Differential Expression Analysis: A Beginner's Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

This guide provides a comprehensive introduction to differential expression (DE) analysis, a pivotal technique in transcriptomics for identifying genes associated with diseases and treatments.

Differential Expression Analysis: A Beginner's Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive introduction to differential expression (DE) analysis, a pivotal technique in transcriptomics for identifying genes associated with diseases and treatments. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts of bulk and single-cell RNA-seq, explores state-of-the-art methodologies like limma, edgeR, and DESeq2, and addresses key challenges such as data sparsity and normalization. The article offers practical insights for troubleshooting analysis pipelines and emphasizes the critical importance of experimental validation and method benchmarking to ensure robust, reproducible findings that can reliably inform biomedical research and therapeutic development.

What is Differential Expression? Core Concepts and Experimental Design

Defining Differential Expression Analysis and Its Role in Biomedical Research

Differential expression analysis is a foundational technique in molecular biology used to identify genes or transcripts that exhibit statistically significant changes in expression levels between two or more biological conditions or sample types [1]. This methodology is a cornerstone of genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, enabling researchers to decipher the molecular mechanisms underlying biological processes such as disease progression, treatment response, and environmental adaptation [1]. By comparing gene expression patterns between different states (e.g., healthy versus diseased tissue, treated versus untreated cells), scientists can pinpoint specific molecular players involved in these processes, leading to discoveries with profound implications for basic research and clinical applications.

The analytical process involves rigorous statistical comparison of gene abundance measurements, typically derived from high-throughput technologies like RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) [2]. The core objective is to determine whether observed differences in read counts for each gene are greater than what would be expected due to natural random variation alone [2]. When properly executed, differential expression analysis provides a powerful hypothesis-generating engine that drives discovery across biomedical research domains, from cancer biology to infectious disease studies.

Key Applications in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Biomarker and Therapeutic Target Discovery

Differential expression analysis plays a pivotal role in identifying disease-associated genes that may serve as diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive biomarkers [3]. In precision medicine, these biomarkers enable more precise patient stratification and treatment selection [3]. Furthermore, comparing expression profiles between diseased and healthy tissues helps reveal genes critically involved in pathogenesis, potentially unveiling new therapeutic targets for drug development [1]. For instance, in cancer research, differential expression analysis can identify oncogenes that are upregulated in tumors or tumor suppressor genes that are downregulated, both of which may represent promising targets for pharmacological intervention [1] [4].

Mechanistic Studies and Treatment Response

Understanding how different treatments or interventions alter gene expression patterns provides crucial insights into their mechanisms of action [1]. In pharmaceutical research, this approach helps identify genes that respond to drug treatment, potentially revealing both intended therapeutic pathways and unintended off-target effects [1]. Additionally, differential expression analysis can elucidate how environmental factors—such as toxin exposure or dietary changes—influence gene expression, bridging the gap between external stimuli and biological responses [1].

Cross-Domain Applications

The versatility of differential expression analysis extends across multiple omics domains, including transcriptomics (RNA), proteomics (proteins), and epigenomics (epigenetic modifications) [1]. This cross-domain applicability enables a more comprehensive understanding of molecular mechanisms, as researchers can integrate findings from different biological layers to build more complete models of biological systems and disease processes [1].

Methodological Framework: From Data to Discovery

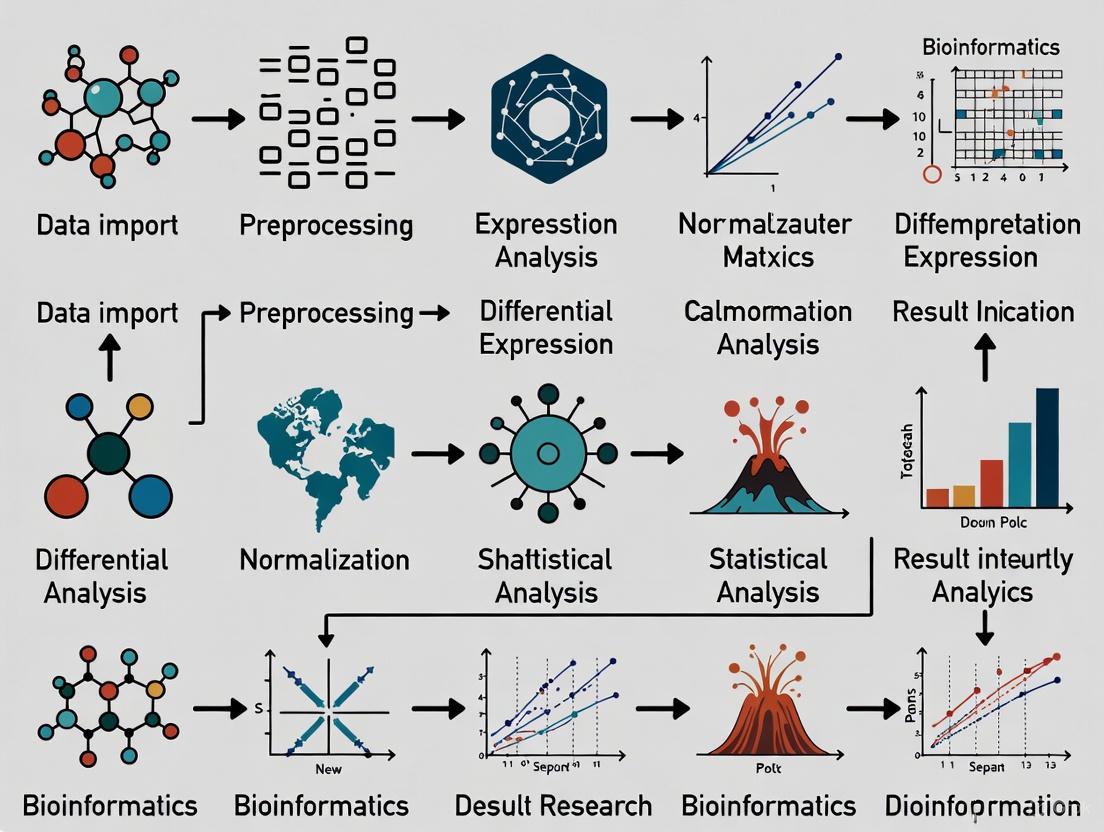

The differential expression analysis pipeline follows a structured sequence of steps to ensure robust and interpretable results. Figure 1 illustrates the complete workflow from sample preparation through biological interpretation.

Figure 1. Complete workflow for differential expression analysis, spanning from sample preparation to biological interpretation.

Core Analytical Steps

The analytical phase of differential expression analysis consists of several critical computational and statistical procedures:

Data Pre-processing: Raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files) undergo quality assessment and filtering to remove technical artifacts and low-quality data [1] [2]. The quality-filtered reads are then aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome using tools such as HISAT2 or TopHat [2] [5].

Expression Quantification: Aligned reads are summarized and aggregated over genomic features (genes or transcripts) using tools like HTSeq, producing a count matrix where each value represents the number of reads mapped to a particular feature in a specific sample [2].

Normalization: This crucial step adjusts for technical variations between samples, particularly differences in sequencing depth (total number of reads) and RNA composition [3]. Common methods include the Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) used by edgeR and the geometric mean approach employed by DESeq2 [3].

Statistical Testing: Normalized data undergoes statistical analysis to identify genes with significant expression changes. Tools like DESeq2 and edgeR use models based on the negative binomial distribution to account for biological variability and technical noise in count data [3] [6].

Multiple Test Correction: Since thousands of statistical tests are performed simultaneously (one per gene), specialized correction methods such as the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure are applied to control the false discovery rate (FDR) [1]. The resulting adjusted p-values (q-values) determine which genes are declared differentially expressed.

Interpretation: The final step involves biological interpretation of the resulting differentially expressed gene list, typically through functional enrichment analysis to identify overrepresented biological processes, pathways, or functional categories [1].

Tool Selection Framework

Choosing an appropriate analytical tool depends on multiple experimental factors. Figure 2 provides a decision framework for selecting the most suitable differential expression method.

Figure 2. Decision framework for selecting differential expression analysis methods based on experimental design and data characteristics.

Comparative Analysis of Differential Expression Tools

Tool Performance and Characteristics

The selection of an appropriate differential expression tool significantly impacts results interpretation. Different packages employ distinct statistical models, normalization approaches, and data handling procedures. Table 1 summarizes the key features of major differential expression analysis tools.

Table 1. Comparison of Major Differential Expression Analysis Tools

| Tool | Publication Year | Statistical Distribution | Normalization Method | Key Features | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | 2014 [3] | Negative binomial [3] [4] | DESeq method [3] | Shrinkage estimation for fold changes and dispersion; robust for low count genes [3] | Bulk RNA-seq with small sample sizes; paired comparisons [3] [7] |

| edgeR | 2010 [3] | Negative binomial [3] [4] | TMM [3] | Empirical Bayes estimation; exact tests for differential expression [3] | Bulk RNA-seq with multiple conditions; complex experimental designs [3] |

| limma | 2015 [3] | Log-normal [3] | TMM [3] | Linear models with empirical Bayes moderation; fast computation [8] [4] | Bulk RNA-seq and microarray data; multiple group comparisons [8] [4] |

| NOIseq | 2012 [3] | Non-parametric [3] | RPKM [3] | Noise distribution estimation; no replication requirement [7] | Data with limited replicates; when distribution assumptions are violated [3] |

| SAMseq | 2013 [3] | Non-parametric [3] | Internal [3] | Mann-Whitney test with Poisson resampling; robust to outliers [3] | Large sample sizes; non-normally distributed data [3] |

| MAST | 2015 [9] | Two-part generalized linear model [9] | TPM/FPKM [9] | Accounts for dropout events in single-cell data; models both discrete and continuous components [9] | Single-cell RNA-seq data with high zero-inflation [9] |

Tool Selection Guidelines

Based on comparative studies and tool characteristics, researchers can follow these evidence-based guidelines for method selection:

For typical bulk RNA-seq experiments: DESeq2 and limma+voom generally provide the most consistent and reliable results across various experimental conditions [7]. DESeq2 is particularly noted for its robust handling of studies with small sample sizes, a common scenario in RNA-seq experiments [3].

When distributional assumptions may be violated: Non-parametric methods like NOIseq perform well without requiring specific distributional assumptions, making them suitable for data with complex characteristics [3] [7].

For single-cell RNA-seq data: Specialized methods like MAST, SCDE, and scDD that explicitly model single-cell specific characteristics (e.g., zero-inflation, high heterogeneity) are recommended over bulk RNA-seq tools [9].

Consensus approaches: Combining results from multiple methods (e.g., consensus across DESeq2, limma, and NOIseq) can yield more reliable differentially expressed genes with reduced false positives [7].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful differential expression analysis requires both wet-lab reagents and computational resources. Table 2 outlines key components of the researcher's toolkit.

Table 2. Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Differential Expression Analysis

| Category | Item | Specification/Example | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | RNA Isolation Kits | Column-based or magnetic bead systems | High-quality RNA extraction with integrity number (RIN) >8 for reliable sequencing [2] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Strand-specific, poly-A selection or rRNA depletion | Convert RNA to sequence-ready libraries; determine transcript coverage and strand specificity [2] | |

| RNA-Seq Platforms | Illumina, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore | Generate raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files); determine read length, depth, and error profiles [5] | |

| Quality Control Tools | Bioanalyzer, Qubit, Nanodrop | Assess RNA quality, quantity, and purity before library preparation [2] | |

| Computational Tools | Alignment Software | HISAT2, STAR, TopHat2 [2] [5] | Map sequencing reads to reference genome/transcriptome [2] |

| Quantification Tools | HTSeq, featureCounts | Generate count matrices from aligned reads [2] | |

| Differential Expression Packages | DESeq2, edgeR, limma | Statistical analysis to identify differentially expressed genes [3] [4] | |

| Functional Analysis Tools | clusterProfiler, Enrichr | Biological interpretation of DEGs through pathway and ontology enrichment [3] |

Differential expression analysis represents a powerful methodological framework for identifying molecular changes across biological conditions. When properly executed with appropriate statistical tools and validated through follow-up experiments, this approach continues to drive fundamental discoveries in biomedical research. As sequencing technologies evolve and new computational methods emerge, differential expression analysis remains an indispensable tool for unraveling the complexity of biological systems and advancing human health.

The field continues to evolve with emerging methodologies such as machine learning approaches that may complement traditional differential expression analysis, particularly for identifying complex patterns in large, heterogeneous datasets [3]. However, regardless of methodological advances, careful experimental design, appropriate quality control, and biologically informed interpretation remain fundamental to generating meaningful insights from differential expression studies.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics, enabling researchers to capture detailed snapshots of gene expression. Two primary methodologies have emerged: bulk RNA-seq and single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq). Both are powerful tools for exploring gene activity, but they offer fundamentally different perspectives and are suited to distinct biological questions [10] [11]. Bulk RNA-seq provides a population-averaged gene expression profile, measuring the combined RNA from all cells in a sample. In contrast, single-cell RNA-seq dissects this population to examine gene expression at the resolution of individual cells [12]. This in-depth technical guide will compare these two approaches, highlighting their differences, applications, and methodologies to help you select the right strategy for your research, particularly within the context of differential expression analysis.

Core Principles and Key Differences

Understanding the fundamental distinctions between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq is crucial for experimental design.

Bulk RNA-Sequencing is a well-established method that analyzes the average gene expression from a population of thousands to millions of cells [10] [13]. In this workflow, RNA is extracted from the entire tissue or cell population, converted to complementary DNA (cDNA), and sequenced to generate a single, composite gene expression profile for the sample [14]. This approach is ideal for homogeneous samples or when the research goal is to understand the overall transcriptional state of a tissue.

Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing takes gene expression analysis to a higher resolution by examining the transcriptome of each individual cell separately [10]. The process begins with the dissociation of tissue into a viable single-cell suspension [14]. Individual cells are then isolated, often using microfluidic devices like the 10x Genomics Chromium system, where each cell is partitioned into a nanoliter-scale droplet containing a barcoded gel bead [14] [15]. The RNA from each cell is tagged with a unique cellular barcode, allowing sequencing reads to be traced back to their cell of origin, thus enabling the reconstruction of individual transcriptomes [14].

The table below summarizes the critical differences between the two technologies:

Table 1: Key Differences Between Bulk and Single-Cell RNA-Seq

| Feature | Bulk RNA Sequencing | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Average of cell population [10] | Individual cell level [10] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower (~$300 per sample) [10] | Higher (~$500 to $2000 per sample) [10] |

| Data Complexity | Lower, easier to process [10] [11] | Higher, requires specialized computational methods [10] [15] |

| Cell Heterogeneity Detection | Limited, masks diversity [10] [16] | High, reveals diverse cell types and states [10] [16] |

| Rare Cell Type Detection | Limited or impossible [10] | Possible, can identify rare populations [10] [12] |

| Gene Detection Sensitivity | Higher per sample [10] | Lower per cell, due to technical noise and dropout events [10] [15] |

| Sample Input Requirement | Higher amount of total RNA [10] | Lower, can work with just a few picograms of RNA from a single cell [10] |

| Ideal Application | Homogeneous populations, differential expression between conditions [10] [17] | Heterogeneous tissues, cell type discovery, developmental trajectories [10] [12] |

Applications and Use Cases

Each sequencing method is suited to different research needs, as evidenced by numerous scientific studies.

Applications of Bulk RNA-Seq

Bulk RNA-seq is best for large-scale studies focused on the overall transcriptomic landscape.

- Differential Gene Expression Analysis: It is widely used to compare gene expression profiles between different experimental conditions (e.g., diseased vs. healthy, treated vs. control) to identify genes that are upregulated or downregulated [14].

- Biomarker Discovery: Bulk RNA-seq has been instrumental in identifying RNA-based biomarkers for disease diagnosis, prognosis, or patient stratification [10] [14]. A study on pancreatic cancer, for instance, used bulk RNA-seq to identify differential expression of simple repetitive sequences as potential tumor biomarkers [10].

- Transcriptome Characterization: It is a powerful tool for annotating novel transcripts, including isoforms, non-coding RNAs, alternative splicing events, and gene fusions [10] [14]. A comprehensive analysis of nearly 7,000 cancer samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas used bulk RNA-seq to detect novel and clinically relevant gene fusions involved in cancer [10].

Applications of Single-Cell RNA-Seq

Single-cell RNA-seq is ideal for investigating cellular complexity and heterogeneity.

- Characterizing Heterogeneous Cell Populations: scRNA-seq can identify novel cell types, cell states, and rare cell subtypes [14]. For example, a study of mouse embryonic stem cells identified a rare subpopulation that highly expressed Zscan4 genes, revealing cells with greater differentiation potential [10].

- Reconstructing Developmental Trajectories: By analyzing transcriptomes from individual cells, researchers can infer developmental pathways and lineage relationships, understanding how cellular heterogeneity evolves over time [14] [12].

- Immune and Cancer Profiling: scRNA-seq has been pivotal in discovering new immune cell subsets and unraveling tumor heterogeneity [10] [14]. A study of metastatic lung cancer used scRNA-seq to reveal changes in plasticity induced by non-small cell lung cancer, providing insights not possible with bulk sequencing [10].

- Rare Disease-Associated Cells: This technology can identify extremely rare cells that are critical to disease pathology, such as CFTR-expressing pulmonary ionocytes in cystic fibrosis, which occur at a rate of only 1 in 200 cells [10].

Experimental Design and Workflow

A successful transcriptomics study requires careful planning and execution. Key considerations include sequencing depth, the number of biological replicates, and strategies to minimize batch effects [18]. For bulk RNA-seq, a crucial design factor is the RNA-extraction protocol, which typically involves either poly(A) selection to enrich for mRNA or ribosomal RNA depletion [18]. For scRNA-seq, the first and most critical step is the preparation of a high-quality single-cell suspension with high cell viability, free of clumps and debris [14].

The workflows for bulk and single-cell RNA-seq diverge significantly at the initial stages, as illustrated below.

Differential Expression Analysis: Methods and Considerations

Differential expression (DE) analysis aims to identify genes with statistically significant expression changes between conditions. The approach differs markedly between bulk and single-cell data.

Analyzing Bulk RNA-Seq Data

For bulk RNA-seq, DE analysis typically involves comparing gene expression counts between sample groups using methods that account for the count-based nature of the data and its variability.

- Common Tools: Widely used tools like DESeq2 [19] and edgeR [13] [18] employ a negative binomial generalized log-linear model to test for differential expression [13].

- Workflow: After raw read processing, alignment, and quantification, a counts table is generated. Following quality control and normalization, these tools statistically assess each gene for expression changes between conditions, providing fold-change values and adjusted p-values [18].

Analyzing Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data

The analysis of scRNA-seq data is more complex due to its high dimensionality, sparsity, and the hierarchical structure where cells are nested within samples [15] [16]. Treating individual cells as independent replicates leads to pseudoreplication and false discoveries, as cells from the same sample are more similar to each other than to cells from different samples [16]. Therefore, the sample, not the cell, must be treated as the experimental unit. Several methodological approaches have been developed to address this:

- Pseudobulk Methods: This approach involves summing the UMI counts for a specific cell type across all cells within each biological sample to create a "pseudobulk" expression profile per sample [16]. Standard bulk RNA-seq DE tools like DESeq2 or edgeR can then be applied to these aggregated profiles [19] [16]. This is a computationally efficient and robust way to account for sample-to-sample variability.

- Mixed-Effects Models: These models explicitly account for the correlation of cells from the same sample by including a random effect for sample identity, while the condition of interest (e.g., case vs. control) is modeled as a fixed effect [16]. Tools like NEBULA and MAST (with a random effect term) implement this approach, though it can be computationally intensive for large datasets [16].

- Differential Distribution Testing: Single-cell data enables researchers to look beyond differences in mean expression. Methods like IDEAS and distinct test whether the entire distribution of a gene's expression (including its variance or modality) differs between conditions [19] [16]. IDEAS, for instance, estimates the expression distribution for each individual and then tests whether these distributions are different between groups of individuals [19].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for RNA-Seq Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Beads | Enriches for polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA by hybridization [18] [17]. | mRNA enrichment in bulk RNA-seq library prep. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular tags that label individual mRNA molecules during reverse transcription to correct for PCR amplification bias [15]. | Accurate transcript counting in single-cell and bulk protocols. |

| Chromium Controller (10x Genomics) | A microfluidic instrument that partitions single cells into Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) for barcoding [14]. | High-throughput single-cell library preparation. |

| Cell Hashtag Oligos | Antibody-derived tags that label cells from individual samples with unique barcodes, enabling sample multiplexing [14]. | Pooling multiple samples in a single scRNA-seq run to reduce costs and batch effects. |

| DESeq2 | A bulk RNA-seq statistical package using a negative binomial model for differential expression testing [19] [18]. | Identifying DEGs from bulk data or pseudobulk data from scRNA-seq. |

| NEBULA | A fast negative binomial mixed model for differential expression analysis of multi-subject single-cell data [16]. | Cell-type-specific DE analysis across individuals while accounting for subject-level effects. |

Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq are complementary, not competing, technologies. Bulk RNA-seq remains a cost-effective and powerful choice for identifying overall gene expression changes in large cohort studies or when working with homogeneous samples [10] [11]. Single-cell RNA-seq is indispensable for deconvoluting cellular heterogeneity, discovering rare cell types, and reconstructing cellular trajectories [10] [12].

The future of transcriptomics lies in integrated approaches [10] [17]. Combining bulk, single-cell, and emerging technologies like spatial transcriptomics—which preserves the spatial context of gene expression—provides a more holistic view of biological systems [12] [17]. Furthermore, multi-omics approaches that combine scRNA-seq with assays for chromatin accessibility (scATAC-seq) or protein abundance are becoming increasingly common, offering a more comprehensive view of cellular functions [10]. As these technologies continue to evolve and become more accessible, they will undoubtedly deepen our understanding of the molecular underpinnings of health and disease.

Differential gene expression analysis represents a cornerstone of modern transcriptomics, enabling researchers to identify molecular mechanisms underlying health and disease. The journey from raw sequencing data to a reliable count matrix is a critical, yet often overlooked, phase where choices in quantification directly impact all downstream analyses and biological conclusions [20]. This technical guide details the process of transforming raw sequencing reads into a gene count matrix, explaining the core principles, methodologies, and sources of uncertainty inherent in RNA-seq quantification, framed for beginners embarking on differential expression research [21].

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) leverages next-generation sequencing to measure the abundance of RNA transcripts in a biological sample at a given time [22]. The primary data output is millions of short sequence reads. The fundamental goal of quantification is to assign these reads to specific genomic features (like genes or transcripts) and summarize them into a count table that serves as the starting point for differential expression analysis [23].

This process is non-trivial. Raw read counts cannot be directly used to compare expression between samples due to differences in sequencing depth, gene length, and RNA composition [24]. Furthermore, the data is subject to various technical and biological variances that must be accounted for to make accurate biological inferences [25]. Understanding how a count matrix is generated, and the uncertainties introduced during this process, is essential for correctly interpreting differential expression results.

From Raw Data to Read Alignments

The initial phase of RNA-seq analysis involves processing the raw sequence data into a format suitable for quantification.

Raw Data and Quality Control

RNA-seq data typically begins as FASTQ files, which contain the nucleotide sequences for millions of fragments and an associated quality score for each base call [23]. Key considerations at this stage include:

- Read Type: Single-end vs. paired-end protocols. Paired-end sequencing reads both ends of a fragment, providing more information for alignment and isoform identification [23].

- Quality Assessment: Checks for per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, and overall read quality are crucial before proceeding [23].

Alignment and Quantification Strategies

There are three principal computational approaches for determining the origin of RNA-seq reads [23]. The choice of strategy is a fundamental methodological decision.

Table 1: Comparison of RNA-seq Quantification Approaches

| Approach | Core Methodology | Key Tools | Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Alignment & Counting | Aligns reads to the genome, then counts overlaps with gene exons. | STAR, Rsubread featureCounts [23] | Simplicity; preferred for poorly annotated genomes. | Can be computationally intensive; requires a reference genome and GTF annotation file. |

| Transcriptome Alignment & Quantification | Aligns reads to the transcriptome, estimates transcript expression. | RSEM [23] | Can produce accurate quantification, good for samples without DNA contamination. | Requires a well-annotated transcriptome (e.g., from GENCODE or Ensembl). |

| Pseudoalignment | Rapidly assigns reads to transcripts without full alignment. | Salmon, kallisto [23] | Computational efficiency; mitigates effects of DNA contamination and GC bias. | Speed comes from a different algorithmic approach; transcript-level quantification can be noisier. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the three main paths from raw sequencing data to a gene count matrix:

Normalization and Quantification Measures

After read assignment, expression levels must be normalized to enable cross-sample comparison. Different quantification measures have been developed, but they are not all suitable for differential expression analysis.

Common Quantification Measures

- FPKM/RPKM: Fragments (or Reads) Per Kilobase of exon per Million mapped fragments. This is a within-sample normalization method that corrects for gene length and sequencing depth, allowing comparison of expression between different genes within the same sample [24].

- TPM: Transcripts Per Million is similar to FPKM but with the calculation order changed. It is considered a more stable metric because the sum of all TPMs is constant across samples [24].

- Normalized Counts: These are raw counts that have been normalized by a statistical method, such as the median-of-ratios method in DESeq2 or the TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) in edgeR, specifically designed to account for library size and composition differences between samples for the purpose of cross-sample comparison and differential testing [21] [24].

Why Normalized Counts are Preferred for Differential Expression

A comparative study on RNA-seq data from patient-derived xenograft models provided compelling evidence that normalized count data are the best choice for cross-sample analysis [24]. The study found that hierarchical clustering based on normalized counts grouped replicate samples from the same model together more accurately than TPM or FPKM. Furthermore, normalized counts demonstrated the lowest median coefficient of variation and the highest intraclass correlation values across replicates [24]. This is because FPKM and TPM "normalize away" factors that are essential for between-sample statistical testing, and they can perform poorly when transcript distributions differ significantly between samples [24].

Table 2: Key Quantification Measures for RNA-seq Data

| Measure | Definition | Primary Use | Suitable for Cross-Sample DE Analysis? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Counts | Unaltered number of reads assigned to a feature. | Input for statistical normalizers (DESeq2, edgeR). | No, requires normalization. |

| FPKM/RPKM | Fragments per kilobase per million mapped fragments. | Within-sample gene comparison. | Not recommended [24]. |

| TPM | Transcripts per million. | Within-sample gene comparison. | Not recommended [24]. |

| Normalized Counts | Raw counts normalized for library size/composition (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR). | Cross-sample comparison and DE analysis. | Yes, this is the recommended measure. |

Uncertainty in Quantification and Experimental Design

Quantification is an estimation process with inherent uncertainty, which can be classified into technical and biological variance.

Statistical Modeling of RNA-seq Data

Differential expression packages like DESeq2 and edgeR model expression data using the negative binomial distribution [21]. This distribution is chosen because it accommodates the "over-dispersed" nature of count data where the variance is greater than the mean [21]. These tools create a model and perform statistical testing for the expected true value of gene expression, rather than testing directly on the input counts.

The Critical Role of Experimental Design

Proper experimental design is paramount for ensuring that quantification uncertainty can be accurately measured and accounted for.

- Replicates: Biological replicates (samples from different biological units) are essential to measure biological variance and make inferences about a population. True replication requires independent experimental units [23].

- Confounding and Batch Effects: RNA-seq experiments are sensitive to technical variations (e.g., different days, analysts, or reagent batches). A well-designed experiment balances conditions across these batches to prevent confounding, making it possible to disentangle technical effects from the primary biological effects of interest [23].

The following table details key resources, both data and software, required for RNA-seq quantification.

Table 3: Essential Resources for RNA-seq Quantification

| Resource Category | Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Sequences | Genome FASTA File | Contains the full sequence of the reference genome for alignment. |

| Annotation (GTF/GFF) File | Specifies the genomic locations of annotated features (genes, exons, etc.). | |

| Transcriptome FASTA File | Contains the sequences of all known transcripts for transcriptome-based methods. | |

| Software & Pipelines | Read Aligner (e.g., STAR) | Aligns sequencing reads to a reference genome. |

| Quantification Tool (e.g., Salmon, RSEM) | Assigns reads to features and estimates abundance. | |

| Differential Expression Suite (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR) | Performs statistical normalization and identifies differentially expressed genes. | |

| Data Sources | GENCODE | Provides high-quality reference gene annotations for human and mouse. |

| Ensembl | Provides reference files for a wide range of organisms, including plants and fungi. |

Visualization and Quality Control

Post-quantification, it is vital to perform quality control (QC) on the normalized count data to ensure the normalization process was effective and that samples cluster as expected.

- PCA Plots: Verify that biological replicates cluster together and that treatment groups separate. Normalization should improve this clustering [21].

- Distance Plots: Show the dissimilarity between samples, with replicates expected to have smaller distances [21].

- Other Plots: Density and box plots of normalized expression help verify that distributions across samples have been successfully aligned by the normalization procedure [21].

Advanced visualization methods like parallel coordinate plots and scatterplot matrices can further help researchers detect normalization issues, identify problematic genes or samples, and confirm that the data shows greater variability between treatments than between replicates [25].

The path from raw sequencing data to a count matrix is a foundational process in RNA-seq analysis. Selecting an appropriate quantification strategy (genome, transcriptome, or pseudoalignment) based on the organism and experimental goals, and using normalized counts from robust statistical methods like those in DESeq2 or edgeR for differential expression, is critical for generating reliable biological insights. A well-designed experiment with adequate replication, coupled with rigorous quality control and visualization, allows researchers to accurately quantify and account for uncertainty, ensuring that the subsequent differential expression analysis truly reflects the underlying biology.

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, accurate normalization of gene expression data is a critical prerequisite for obtaining biologically meaningful results. Normalization corrects for technical variations, enabling meaningful comparisons within and between samples. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three foundational normalization metrics—Reads Per Kilobase Million (RPKM), Fragments Per Kilobase Million (FPKM), and Transcripts Per Million (TPM). Framed within the broader context of differential expression analysis for beginners, this review clarifies the calculations, applications, and limitations of each metric. We summarize quantitative data in structured tables, detail experimental protocols for calculation, and provide clear visualizations of workflows. The content is designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select appropriate normalization methods for their RNA-seq studies, thereby ensuring robust and interpretable results in downstream analyses.

The raw output of an RNA-seq experiment consists of counts of reads or fragments mapped to each gene in the genome. These raw counts are not directly comparable due to several technical biases:

- Sequencing Depth: Samples sequenced to a greater depth will yield higher counts for a gene expressed at the same level, simply because more reads are generated [26] [27].

- Gene Length: For a given level of expression, longer genes will generate more reads than shorter genes because they provide a larger template [26] [27].

- RNA Composition: In certain experiments, a few highly expressed genes can consume a substantial fraction of the sequencing library. This can skew the count distribution for other genes and make them appear less expressed in that sample compared to others, even if their true expression level is unchanged [28] [27].

Normalization is the computational process of adjusting the raw count data to account for these technical factors. The primary goal is to produce abundance measures that reflect true biological differences in gene expression rather than technical artifacts [26] [28]. This is an essential step for both exploratory data analysis and formal differential expression testing. Without proper normalization, the identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) is unreliable, potentially leading to false discoveries and incorrect biological conclusions [28].

Understanding the Metrics: Definitions and Calculations

This section dissects the three core metrics, their intended purposes, and their mathematical formulations.

RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase Million)

RPKM was one of the earliest measures developed for normalizing RNA-seq data from single-end experiments [29] [30]. It is designed to facilitate the comparison of gene expression levels within a single sample by normalizing for both sequencing depth and gene length.

- Calculation Steps: The calculation of RPKM follows a specific order of operations:

- Formula: ( RPKM = \frac{\text{Reads mapped to gene}}{\text{(Gene length in kb)} \times \text{(Total mapped reads in millions)} } = \frac{\text{Reads mapped to gene}}{\text{Gene length} \times \text{Total mapped reads}} \times 10^9 ) [26] [24]

FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Million)

FPKM is the direct counterpart to RPKM for paired-end RNA-seq experiments. In paired-end sequencing, two reads are sequenced from a single cDNA fragment. FPKM accounts for this by counting fragments instead of individual reads, thus avoiding double-counting [29] [30].

- Relationship to RPKM: The conceptual meaning and calculation of FPKM are identical to RPKM, with the word "Fragments" replacing "Reads" [31]. For a given transcript, if each fragment is represented by two reads, the FPKM value will be half the RPKM value. In single-end sequencing, where each fragment yields one read, RPKM and FPKM are equivalent [32].

- Formula: ( FPKM = \frac{\text{Fragments mapped to gene}}{\text{(Gene length in kb)} \times \text{(Total mapped fragments in millions)} } = \frac{\text{Fragments mapped to gene}}{\text{Gene length} \times \text{Total mapped fragments}} \times 10^9 ) [24]

TPM (Transcripts Per Million)

TPM is a more recent metric that addresses a critical limitation of RPKM and FPKM. While the formulas appear similar, the order of operations is reversed, leading to a desirable property for cross-sample comparison [29].

- Calculation Steps:

- Normalize for gene length first: Divide the raw read count by the length of the gene in kilobases. This gives Reads Per Kilobase (RPK).

- Sum all RPK values: Sum the RPK values for all genes in the sample to get the total RPK per sample.

- Normalize for sequencing depth: Divide the RPK value for each gene by the "per million" scaling factor, which is the total RPK from step 2 divided by one million. This yields TPM [29] [26].

- Formula: ( TPM = \frac{\text{Reads mapped to gene / Gene length in kb}}{\text{Sum(Reads mapped to all genes / Their lengths in kb)}} \times 10^6 ) [31]

The key advantage of TPM is that the sum of all TPM values in a sample is always constant (one million). This means TPM values represent the relative proportion of each transcript within the total sequenced transcript pool, making them directly comparable across samples [29]. In contrast, the sum of all RPKM or FPKM values in a sample can vary, complicating inter-sample comparisons [29] [27].

The table below provides a consolidated comparison of RPKM, FPKM, and TPM to highlight their key characteristics and appropriate use cases.

Table 1: Comparative overview of RNA-seq normalization metrics

| Feature | RPKM | FPKM | TPM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Name | Reads Per Kilobase Million [26] | Fragments Per Kilobase Million [26] | Transcripts Per Million [29] |

| Sequencing Type | Single-end [29] | Paired-end [29] | Both |

| What is Counted? | Reads | Fragments | Reads (conceptually transcripts) |

| Order of Normalization | Depth then length [29] | Depth then length [29] | Length then depth [29] |

| Sum of Values in a Sample | Variable [27] | Variable [27] | Constant (1 million) [29] |

| Recommended Use | Compare different genes within a sample [30] | Compare different genes within a sample [30] | Compare genes within a sample and relative abundance across samples [29] [30] |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the distinct calculation paths for RPKM/FPKM versus TPM.

Diagram 1: RPKM/FPKM vs. TPM Calculation Workflows

Experimental Protocols and Practical Implementation

Computational Calculation

The metrics discussed can be calculated using various bioinformatics programming languages. Below is an example of how to compute them using Python with the bioinfokit package [26].

Protocol 1: Normalization with Python's bioinfokit package

- Prerequisites: Ensure Python and the

bioinfokitpackage (v0.9.1 or later) are installed. Data should be in a dataframe with genes as rows and samples as columns, and a column for gene length in base pairs. - RPKM/FPKM Calculation:

- TPM Calculation:

A Note on Differential Expression Analysis

For formal differential expression analysis (e.g., identifying genes expressed at different levels between two conditions), specialized statistical methods implemented in tools like DESeq2 and edgeR are the gold standard [24] [27]. These tools use sophisticated normalization approaches (e.g., DESeq2's "median of ratios" [27] or edgeR's "trimmed mean of M-values" [26]) that are more robust for between-sample comparisons than TPM, RPKM, or FPKM.

- DESeq2's Median of Ratios Method: This method does not use gene length in its normalization, as it compares the same gene between samples. Instead, it: a. Calculates a pseudo-reference sample for each gene via the geometric mean across all samples. b. Computes the ratio of each gene's count to its pseudo-reference. c. The median of these ratios for each sample is used as the size factor (normalization factor). d. Raw counts are divided by this size factor to generate normalized counts [27].

- When to Use TPM/RPKM/FPKM: These metrics are highly useful for data visualization, exploratory analysis, and when a normalized expression measure is needed for other downstream tasks (e.g., estimating metabolic fluxes). However, their raw values should not be used as direct input for statistical tests in differential expression tools like DESeq2 or edgeR, which operate on raw counts and perform their own internal normalization [27].

Limitations and Common Misconceptions

A widespread misconception is that because RPKM, FPKM, and TPM are "normalized" values, they are directly comparable across all samples and experimental conditions. This is not always true [31] [33].

- Dependence on Transcriptome Composition: RPKM, FPKM, and TPM measure relative abundance, not absolute concentration. The value for a gene represents its proportion relative to the total population of sequenced transcripts in that sample. If the transcriptome composition changes drastically between samples (e.g., one condition has a few genes that are extremely highly expressed), the relative proportions of all other genes will be compressed, making their TPM values non-comparable between those samples [31] [28].

- Sensitivity to Experimental Protocol: The sample preparation protocol can significantly impact normalized expression values. For example, in a study comparing poly(A)+ selection and rRNA depletion protocols on the same biological sample, the resulting TPM values were vastly different. The rRNA depletion protocol captured a large amount of structural non-coding RNAs, which dramatically altered the composition of the transcriptome and thus the relative proportion (TPM) of protein-coding genes [31]. Therefore, comparing TPM values from studies using different library preparation protocols can be highly misleading.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and solutions for RNA-seq

| Reagent / Solution | Function in RNA-seq Workflow |

|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Selection and enrichment of polyadenylated mRNA from total RNA by binding to the poly(A) tail [31]. |

| rRNA Depletion Probes | Selective removal of abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from total RNA to increase the sequencing coverage of mRNA and other RNA species [31]. |

| Fragmentation Buffer | Chemically or enzymatically breaks full-length RNA or cDNA into shorter fragments of a size suitable for high-throughput sequencing [31]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzyme | Synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from the RNA template, creating a stable library for sequencing [27]. |

| Size Selection Beads (e.g., SPRI) | Solid-phase reversible immobilization beads are used to purify and select for cDNA fragments within a specific size range, ensuring library uniformity [24]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit for RNA-Seq

A successful RNA-seq experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents and computational tools. The table below details key materials used in a typical workflow.

RPKM, FPKM, and TPM are fundamental metrics for understanding and interpreting RNA-seq data. While RPKM/FPKM are suitable for assessing relative gene expression within a single sample, TPM is generally preferred for making comparisons of a gene's abundance across different samples due to its constant sum property. However, it is critical to remember that all three metrics represent relative expression that depends on the transcriptome composition of each sample. For robust differential expression analysis, dedicated statistical methods like DESeq2 and edgeR, which operate on raw counts and employ more advanced normalization techniques, are strongly recommended. By selecting the appropriate metric and understanding its assumptions and limitations, researchers can draw more accurate and reliable biological insights from their transcriptomic studies.

The reliability of scientific findings, particularly in high-throughput biology, hinges on rigorous experimental design. This technical guide examines the foundational principles of replicates, statistical power, and the often-overlooked issue of pooling bias, framed within the context of differential expression analysis. Proper implementation of these principles is critical for generating biologically relevant results that can withstand rigorous scrutiny and contribute meaningfully to the scientific record. We provide a comprehensive overview of methodologies that empower researchers to design robust experiments, avoid common pitfalls, and optimize resource allocation while maintaining statistical integrity.

The modern biology toolbox continues to evolve, with cutting-edge molecular techniques complementing classic approaches. However, statistical literacy and experimental design remain the bedrock of empirical research success, regardless of the specific methods used for data collection [34]. A well-designed experiment ensures that observed differences in gene expression can be reliably attributed to biological conditions of interest rather than technical artifacts or random variation.

The quote from Ronald A. Fisher succinctly captures this imperative: "To consult the statistician after an experiment is finished is often merely to ask him to conduct a post mortem examination. He can perhaps say what the experiment died of" [34]. This perspective is particularly relevant in the context of differential expression analysis, where decisions made during experimental planning fundamentally determine what conclusions can be drawn from the data.

In RNA-sequencing experiments, the basic task involves analyzing count data to detect differentially expressed genes between sample groups. The count matrix represents the number of sequence fragments uniquely assigned to each gene, with higher counts indicating higher expression levels [35]. However, proper interpretation requires careful consideration of multiple factors, including sequencing depth, gene length, and RNA composition, all of which must be accounted for through appropriate normalization and statistical approaches.

The Critical Role of Replication

Biological vs. Technical Replicates

A fundamental distinction in experimental design is between biological replicates and technical replicates. Biological replicates are measurements from biologically distinct samples (e.g., cells, tissues, or animals) that capture the natural biological variation within a condition. Technical replicates are repeated measurements of the same biological sample to account for technical noise introduced during library preparation or sequencing [34].

In differential expression analysis, biological replicates are essential for drawing conclusions about biological phenomena, as they allow researchers to distinguish consistent biological effects from random variation. The misconception that large quantities of data (e.g., deep sequencing or measurement of thousands of genes) ensure precision and statistical validity remains prevalent. In reality, it is the number of biological replicates that determines the reliability of biological inferences [34].

Pseudoreplication and Its Consequences

Pseudoreplication occurs when measurements are treated as independent observations despite originating from the same biological unit or being subject to confounding factors. This practice artificially inflates sample size and increases the risk of false positive findings [34] [36]. Hurlbert coined the term "pseudoreplication" for situations where researchers treat non-independent data points as independent in their analysis, a problem he identified as widespread across biological disciplines [36].

In a typical example involving nested designs, such as testing a greenhouse treatment effect on tomato plants with multiple plants per greenhouse, the greenhouse rather than individual plants constitutes the experimental unit. Any hypothesis test of the treatment should use an error term based on variation among greenhouses rather than variation among individual plants to avoid pseudoreplication [36].

Statistical Power and Sample Size

Power Analysis Fundamentals

Statistical power represents the probability that a test will correctly reject a false null hypothesis (i.e., detect a true effect). Underpowered experiments, which are prevalent across biological research, waste resources and generate unreliable results [37]. Power analysis allows researchers to determine the sample size needed to detect an effect of a given size with a specified degree of confidence [34].

The relationship between power, sample size, effect size, and significance threshold follows established statistical principles. Low statistical power remains a pervasive issue compromising replicability across scientific fields, with an estimated $28 billion wasted annually on irreproducible preclinical science in the United States alone [37].

Power Considerations in High-Throughput Experiments

In RNA-seq experiments, power analysis must account for multiple testing, as thousands of genes are evaluated simultaneously. The false discovery rate (FDR) rather than family-wise error rate is typically controlled in exploratory analyses to balance false positives with statistical power [38]. Tools such as the R package micropower facilitate power analysis for microbiome studies, while similar principles apply to RNA-seq experimental design [34].

Table 1: Replication Success Rates Across Scientific Fields

| Field | Original Positive Outcomes | Replication Success Rate | Original Effect Size | Replication Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychology | 97 | 36% | 0.403 (SD: 0.188) | 0.197 (SD: 0.257) |

| Economics | 18 | 61% | 0.474 (SD: 0.239) | 0.279 (SD: 0.234) |

| Social Sciences | 21 | 62% | 0.459 (SD: 0.229) | 0.249 (SD: 0.283) |

| Cancer Biology | 97 | 43% | 6.15 (SD: 12.39) | 1.37 (SD: 3.01) |

| Ditridecylamine | Ditridecylamine, CAS:101012-97-9, MF:C26H55N, MW:381.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| 1-Bromo-2-methoxy-2-methylpropane | 1-Bromo-2-methoxy-2-methylpropane|19752-21-7 | 1-Bromo-2-methoxy-2-methylpropane (CAS 19752-21-7), a bifunctional halogenated ether for mechanistic studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Data adapted from large-scale replication projects [37]

Understanding and Avoiding Pooling Bias

Test-Qualified Pooling

Test-qualified pooling represents a common but controversial practice in biological research where non-significant terms are dropped from a statistical model, effectively pooling their variation with the error term used to test hypotheses [36]. This approach is often motivated by the desire to increase degrees of freedom and statistical power for testing effects of interest.

The process typically involves fitting a full model based on the experimental design, then removing non-significant terms through sequential testing. The simplified model is then used for final hypothesis testing. Despite being recommended in some statistical textbooks for biologists, this practice introduces substantial risks [36].

Consequences of Inappropriate Pooling

Test-qualified pooling can severely compromise statistical inference through several mechanisms:

Inflated Type I Error Rates: Pooling based on non-significance in preliminary tests biases p-values downward and confidence intervals toward being too narrow, increasing false positive rates [36].

Reduced Reliability: The hoped-for improvement in statistical power is often small or non-existent, while the reliability of statistical procedures is substantially reduced [36].

Pseudoreplication: In nested designs, pooling errors constitutes a form of pseudoreplication that Hurlbert termed "test-qualified sacrificial pseudoreplication" [36].

Table 2: Common Normalization Methods for RNA-seq Data

| Normalization Method | Accounted Factors | Recommended Use | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPM (Counts Per Million) | Sequencing depth | Gene count comparisons between replicates of the same sample group | Not for within-sample comparisons or DE analysis |

| TPM (Transcripts Per Kilobase Million) | Sequencing depth, Gene length | Gene count comparisons within a sample | Not for between-sample comparisons or DE analysis |

| RPKM/FPKM | Sequencing depth, Gene length | Gene count comparisons between genes within a sample | Not recommended for between-sample comparisons |

| DESeq2's Median of Ratios | Sequencing depth, RNA composition | Gene count comparisons between samples and for DE analysis | Not for within-sample comparisons |

| EdgeR's TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) | Sequencing depth, RNA composition | Gene count comparisons between samples and for DE analysis | Not for within-sample comparisons |

Adapted from RNA-seq methodology guides [35]

Practical Implementation for Differential Expression Analysis

Experimental Workflow Design

The following diagram illustrates key decision points in designing a robust differential expression experiment:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for RNA-seq Experiments

| Item | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kit | Extracts high-quality RNA from biological samples | Select based on sample type (cells, tissues, etc.); assess RNA integrity number (RIN >7.0 recommended) [13] |

| mRNA Enrichment Reagents | Enriches for messenger RNA from total RNA | Poly(A) selection kits preferentially capture protein-coding transcripts [13] |

| cDNA Library Prep Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries from RNA | Fragmentation, adapter ligation, and index ligation create sequenceable libraries [13] |

| Sequencing Controls | Monitor technical performance of sequencing run | Include external RNA controls consortium (ERCC) spikes to assess technical variability [34] |

| Alignment Software | Aligns sequence reads to reference genome | STAR aligner provides accurate splice-aware alignment for RNA-seq data [38] |

| Gene Quantification Tool | Generates count matrix from aligned reads | HTSeq-count assigns reads to genomic features using reference annotation [38] |

| Linadryl H | Linadryl H, CAS:19732-39-9, MF:C20H25NO2, MW:311.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,2-Dibromohexane | 2,2-Dibromohexane | High-Purity Reagent | For RUO | High-purity 2,2-Dibromohexane for research. Used in organic synthesis & mechanistic studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Quality Control Assessment

Quality control represents a critical step in the differential expression workflow. Both sample-level and gene-level QC checks help ensure data quality before proceeding with formal statistical testing [35].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduces the high-dimensionality of count data while preserving original variation, allowing visualization of sample relationships in two-dimensional space. In ideal experiments, replicates for each sample group cluster together, while sample groups separate clearly. Unexplained sources of variation may indicate batch effects or other confounding factors that should be accounted for in the statistical model [35].

Hierarchical clustering heatmaps display correlation of gene expression for all pairwise sample combinations. Since most genes are not differentially expressed, samples typically show high correlations (>0.80). Samples with correlations below this threshold may indicate outliers or contamination requiring further investigation [35].

Statistical Analysis Considerations

Model Specification and Analysis

For bulk RNA-seq analyses, DESeq2 has emerged as a preferred tool for differential expression testing [38]. The method requires a count matrix of integer values and employs a negative binomial distribution to model count data, addressing overdispersion common in sequencing data [38].

DESeq2 internally corrects for library size using sample-specific size factors determined by the median ratio of gene counts relative to the geometric mean per gene [35]. This approach accounts for both sequencing depth and RNA composition, making it appropriate for comparisons between samples.

The statistical testing in DESeq2 uses the Wald test by default, which evaluates the precision of log fold change values to determine whether genes show significant differential expression between conditions [38]. To address multiple testing, the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction is typically applied, controlling the expected proportion of false positives among significant findings [38].

Addressing Batch Effects and Covariates

Batch effects represent systematic technical differences between groups of samples processed at different times, by different personnel, or using different reagents [13]. These non-biological factors can introduce substantial variation that confounds biological signals if not properly addressed.

Table 4: Common Sources of Batch Effects and Mitigation Strategies

| Source | Examples | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Multiple researchers, time of day, animal cage effects | Standardize protocols, harvest controls and experimental conditions simultaneously, use littermate controls [13] |

| RNA Processing | Different RNA isolation days, freeze-thaw cycles, reagent lots | Process all samples simultaneously when possible, minimize handling variations [13] |

| Sequencing | Different sequencing runs, lanes, or facilities | Sequence controls and experimental conditions together, balance conditions across runs [13] |

When known sources of variation are identified through PCA or other methods, they can be incorporated into the DESeq2 model using the design formula. For example, including both condition and batch in the design formula (e.g., ~ batch + condition) accounts for batch effects while testing for condition-specific effects [35].

Robust experimental design remains the cornerstone of reliable differential expression analysis. By implementing appropriate replication strategies, conducting power analysis during experimental planning, and avoiding problematic practices like test-qualified pooling, researchers can significantly enhance the validity and reproducibility of their findings. These principles empower scientists to design experiments that become useful contributions to the scientific record, even when generating negative results, while reducing the risk of drawing incorrect conclusions or wasting resources on experiments with low chances of success [34]. As high-throughput technologies continue to evolve, maintaining rigorous attention to these foundational elements will ensure that biological insights gleaned from large datasets reflect underlying biology rather than methodological artifacts.

From Data to Insights: A Practical Guide to DE Analysis Tools and Workflows

Differential expression (DE) analysis is a fundamental step in transcriptomics, enabling researchers to identify genes whose expression levels change significantly between different biological conditions, such as disease states or treatment groups [39]. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the predominant technology for this purpose, offering high reproducibility and a dynamic range for transcript quantification [4]. The power of DE analysis lies in its ability to systematically identify these changes across tens of thousands of genes simultaneously, while accounting for the biological variability and technical noise inherent in RNA-seq experiments [39].

The selection of an appropriate statistical method is crucial for robust and reliable DE analysis. Among the numerous tools developed, three have emerged as the most widely used and cited: limma, edgeR, and DESeq2 [39] [40] [4]. Each employs distinct statistical approaches and modeling assumptions, leading to differences in performance, sensitivity, and specificity under various experimental conditions. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of these three prominent tools, detailing their underlying statistical foundations, practical workflows, and relative strengths to help researchers and drug development professionals make informed analytical choices within the context of their research objectives.

Statistical Foundations and Core Algorithms

The core difference between limma, edgeR, and DESeq2 lies in the statistical models they employ to handle count-based RNA-seq data, particularly their approaches to normalization and variance estimation.

limma (withvoomTransformation)

Originally developed for microarray data, the limma (Linear Models for Microarray Data) package has been adapted for RNA-seq analysis primarily through the voom (variance modeling at the observational level) transformation [41] [42]. limma utilizes a linear modeling framework with empirical Bayes moderation [39]. The voom method converts RNA-seq count data into log-counts per million (log-CPM) values and estimates the mean-variance relationship for each gene. It then calculates precision weights for each observation, allowing the transformed data to be analyzed using limma's established linear modeling pipeline [39] [41]. This empirical Bayes approach moderates the gene-specific variance estimates by borrowing information from the entire dataset, which is particularly beneficial for experiments with small sample sizes [39].

edgeR

edgeR (Empirical Analysis of Digital Gene Expression in R) is based on a negative binomial (NB) distribution model, which is well-suited for representing the overdispersion (variance greater than the mean) characteristic of RNA-seq count data [39] [41] [42]. It employs the Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) method for normalization, which assumes that most genes are not differentially expressed [39] [41] [42]. edgeR offers multiple strategies for estimating dispersion (common, trended, or tagwise) and provides several testing frameworks, including exact tests, generalized linear models (GLMs), and quasi-likelihood F-tests (QLF) [39]. The QLF approach is recommended for complex experimental designs as it accounts for both biological and technical variation [39].

DESeq2

DESeq2 (DESeq2 is an R package available via Bioconductor and is designed to normalize count data from high-throughput sequencing assays such as RNA-Seq and test for differential expression [43].) Like edgeR, it uses a negative binomial distribution to model count data [39] [41]. However, its normalization approach relies on calculating size factors (geometric means) for each sample, rather than TMM [41] [42]. DESeq2 incorporates empirical Bayes shrinkage for both dispersion estimates and log2 fold changes, which improves the stability and interpretability of results, particularly for genes with low counts or high dispersion [39] [44]. This shrinkage approach helps to prevent false positives arising from poorly estimated fold changes and provides better performance for genes with small counts [44].

Table 1: Core Statistical Foundations of limma, edgeR, and DESeq2

| Aspect | limma | DESeq2 | edgeR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Statistical Approach | Linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation [39] | Negative binomial modeling with empirical Bayes shrinkage [39] | Negative binomial modeling with flexible dispersion estimation [39] |

| Data Transformation/Normalization | voom transformation converts counts to log-CPM values [39] |

Internal normalization based on geometric mean (size factors) [41] [42] | TMM normalization by default [39] [41] [42] |

| Variance Handling | Empirical Bayes moderation improves variance estimates for small sample sizes [39] | Adaptive shrinkage for dispersion estimates and fold changes [39] | Flexible options for common, trended, or tagwise dispersion [39] |

| Key Components | • voom transformation• Linear modeling• Empirical Bayes moderation• Precision weights [39] |

• Normalization• Dispersion estimation• GLM fitting• Hypothesis testing [39] | • Normalization• Dispersion modeling• GLM/QLF testing• Exact testing option [39] |

Practical Implementation and Workflows

The following section outlines the standard analytical workflows for each tool, providing reproducible code snippets for implementation in R.

Data Preparation and Quality Control

Proper data preparation is essential for all three methods. The initial steps involve reading the count data, filtering low-expressed genes, and creating a metadata table describing the experimental design.

DESeq2 Analysis Pipeline

DESeq2 performs internal normalization and requires raw, un-normalized count data as input [43].

edgeR Analysis Pipeline

edgeR offers multiple testing approaches; the quasi-likelihood F-test (QLF) is recommended for complex designs.

limma (voom) Analysis Pipeline

The voom transformation enables the application of limma's linear modeling framework to RNA-seq data.

The following diagram illustrates the parallel workflows of these three tools, highlighting their key analytical steps:

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows of DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom

Performance Comparison and Method Selection

Understanding the relative performance characteristics of each tool is essential for appropriate method selection based on specific experimental conditions and research goals.

Sample Size Considerations

Sample size significantly influences the performance and suitability of each DE tool:

- limma: Demonstrates robust performance with at least 3 replicates per condition and excels in handling complex experimental designs with multiple factors [39].

- DESeq2: Suitable for moderate to large sample sizes and shows strong control of false discovery rates (FDR) across various conditions [39].

- edgeR: Efficient even with very small sample sizes (as few as 2 replicates) and performs well with large datasets [39] [41].

Notably, a critical study revealed that for population-level RNA-seq studies with large sample sizes (dozens to thousands of samples), parametric methods like DESeq2 and edgeR may exhibit inflated false discovery rates, sometimes exceeding 20% when the target FDR is 5% [45]. In such scenarios, non-parametric methods like the Wilcoxon rank-sum test demonstrated better FDR control [45].

Agreement and Complementarity Across Methods

Despite their methodological differences, the three tools typically show substantial agreement in their results. Benchmark studies using both real and simulated datasets have demonstrated that they identify overlapping sets of differentially expressed genes, particularly for strongly expressed genes with large fold changes [39] [44]. This concordance across methods, each with distinct statistical approaches, strengthens confidence in the biological validity of the identified DEGs [39].

However, important differences exist in their sensitivity to detect subtle expression changes or genes with specific expression characteristics. edgeR may exhibit advantages in detecting differentially expressed genes with low counts, while DESeq2's conservative approach provides strong fold change estimates [39] [44].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics and Optimal Use Cases

| Aspect | limma | DESeq2 | edgeR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal Sample Size | ≥3 replicates per condition [39] | ≥3 replicates, performs well with more [39] | ≥2 replicates, efficient with small samples [39] [41] |

| Best Use Cases | • Small sample sizes• Multi-factor experiments• Time-series data• Integration with other omics [39] | • Moderate to large sample sizes• High biological variability• Subtle expression changes• Strong FDR control [39] | • Very small sample sizes• Large datasets• Technical replicates• Flexible modeling needs [39] |

| Computational Efficiency | Very efficient, scales well [39] | Can be computationally intensive [39] | Highly efficient, fast processing [39] |

| Limitations | • May not handle extreme overdispersion well• Requires careful QC of voom transformation [39] | • Computationally intensive for large datasets• Conservative fold change estimates [39] | • Requires careful parameter tuning• Common dispersion may miss gene-specific patterns [39] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful differential expression analysis requires both computational tools and appropriate experimental materials. The following table outlines key reagents and resources essential for RNA-seq experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for RNA-seq DE Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality RNA from biological samples | Select based on sample type (tissues, cells, FFPE); maintain RNA integrity (RIN > 8) |

| Library Preparation Kits | Conversion of RNA to sequencing-ready libraries | Consider strand-specificity, input RNA amount, and compatibility with sequencing platform |

| Sequencing Platforms | Generation of raw sequence reads | Illumina most common; consider read length, depth (typically 20-40 million reads/sample), and paired-end vs single-end |

| Reference Genome & Annotation | Mapping reads and determining gene identities | Use most recent versions (e.g., GENCODE, Ensembl) with comprehensive gene models |

| Alignment Software | Mapping sequencing reads to reference genome | Options include STAR, HISAT2; consider speed, accuracy, and splice awareness |

| Count Matrix Generation | Quantifying gene-level expression | Tools like HTSeq-count, featureCounts; require GTF/GFF annotation file |

| R/Bioconductor Packages | Statistical analysis of count data | DESeq2, edgeR, limma require R environment; ensure correct version compatibility |

| High-Performance Computing | Processing large datasets | Sufficient RAM (16GB+), multi-core processors for efficient analysis of multiple samples |

| 2-Hydroxy-5-methylpyrazine | 2-Hydroxy-5-methylpyrazine | High Purity | RUO | High-purity 2-Hydroxy-5-methylpyrazine for flavor chemistry & pharmaceutical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2-(Bromomethyl)benzaldehyde | 2-(Bromomethyl)benzaldehyde | High-Purity Reagent | High-purity 2-(Bromomethyl)benzaldehyde, a key bifunctional building block for organic synthesis and medicinal chemistry research. For Research Use Only. |

limma, edgeR, and DESeq2 represent sophisticated statistical frameworks for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data, each with distinct strengths and optimal application domains. While they share the common goal of robust DE detection, their differing approaches to normalization, variance estimation, and statistical testing make them uniquely suited to particular experimental contexts.

The selection among these tools should be guided by specific experimental parameters, including sample size, study design, and biological questions of interest. limma excels in complex designs and offers computational efficiency, edgeR provides flexibility for small sample sizes and large datasets, while DESeq2 offers robust performance for moderate to large studies with careful FDR control. Recent research highlighting FDR control issues with large sample sizes underscores the importance of method validation and consideration of non-parametric alternatives when appropriate [45].

For researchers embarking on DE analysis, the convergence of results across multiple methods can provide increased confidence in biological findings, while divergent results may highlight genes sensitive to specific statistical assumptions. By understanding the theoretical foundations and practical implementations of these prominent tools, researchers can make informed analytical decisions that enhance the reliability and interpretability of their transcriptomic studies.

Bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is a powerful genome-wide gene expression analysis tool in genomic studies that enables researchers to quantify transcript levels across biological samples under different conditions [46] [47]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this workflow is essential for investigating disease mechanisms, identifying therapeutic targets, and validating drug responses. The fundamental goal of differential expression analysis is to identify genes with statistically significant changes in expression between experimental conditions, such as treated versus untreated cells or healthy versus diseased tissue [48]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive, step-by-step framework for analyzing bulk RNA-seq data, from raw sequencing files to biologically meaningful insights, with a focus on implementation for beginners in the field.

The following diagram illustrates the complete end-to-end workflow for bulk RNA-seq analysis, showing the key stages from raw data to biological interpretation:

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Preparation

The RNA-seq analysis workflow begins with obtaining raw sequencing data in FASTQ format, which contains the nucleotide sequences of each read along with corresponding quality scores at each position [47]. These files can be generated in-house through sequencing experiments or downloaded from public repositories like the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) or The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) using tools such as fasterq-dump or TCGAbiolinks in R [46] [49].

A critical early step is creating a comprehensive sample metadata table that links each FASTQ file to its experimental conditions. This table typically includes sample identifiers, experimental groups, and other relevant variables that will inform the differential expression analysis. Proper sample annotation is essential for meaningful biological interpretation later in the workflow [47].

Step 2: Quality Control and Preprocessing

Raw FASTQ files often contain adapter sequences, low-quality bases, and other artifacts that can compromise downstream analysis. Quality control assesses data quality, while preprocessing removes these technical artifacts.

Essential QC Metrics:

- Per base sequence quality

- Adapter contamination

- GC content distribution

- Sequence duplication levels

- Overrepresented sequences

Tools like FastQC provide comprehensive quality assessment, while Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, or fastp perform preprocessing tasks including adapter trimming, quality filtering, and read cropping [50] [49]. The example below shows a typical command for quality control:

After preprocessing, it's crucial to repeat quality assessment to verify successful artifact removal and ensure data integrity before proceeding to alignment.

Step 3: Read Alignment to Reference Genome

Read alignment involves mapping each sequencing read to its correct location in the reference genome. For RNA-seq data, "splice-aware" aligners are essential because they can properly handle reads that span exon-exon junctions [50].

Alignment Software Comparison

| Tool | Best For | Key Features | Considerations |