From Prediction to Validation: A Comprehensive Guide to Confirming Protein-Protein Interactions in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to validate bioinformatically predicted protein-protein interactions (PPIs).

From Prediction to Validation: A Comprehensive Guide to Confirming Protein-Protein Interactions in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to validate bioinformatically predicted protein-protein interactions (PPIs). Covering foundational concepts, established experimental methods like co-immunoprecipitation and FRET, advanced computational tools including machine learning and the novel GRASP platform, and troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, it serves as an essential guide for translating in silico predictions into biologically verified findings. The content synthesizes traditional biochemical techniques with cutting-edge computational approaches, offering comparative analysis to help scientists design robust validation workflows, ultimately accelerating target identification and therapeutic development.

Understanding the PPI Landscape: From Bioinformatics Predictions to Biological Reality

The Critical Importance of PPI Validation in Drug Discovery and Disease Research

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental biological processes that regulate cellular functions, signaling pathways, and disease mechanisms. The comprehensive mapping of PPIs is vital to biomedical research, with the human interactome estimated to contain between 500,000 to 3 million interactions among nearly 200 million unique protein pairs [1]. However, most PPIs remain unknown, creating a significant knowledge gap in understanding disease pathogenesis and developing targeted therapies. Computational prediction of PPIs has emerged as an essential approach to bridge this gap, but these predictions require rigorous validation to be reliably applied in drug discovery pipelines. This article examines the critical importance of PPI validation through a comprehensive comparison of computational prediction methods, experimental protocols, and benchmark performance data.

Computational Prediction Methods for PPIs

Computational approaches for predicting PPIs leverage diverse biological information and machine learning algorithms to identify potential interactions. These methods generally fall into three main categories based on the input data they utilize.

1.1 Sequence-Based Predictors Sequence-based methods rely exclusively on amino acid sequence information to predict interactions. These approaches compute features from protein sequences using various representations including auto covariance (AC), pseudo amino acid composition (PSEAAC), and conjoint triads (CT) [1]. More recent deep learning frameworks like DL-PPI employ sophisticated architectures that combine Inception modules for protein node feature extraction with Feature-Relational Reasoning Networks (FRN) based on Graph Neural Networks to determine interactions between protein pairs [2]. These methods treat PPI prediction as a link prediction problem in graphs where proteins represent nodes and interactions form edges. The primary advantage of sequence-based methods is their independence from specific protein property information, requiring only sequence data [2].

1.2 Annotation-Based Predictors Annotation-based predictors utilize functional, subcellular localization, structural, and other biological annotation data to compute features for protein pairs [1]. These methods heavily rely on Gene Ontology (GO), structural domain databases, and gene expression databases to assemble features. Key computed metrics include co-occurrence in subcellular locations, co-expression correlation across experimental conditions or tissues, and semantic similarity of ontology annotations [1]. These features are then used as input for machine learning classification models. Annotation-based approaches must incorporate methodologies to handle missing values since not all proteins have complete biological annotations.

1.3 Homology-Based Validation Homology-driven validation operates on the evolutionary principle that most extant PPIs arise from gene duplication events, following the duplication-divergence hypothesis [3]. This approach validates experimentally determined PPIs by searching for homologous interactions in large, integrated PPI databases. Unlike earlier "interolog" concepts that focused solely on functionally conserved orthologs, modern homology-based validation searches for homologous PPIs independent of species boundaries or functional constraints, significantly increasing the amount of usable validation data [3]. Advanced implementations compute confidence scores that consider both quality and quantity of identified homologous PPIs, extending the search from reliable homologs to putative paralogs and orthologs with E-values up to 10 [3].

Table 1: Comparison of PPI Prediction Method Categories

| Method Category | Data Requirements | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Based | Amino acid sequences | Auto covariance, PSEAAC, Conjoint Triads, Deep Learning features | Wide applicability; doesn't require structural or functional data | Lower performance compared to annotation-based methods [1] |

| Annotation-Based | GO terms, expression data, subcellular localization | Co-expression correlation, semantic similarity, location co-occurrence | Higher prediction accuracy; incorporates functional context | Limited by annotation completeness and quality |

| Homology-Based | Known PPI databases across multiple species | Evolutionary conservation of interactions | Strong theoretical foundation; high efficacy on large datasets [3] | Limited by coverage of known PPIs in databases |

Benchmark Evaluation of Prediction Performance

Rigorous benchmark evaluations have revealed significant performance variations among PPI prediction methods, particularly when assessed under realistic data conditions rather than artificially balanced datasets.

2.1 The Real-World Performance Challenge A critical benchmark study re-implemented various published algorithms and evaluated them on datasets with realistic data compositions, finding that previously reported performance was often overstated [1] [4]. This exaggeration occurred because many original publications used evaluation datasets with equal proportions of positive and negative class data (50:50 ratio), while naturally occurring PPIs represent only 0.325–1.5% of all possible protein pairs in humans [1]. When tested on datasets with realistic data compositions, several methods were outperformed by control models built on 'illogical' and random number features [1]. This highlights the importance of proper benchmark composition when assessing PPI prediction algorithms for real-world applications.

2.2 Comparative Performance of Method Categories Benchmark evaluations have consistently demonstrated that sequence-only-based algorithms perform worse than those employing functional and expression features [1]. The over-characterization of some proteins in scientific literature, combined with the scale-free nature of PPI networks where a few "hub" proteins participate in numerous interactions, causes many prediction methods to simply learn to predict interactions involving these well-characterized proteins rather than genuinely recognizing interaction patterns [1]. Evaluation metrics also significantly impact perceived performance; while most published works use AUC/accuracy metrics, precision-recall (P-R) curves are more appropriate for rare category data like PPIs and provide more reliable information for real-world applications [1].

Table 2: Benchmark Performance of PPI Prediction Methods

| Method Type | Reported Accuracy in Original Publications | Performance on Realistic Datasets | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Based Predictors | Up to 95-98% accuracy [1] | Significant performance drop; outperformed by random features in some cases [1] | Overfitting to biased data; inability to generalize to all possible protein pairs |

| Annotation-Based Predictors | Varies by method | Better maintained performance compared to sequence-only methods [1] | Dependent on completeness and quality of annotations |

| Deep Learning Methods (e.g., DL-PPI) | 92.5% accuracy on balanced datasets [2] | Diminished effectiveness on larger, unfamiliar datasets [2] | Limited capability to capture features from higher-order neighbors in graphs |

Integrated Experimental-Computational Validation Pipeline

Recent advances have integrated computational prediction with experimental validation in comprehensive pipelines that accelerate PPI-targeted drug discovery.

3.1 AI-Guided Pipeline for PPI Drug Discovery An innovative AI-guided pipeline combines experimental and computational tools to identify and validate PPI targets for early-stage drug discovery [5]. This approach employs a machine learning algorithm that prioritizes interactions by analyzing quantitative data from binary PPI assays or AlphaFold-Multimer predictions [5]. In a practical application targeting SARS-CoV-2, researchers used the quantitative LuTHy assay combined with their machine learning algorithm to identify high-confidence interactions among SARS-CoV-2 proteins, for which they predicted three-dimensional structures using AlphaFold-Multimer [5]. They subsequently employed VirtualFlow for ultra-large virtual drug screening targeting the contact interface of the NSP10-NSP16 SARS-CoV-2 methyltransferase complex, identifying a compound that binds to NSP10 and inhibits its interaction with NSP16 while disrupting the methyltransferase activity of the complex and SARS-CoV-2 replication [5].

3.2 Docking and Affinity Benchmarks Structure-based validation of PPIs relies on standardized benchmarks for assessing computational docking and affinity prediction methods. The integrated protein-protein interaction benchmarks include docking benchmark version 5 and affinity benchmark version 2, containing 230 and 179 entries, respectively [6]. These benchmarks consist of non-redundant, high-quality structures of protein-protein complexes along with unbound structures of their components, providing essential resources for method development and validation [6]. Performance assessments using these benchmarks reveal that considering only the top ten docking predictions per benchmark case, prediction accuracy reaches 38% across all 55 new cases added in version 5, and up to 50% for the 32 rigid-body cases only [6]. For affinity prediction, scores correlate with experimental binding energies up to r=0.52 overall, and r=0.72 for rigid complexes [6].

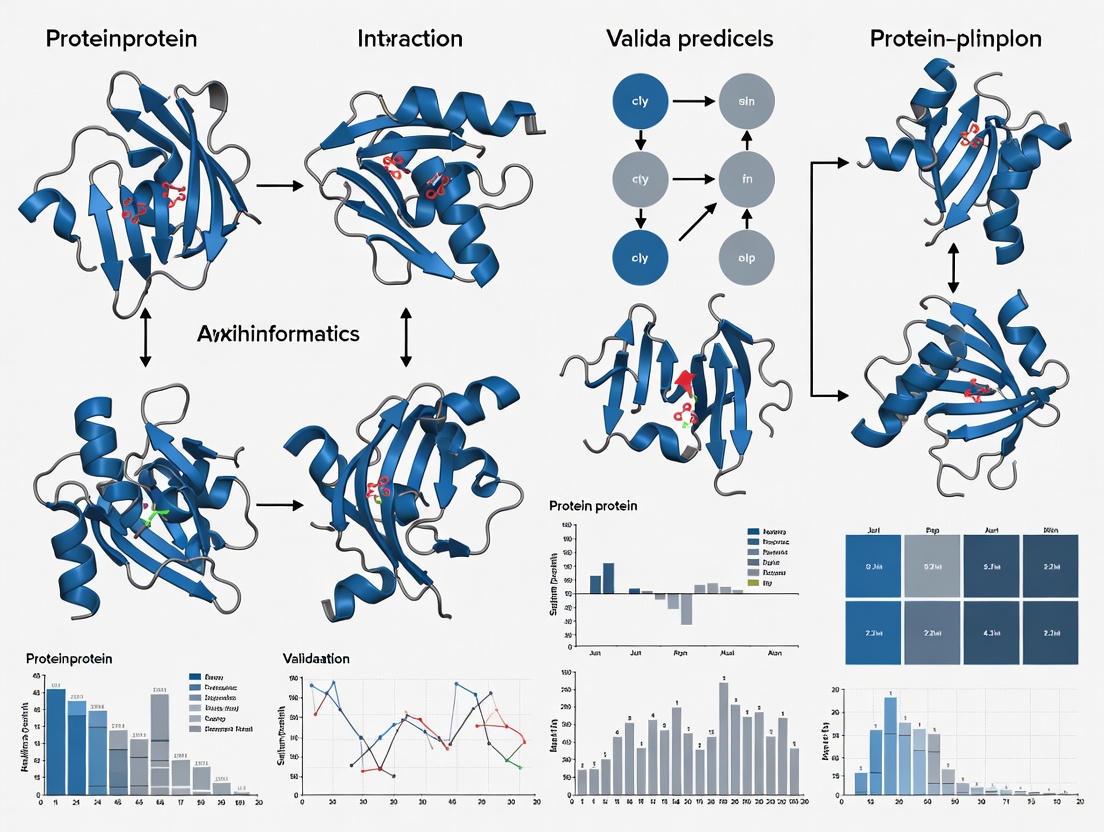

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of an integrated AI-guided validation pipeline for PPI drug discovery:

AI-Guided PPI Drug Discovery Pipeline

Experimental Protocols for PPI Validation

Experimental validation of computationally predicted PPIs employs a range of biochemical and biophysical techniques with varying throughput capacities and information content.

4.1 Low-Throughput Validation Methods Traditional low-throughput methods provide high-quality validation of individual PPIs but lack scalability for proteome-wide applications. Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) represents a gold standard technique that physically captures protein complexes using antibodies specific to one protein, followed by detection of co-precipitating partners [1] [4]. While resource-intensive and low-throughput, co-IP offers the advantage of studying PPIs under near-physiological conditions, though it may produce false negatives due to ineffective antibodies or the transient nature of some PPIs [1]. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) provides quantitative binding affinity data (KD values) and kinetic parameters (association/dissociation rates) without the need for labeling, making it invaluable for characterizing interaction strength and mechanism [6].

4.2 High-Throughput Screening Methods High-throughput methods enable systematic mapping of PPIs at the proteome scale but typically require computational validation to minimize false positives. Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screening detects binary interactions through reconstitution of transcription factors, with modern implementations achieving higher throughput but historically suffering from 25–45% false positive rates and difficulties detecting membrane protein interactions [1]. Tandem affinity purification mass-spectrometry (TAP-MS) identifies components of protein complexes rather than direct binary interactions, providing information about multi-protein assemblies [1]. More recently, sequencing-based approaches like PROPER-seq have emerged that can capture tens-to-hundreds of thousands of PPIs in single experiments [1]. Extensive filtering techniques, such as running multiple screens or comparing them to other data sources, can decrease false positive rates in high-throughput methods [1].

Table 3: Experimental Methods for PPI Validation

| Method | Throughput | Information Provided | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) | Low | Physical association under near-physiological conditions | High specificity; works with endogenous proteins | Resource-intensive; may miss transient interactions [1] |

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) | High | Binary protein interactions | Genome-scale capability; detects direct interactions | High false positive rate; difficult with membrane proteins [1] |

| TAP-MS | Medium-High | Protein complex composition | Identifies multi-protein complexes; more physiological context | Does not distinguish direct from indirect interactions |

| LuTHy | Medium | Quantitative interaction data | Quantitative data for machine learning [5] | Limited to specific experimental conditions |

Research Reagent Solutions for PPI Studies

The following table details essential research reagents and materials used in PPI validation experiments, along with their specific functions in the experimental workflow.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for PPI Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in PPI Validation | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies for Co-IP | Specific capture of bait protein and associated partners | Validation of suspected PPIs; confirmation of complex formation |

| Yeast Two-Hybrid Systems | Detection of binary interactions through transcription factor reconstitution | High-throughput screening of interaction libraries [1] |

| Affinity Purification Tags | Isolation of protein complexes under native conditions | TAP-MS experiments; purification of specific complexes |

| Plasmid Vectors | Expression of proteins of interest in relevant systems | Recombinant protein production; interaction screening assays |

| PPI Benchmark Datasets | Standardized data for method development and comparison | Docking Benchmark v5; Affinity Benchmark v2 [6] |

| Integrated PPI Databases | Source of known PPIs for homology-based validation | Compilation of 135,276 PPIs from 20 organisms [3] |

The validation of protein-protein interactions represents a critical step in translating computational predictions into biologically meaningful insights with applications in drug discovery and disease research. Benchmark evaluations have demonstrated that computational methods perform differently under realistic data conditions compared to artificially balanced datasets, with annotation-based approaches generally outperforming sequence-only methods [1]. The most promising validation strategies integrate multiple computational and experimental approaches, such as the AI-guided pipeline that successfully identified a SARS-CoV-2 inhibitor by combining machine learning prioritization, AlphaFold-Multimer predictions, and ultra-large virtual screening [5]. As PPI research continues to evolve, the development of more sophisticated benchmarks [6], larger integrated databases [3], and advanced deep learning architectures [2] will further enhance our ability to distinguish true biological interactions from computational artifacts, ultimately accelerating the discovery of PPI-targeted therapeutics for various diseases.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to most biological processes, including gene expression, cell growth, proliferation, nutrient uptake, motility, intercellular communication, and apoptosis [7]. The complexity of cellular functions arises not just from the number of proteins but from the intricate networks of their interactions [8]. Understanding PPIs is crucial for elucidating the mechanisms of biological processes and disease pathways, with protein interfaces representing attractive targets for therapeutic intervention [9] [10]. This guide focuses on two critical conceptual frameworks for understanding PPIs: the temporal stability of interactions (stable versus transient) and the energetic landscape of binding interfaces (hot spots).

Stable versus Transient Protein-Protein Interactions

Protein interactions are fundamentally characterized by their temporal stability and dissociation constants, which determine their duration and functional roles within the cell [7] [10].

Defining Characteristics and Biological Roles

Stable interactions form strong, long-lasting complexes that remain intact over time, often purified as multi-subunit complexes with identical or different subunits [7] [10]. Examples include hemoglobin and core RNA polymerase, where subunits form permanent complexes essential for their structural integrity and function [7]. These obligate interactions are necessary for proteins to perform their fundamental biological activities, with associating proteins often being unstable in isolation [10].

Transient interactions are temporary associations that typically require specific conditions such as phosphorylation, conformational changes, or localization to discrete cellular areas [7]. These weak, short-lived interactions occur for brief periods before dissociating and are crucial for diverse biological processes including signaling cascades, biochemical pathways, protein modification, transport, folding, and cell cycling [7] [10]. An example is the Rsc8 protein's transient interaction with NuA3, a histone acetyltransferase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [10].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Stable versus Transient Protein-Protein Interactions

| Characteristic | Stable Interactions | Transient Interactions |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Duration | Long-lasting, permanent [10] | Temporary, short-lived [7] [10] |

| Dissociation Constant | Low (strong binding) [7] | High (weak binding) [7] |

| Functional Role | Essential structural complexes; obligate interactions [10] | Signaling, regulation, feedback; non-obligate interactions [7] [10] |

| Interface Size | Typically larger interfaces [9] | Often smaller interfaces between short linear motifs and domains [10] |

| Example Techniques | Co-immunoprecipitation, pull-down assays without crosslinking [7] | Crosslinking, label transfer, far-western blot analysis [7] |

| Biological Examples | Hemoglobin, core RNA polymerase, Arc repressor dimer [7] [10] | Growth factor receptor signaling, G-protein subunits (Gα and Gβγ) [7] [10] |

Experimental Validation Methods

Validating the stability characteristics of PPIs requires specific methodological approaches tailored to interaction kinetics and strength.

For Stable Interactions: Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) is a widely used technique where an antibody specific to a "bait" protein precipitates it along with strongly associated "prey" binding partners from a cell lysate [7] [10]. The co-precipitated complexes are typically detected by SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis [7]. Pull-down assays function similarly but use affinity-tagged bait proteins (e.g., GST-, polyHis-, or streptavidin-tagged) captured by corresponding beads to purify binding partners from lysates [7] [10]. The Thermo Scientific Pierce Protein A/G Magnetic Beads represent specialized research reagents optimized for such immunoprecipitation and co-immunoprecipitation studies, enabling efficient isolation of complexes for downstream analysis [10].

For Transient Interactions: Crosslinking techniques stabilize temporary associations by chemically binding proteins in close proximity using linkers with functional groups that covalently connect interacting proteins [7] [10]. This process "freezes" the interaction during cell lysis and purification. Label transfer and far-western blot analysis provide alternative approaches to capture these fleeting associations independent of other methods [7].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for PPI Validation. This diagram outlines the primary methodological pathways for validating stable versus transient protein-protein interactions, culminating in detection by western blot or mass spectrometry.

Energetic Hot Spots at Protein Interfaces

The energy distribution across protein-protein interfaces is not uniform, with a small subset of residues contributing disproportionately to binding affinity [9].

Fundamental Principles of Hot Spots

Hot spots are defined as interfacial residues whose mutation to alanine causes a significant decrease in binding free energy (ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol) [11] [9]. These residues are structurally conserved and constitute only about 10% of interfacial residues, yet they account for the majority of the binding free energy in protein complexes [9]. The composition of hot spots is distinctive and non-random, with tryptophan (21%), arginine (13.3%), and tyrosine (12.3%) being the most prevalent amino acids due to their size, aromatic π-interactive nature, large hydrophobic surfaces, and protective effects from water [11] [9]. Hot spots often occur within complemented pockets enriched in conserved residues and are frequently surrounded by energetically less important residues that form an O-ring structure to occlude bulk solvent, according to the "double water exclusion" hypothesis [11].

Computational Prediction Methods

Computational approaches for hot spot prediction have evolved to overcome the limitations of experimental methods, utilizing various algorithms and feature sets.

Experimental Foundation: Alanine scanning mutagenesis serves as the gold standard for hot spot identification, where interface residues are systematically replaced with alanine and the change in binding free energy (ΔΔG) is measured [11] [9]. This method removes all atoms in the side chain past the β-carbon without introducing unwanted conformational flexibility [9]. Data from such experiments are cataloged in databases like the Alanine Scanning Energetics Database (ASEdb) and Binding Interface Database (BID) [11].

Machine Learning Approaches: PredHS2 represents an advanced computational method that employs Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) with 26 optimally selected features including sequence, structure, exposure, energy features, and neighborhood properties [11]. This method demonstrates how feature selection algorithms like minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) and sequential forward selection significantly improve prediction quality [11]. PPI-hotspotID is another machine-learning method that identifies hot spots using free protein structures with only four residue features: conservation, amino acid type, solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), and gas-phase energy (ΔGgas) [12]. When combined with AlphaFold-Multimer-predicted interface residues, this method achieves enhanced performance [12].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Hot Spot Prediction at Protein Interfaces

| Method | Approach | Features Used | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| PredHS2 [11] | Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | 26 optimal features including sequence, structure, exposure, energy, Euclidean and Voronoi neighborhoods [11] | Outperforms other machine learning algorithms; novel features like solvent exposure and disorder scores are particularly discriminative [11] |

| PPI-hotspotID [12] | Ensemble classifiers using free protein structures | Conservation, amino acid type, SASA, gas-phase energy [12] | F1-score of 0.71; outperforms FTMap and SPOTONE methods; valuable for drug design [12] |

| Alanine Scanning [9] | Molecular dynamics simulations or empirical scoring | Computed binding energy differences between wild-type and mutant | Foundation for many computational methods; accurate but computationally expensive [9] |

| Robetta [9] | Energy-based computational alanine scanning | Estimated energetic contributions to binding for interface residues | Webserver accessible; useful for large-scale predictions [9] |

| FTMap [9] [12] | Probe-based rigid body docking | Consensus sites binding multiple probe clusters | Identifies hot spots from free protein structure; lower recall (0.07) compared to machine learning methods [12] |

Diagram 2: Integrated Pipeline for Hot Spot Identification. This diagram illustrates the complementary experimental and computational pathways for identifying and validating hot spot residues at protein interfaces, culminating in applications for drug design and interface analysis.

Integrated Validation Framework for Bioinformatics Predictions

Validating bioinformatics predictions of PPIs requires an integrated approach that combines computational and experimental methods to address the high false-positive rates associated with each technique individually [13] [14].

Synergistic Computational-Experimental Strategy

Bioinformatics predictions of protein-protein interactions can be validated through a multi-step approach that combines sequence similarity, structural modeling, and experimental verification [13]. This begins with selecting potential interactors from experimental results not yet validated in vivo, then exploiting sequence and structural information from confirmed interacting proteins and complexes to suggest the most likely interactors through a calculated score [13]. For hot spot predictions, computational methods like PPI-hotspotID can identify critical residues from free protein structures, which are then validated experimentally through targeted mutagenesis followed by interaction assays like co-immunoprecipitation or yeast two-hybrid screening [12]. This integrated framework significantly reduces the experimental burden and costs associated with purely empirical approaches while enhancing reliability.

Research Reagent Solutions for PPI Validation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein-Protein Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Thermo Scientific Pierce Protein A/G Magnetic Beads [10] | Antibody immobilization for immunoprecipitation and co-IP | Efficient isolation of protein complexes from cell lysates for downstream analysis |

| Crosslinkers (e.g., homobifunctional, amine-reactive) [7] | Stabilization of transient protein interactions | Covalently linking interacting proteins to preserve transient complexes during lysis and purification |

| Affinity Tags (GST-, polyHis-, streptavidin-tagged proteins) [7] [14] | Bait protein immobilization for pull-down assays | Purification of binding partners from complex cell lysates using corresponding bead systems |

| Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) Tags [14] | Two-step purification of protein complexes under native conditions | Identification of multi-protein complexes with reduced background contamination |

| Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis Kits | Systematic mutation of interface residues to alanine | Experimental identification and validation of hot spot residues contributing to binding energy |

| Position-Specific Scoring Matrices (PSSM) [15] | Encoding evolutionary information from protein sequences | Feature extraction for machine learning-based prediction of PPIs and hot spots |

Understanding the distinction between stable and transient interactions and the concept of interface hot spots provides a sophisticated framework for analyzing protein-protein interactions beyond simple binary classification. Stable interactions form the structural backbone of cellular machinery, while transient interactions enable dynamic cellular responses to stimuli. Meanwhile, hot spots represent critical functional residues that dominate binding energy landscapes. The integration of computational predictions with targeted experimental validation creates a powerful paradigm for efficiently characterizing these complex biological phenomena. This approach accelerates the identification of therapeutic targets, particularly for disrupting pathological interactions in disease states, and continues to refine our understanding of cellular signaling and regulation networks. As computational methods improve in accuracy and experimental techniques enhance in sensitivity, the synergy between these approaches will become increasingly vital for advancing proteomics research and drug discovery.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to cellular processes, including signal transduction, DNA replication, and cell cycle progression [16]. The network of all PPIs, known as the interactome, is a central focus in molecular biology and drug discovery [17]. However, the high-throughput experimental methods used to map these interactions, such as the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system and affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS), are notoriously prone to false positives and false negatives, with error rates estimated from 15% to as high as 80% [14]. This reality makes computational and experimental validation a critical step in bioinformatics research. The process is fraught with specific biological challenges, primarily stemming from the flat molecular interfaces of many PPIs, their transient nature, and the difficulty in ensuring binding specificity. This guide objectively compares the performance of various validation methodologies against these hurdles, providing researchers with a framework for confirming bioinformatic predictions.

Core Technical Challenges in PPI Validation

Validating a predicted PPI requires overcoming several intrinsic biological complexities. These challenges directly impact the efficacy of both experimental and computational validation methods.

- Flat Interfaces: Unlike the deep pockets of enzyme active sites, many PPI interfaces are large, flat, and lack distinct features [17]. This makes it difficult for small molecules to bind and inhibit the interaction, a common validation strategy. It also complicates the use of structural data for confirmation.

- Transient Interactions: Many biologically critical PPIs are transient, involving rapid association and dissociation in response to cellular signals [14] [17]. Their temporary nature makes them difficult to capture with standard, stability-focused methods like AP-MS, which are better suited for stable complexes.

- Specificity and Affinity: Distinguishing true, biologically relevant interactions from non-specific binding is a major hurdle. Weak affinity interactions can be functionally important but are often dismissed as noise, while some high-throughput methods generate false positives through non-physiological conditions [18] [14].

Performance Comparison of PPI Validation Methods

The following table summarizes key validation methods, their core principles, and their performance against the central challenges.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of PPI Validation Methods

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Key Strength | Key Limitation | Effectiveness vs. Flat Interfaces | Effectiveness vs. Transient Interactions | Effectiveness vs. Specificity Issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homology-Based Validation [18] | Searches for homologous PPIs in integrated databases. | Computational / High | Leverages evolutionary principle; high efficacy when data is available. | Limited by coverage and completeness of existing PPI databases. | Low (indirect) | Medium | High (uses scoring of multiple homologs) |

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) [14] | Reconstitution of transcription factor via protein interaction. | Experimental / High | Works in cellular environment; can map vast networks. | High false positive rate; proteins must relocate to nucleus. | Low | Medium | Low |

| Affinity Purification MS (AP-MS) [14] | Purification of protein complexes and identification via mass spectrometry. | Experimental / High | Studies complexes under near-physiological conditions. | High false positives from contaminants; less effective for transient complexes. | Low | Low | Medium (requires careful controls) |

| Tandem Affinity Purification MS (TAP-MS) [14] | Two-step purification to reduce contaminants. | Experimental / Medium | Higher specificity than AP-MS; reduced false positives. | Can miss transient or weakly associated interactors. | Low | Low | High |

| Cross-Linking MS [14] | Chemically "freezing" interactions before analysis. | Experimental / Medium | Captures transient and weak interactions effectively. | Complexity of data analysis and identification. | Medium | High | Medium |

| Machine Learning (PCLPred) [16] | Uses protein sequence (PSSM) and RVM classifier to predict interaction. | Computational / High | High accuracy (e.g., 94.6%); uses only sequence data. | A predictive model, not a direct validation; depends on training data quality. | Low (indirect) | Low (indirect) | Medium (indirect) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

To ensure reproducible results, below are detailed protocols for two pivotal methods: one computational and one experimental.

Protocol: Homology-Based Computational Validation

This improved method uses a sensitive sequence-based search to find homologous PPIs, scoring them based on quality and quantity to validate an experimentally observed PPI [18].

- Data Compilation: Compile a large, integrated database of known physical binary PPIs from multiple source databases (e.g., DIP, MINT, BIND) [18] [16].

- Homology Search: For a query protein pair (Protein A, Protein B), use a combination of FASTA and PSI-BLAST to perform a sensitive sequence-based search against the compiled PPI database.

- Identify Homologous PPIs: Search for pairs of interacting proteins (Protein A', Protein B') where A' is homologous to A and B' is homologous to B. The search should include tentative paralogs and orthologs with E-values up to 10 to capture weak signals of homology [18].

- Scoring: Apply a novel scoring scheme that incorporates both the quality (E-value of match) and quantity of all observed homologous PPIs. Normalize and combine scores from different homology search strategies.

- Validation Decision: A high cumulative confidence score indicates the queried PPI is biologically relevant. ROC curve analysis shows this method has high efficacy in separating true from false positives [18].

Protocol: Tandem Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry (TAP-MS)

TAP-MS is a robust biochemical method for validating protein complexes and their interactions with higher specificity than single-step AP-MS [14].

- Tagging: Fuse the gene of the bait protein with a TAP-tag (e.g., Protein A - TEV protease cleavage site - Calmodulin Binding Peptide) and express it in the host system at physiological levels [14].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells using a mild, non-denaturing lysis buffer to preserve native PPIs. Include protease inhibitors to maintain protein integrity.

- First Affinity Step:

- Incubate the cell lysate with IgG Sepharose beads.

- The Protein A part of the TAP-tag binds to the IgG beads.

- Wash thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- TEV Protease Elution: Cleave the fusion protein from the beads by adding the TEV protease, which recognizes and cuts its specific site.

- Second Affinity Step:

- Incubate the eluate with Calmodulin-coated beads in the presence of calcium.

- The Calmodulin Binding Peptide (CBP) binds to the calmodulin beads.

- Wash again to remove any remaining contaminants.

- Final Elution: Elute the purified protein complex from the beads with a buffer containing EGTA, which chelates calcium and disrupts the calmodulin-CBP interaction.

- MS Analysis: Identify the components of the purified complex using Mass Spectrometry (MS or MS/MS). Compare the list of identified proteins against controls (e.g., purifications with a different tagged protein) to distinguish true interactors from background binders.

Visualization of Methodologies

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow for computational validation and the experimental setup for TAP-MS.

Homology-Based PPI Validation Logic

TAP-MS Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful PPI validation relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below details essential items for setting up these experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for PPI Validation

| Reagent / Tool | Function in PPI Validation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| TAP-Tag System [14] | Enables two-step purification of protein complexes with high specificity, reducing background. | TAP-MS validation of stable protein complexes. |

| PSI-BLAST Software [18] | Performs sensitive, iterative database searches to find distant protein homologs. | Homology-based computational validation of a queried PPI. |

| Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM) [16] | Represents evolutionary conservation in a protein sequence; used as feature input for machine learning models. | Training and using the PCLPred predictor for sequence-based PPI prediction. |

| Relevance Vector Machine (RVM) [16] | A machine learning classifier that provides probabilistic output, often outperforming SVMs on small, high-dimensional datasets. | Classifying protein pairs as interacting or non-interacting in computational screens. |

| Cross-linking Reagents [14] | Chemically covalently link interacting proteins, "freezing" transient interactions for analysis. | Capturing short-lived PPIs for identification by mass spectrometry. |

| IgG Sepharose Beads [14] | The affinity resin for the first purification step in the TAP-MS protocol, binding the Protein A tag. | Purification of TAP-tagged protein complexes from cell lysates. |

| TEV Protease [14] | A highly specific protease used to cleave and elute the protein complex after the first affinity step in TAP-MS. | Releasing a bound protein complex from IgG Sepharose beads under mild conditions. |

| 8-Methylimidazo[1,5-a]pyridine | 8-Methylimidazo[1,5-a]pyridine|Research Chemical | |

| 2-Methoxy-4-(2-nitrovinyl)phenol | 2-Methoxy-4-(2-nitrovinyl)phenol|CAS 6178-42-3 | High-purity 2-Methoxy-4-(2-nitrovinyl)phenol for RUO. A key synthon in organocatalysis for chiral benzopyrans. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Validating protein-protein interactions predicted by bioinformatics remains a multifaceted challenge. As the comparison data shows, no single method is universally superior against the hurdles of flat interfaces, transient interactions, and specificity. Computational methods like homology-based scoring and machine learning offer high-throughput screening but provide indirect evidence. In contrast, experimental techniques like TAP-MS and cross-linking MS deliver direct biochemical proof but are more resource-intensive and have their own blind spots. The most robust validation strategy is a convergent one, where bioinformatic predictions are confirmed by multiple, orthogonal experimental methods. This integrated approach, leveraging the strengths of each technique while mitigating their weaknesses, is essential for building an accurate and reliable interactome, which in turn forms a solid foundation for understanding disease mechanisms and developing novel therapeutics.

The Role of Bioinformatic Predictions as a Starting Point for Experimental Design

Bioinformatic predictions have revolutionized the starting point for experimental biology, transforming how researchers approach the complex landscape of protein-protein interactions (PPIs). These computational methods provide a critical first filter for identifying potential interactions among the vast combinatorial space of possible protein pairs, guiding efficient allocation of experimental resources [19]. The paradigm has shifted from purely discovery-based experimentation to a targeted validation approach, where in silico predictions form testable hypotheses that are subsequently confirmed or refuted through carefully designed experiments. This integrated workflow is particularly vital in drug development, where understanding PPIs is essential for target identification and validation [20]. The field is now characterized by a continuous cycle where computational predictions inform experimental design, and experimental results subsequently refine and improve predictive algorithms. This article examines this interplay by comparing major bioinformatic prediction methods, detailing experimental validation protocols, and providing a toolkit for researchers navigating this integrated landscape.

Comparative Analysis of Bioinformatic Prediction Methods

Bioinformatic approaches for predicting protein-protein interactions vary significantly in their underlying principles, data requirements, and performance characteristics. The table below provides a structured comparison of major computational methods, highlighting their relative strengths and limitations for experimental design.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction Methods

| Method Category | Underlying Principle | Typical Data Requirements | Reported Accuracy Range | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Based Methods [19] | Detects known interacting motifs/domains in amino acid sequences | Protein sequences, domain databases (e.g., Pfam, PROSITE) | 75-85% (varies by organism) | Initial screening, proteins with known domains |

| Genomic Context Methods [21] | Infers interaction from genomic patterns (gene fusion, conserved neighborhood) | Genomic sequences across multiple species | 70-80% | Prokaryotic systems, evolutionary studies |

| Structure-Based Methods [22] [21] | Predicts interaction based on 3D structural compatibility | Protein structures (experimental or predicted) | 80-90% (with high-quality structures) | Interface analysis, drug target identification |

| Machine Learning Methods [22] [23] | Classifies interacting pairs using trained models on diverse features | Known PPI networks for training, various protein features | 85-92% | Large-scale mapping, integrative analysis |

| Phylogenetic Profiling [21] | Identifies proteins with correlated evolutionary history | Multiple sequence alignments across genomes | 75-85% | Functional linkage, pathway reconstruction |

Performance Considerations for Experimental Design

When selecting a prediction method as starting point for experimentation, researchers must consider several performance factors beyond sheer accuracy. Machine learning methods, particularly those using random forest decision classifiers or support vector machines, have gained prominence for their ability to integrate multiple data types and achieve high prediction accuracy [21] [22]. However, these methods often require large training datasets and may exhibit bias toward well-characterized protein families.

Structure-based methods provide the advantage of suggesting molecular mechanisms of interaction through residue-level contact predictions, which can directly inform mutagenesis experiments [21]. The recent integration of AlphaFold and other deep learning models has significantly enhanced these approaches, enabling accurate structure prediction even without experimentally solved templates [22] [24].

For poorly characterized proteins or non-model organisms, sequence-based methods and genomic context approaches remain valuable starting points despite their more modest accuracy, as they require minimal prior experimental data [19].

Experimental Validation Frameworks

Once bioinformatic predictions identify candidate interactions, rigorous experimental validation is essential to confirm biological relevance. The table below compares key experimental techniques used to validate predicted PPIs, with their respective applications and limitations.

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Validating Predicted Protein-Protein Interactions

| Method | Key Measurable | Throughput | Key Advantage | Major Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) [21] [19] | Binary interaction via transcription activation | High | Tests direct physical interaction | High false-positive rate; proteins must localize to nucleus |

| Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS) [19] | Co-purification of protein complexes | Medium | Identifies complex constituents, not just binary pairs | Cannot distinguish direct from indirect interactions |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [19] | Binding affinity and kinetics (KD, kon, koff) | Low | Provides quantitative binding parameters | Requires purified proteins; low throughput |

| Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) [21] [19] | Protein proximity (<10nm) | Medium | Detects interactions in near-native cellular environments | Technically challenging; requires fluorophore tagging |

| Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) [19] | Protein co-purification from cell lysates | Medium | Works in near-physiological conditions | Cannot distinguish direct from indirect interactions |

Integrated Validation Workflow

A robust experimental design typically employs complementary techniques to validate bioinformatic predictions, moving from initial confirmation to quantitative characterization. The following workflow diagram illustrates a logical validation pathway from computational prediction to experimental confirmation:

Validation Workflow for Predicted PPIs

This workflow begins with initial screening using higher-throughput methods like yeast two-hybrid or co-immunoprecipitation to confirm the predicted interaction exists under experimental conditions. Positive results then progress to quantitative binding studies using surface plasmon resonance or FRET to obtain kinetic parameters and affinity measurements. Finally, functional characterization through mutational analysis and cellular assays establishes the biological relevance of the validated interaction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful experimental validation of bioinformatic predictions requires carefully selected research reagents. The table below details essential materials and their specific functions in PPI validation workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PPI Validation Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | GAL4-based Y2H vectors, Gateway-compatible clones | Enable protein expression in host systems | Bait and prey vectors must have compatible selection markers |

| Tagging Systems | GFP/RFP variants, HA-Flag tags, HIS/GBD tags | Enable detection and purification | Consider tag size and potential interference with interaction |

| Cell Lines | Yeast strains (Y2H), HEK293T, specialized knockout lines | Provide cellular context for interaction | Select cells expressing relevant signaling components |

| Antibodies | Anti-tag antibodies, domain-specific antibodies | Detect and purify proteins of interest | Validate antibody specificity for intended applications |

| Libraries | cDNA libraries, mutant libraries, domain libraries | Screen interaction partners or variants | Quality depends on library completeness and representation |

| Benzyl 5-hydroxypentanoate | Benzyl 5-hydroxypentanoate, CAS:134848-96-7, MF:C12H16O3, MW:208.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (2R)-2-Tert-butyloxirane-2-carboxamide | (2R)-2-Tert-butyloxirane-2-carboxamide|High Purity | Get (2R)-2-Tert-butyloxirane-2-carboxamide (C8H15NO2) for research. A chiral epoxide building block for asymmetric synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Specialized Solutions for Binding Characterization

For quantitative assessment of binding affinity and kinetics, specialized reagents and platforms are required. Surface plasmon resonance systems (e.g., Biacore) require sensor chips with immobilized capture ligands (e.g., anti-GST antibodies) and high-quality purified proteins at appropriate concentrations for kinetic analysis [19]. For FRET-based approaches, fluorophore-tagged protein variants must be engineered with consideration for quantum yield and spectral compatibility. The emerging field of AI-assisted structural prediction has created demand for specialized computational resources, with tools like AlphaFold and RosettaFold enabling more accurate interface predictions that guide mutagenesis experiments [22] [24].

Data Integration and Emerging Trends

The future of bioinformatic predictions as a starting point for experimental design lies in sophisticated data integration and emerging computational technologies. Multimodal AI approaches that combine genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and structural data are creating more comprehensive predictive models [24]. The following diagram illustrates how diverse data types feed into an integrated prediction-validation pipeline:

Data Integration in PPI Prediction

Key emerging technologies include quantum computing for simulating molecular interactions [24], single-cell sequencing for understanding cellular context in immune profiling [22] [23], and explainable AI to make computational predictions more interpretable to researchers [24]. These advances are particularly relevant for drug development professionals, who require not just prediction of interactions but also assessment of their druggability and potential as therapeutic targets [20].

Bioinformatic predictions serve as an indispensable starting point for experimental design, dramatically increasing the efficiency of PPI validation. The most successful research strategies employ a tiered approach that combines multiple prediction methods to generate high-confidence hypotheses, then validates these interactions through complementary experimental techniques. As computational methods continue to advance—with improvements in AI integration, structural prediction, and multi-omics data analysis—their role as the initial filter in experimental workflows will only expand. However, the critical importance of experimental validation remains unchanged; computational predictions guide researchers to the most promising hypotheses, but ultimate biological confirmation still rests on carefully executed experiments. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this integrated approach is now essential for navigating the complex landscape of protein-protein interactions and accelerating the translation of computational insights into biological understanding and therapeutic advances.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks are foundational to systems biology, providing a structured framework for understanding the intricate web of molecular interactions that govern cellular functions. These networks map physical and functional relationships between proteins, creating a comprehensive landscape of cellular signaling pathways, regulatory mechanisms, and functional modules [25]. The systematic study of PPIs has transformed our understanding of cellular signal transduction—a complex process involving precisely coordinated protein interactions that transmit information from extracellular stimuli to intracellular effectors, ultimately regulating critical processes including gene expression, metabolic pathways, and cell fate decisions [25].

The directed flow of information through PPI networks enables cells to process signals from membrane receptors to transcription factors, integrating multiple signaling inputs to generate appropriate physiological responses [25]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mapping these networks provides crucial insights into disease mechanisms and reveals potential therapeutic targets. As computational and experimental methods for PPI investigation continue to advance, they offer increasingly powerful approaches for validating bioinformatics predictions and translating network topology into biological understanding [26].

Experimental Methodologies for PPI Investigation

Established Experimental Techniques

Experimental validation of PPIs employs diverse methodologies, each with distinct strengths and limitations. The following table summarizes key techniques used in the field:

Table 1: Experimental Methods for PPI Investigation

| Method | Principle | Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) [25] [27] | Reconstitution of transcription factor via bait-prey interaction | Binary interaction screening; interaction domain mapping | High-throughput capability; comprehensive coverage | High false-positive rate; limited to nuclear interactions |

| Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) [27] | Sequential purification of protein complexes under native conditions | Identification of multi-protein complexes; complex stoichiometry | Preservation of native interactions; identification of stable complexes | May miss transient interactions; technically challenging |

| Protein Chip/Microarray [27] | High-throughput binding assays using immobilized proteins | Interaction profiling; antibody-antigen screening | Parallel analysis; minimal sample consumption | Requires purified proteins; may miss post-translational modifications |

| Mass Spectrometry [27] | Identification of co-purified proteins via mass analysis | Complex composition; post-translational modification detection | High sensitivity; unambiguous identification | Equipment intensive; complex data analysis |

Experimental Protocol: Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening

The yeast two-hybrid system represents a cornerstone methodology for large-scale PPI mapping. The following detailed protocol is adapted from the approach used to generate a directed network of 1,126 proteins through 2,626 interactions [25]:

- Strain Construction: Genetically engineer yeast strains to express DNA-Binding Domain (BD) fusions ("bait") and Activation Domain (AD) fusions ("prey")

- Automated Interaction Mating: Systematically mate bait and prey strains in high-density arrays using robotic systems

- Selection Growth: Plate diploid yeast on selective media lacking specific nutrients (typically leucine, tryptophan, and histidine) to identify successful interactions

- Reporter Activation: Detect successful PPI through activation of multiple reporter genes (HIS3, ADE2, LacZ) to minimize false positives

- Interaction Verification: Confirm positive interactions through repeat testing and domain-specific analysis

- Network Construction: Integrate verified interactions into a comprehensive PPI network using computational tools

This automated approach enabled the investigation of over 450 signaling-related proteins, creating a foundational dataset for understanding cellular signal transduction pathways [25].

Computational Prediction Methods for PPIs

Sequence-Based Prediction Frameworks

Computational methods have emerged as essential tools for complementing experimental PPI data, with sequence-based approaches offering particular utility when structural information is unavailable. The PCLPred methodology exemplifies this approach, achieving 94.56% accuracy on Saccharomyces cerevisiae datasets through a sophisticated integration of evolutionary information and machine learning [27]:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Computational PPI Prediction Methods

| Method | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | MCC | Feature Extraction | Classifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCLPred [27] | 94.56% | 94.79% | 94.36% | 89.6% | PSSM + Low-Rank Approximation | Relevance Vector Machine |

| SVM-Based [27] | 89.40% | 88.50% | 90.30% | 81.1% | PSSM + Low-Rank Approximation | Support Vector Machine |

| Deep Learning Framework [26] | 93.00% (AUROC) | - | - | - | Network Centrality + Node2Vec | XGBoost/Neural Network |

The PCLPred workflow integrates several innovative components: (1) evolutionary features extracted from Position-Specific Scoring Matrices (PSSM), (2) dimensionality reduction via Low-Rank Approximation (LRA), (3) noise reduction using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and (4) classification with Relevance Vector Machine (RVM) models [27]. This approach effectively handles the challenge of varying protein sequence lengths while capturing essential evolutionary information that correlates with interaction propensity.

Network-Based Prediction and Essential Gene Identification

Recent advances integrate PPI network topology with explainable artificial intelligence to prioritize therapeutic targets. One such framework combines six network centrality metrics with Node2Vec embeddings to achieve state-of-the-art performance (AUROC: 0.930) in predicting gene essentiality [26]. The methodology employs:

- Network Construction: High-confidence PPI networks from STRING database (confidence threshold ≥700)

- Centrality Analysis: Computation of six complementary centrality measures (degree, strength, betweenness, closeness, eigenvector centrality, clustering coefficient)

- Embedding Generation: Node2Vec algorithm to create 128-dimensional vector representations capturing latent network topology

- Model Training: XGBoost and neural network classifiers using DepMap CRISPR essentiality scores as ground truth

- Interpretability Analysis: GradientSHAP implementation to quantify feature contributions to predictions

This approach successfully identified known essential genes including ribosomal proteins (RPS27A, RPS17, RPS6) and oncogenes (MYC), with degree centrality showing the strongest correlation (Ï = -0.357) with gene essentiality [26].

Integrated Workflows for PPI Validation

A Framework for Experimental and Computational Integration

The most robust PPI investigations combine computational predictions with experimental validation, as exemplified by network pharmacology studies investigating traditional herbal medicines [28]. These integrated workflows employ:

- Component Identification: HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS analysis to identify bioactive metabolites (90 identified in CRP study) [28]

- Network Pharmacology: Target prediction using ETCM and SwissTargetPrediction databases, followed by PPI network construction using Cytoscape [28]

- Pathway Enrichment: KEGG analysis to identify predominant signaling pathways (MAPK pathways in CRP study) [28]

- Experimental Validation: In vivo therapeutic efficacy assessment and mechanism confirmation through protein expression analysis (e.g., TLR4, MyD88, p-NF-κB, MAPKs) [28]

This comprehensive approach enabled researchers to demonstrate that Citri Reticulatae Pericarpium alleviates functional dyspepsia by reducing activation of inflammation-related TLR4/MyD88 and MAPK signaling pathways while modulating gut microbial structure [28].

Directed PPI Networks for Signaling Pathway Investigation

Directed PPI networks represent a significant advancement over traditional binary interaction maps by incorporating directionality to resemble signal transduction flow between proteins [25]. These networks are constructed using a naïve Bayesian classifier that exploits information on shortest PPI paths from membrane receptors to transcription factors, enabling prediction of input-output relationships between interacting proteins [25].

Integration of directed PPI networks with time-resolved protein phosphorylation data reveals dynamic network structures that convey information from activated signaling cascades (e.g., EGF/ERK) to directly associated proteins and more distant network components [25]. This approach has successfully predicted 18 previously unknown modulators of EGF/ERK signaling, subsequently validated in mammalian cell-based assays [25].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Databases for PPI Investigation

| Category | Specific Resource | Key Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPI Databases | STRING Database [26] | High-confidence PPI network construction | Provides integrated protein interaction evidence from multiple sources |

| MINT, DIP, BIND [27] | Curated PPI data repository | Stores experimentally verified protein interactions | |

| Computational Tools | Cytoscape [28] | PPI network visualization and analysis | Enables construction of "metabolite-target" networks |

| Node2Vec [26] | Network embedding generation | Captures latent topological features from PPI networks | |

| PCLPred Web Server [27] | Sequence-based PPI prediction | Implements RVM classifier with PSSM features | |

| Experimental Resources | CRISPR-Cas9 Libraries (DepMap) [26] | Gene essentiality screening | Provides gold standard for essential gene identification |

| ELISA Kits (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β) [28] | Cytokine quantification | Measures inflammatory response in validation studies | |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies [28] | Signaling activation detection | Western blot analysis of pathway components (TLR4, MyD88, NF-κB) | |

| Benchmark Datasets | IEEE DataPort PPI [29] | Algorithm benchmarking | Standardized datasets for complex detection methods |

| CYC2008, MIPS Complexes [29] | Reference complex sets | Gold standards for protein complex detection algorithms |

The integration of computational prediction and experimental validation represents the most robust approach for elucidating PPIs and their roles in cellular signaling. Computational methods like PCLPred achieve impressive accuracy (94.56%) in predicting interactions [27], while experimental approaches like automated yeast two-hybrid screening provide essential ground-truth validation [25]. The emerging paradigm of explainable AI frameworks combines predictive power with mechanistic transparency, achieving state-of-the-art performance (AUROC: 0.930) while revealing the biological significance of network features like degree centrality in gene essentiality [26].

For drug development professionals, these integrated approaches offer powerful tools for therapeutic target prioritization. Network-based analyses successfully identify both known essential genes (ribosomal proteins RPS27A, RPS17, RPS6) and oncogenes (MYC), providing a rational foundation for target selection [26]. Similarly, network pharmacology approaches elucidate mechanisms of traditional medicines, demonstrating how compounds like CRP alleviate functional dyspepsia by modulating inflammation-related TLR4/MyD88 and MAPK signaling pathways [28]. As these methods continue to evolve, they promise to further accelerate the translation of PPI network insights into therapeutic discoveries.

A Practical Toolkit: Biochemical, Biophysical, and Computational Validation Methods

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) form the backbone of nearly all cellular processes, from metabolic cycles and DNA replication to signal transduction and immune response [30] [31]. While bioinformatics and computational methods have become powerful tools for predicting these interactions on a large scale, their findings require experimental validation to confirm physiological relevance [30]. This guide provides an objective comparison of two foundational biochemical techniques—co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and pull-down assays—used to confirm PPIs predicted by in silico research. By understanding the distinct principles, applications, and limitations of each method, researchers and drug development professionals can effectively design experiments to bridge the gap between computational prediction and biological confirmation.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Co-immunoprecipitation is an extension of classic immunoprecipitation, designed to isolate a native target protein along with its binding partners from a complex mixture, such as a cell lysate [32]. The principle relies on the specific binding of an antibody to a target protein (the antigen). When cells are lysed under non-denaturing conditions, physiologically relevant protein-protein interactions are preserved [33] [34]. The antibody, often pre-bound to protein A/G agarose or magnetic beads, captures the target antigen from the lysate. Any proteins complexed with this target are co-precipitated alongside it. These interacting "prey" proteins can then be detected and identified through techniques like Western blotting or mass spectrometry [33] [32].

Pull-Down Assays

Pull-down assays are a form of affinity purification that operate on a similar principle but use a different capture mechanism. Instead of an antibody, a purified, tagged "bait" protein is used to capture interacting "prey" proteins [33] [35]. The bait protein is immobilized on a solid support via an affinity ligand specific to its tag. Common tag/ligand pairs include glutathione-sepharose for GST-tagged proteins, nickel-/cobalt-coated resins for polyhistidine (His)-tagged proteins, and streptavidin-coated beads for biotinylated proteins [33] [36] [34]. This "secondary affinity support" is then incubated with a protein sample, and if the bait protein is functional in its immobilized state, interacting partners will bind and can be purified for analysis [33].

Direct Comparison: Co-IP vs. Pull-Down Assays

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these two techniques to aid in method selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Co-IP and Pull-Down Assays

| Feature | Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) | Pull-Down Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Antibody-antigen interaction [33] [32] | Affinity tag-ligand interaction [33] [35] |

| Bait Molecule | Endogenous or overexpressed protein of interest (antigen) [37] | Recombinant tagged protein (e.g., GST, His, Biotin) [33] [34] |

| Capture Agent | Antibody bound to Protein A/G beads [35] [32] | Affinity resin (e.g., Glutathione, Nickel, Streptavidin beads) [33] [36] |

| Physiological Context | High; uses native cell lysates, preserving many natural interactions [33] [34] | Low; typically uses purified components or in vitro systems, which may not reflect cellular conditions [33] [34] |

| Key Advantage | Identifies interactions under near-physiological conditions [33] | Does not require a specific antibody; useful for screening novel interactions in vitro [33] [36] |

| Primary Limitation | Requires a high-quality, specific antibody [33] [36]; may miss weak/transient interactions [33] [32] | Interactions may be non-physiological, as proteins are removed from their native environment [33] [34] |

| Typical Application | Validating putative PPIs in a cellular context [32] | Mapping direct binding partners or confirming a suspected direct interaction in vitro [33] |

| 1-Acetyl-4-(4-tolyl)thiosemicarbazide | 1-Acetyl-4-(4-tolyl)thiosemicarbazide, CAS:152473-68-2, MF:C10H13N3OS, MW:223.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-[(2-Thienylmethyl)amino]-1-butanol | 2-[(2-Thienylmethyl)amino]-1-butanol, CAS:156543-22-5, MF:C9H15NOS, MW:185.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the fundamental procedural steps for each method.

Diagram 1: Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) Workflow. The process begins with cell lysis under non-denaturing conditions to preserve protein complexes, followed by incubation with antibody-bound beads, washing, elution, and final analysis.

Diagram 2: Pull-Down Assay Workflow. The process involves immobilizing a recombinant tagged "bait" protein onto an affinity resin, incubating with a protein sample, washing, eluting interacting partners, and identifying the "prey."

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) Protocol

Key Reagents:

- Lysis Buffer: A non-ionic, non-denaturing buffer (e.g., containing NP-40 or Triton X-100) with low ionic strength (<120 mM NaCl) to maintain protein interactions [32]. Protease and phosphatase inhibitors are essential.

- Beads: Protein A, G, or A/G agarose or magnetic beads, chosen based on the antibody's species and isotype [35].

- Antibody: A high-quality, specific antibody against the target bait protein. The antibody can be bound directly to the beads (direct IP) or added to the lysate first (indirect IP) [35] [32].

- Wash Buffer: Typically the same as the lysis buffer to minimize disruption of weak interactions. The number and stringency of washes can be adjusted to reduce background [32].

- Elution Buffer: A low-pH buffer (e.g., glycine-HCl), Laemmli sample buffer, or a competitive peptide elution method to release the immune complex from the beads [35].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells or tissues gently using the chosen non-denaturing lysis buffer. Avoid harsh methods like sonication or vortexing, which can disrupt weak protein complexes [32]. Clear the lysate by centrifugation.

- Pre-clearing (Optional): Incubate the lysate with bare beads (without antibody) to remove proteins that bind non-specifically to the beads or resin.

- Antibody-Bead Preparation: Incubate the specific antibody with the Protein A/G beads for 30-60 minutes at 4°C to allow binding. Alternatively, for the indirect method, add the antibody directly to the cleared lysate.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the antibody-bound beads with the cell lysate for 1 hour to overnight at 4°C with constant gentle rotation. Overnight incubation can increase the yield of low-abundance targets [35].

- Washing: Pellet the beads (via centrifugation or magnetic separation) and carefully aspirate the supernatant. Wash the beads 3-5 times with 500 μL to 1 mL of ice-cold wash buffer. Handle the beads gently to prevent loss of the complex [32].

- Elution: Elute the bound proteins by adding an appropriate elution buffer and heating, or by competitive elution. If using a crosslinking kit, the antibody remains on the beads, and only the antigen and its partners are eluted, preventing antibody interference in downstream analysis [35] [32].

- Analysis: Analyze the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with antibodies against suspected prey proteins, or by mass spectrometry for unbiased identification of novel interactors [33] [32].

Pull-Down Assay Protocol

Key Reagents:

- Bait Protein: A purified recombinant protein fused to an affinity tag (e.g., GST, 6xHis, Biotin) [33] [34].

- Affinity Resin: Beads functionalized with the corresponding ligand (Glutathione for GST, Ni-NTA for His, Streptavidin for Biotin) [33] [36].

- Binding/Wash Buffer: Compatible with the tag system and the protein interaction. For example, PBS is commonly used for GST pull-downs, while buffers containing a low concentration of imidazole are used for His-tag pull-downs to reduce non-specific binding.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Immobilize the Bait: Incubate the purified, tagged bait protein with the appropriate affinity resin for 30-60 minutes at 4°C. This allows the bait to be captured onto the solid support.

- Blocking (Optional): Incubate the bait-bound resin with a blocking agent like BSA to minimize non-specific binding sites on the beads.

- Pull-Down Incubation: Incubate the immobilized bait protein with the "prey" sample. This can be a cell lysate, in vitro transcription/translation mixture, or another purified protein [33] [34]. Incubate for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle mixing.

- Washing: Pellet the beads and wash thoroughly (3-5 times) with a suitable wash buffer to remove unbound proteins. The stringency (e.g., salt concentration) can be adjusted to eliminate weak, non-specific binders.

- Elution: Elute the bound protein complexes. The method is tag-dependent:

- GST: Elute with reduced glutathione.

- His-tag: Elute with high-concentration imidazole or low pH.

- Biotin: Elute by competition with free biotin or under denaturing conditions.

- Analysis: Analyze the eluate by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting or mass spectrometry, similar to Co-IP analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions

The choice of reagents is critical for the success of both Co-IP and pull-down experiments. The table below lists essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PPI Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Beads | Protein A/G Agarose/Magnetic Beads [35], Glutathione Sepharose [33], Ni-NTA Agarose [33], Streptavidin Magnetic Beads [33] | Solid support for immobilizing the capture agent (antibody or bait protein). Magnetic beads offer ease of use and lower nonspecific binding [35]. |

| Tag-Specific Antibodies | Anti-HA Agarose [32], Anti-c-Myc Agarose [32], Anti-GST, Anti-His | Used for Co-IP of exogenously expressed tagged proteins or for detecting pulled-down prey proteins in Western blotting. |

| Lysis & Wash Buffers | RIPA Buffer, NP-40 Buffer [35] | To solubilize proteins and maintain complexes (lysis) and to remove non-specifically bound proteins without disrupting true interactions (wash) [32]. |

| Fusion Tag Systems | GST-tag [33] [34], 6xHis-tag [33] [36], Biotin tag [33] | Genetically encoded tags fused to the bait protein for purification and immobilization in pull-down assays. |

| Elution Reagents | Low-pH Buffer (e.g., Glycine-HCl) [35], Laemmli Sample Buffer, Reduced Glutathione, Imidazole | To dissociate and release the captured protein complexes from the beads for downstream analysis. |

Integration with Bioinformatics and Data Validation

Bioinformatics tools predict PPIs using genomic context, structural information, and machine learning algorithms [30] [31]. However, these predictions can contain false positives and negatives, necessitating experimental validation. Co-IP serves as a critical technique for confirming that bioinformatically predicted interactions occur under physiological conditions within the cell [33]. Pull-down assays are particularly useful for the subsequent step of determining whether a validated interaction is direct or mediated by a larger complex, as they allow for the use of purified components [33].

To ensure the reliability of interaction data, several verification strategies should be employed:

- Antibody Specificity: Confirm that the antibody used in Co-IP specifically recognizes the target protein and does not cross-react [32].

- Appropriate Controls: Include negative controls, such as samples with a non-specific antibody (for Co-IP) or beads with an unrelated tagged protein (for pull-down). A critical control is using cells that do not express the bait protein to rule out non-specific binding [32].

- Reciprocal Co-IP: Perform a second Co-IP using an antibody against the suspected prey protein to see if it pulls down the original bait.

- Cross-validation: Use an independent method, such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or fluorescence-based interaction assays, to confirm the interaction [37].

Co-immunoprecipitation and pull-down assays are complementary pillars in the experimental validation of protein-protein interactions. Co-IP excels at confirming interactions in their native cellular context, making it ideal for testing hypotheses generated by bioinformatics pipelines. In contrast, pull-down assays offer a reductionist approach to probe the biochemistry of direct binding and screen for novel interactors in a controlled environment. The choice between them hinges on the research question: use Co-IP to ask "Does this interaction happen in the cell?" and pull-down assays to ask "Can these two proteins bind directly?" By leveraging the strengths of both techniques and adhering to rigorous experimental design and validation protocols, researchers can confidently translate computational predictions into biologically meaningful and experimentally verified protein interaction networks, thereby advancing our understanding of cellular mechanisms and drug discovery.

The systematic elucidation of protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks is essential for understanding cellular behavior and molecular functions [38] [39]. As biological processes are increasingly understood through the lens of network biology, where proteins represent nodes and their physical interactions represent edges, the accurate determination of these connections becomes paramount [38] [40]. Within this framework, in vivo interaction assays provide critical validation for interactions initially predicted by bioinformatics, allowing researchers to confirm these relationships in a living cellular context. Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) and Protein Fragment Complementation Assay (PCA) represent two powerful, yet distinct, approaches for this confirmation, each with unique methodological foundations and application landscapes.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between Y2H and PCA is not merely technical but strategic, influencing the scope, biological relevance, and ultimate interpretation of interaction data. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these technologies, focusing on their implementation in validating bioinformatic predictions, their performance characteristics, and their appropriate integration into the drug discovery pipeline.

Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) System