From Transcriptome to Target: A Modern Guide to Selecting qPCR Reference Genes from RNA-Seq Data

Accurate gene expression analysis via qPCR is foundational to biomedical research and drug development, yet it critically depends on the use of stable reference genes for data normalization.

From Transcriptome to Target: A Modern Guide to Selecting qPCR Reference Genes from RNA-Seq Data

Abstract

Accurate gene expression analysis via qPCR is foundational to biomedical research and drug development, yet it critically depends on the use of stable reference genes for data normalization. Traditional housekeeping genes often exhibit significant expression variability, leading to unreliable results. This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step framework for leveraging RNA-seq data to systematically identify, optimize, and validate superior reference genes. We cover foundational principles, practical methodologies using modern software tools, troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and rigorous validation techniques aligned with MIQE guidelines. By translating high-throughput transcriptomic data into robust, experimentally-verified qPCR controls, this guide empowers researchers to achieve unparalleled accuracy and reproducibility in their gene expression studies.

Why Traditional Housekeeping Genes Fail and How RNA-Seq Provides a Solution

The Critical Role of Stable Reference Genes in Accurate qPCR Normalization

Reverse Transcriptase quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) is the current gold-standard technique for gene expression analysis due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and speed [1]. However, the accuracy of RT-qPCR is highly dependent on the normalization of target gene expression using appropriate reference genes (RGs), which are intended to exhibit stable expression levels across various experimental conditions [1]. Normalization is a critical process used to minimize technical variability introduced during sample processing, RNA extraction, and cDNA synthesis, ensuring that the analysis focuses exclusively on biological variation [2]. The use of unstable reference genes can easily lead to misinterpretation of target gene expression levels, ultimately resulting in incorrect biological conclusions [1] [2].

Despite the existence of MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines, which recommend thorough validation of reference gene performance, mistakes in qPCR experimental setup remain surprisingly common [1] [3]. These often include using an inappropriate number of reference genes or failing to accurately test reference gene stability under specific experimental conditions [1]. A particularly risky practice is the selection of reference genes based solely on their previous use in other experimental conditions, tissues, or even different species, without empirical validation for the current experimental context [1].

The Critical Importance of Reference Gene Stability

Consequences of Improper Reference Gene Selection

The assumption that so-called "housekeeping" genes maintain stable expression across all biological contexts is fundamentally flawed. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the expression of classic housekeeping genes can vary significantly depending on the experimental conditions, tissue types, and pathological states [2] [4]. When improper reference genes are used for normalization, the resulting data can be skewed, creating a significant bias that leads to incorrect biological interpretation [2].

Comparative studies across multiple species present additional challenges. Research on four closely related grasshopper species revealed clear differences in reference gene stability rankings between tissues and species [1]. Importantly, the choice of reference genes directly influenced the experimental results, demonstrating that the assumption of reference gene stability across closely related species is not necessarily valid [1]. This finding has profound implications for evolutionary studies employing comparative gene expression analysis.

Stability Validation in Different Biological Systems

The context-dependent nature of reference gene stability has been observed across diverse biological systems:

- In canine gastrointestinal tissues with different pathologies, the most stable reference genes identified were RPS5, RPL8, and HMBS, while the global mean of the expression of all tested genes emerged as the best-performing normalization method when profiling large gene sets [2].

- In tomato-Ralstonia pathosystems, comprehensive stability analysis identified UBI3, TIP41, and ACT as the most stable reference genes across multiple experimental conditions involving compatible and incompatible interactions [4].

- A novel combinatorial approach demonstrated that a stable combination of non-stable genes can outperform standard reference genes for RT-qPCR data normalization. This method utilizes RNA-Seq databases to identify gene combinations whose individual expressions balance each other across experimental conditions [5].

Experimental Protocols for Reference Gene Validation

Workflow for Identification and Validation of Reference Genes

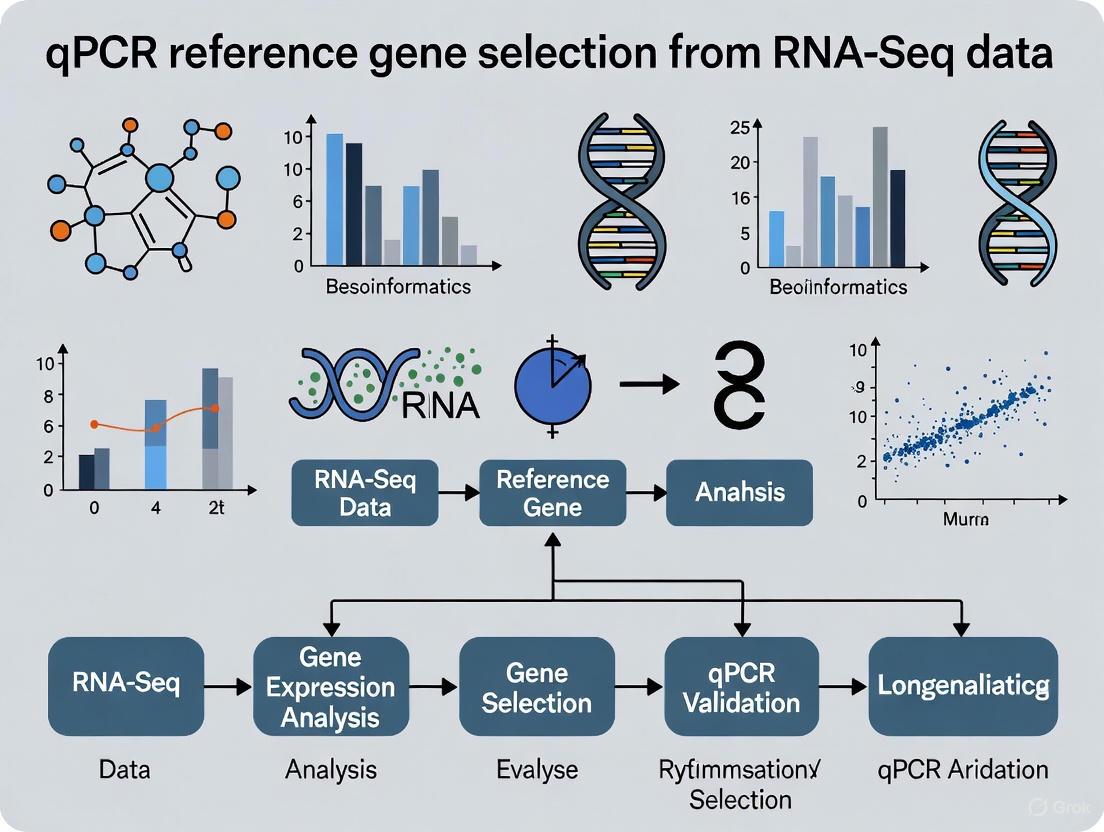

The diagram below illustrates the comprehensive workflow for identifying and validating stable reference genes, integrating both traditional and novel computational approaches:

Sample Collection, RNA Extraction, and cDNA Synthesis

Proper sample collection and processing are fundamental to reliable qPCR results. In studies involving multiple species and conditions, careful standardization of protocols is essential:

- Sample Collection: Collect tissues at consistent time points to minimize diurnal variation effects. For example, in the grasshopper study, only specimens that molted before 10 AM were used, with all dissections occurring between 8 and 9 AM [1]. Immediately preserve tissues in RNAlater or similar RNA stabilization reagents to prevent degradation.

- RNA Extraction: Perform RNA extraction using standardized kits or protocols with DNase treatment to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. Assess RNA quality and quantity using appropriate methods such as spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio) and microfluidic analysis (RIN number) [1] [3].

- cDNA Synthesis: Use consistent amounts of high-quality RNA (e.g., 1 μg) for reverse transcription with high-efficiency reverse transcriptases. Include controls without reverse transcriptase (-RT controls) to detect genomic DNA contamination [1].

qPCR Experimental Setup and Execution

The qPCR experimental phase requires meticulous attention to technical details to ensure reproducible and accurate results:

- Primer and Probe Design: Design sequence-specific primers and probes with optimal characteristics. Probe-based qPCR is recommended over SYBR Green for preclinical and clinical samples due to superior specificity, despite higher costs [3]. For dye-based approaches, perform melting curve analysis to ensure specificity and avoid primer-dimer artifacts [3].

- Reaction Setup: Use standardized master mixes to minimize pipetting variations. Include no-template controls (NTCs) to detect contamination. The following table summarizes key reaction components for probe-based qPCR [3]:

Table 1: qPCR Reaction Components for Probe-Based Assays

| Component | Amount/Concentration |

|---|---|

| Standard DNA | 0–10^8 copies |

| Forward Primer | up to 900 nM |

| Reverse Primer | up to 900 nM |

| Probe | up to 300 nM |

| Master Mix | 1× concentration |

| Sample DNA | up to 1,000 ng |

| Nuclease-free water | to final volume |

- Thermal Cycling Conditions: Implement appropriate cycling parameters. An example protocol includes: initial enzyme activation at 95°C for 10 minutes; 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds; and annealing/extension at 60°C for 30-60 seconds [3].

- Standard Curve Implementation: Include a standard curve in each run using serial dilutions of reference standard DNA to assess PCR efficiency, which should fall between 90% and 110% [3].

Stability Analysis Using Multiple Algorithms

Reference gene stability should be assessed using multiple statistical algorithms to ensure robust selection:

- geNorm: This algorithm calculates the stability measure M for each candidate gene, with lower M values indicating higher stability. It also determines the optimal number of reference genes by calculating the pairwise variation Vn/Vn+1, with a cutoff of V < 0.15 indicating that additional reference genes are unnecessary [2] [4].

- NormFinder: This method evaluates both intra-group and inter-group variation, providing a stability value for each candidate gene. It is particularly useful for identifying the single most stable reference gene [2] [4].

- BestKeeper: This algorithm uses pairwise correlation analysis of the Cq values of candidate genes to determine the most stable references [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Reference Gene Stability Analysis Tools

| Algorithm | Primary Function | Key Output | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| geNorm | Pairwise comparison | M value (lower = more stable) | Determines optimal number of reference genes |

| NormFinder | Model-based approach | Stability value (lower = more stable) | Accounts for sample subgroups |

| BestKeeper | Correlation analysis | Standard deviation and CV | Based on raw Cq values |

Advanced Approaches and RNA-Seq Integration

RNA-Seq Data Mining for Reference Gene Discovery

The integration of RNA-Seq data has revolutionized reference gene selection by providing comprehensive expression profiles across diverse biological conditions:

- Database Utilization: Leverage existing RNA-Seq databases (e.g., TomExpress for tomato) to mine for stable genes. Calculate expression stability metrics such as variance, coefficient of variation, and expression range across relevant conditions [5].

- Lowest Variance Gene (LVG) Identification: Identify genes with minimal expression variance across targeted experimental conditions. Research indicates that classical housekeeping genes often do not have the lowest variances among genes with similar expression levels [5].

- Condition-Specific Stability: Recognize that gene stability is context-dependent. A heatmap of low variance scores (LVS) for classical housekeeping genes across different organs, tissues, and cultivars clearly demonstrates that the LVS of a gene varies depending on the conditions of interest [5].

The Gene Combination Method

A groundbreaking approach demonstrates that a stable combination of non-stable genes can outperform individual stable genes for normalization:

- Concept: The method identifies k genes whose expressions balance each other across all conditions of interest, resulting in a stable combined reference despite potential instability of individual components [5].

- Implementation: Using RNA-Seq data, the algorithm: (1) calculates the mean expression of the target gene; (2) extracts a pool of genes with similar expression levels; (3) calculates all geometric and arithmetic profiles of k genes; (4) selects the optimal set of k genes based on mean expression and lowest variance criteria [5].

- Advantages: This combinatorial approach has demonstrated superiority over commonly used housekeeping genes or other individually stably expressed genes, particularly when using comprehensive RNA-Seq databases [5].

Global Mean Normalization Strategy

For studies profiling large numbers of genes, the global mean (GM) method presents a viable alternative to traditional reference gene approaches:

- Methodology: The GM method uses the arithmetic mean of the expression of all profiled genes as a normalization factor [2].

- Application: Research on canine intestinal tissues found that the GM method was the best-performing normalization approach when profiling larger gene sets (e.g., >55 genes) [2].

- Advantages: This approach eliminates the need for reference gene selection and validation, potentially providing more robust normalization for comprehensive gene expression studies.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Reference Gene Validation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | RNAlater | Preserves RNA integrity in tissues prior to extraction |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Commercial silica-membrane kits | High-quality RNA isolation with genomic DNA removal |

| Reverse Transcriptase Kits | High-efficiency systems | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Probe-based universal master mixes | Amplification with fluorescence detection |

| Primers and Probes | Sequence-specific designs | Target amplification and detection |

| Reference Standard DNA | Serial dilution standards | Absolute quantification and efficiency calculation |

| Stability Analysis Software | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper | Statistical evaluation of reference gene stability |

The critical role of stable reference genes in accurate qPCR normalization cannot be overstated. Proper validation of reference genes for each specific experimental condition is essential for generating reliable gene expression data. Based on current evidence, the following best practices are recommended:

- Always Validate Reference Genes: Never assume reference gene stability based on previous studies or common practice. Validate candidates for each specific experimental setup [1] [2].

- Use Multiple Algorithms: Employ at least two stability analysis algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, or BestKeeper) to identify the most stable reference genes [4] [5].

- Consider Combinatorial Approaches: Explore the gene combination method, which has demonstrated superior performance compared to single reference genes [5].

- Utilize RNA-Seq Resources: Mine comprehensive RNA-Seq databases to identify potential candidate genes with stable expression patterns across conditions of interest [5].

- Implement Appropriate Controls: Include all necessary controls in qPCR experiments (NTCs, -RT controls, standard curves) to ensure technical reliability [3].

- Follow MIQE Guidelines: Adhere to MIQE guidelines to enhance experimental rigor, reproducibility, and reporting transparency [1] [6].

By implementing these practices and recognizing the critical importance of proper reference gene selection, researchers can significantly improve the accuracy and reliability of their qPCR-based gene expression studies, leading to more valid biological conclusions and advancing scientific knowledge across diverse fields from basic research to drug development.

The accurate normalization of reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) data is a cornerstone of reliable gene expression analysis. For decades, classic housekeeping genes (HKGs), such as ACTB (β-actin) and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), have been routinely employed as reference genes based on the assumption that their expression remains constant across all cell types and experimental conditions. A growing body of evidence, however, fundamentally challenges this assumption, demonstrating that the expression of these genes can be highly variable. This variability poses a significant risk of data misinterpretation. This application note synthesizes recent evidence illustrating the limitations of classic HKGs and provides detailed, evidence-based protocols for the rigorous selection and validation of stable reference genes, with a specific focus on leveraging RNA-Seq data to inform this critical process.

RT-qPCR is renowned for its sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility, making it a ubiquitous tool for gene expression validation, particularly for RNA-Seq data [7]. However, the accuracy of its results is profoundly dependent on proper normalization to account for technical variations introduced during RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and PCR amplification [8] [9]. The use of unvalidated reference genes is a pervasive source of inaccurate conclusions in gene expression studies [8].

The term "housekeeping gene" refers to a gene involved in basic cellular maintenance functions, presumed to be expressed constitutively at a constant level. This presumption has led to the widespread, often unquestioned, use of genes like ACTB, GAPDH, 18S rRNA, and TUBB (β-tubulin) as internal controls. Yet, it is now unequivocally established that no universal reference gene exists that is stable under all experimental conditions [10] [11] [12]. The expression of these classic genes can be modulated by a multitude of factors, including tissue type, developmental stage, disease state (e.g., cancer), and specific experimental treatments such as cellular differentiation, stress, and metabolic alterations [10] [9] [12]. Consequently, normalizing to an unstable reference gene can obscure genuine expression changes of target genes or, worse, create artifactual ones, leading to flawed biological interpretations.

Evidence of Expression Variability in Classic Housekeeping Genes

Numerous systematic studies across diverse biological models have quantified the instability of classic HKGs. The following tables summarize key findings from recent investigations, highlighting the poor performance of traditional reference genes compared to more stable alternatives.

Table 1: Instability of Classic Housekeeping Genes Across Different Biological Models

| Biological Context | Classic HKG(s) Tested | Evidence of Instability / Stable Alternatives | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| iPS Cell Reprogramming (Mouse) | Actb, Gapdh, Hprt, Rps18, Tbp | Least Stable: Rps18, Hprt, Tbp, Actb. Most Stable: Atp5f1, Pgk1, Gapdh [12]. | Demonstrates that the process of reprogramming itself, which involves metabolic and structural remodeling, drastically affects the expression of common reference genes. |

| Adipocyte Differentiation (3T3-L1 Cells) | Actb, Gapdh, Rn18s | Expression levels of reference genes changed over time, even in non-differentiating control cells. Stable genes: Ppia and Tbp [10]. | Highlights that even in the absence of an induced differentiation signal, cell culture conditions and time can alter the expression of classic HKGs. |

| Human Cancer & Normal Cell Lines (20 lines) | ACTB, GAPDH, UBC | Classic genes showed considerable variation. Novel stable genes proposed: IPO8, PUM1, HNRNPL, SNW1, CNOT4 [11]. | Underlines the challenge of comparing gene expression across different cell lines and the inadequacy of standard HKGs for this purpose. |

| Aquatic Plant (Lotus) | ACT, GAPDH, TUA | Stability was highly context-dependent. Best genes varied by tissue: e.g., TBP & UBQ in rhizomes; TBP & EF-1α in flowers [13]. | Confirms that the instability of classic HKGs and the context-dependence of optimal reference genes is a universal principle across kingdoms. |

Table 2: Impact of Experimental Conditions on Common Housekeeping Genes in Spinach

| Experimental Condition | Classic HKG(s) Tested | Performance & Stable Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Different Organs | 18S rRNA, Actin, GAPDH, TUBα | Most Stable: ARF, Actin, COX, CYP, RPL2 [9]. |

| Heat Stress | 18S rRNA, Actin, GAPDH, TUBα | Most Stable: ARF, Actin, COX, CYP, RPL2 [9]. |

| Salt & Alkali Stress | 18S rRNA, Actin, GAPDH, TUBα | Most Stable: 18S rRNA, ARF, COX, CYP, EF1α, RPL2 [9]. |

The following diagram illustrates the primary cellular processes and experimental perturbations that are known to influence the expression of classic housekeeping genes, thereby compromising their utility as normalizers.

Protocols for Rigorous Reference Gene Selection and Validation

Given the documented pitfalls of classic HKGs, a systematic and evidence-based approach to reference gene selection is imperative. The following protocols outline a robust workflow, from initial candidate identification to final validation.

Protocol 1: Selection of Candidate Reference Genes from RNA-Seq Data

Principle: RNA-Seq datasets provide a genome-wide, quantitative overview of transcript abundance and variability across all samples in a study. This makes them an ideal resource for pre-selecting candidate reference genes with inherently stable expression before RT-qPCR validation [7] [14].

Workflow:

- Data Input: Compile a gene expression matrix from your RNA-Seq data where rows represent genes and columns represent samples. Expression values should be in TPM (Transcripts Per Million) or FPKM for cross-sample comparability [7].

- Initial Filtering: Filter the matrix to include only genes expressed above a minimal threshold in all samples (e.g., TPM > 0 in all libraries) [7].

- Stability Filtering: Apply sequential statistical filters to identify stable genes.

- Filter 1: Low Variation. Calculate the standard deviation (SD) of

log2(TPM)for each gene across all samples. Retain genes with SD < 1 [7]. - Filter 2: No Outliers. Ensure that for each gene, no single sample's

log2(TPM)value deviates from the mean by more than a factor of 2 (i.e.,|log2(TPMi) - mean(log2TPM)| < 2) [7]. - Filter 3: High Expression. Retain genes with a high average expression level (e.g.,

mean(log2TPM) > 5) to ensure they are readily detectable by RT-qPCR [7]. - Filter 4: Low Coefficient of Variation (CV). Calculate the CV of the

log2(TPM)values and retain genes with CV < 0.2 [7].

- Filter 1: Low Variation. Calculate the standard deviation (SD) of

- Output: The resulting shortlist of genes serves as your candidate reference genes for downstream experimental validation. Tools like GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) can automate this entire process [7].

The workflow for this RNA-Seq-based selection process is summarized in the following diagram.

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of Candidate Genes via RT-qPCR

Principle: Candidates identified in silico must be empirically tested for expression stability using RT-qPCR across all experimental conditions (e.g., all time points, tissues, or treatments). Their stability is then ranked using dedicated algorithms [9] [12].

Workflow:

- Sample Preparation:

- Collect biological replicates (recommended n ≥ 3) for every condition in your study.

- Extract total RNA using a reliable kit, ensuring genomic DNA removal. Assess RNA integrity (RIN > 8.0) and purity (A260/280 ≈ 2.0).

- Synthesize cDNA using a high-capacity reverse transcription kit with a mixture of random hexamers and oligo-dT primers.

- qPCR Assay:

- Design intron-spanning primers for each candidate gene with high amplification efficiency (90–110%) and specificity (confirmed by melt curve analysis) [11].

- Run qPCR reactions for all candidate genes across all cDNA samples in technical replicates.

- Record the quantification cycle (Cq) values.

- Stability Analysis:

- Input the Cq values into multiple stability analysis algorithms. The consensus of multiple tools provides the most robust result.

- geNorm: Calculates a stability measure (M); lower M indicates greater stability. Also determines the optimal number of reference genes by pairwise variation (V) [9] [12].

- NormFinder: Evaluates intra- and inter-group variation, providing a stability value; lower values indicate greater stability [9] [12].

- BestKeeper: Relies on the SD of the Cq values; genes with SD > 1 are considered unstable [9].

- RefFinder is a comprehensive tool that integrates the results from geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the comparative ΔCt method to provide an overall ranking [10].

- Input the Cq values into multiple stability analysis algorithms. The consensus of multiple tools provides the most robust result.

- Final Selection: Select the top 2-3 most stable genes for normalization. Using multiple genes for normalization significantly improves reliability [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Reagents and Software for Reference Gene Validation

| Item | Function/Description | Example Products/Citations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-integrity, genomic DNA-free total RNA. | RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) [12], TRIzol-based methods [9]. |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Synthesis of first-strand cDNA from RNA templates. | High-Capacity cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems), Maxima H Minus Kit (Thermo Fisher) [11]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | SYBR Green or probe-based mix for quantitative PCR. | FastStart Essential DNA Green Master (Roche) [10], Power SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems). |

| Stability Analysis Software | Algorithms to rank candidate genes based on Cq value stability. | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, RefFinder [10] [9]. |

| RNA-Seq Analysis Tool | Software to pre-select candidate genes from transcriptomic data. | GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) [7]. |

| Gamma-secretase modulators | Gamma-Secretase Modulators for Alzheimer's Research | Explore gamma-Secretase Modulators for AD research. These small molecules shift Aβ production to shorter peptides. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| 5-Bromo-2-[4-(tert-butyl)phenoxy]aniline | 5-Bromo-2-[4-(tert-butyl)phenoxy]aniline, CAS:946700-34-1, MF:C16H18BrNO, MW:320.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The assumption that classic housekeeping genes like ACTB and GAPDH are stably expressed is a dangerous oversimplification that can critically undermine the validity of gene expression studies. As demonstrated across diverse models—from differentiating adipocytes to reprogramming stem cells—these genes exhibit significant, context-dependent variability. Adherence to the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines is paramount. This involves moving beyond tradition and adopting a rigorous, systematic pipeline that leverages RNA-Seq data for intelligent candidate selection followed by mandatory experimental validation of reference gene stability for each specific experimental system. This evidence-based approach is not merely a best practice but a fundamental necessity for generating accurate, reliable, and biologically meaningful gene expression data.

The selection of stable reference genes is a critical prerequisite for obtaining accurate and reliable gene expression data from reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). Traditionally, this process relied on a limited set of candidate housekeeping genes, which are now known to exhibit significant expression variability across different biological contexts [8]. The emergence of RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has transformed this paradigm by enabling unbiased, genome-wide screening for potential reference genes with superior stability profiles. This application note details how RNA-Seq serves as a powerful discovery tool for identifying optimal reference genes, outlining specific advantages over traditional methods and providing detailed protocols for implementation.

RNA-Seq provides a comprehensive snapshot of the entire transcriptome, quantifying thousands of genes simultaneously across diverse experimental conditions [15]. This global perspective allows researchers to move beyond the constraints of pre-selected candidate genes and mine transcriptomic data for novel, highly stable reference genes that would remain undetected using conventional approaches. Furthermore, the statistical robustness derived from analyzing extensive RNA-Seq datasets empowers the identification of gene combinations whose collective expression remains constant, even when individual genes exhibit some variability [16].

Advantages of RNA-Seq in Reference Gene Discovery

The transition from traditional candidate approaches to RNA-Seq-based discovery offers several distinct advantages that enhance the accuracy and efficiency of reference gene selection.

Unbiased Genome-Wide Screening

Unlike methods that test a pre-defined set of genes, RNA-Seq enables comprehensive profiling of all expressed genes in a transcriptome. This allows for the discovery of novel, stable reference genes that are not among conventionally used housekeeping genes. Research demonstrates that stable combinations of genes identified from RNA-Seq data can outperform standard reference genes for RT-qPCR normalization [16].

Handling of Large-Scale Data

RNA-Seq datasets provide the extensive data necessary for robust statistical analysis of gene expression stability. Specialized software tools like Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) have been developed specifically to leverage these datasets, applying multiple filtering criteria—including expression level, variability, and coefficient of variation—to identify optimal reference candidates from thousands of genes [7].

The growing availability of public RNA-Seq repositories enables researchers to conduct in silico stability analyses without generating new sequencing data. Studies have successfully utilized comprehensive databases like TomExpress (for tomato) to identify optimal reference gene combinations, demonstrating the utility of leveraging existing transcriptomic resources [16].

Table 1: Key Advantages of RNA-Seq Over Traditional Methods for Reference Gene Screening

| Feature | Traditional Candidate Approach | RNA-Seq Discovery Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Limited to pre-selected genes | Genome-wide, unbiased |

| Discovery Potential | Low; restricted to known genes | High; can identify novel stable genes |

| Statistical Power | Limited by number of candidates | High; uses entire transcriptome dataset |

| Data Resources | Requires new experiments | Can leverage public repositories |

| Output | Individual stable genes | Can identify stable gene combinations |

Quantitative Assessment of Gene Stability from RNA-Seq Data

Transforming raw RNA-Seq data into a validated list of reference gene candidates requires a multi-step analytical process focused on quantifying expression stability.

Stability Metrics and Filtering Criteria

Different algorithms employ specific metrics and thresholds to identify stably expressed genes. The following criteria are commonly applied to filter candidate genes:

- Expression Threshold: Minimum expression level (e.g., log2(TPM) > 5) to ensure reliable detection by RT-qPCR [7]

- Variability Threshold: Maximum expression variability (e.g., standard deviation of log2(TPM) < 1) across conditions [7]

- Coefficient of Variation: Maximum coefficient of variation (< 0.2) to account for relative stability [7]

- Expression Range: No exceptional expression in any single condition (e.g., within twice the average of log2 expression) [7]

Software tools like GSV implement these criteria systematically, processing transcripts per million (TPM) values from multiple samples to generate ranked lists of candidate reference genes [7].

From Individual Genes to Stable Combinations

Recent methodological advances focus on identifying combinations of genes (k-genes) whose geometric mean expression remains stable across conditions, even when individual components show some variability. This approach has demonstrated superiority over single reference genes in normalization accuracy [16].

The algorithm for identifying these optimal combinations typically involves:

- Calculating the mean expression of the target gene

- Extracting a pool of genes with similar or greater mean expression

- Computing all possible geometric and arithmetic means of k genes from this pool

- Selecting the optimal set that meets both mean expression and minimal variance criteria [16]

Figure 1: Computational workflow for identifying stable reference genes from RNA-Seq data.

Experimental Design and RNA-Seq Protocol

Proper experimental design is fundamental to generating RNA-Seq data that will yield reliable reference gene candidates.

Experimental Considerations

- Biological Replicates: Include sufficient replicates (typically 3-5) per condition to adequately capture biological variation [15]

- Condition Coverage: Ensure RNA-Seq data encompasses all experimental conditions relevant to future qPCR studies

- RNA Quality: Use high-quality RNA (RIN ≥ 8) to minimize technical artifacts [17] [18]

- Sequencing Depth: Aim for adequate depth (typically 20-30 million reads per sample for standard organisms) to reliably quantify mid-to-low abundance transcripts [15]

Library Preparation and Sequencing

The following protocol outlines key steps for generating RNA-Seq data suitable for reference gene discovery:

RNA Extraction

Library Preparation

- Select appropriate RNA enrichment method (poly-A selection for mRNA, ribosomal depletion for total RNA)

- Use strand-specific protocols to preserve transcript orientation information

- Fragment RNA/cDNA to appropriate size (typically 200-500 bp) [15]

Sequencing

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Library Preparation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | TRIzol reagent, Direct-Zol RNA microprep columns | Isolation of high-quality total RNA from biological samples |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA kits, NanoDrop spectrophotometer | Verification of RNA integrity and purity before library construction |

| Library Preparation | Poly(A) selection beads, rRNA depletion kits, strand-specific cDNA synthesis kits | Enrichment for desired RNA species and conversion to sequencing-ready libraries |

| Sequencing | Illumina sequencing kits, NovaSeq/X series flow cells | Generation of high-throughput sequence reads from prepared libraries |

From RNA-Seq Candidates to qPCR Validation

Genes identified through computational analysis of RNA-Seq data require rigorous experimental validation by qPCR.

Validation Workflow

The transition from in silico candidates to validated reference genes follows a systematic process:

- Candidate Selection: Select 3-5 top-ranked genes from RNA-Seq analysis plus 1-2 traditional housekeeping genes for comparison

- qPCR Assay Design: Design and validate qPCR assays with high amplification efficiency (90-110%) and specificity [18]

- Experimental Testing: Measure candidate expression across all relevant biological conditions

- Stability Analysis: Analyze results using multiple algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, RefFinder) [18] [20]

- Final Selection: Choose the most stable gene or gene combination for normalization

Case Study Validation

A study on Phytophthora capsici validation demonstrated this process effectively. Researchers identified translation elongation factor 1-α (ef1), 40S ribosomal protein S3A (ws21), and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (ubc) as the most stable reference genes during host infection using this combined approach [18].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for validating RNA-Seq-derived reference genes using qPCR.

RNA-Seq has emerged as a powerful discovery tool that significantly enhances the process of reference gene selection for qPCR normalization. By enabling comprehensive, genome-wide stability screening, RNA-Seq moves beyond the limitations of traditional candidate approaches and allows researchers to identify optimal reference genes with greater confidence and efficiency. The integration of computational screening from RNA-Seq data with rigorous qPCR validation represents a robust framework for achieving accurate gene expression normalization across diverse biological contexts. As RNA-Seq technologies continue to advance and computational tools become more sophisticated, this approach will likely become the standard practice for reference gene selection in gene expression studies.

In the realm of gene expression analysis, reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) remains the gold standard for validating transcriptomic data, including those generated by RNA-Seq [17]. The accuracy of this technique, however, is profoundly dependent on normalization using reliable internal controls, known as reference genes (RGs). Ideal reference genes are characterized by two fundamental properties: high expression across the experimental conditions and low variation in their expression profiles [11] [7]. The failure to employ such stable genes for normalization can lead to biased results, reduced precision, and a misinterpretation of biological phenomena [21] [7]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on qPCR reference gene selection from RNA-Seq data, outlines the definitive criteria for ideal candidate genes and provides detailed protocols for their identification and validation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Critical Criteria for Ideal Candidate Genes

The selection of candidate genes is a critical first step that should not rely on convention alone. Genes traditionally used as housekeeping genes, such as GAPDH and ACTB, often exhibit significant variability under different experimental conditions, making them unsuitable for many studies [21] [11]. Instead, a systematic approach should be used to define candidates based on the following pillars:

- High Expression Level: Genes with low expression levels are more susceptible to technical variations and may fall below the reliable detection limit of RT-qPCR. A high level of expression ensures robust and reproducible quantification [7]. In practice, this can be defined using Transcripts Per Million (TPM) from RNA-Seq data; for instance, an average log2(TPM) greater than 5 is a suggested threshold [7].

- Low Expression Variation: The core function of a reference gene is to remain invariant. Expression stability must be evaluated across all biological conditions relevant to the study (e.g., different tissues, treatments, or disease states). Statistical measures like the coefficient of variation (CV) and standard deviation of log2(TPM) values are key metrics. A CV below 0.2 and a standard deviation below 1 are strong indicators of stability [11] [7].

- Consistent Expression Profile: The gene should not display exceptional expression in any single sample or condition. A useful filter is to require that the log2(TPM) value in any library does not deviate by more than twice the average log2(TPM) across all libraries [7].

- Lack of Coregulation with Test Genes: Candidate genes should not be part of a coregulated network that includes the target genes under investigation. Using multiple genes from the same pathway can introduce bias, as statistical algorithms like GeNorm may incorrectly prioritize them for their co-stability rather than true invariant expression [11].

Table 1: Established Stable Reference Genes from Recent Studies

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Experimental Context | Key Stability Metric | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLR2A | RNA Polymerase II Subunit A | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) | Identified as most stable by GeNorm and equivalence test [21] | [21] |

| CNOT4 | CCR4-NOT Transcription Complex Subunit 4 | Pan-Cancer and Normal Human Cell Lines | Most stable gene upon serum starvation; low CV in RNA-Seq meta-analysis [11] | [11] |

| SNW1 | SNW Domain Containing 1 | Pan-Cancer and Normal Human Cell Lines | Top-ranked stable gene from Human Protein Atlas RNA HPA data [11] | [11] |

| IPO8 | Importin 8 | Pan-Cancer and Normal Human Cell Lines | Consistently ranked among the most stable genes [11] | [11] |

| ARF1 | ADP-ribosylation factor 1 | Honeybee Tissues & Development | Most stable gene across tissues and developmental stages [22] | [22] |

A Workflow for Identification from RNA-Seq Data

RNA-Seq data provides a powerful foundation for pre-selecting candidate reference genes before costly and time-consuming RT-qPCR validation. The following workflow, which can be implemented using tools like the "Gene Selector for Validation" (GSV) software, ensures a systematic selection process [7].

Diagram 1: Candidate gene selection workflow from RNA-Seq data.

Protocol 1: Selecting Candidate Genes Using GSV Software

- Input Preparation: Compile a transcript quantification matrix (e.g., TPM values) for all samples in your RNA-Seq dataset. This file can be in .xlsx, .txt, or .csv format.

- Software Execution:

- Load the quantification file into the GSV software.

- For reference gene selection, apply the standard filtering criteria as illustrated in Diagram 1 [7].

- Execute the analysis. The software will output a ranked list of genes passing all filters.

- Output Analysis: The resulting list represents genes with high expression and low variation across your specific experimental conditions. The top-ranked genes are prime candidates for downstream RT-qPCR validation.

Experimental Validation of Candidate Genes

Candidates identified from RNA-Seq must be empirically validated using RT-qPCR. This protocol details the steps from primer design to final stability assessment.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for reference gene validation.

Protocol 2: RT-qPCR Validation of Candidate Genes

RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis:

- Extract total RNA from biological replicates (recommended n ≥ 5 per condition) using a commercial kit (e.g., TRIzol/RNeasy). Assess RNA integrity (RIN > 8) and purity (A260/A280 ≈ 2.0) [17] [22].

- Convert 200-1000 ng of total RNA to cDNA using a robust reverse transcription kit (e.g., Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit or High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit). Use a consistent amount of RNA and the same kit across all samples to minimize technical variation [11].

qPCR Primer Design and Validation:

- Design: Design primers with the following criteria using tools like Primer Premier 5 or the qPrimerDB 2.0 database [23] [22]:

- Amplicon length: 80-150 bp.

- Exon-spanning or intron-flanking to avoid genomic DNA amplification.

- Check for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in primer binding sites.

- Validation: Validate primer specificity by:

- Agarose gel electrophoresis: A single sharp band of the expected size should be present [11].

- Melting curve analysis: A single peak indicates a specific PCR product [11].

- Standard curve: Generate a 5-10 point serial dilution series to calculate PCR amplification efficiency (E). Ideally, E should be between 90% and 110%, with a correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.99 [22].

- Design: Design primers with the following criteria using tools like Primer Premier 5 or the qPrimerDB 2.0 database [23] [22]:

qPCR Execution:

- Perform reactions in technical replicates on a calibrated real-time PCR instrument.

- Use a standardized reaction volume and master mix to ensure consistency.

- Include no-template controls (NTCs) to check for contamination.

Data Analysis and Stability Assessment:

- Collect quantification cycle (Cq) values.

- Analyze the expression stability of each candidate gene using multiple algorithms to ensure a robust conclusion. The following table summarizes key tools:

Table 2: Key Reagents and Software for Reference Gene Validation

| Category | Item | Function/Description | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Prep | RNA Extraction Kit | Isolves high-integrity total RNA, free of genomic DNA | TRIzol Reagent, RNeasy Kit [17] [22] |

| cDNA Synthesis | Reverse Transcriptase Kit | Converts RNA to cDNA; critical for sensitivity and linearity | Maxima First Strand Kit, High-Capacity Kit [11] |

| qPCR | qPCR Master Mix | Contains enzymes, dNTPs, buffer for efficient amplification | TB Green Premix Ex Taq [22] |

| Primer Design | Primer Design Tool | Designs specific, efficient qPCR primers | Primer Premier 5, qPrimerDB 2.0 [23] [22] |

| Stability Analysis | Statistical Algorithms | Software suites to rank candidate genes by stability | GeNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, RefFinder [21] [22] |

The rigorous definition and selection of ideal candidate genes—those with high expression and low variation—is a non-negotiable prerequisite for generating reliable gene expression data. By integrating in-silico selection from RNA-Seq datasets with meticulous experimental validation using RT-qPCR, researchers can establish a firm foundation for their studies. The protocols and criteria outlined in this application note provide a clear roadmap for scientists to confidently select reference genes, thereby enhancing the accuracy and reproducibility of their research in drug development and beyond.

A Step-by-Step Workflow: From RNA-Seq Data to Candidate Gene Selection

In the analysis of gene expression data, the selection of optimal reference genes is a critical step for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of results obtained through quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). Reference genes, used for data normalization, must exhibit stable expression under various experimental conditions to avoid misinterpretation of expression patterns for target genes [8]. Traditional approaches often relied on so-called "housekeeping" genes presumed to maintain constant expression; however, substantial evidence now demonstrates that the expression of these genes can vary significantly across different tissues, developmental stages, and experimental conditions [24].

The emergence of high-throughput transcriptomic technologies, particularly RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), has enabled a more systematic and data-driven approach to identifying stably expressed genes. To harness this potential, dedicated bioinformatics tools have been developed. These tools leverage whole-transcriptome data to identify optimal reference genes with high expression stability, moving the selection process beyond conventional assumptions [24]. This shift is crucial, as the use of inappropriate reference genes remains a common source of error that can compromise the validity of gene expression studies [7] [25].

This article focuses on introducing the software tools available for this purpose, with particular emphasis on the Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) software, and provides detailed protocols for their application in a research workflow centered on qPCR validation of RNA-seq data.

The Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) is a dedicated software tool developed to identify optimal reference and variable candidate genes directly from RNA-seq data for subsequent validation by RT-qPCR [7] [25]. It was developed to address specific limitations of existing methods, such as their inability to handle large gene sets from RNA-seq and to filter out stably expressed genes with low expression levels that are unsuitable for qPCR detection [25] [26].

GSV is implemented in Python and utilizes libraries such as Pandas, Numpy, and Tkinter, the latter providing a user-friendly graphical interface that eliminates the need for command-line interaction [7] [25]. The software accepts common file formats (e.g., .xlsx, .txt, .csv) containing transcript-per-million (TPM) values, which are used for cross-sample comparison of gene expression.

Core Algorithm and Workflow

The algorithm of GSV applies a filtering-based methodology adapted from the work of Li et al. [7] [25]. It processes the transcriptome quantification tables by applying a series of stringent criteria to select genes that are both stable and highly expressed.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the GSV software for selecting both reference and validation candidate genes:

Table 1: Filtering Criteria for Reference Genes in GSV Software

| Criterion | Equation | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universal Expression | TPM > 0 (Eq. 1) |

Gene must have non-zero expression in all analyzed libraries. | Ensures the gene is detectable across all conditions. |

| Low Variability | σ(log₂(TPM)) < 1 (Eq. 2) |

Standard deviation of log-transformed expression must be less than 1. | Selects genes with minimal expression fluctuation. |

| Consistent Expression | |logâ‚‚(TPM) - mean| < 2 (Eq. 3) |

No individual expression value deviates from the mean by more than 2-fold. | Eliminates genes with outlier expression in any sample. |

| High Expression | mean(logâ‚‚(TPM)) > 5 (Eq. 4) |

Average log-transformed expression must be greater than 5. | Ensures sufficient expression for reliable qPCR detection. |

| Low Dispersion | CV < 0.2 (Eq. 5) |

Coefficient of variation must be less than 0.2. | Further refines selection based on normalized variability. |

For identifying variable genes suitable for experimental validation of transcriptome results, GSV applies more general filters: expression greater than zero in all samples (Eq. 1), high variation between libraries (standard deviation > 1, Eq. 6), and a high level of expression (average logâ‚‚(TPM) > 5, Eq. 4) [7] [25].

Comparison with Other Tools and Methods

While GSV provides a specialized approach for pre-qPCR planning from RNA-seq data, other software tools are commonly used to assess gene expression stability after qPCR data has been generated. These tools employ various algorithms to rank candidate reference genes based on their stability measured in Cq values.

Table 2: Comparison of Gene Stability Assessment Tools

| Software/Tool | Primary Input Data | Methodology | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSV | RNA-seq (TPM values) | Stepwise filtering based on expression level and variability. | Proactive selection from transcriptome; filters low-expression genes; user-friendly GUI. | Requires pre-existing RNA-seq data. |

| GeNorm [27] [8] | qPCR (Cq values) | Pairwise comparison of expression ratios between candidate genes. | Determines the optimal number of reference genes; provides stability measure (M-value). | Limited to small sets of genes; cannot run without a reference gene. |

| NormFinder [27] [8] | qPCR (Cq values) | Model-based approach estimating intra- and inter-group variation. | Sensitive to systematic differences between sample groups; provides stability value. | Requires sample group information for best performance. |

| BestKeeper [27] | qPCR (Cq values) | Based on pairwise correlation analysis of Cq values. | Calculates geometric mean of candidate genes; provides index of stability. | Best for analyzing fewer than 10 candidates; sensitive to co-regulated genes. |

| RefFinder [27] | qPCR (Cq values) | Algorithm integration and ranking aggregation. | Combines results from GeNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and Delta-Ct methods; provides comprehensive ranking. | Aggregated result may mask algorithm-specific findings. |

The integration of these tools into a cohesive workflow represents best practices in the field. A typical pipeline involves using GSV for initial candidate selection from RNA-seq data, followed by experimental validation using qPCR, and finally, confirmation of stability with tools like RefFinder that leverage multiple algorithms [27].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Case Study: Application in Sweet Potato Research

A comprehensive study on sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) exemplifies the practical application of reference gene validation [27]. Researchers evaluated ten candidate reference genes across four different tissues (fibrous root, tuberous root, stem, and leaf) using the RefFinder algorithm, which integrates GeNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the comparative ΔCt method.

Key Findings:

- Most stable genes: IbACT, IbARF, and IbCYC showed the lowest variation in expression across tissues.

- Least stable genes: IbGAP, IbRPL, and IbCOX displayed the highest variation and were deemed unsuitable as reference genes.

- Tissue-specific performance: The most stable genes varied by tissue type. For example, in tuberous roots, IbGAP, IbARF, and IbACT were most stable, whereas IbCYC, IbARF, and IbTUB were optimal for stems.

This study highlights the importance of empirical validation, as traditionally used reference genes like IbGAP performed poorly while other candidates demonstrated superior stability.

Detailed Protocol: Reference Gene Validation

The following workflow integrates computational selection with experimental validation, representing a complete protocol for establishing reliable reference genes in a new study system.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

- Extract total RNA using commercial kits (e.g., TIANGEN RNAprep Plant Kit) [13]. For challenging tissues rich in polyphenols or polysaccharides, include additives like PVP K30 during grinding.

- Treat all RNA samples with DNase I to eliminate genomic DNA contamination.

- Assess RNA integrity using agarose gel electrophoresis or specialized instruments like Agilent Bioanalyzer. Note that traditional RNA Integrity Number (RIN) metrics may require adjustment for plant tissues containing chloroplast RNA [8].

cDNA Synthesis

- Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcription kits with random hexamers and/or oligo-dT primers (e.g., TIANGEN FastQuant RT Kit or SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System) [13] [28].

- Use consistent amounts of input RNA across all samples (typically 0.5-1 µg).

- Include a no-reverse-transcriptase control to confirm the absence of genomic DNA amplification.

Primer Design and Validation

- Design primers for candidate reference genes using software such as Primer Premier 5.0 or Oligo 7 [13].

- Target amplicon lengths of 80-300 base pairs for optimal qPCR efficiency.

- Validate primer specificity through melt curve analysis and confirmation of a single peak. Verify amplicon size by gel electrophoresis and consider sequencing PCR products to confirm target identity [13].

- Determine primer efficiency using a standard curve with serial cDNA dilutions (e.g., 5-fold dilutions). Acceptable efficiency typically ranges from 90% to 110%, with a correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.990 [13].

qPCR Execution

- Perform reactions in technical triplicates using SYBR Green-based chemistry (e.g., TIANGEN Talent qPCR PreMix) on a validated qPCR system [13].

- Use a standardized thermal cycling protocol: initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturation) and 60°C for 1 minute (annealing/extension) [13].

- Include no-template controls (NTCs) to detect potential contamination.

Data Analysis and Stability Assessment

- Export Cq (quantification cycle) values for analysis.

- Convert Cq values to relative quantities using the formula

E^{-ΔCq}, where E represents amplification efficiency and ΔCq is the difference between each sample's Cq and the minimum Cq value across all samples [13]. - Analyze the converted data with stability assessment tools such as GeNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper individually, or use the comprehensive RefFinder platform which integrates all three methods [27] [13].

- Select the top-ranked, most stable genes for normalization of target gene expression data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Reference Gene Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | TIANGEN RNAprep Plant Kit [13] | Isolation of high-quality total RNA from plant tissues. |

| DNA Removal | RNase-free DNase I [13] | Elimination of genomic DNA contamination from RNA samples. |

| cDNA Synthesis | TIANGEN FastQuant RT Kit [13]; SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System [28] | Reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA for qPCR amplification. |

| qPCR Master Mix | TIANGEN Talent qPCR PreMix (SYBR Green) [13]; 2× SuperReal PreMix Plus [13] | Provides optimized buffer, enzymes, and fluorescent dye for qPCR detection. |

| Reference Gene Analysis Software | GSV (Gene Selector for Validation) [7] [25]; GeNorm [27] [24]; NormFinder [27] [24]; BestKeeper [27]; RefFinder [27] | Computational tools for selecting and validating stable reference genes. |

| Primer Design Software | Primer Premier 5.0 [13]; Oligo 7 [13] | Design of specific primer pairs for candidate reference genes. |

| 3-Fluoro-DL-valine | 3-Fluoro-DL-valine, CAS:43163-94-6, MF:C5H10FNO2, MW:135.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,2,2-trichloro-1-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethanone | 2,2,2-Trichloro-1-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethanone|CAS 30030-90-1 |

The integration of dedicated software tools like GSV with established stability assessment algorithms represents a robust framework for reference gene selection in the era of transcriptomics. The critical lesson from recent research is that traditional housekeeping genes frequently fail to maintain stable expression across diverse biological conditions, necessitating empirical validation for each experimental system [27] [24].

Successful implementation of this approach requires careful attention to several best practices:

- Utilize RNA-seq Data Proactively: When available, use tools like GSV to screen entire transcriptomes for ideal candidate genes before qPCR validation, rather than relying on literature-based assumptions [7] [25].

- Validate Across Specific Conditions: Always assess reference gene stability across the exact same tissues, developmental stages, and experimental conditions used in your target gene expression studies [27] [13].

- Employ Multiple Algorithms: Use comprehensive tools like RefFinder or run multiple stability assessment programs (GeNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper) to obtain a consensus on the most stable reference genes [27].

- Use Multiple Reference Genes: For the most reliable normalization, incorporate the geometric mean of at least two validated reference genes as recommended by geNorm and other algorithms [27] [8].

This systematic approach to reference gene selection, combining computational power with rigorous experimental validation, ensures the accuracy and reliability of gene expression studies, ultimately strengthening the conclusions drawn from qPCR data in both basic research and drug development contexts.

This application note provides a detailed protocol for the preparation and interpretation of Transcripts Per Million (TPM) data and expression matrices, specifically framed within the context of selecting optimal reference genes for RT-qPCR validation from RNA-seq datasets. As the reliability of qPCR data critically depends on proper normalization using stably expressed reference genes, RNA-seq analysis serves as a powerful discovery tool to identify these candidates. We present a standardized workflow covering TPM calculation, data quality assessment, matrix construction, and cross-platform validation procedures, enabling researchers to generate robust, reproducible expression data for downstream qPCR experiments in drug development and clinical research settings.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the predominant method for transcriptome profiling, generating vast datasets that require careful normalization to yield biologically meaningful results [29] [15]. The selection of appropriate quantification measures is particularly crucial when RNA-seq data serves as the foundation for selecting reference genes for RT-qPCR studies, as improper normalization can lead to the identification of unreliable reference genes that compromise subsequent expression analyses.

Several quantification measures have been developed to normalize RNA-seq data for technical variables such as sequencing depth and gene length [30] [31]. Sequencing depth refers to the total number of reads per sample, which varies between experiments and can significantly impact expression estimates. Gene length normalization is necessary because longer transcripts typically accumulate more reads than shorter transcripts at identical expression levels [31]. The most common normalization methods include:

- RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase Million): Developed for single-end RNA-seq experiments

- FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Million): Adapted for paired-end RNA-seq where two reads can correspond to a single fragment

- TPM (Transcripts Per Kilobase Million): A recently popularized measure that changes the order of operations in normalization

- Normalized Counts: Used for between-sample comparisons and differential expression analysis

The choice among these measures depends heavily on the analytical goal—whether comparing expression within a single sample or between multiple samples—and has significant implications for identifying stably expressed genes suitable for qPCR normalization [32] [31].

Table 1: Comparison of RNA-seq Quantification Methods

| Method | Full Name | Primary Use | Normalization Factors | Sum of Normalized Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPKM | Reads Per Kilobase Million | Within-sample comparisons | Sequencing depth, Gene length | Variable across samples |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase Million | Within-sample comparisons | Sequencing depth, Gene length | Variable across samples |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Kilobase Million | Within-sample comparisons | Gene length, Sequencing depth | Constant across samples (1 million) |

| Normalized Counts | - | Between-sample comparisons | Library composition, Size factors | Variable across samples |

Theoretical Foundation of TPM

Calculation Methodology

TPM represents the relative abundance of transcripts in a sample, normalized for both transcript length and sequencing depth. The key innovation of TPM lies in its order of operations: it normalizes for gene length first, then for sequencing depth, which results in a consistent sum across all samples [30]. This approach differs fundamentally from RPKM/FPKM and provides significant advantages for comparative analyses.

The TPM calculation involves three sequential steps:

Divide read counts by gene length: For each gene, divide the raw read counts by the length of the gene in kilobases, yielding Reads Per Kilobase (RPK). [ RPKi = \frac{\text{Read counts}i}{\text{Gene length in kb}} ]

Calculate scaling factor: Sum all RPK values in the sample and divide by 1,000,000 to obtain a "per million" scaling factor. [ \text{Scaling factor} = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} RPKi}{1,000,000} ]

Normalize RPK by scaling factor: Divide each RPK value by the scaling factor to obtain TPM. [ TPMi = \frac{RPKi}{\text{Scaling factor}} ]

This calculation results in the sum of all TPM values in a sample equaling 1,000,000, enabling direct comparison of the proportional expression of genes across different samples [30] [31]. If the TPM for gene A is 3.33 in both Sample 1 and Sample 2, this indicates that the exact same proportion of total reads mapped to gene A in both samples, which would not necessarily be true for RPKM or FPKM values of the same magnitude.

Advantages for Reference Gene Selection

TPM offers particular advantages for identifying candidate reference genes from RNA-seq data:

- Proportionality: The constant sum enables immediate recognition of expression proportions without additional calculations

- Cross-sample comparability: Technical variations in sequencing depth are effectively normalized, allowing biological variations to be more readily identified

- Intuitive interpretation: TPM values can be conceptualized as the number of transcripts that would be observed if exactly one million full-length transcripts were sequenced [31]

These characteristics make TPM particularly suitable for evaluating expression stability across different tissues, experimental conditions, or treatment groups—the fundamental requirement for identifying robust reference genes for qPCR studies [27].

Experimental Design and Data Acquisition

RNA Extraction and Library Preparation

The reliability of TPM data begins with proper experimental design and RNA handling. The following protocol outlines key considerations for generating RNA-seq data suitable for reference gene identification:

Materials and Reagents:

- TRIzol Reagent or equivalent RNA stabilization solution

- DNase I, RNase-free

- Magnetic bead-based RNA cleanup kits (e.g., RNAClean XP)

- RNA integrity assessment equipment (e.g., Bioanalyzer, TapeStation)

- Poly(A) selection or rRNA depletion kits

- RNA-seq library preparation kit (e.g., NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep)

- Size selection beads (e.g., AMPure XP)

- Quantification reagents (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay)

Procedure:

RNA Extraction:

- Homogenize tissue or cells in TRIzol reagent following manufacturer's protocol

- Precipitate RNA with isopropanol, wash with 75% ethanol, and resuspend in RNase-free water

- Treat with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination

- Purify using magnetic bead-based cleanup kits

- Assess RNA integrity using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation; accept only samples with RIN > 7.0 [29]

Library Preparation:

- Select mRNA using poly(A) selection for high-quality samples or perform rRNA depletion for degraded samples (e.g., from formalin-fixed tissues) [15]

- Fragment RNA to approximately 200-300 nucleotides using divalent cations under elevated temperature

- Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcriptase with random hexamers

- For strand-specific information, incorporate dUTP during second strand synthesis [15]

- Ligate adapters with unique dual indices to enable sample multiplexing

- Enrich adapter-ligated DNA by PCR amplification (typically 10-15 cycles)

- Perform size selection to remove adapter dimers and large fragments

- Quantify final libraries using fluorometric methods and validate size distribution

Sequencing Considerations

Appropriate sequencing parameters are essential for generating data suitable for reference gene identification:

- Sequencing Depth: Target 20-30 million reads per sample for standard gene-level expression analysis [15]

- Read Configuration: Use paired-end sequencing (2×75 bp or 2×150 bp) for improved mapping accuracy and transcriptome coverage

- Replicates: Include at least three biological replicates per condition to adequately assess expression stability [29]

- Batch Effects: Process all samples for a given experiment simultaneously to minimize technical variability, or randomize processing if batch effects are unavoidable [29]

Computational Analysis Workflow

Quality Control and Preprocessing

Raw sequencing data must undergo rigorous quality assessment before quantification. The following workflow ensures data integrity:

Figure 1: RNA-seq Data Processing Workflow

Quality Control Steps:

Raw Read QC:

- Assess sequence quality, GC content, adapter contamination, and overrepresented k-mers using FastQC [15]

- Trim adapters and low-quality bases using Trimmomatic or similar tools

- Remove reads with Phred quality score < 20

Alignment QC:

- Map reads to reference genome/transcriptome using aligners such as STAR or HISAT2

- Evaluate mapping statistics: >70% alignment rate expected for human samples [15]

- Check for 3' bias indicating RNA degradation

- Assess ribosomal RNA content: <5% for poly(A)-selected libraries

Quantification QC:

- Generate read counts per gene using featureCounts or HTSeq

- Verify correlation between replicates (Pearson R² > 0.9 expected)

- Check for unusual distribution of expression values

TPM Calculation Protocol

The following step-by-step protocol details TPM calculation from raw count data:

Input Requirements:

- Raw count matrix (genes × samples)

- Gene lengths in kilobases (from reference annotation)

Computational Steps:

Calculate RPK values:

Compute scaling factors:

Calculate TPM values:

Validate calculation:

Implementation Notes:

- Use robust programming environments (R/Bioconductor, Python) for reproducibility

- Document all parameters and software versions

- Perform sanity checks at each computational step

Expression Matrix Construction and Interpretation

Data Structure and Organization

A well-constructed TPM expression matrix forms the foundation for reference gene identification. The matrix should be structured as follows:

Table 2: TPM Expression Matrix Structure

| Gene_ID | Sample1TPM | Sample2TPM | Sample3TPM | ... | Gene_Symbol | Gene_Type | Chromosome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENSG00000139618 | 15.3 | 18.7 | 12.9 | ... | BRCA1 | protein_coding | chr17 |

| ENSG00000146648 | 245.6 | 251.3 | 260.1 | ... | EGFR | protein_coding | chr7 |

| ENSG00000075624 | 58.9 | 62.1 | 59.8 | ... | ACTB | protein_coding | chr7 |

| ENSG00000111640 | 12.5 | 11.9 | 13.2 | ... | GAPDH | protein_coding | chr12 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

Matrix Characteristics:

- Rows represent genes, columns represent samples

- Include stable gene identifiers (e.g., ENSEMBL IDs) and gene symbols

- Metadata should include gene biotypes to filter for appropriate reference candidates (typically protein-coding genes)

- Raw and normalized matrices should be archived separately

Stability Analysis for Reference Gene Selection

Identification of stable reference genes requires analysis of expression consistency across experimental conditions:

Analytical Steps:

Filtering:

- Remove genes with low expression (TPM < 1 in >50% of samples)

- Exclude genes with extreme expression (TPM > 10,000) which may dominate normalization

- Filter by gene type (typically focus on protein-coding genes)

Stability Assessment:

- Calculate coefficient of variation (CV = standard deviation/mean) for each gene across samples

- Genes with CV < 0.15 are considered moderately stable

- Genes with CV < 0.10 are considered highly stable

Ranking Candidates:

- Sort genes by increasing CV

- Select top 10-20 candidates for experimental validation

- Prioritize genes with moderate expression levels (TPM 10-1000) to ensure reliable qPCR detection

Table 3: Example Reference Gene Candidates Identified from TPM Data

| Gene Symbol | Mean TPM | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation | Stability Rank | Known Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YWHAZ | 85.3 | 6.2 | 0.073 | 1 | Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase |

| B2M | 124.6 | 10.1 | 0.081 | 2 | Beta-2-microglobulin |

| GAPDH | 215.8 | 19.3 | 0.089 | 3 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| ACTB | 185.6 | 18.9 | 0.102 | 4 | Actin beta |

| RPL13A | 76.4 | 8.5 | 0.111 | 5 | Ribosomal protein L13a |

Integration with qPCR Reference Gene Validation

Cross-Platform Validation Protocol

Candidate reference genes identified from TPM data must be experimentally validated using RT-qPCR:

Materials and Reagents:

- Reverse transcription kit (e.g., High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit)

- qPCR master mix (e.g., SYBR Green or TaqMan)

- Primers for candidate reference genes (designed to span exon-exon junctions)

- qPCR instrumentation (96-well or 384-well format)

- Normalization and analysis software

Procedure:

cDNA Synthesis:

- Use the same RNA samples that were subjected to RNA-seq analysis

- Perform reverse transcription with random hexamers

- Include no-reverse transcriptase controls for each sample

qPCR Amplification:

- Design primers with efficiency between 90-110%

- Perform triplicate technical replicates for each sample

- Include no-template controls for each primer pair

- Use standardized thermal cycling conditions

Stability Validation:

- Calculate Cq values for each candidate gene

- Analyze expression stability using algorithms such as geNorm, NormFinder, or BestKeeper [27]

- Select the most stable genes for normalization of target genes

Troubleshooting and Quality Assurance

Figure 2: Reference Gene Validation Workflow

Common Issues and Solutions:

- Discordance between RNA-seq and qPCR results: Often caused by differences in RNA quality, reverse transcription efficiency, or primer specificity. Verify RNA integrity and primer performance.

- High variability in candidate genes: Expand the candidate list or consider condition-specific reference genes [33].

- Platform-specific biases: Ensure RNA samples for both platforms are processed simultaneously from the same biological source.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for TPM Analysis and Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization | TRIzol, RNAlater | Preserves RNA integrity during sample collection | Compatible with downstream applications |

| RNA Extraction Kits | RNeasy Mini Kit, miRNeasy Mini Kit | High-quality RNA purification | Include DNase treatment step |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Bioanalyzer RNA Nano Kit, TapeStation RNA ScreenTape | Quantifies RNA integrity (RIN) | RIN > 7.0 recommended for RNA-seq |

| Library Preparation | NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit, Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep | Converts RNA to sequencing-ready libraries | Select poly(A) or rRNA depletion based on sample quality |

| Alignment Software | STAR, HISAT2, TopHat2 | Maps sequencing reads to reference genome | Balance between speed and sensitivity |

| Quantification Tools | featureCounts, HTSeq, Salmon | Generates raw counts from aligned reads | Consider alignment-free approaches for speed |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green, TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix | Detects and quantifies specific RNA targets | SYBR Green requires primer optimization |

| Reference Gene Panels | TaqMan Endogenous Control Assays | Pre-validated reference genes for human/mouse models | Useful as positive controls but may require validation in specific models |

Proper preparation and interpretation of TPM data and expression matrices are fundamental to the identification of reliable reference genes for RT-qPCR studies. The standardized protocols outlined in this application note provide a robust framework for researchers to transition from RNA-seq discovery to qPCR validation, ensuring that reference genes selected through computational analysis demonstrate stable expression in experimental validation. By adhering to these best practices for data generation, processing, and cross-platform validation, researchers can enhance the reliability of gene expression studies in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Accurate normalization is a critical prerequisite for reliable gene expression analysis using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The selection of inappropriate internal control genes can lead to significant biases and errors, resulting in the misinterpretation of experimental data [34]. The advancement of RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) technology provides a high-throughput and economical foundation for the systematic identification of novel, stably expressed candidate reference genes from transcriptomic datasets [35] [34].

This application note details the practical application of three essential statistical criteria—Standard Deviation (SD), Coefficient of Variation (CV), and Expression Level Cut-offs—for filtering candidate reference genes from RNA-Seq data. We provide a standardized protocol and a scientist's toolkit to empower researchers to implement these criteria effectively, thereby enhancing the rigor and reproducibility of gene expression studies.

Core Filtering Criteria: Definitions and Recommended Cut-offs

The following criteria are applied to gene expression values, typically Transcripts Per Million (TPM), across all samples in the RNA-Seq dataset. The table below summarizes the key parameters, their definitions, and the recommended threshold values used in published studies.

Table 1: Key Filtering Criteria for Selecting Candidate Reference Genes from RNA-Seq Data

| Criterion | Definition & Purpose | Recommended Cut-off | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Level | Ensures the gene is sufficiently expressed for reliable detection by qRT-PCR. | Average log2(TPM) > 5 [7] | Filters out low-abundance transcripts that may yield highly variable Cq values. |

| Standard Deviation (SD) | Measures the absolute dispersion of a gene's expression across all samples. | SD of log2(TPM) < 1 [7] | Identifies genes with minimal absolute fluctuation in expression. |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Measures the relative dispersion (SD/Mean), normalizing for expression level. | CV < 0.2 [7] | Identifies genes whose variation is low relative to their mean expression. |

These criteria are often applied sequentially to RNA-Seq data to generate a final list of high-quality candidate genes for subsequent experimental validation via qRT-PCR [7] [36].

Experimental Protocol: From RNA-Seq Data to Candidate Gene Selection

This protocol outlines the step-by-step procedure for identifying stably expressed reference genes using public or newly generated RNA-Seq data.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Obtain RNA-Seq Data: Download raw RNA-Seq data (e.g., FASTQ files) from public repositories like NCBI SRA or use in-house datasets. The dataset should encompass all the biological conditions and tissue types relevant to your planned qRT-PCR experiments [35] [34].

- Perform Quality Control: Use tools like FastQC to assess sequence quality. Trim adapters and low-quality bases with tools such as Trimmomatic or Cutadapt.

- Generate Gene Expression Matrix: Map quality-filtered reads to the appropriate reference genome using aligners like HISAT2 or STAR. Quantify transcript abundances as TPM values using software like StringTie or Salmon. TPM is recommended over FPKM/FPKM for cross-sample comparison [7].

Application of Filtering Criteria

- Filter 1: Ubiquitous Expression. Remove any gene with a TPM value of zero in any of the libraries analyzed (