Decoding the Epigenome: A Comprehensive Guide to Methylation Coverage Signals Across Genomic Regions

This article provides a cutting-edge overview for researchers and drug development professionals on generating and interpreting average methylation coverage signal profiles across genomic regions.

Decoding the Epigenome: A Comprehensive Guide to Methylation Coverage Signals Across Genomic Regions

Abstract

This article provides a cutting-edge overview for researchers and drug development professionals on generating and interpreting average methylation coverage signal profiles across genomic regions. It explores the foundational biology of DNA methylation as a key epigenetic regulator of cellular identity and disease, with a focus on its distinct patterns in CpG islands, shores, shelves, and open seas. The content delves into the strengths and limitations of current profiling technologies—from bisulfite sequencing and microarrays to enzymatic and long-read nanopore methods—and their integration with machine learning for biomarker discovery. Practical guidance is offered for troubleshooting data quality, batch effects, and analytical challenges. Finally, the article presents a comparative framework for validating methylation profiles and discusses their transformative clinical applications in precision oncology, liquid biopsies, and therapeutic development, synthesizing the latest research and market trends to guide future epigenetic studies.

The Biological Blueprint: Understanding DNA Methylation Patterns and Their Genomic Landscape

DNA methylation is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism involving the addition of a methyl group to the cytosine ring within CpG dinucleotides, primarily occurring in the context of CpG islands [1]. This process is mediated by enzymes known as DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), which use S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) as a methyl donor to catalyze the methylation process [1]. DNA methylation regulates gene expression and chromatin organization without altering the underlying DNA sequence, thus providing a window into cellular identity and developmental processes [2]. This stable yet reversible modification plays crucial roles in embryonic development, genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, and maintaining chromosome stability [1] [3].

The dynamic nature of DNA methylation is maintained through a balance between methylation addition by "writer" enzymes (DNMTs) and removal by "eraser" enzymes, such as the ten-eleven translocation (TET) family [1]. These enzymes demethylate DNA by oxidizing 5-methylcytosine (5mC) into 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), and further into 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) [1]. Understanding these basic principles is essential for appreciating how DNA methylation contributes to cellular identity and disease pathogenesis.

Core Mechanisms of DNA Methylation

The Biochemical Process and Key Enzymes

The establishment and maintenance of DNA methylation patterns involve a coordinated enzymatic system:

- De Novo Methylation: DNMT3a and DNMT3b establish new methylation patterns during embryonic development [1].

- Maintenance Methylation: DNMT1 preserves methylation patterns after DNA replication by recognizing hemi-methylated DNA strands and restoring the methylation pattern on the new strand [1].

- Active Demethylation: The TET enzyme family (TET1, TET2, TET3) catalyzes the oxidation of 5mC to 5hmC, then to 5fC and 5caC, which are subsequently replaced by unmethylated cytosine through base excision repair [1] [3].

Table 1: Key Enzymes in DNA Methylation Dynamics

| Enzyme | Type | Primary Function | Resulting Modification |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Writer | Maintenance methylation | Preserves existing patterns during cell division |

| DNMT3a, DNMT3b | Writer | De novo methylation | Establishes new methylation patterns |

| TET Family (1,2,3) | Eraser | Active demethylation | Oxidizes 5mC to 5hmC, 5fC, 5caC |

| Thymine DNA Glycosylase (TDG) | Eraser | Base excision repair | Replaces oxidized cytosines with unmethylated cytosine |

Regulatory Targeting Mechanisms

The targeting of DNA methylation to specific genomic locations involves both epigenetic and genetic mechanisms. While self-reinforcing connections with other chromatin modifications maintain stable patterns, recent research has revealed that genetic sequences can also direct new DNA methylation patterns [4] [5].

In plants, a paradigm-shifting discovery identified that REPRODUCTIVE MERISTEM (REM) transcription factors, designated REM INSTRUCTS METHYLATION (RIMs), act with CLASSY3 to establish DNA methylation at specific genomic targets by docking at indispensable DNA sequences [4] [5]. When these DNA stretches are disrupted, the entire methylation pathway fails, demonstrating that genetic information can directly guide epigenetic processes [4].

In mammalian systems, a specialized variant of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1.6) acts as an epigenetic hub that maintains transient silencing of germline genes and eventually stimulates recruitment of de novo DNA methyltransferases [6]. This coordinated epigenetic relay connects Polycomb repression, histone modifications, and DNA methylation pathways to maintain the critical barrier between germline and soma [6].

Functional Roles in Gene Regulation

Transcriptional Regulation Mechanisms

DNA methylation influences gene expression through several interconnected mechanisms:

- Promoter Silencing: Methylation of CpG islands in promoter regions typically leads to gene silencing by preventing transcription factor binding and recruiting proteins that promote chromatin condensation [1] [7].

- Enhancer Regulation: Unmethylated enhancer regions are crucial for cell-type-specific gene expression, with hypomethylation marking active enhancers [2] [8].

- Chromatin Organization: Hypermethylated loci are enriched for CpG islands, Polycomb targets, and CTCF binding sites, suggesting a role in shaping cell-type-specific chromatin looping and three-dimensional genome architecture [2].

The effect of DNA methylation varies by genomic context. While promoter methylation generally suppresses gene expression, gene body methylation exhibits more complex regulatory mechanisms that can influence splicing processes and maintain genomic stability [7].

Cellular Identity and Developmental Programming

DNA methylation patterns are exceptionally robust markers of cellular identity. The 2023 human methylome atlas demonstrated that replicates of the same cell type are more than 99.5% identical, highlighting the robustness of cell identity programs to environmental perturbation [2]. Unsupervised clustering of methylation patterns systematically groups biological samples of the same cell type and recapitulates key elements of tissue ontogeny, identifying methylation patterns retained since embryonic development [2].

Table 2: DNA Methylation Patterns in Cellular Identity and Disease

| Context | Methylation Status | Functional Consequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Cellular Identity | Cell-type specific patterns | Maintenance of differentiation state | [2] |

| Promoter Regions | Hypermethylation | Gene silencing | [1] [7] |

| Enhancer Regions | Hypomethylation | Cell-type-specific gene activation | [2] [8] |

| Cancer Cells | Global hypomethylation with localized hypermethylation | Genomic instability & tumor suppressor silencing | [9] |

| Germline Genes in Soma | PRC1.6-directed hypermethylation | Prevention of ectopic germline gene expression | [6] |

Loci uniquely unmethylated in an individual cell type often reside in transcriptional enhancers and contain DNA binding sites for tissue-specific transcriptional regulators, while uniquely hypermethylated loci are rare and enriched for specific genomic features [2]. This precise patterning creates what has been termed each individual's unique "epigenoprint" that defines cellular identity and function [3].

Experimental Methodologies for DNA Methylation Analysis

Genome-Wide Profiling Technologies

Multiple methods exist for comprehensive DNA methylation analysis, each with distinct strengths and limitations:

- Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS): Considered the gold standard, WGBS provides single-base resolution of methylation patterns across approximately 80% of all CpG sites in the genome. Limitations include DNA degradation during bisulfite treatment and high computational requirements [2] [7].

- Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq): This conversion-free method uses TET2 enzyme for oxidation and APOBEC for deamination to profile methylation without DNA fragmentation. EM-seq shows high concordance with WGBS and can handle lower DNA input amounts [7].

- Microarray Platforms (EPIC): Illumina's Infinium MethylationEPIC array interrogates over 935,000 methylation sites, offering a cost-effective solution for large cohort studies, though limited to predefined CpG sites [7].

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT): Third-generation sequencing enables direct detection of DNA methylation without chemical conversion or enzymatic treatment, benefiting from long-read sequencing to resolve challenging genomic regions [7].

Emerging and Targeted Approaches

Recent technological advances have expanded the methodological toolkit:

- Active-Seq: A base-conversion-free technology that enables isolation of DNA containing unmodified CpG sites using a mutated bacterial methyltransferase enzyme and synthetically prepared cofactor analog. This approach uniquely targets and enriches unmethylated enhancers that define cell type identity [8].

- Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP): An enrichment-based technique that isolates methylated DNA fragments using antibodies specific to 5-methylcytosine, followed by sequencing to identify methylation patterns across the genome [1].

- Single-Cell Bisulfite Sequencing (scBS-Seq): Enables methylation profiling at cellular resolution, revealing methylation heterogeneity and offering insights into cellular dynamics [1].

Table 3: Comparison of DNA Methylation Detection Methods

| Method | Resolution | Coverage | DNA Input | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGBS | Single-base | ~80% of CpGs | High (~1μg) | Gold standard, comprehensive | DNA degradation, high cost |

| EM-seq | Single-base | Similar to WGBS | Low (1 ng) | Preserves DNA integrity, uniform coverage | Enzymatic complexity |

| EPIC Array | Single CpG | 935,000 sites | Moderate (500 ng) | Cost-effective, standardized | Limited to predefined sites |

| ONT Sequencing | Single-base | Varies with depth | High (~1μg) | Long reads, no conversion | Lower agreement with WGBS |

| RRBS | Single-base | ~5% of CpGs | Moderate | Cost-effective for CpG-rich regions | Limited genome coverage |

| Active-Seq | Regional | Enrichment-based | Low (1 ng) | Targets unmethylated regions | Not base-resolution |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Methylation Studies

| Reagent/Technology | Category | Primary Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip | Microarray | Genome-wide methylation profiling at predefined CpG sites | Large cohort studies, biomarker discovery [7] |

| EZ DNA Methylation Kit | Chemical Conversion | Bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines | WGBS, RRBS library preparation [7] |

| EM-seq Kit | Enzymatic Conversion | Oxidation and deamination for methylation detection | Fragmentation-sensitive applications, low-input DNA [7] |

| Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) Kit | Enrichment | Antibody-based isolation of methylated DNA | Methylome studies without bisulfite conversion [1] |

| TET Enzymes | Enzymatic Tools | Oxidation of 5mC to 5hmC, 5fC, 5caC | Demethylation studies, enzymatic conversion methods [1] |

| DNMT Inhibitors | Small Molecules | Inhibition of DNA methyltransferases | Epigenetic therapy, mechanistic studies [3] |

| Anti-5mC Antibodies | Immunodetection | Recognition and binding of methylated cytosine | MeDIP, immunostaining, methylation quantification [1] |

| Nanopore Sequencing Kits | Third-gen Sequencing | Direct detection of modified bases | Long-read methylation haplotyping, real-time analysis [7] |

Applications in Genomic Medicine and Research

Diagnostic and Clinical Applications

DNA methylation biomarkers have transformed approaches to disease detection and monitoring:

- Liquid Biopsies: DNA methylation patterns enable minimally invasive cancer detection from circulating cell-free DNA. Methylation-based classifiers have standardized diagnoses across over 100 central nervous system cancer subtypes and altered histopathologic diagnosis in approximately 12% of prospective cases [1] [9].

- Rare Disease Diagnosis: Genome-wide episignature analysis utilizes machine learning to correlate a patient's blood methylation profile with disease-specific signatures, demonstrating clinical utility in genetics workflows [1].

- Multi-Cancer Early Detection: Targeted methylation assays combined with machine learning provide early detection of many cancers from plasma cell-free DNA, showing excellent specificity and accurate tissue-of-origin prediction [1].

The inherent stability of DNA methylation patterns, their emergence early in tumorigenesis, and the stability throughout tumor evolution make them ideal biomarkers for clinical applications [9].

Integration with Machine Learning and AI

Advanced computational methods are increasingly applied to methylation data:

- Traditional Machine Learning: Support vector machines, random forests, and gradient boosting have been employed for classification, prognosis, and feature selection across tens to hundreds of thousands of CpG sites [1].

- Deep Learning: Multilayer perceptrons and convolutional neural networks have been used for tumor subtyping, tissue-of-origin classification, and survival risk evaluation [1].

- Foundation Models: Transformer-based models like MethylGPT and CpGPT, trained on more than 150,000 human methylomes, support imputation and prediction with physiologically interpretable focus on regulatory regions [1].

These computational approaches enhance the precision and comprehensive nature of methylation-based diagnostics while reducing costs and improving patient outcomes [1].

DNA methylation serves as a fundamental epigenetic mechanism governing gene expression and cellular identity through complex but decipherable patterns. The core principles of this modification—its precise enzymatic regulation, functional consequences for gene expression, and stability as a cellular memory mechanism—underscore its critical importance in development, cellular differentiation, and disease. Advances in detection technologies, from bisulfite sequencing to emerging enzymatic and third-generation sequencing methods, have progressively enhanced our ability to profile methylation patterns at single-base resolution across the genome.

The integration of methylation profiling with machine learning approaches represents the frontier of this field, enabling more precise diagnostic applications and deeper insights into the regulatory logic embedded in the epigenome. As methods continue to evolve toward less invasive applications like liquid biopsies and single-cell analyses, DNA methylation profiling stands positioned to deliver increasingly transformative contributions to personalized medicine and our fundamental understanding of cellular identity and function.

DNA methylation, a fundamental epigenetic mechanism involving the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases primarily at CpG dinucleotides, serves as a critical regulator of gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [1]. The human genome is organized into distinct regions based on their CpG density and genomic characteristics, creating a diverse "geography" that includes CpG islands, shores, shelves, and open seas. Each of these regions demonstrates unique methylation patterns and functional significance in gene regulation, cellular differentiation, and disease pathogenesis [10]. CpG islands are regions of high CpG density typically located near gene promoters, while shores extend 0-2 kb from islands, shelves extend 2-4 kb from islands, and open seas encompass the remaining genomic regions with low CpG density [7].

The precise mapping of methylation across these genomic domains provides crucial insights into normal biological processes and disease mechanisms. Research has consistently demonstrated that methylation patterns are highly tissue-specific and dynamically regulated throughout development and aging [11]. In cancer genomes, these patterns become profoundly disrupted, with characteristic hypermethylation of promoter-associated CpG islands concomitant with widespread hypomethylation in intergenic and open sea regions [10]. Understanding this genomic geography of methylation is thus essential for elucidating the epigenetic architecture of both normal cellular function and disease states, particularly for researchers and drug development professionals seeking epigenetic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Methylation Geography: Regional Characteristics and Functional Roles

Defining the Genomic Regions

The genomic landscape of DNA methylation can be divided into distinct regulatory domains based on their proximity to CpG islands and their functional properties:

CpG Islands (CGIs): These are dense clusters of CpG sites spanning 200-4000 base pairs with observed-to-expected CpG ratios >0.6 and GC content >50%. CGIs are predominantly located in gene promoters and typically remain unmethylated in normal cells, permitting gene expression when transcription factors are present. Approximately 70% of human gene promoters are associated with CpG islands [7] [10].

CpG Shores: Flanking CpG islands up to 2 kilobases, these regions show intermediate CpG density. Shores frequently display tissue-specific methylation patterns that strongly correlate with gene expression changes. Interestingly, nearly 70% of tissue-specific differentially methylated regions occur in CpG shores rather than in the islands themselves [10].

CpG Shelves: Extending 2-4 kilobases from islands, these transitional zones exhibit lower CpG density. They often show coordinated methylation changes in cancer and during cellular differentiation, serving as secondary regulatory domains that may influence chromatin organization over broader genomic regions [10].

Open Seas: Representing the majority (>95%) of the genome, these are regions of sparse CpG density located far from any islands. Open seas are generally highly methylated in normal cells but demonstrate pronounced hypomethylation in cancers and aging, potentially contributing to genomic instability through transposon activation and loss of chromatin integrity [7] [10].

Methylation Patterns Across Genomic Regions

Table 1: Characteristic Methylation Patterns Across Genomic Geography

| Genomic Region | CpG Density | Typical Methylation State in Normal Cells | Common Alterations in Cancer | Functional Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CpG Islands | High | Mostly unmethylated | Focal hypermethylation (especially at tumor suppressor genes) | Gene silencing, promoter regulation, X-chromosome inactivation |

| CpG Shores | Intermediate | Variable, tissue-specific | Frequent hypermethylation | Tissue-specific expression, enhancer regulation |

| CpG Shelves | Low | Moderate methylation | Both hyper- and hypomethylation | Chromatin boundary definition, intermediate regulatory domains |

| Open Seas | Very low | Highly methylated | Widespread hypomethylation | Genomic stability, transposon suppression, structural integrity |

The distribution of methylation across these genomic domains is not random but follows specific patterns relevant to biological function and disease. Studies of esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma (ESCC) have revealed that hyper-methylated CpG sites are significantly enriched in CpG islands (OR = 1.66, P = 1.00e-1502) and DNase I hypersensitivity sites, while hypo-methylated sites predominantly occur in open sea regions (OR = 1.89, P = 1.00e-4373) [10]. This differential distribution reflects distinct underlying biological mechanisms: promoter hypermethylation typically leads to transcriptional repression of tumor suppressor genes, while hypomethylation in open seas may activate oncogenes, transposable elements, and promote genomic instability.

The functional impact of methylation also varies significantly by genomic context. In promoter regions, methylation typically suppresses gene expression by inhibiting transcription factor binding and recruiting methyl-binding proteins that promote chromatin condensation [7]. In contrast, gene body methylation is often associated with active transcription and plays roles in alternative splicing regulation and suppression of spurious transcription initiation [7]. Enhancer methylation generally reduces enhancer activity, thereby influencing the expression of target genes potentially located considerable distances away.

Analytical Approaches: Mapping the Methylation Landscape

Methodologies for Methylation Profiling

Several technologies have been developed for genome-wide DNA methylation analysis, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and applications for mapping methylation across genomic regions:

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS): Considered the gold standard, WGBS provides single-base resolution of methylation patterns across approximately 80% of all CpG sites in the genome. This method employs bisulfite conversion, which deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged, allowing for comprehensive mapping of methylation across all genomic regions. However, WGBS requires high sequencing coverage, involves substantial computational resources, and can cause DNA degradation due to harsh bisulfite treatment conditions [7].

Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq): This emerging alternative to WGBS uses enzymatic conversion rather than chemical bisulfite treatment, preserving DNA integrity while maintaining high accuracy. EM-seq employs the TET2 enzyme to oxidize 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) to 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), while APOBEC deaminates unmodified cytosines to uracils. Recent comparative studies show EM-seq has the highest concordance with WGBS, indicating strong reliability, and can handle lower DNA input amounts than traditional WGBS [7].

Illumina Methylation BeadChip Arrays (EPIC and 450K): These popular microarray platforms provide a cost-effective solution for profiling methylation at pre-selected sites. The EPIC array covers over 935,000 CpG sites, extensively covering promoter regions, enhancers, and diverse genomic contexts. While limited to predetermined CpG sites, these arrays offer standardized processing, high throughput, and well-established analytical pipelines, making them suitable for large epidemiological studies [7] [12].

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) Sequencing: This third-generation sequencing approach enables direct detection of DNA methylation without pre-treatment, leveraging changes in electrical signals as DNA passes through protein nanopores. ONT excels in long-read sequencing, allowing for phased methylation analysis and access to challenging genomic regions like repeats and structural variants. However, it requires relatively high DNA input (approximately 1μg of 8 kb fragments) and currently shows lower agreement with WGBS and EM-seq [7].

Table 2: Comparison of DNA Methylation Detection Methods

| Method | Resolution | Genomic Coverage | DNA Input | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGBS | Single-base | ~80% of CpGs | High (≥1μg) | Comprehensive coverage, gold standard | DNA degradation, high cost, complex data analysis |

| EM-seq | Single-base | Comparable to WGBS | Medium (≥100ng) | Preserves DNA integrity, uniform coverage, low input | Newer method, less established protocols |

| EPIC Array | Predetermined sites | ~935,000 CpGs | Low (≥50ng) | Cost-effective, high-throughput, standardized | Limited to predefined sites, no novel discovery |

| ONT Sequencing | Single-base (direct) | Long reads, all CpGs | High (≥1μg) | Long-range phasing, no conversion needed | Higher error rate, requires specialized equipment |

Experimental Workflow for Regional Methylation Analysis

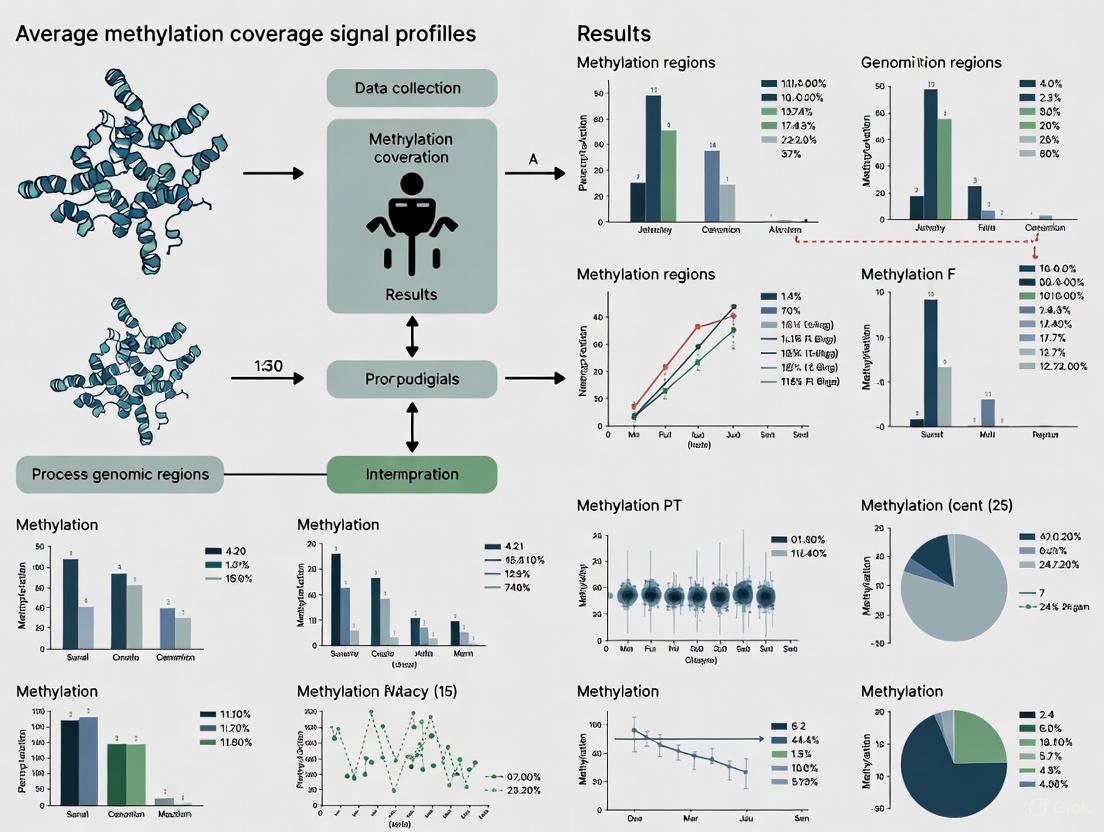

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for methylation analysis across genomic regions using bisulfite or enzymatic conversion methods:

Figure 1: Workflow for Methylation Analysis Across Genomic Regions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Methylation Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) | Bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines | Sample preparation for WGBS and EPIC arrays |

| Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 BeadChip (Illumina) | Genome-wide methylation profiling at 935,000 CpG sites | Large cohort studies, cancer biomarker discovery |

| Nanobind Tissue Big DNA Kit (Circulomics) | High-molecular-weight DNA extraction | Preparation for long-read sequencing (ONT) |

| ChAMP R Package | Data processing, normalization, and differential methylation analysis | Bioinformatic analysis of array-based methylation data |

| TET2 Enzyme/APOBEC Mix | Enzymatic conversion of methylation states | EM-seq library preparation as bisulfite-free alternative |

| Methylation-Specific PCR Primers | Targeted amplification of methylated/unmethylated sequences | Validation of specific differentially methylated regions |

Case Studies: Regional Methylation in Disease Contexts

Methylation Geography in Cancer

Comprehensive analysis of esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma (ESCC) has revealed distinctive patterns of methylation alterations across genomic regions. In a study of 91 ESCC patients, researchers identified 35,577 differentially methylated CpG sites (DMCs) when comparing tumor and adjacent normal tissues [10]. The distribution of these alterations showed significant regional specificity: hyper-methylated sites were overwhelmingly enriched in CpG islands (OR = 1.66, P = 1.00e-1502) and promoter regions, while hypo-methylated sites predominantly occurred in open seas (OR = 1.89, P = 1.00e-4373) and intergenic regions [10]. Chromosomal distribution also varied, with hyper-methylated sites enriched on chromosomes 18 and 19, while hypo-methylated sites clustered on chromosome 8.

Similar patterns emerge in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), where methylation signature analysis using independent component analysis (MethICA) identified 13 stable methylation components with distinct regional preferences [13]. Specific driver mutations correlated with particular methylation geographies: CTNNB1 mutations were associated with hypomethylation of transcription factor 7-bound enhancers near Wnt target genes, while AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A (ARID1A) mutations linked to epigenetic silencing of differentiation-promoting networks in cirrhotic liver [13]. These findings demonstrate how regional methylation patterns reflect the underlying molecular pathogenesis of cancer subtypes.

Environmental Influences on Methylation Geography

A genome-wide study of city policemen exposed to different air pollution levels demonstrated that environmental factors induce region-specific methylation changes [12]. Researchers identified 13,643 differentially methylated CpG loci between policemen working in high-pollution (Ostrava) versus lower-pollution (Prague) environments. These alterations were enriched in genes associated with diabetes mellitus (KCNQ1), respiratory diseases (PTPRN2), and neuronal functions [12]. The most significantly affected pathway was Axon guidance, with 86 potentially deregulated genes located near DMLs. This study illustrates how environmental exposures can reshape the methylation landscape in a region-specific manner, potentially contributing to disease susceptibility.

Aging and Methylation Geography

The MethAgingDB database provides comprehensive resources for studying age-related methylation changes across genomic regions [11]. This database includes 93 datasets with 12,835 DNA methylation profiles from 17 different tissues across human and mouse models, systematically cataloging tissue-specific aging-related differentially methylated sites (DMSs) and regions (DMRs) [11]. Analysis of these datasets reveals that aging-associated methylation changes occur preferentially in specific genomic regions, particularly CpG shores and shelves, with tissue-specific patterns that may contribute to functional decline and age-related disease susceptibility.

Advanced Applications: Machine Learning and Diagnostic Development

Computational Analysis of Methylation Geography

Machine learning approaches have revolutionized the analysis of methylation patterns across genomic regions. Conventional supervised methods, including support vector machines, random forests, and gradient boosting, have been employed for classification, prognosis, and feature selection across tens to hundreds of thousands of CpG sites [1]. More recently, deep learning architectures such as multilayer perceptrons and convolutional neural networks have demonstrated superior capability in capturing nonlinear interactions between CpGs and their genomic context for tumor subtyping, tissue-of-origin classification, and survival risk evaluation [1].

Transformative advances include the development of foundation models pretrained on extensive methylation datasets. MethylGPT, trained on more than 150,000 human methylomes, supports imputation and subsequent prediction with physiologically interpretable focus on regulatory regions, while CpGPT exhibits robust cross-cohort generalization and produces contextually aware CpG embeddings that transfer efficiently to age and disease-related outcomes [1]. These models enhance analytical efficiency, particularly for limited clinical populations, and underscore the promise of task-agnostic, generalizable methylation learners.

Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker Development

The regional specificity of methylation patterns has enabled the development of clinically valuable biomarkers. In ESCC, researchers developed a 12-marker diagnostic panel based on promoter and gene-body methylation patterns that accurately distinguishes tumor from normal tissue [10]. Additionally, a 4-marker prognostic panel effectively stratifies patients into high-risk and low-risk groups, potentially guiding treatment decisions [10]. Similarly, in central nervous system cancers, DNA methylation-based classifiers have standardized diagnoses across over 100 subtypes and altered histopathologic diagnosis in approximately 12% of prospective cases [1].

Liquid biopsy applications represent another promising avenue, where targeted methylation assays combined with machine learning provide early detection of many cancers from plasma cell-free DNA [1]. These approaches demonstrate excellent specificity and accurate tissue-of-origin prediction, enhancing organ-specific screening paradigms. The success of these applications relies heavily on understanding the distinctive methylation patterns characteristic of different genomic regions and their functional consequences.

The comprehensive mapping of DNA methylation across the genomic geography of CpG islands, shores, shelves, and open seas has revealed complex regulatory landscapes with profound implications for normal development, aging, and disease. The distinct methylation patterns characteristic of each region provide both biological insights and practical biomarkers for clinical application. Advances in detection technologies, from bisulfite sequencing to emerging enzymatic methods and long-read sequencing, continue to enhance our resolution of these epigenetic landscapes.

Future research directions will likely focus on integrating multi-omic data to understand the interplay between methylation geography and other regulatory layers, including histone modifications, chromatin accessibility, and three-dimensional genome architecture. Additionally, the development of more sophisticated computational models, particularly foundation models pretrained on diverse methylation datasets, promises to unlock deeper biological insights from increasingly complex epigenetic data. As these technologies mature, methylation-based diagnostic and prognostic tools are poised to become integral components of precision medicine approaches across a spectrum of diseases, particularly in oncology and age-related conditions. The continued exploration of genomic methylation geography will undoubtedly yield novel discoveries and clinical applications in the coming years.

DNA methylation, the covalent addition of a methyl group to the cytosine ring within CpG dinucleotides, represents a fundamental epigenetic mechanism that records cellular experiences without altering the underlying DNA sequence [1]. This process creates a dynamic cellular memory that reflects the interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental exposures, effectively serving as a molecular ledger of a cell's history. The enzymes DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) act as "writers" that establish and maintain these methylation patterns, while Ten-eleven translocation (TET) family enzymes function as "erasers" that actively remove these marks through a stepwise oxidation process [1]. This delicate balance between methylation and demethylation enables the epigenetic landscape to remain both stable enough to maintain cellular identity across divisions and plastic enough to respond to developmental cues and environmental challenges.

The positioning of methylation marks across the genome carries profound functional significance, with patterns in promoter regions typically associated with transcriptional repression, while gene body methylation often correlates with active transcription [7]. These patterns are established and refined throughout development, creating a record of cellular lineage decisions, and are maintained with remarkable fidelity during cell division through the action of DNMT1, which recognizes hemi-methylated DNA strands during replication and restores the methylation pattern on the new strand [1]. When these carefully maintained patterns become disrupted, they can serve as powerful biomarkers of disease pathogenesis, particularly in cancer, neurodevelopmental disorders, and autoimmune conditions [1] [14] [15]. This whitepaper explores how these methylation patterns function as a cellular record, linking them to lineage commitment, developmental processes, and disease mechanisms, with particular emphasis on analytical approaches for interpreting average methylation coverage signal profiles across genomic regions.

Molecular Mechanisms: Writing, Reading, and Erasing Methylation Marks

The establishment, interpretation, and removal of DNA methylation marks involve sophisticated molecular machinery that translates epigenetic information into functional outcomes. The DNMT family enzymes, including DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, catalyze the transfer of methyl groups from S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) to cytosine bases, primarily in CpG dinucleotide contexts [1]. While DNMT3A and DNMT3B establish de novo methylation patterns, DNMT1 maintains these patterns during DNA replication, ensuring their faithful transmission to daughter cells and thus preserving cellular memory across generations.

The functional consequences of DNA methylation are primarily mediated by "reader" proteins that interpret these epigenetic marks and recruit additional effector complexes. Methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD) proteins, particularly MBD2, recognize methylated DNA and recruit chromatin-modifying complexes such as the nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylase (NuRD) complex, which promotes chromatin compaction and transcriptional repression [14]. The MBD2 protein exists in multiple isoforms (MBD2a, MBD2b, and MBD2c) with distinct functional properties through domain-specific truncations, adding regulatory complexity to how methylation marks are interpreted [14].

The active removal of methylation marks is equally crucial for epigenetic plasticity, particularly during developmental reprogramming and in response to environmental signals. The TET family enzymes (TET1, TET2, TET3) initiate DNA demethylation through the oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), and further to 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) [1]. These oxidized methylcytosines can then be replaced with unmodified cytosines through base excision repair pathways, completing the demethylation cycle and erasing epigenetic information when needed.

DOT Visualization: DNA Methylation Dynamics

Analytical Methodologies: Profiling the Methylome

Advancements in methylation profiling technologies have been instrumental in deciphering the complex patterns that constitute the cellular epigenetic record. The choice of methodology involves important trade-offs between resolution, coverage, DNA input requirements, and cost, making platform selection critical for experimental design [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Genome-wide DNA Methylation Profiling Technologies

| Technique | Resolution | Coverage | DNA Input | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | ~80% of CpGs | 1μg [7] | Gold standard for comprehensive methylation mapping | High cost; DNA degradation from bisulfite treatment [7] |

| Enzymatic Methyl-Seq (EM-seq) | Single-base | Comparable to WGBS | Lower than WGBS [7] | Preserves DNA integrity; reduces sequencing bias | Relatively new method; requires validation |

| Illumina MethylationEPIC BeadChip | Single CpG site | >935,000 sites [7] | 500ng [7] | Cost-effective; standardized analysis; high throughput | Limited to predefined CpG sites; no non-CpG context |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Single-base | ~2 million CpGs [15] | 100ng [15] | Cost-efficient for CpG-rich regions; focused coverage | Bias toward CpG islands; incomplete genome coverage |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) | Single-base | Genome-wide, including challenging regions | ~1μg [7] | Long reads for haplotype phasing; no conversion needed | Higher error rate; requires substantial DNA input |

Each method follows a distinct workflow from sample preparation to data generation, with implications for downstream analysis and interpretation of methylation patterns.

DOT Visualization: Methylation Analysis Workflow

Methylation in Cellular Lineage and Development

DNA methylation patterns serve as a precise molecular clock and positioning system that guides cellular differentiation and maintains lineage commitment. During embryonic development, waves of genome-wide demethylation and remethylation establish the epigenetic blueprint that defines cell fate and tissue specificity. This programming is particularly evident in the regulation of key developmental genes, where methylation patterns in enhancers and promoters lock in transcriptional programs that maintain cellular identity through subsequent divisions.

In immune cell development, DNA methylation plays a particularly well-characterized role in lineage determination. The differentiation of T cells and B cells is intricately governed by DNA methylation patterns that ensure the activation or repression of lineage-specific genes [14]. MBD2, as a key reader of methylated DNA, further modulates chromatin accessibility and transcriptional activity in immune cells, underscoring the crucial role of methylation in maintaining immune homeostasis [14]. Research has demonstrated that MBD2 regulates early T cell development, particularly in double-negative T cells within the thymus, through modulation of the WNT signaling pathway, affecting both apoptosis and proliferation of these precursor cells [14].

The stability of these developmental methylation patterns makes them ideal for tracing cellular lineages, even in complex tissues. Single-cell methylation profiling technologies are particularly powerful for revealing methylation heterogeneity at the cellular level, offering unprecedented insights into cellular dynamics and lineage relationships in developing systems [1]. These approaches can reconstruct developmental trajectories and reveal how stochastic methylation events contribute to cellular diversity within seemingly homogeneous cell populations.

Disease Pathogenesis: When the Cellular Record Becomes Corrupted

Aberrant DNA methylation patterns are hallmarks of numerous diseases, with hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes and genome-wide hypomethylation being particularly characteristic of cancer [1] [14]. In autoimmune disorders, a predominance of DNA hypomethylation is observed, leading to the aberrant expression of normally silenced genes and breakdown of immune tolerance [14]. The following table summarizes key disease contexts where methylation alterations play established pathogenic roles.

Table 2: DNA Methylation Alterations in Human Disease

| Disease Category | Specific Condition | Key Methylation Alterations | Functional Consequences | Diagnostic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Colorectal Cancer | Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor promoters; global hypomethylation [7] | Uncontrolled proliferation; genomic instability | Liquid biopsy for early detection; monitoring MRD [1] [8] |

| Autoimmune Disorders | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | Genome-wide hypomethylation, especially in T cells [14] | Overexpression of autoreactive genes; loss of immune tolerance | Disease activity biomarkers; therapeutic response monitoring |

| Autoimmune Disorders | Sjögren's Syndrome (SS) | 29,462 DMRs identified (24,116 hyper-, 5,346 hypomethylated) [15] | Immune dysregulation; exocrine gland dysfunction | Potential diagnostic biomarkers in salivary gland tissue |

| Neurodevelopmental Disorders | Various rare genetic syndromes | Disease-specific episignatures in blood methylation profiles [1] | Disrupted neuronal development and function | Diagnostic classification using ML classifiers [1] |

| High-Altitude Pathology | Chronic Mountain Sickness | Altered methylation in HIF pathway genes (EPAS1, EGLN1) [16] | Disrupted hypoxia response; excessive erythropoiesis | Adaptation capacity assessment; disease risk prediction |

In cancer, DNA methylation-based classifiers have demonstrated remarkable diagnostic utility. For central nervous system tumors, methylation profiling has standardized diagnoses across over 100 subtypes and altered histopathologic diagnosis in approximately 12% of prospective cases [1]. In liquid biopsy applications, targeted methylation assays combined with machine learning provide early detection of many cancers from plasma cell-free DNA, showing excellent specificity and accurate tissue-of-origin prediction [1]. Techniques like enhanced linear splint adapter sequencing (ELSA-seq) have emerged as promising approaches for detecting circulating tumor DNA methylation with high sensitivity and specificity, enabling precise monitoring of minimal residual disease and cancer recurrence [1].

In autoimmune conditions like Sjögren's Syndrome, integrated multi-omics approaches have revealed extensive methylation alterations linked to pathogenic mechanisms. A recent study identifying 29,462 differentially methylated regions between SS and control tissue found promoter methylation changes in nine hub genes (LCP2, BTK, LAPTM5, ARHGAP9, IKZF1, WDFY4, CSF2RB, ARHGAP25, DOCK8) involved in immune response, transcriptional regulation, and inflammation [15]. This methylation dysregulation creates a molecular environment permissive for the lymphocytic infiltration and exocrine gland dysfunction characteristic of the disease.

Computational Analysis: Deciphering Patterns from Data

The analysis of DNA methylation data presents unique computational challenges, particularly for whole-genome sequencing approaches that generate billions of data points across the epigenome. The "Pipeline Olympics" benchmarking study systematically compared computational workflows for processing DNA methylation sequencing data against an experimental gold standard, identifying optimal strategies for various research applications [17]. Key considerations in methylation data analysis include:

Preprocessing and Quality Control: Raw sequencing data must undergo adapter trimming, quality filtering, and alignment to reference genomes. For bisulfite-converted data, specialized aligners like BSMAP account for C-to-T conversions [15]. Quality metrics such as bisulfite conversion rates (typically >99%), coverage depth (≥10x for confident calling), and CpG coverage uniformity are critical for ensuring data integrity [15].

Differential Methylation Analysis: Differentially methylated CpGs (DMCs) are typically identified using statistical tests like the Mann-Whitney U test, requiring minimum thresholds for methylation difference (≥0.1) and sequencing depth (≥5x) [15]. Differentially methylated regions (DMRs) are detected using algorithms like Metilene, which employs binary segmentation combined with statistical tests (MWU-test and 2D KS-test), with criteria including average methylation difference ≥0.1, containing ≥5 DMCs, and adjacent DMC distance ≤200 bp [15].

Advanced Analytical Approaches: Machine learning methods have revolutionized methylation analysis, with conventional supervised methods (support vector machines, random forests, gradient boosting) being employed for classification, prognosis, and feature selection across tens to hundreds of thousands of CpG sites [1]. More recently, deep learning approaches including multilayer perceptrons and convolutional neural networks have been applied to tumor subtyping, tissue-of-origin classification, and survival risk evaluation [1]. Transformer-based foundation models pretrained on extensive methylation datasets (e.g., MethylGPT trained on >150,000 human methylomes) show particular promise for clinical applications through their ability to capture nonlinear interactions between CpGs and genomic context [1].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Methylation Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MspI Restriction Enzyme | Cleaves at CCGG sites regardless of methylation status | RRBS library preparation [15] | Enriches for CpG-rich regions; reduces sequencing costs |

| EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) | Bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines | Pretreatment for WGBS, RRBS, and EPIC array [7] | Critical for conversion efficiency; optimized for minimal DNA degradation |

| Rapid RRBS Library Prep Kit (Acegen) | All-in-one RRBS library preparation | Genome-wide methylation profiling with reduced representation [15] | Streamlined workflow; compatible with low input DNA (100ng) |

| Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip v2.0 (Illumina) | Microarray-based methylation profiling | Large cohort studies; biobank-scale epigenomics [7] | Interrogates >935,000 CpG sites; standardized processing pipelines |

| Nanobind Tissue Big DNA Kit (Circulomics) | High-molecular-weight DNA extraction | Preparation for long-read sequencing (ONT) [7] | Preserves DNA integrity; essential for third-generation sequencing |

| APOBEC/TET Enzyme Mixtures | Enzymatic conversion of unmodified cytosines | EM-seq library preparation [7] | Alternative to bisulfite; reduced DNA fragmentation |

| BSMAP Software | Alignment of bisulfite sequencing reads | Mapping converted reads to reference genomes [15] | Accounts for C-to-T conversions; compatible with various sequencing platforms |

| ChAMP R Package | Preprocessing and analysis of EPIC array data | Quality control, normalization, and DMR calling [7] | Comprehensive pipeline for Illumina methylation arrays |

Future Perspectives and Clinical Translation

The field of DNA methylation research is rapidly evolving toward clinical applications, with several diagnostic platforms already entering the global healthcare market [1]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with methylation data is particularly promising for developing more precise, comprehensive, and rapid diagnostic tools based on DNA methylation markers [1]. Emerging trends include:

Liquid Biopsy Applications: Methylation-based liquid biopsies represent a paradigm shift in cancer detection and monitoring. The exceptional stability of DNA methylation patterns in circulating cell-free DNA, combined with the tissue-specific nature of these marks, enables non-invasive detection of tumors and identification of their tissue of origin [1] [8]. Technologies like Active-Seq, which enables isolation of DNA containing unmodified CpG sites using a mutated bacterial methyltransferase enzyme, show particular promise for tumor-informed disease profiling in cancer patients [8].

Multi-Omics Integration: Combining methylation data with transcriptomic, proteomic, and genomic information provides a more comprehensive understanding of disease mechanisms. In Sjögren's Syndrome, integration of methylation and transcriptomic data identified nine hub genes with coordinated epigenetic and expression changes, revealing complex regulatory networks underlying disease pathogenesis [15].

Therapeutic Targeting: The dynamic nature of DNA methylation makes it an attractive therapeutic target. Emerging therapies focusing on DNA methylation modulation have shown preliminary success, underscoring proteins like MBD2 as mechanistically rational and clinically actionable targets for autoimmune disease management [14]. Similarly, inhibitors of DNMTs and MBD proteins show promise in restoring normal gene expression and mitigating disease progression through epigenetic remodeling [14].

As these technologies mature, standardization and benchmarking will be critical for clinical implementation. The "Pipeline Olympics" initiative represents an important step toward this goal by providing continuable benchmarking of computational workflows for DNA methylation sequencing data against experimental gold standards [17]. Such efforts will ensure that the rich information contained within the methylation record can be reliably extracted and translated into improved patient care across a spectrum of human diseases.

The normal methylome refers to the comprehensive landscape of DNA methylation patterns in healthy, non-diseased human cells. DNA methylation, the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of a cytosine residue in a CpG dinucleotide, is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism that governs gene expression and chromatin organization without altering the underlying DNA sequence [18]. It provides a critical window into cellular identity and developmental processes, serving as a stable molecular record of a cell's lineage and functional specialization [2]. The establishment of reference atlases using purified cell types is paramount because DNA methylation is highly cell-type-specific. Previous studies based on bulk tissues or cell lines suffered from the critical limitation of analyzing unspecified mixtures of cells, which obscures the true, cell-intrinsic methylation patterns and confounds biological interpretation [2] [18]. These atlases provide an foundational resource for understanding basic biology and a healthy baseline against which dysregulation in diseases like cancer and autoimmune disorders can be measured.

Methodological Foundations for Atlas Construction

Constructing a high-resolution methylome atlas requires meticulous cell purification and state-of-the-art sequencing technologies. The following workflow outlines the key experimental steps, from tissue sample to data analysis.

Critical Experimental Protocols

Cell Purification and Purity Assessment

The integrity of a methylome atlas hinges on the purity of the starting cell populations. Key steps include:

- Tissue Dissociation: Fresh, healthy tissues are dissociated using enzymatic and mechanical methods to create single-cell suspensions while minimizing cellular stress [2].

- Fluorescent Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Cells are sorted based on specific surface markers to isolate highly pure populations (>90% purity on average) of defined cell types. For example, immune cells can be separated using CD45, CD3, CD19, and CD14 markers, while epithelial populations may use EpCAM [2].

- Purity Validation: Flow cytometry post-sorting, coupled with gene expression analysis and DNA methylation patterns themselves, is used to confirm sample purity. In the seminal atlas study, some samples like colon fibroblasts showed lower purity (78%), highlighting the necessity of this rigorous validation [2].

DNA Methylation Profiling Technologies

Multiple technologies exist for genome-wide DNA methylation detection, each with distinct strengths and limitations as systematically compared in recent large-scale evaluations [19] [20].

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Methylation Detection Methods

| Method | Resolution | Genomic Coverage | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | ~80% of CpGs (∼30 million sites) | Gold standard; comprehensive; absolute methylation levels [2] [19] | DNA degradation; high cost; computational challenges [19] |

| Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq) | Single-base | Comparable to WGBS | Preserves DNA integrity; reduces bias; lower input DNA [19] | Newer method; less established protocols |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) | Single-base (long-read) | Context-dependent | Long reads for phasing; direct detection; no conversion [19] [20] | Higher DNA input; evolving accuracy; specialized equipment |

| Illumina EPIC Array | Pre-defined sites | ~935,000 CpG sites | Cost-effective; high-throughput; standardized analysis [19] [18] | Limited to pre-designed sites; misses intergenic regions |

For reference atlas construction, WGBS has been the method of choice due to its comprehensive coverage. The protocol involves:

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treatment of DNA with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while methylated cytosines remain unchanged [19] [18].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Construction of sequencing libraries from converted DNA followed by deep sequencing (e.g., 150bp paired-end reads at ∼30x coverage) to ensure sufficient depth for accurate methylation calling at each cytosine [2].

- Data Processing: Using specialized tools like

wgbstools[2] orNanopolish(for nanopore data) [20] to map reads to the genome and calculate methylation ratios.

Key Insights from the Normal Methylome Atlas

Robustness and Interindividual Conservation

A fundamental finding from methylome atlases is the remarkable robustness of DNA methylation patterns across individuals. For most cell types, less than 0.5% of genomic regions (methylation blocks) show a difference of ≥50% in methylation levels across different donors [2]. This minimal interindividual variation stands in stark contrast to the 4.9% of regions that vary between different cell types from the same individual. This demonstrates that DNA methylation is primarily determined by cell lineage and cell-type-specific programmes rather than genetic or environmental influences, making it an exceptionally stable marker of cellular identity [2].

Methylation as a Record of Developmental History

Unsupervised clustering of methylomes from purified cell types systematically recapitulates key elements of tissue ontogeny, revealing that methylation patterns serve as a molecular memory of developmental history [2]. For instance:

- Pancreatic islet cells (alpha, beta, delta) cluster together and further group with other pancreatic cells (ductal, acinar) and hepatocytes, reflecting their shared endodermal origins [2].

- Similarly, epithelial cells from the gastrointestinal tract form a distinct cluster, while blood cell types group separately, consistent with their respective developmental lineages.

- Specific methylation patterns established during early embryogenesis can persist into adulthood. For example, 892 genomic regions were identified that remain unmethylated specifically in endoderm-derived cell types decades after development, demonstrating the long-term stability of these epigenetic marks [2].

Cell-Type-Specific Methylation Markers and Their Genomic Context

Differential analysis across cell types identifies genomic regions with distinct methylation patterns that define cellular identity.

Table 2: Characteristics of Cell-Type-Specific Methylation Markers

| Marker Type | Genomic Context | Potential Functional Role | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unmethylated Markers | Transcriptional enhancers; DNA binding sites for tissue-specific regulators [2] | Potentially permissive for transcription factor binding and enhancer activity [2] [21] | Majority (97%) of differentially methylated regions [2] |

| Hypermethylated Markers | CpG islands; Polycomb targets; CTCF binding sites [2] | Potential role in shaping cell-type-specific chromatin looping and architecture [2] | Rare |

Notably, the vast majority (97%) of cell-type-specific differential methylation manifests as regions that are unmethylated in a specific cell type but methylated in others, rather than the reverse [2]. These uniquely unmethylated regions are frequently enriched in transcriptional enhancers and contain DNA binding motifs for tissue-specific transcription factors, suggesting they play a permissive role in cell-type-specific gene regulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Methylome Atlas Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FACS Antibodies | Cell type purification | Antibodies against cell surface markers (e.g., CD45, EpCAM) for isolation of pure populations [2] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | DNA treatment for methylation detection | Converts unmethylated C to U; critical for WGBS [19] [18] |

| WGBS Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries | Must be compatible with bisulfite-converted DNA [2] |

| Reference Methylome Atlas | Data resource for comparison | Provides normal baseline (e.g., 39 cell types from Loyfer et al. [2]) |

| Analysis Software | Data processing and interpretation | wgbstools [2], Nanopolish (for nanopore) [20], minfi (for arrays) [19] |

Applications and Research Implications

Reference methylome atlases serve as indispensable resources for numerous research applications:

- Liquid Biopsies: Cell-type-specific methylation signatures enable the deconvolution of cell-free DNA in liquid biopsies, allowing for non-invasive detection of tissue damage, transplantation rejection, and cancer [2].

- Disease Studies: The normal methylome provides an essential baseline for identifying pathogenic methylation changes in diseases like cancer, autoimmune disorders (e.g., SLE [18]), and developmental disorders.

- Functional Genomics: By identifying regions of differential methylation, these atlases pinpoint potential functional regulatory elements (enhancers, promoters) critical for cell identity and function [2] [21].

- Epigenome Engineering: Understanding normal methylation patterns informs efforts to manipulate the epigenome using tools like zinc finger-DNMT3A fusions [22] for basic research and therapeutic purposes.

The relationship between methylation changes and chromatin dynamics during cell differentiation is complex, as recent studies using neural progenitor models show that DNA demethylation and chromatin accessibility can be temporally discordant, with demethylation often occurring on an extended timeline [21]. This underscores the importance of reference atlases in interpreting dynamic epigenetic processes.

From Signal to Insight: Technologies and Workflows for Methylation Profiling and Analysis

DNA methylation analysis is a cornerstone of epigenomic research, providing critical insights into gene regulation, cellular differentiation, and disease mechanisms. The field has evolved from microarray-based technologies to various sequencing-based approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations in coverage, resolution, and applicability. For researchers investigating average methylation coverage signals across genomic regions, the selection of an appropriate profiling technology is paramount, as it directly influences data quality, experimental design, and biological interpretation. Current technologies primarily fall into four categories: whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS), microarray platforms, enzymatic conversion methods (EM-seq), and emerging nanopore sequencing. WGBS provides comprehensive base-resolution methylation maps but historically required high sequencing costs, while RRBS offers a cost-effective alternative by focusing on CpG-rich regions. Microarray technology has powered most epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) to date through platforms like Illumina's Infinium BeadChip, balancing throughput with cost but offering limited genomic coverage. More recently, enzymatic conversion methods have emerged that reduce DNA damage compared to bisulfite treatment, and nanopore sequencing enables direct detection of methylation modifications without conversion. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these core technologies, focusing on their application in generating robust average methylation coverage signals for genomic research and drug development.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of DNA Methylation Analysis Technologies

| Technology | Resolution | Genome Coverage | DNA Input | DNA Damage | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGBS | Single-base | Comprehensive (>90% CpGs) | High (50-100ng) | High (bisulfite-induced fragmentation) | Gold-standard methylome maps, DMR discovery |

| RRBS | Single-base | Targeted (CpG-rich regions ~1-3% of genome) | Moderate (10-100ng) | High (bisulfite-induced fragmentation) | Cost-effective promoter/CpG island methylation |

| Microarrays | Single-CpG site | Limited (~3% of CpGs with EPICv2) | Low (50-250ng) | Minimal | EWAS, population studies, epigenetic clocks |

| Enzymatic (EM-seq) | Single-base | Comprehensive (>90% CpGs) | Low (10ng) | Minimal (preserves DNA integrity) | WGBS alternative for degraded/limited samples |

| Nanopore | Single-base | Comprehensive | Variable (50ng-1μg) | None (native DNA) | Real-time methylation, haplotype phasing |

Table 2: Performance Metrics and Practical Considerations

| Technology | Sensitivity/Specificity | Multiplexing Capability | Cost per Sample | Recommended Coverage/Depth | Differential Methylation Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGBS | High (with sufficient coverage) | Moderate (multiplexed libraries) | High ($800-$1500) | 5×-30× depending on application [23] | Excellent for large and small DMRs |

| RRBS | High in covered regions | High (multiplexed libraries) | Moderate ($200-$500) | 5×-10× per CpG | Limited to CpG-rich regions |

| Microarrays | High for targeted CpGs | Very high (96- sample chips) | Low ($50-$150) | N/A (pre-designed probes) | Good for hypothesis-free EWAS |

| Enzymatic (EM-seq) | High (comparable to WGBS) | Moderate (multiplexed libraries) | Moderate-High ($400-$1000) | Similar to WGBS | Comparable to WGBS with better low-input performance |

| Nanopore | Improving (R10.4.1 flow cells) | Moderate (48 samples/flow cell) | Variable (reagent costs) | 10×-20× for most applications | Good for long-range epigenetic patterns |

Technical Protocols and Methodological Details

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS)

Experimental Protocol: The standard WGBS protocol begins with DNA fragmentation via sonication or enzymatic digestion, followed by end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation using methylated adapters. The critical bisulfite conversion step utilizes sodium bisulfite treatment under denaturing conditions, typically at 95°C for 5-10 minutes, followed by incubation at 60°C for several hours. This process converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. Following conversion, desulfonation neutralizes the reaction and purified DNA is amplified via PCR before sequencing. Post-sequencing, bioinformatic processing involves quality control (FastQC), adapter trimming (Trim Galore), alignment to a bisulfite-converted reference genome (Bismeth, BSMAP), and methylation extraction (MethylDackel). For differential methylation analysis, tools like BSmooth or MOABS are recommended, employing statistical models that account for the binomial distribution of methylation data [23].

Coverage Recommendations: Based on comprehensive simulation experiments using high-quality reference datasets, the recommended coverage for WGBS depends on the biological context and analysis goals. For differential methylated region (DMR) discovery between divergent sample types (e.g., brain cortex vs. embryonic stem cells), 5×-10× coverage per sample provides the optimal balance between sensitivity and cost, with gains in true positive rate falling off rapidly beyond this range. For comparisons of closely related cell types (e.g., CD4+ vs. CD8+ T-cells), higher coverage of 10×-15× may be necessary to detect smaller methylation differences. Importantly, sequencing beyond 15× coverage provides diminishing returns, with resources better allocated to additional biological replicates [23].

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS)

Experimental Protocol: RRBS utilizes restriction enzyme digestion (typically MspI, which recognizes CCGG sites) to selectively target CpG-rich regions of the genome, including promoters and CpG islands. Following digestion, fragments undergo end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation. Size selection (40-220 bp or 50-300 bp fragments) enriches for CpG-rich regions while excluding repetitive elements and intergenic regions. The size-selected fragments then undergo bisulfite conversion and library preparation similar to WGBS. Bioinformatics analysis involves specialized RRBS aligners that account for the reduced genome complexity. The methodology transfers well across mammalian species, with in silico prediction aiding study design by identifying restriction enzyme cut sites and their genomic distribution [24].

Microarray-Based Methylation Analysis

Experimental Protocol: Microarray analysis begins with DNA extraction followed by bisulfite conversion of 250-500ng genomic DNA. Converted DNA is whole-genome amplified, fragmented, and hybridized to array probes. For Illumina's Infinium platforms, two bead types detect methylation status: Type I probes use two different beads per CpG site (one for methylated and one for unmethylated states), while Type II probes use a single bead type. Following hybridization, single-base extension with fluorescently labeled nucleotides incorporates labels corresponding to methylation status. Imaging detects fluorescence signals, and specialized software (GenomeStudio, R packages like minfi) converts intensities to beta values (0-1 scale representing methylation proportion) and M-values (log2 ratios for statistical analysis). The recently introduced Methylation Screening Array (MSA) represents a conceptual shift with 284,317 probes specifically curated from EWAS publications and cell-type-specific studies rather than offering uniform genomic coverage [25].

Enzymatic Methylation Sequencing (EM-seq)

Experimental Protocol: EM-seq utilizes enzymatic rather than chemical conversion to distinguish methylated cytosines. The NEBNext EM-seq protocol employs two key enzymes: TET2 oxidizes 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) to further oxidized derivatives, while T4-BGT glucosylates 5hmC to protect it from subsequent deamination. APOBEC3A then deaminates unmodified cytosines to uracils, while leaving oxidized 5mC and glucosylated 5hmC unaffected. During PCR amplification, uracils are amplified as thymines while protected bases are amplified as cytosines. This process achieves the same C-to-T transitions as bisulfite treatment but with significantly reduced DNA damage. Library preparation follows standard steps including fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification. Comparative studies show EM-seq provides highly concordant methylation calls with bisulfite sequencing while demonstrating significantly higher library yields, reduced DNA fragmentation, and improved performance with degraded samples like FFPE tissue and cfDNA [26].

Nanopore Sequencing

Experimental Protocol: Nanopore sequencing detects DNA methylation natively without chemical conversion or enzymatic treatment. Library preparation involves DNA extraction, end-repair, adapter ligation (LSK109 kit), and loading onto flow cells (R9.4.1 or R10.4.1). During sequencing, DNA molecules pass through protein nanopores, creating characteristic current disruptions ("squiggles") that are decoded in real-time. Methylated bases produce distinct current signatures compared to unmethylated bases, allowing direct detection. Basecalling and methylation detection are performed simultaneously using modified basecalling models in Dorado (successor to Guppy) with Remora technology for improved accuracy. Adaptive sampling can be implemented for target enrichment, increasing coverage on regions of interest. The technology is particularly valuable for detecting complex structural variants and repeat expansions associated with disease, as it provides long reads that maintain haplotype phasing information [27] [28] [29].

Experimental Design and Workflow Visualization

Technology Selection Workflow

Comparative Workflow Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Methylation Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technology Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits (e.g., Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation series) | Chemical conversion of unmethylated C to U | WGBS, RRBS, Microarrays | Optimize for minimal DNA degradation; conversion efficiency critical |

| EM-seq Kits (e.g., NEBNext EM-seq) | Enzymatic conversion via TET2/APOBEC3A | EM-seq | Preserves DNA integrity; superior for degraded samples [26] |

| Methylated Adapters | Library preparation without altering methylation status | WGBS, RRBS, EM-seq | Essential for maintaining original methylation patterns during amplification |

| Bisulfite-Treated DNA Standards | Quality control and conversion efficiency monitoring | All bisulfite-based methods | Verify complete conversion; identify incomplete conversion artifacts |

| Nanopore Sequencing Kits (e.g., LSK109) | Native DNA library preparation for methylation detection | Nanopore sequencing | Enables direct detection without conversion; adaptive sampling capable [28] |

| Methylation-Specific Arrays (e.g., Illumina EPICv2, MSA) | Hybridization-based methylation profiling | Microarray analysis | MSA offers trait-focused content with 5hmC capability [25] |

| Size Selection Beads (e.g., SPRIselect) | Fragment size selection for targeted approaches | RRBS | Critical for enriching CpG-rich regions (40-220bp) [24] |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Directions

Liquid Biopsy Applications

DNA methylation biomarkers in liquid biopsies represent a promising minimally invasive approach for cancer detection and monitoring. Methylation patterns emerge early in tumorigenesis and remain stable throughout tumor evolution, making them ideal biomarkers. The inherent stability of DNA methylation provides advantages over more labile molecules like RNA, particularly in challenging sample types like circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) where DNA quantity is limited. Different liquid biopsy sources offer varying advantages: blood provides systemic coverage but with dilution effects, while local sources like urine (for urological cancers), bile (for biliary tract cancers), and cerebrospinal fluid (for CNS malignancies) often yield higher biomarker concentrations with reduced background noise. For blood-based applications, plasma is generally preferred over serum due to higher ctDNA enrichment and stability. Technological advances in all methylation profiling platforms have improved sensitivity for detecting rare methylated alleles in liquid biopsies, with targeted approaches like EM-seq showing particular promise for low-input cfDNA applications [9] [26].

Single-Cell and Multi-Omic Integration

Advanced applications increasingly combine methylation profiling with other molecular readouts. Single-cell multi-omic approaches, such as SPLONGGET, simultaneously capture genomic, epigenomic, and transcriptomic information from individual cells, providing unprecedented resolution of cellular heterogeneity. Nanopore sequencing achieves 79-93% single-cell genome coverage at ≥5x compared to just 6% from Illumina short-read data, enabling reliable detection of small variants, allele-specific copy number alterations, structural variants, gene expression data, and open chromatin patterns from the same cells. For cancer research, this approach reveals molecular changes linked to therapy resistance and tumor evolution. Integration of methylation data with GWAS findings strengthens causal inference and functional annotation of disease-associated loci, particularly when analyzed in relevant tissue contexts [27].

Targeted Methylation Analysis

Targeted approaches enable high-depth methylation analysis of specific genomic regions without whole-genome sequencing costs. The recently developed t-nanoEM method combines enzymatic conversion with hybridization capture for targeted long-read methylation analysis, achieving coverage up to 570x with 5kb N50 read lengths. This approach enables haplotype-aware methylation analysis and identification of allele-specific methylation patterns, which is particularly valuable for understanding imprinting disorders and regulatory mechanisms. In cancer research, targeted methylation sequencing of specific gene panels (e.g., for breast cancer biomarkers) provides sensitive detection of methylation changes in clinical specimens, including FFPE tissue [30].

The optimal methylation profiling technology depends on specific research objectives, sample characteristics, and resource constraints. For comprehensive methylome mapping, WGBS remains the gold standard, though EM-seq offers advantages for delicate samples. RRBS provides cost-effective targeted coverage of CpG-rich regions, while microarrays excel in high-throughput population studies. Nanopore sequencing enables unique applications in real-time analysis, long-range phasing, and direct detection. Understanding the coverage requirements, experimental protocols, and analytical considerations for each platform ensures robust experimental design and reliable interpretation of average methylation coverage signals across genomic regions. As technologies continue to evolve, integration of methylation data with other omics modalities and advanced bioinformatic approaches will further enhance our understanding of epigenetic regulation in health and disease.

DNA methylation, a fundamental epigenetic modification, plays a critical role in gene regulation, cellular differentiation, embryonic development, and the pathogenesis of numerous diseases without altering the underlying DNA sequence [19] [1]. The accurate and comprehensive assessment of DNA methylation patterns is thus essential for understanding their functional significance in biological processes and disease mechanisms, particularly in the context of studying average methylation coverage signal profiles across genomic regions. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate methylation profiling method involves navigating a complex landscape of competing technologies, each with distinct strengths and limitations in terms of resolution, genomic coverage, accuracy, sample input requirements, and cost-effectiveness.

The field has evolved significantly from reliance on a single gold-standard method to a diversified toolkit that includes bisulfite-based sequencing, microarray technologies, enzymatic conversion approaches, and third-generation sequencing platforms. Bisulfite sequencing has long been the default method for analyzing methylation marks due to its single-base resolution, but the associated DNA degradation poses a significant concern for sample integrity [19] [31]. Although several alternative methods have been proposed to circumvent this issue, there remains no clear consensus on which method might be better suited for specific study designs, particularly those focused on methylation coverage signals across diverse genomic regions.

This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for method selection by systematically comparing current DNA methylation detection technologies across critical parameters. By synthesizing evidence from recent comparative studies and technological innovations, we aim to equip researchers with the analytical tools necessary to align their experimental goals with the most appropriate profiling methodology, whether the focus is on discovery-based epigenome-wide association studies, targeted biomarker validation, or population-scale screening initiatives.

DNA Methylation Profiling Technologies: A Comparative Framework

Core Methodologies and Underlying Principles

Current DNA methylation profiling methods can be broadly categorized into four principal approaches based on their underlying biochemical principles and detection mechanisms: