Beyond RMSD: The Global Distance Test as an Essential Tool for Protein Model Evaluation in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Global Distance Test (GDT), a critical metric for evaluating protein structure predictions. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore GDT's foundational principles, its methodological application in community-wide assessments like CASP, strategies to overcome its computational challenges and limitations, and a comparative analysis with other metrics such as RMSD and TM-score. The article also examines GDT's pivotal role in validating breakthrough AI tools like AlphaFold, underscoring its growing importance in accelerating structure-based drug design and biomedical research.

Beyond RMSD: The Global Distance Test as an Essential Tool for Protein Model Evaluation in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Global Distance Test (GDT), a critical metric for evaluating protein structure predictions. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore GDT's foundational principles, its methodological application in community-wide assessments like CASP, strategies to overcome its computational challenges and limitations, and a comparative analysis with other metrics such as RMSD and TM-score. The article also examines GDT's pivotal role in validating breakthrough AI tools like AlphaFold, underscoring its growing importance in accelerating structure-based drug design and biomedical research.

What is the Global Distance Test? Understanding the Core Metric of Protein Structure Assessment

The Global Distance Test (GDT) is a fundamental metric for quantifying the similarity between two protein three-dimensional structures. In the field of computational biology, it serves a critical role in assessing the quality of predicted protein models by comparing them to experimentally determined reference structures, such as those solved by X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy [1]. The GDT was developed to address limitations of earlier metrics like Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), which is highly sensitive to small, outlier regions that are poorly modeled and can therefore underestimate the quality of a prediction that is largely accurate [1] [2]. The most common version of the metric, the GDT_TS (Total Score), is reported as a percentage, where a higher score indicates a closer match between the model and the reference structure [1].

Within the ecosystem of structural bioinformatics, GDTTS is not just an academic metric; it is a major assessment criterion in the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments [1] [3]. These blind community-wide experiments are the gold standard for evaluating the state of the art in protein structure prediction. The central role of GDTTS in CASP, and its adoption in continuous benchmarks like CAMEO, underscores its importance in driving methodological progress and validating new approaches, including the latest deep learning-based predictors like AlphaFold [1] [4] [5].

Core Concept and Calculation of GDT

The Fundamental Principle

At its core, the GDT algorithm aims to find the largest set of amino acid residues (specifically, their Cα atoms) in a model structure that can be superimposed onto the corresponding residues in a reference structure within a defined distance cutoff [1]. The process involves iteratively superimposing the two structures to maximize this set of matched residues. The underlying computational challenge is formalized as the Largest Well-predicted Subset (LWPS) problem, which seeks the optimal rigid transformation (rotation and translation) that maximizes the number of residue pairs under a given bottleneck distance, d [2]. Although this problem was once conjectured to be NP-hard, it has been shown to be solvable in polynomial time, albeit with algorithms that can be computationally intensive for practical use [2].

The GDT_TS Calculation Protocol

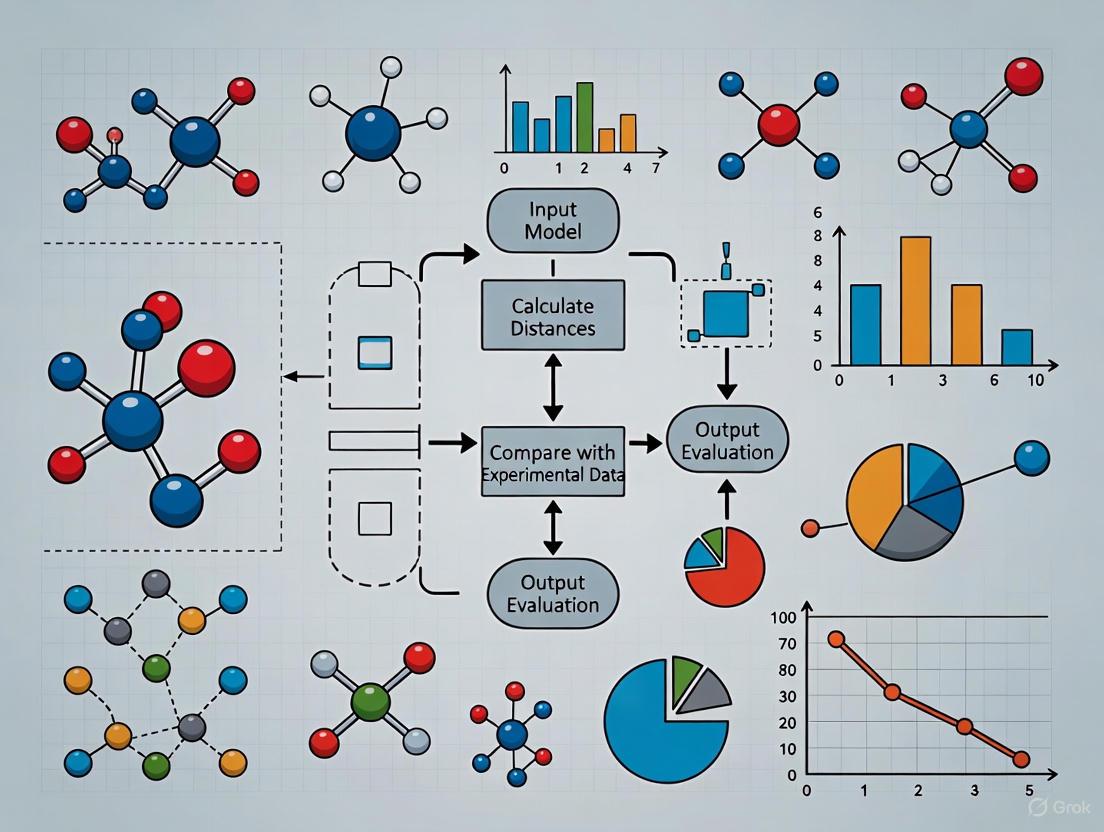

The conventional GDT_TS score is not based on a single distance cutoff but is an aggregate measure designed to provide a balanced view of a model's accuracy at different spatial scales. The calculation proceeds through a well-defined protocol, illustrated in the workflow below.

The standard GDT_TS score is the average of the percentages of matched Cα atoms under four specific distance cutoffs: 1, 2, 4, and 8 Ångströms [1]. This multi-threshold approach ensures that the score reflects both high-accuracy local fits (captured by the 1Å and 2Å cutoffs) and the overall global fold similarity (captured by the 4Å and 8Å cutoffs). The original GDT algorithm calculates scores for 20 consecutive distance cutoffs from 0.5Å to 10.0Å, providing a detailed profile, but the average of the four key cutoffs has been standardized for CASP reporting [1].

Table: Key Distance Cutoffs in GDT_TS Calculation

| Distance Cutoff (Ã…) | Structural Feature Assessed | Role in GDT_TS |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Ã… | Very high local atomic-level accuracy | Assesses near-experimental precision |

| 2 Ã… | High local backbone accuracy | Captures well-predicted core regions |

| 4 Ã… | Correct global fold topology | Evaluates overall structural fold |

| 8 Ã… | General tertiary structure similarity | Ensures correct domain packing |

GDT in Experimental and Evaluation Protocols

Standardized Assessment in CASP and CAMEO

The GDTTS metric is embedded within the experimental protocols of major international benchmarks. In CASP, predictors submit blind models for recently solved but unpublished protein structures. The organizers then use GDTTS as one of the primary metrics to rank the performance of different methods [1] [3]. Similarly, the CAMEO platform performs continuous, automated evaluation of prediction servers using weekly releases of new structures, also relying on GDTTS for quality assessment [4] [6]. The use of GDTTS in these independent, blind tests provides a rigorous and unbiased evaluation of a prediction method's real-world performance.

A Practical Toolkit for Researchers

To effectively work with and evaluate protein structures using GDT, researchers utilize a suite of software tools and resources.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for GDT Analysis

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in GDT Context |

|---|---|---|

| LGA (Local-Global Alignment) [1] | Software Program | The original and reference method for calculating GDT scores via structural superposition. |

| OpenStructure [4] | Software Library | Used by tools like ModFOLDdock2 to compute underlying scores (e.g., lDDT, CAD) for quality assessment. |

| OptGDT [2] | Software Tool | An algorithm designed to find nearly optimal GDT scores with theoretical accuracy guarantees, addressing heuristic limitations. |

| CASP/ CAMEO Datasets [6] | Benchmark Data | Standardized sets of target structures and predictions for validating and comparing new MQA methods. |

| AlphaFold2/3 [4] [5] | Prediction Method | High-accuracy structure prediction systems whose outputs are routinely evaluated using GDT_TS in benchmarks. |

| Arabidopyl alcohol | Arabidopyl Alcohol|RUO | Arabidopyl alcohol is a natural product from Betula pendula bark for research use. For Research Use Only. Not for human or diagnostic use. |

| N1-Propargylpseudouridine | N1-Propargylpseudouridine|High-Purity | N1-Propargylpseudouridine is a modified nucleotide for RNA research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or therapeutic use. |

Variations and Advanced Extensions of GDT

The success of the core GDT_TS metric has led to the development of several specialized variants to address specific assessment needs. The relationships between these different GDT-related metrics are illustrated below.

- GDTHA (High Accuracy): This variant uses smaller distance cutoffs (typically half the size of those used in GDTTS) to more stringently assess models that are expected to be of very high quality. It was introduced in CASP7 to better differentiate between top-performing predictions [1].

- GDC (Global Distance Calculation) Extensions: To move beyond the Cα backbone, the GDCsc score uses a predefined "characteristic atom" near the end of each residue's side chain for evaluation. The GDCall variant represents the most comprehensive assessment, incorporating full-model information by considering all atoms [1] [7]. These extensions are crucial for evaluating the accuracy of side chain packing, which is vital for understanding protein function and for applications like drug design.

- Algorithmic Improvements: Tools like OptGDT have been developed to compute GDT scores with theoretically guaranteed accuracies, overcoming potential underestimation from heuristic methods used by earlier programs. In tests on CASP8 data, OptGDT improved GDT scores for 87.3% of models, with some improvements exceeding 10% more matched residues [2].

The Evolving Role of GDT in the Age of Deep Learning

The advent of highly accurate structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3 has transformed the field, with many predicted models now reaching near-experimental accuracy [4] [5]. This shift has not made GDT obsolete but has refined its role. As the performance ceiling has been raised, the ability of GDT_TS to discriminate between the very best models has become increasingly important. Furthermore, the focus of the field is expanding from monomeric tertiary structures to protein quaternary structures (complexes) [4]. In this context, integrated assessment servers like ModFOLDdock2 use hybrid consensus approaches that incorporate GDT-like metrics, such as Oligo-GDTJury, to evaluate the global and local interface quality of predicted complexes [4].

While GDTTS remains a cornerstone for global structural comparison, it is often used in conjunction with other metrics to provide a more complete picture. The local Distance Difference Test (lDDT), for example, is a more recent local stability measure that does not require superposition and is increasingly used alongside GDTTS in benchmarks [4] [6]. The continued evolution of the GDT metric family ensures it will remain an indispensable component of the model quality assessment toolkit, providing critical, quantitative insights for researchers in computational biology, structural bioinformatics, and drug development.

In the fields of structural biology and computational drug discovery, the accurate evaluation of protein structure models is as crucial as their prediction. For decades, the root mean square deviation (RMSD) served as the predominant metric for quantifying structural similarity. However, as protein structure prediction has been revolutionized by deep learning approaches like AlphaFold2, the limitations of RMSD have become increasingly apparent, necessitating more sophisticated evaluation frameworks [8]. The Global Distance Test (GDT) was developed specifically to address these limitations, providing a more robust and biologically meaningful assessment of structural quality [1]. This technical guide examines the fundamental shortcomings of RMSD and demonstrates how GDT provides a superior framework for model evaluation within the broader context of structural bioinformatics research.

RMSD: Historical Context and Inherent Limitations

The RMSD Calculation and Its Sensitivities

Root mean square deviation calculates the square root of the average squared distances between corresponding atoms in two superimposed protein structures. For two structures A and B, each containing N atoms, the RMSD is mathematically defined as:

$$ \text{RMSD} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N}\mathbf{r}i^2} $$

where $\mathbf{r}i = \mathbf{a}i - \mathbf{b}_i$ represents the displacement vector between corresponding atoms [9].

Despite its widespread adoption, RMSD suffers from significant limitations that impact its reliability for comprehensive structure evaluation:

Sensitivity to Outliers: RMSD is dominated by the largest errors in a structure, meaning that a small number of poorly predicted regions can disproportionately inflate the score, even when the remainder of the structure is accurately modeled [10] [1].

Length Dependency: The interpretation of RMSD values varies significantly with protein size. For example, an RMSD of 3Ã… represents a poor model for a small protein of 10 residues but may indicate reasonable accuracy for a large protein of 100 residues [2].

Global vs. Local Accuracy: RMSD provides a single global measure that fails to distinguish between structures with widespread small errors and those with excellent local accuracy but a few severe errors [10].

Table 1: Interpreting RMSD Values in Protein Structure Comparison

| RMSD Value | Interpretation | Structural Implications |

|---|---|---|

| <2Ã… | High accuracy | Structures are highly similar or nearly identical |

| 2-4Ã… | Medium accuracy | Moderate similarity; acceptable depending on resolution requirements |

| >4Ã… | Low accuracy | Structures differ significantly; only global elements may be comparable |

Case Study: RMSD Limitations in Conformational Change Analysis

The practical implications of RMSD's limitations become evident when comparing protein conformational states. For example, active and inactive conformations of estrogen receptor α differ primarily by the movement of a single helix (H12). Despite this localized change, global backbone RMSD values can be virtually indistinguishable from pairs of albumin structures exhibiting multiple smaller-scale rearrangements [10]. This demonstrates how RMSD fails to distinguish between different types of structural variations, potentially masking biologically relevant conformational changes.

The Global Distance Test: A Robust Alternative

GDT Fundamentals and Calculation

The Global Distance Test was developed specifically to overcome RMSD's limitations. Rather than providing a single average distance measure, GDT identifies the largest set of amino acid residues (typically Cα atoms) in a model structure that fall within defined distance cutoffs of their positions in a reference structure after optimal superposition [1].

The conventional GDT_TS (Total Score) calculates the percentage of residues within four distance thresholds (1Ã…, 2Ã…, 4Ã…, and 8Ã…) and reports the average:

$$ \text{GDT_TS} = \frac{\text{GDT}{1Ã…} + \text{GDT}{2Ã…} + \text{GDT}{4Ã…} + \text{GDT}{8Ã…}}{4} $$

This multi-threshold approach provides a more nuanced view of structural accuracy across different spatial scales [1].

GDT Score Interpretation and Variants

GDT scores range from 0-100%, with higher values indicating greater structural similarity. The protein structure prediction community has established general interpretation guidelines for GDT scores:

Table 2: Interpretation of GDT Scores in Model Quality Assessment

| GDT Score Range | Interpretation | Model Quality |

|---|---|---|

| >90% | High accuracy | Model closely matches reference structure |

| 50-90% | Medium accuracy | Acceptable depending on research focus |

| <50% | Low accuracy | Model likely contains significant inaccuracies |

Several GDT variants have been developed for specific assessment scenarios:

GDTHA (High Accuracy): Uses stricter distance cutoffs (typically half those of GDTTS) to more stringently evaluate high-quality models [1].

GDC_SC (Global Distance Calculation for Sidechains): Extends the assessment to side chain atoms using characteristic atoms for each residue type [1].

GDC_ALL (Global Distance Calculation for All Atoms): Incorporates full atomic representation for comprehensive evaluation [1].

Comparative Analysis: RMSD vs. GDT in Practical Applications

Performance in Community-Wide Assessments

The Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) has adopted GDT as a primary evaluation metric since CASP3, reflecting its superior performance in assessing model quality [1]. Traditional RMSD-based methods employ heuristic strategies that often result in underestimated similarity scores. Research has demonstrated that optimal GDT score calculation can improve the number of matched residue pairs by at least 10% compared to traditional methods for over 87% of predicted models [2].

The fundamental difference lies in their approach to structural alignment: while RMSD minimization seeks the transformation that minimizes average atomic displacements, GDT optimization seeks the transformation that maximizes the number of residues within a defined distance threshold, making it less sensitive to outlier regions [2].

Application in Experimental Structure Validation

GDT's robustness extends beyond computational prediction to experimental structure validation. In nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, where proteins exhibit inherent flexibility, GDT provides a more meaningful measure of agreement with experimental data than RMSD. Studies have shown that structural models with lower GDT scores to an NMR reference structure may sometimes be better fits to the underlying experimental data than those with higher scores, highlighting the importance of considering protein flexibility in assessment [1].

Implementation and Integration in Modern Structural Biology

GDT in the Deep Learning Era

With the advent of deep learning-based structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2, accurate model evaluation has become increasingly important. While these tools regularly produce high-quality predictions, assessment metrics like GDT remain essential for identifying subtle errors, particularly in multi-domain proteins and flexible regions [11] [8].

Recent advancements, such as Distance-AF, which incorporates distance constraints to improve AlphaFold2 predictions, demonstrate how GDT-like principles are now being integrated directly into structure prediction pipelines [11] [12]. This approach reduced RMSD to native structures by an average of 11.75Ã… compared to standard AlphaFold2 models on challenging targets, highlighting the continued relevance of distance-based assessment in guiding model refinement [12].

Complementary Metrics for Comprehensive Evaluation

While GDT addresses many RMSD limitations, a comprehensive structural assessment typically employs multiple complementary metrics:

TM-score: A normalized measure that accounts for protein size, with values between 0-1 where scores >0.5 indicate the same fold [13].

LDDT (Local Distance Difference Test): Assesses local accuracy independent of global superposition, making it particularly valuable for evaluating structures with domain movements [13].

Table 3: Protein Structure Comparison Metrics and Their Applications

| Metric | Type | Key Characteristics | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD | Global | Simple calculation; sensitive to outliers | Quick comparisons of highly similar structures |

| GDT | Global | Multiple distance thresholds; robust to outliers | Overall model quality assessment; CASP evaluations |

| TM-score | Global | Size-normalized; fold-level assessment | Detecting structural relationships |

| LDDT | Local | Superposition-independent; per-residue scores | Local quality assessment; residue-level accuracy |

Research Reagent Solutions for Structural Evaluation

Table 4: Essential Tools for Protein Structure Evaluation and Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| LGA (Local-Global Alignment) | Software | Calculates GDT scores and performs structure alignment | Primary tool for GDT computation in CASP |

| PSVS (Protein Structure Validation Suite) | Software Suite | Comprehensive validation using multiple quality scores | Integrated structure validation for NMR and computational models |

| OptGDT | Algorithm | Computes GDT scores with theoretically guaranteed accuracy | High-precision assessment for benchmarking studies |

| FoldSeek | Software | Fast structural comparison and alignment | Large-scale structural database searches |

| spyrmsd | Python Library | Symmetry-corrected RMSD calculations | Ligand docking evaluation and conformer comparison |

The development and adoption of the Global Distance Test represents a significant advancement in protein structure evaluation methodology. By addressing the critical limitations of RMSD—particularly its sensitivity to outlier regions and inability to distinguish between local and global accuracy—GDT has established itself as an essential component of structural bioinformatics research. Its multi-threshold approach provides a more nuanced and biologically relevant assessment of model quality, which has been instrumental in driving progress in protein structure prediction, particularly through community-wide initiatives like CASP. As the field continues to evolve with new deep learning approaches and increasingly complex structural challenges, GDT and its variants remain foundational tools for rigorous, informative model evaluation that effectively bridges computational predictions and biological insights.

In the field of computational structural biology, the quantitative assessment of protein models is paramount. The Global Distance Test (GDT), particularly its GDT_TS variant, employs a set of standardized distance cutoffs—1, 2, 4, and 8 Ångstroms—to measure the similarity between a predicted protein structure and an experimentally determined reference. This technical guide delves into the fundamental role these specific thresholds play in model evaluation research. We explore the biophysical and practical rationales behind this graduated scale, which collectively balances the need for high-accuracy detection with the pragmatic acceptance of local structural deviations. The application of these cutoffs in major community-wide experiments like CASP (Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction) has standardized the field, enabling robust comparisons between modeling methodologies. Furthermore, the principles of using distance thresholds to quantify spatial relationships extend beyond model assessment into experimental techniques such as Double Electron-Electron Resonance (DEER) spectroscopy and the analysis of ion-pair interactions in proteins. This review provides an in-depth analysis of these thresholds, summarizes relevant quantitative data, and details experimental protocols that leverage distance constraints, framing it all within the critical context of evaluating protein structural models.

The Global Distance Test (GDT) is a cornerstone metric for quantifying the similarity between two protein three-dimensional structures, most commonly used to compare computational models against experimentally-solved reference structures [1]. Unlike the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD), which can be disproportionately skewed by a small number of outlier residues, the GDT metric was specifically designed to provide a more robust and global measure of structural accuracy [1]. The most common implementation, known as GDT_TS (Total Score), is calculated as the average of the largest sets of amino acid Cα atoms from the model that can be superimposed onto the reference structure under four defined distance cutoffs: 1, 2, 4, and 8 Ångstroms [1].

The selection of this specific set of thresholds is not arbitrary; it represents a carefully considered gradient of spatial precision that captures different aspects of model quality. The stricter cutoffs (1 Ã… and 2 Ã…) identify regions of very high local accuracy, where the model is virtually indistinguishable from the target. The more lenient cutoffs (4 Ã… and 8 Ã…) capture the broader, global topology of the fold, even in regions that may have undergone shifts, rotations, or contain flexible loops that are difficult to model with atomic precision. This multi-scale approach allows GDT_TS to present a single, comprehensive score that reflects both the local and global quality of a structural model. Its adoption as a primary assessment criterion in the Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments has cemented its role in driving progress in the field of protein structure prediction [1].

The utility of distance thresholds in structural biology is not confined to GDT-based model evaluation. For instance, in DEER (Double Electron-Electron Resonance) spectroscopy, a powerful technique for probing conformational heterogeneity, distance distributions between spin labels in the 15-80 Ã… range are measured to resolve unique protein conformations [14]. Similarly, in the analysis of protein stability and design, the geometry of ion pairs (salt bridges) is classified based on distances between charged atoms, with interactions often categorized as salt bridges, nitrogen-oxygen (NO) bridges, or longer-range ion pairs based on 4 Ã… distance criteria [15] [16]. Thus, the GDT_TS cutoffs exist within a broader landscape where specific distance thresholds are used to define, classify, and quantify structural features and interactions.

The Biophysical and Practical Rationale for Standard Cutoffs

The graduated scale of the GDT_TS cutoffs is designed to capture a complete picture of a model's accuracy, from atom-level precision to the correct overall fold. Each threshold provides unique insight, and together they offer a balanced assessment that penalizes both global topological errors and local structural inaccuracies.

1 Ångstrom Cutoff: This is an extremely stringent threshold, demanding near-atomic precision. A Cα atom fitting under this cutoff indicates that the local backbone conformation is modeled with exceptional accuracy. This level of precision is crucial for applications where detailed atomic interactions are important, such as in computational drug discovery or enzymatic mechanism studies. However, requiring this level of accuracy across an entire protein is often unrealistic due to the inherent flexibility of proteins and limitations in current modeling techniques.

2 Ã…ngstrom Cutoff: This threshold remains a marker of high accuracy. It allows for minor deviations in atomic positions while still signifying a correctly modeled local structure. Regions fitting under this cutoff are considered highly reliable. In practice, the 1 Ã… and 2 Ã… cutoffs are often analyzed together to evaluate the high-accuracy core of a protein model.

4 Ångstrom Cutoff: This is a structurally significant cutoff. A Cα atom within 4 Å of its true position typically indicates that the local secondary structure (e.g., alpha-helix, beta-sheet) is correctly placed. This threshold begins to capture the global fold of the protein, forgiving small shifts or rotations of rigid elements while ensuring the overall topology is correct.

8 Ã…ngstrom Cutoff: This lenient threshold captures the overall topological similarity. It identifies residues that are in approximately the correct region of the protein fold, even if their local geometry has significant errors. A model with a high score at 8 Ã… but low scores at stricter cutoffs likely has the correct overall fold but poor local accuracy. This is critical for determining if a model, even if imperfect, can be used for functional inference or to identify distant evolutionary relationships.

The following table summarizes the structural interpretation and significance of each standard cutoff in GDT_TS analysis.

Table 1: Structural Significance of GDT_TS Ã…ngstrom Cutoffs

| Cutoff (Ã…) | Structural Interpretation | Primary Evaluation Focus |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Ã… | Near-atomic precision; local backbone is exceptionally accurate. | Ultra-high local accuracy |

| 2 Ã… | High local accuracy; minor deviations allowed, structure is highly reliable. | High local accuracy |

| 4 Ã… | Correct placement of secondary structure elements; global topology is captured. | Local structure & global topology |

| 8 Ã… | Overall fold is correct; residues are in the approximate correct region. | Global topological similarity |

The power of using this combination of thresholds lies in its ability to provide a nuanced view. For example, a model may have a high 8 Å score, indicating the correct fold, but a low 1 Å score, revealing a lack of atomic-level detail. This guides researchers on the model's suitability for different tasks—whether for understanding broad functional categories or for detailed mechanistic studies. The GDTHA (High Accuracy) metric, which uses smaller cutoffs (typically 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 Å), was developed for CASP to more heavily penalize larger deviations and distinguish between top-performing models where standard GDTTS saturates [1].

Quantitative Data and Application in Model Evaluation

In practice, GDTTS scores are reported as a percentage from 0 to 100, where a higher score indicates a better match to the reference structure. The calculation involves an iterative process of superimposing the model onto the target and finding the largest set of Cα atoms that fall within each distance cutoff. The final GDTTS is the average of these four percentages.

The interpretation of GDTTS scores is well-established in the community. Generally, a GDTTS score above 50 is considered to indicate that the two structures share the same fold, with scores above 90 typically reserved for highly accurate models with only very minor deviations [17]. The performance of modern protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2 is often demonstrated by their high GDT_TS scores across a wide range of targets.

The critical role of these thresholds is highlighted by their use in evaluating next-generation structural alignment tools. For instance, a 2024 study on GTalign, a novel algorithm for rapid protein structure alignment and superposition, used the standard GDT cutoffs as a primary benchmark. The study demonstrated that GTalign could identify a larger number of structurally similar protein pairs (i.e., with TM-score ≥ 0.5, a related metric) compared to other aligners like TM-align, by more accurately determining the optimal spatial superposition as measured under these standard distance thresholds [17].

Table 2: Example GDT Score Interpretation Guide (as used in community assessments like CASP)

| GDT_TS Score Range | Qualitative Interpretation | Typical CASP Model Category |

|---|---|---|

| 90 - 100 | Very high accuracy; near-experimental quality. | High Accuracy |

| 70 - 90 | Good overall accuracy; correct fold with some local errors. | Competitive |

| 50 - 70 | Medium accuracy; correct global fold but significant local errors. | Same Fold (Correct) |

| 30 - 50 | Low accuracy; incorrect or significantly distorted fold. | Incorrect Fold |

| 0 - 30 | Very low similarity to the target structure. | Incorrect Fold |

The TM-score, another widely used metric for structural similarity, is closely related to GDT. It is designed to be a length-independent measure, and like GDT, it relies on calculating the fraction of residues under a distance cutoff after optimal superposition, though it uses a variable threshold [17]. The continued development and benchmarking of structural bioinformatics tools against these established distance-based metrics underscore their foundational importance.

Experimental Protocols Leveraging Distance Constraints

Protocol 1: GDT_TS Calculation with LGA

The following protocol outlines the standard method for calculating GDT_TS scores between a predicted model and an experimental reference structure using the Local-Global Alignment (LGA) program, the original and most commonly used software for this purpose [1].

Primary Research Reagent Solutions:

- Software: LGA program package.

- Input Data: Two protein structure files in PDB format: one for the computational model and one for the reference structure.

- System: Unix/Linux command-line environment.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Ensure both the model and reference structure files are in the correct PDB format. The sequences should be aligned, meaning the residue correspondences are known (typically, the sequences are identical in CASP-like assessments).

- Software Execution: Run the LGA program from the command line. A typical command for GDTTS calculation is:

The

-d:4.0flag sets one of the distance cutoffs for analysis, but the standard GDTTS calculation is an integral part of LGA's output. - Output Analysis: The LGA output provides a detailed report. The key line for GDTTS is typically labeled "GDTpercent" and lists the percentages of residues under the 1, 2, 4, and 8 Ã… cutoffs, followed by the average of these four values, which is the GDT_TS.

- Interpretation: Analyze the four individual cutoff percentages alongside the total GDT_TS score to understand the distribution of accuracy across the model, from high-precision regions to the broadly correct fold.

The workflow for this structure comparison process is summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: Workflow for GDT_TS Calculation via LGA.

Protocol 2: DEER Spectroscopy for Distance Distributions

DEER spectroscopy provides experimental distance restraints that can be used to validate and refine computational models, creating a direct link to the distance-based philosophy of GDT.

Primary Research Reagent Solutions:

- Spin Label: (1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-Δ3-pyrroline-3-methyl) methanethiosulfonate (commonly known as MTSL).

- Buffer: Suitable protein buffer, often deuterated and with a cryoprotectant like glycerol-d8 for low-temperature measurements.

- Equipment: Pulsed EPR spectrometer (e.g., Q-band).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: a. Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Introduce cysteine residues at two specific sites in the protein of interest. b. Protein Expression and Purification: Express and purify the mutant protein. c. Spin Labeling: Incubate the protein with MTSL to covalently attach the spin label to the cysteine thiol groups. d. Sample Preparation for EPR: Concentrate the labeled protein and transfer into a quartz EPR tube.

- DEER Data Collection: a. Perform the four-pulse DEER experiment at cryogenic temperatures (typically 50-80 K) to measure the dipolar coupling between the two spin labels. b. The recorded signal is a dipolar evolution time trace.

- Data Analysis: a. Process the time trace to extract the dipolar coupling function. b. Use model-free analysis methods like Tikhonov regularization to generate a probability distribution of distances between the two spin labels. c. The output is a distance distribution plot spanning approximately 15 to 80 Ã…, which can reveal multiple peaks corresponding to different conformational states of the protein [14].

- Integration with Computational Modeling: a. The experimental distance distributions are used as restraints in modeling frameworks like ProGuide [14]. b. ProGuide uses iterative biased molecular dynamics simulations, comparing the simulated distance distribution (generated using a rotamer library for the spin label) against the experimental DEER target. c. This process drives backbone rearrangements in the protein model until the simulated ensemble recapitulates the experimental distance data.

The logical flow of using DEER-derived distances for computational refinement is illustrated below.

Diagram 2: Integrating DEER Distance Restraints into Model Refinement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Distance-Based Structural Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| LGA (Local-Global Alignment) Software | Standard software for calculating GDT scores between two protein structures. | GDT_TS Calculation [1] |

| MTSL Spin Label | A thiol-reactive nitroxide radical used for site-directed spin labeling in EPR spectroscopy. | DEER Spectroscopy [14] |

| di-4-ANEPPDHQ Dye | A solvatochromic membrane probe used in spectrally-resolved single-molecule localization microscopy to map membrane lipid order based on its environment. | Mapping Membrane Nano-domains [18] |

| chiLife Rotamer Library | A computational tool for modeling the conformational heterogeneity of spin label side chains attached to a protein. | Interpreting DEER Data in ProGuide [14] |

| ProGuide Modeling Framework | A computational framework that uses DEER distance distributions to guide and generate accurate structural models of proteins. | Integrative Modeling [14] |

| WRN inhibitor 4 | WRN inhibitor 4, MF:C16H14N2O5S, MW:346.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (R)-(-)-Ibuprofen-d3 | (R)-(-)-Ibuprofen-d3, MF:C13H18O2, MW:209.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The 1, 2, 4, and 8 Ã…ngstrom cutoffs employed by the Global Distance Test are more than just arbitrary numbers; they are a sophisticated, multi-scale ruler that has become the lingua franca for evaluating protein structural models. Their strength lies in their ability to provide a composite yet interpretable measure of model quality, from atomic-level details to the overall fold. As structural biology continues to be transformed by computational advances, particularly in deep learning-based prediction, the role of robust, standardized evaluation metrics like GDT_TS becomes ever more critical. Furthermore, the parallel use of distance thresholds in experimental biophysics, as exemplified by DEER spectroscopy and ion-pair analysis, demonstrates a unifying principle in structural biology: spatial distance is a fundamental and powerful parameter for understanding, validating, and refining the architecture of biological macromolecules. The continued development of tools that integrate these experimental distance restraints with computational modeling promises to further enhance the accuracy and reliability of protein structures, with profound implications for basic research and drug development.

The Global Distance Test (GDT) represents a cornerstone metric in structural bioinformatics, specifically developed to address critical limitations in existing protein structure comparison methods. Originally conceived by Adam Zemla at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, GDT was introduced to provide a more robust evaluation of protein structure prediction models against experimentally determined reference structures [1]. Its adoption as a primary assessment criterion in the Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments, starting with CASP3 in 1998, has established it as the gold standard for quantifying progress in the protein folding field [1] [19]. This technical guide examines GDT's development, algorithmic foundation, and transformative role in enabling the objective, blind testing that culminated in recent breakthroughs such as AlphaFold2 [19] [5].

Prior to GDT's development, Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) served as the predominant metric for comparing protein structures. However, RMSD suffers from significant limitations that hampered its effectiveness for assessing protein structure predictions, particularly for partially correct models. RMSD is highly sensitive to outlier regions—sections of the model that are poorly predicted and deviate substantially from the reference structure [1] [2]. A single incorrectly modeled loop region could disproportionately inflate the RMSD, thereby underestimating the quality of the remainder of the model. Furthermore, the interpretation of RMSD values is length-dependent, making cross-target comparisons challenging [2].

The establishment of CASP as a community-wide blind experiment created an urgent need for more nuanced evaluation metrics that could fairly assess model quality across diverse prediction scenarios. This need catalyzed the development of GDT, which was specifically designed to measure the largest set of residues that could be superimposed within a defined distance cutoff, thus providing a more forgiving and informative measure of model accuracy, especially for correct topological folds with local errors [1].

Algorithmic Foundation and Calculation Methodology

Core Mathematical Definition

The fundamental problem GDT addresses is the Largest Well-predicted Subset (LWPS) problem. Given a protein structure A (the experimental target), a model B, and a distance threshold d, the objective is to identify the maximum-sized match set of residue pairs and a corresponding rigid transformation (rotation and translation) that minimizes the distance between corresponding Cα atoms [2]. Formally, for a threshold d, GDT identifies a rigid transformation T that maximizes the number of residues i for which the distance |T(B_i) - A_i| ≤ d [2].

The conventional GDT_TS (Total Score) is computed as the average of the percentages of residues (Cα atoms) that can be superimposed under four distance cutoffs after iterative structural alignment:

GDTTS = (GDTP1 + GDTP2 + GDTP4 + GDT_P8) / 4 [1] [20]

Where GDT_Pn denotes the percentage of residues under distance cutoff ≤ n Ångströms.

Computational Implementation and the LGA Program

The original GDT algorithm is implemented within the Local-Global Alignment (LGA) program [1]. The calculation involves an iterative process of structural superposition and residue matching:

- Initialization: Select starting residue pairs as initial correspondence points.

- Superposition: Calculate the optimal rigid transformation that minimizes the RMSD between the selected residue pairs.

- Transformation Application: Apply the transformation to the entire model structure.

- Matching: Identify all residue pairs within the specified distance cutoff.

- Iteration: Use the matched pairs as new starting points and repeat until convergence.

- Multiple Start Points: The process is repeated from various initial alignments, and the transformation yielding the maximum number of matched residues is selected [2].

For comprehensive assessment, the original GDT algorithm calculates scores for 20 consecutive distance cutoffs from 0.5 Ã… to 10.0 Ã… in 0.5 Ã… increments [1]. The GDT_TS score specifically utilizes the 1, 2, 4, and 8 Ã… cutoffs for its average, providing a balanced measure across multiple precision levels.

Table 1: Standard GDT Score Variants and Their Calculation Parameters

| Score Name | Distance Cutoffs Used (Ã…) | Calculation Formula | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDT_TS (Total Score) | 1, 2, 4, 8 | Average of percentages at 4 cutoffs | Standard model accuracy assessment in CASP [1] [20] |

| GDT_HA (High Accuracy) | 0.5, 1, 2, 4 | Average of percentages at 4 cutoffs | High-accuracy category in CASP; more stringent [1] [20] |

| GDC_SC (Side Chains) | 0.5, 1.0, ..., 5.0 | Weighted average: ( \frac{2 \sum{k=1}^{10} (11-k) \cdot GDC_P{0.5k}}{10 \cdot 11} ) | Side chain accuracy evaluation [20] |

| GDC_ALL (All Atoms) | 0.5, 1.0, ..., 5.0 | Weighted average: ( \frac{2 \sum{k=1}^{10} (11-k) \cdot GDC_P{0.5k}}{10 \cdot 11} ) | Full-atom model evaluation [20] |

Figure 1: Computational workflow for GDT score calculation, illustrating the iterative superposition and matching process implemented in the LGA program.

Integration with CASP and Historical Evolution

Adoption as a Primary Assessment Metric

GDT was first introduced as an evaluation standard in CASP3 (1998), following its development to address RMSD's limitations in handling partially correct models [1] [2]. The metric quickly became established as a principal assessment criterion due to its ability to provide a more comprehensive and forgiving measure of model quality, which was particularly valuable for evaluating the emerging template-based and free-modeling methodologies of the time.

The CASP experiment provided the ideal testing ground for GDT validation, with its rigorous blind testing protocol and independent assessment structure [21]. The Protein Structure Prediction Center serves as the central repository for CASP results, employing GDT_TS as a primary ranking metric in publicly accessible results tables [22] [20].

Algorithmic Refinements and Response to Community Needs

Throughout successive CASP experiments, the GDT metric has evolved through several variants designed to address specific assessment challenges:

- GDT_HA (High Accuracy): Introduced for CASP7, this variant uses stricter distance cutoffs (0.5, 1, 2, and 4 Ã…) to differentiate between high-quality models in the more accurate template-based modeling category [1] [23].

- GDCSC and GDCALL: These extensions were developed to evaluate side-chain and full-atom accuracy, moving beyond the Cα-only focus of traditional GDT [1] [20].

- TR Score: Introduced in CASP8, this modification subtracted penalties for steric clashes to prevent gaming of the GDT measure through artificially compact models [1].

Table 2: Evolution of GDT Metrics Through CASP Experiments

| CASP Edition | Year | Key GDT-Related Developments | Impact on Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASP3 | 1998 | Introduction of GDT_TS as standard metric [1] | Provided more robust model evaluation than RMSD |

| CASP7 | 2006 | Introduction of GDT_HA for high-accuracy assessment [1] | Enabled differentiation of top-performing models |

| CASP8 | 2008 | Development of TR score and GDC variants [1] | Addressed potential gaming; expanded to side-chain evaluation |

| CASP12-14 | 2016-2020 | Extensive use in documenting deep learning revolution [19] | Quantified extraordinary accuracy improvements (e.g., AlphaFold2) |

Technical Advances and Computational Complexity

Computational Complexity and Optimization

The computation of the optimal GDT score was initially conjectured to be NP-hard, leading to the development of heuristic approaches in the original LGA implementation [2]. However, contrary to this conjecture, research demonstrated that the Largest Well-predicted Subset problem can be solved exactly in polynomial time, albeit with high computational cost (O(nâ·)) that limits practical utility [2].

To address this challenge, approximation algorithms like OptGDT were developed, providing theoretically guaranteed accuracies with more efficient runtime. OptGDT guarantees that for a given threshold d, it finds at least as many matched residue pairs as the optimal solution for a slightly relaxed threshold d/(1+ε), with improved time complexity of O(n³ log n/εâµ) for general proteins and O(n log² n) for globular proteins [2]. Application of OptGDT to CASP8 data demonstrated improved GDT scores for 87.3% of predicted models, with some cases showing improvements of at least 10% in the number of matched residue pairs [2].

Uncertainty Estimation in GDT Scoring

Recent research has addressed the important question of GDTTS uncertainty estimation, recognizing that protein flexibility contributes inherent uncertainty to atomic positions. Studies have quantified GDTTS uncertainty by analyzing structural ensembles from NMR data or generated through time-averaged refinement of X-ray structures [24] [23].

The standard deviation of GDTTS scores increases with decreasing score quality, reaching maximum values of approximately 0.3 for X-ray structures and 1.23 for the more flexible NMR structures [24]. This quantification enables more meaningful comparisons between models with similar GDTTS scores and helps establish statistically significant differences in model quality.

GDT's Role in Documenting the Deep Learning Revolution

The GDTTS metric provided the crucial quantitative framework for measuring the extraordinary progress in protein structure prediction achieved through deep learning approaches. CASP14 (2020) marked a watershed moment, with AlphaFold2 achieving median GDTTS scores that were competitive with experimental structures for a majority of targets [19] [5].

The trend line for CASP14 best models started at a GDTTS of approximately 95 for easy targets and finished at about 85 for the most difficult free-modeling targets, dramatically exceeding performance in previous CASPs and demonstrating that computational predictions could reliably reach experimental accuracy [19]. For approximately two-thirds of CASP14 targets, the best models achieved GDTTS scores above 90, a threshold considered competitive with experimental determination for backbone accuracy [19].

Figure 2: Progression of protein structure prediction accuracy across CASP experiments as quantified by GDT_TS scores, showing the transformative impact of deep learning methodologies.

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Resources for GDT-Based Structure Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| LGA (Local-Global Alignment) | Software Program | Reference implementation for GDT calculation; structural alignment | [1] |

| Protein Structure Prediction Center | Online Database | Repository of CASP results with GDT-based evaluations | predictioncenter.org [22] |

| OptGDT | Software Tool | Computes GDT scores with theoretically guaranteed accuracies | [2] |

| SEnCS Web Server | Online Tool | Estimates GDT_TS uncertainties using structural ensembles | [24] |

| GDTTS, GDTHA, GDC_SC | Assessment Metrics | Standardized scores for backbone, high-accuracy, and side-chain evaluation | [1] [20] |

The development of the Global Distance Test for the Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction represents a seminal advancement in structural bioinformatics. Created specifically to address the limitations of RMSD in evaluating protein structure predictions, GDT has evolved through close integration with the CASP experiment into a sophisticated family of assessment metrics. Its algorithmic development, computational optimization, and uncertainty quantification have provided the rigorous quantitative framework necessary to document one of the most significant achievements in computational biology—the solution of the protein structure prediction problem. As the field progresses toward more challenging targets like multimeric complexes and conformational ensembles, GDT-based metrics continue to provide essential benchmarks for measuring progress in computational structural biology.

From Theory to Practice: Applying GDT in Modern Structural Biology and Drug Discovery

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) is a community-wide, biennial experiment that has objectively tested protein structure prediction methods since 1994 [21]. This blind assessment serves as the definitive benchmark for establishing the state of the art in modeling protein three-dimensional structure from amino acid sequence [22] [21]. CASP functions as a "world championship" in this scientific field, with more than 100 research groups worldwide routinely suspending other research to focus on the competition [21]. The experiment's profound importance was highlighted when Google DeepMind's AlphaFold system, widely considered to have solved the protein structure prediction problem, depended on CASP as the "gold-standard assessment" for the field [25].

Central to CASP's evaluation methodology is the Global Distance Test (GDT), a quantitative measure that compares predicted model α-carbon positions with those in experimentally determined target structures [21]. The GDT score provides an objective, numerical assessment that enables direct comparison of methods across different targets and CASP editions. As Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy Michael Kratsios observed, "What we target is what we measure, and what we measure is what we get more of" [25]. In the context of CASP, the GDT metric has become what the field targets, measures, and consequently improves upon, driving remarkable progress in structural biology over three decades.

The CASP Experimental Framework

The Double-Blind Assessment Protocol

CASP employs a rigorous double-blind protocol to ensure no predictor has prior information about target protein structures [21]. Targets are either structures soon-to-be solved by X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy, or structures recently solved by structural genomics centers and kept on hold by the Protein Data Bank [21]. During each CASP round, organizers post sequences of unknown protein structures on their website, and participating research groups worldwide submit their models within specified deadlines [26]. In the latest CASP15 experiment, approximately 100 groups submitted more than 53,000 models on 127 modeling targets across multiple prediction categories [26].

The CASP organizing committee, including founder and chair John Moult and colleagues from the University of California, Davis, and other institutions, oversees target selection and experimental design [26]. Independent assessors in each prediction category then evaluate the submitted models as experimental coordinates become available, bringing independent insight to the assessment process [26]. This careful separation between prediction and evaluation ensures the objectivity and scientific rigor for which CASP is renowned.

Evolution of CASP Assessment Categories

CASP has continuously adapted its assessment categories to reflect methodological developments and community needs. Table 1 summarizes the core categories in recent CASP experiments.

Table 1: Key CASP Assessment Categories and Their Evolution

| Category | Description | Evolution in CASP |

|---|---|---|

| Single Protein/Domain Modeling | Assesses accuracy of single proteins and domains using established metrics like GDT [26] | Eliminated distinction between template-based and template-free modeling in CASP15; increased emphasis on fine-grained accuracy [26] |

| Assembly | Evaluates modeling of domain-domain, subunit-subunit, and protein-protein interactions [22] [26] | Close collaboration with CAPRI partners; substantial progress expected with deep learning methods [26] |

| Accuracy Estimation | Assesses quality estimation methods for multimeric complexes and inter-subunit interfaces [26] | No longer includes single protein model estimation; increased emphasis on atomic-level self-reported estimates [26] |

| RNA Structures & Complexes | Pilot experiment for RNA models and protein-RNA complexes [26] | Assessment collaboration with RNA-Puzzles and Marta Szachniuk's group [26] |

| Protein-Ligand Complexes | Pilot experiment for ligand binding prediction [26] | High interest due to relevance to drug design; tested on difficult cases with realistic drug-like ligands [27] |

| Contact Prediction | Predicts 3D contacts between residue pairs [22] | Not included in CASP15 despite notable progress in CASP12-13 [22] [26] |

| Refinement | Assesses ability to refine available models toward experimental structure [22] | Dropped in CASP15 [26] |

Recent CASP editions have witnessed a significant evolution in categories, with older categories like refinement and contact prediction being dropped, while new categories for RNA structures, protein-ligand complexes, and protein conformational ensembles have been added [26]. These changes respond to the transformed landscape following the breakthrough success of deep learning methods, particularly AlphaFold2 in CASP14 [26].

The Global Distance Test (GDT): A Technical Examination

Fundamental Principles and Calculation

The Global Distance Test is the primary method for evaluating protein structure predictions in CASP [21]. The GDT score measures the percentage of well-modeled residues in a predicted structure compared to the experimental reference structure. The calculation involves structurally superposing the model onto the target and determining the fraction of Cα atoms (representing residue positions) that fall within a defined distance cutoff of their true positions [21].

The most commonly used variant is GDT-TS (Total Score), which represents the average of four specific distance thresholds: 1Ã…, 2Ã…, 4Ã…, and 8Ã… [21]. This multi-threshold approach provides a balanced assessment that captures both high-precision accuracy (through the tighter thresholds) and overall fold correctness (through the broader thresholds). The mathematical representation can be expressed as:

GDT-TS = (GDTâ‚Ã… + GDTâ‚‚Ã… + GDTâ‚„Ã… + GDT₈Å) / 4

Where each GDTₓÅ represents the percentage of Cα atoms in the model that fall within x Ångströms of their correct positions after optimal superposition.

For high-accuracy assessment, CASP employs GDT-HA (High Accuracy), which uses stricter distance thresholds (0.5Ã…, 1Ã…, 2Ã…, and 4Ã…) to evaluate models that approach experimental resolution [27]. The progression from GDT-TS to GDT-HA in CASP rankings reflects the field's remarkable advances, with AlphaFold2 achieving GDT scores above 90 for approximately two-thirds of targets in CASP14 [22].

GDT Calculation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for calculating GDT scores in CASP assessment:

Complementary Assessment Metrics

While GDT serves as the primary evaluation metric, CASP employs complementary measures to provide comprehensive assessment. These include:

- Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT): A superposition-free score that evaluates local distance differences of all atoms in a model, including side chains [28]. lDDT is particularly valuable for assessing model quality in regions without structural alignment.

- Template Modeling Score (TM-score): A metric that balances local and global structural similarities, with values between 0 and 1, where scores >0.5 indicate generally correct topology [29].

- Interface Contact Score (ICS/F1): Used specifically for evaluating quaternary structure predictions in the assembly category, measuring accuracy at subunit interfaces [22].

- QS-score: A quality measure for interface accuracy in complex structures, employed by assessment tools like DeepUMQA-X [28].

The transition in CASP15 to emphasize pLDDT (predicted lDDT) for self-reported accuracy estimates reflects the increasing importance of local quality assessment alongside global fold metrics like GDT [26].

GDT in Action: CASP Assessment and Progress Measurement

Quantifying Historical Progress Through GDT

The GDT metric has provided the quantitative foundation for measuring decades of progress in protein structure prediction. CASP assessments have documented remarkable improvements, particularly in recent years with the advent of deep learning approaches. In CASP14 (2020), AlphaFold2 achieved an extraordinary increase in accuracy, with models competitive with experimental accuracy (GDTTS>90) for approximately two-thirds of targets and of high accuracy (GDTTS>80) for nearly 90% of targets [22].

The progress in template-based modeling (TBM) has been equally impressive. CASP14 models for TBM targets significantly surpassed the accuracy achievable by simple template transcription, reaching an average GDTTS of 92, substantially higher than previous CASPs [22]. For the most challenging template-free modeling targets, progress has been even more dramatic, with the best models in CASP13 showing more than 20% increase in backbone accuracy compared to CASP12, with average GDTTS scores rising from 52.9 to 65.7 [22].

Recent CASP Results and GDT Performance

The most recent CASP16 experiment continued to demonstrate the dominance of AlphaFold-based approaches, though with important nuances in GDT interpretation [27]. While official rankings use z-scores that amplify differences between methods, the actual GDT_HA values reveal that top-performing methods are often closely clustered [27]. Table 2 summarizes key performance data from recent CASP experiments.

Table 2: GDT Performance in Recent CASP Experiments

| CASP Edition | Key Methodological Advance | Representative GDT Performance | Assessment Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASP13 (2018) | Deep learning with predicted contacts and distances [22] | Average GDT_TS=65.7 for free modeling targets (20% increase from CASP12) [22] | First CASP won by AlphaFold; substantial improvement in template-free modeling [22] [21] |

| CASP14 (2020) | AlphaFold2 end-to-end deep learning [22] | GDTTS>90 for ~2/3 of targets; GDTTS>80 for ~90% of targets [22] | Models competitive with experimental accuracy; extraordinary increase in accuracy [22] |

| CASP15 (2022) | Extension of deep learning to multimeric modeling [22] | Accuracy doubled in Interface Contact Score; 1/3 increase in LDDT for complexes [22] | Enormous progress in multimolecular complexes; new categories introduced [22] [26] |

| CASP16 (2024) | Enhanced sampling (MassiveFold) & AlphaFold3 [27] | All domain folds correct; close GDT_HA clustering among top methods [27] | Domain-level prediction reliability established; challenges remain in complex assembly [27] |

Analysis of CASP16 results revealed that while no protein domain was incorrectly folded—demonstrating remarkable reliability at the domain level—the perception of AlphaFold as "perfect" is inaccurate, with many cases where overall topology is correct but the model contains significant local errors [27]. Furthermore, full-chain modeling of large multidomain proteins and complexes, while showing small improvements over CASP15, remains challenging, particularly for very complex topologies without good templates [27].

Key Software and Servers

The protein structure prediction community relies on specialized software tools and servers for method development and assessment. Table 3 catalogs essential resources frequently employed in CASP-related research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in CASP |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2/3 [27] [29] | End-to-end deep learning | Protein structure prediction from sequence | Top-performing method; baseline for comparisons |

| D-I-TASSER [29] | Hybrid deep learning & physics-based | Protein structure prediction with domain splitting | Outperformed AlphaFold2 on single-domain & multidomain proteins in benchmarks |

| DeepUMQA-X [28] | Quality assessment server | Model accuracy estimation for single-chain & complex models | Top performer in CASP16 EMA blind test across multiple tracks |

| LOMETS3 [29] | Meta-threading server | Template identification & fragment assembly | Component of D-I-TASSER pipeline for template recognition |

| MassiveFold [27] | Large-scale sampling | Extensive model generation with parameter diversity | Provided structural diversity for CASP16 participants; enabled better complex predictions |

| Frama-C [30] | Formal verification | Formal verification of C code specifications | Used in creating verified C code dataset for benchmarking (different CASP acronym) |

Experimental Workflow for Method Development

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for developing and benchmarking protein structure prediction methods for CASP:

Limitations and Future Directions

Current Challenges and GDT Limitations

Despite its established role, the GDT metric has limitations in capturing all aspects of model quality. GDT primarily focuses on Cα positions and may not fully reflect side-chain accuracy or local geometric quality [28]. This limitation has prompted increased use of complementary metrics like lDDT in recent CASPs [26] [28].

Current challenges in the field include accurate modeling of large multidomain proteins and complexes, particularly without good templates [27]. CASP16 found that even with known stoichiometry, modeling of large multicomponent complexes remains difficult [27]. Additionally, while protein-ligand docking using co-folding approaches showed promise in CASP16, affinity prediction performance was notably poor, with some intrinsic ligand properties correlating better with binding than specialized prediction tools [27].

Evolving Assessment Paradigms

The protein structure prediction field is evolving toward more specialized assessments as domain-level prediction becomes increasingly reliable. New frontiers include:

- Conformational ensembles: Predicting alternative conformations and protein dynamics [26]

- Inverse design: Generating sequences with target structural properties [25]

- Functional annotation: Predicting biological function from structure [31]

- Experimental synthesizability: Assessing practical feasibility of proposed structures [25]

The transformative success of CASP has established a blueprint for benchmarking in scientific AI, inspiring similar initiatives like the TELOS program proposal for commissioning AI grand challenges aligned with national priorities [25]. As the field progresses, GDT and related metrics will continue to provide the quantitative foundation for measuring breakthroughs in protein structure modeling and its applications to drug discovery and biotechnology.

The Global Distance Test (GDT) has served as a cornerstone metric in protein structure prediction for over two decades, providing a more robust alternative to Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) for evaluating model quality. This technical guide examines GDT's role in structural biology, detailing its calculation, interpretation across the accuracy spectrum, and application in critical assessments like CASP (Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction). With the advent of deep learning methods such as AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3, GDT scores now routinely exceed 90 for many targets, yet challenges persist for difficult targets with shallow multiple sequence alignments. This whitepaper provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for interpreting GDT scores, incorporating recent advances from CASP16 evaluations and addressing uncertainty quantification to facilitate more nuanced model evaluation in structural biology and drug discovery applications.

The Global Distance Test (GDT), specifically the GDTTS (total score) variant, represents a fundamental metric for quantifying similarity between protein structures with known amino acid correspondences [1]. Developed by Adam Zemla at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, GDT was designed to address limitations of RMSD, which proves overly sensitive to outlier regions that may occur from poor modeling of individual loop regions in otherwise accurate structures [1]. Since its introduction as an evaluation standard in CASP3 (1998), GDTTS has evolved into a major assessment criterion for benchmarking protein structure prediction methods, particularly in the biannual CASP experiments that evaluate state-of-the-art modeling techniques [1] [24].

The significance of GDT in structural biology research stems from its ability to provide a global assessment of model quality that balances local and global features. Unlike RMSD, which can be disproportionately affected by small regions with large errors, GDT measures the largest set of amino acid residues whose Cα atoms fall within defined distance cutoffs after optimal superposition [1]. This approach captures the biological reality that functionally important regions of protein structures often maintain their fold even when peripheral elements deviate substantially. Within the broader thesis of model evaluation research, GDT represents a pragmatic solution to the fundamental challenge of quantifying structural similarity in ways that align with biological significance and practical utility.

Fundamentals of GDT Calculation

Core Algorithmic Principles

The GDT algorithm identifies the largest set of Cα atoms in a model structure that can be superimposed within specified distance thresholds of their positions in a reference (experimentally determined) structure through iterative superposition [1] [32]. The conventional GDT_TS score calculates the average percentage of residues superimposed under four distance cutoffs: 1Å, 2Å, 4Å, and 8Å [1]. The algorithm implementation in tools like LGA (Local-Global Alignment) involves:

- Initialization: Selecting starting points using a sliding window across residue positions

- Iterative superposition: For each window, repeatedly:

- Computing minimal RMSD superposition on the current subset of residue pairs

- Applying the superposition transformation to all model positions

- Calculating pairwise distances between all model and reference positions

- Defining a new subset of residue pairs within the distance threshold

- Convergence check: Continuing until the subset no longer changes

- Maximum identification: Storing the largest subset observed across all iterations and window positions [32]

This method is computationally challenging, with the Largest Well-predicted Subset (LWPS) problem previously conjectured to be NP-hard, though polynomial-time solutions exist with O(nâ·) complexity, making them impractical for routine use [2]. Heuristic approaches like those in LGA and OpenStructure's implementation balance computational efficiency with accuracy, typically achieving results within 2-3 GDT points of optimal values [2] [32].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized GDT calculation workflow as implemented in structural comparison tools:

Interpreting GDT Scores Across the Accuracy Spectrum

Quantitative Interpretation Framework

GDT_TS scores range from 0-100%, with higher values indicating greater similarity to the reference structure [1]. The table below provides a practical framework for interpreting GDT scores across the accuracy spectrum:

| GDT_TS Range | Model Quality Level | Structural Characteristics | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| <50 | Incorrect fold | Limited structural similarity to target; potentially different topology | Limited utility; may help identify completely incorrect predictions |

| 50-70 | Correct fold (low accuracy) | Global topology correct but significant local deviations; domain orientations often incorrect | Identifying overall fold family; low-resolution functional annotation |

| 70-80 | Medium accuracy | Core structural elements well-predicted; loop regions and surface features may deviate | Molecular replacement in crystallography; preliminary drug screening |

| 80-90 | High accuracy | Most structural features accurately predicted; side-chain packing generally correct | Detailed functional analysis; ligand docking studies |

| >90 | Very high accuracy | Minimal deviations from reference; approaching experimental accuracy | Detailed mechanistic studies; rational drug design |

In current CASP assessments, top-performing systems achieve average TM-scores of 0.902 (approximately GDTTS >90) for standard domains, with top-1 predictions reaching high accuracy for 73.8% of domains and correct folds (TM-score >0.5, roughly corresponding to GDTTS >50) for 97.6% of domains [33]. For best-of-top-5 predictions, nearly all domains now achieve correct folds, highlighting the remarkable progress in protein structure prediction [33].

GDT Score Variations and Their Interpretations

Several GDT variants provide specialized assessment for different accuracy regimes:

GDTHA (High Accuracy): Uses smaller distance cutoffs (typically half the size of GDTTS) to more heavily penalize larger deviations [1]. This measure becomes particularly important for evaluating high-accuracy models where distinguishing between excellent and exceptional predictions requires more stringent criteria.

GDC_SC (Global Distance Calculation for Side Chains): Extends GDT-like evaluation to side chain positions using predefined "characteristic atoms" near the end of each residue [1]. This provides crucial information for applications requiring accurate surface representation, such as binding site characterization.

GDC_ALL (Global Distance Calculation for All Atoms): Incorporates full-model information rather than just Cα positions [1]. This comprehensive assessment becomes valuable when evaluating models for detailed structural studies.

The GDT_TS to TM-score relationship provides important interpretive context. While both measure structural similarity, TM-score includes length-dependent normalization that makes it more suitable for comparing scores across proteins of different sizes. As a rough guideline, TM-score >0.5 generally indicates correct topology, while TM-score >0.8 suggests high accuracy [33].

GDT in CASP and Current State of the Art

Evolution of Performance Standards

CASP experiments have tracked remarkable progress in structure prediction methodology, with GDT_TS serving as the primary metric for evaluating tertiary structure prediction accuracy. Recent CASP16 results (2024) demonstrate that integrative systems like MULTICOM4, which combine AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3 with diverse MSA generation and extensive model sampling, can achieve average TM-scores of 0.902 for 84 CASP16 domains [33]. These systems outperformed standard AlphaFold3 implementations, ranking among the top performers out of 120 predictors [33].

The following table summarizes key GDT-related metrics and benchmarks from recent CASP experiments:

| Assessment Metric | Calculation Method | Current Performance Benchmarks | Significance in Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDT_TS | Average of percentages at 1Ã…, 2Ã…, 4Ã…, and 8Ã… cutoffs | >90 for standard single-domain proteins | Primary metric for overall structural accuracy |

| Z-score | Standardized score relative to all predictions | Top predictors: cumulative Z-score ~33 (CASP16) | Normalized performance across multiple targets |

| GDT_HA | Average of percentages at 0.5Ã…, 1Ã…, 2Ã…, and 4Ã… cutoffs | Varies significantly with target difficulty | Distinguishes high-accuracy models |

| GDC_SC | Side chain atom superposition accuracy | Emerging metric with increased importance | Critical for functional site prediction |

Addressing Current Challenges

Despite overall progress, significant challenges remain in protein structure prediction, particularly for targets with:

- Shallow or noisy multiple sequence alignments that provide insufficient co-evolutionary information

- Complicated multi-domain architectures with complex inter-domain interactions

- Intrinsically disordered regions that adopt multiple conformations

- Large macromolecular assemblies where quaternary structure introduces additional constraints [33]

For these difficult targets, the primary challenge often shifts from model generation to model selection, as standard AlphaFold self-assessment scores (pLDDT) cannot consistently identify the best models [33]. Advanced quality assessment methods that combine multiple complementary approaches with model clustering have shown improved ranking reliability [33].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard GDT Calculation Protocol

Research Reagent Solutions for GDT Analysis:

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| LGA (Local-Global Alignment) | Standalone program | Reference implementation of GDT calculation | Download from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory |

| OpenStructure GDT Module | Library component | Integrated GDT calculation within structural biology platform | Import via OpenStructure Python API |

| OptGDT | Optimization tool | Computes nearly optimal GDT scores with theoretical guarantees | Download from University of Waterloo |

| SEnCS Web Server | Online service | Estimates GDT_TS uncertainties using structural ensembles | Access via http://prodata.swmed.edu/SEnCS |

Procedure for Calculating GDT_TS:

Input Preparation:

- Obtain reference structure (experimentally determined by X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM)

- Obtain model structure(s) for evaluation

- Ensure identical amino acid sequences and residue correspondence

Structure Preprocessing:

- Extract Cα atomic coordinates for both structures

- Verify coordinate formats and structural integrity

- Align sequences if necessary to establish residue correspondence

GDT Calculation:

- Implement sliding window approach (typically window size 7)

- For each window position, perform iterative superposition:

- Compute minimal RMSD transformation for current residue subset

- Apply transformation to all model positions

- Calculate distances between all corresponding Cα atoms

- Identify residues within specified distance threshold

- Update residue subset and repeat until convergence

- Track largest subset size across all iterations

Score Computation:

Advanced Protocol: Estimating GDT Uncertainties

Protein flexibility introduces uncertainty into structural comparisons, necessitating methods to estimate GDT_TS confidence intervals:

NMR Ensemble Method:

- Obtain NMR structure ensemble (typically 20+ conformers)

- Calculate GDT_TS between model and each ensemble member

- Compute mean and standard deviation across the ensemble

- Typical uncertainty: SD up to 1.23 for NMR structures [24]

Time-Averaged X-ray Refinement:

- Select high-resolution X-ray structures (resolution <1.8Ã…)

- Perform time-averaged refinement using phenix.ensemble_refinement

- Generate structural ensembles representing conformational diversity

- Calculate GDT_TS across generated ensemble

- Typical uncertainty: SD up to 0.3 for X-ray structures [24]

These methods demonstrate that GDT_TS uncertainty increases for scores below 50 and 70, highlighting the importance of confidence estimation when comparing models with similar scores [24].

The Global Distance Test remains an essential tool for evaluating protein structural models, providing a robust metric that balances local and global accuracy. As protein structure prediction continues to advance, with methods like AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3 achieving high accuracy for most single-chain proteins, the role of GDT is evolving toward addressing more challenging frontiers. These include difficult targets with limited evolutionary information, complex multi-domain proteins, and detailed assessment of side chain positioning.