From Data to Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Methylation Level Heat Maps and Metagene Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on generating and interpreting methylation level heat maps and metagene profiles.

From Data to Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Methylation Level Heat Maps and Metagene Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on generating and interpreting methylation level heat maps and metagene profiles. It covers the foundational principles of DNA methylation as an epigenetic regulator, explores established and emerging methodologies from bisulfite sequencing to machine learning, and offers practical troubleshooting for experimental and computational challenges. The content also addresses the critical validation and comparative analysis needed to ensure biological relevance, synthesizing insights from recent technological advances to empower robust epigenetic analysis in disease research and therapeutic development.

The Essential Guide to DNA Methylation and Heat Map Visualization

DNA methylation, a fundamental epigenetic modification, involves the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of a cytosine residue, primarily within CpG dinucleotides, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [1]. This modification regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence and is mediated by an intricate system of enzymatic "writers," "erasers," and "readers" [2]. In the context of methylation profiling research, understanding these components is crucial for interpreting metagene analyses and heatmap data, as they represent the dynamic regulatory network that establishes, interprets, and maintains cellular methylation patterns across different genomic contexts. These patterns are cell-type-specific and highly stable, providing a molecular record of cellular identity and developmental history that can be visualized through epigenetic profiling techniques [3].

The DNA Methylation Machinery

Writers: Establishing Methylation Patterns

DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), known as "writers," catalyze the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) to cytosine bases [1] [4]. These enzymes work in a coordinated manner to establish and maintain methylation patterns through cell divisions.

Table 1: DNA Methylation Writers (DNMTs)

| Enzyme | Classification | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance methyltransferase | Copies methylation patterns during DNA replication | Preferentially recognizes hemi-methylated DNA; essential for preserving epigenetic memory [1] [5]. |

| DNMT3A/B | De novo methyltransferases | Establishes new methylation patterns | Sets up methylation during embryonic development and cellular differentiation; does not require hemi-methylated template [1] [4]. |

| DNMT3L | Regulatory co-factor | Stimulates de novo methylation | Lacks catalytic activity but enhances DNMT3A/B function; particularly important in germ cells [5]. |

Erasers: Removing Methylation Marks

DNA demethylation is catalyzed by "eraser" enzymes, primarily the ten-eleven translocation (TET) family, which initiate an oxidative pathway to remove methyl marks [4].

Table 2: DNA Methylation Erasers (TET Enzymes)

| Enzyme | Catalytic Activity | Resulting Products | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| TET1/2/3 | Oxidation of 5mC to 5hmC | 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) | Initiates active demethylation pathway; 5hmC also serves as a stable epigenetic mark with distinct regulatory functions [4]. |

| TET1/2/3 | Further oxidation of 5hmC | 5-formylcytosine (5fC), 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) | Creates intermediates that can be excised by base excision repair (BER) machinery, leading to complete demethylation [4]. |

Readers: Interpreting the Methylation Code

Methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins (MBDs) function as "readers" that recognize and interpret methylated DNA, recruiting additional protein complexes that influence chromatin structure and gene expression [1] [6].

Table 3: DNA Methylation Readers (MBD Proteins)

| Reader Protein | Domains | Recognition Specificity | Downstream Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| MeCP2 | MBD, TRD | Preferentially binds densely methylated CpGs | Recruits histone deacetylases (HDACs) and chromatin remodeling complexes; mutations cause Rett syndrome [6] [5]. |

| MBD1-4 | MBD | Binds methylated CpGs with varying affinities | Generally associated with transcriptional repression; MBD2 deficiency linked to immune dysfunction [1]. |

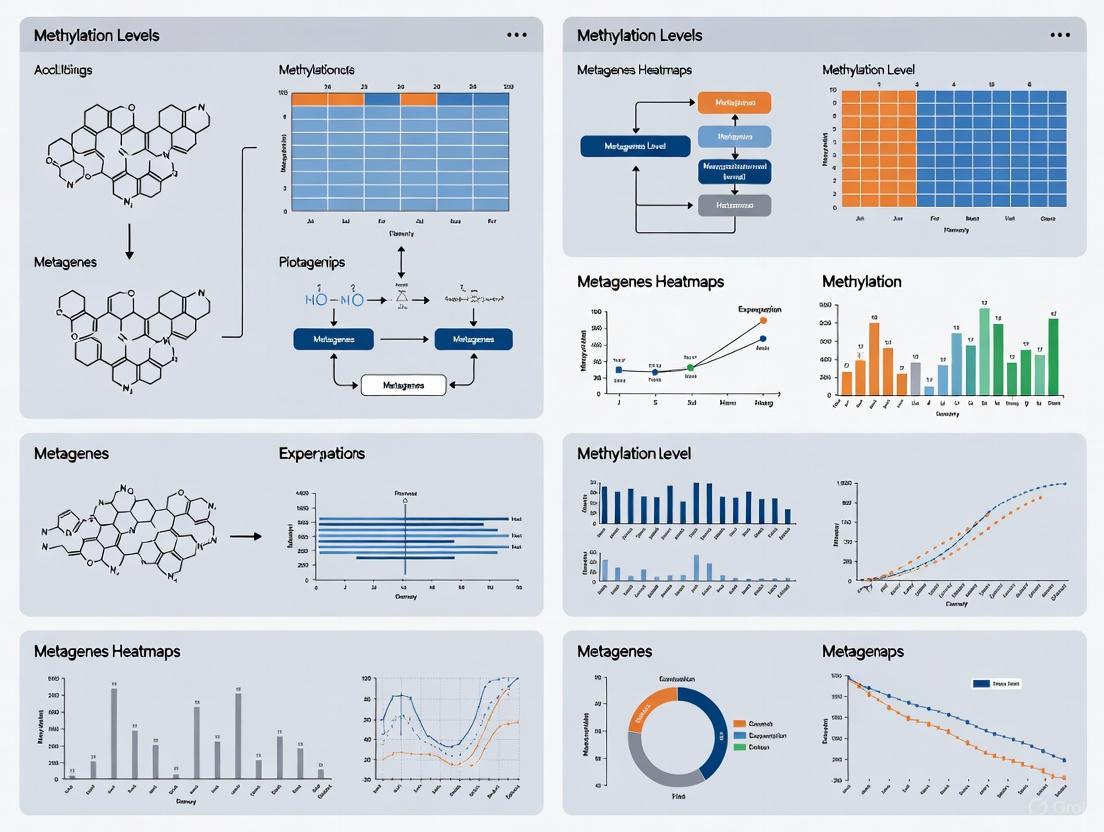

Figure 1: DNA Methylation Regulatory Network. This diagram illustrates the coordinated actions of writers (DNMTs), erasers (TET enzymes), and readers (MBD proteins) in establishing, removing, and interpreting DNA methylation marks, ultimately influencing chromatin structure and gene expression.

Functional Coupling in Methylation Regulation

The writers, erasers, and readers of DNA methylation do not function in isolation but exhibit sophisticated functional coupling that enables precise spatial and temporal control of epigenetic regulation [2]. Reader domains can be encoded within the same polypeptide as catalytic domains or present in associated protein partners, creating self-reinforcing regulatory loops [2].

Reader-Writer Coupling

Several methyltransferases contain embedded reader domains that recognize their catalytic products, creating positive feedback mechanisms. The H3K9 methyltransferase Clr4 contains an N-terminal chromodomain that recognizes H3K9me3, its catalytic product, facilitating efficient spreading of this mark across adjacent nucleosomes [2]. Similarly, the H3K9me1/2 methyltransferases G9a and GLP contain ankyrin repeat domains that bind their products (H3K9me1/2), increasing local enzyme concentration in methylated regions [2]. In the PRC2 complex, the EED subunit recognizes the H3K27me3 mark produced by EZH2, stimulating catalytic activity approximately 7-fold in a positive feedback loop [2].

Reader-Eraser Coupling

Demethylases also employ reader domains to regulate their activity and targeting. KDM4A and KDM4C demethylases contain double tudor domains that recognize H3K4me3, localizing them to active transcription start sites while they remove methylation from H3K9me3/2 [2]. KDM5A demethylases feature PHD domains where PHD3 recognizes the substrate (H3K4me3) while PHD1 binding to unmodified H3K4 allosterically stimulates catalytic activity by 30-fold on nucleosome substrates [2].

Experimental Methodologies for Methylation Profiling

Core Methylation Analysis Technologies

Comprehensive methylation profiling relies on multiple technological platforms, each with distinct advantages for specific research applications.

Table 4: DNA Methylation Analysis Methods

| Method | Resolution | Key Features | Applications in Profiling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | Gold standard; comprehensive genome-wide coverage; requires high sequencing depth | Discovery phase; identification of novel DMRs; base-resolution methylation maps [3] [4]. |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Single-base | Targets CpG-rich regions; cost-effective; covers ~85% of CpG islands | Large-scale epigenome studies; cancer biomarker discovery [4]. |

| Illumina Infinium BeadChip | Single CpG site | Interrogates predefined CpG sites (450K-850K); high throughput; cost-effective | Population studies; clinical biomarker validation; EWAS [7]. |

| Enzymatic Methyl-Seq (EM-seq) | Single-base | Uses enzymes instead of bisulfite; better DNA preservation | Liquid biopsies; samples with limited DNA input [8]. |

| Pyrosequencing | Quantitative | High quantitative accuracy; medium throughput | Validation of DMRs; targeted analysis of specific loci [7]. |

Integrated Workflow for Methylation-Expression Analysis

Figure 2: Integrated Methylation-Expression Analysis Workflow. This experimental pipeline outlines the key steps for combining DNA methylation and gene expression data to identify functionally relevant epigenetic regulation, culminating in metagene profiles and heatmap visualizations.

Protocol: Integrated Methylation and Gene Expression Analysis

This protocol outlines the methodology for identifying functional DNA methylation markers through integrated analysis, as demonstrated in follicular thyroid carcinoma research [7]:

Sample Preparation and Grouping

- Obtain 30 matched tissue samples (e.g., 14 FTC vs. 16 benign thyroid lesions)

- Divide into discovery (n=10) and validation sets (n=20)

- Ensure histopathological confirmation by experienced pathologist

Parallel Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Extract DNA using OMEGA TISSUE DNA Kit or similar

- Extract total RNA using RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit

- Quantify purity and concentration using spectrophotometry

Genome-Wide Methylation Profiling

- Treat 500ng DNA with bisulfite using EZ DNA Methylation Gold Kit

- Hybridize to Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip (850K sites)

- Scan arrays using iScan or similar system

- Process data using minfi R package with SWAN normalization

- Calculate β-values (0=unmethylated, 1=fully methylated)

- Identify DMSs with |Δβ| >0.1 and p<0.05

Gene Expression Profiling

- Amplify and label RNA using Affymetrix WT PLUS Reagent Kit

- Hybridize to Affymetrix Clariom S arrays

- Normalize data using Expression Console software

- Identify DEGs with fold change >2 or <0.5 and p<0.05

Integrative Bioinformatics Analysis

- Annotate DMSs to genes using Illumina manifest files

- Prioritize promoter and TSS-proximal DMSs

- Identify inverse methylation-expression correlations

- Select candidate loci with large |Δβ| and SNP distance >10bps

Technical Validation

- Design PCR and sequencing primers for candidate DMSs

- Perform bisulfite-pyrosequencing using PyroMark Q96 system

- Validate methylation patterns in independent sample set

Statistical Analysis and Visualization

- Perform unsupervised consensus clustering using pheatmap R package

- Conduct ROC analysis using pROC package to determine AUC values

- Generate metagene profiles and heatmaps for candidate markers

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for DNA Methylation Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Manufacturer | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| EZ DNA Methylation Gold Kit | Zymo Research | Bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines | Sample preparation for bisulfite sequencing; converts unmethylated C to U while preserving 5mC [7]. |

| Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip | Illumina | Genome-wide methylation array | Profiling ~850,000 CpG sites; ideal for discovery studies and biomarker validation [7]. |

| PyroMark Q96 System | Qiagen | Quantitative bisulfite pyrosequencing | Validation of differential methylation sites; provides high quantitative accuracy [7]. |

| RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit | Ambion | Simultaneous DNA/RNA extraction from FFPE | Integrated multi-omics from archival samples; maintains nucleic acid integrity [7]. |

| NuGEN Ovation FFPE WTA System | NuGEN | Whole transcriptome amplification from FFPE | Gene expression analysis from challenging samples; enables profiling from degraded RNA [7]. |

| Senecionine N-Oxide | Senecionine N-Oxide, CAS:13268-67-2, MF:C18H25NO6, MW:351.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Visnadine | Visnadine for Research | High-purity Visnadine for research applications. A natural vasodilator from Ammi visnaga. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

Integration with Methylation Profiling and Visualization

The functional relationships between writers, erasers, and readers directly inform the interpretation of methylation profiling data, particularly in metagene analyses and heatmap visualizations. Cell-type-specific methylation patterns, as identified in comprehensive methylome atlases, reflect the coordinated activity of this regulatory machinery [3]. When analyzing heatmaps of methylation data across sample groups, regions showing differential methylation frequently correspond to genomic loci where the balance of writer and eraser activity has been altered, with reader proteins subsequently recruiting effector complexes that establish transcriptionally permissive or repressive chromatin states.

Metagene profiles that show consistent methylation patterns across gene bodies typically reflect the activity of DNMT3A/B in establishing gene body methylation, which is frequently associated with moderately to highly expressed genes [9]. Promoter methylation changes, particularly at CpG islands, often indicate aberrant writer activity (DNMT overexpression) or impaired eraser function (TET deficiency), with profound transcriptional consequences. The integration of these methylation patterns with chromatin accessibility data and histone modification profiles provides a comprehensive view of the functional epigenetic landscape, enabling researchers to distinguish driver epigenetic events from passenger alterations in disease contexts.

Why Profile Methylation? Linking Epigenetic Marks to Disease and Development

DNA methylation, a fundamental epigenetic mechanism involving the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases, serves as a critical regulator of gene expression and cellular identity. This technical guide examines the compelling reasons for profiling methylation patterns, highlighting their indispensable role in deciphering developmental trajectories, identifying disease biomarkers, and advancing personalized medicine. We explore how methylation metagenes and heatmaps function as powerful analytical tools to visualize complex epigenetic data across biological contexts. With advancements in sequencing technologies, machine learning algorithms, and spatial profiling methods, methylation analysis has transformed from a basic research tool to a clinical asset for disease diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring. This whitepaper synthesizes current methodologies, applications, and experimental frameworks to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource for leveraging methylation profiling in both basic and translational research.

DNA methylation represents a stable epigenetic mark that regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. This covalent modification primarily occurs at cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, where DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) catalyze the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of cytosine rings, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC). The reverse process is facilitated by ten-eleven translocation (TET) family enzymes that oxidize 5mC as part of the demethylation pathway [4]. The dynamic balance between methylation and demethylation enables cells to maintain stable epigenetic states while retaining plasticity in response to developmental cues and environmental exposures.

Methylation profiling has emerged as an essential tool for investigating the epigenetic basis of cellular differentiation, disease pathogenesis, and therapeutic response. Unlike genetic mutations, which are largely static within an individual, epigenetic modifications exhibit tissue-specific patterns, reflect environmental influences, and offer dynamic insights into gene regulatory networks [10] [11]. The profiling of these marks enables researchers to identify epigenetic signatures associated with specific physiological or pathological states, providing a window into functional genomics beyond what DNA sequencing alone can reveal.

The stability and tissue-specificity of DNA methylation patterns make them particularly valuable for clinical applications. These epigenetic marks demonstrate remarkable consistency across biological replicates, with studies showing greater than 99.5% identity between the same cell types from different individuals [3]. This robustness, combined with the ability to detect methylation changes in liquid biopsies, positions methylation profiling as a powerful approach for non-invasive diagnostics and disease monitoring.

Key Applications in Development and Disease

Mapping Developmental Processes

Methylation profiling provides unprecedented insights into the epigenetic programming that guides normal development. During embryogenesis, precise methylation patterns are established that define cellular identities and maintain tissue-specific functions. Research demonstrates that these patterns record developmental history, with methylation signatures persisting from embryonic germ layers into adult tissues [3]. For instance, endoderm-derived cells maintain distinct methylation marks that differentiate them from mesoderm- or ectoderm-derived lineages, even in adulthood.

Advanced profiling technologies have enabled the construction of comprehensive methylation atlases across normal human cell types. These resources reveal how methylation patterns recapitulate lineage relationships between tissues, with unsupervised clustering of methylomes systematically grouping biologically related cell types regardless of their anatomical location or physiological function [3]. Such atlases provide essential references for understanding how developmental pathways are epigenetically encoded and how their dysregulation may contribute to congenital disorders.

Recent technological innovations now enable spatial joint profiling of DNA methylomes and transcriptomes within intact tissues, offering unprecedented insights into the interplay between epigenetic marks and gene expression during development. The spatial-DMT method allows researchers to simultaneously map methylation patterns and transcriptional activity at near single-cell resolution directly in tissue sections, preserving critical spatial context [12]. This approach has been successfully applied to mouse embryogenesis, revealing how methylation-mediated regulatory mechanisms operate within specific tissue microenvironments to guide developmental processes.

Disease Biomarker Discovery and Diagnosis

Methylation profiling has revolutionized disease biomarker discovery, particularly in oncology. Epigenetic alterations often represent early events in disease pathogenesis, making them ideal diagnostic markers. In prostate cancer, for example, specific methylation patterns in genes such as GSTP1 demonstrate exceptional diagnostic performance with an AUC of 0.939, significantly outperforming traditional biomarkers [13]. These epigenetic changes can be detected in liquid biopsies, offering non-invasive alternatives to tissue biopsies for cancer detection and monitoring.

The clinical utility of methylation biomarkers extends across diverse disease states:

Table 1: DNA Methylation Biomarkers in Disease Diagnosis

| Disease Area | Key Methylation Markers | Detection Method | Performance | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate Cancer | GSTP1, RASSF1A, CCND2 | Pyrosequencing, qMSP | AUC 0.937 (combined panel) | Tissue diagnosis, liquid biopsy [13] |

| Central Nervous System Cancers | Multi-locus classifier | Methylation array | Standardized >100 subtypes | Tumor classification [4] |

| Rare Genetic Disorders | Disease-specific episignatures | MethylationEPIC array | Clinical utility in genetics workflows | Blood-based diagnosis [4] |

Notably, epigenetic biomarkers offer significant advantages over genetic markers in disease susceptibility assessment. While genetic mutations from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) typically show at best 1% association with disease risk, epigenetic alterations from epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) demonstrate high-frequency associations of 90-95% among affected individuals [11]. This makes epigenetic markers particularly valuable for preventative medicine approaches aimed at identifying at-risk individuals before clinical symptom onset.

Prognostic Stratification and Therapy Monitoring

Beyond diagnosis, methylation profiling provides critical insights into disease prognosis and treatment response. Specific methylation signatures can stratify patients based on likely disease course, enabling more personalized management strategies. In cancer, these profiles help distinguish indolent from aggressive tumors, guiding decisions about treatment intensity and monitoring frequency.

The dynamic nature of epigenetic modifications makes them particularly suitable for monitoring therapeutic responses. Unlike genetic mutations, methylation patterns can change in response to treatment, providing measurable indicators of drug efficacy or resistance. Furthermore, because these modifications are reversible, they represent potential therapeutic targets themselves, with epigenetic drugs already in clinical use for certain hematological malignancies [10].

Methylation-based liquid biopsies show particular promise for monitoring minimal residual disease (MRD) and early detection of recurrence. Techniques such as enhanced linear splint adapter sequencing (ELSA-seq) enable sensitive detection of circulating tumor DNA methylation patterns, allowing for non-invasive surveillance of treatment response and disease recurrence [4]. This approach facilitates earlier intervention when recurrence occurs and reduces the need for invasive procedures during follow-up.

Analytical Approaches: Metagenes and Heatmaps

Methylation Metagenes as Analytical Constructs

The concept of "metagenes" in methylation analysis refers to computational constructs that aggregate methylation signals across biologically relevant genomic regions or gene sets. Rather than examining individual CpG sites in isolation, metagenes capture coordinated methylation patterns across functionally related regions, providing a more robust and biologically meaningful representation of epigenetic states.

Methylation metagenes are typically derived through several approaches:

Region-based metagenes combine methylation values across predefined genomic regions such as promoters, enhancers, or CpG islands. This approach acknowledges that methylation changes across functionally coordinated regions often have greater biological significance than isolated CpG changes.

Pathway-based metagenes aggregate methylation signals across genes involved in specific biological pathways, enabling assessment of epigenetic regulation at the pathway level rather than individual gene level.

Cell-type-specific metagenes represent methylation patterns characteristic of particular cell types, facilitating cellular deconvolution of complex tissues [3].

The analytical power of metagenes lies in their ability to reduce dimensionality while preserving biological signal, making them particularly valuable for visualizing complex methylation patterns across sample groups in heatmap representations.

Visualizing Methylation Patterns with Heatmaps

Heatmaps serve as essential tools for visualizing methylation data, enabling researchers to identify patterns, clusters, and outliers across multiple samples and genomic regions. When applied to methylation metagenes, heatmaps transform complex numerical data into intuitive color-coded representations that reveal sample relationships and epigenetic signatures.

Effective methylation heatmaps typically incorporate:

- Dendrograms showing hierarchical clustering of samples based on methylation similarity

- Color gradients representing methylation levels (commonly blue for hypomethylation, red for hypermethylation)

- Annotation tracks indicating sample attributes (e.g., disease status, tissue type, clinical variables)

- Genomic context information for the represented regions

In practice, heatmaps of methylation metagenes have revealed fundamental biological insights, such as the exceptional similarity of methylation patterns between biological replicates of the same cell type (>99.5% identity) compared to the substantial differences between cell types (4.9% variable blocks) [3]. This visualization approach powerfully demonstrates that methylation patterns are primarily determined by cell identity programs rather than individual genetic differences or environmental exposures.

Figure 1: Analytical workflow for methylation metagene and heatmap generation

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Methylation Detection Technologies

Multiple technological platforms are available for methylation profiling, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and optimal applications. Selection among these methods depends on factors including resolution requirements, sample type, budget constraints, and analytical goals.

Table 2: Comparison of DNA Methylation Detection Methods

| Method | Resolution | Throughput | DNA Input | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | High | Moderate | Comprehensive coverage; gold standard | DNA degradation; computational complexity [14] |

| Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq) | Single-base | High | Low | Preserves DNA integrity; reduced bias | Newer method; protocol optimization needed [14] |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) | Single-base | Moderate | High | Long reads; no conversion needed | Higher error rate; requires specialized equipment [14] |

| Illumina MethylationEPIC Array | Predefined CpG sites | Very High | Low | Cost-effective; standardized analysis | Limited to predefined sites; no novel discovery [14] |

| Spatial-DMT | Near single-cell | Moderate | N/A | Simultaneous methylome/transcriptome; spatial context | Complex protocol; emerging technology [12] |

Recent comparative studies demonstrate that EM-seq shows the highest concordance with WGBS, indicating strong reliability due to their similar sequencing chemistry, while ONT sequencing captures certain loci uniquely and enables methylation detection in challenging genomic regions [14]. Despite substantial overlap in CpG detection among methods, each technique identifies unique CpG sites, emphasizing their complementary nature in comprehensive methylation studies.

Spatial Joint Profiling Workflow

The innovative spatial-DMT method enables simultaneous profiling of DNA methylome and transcriptome from the same tissue section at near single-cell resolution. This protocol involves:

Tissue Preparation: Fresh frozen tissue sections are fixed and treated with HCl to disrupt nucleosome structures and improve Tn5 transposome accessibility.

Multi-round Tagmentation: Tn5 transposition inserts adapters with universal ligation linkers into genomic DNA. Two rounds of tagmentation balance DNA yield with experimental time while minimizing RNA degradation.

mRNA Capture: Biotinylated reverse transcription primers with UMIs capture mRNAs, followed by reverse transcription to synthesize cDNA.

Spatial Barcoding: Two sets of spatial barcodes flow perpendicularly in microfluidic channels, creating a two-dimensional grid of spatially barcoded tissue pixels.

Library Preparation: Barcoded gDNA and cDNA are separated after reverse crosslinking. cDNA undergoes template switching for library construction, while gDNA is processed with EM-seq conversion.

Sequencing and Analysis: High-throughput sequencing followed by computational processing generates spatially resolved methylation and expression maps [12].

This method has been successfully applied to mouse embryogenesis and postnatal brain development, generating high-quality data with 136,639-281,447 CpGs covered per pixel and detection of 23,822-28,695 genes per spatial map [12].

Computational and Machine Learning Approaches

Advanced computational methods are essential for extracting biological insights from complex methylation data. Machine learning algorithms have become particularly valuable for:

Disease Classification: Supervised methods including support vector machines, random forests, and gradient boosting have been employed for classification, prognosis, and feature selection across tens to hundreds of thousands of CpG sites [4].

Feature Selection: Algorithms identify the most informative CpG sites or regions for specific biological questions, reducing dimensionality while preserving predictive power.

Deep Learning Applications: Multilayer perceptrons and convolutional neural networks have been employed for tumor subtyping, tissue-of-origin classification, and survival risk evaluation [4].

Foundation Models: Transformer-based models like MethylGPT and CpGPT pretrained on extensive methylomes (e.g., >150,000 human methylomes) support imputation and prediction with physiologically interpretable focus on regulatory regions [4].

These computational approaches must account for technical artifacts including batch effects and platform discrepancies that require harmonization across arrays and sequencing platforms. Additionally, limited and imbalanced cohorts jeopardize generalizability, necessitating external validation across multiple sites for robust model development [4].

Figure 2: Computational workflow for methylation data analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful methylation profiling requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for epigenetic studies. The following table details essential components for methylation research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Methylation Profiling

| Category | Specific Examples | Purpose/Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Nanobind Tissue Big DNA Kit; DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | High-quality DNA preservation with maintained methylation patterns | Assess yield, fragment size, and purity (A260/280 ratio) [14] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation Kit | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracil | Optimize for complete conversion while minimizing DNA degradation [14] |

| Enzymatic Conversion Kits | EM-seq kits | Enzyme-based cytosine conversion preserving DNA integrity | Superior for degraded samples or low-input applications [14] |

| Methylation Arrays | Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 BeadChip | Interrogation of >935,000 CpG sites across the genome | Cost-effective for large cohort studies [14] |

| Library Prep Kits | Commercial WGBS, EM-seq library kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries from converted DNA | Consider compatibility with sequencing platform |

| Spatial Barcoding Reagents | Spatial-DMT barcodes (A1-A50, B1-B50) | Spatial indexing of genomic material in tissue sections | Requires microfluidic equipment for application [12] |

| Quality Control Assays | Qubit fluorometry, Bioanalyzer, Bisulfite Conversion Efficiency Assays | Assessment of DNA quantity, quality, and conversion efficiency | Critical for data reliability and interpretation |

| Data Analysis Tools | wgbstools, minfi, SeSAMe | Processing, normalization, and analysis of methylation data | Choose based on methodology and biological question [14] [3] |

| Zeaxanthin dipalmitate | Zeaxanthin dipalmitate, CAS:144-67-2, MF:C72H116O4, MW:1045.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Zerumbone | Zerumbone | Bench Chemicals |

Methylation profiling represents an indispensable approach for linking epigenetic marks to developmental processes and disease mechanisms. The stability, tissue-specificity, and dynamic nature of DNA methylation patterns provide unique insights into gene regulatory networks that cannot be captured through genomic analysis alone. With advancing technologies including enzymatic conversion methods, long-read sequencing, and spatial multi-omics approaches, researchers now have unprecedented capability to map the epigenetic landscape at single-base resolution within native tissue contexts.

The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence with methylation data has further enhanced our ability to extract biologically and clinically meaningful patterns from these complex datasets. As evidenced by the growing number of methylation-based classifiers entering clinical practice, these epigenetic marks are transitioning from research tools to clinical assets for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring.

For researchers and drug development professionals, methylation profiling offers powerful opportunities to understand disease mechanisms, identify novel therapeutic targets, and develop biomarkers for personalized medicine approaches. The continuing evolution of methylation profiling technologies promises to further illuminate the epigenetic underpinnings of development and disease, opening new frontiers in both basic research and clinical application.

DNA methylation represents a fundamental epigenetic mechanism regulating gene expression and cellular function, with profound implications in cancer development and therapeutic interventions. The analysis of methylation patterns has evolved from single-gene investigations to genome-wide profiling, creating a critical need for advanced bioinformatic strategies to interpret complex epigenetic landscapes. This technical guide explores the integration of metagene concepts and heatmap visualization as a powerful framework for reducing dimensionality and extracting biologically meaningful patterns from high-throughput methylation data. By synthesizing current methodologies, from established Bioconductor packages to emerging machine learning applications, this review provides researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for transforming raw methylation data into actionable insights, thereby advancing precision medicine in oncology and genetic disease research.

DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to the cytosine ring within CpG dinucleotides, primarily occurring in CpG islands, and is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) [4]. This epigenetic modification serves as a critical regulator of gene expression, playing essential roles in embryonic development, genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, and maintaining chromosomal stability [4]. The dynamic balance between methylation (mediated by "writer" enzymes) and demethylation (facilitated by "eraser" enzymes like the TET family) is crucial for cellular differentiation and response to environmental changes [4].

In cancer and various genetic disorders, aberrant DNA methylation patterns drive disease pathogenesis by altering normal gene expression programs. Methylation profiling has therefore emerged as a powerful diagnostic and prognostic tool, with applications spanning cancer classification, neurodevelopmental disorders, and multifactorial diseases [4]. The emergence of high-throughput technologies has generated vast amounts of methylation data, creating both opportunities and challenges for researchers seeking to extract meaningful biological insights from these complex datasets.

The Analytical Challenge: From Single CpGs to Regional Patterns

Traditional methylation analysis often focuses on individual CpG sites, but evidence increasingly demonstrates that regional coordination of methylation states carries greater functional significance than isolated measurements [15]. This recognition has driven the development of metagene approaches that aggregate methylation signals across functionally or genetically related regions, allowing researchers to identify broader epigenetic patterns that might be missed when examining individual CpGs.

The concept of metagenes in methylation analysis represents a strategic framework for dimensionality reduction that groups multiple CpG sites into biologically meaningful units. These units may correspond to promoter regions, gene bodies, CpG islands, or other genomic features with potential regulatory significance. By analyzing methylation patterns at this aggregated level, researchers can overcome the analytical noise inherent in single-site measurements while capturing the coordinated nature of epigenetic regulation.

Data Generation: Methylation Profiling Technologies

Multiple technologies have been developed for DNA methylation profiling, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and applications in epigenetic research:

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Methylation Detection Techniques

| Technique | Key Features | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Comprehensive, single-base resolution | Detailed methylation mapping across the genome | High cost, computationally intensive [4] |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Cost-effective, targets CpG-rich regions | Methylation profiling in specific genomic regions | Limited genome coverage [4] |

| Infinium Methylation BeadChip | Interrogates >450,000 or >850,000 CpG sites | Population-scale epigenome-wide association studies | Limited to predefined CpG sites [4] [16] |

| Nanopore Sequencing | Direct detection of modified bases, long reads | Detection of 5-methylcytosine without bisulfite conversion | Higher error rates require specialized tools like NanoMethViz [17] |

| Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) | Enriches methylated DNA fragments via immunoprecipitation | Genome-wide methylation studies | Lower resolution, depends on antibody quality [4] |

The choice of technology significantly influences downstream analytical approaches, with array-based methods (e.g., Illumina Infinium BeadChips) dominating clinical applications due to their cost-effectiveness and standardized processing pipelines, while sequencing-based methods (e.g., WGBS, RRBS) offer greater flexibility for novel discovery in research settings [4].

Analytical Workflow: From Raw Data to Biological Insight

The transformation of raw methylation data into interpretable metagene representations and heatmap visualizations follows a structured computational pipeline. The workflow below outlines the key stages in this process:

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

The initial processing of methylation data requires careful attention to technical artifacts that can confound biological interpretation. For array-based data, this typically involves:

- Quality assessment using metrics like detection p-values to identify failed probes or samples [16]

- Normalization to correct for technical variation between arrays using methods such as SSNoob (SeSAMe) or functional normalization (minfi) [16]

- Batch effect correction to address non-biological technical variations that can introduce spurious patterns [4]

For sequencing-based approaches, the preprocessing pipeline includes:

- Adapter trimming and quality filtering of raw reads

- Alignment to bisulfite-converted reference genomes using tools like Bismark or BWA-meth

- Methylation calling to calculate beta values (methylation ratios) at each CpG site [18]

Specialized tools like MethVisual perform critical quality control steps specific to bisulfite sequencing data, including alignment verification and bisulfite conversion efficiency calculation to identify potential experimental artifacts [19].

Metagene Construction Strategies

The core analytical challenge in metagene analysis lies in defining meaningful aggregation units that capture biologically relevant methylation patterns. Several approaches have emerged:

Genomic Feature-Based Metagenes

This approach groups CpG sites based on their genomic context:

- Promoter metagenes: CpG sites within defined regions upstream of transcription start sites

- Gene body metagenes: CpGs within transcribed regions, often showing different regulatory patterns

- CpG island metagenes: Aggregations based on CpG density and relationship to islands, shores, and shelves

Data-Driven Metagenes

Unsupervised methods identify metagenes based on correlation patterns in the data itself:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Linear transformation that identifies directions of maximum variance [20]

- Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF): Decomposes the methylation matrix into additive components

- Clustering-based approaches: Group CpG sites with similar methylation patterns across samples

The NanoMethViz package exemplifies specialized approaches for long-read methylation data, enabling visualization of methylation patterns across genetically defined features by scaling them to relative positions and aggregating their profiles [17].

Dimensionality Reduction for Pattern Recognition

High-dimensional methylation data presents the "curse of dimensionality," where the number of features (CpG sites) vastly exceeds the number of samples. Dimensionality reduction techniques address this challenge through:

Feature Extraction Methods:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Linear transformation that identifies orthogonal directions of maximum variance [20]

- t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE): Non-linear method particularly effective at preserving local structure [20]

- Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP): Balances preservation of local and global structure with computational efficiency [20]

Feature Selection Methods:

- Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE): Iteratively removes the least important features [20]

- ReliefF: Weights features based on their ability to distinguish between neighboring samples [20]

- Information Gain: Selects features with the highest mutual information with class labels [20]

These techniques enable researchers to project high-dimensional methylation data into lower-dimensional spaces where biological patterns become more apparent, facilitating both visualization and downstream analysis.

Visualization Approaches: Heat Maps and Beyond

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting complex methylation patterns and communicating findings. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between various visualization approaches:

Heatmap Visualization for Methylation Patterns

Heatmaps represent one of the most powerful and widely used visualization techniques in methylation analysis, displaying quantitative data as a matrix of colored cells where colors correspond to methylation values (typically beta values from 0 to 1). Effective heatmap implementation requires:

Data Arrangement Strategies:

- Unsupervised clustering: Samples and CpG sites are rearranged based on similarity patterns using hierarchical clustering

- Supervised grouping: Samples are ordered according to known clinical or biological groups

- Genomic coordinates: CpG sites are arranged according to their chromosomal positions

Visual Encoding Considerations:

- Color scales: Continuous gradients (e.g., white to blue) representing unmethylated to methylated states

- Annotation tracks: Additional bars indicating sample attributes (e.g., disease status, tissue type)

- Dendrograms: Tree structures showing clustering relationships between samples or features

Tools like Methylation plotter provide interactive heatmap visualization with various sorting options, including by overall methylation level, by group, or by unsupervised clustering, enabling researchers to dynamically explore their data [15].

Specialized Visualization Techniques

Beyond conventional heatmaps, several specialized visualization approaches address specific analytical needs:

Lollipop Plots: These visualizations represent individual CpG sites as lines with circles indicating methylation status, providing intuitive display of methylation patterns across multiple clones or samples [19] [15]. MethVisual implements lollipop visualization specifically for bisulfite sequencing data, allowing researchers to examine methylation patterns at nucleotide resolution [19].

Regional Aggregation Plots: Tools like NanoMethViz enable visualization of methylation profiles across genomic features by scaling them to relative positions and aggregating patterns across multiple features [17]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying methylation trends associated with specific genomic elements.

Multi-Omics Integration Visualization: Web applications like the SMART App provide integrated visualization of methylation data in relation to genomic location, gene expression, and clinical annotations, enabling multidimensional exploration of epigenetic relationships [21].

The field of DNA methylation analysis is supported by a rich ecosystem of computational tools and databases. The following table summarizes key resources for metagene and heatmap analysis:

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Methylation Analysis

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MethVisual | Visualization & exploratory analysis | Lollipop plots, co-occurrence display, clustering | Bisulfite sequencing data [19] |

| RnBeads | Comprehensive methylation analysis | Quality control, preprocessing, DMR identification, visualization | Illumina arrays, BS-seq [18] |

| methylKit | Methylation analysis | Differential methylation, annotation, visualization | High-throughput bisulfite sequencing [18] |

| ChAMP | Methylation analysis pipeline | Quality control, normalization, DMR detection | Illumina Infinium arrays [18] [16] |

| minfi | Methylation array analysis | Preprocessing, normalization, differential methylation | Illumina Infinium arrays [16] |

| NanoMethViz | Long-read methylation visualization | Spaghetti plots, regional aggregation, dimensionality reduction | Nanopore sequencing data [17] |

| Methylation Plotter | Web-based visualization | Interactive lollipop plots, heatmaps, statistical summaries | Array and bisulfite sequencing data [15] |

| SMART App | Interactive analysis portal | Multi-omics integration, survival analysis, differential methylation | TCGA data exploration [21] |

| Qlucore Omics Explorer | Visualization-based analysis | PCA plots, heatmaps, statistical filtering | Various methylation data types [22] |

Experimental Design Considerations

Effective methylation analysis begins with appropriate experimental design:

Sample Size and Power:

- Larger sample sizes improve detection of subtle methylation differences

- Balanced group sizes reduce potential biases in differential methylation analysis

- Replication strategies (technical and biological) help distinguish true signals from artifacts

Platform Selection Criteria:

- Illumina Infinium arrays offer cost-effectiveness for large cohort studies [16]

- WGBS provides comprehensive coverage for novel discovery [4]

- Targeted approaches (RRBS, bisulfite capture) balance depth and cost for specific genomic regions [4]

Confounding Factors:

- Cell type heterogeneity can be addressed with reference-based or reference-free deconvolution methods

- Batch effects should be minimized through randomization and recorded for statistical adjustment

- Sample quality metrics (e.g., bisulfite conversion efficiency) must be monitored throughout processing

Machine Learning in Methylation Analysis

Machine learning (ML) approaches have revolutionized methylation analysis by enabling pattern recognition in high-dimensional datasets and providing predictive models for clinical applications.

Conventional Machine Learning Approaches

Traditional ML methods have proven effective for various methylation analysis tasks:

Supervised Learning:

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): Effective for sample classification based on methylation profiles [20]

- Random Forests: Handle high-dimensional data well and provide feature importance measures [4]

- Regularized Regression: (Lasso, Ridge) performs variable selection while modeling outcomes [4]

Unsupervised Learning:

- Hierarchical Clustering: Identifies sample subgroups and co-methylated CpG regions [20]

- K-means Clustering: Groups samples or features into distinct methylation subtypes [20]

- Biclustering: Simultaneously clusters samples and CpG sites to identify localized patterns [19]

These conventional approaches serve as the foundation for creating tools applicable to clinical settings, with AutoML (Automated Machine Learning) streamlining model development processes [4].

Deep Learning and Emerging Approaches

Recent advances in deep learning have expanded the analytical capabilities for methylation data:

Neural Network Architectures:

- Multilayer Perceptrons: Capture nonlinear interactions between CpG sites [4]

- Convolutional Neural Networks: Model spatial relationships in methylation patterns [4]

- Transformer-based Models: (e.g., MethylGPT, CpGPT) enable pretraining on large methylome datasets followed by fine-tuning for specific applications [4]

Emerging Paradigms:

- Foundation Models: Pretrained on extensive methylation datasets (e.g., >150,000 human methylomes) for transfer learning [4]

- Multi-Omics Integration: Combining methylation data with genomic, transcriptomic, and clinical variables [21]

- Agentic AI Systems: Combining large language models with computational tools to orchestrate comprehensive bioinformatics workflows [4]

These advanced approaches demonstrate particular strength in capturing nonlinear interactions between CpGs and genomic context directly from data, potentially revealing novel biological insights that might be missed by traditional methods.

Clinical Applications and Translational Implications

The integration of metagene approaches and visualization techniques has enabled significant advances in clinical research and diagnostic applications:

Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers

Methylation-based classifiers have demonstrated clinical utility across various medical contexts:

- Central nervous system tumors: DNA methylation-based classifiers standardized diagnoses across over 100 subtypes and altered histopathologic diagnosis in approximately 12% of prospective cases [4]

- Rare diseases: Genome-wide episignature analysis correlates patient blood methylation profiles with disease-specific signatures, demonstrating clinical utility in genetics workflows [4]

- Liquid biopsy: Targeted methylation assays combined with machine learning enable early cancer detection from plasma cell-free DNA with excellent specificity and accurate tissue-of-origin prediction [4]

Therapeutic Implications

Methylation patterns provide insights with direct therapeutic relevance:

- Drug response prediction: Methylation signatures can predict sensitivity to specific chemotherapeutic agents and targeted therapies

- Epigenetic therapy monitoring: Changes in methylation patterns following treatment with DNMT inhibitors can be tracked using metagene approaches

- Disease subtyping: Identification of distinct methylation subtypes enables more targeted therapeutic approaches

The SMART App facilitates exploration of clinical correlations by integrating methylation data with survival outcomes and treatment response information, allowing researchers to identify methylation markers with prognostic significance [21].

Future Directions and Challenges

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in the visualization and analysis of complex methylation landscapes:

Analytical Challenges

Technical Variability:

- Batch effects and platform discrepancies require harmonization across different technologies and laboratories [4]

- Limited and imbalanced cohorts in rare diseases jeopardize generalizability, necessitating external validation across multiple sites [4]

Interpretation Limitations:

- Model explainability: Many deep learning models lack transparent explanation mechanisms, limiting confidence in regulated clinical environments [4]

- Biological validation: Computational findings require experimental confirmation through targeted assays

Emerging Opportunities

Single-Cell Methylation Profiling: Emerging technologies for single-cell methylation profiling reveal methylation heterogeneity at the cellular level, offering unprecedented insights into cellular dynamics and disease mechanisms [4]. These approaches require specialized analytical methods to address sparsity and technical noise.

Multi-Omics Integration: The simultaneous analysis of methylation data with other molecular profiles (transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic) provides systems-level understanding of epigenetic regulation [21]. Tools like the SMART App represent early approaches to this integration, but more sophisticated methods are needed.

Real-Time Clinical Decision Support: Translation of methylation-based classifiers into routine clinical practice requires development of robust, validated, and regulatory-approved platforms that provide intuitive visualization for clinical stakeholders [4].

The integration of metagene concepts with heatmap visualization represents a powerful paradigm for extracting biological meaning from complex methylation data. By aggregating signals across functionally related genomic regions and displaying patterns in an intuitive visual format, researchers can identify coordinated epigenetic events that might be missed in single-CpG analyses. The continuously evolving toolkit of computational methods, from established Bioconductor packages to emerging machine learning approaches, provides researchers with increasingly sophisticated capabilities for methylation pattern discovery.

As methylation profiling technologies continue to advance and computational methods become more accessible, the integration of these approaches into standard research practice promises to accelerate epigenetic discovery and translation into clinical applications. The ongoing development of user-friendly tools that bridge the gap between computational experts and biological researchers will be crucial for realizing the full potential of methylation analysis in understanding disease mechanisms and advancing precision medicine.

Core Principles of Hierarchical Clustering in Heat Map Analysis

Heat maps, combined with hierarchical clustering, represent a powerful data visualization technique widely used in bioinformatics to reveal patterns, relationships, and structures within complex datasets [23] [24]. In methylation level analysis, this approach enables researchers to summarize methylation patterns across multiple samples and genomic regions in a single, intuitive graphical representation [25]. The cluster heat map extends beyond basic matrix shading by permuting rows and columns to uncover inherent structures in the data, providing insights that might otherwise remain hidden in raw numerical data [24].

The fundamental concept behind hierarchical clustering in heat map analysis involves organizing both features (such as CpG sites or promoter regions) and samples according to their similarity in methylation patterns [25]. This dual clustering approach reveals natural groupings in the data that may correspond to biologically or clinically significant categories, such as different disease subtypes or responses to treatment [26]. In epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS), this technique has become indispensable for handling the complexity of data generated from microarray technologies that measure DNA methylation at hundreds of thousands of CpG sites [27].

Mathematical Foundations of Hierarchical Clustering

Distance Metrics

The first critical step in hierarchical clustering involves calculating distances between data points to quantify their dissimilarity. Different distance metrics capture distinct aspects of data relationships, and the choice of metric significantly impacts the resulting cluster structure [23] [25].

Table 1: Distance Metrics for Hierarchical Clustering

| Metric | Calculation | Applications | Advantages | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euclidean | Square root of the sum of squared differences between coordinates [25] | General-purpose clustering; assumes data is on same scale [23] | Straightforward "as-the-crow-flies" distance [23] | ||

| Manhattan | Sum of absolute differences between coordinates [25] | Robust to outliers; data with different scales [23] | Less sensitive to extreme values than Euclidean [23] | ||

| 1 - Pearson Correlation | 1 - | r | , where r is the correlation coefficient between two profiles [25] | Identifying patterns with similar shapes but different magnitudes [23] | Focuses on profile similarity rather than absolute values [25] |

The mathematical formulation for these distance metrics is as follows. For two points, x and y, in n-dimensional space:

- Euclidean distance:

d(x,y) = √Σ(x_i - y_i)²[25] - Manhattan distance:

d(x,y) = Σ|x_i - y_i|[25] - Pearson correlation distance:

d(x,y) = 1 - |r|, wherer = Σ(x_i - x̄)(y_i - ȳ) / √Σ(x_i - x̄)²Σ(y_i - ȳ)²[25]

In methylation analysis, the Pearson correlation distance is particularly valuable for identifying genes with similar methylation patterns across samples, even if their absolute methylation levels differ [23].

Linkage Methods

After establishing pairwise distances between individual data points, linkage methods determine how to compute distances between clusters as they are progressively merged [23] [24]. The choice of linkage method significantly influences the structure of the resulting dendrogram and the composition of clusters [25].

Table 2: Linkage Methods in Hierarchical Clustering

| Method | Cluster Distance Definition | Cluster Characteristics | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete | Maximum distance between elements of the two clusters [25] | Compact, similarly sized clusters [23] | Default method; creates balanced clusters [23] |

| Single | Minimum distance between elements of the two clusters [23] [25] | Elongated clusters; "chaining" effect [23] | Identifying connected structures rather than dense clusters |

| Average | Mean distance between all pairs of elements in the two clusters [23] [25] | Balanced approach between complete and single [23] | General-purpose clustering [25] |

The hierarchical clustering algorithm proceeds recursively through the following steps [25]:

- Begin with each data point as its own cluster

- Calculate pairwise distances between all clusters using the chosen distance metric

- Merge the two closest clusters into a new cluster

- Recalculate distances between the new cluster and all remaining clusters according to the linkage method

- Repeat steps 2-4 until all points belong to a single cluster

This process creates a hierarchical tree structure known as a dendrogram, which visually represents the sequence of merges and the dissimilarity levels at which they occur [23] [24].

Experimental Design and Data Preparation for Methylation Analysis

Data Quality Control and Preprocessing

Proper data preparation is essential for generating meaningful methylation heat maps. The initial preprocessing phase involves several critical quality control steps to ensure data reliability [27]. For methylation level analysis, β-values are typically calculated as the ratio of methylated signal intensity to the sum of methylated and unmethylated signals (β = intensitymethylated / (intensitymethylated + intensity_unmethylated)) [27]. These β-values range from 0 (completely unmethylated) to 1 (completely methylated).

In bisulfite sequencing data, a critical quality control step involves setting a minimum coverage threshold for CpG sites [25]. Sites with coverage below this threshold (commonly 30 reads) are typically excluded from analysis or considered uninformative, as low coverage can lead to unreliable methylation estimates [25]. For targets containing multiple CpG sites, methylation levels are averaged across all informative sites to generate a representative value for the region [25].

Data normalization is another crucial preprocessing step, particularly when integrating data from multiple samples or experimental batches. While specific normalization methods may vary depending on the technology platform (e.g., Illumina Infinium BeadChips or bisulfite sequencing), the goal remains consistent: to remove technical artifacts while preserving biological signals [27]. For microarray-based methylation data, this often involves adjusting for cell type proportions and other potential confounders such as sex, gestational age, ethnicity, and obesity [27].

Feature Selection for Methylation Heat Maps

In methylation analysis, the number of potential features (CpG sites or genomic regions) can be enormous—ranging from 485,000 sites on the Illumina HumanMethylation450 BeadChip to over 850,000 on the EPIC array [27]. Effective feature selection is therefore essential for creating interpretable heat maps that highlight the most biologically relevant patterns.

Several filtering approaches can be employed to select features for inclusion in methylation heat maps [25]:

- Statistical filtering: Selecting features based on p-values and fold-change thresholds from differential methylation analysis

- Dispersion-based filtering: Retaining features with the highest index of dispersion (variance-to-mean ratio)

- Targeted selection: Focusing on specific genomic regions or CpG sites of prior biological interest

- Multi-trait analyses: Identifying features associated with multiple traits or outcomes of interest

In EWAS analyzing associations between DNA methylation and chemical exposures, researchers often face the challenge of sifting through large numbers of results, making feature selection particularly important for generating focused, interpretable visualizations [27].

Implementation of Hierarchical Clustering in Methylation Heat Maps

Computational Workflow

The implementation of hierarchical clustering in methylation heat map analysis follows a structured computational pipeline. This workflow can be executed using various bioinformatics tools, including R packages like pheatmap, specialized epigenetics software such as EpiVisR, or commercial solutions like QIAGEN's Biomedical Genomics Analysis [23] [27] [25].

The computational implementation involves both row-wise clustering (typically across genomic features) and column-wise clustering (across samples) [23]. For datasets with up to 5000 features, hierarchical clustering is generally performed in both dimensions, though computational constraints may require alternative approaches for larger datasets [25]. The result is a comprehensive visualization that groups similar features and similar samples together, facilitating the identification of methylation patterns associated with specific sample characteristics.

Color Scheme Selection for Methylation Visualization

The color scheme in a heat map is not merely an aesthetic choice—it fundamentally influences how patterns are perceived and interpreted [28]. Two primary types of color scales are used in methylation heat maps:

Sequential scales: Progress from light to dark shades of a single hue (or multiple hues progressing in one direction), representing low to high values [28]. These are ideal for displaying raw methylation β-values (which range from 0 to 1) or TPM values in gene expression data [28].

Diverging scales: Progress in two directions from a neutral central color, with two different hues representing extremes in opposite directions [28]. These are particularly useful for displaying standardized methylation values that include both hypermethylated and hypomethylated states, as they effectively highlight deviations from a reference value (such as zero or an average) [28].

Critical considerations for color scheme selection include:

- Color-blind accessibility: Approximately 5% of the population has color vision deficiency [28]. Avoid problematic color combinations like red-green, green-brown, green-blue, blue-gray, blue-purple, green-gray, and green-black [28]. Recommended accessible combinations include blue & orange, blue & red, and blue & brown [28].

- Perceptual uniformity: The "rainbow" scale should be avoided as it creates misperceptions of data magnitude [28]. Abrupt changes between different hues (e.g., green to yellow or blue to green) can make values appear significantly more different than they actually are [28].

- Simplicity: Overly complex color schemes with too many hues can create "colorful mosaics" that are difficult to interpret [28]. The best option is typically to select 3 consecutive hues on a basic color wheel [28].

Interpretation of Methylation Cluster Heat Maps

Analyzing Dendrogram Structure and Cluster Patterns

The interpretation of methylation cluster heat maps requires careful examination of both the dendrogram structure and the color patterns within the heat map itself [23]. The dendrogram (tree diagram) illustrates the hierarchical relationships between features or samples, with branch lengths representing the degree of dissimilarity between clusters [23] [24]. Shorter branches indicate higher similarity, while longer branches suggest greater divergence.

When interpreting methylation heat maps, several key patterns should be considered:

- Sample clustering: Groups of samples that cluster together may share biological characteristics, such as disease status, exposure history, or response to treatment [26]. In SCLC analysis, for example, distinct methylation patterns have been observed between current and former smokers, suggesting potential biomarkers for patient stratification [26].

- Feature clustering: Genomic regions that cluster together may be co-regulated or functionally related [24]. In embryogenesis studies, spatial methylation patterns have revealed coordinated epigenetic regulation during development [12].

- Methylation domains: Large blocks of similarly methylated regions may correspond to chromatin states or topological associating domains, providing insights into higher-order genome organization [12].

Integration with Complementary Data Types

A significant advantage of modern methylation analysis lies in integrating methylation heat maps with other data types to gain comprehensive biological insights [12] [27]. Spatial-DMT technology, for instance, enables joint profiling of DNA methylome and transcriptome from the same tissue section, revealing spatial relationships between epigenetic regulation and gene expression [12].

Tools like EpiVisR further facilitate integrated analysis by enabling visualization of relationships between methylation patterns, trait data, and gene expression [27]. This integrated approach can reveal biologically significant patterns that might be missed when examining methylation data in isolation, such as:

- Inverse relationships: Regions where hypermethylation in promoter regions corresponds with downregulation of associated genes

- Tissue-specific patterns: Methylation signatures that distinguish different tissue types or developmental stages

- Environmental influences: Methylation changes associated with specific exposures or lifestyle factors

In SCLC research, integrated analysis of methylation and gene expression data has identified specific genes (including SOD3, CBX7, RORC, ABHD14A, NDUFV1, LGALS, and PLD4) that show both methylation changes and differential expression, suggesting potential mechanistic roles in cancer development [26].

Research Reagent Solutions for Methylation Heat Map Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Methylation Heat Map Analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microarray Platforms | Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (~485,000 CpG sites) [27] | Genome-wide methylation profiling | Epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) [27] |

| Illumina MethylationEPIC BeadChip (~850,000 CpG sites) [27] | Expanded coverage methylation profiling | More comprehensive EWAS [27] | |

| Spatial Profiling Technology | Spatial-DMT (Spatial joint DNA Methylome and Transcriptome) [12] | Simultaneous spatial profiling of methylation and gene expression | Mouse embryogenesis, postnatal brain development [12] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | EpiVisR [27] | Interactive visualization of EWAS results | Trait-methylation relationship analysis [27] |

| pheatmap R package [23] | Creation of publication-quality heat maps | General-purpose heat map visualization [23] | |

| QIAGEN Create Methylation Level Heat Map tool [25] | Specialized methylation heat map generation | Bisulfite sequencing data analysis [25] | |

| Analysis Pipelines | meffil [27] | EWAS model calculation with cell type adjustment | Methylation data preprocessing and quality control [27] |

| Hierarchical clustering with complete, average, or single linkage [23] [25] | Identifying patterns in methylation data | Sample and feature clustering [23] |

Hierarchical clustering remains a cornerstone technique for heat map visualization in methylation analysis, providing powerful capabilities for pattern discovery and data exploration in epigenetics research. The method's effectiveness depends on appropriate selection of distance metrics, linkage methods, and color schemes tailored to the specific characteristics of methylation data. As methylation profiling technologies continue to advance—with increasing coverage, single-cell resolution, and spatial context—the importance of sophisticated visualization approaches like hierarchical clustering will only grow. By following the core principles outlined in this guide, researchers can leverage this powerful technique to uncover meaningful biological insights from complex methylation datasets, ultimately advancing our understanding of epigenetic regulation in development, disease, and environmental response.

DNA methylation profiling provides a critical window into epigenetic regulation, with methylation beta-values serving as a fundamental quantitative measure in genomic research. This technical guide explores the transformation of raw beta-values, typically represented in color-scaled heatmaps, into biologically significant insights. Framed within a broader thesis on profiling methylation levels and metagenes heatmaps research, this whitepaper details the computational frameworks, analytical pipelines, and interpretive methodologies that enable researchers to extract meaningful patterns from epigenetic data. For drug development professionals and research scientists, we present comprehensive workflows for beta-value interpretation, experimental protocols for methylation analysis, and advanced visualization techniques that facilitate the translation of epigenetic patterns into therapeutic discovery and clinical applications.

DNA methylation represents a fundamental epigenetic modification involving the addition of a methyl group to the cytosine ring within CpG dinucleotides, primarily occurring in the context of CpG islands [4]. This process is mediated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and plays a crucial role in gene regulation, embryonic development, and genomic imprinting. The methylation beta-value provides a standardized quantitative measure for this epigenetic mark, calculated as the ratio of the methylated probe intensity to the overall intensity plus a constant offset: β = M/(M + U + α) where M represents methylated intensity, U unmethylated intensity, and α is a constant offset (typically 100) to stabilize low-intensity values [29]. This calculation produces a value between 0 and 1, representing the proportion of methylated cells at a specific CpG site, where 0 indicates complete absence of methylation and 1 indicates full methylation.

The biological significance of DNA methylation patterns extends across numerous research and clinical domains. In cancer diagnostics, methylation classifiers have standardized diagnoses across over 100 central nervous system tumor subtypes, altering histopathologic diagnosis in approximately 12% of prospective cases [4]. In pharmacoepigenetics, DNA methylation status of genes like BDNF has shown consistent correlation with clinical improvement in major depressive disorder treatment across multiple independent studies [30]. Furthermore, methylation patterns facilitate tracing tumor origins in neuroendocrine neoplasms, with organ-specific epigenetic signatures enabling precise prediction of cancer origin [31]. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationship between beta-values and their biological interpretation:

Quantitative Frameworks for Beta-Value Interpretation

Beta-Value Scales and Biological Correlates

The interpretation of beta-values follows established biological principles, though context-dependent considerations are essential for accurate analysis. The relationship between beta-values and transcriptional activity varies significantly across genomic contexts, with promoter methylation typically exhibiting inverse correlation with gene expression, while gene body methylation may show positive correlation [30]. The following table systematizes the standard interpretation of beta-value ranges across different genomic contexts:

Table 1: Beta-Value Interpretation Across Genomic Contexts

| Beta-Value Range | Methylation Status | Typical Promoter Impact | Typical Gene Body Impact | Common Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00-0.20 | Hypomethylated | Gene activation | Uncertain significance | Open chromatin; Active transcription; Enhancer activity |

| 0.20-0.60 | Intermediate | Context-dependent | Context-dependent | Tissue-specific regulation; Developmental stage markers |

| 0.60-1.00 | Hypermethylated | Gene silencing | Possible transcription elongation | Genomic imprinting; X-chromosome inactivation; Cancer silencing |

The precise relationship between beta-values and biological meaning must be established through empirical validation. For example, in a systematic pharmacoepigenomic analysis of cancer cell lines, researchers identified 19 DNA methylation biomarkers across 17 drugs and five cancer types where methylation status served as a predictive biomarker for drug sensitivity [32]. Similarly, in neuroendocrine neoplasms, methylation profiles accurately traced tumor origins, demonstrating how beta-value patterns reflect tissue-of-origin signatures [31].

Alternative Metrics: M-Values for Statistical Analysis

While beta-values provide intuitive biological interpretation, the M-value (log2 ratio of methylated to unmethylated intensities) offers superior statistical properties for differential methylation analysis [29]. The M-value's approximately normal distribution makes it more amenable to parametric statistical tests commonly used in identifying differentially methylated positions (DMPs). The relationship between beta-values and M-values follows a sigmoidal pattern, with M-values providing greater separation between values at the extremes of the methylation spectrum. For comprehensive analysis, researchers often utilize both metrics: beta-values for biological interpretation and visualization, and M-values for statistical testing.

Experimental Protocols for Methylation Analysis

Methylation Array Workflow

The Illumina Infinium methylation array platform remains widely used for epigenome-wide association studies due to its cost-effectiveness and streamlined data analysis workflow [29]. The following protocol outlines the standard processing pipeline:

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

- Extract genomic DNA from target tissue (blood, tumor biopsies, or cell lines) using standard kits

- Treat DNA with bisulfite conversion using EZ DNA Methylation kits (Zymo Research) to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils

- Hybridize converted DNA to Illumina Infinium HumanMethylationEPIC v2.0 or 450k BeadChips

- Scan arrays using Illumina iScan or similar systems to generate raw intensity data (IDAT files)

Data Preprocessing and Normalization

- Import IDAT files into R/Bioconductor using the

minfipackage - Perform quality control checks using

minfiQCto identify sample outliers - Execute background correction and normalization using preprocessQuantile() or preprocessNoob()

- Filter probes with detection p-value > 0.01, cross-reactive probes, and SNP-associated probes

- Annotate probes to genomic contexts using IlluminaHumanMethylationEPICanno.ilm10b4.hg19

Differential Methylation Analysis

- Convert methylation values to M-values for statistical analysis

- Implement linear modeling using

limmapackage to identify DMPs - Apply multiple testing correction (Benjamini-Hochberg FDR < 0.05)

- Convert significant results back to beta-values for biological interpretation

- Perform differential methylation region (DMR) analysis using

DMRcate

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete analytical pipeline from raw data to biological interpretation:

Advanced Sequencing-Based Approaches

While arrays provide cost-effective methylation screening, sequencing-based methods offer enhanced genomic coverage and single-base resolution:

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS)

- Provides comprehensive, single-base resolution methylation mapping across the entire genome

- Requires higher sequencing depth (typically 30x coverage) and computational resources

- Ideal for discovering novel methylation patterns outside predefined CpG sites

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS)

- Enriches for CpG-dense regions through enzymatic digestion (MspI)

- Cost-effective alternative for targeting promoter regions and CpG islands

- Suitable for large cohort studies with limited budget

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) Sequencing

- Enables simultaneous detection of nucleotide modifications and genetic variation

- Provides long-read capabilities for haplotype-specific methylation analysis

- Growing application in population-scale epigenetic studies [33]

Visualization and Interpretation of Methylation Patterns

Heatmap Interpretation Strategies