriptome data to identify and validate the most stable reference genes for RT-qPCR studies, framed within the broader context of selecting reference genes using TPM (Transcripts Per Million) values. This methodology ensures that normalization standards are tailored to specific experimental conditions, thereby enhancing the accuracy and reproducibility of gene expression analyses [17] [29] [30].

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive pipeline for systematic reference gene selection, from transcriptome analysis to experimental validation.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential materials and reagents for the reference gene selection pipeline.

| Item | Function/Description | Examples/Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality, intact total RNA from samples. | TRIzol Reagent [29] [28] or equivalent. RNA integrity is critical for both RNA-seq and RT-qPCR. |

| cDNA Synthesis Kit | Reverse transcription of RNA into stable cDNA for qPCR amplification. | Kits containing reverse transcriptase, primers (oligo(dT) and/or random hexamers) [29] [31]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Sensitive and specific detection of amplified cDNA during RT-qPCR. | SYBR Green-based mixes [29] [7] are common for gene expression analysis. |

| Gene-Specific Primers | Amplification of candidate and target genes with high efficiency and specificity. | Primers designed with tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST [29]; amplification efficiency (E) of 90–110% is ideal [7]. |

| Stability Analysis Software | Statistical evaluation of candidate gene expression stability from RT-qPCR data (Cq values). | geNorm [31] [28], NormFinder [31] [27], BestKeeper [28], and RefFinder [17] [31]. |

Computational Selection Protocol

Step 1: RNA-seq Data Processing and TPM Calculation

Begin with high-quality RNA-seq data from samples representing all experimental conditions of your study (e.g., different tissues, treatments, developmental stages). Raw sequencing reads must be processed through a standard bioinformatics pipeline, which includes quality control, adapter trimming, and alignment to a reference genome. Following alignment, calculate gene expression values.

For reference gene selection, TPM is the recommended unit over RPKM/FPKM. TPM normalizes for both sequencing depth and gene length, and its values sum to a constant (one million) across samples, allowing for more direct comparison of the relative abundance of a transcript between different samples [19] [30].

The formula for TPM is: [ TPM = \frac{\frac{Reads\ Mapped\ to\ Transcript}{Transcript\ Length (kb)}}{\sum \left( \frac{Reads\ Mapped\ to\ Transcript}{Transcript\ Length (kb)} \right)} \times 10^6 ] Where the denominator is the sum of all length-normalized read counts in the sample [19].

Step 2: Application of TPM-Based Stability Filters

With TPM values for all genes across all samples, the next step is to filter for genes with high and stable expression. Tools like GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) software can automate this process [30]. The standard filtering criteria, applied to the logâ‚‚(TPM) values, are summarized below.

Table 2: Standard TPM-based filtering criteria for selecting stable candidate reference genes [30].

| Filter Criteria | Mathematical Representation | Rationale | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universal Expression | (TPMáµ¢) > 0 for all samples (i) | Ensures the gene is expressed in every condition. | |

| Low Variability | σ(log₂(TPMᵢ)) < 1 | Selects genes with minimal fluctuation in expression across samples. | |

| No Exceptional Outliers | |logâ‚‚(TPMáµ¢) - Mean(logâ‚‚(TPM))\ | < 2 | Removes genes with extreme expression in any single sample. |

| High Expression Level | Mean(logâ‚‚(TPM)) > 5 | Ensures the gene is expressed at a level easily detectable by RT-qPCR. | |

| Low Coefficient of Variation | σ(log₂(TPMᵢ)) / Mean(log₂(TPM)) < 0.2 | Combines stability and expression level into a single robust metric. |

After applying these stringent filters, the resulting shortlist of candidate genes should be taken forward for experimental validation. The number of candidates can vary, but studies often select around 10-12 genes for downstream testing [29] [7].

Experimental Validation Protocol

Step 3: RT-qPCR Experimental Setup

- cDNA Synthesis: Synthesize cDNA from the same RNA samples used for RNA-seq, or from a new, independent biological replicate set. Use a high-quality reverse transcription kit.

- Primer Design and Validation: Design primers for each candidate gene that are exon-spanning (to avoid genomic DNA amplification) and have an amplicon length of 80-200 bp. Validate primer specificity by checking for a single peak in the melt curve and a single band of the expected size on an agarose gel. Determine primer amplification efficiency (E) using a standard curve of serial cDNA dilutions; E between 90% and 110% with a correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.980 is acceptable [29] [7].

- qPCR Run: Perform RT-qPCR reactions for all candidate genes across all cDNA samples. Include technical replicates (at least duplicates) for each biological replicate.

Step 4: Stability Analysis and Final Selection

Compile the quantification cycle (Cq) values from the RT-qPCR runs. The stability of the candidate genes is then evaluated using multiple algorithms, as each assesses stability from a slightly different perspective [17] [31]. The combined use of these tools provides a comprehensive assessment.

Table 3: Key algorithms for evaluating reference gene stability from RT-qPCR Cq values.

| Algorithm | Primary Metric | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| geNorm | M-value (Average pairwise variation) | Ranks genes by stability (lower M-value is better). Also determines the optimal number of reference genes (Vn/Vn+1 < 0.15) [31] [30]. |

| NormFinder | Stability Value (Intra- and inter-group variation) | Estimates expression variation both within and between sample groups, which is valuable for structured experiments [31] [27]. |

| BestKeeper | Standard Deviation (SD) & Coefficient of Variation (CV) of Cq | Uses raw Cq values; genes with SD < 1 are considered stable [28]. |

| RefFinder | Comprehensive Ranking (Geometric mean) | Integrates results from geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the comparative ΔCq method to generate a overall final ranking [17] [31]. |

Finally, use a web-based tool like EndoGeneAnalyzer to streamline this analytical process. This tool can assist in identifying and removing outliers from the Cq data and provides a user-friendly interface for performing stability analysis and subsequent differential expression analysis of target genes [27].

Application Examples

This pipeline has been successfully applied across diverse species and experimental conditions, demonstrating that optimal reference genes are highly context-dependent.

Table 4: Examples of optimal reference genes identified through transcriptome-based pipelines.

| Species | Experimental Condition | Identified Optimal Reference Genes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humpback Grouper (Cromileptes altivelis) | Various tissues; Salinity stress; Bacterial infection | RPL35 & EEF1G (tissues); RPLP1, FH & METAP2 (salinity stress); RPSA, RPL25A & GNB211 (infection) [17] | [17] |

| Crimson Snapper (Lutjanus erythropterus) | Various tissues; Developmental stages; Astaxanthin treatment | RAB10 & PFDN2 (tissues & treatment); NDUFS7 & MRPL17 (developmental stages) [29] | [29] |

| Abelmoschus Manihot | Different tissues and flowering stages | eIF & PP2A1 (most stable); TUA (least stable) [7] | [7] |

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Developing plant organs | Ref 2 (ADP-ribosylation factor) & Ta3006 [31] | [31] |

The pipeline described herein—from RNA-seq data filtering with TPM-based criteria to multi-algorithm validation of candidate genes via RT-qPCR—establishes a rigorous and systematic approach for selecting reference genes. Moving beyond the potentially flawed use of classic housekeeping genes, this method ensures that normalization standards are empirically derived and specifically tailored to the experimental system at hand. By adopting this robust workflow, researchers in drug development and basic science can significantly enhance the accuracy, reliability, and reproducibility of their gene expression analyses.

A Step-by-Step Workflow: Selecting Candidate Reference Genes from Your TPM Data

The selection of optimal reference genes is a critical step in validating transcriptomic data from RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). Transcripts Per Million (TPM) has emerged as a superior unit of measurement for this purpose, as it provides a normalized expression value that accounts for both sequencing depth and gene length [19] [10]. Unlike raw read counts, TPM values allow for a more reliable initial assessment of gene expression stability across different samples and experimental conditions [30] [32]. Proper compilation and formatting of TPM values from RNA-seq libraries establishes the essential foundation for identifying stably expressed reference genes, which are crucial for downstream validation techniques like RT-qPCR [30].

The primary advantage of TPM over other normalization methods like RPKM or FPKM lies in its order of operations and mathematical properties. With TPM, the sum of all normalized expressions in a sample is constant (one million), enabling direct comparison of the proportion of reads that mapped to a gene across different samples [19] [10]. This characteristic is particularly valuable when selecting reference genes, as it ensures that expression stability assessments are not confounded by technical variations between libraries.

Understanding TPM Calculation

Mathematical Foundation

The calculation of TPM values involves a specific two-step process that differs from other normalization methods. Understanding this calculation is essential for proper interpretation and application in reference gene selection.

Step 1: Normalize for Gene Length

Step 2: Normalize for Sequencing Depth

- Sum all RPK values in the sample and divide this number by 1,000,000 to obtain a "per million" scaling factor.

- Divide each gene's RPK value by this scaling factor to obtain TPM [19].

The formula for TPM calculation is:

[ TPMi = \frac{\frac{\text{Reads}i}{\text{Length}i (\text{kb})}}{\sum{j=1}^n \frac{\text{Reads}j}{\text{Length}j (\text{kb})}} \times 10^6 ]

This process ensures that TPM values represent the relative abundance of a transcript in the population of one million transcripts, making them directly comparable between genes within the same sample [19] [10].

Comparison with Other Normalization Methods

Table 1: Comparison of RNA-seq Expression Quantification Measures

| Measure | Full Name | Normalization Order | Primary Use Case | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million | Length → Sequencing Depth | Within-sample comparison; Reference gene selection | Not ideal for direct cross-sample DE analysis |

| RPKM/FPKM | Reads/Fragments Per Kilobase per Million | Sequencing Depth → Length | Within-sample comparison (single-end/paired-end) | Sum of normalized reads varies between samples |

| Normalized Counts | - | Advanced statistical methods (e.g., TMM, RLE) | Cross-sample comparison; Differential expression | Requires specialized statistical packages |

Compiling TPM Values from RNA-seq Libraries

TPM values can be obtained through multiple computational approaches depending on the RNA-seq analysis pipeline employed:

Pseudoalignment Tools: Modern tools like Salmon and kallisto directly output TPM values through lightweight algorithms that avoid full sequence alignment [16] [33]. These are currently preferred for their speed and accuracy.

Alignment-Based Workflows: Traditional pipelines involving alignment with tools like STAR or TopHat2 followed by transcript quantification with RSEM also generate TPM values [32]. These approaches provide alignment information but require more computational resources.

Public Data Repositories: When working with publicly available RNA-seq data, TPM values may be directly downloadable from databases like the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) or institutional repositories like the NCI Patient-Derived Models Repository (PDMR) [16].

Formatting and Quality Control

Proper formatting of TPM data is essential for subsequent analysis in reference gene selection:

Data Structure: Compile TPM values into a matrix with genes as rows and samples as columns. This format is ideal for stability analysis and visualization.

Quality Assessment: Before proceeding with reference gene selection, perform quality checks including:

- Ensuring no zero or negative values are present

- Verifying that all samples have similar distributions of TPM values

- Checking for outliers or anomalous patterns that may indicate technical artifacts

Data Transformation: For stability analysis, TPM values are typically log2-transformed to better meet the assumptions of statistical tests and to reduce the influence of extreme values [30].

Application to Reference Gene Selection

Selection Criteria for Reference Candidates

The GSV software implements a systematic filtering approach to identify optimal reference genes from TPM data, based on adapted criteria from Li et al. [30]. The following criteria should be applied when selecting reference candidates:

Table 2: Criteria for Selecting Reference Genes from TPM Data

| Criterion | Mathematical Representation | Rationale | Recommended Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitous Expression | ( (TPMi){i=a}^{n} > 0 ) | Ensures detection across all conditions | Expression > 0 in all samples |

| Low Variability | ( \sigma(log2(TPMi)_{i=a}^{n}) < 1 ) | Filters genes with high expression fluctuation | Standard deviation of log2(TPM) < 1 |

| Consistent Expression | ( |log2(TPMi){i=a}^{n} - \overline{log2TPM} | < 2 ) | Removes genes with outlier expression | No expression > 2x from mean in any sample |

| High Expression | ( \overline{log_2TPM} > 5 ) | Ensures easy detection by RT-qPCR | Average log2(TPM) > 5 |

| Low Coefficient of Variation | ( \frac{\sigma(log2(TPMi){i=a}^{n})}{\overline{log2TPM}} < 0.2 ) | Additional stability measure | CV < 0.2 |

Experimental Workflow for Reference Gene Validation

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from RNA-seq data to validated reference genes:

Case Study: Successful Application in Microbial Research

A study on Clostridium beijerinckii demonstrates the practical application of TPM-based reference gene selection. Researchers initially identified 160 genes with stable expression from RNA-seq data, then applied filtering criteria including mean TPM > 35 and coefficient of variation of TPM < 30% [32]. From these candidates, seven genes were selected for experimental validation by RT-qPCR. Statistical analysis ultimately identified zmp and greA as the most stable reference genes, highlighting how TPM-based preselection efficiently narrows candidates for costly experimental validation [32].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for TPM-Based Reference Gene Selection

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq Quantification | Salmon, kallisto, RSEM | Generate TPM values from raw sequencing data |

| Data Analysis | GSV Software, Python Pandas, R/Bioconductor | Compile, format, and filter TPM matrices |

| Stability Assessment | NormFinder, GeNorm, RefFinder | Statistical validation of candidate reference genes |

| Experimental Validation | RT-qPCR reagents, specific primers | Confirm expression stability of candidate genes |

| Quality Control | FastQC, MultiQC | Assess RNA-seq data quality before TPM calculation |

Critical Considerations and Limitations

While TPM values provide an excellent starting point for reference gene selection, several important limitations must be considered:

Protocol-Dependent Comparisons: TPM values are not directly comparable between samples processed with different library preparation protocols (e.g., polyA-selection vs. ribosomal RNA depletion) [10]. The same biological sample prepared with different protocols will show different TPM distributions due to changes in the underlying RNA repertoire.

Appropriate Use Cases: TPM is ideal for within-sample comparisons and initial reference gene screening, but not recommended as direct input for differential expression analysis without additional normalization [16] [33]. Methods like DESeq2 or edgeR that use raw counts with between-sample normalization are more appropriate for identifying differentially expressed genes.

Threshold Adjustments: The filtering thresholds proposed should be considered starting points. Optimal cutoffs may vary depending on specific experimental systems and sequencing depths. The GSV software allows tuning of cutoff values to adapt to different data characteristics [30].

Proper compilation and formatting of TPM values from RNA-seq libraries establishes the critical foundation for robust reference gene selection. The systematic approach outlined here—from TPM calculation through progressive filtering to experimental validation—provides a reliable methodology for identifying stable reference genes specific to biological contexts. This TPM-based strategy addresses the significant limitation of using traditional housekeeping genes without empirical validation, ultimately enhancing the reliability of gene expression studies in diverse research applications.

In transcriptomic research, the accuracy of gene expression quantification via quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) is fundamentally dependent on reliable normalization using stably expressed reference genes [17] [34]. The advent of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized the process of reference gene discovery by enabling a high-throughput, unbiased screening of the entire transcriptome, moving beyond traditionally used housekeeping genes whose expression can vary considerably across experimental conditions [17] [35]. This protocol details a robust methodology for establishing selection criteria to identify optimal reference genes from RNA-seq data, specifically utilizing Transcripts Per Million (TPM) values to filter candidates based on expression level and stability. The procedure is framed within a broader thesis that advocates for a condition-specific and systematic approach to reference gene selection, which is critical for obtaining biologically meaningful qRT-PCR results in fields ranging from aquaculture and agriculture to biomedical research and drug development [17] [34] [8].

Core Filtering Criteria from RNA-seq TPM Data

The following criteria, when applied to TPM values from RNA-seq data, enable the systematic identification of candidate reference genes with high, stable expression. These metrics should be calculated across all samples in the experimental set.

Table 1: Core Quantitative Filters for Candidate Reference Gene Selection

| Criterion | Calculation | Recommended Threshold | Biological & Statistical Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Expression Level | Mean log2(TPM) across all samples. | log2(TPM) ≥ 6 [34] | Ensures sufficient expression for reliable detection in qRT-PCR, minimizing technical variation from low-abundance transcripts. |

| Expression Stability (Coefficient of Variation) | (Standard Deviation of log2(TPM) / Mean of log2(TPM)) * 100 | CV < 10% [34] [8] | Quantifies expression consistency; a low CV indicates minimal fluctuation across different samples or conditions. |

| Absolute Expression Cutoff | Mean TPM across all samples. | TPM ≥ 100 [8] | Provides a straightforward, non-logarithmic filter for moderate to high expression, complementing the log2(TPM) filter. |

These filters work in concert to narrow the vast transcriptome down to a manageable number of high-quality candidates. For instance, a study on Macrobrachium rosenbergii applied similar criteria to 43,155 genes, sequentially identifying 7,598 (17.61%) with high expression, and finally only 328 (0.76%) that met all stability and expression thresholds [34]. This rigorous filtering forms the foundation for a reliable shortlist of candidate genes before further stability analysis.

Experimental Protocol for Identification and Validation

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step workflow for processing RNA-seq data to identify and validate candidate reference genes.

RNA-seq Data Processing and TPM Calculation

The initial phase involves transforming raw sequencing data into normalized gene expression values.

- Raw Data Acquisition and Quality Control (QC): Begin with FASTQ files from sequencing. Perform quality control using tools like FastQC to assess read quality, adapter contamination, and GC content. Low-quality bases and adapters must be trimmed using software such as Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [36] [37].

- Read Alignment: Map the quality-filtered reads to the appropriate reference genome using a splice-aware aligner such as HISAT2 or STAR [37]. The output will be in BAM/SAM format.

- Gene Quantification: Count the number of reads aligning to each gene feature using software like featureCounts or HTSeq [38] [37]. This generates a raw count matrix for all genes across all samples.

- Normalization to TPM: Convert raw counts to TPM values. This normalization accounts for both gene length and sequencing depth, allowing for cross-sample comparison [34] [8]. The formula for TPM is:

- Reads Per Kilobase per Million (RPKM) or Fragments Per Kilobase per Million (FPKM): First, calculate RPKM/FPKM:

(gene read count / (gene length in kb * total million mapped reads)). - TPM: Then, calculate TPM:

(RPKM of a gene / sum of all RPKM values in the sample) * 1,000,000[35].

- Reads Per Kilobase per Million (RPKM) or Fragments Per Kilobase per Million (FPKM): First, calculate RPKM/FPKM:

Application of Stability and Expression Filters

Using the TPM matrix, apply the criteria defined in Table 1 to screen for candidate genes.

- Data Transformation: Calculate log2(TPM+1) for each gene in each sample to stabilize variance.

- Calculate Metrics: For every gene, compute:

- The mean of log2(TPM) across all samples.

- The standard deviation of log2(TPM) across all samples.

- The Coefficient of Variation (CV):

(Standard Deviation / Mean) * 100.

- Apply Filters: Filter the gene list to retain only those genes that meet all three thresholds simultaneously:

- Mean log2(TPM) ≥ 6

- CV of log2(TPM) < 10%

- Mean TPM ≥ 100

- Generate Candidate List: The resulting list of genes represents high-quality candidates for reference genes based on transcriptome-wide stability [34] [8].

Multi-Algorithm Stability Validation for qRT-PCR

The final phase involves experimental validation of the shortlisted candidates using qRT-PCR.

- Primer Design and QC: Design highly specific primers with an efficiency between 90-110%. Test primers to ensure a single amplicon is produced.

- cDNA Synthesis and qRT-PCR: Convert high-quality total RNA (RIN > 7.0) from all experimental conditions into cDNA [38]. Perform qRT-PCR in technical replicates for all candidate genes across all biological samples.

- Stability Analysis with Multiple Algorithms: Analyze the resulting Cq (Quantification Cycle) values using dedicated algorithms to rank the candidates by stability [17] [34] [8]:

- geNorm: Calculates a stability measure (M); lower M values indicate greater stability. It also determines the optimal number of reference genes by pairwise variation (V) [34].

- NormFinder: Uses a model-based approach to estimate intra- and inter-group variation, providing a stability value [36].

- BestKeeper: Relies on the standard deviation and coefficient of variance of the Cq values to assess stability [34].

- Comparative ΔCt Method: Evaluates stability by comparing pairwise variations between genes [34].

- Comprehensive Ranking: Use a web tool like RefFinder to integrate the results from all four methods above and generate a comprehensive final ranking of the candidate genes [17] [34].

- Final Selection and Functional Validation: Select the top-ranked genes for your specific experimental condition. Validate the selected genes by normalizing a known stress-responsive gene (e.g., a peroxidase gene) and confirming that the normalized expression profile aligns with expected biological responses [8].

Diagram 1: Workflow for selecting and validating reference genes from RNA-seq data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of this protocol requires specific reagents, software tools, and computational resources. The following table details the essential components.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reference Gene Selection

| Category | Item / Software | Specific Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Plant/Fish/Animal Total RNA Kit (e.g., Omega Bio-tek) | High-quality total RNA isolation from tissues. |

| PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara) | Genomic DNA removal and first-strand cDNA synthesis. | |

| SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix | Fluorescence-based detection of amplified DNA in qRT-PCR. | |

| Bioinformatics Software | FastQC, Trimmomatic | Initial quality control and adapter trimming of raw sequencing reads. |

| HISAT2, STAR | Alignment of sequencing reads to a reference genome. | |

| featureCounts, HTSeq | Quantification of reads mapped to genomic features (genes). | |

| R/Bioconductor with DESeq2, edgeR | Statistical environment for data transformation, filtering, and CV calculation. | |

| Stability Analysis Tools | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper | Individual algorithms for assessing reference gene stability from Cq values. |

| RefFinder | Web tool for aggregating results from multiple algorithms into a consensus ranking. | |

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster or Cloud Instance | Resource-intensive processing of RNA-seq data (alignment, quantification). |

| Ot-551 | Ot-551, CAS:627085-11-4, MF:C13H23NO3, MW:241.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |