From Chromatin to Code: Validating Histone Marks with Gene Expression for Discovery and Disease

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating histone modification and gene expression data.

From Chromatin to Code: Validating Histone Marks with Gene Expression for Discovery and Disease

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating histone modification and gene expression data. It explores the foundational principles of histone mark biology, details state-of-the-art computational methods for model building and prediction, addresses common challenges in data integration and model interpretation, and outlines rigorous frameworks for the biological and clinical validation of findings. By synthesizing recent advances in machine learning and epigenomics, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to uncover new biological insights and translate epigenetic signatures into prognostic tools and therapeutic targets.

Decoding the Histone Language: Core Principles and Genomic Context

The "histone code" is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism wherein post-translational modifications to histone proteins provide regulatory information that extends beyond the DNA sequence itself. These modifications act as dynamic signaling modules, responding to metabolic and environmental cues to orchestrate chromatin structure and, consequently, gene expression [1]. This guide objectively compares the performance of four core histone marks—H3K4me3 and H3K27ac as activating marks, and H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 as repressive marks—in predicting transcriptional activity. The validation of these marks is critically framed within modern research that directly correlates their presence with gene expression data, providing life scientists and drug developers with a data-driven resource for epigenetic analysis.

The functional roles of these marks are often defined by their genomic context and combinatorial presence. Transposable elements (TEs), which constitute nearly half of the mammalian genome, are deeply embedded in this regulatory framework, frequently hosting these histone marks and contributing to tissue-specific gene regulation [2] [3]. The co-evolution of TEs and host DNA has significantly shaped the epigenetic landscape, making their role in the histone code an area of growing importance for understanding gene regulatory evolution.

Mark Definition and Genomic Distribution

Activating Histone Marks

H3K4me3 (Histone H3 Lysine 4 trimethylation)

- Primary Location: Sharp, narrow peaks (< 1 kb) flanking transcription start sites (TSSs), with a predominant peak at the end of the first exon [1].

- Function: Strongly associated with transcription initiation. It serves as a binding site for the TFIID complex subunit TAF3, facilitating recruitment of the pre-initiation complex [1]. A subset of genes, often those essential for cell identity and function, are marked by a broad H3K4me3 domain (> 4 kb) that extends into the gene body, forming a "broad epigenetic domain" [1].

H3K27ac (Histone H3 Lysine 27 acetylation)

- Primary Location: Active promoters and enhancers [4] [3].

- Function: Distinguishes active enhancers from their poised counterparts (which may bear H3K4me1 alone). H3K27ac recruits transcription factors, such as BRD4, which enhances RNA Polymerase II recruitment and increases transcription [5].

Repressive Histone Marks

H3K27me3 (Histone H3 Lysine 27 trimethylation)

- Primary Location: Promoters and gene bodies of developmentally regulated genes; can form Large Organized Chromatin K27 domains (LOCKs) spanning hundreds of kilobases [6].

- Function: Catalyzed by Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), it is a key mark for facultative heterochromatin and transcriptional repression of developmental genes. It is dynamically regulated and exhibits an antagonistic relationship with nuclear lamina association [7] [6].

H3K9me3 (Histone H3 Lysine 9 trimethylation)

- Primary Location: Constitutive heterochromatin, particularly at pericentromeric and centromeric regions, satellite repeats, and transposable elements [8] [5].

- Function: A hallmark of constitutive heterochromatin formation, ensuring stable, long-term transcriptional silencing. It acts as a major epigenetic barrier during cellular reprogramming, such as in somatic cell nuclear transfer [8].

Table 1: Core Histone Marks: Functional Roles and Distribution

| Histone Mark | Transcriptional Role | Primary Genomic Location | Proposed Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Activating | Promoters, near TSSs | Recruitment of pre-initiation complex, transcription initiation [1] [5] |

| H3K27ac | Activating | Active promoters and enhancers | Recruitment of transcription factors (e.g., BRD4) and RNA Pol II [5] [4] |

| H3K27me3 | Repressive | Promoters of developmental genes; LOCKs | Facultative heterochromatin; stable gene repression via PRC2 [5] [6] |

| H3K9me3 | Repressive | Constitutive heterochromatin; repeats & TEs | Formation of transcriptionally silent constitutive heterochromatin [8] [5] |

Correlation with Gene Expression: A Quantitative Validation

The predictive power of a histone mark for gene expression is the ultimate metric for its validation. Comprehensive machine learning studies analyzing seven histone marks across eleven human cell types have demonstrated that no single mark is universally the strongest predictor; performance depends on genomic context, cell type, and the specific regulatory element (promoter vs. enhancer) considered [5].

Table 2: Predictive Power of Histone Marks for Gene Expression

| Histone Mark | Correlation with Expression | Key Contextual Findings from Validation Studies |

|---|---|---|

| H3K27ac | Strong Positive | Often shows a stronger association with mRNA expression levels than H3K4me3 and can be a superior predictor, especially at enhancers [5] [3]. |

| H3K4me3 | Strong Positive | Highly predictive at promoters. Its presence is strongly correlated with active transcription, though it may not be causally sufficient for activation in all contexts [5] [4]. |

| H3K27me3 | Strong Negative | Peaks within LOCKs show stronger repression and lower expression of associated genes compared to typical peaks. It is a consistent marker of silenced genes [6]. |

| H3K9me3 | Strong Negative | A reliable marker of silent genomic regions, particularly those rich in repeats and transposable elements [8] [5]. |

Notably, the relationship between these marks and expression is not merely additive. For instance, the broad H3K4me3 domain, which is often co-associated with H3K27ac, is a particularly strong indicator of highly expressed, essential genes and is linked to frequent transcription bursting [1]. Furthermore, the presence of histone marks on transposable elements (TEs) contributes to regulatory evolution; studies in porcine tissues found that 1.45% of TEs overlapped with H3K27ac or H3K4me3 peaks, with the majority displaying tissue-specific activity, particularly in reproductive organs [3].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-Seq)

Purpose: To genome-wide map the binding sites of histone modifications. Detailed Workflow:

- Cross-linking: Covalently bind proteins to DNA in living cells using formaldehyde.

- Chromatin Fragmentation: Sonicate or enzymatically digest chromatin into 200-600 bp fragments.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate chromatin with a highly specific antibody against the target histone modification (e.g., anti-H3K4me3). Capture the antibody-protein-DNA complexes.

- Reverse Cross-linking & Purification: Release and purify the enriched DNA fragments.

- Library Prep & Sequencing: Prepare a sequencing library from the immunoprecipitated DNA and perform high-throughput sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Align sequences to a reference genome and identify significantly enriched regions ("peaks") using tools like MACS2 [9].

CRISPR/dCas-Based Epigenome Editing

Purpose: To establish causality between a histone mark and a transcriptional outcome, moving beyond correlation. Detailed Workflow:

- Designer Effector Construction: Create a fusion protein of a nuclease-deficient Cas9 (dCas9) and a catalytic domain from a histone-modifying enzyme (e.g., dCas9-p300 for H3K27ac or dCas9-SET for H3K4me3).

- sgRNA Design: Design single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) to target the effector complex to a specific genomic locus (e.g., a promoter of interest).

- Delivery: Transfect cells with plasmids encoding the dCas9-effector and sgRNAs.

- Validation:

- ChIP-qPCR: Quantify the localized enrichment of the installed histone mark at the target locus.

- RNA-seq/qPCR: Measure changes in mRNA expression of the target gene to assess functional consequences [4].

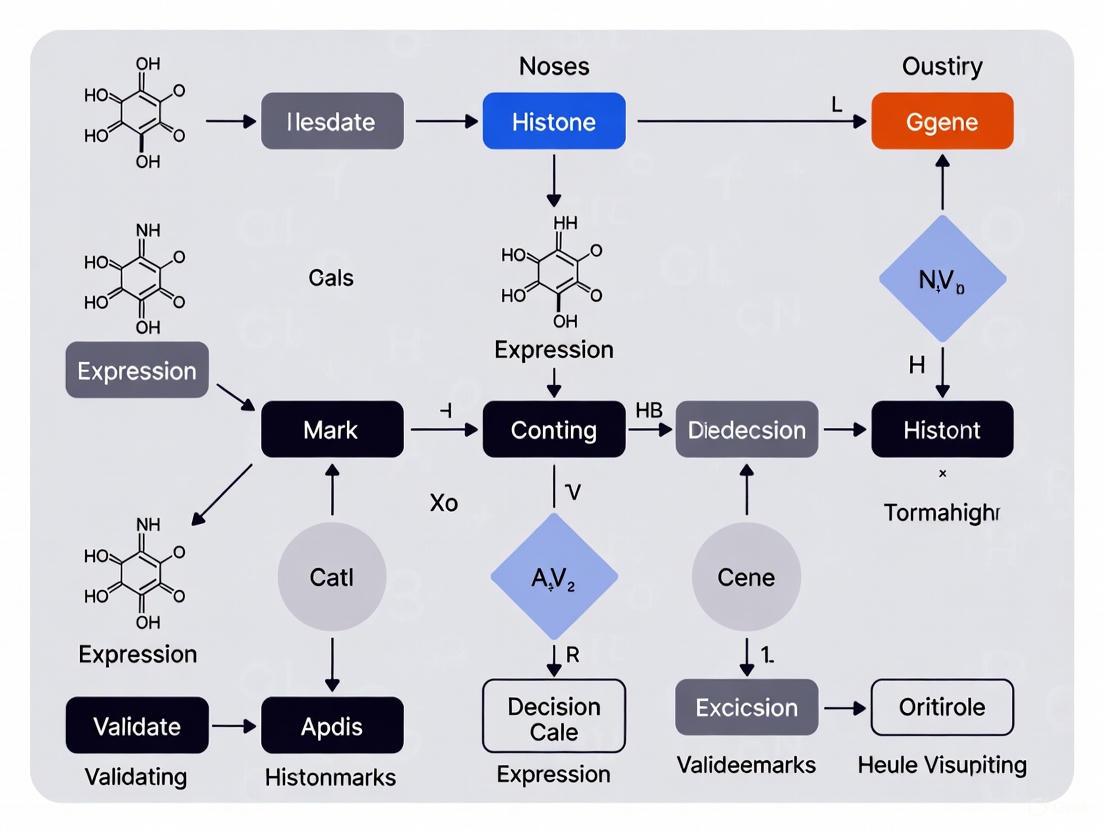

Pathway Diagrams: mechanistic Insights

Hierarchical Crosstalk in Transcriptional Activation

Experimental data from epigenome editing reveals a defined hierarchy between H3K27ac and H3K4me3. The installation of H3K27ac at a promoter acts as an upstream event that actively recruits machinery to deposit H3K4me3, leading to gene activation. This process is mediated by BRD2, a reader of H3K27ac. In contrast, installing H3K4me3 alone is insufficient to induce H3K27ac or activate transcription at the tested loci, indicating that H3K4me3 is a downstream consequence in this specific activation pathway [4].

Diagram Title: H3K27ac Induces H3K4me3 via BRD2

Antagonism in Nuclear Organization

In early embryonic development, an antagonistic relationship exists between H3K27me3 and genome organization at the nuclear lamina. H3K27me3 on broad domains counteracts the intrinsic affinity of certain genomic regions for the nuclear lamina, driving their repositioning away from the periphery. This "tug-of-war" is a key mechanism establishing the atypical spatial genome organization found in totipotent embryos [7].

Diagram Title: H3K27me3 Antagonizes Lamina Association

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Histone Code Research

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function and Application in Validation |

|---|---|

| Specific Anti-Histone Modification Antibodies | Core reagents for ChIP-seq, ChIP-qPCR, and immunofluorescence. Specificity is paramount (e.g., distinguish H3K4me3 from H3K4me1) [9]. |

| dCas9-Effector Fusion Plasmids | For causal testing: dCas9-p300 (installs H3K27ac), dCas9-SET1A (installs H3K4me3), and catalytically dead versions as controls [4]. |

| BET Bromodomain Inhibitors (e.g., JQ1) | Small molecule inhibitors that block the "reading" of H3K27ac by proteins like BRD2/4; used to dissect mechanistic pathways [4]. |

| Histone Demethylase Inhibitors | Chemical probes to inhibit erasers of histone marks (e.g., KDM5 family inhibitors for H3K4me3; KDM6 family inhibitors for H3K27me3) [8]. |

| ChIP-Seq & RNA-Seq Kits | Commercial kits for library preparation, ensuring reproducibility and efficiency in high-throughput sequencing workflows [3] [9]. |

| Peak Calling Software (e.g., MACS2) | Bioinformatic tools essential for identifying statistically significant regions of histone mark enrichment from ChIP-seq data [9]. |

| LOCK Identification Tools (e.g., CREAM R package) | Specialized computational tools for identifying large organized chromatin domains from broad histone marks like H3K27me3 LOCKs [6]. |

| HBT-O | HBT-O, CAS:2056899-56-8, MF:C17H13NO2S, MW:295.356 |

| AKI-001 | AKI-001, CAS:925218-37-7, MF:C21H24N4O, MW:348.4 g/mol |

The central dogma of molecular biology has long been overshadowed by the misconception that promoters serve as the primary gatekeepers of gene expression. While promoters provide the essential platform for transcription initiation, they represent merely one component in a sophisticated regulatory network that extends far beyond the transcription start site. Eukaryotic gene expression is precisely orchestrated through an intricate interplay between cis-regulatory elements and chromatin architecture, forming a multi-layered system that enables complex developmental programs, cellular differentiation, and environmental adaptation.

Contemporary epigenomic research has revealed that the genomic territories surrounding protein-coding sequences contain critical regulatory information encoded within enhancers, silencers, insulators, and various chromatin states. These elements collectively fine-tune transcriptional outputs in response to developmental cues and environmental signals. The validation of histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) through integration with gene expression data has been particularly transformative, providing a molecular roadmap for deciphering this regulatory code. This guide systematically compares the functional contributions, experimental validation approaches, and therapeutic implications of three fundamental regulatory domains: enhancers, facultative heterochromatin, and gene bodies, providing researchers with a framework for investigating genomic regulation beyond the promoter.

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Domains

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, histone modifications, and functional roles of the three primary regulatory domains discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Regulatory Domains Beyond the Promoter

| Regulatory Domain | Primary Function | Characteristic Histone Modifications | Genomic Distribution | Impact on Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhancers | Enhance transcription of target genes over long distances | H3K4me1, H3K27ac [5] [10] | Distal intergenic, intronic [11] | Strong activation [10] |

| Facultative Heterochromatin | Reversible gene silencing during development/differentiation | H3K27me3 [12] [5] [13] | Large, developmentally regulated domains [12] | Repression (reversible) [12] |

| Gene Bodies | Regulation of transcriptional elongation and RNA processing | H3K36me3 [5] | Transcribed regions | Activation/Co-transcriptional regulation [5] |

Enhancers: Long-Range Transcriptional Activators

Functional and Structural Characteristics

Enhancers are distal cis-regulatory elements that significantly boost the transcription of target genes, independent of their orientation or position, which can be up to megabases away from their target promoters [14]. They are fundamental to establishing cell identity and orchestrating complex developmental programs. Super-enhancers (SEs), a particularly potent class, are large clusters of enhancers that exhibit exceptionally strong transcriptional activation capabilities [10]. Structurally, SEs are characterized by their large size (typically 8-20 kb, compared to 200-300 bp for typical enhancers), high density of transcription factor binding, and enrichment of specific coactivators and histone marks [10]. They frequently reside within specialized chromatin structures called super-enhancer domains (SDs), often demarcated by CTCF-mediated loop boundaries [10].

Key Histone Marks and Experimental Validation

The core histone modifications associated with active enhancers include H3K4me1 and H3K27ac [5] [10]. While H3K4me1 is enriched at both active and poised enhancers, H3K27ac specifically distinguishes actively engaged enhancers [5]. These marks facilitate an open chromatin state and recruit additional transcriptional co-activators.

Advanced methodologies for mapping enhancer-promoter interactions have progressed significantly. Micro-C-ChIP represents a cutting-edge approach that combines Micro-C (a high-resolution chromatin conformation capture method using MNase for nucleosome-scale fragmentation) with chromatin immunoprecipitation to map 3D genome organization for specific histone modifications [15]. This technique allows researchers to identify genuine enhancer-promoter interactions with high specificity and reduced sequencing costs compared to genome-wide methods [15] [14]. The workflow involves crosslinking chromatin, MNase digestion, biotinylation of DNA ends, proximity ligation, sonication, and immunoprecipitation with antibodies against specific histone marks like H3K4me3 or H3K27ac [15]. The resulting data can reveal intricate promoter-promoter contact networks and specific interactions at bivalent promoters.

Figure 1: Enhancer Activation Pathway. Enhancers marked by H3K4me1 and H3K27ac recruit mediator complexes and RNA Polymerase II to promoters, activating gene expression.

Facultative Heterochromatin: Reversible Repressive Domains

Functional and Structural Characteristics

Facultative heterochromatin represents a reversibly silenced chromatin state that plays crucial roles in cell differentiation, development, and maintaining cellular identity by dynamically repressing genes in a cell-type-specific manner [12]. Unlike constitutive heterochromatin (which is permanently silent and enriched with H3K9me3), facultative heterochromatin is defined by the presence of H3K27me3 and can transition between silent and active states during development [12]. Recent research in Pyricularia oryzae has revealed that facultative heterochromatin is not a uniform entity but consists of distinct subcompartments: K4-fHC (adjacent to euchromatin and enriched for genes responsive to environmental cues) and K9-fHC (adjacent to constitutive heterochromatin and harboring more transposable elements) [12].

A groundbreaking mechanistic insight involves the formation of immiscible phase-separated condensates. Studies show that multivalent H3K27me3 and its reader complex, CBX7-PRC1, regulate facultative heterochromatin through liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) [13]. These H3K27me3-driven facultative condensates exist as distinct, immiscible compartments separate from H3K9me3-driven constitutive heterochromatin condensates, providing a physical basis for the maintenance of distinct chromatin states within the nucleus [13].

Key Histone Marks and Experimental Mapping

The defining histone mark for facultative heterochromatin is H3K27me3, catalyzed by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) [12] [5]. This mark is recognized by reader proteins like CBX7 (part of PRC1), which facilitates chromatin compaction and transcriptional repression [13]. The interplay between different histone modifications is crucial; for instance, loss of H3K9me3 can lead to a redistribution of H3K27me3 into constitutive heterochromatin regions, demonstrating the dynamic crosstalk between these repressive systems [12].

Investigating the 3D architecture of facultative heterochromatin is possible using Micro-C-ChIP for H3K27me3 [15]. This method has been applied to map the distinct spatial organization of bivalent promoters in mouse embryonic stem cells, which are simultaneously marked by both active (H3K4me3) and repressive (H3K27me3) marks, poising them for either activation or silencing during differentiation [15].

Table 2: Comparison of Heterochromatin Types

| Feature | Facultative Heterochromatin | Constitutive Heterochromatin |

|---|---|---|

| Defining Mark | H3K27me3 [12] [13] | H3K9me3 [12] [16] |

| Reader Protein | CBX7 (PRC1) [13] | HP1 (CBX1, CBX3, CBX5) [16] |

| Genomic Content | Developmentally regulated genes [12] | Repetitive sequences, telomeres, centromeres [16] |

| Stability | Reversible, dynamic [12] | Stable, permanent [12] |

| Phase Separation | H3K27me3-PRC1 driven condensates [13] | H3K9me3-HP1 driven condensates [13] |

Figure 2: Heterochromatin Formation via Phase Separation. Facultative and constitutive heterochromatin form immiscible condensates via distinct histone marks and reader proteins, leading to gene repression.

Gene Bodies: Internal Regulatory Landscapes

Functional and Structural Characteristics

The protein-coding regions of genes, known as gene bodies, are not merely passive templates for transcription but contain important regulatory information that influences transcriptional elongation, alternative splicing, and the definition of exonic and intronic boundaries. The chromatin state within gene bodies provides a historical record of transcriptional activity and contributes to the regulation of co-transcriptional processes.

The primary histone mark associated with gene bodies is H3K36me3, which is deposited during transcriptional elongation and serves as a binding partner for histone deacetylases (HDACs) that prevent spurious transcription initiation within gene bodies [5]. This mark helps maintain transcriptional fidelity by suppressing internal promoters and ensuring processive transcription.

Emerging Research and Experimental Approaches

Research into intragenic regulation continues to reveal unexpected complexities. For instance, heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) family members, known for their role in constitutive heterochromatin through recognition of H3K9me3, also play roles in alternative splicing regulation when present in gene bodies [16]. In humans, HP1 can act as either an enhancer or silencer of alternative exons depending on the gene context and methylation patterns [16]. For example, in the fibronectin gene, HP1 binding to methylated chromatin within the gene body recruits splicing factor SRSF3, leading to exclusion of the EDA exon from the mature transcript [16].

Investigating gene body regulation typically involves ChIP-seq for H3K36me3 combined with RNA-seq to correlate the distribution of this mark with transcriptional output [5]. More sophisticated approaches now include predicting gene expression levels from histone mark patterns using convolutional and attention-based deep learning models, which can integrate information from promoters, gene bodies, and distal regulatory elements [5].

Silencers: The Repressive Counterparts to Enhancers

Functional and Structural Characteristics

Silencers represent a critical class of cis-regulatory elements that repress gene transcription, serving as functional counterparts to enhancers [11]. Like enhancers, they can function independently of orientation and distance from their target genes [11]. Until recently, silencers have been less systematically studied than enhancers, but emerging evidence indicates they play essential roles in fine-tuning gene expression patterns during development and differentiation.

Genome-wide screening in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and embryonic stem cells (mESCs) has identified 89,596 and 115,165 silencers, respectively [11]. These elements are ubiquitously distributed across the genome, predominantly in distal intergenic and intronic regions, and are strongly associated with low-expression genes [11]. Silencers exhibit cell-type specificity and function primarily by recruiting repressive transcription factors, with notable enrichment for motifs linked to the zinc finger and Fox families [11].

Key Histone Marks and Experimental Identification

The most significantly enriched histone modification at silencer regions is H3K9me3 [11], a mark traditionally associated with constitutive heterochromatin. This suggests that some silencers may operate through the establishment of local heterochromatic environments. Silencers also show enrichment for binding by well-known repressive transcription factors and complexes including REST, YY1, SUZ12, EZH2, and TRIM28 [11].

The leading-edge methodology for genome-wide silencer identification is Ss-STARR-seq (Silencer-Selective Self-Transcribing Active Regulatory Region Sequencing) [11]. This technique involves constructing a library of genomic fragments cloned into a reporter vector downstream of a minimal promoter. When transfected into cells, fragments with silencer activity reduce reporter expression relative to input levels, allowing for high-throughput identification and quantification of silencer elements [11]. Functional validation typically follows through techniques like dual-luciferase assays after transcription factor knockdown [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Regulatory Genomics

| Reagent/Assay | Primary Function | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ss-STARR-seq [11] | Genome-wide silencer identification | Screening for repressive cis-regulatory elements | Uses minimal PGK promoter; requires high-throughput sequencing |

| Micro-C-ChIP [15] | Mapping 3D chromatin architecture for specific histone marks | Enhancer-promoter interactions; facultative heterochromatin organization | Combines Micro-C resolution with ChIP specificity; lower sequencing depth than full Micro-C |

| H3K27me3 ChIP-seq [12] | Mapping facultative heterochromatin domains | Identifying Polycomb-repressed regions | Critical for developmental studies; shows redistribution in KMT mutants |

| H3K9me3 ChIP-seq [11] [12] | Mapping constitutive heterochromatin and some silencers | Studying permanent silencing and silencer elements | Enriched at identified silencer regions [11] |

| CRADLE Software [11] | Bioinformatics analysis of STARR-seq data | Identifying silencers from STARR-seq output | Specifically designed for silencer identification in STARR-seq systems |

| CBX7 Inhibitors [13] | Perturbing facultative heterochromatin condensates | Studying phase separation in heterochromatin; potential therapeutic applications | Affects cancer cell proliferation via compartment reorganization |

| Botryococcane C33 | Botryococcane C33 | Botryococcane C33, a unique botanical biomarker for paleoenvironmental research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| N-Cbz-nortropine | N-Cbz-nortropine, CAS:109840-91-7, MF:C₁₅H₁₉NO₃, MW:261.32 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Integrated Experimental Workflow for Validating Histone Marks

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental approach for investigating histone mark function and its relationship to gene expression, integrating multiple techniques discussed in this guide.

Figure 3: Integrated Workflow for Histone Mark Validation. A multi-step approach combining wet-lab and computational methods to correlate histone marks with gene expression.

The intricate landscape of genomic regulation extends far beyond the promoter, encompassing a dynamic interplay between enhancers, silencers, facultative heterochromatin, and gene bodies. Each of these regulatory domains contributes unique functions and is characterized by specific histone modifications that can be systematically mapped and validated through modern genomic technologies. The emerging paradigm recognizes that these elements do not operate in isolation but form complex, three-dimensional networks that integrate developmental cues and environmental signals to fine-tune gene expression.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these regulatory mechanisms opens promising therapeutic avenues. The ability to target specific components of this regulatory machinery—such as CBX7-PRC1 in facultative heterochromatin formation or specific enhancer-promoter interactions—holds potential for treating diseases driven by epigenetic dysregulation, including cancer, neurological disorders, and autoimmune conditions [13] [10]. As technologies for mapping and manipulating these elements continue to advance, particularly through single-cell approaches and more sophisticated computational integration, our capacity to decipher and therapeutically target the non-coding genome will undoubtedly expand, ushering in a new era of epigenetic medicine focused on the vast regulatory landscape beyond the promoter.

The long-standing endeavor to predict gene expression from histone modifications has evolved from a search for a simple, universal code to a more nuanced understanding of a complex, context-dependent system. Initial studies established that histone marks correlate with transcriptional states [17]. However, contemporary research demonstrates that this relationship is not deterministic; it is profoundly shaped by the cellular state, the genomic distance from regulatory elements, and the intricate interplay between histone marks themselves [5]. Ignoring these factors leads to incomplete or cell-type-specific models with limited predictive power. This guide synthesizes recent experimental data to objectively compare how these critical factors modulate the histone mark-expression relationship, providing a framework for researchers validating histone marks in gene regulation studies, particularly in drug discovery and disease modeling.

The Triad of Influential Factors

Cellular State and Differentiation

The cellular context, including lineage, differentiation stage, and metabolic state, is a primary determinant of how histone marks regulate transcription.

- Embryonic Development and Cellular Heterogeneity: Single-cell epigenomic analyses of mouse early embryos reveal that histone modifications are extensively reprogrammed during development. Notably, heterogeneity in H3K27ac profiles emerges as early as the two-cell stage, preceding significant variation in other marks like H3K4me3, which becomes more prominent at the four-cell stage [18]. This suggests that the regulatory influence of specific marks shifts with developmental progression.

- Cell-Type-Specific Predictive Power: A comprehensive 2024 study analyzing eleven human cell types found that no single histone mark is consistently the strongest predictor of gene expression across all cellular contexts [5]. The predictive performance of individual marks varies significantly depending on the cell type, underscoring that models trained in one cellular state may not transfer directly to another.

Genomic Distance and 3D Chromatin Architecture

The impact of a histone modification is heavily dependent on its genomic location relative to gene promoters and its role within the three-dimensional nuclear space.

- Promoter vs. Enhancer Logic: The function of a histone mark is location-specific. H3K4me3 is a hallmark of active promoters, while H3K4me1 is enriched at enhancers [5] [19]. However, the presence of H3K4me1 alone is not sufficient for enhancer activity; it requires the additional presence of H3K27ac to distinguish active enhancers from poised ones [5].

- Spatial Proximity Matters: The development of Micro-C-ChIP, a method that maps 3D genome organization for specific histone modifications, has directly linked marks to spatial interactions. This research shows that H3K4me3-marked promoters form extensive 3D interaction networks with other promoters and distal regulatory elements [15]. The gene expression of a given promoter is therefore influenced not only by its own histone marks but also by the marks on spatially interacting regions, highlighting the need to consider genomic distance in three dimensions.

Combinatorial Interplay of Histone Marks

Histone marks do not function in isolation; they form complex combinatorial codes that can either reinforce or antagonize each other's functions.

- The Bivalent Domain Paradigm: In embryonic stem cells, many key developmental gene promoters exhibit a "bivalent" chromatin state, simultaneously harboring the active mark H3K4me3 and the repressive mark H3K27me3 [17]. This poises genes for rapid activation or silencing upon differentiation, demonstrating how opposing marks can interact to create a unique regulatory outcome not predictable from either mark alone [17] [15].

- Predictive Synergy in Machine Learning: Quantitative models support the power of combinations. A model using just three marks (H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K20me1) could predict gene expression in human T-cells almost as accurately as a model using all 39 marks measured [17]. Furthermore, the most predictive marks differ for genes with high-CpG promoters (H3K27ac, H4K20me1) versus low-CpG promoters (H3K4me3, H3K79me1), illustrating combinatorial and context-specific rules [17].

Quantitative Comparison of Predictive Histone Marks

Table 1: Predictive Performance of Individual Histone Marks Across Cellular Contexts. This table summarizes findings from a comprehensive 2024 study that used neural networks to predict gene expression from single histone marks in eleven cell types [5]. The ranking illustrates the context-dependence of predictive power.

| Histone Mark | Primary Genomic Location | Transcriptional Relationship | Example Cell Type Where Highly Predictive | Key Proposed Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K27ac | Active enhancers and promoters | Activating | Varied across cell types; a top performer for HCP genes [17] [5] | Recruits transcription factors (e.g., BRD4) to increase transcription [5] |

| H3K4me3 | Promoter regions | Activating | A top performer for LCP genes [17] [5] | Recruits nucleosome remodeling complexes to make DNA accessible [5] |

| H3K9ac | Promoter regions | Activating | Varied across cell types [5] | Mediates the switch from transcription initiation to elongation [5] |

| H3K36me3 | Gene bodies | Repressive | Varied across cell types [5] | Recruits histone deacetylases (HDACs) to prevent spurious transcription [5] [17] |

| H3K27me3 | Promoters and gene bodies | Repressive | Key mark in bivalent domains in mESCs [17] [15] | Associated with Polycomb-mediated silencing and chromatin compaction [17] [5] |

| H3K9me3 | Constitutive heterochromatin | Repressive | Varied across cell types [5] | Involved in transcriptional silencing and heterochromatin formation [5] |

| H3K4me1 | Enhancer regions | Activating (Poised/Active) | Varied across cell types [5] | Fine-tunes enhancer activity by recruiting key transcription factors [5] |

Table 2: Comparison of Key Experimental Methodologies for probing the Histone Mark-Expression Relationship.

| Methodology | Key Feature | Resolution | Primary Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChIP-seq [17] | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation with sequencing | Locus-specific | Mapping histone mark enrichment across the genome | Requires a specific antibody; provides 1D data |

| Micro-C-ChIP [15] | Micro-C combined with ChIP for specific histone marks | Nucleosome-resolution for specific marks | Mapping histone-mark-specific 3D genome architecture | Reduces sequencing burden by focusing on marked regions; reveals spatial interactions |

| TACIT/CoTACIT [18] | Target Chromatin Indexing and Tagmentation | Genome-coverage single-cell profiling | Profiling multiple histone modifications at single-cell resolution across development | Reveals cellular heterogeneity and co-occurrence of marks in the same cell |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) / Neural Networks [17] [5] | Machine learning models using histone modification data | Quantitative, genome-wide | Building predictive models of gene expression from histone mark data | Can quantify the relative contribution of different marks and their combinations |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Micro-C-ChIP for Histone-Mark-Specific 3D Architecture

This protocol, as detailed in Nature Communications (2025), maps the 3D interactome of genomic regions marked by specific histone modifications [15].

- In Situ Cross-linking and Nuclei Isolation: Cells are dually cross-linked with formaldehyde and disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG). Nuclei are then isolated.

- MNase Digestion: Chromatin is digested with Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase), which cleaves linker DNA and leaves nucleosomes intact, enabling nucleosome-resolution mapping.

- End Biotinylation and Proximity Ligation: The digested DNA ends are filled in with biotin-labeled nucleotides. Spatial proximity is captured via in situ ligation to form chimeric DNA molecules.

- Sonication and Immunoprecipitation: The cross-linked, ligated chromatin is solubilized by sonication. Chromatin immunoprecipitation is then performed using an antibody against the target histone modification (e.g., H3K4me3 or H3K27me3).

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The biotin-labeled, proximity-ligated fragments are purified and used to generate a sequencing library.

This method is superior to earlier approaches like HiChIP as it maintains a higher fraction of informative short-range reads and leverages in situ ligation to preserve true 3D interactions [15].

Single-Cell Multi-Modality Profiling with TACIT and CoTACIT

This workflow, from Nature (2025), enables genome-wide profiling of up to three histone modifications in the same single cell [18].

TACIT for Single Modifications:

- Cell Permeabilization: Single cells are fixed and permeabilized.

- Antibody Binding: Cells are incubated with a primary antibody against a specific histone mark.

- PAT Transposition: A Protein A-Tn5 transposase (PAT) complex, pre-loaded with sequencing adapters, is recruited via the antibody.

- Tagmentation: The PAT complex simultaneously cleaves the DNA and adds adapters to the fragments bound by the histone mark.

CoTACIT for Multiple Modifications:

- The process is repeated in sequential rounds for different histone marks. After the first round of tagmentation for one mark (e.g., H3K27ac), the next primary antibody (e.g., for H3K27me3) is added, followed by its corresponding PAT complex for a second round of tagmentation.

- This iterative process allows for the simultaneous mapping of multiple epigenetic features in the same cell.

Library Amplification and Sequencing: The tagmented DNA from all rounds is amplified to create a sequencing library.

This approach provides unprecedented insight into the co-occurrence of histone marks and cellular heterogeneity during dynamic processes like embryonic development [18].

Visualization of Relationships and Workflows

Diagram 1: The Interdependent Relationship Between Histone Marks, Influencing Factors, and Gene Expression. The core histone marks (green for activating, red for repressive) directly influence expression, but their effect is modulated (dashed lines) by cellular state, genomic context, and combinatorial interplay.

Diagram 2: Micro-C-ChIP Workflow for Mapping Histone-Mark-Specific 3D Interactions. The protocol combines chromatin fragmentation at nucleosome resolution with immunoprecipitation to enrich for interactions involving specific histone marks, providing a cost-efficient method for high-resolution 3D mapping [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Histone-Gene Expression Studies.

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Protein A-Tn5 Transposase (PAT) | Antibody-recruited tagmentation for targeted sequencing | TACIT/CoTACIT for single-cell histone modification profiling [18] |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Enzyme that digests linker DNA, leaving nucleosomes intact | Micro-C and Micro-C-ChIP for nucleosome-resolution chromatin structure analysis [15] |

| Dual Cross-linkers (Formaldehyde + DSG) | Stabilizes protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions over larger distances | Micro-C-ChIP to capture complex 3D interactions [15] |

| Histone Modification-Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of chromatin fragments bearing specific PTMs | ChIP-seq, Micro-C-ChIP, and TACIT for mapping and enriching specific histone marks [17] [15] [18] |

| Biotin-dNTPs | Labeling of DNA ends for selective purification | Enriching for proximity-ligated fragments in Micro-C-ChIP [15] |

| (R,R)-Cilastatin | (R,R)-Cilastatin, CAS:107872-23-1, MF:C₁₆H₂₆N₂O₅S, MW:358.45 | Chemical Reagent |

| Δ2-Cefdinir | Δ2-Cefdinir, CAS:934986-49-9, MF:C₁₄H₁₃N₅O₅S₂, MW:395.41 | Chemical Reagent |

The relationship between histone modifications and gene expression is a dynamic and context-dependent system, not a static code. Robust validation of histone marks in research, especially for drug development applications, must account for the cellular state, the 3D genomic architecture, and the combinatorial rules governing mark interplay. Experimental designs that leverage single-cell multi-omics, histone-mark-specific 3D mapping, and sophisticated computational models are essential to move beyond correlation and toward a causal, predictive understanding of epigenetic regulation. Future breakthroughs in therapeutics will likely come from manipulating these complex relationships, rather than targeting individual marks in isolation.

In eukaryotic organisms, the genome is organized into distinct structural and functional compartments that regulate gene expression and genome stability. These compartments—euchromatin (EC), constitutive heterochromatin (cHC), and facultative heterochromatin (fHC)—are characterized by specific combinations of histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) that create an epigenetic code read by cellular machinery to determine transcriptional activity [20]. While EC and cHC represent transcriptionally active and permanently silenced states respectively, fHC has emerged as a more dynamic and complex compartment capable of transitioning between repressive and active states in response to developmental and environmental cues [12]. Recent research has revealed unexpected complexity within these compartments, particularly the existence of distinct fHC subtypes with specialized regulatory functions [12] [21]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of key genomic compartments, focusing on newly identified fHC subtypes, their experimental characterization, and the integration of histone mark validation with gene expression data.

Comparative Analysis of Genomic Compartments

Defining Characteristics and Functional Roles

Table 1: Characteristic Features of Major Genomic Compartments

| Compartment | Defining Histone Marks | Genomic Content | Transcriptional State | Dynamic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euchromatin (EC) | H3K4me2/3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac [5] [20] | Gene-rich regions, housekeeping genes [22] | Actively transcribed | Constitutively active |

| Constitutive Heterochromatin (cHC) | H3K9me3 [12] [22] | Repetitive elements, telomeres, centromeres [22] | Permanently silenced | Stable, heritable repression |

| Facultative Heterochromatin (fHC) | H3K27me3 [12] | Developmentally-regulated genes, lineage-specific genes [12] | Reversibly silenced | Environmentally responsive |

| K4-fHC Subtype | H3K27me3 with H3K4me2/3 proximity [12] | Infection-responsive genes, effector genes [12] | Poised for activation | Highly responsive to cues |

| K9-fHC Subtype | H3K27me3 adjacent to H3K9me3 domains [12] | Transposable elements, poorly conserved genes [12] | Stably repressed | Intermediate responsiveness |

Quantitative Genomic Distribution

Table 2: Genomic Distribution Across Compartments in Pyricularia oryzae [12]

| Chromosome | Euchromatin (EC) | K4-fHC | K9-fHC | Constitutive Heterochromatin (cHC) | Unassigned (UA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr 1 | 1028 segments | 516 segments | 905 segments | 794 segments | 2997 segments |

| Chr 2 | 1988 segments | 310 segments | 358 segments | 356 segments | 4957 segments |

| Chr 3 | 1214 segments | - | - | - | - |

| Total Genome | 8183 segments (19.3%) | Part of 7541 fHC segments (17.7%) | Part of 7541 fHC segments (17.7%) | 3417 segments (8.0%) | 23,361 segments (55.0%) |

Experimental Protocols for Compartment Characterization

Integrated ChIP-seq and RNA-seq Workflow

The identification and validation of genomic compartments, particularly the novel fHC subtypes, requires an integrated multi-omics approach. The following protocol has been successfully employed to characterize compartment-specific histone marks and their functional consequences [12]:

Sample Preparation: Culture cells or organisms under controlled conditions. For disease context studies (e.g., Pyricularia oryzae), include infection-mimicking conditions.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq):

- Crosslink proteins to DNA with formaldehyde

- Sonicate chromatin to 200-500 bp fragments

- Immunoprecipitate with histone modification-specific antibodies (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K9me3, H3K27me3)

- Reverse crosslinks, purify DNA, and prepare sequencing libraries

- Sequence using high-throughput platforms (Illumina)

RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq):

- Extract total RNA under identical conditions

- Deplete ribosomal RNA or enrich poly-A transcripts

- Prepare strand-specific cDNA libraries

- Sequence to determine transcript abundance

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Map ChIP-seq reads to reference genome, calculate Reads Per Million (RPM) in defined windows (e.g., 1kb)

- Call significant peaks using HOMER or similar software [12]

- Define genomic compartments based on histone mark combinations:

- EC: Consecutive H3K4me2-rich segments

- cHC: Consecutive H3K9me3-rich segments

- fHC: Consecutive H3K27me3-rich segments

- Integrate RNA-seq data (RPKM values) to correlate compartment state with gene expression

- Identify fHC subtypes based on adjacency to other compartments (K4-fHC near EC, K9-fHC near cHC)

Advanced Methodologies for Compartment Validation

Stacked Chromatin State Modeling: For analyzing epigenetic variation across individuals, employ the stacked ChromHMM approach [23]:

- Collect histone modification data (H3K27ac, H3K4me1, H3K4me3) across multiple individuals

- Process data in 200bp non-overlapping bins, regressing out technical confounders

- Binarize data using Poisson background model as ChromHMM input

- Train multivariate Hidden Markov Model to identify recurring combinatorial patterns across individuals

- Annotate genome with universal chromatin state assignments representing global patterns

Single-Molecule Multi-Omics Profiling: nanoCAM-seq enables simultaneous profiling of [24]:

- Higher-order chromatin interactions via chromatin conformation capture

- Chromatin accessibility through transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing

- Endogenous CpG methylation via bisulfite sequencing

- All measurements from the same DNA molecule for direct correlation

Visualization of Genomic Compartment Relationships

Diagram 1: Hierarchical relationships between genomic compartments and their regulatory influences. Facultative heterochromatin (fHC) contains distinct subtypes with specialized characteristics and functions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Genomic Compartment Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Modification Antibodies | Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K9me3, Anti-H3K27me3, Anti-H3K27ac [12] [5] | Immunoprecipitation of mark-specific chromatin fragments | ChIP-seq for compartment mapping |

| Chromatin Profiling Kits | itChIP-seq kits [21], nanoCAM-seq reagents [24] | Low-input chromatin profiling, multi-omics integration | Epigenetic analysis of rare cell populations |

| Epigenetic Modulators | KMT inhibitors, HDAC inhibitors [20] | Perturb histone modification states | Functional validation of compartment dynamics |

| Bioinformatic Tools | HOMER [12], ChromHMM [23], Chromoformer [5] | Peak calling, chromatin state annotation, expression prediction | Computational analysis of multi-omics data |

| Cell Type Models | Pyricularia oryzae strains [12], Human myoblasts [22], Mouse embryonic cells [21] | Study compartment dynamics in development and disease | Model systems for compartment characterization |

| (R)-Zearalenone | (R)-Zearalenone, CAS:1394294-92-8, MF:C₁₈H₂₂O₅, MW:318.36 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| RTI-51 Hydrochloride | RTI-51 Hydrochloride, CAS:1391052-88-2, MF:C16H21BrClNO2, MW:374.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Integration with Gene Expression Validation

A critical advancement in characterizing genomic compartments has been the rigorous correlation of histone marks with transcriptional outputs through machine learning approaches. Chromoformer and similar deep learning architectures demonstrate that predictive relationships between histone modifications and gene expression depend on genomic context and cell state [5]. Key findings include:

- No Universal Predictor: No single histone mark consistently predicts expression across all contexts; combinatorial patterns provide superior predictive power [5]

- Compartment-Specific Relationships: Active marks (H3K4me3, H3K27ac) show strongest correlation with expression in EC, while repressive marks (H3K27me3) better predict silencing in fHC [5]

- Dynamic Responsiveness: K4-fHC shows stronger correlation with condition-responsive genes compared to the more stable K9-fHC [12]

- Cross-Species Conservation: Compartment-specific mark-function relationships are conserved from fungi to mammals despite differences in genomic distribution [12] [22]

The stacked chromatin state modeling approach further enables identification of "global patterns" of epigenetic variation that recur across multiple genomic regions and correlate with expression quantitative trait loci (QTLs), providing a framework for connecting compartment states to transcriptional regulation across individuals [23].

Functional Significance and Research Applications

The characterization of distinct fHC subtypes has profound implications for understanding genome regulation in development and disease. The K4-fHC subtype, enriched for infection-responsive genes in fungal pathogens, represents a "reservoir of genes highly responsive to chromatin context and environmental cues" [12]. This compartment appears strategically positioned at the interface between active and repressive chromatin states, allowing rapid transcriptional reprogramming in response to environmental signals.

In mammalian systems, proteins like SMCHD1 function as "anchors for heterochromatin domains at the nuclear lamina" [22], maintaining compartment integrity and ensuring proper gene silencing. Disruption of these anchoring mechanisms leads to B-to-A compartment transitions, aberrant gene activation, and disease states [22].

These findings highlight the importance of genomic compartment characterization for understanding the epigenetic basis of cellular identity, environmental adaptation, and disease mechanisms. The experimental frameworks outlined here provide researchers with robust methodologies for advancing these investigations across diverse biological systems.

Computational Frameworks: From Data Integration to Predictive Modeling

The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium and similar large-scale projects have fundamentally transformed our understanding of gene regulation by generating comprehensive, publicly available epigenomic maps. These consortia provide systematically processed data that enables researchers to investigate how chromatin organization contributes to cellular identity, development, and disease pathogenesis. The integration of Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data lies at the heart of efforts to validate the functional impact of histone modifications on gene expression patterns. Such integrated analyses are particularly valuable for research aimed at understanding the role of specific histone marks in disease contexts, such as cancer biology and drug development [25] [26].

These projects employ standardized computational pipelines to ensure data consistency and quality across numerous cell types and tissues. The Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium, for instance, generated 111 reference epigenomes from diverse human primary cells and tissues, profiled for histone modification patterns, DNA accessibility, DNA methylation, and RNA expression [26]. This systematic approach provides an unprecedented resource for investigating the relationship between epigenetic marks and transcriptional output, offering researchers a robust foundation for hypothesis generation and testing in histone mark validation studies.

Comparative Analysis of Consortium Data Processing Pipelines

Roadmap Epigenomics Processing Standards

The Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium established rigorous standards for processing ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data to ensure cross-sample comparability. Their uniform processing pipeline involves multiple critical steps, each with specific parameters designed to handle data generated from different centers and sequencing technologies [27]. For read mapping, the consortium employs the Pash 3.0 read mapper to align sequencing reads to the hg19 assembly of the human genome, retaining only uniquely mapping reads while filtering out duplicates [27]. To address technical variability, the consortium implemented a mappability filtering step where raw mapped reads are uniformly truncated to 36 bp and refiltered using a 36 bp custom mappability track to retain only reads mapping to unique genomic positions [27].

A crucial normalization step involves subsampling consolidated histone mark datasets to a maximum depth of 30 million reads (the median read depth over all consolidated samples), while DNase-seq datasets are subsampled to 50 million reads [27]. This approach mitigates artificial differences in signal strength due to variable sequencing depth. For peak calling, the MACSv2.0.10 peak caller is used to identify narrow regions of enrichment and broad domains by comparing ChIP-seq signal to whole cell extract (WCE) sequenced controls, with fragment length parameters estimated using strand cross-correlation analysis [27]. The consortium also generates genome-wide signal coverage tracks in both BIGWIG format for -log10(p-value) and fold-enrichment signals [27].

ENCODE Processing Approaches

The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project employs complementary processing methodologies that share similarities with Roadmap Epigenomics but also exhibit distinct characteristics. While both consortia utilize advanced peak calling algorithms, ENCODE has developed specific standards for data quality assessment and metadata annotation. ENCODE's data processing emphasizes reproducibility through rigorous benchmarking of computational pipelines and extensive quality control metrics [28]. The project provides comprehensive metadata for each dataset, detailing experimental protocols, processing steps, and quality measures, enabling researchers to make informed decisions about data utilization [28].

Comparative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of ChIP-seq Data Processing Pipelines

| Processing Step | Roadmap Epigenomics | ENCODE | Typical In-house Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Mapping | Pash 3.0 with unique mapping | BWA, Bowtie2 | Bowtie2, BWA, STAR |

| Read Length Handling | Uniform truncation to 36bp | Variable lengths supported | Variable, platform-dependent |

| Peak Calling | MACSv2.0.10 with WCE controls | MACS2, SPP | MACS2, HOMER |

| Normalization Approach | Subsampling to fixed read counts | Signal scaling methods | TMM, DESeq2, or similar |

| Data Output Formats | BIGWIG, NarrowPeak, BroadPeak | BIGWIG, BED, BAM | BED, WIG, custom formats |

| Quality Metrics | Strand cross-correlation, mapping statistics | NSC, RSC, FRiP | FRiP, NSC, sample correlation |

Table 2: RNA-seq Data Processing in Multi-omics Context

| Processing Aspect | Roadmap Epigenomics | ENCODE | Integrated Analysis Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Quantification | RPKM/FPKM normalized counts | CPM, TPM | Variance-stabilizing transformations |

| Differential Expression | Not consistently applied | DESeq2, edgeR | Paired analysis with epigenetic data |

| Multi-omics Integration | Chromatin state annotations | Candidate cis-Regulatory Elements (cCREs) | Coordinated regulatory element-gene linking |

| Batch Effect Correction | Cross-center consistency checks | Replicate concordance | ComBat, surrogate variable analysis |

| Data Availability | Processed signal tracks, chromatin states | Processed peaks, signal tracks | Coordinated data access through portals |

Experimental Protocols for Histone Mark Validation with Gene Expression

Integrated Analysis Workflow

Validating histone marks with gene expression data requires a methodical approach that leverages consortium data while implementing robust statistical integration. A proven workflow begins with data acquisition from consortium portals, specifically selecting matched ChIP-seq and RNA-seq datasets from biologically relevant cell types or tissues [25] [29]. The Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium provides data through multiple access points, including the Reference Epigenome Mapping Consortium homepage, NCBI Epigenomics Hub, and the Human Epigenome Atlas, each offering different download and visualization options [29]. For histone mark validation, researchers should prioritize datasets with H3K4me3 (promoter-associated), H3K27ac (active enhancer), H3K36me3 (transcriptional elongation), and H3K27me3 (Polycomb-repressed) marks, as these show strong correlations with gene expression states [26].

The subsequent analytical phase involves quantifying relationships between histone modifications and transcriptional output. This includes calculating histone enrichment levels at genomic regions of interest, normalizing RNA-seq expression values, and performing statistical integration. The Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium has demonstrated that specific chromatin states derived from histone mark combinations show distinct levels of DNA methylation and accessibility, and predict differences in RNA expression levels that are not reflected in either accessibility or methylation alone [26]. For example, actively transcribed states (Tx) and strong enhancer states (Enh) show high correlation with gene expression, while repressed states (ReprPC) and quiescent states (Quies) show inverse correlations [26].

Case Study: HPV+ Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma

A representative example of successful integration comes from a study on HPV+ head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), where researchers developed a whole-genome analytical pipeline to optimize ChIP-seq protocols on patient-derived xenografts [25]. This approach enabled the association of chromatin aberrations with gene expression changes from a larger cohort of tumor and normal samples with RNA-seq data. The study detected differential histone enrichment associated with tumor-specific gene expression variation, sites of HPV integration, and HPV-associated histone enrichment sites upstream of cancer driver genes [25]. The experimental protocol included:

- Sample Preparation: Utilization of patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) from HPV+ HNSCC samples to maintain chromatin integrity comparable to primary tissue [25]

- Antibody Selection: Careful selection of histone marks including H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K9me3, and H3K27ac based on their strong implication in gene expression regulation, with H3K9me3 serving as a negative control [25]

- Validation: Comparison of RNA-seq gene expression profiles between PDX models and corresponding parental tissue, demonstrating high correlation (Pearson coefficients of 0.83 and 0.9, both p-values < 10−16) [25]

- Integration Method: Application of an Expression Variation Analysis (EVA) algorithm that models inter-tumor heterogeneity of epigenetic regulation of gene expression [25]

Advanced Integration Approaches

More sophisticated computational methods have emerged for integrating histone modification and gene expression data. GENet (Gene Expression Network from Histone and Transcription Factor Integration) represents a novel graph-based approach that integrates regulatory signals from transcription factors and histone modifications into a unified model [30]. This method extends beyond simple DNA sequence analysis by incorporating additional layers of genetic control vital for determining gene expression. The framework employs graph convolutional networks (GCNs) to handle classification tasks for each feature type, constructs weighted sample similarity networks using cosine similarity, and introduces a cross-feature discovery tensor that captures correlations between labels across different features [30].

Another advanced approach involves using chromatin state annotations to infer regulatory relationships. The Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium defined a 15-state chromatin model based on combinatorial patterns of histone modifications, which includes 8 active states and 7 repressed states that show distinct levels of DNA methylation, DNA accessibility, and correlation with gene expression [26]. These chromatin states enable researchers to identify potential regulatory elements and connect them to target genes based on proximity and correlation with expression patterns.

Figure 1: Integrated ChIP-seq and RNA-seq Analysis Workflow. This diagram illustrates the parallel processing of ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data culminating in integrated analysis for histone mark validation.

Research Reagent Solutions for Epigenomic Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Histone Mark Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Specification | Research Application | Consortium Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 Antibody | Active promoter marker | Identifying actively transcribed genes | Roadmap validated in 111 epigenomes [26] |

| H3K27ac Antibody | Active enhancer marker | Pinpointing active regulatory elements | Key feature in GENet model [30] |

| H3K27me3 Antibody | Polycomb repression marker | Detecting facultative heterochromatin | Core mark in chromatin state model [26] |

| H3K36me3 Antibody | Transcriptional elongation | Marking actively transcribed regions | Correlated with gene body methylation [26] |

| Cross-linking Reagents | Formaldehyde, DSG, EGS | DNA-protein crosslinking for ChIP | Standardized protocols in Roadmap [29] |

| Chromatin Shearing Kits | Sonicators, enzymatic kits | DNA fragmentation to optimal size | Fragment length estimation via cross-correlation [27] |

| Whole Cell Extract (WCE) | Input DNA control | Background signal normalization | Required for MACS2 peak calling [27] |

| Public Data Portals | Roadmap, ENCODE, Cistrome | Access to reference epigenomes | 150.21 billion mapped reads available [26] |

Analytical Frameworks and Statistical Considerations

Critical Parameter Choices in Data Processing

The analysis of ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data involves numerous analytical decisions that significantly impact downstream integration and interpretation. Key considerations include sequencing depth, replicate concordance, and normalization methods. The Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium addressed sequencing depth variability by subsampling all datasets to a consistent depth (30 million reads for histone marks), which prevents artificial differences in signal strength but may reduce sensitivity for lower-abundance marks [27]. For RNA-seq data, normalization approaches that account for library composition (e.g., TMM for cross-sample comparisons) are essential when integrating with histone mark data [31].

The selection of appropriate control datasets represents another critical consideration. The HPV+ HNSCC study highlighted the importance of carefully matched controls, utilizing UPPP samples from non-cancer patients with similar demographic and lifestyle characteristics to enable inference of tumor-specific differences in chromatin structure independent of tissue-specific effects [25]. This approach controls for confounding factors and strengthens conclusions about disease-associated epigenetic changes.

Machine Learning Approaches for Integration

Advanced machine learning techniques offer powerful approaches for integrating histone modification and gene expression data. The GENet framework demonstrates how graph-based models can leverage both the regulatory signals from histone modifications and the structural relationships among samples to improve gene expression prediction [30]. This method specifically utilizes H3K27ac marks combined with transcription factor binding information in a graph convolutional network architecture to capture complex regulatory relationships [30].

Other computational approaches include the use of random forests, support vector machines, and deep learning models like DeepChrome and AttentiveChrome, which use histone modification profiles to predict gene expression levels [30]. These methods face challenges including noise and inaccuracies in ChIP-seq data, ambiguous causality between histone marks and gene expression, and the need for context-specific models, but represent promising avenues for more sophisticated integration of multi-omics data [30].

Figure 2: Logical Relationships in Histone Mark Validation Framework. This diagram shows the interconnected components of a robust validation strategy combining public resources, experimental design, and computational analysis.

The data processing pipelines established by large-scale consortia like Roadmap Epigenomics provide standardized, high-quality resources for investigating relationships between histone modifications and gene expression. Their rigorous approaches to read mapping, peak calling, and data normalization create a solid foundation for validating histone marks against transcriptional outputs. The integrated analysis of ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data, when performed with careful attention to experimental design and statistical considerations, offers powerful insights into gene regulatory mechanisms relevant to both basic biology and drug development.

As computational methods continue to evolve, particularly with advances in graph-based models and deep learning approaches, researchers will gain increasingly sophisticated tools for extracting biological meaning from these complex datasets. By leveraging the standardized processing pipelines of major consortia while implementing robust analytical frameworks, scientists can effectively validate the functional significance of histone modifications in diverse biological and clinical contexts.

The regulation of gene expression is a fundamental process that enables cells with identical genomes to exhibit vastly different phenotypes. Central to this process are histone modifications (HMs), post-translational modifications to histone proteins that remodel chromatin structure and control transcriptional activity without altering the underlying DNA sequence [5] [32]. The "histone code" hypothesis suggests that combinations of these modifications encode regulatory information that controls gene expression patterns [33]. Aberrations in these combinatorial patterns have been linked to various diseases, including cancer, making them promising targets for epigenetic drugs and therapeutic interventions [32] [34].

The emergence of low-cost, high-throughput Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies has generated vast amounts of HM and gene expression data, creating opportunities for computational approaches to decipher this complex relationship [35] [32]. Early statistical methods and traditional machine learning models demonstrated correlations but struggled to capture the non-linear, combinatorial nature of histone codes. This limitation catalyzed the adoption of deep learning architectures, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and, more recently, transformer models, which have shown remarkable success in predicting gene expression from histone modification patterns [33] [36].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of CNN and transformer-based approaches, specifically focusing on the Chromoformer architecture, for predicting gene expression from histone modifications. We examine their performance, experimental methodologies, and applicability within research and drug development contexts, framed within the broader thesis of validating histone marks with gene expression data.

Model Architectures: From Local Features to Global Context

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

CNN-based approaches process histone modification signals as spatial data across genomic regions. These models typically take a fixed-size window around Transcription Start Sites (TSS), often 10,000 base pairs upstream and downstream, divided into 100 bins [36]. Each bin contains signal intensities for multiple histone marks (e.g., H3K4me3, H3K4me1, H3K27ac), creating a 2D input matrix resembling an image [36].

- Architecture Characteristics: CNNs employ convolutional layers with small receptive fields that excel at detecting local patterns and motifs in the histone modification signals [33]. Models like DeepChrome and its variants use this approach to learn position-invariant features that predict gene expression status [36]. However, a significant limitation is their difficulty in modeling long-range dependencies due to the gradual dilution of information through successive layers [33].

Transformer Models (Chromoformer)

Chromoformer represents a transformative approach that addresses key limitations of CNN-based models. Its design incorporates three specialized transformer modules that reflect the hierarchical nature of gene regulation [37] [33]:

- Embedding Transformer: Learns histone codes in the direct vicinity of TSS (up to 40 kbp), summarizing the epigenetic state of the promoter region [33].

- Pairwise Interaction Transformer: Uses an encoder-decoder framework to update promoter embeddings based on interactions with putative cis-regulatory elements (pCREs) [33].

- Regulation Transformer: Models the collective regulatory effect imposed by the complete set of 3D pairwise interactions [33].

A key innovation in Chromoformer is its incorporation of three-dimensional chromatin interaction data from promoter-capture Hi-C (pcHi-C) experiments, enabling the model to integrate information from distal regulatory elements that physically interact with promoters through chromatin folding [5] [33].

The following diagram illustrates Chromoformer's multi-level architecture for modeling hierarchical gene regulation:

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Assessment

Extensive benchmarking across multiple cell types and conditions reveals distinct performance differences between architectural approaches. The table below summarizes key quantitative comparisons based on experimental results from recent studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Models for Gene Expression Prediction from Histone Modifications

| Model Architecture | Key Features | Performance Metrics | Genomic Scope | Cell Types Tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-based (DeepChrome, AttentiveChrome) [36] | Local feature detection, Attention mechanisms | Average AUC: ~84.79% (TransferChrome) [36] | Narrow windows around TSS (typically 10kbp) [33] | 56 cell lines from REMC [36] |

| Transformer-based (Chromoformer) [33] | 3D chromatin interactions, Long-range dependencies | Superior performance to other deep learning models [33] | Wide genomic windows (40kbp) + distal pCREs [33] | 11 cell types from Roadmap Epigenomics [5] [37] |

| Interpretable Models (ShallowChrome) [32] | Logistic regression on peak-called features | Outperformed deep learning approaches in binary classification [32] | Dynamically chosen bins based on significance [32] | 56 cell types from REMC [32] |

Beyond overall accuracy, Chromoformer demonstrates particular advantages in modeling complex regulatory relationships. The incorporation of multi-scale embeddings (combining regulatory information at different resolutions) significantly boosts performance compared to using any single-resolution embedding [33]. Furthermore, Chromoformer adaptively utilizes long-range dependencies between histone modifications associated with transcription initiation and elongation, enabling it to capture quantitative kinetics of nuclear subdomains like transcription factories and Polycomb group bodies [33].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Collection and Preprocessing

Standardized data processing pipelines are crucial for reproducible model training and evaluation:

Data Sources: Most studies utilize histone modification and gene expression data from public consortiums like the Roadmap Epigenomics Project (REMC) and the ENCODE project [5] [36]. These resources provide ChIP-seq data for histone marks and RNA-seq data for gene expression across numerous cell types.

Histone Modification Processing: Raw ChIP-seq reads are typically subsampled to 30 million reads and truncated to 36 base pairs to reduce read length biases [5]. Alignments are processed using tools like Sambamba and Bedtools to derive read depths across the reference genome [5] [37]. Signals are then averaged and log2-transformed into fixed-sized bins (e.g., 100bp for promoters) [5].

Gene Expression Processing: RNA-seq data is normalized to Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads (RPKM) and log2-transformed [5]. For classification tasks, genes are typically assigned binary labels (active/inactive) based on whether their expression exceeds the median expression value across all genes in that cell type [32] [36].

3D Chromatin Data: Chromoformer incorporates promoter-capture Hi-C (pcHi-C) data to identify putative cis-regulatory elements (pCREs) interacting with each promoter [33]. Interaction frequencies are normalized and used to weight the influence of distal regions [37].

Model Training and Evaluation

Robust evaluation strategies are essential for meaningful performance comparisons:

Chromosomal Split: To prevent information leakage, genes are split into training and test sets based on chromosomes, ensuring no genes from the same chromosome appear in both sets [37].

Performance Metrics: For classification tasks (active/inactive genes), models are evaluated using Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve [36]. For regression tasks (predicting expression levels), correlation coefficients and error metrics are used [5].

Cross-Validation: Most studies employ k-fold cross-validation (typically 4-fold) with distinct chromosome splits, providing performance estimates across different genomic contexts [37].

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps in data processing and model training:

Successful implementation of these deep learning approaches requires both computational resources and biological datasets. The following table catalogues key solutions and their applications:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Histone Modification Analysis

| Resource Category | Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Epigenomic Data Resources | Roadmap Epigenomics Project [5] [36], ENCODE, BLUEPRINT consortium [23] | Provide standardized ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data across multiple cell types for model training and validation. |

| Chromatin Interaction Data | Promoter-capture Hi-C (pcHi-C) [33] | Maps 3D chromatin interactions between promoters and distal regulatory elements for incorporation in models like Chromoformer. |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Chromoformer [37], DeepChrome [36], ShallowChrome [32] | Pre-implemented models for gene expression prediction from histone modifications. |

| Data Processing Tools | Sambamba [5] [37], BedTools [5] [37], BEDTools [36] | Process raw sequencing data into analyzable formats for model input. |

| Chromatin State Models | ChromHMM [32] [23], Stacked Chromatin State Model [23] | Learn combinatorial patterns of epigenetic marks across individuals and genomic regions. |

| Histone Modification Detection | HiP-Frag (Mass Spectrometry) [34] | Identifies novel histone post-translational modifications beyond common marks. |

The comparative analysis of CNN and transformer architectures for predicting gene expression from histone modifications reveals a clear evolutionary trajectory in computational epigenomics. While CNN-based models like DeepChrome and AttentiveChrome provided initial breakthroughs in capturing local histone modification patterns, transformer-based architectures like Chromoformer represent a significant advance through their ability to model long-range dependencies and incorporate 3D chromatin interactions [33].

Several promising research directions are emerging. Transfer learning approaches show potential for improving cross-cell-line predictions, addressing the challenge of limited data for certain cell types [36]. The development of interpretable models like ShallowChrome demonstrates that high accuracy need not come at the expense of biological insight [32]. Furthermore, the identification of global patterns of epigenetic variation across individuals using stacked chromatin state models offers new frameworks for studying trans-regulators and complex diseases [23].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advanced deep learning models provide powerful tools for validating histone marks with gene expression data, identifying novel regulatory loci, and generating testable hypotheses about epigenetic mechanisms in health and disease. As these models continue to evolve, they promise to unlock new frontiers in precision medicine by making genomic insights more actionable and accelerating the development of epigenetic therapeutics.

In the field of epigenetics, histone modifications have emerged as crucial regulators of gene expression, forming a complex "histone code" that influences chromatin structure and transcriptional activity [38]. Genome-wide studies have revealed that active genes exhibit a characteristic binary pattern of histone modifications, being hyperacetylated for H3 and H4 and hypermethylated at Lys 4 and Lys 79 of H3, while inactive genes are hypomethylated and deacetylated at the same residues [38]. However, the sheer volume and complexity of histone modification data have made it challenging to extract predictive patterns that reliably correlate with gene expression states. This challenge has created an urgent need for sophisticated computational approaches that can navigate this multidimensional data landscape.