Decoding Histone Modifications: A Comprehensive Guide to ChIP-Seq Peak Analysis and Interpretation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on analyzing and interpreting ChIP-seq data for histone modifications.

Decoding Histone Modifications: A Comprehensive Guide to ChIP-Seq Peak Analysis and Interpretation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on analyzing and interpreting ChIP-seq data for histone modifications. It covers foundational concepts, from the biological role of histone marks like H3K4me3 in marking active transcription start sites to advanced methodological protocols optimized for challenging samples such as solid tissues. The content details critical steps for data quality control, including antibody validation and sequencing depth standards, and explores integrative analysis with transcriptomic data. Furthermore, it offers troubleshooting frameworks for common experimental challenges and compares ChIP-seq to emerging techniques like CUT&Tag. Concluding with future directions in quantitative epigenomics, this resource is designed to empower robust, reproducible chromatin profiling in biomedical research.

The Histone Code and ChIP-Seq: Foundational Principles of Epigenetic Mapping

In the nucleus of eukaryotic cells, DNA is packaged with histone proteins to form chromatin, the primary substrate for all DNA-templated processes. The fundamental unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, which consists of approximately 147 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of core histone proteins—two copies each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 [1] [2]. Each histone protein features a flexible N-terminal tail that protrudes from the nucleosome core and serves as a major site for post-translational modifications (PTMs) [2]. These modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and others that significantly alter chromatin structure and function without changing the underlying DNA sequence [1] [3] [4].

The "histone code" hypothesis proposes that these PTMs operate collectively to form a sophisticated regulatory system that governs chromatin accessibility and gene expression [5]. This code is not static but dynamically interpreted by cellular machinery through specific protein domains that recognize particular modification states [5]. Histone modifications regulate DNA accessibility by influencing how tightly histones bind to DNA and by recruiting non-histone proteins that further modify chromatin structure [1] [3]. The precise combinatorial patterns of these modifications ultimately determine whether a genomic region adopts an open (euchromatin) configuration permissive to transcription or a closed (heterochromatin) configuration that suppresses gene expression [3] [4]. This review explores the major types of histone modifications, their functional consequences, and their investigation through cutting-edge methodologies like ChIP-seq, with particular emphasis on their implications for disease and therapeutic development.

Major Types of Histone Modifications and Their Functional Consequences

Histone Acetylation

Histone acetylation, one of the most extensively studied modifications, involves the addition of an acetyl group to the ε-amino group of lysine residues in histone tails [1] [3]. This process is catalyzed by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and reversed by histone deacetylases (HDACs) [1] [2]. Acetylation neutralizes the positive charge on lysine residues, weakening electrostatic interactions between histones and negatively charged DNA backbone [3] [2]. This charge neutralization results in a more open chromatin structure (euchromatin) that facilitates transcription factor binding and gene activation [3] [2].

Notable acetyl marks include H3K9ac and H3K27ac, which are typically associated with active enhancers and promoters [3]. Histone acetylation is involved in diverse cellular processes including cell cycle regulation, proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, DNA replication, and repair [3]. An imbalance in histone acetylation dynamics is associated with various diseases, particularly cancer, making HATs and HDACs attractive therapeutic targets [3] [2].

Histone Methylation

Histone methylation occurs on both lysine and arginine residues and is regulated by histone methyltransferases (HMTs) and histone demethylases (HDMs) [1] [3]. Unlike acetylation, methylation does not alter histone charge but instead functions as a docking site for recruitment of specific effector proteins [3]. The functional outcome of lysine methylation depends on the specific residue modified and its methylation state (mono-, di-, or tri-methylation) [3] [5].

Table 1: Functional Roles of Major Histone Methylation Marks

| Histone Mark | Chromatin State | Genomic Location | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Euchromatin | Promoters | Transcriptional activation [3] [5] |

| H3K4me1 | Euchromatin | Enhancers | Primed enhancer marking [3] [5] |

| H3K36me3 | Euchromatin | Gene bodies | Transcriptional elongation [3] [5] |

| H3K27me3 | Facultative heterochromatin | Promoters in gene-rich regions | Repression of developmental genes [3] [5] |

| H3K9me3 | Constitutive heterochromatin | Satellite repeats, telomeres | Permanent silencing [3] [5] |

Methylation marks demonstrate remarkable functional specificity. For example, H3K27me3 is a repressive mark deposited by Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) that temporarily silences developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells, while H3K9me3 is a more permanent repressive mark associated with constitutive heterochromatin formation in gene-poor regions [3]. The discovery of histone demethylases confirmed that histone methylation is a dynamically reversible process, overturning the previous paradigm that these were permanent modifications [1].

Phosphorylation, Ubiquitination, and Other Modifications

Beyond acetylation and methylation, histones undergo several other important modifications:

Phosphorylation: Addition of phosphate groups to serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues primarily regulates chromosome condensation during cell division, DNA damage response, and transcription [3]. For instance, phosphorylation of H3S10 and H3S28 is crucial for chromatin condensation during mitosis, while H2AXS139ph (γH2AX) serves as an early marker of DNA double-strand breaks, recruiting repair proteins [3].

Ubiquitination: Monoubiquitination of H2B (typically at K120 in vertebrates) is associated with transcriptional activation and stimulates downstream histone methylation such as H3K4me3 [1]. Conversely, monoubiquitination of H2A (often at K119) is linked to transcriptional repression [3].

Other modifications: These include SUMOylation, ADP-ribosylation, citrullination, and crotonylation, whose functions are still being elucidated but contribute to the complexity of the histone code [1] [3].

These modifications often function combinatorially. For example, the combination of H3S10 phosphorylation and H3K14 acetylation is a hallmark of active transcription [5]. This crosstalk between different modification types creates a sophisticated regulatory network that fine-tunes chromatin structure and function.

Histone Modifications and Gene Expression: Mechanisms and Relationships

Histone modifications regulate gene expression through two primary mechanisms: by directly influencing chromatin physical properties and by serving as recruitment platforms for non-histone proteins.

The direct mechanism is best exemplified by histone acetylation. By neutralizing positive charges on histone tails, acetylation reduces histone-DNA binding affinity, leading to chromatin decompaction that increases DNA accessibility to transcriptional machinery [3] [2]. This open conformation allows transcription factors, co-activators, and RNA polymerase II to access regulatory sequences and initiate transcription [2].

The recruitment mechanism involves specific "reader" proteins that recognize particular modification states and subsequently influence transcriptional outcomes. For example, repressive marks like H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 are recognized by HP1 and Polycomb proteins, respectively, which promote chromatin condensation and gene silencing [1] [6]. Conversely, active marks such as H3K4me3 is recognized by factors that promote transcription initiation [6].

Different histone modifications characterize distinct functional elements across the genome:

- Active promoters are typically marked by H3K4me3 and harbor acetylation marks like H3K9ac and H3K27ac [3] [5].

- Active enhancers are characterized by H3K27ac and H3K4me1 [3] [5].

- Transcribed gene bodies show enrichment of H3K36me3 [3] [5].

- Repressed regions contain H3K27me3 (facultative heterochromatin) or H3K9me3 (constitutive heterochromatin) [3] [5].

Quantitative relationships exist between histone modification levels and gene expression. Computational models using support vector regression can predict gene expression levels from histone modification patterns with high accuracy (correlation coefficient r ≈ 0.75) [6]. Interestingly, different histone marks show varying predictive power for genes with different promoter types; H3K27ac and H4K20me1 are most predictive for high-CpG promoters, while H3K4me3 and H3K79me1 are most predictive for low-CpG promoters [6].

The relationship between histone modifications and transcription can be bidirectional. While some modifications directly regulate transcription, others are consequences of transcriptional activity. For instance, H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 are deposited by complexes associated with RNA polymerase II during transcription elongation, creating a memory of recent transcriptional activity [6].

Investigating Histone Modifications: ChIP-Seq Methodology and Analysis

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is the cornerstone technology for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications and transcription factor binding sites [7]. This method provides high-resolution data on protein-DNA interactions, enabling researchers to capture epigenetic landscapes and gene regulatory networks [7].

ChIP-Seq Experimental Workflow

The standard ChIP-seq protocol involves multiple critical steps:

Cross-linking: Cells are treated with formaldehyde to covalently cross-link proteins to DNA, preserving in vivo protein-DNA interactions [7].

Chromatin Fragmentation: Chromatin is sheared into small fragments (200-600 bp) typically by sonication or enzymatic digestion [7].

Immunoprecipitation: An antibody specific to the histone modification of interest is used to precipitate the protein-DNA complexes. Antibody specificity is crucial for experiment success [7].

Cross-link Reversal and Purification: Cross-links are reversed, and the immunoprecipitated DNA is purified [7].

Library Preparation and Sequencing: DNA fragments are prepared into a sequencing library and analyzed by high-throughput sequencing [7].

Computational Analysis: Sequencing reads are aligned to a reference genome, and enriched regions ("peaks") are identified through bioinformatic analysis [7].

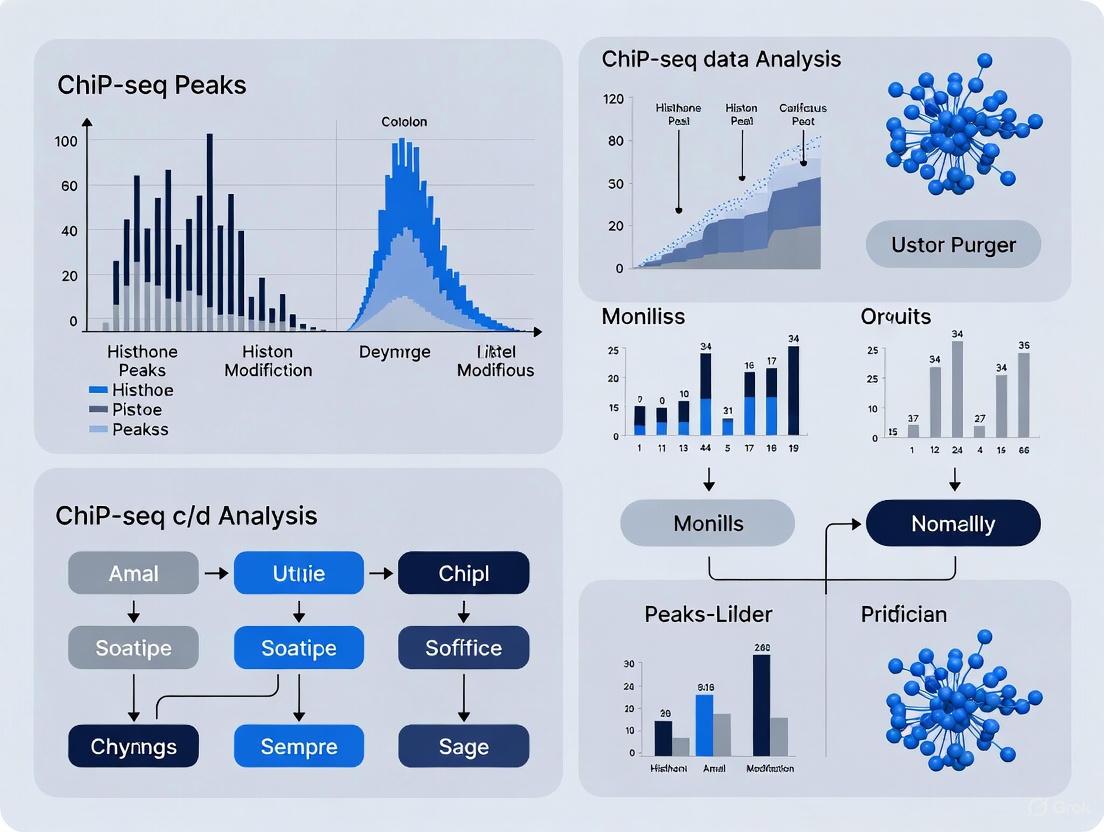

ChIP-Seq Data Analysis Pipeline

ChIP-seq data analysis involves a multi-step computational pipeline:

Quality Control: Assess sequence quality using tools like FastQC to evaluate base quality scores, GC content, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences. Low-quality reads may be trimmed or removed [7].

Alignment: Map sequencing reads to a reference genome using aligners such as Bowtie or BWA [7].

Duplicate Removal: Remove PCR duplicates using tools like Picard to avoid amplification biases. The Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) should be evaluated, with ideal experiments having less than three reads per position [7].

Peak Calling: Identify statistically significantly enriched regions using algorithms like MACS2 (Model-based Analysis of ChIP-Seq). This step typically involves comparison with input control samples to distinguish specific enrichment from background [7].

Annotation and Visualization: Annotate peaks with genomic features (promoters, enhancers, gene bodies) and visualize results using genome browsers like IGV or through enrichment plots and heatmaps [7].

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for ChIP-seq Analysis

| Analysis Step | Common Tools | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastQC | Assess sequence quality metrics [7] |

| Read Alignment | Bowtie, BWA | Map sequences to reference genome [7] |

| Duplicate Removal | Picard | Remove PCR-amplified duplicates [7] |

| Peak Calling | MACS2 | Identify significantly enriched regions [7] |

| Data Visualization | IGV, deepTools | Visualize enrichment across genome [7] |

Proper experimental design is crucial for robust ChIP-seq results. Key considerations include using appropriate biological replicates, including matched input controls, optimizing antibody specificity, and ensuring sufficient sequencing depth [7]. Recent technological advances have enabled single-cell histone modification profiling methods such as scChIP-seq and multi-modal techniques that simultaneously measure multiple epigenetic features and transcriptomes in individual cells [8].

Research Applications and Therapeutic Implications

Histone modification profiling provides critical insights into normal development and disease pathogenesis. In cancer research, epigenetic alterations are now recognized as fundamental hallmarks [9]. Mass spectrometry-based profiling of breast cancer samples has revealed distinct histone modification signatures that discriminate molecular subtypes [9]. Specifically, triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) exhibit unique epigenetic patterns characterized by increased H3K4 methylation (H3K4me1/me2/me3), elevated H3K9me3 and H3K36 methylation, and decreased H3K27me3 and H4K16ac [9].

Functionally, increased H3K4me2 in TNBCs sustains the expression of genes associated with the aggressive TNBC phenotype. CRISPR-mediated epigenome editing has established a causal relationship between H3K4me2 and gene expression for specific targets, while treatment with H3K4 methyltransferase inhibitors reduces TNBC cell growth in vitro and in vivo, suggesting novel therapeutic avenues [9].

In allergic diseases, histone modifications regulate the development and function of immune cells involved in allergic inflammation [10]. For example, HATs and HDACs modulate the expression of cytokines and other mediators of allergic responses, while HMTs and HDMs influence T-cell differentiation toward allergic phenotypes [10]. These findings have spurred development of epigenetic therapies targeting histone-modifying enzymes.

The reversible nature of epigenetic modifications makes them attractive therapeutic targets. Several HDAC inhibitors are already approved for cancer treatment, and inhibitors targeting HMTs, HDMs, and other histone-modifying enzymes are in clinical development [9]. Furthermore, epigenetic patterns show promise as diagnostic tools for classifying disease subtypes and predicting clinical outcomes [10] [9].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Histone Modification Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Modification-Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation and detection of specific histone marks | Validated antibodies for ChIP-seq (e.g., anti-H3K4me3, anti-H3K27ac) [7] |

| Histone Modifying Enzyme Inhibitors | Chemical perturbation of histone modification states | HDAC inhibitors (vorinostat), HMT inhibitors [9] |

| Spike-in Standards | Normalization for quantitative epigenomics | Heavy-isotope labeled histones for mass spectrometry [9] |

| Chromatin Shearing Reagents | Fragmentation of chromatin for ChIP-seq | Sonication equipment or enzymatic shearing kits [7] |

| Single-Cell Multi-omics Platforms | Simultaneous profiling of multiple histone marks and transcriptomes | scMTR-seq for 6 histone modifications + transcriptome [8] |

| CRISPR Epigenome Editing Systems | Targeted manipulation of histone modifications | CRISPR/dCas9 fused to histone modifying domains [9] |

Histone modifications represent a crucial layer of epigenetic regulation that dynamically controls chromatin state and gene expression. The combinatorial nature of these modifications forms a sophisticated "histone code" that integrates internal and external signals to fine-tune genomic function. Advanced technologies like ChIP-seq and single-cell multi-omics have enabled comprehensive mapping of these epigenetic landscapes across diverse biological contexts. The emerging understanding of histone modification roles in diseases, particularly cancer, has revealed new therapeutic opportunities through targeting histone-modifying enzymes. As epigenetic profiling becomes increasingly integrated into clinical research, histone modifications promise to yield valuable biomarkers for diagnosis and patient stratification, ultimately paving the way for personalized epigenetic therapies.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is a powerful method for identifying genome-wide DNA binding sites for transcription factors and other proteins, providing critical insights into gene regulation events that play roles in various diseases and biological pathways [11]. By combining chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays with massively parallel sequencing, ChIP-seq enables thorough examination of interactions between proteins and nucleic acids on a genome-wide scale, offering an unbiased approach that requires no prior knowledge of target sequences [11]. For researchers studying histone modifications—a cornerstone of epigenetics—ChIP-seq has become an indispensable technique for mapping the genomic locations of post-translational modifications that govern chromatin structure and transcriptional activity [12] [13]. When framed within the context of a broader thesis on understanding ChIP-seq peaks for histone modifications research, mastering this workflow is essential for generating robust, interpretable data that can reveal the epigenetic mechanisms underlying development, disease progression, and potential therapeutic interventions.

Fundamental Principles of ChIP-seq

At its core, ChIP-seq captures a snapshot of specific protein-DNA interactions in live cells [14]. The fundamental principle relies on the ability to cross-link proteins to DNA, preserving these interactions in their native state before immunoprecipitation with specific antibodies [13]. For histone modification studies, this typically involves targeting specific post-translational modifications such as methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, or ubiquitination marks on histone proteins [14] [13].

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and histone proteins that packages the genome into nucleosomes, allowing approximately two meters of DNA to fit inside a cell's nucleus [14] [13]. The nucleosome consists of a histone octamer core around which DNA wraps, with histone H1 acting as a linker [14]. Histone modifications influence whether chromatin is tightly packed (heterochromatin) or relaxed (euchromatin), directly affecting gene accessibility and expression [13]. Unlike transcription factors that typically bind DNA in a punctate manner, histone modifications often associate with DNA over longer genomic regions, requiring specific analytical approaches for accurate peak calling and interpretation [12] [15].

A key advantage of ChIP-seq over other epigenetic profiling methods is its genome-wide coverage without the inherent bias of array-based approaches that require probes derived from known sequences [11]. This unbiased nature makes it particularly valuable for discovering novel regulatory elements and understanding the full complexity of epigenetic regulation in health and disease.

Experimental Workflow

Step 1: Crosslinking

The ChIP-seq procedure begins with covalent stabilization of protein-DNA complexes using crosslinking agents [14]. Formaldehyde is most commonly used as it effectively penetrates intact cells and locks protein-DNA complexes together, preserving even transient interactions [14] [13]. For higher-order interactions or complex quaternary structures, longer crosslinkers such as ethylene glycol bis(succinimidyl succinate) (EGS) or disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG) may be employed alongside formaldehyde [14].

The duration of crosslinking requires careful optimization—too little results in inefficient stabilization, while excessive crosslinking can mask antibody epitopes and prevent effective chromatin shearing [14] [16]. Typical crosslinking times range from 2-30 minutes, after which the reaction is terminated by adding glycine [13]. For highly stable histone-DNA interactions, native ChIP (N-ChIP) without crosslinking can be performed, preserving more biologically relevant interactions though it is generally unsuitable for non-histone proteins [13].

Critical Considerations:

- Crosslinking conditions must be optimized for each cell type and target

- Excessive crosslinking reduces antigen accessibility and shearing efficiency

- Native ChIP is an option for stable histone-DNA interactions without crosslinking [13]

Step 2: Cell Lysis and Chromatin Extraction

Following crosslinking, cell membranes are dissolved with detergent-based lysis solutions to liberate cellular components [14]. Since protein-DNA interactions occur primarily in the nucleus, removing cytosolic proteins can reduce background signal and increase sensitivity [14]. Protease and phosphatase inhibitors are essential at this stage to maintain intact protein-DNA complexes throughout the procedure [14].

Successful cell lysis can be visualized microscopically by examining samples before and after lysis using a hemocytometer [14]. The extent of lysis varies by cell type, with difficult-to-lyse cells potentially requiring increased incubation time in lysis buffer, brief sonication, or glass dounce homogenization [14].

Step 3: Chromatin Fragmentation (Shearing/Digestion)

The extracted genomic DNA must be fragmented into smaller, workable pieces for analysis. Ideal chromatin fragment sizes range from 200-700 base pairs, with mononucleosome-sized fragments (150-300 bp) providing optimal resolution [14] [16]. Fragmentation can be achieved either mechanically by sonication or enzymatically using micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion [14].

Sonication provides truly randomized fragments but requires dedicated equipment and extensive optimization [14]. Limitations include difficulty maintaining temperature during sonication and extended hands-on time. MNase digestion is more reproducible and amenable to processing multiple samples but has higher affinity for internucleosome regions, resulting in less random fragmentation [14] [16]. Excessive fragmentation disrupts target interactions and reduces ChIP yields, while insufficient fragmentation (>600-700 bp) lowers resolution and makes precise localization of proteins or histone modifications difficult [16].

Critical Considerations:

- Fragmentation size directly impacts resolution and data quality

- Balance must be struck between sufficient fragmentation and preserving protein-DNA interactions

- Fragmentation conditions must be re-optimized for new cell types or protocol changes [16]

Step 4: Immunoprecipitation

Sheared chromatin is incubated with a primary antibody specific to the protein or histone modification of interest [16]. Antibody selection is arguably the most critical factor in ChIP-seq success—the antibody must efficiently capture its target with minimal cross-reactivity [14] [16]. For histone modifications, antibodies with high specificity are essential because related marks (e.g., H3K9me2 vs. H3K9me1) can have opposing effects on gene expression [14].

Monoclonal, oligoclonal, and polyclonal antibodies can all work in ChIP, with polyclonals often providing better epitope recognition [14]. For histone PTMs, antibodies notoriously show high cross-reactivity, potentially misleading biological conclusions [16]. Including negative control reactions using non-specific IgG antibodies is strongly recommended to assess background signal, along with positive control antibodies (e.g., H3K4me3) when possible [16].

Following overnight incubation at 4°C, the antibody is coupled to magnetic beads coated with protein A and/or G (depending on antibody isotype) to facilitate immunoprecipitation [16]. The antibody-bound chromatin is then isolated using a magnet, followed by stringent washes with buffers containing progressively higher salt and detergent concentrations to reduce off-target binding [16].

Step 5: DNA Purification and Quality Control

The target-enriched chromatin is treated with Proteinase K to digest proteins, RNase A to degrade RNA, and high salt with heat to reverse cross-links [16]. ChIP DNA is then purified using standard DNA purification methods. DNA concentration is assessed by spectrophotometric or fluorometric analysis, while fragment size distribution is confirmed by agarose gel or capillary electrophoresis [16].

It is essential to confirm that ChIP DNA is enriched for mononucleosome-sized fragments rather than very short or long pieces to ensure successful downstream analysis [16]. The input control (aliquot of fragmented chromatin set aside before immunoprecipitation) is processed alongside for quality control assessment and enrichment comparisons [16].

Step 6: Library Preparation and Sequencing

For sequencing, additional steps are required to prepare ChIP DNA for next-generation sequencing platforms [16]. ChIP DNA and input DNA are repaired and amplified, with distinct indexes (barcodes) added to each library during PCR to enable multiplexed sequencing [16]. Prepared libraries are quantified, and size distribution is confirmed before pooling at equimolar ratios and loading onto the sequencing platform [16].

Sequencing depth requirements vary significantly based on the target. Transcription factors may require only 5-15 million reads, while ubiquitous proteins such as histone marks typically need ~50 million reads for comprehensive coverage [11]. The ENCODE consortium provides specific standards, recommending 20 million usable fragments per replicate for narrow histone marks and 45 million for broad marks, with H3K9me3 as a notable exception requiring special consideration due to enrichment in repetitive regions [12].

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow:

Data Processing and Analysis

Primary Data Processing

ChIP-seq data processing begins with quality assessment of raw sequencing data using tools like FastQC [17] [18]. Adapter sequences and low-quality bases are trimmed using tools such as Trimmomatic, followed by alignment to a reference genome using aligners like BWA-MEM or Bowtie2 [19] [17]. The resulting SAM files are converted to BAM format, sorted, and indexed using Samtools [17].

Quality control is essential at this stage, with metrics including strand cross-correlation analysis, which calculates the Pearson's linear correlation between tag density on forward and reverse strands after shifting [18]. High-quality ChIP-seq experiments produce significant clustering of enriched DNA sequence tags at protein-binding locations, with forward and reverse strand densities centered around binding sites [18].

Peak Calling and Annotation

Peak calling identifies genomic regions with significant enrichment of immunoprecipitated DNA fragments compared to background. The ENCODE consortium provides distinct pipelines for transcription factors (punctate binding) and histone modifications (broader domains) [12] [15]. For histone modifications, specialized tools that account for broader enrichment patterns are essential [12].

Common peak callers include MACS2, HOMER, and SICER, with HOMER offering histogram-based peak modeling to reduce false positives [17]. Following peak calling, genomic annotation identifies the location of peaks relative to genes (promoters, enhancers, exons, introns, intergenic regions), while motif discovery can reveal enriched transcription factor binding sites within peaks [17].

Normalization and Quantitative Comparisons

Comparing ChIP-seq signals across samples requires careful normalization to address variability from factors such as cell state, cross-linking efficiency, fragmentation, and sequencing depth [19]. While spike-in normalization (adding exogenous chromatin as a reference) has been used, recent methods like sans spike-in quantitative ChIP (siQ-ChIP) provide mathematically rigorous alternatives for quantifying absolute IP efficiency genome-wide without external controls [19].

For relative comparisons, normalized coverage approaches are recommended, enabling comparisons of protein distributions within and across samples while accounting for technical variability [19]. These normalization strategies are particularly important for histone modification studies where quantitative comparisons between conditions are essential for drawing biological conclusions.

The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow:

Quality Control and Standards

Experimental QC Metrics

Comprehensive quality control is essential for generating robust ChIP-seq data. The ENCODE consortium has established rigorous standards, including:

- Library Complexity: Measured using Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) and PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients (PBC1 and PBC2), with preferred values of NRF>0.9, PBC1>0.9, and PBC2>10 [12] [15]

- FRiP Score: Fraction of Reads in Peaks, measuring enrichment over background [12] [15]

- Strand Cross-Correlation: Assessing the periodicity of forward and reverse strand tags [18]

- Replicate Concordance: For transcription factors, measured by Irreproducible Discovery Rate (IDR) [15]

Sequencing Depth Requirements

Table 1: ENCODE Sequencing Depth Standards for ChIP-seq Experiments

| Target Type | Minimum Usable Fragments per Replicate | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors | 20 million | REST, Sox9 [15] |

| Narrow Histone Marks | 20 million | H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K9ac [12] |

| Broad Histone Marks | 45 million | H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K79me2 [12] |

| H3K9me3 Exception | 45 million | Special case due to repetitive region enrichment [12] |

Best Practices

The ENCODE consortium recommends several best practices for rigorous ChIP-seq experiments:

- Biological Replicates: At least two biological replicates (independently collected samples) to ensure reproducibility [12] [16] [15]

- Control Experiments: Input DNA controls (non-immunoprecipitated) with matching run type, read length, and replicate structure [12] [14]

- Antibody Validation: Antibodies must be characterized according to established standards, with preference for ChIP-grade validated reagents [12] [15]

- Metadata Audits: Complete experimental metadata must pass routine audits before data release [12]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for ChIP-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Examples & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Crosslinking Agents | Stabilize protein-DNA interactions | Formaldehyde (most common), EGS, DSG for higher-order complexes [14] |

| Cell Lysis Buffers | Dissolve membranes, liberate cellular components | Detergent-based solutions with protease/phosphatase inhibitors [14] |

| Chromatin Shearing Reagents | Fragment DNA to optimal sizes | Sonication equipment or Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) for enzymatic digestion [14] [16] |

| Target-Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitate protein-DNA complexes | ChIP-grade validated antibodies; polyclonals often preferred for epitope access [14] [16] |

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | Recover antibody-bound complexes | Bead type selection depends on antibody isotype [16] |

| DNA Purification Kits | Isolate DNA after reverse crosslinking | Standard molecular biology kits with RNase and Proteinase K treatment [16] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries | Include end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, and index incorporation [11] [16] |

| Quality Control Instruments | Assess DNA quality and quantity | Spectrophotometers, fluorometers, capillary electrophoresis systems [16] |

| (R)-Camazepam | (R)-Camazepam, CAS:102838-65-3, MF:C19H18ClN3O3, MW:371.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Z7Dnn9U8AE | Z7Dnn9U8AE, CAS:406483-39-4, MF:C20H24O4, MW:328.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Considerations for Histone Modification Studies

Normalization Challenges

Histone modification studies present unique normalization challenges due to the global nature of many marks. Unlike transcription factors that bind specific sites, histone modifications can affect large chromatin domains, making traditional normalization approaches insufficient [19]. The siQ-ChIP method addresses this by measuring absolute IP efficiency genome-wide, providing a rigorous foundation for quantitative comparisons without relying on spike-in controls [19].

Emerging Technologies

While ChIP-seq remains the gold standard for histone modification mapping, emerging technologies like CUT&Tag offer potential advantages in specific applications. Recent benchmarking studies show that CUT&Tag recovers approximately 54% of ENCODE ChIP-seq peaks for histone modifications like H3K27ac and H3K27me3, with detected peaks representing the strongest ENCODE peaks and showing similar functional enrichments [20]. CUT&Tag offers significantly reduced cellular input requirements (200-fold less) and lower sequencing depth needs, making it particularly valuable for rare cell populations or single-cell applications [20].

Data Integration

For comprehensive epigenetic studies, ChIP-seq data is increasingly integrated with complementary datasets, including:

- RNA-seq: Correlating histone modifications with gene expression changes [11]

- ATAC-seq: Assessing chromatin accessibility patterns [11]

- Methylation Sequencing: Profiling DNA methylation alongside histone modifications [11]

- Hi-C/ChIA-PET: Understanding 3D chromatin organization [13]

This integrated approach provides a more complete understanding of the epigenetic landscape and its functional consequences.

The ChIP-seq workflow represents a sophisticated but manageable process that, when executed with careful attention to quality control and established standards, generates invaluable data for histone modification research. From appropriate experimental design and antibody selection through rigorous computational analysis, each step influences the final data quality and biological interpretability. As part of a broader thesis on understanding ChIP-seq peaks for histone modifications, mastering this technique provides a powerful tool for uncovering the epigenetic mechanisms governing gene regulation in development, disease, and therapeutic interventions. With emerging technologies and analysis methods continuing to evolve, ChIP-seq remains a cornerstone of epigenomic research, enabling increasingly precise mapping of the complex regulatory landscape that coordinates cellular function.

The genomic DNA of eukaryotic cells is packaged into chromatin, a complex structure where DNA is wrapped around histone proteins to form nucleosomes. The core nucleosome consists of an octamer of histones (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4), around which approximately 180 base pairs of DNA are wound [21] [22]. The N-terminal tails of these histones undergo various post-translational modifications (PTMs), including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitylation. These modifications constitute a critical layer of epigenetic regulation that influences chromatin structure and gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [23]. Among these PTMs, histone methylation plays particularly crucial roles in directing transcriptional outcomes and maintaining cellular identity.

Two of the most extensively studied histone methylation marks are trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) and lysine 27 (H3K27me3). These modifications represent opposing transcriptional signals: H3K4me3 is predominantly associated with gene activation, while H3K27me3 is linked to gene repression [21] [22]. The precise interpretation of these marks, especially in the context of chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) data, is fundamental to epigenetics research. Their balanced regulation is essential for normal development, cell differentiation, and disease prevention, making them critical subjects for researchers and drug development professionals working in epigenetic therapeutics [24] [25].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3, exploring their molecular mechanisms, functional roles in gene regulation, and the experimental approaches used to study them. Framed within the broader context of interpreting ChIP-seq data for histone modification research, this review synthesizes current understanding with emerging insights into how these marks coordinate to regulate genome function in health and disease.

Molecular Mechanisms and Genomic Distributions

H3K4me3: An Activation Mark with Complex Regulation

H3K4me3 is an epigenetic modification indicating trimethylation of the fourth lysine residue on the histone H3 protein [21]. This mark is created by lysine-specific histone methyltransferase complexes, often containing WDR5, which facilitates further methylation by methyltransferases [21]. H3K4me3 is one of the least abundant histone modifications but is highly enriched at active promoters near transcription start sites (TSS) and is positively correlated with transcription activity [21].

Traditional understanding posited H3K4me3 as a simple activator of gene expression. However, recent studies have revealed more nuanced roles. While it does promote gene activation through chromatin remodeling complexes like NURF, which makes DNA more accessible for transcription factors [21], its presence alone does not always correlate directly with transcriptional levels. Instead, the breadth of H3K4me3 domains appears to carry significant biological information. Notably, genes marked by exceptionally broad H3K4me3 domains (spanning up to 60kb) in a particular cell type are often essential for that cell's identity and function, and they exhibit enhanced transcriptional consistency rather than merely increased transcriptional levels [26].

H3K27me3: A Repressive Mark with Developmental Significance

H3K27me3 indicates trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 and functions as a repressive mark associated with the formation of heterochromatic regions [22]. This modification is catalyzed by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), whose core components include enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), embryonic ectoderm development (EED), and suppressor of zeste 12 homolog (SUZ12) [23]. The PRC2 complex requires all three core components to function effectively in depositing the H3K27me3 mark [23].

Once established, H3K27me3 can recruit PRC1, which contributes to further chromatin compaction and stabilization of the repressed state [22]. This repressive mark is not permanent or irreversible; it can be removed by specific demethylases such as UTX and JMJD3, allowing for reactivation of genes when needed [23]. H3K27me3 is dynamically remodeled during early embryonic development, where it undergoes global erasure from parental genomes to remove gametic epigenetic programs and establish a pluripotent embryonic epigenome [23].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3

| Feature | H3K4me3 | H3K27me3 |

|---|---|---|

| Associated Function | Gene activation [21] | Gene repression [22] |

| Primary Genomic Location | Active promoters near transcription start sites [21] | Repressed developmental genes; forms broad repressive domains [22] [27] |

| Writer Complex | COMPASS/SET1/MLL complexes containing WDR5 [21] | Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) [23] [22] |

| Eraser Enzymes | KDM5 family demethylases [24] | UTX (KDM6A), JMJD3 (KDM6B) [23] |

| Reader Domains | PHD finger domains [21] | Chromodomains in PRC1 [22] |

| Role in Development | Regulates stem cell potency and lineage commitment [21] | Silences key developmental genes; maintains cellular memory [23] [22] |

| Transcriptional Output | Promotes transcriptional consistency [26] | Establishes facultative heterochromatin [22] |

Functional Roles in Gene Regulation and Cellular Processes

Transcriptional Regulation and Bivalent Domains

H3K4me3 plays critical roles in regulating multiple phases of transcription, including RNA polymerase II initiation, pause-release, and transcriptional consistency [24]. Recent research has revealed that H3K4me3 breadth contains information that ensures transcriptional precision at key cell identity genes [26]. Rather than simply increasing transcriptional levels, broad H3K4me3 domains are associated with reduced transcriptional variability, providing consistent expression of genes essential for cellular function and identity.

A particularly significant phenomenon occurs in embryonic stem cells, where H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 co-localize in what are termed "bivalent domains" [21] [22]. These domains simultaneously harbor both activating and repressing histone modifications, creating a poised transcriptional state that allows developmental genes to be rapidly activated or permanently silenced as cells differentiate [21]. This bivalent configuration provides plasticity during development, maintaining genes in a transcriptionally poised state that can be resolved toward full activation or stable repression depending on developmental cues.

Diagram 1: Bivalent chromatin resolution during differentiation. Short title: Bivalent domain resolution.

Roles in Development, Differentiation, and Disease

Both H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 play crucial roles in development and differentiation. H3K4me3 regulation is essential for normal development and preventing disease, with somatic alterations in genes regulating H3K4 methylation being common in cancer [24]. The broadest H3K4me3 domains in a given cell type preferentially mark genes essential for the identity and function of that cell type, serving as an excellent discovery tool for identifying novel regulators of specific cell types [26].

H3K27me3 is similarly crucial for developmental processes, silencing the expression of key developmental genes during embryonic stem cell differentiation [23]. Its dynamic regulation during pre-implantation development is essential for reprogramming the parental genomes to establish totipotency. Disruption of normal H3K27me3 patterns can lead to developmental disorders and cancer. For instance, diffuse midline glioma, a highly aggressive childhood brain tumor, is characterized by mutations in histone H3 genes (H3K27M) that cause a global reduction in H3K27me3 [22].

H3K27me3-rich regions (MRRs) can function as silencers to repress gene expression via chromatin interactions [27]. These MRRs show dense chromatin interactions connecting to target genes and to other MRRs, and their CRISPR excision leads to gene up-regulation, changes in chromatin loops, histone modifications, and altered cell phenotypes including changes in cell adhesion, growth, and differentiation [27].

DNA Damage Repair

Beyond their roles in transcriptional regulation, both H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 participate in DNA damage repair processes. H3K4me3 is present at sites of DNA double-strand breaks, where it promotes repair by the non-homologous end joining pathway [21]. The binding of H3K4me3 is necessary for the function of tumor suppressors like inhibitor of growth protein 1 (ING1), which enact DNA repair mechanisms [21]. Similarly, H3K27me3 has been linked to the repair of DNA damages, particularly the repair of double-strand breaks by homologous recombinational repair [22].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Histone Modifications

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is the method of choice for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications and transcription factor binding sites [28]. This method involves covalently crosslinking proteins to DNA in living cells, followed by chromatin fragmentation, immunoprecipitation with antibodies specific to the histone modification of interest, and high-throughput sequencing of the associated DNA [28].

The ENCODE consortium has established comprehensive standards and pipelines for histone ChIP-seq data processing [12]. The histone analysis pipeline can resolve both punctate binding and longer chromatin domains, with outputs including fold change over control tracks, signal p-value tracks, and replicated peak calls [12]. According to ENCODE standards, broad-peak histone marks like H3K27me3 require 45 million usable fragments per replicate, while narrow-peak marks like H3K4me3 require 20 million usable fragments per replicate [12].

Diagram 2: ChIP-seq workflow for histone modifications. Short title: Histone ChIP-seq workflow.

Complementary Methodologies

Several complementary methods provide additional insights into chromatin architecture and histone modifications:

- Micrococcal Nuclease sequencing (MNase-seq) investigates regions bound by well-positioned nucleosomes by employing micrococcal nuclease to identify nucleosome positioning [21] [22].

- Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin sequencing (ATAC-seq) identifies nucleosome-free regions (open chromatin) using a hyperactive Tn5 transposon to highlight nucleosome localization [21] [22].

- Chromatin Interaction Analysis with Paired-End Tag sequencing (ChIA-PET) can capture long-range chromatin interactions mediated by specific protein factors, providing insights into how histone modifications influence 3D genome organization [27].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Studying Histone Modifications

| Method | Application | Key Output | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-seq [28] | Genome-wide mapping of histone modifications | Peak calls, signal tracks | Requires high-quality antibodies; broad and narrow marks need different sequencing depths [12] |

| CUT&RUN [25] | Mapping with lower cell input requirements | Similar to ChIP-seq | Lower background signal; suitable for limited samples |

| ATAC-seq [21] [22] | Identifying accessible chromatin regions | Nucleosome positioning, accessibility peaks | Requires no antibody; reveals open chromatin landscape |

| MNase-seq [21] [22] | Nucleosome positioning and occupancy | Nucleosome footprint | Excellent for mapping nucleosome positions across the genome |

| ChIA-PET [27] | Chromatin interactions mediated by specific factors | Chromatin interaction maps | Complex protocol but provides direct evidence of looping |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Histone Modification Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3 (CST #9751S) [28]; Anti-H3K27me3 (CST #9733S) [28] | Specific immunoprecipitation of target histone modifications for ChIP-seq; critical for data quality |

| Chromatin Preparation Reagents | Formaldehyde, glycine, protease inhibitors [28] | Crosslinking of proteins to DNA and preservation of chromatin integrity during processing |

| Chromatin Fragmentation Systems | Bioruptor UCD-200 (Diagenode) or equivalent sonicator [28] | Shearing chromatin to appropriate fragment sizes (200-600 bp) for immunoprecipitation |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina sequencing library preparation kits [28] | Preparation of sequencing libraries from immunoprecipitated DNA |

| Cell Line Models | Mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) [25] [26] | Models for studying histone modification dynamics during differentiation and development |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | CRISPR-based editing tools [25] [27] | Targeted manipulation of histone modification writer/eraser/reader components |

| Ivabradine, (+/-)- | Ivabradine, (+/-)-, CAS:148870-59-1, MF:C27H36N2O5, MW:468.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Omapatrilat metabolite M1-a | Omapatrilat metabolite M1-a, CAS:508181-77-9, MF:C10H16N2O3S, MW:244.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Concepts and Future Directions

Recent research has challenged simplistic interpretations of histone modifications. A 2025 study demonstrated that despite accurate genome-wide re-establishment of H3K36me3 at PRC2 target genes in H3K27me3 null mouse embryonic stem cells, the remaining H3K4me3 prevented H3K36me3 from recruiting sufficient DNA methylation to substitute for H3K27me3-mediated repression [25]. This highlights the unique repressive functions of H3K27me3 and suggests that the functional effects of individual PTMs are highly dependent on interplay with the existing chromatin environment [25].

The concept of H3K27me3-rich regions (MRRs) functioning as silencers represents another significant advancement. These MRRs, identified through clustering of H3K27me3 peaks in a manner analogous to super-enhancer identification, show dense chromatin interactions and can repress gene expression via looping mechanisms [27]. When perturbed by CRISPR excision, these MRRs cause upregulation of interacting genes, altered histone modifications at interacting regions, and changes in cell identity and phenotype [27].

The relationship between H3K4me3 breadth and transcriptional consistency rather than expression levels provides a new framework for understanding how chromatin states influence transcriptional output [26]. This finding suggests that H3K4me3 breadth contains information that ensures transcriptional precision at key cell identity genes, representing a novel chromatin signature linked to cell identity [26].

Future research directions will likely focus on understanding the combinatorial relationships between different histone modifications, developing more precise tools for manipulating specific epigenetic marks, and translating this knowledge into novel therapeutic approaches for cancer and other diseases linked to epigenetic dysregulation. Conferences such as the 2025 Gordon Research Conference on Histone and DNA Modifications will continue to showcase cutting-edge research in this rapidly evolving field [29].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has revolutionized our ability to study protein-DNA interactions on a genomic scale, becoming the cornerstone of modern epigenetics research, particularly for mapping histone modifications [30]. The fundamental goal of ChIP-seq is to identify regions of the genome that are enriched in aligned reads, representing the likely locations where proteins such as transcription factors or histone modifications bind to the DNA [31]. For researchers investigating histone modifications, these enriched regions—called "peaks"—serve as critical indicators of chromatin states that regulate gene expression patterns in health and disease [7]. The process of moving from raw sequencing data to biological interpretation of these peaks presents multiple computational and statistical challenges that must be carefully addressed to draw meaningful conclusions [30].

Understanding the biological meaning of peak calls is especially crucial in histone modification studies because these marks often exhibit distinct genomic distribution patterns compared to transcription factors. While transcription factors typically bind in a punctate manner, histone modifications can form both narrow peaks and broader domains across chromatin [12]. For instance, marks like H3K4me3 typically form sharp peaks at promoter regions, while H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 often form broad domains representing repressive chromatin states [12]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for going beyond simple peak identification to extracting biological meaning from ChIP-seq data, with particular emphasis on histone modification research in drug development contexts.

Experimental Design and Sequencing Considerations for Histone Marks

Proper experimental design forms the foundation for meaningful peak calling and interpretation. The ENCODE consortium has established rigorous standards for ChIP-seq experiments, particularly for histone marks, which require special consideration compared to transcription factor studies [12]. Key experimental parameters must be optimized to ensure data quality and biological relevance.

Sequencing Depth Requirements

Different histone modifications present distinct genomic distribution patterns that directly influence sequencing requirements. The ENCODE consortium provides specific guidelines for sequencing depth based on the characteristics of each histone mark [12].

Table 1: ENCODE Sequencing Standards for Histone Modifications

| Histone Mark Type | Examples | Required Usable Fragments per Replicate | Biological Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow Marks | H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K9ac | 20 million | Sharp, punctate signals often at promoters and enhancers |

| Broad Marks | H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K4me1 | 45 million | Extended domains across chromatin |

| Exception Marks | H3K9me3 | 45 million (with special considerations for repetitive regions) | Enriched in repetitive genomic regions |

These requirements are more stringent than earlier ENCODE2 standards, which required only 10 million fragments for narrow marks and 20 million for broad marks, reflecting increased understanding of data quality needs [12]. Control samples should be sequenced significantly deeper than the ChIP samples, especially for broad-domain histone marks, to ensure sufficient coverage of the genome and non-repetitive autosomal DNA regions [30].

Replicate and Control Requirements

Biological replication is essential for robust peak calling. The ENCODE standards mandate at least two biological replicates for ChIP-seq experiments, which can be either isogenic or anisogenic [12]. Each ChIP-seq experiment must include a corresponding input control experiment with matching run type, read length, and replicate structure to account for technical artifacts and background noise [12]. Antibody quality represents another critical factor, and the ENCODE consortium requires thorough characterization and validation of all antibodies used according to their established standards [12].

Quality Control: Foundation for Reliable Peak Calling

Comprehensive quality assessment is a prerequisite for meaningful biological interpretation of peak calls. Multiple quality metrics should be evaluated throughout the processing pipeline to identify potential issues that could compromise downstream analyses.

Pre-alignment and Alignment Quality Metrics

Initial quality control assesses the raw sequencing data before any processing begins. Tools like FastQC provide an overview of data quality, including base quality scores, GC content, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences [30] [7]. Phred quality scores, which are logarithmically linked to error probabilities, should be used to filter low-quality reads, with subsequent trimming of read ends if necessary [30].

After quality filtering, reads are aligned to a reference genome using tools such as Bowtie2, BWA, or SOAP [30] [32]. The percentage of uniquely mapped reads serves as a critical quality indicator, with values above 70% considered normal for human, mouse, or Arabidopsis ChIP-seq data, while percentages below 50% may indicate problems [30]. For histone marks like H3K9me3 that frequently bind repetitive regions, a higher percentage of multi-mapping reads may be unavoidable [12].

Post-alignment Quality Assessment

After alignment, several specialized metrics evaluate the success of the immunoprecipitation and library preparation.

Table 2: Key Post-Alignment Quality Metrics for Histone ChIP-seq

| Quality Metric | Calculation Method | Recommended Values | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Complexity (NRF) | Non-Redundant Fraction of mapped reads | NRF > 0.9 [12] | Measures amplification bias; low values indicate over-amplification |

| PCR Bottlenecking (PBC) | PBC1 = unique locations/unique reads; PBC2 = unique locations/ >1 read locations | PBC1 > 0.9; PBC2 > 10 [12] | Assesses library complexity and PCR duplicates |

| Strand Cross-correlation | Normalized Strand Cross-correlation Coefficient (NSC) and Relative Strand Cross-correlation (RSC) | NSC > 1.05; RSC > 0.8 [30] | Measures signal-to-noise ratio and fragment size selection quality |

| FRiP Score | Fraction of Reads in Peaks | Varies by mark; higher is better | Indicates enrichment efficiency and antibody specificity |

Library complexity measurements, including the Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) and PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients (PBC1 and PBC2), reflect the diversity of the sequenced library, with preferred values of NRF > 0.9, PBC1 > 0.9, and PBC2 > 10 [12]. Strand cross-correlation analysis assesses the clustering of immunoprecipitated fragments by computing the correlation between forward and reverse strand tag densities, with successful experiments typically showing NSC > 1.05 and RSC > 0.8 [30]. The FRiP score (Fraction of Reads in Peaks) indicates enrichment efficiency by measuring the proportion of reads falling within called peak regions [12].

Peak Calling Strategies for Histone Modifications

Peak calling represents the pivotal step in ChIP-seq analysis where enriched regions are statistically identified from the aligned read data. This process requires different computational approaches for histone modifications compared to transcription factors due to their distinct binding characteristics.

Peak Calling Algorithms and Parameters

The ENCODE consortium has developed specialized pipelines for histone ChIP-seq data that can resolve both punctate binding and broader chromatin domains [12]. Unlike transcription factors that typically show sharp, narrow peaks, histone modifications can exhibit either narrow peaks (e.g., H3K4me3) or broad domains (e.g., H3K27me3), requiring algorithms capable of detecting both patterns [12]. MACS2 is widely used for peak calling and employs a three-step process: fragment size estimation, identification of local noise parameters, and peak identification [7]. The software calculates a p-value and q-value for each potential peak region, with the latter representing the false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted p-value [7].

For histone marks, the ENCODE pipeline generates two types of peak calls: relaxed peak calls for individual replicates and a more stringent set of replicated peaks observed in both biological replicates [12]. When true biological replicates are unavailable, the pipeline employs pseudoreplicates—random partitions of the pooled reads—to identify stable peaks that overlap across partitions [12]. This approach helps maintain reliability even when sample material is limited.

Challenges with Weak ChIP-seq Signals

Co-regulator proteins and some histone modifications can present particularly weak ChIP-seq signals due to their indirect DNA binding properties [33]. Conventional peak calling algorithms with default thresholds may be too stringent for these targets, potentially missing biologically meaningful interactions [33]. Supervised learning approaches, such as naïve Bayes classification, have demonstrated significant improvement in peak calling for weak ChIP-seq signals by integrating multiple sources of biological information [33]. These integrative methods can include complementary data such as ChIP-seq for interacting transcription factors, genomic sequence characteristics, and transcriptomic data reflecting functional outcomes [33].

Biological Interpretation of Called Peaks

The transformation of called peaks into biological insight requires multiple analytical steps that connect genomic locations to gene function and regulatory potential.

Peak Annotation and Genomic Context

Peak annotation associates each enriched region with genomic features to provide biological context. The ChIPseeker R package implements annotation workflows that assign peaks to their nearest genes, either upstream or downstream [31]. However, because binding sites might be located between two start sites of different genes, it is important to specify a maximum distance from the transcription start site (TSS) [31]. A common approach is to use a TSS region of -1000 to +1000 bp when annotating peaks [31].

Genomic annotation follows a priority hierarchy: Promoter > 5' UTR > 3' UTR > Exon > Intron > Downstream > Intergenic [31]. This hierarchical approach ensures that peaks overlapping multiple features are assigned the most potentially significant annotation. The distribution of peaks across these genomic features provides initial insights into their potential functional roles. For example, peaks annotated as promoters likely represent direct regulatory elements, while those in intergenic regions may represent distal enhancers or other regulatory elements.

Functional Enrichment Analysis

Once peaks are annotated with associated genes, functional enrichment analysis identifies predominant biological themes using knowledge bases such as Gene Ontology (GO), KEGG, and Reactome [31]. Over-representation analysis determines whether certain biological processes, molecular functions, or cellular components are statistically over-represented in the gene set associated with ChIP-seq peaks [31]. Tools like clusterProfiler can perform these analyses, helping researchers connect the genomic binding data to higher-order biological functions and pathways [31].

For histone modification studies, functional enrichment can reveal how particular chromatin states influence cellular processes. For instance, H3K27me3 enrichment at genes involved in developmental processes might suggest silencing of alternative lineage programs, while H3K4me3 enrichment at metabolic genes could indicate active regulation of energy pathways. These analyses are particularly valuable in disease contexts, where aberrant histone modifications might contribute to pathological gene expression programs.

Motif Analysis and Sequence Characterization

The identification of transcription factor binding motifs within ChIP-seq peaks can reveal cooperating or competing regulatory factors that interact with histone modifications [7]. Motif analysis examines the DNA sequence underlying peak regions to identify statistically over-represented sequence patterns compared to background genomic regions [31]. This analysis can suggest which transcription factors might be working in concert with or independently of the histone marks under investigation, providing insights into broader regulatory networks.

Visualization and Data Integration

Effective visualization enables researchers to qualitatively assess ChIP-seq results and integrate multiple data types for comprehensive biological interpretation.

Genome Browser Visualization

The Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) provides a dynamic platform for visualizing ChIP-seq data in genomic context [7]. BigWig files, which contain normalized signal coverage tracks, are ideal for genome browser visualization as they display enrichment patterns as continuous graphs [32]. These files can be generated using tools like bamCoverage from the deepTools suite, with normalization methods such as BPM (Bins Per Million) providing comparable signals across samples [32]. Visual inspection in a genome browser allows researchers to confirm called peaks, assess signal quality, and examine spatial relationships with other genomic features.

Profile Plots and Heatmaps

deepTools provides powerful utilities for creating meta-profiles and heatmaps that summarize ChIP-seq enrichment patterns across multiple genomic regions [32]. The computeMatrix function calculates scores across specified genomic windows, such as ±1000 bp around transcription start sites, which can then be visualized with plotProfile and plotHeatmap [32]. These aggregate visualizations reveal overall binding patterns, such as the preferential enrichment of certain histone marks at promoters, enhancers, or other genomic elements.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ChIP-seq Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Validated histone modification antibodies (e.g., anti-H3K27ac, anti-H3K4me3) | Target-specific immunoprecipitation; must be characterized according to ENCODE standards [12] |

| Sequencing Kits | Illumina sequencing platforms | High-throughput DNA sequencing; read length should be ≥50bp with longer reads encouraged [12] |

| Alignment Tools | Bowtie2, BWA, SOAP | Map sequenced reads to reference genome; support gapped alignment for improved mapping [30] [32] |

| Peak Callers | MACS2, SPP, BayesPeak | Identify statistically enriched regions; algorithm choice depends on mark characteristics [30] [33] |

| Annotation Tools | ChIPseeker, HOMER | Annotate peaks with genomic features and nearest genes; provide functional context [31] |

| Visualization Tools | deepTools, IGV, UCSC Genome Browser | Generate bigWig files, profile plots, heatmaps, and genome browser tracks [32] [7] |

| Functional Analysis | clusterProfiler, DAVID | Perform GO term and pathway enrichment analysis of peak-associated genes [31] |

| Quality Control Tools | FastQC, preseq, CHANCE | Assess read quality, library complexity, and IP strength [30] |

Advanced Integrative Analysis Methods

As ChIP-seq technology evolves, advanced integrative approaches are emerging that combine multiple data types to enhance biological interpretation, particularly for challenging targets like co-regulators and weak histone marks.

Machine Learning Approaches for Peak Calling

Supervised learning methods can significantly enhance peak calling sensitivity for weak ChIP-seq signals. The naïve Bayes algorithm has demonstrated particular effectiveness in integrating multiple biological data sources to improve the identification of functional binding sites [33]. These approaches can incorporate complementary information such as transcription factor binding data, sequence specificity, chromatin accessibility, and gene expression changes to distinguish true binding events from background noise [33].

Integrative methods are especially valuable for studying co-regulator proteins like SRC-1, which exhibit relatively weak ChIP-seq signals due to their indirect DNA binding through primary transcription factors [33]. By combining ChIP-seq data from the co-regulator and its interacting transcription factors with transcriptomic data reflecting functional outcomes, researchers can identify biologically meaningful binding events that would be missed by conventional peak calling algorithms [33].

Emerging Technologies: CUT&Tag

CUT&Tag represents an emerging alternative to ChIP-seq that offers advantages in sensitivity and requires fewer cells, making it particularly suitable for rare cell populations and single-cell applications [34]. While CUT&Tag recovers approximately half of the peaks identified by ChIP-seq in comparative studies, it captures the most significant and strongest signals while showing similar enrichments in regulatory elements and functional annotations [34]. This technology shows particular promise for histone modification studies, where it demonstrates comparable performance to ChIP-seq in capturing key epigenetic signatures [34].

The journey from raw sequencing data to biological understanding of histone modifications requires careful attention at each analytical step, from experimental design through functional interpretation. By adhering to established quality standards, selecting appropriate analytical parameters based on the specific histone mark being studied, and integrating multiple lines of biological evidence, researchers can transform peak calls into meaningful insights about gene regulatory mechanisms. The frameworks and methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide a roadmap for extracting biological meaning from ChIP-seq data, with particular relevance for drug development professionals seeking to understand how histone modifications influence disease processes and therapeutic responses. As technologies continue to evolve and integrative approaches become more sophisticated, our ability to interpret the biological significance of chromatin states will continue to deepen, opening new avenues for epigenetic research and therapeutic development.

The functional annotation of eukaryotic genomes extends far beyond the coding sequences of genes, encompassing a complex landscape of regulatory elements that control gene expression in a cell-type-specific manner. Central to this regulatory system are histone post-translational modifications (PTMs), which act as fundamental components of the epigenetic code that annotates functional genomic elements. These chemical modifications—including methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation—on histone proteins serve as critical markers that delineate genomic regions with distinct functions, from promoters and enhancers to repressed domains. The development of chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has revolutionized our ability to map these histone marks genome-wide, creating an powerful framework for connecting epigenetic signatures to genomic function [35] [3]. Within the context of a broader thesis on understanding ChIP-seq peaks for histone modifications research, this technical guide examines how specific histone marks serve as definitive biomarkers for annotating functional elements, the methodologies for their accurate detection, and the integration of these data to build comprehensive models of genomic regulation.

The biological significance of histone modifications lies in their ability to directly influence chromatin structure and function through two primary mechanisms: by altering the electrostatic charge between histones and DNA, thereby changing chromatin accessibility, and by serving as docking sites for reader proteins that initiate downstream regulatory events [3]. For instance, acetylation of lysine residues neutralizes positive charges on histones, reducing their interaction with negatively charged DNA and promoting an open chromatin configuration that facilitates transcription factor binding and gene activation [3]. In contrast, certain methylation patterns establish binding platforms for proteins that promote chromatin condensation and gene silencing [36] [37]. This complex interplay of modifications forms a sophisticated regulatory language that researchers can decipher to understand the functional organization of genomes in different biological contexts, from normal development to disease states.

Core Histone Modifications and Their Genomic Annotations

Specific histone modifications exhibit strong associations with distinct functional genomic elements, serving as reliable biomarkers for genome annotation. The table below summarizes the primary histone marks used for annotating key regulatory regions, their genomic locations, and functional consequences.

Table 1: Core Histone Modifications and Their Associated Genomic Annotations

| Histone Modification | Genomic Annotation | Primary Genomic Location | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 [3] | Active Promoters [38] [39] | Transcription Start Sites (TSS) | Transcriptional activation |

| H3K4me1 [39] [3] | Enhancers | Distal regulatory elements | Defines enhancer regions |

| H3K27ac [39] [3] | Active Enhancers/Promoters | Enhancers and Promoters | Distinguishes active from poised enhancers |

| H3K27me3 [38] [39] [3] | Repressed/Polycomb Targets | Promoters in gene-rich regions | Transcriptional repression |

| H3K9me3 [3] | Constitutive Heterochromatin | Telomeres, pericentromeres, repeat elements | Permanent gene silencing |

| H3K36me3 [3] | Transcriptional Elongation | Gene bodies | Transcriptional elongation |

The combinatorial presence of certain marks provides further functional insight. For example, bivalent promoters in embryonic stem cells, which regulate developmental genes, are marked by the simultaneous presence of both the activating H3K4me3 and repressing H3K27me3 modifications [38]. These bivalent domains are considered "poised" for activation, allowing for rapid transcriptional response upon differentiation signals. The distinct spatial organization of these marks has been further elucidated by high-resolution methods like Micro-C-ChIP, which has resolved the unique 3D architecture of bivalent promoters in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) [38]. Furthermore, the functional annotation of these marks extends to their spatial nuclear organization, with repressive marks like H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 being strongly associated with lamina-associated domains (LADs) at the nuclear periphery, which correspond to transcriptionally inactive B compartments [37].

Experimental Methodologies for Mapping Histone Marks

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

The primary method for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications is ChIP-seq, a technique that combines chromatin immunoprecipitation with high-throughput sequencing. The standard protocol involves several critical steps: First, cells are cross-linked with formaldehyde to preserve protein-DNA interactions. The chromatin is then fragmented, typically by sonication or enzymatic digestion, to sizes of 200-600 bp [40] [39]. Immunoprecipitation is performed using highly specific antibodies against the histone modification of interest. After reversing cross-links and purifying the DNA, the resulting libraries are sequenced and mapped to the reference genome [12] [3].

Key considerations for robust ChIP-seq experiments include the use of biological replicates to ensure reproducibility, with the ENCODE consortium recommending at least two replicates per experiment [12]. The required sequencing depth varies by the type of histone mark: narrow marks like H3K4me3 require approximately 20 million usable fragments per replicate, while broad marks like H3K27me3 require 45 million fragments [12]. Essential quality control metrics include the FRiP (Fraction of Reads in Peaks) score, which measures enrichment, and library complexity metrics (NRF > 0.9, PBC1 > 0.9, PBC2 > 3) to assess potential amplification biases [12]. A critical methodological consideration is that local differences in nucleosome density can create systematic biases in ChIP-seq data, as regions with higher nucleosome density may yield stronger signals independent of the actual modification status [40]. This underscores the importance of appropriate controls and normalization strategies.

Advanced Methodologies: Integrating 3D Genome Architecture

Recent methodological advances have enabled the simultaneous mapping of histone modifications and chromatin architecture, providing a more integrated view of genome organization. Micro-C-ChIP is a high-resolution approach that combines Micro-C (an MNase-based version of Hi-C) with chromatin immunoprecipitation to map 3D genome organization at nucleosome resolution for defined histone modifications [38]. This technique involves dual crosslinking of cells, MNase digestion to fragment chromatin, biotinylation of DNA ends, proximity ligation, and immunoprecipitation with histone modification-specific antibodies [38].

This methodology offers several advantages: it maintains a high fraction of informative reads (42% compared to 37% in genome-wide Micro-C) while providing histone mark-specific enrichment, and it reveals genuine 3D genome features not driven by ChIP-enrichment bias [38]. Applications of Micro-C-ChIP have identified extensive promoter-promoter contact networks and resolved the distinct 3D architecture of bivalent promoters in mESCs [38]. Other related methods include HiChIP and PLAC-seq, which also combine proximity ligation with immunoprecipitation but differ in their fragmentation and library preparation strategies [38].

Figure 1: Micro-C-ChIP Workflow for Histone-Mark Specific 3D Genome Mapping

Data Analysis and Interpretation Frameworks

Peak Calling and Normalization Strategies

The analysis of histone modification ChIP-seq data requires specialized approaches tailored to the characteristics of different marks. The ENCODE consortium has developed distinct pipelines for narrow and broad histone marks [12]. For narrow marks like H3K4me3, peak callers such as MACS2 are typically used, while for broad marks like H3K27me3, both MACS2 and specialized tools like SICER2 are employed [39]. The choice of normalization method is critical, particularly for enrichment-based technologies. Standard normalization methods like ICE, which assume equal coverage across genomic regions, are unsuitable for ChIP-based methods where coverage varies inherently [38]. Instead, input-based normalization approaches, similar to those used in 1D ChIP-seq experiments, can account for biases inherent to chromatin accessibility, sequencing, and experimental artifacts [38].

Validation of identified interactions is essential. Comparison of Micro-C-ChIP data with deeply sequenced bulk Micro-C datasets has shown that despite much lower sequencing depth, Micro-C-ChIP detects structural features of bulk Micro-C with high definition [38]. Furthermore, at sites with strong histone modification signals (e.g., precise H3K4me3 ChIP-seq peaks at promoter regions), bulk and ChIP-enriched interaction profiles show comparable patterns, supporting that the method detects genuine 3D contacts rather than methodological artifacts [38].

Annotation of cis-Regulatory Elements