De Novo Genome Assembly from Illumina Reads: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundation to Application

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on de novo genome assembly using Illumina short-read sequencing. It covers foundational principles, from defining de novo assembly and its advantages to critical pre-assembly planning, including assessing genome properties and DNA quality requirements. The guide details a complete methodological workflow, including quality control, assembly algorithms like de Bruijn graphs, and post-assembly polishing. It further addresses common challenges and optimization strategies for complex genomes and offers robust frameworks for assembly validation, quality assessment, and comparative genomics to ensure the generation of accurate, reliable reference sequences for downstream biomedical research.

De Novo Genome Assembly from Illumina Reads: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundation to Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on de novo genome assembly using Illumina short-read sequencing. It covers foundational principles, from defining de novo assembly and its advantages to critical pre-assembly planning, including assessing genome properties and DNA quality requirements. The guide details a complete methodological workflow, including quality control, assembly algorithms like de Bruijn graphs, and post-assembly polishing. It further addresses common challenges and optimization strategies for complex genomes and offers robust frameworks for assembly validation, quality assessment, and comparative genomics to ensure the generation of accurate, reliable reference sequences for downstream biomedical research.

Understanding De Novo Assembly: Core Concepts and Prerequisites for Illumina Sequencing

What is De Novo Sequencing? Defining Assembly Without a Reference Genome

De novo sequencing is the process of reconstructing an organism's primary genetic sequence from scratch without the use of a pre-existing reference genome for alignment [1] [2]. This method is foundational for genomic research on novel or uncharacterized organisms, enabling scientists to generate a complete genetic blueprint where none previously existed [3].

This article details the core principles, applications, and protocols for de novo genome assembly, with a specific focus on methodologies utilizing Illumina sequencing reads. It is structured to serve as a practical guide for researchers and scientists embarking on novel genome projects.

Core Concepts and Applications

Fundamental Principles

The de novo assembly process involves computationally assembling short DNA sequence reads into longer, contiguous sequences (contigs) [1]. The quality of this assembly is often evaluated based on the size and continuity of these contigs, with fewer gaps indicating a higher-quality assembly [1]. This approach contrasts with reference-based sequencing, where reads are aligned to a known template, and is uniquely powerful for discovering entirely new genetic elements and structural variations [2].

Key Advantages and Applications

De novo sequencing unlocks research possibilities that are challenging or impossible with reference-based methods. The primary advantages and applications are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Applications and Rationale for De Novo Sequencing

| Application Area | Specific Use-Case | Research Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Novel Organism Genomics | Sequencing of non-model, rare, or newly discovered species [2]. | Enables foundational genetic research on organisms lacking any prior genomic information [2]. |

| Structural Variant Discovery | Identification of large inversions, deletions, translocations, and complex rearrangements [1] [4]. | Crucial for understanding genetic diseases and complex traits, as these variants are often difficult to detect with short-read alignment [4]. |

| Repetitive Region Resolution | Clarification of highly similar or repetitive genomic regions [1]. | Essential for accurate genome assembly and finishing, as these regions are problematic for reference-based assembly [1] [4]. |

| Mutation & Disease Research | Study of de novo mutations (DNMs) and investigation of rare genetic disorders or cancer [2]. | Provides an unbiased approach to identify novel, disease-associated genetic variants without parental reference [2]. |

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

A robust de novo sequencing strategy often involves a combination of sequencing technologies and specialized bioinformatics pipelines. The following workflow outlines a standard approach for a hybrid de novo assembly.

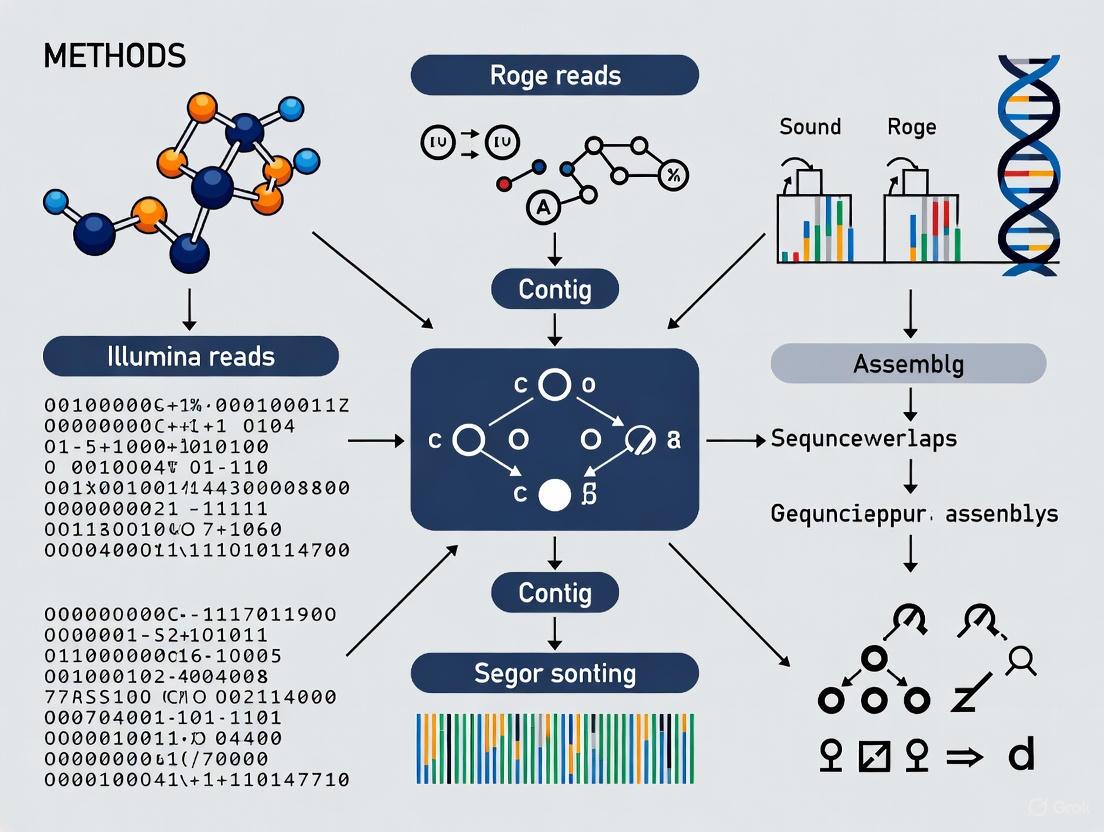

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for hybrid de novo genome assembly.

Detailed Protocol: Hybrid De Novo Assembly

This protocol is adapted from a public Galaxy tutorial and describes the steps for assembling a bacterial genome using a combination of long and short reads [5].

Data Acquisition and Baseline Quality Control

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Extract high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA. Minimize shearing for long-read sequencing [5].

- Sequencing:

- Establish Quality Baseline: Use a tool like Busco (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) on a closely related reference genome, if available, to establish a baseline for the expected completeness of a high-quality assembly [5]. A result showing >99% complete BUSCOs is excellent.

Draft Assembly and Polishing

Long-Read Draft Assembly: Use a long-read assembler like Flye to generate an initial draft assembly from the Nanopore reads [5].

- Tool:

Flye - Input:

nanopore_reads.fastq - Output:

draft_assembly.fasta

- Tool:

Short-Read Polishing: Use the high-accuracy Illumina short reads to "polish" the long-read draft assembly, correcting base-level errors.

- Tool:

Pilon - Input:

draft_assembly.fasta,illumina_reads_1.fastq,illumina_reads_2.fastq - Output:

polished_assembly.fasta[5]

- Tool:

Assembly Quality Assessment

- Run QUAST: Use QUAST (Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies) to generate standard assembly metrics (e.g., number of contigs, largest contig, N50, total length) [5].

- Run Busco: Re-run Busco on your final polished assembly and compare the completeness to the baseline established in Step 1.3 [5].

Illumina-Centric Workflow for Small Genomes

For smaller genomes (e.g., microbes), a high-coverage Illumina-only approach can produce a quality draft assembly. The following diagram details this specific protocol.

Diagram 2: An Illumina-focused de novo assembly workflow for microbial genomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful de novo sequencing projects rely on integrated workflows encompassing specialized laboratory equipment, reagents, and software. The following table details key solutions for an Illumina-based approach.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for De Novo Sequencing

| Category | Product / Tool Example | Specific Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kit | Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep [1] | Prepares genomic DNA for sequencing without PCR amplification bias, enabling uniform coverage and accurate variant calling for sensitive applications like de novo microbial assembly. |

| Sequencing System | MiSeq System [1] | Provides integrated sequencing and data analysis with speed and simplicity, ideal for targeted and small genome sequencing projects. |

| Bioinformatics Apps | DRAGEN Bio-IT Platform [1] | Performs ultra-rapid secondary analysis of NGS data, including accurate mapping, de novo assembly, and variant calling. |

| BaseSpace SPAdes/Velvet Assembler [1] | De novo assembler applications suitable for single-cell and isolate genomes, accessible via the Illumina genomics computing environment. | |

| Analysis Software | Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) [1] | A high-performance visualization tool for interactive exploration of large, integrated genomic datasets, useful for validating assemblies and viewing structural variants. |

| (S)-Laudanine | (S)-Laudanine | (S)-Laudanine is a key benzylisoquinoline alkaloid intermediate for biosynthesis research. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| 2-PMPA (sodium) | 2-PMPA (sodium), CAS:373645-42-2, MF:C6H7Na4O7P, MW:314.04 | Chemical Reagent |

Data Presentation and Analysis

The quality of a de novo assembly is quantified using a standard set of metrics. The table below defines these key metrics and their interpretation.

Table 3: Key Metrics for De Novo Assembly Quality Assessment

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation & Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Contigs | The total number of contiguous sequences in the assembly. | Fewer contigs indicate a more complete assembly. The ideal is one contig per chromosome/plasmid. |

| N50 Contig Length | The length of the shortest contig such that 50% of the entire assembly is contained in contigs of at least this length. | A larger N50 indicates a more continuous assembly. This is a key measure of assembly quality. |

| Total Assembly Length | The total number of base pairs in the assembly. | Should be consistent with the expected genome size of the organism. |

| BUSCO Score | The percentage of universal single-copy orthologs found complete in the assembly [5]. | Measures gene space completeness. A score >95% is typically excellent and indicates a high-quality assembly. |

| Identity (vs. Reference) | The percentage of aligned bases that are identical when compared to a related reference genome. | Not always applicable, but if a reference exists, a high identity (>99.9%) indicates high base-level accuracy. |

De novo genome assembly is a critical process for reconstructing the complete genomic sequence of an organism without the use of a reference genome. Within methods for de novo genome assembly from Illumina reads research, two strengths stand out: the generation of highly accurate reference sequences and the detailed characterization of structural variants (SVs). These capabilities are fundamental for advancing genomic studies of novel species, uncovering the genetic basis of diseases, and enabling precision medicine initiatives. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, particularly from Illumina, allow for faster and more accurate characterization of any species compared to traditional methods, making de novo sequencing accessible for a wide range of organisms [1]. This application note details the experimental protocols and key advantages of this approach, providing a framework for researchers to leverage these techniques in their investigations.

The primary advantages of de novo assembly using Illumina reads include the creation of high-quality reference genomes and the ability to detect a broad spectrum of structural variants, which are large genomic alterations typically defined as encompassing at least 50 base pairs [6]. These SVs include deletions, duplications, insertions, inversions, and translocations, and they contribute significantly to genomic diversity and disease phenotypes [6] [7]. Accurate characterization of these variants is crucial, as they impact more base pairs in the human genome than all single-nucleotide differences combined [7].

The table below summarizes the key advantages and their applications:

Table 1: Key Advantages of De Novo Assembly with Illumina Reads

| Advantage | Description | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Generation of Accurate Reference Sequences | Constructs novel genomic sequences without a pre-existing reference, even for complex or polyploid genomes [1]. | Enables genomic studies of non-model organisms, finishing genomes of known organisms, and provides the foundation for population genetics and evolutionary biology studies. |

| Clarification of Repetitive Regions | Resolves highly similar or repetitive sequences, such as low-complexity patterns and homopolymers, which are challenging for assembly algorithms [1] [8]. | Reduces assembly fragmentation and misassemblies, leading to more contiguous and complete genome assemblies. |

| Identification of Structural Variants (SVs) | Detects a broad range of SVs, including deletions, inversions, translocations, and complex rearrangements [1] [6]. | Facilitates the study of genetic diversity, association of SVs with diseases like cancer and neurological disorders, and understanding of adaptive evolution in plants and animals [6] [9]. |

| Insight into Haplotype Variation | When combined with long-read data, can help resolve haplotype-specific sequences and heterozygous SVs in complex immune gene families [10]. | Provides a clearer picture of individual genetic makeup and its functional consequences, moving beyond a single, haploid reference sequence. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Integrated Workflow for Immune Loci Assembly

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully assembled eight complex immune system loci (e.g., HLA, immunoglobulins, T cell receptors) from a single human individual [10]. The workflow integrates multiple sequencing technologies to overcome challenges posed by high paralogy and repetition in these regions.

Sample Preparation (Cell Sorting):

- Purpose: To obtain DNA that represents the germline configuration of immune genes, avoiding the somatic recombination present in active immune cells.

- Procedure: Isolate CD14+ monocytes or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from fresh whole blood using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from these cells using a kit designed for long-read sequencing.

Multi-Platform Sequencing:

- Purpose: Generate complementary data types that combine the accuracy of short reads with the long-range connectivity of long reads and optical maps.

- Procedure:

- Long-Read Sequencing: Sequence the extracted DNA on a PacBio or Oxford Nanopore platform to generate long reads (≥10 kb) that span repetitive regions.

- Short-Read Sequencing: Sequence the same DNA library on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq) to generate high-accuracy short reads for polishing and error correction.

- Optical Mapping: Generate a Bionano optical map to provide an independent, long-range scaffold for validating assembly structure.

Data Integration and De Novo Assembly:

- Purpose: Reconstruct the target loci accurately by leveraging the strengths of each data type.

- Procedure:

- Perform initial de novo assembly using a long-read assembler (e.g., Canu, Flye).

- Polish the initial assembly using the high-accuracy Illumina short reads with a tool like Pilon or Racon. For regions with systematic errors, a targeted corrector like BrownieCorrector can be applied, which focuses on reads overlapping short, highly repetitive patterns [8].

- Use the optical mapping data to scaffold and validate the large-scale structure of the assembly, correcting for large misassemblies.

Variant Identification and Validation:

- Purpose: Call heterozygous and homozygous SVs by comparing the assembly to the human reference genome (GRCh38).

- Procedure: Use a combination of alignment-based tools (e.g., Minimap2) and k-mer based approaches to identify structural differences. Manually inspect complex variants by visualizing read alignments and optical map alignments to confirm their structure [10].

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of this integrated protocol:

Protocol for Assembly Evaluation and Error Correction

Accurate assembly evaluation is essential for obtaining optimal results and for developers to improve assembly algorithms [11]. This protocol describes a reference-free method for evaluating and locally correcting a de novo assembly using long reads.

Read-to-Contig Alignment:

- Align the long sequencing reads back to the assembled contigs using a sensitive aligner like Minimap2 [11].

Error Identification:

- Small-Scale Errors (< 50 bp): From the alignment pileup, identify base substitutions, small collapses, and small expansions. Filter potential errors using a binomial test based on the number of error-supporting reads to distinguish true assembly errors from sequencing errors or genuine variants [11].

- Structural Errors (≥ 50 bp): Identify larger anomalies, including:

- Expansion/Collapse: Incorrect repetition or omission of sequence, common in repeats.

- Haplotype Switch: The assembler creates a chimeric sequence between two haplotypes at a heterozygous SV site.

- Inversion: A section of the genome is inverted in the assembly.

Targeted Error Correction:

- For each identified error region, extract the raw reads covering that region.

- Compute a consensus sequence from these reads.

- Replace the erroneous sequence in the assembly with the new consensus sequence [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful execution of the protocols above relies on a suite of specialized reagents, software, and sequencing platforms. The following table catalogs key solutions for this field.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for De Novo Assembly and SV Calling

| Item Name | Category | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep | Library Prep | Prepares genomic DNA for sequencing without PCR bias, ensuring uniform coverage and high-accuracy data for de novo assembly [1]. |

| MiSeq System | Sequencer | Provides a streamlined platform for rapid and simple targeted or small genome sequencing [1]. |

| PacBio HiFi Reads | Sequencing Data | Generates long reads (∼15 kb) with very high accuracy (<0.5%), ideal for resolving complex regions and producing high-quality assemblies [7] [12]. |

| DRAGEN Bio-IT Platform | Bioinformatics | Performs ultra-rapid secondary analysis of NGS data, including mapping, de novo assembly, and variant calling [1]. |

| SPAdes Genome Assembler | Software | A universal de novo assembler for single-cell, isolate, and hybrid data that effectively handles errors through multi-sized de Bruijn graphs [8] [13]. |

| BrownieCorrector | Software | An error correction tool focusing on reads that overlap highly repetitive DNA regions, preventing misassemblies in complex contexts [8]. |

| Inspector | Software | A reference-free evaluator for long-read assemblies that identifies structural and small-scale errors and can perform targeted correction [11]. |

| VolcanoSV | Software | A hybrid SV detection pipeline using a reference genome and local de novo assembly for precise, haplotype-resolved SV discovery across multiple sequencing platforms [7]. |

| acetylpheneturide | acetylpheneturide, CAS:163436-98-4, MF:C6H7BrN2O2S | Chemical Reagent |

| Acid Red 315 | Acid Red 315, CAS:12220-47-2, MF:C9H11BrO3 | Chemical Reagent |

The methodologies for de novo genome assembly from Illumina reads, especially when integrated with complementary technologies, provide powerful capabilities for generating accurate reference sequences and characterizing structural variants. The protocols outlined herein—from integrated multi-platform sequencing for complex loci to rigorous assembly evaluation—provide a roadmap for researchers to exploit these advantages. As the field progresses, emerging technologies like geometric deep learning, as seen in the GNNome framework, show promise for further automating and improving the assembly of complex genomic regions [12]. By leveraging these tools and workflows, scientists and drug development professionals can continue to expand our understanding of genomic diversity, unravel the genetic underpinnings of disease, and accelerate the development of targeted therapies.

The journey of de novo genome assembly from Illumina reads begins long before sequencing data is processed, rooted in the critical pre-assembly phase of accurately characterizing fundamental genomic properties. For researchers embarking on genome assembly projects, comprehensive assessment of genome size, ploidy, and heterozygosity constitutes an indispensable prerequisite that directly determines assembly success and accuracy. These intrinsic genomic characteristics profoundly influence experimental design, technology selection, and computational resource allocation, forming the foundational framework upon which entire assembly strategies are built. Within the context of a broader thesis on de novo assembly methods, this protocol establishes the essential preliminary steps that enable researchers to avoid costly missteps and optimize their assembly workflows for Illumina sequencing technologies.

Genome assembly represents a complex computational challenge of reconstructing complete genomic sequences from millions of short DNA fragments, analogous to solving an enormous jigsaw puzzle without a reference picture [14]. The characterization of genomic parameters provides the crucial "box image" that guides this reconstruction process. Specifically, understanding genome size informs sequencing coverage requirements, ploidy determination dictates the expected allelic relationships within the data, and heterozygosity assessment predicts regions where assembly algorithms may struggle to collapse haplotypes. Each of these factors interacts to define the complexity of the assembly task, with inaccurate estimations potentially leading to fragmented assemblies, misassemblies, or incomplete genomic representation [15]. For Illumina-based approaches, which generate shorter reads compared to third-generation technologies, these pre-assembly assessments become even more critical as the technical limitations amplify the challenges posed by complex genomic architectures.

Theoretical Background: Genomic Parameters and Their Assembly Implications

Interrelationship of Key Genomic Characteristics

The three core genomic parameters—genome size, ploidy, and heterozygosity—exist in a dynamic interplay that collectively defines assembly complexity. Genome size determines the absolute scope of the assembly project and directly influences sequencing cost and computational requirements [15]. Ploidy level establishes the fundamental architecture of the genome, with diploid or polyploid organisms containing multiple chromosome sets that introduce allelic variation [16]. Heterozygosity represents the manifestation of this allelic variation as sequence differences between homologous chromosomes, creating challenges for assemblers that typically aim to produce a single consensus sequence [15].

These parameters interact in ways that significantly impact assembly outcomes. For instance, a highly heterozygous diploid genome will present greater assembly challenges than a homozygous diploid of identical size, as assemblers must reconcile divergent sequences from homologous regions [17]. Similarly, polyploid genomes introduce additional complexity through the presence of multiple allelic variants at each locus. The combination of large genome size, high ploidy, and significant heterozygosity represents the most challenging scenario for de novo assembly, often requiring specialized diploid-aware assemblers and substantially greater sequencing coverage [17].

Impact on Assembly Quality and Strategy

Inaccurate characterization of genomic parameters prior to assembly frequently leads to suboptimal outcomes that compromise downstream biological analyses. High heterozygosity can cause assemblers to interpret allelic variants as separate loci, resulting in duplicated regions and artificially inflated assembly sizes [15] [17]. Without proper ploidy awareness, assemblers may collapse heterozygous regions into single consensus sequences, losing valuable haplotype information essential for understanding trait variation [16]. Furthermore, underestimating genome size leads to insufficient sequencing coverage, leaving gaps in repetitive or complex regions where additional data is most needed [15].

The choice between different assembly strategies heavily depends on these preliminary characterizations. For highly heterozygous genomes, specialized diploid-aware assemblers such as Platanus-allee or MaSuRCA may be necessary to preserve haplotype information [17]. Hybrid approaches combining Illumina short reads with long-read technologies may be warranted for large, complex genomes with high repeat content [14] [17]. Accurate parameter estimation enables researchers to select the most appropriate assembly toolkit and adjust parameters to accommodate the specific characteristics of their target genome.

Experimental Protocols for Genome Characterization

Genome Size Estimation via Flow Cytometry and K-mer Analysis

Flow Cytometry Protocol Flow cytometry provides a well-established experimental method for genome size estimation that is independent of sequencing. The following protocol outlines the key steps for reliable analysis:

Sample Preparation: Select fresh leaf tissue from the target organism during the leaf expansion stage, as mature tissues may yield reduced nuclei counts [18]. Include internal reference standards with known genome sizes (e.g., rice (Oryza sativa subsp. japonica 'Nipponbare', 2C = 0.91 pg) or tomato (Solanum lycopersicum LA2683, 2C = 0.92 pg)) processed simultaneously with experimental samples.

Nuclei Isolation: Rapidly chop 1 cm² of leaf tissue with a sharp blade in 1 mL of WPB lysis solution (commercially available from Leagene Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), which has demonstrated superior performance for plant species like Choerospondias axillaris [18]. Immediately filter the homogenate through a 30-μm nylon mesh to remove debris.

Staining and Analysis: Add DNA fluorochrome (e.g., propidium iodide) to the nuclear suspension and analyze immediately (within 5 minutes of dissociation) using a flow cytometer [18]. Analyze a minimum of 5,000 nuclei per sample, ensuring the coefficient of variation (CV) of the fluorescence peaks is below 5% for reliable results.

Genome Size Calculation: Calculate the sample genome size using the formula: Genome Size (bp) = (Sample Peak Mean / Standard Peak Mean) × Standard Genome Size (bp) Perform technical replicates (minimum n=3) to ensure reproducibility, with results typically varying by less than 3% between replicates [18].

K-mer Analysis Protocol K-mer analysis leverages sequencing data itself to computationally estimate genome size, providing an orthogonal validation method:

Sequencing Requirements: Generate Illumina short-read data with sufficient coverage (typically 20-40x) using paired-end libraries [18] [19]. Ensure high sequence quality through appropriate quality control steps.

K-mer Counting: Use Jellyfish (v2.2.6 or higher) with the following command for k-mer counting [19]:

Generate a k-mer frequency histogram:

jellyfish histo -o 21mer_out.histo 21mer_outGenome Size Calculation: Identify the primary peak in the k-mer frequency histogram (representing heterozygous regions) and apply the formula [19]: Genome Size = (Total Number of K-mers / Peak Position) For example, in a study of Choerospondias axillaris, this method yielded a genome size estimate of 365.25 Mb [18].

Table 1: Comparison of Genome Size Estimation Methods

| Method | Principle | Sample Requirements | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Cytometry | DNA content quantification via fluorescence | Fresh tissue, internal standards | Rapid, inexpensive, established protocol | Requires specific equipment, fresh tissue | ±3-5% [18] |

| K-mer Analysis | Frequency distribution of subsequences | High-quality Illumina reads | Computational, uses actual sequencing data | Requires sufficient coverage, affected by heterozygosity | ±0.0017% for 1Mb genome [19] |

Ploidy Determination Through Flow Cytometry and Computational Methods

Flow Cytometry Ploidy Detection The optimized flow cytometry protocol for ploidy determination builds upon the genome size estimation method:

Sample Processing: Follow the nuclei isolation protocol described in Section 3.1, ensuring consistent processing conditions across all samples.

Data Analysis: Identify ploidy levels by comparing the fluorescence intensity ratios between samples and internal standards. For example, in an analysis of 58 Choerospondias axillaris accessions, diploids showed a ploidy coefficient of 0.91-1.15, while triploids exhibited coefficients of 1.27-1.66 [18].

Validation: Confirm putative polyploids using multiple internal standards. In the aforementioned study, 11 putative triploids identified using rice as a standard were validated using tomato as an alternative standard, yielding consistent results [18].

Computational Ploidy Estimation For researchers with sequencing data but without access to flow cytometry, computational tools provide an alternative approach:

Data Preparation: Generate whole-genome sequencing data with sufficient coverage (typically 20x or higher for diploid genomes).

Tool Selection: Choose appropriate software based on available resources. PloidyFrost offers reference-free estimation using de Bruijn graphs, while nquire implements a Gaussian mixture model for likelihood-based estimation [20].

Analysis Execution: For PloidyFrost, follow the workflow comprising: (a) adapter trimming with Trimmomatic, (b) k-mer database construction with kmc3, (c) compacted de Bruijn graph construction with bifrost, (d) superbubble detection and variant analysis, (e) filtering based on genomic features, and (f) visualization and Gaussian mixture modeling for ploidy inference [20].

Table 2: Ploidy Determination Methods and Their Applications

| Method | Underlying Technology | Ploidy Levels Detectable | Requirements | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Cytometry | Fluorescence intensity measurement | Diploid, triploid, tetraploid [18] | Fresh tissue, flow cytometer | Histogram with peak ratios |

| PloidyFrost | De Bruijn graphs, k-mer analysis | Multiple levels without reference [20] | WGS data, computational resources | Allele frequency distribution, GMM results |

| nquire | Gaussian mixture model | Diploid, triploid, tetraploid [20] | Reference genome, WGS data | Likelihood comparisons |

Heterozygosity Assessment Using K-mer Analysis

Heterozygosity assessment through k-mer analysis provides critical insights for anticipating assembly challenges:

Sequencing and Quality Control: Generate Illumina paired-end sequencing data with at least 30x coverage. Perform quality control using FastQC and trim adapters and low-quality bases using Trimmomatic or similar tools [20].

K-mer Spectrum Analysis: Generate a k-mer frequency histogram using Jellyfish as described in Section 3.1. Analyze the resulting distribution for characteristic patterns.

Heterozygosity Estimation: In a heterozygous genome, the k-mer frequency histogram typically shows a bimodal distribution with:

- A primary peak representing homozygous k-mers

- A secondary peak at approximately half the coverage of the primary peak, representing heterozygous k-mers [18] The ratio between these peaks and the overall shape of the distribution provides an estimate of heterozygosity levels.

Parameter Calculation: For example, in a study of Choerospondias axillaris, k-mer analysis revealed 0.91% genome heterozygosity, 34.17% GC content, and 47.74% repeated sequences, indicating a genome with high heterozygosity and duplication levels [18].

Integrated Workflow and Data Interpretation

Comprehensive Pre-Assembly Assessment Strategy

A robust pre-assembly planning strategy integrates multiple assessment methods to build a comprehensive understanding of genomic characteristics. The following workflow provides a systematic approach to genome characterization:

Diagram 1: Integrated pre-assembly planning workflow with 760px max width

Interpretation of Results and Assembly Strategy Formulation

Integrating Multiple Data Sources Effective pre-assembly planning requires synthesizing information from all characterization methods to form a coherent understanding of genomic complexity. When flow cytometry and k-mer analysis yield discordant genome size estimates, investigate potential causes such as high heterozygosity inflating k-mer-based estimates or the presence of large repetitive regions [18] [19]. Similarly, discrepancies between flow cytometry ploidy calls and computational estimates may indicate recent polyploidization events or complex genomic architectures that challenge computational methods [20].

Assembly Strategy Optimization Based on the characterized genomic parameters, select appropriate assembly strategies:

- Low heterozygosity (<0.1%): Standard assemblers such as SPAdes or MaSuRCA typically perform well with Illumina-only data [17].

- Moderate heterozygosity (0.1-1.0%): Consider diploid-aware assemblers like Platanus-allee or Redbean to prevent haplotype collapse [17].

- High heterozygosity (>1.0%): Implement specialized workflows with purge_dups or Purge Haplotigs to remove redundant contigs from separated haplotypes [17]. Consider supplementing Illumina data with long-read technologies to resolve complex regions.

Table 3: Assembly Strategy Based on Genomic Characteristics

| Genome Characteristic | Low Complexity | Moderate Complexity | High Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Size | <100 Mb | 100-500 Mb | >500 Mb |

| Ploidy | Haploid | Diploid | Polyploid (≥3x) |

| Heterozygosity | <0.1% | 0.1-1.0% | >1.0% |

| Recommended Strategy | Standard assemblers (SPAdes) | Diploid-aware assemblers (Platanus-allee) | Hybrid approach + haplotig purging [17] |

| Expected N50 | High | Moderate | Lower/Fragmented |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Pre-Assembly Genome Characterization

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Application | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclei Isolation | WPB Lysis Solution [18] | Flow cytometry | Superior performance for plant tissues | Commercial availability (Leagene Biotechnology) |

| Internal Standards | Oryza sativa 'Nipponbare' [18] | Genome size reference | 2C = 0.91 pg | Well-characterized genome |

| Solanum lycopersicum LA2683 [18] | Genome size reference | 2C = 0.92 pg | Alternative validation standard | |

| DNA Staining | Propidium Iodide | DNA quantification | Fluorescent intercalating dye | Standard for flow cytometry |

| DNA Extraction | High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA protocols [15] | Long-read sequencing | Structural integrity preservation | Critical for hybrid approaches |

| Quality Control | FastQC [20] | Sequencing data QC | Quality metrics visualization | Standard first-pass analysis |

| Adapter Trimming | Trimmomatic [20] | Read preprocessing | Adapter removal, quality filtering | Flexible parameter adjustment |

| K-mer Analysis | Jellyfish [19] | K-mer counting | Efficient frequency analysis | Multiple k-size options |

| KMC3 [20] | K-mer counting | Database construction for graphs | PloidyFrost dependency | |

| Ploidy Estimation | PloidyFrost [20] | Reference-free ploidy | De Bruijn graph approach | No reference genome needed |

| nquire [20] | Likelihood-based ploidy | Gaussian mixture model | Requires reference genome | |

| Heterozygosity Analysis | GenomeScope [18] | Genome profiling | K-mer spectrum modeling | Web-based tool available |

| Ictasol | Ictasol, CAS:12542-33-5, MF:C6H10ClNO | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| BASIC RED 18:1 | BASIC RED 18:1, CAS:12271-12-4, MF:C21H29ClN5O3.Cl, MW:470.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Comprehensive pre-assembly planning through accurate determination of genome size, ploidy, and heterozygosity establishes the critical foundation for successful de novo genome assembly from Illumina reads. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide researchers with a systematic framework for genomic characterization, enabling informed decisions about sequencing depth, assembly algorithms, and potential computational challenges. By investing in thorough preliminary assessment, researchers can significantly enhance assembly continuity, completeness, and accuracy, ultimately maximizing the scientific return on sequencing investments. As genome assembly methodologies continue to evolve, these fundamental characterizations remain essential prerequisites that bridge raw sequencing data and biologically meaningful genomic representations.

The Impact of Repetitive Sequences and GC-Content on Assembly Success

Genome assembly is a foundational step in genomics, yet its success is critically dependent on the inherent characteristics of the genome itself. This application note examines two major sources of assembly bias: repetitive sequences and GC-content. We detail the molecular nature of these challenges, provide protocols for their experimental assessment and computational mitigation, and present key reagent solutions to support researchers in generating high-quality de novo assemblies from Illumina reads.

The goal of de novo genome assembly is to reconstruct the complete genomic sequence of an organism from shorter, fragmented sequencing reads without the aid of a reference genome. While short-read technologies, such as Illumina sequencing by synthesis (SBS), provide highly accurate data, their limited read length makes the assembly process susceptible to specific genomic architectures [4].

- Repetitive Sequences: A substantial fraction of most genomes consists of repetitive DNA, which can be categorized into tandem repeats (TRs) and interspersed repeats (transposable elements) [21]. When a repetitive region is longer than the sequencing read length, it becomes impossible to uniquely determine where a read originated. This leads to assembly breaks, misassemblies, and collapsed regions, where multiple distinct repeats are merged into a single, incorrect sequence [22] [23].

- GC-Content Bias: The base composition of the genome directly influences sequencing library preparation, particularly during the PCR amplification step. Genomic regions with extremely high or low GC-content are often underrepresented in the final sequencing library. This results in non-uniform read coverage, creating gaps in the assembly and compromising its completeness and continuity [24] [25].

Understanding, quantifying, and mitigating these biases is therefore essential for any de novo genome assembly project.

Technical Background

The Nature and Impact of Repetitive Sequences

Repetitive DNA is ubiquitous across the tree of life and poses a multi-level problem for sequencing and assembly, potentially leading to errors that propagate into public databases [22].

Table 1: Major Categories of Repetitive Sequences Affecting Assembly

| Category | Subtype | Unit Size | Genomic Location | Assembly Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tandem Repeats (TRs) | Microsatellites | 1-9 bp | Genome-wide | Slippage causes fragmented assemblies |

| Minisatellites | 10-100 bp | Genome-wide | Misassembly due to high similarity between units | |

| Satellite DNA | 100 bp -> 1 kb | Centromeres, Telomeres | Nearly impossible to assemble with short reads | |

| Interspersed Repeats | LINEs (e.g., L1) | 1-6 kb | Genome-wide | Cause assembly breaks and collapses |

| SINEs (e.g., Alu) | 100-500 bp | Genome-wide | Prolific number of copies complicates assembly | |

| DNA Transposons | Variable | Genome-wide | Fossil elements can still cause misassembly |

These repetitive elements are not merely "junk DNA"; they can be functional and are often enriched in genes. For example, in humans, about 50% of the genome is repetitive, and roughly 4% of genes harbor transposable elements in their protein-coding regions [21]. Errors in assembling these regions can therefore directly lead to mis-annotation of genes and proteins [22].

GC-Content Bias in Sequencing

The GC-content bias describes the dependence between fragment count (read coverage) and the GC content of the DNA fragment. This bias is unimodal: both GC-rich fragments and AT-rich fragments are underrepresented in Illumina sequencing results [24]. The primary cause is believed to be PCR amplification during library preparation, where fragments with extreme GC content amplify less efficiently. This bias is not consistent between samples and must be addressed individually for each library [24]. The bias can be pronounced, with large (>2-fold) differences in coverage common even in 100 kb bins, and is influenced by the GC content of the entire DNA fragment, not just the sequenced read [24].

Experimental Assessment Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Repetitive Content withk-mer Analysis

This bioinformatics protocol estimates genome size, heterozygosity, and repetitive content using only Illumina short reads prior to assembly.

I. Principles A k-mer is a subsequence of length k from a sequencing read. In a diploid genome without repeats, the frequency of k-mers follows a Poisson distribution. Repeats create an overabundance of certain k-mers, observable in a k-mer frequency histogram.

II. Materials

- Computing Resources: Linux server with sufficient memory (>=32 GB RAM for small genomes).

- Software: Jellyfish (for k-mer counting), GenomeScope 2.0 (for histogram analysis).

- Input Data: Illumina whole-genome shotgun reads (FASTQ format).

III. Procedure

- Quality Control: Trim adapters and low-quality bases from raw FASTQ files using Trimmomatic or fastp.

- k-mer Counting: Run Jellyfish to count all k-mers in the cleaned reads. A k-mer size of 21-31 is typically used.

- Histogram Generation: Create a histogram of k-mer frequencies.

- Genome Characterization: Feed the histogram into GenomeScope 2.0 (web tool or command line) to model the genome profile and estimate key parameters.

IV. Data Interpretation The GenomeScope report provides estimates for:

- Genome Size: Calculated from the total number of k-mers and the unique k-mer count.

- Heterozygosity: Visible as a separate peak in the histogram.

- Repetitive Content: The proportion of the genome that is repetitive.

Protocol 2: Assessing GC-Bias

This protocol evaluates the presence and severity of GC-content bias in a sequencing library.

I. Principles By calculating the GC percentage of the reference genome (or assembled contigs) in sliding windows and plotting it against the read coverage, one can visualize the unimodal dependency that characterizes GC-bias.

II. Materials

- Software: BEDTools, SAMtools, and R/Python for statistical plotting.

- Input Data: A reference genome (or draft assembly) in FASTA format and the aligned Illumina reads (BAM format).

III. Procedure

- Calculate GC per Window: Use a custom script or tool to split the genome into windows (e.g., 1 kb) and calculate the GC% for each.

- Calculate Coverage per Window: Use

samtools bedcovormosdepthto calculate the mean read depth for each window. - Generate GC-Coverage Plot: In R, create a scatter plot or smoothed line plot of read coverage (y-axis) versus GC percentage (x-axis). The expected signature of GC-bias is a unimodal curve peaking at mid-range GC values.

IV. Data Interpretation A uniform distribution of coverage across all GC percentages indicates minimal bias. A strong unimodal curve, with depressed coverage at high and low GC values, confirms significant GC-bias that will require correction.

Workflow Diagram

Diagram 1: Experimental assessment workflow for repeats and GC-bias.

Mitigation Strategies and Reagent Solutions

Strategies for Repetitive Sequences

- Hybrid Assembly: Combining long-read technologies (PacBio or Oxford Nanopore) with Illumina short reads is the most effective strategy. Long reads span repetitive regions, providing the context for assembly, while accurate short reads polish the consensus sequence [5] [4].

- Specialized Assemblers: Use assemblers specifically designed to handle repeats, such as the Tandem Repeat Assembly Program (trap), which uses a strategy of not assembling a read if its position is ambiguous, effectively preventing misassemblies at the cost of more, shorter contigs [23].

- Increased Sequencing Depth: Higher coverage provides more reads that originate from the unique flanks of repetitive elements, aiding in their correct placement.

Strategies for GC-Content Bias

- PCR-Free Library Prep: Using PCR-free library preparation kits, such as the Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep, eliminates the primary source of GC-bias by avoiding the amplification step [24] [1].

- Bioinformatic Correction: Tools exist to normalize coverage based on the observed GC-coverage relationship. These methods predict expected coverage from GC% and use this to correct the raw data [24].

- Optimized Enzymes in RADseq: For reduced representation studies, the choice of restriction enzyme influences locus distribution. Enzymes with recognition sites of balanced GC content (e.g., ~50%) can provide more uniform coverage [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Assembly Challenges

| Research Reagent | Function/Benefit | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep | Eliminates PCR amplification, mitigating GC-bias for uniform coverage. | Whole-genome sequencing for assembly. |

| 2b-RAD Enzymes (e.g., AlfI, BaeI) | Restriction enzymes with balanced GC content in recognition sites for more uniform locus sampling. | Reduced-representation sequencing (RADseq). |

| PacBio HiFi Reads | Long reads (>10 kb) with high accuracy to span and resolve repetitive sequences. | Hybrid assembly to scaffold Illumina contigs. |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) Reads | Ultra-long reads (>100 kb) capable of spanning even the largest repeats. | Resolving complex regions, centromeres, telomeres. |

| Hi-C Library Kits | Captures chromatin proximity data for scaffolding contigs into chromosome-scale assemblies. | Determining contig order and orientation. |

| Base-selective Adaptors | Allows secondary reduction of loci number by selecting fragments with specific terminal nucleotides. | Cost-effective scaling for large-genome studies [25]. |

| Reactive blue 26 | Reactive blue 26, CAS:12225-43-3, MF:C10H16O | Chemical Reagent |

| fsoE protein | fsoE protein, CAS:145716-75-2, MF:C7H7Cl2N | Chemical Reagent |

Repetitive sequences and GC-content are intrinsic genomic properties that systematically undermine the success of de novo assembly. A robust assembly project must begin with a pre-assembly assessment of these features using k-mer analysis and GC-coverage plots. Mitigation requires a combination of wet-lab strategies—notably, PCR-free library prep and the integration of long-read technologies—and dry-lab approaches employing specialized assemblers and bioinformatic corrections. By systematically addressing these biases, researchers can significantly improve the quality, completeness, and accuracy of genomes assembled from Illumina reads.

The success of de novo genome assembly, a process of reconstructing a novel genome without a reference sequence, is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the input DNA [1]. For researchers using Illumina reads, this process involves assembling sequence reads into contigs, and the quality of this assembly is directly influenced by the size and continuity of these contigs, as well as the number of gaps in the data [1]. The integrity of the starting genetic material is therefore not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant of the entire project's outcome.

High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA, characterized by long, intact strands typically greater than 40 kilobases (kb) and often exceeding 100 kb, is the gold standard for advanced genomic analyses [26]. Unlike standard genomic DNA (gDNA), which encompasses all genetic material, HMW DNA is defined by its large size and high integrity [26]. In the context of de novo assembly, long DNA strands are essential because they act as scaffolds, allowing for accurate reconstruction of complex genomic regions, including repetitive sequences and structural variants, which are often ambiguous or inaccessible with shorter fragments [1] [4]. The rise of long-read sequencing technologies, which often complement Illumina data in hybrid assembly approaches, has made the consistent isolation of HMW DNA a fundamental requirement for cutting-edge genomic science [26].

The Critical Role of HMW DNA in Genomic Applications

Impact on Sequencing and Assembly Outcomes

The length of the DNA input directly dictates the "long-read" potential of a sequencing run. Nanopore sequencing devices, for example, generate reads that reflect the lengths of the loaded fragments [27]. To maximize sequencing output and assembly contiguity, it is crucial to begin with HMW DNA. The reliance on HMW DNA is particularly pronounced in applications that go beyond routine variant calling.

Table 1: Comparative Advantages of Short-Read and Long-Read Sequencing for Assembly

| Feature | Short-Read Sequencing (e.g., Illumina) | Long-Read Sequencing (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 50-600 base pairs [4] | Thousands to hundreds of thousands of base pairs [26] |

| Primary Strength | High accuracy, cost-effectiveness, high throughput [26] | Longer reads, resolution of complex regions [26] |

| De novo Assembly | Less effective for new genome assemblies [26] | Essential for assembling genomes from scratch [26] |

| Structural Variation Detection | Limited to small structural variations [26] | Critical for detecting large-scale genomic alterations [26] |

| Repetitive Regions | Struggles with highly repetitive and homologous regions [4] | Spans large repetitive motifs for accurate mapping [4] |

As illustrated in Table 1, long-read sequencing is indispensable for de novo assembly. HMW DNA is the foundational material that enables this technology to span repetitive regions and large structural variants, thereby clarifying these areas for accurate assembly [1]. This capability is vital for generating the accurate reference sequences needed to map novel organisms or finish genomes of known organisms [1].

Consequences of Using Sub-Optimal DNA

Using degraded or sheared DNA has direct and detrimental effects on downstream results:

- Fragmented Assemblies: Sheared DNA results in short sequencing reads, which are difficult to assemble correctly in complex or repetitive regions, leading to a higher number of gaps and disjointed contigs [1].

- Loss of Biological Insight: Many clinically and biologically important genes reside in GC-rich or repetitive regions. If the sequencing platform or input DNA cannot handle these areas, valuable insights can be missed. For example, one analysis showed that platforms with poor performance in challenging regions excluded pathogenic variants in genes like B3GALT6 (linked to Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) and FMR1 (linked to Fragile X syndrome) [28].

- Inefficient Sequencing: DNA samples with a significant proportion of short fragments can lead to suboptimal sequencing outputs. For nanopore sequencing, an insufficient amount of long "threadable ends" means pores remain idle, compromising overall throughput [27].

Comprehensive Quality Assessment of HMW DNA

Accurate quantification and quality assessment are non-negotiable for ensuring that HMW DNA meets the stringent requirements of de novo assembly. Several methods are employed in tandem to evaluate different parameters.

Table 2: Methods for DNA Quantification and Quality Control

| Method | What It Measures | Strengths | Limitations & Target Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometry | Concentration & purity via absorbance at 230, 260, 280 nm. | Simple and quick measurement [29]. | Non-specific; cannot differentiate between DNA, RNA, and free nucleotides [29].Target Purity Ratios: A260/280 ~1.8; A260/230 ~2.0-2.2 [27]. |

| Fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) | Concentration using fluorescent dyes (e.g., PicoGreen for dsDNA). | Highly specific to nucleic acids, reducing interference from contaminants; more sensitive than UV-Vis [29]. | Requires specific calibration; results depend on calibration standards [29]. |

| Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis | Size distribution of large DNA fragments (>10-20 kb). | Visually assesses DNA integrity and verifies high molecular weight [27]. | Not quantitative; time-consuming and labor-intensive [29]. |

| Capillary Electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer/Femto Pulse) | Size distribution and quantification. | Highly accurate; provides both sizing and quantification; suitable for high-throughput analysis [29]. | Expensive and requires specialized instrumentation [29]. |

Interpreting Quality Metrics

- Mass and Concentration: Fluorometers like the Qubit are recommended for accurate mass quantification as they are not fooled by common contaminants like RNA or free nucleotides [27]. High-concentration HMW DNA can be viscous and require gentle dilution with TE buffer and mixing by inversion to achieve homogeneity without shearing [27].

- Purity: The A260/280 ratio assesses protein contamination (~1.8 is ideal for DNA), while the A260/230 ratio detects contaminants like salts or organic compounds (ideal range 2.0-2.2) [27]. A ratio outside these ranges indicates the need for additional purification.

- Size/Integrity: For HMW DNA, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis or the Agilent Femto Pulse System are necessary, as conventional agarose gels cannot resolve fragments greater than 15–20 kb [27]. A successful HMW DNA extraction will show a dominant band of high molecular weight with minimal smearing downward.

Detailed Protocols for HMW DNA Extraction

Successful HMW DNA extraction requires a methodology that prioritizes the preservation of long fragments. This often means minimizing mechanical shearing and using purification methods designed for large molecules.

General Workflow and Best Practices

The entire process, from sample collection to storage, must be optimized for molecular integrity.

Best Practices for Handling HMW DNA:

- Minimize Shear Force: Avoid vortexing, pipetting up and down, or using narrow-bore pipette tips. Use wide-bore tips and mix by gentle inversion or end-over-end rotation [30].

- Optimize Lysis: For cell lysis, consider enzymatic treatments (e.g., lysozyme, proteinase K) over vigorous mechanical bead-beating to prevent DNA fragmentation [30].

- Proper Storage: Resuspend purified HMW DNA in TE buffer and store at 4°C for short-term use or -20°C for long-term storage to minimize degradation [27].

Benchmarking Extraction Methods for Metagenomics

The choice of extraction method significantly impacts HMW DNA yield, purity, and fragment length, which in turn dictates the success of long-read sequencing and de novo assembly. A benchmark study comparing six DNA extraction methods from human tongue scrapings provides valuable insights for complex samples [30].

Table 3: Benchmarking of HMW DNA Extraction Methods for Metagenomics

| Extraction Method | Lysis Mechanism | Key Findings & Suitability |

|---|---|---|

| Phenol-Chloroform (PC) | Chemical lysis (SDS/Proteinase K) | Traditionally considered the "gold standard" for generating the longest fragments from cultured cells. However, in metagenomic samples, it may be outperformed by modern column-based kits in terms of overall assembly performance and circularized element recovery [30]. |

| DNeasy PowerSoil (Standard) | Mechanical bead-beating | Commonly used but aggressive bead-beating causes significant DNA shearing, making it suboptimal for HMW DNA recovery [30]. |

| DNeasy PowerSoil (Modified) | Gentle mechanical lysis (low-speed shaking) | Reducing the bead-beating agitation speed and time minimizes velocity gradients and reduces DNA shearing, improving fragment length compared to the standard protocol [30]. |

| DNeasy PowerSoil (Enzymatic) | Enzymatic treatment (Lysozyme/Mutanolysin) | Fully replacing mechanical lysis with a heated enzymatic cocktail is highly effective for preserving HMW DNA from complex samples and is recommended for long-read metagenomics [30]. |

| MagMAX HMW DNA Kit | Bead-based purification (manual or automated) | Designed for fresh/frozen whole blood, cultured cells, and tissues. Optimized for use with KingFisher purification instruments, offering flexibility and consistency while minimizing user-induced shearing [26]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Equipment

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HMW DNA Extraction

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| MagMAX HMW DNA Kit | Magnetic bead-based kit for manual or automated purification of HMW DNA from blood, cells, and tissue. Yields a minimum of 3 µg of HMW gDNA [26]. |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit | A common kit for environmental samples; requires protocol modifications (enzymatic lysis or gentle bead-beating) to be effective for HMW DNA [30]. |

| KingFisher Purification System | Automated magnetic particle processor that minimizes user-error and manual handling, reducing the risk of shearing and improving consistency in HMW DNA isolations [26]. |

| Qubit Fluorometer & dsDNA BR Assay | Provides highly specific and accurate quantification of DNA mass, unaffected by common contaminants like RNA or salts, which is critical for library preparation [27]. |

| Agilent Femto Pulse System | Capillary electrophoresis system for accurately sizing DNA fragments >10 kb, essential for verifying HMW DNA integrity before long-read sequencing [27]. |

| Wide-Bore Pipette Tips | Tips with a larger orifice reduce fluid shear forces during pipetting, thereby preserving the long strands of HMW DNA [30]. |

| TE Buffer | A common elution and storage buffer (Tris-HCl, EDTA); EDTA chelates metal ions to inhibit DNases, protecting DNA integrity during storage [27]. |

| periplaneta-DP | Periplaneta-DP |

| ceh-19 protein | ceh-19 protein, CAS:147757-73-1, MF:C16H19NO5 |

Troubleshooting Common HMW DNA Extraction Challenges

Even with optimized protocols, challenges can arise. Here are common issues and their solutions, compiled from manufacturer and research guidelines.

Low DNA Yield

- Cause: Insufficient sample digestion or DNA loss during handling [26].

- Solution: Ensure complete tissue digestion by inverting tubes during incubation and checking for undigested pieces [26]. For manual isolations, carefully inspect pipette tips for sample retention. Using automated systems like the KingFisher can reduce handling losses [26].

Viscous DNA or Brown Eluent

- Cause: Viscosity indicates high molecular weight DNA, but can also be due to bead carryover. Brown color suggests contamination from heme (in blood samples) or other pigments [26].

- Solution: For viscous samples, use wide-bore tips and gently pipette. If using a manual magnetic bead-based kit, ensure beads are not overdried, as cracked beads indicate overdrying and can lead to lower yield and purity; air-dry at room temperature instead of using high heat [26].

Poor Purity (Low A260/280 or A260/230)

- Cause: Contamination with protein (low A260/280) or salts/organics (low A260/230) [27].

- Solution: Perform additional purification steps, such as a second round of precipitation or clean-up using a dedicated column. For blood samples, transfer the sample to a new tube after key wash steps to prevent carryover of contaminants [26].

The path to a successful de novo genome assembly, particularly one that aims to resolve complex genomic architectures, is paved with high-quality, high molecular weight DNA. The integrity of the starting material is a critical variable that directly influences assembly contiguity, the resolution of repetitive regions, and the accurate detection of structural variants. By adopting rigorous HMW DNA extraction protocols, implementing comprehensive quality control measures, and adhering to best practices for handling nucleic acids, researchers can ensure that their sequencing data provides a solid foundation for discovery. As genomic technologies continue to evolve, the principles of obtaining and preserving DNA integrity will remain a cornerstone of reliable and insightful genomic research.

The Illumina De Novo Assembly Workflow: From Raw Reads to Draft Genomes

Within the broader methodology for de novo genome assembly from Illumina reads, the initial preprocessing of raw sequencing data is a critical determinant of success. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies can generate billions of reads in a single run; however, this raw data invariably contains artifacts such as adapter sequences, low-quality bases, and technical contaminants [31]. These imperfections can severely compromise downstream assembly processes, leading to fragmented contigs and misassemblies. Therefore, rigorous quality control (QC) and read trimming are essential first steps to ensure the integrity and quality of the assembly. This protocol details a standardized workflow using two cornerstone tools: FastQC for quality assessment and Trimmomatic for read trimming and cleaning. We demonstrate how optimized trimming, validated through comparative analysis, directly benefits subsequent de novo transcriptome assembly, for instance, by improving metrics such as N50 and reducing the number of fragmented transcripts [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The following table catalogues the key software and data resources required to execute the quality control and preprocessing workflow.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Item Name | Type | Function/Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC [32] [33] | Software Tool | Provides an initial quality assessment of raw sequence data in FASTQ format, generating comprehensive reports on various metrics. |

| Trimmomatic [31] [34] [33] | Software Tool | Performs flexible trimming of adapters, low-quality bases, and short reads from FASTQ files. |

| Illumina Adapter Sequences (e.g., TruSeq3-PE.fa) [34] | Data File | A FASTA file containing common Illumina adapter sequences used by Trimmomatic to identify and remove adapter contamination. |

| Raw FASTQ Files [33] | Primary Data | The initial sequence data output from the Illumina sequencing platform, containing reads, quality scores, and metadata. |

| Reference Genome (Optional) [33] | Data File | A known genome sequence for the species, which can be used for alignment-based quality assessment post-trimming (not used in de novo assembly). |

| PPG-2 PROPYL ETHER | PPG-2 PROPYL ETHER, CAS:127303-87-1, MF:C31H38ClN3O14 | Chemical Reagent |

| MC-Val-Cit-PAB-VX765 | MC-Val-Cit-PAB-VX765, MF:C53H71ClN10O14, MW:1107.657 | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Initial Quality Assessment with FastQC

Principle: FastQC provides a modular suite of analyses to quickly assess whether your raw sequencing data has any problems before undertaking further analysis. It evaluates per-base sequence quality, GC content, adapter contamination, overrepresented sequences, and other metrics [32] [35].

Methodology:

- Software Installation: Install FastQC using the Bioconda package manager to ensure dependency resolution [33].

Data Preparation: Navigate to the directory containing your raw FASTQ files (e.g.,

*.fastq.gz). Ensure files are uncompressed if necessary usinggunzip[33].Report Generation: Run FastQC on all FASTQ files in the directory.

This command generates

.htmlreport files and.zipdirectories containing the raw data for each input file [32].Result Interpretation: Open the generated

.htmlreports in a web browser. Key modules to inspect include:- Per-base sequence quality: Identifies cycles where base quality drops, informing trimming parameters.

- Adapter content: Quantifies the proportion of adapter sequence in your data.

- Per-sequence quality scores: Flags individual reads of poor overall quality.

- Overrepresented sequences: Helps identify common contaminants.

Protocol 2: Read Trimming and Cleaning with Trimmomatic

Principle: Trimmomatic is a flexible, configurable tool used to remove technical sequences (adapters) and low-quality bases from sequencing reads. It can process both single-end and paired-end data, crucial for maintaining read-pair relationships in library preparation for de novo assembly [31] [34].

Methodology:

- Software and Adapter Installation: Install Trimmomatic and download the appropriate adapter file.

Trimming Execution (Paired-End Example): For each pair of reads, execute Trimmomatic with parameters optimized for Illumina data [34].

Parameter Explanation:

ILLUMINACLIP:TruSeq3-PE.fa:2:40:15: Removes adapter sequences with specified stringency and alignment scores [34].LEADING:2/TRAILING:2: Removes bases from the start/end of a read if below a specified quality threshold (Phred score of 2 in this case) [34].SLIDINGWINDOW:4:2: Scans the read with a 4-base wide sliding window, cutting when the average quality per base drops below 2 [34].MINLEN:25: Discards any reads shorter than 25 bases after trimming [34].

Integrated Workflow and Validation

The Complete Quality Control and Pre-processing Workflow

The entire procedure, from raw data to cleaned reads ready for assembly, follows a sequential path where the output of one tool informs the use of the next. The diagram below visualizes this integrated workflow and the logical relationships between the steps.

Trimmomatic's Internal Processing Logic

Trimmomatic applies its filtering steps in a sequential order, where the output of one step is passed to the next. Understanding this internal logic is key to configuring an effective trimming strategy. The following diagram details this process for a single read.

Validation and Quantitative Comparison

The efficacy of the trimming process must be validated by comparing quality metrics before and after processing. Re-running FastQC on the trimmed reads is essential to confirm the removal of adapters and improvement in per-base quality. Furthermore, the ultimate validation comes from downstream assembly performance.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Assembly Quality with Trimmed vs. Untrimmed Reads

| Assessment Metric | Untrimmed Reads | Trimmed Reads | Implication for De Novo Assembly |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adapter Content [31] | Present | Eliminated | Reduces misassembly and false overlaps. |

| Per-base Quality (Phred Score) [35] | Drops significantly at ends | Consistently high (>Q30) | Increases accuracy of base calling and overlap during assembly. |

| Number of Reads | Original count | Potentially reduced | Removal of poor-quality reads simplifies the assembly graph. |

| Assembly Contiguity (N50) [31] | Lower | Higher | Results in longer, more complete contigs. |

| Base Call Accuracy [36] | ~90% (Q10) | >99.9% (Q30) | Dramatically reduces errors in the consensus sequence. |

The quantitative data strongly supports the necessity of a rigorous trimming protocol. Studies have demonstrated that optimized read trimming directly leads to higher quality transcripts assembled using tools like Trinity, as evidenced by improved metrics when evaluated with Busco and Quast [31]. This underscores that the initial preprocessing steps, while computationally upstream, have a profound and measurable impact on the biological validity of the final de novo assembly.

In short-read de novo genome assembly, the immense challenge of reconstructing a complete genome from fragmented sequences is overcome through the strategic use of different sequencing libraries. While unpaired short reads can reconstruct continuous segments (contigs), they inevitably fall short in resolving repetitive genomic regions and establishing long-range connectivity [37]. Here, paired-end (PE) and mate-pair (MP) libraries become critical. These techniques sequence both ends of a DNA fragment, generating reads with a known approximate distance separating them, which provides essential long-range information for ordering and orienting contigs into larger structures called scaffolds [38] [39]. This document details the distinct roles, protocols, and applications of PE and MP libraries within the context of scaffolding for Illumina-based de novo assembly projects, providing a structured guide for researchers and drug development scientists.

Comparative Analysis of Paired-End and Mate-Pair Libraries

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and applications of paired-end and mate-pair libraries, highlighting their complementary roles in a sequencing project.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Paired-End and Mate-Pair Sequencing Libraries

| Feature | Paired-End (PE) Libraries | Mate-Pair (MP) Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role in Assembly | Contig building; resolution of small repeats; initial scaffolding [40]. | Long-range scaffolding; resolving large repeats; genome finishing [37] [39]. |

| Typical Insert Size | 200 bp - 800 bp [38]. | 2 kbp - 10 kbp or longer [37] [39]. |

| Library Prep Protocol | Simple, direct fragmentation of DNA, end-repair, and adapter ligation [38]. | Complex protocol involving circularization and fragmentation of large fragments to isolate and sequence the ends [39]. |

| Key Applications | - Accurate contig assembly- Detection of small indels and variants- Gene expression analysis (RNA-Seq) [38]. | - De novo sequencing- Scaffolding- Detection of complex structural variants [39]. |

| Information Provided | Short-range adjacency and orientation. | Long-range connectivity and contig ordering. |

Experimental Protocols for Library Preparation and Analysis

Paired-End Library Preparation Workflow

Paired-end sequencing is characterized by a relatively straightforward workflow that sequences both ends of short DNA fragments.

Diagram 1: PE library prep workflow.

The Illumina paired-end protocol begins with fragmentation of genomic DNA to a target size of 200-800 base pairs [38]. The fragments are then end-repaired to create blunt ends and A-tailed to facilitate adapter ligation. Illumina's proprietary paired-end adapters are subsequently ligated to the fragment ends. Following a size selection and purification step to ensure a tight insert size distribution, the final library is amplified via PCR and loaded onto a flow cell for cluster generation and sequencing. This process generates two reads from a single DNA fragment, one from each end, with a known approximate distance (insert size) between them [38].

Mate-Pair Library Preparation Workflow

Mate-pair library construction is a more complex process designed to capture the ends of long DNA fragments, ranging from several kilobases to tens of kilobases.

Diagram 2: MP library prep workflow.

The mate-pair protocol starts with fragmentation of high-molecular-weight DNA into large segments (2-10 kbp). These fragments undergo end-repair using biotin-labeled nucleotides. The repaired ends are then circularized via ligation, effectively joining the two ends of the original large fragment. Non-circularized DNA is removed by digestion, ensuring only the circularized molecules proceed. The circular DNA is then fragmented again, and the original fragment ends, which are now held together and labeled with biotin, are captured via affinity purification (e.g., using streptavidin beads). These purified ends are then ligated to standard Illumina paired-end adapters and sequenced [39]. The final data consists of read pairs that originated from ends of a long DNA fragment, providing long-range spatial information.

Bioinformatic Analysis and Scaffolding Workflow

The power of combining different libraries is realized during the bioinformatic scaffolding phase, where data from paired-end and mate-pair libraries are integrated to build a more complete genome assembly.

Diagram 3: Scaffolding workflow with PE and MP data.

The process begins with an initial de novo assembly of all high-quality reads (including single-end and paired-end) to produce a set of contigs [40]. The assembler uses the short-insert paired-end reads to resolve small repeats and build the most continuous sequences possible. The resulting contigs are then processed by a scaffolding algorithm, which uses the long-insert mate-pair data. The algorithm maps the mate-pair reads to the unique (non-repetitive) regions of the contigs. When a mate-pair is found where each read aligns to a different contig, it forms a "bridge," indicating that the two contigs are within the approximate insert size of the mate-pair library in the original genome [37] [41]. The scaffolder then uses this information to order and orient the contigs, inserting a stretch of 'N's to represent the gap between them, thus producing a longer scaffold. This process significantly reduces the number of disjoint sequences in the assembly and provides a map for further finishing efforts [41] [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful scaffolding relies on a combination of specialized library preparation kits and bioinformatic tools.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Scaffolding Projects

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Illumina Paired-End Kit | Standardized reagent kit for preparing short-insert (200-800 bp) paired-end sequencing libraries. Simplifies library construction and ensures high data quality [38]. |

| Nextera Mate-Pair Kit | Note: This kit has been discontinued by Illumina, but its protocol is representative of the method. It enabled the creation of long-insert mate-pair libraries through a circularization-based approach [39]. |

| SPAdes Assembler | A popular genome assembler that can natively handle hybrid datasets, combining short reads with long reads or mate-pairs for improved contig and scaffold construction [41]. |

| Velvet Assembler | One of the early short-read assemblers that supports the input of multiple library types, including paired-end and mate-pair, and uses this information for scaffolding [37] [40]. |

| npScarf | A scaffolder designed to use long reads (e.g., from Oxford Nanopore) in real-time to scaffold an existing short-read assembly, demonstrating the evolving nature of scaffolding techniques [41]. |

| Biotin-labeled Nucleotides | Critical reagents in mate-pair library prep for labeling the ends of large DNA fragments, enabling their selective purification after circularization and re-fragmentation [39]. |

| Chlorobenzuron | Chlorobenzuron, CAS:57160-47-1, MF:C14H10Cl2N2O2, MW:309.1 g/mol |

| Spermidic acid | Spermidic acid, CAS:4386-03-2, MF:C7H13NO4, MW:175.18 g/mol |

Strategic Application and Best Practices

Optimizing Library Choice for Repeat Resolution

The paramount challenge in assembly is resolving genomic repeats—nearly identical DNA segments that can be thousands of base-pairs long [37]. Without long-range information, assemblers collapse these repeats, creating fragmented assemblies. While high coverage with short reads is ineffective, mate-pairs are uniquely powerful for disambiguating these regions. Empirical studies suggest that the most effective strategy is to "tune" mate-pair libraries to the specific repeat structure of the target genome. A proposed two-tiered approach involves first generating a draft assembly with unpaired or short-insert reads to evaluate the repeat structure, then generating mate-pair libraries with insert sizes optimized to span the identified repeats [37]. This data-driven strategy is more cost-effective than a one-size-fits-all approach and can significantly reduce manual finishing efforts.

Quantitative Impact on Assembly Metrics

The effectiveness of scaffolding is quantitatively measured by key assembly statistics. The integration of mate-pair data leads to a direct and measurable improvement in assembly continuity.

Table 3: Quantitative Impact of Scaffolding on Assembly Quality

| Assembly Statistic | Definition | Impact from Mate-Pair Scaffolding |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Contigs | The total count of contiguous sequences in the assembly. | Dramatically decreases as contigs are joined into scaffolds [41]. |

| N50 Contig Size | The length of the shortest contig such that 50% of the genome is contained in contigs of that size or longer. | Increases significantly as scaffolding merges contigs into longer, ordered sequences [37] [41]. |

| N50 Scaffold Size | The length of the shortest scaffold such that 50% of the genome is contained in scaffolds of that size or longer. | The primary metric of improvement, showing a substantial increase with the use of mate-pair data [37]. |

| Assembly Completeness | The proportion of the reference genome or expected gene content covered by the assembly. | Improves as mate-pairs help place repetitive sequences and close gaps, leading to a more complete picture of the genome [41]. |

In summary, the strategic combination of paired-end and mate-pair libraries is fundamental to modern de novo genome assembly. While paired-end reads provide the foundation for accurate contig building, mate-pair reads are indispensable for long-range scaffolding, enabling the resolution of complex repeats and the reconstruction of large-scale genomic structures. By following the detailed protocols for library preparation and leveraging the appropriate bioinformatic tools for hybrid assembly, researchers can achieve more contiguous and complete genomes. This, in turn, provides a more reliable basis for downstream analyses in fields like comparative genomics, pathogen surveillance, and drug development, where understanding the complete genomic context is critical.