A Step-by-Step Guide to Molecular Docking for Drug Discovery in 2025: From Foundations to AI-Driven Applications

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive, step-by-step framework for performing biologically relevant and reproducible molecular docking.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Molecular Docking for Drug Discovery in 2025: From Foundations to AI-Driven Applications

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive, step-by-step framework for performing biologically relevant and reproducible molecular docking. Covering foundational principles, advanced methodological workflows, critical troubleshooting, and rigorous validation strategies, it integrates the latest 2025 advancements in deep learning and AI. Readers will learn to navigate diverse docking tasks—from flexible re-docking to challenging apo-docking—employ robust controls to enhance success rates, and leverage transformative tools like diffusion models and neural network potentials to accelerate structure-based drug discovery.

Understanding Molecular Docking: Core Concepts and Its Evolving Role in Modern Drug Discovery

Molecular docking is a fundamental computational technique in structure-based drug discovery that predicts the binding affinity and three-dimensional conformation of a small molecule (ligand) within a target protein's binding site [1]. This method enables researchers to study the behavior of small molecules, such as drug candidates or nutraceuticals, at the atomic level and understand the fundamental biochemical processes underlying these interactions [1]. By simulating how a ligand binds to its target, docking serves as a powerful tool for hit identification, lead optimization, and understanding molecular recognition processes in biological systems [2].

The primary objectives of molecular docking are twofold: (1) to predict the binding affinity and conformation of small molecules within a receptor site, and (2) to identify hits from large chemical databases to search for diverse chemical scaffolds [2]. These objectives, while classified separately, have boundaries that are not clearly demarcated in practice [2].

Key Objectives and Methodological Framework

Core Objectives of Molecular Docking

Molecular docking aims to address several critical questions in drug-target interactions:

- Pose Prediction: Determining the precise orientation and conformation (the "binding pose") of a ligand when bound to its target protein.

- Affinity Estimation: Quantifying the strength of interaction through scoring functions that approximate binding energy.

- Hit Identification: Screening vast chemical libraries to identify promising candidates for further experimental validation.

- Mechanistic Insight: Elucidating molecular interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, electrostatic interactions) that stabilize the complex.

Fundamental Methodological Components

To achieve these objectives, molecular docking programs comprise two essential components [2]:

- Search Algorithm: Explores the conformational space of the ligand within the binding site.

- Scoring Function: Ranks the generated conformations to identify biologically relevant poses.

Table 1: Molecular Docking Objectives and Applications in Drug Discovery

| Primary Objective | Methodological Approach | Application in Drug Discovery | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Conformation Prediction | Sampling ligand conformational space within binding site using systematic or stochastic algorithms [2] | Understanding ligand-receptor interaction mechanisms; guiding structure-based drug design [1] | Identification of optimal binding pose and molecular interactions |

| Binding Affinity Prediction | Scoring and ranking poses using force-field, empirical, knowledge-based, or consensus functions [2] | Virtual screening of compound libraries; lead optimization through affinity comparison [2] [1] | Quantitative estimate of binding strength; prioritization of candidate compounds |

| Hit Identification | High-throughput docking of thousands to millions of compounds from digital libraries [2] | Early-stage drug discovery to identify novel chemical scaffolds against a target [2] | Shortlist of potential hits for experimental validation |

| Target Identification for Nutraceuticals | Docking bioactive food-derived compounds against disease-relevant protein targets [1] | Uncovering therapeutic mechanisms of nutraceuticals; supporting drug repurposing [1] | Hypothesis generation for molecular targets of natural products |

Technical Protocols and Workflows

Molecular Docking Workflow

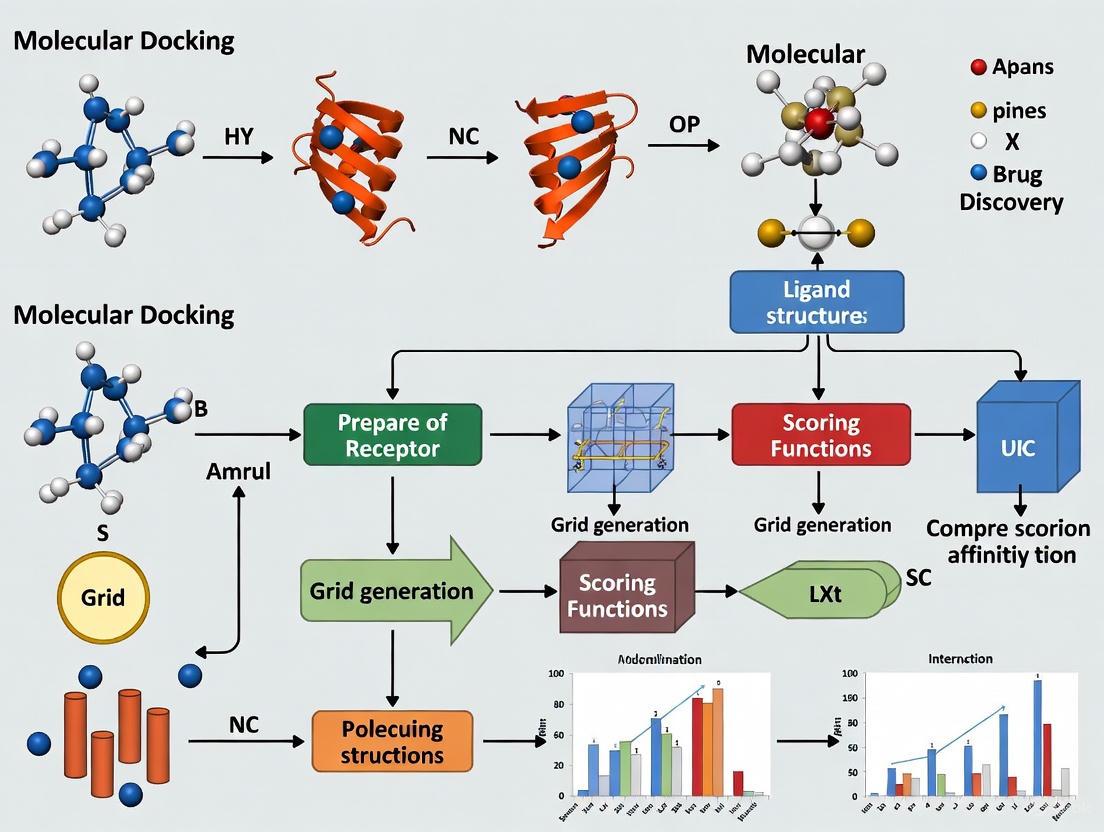

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for a molecular docking experiment, from target preparation to result validation:

Conformational Search Algorithms

Docking programs employ various search algorithms to explore possible ligand conformations, broadly classified into systematic and stochastic methods [2]:

Systematic Methods

- Systematic Search: Rotates all possible rotatable bonds by fixed intervals to exhaustively explore conformations, though complexity increases exponentially with rotatable bonds [2]. Used by Glide and FRED.

- Incremental Construction: Fragments molecules into rigid components, docks them into appropriate sub-pockets, then builds linkers systematically [2]. Implemented in FlexX and DOCK.

Stochastic Methods

- Monte Carlo: Makes random changes to rotatable bonds, accepting/rejecting based on energy criteria and Boltzmann distribution [2]. Used by MCDock and ICM.

- Genetic Algorithm (GA): Encodes conformational degrees of freedom as binary strings, applies mutation and crossover operations guided by fitness (score) [2]. Implemented in AutoDock and GOLD.

Table 2: Comparison of Molecular Docking Search Algorithms

| Algorithm Type | Representative Software | Key Principles | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic Search | Glide [2], FRED [2] | Exhaustive rotation of rotatable bonds by fixed increments | Comprehensive exploration; deterministic results | Computational cost grows exponentially with ligand flexibility |

| Incremental Construction | FlexX [2], DOCK [3] | Fragmentation of ligand; docking rigid fragments then connecting linkers | Reduced complexity; efficient for flexible ligands | Performance depends on fragmentation scheme and anchor placement |

| Monte Carlo | MCDock [2], ICM [2] | Random conformational changes with Metropolis criterion for acceptance | Effective escape from local minima; good for rough energy landscapes | May require many iterations; stochastic nature requires multiple runs |

| Genetic Algorithm | AutoDock [4], GOLD [5] | Population-based optimization using selection, crossover, and mutation | Global optimization; robust for complex search spaces | Parameter tuning sensitive; computationally intensive for large populations |

Scoring Functions

Scoring functions evaluate and rank generated poses by estimating binding affinity, typically falling into four categories [2]:

- Force Field-Based: Sums non-bonded interactions (van der Waals, electrostatics) using molecular mechanics equations.

- Empirical: Uses weighted energy terms (H-bonds, hydrophobic contacts) derived from regression on complexes with known affinity.

- Knowledge-Based: Statistical potentials derived from atom pair frequencies in known protein-ligand structures.

- Consensus: Combines multiple scoring functions to improve reliability and reduce individual method biases.

Advanced Applications and Integrations

Integration with Molecular Dynamics

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations complement docking by addressing a key limitation: the typical treatment of receptors as rigid bodies [2]. MD can be used in two ways:

- Pre-docking: To sample various receptor conformations for ensemble docking.

- Post-docking: To refine docked complexes and incorporate induced fit effects [2].

AI-Enhanced Docking Approaches

Recent advances incorporate machine learning to improve both conformational sampling and scoring:

- Geometric Deep Learning: Models like IGModel use graph neural networks to incorporate spatial features of interacting atoms [2].

- Network-Based Sampling: AI-Bind combines network science with unsupervised learning to predict protein-ligand interactions [2].

- Improved Scoring Functions: AI techniques help develop more generalized scoring functions that better predict binding affinities across diverse targets [2].

Application in Nutraceutical Research

Molecular docking has seen growing application in identifying molecular targets of nutraceuticals—bioactive compounds from food sources—for disease management [1]. This approach helps authenticate their therapeutic benefits by predicting interactions with disease-relevant protein targets in models including cancer, cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and metabolic disorders [1].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Resources for Molecular Docking Experiments

| Research Reagent / Software | Type / Category | Primary Function in Docking Workflow | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina [6] [1] | Docking Software | Binding pose prediction and affinity estimation | Open-source; efficient gradient-optimization algorithm; good accuracy/speed balance |

| Glide [6] [1] | Docking Software | High-throughput virtual screening and precision docking | Systematic search and Monte Carlo methods; hierarchical scoring filters |

| GOLD [1] | Docking Software | Genetic algorithm-based docking for pose prediction | Genetic algorithm optimization; handles protein flexibility |

| DOCK [1] | Docking Software | Shape-based matching and scoring of ligands | One of the earliest docking programs; grid-based scoring |

| AlphaFold2 DB [2] | Protein Structure Database | Source of predicted protein structures for targets lacking experimental structures | AI-predicted protein structures; expands range of dockable targets |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Experimental Structure Database | Source of experimentally determined 3D structures of biological macromolecules | High-quality structures often with co-crystallized ligands |

| ZINC20 | Compound Library | Database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening | Millions of purchasable compounds in ready-to-dock formats |

Validation and Best Practices

Experimental Validation Protocol

While molecular docking provides valuable predictions, experimental validation remains essential:

In Vitro Binding Assays:

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) to measure binding kinetics (KA, KD)

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) to determine thermodynamic parameters

- Fluorescence Polarization assays for competitive binding studies

Functional Assays:

- Enzyme inhibition assays to confirm pharmacological activity

- Cell-based reporter assays for functional characterization

- Antibacterial/antiproliferative activity testing in relevant cell lines

Structural Validation:

- X-ray crystallography of protein-ligand complexes to verify predicted binding modes

- NMR spectroscopy to study solution-state interactions

Reproducibility Guidelines

To ensure biologically relevant and reproducible docking results [2]:

- Thoroughly understand the drug target's biology and binding site characteristics

- Validate docking protocols by reproducing known ligand poses (RMSD ≤ 2.0 Å)

- Use multiple scoring functions to cross-validate results

- Report all parameters and software versions explicitly

- Avoid over-interpreting docking scores as precise affinity measurements

- Acknowledge limitations regarding protein flexibility and solvation effects

Signaling Pathways in Drug-Target Interactions

The diagram below illustrates the relationship between molecular docking predictions and downstream cellular effects through signaling pathways:

Molecular docking serves as the critical computational bridge between compound screening and understanding therapeutic mechanisms at the molecular level. When properly implemented with attention to methodological details and validation requirements, it significantly accelerates drug discovery pipelines and provides fundamental insights into biomolecular interactions.

Molecular docking is a cornerstone computational technique in modern drug discovery, functioning as a predictive "handshake" between a small molecule (ligand) and a target protein [7]. Its primary objective is to forecast the three-dimensional orientation of a ligand within a protein's binding site and estimate the strength of their interaction, known as binding affinity [7]. By enabling researchers to rapidly evaluate how thousands to billions of compounds might interact with a disease target, docking serves as a powerful virtual screening tool that prioritizes the most promising candidates for costly and time-consuming laboratory experiments, thereby saving millions of dollars in research costs [7] [8].

The fundamental workflow adheres to a search-and-score paradigm: it involves searching the vast conformational and orientational space of the ligand relative to the protein and then scoring each generated "pose" to identify the most likely binding mode [9]. While early docking methods treated proteins as rigid bodies, advancements in computing and algorithms now allow for varying degrees of flexibility in both the ligand and the protein, leading to more accurate predictions of biomolecular interactions [9].

The Molecular Docking Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

The process of molecular docking can be systematically broken down into four key stages, from initial data preparation to the final analysis of results. The following diagram provides a high-level overview of this integrated workflow.

Stage 1: Target and Ligand Preparation

The foundation of a successful docking experiment lies in the careful preparation of both the protein target and the ligand molecules.

Target Preparation

The process typically begins by acquiring a three-dimensional structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [7] [10]. For instance, a study targeting VEGFR-2 and c-Met selected multiple co-crystal structures from the PDB based on criteria such as high resolution (e.g., less than 2 Ã…) and biological activity [10]. The protein structure then undergoes a series of critical preparation steps using software like Discovery Studio or Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) [10] [11]:

- Removal of Extraneous Molecules: Water molecules, ions, and other heteroatoms not involved in binding are typically removed, unless they are known to be crucial for ligand interaction [7] [10].

- Structural Completion: Missing amino acid residues or loops are added and optimized [10] [11].

- Addition of Hydrogen Atoms and Charges: Polar hydrogens are added, and atomic charges are assigned using force fields like CHARMM or AMBER [7] [10] [11].

- Energy Minimization: The structure is relaxed to a low-energy conformation to correct any steric clashes or strained geometries introduced during the preparation process [10] [11].

Ligand Preparation

Ligand structures can be sourced from chemical databases like PubChem or sketched using chemical drawing tools [7]. The preparation involves:

- Structure Optimization: Generating low-energy 3D conformations using tools like OpenEye's OMEGA [11].

- Protonation and Tautomer Assignment: Determining the dominant protonation states and tautomers at physiological pH (e.g., 7.4) using tools like QUACPAC [11].

- Assignment of Chemical Types and Charges: Defining atom types and calculating partial charges based on appropriate force fields [12].

Finally, both the prepared protein and ligand are converted into formats required by the docking software, such as the PDBQT format used by AutoDock Vina [7].

Stage 2: Docking Setup and Execution

This stage involves configuring the docking simulation to efficiently and effectively explore potential binding modes.

Defining the Binding Site and Search Space

The spatial region where the docking search will be conducted must be defined. This is often done by specifying a three-dimensional grid box centered on the known or predicted binding site. The box is defined by its center coordinates (center_x, center_y, center_z) and its dimensions (size_x, size_y, size_z) [7]. For example, a tutorial for AutoDock Vina might use a box with a center at (15.0, 12.5, 10.0) and a size of 25.0 Ã… in all dimensions [7]. In cases where the binding site is unknown, "blind docking" can be performed over a larger portion or the entire protein surface, a task where some deep learning models have shown promise [9].

Selecting a Docking Approach and Parameters

A critical choice is the treatment of molecular flexibility, which significantly impacts computational cost and accuracy.

- Rigid Docking: Treats both the protein and ligand as rigid. This is computationally efficient but oversimplifies the binding process [9].

- Flexible Ligand Docking: Allows the ligand's torsional bonds to rotate while keeping the protein rigid. This is the most common approach in traditional docking software like AutoDock Vina [7] [9].

- Flexible Protein and Ligand Docking: Allows for movement in both the ligand and the protein's side chains or even backbone. This is more computationally demanding but can better capture "induced fit" effects. Novel algorithms, such as those in the SOL-P program, are tackling this challenge by allowing the movement of selected protein atoms during the docking process [12].

The command to execute a docking simulation in AutoDock Vina, for instance, would incorporate all these parameters [7]:

Stage 3: Pose Scoring, Ranking, and Analysis

After the docking simulation generates a set of potential ligand poses, they must be evaluated and interpreted.

Scoring Functions

Scoring functions are mathematical models used to predict the binding affinity of each pose. They can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Force Field-Based: Calculate energies based on molecular mechanics terms (van der Waals, electrostatic, etc.) [12].

- Empirical: Estimate affinity using weighted terms for different interaction types (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) derived from experimental data [8].

- Knowledge-Based: Use statistical potentials derived from known protein-ligand structures in databases like the PDB [8].

- Machine Learning-Based: Train models on structural and interaction data to predict binding affinity. These are increasingly popular and can be used to rescore poses generated by traditional methods for improved accuracy [9] [11].

Post-Processing and Validation

The top-ranked poses are typically subjected to further analysis:

- Pose Clustering: Similar poses are grouped to identify consensus binding modes and ensure the top result is not an outlier [8].

- Visual Inspection: The geometric and chemical complementarity of the top poses is visually assessed using molecular visualization tools like PyMOL or Chimera [7]. Researchers check for key interactions like hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, and hydrophobic contacts.

- Consensus Scoring: Using multiple scoring functions to rank poses can improve the reliability of the predictions [8].

- Energy Minimization: Some workflows include a final energy minimization step to relax the docked complex and remove any minor steric clashes [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Docking Software and Scoring Approaches

| Software | Scoring Function Type | Flexibility Handling | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina [7] | Empirical | Flexible ligand, rigid receptor | Standard virtual screening |

| DOCK [8] | Force field & Empirical | Flexible ligand, rigid receptor | Large-scale library docking |

| SOL-P [12] | Force Field (MMFF94) | Flexible ligand & movable protein atoms | High-accuracy pose prediction |

| Gnina [11] | Machine Learning (CNN) | Flexible ligand, rigid receptor | Pose prediction and rescoring |

| DiffDock [9] | Machine Learning (Diffusion) | Ligand flexibility, coarse protein flexibility | Blind pose prediction |

Advanced Considerations and Controls

For robust results, especially in large-scale virtual screening, implementing controls is essential.

- Enrichment Controls: Before screening a large, unknown library, it is good practice to dock a benchmark set containing known active and inactive compounds against the target to ensure the docking protocol can successfully enrich actives [8].

- Decoy Sets: Resources like the Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD-E) provide decoy molecules that are physically similar but chemically different to active compounds, which are useful for validating virtual screening workflows [10].

- Handling Protein Flexibility: For targets with significant conformational changes, advanced methods like ensemble docking (docking into multiple protein structures) or using deep learning models like FlexPose that explicitly model protein flexibility can be necessary for accurate predictions across diverse ligand sets [9].

- Integration with MD Simulations: To account for dynamic effects, top-ranking docked poses can be refined using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. This provides insights into the stability of the complex over time and allows for more rigorous calculation of binding free energies using methods like MM/PBSA [10].

Table 2: Key Software, Databases, and Resources for Molecular Docking

| Category | Item | Function and Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Tools | AutoDock Tools, AutoDock Vina [7] | Preparing molecules (PDBQT format) and performing flexible ligand docking. |

| PyMOL, Chimera [7] | Visualization of protein-ligand complexes and analysis of binding interactions. | |

| Discovery Studio (DS), MOE [10] | Integrated suites for protein preparation, pharmacophore modeling, and docking. | |

| AmberTools, GROMACS [10] [11] | Molecular dynamics simulations for refining docked poses and calculating binding free energies. | |

| Databases | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [7] [10] | Primary repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. |

| PubChem [7] | Database of small molecules and their biological activities. | |

| PDBBind [9] [11] | Curated database of protein-ligand complexes with binding affinity data for benchmarking. | |

| DUD-E [10] | Directory of Useful Decoys: Enhanced, used for virtual screening control experiments. | |

| ZINC, ChemDiv [10] [8] | Commercial databases of purchasable compounds for virtual screening. | |

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for large-scale virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulations. |

| Cloud Computing Platforms (e.g., AWS, GCP) | Provides scalable resources for computationally intensive docking tasks [8]. |

Molecular docking stands as a computational cornerstone in modern structure-based drug design, enabling researchers to predict how small molecule ligands interact with biological targets at the atomic level [13] [14]. The accuracy and purpose of these predictions vary significantly depending on the docking methodology employed. Within the drug discovery pipeline, distinct computational tasks—specifically re-docking, cross-docking, apo-docking, and blind docking—serve unique and critical functions, from validating computational methods to discovering novel binding sites [15]. These protocols range from controlled validation experiments to ambitious predictive challenges that account for full protein flexibility and unknown binding loci. Mastering the application, interpretation, and limitations of each docking task is therefore fundamental for researchers aiming to leverage computational docking effectively in rational drug design. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of these four key docking methodologies, complete with structured protocols, performance metrics, and practical implementation guidelines to equip scientists with the necessary knowledge to execute these tasks effectively within their research workflows.

Core Docking Tasks: Definitions and Applications

The table below summarizes the four fundamental docking tasks, their primary objectives, and typical applications in drug discovery research.

Table 1: Overview of Key Molecular Docking Tasks

| Docking Task | Primary Objective | Key Applications | Complexity Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Re-docking | Method validation by reproducing a known binding pose | Scoring function validation, Protocol optimization [16] | Low |

| Cross-docking | Assess predictive power across multiple related structures | Handling receptor flexibility, Benchmarking performance [17] [15] | Medium |

| Apo-docking | Predict ligand binding using an unbound receptor structure | Simulating true in silico prediction scenarios [17] [15] | High |

| Blind Docking | Identify novel binding sites without prior knowledge | Cryptic site discovery, Allosteric inhibitor identification [13] [14] | Very High |

Re-docking

Re-docking is the most fundamental docking task, serving as the initial validation step for any docking protocol. In this procedure, a ligand is separated from its receptor in a known, experimentally determined protein-ligand complex (a holo structure) and is then computationally re-docked back into the same binding site [16]. The central goal is to evaluate whether the docking algorithm and scoring function can faithfully reproduce the experimentally observed, native binding mode. Successful re-docking, typically defined as predicting a ligand pose with a Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) of less than 2.0 Ã… from the crystal structure pose, validates the basic setup of a docking study [18]. It is primarily used to benchmark scoring functions, optimize sampling parameters, and establish a baseline performance level before proceeding to more challenging predictive tasks like virtual screening [16].

Cross-docking

Cross-docking introduces a critical real-world challenge: receptor flexibility. This task involves docking a ligand into a receptor structure that was co-crystallized with a different ligand [17] [15]. The objective is to test the docking method's robustness to conformational variations in the binding site that occur in response to different bound ligands. These variations can include side-chain rearrangements, backbone shifts, and loop movements [15]. Cross-docking is considered a more rigorous test than re-docking because it assesses a method's ability to handle the structural differences between holo structures used in docking and the actual target receptor, which may not be in an identical conformational state. Performance in cross-docking is a strong indicator of how well a method will perform in prospective virtual screening campaigns where the true receptor conformation is unknown [15].

Apo-docking

Apo-docking represents a further step toward realistic prediction by attempting to dock a ligand into the unbound (apo) form of a receptor—a structure determined without any ligand present [17] [15]. This is highly challenging because proteins often undergo conformational changes, known as "induced fit," upon ligand binding [15] [14]. These changes can range from minor side-chain rotations to large-scale domain motions, making the apo binding site potentially very different from the holo site the ligand expects. The ability of a docking method to successfully perform apo-docking is a direct test of its capacity to model or accommodate receptor flexibility, a frontier challenge in the field [13] [15]. With the increasing availability of AlphaFold2-predicted structures, which often resemble apo states, developing methods competent at apo-docking has become increasingly important [17].

Blind Docking

Blind docking is the most ambitious of these tasks, performed when the location of the binding site is unknown a priori [13]. The entire surface of the receptor is screened to identify potential binding pockets and predict the ligand's binding mode simultaneously. This approach is crucial for discovering novel allosteric sites or "cryptic" pockets that are not apparent in the unbound structure but can open upon ligand binding [15] [14]. Given the enormous conformational space that must be searched, blind docking is computationally demanding and requires sophisticated algorithms to efficiently explore the protein surface. It is the primary method for initial investigation of proteins with unknown function or for seeking novel therapeutic sites outside well-characterized active sites [13].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The following section provides detailed, step-by-step protocols for executing each of the four key docking tasks. Adherence to these standardized workflows is essential for generating reliable, reproducible results in drug discovery applications.

Protocol for Re-docking and Cross-docking

Step 1: System Preparation

- Obtain the PDB file for the target protein-ligand complex.

- For re-docking: Use this complex's structure as both the receptor and the source of the native ligand.

- For cross-docking: Select a different complex where the same protein is bound to a different ligand. Use this protein structure as the receptor, while the ligand to be docked comes from the original complex.

- Prepare the protein by removing the original ligand, adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and correcting any protonation states of key residues (e.g., His, Asp, Glu) using software like UCSF Chimera, Schrodinger's Protein Preparation Wizard, or the

pdb4ambertool. - Prepare the ligand by generating 3D coordinates, optimizing its geometry, and defining its rotatable bonds. Tools like Open Babel, Corina, or the LigPrep module are suitable for this.

Step 2: Binding Site Definition

- For both re-docking and cross-docking, the binding site is known.

- Define the docking search space by creating a grid box centered on the crystallographic position of the native ligand.

- The box size should be large enough to accommodate full ligand flexibility; a common default is a 20 Å × 20 Å × 20 Å box.

Step 3: Docking Execution

- Run the docking simulation using software such as AutoDock Vina, Gnina, DOCK, or GOLD.

- Ensure the sampling parameters are sufficient; typically, the exhaustiveness in Vina should be set to 20-50 for reliable results.

Step 4: Pose Analysis and Validation

- Generate multiple ligand poses (e.g., 10-20).

- Calculate the RMSD between the top-ranked docked pose and the native crystallographic ligand pose.

- A successful docking is typically defined by an RMSD value below 2.0 Ã…, indicating the method could recapitulate the correct binding mode [18].

Protocol for Apo-docking

Step 1: Apo Structure Sourcing and Preparation

- Source the apo (unbound) protein structure from the PDB or use a predicted structure from AlphaFold2 [17].

- Prepare the protein structure as described in the previous protocol. Pay special attention to the potential for different protonation states and the positioning of flexible side chains in the absence of a ligand.

Step 2: Binding Site Identification and Preparation

- Identify the putative binding site. This can be done by:

- Structural alignment with a known holo structure of a homologous protein.

- Using cavity detection programs like GRID, POCKET, or SurfNet [13].

- If a co-crystallized ligand from a holo structure is available, using its location to define the grid.

- Define a grid box around this putative binding site.

Step 3: Flexible Docking Execution

- Execute the docking run. Given the potential for conformational differences between apo and holo forms, it is advisable to use docking software that can account for some level of protein flexibility, such as Gnina, AutoDock Vina, or GOLD.

- Consider using specialized flexible docking methods like those incorporating Local Move Monte Carlo (LMMC) or deep learning approaches like FABFlex that explicitly predict pocket changes [13] [17].

Step 4: Analysis and Holo Structure Comparison

- Analyze the top-ranked poses.

- Compare the predicted ligand pose with a known holo structure of the same protein (if available) to evaluate accuracy.

- Assess whether the predicted binding mode would be sterically and energetically feasible in the context of the known holo structure.

Protocol for Blind Docking

Step 1: Protein Structure Preparation

- Prepare the protein structure as in previous protocols, ensuring the entire surface is modeled correctly.

Step 2: Global Search Space Definition

- Define a very large grid box that encompasses a significant portion of the protein's surface or the entire protein.

- Alternatively, use a cavity detection algorithm to identify multiple potential binding pockets and perform sequential, focused docking runs into each identified site [13] [14].

Step 3: High-Throughput Docking Execution

- Run the docking simulation with a large search space. This is computationally intensive and may require high-performance computing resources.

- Increase sampling parameters (e.g., exhaustiveness in Vina to 100 or more) to ensure adequate coverage of the vast conformational space.

- Regression-based multi-task learning models like FABFlex can significantly accelerate this process by directly predicting binding structures without exhaustive sampling [17].

Step 4: Binding Site Identification and Ranking

- Cluster the output poses based on their 3D location on the protein surface.

- Rank the identified potential binding sites by the calculated score or energy of the docked poses.

- Manually inspect the top-ranked sites for chemical feasibility, presence of key interaction residues, and druggability.

Decision Workflow and Quantitative Benchmarks

Task Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate docking task based on the available structural information and research goals.

Diagram 1: A decision workflow for selecting the appropriate molecular docking task based on available structural data and research objectives.

Performance Metrics and Benchmarks

Understanding expected performance metrics is crucial for interpreting docking results. The table below summarizes typical accuracy benchmarks for successful outcomes in each docking task.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks for Docking Tasks

| Docking Task | Primary Metric | Success Threshold | Typical Success Rate | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Re-docking | Ligand Pose RMSD | < 2.0 Ã… [18] | 70-80% [18] | Scoring function bias |

| Cross-docking | Ligand Pose RMSD | < 2.0 Ã… | Varies widely with system | Receptor conformation mismatch [15] |

| Apo-docking | Ligand Pose RMSD | < 2.5 - 3.0 Ã… | Lower than cross-docking | Induced fit conformational changes [17] |

| Blind Docking | Site Identification & Pose RMSD | Correct site identified & pose < 3.0 Ã… | Highly method-dependent [13] | Massive search space, cryptic pockets [14] |

Advanced methods are pushing these benchmarks further. For instance, modern flexible docking tools like FABFlex have demonstrated the ability to increase the percentage of ligand RMSD below 2Ã… to 40.59% in blind flexible docking scenarios while also reducing pocket RMSD to 1.10Ã…, indicating accurate prediction of both ligand and protein pocket conformations [17]. Furthermore, such regression-based methods can achieve significant speed advantages, reportedly up to 208 times faster than state-of-the-art sampling-based flexible docking methods, making large-scale or high-throughput applications more feasible [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful execution of docking tasks relies on a suite of specialized software tools and computational resources. The following table catalogues the essential "research reagents" for the computational scientist.

Table 3: Essential Software and Resources for Molecular Docking Tasks

| Tool Category | Example Software/Resources | Primary Function | Relevant Docking Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Docking Suites | AutoDock Vina, Gnina [16], DOCK, GOLD | Ligand sampling and pose scoring | All tasks |

| Specialized Docking Tools | FABFlex [17], DynamicBind [17] | Flexible blind docking, Protein-ligand co-prediction | Apo-docking, Blind docking |

| Structure Preparation | UCSF Chimera, Open Babel, Schrodinger Suite | Protein and ligand cleanup, Hydrogen addition, Charge assignment | All tasks |

| Binding Site Detection | GRID, POCKET, SurfNet [13], Fpocket | Identify putative binding cavities | Blind docking, Apo-docking |

| Structure Databases | PDB (Protein Data Bank), AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Source experimental and predicted structures | Cross-docking, Apo-docking |

| Performance Analysis | RMSD calculation scripts, Visualization software | Validate poses, Analyze interactions | All tasks (esp. Re-docking) |

| H-Gamma-Glu-Gln-OH | H-Gamma-Glu-Gln-OH, CAS:10148-81-9, MF:C10H17N3O6, MW:275.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| m-PEG4-Boc | m-PEG4-Boc, MF:C14H28O6, MW:292.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Re-docking, cross-docking, apo-docking, and blind docking represent a hierarchy of computational tasks that address progressively more complex and realistic challenges in structure-based drug design [15]. While re-docking remains an essential first step for method validation, the field's frontier is defined by the challenges of protein flexibility and unknown binding sites, tackled by cross-docking, apo-docking, and blind docking [13] [14]. The ongoing integration of advanced machine learning methods, such as those seen in Gnina 1.3's CNN scoring functions and FABFlex's regression-based flexible docking, is steadily improving the accuracy and speed of these demanding tasks [17] [16]. By understanding the distinct purpose, protocol, and performance benchmarks for each docking task, researchers can more effectively design computational experiments, select appropriate tools, and critically interpret results, thereby accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents.

Molecular docking is a fundamental computational technique in modern drug discovery that predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule (a ligand) when bound to a larger biological receptor, typically a protein. The primary goal is to predict the binding pose and estimate the binding affinity through scoring functions, facilitating the identification and optimization of novel therapeutic compounds. This process involves an efficient conformational search to explore the vast space of possible ligand-receptor interactions. These core concepts form the foundation of structure-based drug design, enabling researchers to virtually screen vast chemical libraries, prioritize promising candidates for synthesis and testing, and understand structure-activity relationships at an atomic level, thereby accelerating the drug development pipeline and reducing associated costs.

Defining the Essential Terminology

Ligands and Receptors

In the context of molecular docking and drug discovery, the terms "ligand" and "receptor" describe the interacting partners.

- A Ligand is a molecule that binds to a larger macromolecule. In drug discovery, this typically refers to a small, drug-like molecule that binds specifically to a protein target. Ligands can include neurotransmitters, toxins, neuropeptides, steroid hormones, enzyme substrates, second messengers, or allosteric regulators [19]. The binding event is often reversible (transient and non-covalent) but can also be covalent and reversible or irreversible [19].

- A Receptor is the macromolecule, almost always a protein, that contains a region, known as a binding site, to which the ligand binds. A classic example is a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) like the β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR) [20]. The receptor's function is altered upon ligand binding, which is a key mechanism for cellular signal transduction [19]. For antimicrobial drug research, the target receptor is one that is proven essential for the growth, survival, or infectious capability of the pathogen [21].

Binding Sites and Poses

The interaction between a ligand and a receptor is localized to a specific region on the receptor.

- A Binding Site is a region on the macromolecule (e.g., a protein) that directly participates in its specific combination with another molecule [19]. Binding sites are characterized by their charge, spatial shape, and geometry, which selectively allow for high-specificity ligand binding [19]. There are different types of binding sites:

- Active Site: A specialized binding site where a substrate binds to an enzyme to induce a chemical reaction. Competitive inhibitors also bind here to block substrate binding [19].

- Allosteric Site: A regulatory site where ligand binding can cause an amplification or suppression of protein function, often by inducing conformational changes [19].

- A Pose describes a single "snapshot" of the spatial arrangement of the ligand relative to the receptor in a stable complex [22]. The central challenge in docking is to identify the near-native binding pose—the one that most closely resembles the true, biologically relevant binding mode observed in experimental structures [23].

Conformational Search and Sampling Algorithms

With present computing resources, it is impossible to exhaustively explore all possible orientations and conformations of the ligand and receptor. Therefore, various strategies are employed to sample the search space with optimal efficiency [22].

- Conformational Search is the process of exploring all possible orientations of the protein with respect to the ligand and, in flexible docking, all possible conformations of the protein paired with all possible conformations of the ligand [22]. The primary search strategies include:

- Shape-Complementarity Methods: These are the most common techniques, focusing on the geometric and chemical match between the receptor and the ligand. Programs like DOCK, GLIDE, and SURFLEX use descriptors of structural complementarity (e.g., solvent-accessible surface area) and binding complementarity (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) to find optimal poses [22].

- Genetic Algorithms: These algorithms explore the vast conformational space by representing each spatial arrangement as a "gene." Programs like GOLD and AutoDock simulate evolution through cross-over and random mutation techniques to find low-energy conformations [22].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: This approach uses classical force fields to simulate the physical movements of atoms. While computationally expensive, MD can be used to generate conformations or, more commonly, to refine and evaluate docking poses by allowing the system to equilibrate in a solvated environment, which can remove a ligand from an unstable predicted position [22] [20].

Scoring Functions

Once a set of candidate poses is generated, they must be ranked to identify the most likely correct one.

- A Scoring Function is a mathematical function used to predict the binding affinity of a ligand pose to a receptor. The accurate identification of the correct binding mode is a critical component of successful docking programs [24]. Scoring functions can be broadly categorized as follows [24]:

- Physics-based: Calculate binding energy by summing Van der Waals and electrostatic interactions, sometimes including solvent effects and polarization. These are computationally intensive [24].

- Empirical-based: Estimate binding affinity by summing a series of weighted energy terms (e.g., van der Waals, hydrogen bonds, desolvation) derived from known 3D structures. They are faster than physics-based methods [24]. GlideScore, FireDock, and RosettaDock are examples [24] [25].

- Knowledge-based: Use statistical potentials derived from the pairwise distances between atoms or residues in known protein complexes, offering a good balance between accuracy and speed [24]. AP-PISA and SIPPER fall into this category [24].

- Machine Learning (ML)-/Deep Learning (DL)-based: These are an emerging area of interest that learn complex functions mapping interface features to a score, often showing improved performance in pose selection [23] [24].

Quantitative Data and Performance Comparison

The performance of different scoring functions and docking methodologies is routinely benchmarked on public datasets to assess their strengths and weaknesses. The table below summarizes a comparative assessment of various classical and deep learning-based scoring functions for protein-protein docking across multiple datasets, highlighting their average ranking performance (a lower Top X value is better) [24].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Classical and Deep Learning-Based Scoring Functions for Protein-Protein Docking [24]

| Method | Type | Average Ranking (Top 1) | Average Ranking (Top 10) | Runtime Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FireDock | Empirical-based | 28.5 | 9.9 | Fast |

| PyDock | Hybrid | 25.5 | 9.1 | Fast |

| RosettaDock | Empirical-based | 21.1 | 7.2 | Slow |

| HADDOCK | Hybrid | 19.6 | 7.0 | Medium |

| AP-PISA | Knowledge-based | 18.4 | 6.5 | Fast |

| DL-based Methods | Deep Learning | 15.8 | 5.5 | Varies (can be fast after training) |

For protein-ligand docking, the accuracy of pose prediction is often evaluated using metrics like Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) from an experimental reference structure. The performance of different docking modes within a single program, such as Glide, can vary based on the sampling intensity and scoring.

Table 2: Performance of Glide Docking Modes in Pose Prediction and Virtual Screening [25]

| Glide Mode | Sampling Intensity | Pose Prediction Success (RMSD < 2.5 Ã…) | Typical Docking Speed | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTVS | Low | Lower than SP | ~2 seconds/compound | Rapidly screen ultra-large libraries |

| SP (Standard Precision) | Medium | 85% (Astex set) | ~10 seconds/compound | Balanced accuracy and speed for virtual screening |

| XP (Extra Precision) | High | Comparable to or higher than SP | ~2 minutes/compound | Lead optimization, analyzing key interactions |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A Standard Protocol for Rigid-Receptor Docking with Glide

The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for docking a library of small molecules against a prepared protein structure using Glide's SP or XP mode, a widely used rigid-receptor docking method [25].

Protein Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of the target receptor from a source like the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

- Process the structure using a tool like the Protein Preparation Wizard. This involves adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states, fixing missing side chains or loops, and optimizing hydrogen-bonding networks.

- Perform a constrained energy minimization to relieve steric clashes while keeping the protein close to its experimental conformation.

- Define the binding site, often by centering a grid box on the co-crystallized ligand or known active site residues.

Ligand Preparation:

- Prepare the ligand library using LigPrep.

- Generate likely ionization states at a specified pH (e.g., 7.0 ± 0.5).

- Generate stereoisomers and low-energy ring conformers.

- Output the structures in a format suitable for docking.

Docking Execution:

- Select the appropriate precision mode: HTVS for initial filtering of very large libraries, SP for standard virtual screening, or XP for more precise scoring and analysis.

- The Glide docking funnel operates as follows [25]:

- Systematic Search: A series of hierarchical filters search for possible ligand orientations within the grid-defined binding site.

- Conformational Sampling: Exhaustive enumeration of ligand torsions is performed.

- Refinement: Promising poses are refined in torsional space within the receptor's field.

- Post-docking Minimization (PDM): A final minimization with full ligand flexibility is performed on the best poses.

Pose Selection and Analysis:

- Poses are ranked primarily using the GlideScore empirical scoring function, which accounts for hydrophobic enclosure, hydrogen bonding, van der Waals interactions, and a rotatable bond penalty [25].

- Visually inspect the top-ranked poses to analyze key protein-ligand interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, pi-stacking, hydrophobic contacts) for rational drug design.

Diagram 1: Standard rigid-receptor molecular docking workflow.

Advanced Protocol: Induced Fit Docking (IFD) for Flexible Receptors

When a ligand induces significant side-chain or backbone movements in the receptor, the rigid-receptor approximation may fail. The Induced Fit Docking (IFD) protocol accounts for this by combining Glide and Prime to model receptor flexibility [25].

Initial Glide Docking:

- The ligand is docked into the rigid receptor using Glide with a softened potential (reduced van der Waals radii) to allow for steric overlap and generate an initial diverse set of poses.

Protein Structure Refinement:

- For each of the initial ligand poses, the protein structure is refined using Prime. Side chains within a specified distance of the ligand are trimmed and repacked, and the protein-ligand complex undergoes energy minimization.

Re-docking and Scoring:

- Each ligand is re-docked into the refined protein structure corresponding to its initial pose, this time using the standard Glide docking parameters.

- The final complexes are ranked using a composite score that combines the GlideScore and the Prime energy.

Protocol for Validating Docking Poses using Molecular Dynamics

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation can be used to assess the stability of a docked pose in a more realistic, solvated environment, acting as a powerful validation step [20].

System Setup:

- Take the top-ranked docking pose and place it in a simulation box filled with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P model).

- Add ions to neutralize the system's charge and achieve physiological concentration.

Equilibration:

- Perform energy minimization to remove bad contacts.

- Run short MD simulations (e.g., 100-500 ps) with positional restraints on the protein and ligand heavy atoms to gently equilibrate the solvent and ions around the complex.

Production Simulation:

- Run an unrestrained MD simulation for a sufficiently long time (e.g., tens to hundreds of nanoseconds). The required time depends on the system's flexibility and the quality of the initial pose.

- A stable pose will show little deviation from the initial docking structure, while an unstable pose may see the ligand dissociate or adopt a completely new orientation [20].

Trajectory Analysis:

- Calculate the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) of the ligand relative to its starting position over the course of the simulation. A stable, flat RMSD profile suggests the pose is stable.

- Analyze the conservation of key protein-ligand interactions throughout the simulation trajectory.

Diagram 2: Molecular dynamics workflow for validating docking poses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Molecular Docking

| Category | Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Software | Glide (Schrödinger) | High-accuracy protein-ligand docking and virtual screening. | Standard and extra-precision docking for hit identification [25]. |

| AutoDock, GOLD | Docking using genetic algorithms for flexible ligand docking. | Exploring a large conformational space for a ligand [22]. | |

| Scoring Functions | Classical (e.g., ZRANK2, PyDock) | Empirical or knowledge-based scoring of protein-protein complexes. | Ranking models in protein-protein docking [24]. |

| Deep Learning-based | Pose selection using models trained on complex structural data. | Improved identification of near-native binding modes [23]. | |

| Structure Preparation | Protein Preparation Wizard | Prepares protein structures for docking (H-add, minimization). | Standardizing a PDB structure for a docking study [25]. |

| LigPrep | Generates accurate 3D ligand structures with correct ionization. | Preparing a corporate compound library for virtual screening [25]. | |

| Simulation & Validation | GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulation package. | Validating the stability of a docked pose in solution [20]. |

| Data Resources | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids. | Source of the target receptor's 3D structure [24]. |

| DUD/E, Astex Set | Benchmark datasets for validating docking and scoring methods. | Testing a docking protocol's pose prediction and enrichment [25]. | |

| m-PEG7-Boc | m-PEG7-Boc, CAS:874208-90-9, MF:C20H40O9, MW:424.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| H-His-NH2.2HCl | H-His-NH2.2HCl, CAS:71666-95-0, MF:C6H11ClN4O, MW:190.63 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The field of structural biology has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the advent of artificial intelligence (AI)-based protein structure prediction. For decades, determining the three-dimensional structure of proteins was a laborious process requiring months to years of painstaking experimental effort using techniques such as X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy [26]. The AlphaFold AI system, developed by Google DeepMind, has fundamentally altered this landscape by providing highly accurate protein structure predictions, achieving accuracy competitive with experimental methods in the majority of cases [26]. This breakthrough has immediate potential to accelerate biological research and drug discovery processes.

The significance of this advancement is underscored by AlphaFold's performance in the 14th Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP14), where it demonstrated atomic accuracy even when no similar structure was known [26]. The subsequent creation of the AlphaFold Database through DeepMind's partnership with EMBL-EBI has democratized access to structural information by providing over 200 million protein structure predictions freely available to the scientific community [27]. This vast resource now enables researchers worldwide to access reliable structural models for nearly any protein sequence, fundamentally changing how we approach structure-based drug design.

AlphaFold's Technical Revolution in Structure Prediction

Evolution of AlphaFold Capabilities

The AlphaFold system has evolved significantly from its initial version to its current state. AlphaFold 2, described in the seminal 2021 Nature paper, introduced a novel neural network architecture that incorporated evolutionary, physical, and geometric constraints of protein structures [26]. This system uses a trunk network comprising Evoformer blocks that process multiple sequence alignments and residue pairs, followed by a structure module that introduces explicit 3D structure through rotations and translations for each residue [26].

The more recent AlphaFold 3 represents a substantial expansion of capabilities, predicting not just protein structures but also DNA, RNA, ligands, and their interactions [28]. This version employs a diffusion-based approach similar to AI image generation models, starting with a random distribution of atoms and progressively 'de-noising' it through iterations to achieve the most plausible biomolecular structure [28]. This advancement allows AlphaFold 3 to predict structures of far more complex molecules and their interactions, achieving at least a 50% improvement in predicting protein interactions compared to previous methods [28].

Accessing and Assessing AlphaFold Predictions

The AlphaFold Database provides open access to protein structure predictions through a user-friendly web interface. Each prediction includes a per-residue confidence score (pLDDT) ranging from 0-100, which reliably predicts the local accuracy of the structure [29] [26]. As a rule of thumb, regions with pLDDT > 80 are considered confident to very high confidence and generally suitable for in silico modeling and virtual screening purposes [29].

Table: Interpreting AlphaFold pLDDT Confidence Scores

| pLDDT Range | Confidence Level | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| 90-100 | Very high | High-resolution analysis, drug binding site identification |

| 70-90 | Confident | Most structure-based drug design applications |

| 50-70 | Low | Low-resolution analysis, domain identification |

| <50 | Very low | Treat with caution; potentially disordered regions |

The database also includes new functionality for custom sequence annotations, allowing researchers to integrate and visualize their own annotations alongside the predicted structures [27]. When using AlphaFold structures for molecular docking, it is critical to assess the confidence scores in the binding pocket regions specifically, as low confidence in these areas may limit the reliability of docking results.

Application Notes: AlphaFold in the Drug Discovery Pipeline

Target Identification and Validation

The first stage of drug discovery involves identifying and validating potential therapeutic targets. AlphaFold structures have significantly accelerated this process by providing immediate access to 3D structural information for novel targets, particularly those without experimental structures [29]. When assessing potential targets using AlphaFold models, researchers should prioritize based on:

- Confidence levels (pLDDT scores) throughout the structure, particularly in putative binding pockets [29]

- Size and accessibility of binding pockets based on surface analysis [29]

- Comparison with known ligand-binding sites in proteins with similar predicted structures [29]

- Uniqueness of the predicted protein fold when drug selectivity is an objective [29]

For targets with confident predictions, researchers can proceed directly to structure-based screening approaches. For those with lower confidence in critical regions, experimental structure determination may be prioritized, though AlphaFold models can still guide construct design for protein expression by identifying domain boundaries indicated by low pLDDT linker regions [29].

Hit Identification through Virtual Screening

AlphaFold structures have proven particularly valuable for virtual screening campaigns where experimental structures are unavailable. The success of structure-based virtual screening depends crucially on the accuracy of the protein structure used, as better docking results are observed with higher-quality structures [30]. With AlphaFold models, researchers can now perform large-scale virtual screening of chemical libraries against targets that were previously inaccessible.

Recent advances in AI-accelerated virtual screening platforms, such as RosettaVS, have demonstrated the ability to screen multi-billion compound libraries in less than seven days, identifying hit compounds with single-digit micromolar binding affinities [31]. These platforms increasingly incorporate active learning techniques to efficiently triage and select the most promising compounds for expensive docking calculations, significantly accelerating the hit identification process [31].

Lead Optimization and Beyond

In the lead optimization phase, AlphaFold structures facilitate understanding of molecular interactions and guide rational drug design. The availability of accurate protein models enables computational methods to exploit target features for making carefully chosen chemical modifications to hit molecules, transforming them into lead candidates with enhanced drug-like properties [29]. Advanced computational approaches like free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations can predict binding energies for series of similar molecules, providing valuable filters for selecting candidate molecules for synthesis [29].

Additionally, AlphaFold models of orthologous proteins across species can inform the selection of preclinical animal models by comparing protein similarity between species and humans [29]. This application helps bridge the translational gap in drug development by ensuring relevant pharmacological testing.

Experimental Protocol: Molecular Docking with AlphaFold Structures

Structure Preparation and Validation

Objective: To prepare and validate AlphaFold protein structures for molecular docking studies.

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Structure Retrieval: Download the desired protein structure from the AlphaFold Database (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/) [27]. Select the format compatible with your docking software (typically PDB format).

Confidence Assessment: Analyze the pLDDT scores throughout the structure, with particular attention to putative binding sites. Reserve structures with pLDDT > 80 in binding regions for docking studies. For regions with lower confidence, consider alternative templates or experimental validation.

Binding Pocket Identification: Use pocket detection algorithms (e.g., fpocket, CASTp) or known functional annotations to identify potential binding sites. Compare with similar proteins of known function if available.

Structure Preparation:

- Remove non-standard residues and crystallization artifacts

- Add hydrogen atoms appropriate for physiological pH (pH 7.4)

- Assign partial charges using standard force fields (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM)

- Optimize side-chain conformations for residues with unclear electron density

Energy Minimization: Perform limited energy minimization to relieve steric clashes while maintaining the overall protein fold. Apply restraints to high-confidence regions (pLDDT > 80) to preserve the core structure.

Validation: If possible, validate the prepared structure by docking known binders and verifying they reproduce experimental binding modes and affinities.

Molecular Docking Protocol Using AlphaFold Structures

Objective: To perform molecular docking of small molecule ligands into prepared AlphaFold protein structures.

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Ligand Preparation:

- Obtain small molecule structures in appropriate formats (e.g., SDF, MOL2)

- Generate plausible tautomers and protonation states for physiological pH

- Perform energy minimization using molecular mechanics force fields

- Assign appropriate atomic charges (e.g., Gasteiger, AM1-BCC)

Search Space Definition: Define the docking grid based on the identified binding pocket. Center the grid on the binding site with sufficient dimensions to accommodate ligand movement (typically 10-15 Ã… in each dimension from the center).

Docking Method Selection: Choose appropriate docking software based on the project requirements:

Docking Execution: Run the docking simulation with appropriate parameters. For flexible docking, allow side-chain flexibility in key binding site residues. Use genetic algorithm or Monte Carlo-based search methods for thorough conformational sampling [2].

Result Analysis:

- Cluster similar binding poses using RMSD-based clustering

- Analyze protein-ligand interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-stacking)

- Evaluate consensus scoring from multiple scoring functions when possible

- Visually inspect top-ranked poses for chemicalåˆç†æ€§

Hit Selection: Prioritize compounds based on docking scores, interaction quality, and chemical properties for experimental validation.

Post-Docking Validation and Analysis

Objective: To validate docking results and select compounds for experimental testing.

Procedure:

Binding Affinity Estimation: Use advanced scoring methods or free energy calculations for more accurate affinity predictions on top hits. Methods like MM-GB/PBSA or free energy perturbation can provide improved correlation with experimental binding energies [29].

Specificity Assessment: Dock promising hits against related off-target proteins to assess potential selectivity issues. The broad coverage of the AlphaFold Database facilitates this cross-screening approach.

Consensus Scoring: Combine results from multiple docking programs or scoring functions to improve hit identification reliability.

Experimental Design: Prioritize compounds for synthesis or purchase based on docking scores, chemical tractability, and drug-like properties. Design appropriate binding or functional assays for experimental validation.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Docking with AlphaFold Structures

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | AlphaFold Database, Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of reliable protein structures for docking studies [27] |

| Small Molecule Libraries | ZINC, PubChem, ChemBL, DrugBank | Collections of compounds for virtual screening [30] |

| Molecular Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, GLIDE, DOCK, RosettaVS | Programs for predicting protein-ligand interactions [30] [31] |

| Structure Preparation Tools | PyMol, Chimera, MOE, Schrödinger Suite | Software for protein cleanup, hydrogen addition, and charge assignment |

| Analysis and Visualization | PyMol, LigPlot+, VMD, UCSF Chimera | Tools for analyzing and visualizing docking results and interactions |

The integration of AlphaFold and AI technologies has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of structural biology and drug discovery. By providing rapid access to accurate protein structures, these tools have democratized structure-based approaches, enabling research groups without structural biology expertise to leverage 3D structural information in their drug discovery programs. The continued evolution of these technologies, including the expanded capabilities of AlphaFold 3 to model protein-ligand complexes directly, promises to further accelerate the drug discovery process [28].

As these AI methods continue to develop, we anticipate increased accuracy in modeling challenging targets such as membrane proteins and protein-protein interactions, broader adoption of multi-target drug discovery approaches leveraging the comprehensive structural coverage, and tighter integration between structure prediction and experimental validation methods. The ongoing development of open-source platforms for AI-accelerated virtual screening will further democratize access to these powerful technologies, potentially reducing the time and cost of early drug discovery [31].

Executing a Docking Analysis: A Practical Workflow from Software Selection to Result Interpretation

In structural biology and computer-aided drug design, the accuracy of molecular docking simulations is fundamentally dependent on the initial quality of the target protein structure. Target preparation, which encompasses cleaning the Protein Data Bank (PDB) file, adding hydrogens, and assigning partial atomic charges, is a critical first step that establishes the physical realism of the computational model [2]. A poorly prepared structure can lead to unrealistic electrostatic potentials, steric clashes, and ultimately, incorrect predictions of ligand binding. This protocol details a robust methodology for preparing a target protein structure, using the crystallographic structure with PDB code 1O86 as a model system [32]. The procedures outlined are designed to be generally applicable to any PDB file and are framed within a comprehensive workflow for molecular docking in drug discovery research.

The target preparation process follows a sequential, logical pathway to transform a raw PDB file into a docking-ready structure. The diagram below visualizes this workflow, highlighting key decision points and the primary output for each stage.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential software tools and resources required for the successful execution of this target preparation protocol.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Software Tools

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Key Features & Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank | Database | Primary repository for obtaining initial 3D structural data (e.g., PDB ID: 1O86) in legacy PDB format [32]. |

| UCSF Chimera | Molecular Visualization & Editing | A python-based, open-source software suite used for graphical inspection, isolation of the protein, deletion of heteroatoms (water, ligands), and structural manipulation [32]. |

| pdb-tools | Command-Line Software Suite | A "Swiss army knife" for programmatic manipulation of PDB files. Useful for tasks like selecting specific chains (pdb_selchain), deleting heteroatoms (pdb_delhetatm), and removing hydrogens (pdb_delelem -H) in an automated workflow [33]. |

| DOCK | Molecular Docking Suite | The docking program for which the structure is being prepared. Its associated scripts or built-in functions are often used for assigning charges (e.g., using AMBER force field parameters) and energy minimization [32]. |

| AMBER/CHARMM Force Fields | Parameter Sets | Libraries of predefined atomic parameters, including partial charges and bond energies, which are applied to the protein structure to create a physically realistic model for energy calculations [32] [34]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Downloading and Initial Inspection of the PDB File

Objective: To acquire the initial protein structure and visually assess its components.

- Navigate to the RCSB PDB website (https://www.rcsb.org).

- Enter the PDB code "1O86" (or your code of interest) in the search bar.

- On the structure summary page, locate the "Download Files" dropdown menu in the top right corner.

- Select "Legacy PDB Format" to download the coordinate file. This format is universally compatible with most molecular visualization and docking software [32].

- Open the downloaded file in a molecular visualization program like UCSF Chimera. Conduct an initial visual inspection to identify the protein chain(s), any bound ligands, cofactors, water molecules, and other heterostates.

Protein Isolation and Structure Cleaning

Objective: To remove non-essential molecular components that are not part of the target protein and may interfere with docking.

- Ligand and Cofactor Removal:

- In UCSF Chimera, zoom into the binding site of interest.

- Hold the

Controlkey and click to select an atom belonging to the ligand or non-protein molecule. - Press the

Up Arrowkey to select the entire connected molecule. - Go to

Actions >> Atoms/Bonds >> Deleteto remove the selected molecule [32]. - Repeat for any other extraneous ligands or cofactors not relevant to your study.

- Water Molecule Removal:

- Navigate to

Select >> Residue >> HOH. This will select all water residues in the structure. - With all water molecules highlighted, proceed to

Actions >> Atoms/Bonds >> Deleteto remove them [32].

- Navigate to

- Alternative Command-Line Method:

- For users preferring a script-based approach, the

pdb-toolssuite is highly effective. - To select a specific chain (e.g., chain A) and remove all heteroatoms and waters, then produce a tidy PDB file, use the following command: This pipeline selects chain A, deletes heteroatoms (HETATM records), and ensures the output is a valid PDB file [33].

- For users preferring a script-based approach, the

Addition of Hydrogen Atoms

Objective: To add hydrogen atoms to the protein structure, which are critical for modeling hydrogen bonds and correct electrostatics, but are often absent in crystallographic data.

- In UCSF Chimera, ensure your cleaned protein structure is displayed.

- Go to

Tools >> Structure Editing >> AddH. This opens the Add Hydrogens tool. - Select the appropriate protonation states for histidine residues and other titratable amino acids (e.g., aspartic acid, glutamic acid, lysine) based on their local environment and predicted pKa values. Using

Tools >> Structure Editing > > Add Chargecan often handle this in an integrated manner. - Execute the command to add hydrogens. The program will place hydrogens at standard geometries according to the chosen force field.

Assignment of Partial Charges

Objective: To assign atomic partial charges, which are essential for calculating electrostatic interaction energies during docking.

- The method for charge assignment is often integrated with the addition of hydrogens in tools like UCSF Chimera.

- Using

Tools >> Structure Editing >> Add Chargewill typically open a menu for charge addition. - Select a suitable force field, such as AMBER ff14SB or CHARMMM, which provides a set of predefined partial charges for standard amino acids [32].

- The software will assign these charges based on the force field parameters, which include contributions from bond and angle terms, torsions, and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatics) [34]. The total potential energy (U_total) used in docking is often the sum of these electrostatic and van der Waals components [34].

Energy Minimization (Optional but Recommended)

Objective: To relieve any minor steric clashes or geometric strain introduced by the addition of hydrogen atoms.

- Use the energy minimization module within your preparation software or the docking suite itself (e.g., DOCK6).

- A typical protocol involves a few steps of steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization, while keeping the heavy atoms of the protein backbone restrained. This allows the added hydrogens to relax into low-energy positions without distorting the experimental protein conformation.

- The resulting energy-minimized structure is now a docking-ready target [32].

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

| Common Issue | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Program cannot open/file not found | Incorrect file path or filename. | Use the realpath command to verify the absolute file path. Sanity-check paths by copying them into an ls command [32]. |

| Unexpectedly poor docking results | Incorrect protonation state of key binding site residues. | Re-check the protonation states of histidine, aspartate, glutamate, etc., using computational pKa prediction tools and manually adjust in the molecular editor. |

| Charges not assigned/found | Incorrect force field parameters or file format. | Ensure the chosen force field is supported and that the input file is correctly formatted. Check the program's output log for specific error messages [32]. |

| Structural artifacts after minimization | Overly aggressive minimization without positional restraints. | Repeat minimization with stronger positional restraints on all non-hydrogen protein atoms to preserve the experimental crystal structure. |

Accurately identifying the binding site on a protein target is a critical second step in the molecular docking pipeline, directly determining the success of subsequent docking simulations and the validity of the resulting drug leads [35]. This stage involves pinpointing the specific region—often a cleft or cavity on the protein surface—where a ligand binds, facilitating the intricate molecular recognition governed by non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, and van der Waals forces [35]. This guide details three complementary methodologies for binding site identification: leveraging known ligand complexes, employing computational prediction tools, and mining existing scientific literature. A systematic approach integrating these strategies provides a robust foundation for structure-based drug design.

Methodological Approaches

Using Known Ligands from Experimental Structures

Principle: This method utilizes experimentally determined 3D structures of protein-ligand complexes from structural databases, providing a high-confidence starting point for docking studies focused on the same protein or close homologs.

Protocol: Identifying a Binding Site via the Protein Data Bank (PDB)

- Access the PDB: Navigate to the Protein Data Bank (PDB) website (www.rcsb.org).

- Search for the Target: Use the search bar to query your protein target by its name, UniProt ID, or gene symbol. To find structures with relevant ligands, use the advanced search function to filter for "Has Macromolecule" and "Has Ligand."

- Select Relevant Structures: Review the search results. Prioritize structures based on:

- High Resolution: Prefer structures with a resolution of 2.0 Ã… or better.

- Relevant Ligand: Identify structures bound to a native substrate, a known drug, or a inhibitor with demonstrated activity.

- Low Mutations: Ensure the protein sequence and structure are as close as possible to your target of interest.

- Analyze the Complex: Download the PDB file and open it in a molecular visualization tool (e.g., PyMOL, UCSF Chimera). Identify the ligand and define the binding site residues as all amino acids within a specific radius (e.g., 5-7 Ã…) of the bound ligand.

- Prepare the Binding Site: For docking, the binding site residues and any key structural waters (if evidence supports their role) should be defined in your docking software. The protein structure may require further preparation, including adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and optimizing side-chain orientations.

Computational Prediction of Binding Sites