Benchmarking Gene Finding Algorithms in Prokaryotic Genomes: A Guide for Accuracy and Reliability

Accurate gene annotation is the cornerstone of prokaryotic genomics, influencing everything from understanding evolution and niche adaptation to drug target identification.

Benchmarking Gene Finding Algorithms in Prokaryotic Genomes: A Guide for Accuracy and Reliability

Abstract

Accurate gene annotation is the cornerstone of prokaryotic genomics, influencing everything from understanding evolution and niche adaptation to drug target identification. However, the process is fraught with challenges, including inconsistent annotations, horizontal gene transfer, and difficulties in clustering orthologs. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and bioinformaticians to benchmark gene-finding algorithms. We explore the foundational principles of prokaryotic pangenomes, outline rigorous methodological approaches for comparing tools, address common troubleshooting and optimization scenarios, and establish robust validation and comparative analysis techniques. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and reproducibility of genomic studies in microbiology and drug development.

The Prokaryotic Pangenome: Foundations and Annotation Challenges

The genomic landscape of prokaryotes is characterized by remarkable diversity, driven by mechanisms such as horizontal gene transfer, gene duplication, and gene loss [1]. This diversity means that the gene content can vary substantially between different strains of the same species. The pangenome concept was developed to encompass the total repertoire of genes found within a given taxonomic group, moving beyond the limitations of analyzing a single reference genome [2]. For any set of related prokaryotic genomes, the pangenome can be divided into distinct components based on gene prevalence: the core genome, the shell genome, and the cloud genome [2]. Accurately defining these components is a fundamental step in prokaryotic genomics, with critical applications in understanding microbial evolution, niche adaptation, and in the drug discovery pipeline for identifying potential therapeutic targets, such as conserved virulence factors [3].

This guide objectively compares the performance of modern software tools developed to infer the pangenome from a collection of annotated genomes. As the volume of genomic data grows exponentially, the challenges of scalability, error correction, and accurate orthology clustering become increasingly central to robust analysis [4] [5].

Foundational Concepts: Core, Shell, and Cloud

The pangenome is partitioned based on the commonality of gene clusters across the analyzed genomes. Table 1 summarizes the defining features of each component.

Table 1: Defining the Components of a Pangenome

| Pangenome Component | Definition (Prevalence) | Typical Functional Role | Evolutionary Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Genome | Genes present in ≥95% to 100% of genomes [2]. | Housekeeping functions, primary metabolism, essential cellular processes [2]. | Highly conserved, slow turnover. |

| Shell Genome | Genes present in a majority (e.g., 10%-95%) of genomes [2]. | Niche-specific adaptation, secondary metabolism [2]. | Moderate conservation, dynamic gain and loss. |

| Cloud Genome | Genes present in <10% to 15% of genomes, including strain-specific singletons [2]. | Ecological adaptation, mobile genetic elements, recent horizontal acquisitions [2]. | Rapid turnover, very high diversity. |

The gene commonality distribution—plotting the number of genes present in exactly k genomes—typically exhibits a U-shape, with one peak representing the cloud genes (low k), another representing the core genes (high k), and the shell genes forming the shallow middle region [6] [7]. Furthermore, species can be categorized as having an "open" or "closed" pangenome. An open pangenome is one where the total number of genes continues to increase significantly with each newly sequenced genome, indicating a vast accessory gene pool. In contrast, a closed pangenome reaches a saturation point where new genomes contribute few or no new genes [2]. Environmental factors, such as habitat versatility, have been shown to have a stronger impact on pangenome size and structure than phylogenetic history, with free-living organisms (e.g., in soil) tending towards larger, open pangenomes, while host-associated species often have more closed, reduced pangenomes [3].

Benchmarking Pangenome Analysis Tools

The core computational task in pangenomics is clustering homologous genes from multiple genomes into orthologous groups. Numerous tools have been developed for this purpose, each with different strategies for handling the complexities of prokaryotic genome evolution and annotation errors. Table 2 provides a comparative summary of leading tools based on recent benchmark studies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Pangenome Inference Tools

| Tool | Clustering Approach | Key Strength | Reported Limitation / Consideration | Scalability (Typical Use Case) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panaroo [1] | Graph-based (after initial CD-HIT clustering) | Robust error correction for annotation artifacts (fragmented genes, contamination). | Sensitive mode may retain more potential errors [1]. | Suitable for large datasets (1000s of genomes). |

| PanTA [4] | Homology-based (CD-HIT & MCL) | Unprecedented computational efficiency and a unique progressive mode for updating pangenomes. | Approach optimized for speed without major compromises in accuracy [4]. | Designed for very large-scale analyses (10,000s of genomes). |

| PGAP2 [5] | Fine-grained feature networks (identity & synteny) | High accuracy in identifying orthologs/paralogs; provides quantitative cluster metrics. | More complex workflow than some alternatives [5]. | Suitable for large datasets (1000s of genomes). |

| PIRATE [1] [4] | Homology-based (with progressive clustering) | Handles multi-copy gene families effectively [1]. | Can be computationally intensive for very large sets [4]. | Suitable for medium to large datasets. |

| Roary [4] [3] | Homology-based (BLAST/MCL) | Widely adopted, integrated in many analysis pipelines. | More sensitive to annotation errors compared to graph-based methods [1]. | Fast, but may be less accurate for accessory genome. |

Key Performance Insights from Experimental Data

- Error Correction Impact: A benchmark on a highly clonal Mycobacterium tuberculosis dataset (where little pangenome variation is expected) demonstrated that Panaroo, with its integrated error correction, identified a core genome of ~3,100 genes and an accessory genome of only ~300 genes. In contrast, other tools (Roary, PIRATE, PPanGGOLiN) reported inflated accessory genomes ranging from ~2,500 to over ~10,000 genes, highlighting how annotation errors can severely distort results [1].

- Scalability and Efficiency: In a comparison run on a laptop computer using datasets of 600 to 1500 genomes, PanTA completed pangenome construction significantly faster and with lower memory usage than Panaroo, PIRATE, and PPanGGOLiN. Crucially, its progressive mode allowed adding new genomes to an existing pangenome without recomputing from scratch, reducing memory usage by half without sacrificing accuracy [4].

- Accuracy in Orthology Inference: PGAP2 was evaluated on simulated and gold-standard datasets against Roary, Panaroo, PanTa, and PPanGGOLiN. It consistently demonstrated superior precision and robustness, particularly in clustering stability and the accurate identification of paralogous genes, which is essential for a correct definition of the core genome [5].

Experimental Protocols for Tool Validation

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of pangenome analyses, researchers employ rigorous validation protocols. The methodologies below are commonly cited in benchmarking studies.

Protocol 1: Validation Using a Clonal Control Dataset

This protocol tests a tool's ability to reject false-positive accessory genes.

- Dataset Selection: Obtain a set of genomes from a highly clonal bacterial population, such as an Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreak strain, where the maximum pairwise single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) distance is very low (e.g., <10 SNPs) [1].

- Genome Annotation: Annotate all genome assemblies consistently using a standard tool like Prokka [1] [3].

- Pangenome Inference: Run the tools being evaluated on the annotated genomes using their default parameters.

- Output Analysis: The ground truth expectation is a large core genome and a very small accessory genome. Tools that report a large number of accessory genes are likely inflating their estimates due to fragmented assemblies or other annotation errors [1].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking with Simulated Data

This approach allows for performance assessment against a known ground truth.

- Data Simulation: Use evolutionary models that simulate gene gain, loss, and duplication to generate a collection of synthetic genomes with a predefined pangenome structure [5] [8].

- Pangenome Inference: Run the tools on the simulated genomes.

- Accuracy Assessment: Compare the inferred gene clusters to the known simulated clusters. Metrics include:

- Precision and Recall: For core, shell, and cloud gene clusters.

- Paralog Splitting Accuracy: The correct identification of genes originating from recent duplication events [5].

Visualizing Pangenome Analysis Workflows

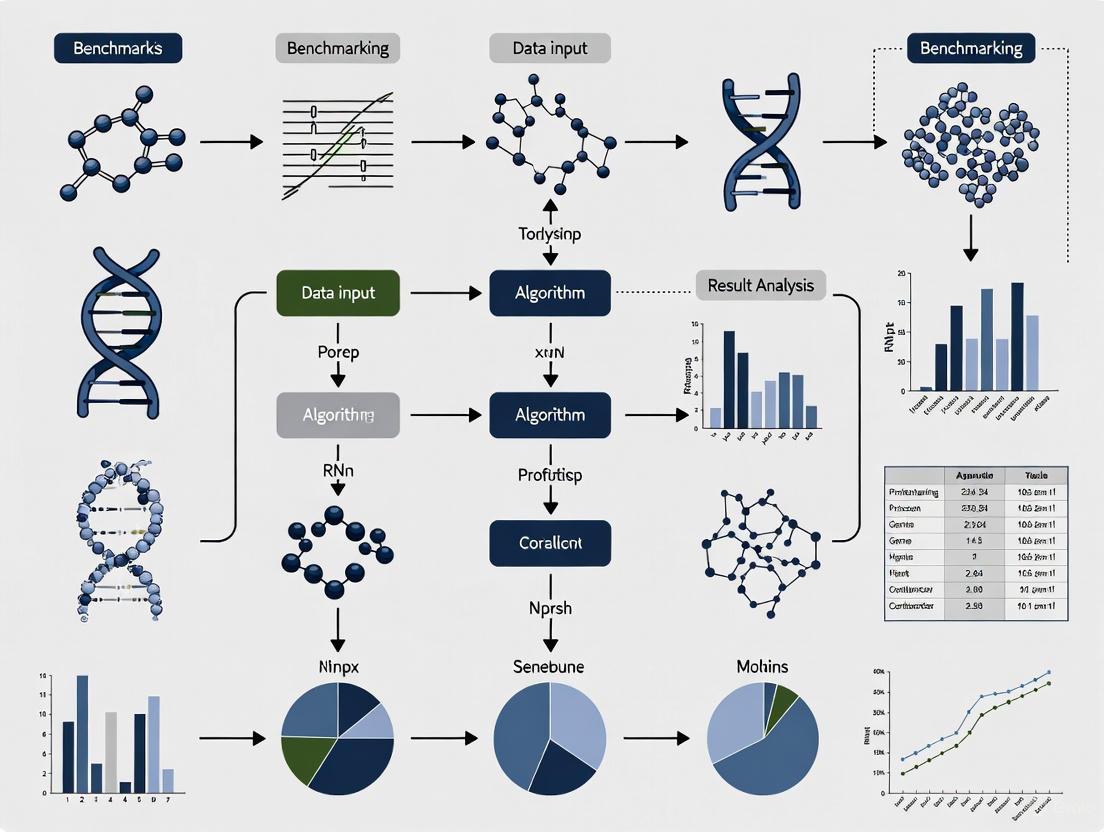

The following diagram illustrates the generalized logical workflow for pangenome inference, integrating steps common to most modern tools.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for prokaryotic pangenome inference, from input genomes to analyzable outputs.

Successful pangenome analysis relies on a suite of software tools and databases. The following table details key resources for constructing and analyzing a pangenome.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Pangenome Analysis

| Resource Name | Type / Category | Primary Function in Pangenome Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Prokka [1] [3] | Genome Annotation Tool | Provides rapid, standardized annotation of draft genomes, generating the essential GFF3 and protein FASTA files required by pangenome tools. |

| CD-HIT [1] [4] | Sequence Clustering Tool | Used by many pipelines for initial, fast clustering of highly similar protein sequences to reduce computational burden. |

| DIAMOND [1] [4] | Sequence Aligner | A high-speed alternative to BLAST for performing all-against-all homology searches of protein sequences. |

| MCL (Markov Clustering) [1] [4] | Graph Clustering Algorithm | The core algorithm used by many tools (e.g., Roary, PanTA) to cluster homologous sequences into gene families based on similarity graphs. |

| Roary [3] | Pangenome Pipeline | A widely used and fast pipeline for pangenome construction, often serving as a benchmark for newer tools. |

| Panaroo [1] | Pangenome Pipeline | A graph-based pipeline renowned for its robust error correction capabilities, improving the accuracy of gene clusters. |

| PATRIC / proGenomes [3] | Genomic Database | Curated databases for obtaining high-quality genome sequences and associated metadata (e.g., habitat, disease association). |

The accurate definition of the core, shell, and cloud components of a prokaryotic pangenome is a critical endeavor in microbial genomics. Benchmarking studies consistently reveal that the choice of computational tool has a profound impact on the biological conclusions drawn. While established tools like Roary offer speed and wide usage, newer graph-based and highly scalable algorithms like Panaroo, PGAP2, and PanTA provide significant advantages in terms of error correction, clustering accuracy, and computational efficiency.

For researchers, the optimal tool choice depends on the specific research question and dataset scale. For studies prioritizing accuracy in orthology and error-free clustering, Panaroo and PGAP2 are excellent choices. When analyzing thousands of genomes or regularly updating a pangenome with new data, PanTA's progressive mode offers an unparalleled performance benefit. By leveraging the experimental protocols and benchmarks outlined in this guide, scientists and drug development professionals can make informed decisions, ensuring their pangenome analyses are both robust and reproducible.

The Impact of Horizontal Gene Transfer on Gene Content and Diversity

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT), also known as lateral gene transfer, is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the traditional vertical transmission of DNA from parent to offspring [9]. In the context of prokaryotic genomics, HGT is not merely a curiosity but a fundamental evolutionary force that profoundly shapes gene content and genetic diversity. It allows for the direct combination of genes evolved in entirely different contexts, enabling prokaryotes to explore the gene content space with remarkable speed and to adapt rapidly to new environmental challenges [10] [11]. For researchers benchmarking gene-finding algorithms, understanding HGT is crucial, as its detection and characterization present unique computational challenges. The very presence of horizontally acquired genes can disrupt standard phylogenetic analyses and gene prediction pipelines, necessitating specialized tools and benchmarking approaches to accurately decipher prokaryotic genome structure and function.

The impact of HGT extends far beyond basic evolutionary theory into highly practical domains. It is the primary mechanism for the spread of antibiotic resistance in bacteria, plays a critical role in the evolution of virulence pathways, and allows bacteria to acquire the ability to degrade novel compounds such as human-created pesticides [9] [12]. From a bioinformatics perspective, the identification of HGT events is typically inferred through computational methods that either identify atypical sequence signatures ("parametric" methods) or detect strong discrepancies between the evolutionary history of particular sequences compared to that of their hosts [9]. As such, robust benchmarking of HGT detection methods forms an essential component of prokaryotic genomics research, enabling more accurate genome annotation and a deeper understanding of bacterial evolution and adaptation.

Mechanisms of Horizontal Gene Transfer

Horizontal gene transfer in prokaryotes occurs through several well-established mechanisms, each with distinct biological processes and implications for genetic diversity. A comprehensive understanding of these mechanisms is essential for developing and benchmarking computational tools designed to detect HGT events in genomic data.

Classical Mechanisms

The three primary classical mechanisms of HGT are transformation, transduction, and conjugation [11] [12].

Transformation: This process involves the uptake and incorporation of naked DNA from the environment into a prokaryotic cell's genome [11]. When cells lyse, they release their contents, including their genomic DNA, into the environment. Naturally competent bacteria actively bind to this environmental DNA, transport it across their cell envelopes, and incorporate it into their genomes through recombination. Transformation represents a significant mechanism for the acquisition of genetic elements encoding virulence factors and antibiotic resistance in nature [11].

Transduction: This mechanism involves the transfer of bacterial DNA from one cell to another via bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) [11]. During the viral life cycle, fragments of bacterial DNA may be accidentally packaged into phage heads instead of viral DNA. When these phage particles infect new host cells, they introduce the bacterial DNA, which may then recombine into the recipient's genome. In specialized transduction, lysogenic phages may carry virulence genes to new hosts, converting previously non-pathogenic bacteria into pathogenic strains, as seen with Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Clostridium botulinum [11].

Conjugation: Often described as "bacterial mating," conjugation involves the direct transfer of DNA between bacterial cells through a specialized conjugation pilus [11]. In E. coli, this process is mediated by the F (fertility) plasmid, which encodes the proteins necessary for pilus formation and DNA transfer. Cells containing the F plasmid (F+ cells) can form conjugation pili and transfer a copy of the plasmid to F- cells (those lacking the plasmid). When the F plasmid integrates into the bacterial chromosome, forming an Hfr (high frequency of recombination) cell, it can facilitate the transfer of chromosomal genes to recipient cells [11].

Newly Discovered Mechanisms

Recent research has identified additional mediators of HGT that expand our understanding of genetic exchange in prokaryotes:

Gene Transfer Agents (GTAs): These are bacteriophage-like particles produced by some bacteria that package random fragments of the host's DNA and transfer them to recipient cells [12]. Unlike true bacteriophages, GTAs do not contain viral DNA and appear to have evolved specifically for gene transfer.

Nanotubes: Some bacteria form intercellular membrane nanotubes that create physical connections between cells, allowing the exchange of cytoplasmic contents including proteins, metabolites, and plasmid DNA [12].

Membrane Vesicles (MVs)/Extracellular Vesicles (EVs): These bilayer structures bud from the bacterial membrane and contain various biomolecules, including DNA. They can transfer this genetic material to recipient cells in a protected form, increasing the likelihood of successful gene transfer [12].

The following diagram illustrates the key mechanisms of horizontal gene transfer in prokaryotes:

Quantitative Impact of HGT on Prokaryotic Genomes

Understanding the quantitative impact of HGT on prokaryotic genomes is essential for benchmarking gene-finding algorithms, as horizontally acquired genes can significantly challenge annotation pipelines. Large-scale genomic analyses provide crucial baseline metrics for evaluating the performance of HGT detection tools.

Prevalence and Functional Enrichment

A systematic analysis of HGT across 697 prokaryotic genomes revealed that approximately 15% of genes in an average prokaryotic genome originated through horizontal transfer [10]. This study employed a detection method based on comparing BLAST scores between homologous genes to 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic distances between organisms. The research identified a clear correlation between genome size and the proportion of HGT-derived genes, with larger genomes generally containing a higher percentage of horizontally acquired genetic material [10].

Functional analysis of horizontally transferred genes reveals distinct patterns of enrichment. Genes related to protein translation, a core cellular process, are predominantly vertically inherited, showing strong conservation within lineages [10]. In contrast, genes encoding transport and binding proteins are strongly enriched among HGT genes [10]. This functional bias makes biological sense, as transport proteins are directly involved in cell-environment exchanges, and their acquisition through HGT can provide immediate adaptive advantages, such as the ability to utilize novel nutrient sources or to export toxic compounds.

Impact on Genome Structure and Interaction Networks

Horizontally acquired genes exhibit distinct characteristics in their genomic context and interaction patterns:

Protein Interaction Networks: Studies performed with the Escherichia coli W3110 genome demonstrate that proteins encoded by HGT-derived genes participate in fewer protein-protein interactions compared to vertically inherited genes [10]. This suggests that the complexity of interaction networks imposes constraints on horizontal transfer, with genes encoding components of complex multimolecular systems being less likely to be successfully integrated and maintained after transfer.

Integration Limitations: The number of protein partners a gene product has appears to limit its horizontal transferability [10]. Genes whose products function as independent units or in simple pathways are more readily transferred and integrated into new genomic contexts, while those involved in complex, co-adapted interactions face greater barriers to successful horizontal acquisition.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of HGT on Prokaryotic Genomes Based on Large-Scale Analysis

| Metric | Finding | Methodological Basis | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average HGT Prevalence | ~15% of genes in prokaryotic genomes [10] | BLAST score comparison to 16S rRNA phylogenetic distances [10] | Baseline for algorithm sensitivity expectations |

| Genome Size Correlation | Positive correlation with HGT proportion [10] | Analysis across 697 prokaryotic genomes [10] | Size-dependent benchmarking thresholds |

| Functionally Enriched Categories | Transport and binding proteins [10] | Functional classification of HGT candidates [10] | Functional bias in algorithm validation |

| Functionally Depleted Categories | Protein translation machinery [10] | Phylogenetic reconstruction of HGT candidates [10] | Core genome definition for benchmarking |

| Network Property | HGT proteins have fewer interactions [10] | Protein-protein interaction network analysis [10] | Contextual constraints on successful HGT |

Detection Methods and Benchmarking Frameworks

Accurately detecting horizontal gene transfer events is fundamental to understanding its impact on gene content and diversity. Multiple computational approaches have been developed, each with distinct methodological foundations and performance characteristics that must be considered when selecting tools for prokaryotic genome analysis.

Methodological Approaches

HGT detection methods generally fall into two broad categories:

Parametric Methods: These approaches identify horizontally transferred genes based on atypical sequence signatures, such as deviations in GC content, codon usage, or oligonucleotide frequencies compared to the host genome [9]. These methods leverage the fact that newly acquired genes may retain sequence composition characteristics of their original genomic context, creating detectable anomalies in the recipient genome.

Phylogenetic Methods: These methods identify HGT events by detecting strong discrepancies between the evolutionary history of particular gene sequences and that of their host organisms [9]. A gene that has been horizontally transferred will show a phylogenetic relationship that is incongruent with the species phylogeny (typically based on ribosomal RNA genes). The method described in [10], which compares BLAST scores between homologous genes to 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic distances, falls into this category.

More recent approaches have incorporated additional layers of analysis. For instance, some methods now consider the network properties of genes, recognizing that horizontally transferred genes often occupy peripheral positions in protein-protein interaction networks [10]. Other approaches combine multiple lines of evidence to improve detection accuracy, integrating compositional, phylogenetic, and functional information.

Benchmarking Strategies and Challenges

Benchmarking gene-finding and HGT detection algorithms presents significant methodological challenges that require carefully designed strategies:

Cross-Validation Frameworks: Robust benchmarking typically employs cross-validation techniques, where a portion of the dataset is withheld while the remainder is used for training or analysis [13]. The ability of an algorithm to recover the withheld data then provides a measure of its performance. This approach has been successfully applied in benchmarking gene prioritization methods and can be adapted for HGT detection tools [13].

Performance Metrics: Multiple metrics are necessary to comprehensively evaluate HGT detection tools. These include standard classification metrics such as sensitivity and specificity, as well as ranking-based measures like the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), partial AUC (focusing on high-specificity regions), Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG), and Median Rank Ratio [13]. Each metric captures different aspects of performance, with ranking measures being particularly important when tools prioritize candidate HGT genes for further investigation.

Ground Truth Challenges: A fundamental difficulty in benchmarking HGT detection methods is the lack of reliable "ground truth" datasets [14]. Simulation approaches that generate biologically realistic data with known HGT events provide a partial solution. For example, scDesign3 represents a framework that can simulate spatial transcriptomics data by modeling gene expression as a function of spatial location with a Gaussian Process model [14]. Similar approaches could be adapted for simulating genomic sequences with controlled HGT events.

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Benchmarking Gene-Finding and HGT Detection Algorithms

| Metric | Calculation/Definition | Interpretation in HGT Detection Context |

|---|---|---|

| AUC (Area Under ROC Curve) | Probability of ranking a true positive higher than a true negative [13] | Overall discriminative power of the detection method |

| Partial AUC | AUC calculated up to a specific false positive rate (e.g., 0.02) [13] | Performance focused on high-confidence predictions |

| Median Rank Ratio (MedRR) | Median rank of true positives divided by total list length [13] | How high true HGT genes appear in candidate lists |

| NDCG (Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain) | Discounted cumulative gain normalized by ideal DCG [13] | Ranking quality with emphasis on top predictions |

| Top 1%/10% Recovery | Proportion of true positives in top 1% or 10% of predictions [13] | Practical utility for prioritization of experimental validation |

The following diagram illustrates a generalized benchmarking workflow for evaluating HGT detection methods:

Research Toolkit for HGT Studies

Investigating horizontal gene transfer requires specialized computational tools and resources. The following table outlines essential components of the research toolkit for HGT studies, particularly focused on benchmarking gene-finding algorithms in prokaryotic genomes.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for HGT Detection and Benchmarking Studies

| Tool/Resource Category | Specific Examples/Functions | Application in HGT Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Composition Methods | GC content, codon usage, oligonucleotide frequency analyzers | Detection based on sequence signature anomalies [9] |

| Phylogenetic Incongruence Methods | BLAST score comparison to 16S rRNA distances [10] | Identification of genes with divergent evolutionary histories [10] [9] |

| Functional Association Networks | FunCoup and similar networks [13] | Context-based prediction of gene relationships and HGT impact |

| Benchmarking Platforms | OpenProblems and custom benchmarking suites [14] | Standardized evaluation of multiple detection methods |

| Simulation Frameworks | scDesign3 and similar tools [14] | Generation of realistic benchmark data with known HGT events |

| Gene Ontology Resources | GO term databases and annotations [13] | Functional validation and benchmarking of prediction methods |

| THR-|A agonist 3 | THR-|A agonist 3, MF:C29H32ClO5P, MW:527.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Panosialin-IA | Panosialin-IA|RUO Enzyme Inhibitor |

Horizontal gene transfer represents a fundamental evolutionary mechanism that significantly impacts prokaryotic gene content and diversity. Through various mechanisms including transformation, transduction, conjugation, and newly discovered pathways involving gene transfer agents and extracellular vesicles, HGT introduces approximately 15% of the genetic material in an average prokaryotic genome, with a clear bias toward genes involved in transport and environmental interactions [10] [12]. This substantial contribution to genomic diversity presents both challenges and opportunities for researchers working on gene-finding algorithms and prokaryotic genome annotation.

The benchmarking of HGT detection methods requires sophisticated approaches that address the inherent difficulties in establishing ground truth, with simulation frameworks and cross-validation strategies providing practical solutions [14] [13]. By employing comprehensive performance metrics that capture different aspects of algorithm performance—from overall discriminative power (AUC) to practical utility for experimental prioritization (top 1% recovery)—researchers can make informed decisions about tool selection and development priorities [13]. As our understanding of HGT mechanisms continues to evolve and computational methods become increasingly sophisticated, robust benchmarking will remain essential for advancing the field of prokaryotic genomics and fully elucidating the impact of horizontal gene transfer on biological diversity and adaptation.

Automated gene annotation is a foundational step in genomic research, enabling the identification and characterization of protein-coding genes within newly sequenced genomes. For prokaryotic genomes, this process involves calling Coding Sequences (CDS) to build an accurate structural annotation. However, researchers face significant challenges due to inconsistencies in how different computational algorithms perform this task. The absence of a universal standard has led to considerable variation in gene predictions, complicating comparative genomics and meta-analyses [15].

This guide examines the common pitfalls of fragmented genes and inconsistent CDS calling through the lens of benchmarking studies. We objectively compare the performance of predominant gene-finding algorithms, supported by experimental data, to provide researchers with evidence-based recommendations for their genomic annotation workflows.

Critical Pitfalls in Prokaryotic Gene Annotation

The Fragmented Gene Problem

Fragmented genes occur when annotation pipelines incorrectly split a single coding sequence into multiple discrete gene calls. This error typically arises from issues in identifying legitimate start and stop codons or from overlooking weak but functional gene signals. The consequences are biologically significant: fragmented predictions lead to incomplete protein sequences, erroneous functional assignments, and compromised understanding of metabolic pathways [15] [16].

NCBI's genome processing guidelines explicitly flag assemblies with abnormal gene-to-sequence ratios (outside 0.8-1.2 genes/kb) as potentially problematic, with extremes below 0.5 or above 1.5 genes/kb indicating likely annotation errors [16]. Such fragmentation particularly affects shorter genes and those with atypical sequence composition.

Inconsistent CDS Calling Across Algorithms

A fundamental challenge in gene annotation is the lack of consensus among prediction algorithms. Research evaluating GeneMarkS, Glimmer3, and Prodigal revealed that only approximately 70% of gene predictions were identical across all three methods when requiring matching start and stop coordinates [15]. This discrepancy means nearly one-third of gene calls vary depending on the algorithm selected.

The table below summarizes the agreement rates between major prokaryotic gene callers from a benchmarking study of 45 bacterial replicons:

| Comparison Metric | Agreement Rate | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Full consensus (identical start/stop) | 67-73% | Percentage of total predictions identical across all three methods [15] |

| Consensus with varying start codons | 83-96% | Percentage when allowing different start codons [15] |

| Pairwise agreement (Prodigal vs. GeneMarkS) | Highest | Most agreement between these two methods [15] |

| Pairwise agreement (Prodigal vs. Glimmer3) | Lowest | Least agreement between these two methods [15] |

| Unique predictions by Glimmer3 | ~2× more than others | Nearly twice as many unique calls versus Prodigal and GeneMarkS [15] |

Inconsistent CDS calling creates substantial challenges for databases and comparative studies, as the same genomic region may be annotated with different gene structures, different functional assignments, or even missed entirely depending on the annotation pipeline employed.

Benchmarking Gene-Finding Algorithms: Experimental Approaches

Proteogenomic Validation Methods

Benchmarking studies typically employ proteogenomic validation, using experimentally detected peptides to evaluate the accuracy of computational gene predictions. The general methodology follows these key steps:

Reference Dataset Compilation: Mass spectrometry-derived peptide data is compiled from public resources or generated specifically for the study. One comprehensive analysis utilized 1,004,576 peptides from 45 bacterial replicons with GC content ranging from 31% to 74% [15].

Gene Prediction Execution: Multiple gene-finding algorithms (e.g., GeneMarkS, Glimmer3, Prodigal) are run on the same genomic sequences.

Error Categorization: Peptide mappings are analyzed to identify three primary error types:

- Wrong Gene Calls: Peptides mapping outside predicted gene boundaries or to the wrong strand.

- Short Gene Calls: Peptides mapping upstream of predicted start sites, indicating extended coding regions.

- Missed Gene Calls: Genomic regions with peptide evidence but no corresponding gene prediction [15].

This experimental workflow provides an objective measure of gene caller performance based on empirical evidence rather than computational self-assessment.

Performance Comparison of Major Algorithms

Benchmarking against proteomic data reveals clear performance differences between gene-calling algorithms. The following table summarizes error rates detected in a large-scale evaluation:

| Gene Caller | Total Errors | Wrong Gene Calls | Short Gene Calls | Missed Gene Calls | Peptide Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glimmer3 | Highest | Highest | Highest | Highest | 994,973 |

| GeneMarkS | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate | 996,336 |

| Prodigal | Lowest | Lowest | Lowest | Lowest | 1,000,574 |

| GenePRIMP | Fewest overall | Fewest overall | Fewest overall | Higher than Prodigal* | N/A |

*GenePRIMP identifies some genes with interrupted translation frames as pseudogenes, increasing its "missed" count compared to Prodigal [15].

The superior performance of Prodigal in these benchmarks, particularly its higher peptide support (most peptides mapping wholly inside its predictions), has led major sequencing centers like the DOE Joint Genome Institute to adopt it for reannotating public genomes in the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) system [15].

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in Annotation Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | OncoSpan FFPE (HD832) [17] | Provides well-characterized variants for benchmarking |

| Proteomic Data | PNNL Peptide Database, PRIDE BioMart [15] | Experimental peptide evidence for gene model validation |

| Gene Calling Software | Prodigal, GeneMarkS, Glimmer3 [15] | Ab initio prediction of protein-coding genes |

| Post-Processing Tools | GenePRIMP [15] | Identifies potential annotation errors and improvements |

| Quality Control Tools | CheckM [16] | Assesses annotation completeness and contamination |

| Reference Databases | RefSeq, Ensembl Compara [15] [18] | Provides reference annotations for comparison |

Best Practices for Robust Gene Annotation

Recommendations for Annotation Pipelines

Based on benchmarking evidence, researchers should adopt the following practices to minimize annotation errors:

Implement Multi-Algorithm Consensus Approaches: Using multiple gene finders and taking consensus predictions can improve accuracy, though this must be balanced against potential over-prediction from methods like Glimmer3 that generate more unique calls [15].

Utilize Proteogenomic Validation: Whenever possible, incorporate mass spectrometry data to verify predicted gene models. Despite limitations (average ~40% peptide coverage in benchmarking studies), this provides the most direct experimental evidence for coding regions [15].

Apply Post-Processing Analysis: Tools like GenePRIMP can identify and correct potential annotation errors, demonstrating lower total error rates than standalone ab initio predictors in benchmarking [15].

Maintain Consistency in Comparative Studies: When comparing across genomes, apply the same annotation method throughout. As one benchmarking study concluded, "any of these methods can be used by the community, as long as a single method is employed across all datasets to be compared" [15].

Future Directions in Gene Annotation Benchmarking

The field continues to evolve with several promising developments:

Integration of Diverse Evidence: Future benchmarks will increasingly incorporate RNA-Seq data alongside proteomic evidence to capture transcript boundaries and validate splice sites [15].

Machine Learning Advancements: While currently more prominent in eukaryotic gene prediction, discriminative models like support vector machines and conditional random fields show promise for improving prokaryotic annotation accuracy [19].

Standardized Benchmarking Platforms: Community resources like OpenProblems offer living, extensible benchmarking platforms that enable ongoing method evaluation as new algorithms emerge [14].

As benchmarking methodologies become more sophisticated and incorporate additional forms of experimental evidence, the accuracy and consistency of automated gene annotation will continue to improve, ultimately enhancing the reliability of genomic databases and enabling more robust comparative studies.

The accurate identification of protein-coding genes is a fundamental step in the annotation of prokaryotic genomes, forming the basis for downstream comparative genomics and metabolic studies. While prokaryotic gene prediction is often considered more tractable than its eukaryotic counterpart due to the absence of introns and higher gene density, significant challenges remain in achieving optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity, particularly for atypical sequences [20] [21]. The landscape of computational tools for this task has evolved from early ab initio methods that rely on statistical signatures within the genome sequence itself, to modern approaches incorporating machine learning and alignment-free identification techniques [22] [23]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of major prokaryotic gene-finding algorithms, including established tools like Prodigal and GeneMarkS, alongside newer contenders such as Balrog and the comprehensive annotation system Bakta. We frame this comparison within the broader context of benchmarking methodologies, presenting consolidated performance data and experimental protocols to assist researchers in selecting appropriate tools for their specific applications in microbial genomics and drug development.

Algorithm Classifications and Core Methodologies

Prokaryotic gene prediction methods can be broadly categorized by their underlying computational strategies. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between these major algorithmic approaches and their representative tools:

Ab Initio Methods

Ab initio (or "from first principles") methods predict genes using intrinsic DNA sequence properties without external evidence. They primarily rely on signal sensors (e.g., ribosome binding sites, start/stop codons) and content sensors (e.g., codon usage, GC frame bias) to distinguish coding from non-coding regions [20] [21]. These tools typically employ probabilistic models like Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) to capture the statistical patterns of coding sequences.

Prodigal (PROkaryotic DYnamic programming Gene-finding ALgorithm): This algorithm employs dynamic programming to identify optimal gene configurations based on a scoring system incorporating GC frame bias, ribosome binding site motifs, and start/stop codon statistics [24]. It builds a training profile for each genome, allowing it to adapt to species-specific characteristics without manual intervention. A key feature is its focus on reducing false positives, even at the cost of missing some genuine short genes [24] [22].

GeneMarkS: This suite uses self-training HMMs to identify coding regions. The "S" variant employs an iterative process to refine its model parameters specific to the input genome, improving accuracy across diverse taxonomic groups [22] [21]. Like Prodigal, it must be retrained for each new genome, which can be computationally demanding for large-scale projects.

Modern and Hybrid Approaches

Recent developments have introduced new paradigms that address limitations of traditional ab initio methods.

Balrog (Bacterial Annotation by Learned Representation Of Genes): This tool represents a shift toward universal protein models. It utilizes a temporal convolutional network trained on a vast and diverse collection of microbial genomes to create a single, generalized model of prokaryotic genes [22] [25]. A significant advantage is that Balrog does not require genome-specific training, making it suitable for fragmented metagenomic assemblies.

Bakta: While primarily a comprehensive annotation pipeline, Bakta's gene-finding core leverages Prodigal but enhances it with a sophisticated, alignment-free sequence identification (AFSI) system [26] [27] [23]. Bakta computes MD5 hash digests of predicted protein sequences and queries them against a precompiled database of known proteins from RefSeq and UniProt. This allows for rapid, precise assignment of database cross-references and helps validate predictions. Furthermore, Bakta implements a specialized workflow for detecting small open reading frames (sORFs) that are often missed by standard gene callers due to length cut-offs [23].

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

Benchmarking Methodology

Rigorous benchmarking of gene finders requires standardized datasets and evaluation metrics. A typical protocol involves:

- Test Genome Curation: A diverse set of high-quality finished genomes, often from public repositories like RefSeq, is selected. To avoid bias, genomes used in the training of any universal model (e.g., Balrog) must be excluded from the test set [22].

- Ground Truth Establishment: The "true" gene set for evaluation can be derived from trusted sources, such as manually curated annotations (e.g., Ecogene for E. coli) or a consensus from multiple annotation pipelines [24] [22].

- Metric Calculation: Standard performance metrics are calculated for each tool:

- Sensitivity: The proportion of known, true genes that are correctly predicted by the tool. A gene is often considered correctly predicted if its 3' end (stop codon) matches the reference [22].

- Specificity: The ability to avoid predicting false positives. This is often inferred by the total number of "hypothetical protein" predictions, as a lower number of total predictions while maintaining high sensitivity suggests higher specificity [22].

- Runtime and Computational Resources: The wall-clock time and memory (RAM) required for annotation.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of the major tools, synthesized from published benchmarks.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Prokaryotic Gene Prediction Tools

| Tool | Algorithm Type | Training Requirement | Sensitivity to Known Genes | Specificity (Relative False Positives) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prodigal | Ab initio (Dynamic Programming) | Genome-specific | ~99% [22] | Moderate (Baseline) | Fast, robust, widely adopted, good start codon identification [24] [22] |

| GeneMarkS | Ab initio (HMM) | Genome-specific | High (~99%) [21] | Comparable to Prodigal | High accuracy across diverse GC content [21] |

| Balrog | Universal Model (Neural Network) | None (Pre-trained) | Matches or exceeds Prodigal [22] | Higher (Fewer overall/hypothetical predictions) [22] | No per-genome training, better for metagenomes, reduced false positives |

| Bakta | Hybrid (Prodigal + AFSI) | None for AFSI DB | Retains Prodigal's sensitivity [23] | Higher (via AFSI validation & sORF detection) [23] | Integrated annotation, DB cross-references, sORF detection, FAIR outputs |

Analysis of Key Trade-offs

- Sensitivity vs. Specificity: While tools like Prodigal and GeneMarkS achieve near-perfect sensitivity for known genes, they also predict a large number of "hypothetical proteins." Balrog demonstrates that it is possible to maintain this high sensitivity while reducing the total number of predictions, which suggests a reduction in false positives [22].

- Generality vs. Specificity: Genome-specific training allows tools like Prodigal to fine-tune to a particular organism's signatures. In contrast, universal models like Balrog sacrifice this fine-tuning for broad applicability and speed, yet benchmarks show they can perform equally well [22].

- Comprehensiveness: Most pure gene finders only predict coding sequences. Bakta, as an annotation suite, provides a more complete picture by also annotating non-coding RNAs, CRISPR arrays, regulatory sites, and origins of replication, making it a more turn-key solution for full genome annotation [26] [23].

Successful gene prediction and genome annotation rely on a suite of computational tools and databases. The following table details key resources referenced in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Prokaryotic Genome Annotation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Annotation |

|---|---|---|

| Prodigal | Software Tool | Core ab initio gene prediction algorithm [24]. |

| Balrog | Software Tool | Universal, pre-trained gene finder based on a neural network [22] [25]. |

| Bakta | Software Tool | Comprehensive annotation pipeline that uses Prodigal and alignment-free identification [26] [27]. |

| RefSeq | Database | Curated database of reference sequences used for validation and AFSI [23]. |

| UniProt (UniRef) | Database | Comprehensive protein sequence database used for homology searches and functional assignment [23]. |

| AntiFam | Database | Hidden Markov model database used to filter out spurious, false-positive ORFs (e.g., shadow ORFs) [23]. |

| tRNAscan-SE | Software Tool | Specialized tool for predicting tRNA genes, often integrated into pipelines like Bakta [23]. |

| Infernal | Software Tool | Tool for searching DNA sequence databases using covariance models (e.g., for rRNA/ncRNA prediction) [23]. |

| AMRFinderPlus | Software Tool | Expert system for precise annotation of antimicrobial resistance genes [23]. |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure reproducible and objective comparisons, the following workflow outlines a standard protocol for benchmarking gene prediction tools, as applied in several studies cited in this guide [28] [22].

Step 1: Input Genome Curation Select a diverse set of 20-50 complete bacterial and archaeal genomes from a reliable source like RefSeq. The set should cover a wide range of GC content and phylogenetic lineages. For a rigorous test, ensure no genome in this set was part of the training data for any universal model being evaluated [22].

Step 2: Run Gene Prediction Tools Execute all gene finders (e.g., Prodigal, Balrog, Bakta) on the curated genome set using default parameters. For tools requiring training (e.g., GeneMarkS), ensure the self-training process is completed for each genome. Record computational resource usage (time and memory) for each run.

Step 3: Establish Ground Truth Obtain a high-confidence set of genes for each test genome. This can be the manually curated annotations available for model organisms (e.g., E. coli K-12) or a set of genes with strong homology evidence and functional characterization from multiple databases [24] [22]. Separate "known" genes (those with a functional assignment) from "hypothetical" ones for more nuanced analysis.

Step 4: Parse and Compare Outputs Extract the coordinates of predicted genes (start, stop, strand) from the output files of each tool (e.g., GFF, GBK formats). Use custom scripts or comparison software to map these predictions to the ground truth gene set. A prediction is typically considered a true positive if its stop codon matches the reference, though some benchmarks use more stringent criteria requiring both start and stop accuracy [22].

Step 5: Calculate Performance Metrics For each tool and each genome, calculate:

- Sensitivity: (True Positives) / (All Known Genes in Ground Truth)

- Total Genes Predicted: The raw count of all CDSs predicted.

- Hypothetical Proteins: The count of predicted genes labeled as "hypothetical protein." A tool that produces fewer hypotheticals while maintaining high sensitivity is considered to have higher specificity [22].

- Runtime and Memory Usage: Average values across all genomes to assess computational efficiency.

In the field of prokaryotic genomics, the accurate identification of genes is a foundational step upon which virtually all downstream biological analyses are built. These analyses, which can range from metabolic pathway reconstruction to drug target identification, are entirely dependent on the quality of the initial genome annotation. Error propagation refers to the phenomenon where mistakes introduced at this initial stage—whether from sequencing, assembly, or gene prediction—are carried forward, compounding and distorting subsequent biological interpretations. This article demonstrates why rigorous benchmarking of bioinformatics tools is not merely an academic exercise, but an essential practice to ensure the reliability of genomic research and its applications.

The Error Propagation Pathway in Genomic Analysis

The process of moving from raw sequence data to biological insight involves multiple, interconnected steps. An error at any stage can be amplified in subsequent stages. The diagram below outlines this critical pathway and the points where errors are most likely to be introduced and propagated.

A Comparative Benchmark: Prokaryotic Gene Annotation Tools

The choice of gene annotation tool significantly impacts the quality of the resulting gene set. Large-scale evaluations provide the empirical data needed to make an informed selection. A recent investigation of four prominent open-source annotation tools across 156,033 diverse genomes offers a clear comparison of their performance in different contexts [32].

Table 1: Large-Scale Performance of Prokaryotic Annotation Tools

| Tool | Best For | Strengths | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bakta | High-quality bacterial genomes [32] | Excelled in standard bacterial genome annotation [32] | Performance may vary for non-standard genomes [32] |

| PGAP | Archaeal, MAGs, fragmented, or contaminated samples [32] [31] | Broader functional term (GO) coverage; robust on challenging genomes [32] [31] | Integrated NCBI pipeline using curated HMMs and complex domain architectures [31] |

| EggNOG-mapper | Functional Annotation [32] | Provides more functional terms per feature [32] | A functional annotation tool often used in conjunction with structural predictors |

| Prokka | Rapid annotation [32] | Not specified in detail | Included in large-scale evaluation for comparison [32] |

This benchmarking data highlights a critical point: there is no single "best" tool for all scenarios. The optimal choice depends on the genome quality, taxonomy, and origin (e.g., Metagenome-Assembled Genomes or MAGs) [32]. For instance, while one tool may be superior for a clean, high-quality bacterial isolate, another may outperform it when dealing with the complexities of an archaeal genome or a fragmented MAG.

Consequences of Annotation Errors on Downstream Analysis

Incorrect gene predictions directly compromise the validity of subsequent research. The following table details the specific consequences of common annotation errors.

Table 2: Impact of Gene Annotation Errors on Downstream Analyses

| Type of Annotation Error | Direct Consequence | Impact on Downstream Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Translation Initiation Site (TIS) [24] | N-terminally truncated or extended protein sequence | Misunderstanding of signal peptides and protein localization; incorrect functional domain mapping |

| Over-prediction of False Positive Genes [24] | A large number of short genes with no homology | Dilution of real signals in transcriptomic/proteomic studies; wasted resources on validating non-existent genes |

| Failure to Annotate Small Plasmids [30] | Incomplete repertoire of accessory genes | Overlooked antibiotic resistance or virulence factors, with severe implications for clinical microbiology and drug development |

| Inconsistent Functional Annotation [32] [31] | Assigning different Gene Ontology (GO) terms or EC numbers to orthologous genes | Inaccurate metabolic model reconstruction and flawed comparative genomics studies |

Benchmarking Methodologies: How Comparisons Are Made

Understanding how tools are evaluated is key to interpreting benchmarking studies. The following experimental protocols are commonly employed.

Protocol for Benchmarking Gene-Finding Algorithms

The accuracy of gene prediction tools like Prodigal, Glimmer, and GeneMark is typically assessed by comparing their predictions to a "gold standard" set of curated genes [24]. Key steps include:

- Training Set Curation: Using a set of genomes with expertly curated gene starts and stops to establish ground truth [24].

- Accuracy Metrics: Measuring the sensitivity (ability to find real genes) and specificity (ability to avoid false positives) for both gene and TIS identification [24].

- GC Content Challenges: Testing performance across genomes with varying GC content, as high GC genomes contain more spurious ORFs and present a greater challenge [24].

Protocol for Benchmarking Long-Read Assemblers

Since assembly quality directly impacts annotation, benchmarking assemblers is a related and crucial endeavor. A comprehensive study evaluated eight long-read assemblers (Canu, Flye, Miniasm, etc.) using 500 simulated and 120 real read sets [33] [30].

- Diverse Inputs: Using a wide variety of genomes and read parameters (depth, length, identity) to test robustness [30].

- Prokaryote-Focused Assessment: Assemblies were evaluated on structural completeness, sequence identity, contig circularization, and computational resources, with special attention to plasmid assembly [30].

- Ground Truth: For real read sets, high-quality hybrid (Illumina-long-read) assemblies were used as a reference to avoid circular reasoning [30].

The Researcher's Toolkit for Prokaryotic Annotation

This table details essential resources and their roles in the genome annotation and benchmarking workflow.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Prokaryotic Genomics

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance to Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| Prodigal | Prokaryotic dynamic programming gene-finding algorithm [24] | A widely used tool that is often a baseline in performance comparisons due to its speed and accuracy [24] [32] |

| NCBI PGAP | Integrated pipeline for annotating bacterial and archaeal genomes [31] | Provides a standardized, evidence-based annotation system; a benchmark for functional annotation breadth [32] [31] |

| CheckM | Tool for assessing the completeness and contamination of genomes [31] | Used post-annotation to estimate the quality of the annotated gene set [31] |

| QUAST | Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies [33] | Evaluates assembly quality, which is a critical prerequisite for accurate gene annotation [33] |

| Curated Gold Standard Sets | Expert-curated genomes with validated gene structures (e.g., Ecogene [24]) | Essential as a ground truth for objectively measuring the accuracy of gene prediction tools [24] |

| TIGRFAMs & HMMs | Curated databases of protein families and hidden Markov models [31] | Used by pipelines like PGAP for high-quality functional annotation; a benchmark for model-based function prediction [31] |

| Cbdvq | Cbdvq, MF:C19H24O3, MW:300.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The path from a prokaryotic genome sequence to a biological discovery is paved with complex computational steps, each susceptible to errors that can propagate and mislead. As the comparative data shows, the performance of bioinformatics tools is highly context-dependent. Relying on a single tool or an unvalidated pipeline poses a significant risk to the integrity of downstream analyses, potentially derailing research efforts and resource allocation in drug development and basic science. Therefore, rigorous, large-scale benchmarking is not an optional supplement but an essential component of robust genomic research. It is the primary safeguard against the insidious and costly consequences of error propagation.

Designing a Rigorous Benchmarking Study: From Datasets to Metrics

In the field of prokaryotic genomics, the accurate identification of genes is a foundational step for downstream analyses, from functional annotation to drug target discovery. The development of computational tools for this task relies heavily on rigorous benchmarking, the cornerstone of which is the selection of appropriate datasets. Broadly, bioinformaticians choose between two principal types of benchmark data: simulated data, generated in silico with known properties, and real data, derived from sequencing experiments, sometimes accompanied by a ground truth established through gold-standard methods. The choice between these data types profoundly influences the assessment of a gene finder's performance, strengths, and limitations. Framed within the broader thesis of benchmarking gene-finding algorithms for prokaryotes, this guide provides an objective comparison of these two approaches, detailing their trade-offs and providing actionable protocols for researchers.

Simulated Data vs. Real Data with Ground Truth: A Conceptual Comparison

The core distinction between simulated and real data lies in the control over the "answer key." The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Benchmark Dataset Types

| Feature | Simulated Data | Real Data with Ground Truth |

|---|---|---|

| Data Origin | Computer-generated via simulation algorithms [28] | Empirical data from sequencing platforms (e.g., ONT, PacBio) [28] |

| Ground Truth | Perfectly known and controllable [28] | Established via experimental validation (e.g., N-terminal sequencing) or high-confidence hybrid assemblies [28] [34] [35] |

| Primary Advantage | Enables controlled stress-testing of specific variables (e.g., error profiles, read depth); unlimited supply [28] [35] | Reflects the full complexity and noise of real biological systems; ultimate test of practical applicability [35] |

| Primary Limitation | May not fully capture the complex error profiles and biases of real sequencing data [35] | Limited availability and scale of experimentally verified data; costly and time-consuming to produce [34] [35] |

| Ideal Use Case | Initial algorithm development, parameter sensitivity analysis, and large-scale scalability testing [28] | Final performance validation and assessment of real-world readiness [34] |

Quantitative Comparison of Dataset Performance

Benchmarking studies reveal that the choice of dataset directly impacts the performance metrics of gene-finding tools. The following table synthesizes findings from key studies comparing tool performance on simulated versus real data.

Table 2: Impact of Dataset Type on Algorithm Performance Assessment

| Benchmarking Context | Performance on Simulated Data | Performance on Real Data with Ground Truth | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Read Assemblers [28] | Some assemblers (e.g., Redbean, Shasta) showed high computational efficiency but a higher likelihood of incomplete assemblies. | The same assemblers demonstrated reliability issues on real datasets, with performance varying significantly based on the specific isolate and sequencing platform. | Performance on simulated data does not always translate directly to real-world scenarios, highlighting the risk of over-optimization for idealized conditions. |

| Gene Start Prediction [34] | Not the primary focus for final validation. | Tools like Prodigal, GeneMarkS-2, and PGAP showed discrepancies in start codon predictions for 15-25% of genes in a genome. | The absence of a large, verified ground truth for gene starts makes it difficult to resolve these discrepancies, underscoring the value of limited real validation sets. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Simulators [36] | Simulation methods were evaluated on their ability to recapitulate properties of real data using metrics like KDE test statistics. | The "ground truth" for real data was based on experimental data properties and known tissue structures. | Comprehensive benchmarking frameworks use both property estimation (against real data) and downstream task performance to evaluate simulators. |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Protocol for Benchmarking with Simulated Data

Using simulated data allows for systematic evaluation under controlled conditions. The following workflow, based on established practices in prokaryotic genomics [28], outlines a robust protocol.

Detailed Methodology:

Reference Genome Curation: Download a comprehensive set of bacterial and archaeal genomes from a trusted source like RefSeq. Apply stringent quality control filters to remove genomes with overly large or small chromosomes, exceptionally large plasmids, or an excessive number of plasmids. Finally, employ a dereplication tool to ensure genomic uniqueness, resulting in a diverse and non-redundant set of reference genomes (e.g., 500) that serve as the known truth [28].

In silico Read Simulation: Use a modern read simulation tool like Badread to generate sequencing reads from the curated reference genomes. To ensure a comprehensive test, parameters such as read depth, length, and per-read identity should be varied randomly across the different datasets. For genomes containing plasmids, it is critical to simulate the plasmid read depth relative to the chromosome, modeling the known biological variation where small plasmids can have high copy numbers [28].

Tool Execution and Evaluation: Execute the gene-finding or assembly tools on the simulated read sets using default parameters. The resulting assemblies or gene predictions are then compared back to the original reference genomes from which the reads were simulated. Key performance metrics include structural accuracy/completeness (e.g., are all replicons assembled?), sequence identity (nucleotide-level accuracy), and computational resource usage (runtime and memory) [28].

Protocol for Benchmarking with Real Data and Ground Truth

When available, real data with a high-confidence ground truth provides the most authoritative benchmark. The protocol below leverages hybrid sequencing approaches and experimental data to establish this truth [28] [34] [35].

Detailed Methodology:

Data Acquisition and Curation: Source real sequencing datasets from public repositories or collaborations. These should ideally include data from multiple platforms (e.g., Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Pacific Biosciences, and Illumina) for the same biological isolate. For gene-start prediction, seek out studies that have performed N-terminal protein sequencing or other experimental validation methods, which provide the most reliable ground truth [34] [35].

Establishing a Robust Ground Truth: For genomic assembly, a high-confidence ground truth can be computationally constructed using a hybrid assembly approach. This involves using a tool like Unicycler to combine highly accurate short reads (Illumina) with long reads to scaffold and correct the assembly. The resulting assembly is considered a reliable ground truth only if independent hybrid assemblies (e.g., using different long-read technologies) show near-perfect agreement, minimizing circular reasoning [28]. For gene starts, the ground truth is the set of experimentally verified start codons [34].

Tool Validation and Analysis: Run the benchmarking tools on the real sequencing data (e.g., the long-read subsets only). Compare the outputs—predicted genes or assembled contigs—against the established ground truth. The analysis should focus on metrics that matter in practice, such as the discrepancy rate in gene start predictions or the ability to fully resolve chromosomes and plasmids without structural errors [28] [34].

Successful benchmarking requires a suite of computational tools and data resources. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experimental protocols.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Benchmarking

| Research Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Badread [28] | Simulates long-read sequencing data with customizable error profiles and read lengths. | Generating realistic but controlled simulated read sets for initial algorithm testing and stress-testing. |

| Unicycler [28] | A hybrid assembly pipeline that integrates short and long reads to produce high-quality finished genomes. | Establishing a computational ground truth for real datasets when experimental validation is not available. |

| GeneMarkS-2 [34] | An ab initio gene finder that uses self-training to model various translation initiation signals in prokaryotes. | A key tool for comparison in gene-finding benchmarks; can be used to generate predictions for real data. |

| Prodigal [34] | A fast and widely used ab initio gene-finding tool for prokaryotic genomes. | Serves as a standard comparator in gene prediction performance evaluations. |

| StartLink/StartLink+ [34] | Alignment-based algorithms for predicting gene starts by leveraging conservation patterns across homologs. | Used to resolve discrepancies between ab initio gene finders and improve gene start annotation accuracy. |

| RefSeq Database [28] | A curated collection of reference genomic sequences from the NCBI. | Source of high-quality reference genomes for simulation and for comparative analysis during benchmarking. |

| Experimentally Verified Gene Sets [34] | Collections of genes with starts confirmed by methods like N-terminal sequencing. | Provides the highest-quality ground truth for validating gene start prediction tools on real data. |

The selection between simulated data and real data with ground truth is not a matter of choosing a superior option but of understanding their complementary roles in a robust benchmarking pipeline. Simulated data offers scale, control, and the ability to probe specific algorithmic weaknesses in a cost-effective manner, making it ideal for the early and middle stages of tool development. Conversely, real data with a strong ground truth provides the ultimate litmus test for real-world applicability, capturing the full complexity of biological systems and sequencing artifacts. A comprehensive benchmarking thesis for prokaryotic gene finders must therefore leverage both approaches: using simulated data for wide-ranging stress tests and scalability analyses, and reserving precious real datasets with experimental validation for final, authoritative performance assessment. By adhering to the detailed protocols outlined in this guide, researchers can ensure their evaluations are both thorough and credible, ultimately accelerating the development of more reliable genomic tools for the scientific community.

Essential Guidelines for Neutral and Unbiased Benchmarking Design

In the field of prokaryotic genomics, the development of sophisticated algorithms for tasks such as gene finding and genome assembly has accelerated dramatically. Tools like Prodigal for gene prediction and assemblers like Flye and Canu for long-read data have become fundamental to biological research and its applications in drug development [24] [30]. However, the true value and limitations of these tools can only be understood through rigorous, neutral, and unbiased benchmarking studies. Such studies empower researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select the most appropriate tools for their specific projects, ensuring the reliability of their foundational genomic data.

The necessity of robust benchmarking is highlighted by the fact that different algorithms often produce conflicting results. For instance, in gene start site prediction—a critical determination for understanding protein sequences and regulatory regions—major algorithms like Prodigal, GeneMarkS-2, and the NCBI PGAP pipeline disagree for a significant percentage of genes, with disagreement rates rising to 15-25% in GC-rich genomes [34]. Without standardized, objective benchmarks, navigating these discrepancies is challenging. This guide synthesizes principles and methodologies from authoritative benchmarking studies to establish a framework for the neutral and unbiased evaluation of bioinformatics tools, using prokaryotic gene-finding algorithms as a primary context.

Foundational Principles of Neutral and Unbiased Benchmarking

Effective benchmarking is not merely about comparing output; it is a structured process designed to minimize bias and provide a fair assessment of tool performance. The following core principles are non-negotiable.

- Neutrality and Transparency: The study design must not favor any particular tool. All tools should be given an equal opportunity to perform well. This includes using the same computational resources, the same input data, and the same version of any underlying databases. The criteria for evaluation must be established before the benchmark is conducted and be clearly stated in the publication [30].

- Use of Ground Truth Data: The accuracy of a tool can only be measured against a known standard. For gene finding, this involves using datasets with experimentally verified gene starts, even if these sets are limited in size [34]. For assemblers, the ground truth is the known reference genome from which sequencing reads were derived [30]. For simulated data, the ground truth is the original genome used for the simulation [30].

- Comprehensive and Diverse Test Sets: A tool's performance on one genome or one data type is not predictive of its overall utility. Benchmarking must use a wide variety of test data, encompassing different organisms with varying genomic features (e.g., GC content, ploidy), different sequencing technologies (e.g., Oxford Nanopore, PacBio, Illumina), and different data qualities (e.g., varying read depths and error profiles) [30] [34]. This reveals strengths and weaknesses that might otherwise remain hidden.

- Assessment of Multiple Performance Metrics: No single metric can capture all aspects of tool performance. A comprehensive benchmark evaluates multiple, often competing, metrics. For example, a gene finder should be assessed on both sensitivity (ability to find all real genes) and specificity (ability to avoid false positives) [24]. For assemblers, key metrics include structural accuracy, sequence identity, contig circularization, and computational resource usage (runtime and RAM) [30].

Experimental Design and Methodologies for Benchmarking Gene-Finding Algorithms

Curating High-Quality Reference Datasets

The foundation of any benchmark is a reliable reference dataset. Two primary types are used:

- Experimentally Verified Gene Sets: These provide the highest confidence ground truth for evaluating predictions like translation initiation sites. These datasets are constructed using methods such as N-terminal protein sequencing and mass spectrometry [34]. While highly accurate, they are limited in size; one study used a total of 2,841 verified genes from five species (E. coli, M. tuberculosis, R. denitrificans, H. salinarum, and N. pharaonis) [34].

- Expert-Curated Genomes: These are genomes where gene models have been meticulously reviewed and validated by human experts, often through a pipeline that combines computational predictions with homology evidence and manual curation. The development of Prodigal, for instance, utilized genomes curated by the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) and included well-annotated genomes like Escherichia coli K12 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [24].

The following table summarizes key reagents and datasets essential for benchmarking in this field.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Datasets for Benchmarking

| Item Name | Type | Brief Function in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| Ecogene Verified Protein Starts [24] | Verified Gene Set | Provides experimentally validated translation start sites for E. coli K12, serving as a gold standard for evaluating start codon prediction accuracy. |

| NCBI RefSeq Genome Database [30] [37] | Genomic Data Repository | A comprehensive source of prokaryotic genomes used for selecting diverse test sequences and for training machine learning models in tools like MetaPathPredict. |

| Prodigal (Algorithm) [24] | Gene-Finding Tool | A widely used, ab initio gene prediction algorithm that serves as a key baseline or subject for performance comparison in benchmarking studies. |

| GeneMarkS-2 (Algorithm) [34] | Gene-Finding Tool | A self-trained gene finder that uses multiple models for upstream regions; used as a comparator to Prodigal and other tools. |

| StartLink/StartLink+ [34] | Gene Start Prediction Tool | An algorithm that uses multiple sequence alignments of homologs to infer gene starts, providing an orthogonal method to validate or challenge ab initio predictions. |

| CheckM [31] | Assessment Tool | Used to estimate the completeness and contamination of an annotated gene set, providing a quality control metric for the output of gene finders and assemblers. |

Quantitative Comparison of Algorithm Performance

A robust benchmark requires a head-to-head comparison of tools across a diverse set of genomes. The following table synthesizes data from a large-scale comparison of gene start predictions, illustrating how performance can vary.

Table 2: Comparative Gene Start Prediction Disagreements Across Genomes [34]

| Genome GC Content Bin | Average Percentage of Genes per Genome with Mismatched Starts | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Low GC Genomes | ~7% | Disagreement between Prodigal, GeneMarkS-2, and NCBI PGAP is relatively low. |

| Medium GC Genomes | ~10-15% | Disagreements become more frequent as GC content increases. |

| High GC Genomes | ~15-25% | Prediction accuracy drops considerably, leading to the highest rates of disagreement between tools. |

Standardized Workflow for a Benchmarking Experiment

A reproducible benchmarking experiment follows a structured workflow to ensure fairness and consistency. The diagram below outlines the key stages, from data preparation to final analysis.

Graphical representation of the standardized benchmarking workflow.

The workflow consists of the following critical stages:

- Data Selection & Curation: Select a diverse set of input genomes or sequences. This includes high-quality reference genomes with expert curation and, when possible, genes with experimentally verified starts [24] [34]. For assembler benchmarks, this also involves generating or obtaining real and simulated read sets with known ground truth genomes [30].

- Tool Configuration: Install and configure all tools to be benchmarked. It is critical to ensure that all tools are run with comparable settings and on identical hardware to prevent resource-based advantages from skewing results. Using the same version of any underlying databases is also essential [30].

- Unified Execution: Run all selected tools on the curated datasets using a standardized computational environment. This step often requires significant computational resources, especially for large datasets or complex tools like assemblers [30].

- Performance Metric Calculation: Analyze the outputs of each tool against the ground truth data to calculate quantitative performance metrics. For gene finders, this includes sensitivity, specificity, and translation initiation site accuracy [24] [34]. For assemblers, this includes structural accuracy, sequence identity, and contig circularization [30].

- Result Analysis & Reporting: Synthesize the calculated metrics into a comprehensive comparison. This involves creating clear tables and figures, identifying statistical significance, and discussing the strengths and weaknesses of each tool in different scenarios [30] [34].

Case Study: Benchmarking Long-Read Assemblers for Prokaryotes

A seminal study by Wick and Holt provides an exemplary model of rigorous benchmarking, evaluating eight long-read assemblers (Canu, Flye, Miniasm/Minipolish, NECAT, NextDenovo/NextPolish, Raven, Redbean, and Shasta) [30]. This study adhered to the core principles outlined above:

- Diverse Data: The authors used 500 simulated read sets (generated with Badread) and 120 real read sets, covering a wide variety of genomes and read parameters [30].

- Multiple Metrics: Assemblies were assessed on structural accuracy/completeness, sequence identity, contig circularization, and computational resource usage (runtime and RAM) [30].

- Clear Findings: The study found that no single tool performed best on all metrics. For example, Flye was reliable and made small sequence errors but used the most RAM. Miniasm/Minipolish was most likely to produce clean contig circularization, while Raven was reliable for chromosome assembly but struggled with small plasmids [30]. This nuanced conclusion helps users select a tool based on their specific priorities.