DNA Methylation Analysis: A 2025 Researcher's Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for DNA methylation analysis.

DNA Methylation Analysis: A 2025 Researcher's Guide from Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for DNA methylation analysis. Covering foundational epigenetic principles through advanced methodologies, troubleshooting, and validation strategies, it synthesizes current technologies including bisulfite sequencing, enrichment techniques, microarrays, and emerging tools like meCUT&RUN. The content enables informed selection of analytical approaches based on project requirements for resolution, coverage, sample type, and budget, while addressing practical challenges in experimental execution and data interpretation for basic research and clinical translation.

DNA Methylation Fundamentals: From Basic Biology to Epigenetic Regulation

The Role of DNA Methylation in Development and Disease Etiology

DNA methylation is a fundamental enzymatic covalent modification of DNA, involving the addition of methyl groups to DNA, with DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) performing this reaction using S-adenosylmethionine as the methyl group donor [1]. This epigenetic mechanism plays a crucial role in genome regulation across both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms without altering the underlying DNA sequence [2] [3]. The process primarily occurs at cytosine residues in CpG dinucleotides, where a methyl group is attached to the C-5 position of cytosine, forming 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) [3] [4]. CpG islands—genomic regions with high C+G content (>50%) and an observed:expected CpG ratio >0.6—represent important regulatory sites where methylation patterns fashion gene expression profiles during development and can be altered in response to environmental experiences and exposures [2] [3].

The establishment and maintenance of DNA methylation patterns are essential for normal cellular function, with aberrations in these patterns noted in various diseases, particularly cancer [2]. The degree of DNA methylation directly influences gene expression, typically leading to decreased transcription when promoter regions are hypermethylated [3]. This regulation affects critical biological processes including cellular differentiation, embryonic development, genomic imprinting, and X-chromosome inactivation [4]. Cancer risk increases with specific methylation patterns, particularly tumor suppressor gene hypermethylation and oncogene hypomethylation, making DNA methylation analysis an important approach for understanding disease etiology and developing diagnostic biomarkers [3].

DNA Methylation in Normal Development

Mechanisms and Establishing Patterns

During mammalian development, DNA methylation patterns undergo dynamic changes through carefully orchestrated processes. Following fertilization, a wave of genome-wide demethylation occurs to reset epigenetic marks, with subsequent remethylation establishing new patterns during implantation and gastrulation [3]. These patterns are fashioned through the coordinated action of DNA methyltransferases, with DNMT3A and DNMT3B responsible for de novo methylation, while DNMT1 maintains methylation patterns during DNA replication [2]. The establishment of cell-type-specific methylation signatures enables the differentiation of diverse cellular lineages from a common genome, with pluripotent stem cells exhibiting distinct methylation profiles compared to their differentiated counterparts.

DNA methylation regulates gene expression through multiple mechanisms, primarily by inhibiting transcription factor binding to promoter regions or recruiting methyl-binding proteins that promote chromatin condensation into transcriptionally inactive states [3]. The positioning of methyl groups in major grooves of DNA creates physical barriers to protein-DNA interactions, while methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins (MBDs) recruit additional chromatin-modifying complexes that establish repressive chromatin environments. These mechanisms work in concert to silence genes in a tissue-specific manner, allowing the same genetic code to produce diverse cellular phenotypes during organogenesis and tissue maturation.

Developmental Programming and Tissue-Specific Regulation

The developmental programming established through DNA methylation creates stable gene expression patterns that persist throughout the lifespan. Imprinted genes represent a specialized class where methylation marks are established in a parent-of-origin-specific manner, leading to monoallelic expression that is critical for normal growth and neurodevelopment [3]. Tissue-specific methylation occurs at regulatory elements beyond promoters, including enhancers and insulators, fine-tuning spatiotemporal gene expression programs. For instance, methylation patterns in hematopoietic stem cells direct lineage commitment decisions, while in neural stem cells, they regulate neurogenesis and gliogenesis.

Recent evidence indicates that DNA methylation provides a molecular memory that records developmental exposures to hormones, nutrients, and environmental factors [2]. These recorded experiences can shape long-term health trajectories through metabolic programming, immune system calibration, and stress response tuning. The plasticity of methylation patterns during critical developmental windows allows the integration of environmental information into the genome, creating phenotypic diversity beyond genetic determinants while maintaining cellular identity through mitotic divisions.

DNA Methylation in Disease Etiology

Cancer-Associated Methylation Alterations

Aberrant DNA methylation patterns represent a hallmark of cancer, contributing to both tumor initiation and progression through multiple mechanisms. Cancer cells typically exhibit global hypomethylation, which promotes genomic instability and oncogene activation, alongside site-specific hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters that silences their protective functions [3]. These alterations occur early in carcinogenesis, making methylation biomarkers valuable for early detection, particularly for cancers with low survival rates such as pancreatic (10% five-year survival), esophageal (20%), liver (20%), lung (21%), and brain (27%) cancers [3].

Research has identified specific methylation biomarkers across multiple cancer types. A recent study integrating genome-wide DNA methylation profiles and comorbidity patterns identified ALX3, HOXD8, IRX1, HOXA9, HRH1, PTPRN2, TRIM58, and NPTX2 as important methylation biomarkers for the five cancers characterized by low five-year survival rates [3]. The combination of ALX3, NPTX2, and TRIM58—selected from distinct functional groups—achieved 93.3% accuracy in predicting the ten most common cancers, including the initial five low-survival-rate types [3]. This approach demonstrates how methylation biomarkers can be leveraged for effective diagnostic tools targeting early-stage cancer detection.

Table 1: DNA Methylation Biomarkers in Low-Survival-Rate Cancers

| Biomarker | Associated Cancers | Methylation Change | Potential Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALX3 | Pancreatic, Esophageal, Liver, Lung, Brain | Hypermetrylation | Developmental regulation disruption |

| HOXD8 | Pancreatic, Esophageal, Liver, Lung, Brain | Hypermetrylation | Homeobox gene silencing |

| IRX1 | Pancreatic, Esophageal, Liver, Lung, Brain | Hypermetrylation | Transcription factor inactivation |

| HOXA9 | Pancreatic, Esophageal, Liver, Lung, Brain | Hypermetrylation | Developmental pathway alteration |

| HRH1 | Pancreatic, Esophageal, Liver, Lung, Brain | Hypermetrylation | Histamine signaling disruption |

| PTPRN2 | Pancreatic, Esophageal, Liver, Lung, Brain | Hypermetrylation | Protein tyrosine phosphatase loss |

| TRIM58 | Pancreatic, Esophageal, Liver, Lung, Brain | Hypermetrylation | Ubiquitination pathway alteration |

| NPTX2 | Pancreatic, Esophageal, Liver, Lung, Brain | Hypermetrylation | Neuronal signaling disruption |

Molecular Mechanisms in Disease Pathogenesis

The mechanistic links between DNA methylation alterations and disease pathology involve multiple pathways. In cancer, hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes such as BRCA1, MLH1, and p16INK4a directly contributes to uncontrolled cell proliferation, defective DNA repair, and evasion of apoptosis [3]. Simultaneously, hypomethylation of repetitive elements and proto-oncogenes promotes chromosomal instability and activates growth-promoting pathways. These coordinated changes create a permissive environment for tumor development and progression.

Beyond cancer, methylation dysregulation contributes to various complex diseases. In autoimmune disorders, hypomethylation of immune response genes leads to overexpression of inflammatory mediators, while in neurological diseases, aberrant methylation of genes involved in synaptic function, oxidative stress response, and protein aggregation contributes to neuronal dysfunction [2]. Environmental exposures can induce persistent methylation changes that mediate disease risk, with nutritional factors, toxins, stress, and infections all capable of reprogramming the epigenome toward pathological states. The stability of methylation marks makes them both useful biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets for chronic diseases.

Analytical Methods for DNA Methylation Research

Targeted DNA Methylation Analysis

Targeted approaches focus on quantifying DNA methylation states of specific genes or genomic regions, providing precise, base-resolution data suitable for validation studies and diagnostic applications. The most commonly used methods include Pyrosequencing, Quantitative Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (qMeDIP), and methylation-sensitive high resolution melting (MS-HRM) [2]. Each technique offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different research scenarios depending on the required throughput, resolution, and available resources.

Pyrosequencing provides highly quantitative data on methylation percentages at individual CpG sites through sequential nucleotide incorporation and light detection [2]. qMeDIP utilizes antibodies specific to 5-methylcytosine to immunoprecipitate methylated DNA fragments, followed by quantitative PCR analysis of target regions [2]. MS-HRM exploits differential melting properties of methylated versus unmethylated DNA after bisulfite conversion, with melting curve analysis indicating methylation status without the need for sequencing [2]. The selection of an appropriate method depends on factors including the number of target regions, required quantitative precision, sample quality and quantity, and available instrumentation.

Table 2: Comparison of Targeted DNA Methylation Analysis Methods

| Method | Principle | Resolution | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrosequencing | Sequencing-by-synthesis with light detection | Single CpG site | High accuracy and reproducibility; Quantitative; Simple data analysis | Limited multiplexing; Short read length; Medium throughput |

| qMeDIP | Immunoprecipitation with anti-5mC antibodies | ~100-1000bp regions | No bisulfite conversion needed; Compatible with degraded DNA; Good for genome-wide screening | Antibody specificity issues; Relative quantification only; Region-specific primers required |

| MS-HRM | Melting curve analysis after bisulfite conversion | Methylation status of region | No sequencing required; High sensitivity; Cost-effective for few targets | Semi-quantitative; Optimization intensive; Limited multiplexing capability |

| Bisulfite Sequencing | Conversion with sodium bisulfite followed by sequencing | Single base pair | Gold standard; High accuracy; Comprehensive data | Extensive bioinformatics; PCR bias; DNA degradation |

Global and Genome-Wide Methylation Analysis

Global methylation analysis methods provide information on the overall methylation content in a sample, useful for comparative studies and screening applications. Approaches based on high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) of hydrolyzed DNA enable direct, rapid, cost-efficient, and sensitive quantification of methylated nucleobases alongside their unmodified counterparts [4]. This method accurately quantifies 5-methylcytosine and 6-methyladenine, requiring only small amounts of DNA without lengthy bioinformatic analyses [4]. Chemical hydrolysis using HCl efficiently releases methylated and unmethylated nucleobases from DNA, avoiding limitations of enzymatic digestion that can fail with highly methylated DNA [4].

For comprehensive mapping of methylation patterns across the genome, several high-throughput approaches are available. Bisulfite sequencing represents the gold standard, converting unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged, allowing single-base-resolution mapping through subsequent sequencing [2]. The Infinium HumanMethylation450K BeadChip and newer platforms probe hundreds of thousands of CpG sites throughout the genome, balancing coverage with cost-effectiveness for large cohort studies [3]. Emerging long-read sequencing technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore can indirectly detect multiple forms of DNA modifications in native DNA, though they require substantial bioinformatic resources and high DNA input [4].

Standardized Analytical Workflow

A typical DNA methylation analysis workflow involves several standardized steps, regardless of the specific quantification method employed. The process begins with DNA extraction using methods such as proteinase K digestion and phenol-chloroform extraction, followed by quality assessment through UV spectrophotometry [2]. For bisulfite-based methods, DNA treatment with sodium bisulfite represents a critical step, converting unmethylated cytosine to uracil while leaving methylated cytosine unchanged [2]. This conversion enables downstream discrimination based on methylation status.

Following bisulfite conversion, target-specific amplification employs primers designed to avoid CpG sites in their sequence [2]. PCR conditions often incorporate touchdown protocols to increase specificity and sensitivity, with careful optimization of annealing temperatures to overcome sequence bias introduced by bisulfite treatment [2]. The quantification step then utilizes the chosen analytical platform (pyrosequencing, MS-HRM, etc.), followed by data analysis including normalization and statistical evaluation. Quality control measures throughout this workflow are essential, particularly for clinical applications, with the MIQE guidelines providing minimum information standards for publication of quantitative experiments [2].

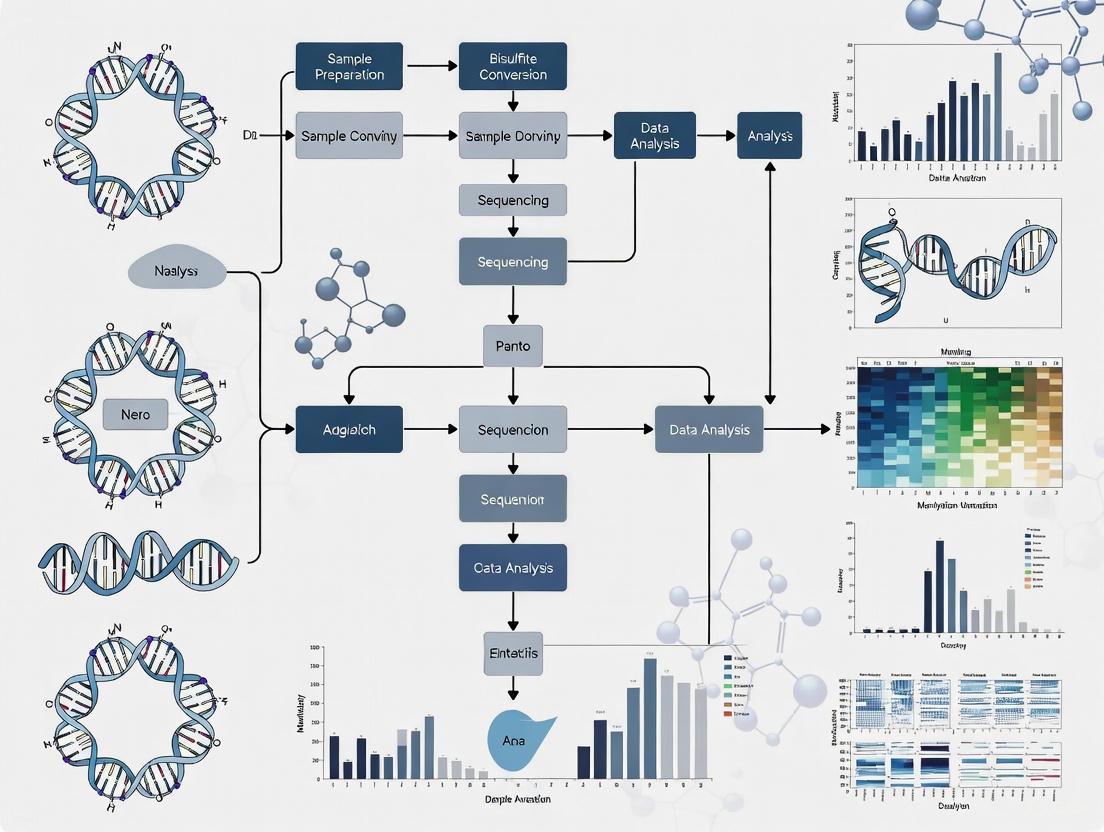

Diagram 1: DNA Methylation Analysis Workflow

Bioinformatics Databases and Tools

Several specialized databases provide comprehensive DNA methylation data across multiple species and experimental conditions. MethBank represents a knowledge base featuring manually curated bio-contexts related to differentially methylated genes (DMGs) and methylation tools [5]. This continuously updated database incorporates normal human cell type DNA methylation datasets and contains methylation profiles for Homo sapiens, Arabidopsis thaliana, and other model organisms [5]. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) represents another essential resource, providing DNA methylation profiles for over 50 cancer types acquired from the Infinium HumanMethylation450K BeadChip platform, with each profile including methylation levels (β-values) for approximately 480,000 CpG probes [3].

For gene ontology analysis and functional annotation, resources such as the Gene Ontology database, DisGeNet, and OMIM provide valuable information for linking methylation changes to biological processes and disease associations [3]. Analytical toolkits like the Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline (ChAMP) facilitate quality control, normalization, and differential methylation analysis of array-based data, incorporating BMIQ normalization procedures to correct probe design biases [3]. Primer design for methylation-specific PCR benefits from specialized tools such as MethPrimer, while the BiSearch web server offers additional capabilities for designing bisulfite-conversion-based assays [2].

Essential Research Reagents and Kits

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Methylation Analysis

| Reagent/Kits | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K | Digests proteins and nucleases during DNA extraction | Critical for removing contaminating proteins; From Tritirachium album Limber [2] |

| Sodium Bisulfite | Converts unmethylated cytosine to uracil | Distinguishes methylated vs unmethylated cytosines; Critical parameter optimization required [2] |

| DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs) | Catalyzes methylation using SAM donor | For controlled methylation experiments; DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B have distinct functions [1] |

| Anti-methylcytosine antibody | Immunoprecipitation of methylated DNA | Used in MeDIP protocols; specificity validation essential [2] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Standardized bisulfite treatment | Commercial kits available from multiple vendors; performance varies [2] |

| Methylation-Specific Restriction Enzymes | Differential digestion based on methylation status | Used in HELP, MSRE and other restriction-based approaches |

| PCR Reagents | Amplification of bisulfite-converted DNA | Polymerase selection critical for bias-free amplification of converted templates [2] |

| DNA Quality Assessment Kits | UV spectrophotometry, fluorometry | A260/A280 ratios ~1.8 indicate pure DNA; quality critical for bisulfite conversion [2] |

DNA methylation represents a crucial regulatory mechanism that shapes development and contributes to disease etiology through stable alterations of gene expression potential. The technical advances in methylation analysis, from global mass spectrometry-based approaches to targeted bisulfite sequencing, have enabled precise mapping of epigenetic patterns across biological contexts. The integration of methylation data with comorbidity patterns and functional annotations, as demonstrated in the identification of ALX3, NPTX2, and TRIM58 as multi-cancer biomarkers, highlights the translational potential of epigenetic research [3]. As databases such as MethBank continue to expand with additional samples and cancer-specific modules, the research community gains increasingly powerful resources for epigenetic discovery [5].

The future of DNA methylation research lies in integrating multi-omics approaches to understand the interplay between epigenetic marks, genetic variants, and transcriptomic outputs across developmental trajectories and disease processes. Methodological innovations in long-read sequencing, single-cell epigenomics, and computational prediction will further enhance our ability to decipher the epigenetic code. For researchers and drug development professionals, DNA methylation analysis offers not only biomarkers for early detection but also potential targets for epigenetic therapies that may eventually reverse pathological epigenetic states, representing a promising frontier for precision medicine across cancer and complex diseases.

CpG Islands, Promoters, and Genomic Distribution Patterns

CpG islands (CGIs) are fundamental cis-regulatory elements in vertebrate genomes, characterized as contiguous, non-methylated segments with a significantly higher than average level of CpG dinucleotides and GC content [6]. The standard formal definition specifies a region of at least 200 base pairs (bp), with a GC percentage greater than 50%, and an observed-to-expected CpG ratio exceeding 60% [7]. These sequences stand in stark contrast to the general genomic landscape, where CpG dinucleotides are markedly underrepresented due to the elevated mutation rate of methylated cytosines, which spontaneously deaminate to thymines [7]. In mammalian genomes, approximately 70–80% of CpG dinucleotides are methylated, but CpG islands remain refractory to this modification [6].

The genomic distribution of CpG islands is highly non-random and strongly associated with gene regulatory regions. It is estimated that the human genome contains approximately 28,890 CpG islands [7]. A substantial majority of mammalian gene promoters are encompassed within these regions, with about 70% of proximal promoters (those located near the transcription start site) containing a CpG island [7]. This association extends beyond housekeeping genes to include many tissue-specific genes, challenging the initial perception that CpG island promoters were exclusively a feature of constitutive gene expression [6]. Furthermore, over 60% of human genes and almost all house-keeping genes have their promoters embedded in CpG islands, highlighting their central role in transcriptional regulation [7].

Table 1: Quantitative Characteristics of CpG Islands in the Human Genome

| Feature | Metric | Genomic Background |

|---|---|---|

| Formal Definition | ≥200 bp length, >50% GC content, >0.6 Observed/Expected CpG ratio | - |

| Estimated Count | ~28,890 islands | - |

| CpG Dinucleotide Frequency | ~4-6% (High,接近预期值) | ~1% (Suppressed) |

| Typical Methylation Status | Mostly unmethylated in normal cells | ~70-80% of CpGs methylated |

| Promoter Association | ~70% of proximal promoters; >60% of all human genes | - |

The functional relationship between CpG islands and promoters is complex and multifaceted. Unlike classical TATA box-containing promoters, CpG island promoters generally utilize dispersed transcription start sites, suggesting that the CpG island may act as a generalized platform for transcriptional initiation [6]. The methylation status of CpG islands within promoters is a critical determinant of gene activity, with hypermethylation typically leading to stable gene silencing—a mechanism frequently exploited in cancer cells to turn off tumor suppressor genes [7].

Characteristics and Genomic Distribution Patterns

The distribution of CpG islands across the genome follows distinct patterns that provide insights into their functional significance. These regions typically span 300–3,000 base pairs in length and are disproportionately located at or near transcription start sites of genes [7]. A key characteristic of CpG islands is their resistance to the CG suppression observed in the rest of the genome, maintaining a CpG dinucleotide content of at least 60% of that which would be statistically expected (approximately 4–6%), compared to the ~1% frequency in the genomic background [7].

Advanced genomic analyses have revealed finer distribution patterns, leading to a revised understanding of CpG island characteristics. An extensive study of human chromosomes 21 and 22 suggested that DNA regions greater than 500 bp with a GC content exceeding 55% and an observed-to-expected CpG ratio of 65% are more likely to represent "true" CpG islands associated with the 5' regions of genes [7]. This refinement helps distinguish promoter-associated CpG islands from other GC-rich genomic sequences such as Alu repeats. Interestingly, most tissue-specific methylation differences occur not in the CpG islands themselves, but in flanking regions termed "CpG island shores," located up to 2 kilobases away from the traditional island boundaries [7].

The genomic distribution of CpG islands is not uniform across all gene types. Based on CpG density variation, CpG islands can be classified into high-CpG (HCGI), intermediate-CpG (ICGI), and low-CpG (LCGI) density categories [8]. This classification has functional implications, as HCGI-associated genes are most likely to be housekeeping genes, while different HCGI/TATA-box combinations show distinct Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment patterns [8]. The HCGI/TATA± and LCGI/TATA± combinations display different GO enrichment profiles, whereas the ICGI/TATA± combination is less characteristic based on GO enrichment analysis [8].

Table 2: Classification of CpG Islands by Density and Functional Associations

| Classification | CpG Density | Common Gene Associations | Functional Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-CpG (HCGI) | Very High | Housekeeping (HK) genes | Strong, constitutive expression; distinct GO enrichment with TATA-box combinations |

| Intermediate-CpG (ICGI) | Moderate | Mixed | Less characteristic GO enrichment with TATA-box combinations |

| Low-CpG (LCGI) | Lower but still significant | Tissue-specific genes | Distinct GO enrichment patterns with TATA-box combinations |

The positioning of CpG islands within gene structures extends beyond proximal promoters. Distal promoter elements also frequently contain CpG islands, as exemplified by the DNA repair gene ERCC1, where a CpG island-containing element is located about 5,400 nucleotides upstream of the transcription start site [7]. Additionally, CpG islands occur frequently in promoters for functional noncoding RNAs, including microRNAs, expanding their regulatory influence beyond protein-coding genes [7].

Functional Mechanisms and Regulatory Roles

The functional role of CpG islands in gene regulation is mediated through sophisticated mechanisms involving specialized protein domains and chromatin modifications. Central to this process are ZF-CxxC domain-containing proteins, which specifically recognize and bind to non-methylated CpG dinucleotides [6]. This domain acts as a CpG island targeting module, with proteins like KDM2A and CFP1 binding to over 90% of CpG islands genome-wide [6]. The recognition is highly specific, as binding is blocked when the CpG sequence is methylated, providing a direct mechanism for interpreting the epigenetic information encoded in the methylation pattern.

These ZF-CxxC domain proteins are associated with histone-modifying activities that create a unique chromatin architecture characteristic of CpG islands. KDM2A catalyzes the removal of methylation from histone H3 lysine 36 (H3K36me2), leading to depletion of this mark at CpG islands [6]. Conversely, CFP1 associates with a histone H3 K4 methyltransferase complex (SET1 complex) to catalyze the addition of the tri-methyl modification (H3K4me3) [6]. The resulting chromatin environment—depleted of H3K36me2 and enriched with H3K4me3—effectively differentiates CpG island elements from surrounding chromatin and creates a configuration that is highly permissive for transcriptional initiation.

The following diagram illustrates how non-methylated CpG islands are recognized and translated into a unique chromatin architecture:

This chromatin architecture establishes what can be considered a default "permissive state" for transcription. In this state, RNA polymerase II is enriched at promoters, and short bidirectional transcripts are often produced, even from genes that show no detectable full-length mRNA [6]. This suggests that CpG island chromatin creates an accessible environment that favors binding of the basal transcription machinery. However, transition to a fully active state characterized by productive, directional transcription requires additional regulatory signals from sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factors [6]. The permissive state may function to highlight promoter regions within the vast expanse of the mammalian genome and focus nucleation of the transcriptional machinery at the 5' ends of genes.

The regulatory impact of CpG island methylation is profound, particularly in the context of disease states. Methylation of CpG islands in promoter regions leads to stable, long-term gene silencing [7]. In cancer, promoter CpG island hypermethylation represents a major mechanism for loss of tumor suppressor gene expression, occurring approximately 10 times more frequently than inactivating mutations [7]. For example, in colorectal cancer, hundreds to over a thousand genes may show aberrant promoter methylation compared to normal adjacent mucosa, illustrating the massive epigenetic disruption in malignancy [7].

Analytical Methods and Experimental Protocols

The analysis of CpG island methylation employs diverse methodological approaches, ranging from targeted assays to genome-wide profiling techniques. These methods can be broadly categorized into bisulfite sequencing-based methods, array-based platforms, and enrichment-based techniques, each with distinct applications, advantages, and limitations [9]. The selection of an appropriate method depends on the specific research question, required resolution, scale of analysis, and available resources.

Bisulfite Sequencing Methods

Bisulfite treatment represents the gold standard for DNA methylation analysis, converting unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines during sequencing) while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged [9]. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) provides comprehensive, single-base resolution methylation maps across the entire genome [10]. However, WGBS is costly and computationally intensive for large genomes. Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) offers a more cost-effective alternative by using restriction enzymes to enrich for CpG-rich regions prior to bisulfite treatment and sequencing [11]. RRBS covers approximately 1% of the total DNA methylome but captures about 30% of all CpG sites and 65% of promoter CpGs, making it highly efficient for analyzing CpG islands [11].

A typical RRBS protocol involves the following key steps [11]:

- DNA Digestion: 5 μg of genomic DNA is digested with the MspI restriction enzyme, which cuts at CCGG sites, effectively enriching for CpG-rich genomic regions.

- Library Preparation: The digested DNA fragments undergo end repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation using standard library preparation kits.

- Bisulfite Conversion: The adapter-ligated library is treated with bisulfite using commercial kits (e.g., EpiTect Bisulfite Kit), converting unmethylated cytosines to uracils.

- PCR Amplification: The bisulfite-converted DNA is amplified using a low number of PCR cycles (e.g., 4 cycles) with polymerases suitable for bisulfite-converted templates.

- Sequencing and Analysis: The final library is sequenced on platforms such as Illumina HiSeq, and the resulting data are processed using specialized alignment and methylation calling software.

Array-Based Platforms and Emerging Methods

For human studies, Illumina's Infinium Methylation BeadChip arrays (450K and EPIC) provide a cost-effective solution for profiling methylation at predetermined CpG sites. The EPIC array covers over 850,000 CpG sites, including more than 90% of the CpG islands from the 450K array with enhanced coverage of regulatory regions [3]. The standard analytical workflow for array data includes quality control, normalization, and differential methylation analysis using packages such as ChAMP, minfi, or RnBeads [12] [3].

Emerging computational approaches demonstrate that methylation status can be predicted from ordinary whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data by analyzing read distribution biases. This method, implemented in tools like WGS2meth, leverages the finding that methylated CpG dinucleotides are approximately 30% more susceptible to fragmentation during library preparation than unmethylated CpGs [10]. The workflow involves:

- Read Coordinate Extraction: Mapping 5'-end coordinates of reads and identifying the dinucleotide at each breakpoint.

- Dinucleotide Frequency Calculation: Measuring the observed versus expected fragmentation rates for each dinucleotide type in CpG islands.

- Machine Learning Classification: Using trained models (e.g., XGBoost) to predict methylation status based on the fragmentation bias patterns [10].

Table 3: Key Experimental Methods for CpG Island Methylation Analysis

| Method | Resolution | Throughput | Key Applications | Common Tools/Pipelines |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | Genome-wide | Comprehensive methylation mapping; novel discovery | Bismark, BS-Seeker, MethylKit [12] |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Single-base (CpG-rich regions) | Targeted (~1% of genome) | Cost-effective profiling of promoter regions | Trim Galore, Bismark, MethylKit [11] |

| Illumina Infinium BeadChip | Single CpG site (850K sites) | High-throughput population studies | EWAS; biomarker validation | ChAMP, minfi, RnBeads [12] [3] |

| Computational Prediction (from WGS) | CpG island level | Genome-wide | Methylation status from existing WGS data | WGS2meth [10] |

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps in a comprehensive CpG island methylation analysis, integrating both experimental and computational approaches:

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Advancing research in CpG island biology requires a comprehensive toolkit of specialized reagents, assays, and computational resources. These tools enable researchers to profile methylation patterns, manipulate methylation states, and interpret the resulting data in a biological context. The field has developed robust pipelines and databases that facilitate standardized analysis and integration with other genomic data types.

Essential Research Reagents and Assays

Key experimental reagents form the foundation of CpG island methylation research. Bisulfite conversion kits, such as the EpiTect Bisulfite Kit, are essential for most sequencing-based methods, enabling the discrimination between methylated and unmethylated cytosines [11]. Restriction enzymes like MspI are critical for RRBS protocols, providing selective enrichment of CpG-rich regions while reducing sequencing costs and complexity [11]. For array-based approaches, the Infinium HumanMethylation450K and EPIC BeadChip arrays (Illumina) offer standardized platforms for profiling over 850,000 CpG sites across the genome, with extensive coverage of CpG islands and regulatory regions [3]. Antibodies specific to 5-methylcytosine enable enrichment-based methods such as MeDIP-seq (Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing), which is particularly useful when working with limited DNA input or when bisulfite conversion is undesirable [12].

Bioinformatics Tools and Databases

The analysis of DNA methylation data relies heavily on specialized bioinformatics tools and pipelines. For bisulfite sequencing data, packages like DMRichR and methylKit provide comprehensive solutions for identifying differentially methylated regions (DMRs) from whole-genome bisulfite sequencing data [12]. The Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline (ChAMP) offers a complete analysis suite for Illumina Infinium array data, including quality control, normalization, and DMR detection [3]. Integration of methylation data with other omics datasets can be achieved using tools like FEM and ELMER, which correlate methylation patterns with gene expression to identify putative regulatory relationships [12].

For functional interpretation, enrichment analysis tools such as GOfuncR and GREAT provide biological context by associating methylation changes with Gene Ontology terms, pathways, and regulatory annotations [12]. The Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool (GREAT) is particularly valuable for analyzing genomic coordinates from methylation studies, as it assigns biological meaning to non-coding regions by analyzing annotations of nearby genes [12].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for CpG Island Analysis

| Category | Item | Specific Function | Example Tools/Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents & Kits | Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Converts unmethylated C to U for sequence discrimination | EpiTect Bisulfite Kit [11] |

| Restriction Enzymes | Enriches CpG-rich regions for targeted approaches | MspI (for RRBS) [11] | |

| Methylation Arrays | Genome-wide profiling of predefined CpG sites | Infinium Methylation450K/EPIC BeadChip [3] | |

| Computational Tools & Pipelines | Bisulfite Seq Analysis | Alignment, methylation calling, DMR detection from WGBS/RRBS | DMRichR, methylKit, Bismark [12] |

| Methylation Array Analysis | Quality control, normalization, DMR detection from array data | ChAMP, minfi, RnBeads [12] [3] | |

| Integrative Analysis | Correlates DNA methylation with gene expression data | FEM, ELMER [12] | |

| Functional Interpretation | Enrichment Analysis | Provides biological context (GO, pathways) for gene lists | GOfuncR, GREAT, Enrichr [12] |

Applications in Disease Research and Biomarker Discovery

The analysis of CpG island methylation patterns has profound implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing clinical biomarkers. In cancer research, DNA methylation profiling has revealed extensive reprogramming of the epigenome, with specific methylation signatures associated with diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment response. Cancers with low five-year survival rates—including pancreatic (10%), esophageal (20%), liver (20%), lung (21%), and brain (27%) cancers—have been particularly targeted for methylation biomarker discovery [3].

Integrated analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles and comorbidity patterns across these five cancer types has identified key methylation biomarkers, including ALX3, HOXD8, IRX1, HOXA9, HRH1, PTPRN2, TRIM58, and NPTX2 [3]. The combination of ALX3, NPTX2, and TRIM58—selected from distinct functional groups through gene ontology clustering—achieved 93.3% accuracy in predicting cancer status across the ten most common cancers, demonstrating the power of multi-functional biomarker panels [3]. This approach combines primary biomarkers identified through differential methylation analysis (comparing tumor vs. normal tissue, with |Δβ-value| > 0.2 and p < 0.05) with secondary biomarkers derived from comorbidity-associated genes, creating robust diagnostic signatures.

In basic research, studies examining the relationship between CpG island methylation and gene expression across diverse adult tissues have provided insights into the fundamental principles of epigenetic regulation. Analysis of 20 pairs of DNA methylomes and transcriptomes from adult Ogye chicken tissues identified 3,133 CpG islands potentially affecting downstream genes [11]. Among these, 121 significant CpG island-gene pairs showed statistically correlated expression, with six genes (CLDN3, DECR2, EVA1B, NME4, NTSR1, and XPNPEP2) demonstrating highly significant changes associated with DNA methylation alterations [11]. These findings confirm that DNA methylation levels and gene expression are generally negatively correlated in normal adult tissues, with important tissue-specific variations.

The translational potential of CpG island methylation analysis extends to early cancer detection, monitoring disease progression, and predicting treatment response. The stability of DNA methylation marks in circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) makes them particularly attractive as non-invasive biomarkers [10]. Furthermore, the distinct fragmentation patterns of methylated DNA in cfDNA—where fragments more frequently begin with CpG dinucleotides when those CpGs are methylated—provide an additional layer of information that can be leveraged with machine learning approaches [10]. These advances highlight the growing importance of CpG island methylation analysis in both basic research and clinical applications, offering powerful tools for understanding gene regulation and developing epigenetic-based diagnostics and therapies.

DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs) and Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) Enzymes in Methylation Dynamics

DNA methylation and demethylation constitute a dynamic epigenetic layer crucial for regulating gene expression, genomic stability, and cellular differentiation. This balance is orchestrated by the opposing activities of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) dioxygenases. DNMTs establish and maintain cytosine methylation, while TET enzymes catalyze its iterative oxidation, initiating active demethylation pathways. This technical guide delves into the structure, function, and regulatory mechanisms of these enzyme families, underscoring their roles in mammalian development and disease pathogenesis, particularly cancer. Furthermore, it provides a comprehensive overview of modern analytical methodologies and computational tools, framing this knowledge within the context of resources for DNA methylation research.

DNA methylation, the covalent addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of cytosine (5-methylcytosine, 5mC), primarily within cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, is a fundamental epigenetic mark in mammals [13] [14]. This modification is dynamically regulated and influences cellular processes including transcriptional repression, X-chromosome inactivation, genomic imprinting, and suppression of transposable elements [13] [15]. The mammalian "methylome" is not static; it is maintained by a delicate equilibrium between methylation, catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), and active demethylation, facilitated by Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) dioxygenases [14]. Disruption of this balance is a hallmark of various human diseases, most notably cancer, which often exhibits global hypomethylation coupled with site-specific hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters [13] [16]. Understanding the enzymes governing this cycle is therefore paramount for both basic research and therapeutic development.

DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs): Architects of Methylation

Enzyme Types and Functional Roles

The DNMT family in mammals comprises three canonical, catalytically active enzymes: DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, alongside regulatory factors like DNMT3L [14] [17].

- DNMT1 is often termed the "maintenance" methyltransferase. It exhibits a strong preference for hemi-methylated DNA, making it essential for copying DNA methylation patterns from the parent strand to the newly synthesized daughter strand during DNA replication, thereby ensuring the fidelity of epigenetic inheritance across cell divisions [14] [15].

- DNMT3A and DNMT3B are responsible for de novo methylation, targeting unmethylated CpG sites to establish new methylation patterns during embryonic development and gametogenesis [13] [14]. Despite their primary role, they also contribute to methylation maintenance in specific contexts [14].

- DNMT3L is a catalytically inactive paralog that stimulates the activity of DNMT3A and DNMT3B by forming a complex with them, enhancing their binding affinity for DNA [14] [17].

Structure and Catalytic Mechanism

All catalytically active DNMTs share a common catalytic mechanism. They utilize S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) as the methyl group donor [14]. The enzyme catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group to the C5 position of cytosine, resulting in the formation of 5mC and S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH). A key step in this reaction involves the enzyme flipping the target cytosine base out of the DNA helix and into its catalytic pocket, a process critical for the modification to occur [17].

Table 1: Core DNA Methyltransferases in Mammals

| Enzyme | Primary Role | Key Structural Features | Associated Human Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance methylation | N-terminal regulatory domain, C-terminal catalytic domain [14] | Hereditary sensory autonomic neuropathy, Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, Breast Cancer [14] |

| DNMT3A | De novo methylation | PWWP domain, ADD domain, C-terminal catalytic domain [14] | Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Tatton–Brown–Rahman syndrome [14] |

| DNMT3B | De novo methylation | PWWP domain, ADD domain, C-terminal catalytic domain [14] | Immunodeficiency, Centromere instability, and Facial anomalies (ICF) syndrome [14] |

| DNMT3L | Regulation of DNMT3A/B | Lacks catalytic activity, forms heterotetramers with DNMT3A [14] [17] | - |

Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) Enzymes: Catalysts of Demethylation

Enzyme Family and Oxidative Function

The TET family of proteins, comprising TET1, TET2, and TET3, are Fe(II)/α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)-dependent dioxygenases that initiate active DNA demethylation [18] [19]. They catalyze the sequential oxidation of 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), then to 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and finally to 5-carboxycytosine (5caC) [18] [16]. The 5hmC mark is not merely an intermediate; it also serves as a stable epigenetic mark with distinct regulatory functions, particularly abundant in embryonic stem cells and neuronal tissues [18] [16].

Pathways to DNA Demethylation

TET-mediated oxidation leads to demethylation via two principal pathways:

- Active Demethylation: The oxidized bases 5fC and 5caC are recognized and excised by thymine-DNA glycosylase (TDG). The resulting abasic site is then restored to an unmethylated cytosine through the Base Excision Repair (BER) pathway [18] [14].

- Passive Demethylation: The presence of 5hmC (and further oxidized derivatives) impairs the ability of DNMT1 to recognize and methylate the cytosine on the newly synthesized DNA strand during replication. This leads to a dilution of the methylation mark over subsequent cell divisions [18] [16].

Structural Insights and Regulatory Diversity

All TET proteins contain a conserved C-terminal catalytic domain that includes a double-stranded β-helix (DSBH) fold and a cysteine-rich domain, which together coordinate the Fe(II) and α-KG cofactors [18] [19]. A key structural difference lies in the N-terminus: TET1 and TET3 possess a CXXC zinc finger domain that binds unmethylated CpG-rich DNA, whereas TET2 lacks this domain. The CXXC domain of TET2 exists as a separate gene, IDAX (CXXC4), which regulates TET2 activity and recruitment [18] [19]. Furthermore, each TET gene expresses multiple isoforms through alternative splicing and promoter usage, adding a layer of regulatory complexity and tissue-specific function [19].

Table 2: The TET Enzyme Family

| Enzyme | Key Domains | Oxidation Products | Genomic Preference | Role in Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TET1 | CXXC, Catalytic Domain | 5hmC, 5fC, 5caC [18] | Promoters [18] | - |

| TET2 | Catalytic Domain | 5hmC, 5fC, 5caC [18] | Gene bodies, Enhancers [18] | Frequently mutated in myeloid malignancies [18] [16] |

| TET3 | CXXC, Catalytic Domain | 5hmC, 5fC, 5caC [18] | - | - |

The Methylation Cycle: An Integrated View

The following diagram illustrates the integrated cycle of DNA methylation and demethylation, highlighting the central roles of DNMT and TET enzymes.

Analytical Methods for DNA Methylation Research

Selecting the appropriate method for DNA methylation analysis is critical and depends on the research question, required resolution, and available resources [20] [21].

Core Techniques Based on Bisulfite Conversion

Treatment of DNA with sodium bisulfite deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils, which are then converted to thymidines during PCR amplification, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. This sequence conversion forms the basis of many gold-standard methods [20].

- Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS): This is the most comprehensive method, providing single-base resolution methylation status for nearly all cytosines in the genome. It is ideal for discovery-based studies but is costly and computationally intensive [20].

- Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS): This method uses restriction enzymes to digest genomic DNA, enriching for CpG-dense regions (e.g., promoters and CpG islands) before bisulfite treatment and sequencing. It is more cost-effective than WGBS for focused analyses [20].

- Methylation-Specific PCR (MS-PCR): After bisulfite conversion, PCR primers are designed to specifically amplify either the methylated or unmethylated sequence. This is a simple, qualitative method for assessing the methylation status of a specific gene region [20].

- Bisulfite Pyrosequencing: This is a quantitative method that analyzes a short sequence of DNA following bisulfite PCR. It provides highly accurate, base-resolution quantification of methylation levels at consecutive CpG sites and is widely used for validation studies [21].

Global Methylation Analysis

For assessing genome-wide methylation levels, techniques like HPLC-UV (the gold standard) and the more sensitive LC-MS/MS can precisely quantify the total levels of 5mC and 5hmC in hydrolyzed DNA samples [21]. ELISA-based methods offer a rapid, albeit less accurate, alternative for global methylation screening [21].

Table 3: Key Methods for DNA Methylation Analysis

| Method | Resolution | Throughput | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGBS | Single-base | High | Comprehensive genome coverage [20] | High cost, complex data analysis [20] |

| RRBS | Single-base | High | Cost-effective for CpG-rich regions [20] | Limited to a fraction of the genome [20] |

| Bisulfite Pyrosequencing | Quantitative, single-base | Medium | High accuracy and quantitative precision [21] | Limited to short, predefined sequences [21] |

| MS-PCR | Locus-specific | Low | Simple, accessible, no sequencing required [20] | Qualitative or semi-quantitative only [20] |

| LC-MS/MS | Global (total 5mC/5hmC) | Low | High sensitivity and accuracy [21] | Requires specialized, expensive equipment [21] |

| ELISA | Global | High | Very fast and simple [21] | Low accuracy and high variability [21] |

Experimental Workflow: From Sample to Analysis

A typical workflow for a genome-wide DNA methylation study using bisulfite sequencing is outlined below and visualized in the accompanying diagram.

Detailed Protocol: Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS)

- DNA Extraction & Quality Control: High-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA is isolated from cells or tissue. Quality and quantity are assessed using spectrophotometry or fluorometry [20].

- Library Preparation & Bisulfite Conversion: The DNA is fragmented (e.g., by sonication) and adapters are ligated to the ends. The library is then treated with sodium bisulfite, which deaminates unmethylated C to U, leaving 5mC and 5hmC unchanged [20]. The converted DNA is purified to remove reagents.

- PCR Amplification: The bisulfite-converted DNA library is amplified using a DNA polymerase that is efficient at amplifying uracil-containing templates [20].

- High-Throughput Sequencing: The final library is sequenced on a next-generation sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina), generating millions of short reads [20].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment: Reads are aligned to a reference genome using specialized bisulfite-aware aligners (e.g., Bismark [12]), which account for the C-to-T conversion.

- Methylation Calling: The methylation status of each cytosine is determined by comparing the sequencing read to the reference genome. A C in the read that aligns to a C in the reference indicates a methylated cytosine, while a T indicates an unmethylated one [20].

- Differential Methylation Analysis: Statistical packages (e.g.,

dmrseq[12]) are used to identify genomic regions that show significant differences in methylation levels between sample groups.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Kits for DNA Methylation Analysis

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosine to uracil [20] | Fundamental reagent for bisulfite-based methods (WGBS, RRBS, MSP) [20] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Commercial kits for efficient and controlled bisulfite conversion and cleanup (e.g., from Zymo Research, Qiagen) [21] | Standardizing the critical conversion step for reproducibility |

| Anti-5mC / Anti-5hmC Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation or immuno-detection of modified cytosines [16] | MeDIP-seq, hMeDIP-seq, ELISA-based global quantification [21] |

| DNMT/TET Inhibitors | Small molecules to modulate enzyme activity (e.g., Decitabine, AZA) [15] | Functional studies to probe the role of DNA methylation in cellular processes |

| LC-MS/MS System | High-sensitivity quantification of nucleosides (dC, 5mC, 5hmC) [21] | Gold-standard measurement of global DNA methylation/hydroxymethylation levels |

Bioinformatics Tools and Databases

A robust bioinformatics pipeline is indispensable for interpreting methylation data. Key resources include:

- Alignment & QC:

Bismarkis a widely used tool for aligning bisulfite sequencing reads and performing methylation extraction [12].CpG_Meis a pipeline for WGBS alignment and quality control [12]. - Differential Methylation Analysis:

DMRichRis an R package for identifying and visualizing differentially methylated regions (DMRs) from whole-genome data [12].methylKitandRnBeadsare comprehensive R packages for analyzing bisulfite sequencing and microarray data, respectively [12]. - Annotation and Visualization:

GREATassigns biological meaning to non-coding genomic regions by analyzing nearby gene annotations [12].WandererandMethylation plotterare interactive tools for visualizing methylation data in genomic contexts [12]. - Public Data Repositories: Databases such as the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) host vast amounts of publicly available DNA methylation data for comparative and meta-analysis.

DNMT and TET enzymes form a sophisticated, dynamic system for the precise control of the DNA methylome. Their integrated activity is fundamental to normal development and cellular function, and its dysregulation is a key driver of disease, particularly in cancer. Contemporary research, powered by high-throughput sequencing technologies and a growing suite of bioinformatic tools, continues to unravel the complexity of this regulatory network. This guide provides a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals, equipping them with the knowledge of core principles, experimental methodologies, and analytical resources needed to advance the field of epigenetic research and therapeutics.

Key Biological Processes Regulated by DNA Methylation

DNA methylation is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism involving the addition of a methyl group to a DNA molecule, typically at the fifth carbon of a cytosine residue to form 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) [22] [23]. This modification regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence and is essential for normal development, cellular differentiation, and genomic stability [23]. In mammals, DNA methylation occurs primarily at CpG dinucleotides—regions where a cytosine is followed by a guanine [22] [24]. The distribution of CpG sites is not uniform across the genome; they are often clustered in regions known as CpG islands, which are frequently located in gene promoter regions [23] [24]. This technical guide details the key biological processes governed by DNA methylation, provides methodologies for its measurement, and outlines essential resources for research, serving as a foundational resource for scientists and drug development professionals engaged in epigenetics research.

Core Mechanisms and Functional Impact

DNA methylation dynamics are governed by dedicated enzymes and have a direct mechanistic impact on gene transcription.

The DNA Methylation and Demethylation Machinery

The establishment, maintenance, and removal of DNA methylation marks are catalyzed by specific enzymes [22] [25]:

- De Novo Methyltransferases (DNMT3A & DNMT3B): These enzymes establish new methylation patterns on previously unmodified DNA [22] [23].

- Maintenance Methyltransferase (DNMT1): This enzyme copies the methylation pattern from the parent DNA strand to the daughter strand during DNA replication, ensuring the methylation landscape is propagated through cell divisions [22] [23].

- Demethylation Pathways: DNA demethylation can occur passively when methylation patterns are not maintained during replication. Active demethylation involves the Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) family of enzymes, which oxidize 5-mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC), initiating a pathway that leads to the restoration of an unmodified cytosine [22] [23].

How Methylation Regulates Transcription

The presence of 5-mC in gene promoter regions typically leads to transcriptional repression through two primary mechanisms [22] [24]:

- Direct Obstruction: The methyl group can physically impede the binding of transcription factors to their target DNA sequences.

- Recruitment of Repressor Complexes: Methylated DNA is recognized by methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins (MBDs), such as MeCP2. These proteins then recruit additional chromatin-modifying complexes, including histone deacetylases, which lead to a more condensed, transcriptionally inactive chromatin state known as heterochromatin [22] [24].

Table 1: Enzymatic Regulators of DNA Methylation

| Enzyme/Protein | Type | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | DNA Methyltransferase | Maintenance Methylation | Copies methylation pattern during DNA replication; ensures heritability of epigenetic marks [22] [23]. |

| DNMT3A & DNMT3B | DNA Methyltransferase | De Novo Methylation | Establishes new methylation patterns during embryonic development and cellular differentiation [22] [23]. |

| TET Family | Dioxygenase | Active Demethylation | Initiates demethylation by oxidizing 5-mC to 5-hmC; crucial for dynamic methylation control in neurons and stem cells [22] [23]. |

| MeCP2 | Methyl-Binding Domain Protein | Transcription Repression | Binds methylated CpGs and recruits histone modifiers to silence gene expression [22] [24]. |

Key Biological Processes Regulated by DNA Methylation

DNA methylation is indispensable for several critical biological processes, with dysregulation being a hallmark of many diseases.

Cellular Differentiation and Embryonic Development

During mammalian embryonic development, the genome undergoes widespread epigenetic reprogramming [24]. Global DNA methylation patterns are largely erased and then re-established in a cell- and tissue-specific manner [23]. This process allows pluripotent stem cells to differentiate into the diverse array of cell types that constitute an organism. DNA methylation helps define and lock in cell identity by stably silencing genes that are unnecessary for a specific cell lineage [22] [23].

Genomic Imprinting

Genomic imprinting is an epigenetic phenomenon that results in the monoallelic expression of a subset of genes based on their parental origin. DNA methylation marks at imprinting control regions (ICRs) are established in the parental germlines and maintained throughout development to ensure that only one allele (either the maternal or paternal) is active [22] [24]. This process is critical for normal growth and development.

X-Chromosome Inactivation

In female mammals, one of the two X chromosomes is transcriptionally silenced to achieve dosage compensation with males who have only one X chromosome. DNA methylation plays a crucial role in the stable maintenance of this silencing. The Xist RNA coats the future inactive X chromosome, leading to the recruitment of DNMTs and subsequent methylation of the promoter regions of genes on that chromosome, ensuring their long-term repression [22] [24].

Silencing of Repetitive Elements

A substantial portion of the mammalian genome consists of transposable elements and retroviral sequences. The pervasive methylation of these intergenic regions is critical for maintaining genomic stability by preventing the transcription and mobilization of these potentially harmful elements, which could cause mutations and DNA damage [23] [24].

Gene Body Methylation

Contrary to promoter methylation, methylation within the transcribed region of actively expressed genes (gene body methylation) is often associated with efficient transcription [24]. While its function is less understood, it is thought to suppress spurious transcription from cryptic start sites within the gene or to play a role in alternative splicing [24].

The following diagram illustrates how DNA methylation regulates gene silencing, a process central to many of these biological functions:

DNA Methylation in Human Disease

Aberrant DNA methylation patterns are a universal feature of many human diseases, particularly in cancer [22] [26].

Table 2: DNA Methylation Alterations in Human Disease

| Disease Category | Methylation Status | Key Genes/Regions Affected | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Global Hypomethylation | Repetitive Elements, Intergenic Regions | Genomic instability, activation of oncogenes [22]. |

| Promoter Hypermethylation | Tumor Suppressor Genes (e.g., BRCA1, MLH1) | Silencing of genes that control cell cycle, DNA repair, and apoptosis [22] [26]. | |

| Neurological Disorders | Hypermethylation | Alzheimer's disease-related genes | Repression of genes critical for neuronal function [22]. |

| Hypomethylation | SNCA (Alpha-synuclein) | Overexpression of SNCA, linked to Parkinson's disease pathology [22]. | |

| MeCP2 Mutation | MECP2 Gene | Rett syndrome; loss of function in reading DNA methylation marks [22]. | |

| Autoimmune Disease (e.g., SLE) | Global Hypomethylation | T-cell DNA | Promotes autoreactivity and inflammation [22]. |

Measurement and Analysis of DNA Methylation

Accurate measurement of DNA methylation is crucial for research and clinical applications. The choice of method depends on the research question, required resolution, and available resources [25].

Genome-Wide Profiling Techniques

- Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS): This is the gold standard for DNA methylation analysis, providing single-base resolution methylation levels across the entire genome [25] [26]. It involves treating DNA with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines in sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged [25].

- Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS): This method enriches for CpG-dense regions (like CpG islands) by using restriction enzymes, followed by bisulfite sequencing. It is a cost-effective alternative to WGBS that provides high-resolution data for key regulatory regions [25] [26].

- Methylation Arrays (e.g., Illumina Infinium): These arrays interrogate the methylation status of hundreds of thousands of pre-selected CpG sites. They are a high-throughput, cost-effective solution for large-scale epidemiological studies [27] [25].

A Protocol for Methylation Analysis in Cancer Biospecimens

The following workflow, adapted from a detailed protocol for processing human cancer biospecimens, outlines the key steps for generating high-quality genome-scale DNA methylation data using RRBS [26]:

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from biospecimens (e.g., fresh-frozen tissue, FFPE tissue, cell lines). For FFPE tissue, this includes a deparaffinization step and proteinase K digestion to reverse cross-links and recover DNA [26].

- Restriction Digestion: Digest DNA with the MspI restriction enzyme. This enzyme cuts at CCGG sites, which are abundant in CpG-rich regions, thereby creating a reduced representation of the genome [26].

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat the digested DNA with sodium bisulfite using a commercial kit (e.g., Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation-Direct Kit). This critical step converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils [25] [26].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare a sequencing library from the bisulfite-converted DNA. This involves end-repair, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. The library is then sequenced on an Illumina platform [26].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control & Trimming: Use tools like FastQC and Trim Galore to assess read quality and remove adapter sequences [26].

- Alignment: Align the processed reads to a bisulfite-converted reference genome using an aligner like Bismark [26].

- Methylation Calling: The same Bismark tool is used to extract the methylation status of each cytosine in the genome, comparing the sequenced bases to the reference to determine if they were methylated (C) or unmethylated (T post-conversion) [26].

- Differential Analysis: Use statistical packages in R or specialized tools like DMAP to identify regions of significant methylation difference between sample groups [26].

Successful DNA methylation research relies on a suite of specialized reagents, tools, and databases.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Methylation Analysis

| Item | Function | Example Products/Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Chemically converts unmethylated C to U; critical for bisulfite-based methods. | Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation-Direct Kit [26]. |

| Methylation-Sensitive Enzymes | Restriction enzymes used in methods like RRBS to enrich for CpG-rich regions. | MspI [26]. |

| DNA Methyltransferases (Recombinant) | For in vitro methylation assays and control experiments. | Commercial recombinant DNMT enzymes. |

| Methylated & Unmethylated Control DNA | Essential positive and negative controls for bisulfite conversion and assay validation. | Commercially available from various suppliers (e.g., Zymo Research). |

| Methylation Arrays | High-throughput profiling of pre-defined CpG sites. | Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC array [27] [28]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | For alignment, methylation calling, and differential analysis of sequencing data. | Bismark, FastQC, Trim Galore, DMAP, SAMtools [26]. |

| Public Databases | For exploring methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTLs) and reference data. | EPIGEN MeQTL Database [28]; Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). |

Connecting DNA Methylation to Transcriptional Regulation and Cellular Identity

DNA methylation, the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of cytosine, constitutes a fundamental epigenetic mechanism that dynamically regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [29]. This modification plays a pivotal role in determining mammalian cell development, lineage identity, and transcriptional programs, serving as a crucial interface between the genome and environmental influences [30]. In the immune system, for example, fine-tuned DNA methylation patterns control myeloid and lymphoid cell differentiation and function, shaping both innate and adaptive immune responses [30]. Dysregulation of these epigenetic controls leads to significant human pathology, including blood malignancies, infections, and autoimmune diseases [30]. This technical guide examines the molecular mechanisms connecting DNA methylation to transcriptional regulation, surveys cutting-edge profiling technologies, and explores how these mechanisms establish and maintain cellular identity across biological contexts.

Molecular Mechanisms of Methylation-Mediated Regulation

Canonical Transcriptional Repression

The predominant model of DNA methylation-mediated gene silencing involves multiple interconnected mechanisms that render chromatin inaccessible to transcriptional machinery. Methylation primarily occurs at CpG dinucleotides, with CpG-rich regions known as CpG islands frequently found at gene promoters [31]. When these promoters become methylated, the modification can directly prevent transcription factor binding by steric hindrance or by recruiting transcriptional repressor complexes [31] [29]. A key mechanism involves methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins (MBPs) such as MeCP2, which deck on methylated DNA and recruit co-repressor complexes including histone methyltransferases and histone deacetylases [29]. This collaboration between DNA methylation and histone modifications establishes an inactive chromatin state characterized by condensed nucleosomes that physically obstruct transcription factor accessibility [29].

Context-Dependent Regulatory Effects

Recent epigenome engineering approaches have revealed that transcriptional responses to DNA methylation are more complex and context-specific than previously appreciated. While promoter hypermethylation is common in cancer and frequently associated with tumor-suppressor gene silencing, some regulatory networks can override DNA methylation, and promoter methylation can sometimes cause alternative promoter usage rather than complete silencing [31]. Surprisingly, induced DNA methylation can exist simultaneously on promoter nucleosomes possessing the active histone modification H3K4me3 or DNA bound by the initiated form of RNA polymerase II [31]. In some cases, increased gene expression has been observed following methylation induction, potentially driven by the eviction of methyl-sensitive transcriptional repressors [31].

Genomic Distribution and Functional Consequences

The genomic context of DNA methylation significantly determines its functional impact. While promoter methylation typically correlates with gene silencing, gene body methylation has been associated with active transcription and may affect alternative intragenic promoters, enhancers, non-coding RNA expression, transposable element mobility, and alternative splicing or polyadenylation [29]. Intergenic methylation changes can affect enhancers or insulators, leading to gene silencing or activation, respectively [29]. This complex relationship is bidirectional, as certain transcription factors can place epigenetic marks upon binding to DNA and subsequently alter DNA methylation patterns [29].

Table 1: Functional Consequences of DNA Methylation by Genomic Context

| Genomic Context | Methylation State | Typical Effect | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter CpG Island | Hypermethylation | Gene silencing | Chromatin condensation, transcription factor exclusion |

| Gene Body | Methylation | Transcription elongation, splice regulation | Unknown, potentially affects histone modifications |

| Intergenic Enhancer | Hypermethylation | Enhancer silencing | Disrupted transcription factor binding |

| Imprinted DMRs | Allele-specific methylation | Parent-of-origin expression | Monoallelic transcriptional regulation |

| Repetitive Elements | Hypermethylation | Genomic stability | Transposon silencing |

Advanced Methodologies for Methylation Analysis

Sequencing-Based Profiling Technologies

Recent technological advances have revolutionized our capacity to profile DNA methylation patterns at various resolutions and scales. The table below compares key modern methodologies for methylation analysis.

Table 2: DNA Methylation Profiling Technologies and Applications

| Technology | Resolution | Throughput | Key Advantage | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | Genome-wide | Gold standard for base resolution | Comprehensive methylome mapping [32] |

| meCUT&RUN | Regional | Targeted | 20-fold fewer reads than WGBS; low input (10,000 cells) [33] | Efficient methylome profiling [33] |

| Spatial-DMT | Near single-cell | Spatial multi-omics | Simultaneous methylome and transcriptome on tissue section [34] | Tissue context methylation-transcription relationships [34] |

| Nanopore T-LRS | Single-molecule | Targeted (0.1-10% of genome) | Phasing of methylation haplotypes; no bisulfite conversion [35] | Imprinting disorders, allele-specific methylation [35] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Global quantification | N/A | Absolute quantification independent of sequence [4] | Global methylation levels; non-model organisms [4] |

Spatial Multi-Omics Integration

A groundbreaking advancement in methylation analysis is the recent development of spatial joint profiling of DNA methylome and transcriptome (spatial-DMT), which enables simultaneous measurement of both epigenetic and transcriptional states in intact tissue sections at near single-cell resolution [34]. This technology combines microfluidic in situ barcoding, cytosine deamination conversion, and high-throughput sequencing to map methylation patterns within the native tissue architecture [34]. Applied to mouse embryogenesis and postnatal mouse brains, spatial-DMT has revealed intricate spatiotemporal regulatory mechanisms, showing how methylation and transcription patterns collectively define cell identity during mammalian development [34]. This approach addresses the critical limitation of previous methods that lost spatial context, enabling researchers to investigate interactive molecular hierarchies in development, physiology, and pathogenesis with spatial resolution.

Long-Read Sequencing for Methylation Haplotyping

Single-molecule long-read sequencing technologies from Oxford Nanopore and Pacific Biosciences now enable simultaneous measurement of epigenetic states alongside genomic variation, providing phasing information that reveals allele-specific methylation patterns [32] [35]. These technologies have proven particularly valuable for studying imprinted genomic regions, which contain differentially methylated regions (DMRs) with parent-of-origin-specific 5-methylcytosine patterns that control monoallelic expression [35]. Targeted long-read sequencing using adaptive sampling enriches specific genomic regions, providing cost-effective methylation haplotyping that can distinguish paternal and maternal alleles without statistical inference [35]. This approach has been successfully applied to imprinting disorders such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, Silver-Russell syndrome, and Temple syndrome, where it can identify multi-locus imprinting disturbances and structural variants affecting methylation patterns [35].

Experimental Approaches for Functional Validation

Targeted Methylation Manipulation

Epigenome engineering techniques enable direct testing of causal relationships between induced DNA methylation and transcriptional outcomes. Targeted methylation approaches include customized zinc finger domains, transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs), or nuclease-inactive Cas9 fused to the catalytic domain of DNA methyltransferases like DNMT3A or bacterial methyltransferases such as M.SssI [31]. These tools allow researchers to deposit methylation at specific endogenous loci and assess the resulting effects on transcription, chromatin accessibility, and histone modifications. Large-scale manipulation of promoter methylation has revealed that transcriptional responses are highly context-specific, with some promoters resistant to methylation-induced silencing while others show strong repression [31]. Importantly, induced methylation at regulatory elements can be rapidly erased after removing the methyltransferase fusion protein, through processes combining passive dilution and TET-mediated active demethylation [31].

Integrative Analysis Workflows

Comprehensive analysis of methylation-dependent regulation requires integrated experimental designs that couple methylation profiling with complementary assays. The diagram below illustrates a workflow for simultaneous spatial profiling of DNA methylation and gene expression.

Spatial co-profiling workflow for simultaneous DNA methylome and transcriptome analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for DNA Methylation Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CUTANA meCUT&RUN Kit | Methylated DNA enrichment using engineered MeCP2 protein | Targeted methylome profiling with reduced sequencing depth [33] |

| ZF-DNMT3A/DNMT3B fusions | Targeted methylation deposition | Epigenome engineering to test methylation effects [31] |

| EM-seq Conversion Kit | Enzymatic bisulfite alternative | Preservation of DNA integrity during methylation detection [34] |

| DNA Ligation Sequencing Kit (ONT) | Library prep for nanopore sequencing | Long-read methylation haplotyping [35] |

| Infinium MethylationEPIC Kit | Array-based methylation screening | Cost-effective population epigenomics [3] |

| 3-Oxooctanoic acid | 3-Oxooctanoic acid|CAS 13283-91-5|For Research | 3-Oxooctanoic acid is a medium-chain keto acid for research. This product is for laboratory research use only (RUO) and not for human use. |

| Beryllium selenide | Beryllium selenide, CAS:12232-25-6, MF:BeSe, MW:87.98 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

DNA Methylation in Cellular Identity and Disease

Establishing and Maintaining Cellular Identity

DNA methylation serves as a fundamental mechanism for establishing and maintaining cellular identity throughout development and differentiation. During mammalian embryogenesis, carefully orchestrated methylation dynamics define lineage specification and tissue patterning, as revealed by spatial multi-omics approaches [34]. In the immune system, DNA methylation patterning precisely modulates cell type- and stimulus-specific transcriptional programs that preserve host defense and organ homeostasis [30]. The relationship between methylation and cellular identity is particularly evident in imprinted genes, which maintain parent-of-origin-specific expression through germline-derived methylation marks that are protected from genome-wide demethylation events after fertilization [35]. Maintenance of these identity-defining methylation patterns requires both faithful copying during DNA replication through DNMT1 and protection against unauthorized demethylation by factors like ZFP57 and ZNF445 [35].

Methylation Dysregulation in Human Disease