Building Machine Learning Models for Protein Structure Prediction: From Deep Learning Foundations to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on building machine learning models for protein structure prediction.

Building Machine Learning Models for Protein Structure Prediction: From Deep Learning Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on building machine learning models for protein structure prediction. It explores the foundational principles of protein structure and the deep learning revolution, detailing the architectures of state-of-the-art models like AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold. The content covers practical methodology, from data sourcing to model training, and addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, including handling intrinsically disordered regions and data scarcity. Finally, it outlines rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses of leading tools, synthesizing key takeaways to highlight transformative implications for drug discovery and the understanding of disease mechanisms.

The Protein Folding Problem and the Deep Learning Revolution

Proteins are fundamental biomolecules that perform a vast range of functions within living organisms, from catalyzing metabolic reactions to providing structural support [1]. The functions of proteins are directly connected to their three-dimensional structures, which are organized through a hierarchical framework comprising four distinct levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures [1]. Understanding this architectural organization is crucial for research in structural biology and forms the foundational knowledge required for building accurate machine learning models for protein structure prediction.

The prediction of protein structure from amino acid sequence has been intensely studied for decades, with recent dramatic advances driven by the increasing "neuralization" of structure prediction pipelines [2] [3]. Modern computational approaches, including deep learning systems like AlphaFold2, have achieved remarkable accuracy by leveraging evolutionary information and patterns distilled from known protein structures [4]. This application note details the experimental methodologies for characterizing each level of protein structure, providing the essential groundwork for developing and validating machine learning approaches in structural bioinformatics.

The Four Levels of Protein Structure

Primary Structure: The Amino Acid Sequence

The primary structure is defined as the linear sequence and order of amino acids in a polypeptide chain, connected by peptide bonds [1]. This sequence represents the most fundamental level of structural organization and determines all subsequent levels of protein folding. The primary structure is encoded by the gene sequence and contains all the necessary information that dictates the final three-dimensional conformation of the protein.

Each protein's specific amino acid sequence determines its ultimate properties and function [1]. Even a single amino acid substitution (a point mutation) can result in a non-functional protein or cause disease states, highlighting the critical importance of sequence accuracy [1]. In machine learning applications, the primary structure serves as the primary input feature for sequence-based structure prediction algorithms, with co-evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments providing crucial constraints for model training [4].

Table 1: Key Experimental Methods for Primary Structure Analysis

| Method | Principle | Application in Protein Research |

|---|---|---|

| Edman Degradation | Stepwise removal and identification of N-terminal amino acids | Determines amino acid sequence of purified proteins |

| Mass Spectrometry | Measures mass-to-charge ratio of peptide ions | High-throughput sequencing and post-translational modification identification |

| cDNA Sequencing | Determines nucleotide sequence of protein-coding genes | Infers amino acid sequence from genetic code |

| Amino Acid Analysis | Hydrolyzes protein and quantifies constituent amino acids | Compositional analysis without sequence information |

Secondary Structure: Local Folding Patterns

The secondary structure refers to locally folded, recurring patterns stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the backbone amide hydrogen and carbonyl oxygen atoms of the peptide backbone [1]. These structural elements form the building blocks of protein architecture and primarily include the α-helix and β-sheet conformations.

In the α-helix, the polypeptide backbone twists into a right-handed helical structure, with hydrogen bonds forming between every fourth amino acid, creating a stable, rod-like element [1]. In β-pleated sheets, polypeptide chains (strands) align side-by-side, forming hydrogen bonds between adjacent strands to create a sheet-like structure [1]. These secondary structural elements represent the first level of spatial organization from the linear sequence and provide key intermediate features for machine learning predictors to estimate local structure constraints.

Figure 1: Hierarchical Organization of Protein Structure

Tertiary Structure: Global Three-Dimensional Folding

The tertiary structure represents the overall three-dimensional conformation of a single polypeptide chain, formed through interactions and folding between the various secondary structural elements [1]. This level of organization results from interactions between the R-groups or side chains of amino acids, including hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, disulfide bridges, and ionic interactions.

The tertiary structure brings distant amino acids in the primary sequence into close spatial proximity, creating specific binding sites and catalytic centers essential for protein function [1]. Proteins are categorized as either fibrous (elongated, structural proteins like keratin) or globular (compact, soluble proteins like enzymes) based on their tertiary architecture [1]. Accurate prediction of tertiary structure represents the primary goal of most machine learning systems in structural bioinformatics, with recent methods like AlphaFold2 achieving atomic accuracy rivaling experimental determinations [3].

Table 2: Forces Stabilizing Tertiary Structure

| Stabilizing Force | Strength | Role in Protein Folding |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Interactions | Strong | Drives burial of non-polar residues away from water |

| Hydrogen Bonds | Moderate | Stabilizes secondary structures and side-chain interactions |

| Disulfide Bridges | Strong | Covalent bonds between cysteine residues |

| Ionic Interactions | Moderate | Electrostatic attractions between charged side chains |

| Van der Waals Forces | Weak | Close-range interactions between all atoms |

Quaternary Structure: Multi-Subunit Assembly

The quaternary structure refers to the spatial arrangement of multiple polypeptide chains (subunits) into a functional protein complex [1]. Not all proteins possess quaternary structure; it is exclusively found in proteins consisting of more than one polypeptide chain. The subunits may be identical or different and associate through specific interactions between their surfaces.

Quaternary organization allows for complex regulation and functionality not possible with single subunits, such as allosteric regulation and cooperative binding [1]. In machine learning prediction, quaternary structure presents additional challenges due to the need to model intermolecular interactions, though recent methods are increasingly capable of predicting protein-protein interactions and complex assembly [4].

Experimental Protocols for Structure Determination

Protocol: Protein Purification for Structural Studies

Objective: To obtain highly pure, functional protein suitable for structural characterization.

Materials:

- Cell Lysis Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail

- Chromatography Systems: AKTA FPLC or similar system with UV detection

- Chromatography Resins: Ni-NTA agarose (for His-tagged proteins), ion-exchange media, size-exclusion resins

- Dialysis Membranes: Molecular weight cutoff appropriate for target protein

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend cell pellet in ice-cold lysis buffer (5 mL per gram of cells). Lyse cells by sonication (3 × 30-second pulses on ice) or pressure homogenization.

- Clarification: Centrifuge lysate at 15,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Collect supernatant containing soluble protein.

- Affinity Chromatography:

- Equilibrate Ni-NTA column with 5 column volumes (CV) of binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole).

- Load clarified lysate onto column at 1 mL/min.

- Wash with 10 CV of binding buffer until UV baseline stabilizes.

- Elute with step gradient of elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole).

- Buffer Exchange: Dialyze protein overnight against appropriate storage buffer at 4°C to remove imidazole.

- Concentration Determination: Measure protein concentration using Bradford assay or UV absorbance at 280 nm.

Quality Control:

- Analyze purity by SDS-PAGE (>95% purity required for structural studies)

- Confirm functionality through activity assays if applicable

- Flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C for long-term storage

Protocol: Multi-Sequence Alignment for Machine Learning Input

Objective: To generate a sensitive multiple sequence alignment (MSA) for evolutionary constraint analysis to be used as input for machine learning structure prediction.

Materials:

- Query Protein Sequence: In FASTA format

- Computational Tools: DeepMSA software suite [4], HHblits, Jackhmmer

- Sequence Databases: UniRef90, UniRef30, metagenomic databases

- Computing Resources: High-performance computing cluster with sufficient storage

Procedure:

- Database Search:

- Run HHblits with query sequence against UniRef30 database with 3 iterations

- Use e-value cutoff of 0.001 and minimum sequence coverage of 75%

- Generate profile Hidden Markov Model (HMM) from resulting MSA

- MSA Refinement:

- Execute DeepMSA pipeline to merge sequences from multiple genomic and metagenomic databases [4]

- Perform homologous sequence search using modified Jackhammer/HHsearch

- Reconstruct custom HHblits database for alignment refinement

- Quality Assessment:

- Evaluate MSA depth and diversity using Neff metric (effective number of sequences)

- Check for coverage across entire query sequence length

- Verify presence of homologous sequences with known structures if available

- Output Generation:

- Format MSA for specific prediction algorithm (e.g., AlphaFold2, trRosetta)

- Generate positional conservation scores and co-evolutionary metrics

Applications in ML: The quality of MSA input directly impacts the accuracy of distance predictions between residue pairs, which are used as spatial constraints in neural network training [4]. DeepMSA has been shown to improve contact and secondary structure prediction compared to default pipelines [4].

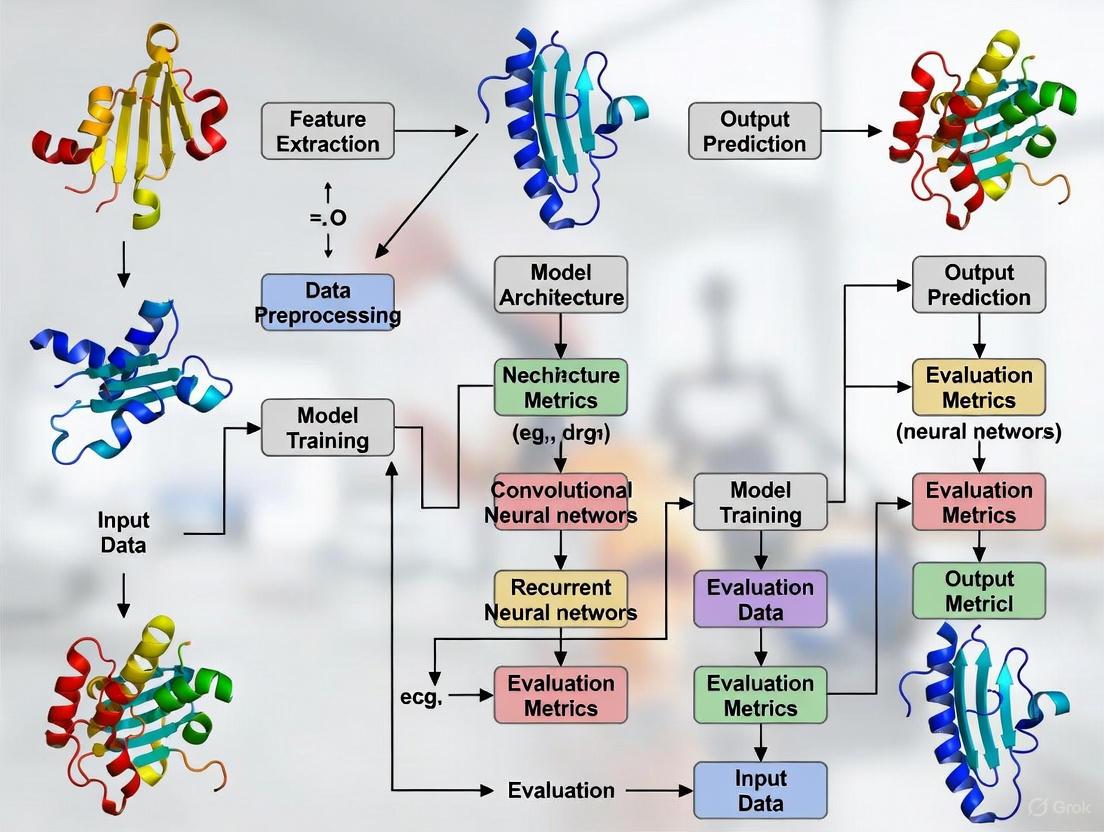

Figure 2: ML Protein Structure Prediction Workflow

Machine Learning Approaches to Structure Prediction

Modern machine learning methods have revolutionized protein structure prediction by replacing traditional energy models and sampling procedures with neural networks [2] [3]. These approaches leverage patterns learned from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments to predict structures with remarkable accuracy.

Deep learning systems like AlphaFold2 employ an end-to-end neural network architecture that directly maps from amino acid sequence to atomic coordinates [3]. The key innovation involves the integration of multiple data sources:

- Evolutionary Information: Physical contacts extracted from the evolutionary record through co-evolutionary analysis [2]

- Sequence-Structure Patterns: Patterns distilled from known structures in the PDB [2]

- Template Incorporation: Structural templates from homologs in the Protein Data Bank [2]

- Refinement Procedures: Neural networks that refine coarsely predicted structures into high-resolution models [2]

These approaches have achieved median accuracies of 2.1 Ã… for single protein domains, enabling a fundamental reconfiguration of biomolecular modeling in the life sciences [2] [3].

Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Structural Biology

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Protein Structure Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2/ColabFold | Deep learning structure prediction | Rapid 3D model generation from sequence [4] |

| trRosetta | Deep residual-convolutional network | Protein structure prediction with distance constraints [4] |

| DeepMSA | Multiple sequence alignment generation | Enhanced evolutionary constraint detection [4] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulation of protein dynamics | Conformational ensemble analysis [4] |

| Unique Resource Identifiers | Standardized reagent identification | Reproducible experimental protocols [5] |

Advanced Applications: Predicting Conformational Ensembles

Proteins exist as dynamic ensembles of multiple conformations rather than single static structures, and these structural changes are often associated with functional states [4]. Recent advances combine machine learning with molecular dynamics simulations to investigate protein conformational landscapes.

Integrated ML/MD Pipeline:

- Distance Distribution Prediction: Use deep learning approaches (e.g., trRosetta) to predict statistical distance distributions between residue pairs from MSA

- Ensemble Generation: Employ distance constraints to generate multiple structural models representing conformational diversity

- Energy Filtering: Filter predicted models based on energy scores from force fields like AWSEM

- Cluster Analysis: Perform RMSD clustering to identify representative conformations

- Validation: Compare predicted ensembles to experimental structures and MD simulations [4]

This integrated approach demonstrates that current state-of-the-art methods can capture experimental structural dynamics, including different functional states observed in crystal structures and conformational sampling from molecular dynamics simulations [4]. The ability to predict multiple biologically relevant conformations has significant implications for drug discovery, as it enables structure-based drug design against different functional states of target proteins.

The hierarchical nature of protein structure—from the linear amino acid sequence to complex multi-subunit assemblies—provides the conceptual framework for understanding protein function and for developing computational prediction methods. Experimental protocols for structure determination yield the foundational data required for training machine learning systems, while biochemical characterization validates computational predictions.

The integration of machine learning with structural biology has created a transformative paradigm in which prediction and experimentation operate synergistically. Deep learning approaches now achieve accuracies that enable reliable structural models for the entire proteome of many organisms, dramatically expanding the structural information available for drug discovery and basic research. As these methods continue to evolve, particularly in predicting conformational ensembles and multi-protein complexes, they will increasingly guide experimental design and accelerate therapeutic development.

The prediction of a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence alone represents one of the most enduring challenges in computational biology. This problem, central to understanding biological function at a molecular level, is framed by two foundational concepts: Anfinsen's dogma and Levinthal's paradox. Christian Anfinsen's Nobel Prize-winning work established that a protein's native structure is determined solely by its amino acid sequence under physiological conditions [6]. This principle suggests that protein structure prediction should be theoretically possible. However, Cyrus Levinthal's subsequent paradox highlighted the computational infeasibility of this task, noting that a random conformational search for even a small protein would take longer than the age of the universe [6] [7].

For decades, these contrasting concepts defined the core challenge of protein folding. The resolution has emerged through sophisticated machine learning approaches that leverage evolutionary information and physical constraints to navigate the vast conformational space efficiently. This document outlines the key theoretical foundations, quantitative benchmarks, and practical protocols for implementing modern protein structure prediction pipelines, with particular emphasis on their application in drug discovery and biomedical research.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

Anfinsen's Dogma: The Thermodynamic Hypothesis

Anfinsen's dogma, also termed the thermodynamic hypothesis, proposes that the native folded structure of a protein corresponds to its global free energy minimum under physiological conditions [6] [8]. This principle implies that all information required for folding is encoded within the protein's amino acid sequence, making computational structure prediction a theoretically solvable problem. This hypothesis formed the foundational motivation for decades of research in computational protein structure prediction.

Levinthal's Paradox: The Kinetic Challenge

In contrast, Levinthal's paradox highlights the practical impossibility of protein folding via a random conformational search. With an estimated 10³â°â° possible conformations for a typical protein, even sampling at nanosecond rates would require time exceeding the universe's age [7] [6]. Levinthal himself proposed that proteins fold through specific, guided pathways with stable intermediate nucleation points—a concept that aligns with modern funnel-shaped energy landscape theory [7].

Resolution Through Machine Learning

Contemporary deep learning approaches effectively bridge these concepts by learning to identify the native structure (Anfinsen's global minimum) without exhaustively sampling all conformations (solving Levinthal's paradox). These methods leverage evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and physical constraints to directly predict plausible low-energy structures [9] [10].

Table 1: Core Concepts in Protein Folding

| Concept | Key Principle | Implication for Structure Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Anfinsen's Dogma | Native structure represents the global free energy minimum [6] | Structure is theoretically predictable from sequence alone |

| Levinthal's Paradox | Random conformational search is kinetically impossible [7] | Requires efficient search strategies to navigate conformational space |

| Folding Funnel | Guided folding through uneven energy landscape [7] | Provides a conceptual framework for iterative refinement in ML models |

| Co-evolutionary Constraints | Spatially proximate residues evolve in a correlated manner [9] | Enables contact/distance prediction from multiple sequence alignments |

Quantitative Advances in Structure Prediction

Performance Benchmarks in CASP Experiments

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments provide the gold-standard benchmark for evaluating prediction accuracy. The progression of results demonstrates the dramatic improvement enabled by deep learning approaches, particularly AlphaFold2 and its successors.

Table 2: Evolution of Prediction Accuracy in CASP Experiments

| CASP Edition (Year) | Leading Method | Median Accuracy (Backbone) | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASP13 (2018) | AlphaFold (v1) | ~3-5 Ã… | Distogram prediction, geometric constraints [10] |

| CASP14 (2020) | AlphaFold2 | 0.96 Ã… (r.m.s.d.95) | End-to-end deep learning, Evoformer, structure module [9] |

| CASP16 (2024) | AlphaFold3 | Near-experimental accuracy | Complex prediction (proteins, nucleic acids, ligands) [11] [12] |

The accuracy achieved by AlphaFold2 in CASP14—with median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å (comparable to the width of a carbon atom)—represented a paradigm shift, making predictions competitive with experimental methods in many cases [9]. Subsequent versions have extended these capabilities to molecular complexes.

Key Metrics for Evaluation

- RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation): Measures the average distance between corresponding atoms in predicted and experimental structures. Lower values indicate better accuracy [9].

- pLDDT (Predicted Local Distance Difference Test): Per-residue confidence score ranging from 0-100, where higher values indicate more reliable predictions [9].

- TM-Score (Template Modeling Score): Global structure similarity measure that is less sensitive to local variations than RMSD [9].

Experimental Protocols for Structure Prediction

End-to-End Prediction with AlphaFold2

Objective: Predict the 3D structure of a protein monomer from its amino acid sequence.

Input Requirements: Amino acid sequence (≥20 residues, ≤2500 residues) in FASTA format.

Procedure:

Multiple Sequence Alignment Generation

Template Identification (Optional)

- Search PDB70 database using HHsearch to identify potential structural templates.

- This step provides additional structural constraints but has minimal impact on final accuracy for most targets [13].

Model Inference

- Process inputs through the Evoformer module to generate a pair representation and processed MSA [9].

- Pass these representations to the structure module that employs an equivariant transformer to iteratively refine atomic coordinates [9] [13].

- Implement 3 cycles of recycling to iteratively refine predictions [9].

- Output: Predicted structure in PDB format, per-residue pLDDT confidence scores, and predicted aligned error.

Model Selection and Validation

- Select the model with highest predicted confidence (pLDDT).

- Interpret pLDDT scores: >90 (very high), 70-90 (confident), 50-70 (low), <50 (very low) [9].

- For low-confidence regions, consider alternative conformations or experimental validation.

Figure 1: AlphaFold2 Protein Structure Prediction Workflow

Template-Free Prediction for Novel Folds

Objective: Predict structures when no homologous templates are available (true de novo prediction).

Input Requirements: Amino acid sequence with no close homologs in PDB.

Procedure:

Advanced MSA Construction

- Employ metagenomic sequencing databases (as implemented in DeepMSA) to detect distant evolutionary relationships [10].

- Use HMM-HMM alignment strategies to capture very remote homology signals.

Alternative Model Selection

- Utilize protein language model-based predictors (ESMfold, OmegaFold) that leverage learned sequence representations instead of explicit MSAs [13].

- These methods trade some accuracy for significantly faster runtimes and can capture structural principles from sequence statistics alone.

Conformational Sampling

- For low-confidence predictions, implement aggressive sampling protocols (e.g., AFSample) that generate diverse decoy structures [13].

- Use AlphaFold2 as an oracle to rank generated decoys by predicted confidence.

Validation Strategies

- Compare predictions from multiple independent methods (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, ESMfold).

- Analyze conserved structural motifs and domain organization for biological plausibility.

- For critical applications, validate low-confidence regions through targeted mutagenesis experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Resources for Protein Structure Prediction Research

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2/3 | Software | End-to-end structure prediction from sequence | AlphaFold2: open source; AlphaFold3: academic use only [12] |

| RoseTTAFold All-Atom | Software | Predict structures of proteins, RNA, DNA and complexes | MIT License (code), non-commercial weights [12] |

| ColabFold | Software | Faster implementation combining AlphaFold2 and MMseqs2 | Open source, free Google Colab access [13] |

| ESMfold | Software | Protein language model for fast prediction without MSA | Open source [13] |

| OpenFold | Software | Open-source AlphaFold2 reimplementation with training code | Open source [12] [13] |

| Boltz-1 | Software | Fully open-source alternative to AlphaFold3 | Open source, commercial use allowed [12] |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | Experimental structures for training and validation | Free access [10] |

| UniProt/TrEMBL | Database | Protein sequences for MSA generation | Free access [10] |

| C.I. Mordant Red 7 | C.I. Mordant Red 7|CAS 3618-63-1|Mordant Dye | Bench Chemicals | |

| DBCO-NHCO-PEG4-acid | DBCO-NHCO-PEG4-acid, CAS:1870899-46-9, MF:C32H40N2O9, MW:596.68 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathways and Logical Relationships

The core innovation of modern protein structure prediction lies in the integration of evolutionary information with physical constraints through specialized neural network architectures.

Figure 2: Logical Framework Bridging Theory and Implementation

Applications in Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

The unprecedented accuracy of modern structure prediction tools has transformed their application across biomedical research:

- Drug Target Identification: Rapid structural characterization of potential drug targets, including membrane proteins notoriously difficult to study experimentally [8] [12].

- Mechanism of Action Studies: Understanding disease mutations by mapping them to structural contexts and predicting their disruptive effects [8] [13].

- Antibody Design: Prediction of antibody-antigen complex structures to guide therapeutic antibody engineering [12].

- Small Molecule Docking: Despite limitations in small molecule binding pocket prediction, AlphaFold3 shows improved capability for predicting protein-ligand interactions [12].

For drug discovery pipelines, the recommended workflow involves using open-source alternatives like Boltz-1 or RoseTTAFold for commercial applications, supplemented with experimental validation for critical targets [12].

Future Directions and Protocol Adaptation

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends requiring protocol adaptation:

- Complex Prediction: Move beyond single chains to multi-protein complexes, protein-nucleic acid interactions, and large assemblies [11] [12].

- Conformational Dynamics: Development of methods to predict alternative conformations and folding intermediates, not just static structures [13].

- Integration with Experimental Data: Hybrid approaches that combine computational predictions with sparse experimental data (Cryo-EM, NMR, cross-linking) [10].

- Generative Design: Inversion of the structure prediction problem to design novel protein sequences that fold into desired structures [13].

For research teams, establishing a flexible infrastructure that can incorporate new model architectures as they emerge while maintaining backward compatibility with existing workflows is essential for long-term research productivity.

The field of structural biology is defined by a fundamental and growing asymmetry: the explosive growth in protein sequence data vastly outpaces the slow accumulation of experimentally solved structures. This data gap presents both a significant challenge and a compelling opportunity for research in machine learning-based protein structure prediction.

The core of this disparity is quantified in the data from major biological repositories. The following table illustrates the current scale of this imbalance:

Table 1: The Protein Sequence-Structure Gap as of 2025

| Data Type | Repository | Count | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Sequences | UniProtKB/TrEMBL | Over 250 million | [14] |

| Protein Sequences | UniRef | Over 250 million | [14] |

| Experimentally Solved Structures | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | ~210,000 | [14] [15] |

| General Protein Sequences | TrEMBL Database (2022) | Over 200 million | [16] |

This discrepancy exists because high-throughput sequencing technologies can generate protein sequences quickly and inexpensively from genomic data. In contrast, experimental methods for determining protein structures—such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM)—are often time-consuming, expensive, and technically demanding [15] [17] [16]. The rate at which new protein sequences are discovered has created a massive gap that computational methods, particularly machine learning, are now poised to address.

Successful development of machine learning models for structure prediction relies on a curated set of data resources and software tools. The table below details the essential components of the research toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for ML-Based Protein Structure Prediction

| Category | Resource Name | Primary Function | Key Features/Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Repositories | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. | Source of atomic-level structural data for training and validation; provides annotations for secondary structure and functional sites. [14] [17] |

| UniProtKB | Comprehensive protein sequence and functional information database. | Divided into manually curated Swiss-Prot and automatically annotated TrEMBL; essential for sequence-based analysis. [14] | |

| Specialized Databases | DisProt | Manually curated database of Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs). | Provides experimentally validated disorder annotations for benchmarking predictors. [14] |

| MobiDB | Resource for intrinsic protein disorder annotations. | Combines experimental and computational annotations for large-scale analyses. [14] | |

| Benchmarking Initiatives | CASP (Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction) | Biennial community-wide blind assessment of protein structure prediction methods. | Gold-standard competition for evaluating the accuracy of new prediction tools, including EMA methods. [14] [17] [18] |

| CAID (Critical Assessment of Intrinsic Disorder) | Benchmarking initiative for IDR prediction tools. | Uses high-quality datasets from DisProt and PDB to standardize evaluation. [14] | |

| Software Tools & Frameworks | AlphaFold | Deep learning system for highly accurate protein structure prediction. | Uses MSAs and novel neural network architectures (Evoformer) to predict atomic coordinates. [18] [19] |

| ESMFold / OmegaFold | Single-sequence-based protein structure predictors. | Leverage protein language models (PLMs) for fast prediction without explicit MSAs. [20] | |

| SPIRED | Lightweight, single-sequence-based structure prediction model. | Designed for fast inference and integration into end-to-end fitness prediction frameworks. [20] |

Machine Learning Approaches to Bridge the Gap

Machine learning, particularly deep learning, has revolutionized protein structure prediction by learning the complex mapping from amino acid sequences to their three-dimensional structures. These approaches can be broadly categorized, each with distinct methodologies for leveraging available data.

Table 3: Categories of Machine Learning Approaches for Protein Structure Prediction

| Category | Description | Key Methodologies | Representative Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template-Based Modeling (TBM) | Utilizes known protein structures (templates) as a basis for predicting the structure of a homologous target sequence. | Homology Modeling, Threading (Fold Recognition) | MODELLER [15] [16], SWISS-MODEL [17], HHpred [15] |

| Template-Free Modeling (TFM) | Predicts structure directly from sequence and MSAs without relying on global template structures. Also includes modern AI-based methods. | Co-evolutionary Analysis (DCA), Deep Learning on MSAs | AlphaFold [18] [19], RoseTTAFold [20], trRosetta [15] |

| Single-Sequence Prediction | A sub-category of TFM that uses Protein Language Models (PLMs) to predict structure from a single sequence, bypassing the need for explicit MSA construction. | Protein Language Models (PLMs), Transformer Architectures | ESMFold [20], OmegaFold [20], SPIRED [20] |

| Ab Initio / Free Modeling | Predicts structure based purely on physicochemical principles and energy minimization, without relying on existing structural templates. | Molecular Dynamics, Physics-Based Energy Functions | Rosetta [15] [19], QUARK [15] |

End-to-End Prediction and Fitness Workflow

Modern research frameworks are evolving to integrate structure prediction directly with downstream functional analysis, such as predicting the effects of mutations on protein fitness and stability.

Experimental Protocols for Model Training and Validation

Protocol: Building a Supervised Learning Model for Structure Prediction

This protocol outlines the key steps for training a deep learning model to predict protein structures from sequences, using resources like the PDB.

Dataset Curation and Preprocessing

- Source Raw Data: Download protein sequences and structures from the PDB. The PDB provides atomic coordinates and curated annotations like secondary structure elements [14].

- Filter Data: Apply selection criteria such as a minimum resolution (e.g., < 2.5 Ã…) for X-ray structures to ensure high-quality training data [21].

- Remove Redundancy: Use a filter based on sequence identity (e.g., no pair of sequences in the training set shares >25% identity) to create a non-redundant dataset and minimize data leakage [21].

- Split Data: Partition the filtered dataset into training, validation, and test sets, ensuring no homologous proteins are shared between sets.

Feature Engineering and Input Representation

- Sequence Features: Encode the primary amino acid sequence using one-hot encoding or embeddings from a pre-trained Protein Language Model (PLM) [14] [20].

- Evolutionary Features: Generate Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) for the target protein using databases like UniRef and the BFD [14] [18]. Process MSAs into position-specific scoring matrices (PSSMs) or profile hidden Markov models [15].

- Template Information (Optional): For template-based models, identify homologous templates via sequence-sequence or sequence-structure alignment and extract relevant structural features [15] [16].

Model Architecture and Training

- Select Architecture: Choose a suitable deep learning architecture. Modern models often use:

- Evoformer (as in AlphaFold2): A novel architecture that jointly processes MSA and pairwise representations, using attention mechanisms to reason about spatial and evolutionary relationships [18].

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): To operate on the predicted structure for downstream tasks like fitness prediction [20].

- Define Output and Loss: The output is a 3D structure. The loss function typically combines terms for the frame-aligned point error (FAPE) and violations of physical constraints [18]. Newer models like SPIRED employ a relative displacement loss (RD Loss) to enhance efficiency [20].

- Train Model: Optimize model parameters on the training set, using the validation set for hyperparameter tuning and to monitor for overfitting.

- Select Architecture: Choose a suitable deep learning architecture. Modern models often use:

Model Validation and Benchmarking

- Internal Validation: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set using metrics like TM-score (for global fold accuracy) and lDDT (for local distance-based accuracy) [20].

- Independent Benchmarking: Assess model performance on independent, time-split datasets (e.g., proteins released after the training data cutoff) and in community-wide blind assessments like CASP or CAMEO to ensure generalizability and state-of-the-art performance [18] [20].

Protocol: End-to-End Prediction of Protein Fitness from Sequence

This protocol describes the workflow for using an integrated model like SPIRED-Fitness to predict mutational effects directly from a single sequence.

- Input Preparation: Provide the wild-type amino acid sequence. Optionally, specify single or double mutations for fitness prediction [20].

- Structure and Feature Extraction: The sequence is passed through the pre-trained SPIRED module, which acts as an information extractor and outputs the predicted 3D structure. The structural information is encoded as a graph or a set of inter-residue relationships [20].

- Fitness Prediction: The structural representation is fed into a downstream graph neural network that has been trained on deep mutational scanning (DMS) data. This network learns to map structural features to fitness scores [20].

- Output and Interpretation: The model outputs a fitness score for the input sequence (and/or its mutants). For stability prediction (SPIRED-Stab), the output is the predicted change in stability (ΔΔG or ΔTm) [20].

- Finetuning (Optional): The entire framework (structure prediction + fitness prediction) can be finetuned end-to-end on specific fitness or stability datasets to improve performance on a particular task [20].

The disparity between billions of protein sequences and only thousands of solved structures is a defining challenge in modern biology. However, as outlined in this application note, the rise of sophisticated machine learning frameworks has created a viable path to bridge this gap. By leveraging curated biological databases, standardized benchmarking practices, and end-to-end deep learning models, researchers can now accurately predict protein structures and their functional consequences at scale. This capability is set to profoundly accelerate research in fundamental biology and streamline the process of drug development.

The evolution of computational methods for protein structure prediction represents a cornerstone of modern structural bioinformatics and a critical foundation for building effective machine learning models. The transformation from early physical principles-based approaches to today's deep learning-powered systems has been marked by key methodological paradigms: homology modeling, threading, and ab initio prediction. These approaches provide the conceptual framework and historical data essential for developing new machine learning algorithms in structural biology. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this evolution is not merely academic; it directly informs the selection of appropriate tools, the interpretation of AI model outputs, and the strategic design of novel predictive pipelines. The following application notes and protocols detail the technical specifications, experimental workflows, and practical implementations of these foundational methods within the context of modern machine learning research for protein structure prediction.

Methodological Foundations and Quantitative Comparison

The table below summarizes the core principles, evolutionary context, and performance characteristics of the three primary computational methods for protein structure prediction.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Protein Structure Prediction Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Evolutionary Context | Accuracy & Limitations | Representative Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homology Modeling (Comparative Modeling) | Predicts structure based on sequence similarity to a protein with a known structure (template) [22] [16] [23]. | One of the earliest and most widely used computational techniques; relies on the availability of homologous templates in databases [23]. | Accuracy: RMSD of 1-2 Ã… if sequence identity >30% [22]. Limitations: Accuracy declines with decreasing sequence identity; cannot predict novel folds [22] [23]. | SWISS-MODEL [22], MODELLER [22], I-TASSER (threading+assembly) [22] |

| Threading (Fold Recognition) | Fits a target sequence into a library of known structural folds, regardless of sequence similarity [22] [16] [23]. | Developed to address the "protein folding problem" when no clear homologous template exists [22] [23]. | Use Case: Effective for proteins with low sequence identity but known structural folds [22]. Limitations: Performance depends on the comprehensiveness of the fold library and scoring functions [16]. | Phyre2 [22], HHpred [22], I-TASSER (threading+assembly) [22] |

| Ab Initio (De Novo) | Predicts structure from physical principles and energy minimization without using homologous templates [22] [24] [16]. | Represents a fundamentally different approach; computationally demanding but can predict novel folds [23]. | Accuracy: Traditionally limited for large proteins; modern variants like C-QUARK show significant improvement (e.g., 75% success rate on test set vs. 29% for earlier QUARK) [25]. Limitations: Extremely computationally intensive [22] [25]. | Rosetta [22], QUARK [22], C-QUARK [25] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Homology Modeling with MODELLER

This protocol outlines the standard five-step workflow for building a protein structural model using a known homologous structure as a template [22] [16].

Workflow Diagram: Homology Modeling

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Template Identification

- Objective: Identify a suitable protein structure template from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with significant sequence similarity to the target.

- Procedure: Perform a sequence search using BLAST or PSI-BLAST against the PDB. A template with a sequence identity of >30% is generally considered suitable for reliable modeling [22] [16].

- Output: A PDB file of the template and a sequence alignment file.

Target-Template Alignment

- Objective: Create an accurate sequence alignment between the target and template sequences.

- Procedure: Use alignment software (e.g., ClustalOmega, MUSCLE) to align the target sequence with the template sequence. Manually inspect and adjust the alignment, especially in regions of insertions (loops) or deletions.

- Output: A refined multiple sequence alignment (MSA) file.

Model Building

- Objective: Construct a 3D model of the target protein.

- Procedure: Using a modeling package like MODELLER, copy the backbone coordinates from the template to the target based on the alignment. Model sidechains and any regions not present in the template (e.g., loops) using internal algorithms and fragment libraries [22].

- Output: A preliminary 3D atomic model in PDB format.

Model Refinement

- Objective: Optimize the model's stereochemistry and minimize atomic clashes.

- Procedure: Subject the initial model to energy minimization using molecular dynamics force fields. This step relaxes the model, correcting unrealistic bond lengths, angles, and van der Waals contacts.

- Output: An energy-minimized 3D model.

Model Validation

- Objective: Assess the quality and reliability of the final model.

- Procedure: Use tools like PROCHECK to analyze Ramachandran plot outliers, and MolProbity to check for steric clashes and other geometric inconsistencies [23].

- Output: Validation reports and a quality score for the final model.

Protocol 2: Contact-Assisted Ab Initio Folding with C-QUARK

This protocol details a modern ab initio approach that integrates predicted contact-maps to guide fragment assembly simulations, significantly enhancing accuracy [25].

Workflow Diagram: C-QUARK Ab Initio Folding

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Input and MSA Generation

- Objective: Gather evolutionary information from homologous sequences.

- Procedure: Search whole-genome and metagenome sequence databases (e.g., UniRef) using the target sequence to build a deep Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) [25].

- Output: A comprehensive MSA file.

Contact-Map Prediction

- Objective: Predict long-range residue-residue contacts to guide folding.

- Procedure: Process the MSA through deep-learning and coevolution-based predictors (e.g., DCA) to generate multiple contact-maps. These maps indicate the probability of two residues being spatially close [25].

- Output: A set of predicted contact-maps with associated confidence scores.

Fragment Library Assembly

- Objective: Provide a library of local structural elements as building blocks.

- Procedure: Extract short (1-20 residues) protein fragments from the PDB that are sequence-similar to local regions of the target. These fragments are used to assemble the full-length model [25].

- Output: A library of structural fragments.

Replica-Exchange Monte Carlo (REMC) Simulation

- Objective: Assemble the full-length structure through conformational sampling.

- Procedure: Guide the REMC simulation using a composite force field. This field integrates knowledge-based energy terms, fragment-derived contacts, and the sequence-based contact-map predictions via a novel "3-gradient (3G) contact potential". This potential effectively balances the noisy contact information with the physical force field [25].

- Output: A large ensemble of decoy structures.

Model Selection and Validation

- Objective: Identify the most representative and accurate model from the decoy ensemble.

- Procedure: Cluster all generated decoys using SPICKER. Select the model from the largest and most densely populated cluster as the final prediction [25].

- Output: A final, clustered 3D model. Accuracy is typically assessed using TM-score (where >0.5 indicates a correct fold) or Global Distance Test (GDT_TS) [25].

Table 2: Key Resources for Computational Protein Structure Prediction

| Category | Item / Software | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids; essential for template sourcing and model training [22] [16]. | All methods, particularly Homology Modeling and Threading. |

| UniProt / TrEMBL | Comprehensive protein sequence database; critical for generating Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) [16]. | Ab Initio (C-QUARK) and modern deep learning models. | |

| Software & Tools | BLAST / PSI-BLAST | Algorithm for identifying homologous sequences and structures in databases [22] [23]. | Homology Modeling (Template Identification). |

| MODELLER | Software for building protein 3D models from sequence alignment and template structure [22]. | Homology Modeling. | |

| Rosetta | Suite for biomolecular structure prediction and design; uses fragment assembly and energy minimization [22] [13]. | Ab Initio Prediction. | |

| QUARK / C-QUARK | Ab initio protein structure prediction by replica-exchange Monte Carlo simulation; C-QUARK integrates contact restraints [25]. | Ab Initio Prediction. | |

| Validation Services | PROCHECK / MolProbity | Tools for stereochemical quality assessment of protein structures (e.g., Ramachandran plots) [23]. | Model validation across all methods. |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for running computationally intensive simulations like REMC in ab initio methods [22] [25]. | Ab Initio Prediction, large-scale analysis. |

Integration with Machine Learning Research

The evolution from classical methods to modern machine learning models like AlphaFold2 is a continuum of increasing abstraction and integration. AlphaFold2's architecture implicitly incorporates principles from all three historical methods. Its Evoformer module processes MSAs to extract co-evolutionary signals, a concept central to both threading and contact-assisted ab initio folding [13]. The structure module then performs a geometric construction of the atomic coordinates, analogous to a highly optimized and informed model-building step [13].

For researchers building new machine learning models, this history provides critical insights. The success of C-QUARK demonstrates that even low-accuracy contact predictions, when intelligently integrated with physical simulation (3G potential), can dramatically improve outcomes [25]. This suggests hybrid approaches that combine deep learning predictions with physics-based refinement remain a powerful strategy. Furthermore, the limitations of these classical methods—such as homology modeling's reliance on templates and ab initio's computational cost—define the very problems that machine learning models must solve to generalize effectively. Understanding the specific failure modes and success metrics (e.g., TM-score, GDT_TS) of these established protocols is crucial for benchmarking and validating new AI-driven approaches.

For over 50 years, the "protein folding problem"—predicting a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence—stood as a grand challenge in biology [26]. Understanding protein structure is fundamental to elucidating biological function and accelerating drug discovery. Traditional experimental methods like X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy are time-consuming and expensive, creating a massive gap between known protein sequences and solved structures [27] [28]. While computational approaches existed, they fell far short of atomic accuracy, especially when no homologous structure was available [26]. This document provides application notes and experimental protocols for building machine learning models that transformed this field, enabling rapid, accurate protein structure prediction.

Quantitative Breakthrough: Performance Metrics Before and After Deep Learning

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) serves as the gold-standard blind assessment for evaluating prediction accuracy [26]. The performance leap enabled by deep learning is quantitatively demonstrated below.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics at CASP14 for AlphaFold2 and Next Best Method

| Metric | AlphaFold2 | Next Best Method | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Backbone Accuracy (Cα RMSD95) | 0.96 Å | 2.8 Å | ~2.9x |

| All-Atom Accuracy (RMSD95) | 1.5 Ã… | 3.5 Ã… | ~2.3x |

| Comparative Accuracy | Competitive with experimental structures in most cases | Far short of experimental accuracy | Revolutionary |

Abbreviations: RMSD95, Root-mean-square deviation at 95% residue coverage; Cα, Alpha carbon [26].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Major Protein Structure Prediction Methods

| Method | Category | Key Principle | Representative Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homology Modeling | Template-Based Modeling (TBM) | Uses a closely related homologous protein as a structural template [27]. | SWISS-MODEL [28] |

| Threading/Fold Recognition | Template-Based Modeling (TBM) | Fits sequence into a known structural fold, even with low sequence similarity [27] [28]. | GenTHREADER [28] |

| Ab Initio | Free Modeling (FM) | Relies on physicochemical principles and energy minimization without templates [27] [28]. | QUARK [28] |

| Deep Learning (AlphaFold2) | Free Modeling (FM) | Uses neural networks to learn evolutionary, physical, and geometric constraints from data [26]. | AlphaFold2 [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Deep Learning-Based Structure Prediction

Protocol 1: Implementing an AlphaFold2-Style Architecture

This protocol outlines the core architectural components and training procedure for a state-of-the-art prediction model, based on the AlphaFold2 system [26].

I. Input Representation and Feature Engineering

- A. Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Construction: Input the target amino acid sequence. Use a tool like HHblits to search large genomic databases (e.g., UniRef, BFD) to generate a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA). The MSA represents the evolutionary history of the protein and is formatted as an ( N{seq} \times N{res} ) array, where ( N{seq} ) is the number of homologous sequences and ( N{res} ) is the number of residues [26].

- B. Pair Representation Generation: Compute an ( N{res} \times N{res} ) array representing potential residue-pair interactions. This matrix is initialized from the MSA and may incorporate other features like co-evolutionary signals and template information if available [26].

II. Neural Network Architecture: The Evoformer and Structure Module

- A. Evoformer Processing (Trunk): The Evoformer is a novel neural network block designed to process the inputs [26].

- Pass the MSA and pair representations through a stack of Evoformer blocks.

- Within each block, use attention mechanisms and triangle multiplicative updates to allow continuous information exchange between the MSA and pair representations, enforcing spatial and evolutionary constraints [26].

- The output is a "processed" MSA and a refined pair representation that contains a concrete structural hypothesis.

- B. Structure Module: This module translates the abstract representations into explicit 3D atomic coordinates [26].

- Initialize a set of residue-level rigid body frames (rotations and translations) in a trivial state.

- Process these frames through an equivariant attention architecture, which respects the geometric symmetries of 3D space.

- The network implicitly reasons about all atoms, outputting precise 3D coordinates for all heavy atoms.

- Use a loss function that heavily weights the orientational correctness of the residues.

III. Training and Iterative Refinement

- A. Recycling: To improve accuracy, the outputs of the entire network (both coordinates and representations) are recursively fed back into the input of the same network modules for several cycles (typically 3-4). This iterative refinement is crucial for high accuracy [26].

- B. Loss Functions: Employ a composite loss function during training:

- Frame-Aligned Point Error (FAPE): Measures the local structural accuracy.

- Distogram Loss: Penalizes errors in predicted inter-residue distances.

- Masked MSA Loss: Helps the model learn meaningful representations by predicting masked portions of the input MSA [26].

Protocol 2: End-to-End Workflow for Prediction and Validation

This protocol describes the complete process from sequence input to model validation, applicable for research and drug discovery pipelines.

I. Data Curation and Pre-processing

- A. Input Sequence Preparation: Obtain the canonical amino acid sequence of the target protein from a reliable database like UniProt. Ensure the sequence is correct and of adequate length.

- B. Database Searching: Configure and run the MSA generation tool (e.g., HHblits, Jackhmmer) against standard databases. This step is computationally intensive and may require high-performance computing (HPC) clusters. Monitor for depth and quality of the MSA.

II. Model Inference and Execution

- A. System Configuration: Run the prediction model (e.g., AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold) on a system with adequate resources, typically high-end GPUs (e.g., NVIDIA A100, V100) and sufficient RAM (>64 GB recommended).

- B. Execution: Execute the model with the pre-processed MSA and pair features as input. The runtime can vary from minutes for short proteins to hours for very long complexes.

III. Post-processing and Model Validation

- A. Confidence Scoring: The model outputs a per-residue confidence score, the predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT). This score reliably estimates the local accuracy of the prediction [26]. Visualize the model colored by pLDDT to identify low-confidence regions.

- B. Model Quality Assessment: Calculate global metrics like Template Modeling Score (TM-score) to assess the global fold correctness. A TM-score >0.5 suggests a correct fold, while >0.8 indicates a high-quality model.

- C. Structural Analysis: Use molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL, ChimeraX) to manually inspect the predicted structure for plausible stereochemistry, bond lengths, and side-chain packing.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Structure Prediction

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | A worldwide repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, used for training deep learning models and as templates in TBM [27] [28]. |

| UniProtKB | Database | A comprehensive resource for protein sequence and functional information, used as the primary source for input sequences and for building MSAs [28]. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Tools | Software | Programs like HHblits and Jackhmmer. They find homologous sequences in genomic databases, providing the evolutionary data that is the primary input for models like AlphaFold2 [26]. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | A public database providing pre-computed AlphaFold2 predictions for over 200 million proteins, enabling rapid access to models without local computation [29]. |

| RoseTTAFold | Software | An end-to-end deep learning protein structure prediction method, based on a three-track neural network architecture that simultaneously considers sequence, distance, and coordinate information [29]. |

| pLDDT | Metric | The predicted Local Distance Difference Test. A per-residue confidence score provided by AlphaFold2 that estimates the reliability of the local structural prediction [26]. |

Architectures, Data Pipelines, and Hands-On Implementation

The development of robust machine learning (ML) models for protein structure prediction hinges on access to large-scale, high-quality structural and sequence data. Four data resources form the cornerstone of this research: the Protein Data Bank (PDB), a repository of experimentally determined structures; UniProt, a comprehensive knowledgebase of protein sequences and functional information; the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, providing expansive access to AI-predicted structures; and the ESM Metagenomic Atlas, which offers structure predictions for metagenomic proteins. For ML practitioners, these resources provide the essential training data, ground truth labels, and benchmarking standards required to develop and validate novel algorithms. The integration of experimental and computationally predicted structures, as showcased in Table 1, enables a multi-faceted approach to model training, addressing the limitations of structural coverage in the experimental data alone.

Table 1: Core Data Sources for Protein Structure Prediction ML Research

| Resource | Primary Content | Key Utility for ML | Scale (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB [30] | Experimentally determined 3D structures (X-ray, NMR, Cryo-EM) | Source of high-accuracy ground truth data for model training and validation | ~200,000 structures [9] |

| UniProt [31] | Manually curated (Swiss-Prot) and automatically annotated (TrEMBL) protein sequences | Provides sequences, functional annotations, and evolutionary context for model input | Millions of sequences [31] |

| AlphaFold DB [32] | AI-predicted structures for sequences in UniProt | Expands structural coverage for training; provides confident predictions for proteins with unknown structures | Over 200 million entries [32] |

| ESM Metagenomic Atlas [33] [34] | Structures predicted by ESMFold for metagenomic sequences | Enables exploration of uncharted protein space; trains/fine-tunes models on diverse, novel folds | Over 700 million predicted structures [34] |

Resource-Specific Application Notes and Protocols

Protein Data Bank (PDB)

The PDB is the global archive for experimentally determined three-dimensional structures of biological macromolecules, serving as the primary source of structural truth. For ML research, it is critical to parse these files into a structured data format that can be consumed by computational models. The Biopython PDB module provides a robust toolkit for this task, implementing a Structure/Model/Chain/Residue/Atom (SMCRA) architecture to hierarchically organize structural data [35]. This overcomes the limitations of the legacy PDB file format, which has been superseded by the more extensible PDBx/mmCIF format as the standard archive format.

Protocol 2.1.1: Parsing a PDB Structure for Feature Extraction

Initialize the PDB Parser: Create a

PDBParserobject. SettingPERMISSIVE=1allows the parser to tolerate common minor errors in PDB files without failing.Load the Structure File: Use the parser to read the PDB file and create a Structure object. The

structure_idis a user-defined identifier.Extract Atomic Coordinates: Traverse the SMCRA hierarchy to access atomic-level data, such as 3D coordinates.

Extract Experimental Metadata (Optional): Access information from the PDB file header, though caution is advised as this data can be incomplete. The mmCIF format is more reliable for header information.

For programmatic analysis of the broader PDB, the RCSB PDB API provides structured access to search and retrieve metadata and annotations at scale, which is essential for building large, curated training datasets [30].

UniProt

UniProt is the central hub for protein sequence and functional annotation. For ML, it provides the primary input sequences for structure prediction and the functional labels necessary for developing models that predict biological activity. The UniProt Knowledgebase is divided into Swiss-Prot (manually curated) and TrEMBL (automatically annotated), offering a balance of quality and scale [31]. A key ML application is using the Gene Ontology (GO) terms from UniProt to train models for protein function prediction from sequence or structure.

Protocol 2.2.1: Mapping Protein Sequences to Structures via UniProt

This protocol is critical for creating a high-quality dataset where each sequence is paired with its experimentally determined structure.

Acquire Sequence and Annotation Data: Download the UniProt dataset in a structured format (e.g., XML, TAB) for the organism of interest via the UniProt website or FTP server.

Identify Sequences with Structural Data: Filter the dataset using the cross-reference to the PDB. This information is contained in the

database(PDB)field in UniProt flat files or thedbreferenceattribute in XML.Resolve Mapping at the Residue Level: For precise modeling, utilize the residue-level mapping between UniProt sequences and PDB structures that is maintained in collaboration with the Macromolecular Structure Database (MSD) group at the EBI [31]. This ensures accurate alignment of sequence positions to structural coordinates, which is vital for tasks like predicting the functional impact of mutations.

Construct Final Dataset: For each entry in the filtered list, pair the UniProt sequence with the 3D coordinates from the corresponding PDB file, which can be parsed using the methods in Protocol 2.1.1.

AlphaFold DB

AlphaFold DB provides open access to the groundbreaking predictions of AlphaFold 2, a deep learning system that regularly predicts protein structures with accuracy competitive with experiment [32] [9]. For ML research, this database is transformative. It provides predicted structures for the entire human proteome and over 200 million other proteins, massively expanding the structural coverage of known sequences [32]. This allows researchers to train models on a much broader set of protein folds and families than would be possible with experimental data alone. Furthermore, the per-residue confidence metric, the predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT), allows for the filtering of high-confidence predictions to create reliable training subsets or to identify potentially disordered regions [9].

Protocol 2.3.1: Benchmarking a Custom Model Against AlphaFold DB

This protocol outlines how to use AlphaFold DB predictions as a baseline to evaluate the performance of a novel structure prediction model.

Define a Test Set: Select a set of protein sequences for which high-quality AlphaFold DB predictions are available. A robust test set should include proteins with diverse folds and lengths.

Download AlphaFold DB Structures: For each protein in the test set, retrieve the predicted structure and the associated pLDDT scores from the AlphaFold DB website (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk).

Generate Custom Predictions: Run your custom ML model on the same set of protein sequences.

Calculate Structural Accuracy Metrics: For each protein, compute standard metrics to compare your model's output to the AlphaFold DB prediction.

- RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation): Measures the average distance between atoms after structural alignment. Lower values indicate better accuracy. Useful for comparing structures of the same protein.

- TM-score (Template Modeling Score): A length-independent metric for assessing the topological similarity of protein structures. A score >0.5 suggests generally the same fold, while >0.8 indicates a highly similar fold [36].

Analyze by Confidence and Length: Stratify the results based on the AlphaFold pLDDT confidence and loop length, as accuracy is known to correlate with these factors. For example, benchmark results should be reported separately for high-confidence (pLDDT > 90) regions versus low-confidence (pLDDT < 70) regions and for short loops (<10 residues) versus long loops (>20 residues), as the latter show lower prediction accuracy (average RMSD of 2.04 Ã…) [36].

ESM Metagenomic Atlas

The ESM Metagenomic Atlas is a repository of over 700 million protein structure predictions generated by ESMFold, a language model-based structure prediction tool [33] [34]. Unlike AlphaFold 2, which relies on co-evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs), ESMFold predicts structure end-to-end directly from a single sequence using a protein language model (ESM-2) that has learned evolutionary patterns from a vast corpus of sequences. This makes it exceptionally fast and well-suited for metagenomic proteins, which often lack homologous sequences for MSA construction [34]. For ML research, this atlas is a treasure trove of novel protein folds from under-explored biological niches, providing unique data for training models to generalize beyond the well-characterized regions of protein space.

Protocol 2.4.1: Using the ESM Atlas API for High-Throughput Data Retrieval

This protocol enables the programmatic downloading of ESMFold structures for large-scale ML training pipelines.

Install Required Libraries: Ensure you have the

requestslibrary installed in your Python environment.Construct API Call: Use the ESM Atlas API to submit a protein sequence and receive the predicted structure in PDB format.

Handle Response and Save Structure: Check for a successful response and save the returned PDB data to a file.

For bulk analysis, the ESMFold model can also be run locally or via ColabFold to generate predictions for custom sequence lists not already in the atlas [33].

Table 2: Key Software Tools and Data Resources

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Biopython PDB Module [35] | Software Library | Parsing PDB, mmCIF, and MMTF files into Python data structures for analysis and feature extraction. |

| MMCIF2Dict [35] | Software Tool | Creating a Python dictionary from an mmCIF file for low-level access to all data fields. |

| Mol* [30] | Visualization Software | Interactive 3D visualization and analysis of molecular structures within the RCSB PDB website or as a standalone tool. |

| ColabFold [34] | Software Suite | Provides accelerated, publicly accessible implementations of AlphaFold2 and ESMFold via Google Colab. |

| OpenFold [13] | Software Framework | A trainable, open-source reimplementation of AlphaFold2, enabling model introspection and custom training. |

| Foldseek [34] | Software Suite | Fast, efficient structural similarity search against massive databases like the AFDB or ESM Atlas. |

Integrated Workflow for ML Model Development

The true power of these resources is realized when they are integrated into a cohesive workflow for training and validating ML models for structure prediction. The diagram below illustrates a typical pipeline that leverages the unique strengths of each data source.

Diagram 1: Integrated ML workflow for protein structure prediction, showing how core data sources feed into model development and validation.

This workflow begins with Data Curation, where sequences from UniProt are paired with structural data from the PDB (for ground truth), AlphaFold DB (for expanded training set coverage and baseline comparison), and the ESM Metagenomic Atlas (to incorporate novel folds). During Feature Extraction, inputs for the model are prepared, which can include the raw amino acid sequence, computed multiple sequence alignments, and/or embeddings from protein language models like ESM-2. The ML Model Training phase uses these features to learn the mapping from sequence to structure. Frameworks like OpenFold are crucial here, as they are not just for inference but are designed to be retrained, allowing researchers to test new architectures or training strategies [13]. Finally, rigorous Model Validation is performed against held-out experimental structures from the PDB and benchmarked against state-of-the-art predictions from AlphaFold DB and ESMFold to quantify performance improvements.

In the pursuit of building effective machine learning models for protein structure prediction, the representation of amino acid sequences stands as a foundational and critical first step. The chosen representation directly influences a model's ability to capture the complex biochemical principles and evolutionary patterns that govern how a linear sequence of amino acids folds into a three-dimensional structure. The field has evolved significantly from simple, hand-crafted encodings to sophisticated, learnable representations derived from massive sequence databases. Within the context of a protein structure prediction research pipeline, selecting an appropriate sequence encoding method involves balancing computational efficiency, dependency on external data, and the capacity to capture long-range interactions and structural constraints. This protocol outlines the primary sequence representation approaches, their implementation details, and their integration into a complete structure prediction workflow, providing researchers with practical guidance for selecting and applying these methods effectively.

Foundational Sequence Encoding Methods

One-Hot Encoding

One-hot encoding represents each of the 20 standard amino acids in a protein sequence as a binary vector of length 20, where a single element is 1 (indicating the presence of that specific amino acid) and all other elements are 0 [37] [38]. This method treats each amino acid as an independent category without inherent relationships.

Protocol: Implementation of One-Hot Encoding

- Sequence Alignment and Padding: For a dataset of protein sequences, first determine the maximum sequence length (L). Shorter sequences must be padded to this length using a designated null character.

- Dictionary Creation: Create a dictionary mapping each of the 20 amino acid characters (e.g., 'A' for Alanine, 'R' for Arginine) to an integer index from 0 to 19. Include an additional index (e.g., 20) for the padding character.

- Vectorization: For each sequence, convert it into an integer array of length L using the mapping dictionary.

- Binarization: Apply a one-hot encoding function to this integer array. This results in a 2D matrix of size L x 21 (20 amino acids + 1 padding character). The final representation for a batch of sequences is a 3D tensor of shape (Batch Size, L, 21).

Physicochemical and Chemical Feature Encodings

These encodings move beyond categorical identity to represent amino acids by their biochemical properties, such as hydrophobicity, volume, charge, and polarity [38] [39]. More advanced chemical encodings use molecular fingerprints to describe the structure of amino acid side chains.

Protocol: Generating Molecular Fingerprint-Based Encodings

- Fingerprint Generation: For each amino acid, generate a molecular graph with atoms as nodes and chemical bonds as edges. Compute a molecular fingerprint, such as a Morgan fingerprint (circular fingerprint) or an atom-pair fingerprint, which encodes molecular substructures into a fixed-length bit vector [38].

- Dimensionality Reduction: The initial fingerprint vectors are often very high-dimensional (e.g., 4096 bits for Morgan fingerprints). Use the FastMap dimensionality reduction algorithm to project these vectors into a lower-dimensional space (e.g., 14-18 dimensions) while preserving the chemical distances between different amino acids [38].

- Sequence Representation: A protein sequence is represented as a matrix of size L x D, where D is the dimension of the reduced chemical encoding for each amino acid at each position.

Table 1: Comparison of Foundational Sequence Encoding Methods

| Encoding Method | Dimensionality per Residue | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-Hot Encoding | 20 (or 21 with padding) | Categorical, local information | Simple, interpretable, no external data needed | Does not capture biochemical similarities, high-dimensional sparse matrix |

| Physicochemical Properties | ~7-15 continuous values | Hand-crafted features based on experiments | Encodes known biochemical priors | Limited to pre-defined features, may miss complex patterns |

| Chemical Fingerprints | ~14-18 continuous values | Based on molecular graph structure of side chains | Captures complex chemical relationships | Requires cheminformatics tools, reduction step needed |

Advanced Embeddings from Protein Language Models (PLMs)

Protein Language Models (PLMs), inspired by breakthroughs in natural language processing (NLP), learn contextual representations of amino acids by training on millions of diverse protein sequences [40] [41]. They learn the "language" of evolution, capturing complex statistical patterns that reflect structural and functional constraints.

Model Architectures and Training Objectives

- Masked Language Models (e.g., ESM, BERT-style): These models are trained by randomly masking (hiding) portions of the input sequence and then learning to predict the masked tokens based on the full context provided by the unmasked parts of the sequence [37] [41]. This bidirectional context allows the model to learn rich, contextual representations for every position in a sequence. Models like ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) are exemplary implementations of this approach [37].

- Autoregressive Language Models (e.g., UniRep, GPT-style): These models are trained to predict the next amino acid in a sequence given all previous amino acids [37] [41]. While they can capture long-range dependencies, the representation at each position is based only on the preceding context. UniRep is a prominent example that uses a recurrent architecture (mLSTM) for this purpose [37].

Protocol: Generating Embeddings with Pre-trained PLMs

- Model Selection: Choose a pre-trained PLM suitable for your task. Common choices include the ESM family of models (e.g., ESM-2) or UniRep. Ensure the model is compatible with your computational framework (e.g., PyTorch, Hugging Face Transformers).

- Sequence Preparation: Format your input sequences as standard amino acid strings. There is no need for multiple sequence alignment (MSA).

- Embedding Extraction: Pass the sequences through the pre-trained model.

- For per-residue embeddings, extract the hidden state representations from the final (or an intermediate) layer of the model for each amino acid position. The output is a matrix of size L x E, where E is the embedding dimension (e.g., 1280 for ESM-2).

- For a global sequence representation, common strategies include computing the mean of all per-residue embeddings or using the embedding of a special token (e.g., [CLS] in BERT-style models). However, research indicates that learning the aggregation via a bottleneck autoencoder can be superior to simple averaging [42].

Ensemble and Hybrid Representation Approaches

Combining multiple representation methods can synergize their strengths and lead to improved predictive performance [37] [38]. An ensemble approach can compensate for the weaknesses of a single method.

Protocol: Creating an Ensemble Representation

- Multiple Encoding Generation: For a given set of sequences, generate multiple independent representations (e.g., One-Hot, ESM embeddings, and fingerprint-based encodings).

- Feature Concatenation: For each sequence, concatenate the different representation vectors (either at the per-residue or global sequence level) into a single, high-dimensional feature vector.

- Model Training: Train a downstream predictor (e.g., a neural network) on this concatenated feature set. The model will learn to weight the importance of the different representations automatically. Studies have shown such ensembles can increase predictive performance for tasks like fitness prediction [37].

Table 2: Overview of Advanced Protein Language Model Embeddings

| PLM (Example) | Training Objective | Architecture | Context | Typical Embedding Dimension (E) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESM (e.g., ESM-2) | Masked Language Modeling | Transformer | Bidirectional (Full) | 512 to 1280+ |