How to Interpret a Gene Expression Heatmap: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a complete framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to accurately interpret gene expression heatmaps.

How to Interpret a Gene Expression Heatmap: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

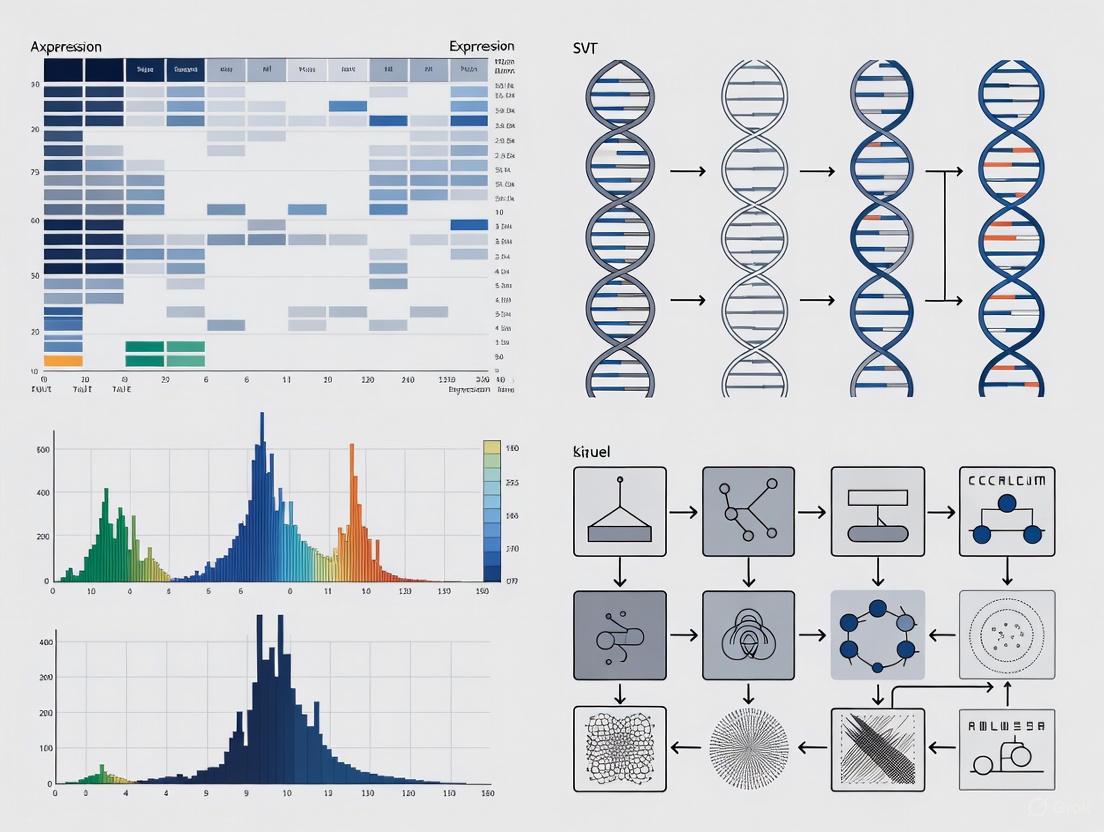

This article provides a complete framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to accurately interpret gene expression heatmaps. It covers foundational principles—from understanding color scales and matrix structure to deciphering clustered patterns—and progresses to advanced methodological applications for extracting biological meaning. The guide also addresses common interpretation challenges, offers optimization strategies for visualization, and explores the latest validation techniques and AI-powered predictive models, such as those benchmarking spatial gene expression from histology. By synthesizing these core intents, this resource empowers robust, data-driven conclusions in genomics and translational research.

Decoding the Grid: A Beginner's Guide to Heatmap Structure and Color

In the analysis of high-throughput genomic data, the heatmap has become an indispensable tool for visualizing complex gene expression patterns. This guide details the core anatomical components of a gene expression heatmap—rows, columns, and color-coded values—and provides a framework for their interpretation within biological research and drug development.

Core Components of a Gene Expression Heatmap

A heatmap is a two-dimensional visualization that represents a table of numerical data through colors [1]. In the context of gene expression, it provides an intuitive overview of the expression levels of numerous genes across multiple samples.

The table below summarizes the three fundamental components:

| Component | Description | Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Rows | Typically represent individual genes, transcripts, or biological pathways being analyzed [2] [1]. | Each row shows the expression profile of a single gene across all samples. |

| Columns | Represent the individual samples or experimental conditions [2] [1]. | Each column shows the expression of all measured genes in a single sample. |

| Color-Coded Values | Represent the level of gene expression, often as a normalized or relative value (e.g., Z-score, log2 fold-change) [3]. | Color intensity and hue indicate up-regulation, down-regulation, or neutral expression relative to a baseline. |

The Role of Color and Data Transformation

The color scale is the key to interpreting the numerical values in the heatmap. Commonly, a diverging color palette is used, where one color (e.g., red) represents upregulated genes, another color (e.g., blue) represents downregulated genes, and a neutral color (e.g., black or white) represents genes that do not change significantly [2] [1]. The intensity of the color corresponds to the magnitude of the change.

Because gene expression data can have a wide dynamic range, raw expression values are often transformed. A common practice is to apply a log transformation to the data to better visualize variation, especially among genes with lower expression levels [4]. Furthermore, data is frequently normalized across rows (genes) to calculate Z-scores, which show how many standard deviations a gene's expression in a sample is from its mean expression across all samples. This normalization, which is sample-centric, helps in identifying genes that are expressed unusually high or low in specific samples [3].

Experimental Protocol for a Differential Expression Heatmap

The following workflow outlines the key steps for creating a clustered heatmap from raw gene expression data, using a hypothetical case study of influenza-infected versus control cells [4].

Detailed Methodology

Data Wrangling and Tidy Formatting

- Objective: Structure the data for visualization. Raw data is often in a "wide" format where each gene is a column.

- Protocol: Use data manipulation tools (e.g., the

pivot_longerfunction in R'stidyrpackage) to transform the data into a "tidy" long format [4]. This creates three essential columns:Sample ID,Gene, andExpression Value. - Input Data: A table with columns:

subject,treatment,IFNA5,IFNA13, ... [4]. - Output Data: A table with columns:

subject,treatment,gene,expression.

Data Transformation

- Objective: Reduce the impact of extreme values and make the distribution of expression values more symmetric.

- Protocol: Apply a logarithmic transformation (e.g.,

log10(expression_value)) to create a new column of log-transformed expression values [4]. This ensures that the color scale is not dominated by a few highly expressed genes.

Data Normalization

- Objective: Standardize expression values to compare patterns across genes.

- Protocol: For each gene (row), calculate a Z-score. This is done by subtracting the mean expression of the gene across all samples from its expression in each sample and then dividing by the standard deviation. This row-centric normalization centers each gene's expression profile around zero, which is crucial for effective clustering [3].

Unsupervised Hierarchical Clustering

- Objective: Group genes and samples with similar expression profiles.

- Protocol: Apply clustering algorithms to both the rows (genes) and columns (samples) of the normalized data matrix. The algorithm calculates pairwise distances (e.g., Euclidean distance) between profiles and iteratively merges the most similar pairs, forming a dendrogram [2] [1]. The resulting dendrograms are used to reorder the rows and columns of the heatmap.

Visualization and Color Mapping

- Objective: Generate the final heatmap.

- Protocol: Use a visualization library (e.g.,

ggplot2withgeom_tilein R) to plot the data [4]. Thefacet_gridfunction can be used to annotate the samples by condition (e.g., control vs. influenza). The normalized expression values (Z-scores) are mapped to the color scale.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and computational tools required for generating and analyzing gene expression heatmaps.

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolate high-quality total RNA from cell or tissue samples (e.g., control vs. influenza-infected pDCs [4]). |

| Microarray or RNA-seq Platform | Profile the expression levels of thousands of genes simultaneously from the isolated RNA. |

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Perform data preprocessing, normalization, differential expression analysis, and visualization. |

| ggplot2 & tidyr R Packages | Specific libraries for data wrangling (tidyr) and creating publication-quality heatmaps (ggplot2) [4]. |

| Clustering Algorithm | An unsupervised method (e.g., hierarchical clustering) to group genes and samples by expression pattern similarity [2] [1]. |

| Promurit | Promurit | Rodenticide for Research | RUO |

| Clofedanol, (R)- | Clofedanol, (R)-, CAS:179764-48-8, MF:C17H20ClNO, MW:289.8 g/mol |

Visualization and Color Accessibility Guidelines

Effective heatmaps rely on clear color choices. The following guidelines ensure interpretability and accessibility.

Color Contrast and Palette

All diagrams must use the specified color palette. For any node containing text, the fontcolor must be explicitly set to contrast highly with the node's fillcolor. For example, use dark text (#202124) on light backgrounds (#F1F3F4) and light text (#FFFFFF) on dark backgrounds. Arrow and symbol colors must also contrast sufficiently with their background; avoid using #FFFFFF for arrows on a light grey (#F1F3F4) background.

Standardized Color Scales in Gene Expression

The table below describes common color conventions and their interpretations.

| Color Scheme | Typical Interpretation | Data Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Red-Blue Diverging | Red: Up-regulation or high expression. Blue: Down-regulation or low expression. | Z-score, Log Fold-Change [2] [1]. |

| Red-Yellow-Green | Red/Yellow: Increase in expression. Green: Decrease in expression. | Change from mean ΔCT value [3]. |

| Single Hue (e.g., Blue) | Light to dark intensity represents low to high expression values. | Absolute expression values (e.g., FPKM, TPM). |

Gene expression heatmaps are fundamental tools in biomedical research for visualizing complex transcriptomic data. The accurate interpretation of these heatmaps hinges on a rigorous understanding of the color scales used to represent statistical transformations of gene expression, primarily the Log2 Fold Change (Log2FC) and the Expression Z-Score. This technical guide delineates the computational foundations, methodological applications, and interpretative frameworks for these two pivotal metrics. Framed within the broader thesis of gene expression heatmap interpretation, this document provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge to decode biological narratives from colored matrices, thereby bridging the gap between raw data and biological insight.

In high-dimensional biology, visualization is not merely an aid but a critical component of data interpretation. Heatmaps allow for the intuitive representation of gene expression patterns across multiple samples or experimental conditions. The color scale applied transforms numerical data into an accessible visual format, where hues and intensities convey the magnitude and direction of change. Two of the most prevalent metrics underlying these scales are the Log2 Fold Change (Log2FC) and the Expression Z-Score. The former quantifies the magnitude of differential expression between distinct biological states (e.g., treated vs. control), while the latter standardizes expression relative to the mean across a dataset, highlighting relative up- and down-regulation. Misinterpretation of these scales can lead to flawed biological conclusions, underscoring the need for a deep technical understanding of their derivation and meaning.

The Log2 Fold Change (Log2FC): Quantifying Differential Expression

Conceptual and Mathematical Foundation

The Log2 Fold Change is a cornerstone metric in differential gene expression analysis. It measures the logarithm (base 2) of the ratio of expression values between two conditions.

Formula: The fundamental calculation for a given gene is: ( \text{Log2FC} = \log_2\left(\frac{\text{Mean Expression in Condition A}}{\text{Mean Expression in Condition B}}\right) )

Interpretation: A Log2FC of 1 indicates a twofold increase in expression in Condition A relative to Condition B. Conversely, a Log2FC of -1 indicates a twofold decrease (i.e., expression in Condition A is half that of Condition B). A value of 0 signifies no change.

Statistical Significance: The biological relevance of an observed fold change is validated through statistical testing. In RNA-Seq analysis, tools like DESeq2 and edgeR model the count data to test the null hypothesis that the Log2FC is equal to zero, providing an adjusted p-value (e.g., False Discovery Rate, FDR) to account for multiple testing [5] [6]. A gene is typically considered differentially expressed if it passes a threshold such as |Log2FC| > 1 (or 0.5) and an FDR < 0.05 [7].

Experimental Protocol for Log2FC Calculation

The following methodology outlines a standard pipeline for generating Log2FC values from raw RNA-Seq data, incorporating best practices for preprocessing and normalization [5].

- Quality Control (QC): Assess raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files) using tools like FastQC or multiQC to identify technical artifacts such as adapter contamination, low base quality, or unusual nucleotide composition [5].

- Read Trimming: Clean the data by removing adapter sequences and low-quality base calls using tools such as Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [5].

- Read Alignment: Map the cleaned reads to a reference genome or transcriptome using aligners like STAR or HISAT2. An alternative, faster approach is pseudo-alignment with Kallisto or Salmon to estimate transcript abundances directly [5].

- Post-Alignment QC: Filter aligned reads to remove poorly mapped or multi-mapped reads that could inflate counts, using tools like SAMtools or Picard [5].

- Read Quantification: Generate a raw count matrix, where each value represents the number of reads mapped to a specific gene in a specific sample. Tools like featureCounts or HTSeq-count are commonly used [5].

- Normalization and Differential Expression Analysis: Input the raw count matrix into a specialized statistical software package like DESeq2 or edgeR. These tools apply robust normalization methods (e.g., DESeq2's "median-of-ratios") to correct for differences in sequencing depth and library composition, and then perform statistical modeling to calculate Log2FC and its associated p-value for each gene [5] [6].

Table 1: Key Normalization Methods in RNA-Seq Analysis [5]

| Method | Sequencing Depth Correction | Gene Length Correction | Library Composition Correction | Suitable for DE Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Yes | No | No | No |

| FPKM/RPKM | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| TPM | Yes | Yes | Partial | No |

| median-of-ratios (DESeq2) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| TMM (edgeR) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

Figure 1: Computational workflow for generating Log2FC values from raw RNA-Seq data.

The Expression Z-Score: Standardizing for Cross-Gene Comparison

Conceptual and Mathematical Foundation

While Log2FC is ideal for comparing a gene's expression between two specific conditions, the Expression Z-Score is designed to standardize expression for a single gene across multiple samples (e.g., different tissues, patient samples, or time points). This allows researchers to easily identify which genes are relatively high or low in a specific sample within the context of the entire dataset.

Formula: The Z-Score for a gene's expression in a single sample is calculated as: ( Z = \frac{X - \mu}{\sigma} ) where ( X ) is the gene's expression value in the sample, ( \mu ) is the mean expression of that gene across all samples, and ( \sigma ) is the standard deviation of that gene's expression across all samples.

Interpretation: The Z-Scale represents the number of standard deviations a gene's expression in a particular sample is from its mean expression across the dataset.

- Z ≈ 0: Expression is close to the mean.

- Z > 0: Expression is above the mean.

- Z < 0: Expression is below the mean.

- Application in Heatmaps: Z-Score normalization is exceptionally useful for heatmaps because it puts all genes on a common, comparable scale. This prevents highly expressed genes from dominating the color map and allows subtle patterns of co-regulation to become visible.

Experimental Protocol for Z-Score Calculation

The input for Z-Score calculation is typically a normalized expression matrix (e.g., TPM, FPKM, or variance-stabilized counts from DESeq2).

- Input Normalized Matrix: Begin with a normalized expression matrix where rows represent genes and columns represent samples. Normalization methods like TPM (Transcripts Per Million) are often used for this purpose as they correct for sequencing depth and gene length, enabling cross-sample comparison [5].

- Gene-Wise Standardization: For each gene (row) in the matrix:

- Calculate the mean (( \mu )) expression of that gene across all samples.

- Calculate the standard deviation (( \sigma )) of that gene's expression across all samples.

- For each sample's expression value (X) for that gene, apply the Z-Score formula.

- Visualization: The resulting Z-Score matrix is used as the input for the heatmap. The color scale is typically a diverging palette (e.g., blue-white-red), where one color represents high positive Z-Scores, another represents low negative Z-Scores, and a neutral color represents Z-Scores near zero.

Comparative Analysis: Log2FC vs. Z-Score in Heatmaps

The choice between using Log2FC and Z-Score in a heatmap is dictated by the biological question.

Table 2: Comparative Application of Log2FC and Expression Z-Score in Heatmaps

| Feature | Log2FC Heatmap | Z-Score Heatmap |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Question | Which genes are differentially expressed between two defined conditions? | What are the relative expression levels of genes across many samples? |

| Data Input | A vector of Log2FC values for genes (one value per gene). | A normalized expression matrix (genes x samples). |

| Color Interpretation | Color indicates direction and magnitude of change between two states. | Color indicates whether a gene is expressed above/below its own average in a given sample. |

| Ideal Use Case | Direct comparison of two groups (e.g., treated vs. control, tumor vs. normal). | Identifying sample clusters, gene co-expression patterns, and subtypes within a heterogeneous dataset (e.g., cancer subtypes). |

| Information Conveyed | Differential expression. | Relative expression and patterning. |

Figure 2: Decision workflow for selecting between Log2FC and Z-Score visualization based on the research objective.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The analysis and visualization of gene expression data rely on a robust ecosystem of computational tools and databases.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Gene Expression Heatmap Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in this Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 [5] [6] | R/Bioconductor Package | Differential expression analysis | Statistical testing for calculating Log2FC and its significance from raw count data. |

| edgeR [5] | R/Bioconductor Package | Differential expression analysis | An alternative to DESeq2 for identifying differentially expressed genes. |

| Salmon/Kallisto [5] | Computational Tool | Pseudo-alignment & quantification | Fast and efficient estimation of transcript abundances from RNA-Seq reads. |

| FastQC [5] | Computational Tool | Quality Control | Generates initial QC report for raw sequencing data. |

| HTSeq-count/featureCounts [5] | Computational Tool | Read Quantification | Generates the raw count matrix from aligned reads. |

| GseaVis [8] | R Package | Visualization | Creates enhanced, publication-ready visualizations for gene set enrichment analysis. |

| TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) [7] | Database | Genomic Data Repository | Source of publicly available RNA-Seq and clinical data for analysis (e.g., NSCLC study). |

| TISCH2 [7] | Database | Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data | Resource for exploring gene expression in the tumor microenvironment at single-cell resolution. |

| (-)-Erinacine E | (-)-Erinacine E | Neurotrophic Research Compound | (-)-Erinacine E, a potent NGF inducer from Hericium erinaceus. For neuroscience research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-Methyleicosane | 2-Methyleicosane | High Purity | For Research Use | High-purity 2-Methyleicosane for research. Used in lipid studies & material science. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The principles of Log2FC and Z-Score interpretation extend beyond bulk RNA-Seq. In single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), Z-Score heatmaps are instrumental in visualizing the defining marker genes for distinct cell populations identified through clustering [7]. Furthermore, tools like GseaVis are revolutionizing downstream visualization by enabling the creation of highly customizable, publication-quality figures from gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), which itself relies on ranked lists of genes often based on Log2FC [8].

Accessibility in data visualization is also a critical consideration. Adhering to Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), such as ensuring a minimum 3:1 contrast ratio for graphical elements, is essential for creating inclusive scientific communications that are perceivable by all colleagues, including those with color vision deficiencies [9] [10] [11]. This can be achieved by combining color with secondary visual cues like patterns or shapes.

Gene expression heatmaps are indispensable tools in modern genomic research, enabling scientists to visualize complex patterns of upregulation and downregulation across thousands of genes in a single, intuitive image. This technical guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for interpreting these visualizations, focusing on the translation of colored grids into biologically meaningful insights. By integrating fundamental principles, advanced clustering methodologies, and practical interpretation protocols, this whitepaper serves as an essential resource for extracting global expression patterns critical for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets.

A heatmap is a two-dimensional visualization that uses color to represent numerical values in a matrix format [12]. In the context of genomic studies, heatmaps provide a powerful method for displaying gene expression data across multiple samples, transforming complex numerical datasets into accessible visual patterns [1]. Each row typically represents a gene, each column represents a sample or experimental condition, and the color intensity of each tile represents the expression level or differential expression value of that gene under those specific conditions [1] [13].

The fundamental value of heatmaps lies in their ability to facilitate instant pattern recognition through pre-attentive processing, whereby our brains detect visual differences before conscious analysis occurs [14]. This visual approach allows researchers to comprehend explosive amounts of high-throughput data that would otherwise remain impenetrable in spreadsheet format [13]. By encoding expression values as colors, heatmaps reduce cognitive load while simultaneously highlighting critical relationships between gene expression profiles and experimental conditions [14].

Fundamental Principles and Color Schemes

Data Representation in Heatmaps

In differential gene expression analysis, heatmaps typically display normalized expression values, most commonly log2 fold change (log2FC) data, which indicates how much each gene is upregulated or downregulated in experimental samples compared to control samples [1]. Rather than showing absolute expression values, these visualizations represent changes in expression, with color gradients corresponding to the magnitude and direction of change [1].

The underlying data structure for a heatmap can be organized in two primary formats. The first is a complete matrix where the first column identifies genes (rows), and subsequent column headers represent samples or conditions, with intersecting cells containing expression values [12]. The second is a three-column format where each row specifies a gene-sample-value combination, which computational tools then transform into the matrix structure required for visualization [12].

Color Palette Selection

The choice of color palette is critical for accurate interpretation of gene expression heatmaps. Two primary types of color schemes are used, each serving distinct analytical purposes:

Diverging Color Palettes: Essential for visualizing differential expression data, these palettes use contrasting colors to represent opposing expression directions, typically with a neutral color (often white or light gray) representing no change or baseline expression [15]. For example, intensities of red may indicate upregulated genes (positive log2FC values), while intensities of blue may represent downregulated genes (negative log2FC values) [1]. The intensity of the color typically corresponds to the magnitude of change, with more intense coloration indicating greater differential expression [1].

Sequential Color Palettes: Employed for displaying absolute expression values rather than differential expression, these palettes use gradients of a single hue moving from lighter to darker shades, representing continuously increasing expression levels [15].

Table 1: Common Color Schemes in Gene Expression Heatmaps

| Palette Type | Data Representation | Color Progression | Application in Genomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diverging | Differential Expression (Fold Changes) | Red → White → Blue | Comparing experimental vs. control conditions |

| Sequential Single-Hue | Absolute Expression Levels | Light Blue → Dark Blue | Displaying expression intensity across samples |

| Sequential Multi-Hue | Absolute Expression Levels | Yellow → Orange → Red | Visualizing expression gradients |

For accessibility, color selections must provide sufficient contrast, with WCAG guidelines recommending a minimum contrast ratio of 3:1 for graphical objects [9]. The specific Google palette colors specified for this document (#4285F4, #EA4335, #FBBC05, #34A853, #FFFFFF, #F1F3F4, #202124, #5F6368) must be combined thoughtfully to ensure interpretability for all users, including those with color vision deficiencies [14].

Clustered Heatmaps: Revealing Patterns Through Reordering

The Clustering Methodology

Clustered heatmaps represent an advanced variant that combines standard heatmap visualization with clustering algorithms to group similar rows (genes) and columns (samples) together based on the similarity of their expression patterns [12] [1]. This reordering is fundamental to revealing biological patterns that would otherwise remain hidden in an arbitrarily ordered matrix [13].

Hierarchical clustering, the most common algorithm applied in genomic heatmaps, calculates pairwise similarity between all genes and all samples, then groups entities with similar expression profiles [1] [13]. The results of this clustering are typically visualized as dendrograms displayed alongside the rows and columns of the heatmap, illustrating the hierarchical relationships between genes and samples [1]. This approach delivers two vital pieces of information: it reveals patterns among rows and columns, and it exposes genes with coordinated expression profiles across sample groups [13].

Biological Significance of Clustering

The power of clustered heatmaps lies in their ability to identify biologically meaningful relationships:

Gene Clustering: Genes that cluster together often participate in related biological processes, are co-regulated, or function in the same pathway [1]. For example, a cluster of genes consistently upregulated in cancer samples might represent a signature of tumor progression or potential drug targets.

Sample Clustering: Samples that cluster together based on global gene expression patterns typically share biological characteristics [1]. In a cancer study, tumor samples might cluster separately from healthy controls, or different molecular subtypes might form distinct clusters, revealing previously unrecognized disease classifications.

Unexpected clustering results can be particularly insightful, potentially identifying novel disease subtypes or revealing unexpected relationships between seemingly disparate conditions [1]. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from raw data to biological insight:

Diagram: Heatmap Generation Workflow

Step-by-Step Interpretation Protocol

Systematic Approach to Heatmap Analysis

Interpreting a gene expression heatmap requires a structured methodology to extract meaningful biological insights:

Axis Inspection: Begin by examining the x-axis (typically samples/conditions) and y-axis (typically genes) labels to understand the experimental design. Note the sample groupings and any experimental conditions or time points [1].

Color Scale Reference: Consult the legend to understand the color-value relationship. Determine the range of expression values and whether the colors represent log2 fold changes, normalized expression values, or other metrics. Note that log2FC > 0 typically indicates upregulation, while log2FC < 0 indicates downregulation [1].

Global Pattern Assessment: Step back and observe the overall distribution of colors. Identify large blocks of similar colors that might indicate coordinated biological programs [14].

Cluster Analysis: Examine the dendrograms to identify major clusters of genes and samples. Note which sample groups cluster together and which genes show similar expression patterns across conditions [1].

Focused Pattern Identification: Look for specific patterns of interest, such as genes upregulated in one condition but downregulated in another, or genes that show consistent expression across all samples [1].

Outlier Detection: Identify any unusual patterns, such as individual samples that don't cluster with their expected group or genes with unexpected expression profiles, which might represent technical artifacts or biologically significant anomalies [14].

Interpretation in Experimental Context

The biological interpretation of patterns must always consider the experimental context:

Disease vs. Healthy Comparisons: In case-control studies, genes consistently upregulated in disease samples represent potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets, while downregulated genes might indicate impaired biological functions [1].

Time-Series Experiments: In longitudinal studies, genes showing progressive changes in expression over time may represent drivers of disease progression or treatment response markers [15].

Treatment Response Studies: Genes that change expression following treatment may identify mechanisms of drug action or resistance pathways [13].

Table 2: Heatmap Patterns and Their Potential Biological Interpretations

| Visual Pattern | Description | Potential Biological Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Vertical Color Blocks | Distinct color regions across sample columns | Sample subgroups with different expression profiles (e.g., disease subtypes) |

| Horizontal Color Strips | Distinct color regions across gene rows | Co-regulated gene sets or functional pathways |

| Checked Distribution | Mixed colors without clear blocks | Heterogeneous expression with limited coordination |

| Solid Color Rows | Consistent color across all samples for a gene | Housekeeping genes or non-responsive genes |

| Gradual Color Transitions | Smooth color changes across conditions | Progressive expression changes (e.g., time courses) |

Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Expression Analysis

The generation of reliable heatmap data requires specific laboratory reagents and bioinformatics tools. The following table outlines essential materials and their functions in gene expression analysis workflows:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Gene Expression Analysis

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Analysis Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Qiagen RNeasy, TRIzol Reagent | Isolation of high-quality RNA from tissue/cell samples |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription | Conversion of RNA to stable cDNA for analysis |

| qPCR Reagents | SYBR Green, TaqMan Probes | Target-specific gene expression quantification |

| Microarray Platforms | Affymetrix GeneChip, Illumina BeadChip | Genome-wide expression profiling |

| RNA-Seq Library Prep | Illumina TruSeq, NEBNext Ultra | Preparation of sequencing libraries for transcriptome analysis |

| Clustering & Visualization Tools | ClustVis, HeatmapGenerator | Data transformation, clustering, and heatmap generation [13] |

| Statistical Analysis Software | R/Bioconductor, Python libraries | Normalization, differential expression analysis [13] |

Technical Considerations and Best Practices

Data Preprocessing and Normalization

The reliability of any heatmap visualization depends entirely on appropriate data preprocessing:

Normalization Methods: Techniques such as TPM (Transcripts Per Million) for RNA-seq or RMA (Robust Multi-array Average) for microarrays remove technical variations to enable valid biological comparisons [13].

Data Transformation: Log transformation of expression values improves visualization by reducing the influence of extreme values and making the distribution more symmetrical [1].

Quality Control: Implementation of rigorous quality control metrics, including sample correlation analysis and outlier detection, ensures that clustering patterns reflect biology rather than technical artifacts.

Visualization Optimization

Creating interpretable heatmaps requires careful attention to design principles:

Color Scale Selection: Ensure the color scale appropriately represents the data distribution. For divergent data with a meaningful zero point (like fold changes), use diverging color palettes [15].

Adequate Labeling: Include clear, descriptive labels for rows, columns, and color scales to facilitate interpretation [12]. When displaying hundreds of genes, consider interactive visualization that allows users to zoom and identify specific genes.

Accessibility Compliance: Follow WCAG 2.2 guidelines for non-text contrast, ensuring a minimum 3:1 contrast ratio for graphical elements [9] [16]. Implement screen reader compatibility through WAI-ARIA attributes such as role="img" and appropriate aria-labels for heatmap elements [16].

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points in creating an effective gene expression heatmap:

Diagram: Heatmap Design Decision Tree

Gene expression heatmaps serve as powerful tools for transforming complex genomic data into visually interpretable patterns of upregulation and downregulation. When constructed with appropriate color schemes, clustering methods, and interpretation protocols, these visualizations enable researchers to identify global expression patterns, discover novel biological relationships, and generate testable hypotheses. As genomic technologies continue to evolve, producing increasingly large and complex datasets, the principles outlined in this technical guide will remain fundamental for extracting meaningful biological insights from gene expression heatmaps.

Clustered heat maps with dendrograms serve as a cornerstone for the analysis and interpretation of high-dimensional biological data, particularly in genomics and drug development. These visualizations integrate heat mapping with hierarchical clustering to reveal intrinsic patterns—grouping genes with co-regulated expression and samples with similar molecular profiles—that are not immediately apparent through other analytical methods. This technical guide details the construction, interpretation, and application of dendrograms within gene expression studies, providing researchers with explicit protocols and standards to transform complex data matrices into biologically meaningful insights for advancing therapeutic discovery [17] [18].

In the analysis of gene expression data, a dendrogram, or tree diagram, is a network structure that visualizes the outcome of a hierarchical clustering algorithm. It represents the relationships of similarity (or dissimilarity) among data points, such as genes or samples. When combined with a heat map—a graphical representation of data where individual values in a matrix are represented as colors—it forms a clustered heat map. This powerful combination allows researchers to simultaneously visualize the raw data (e.g., gene expression levels) and the organized cluster structure derived from that data [17] [18].

The core premise is that genes with similar expression patterns across different samples may be co-regulated or involved in related biological pathways. Similarly, samples that cluster together based on their gene expression profiles may share biological characteristics, such as being from the same disease subtype or responding similarly to a treatment [17] [19]. Thus, the dendrogram provides a visual summary of the relationships within the data, turning a table of thousands of gene expression values into an intelligible map that can guide further research and hypothesis generation [18].

Core Methodological Foundations

The construction of a robust clustered heat map involves a series of critical decisions that directly impact the biological conclusions drawn. The process hinges on three key parameters: the choice of distance metric, the selection of a clustering algorithm, and data pre-processing.

Distance Metrics

The first step in clustering is to quantify the similarity between each pair of objects (e.g., genes or samples). This is achieved by calculating a distance matrix. Common metrics include [17] [20]:

- Euclidean Distance: The straight-line distance between two points in multi-dimensional space. It is sensitive to magnitude and is a general-purpose metric.

- Pearson Correlation: Measures the linear correlation between two sets of data. It is often used in gene expression analysis to find genes with similar expression patterns (i.e., similar "shapes" of their profiles across samples), regardless of their absolute expression levels.

The choice of distance metric can significantly influence the clustering results. Consider two genes, Gene A and Gene B, with expression values across three samples (S1, S2, S3):

Gene A: [10, 20, 30]

Gene B: [20, 30, 40].

The Euclidean distance is calculated as:

√((10-20)² + (20-30)² + (30-40)²) = √(100 + 100 + 100) ≈ 17.32.

In contrast, the Pearson correlation is +1, indicating a perfect positive linear relationship. The former is influenced by the magnitude, while the latter focuses on the trend.

Clustering Algorithms

Once distances are calculated, a clustering algorithm is applied. Hierarchical clustering is most common and can be either agglomerative (bottom-up) or divisive (top-down). Agglomerative clustering, the standard approach, starts with each object as its own cluster and iteratively merges the closest clusters until one remains [20].

The method for determining which clusters to merge is defined by the linkage criterion:

- Complete Linkage: The distance between two clusters is defined as the maximum distance between any two points in the different clusters. This method tends to produce compact, tightly bounded clusters [20].

- Single Linkage: The distance between two clusters is defined as the minimum distance between any two points in the different clusters. This method can produce long, "chain-like" clusters and is sensitive to noise [20].

- Average Linkage: The distance between two clusters is defined as the average distance between every pair of points in the two clusters. This offers a compromise between complete and single linkage [20].

- Ward's Method: This method minimizes the total within-cluster variance. At each step, it merges the pair of clusters that leads to the minimum increase in the overall sum of squared differences from the cluster centroids. It is a very common default method as it tends to create clusters of relatively uniform size and is highly sensitive to data scaling [20].

Data Scaling and Normalization

Gene expression data often contains variables (genes) with different units or dynamic ranges. A high-abundance gene could dominate the distance calculation, obscuring the pattern of a low-abundance but biologically critical gene. Therefore, data scaling is a critical step prior to clustering [17].

The most common method is to compute the z-score for each gene across samples. This converts the expression of each gene to a new value representing the number of standard deviations it is from the mean of that gene. This ensures all genes have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, putting them on a comparable scale and preventing high-expression genes from disproportionately influencing the cluster analysis [17] [21].

z-score = (individual value - mean) / (standard deviation) [17]

Table 1: Comparison of Common Distance and Linkage Methods

| Method Type | Name | Mathematical Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance Metric | Euclidean | Square root of the sum of squared differences | Intuitive; measures "as the crow flies" distance | Sensitive to absolute expression levels and outliers |

| Distance Metric | Pearson Correlation | Covariance of two variables divided by product of their standard deviations | Finds patterns with similar shapes; insensitive to magnitude | Only captures linear relationships |

| Linkage Criterion | Complete Linkage | Uses the maximum distance between clusters | Produces compact, spherical clusters | Can break large clusters; sensitive to outliers |

| Linkage Criterion | Ward's Method | Minimizes within-cluster sum of squares | Creates clusters of similar size; high sensitivity | Biased towards globular clusters; requires scaled data |

Experimental Protocol for Hierarchical Clustering of Gene Expression Data

The following protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for performing hierarchical clustering and generating a clustered heat map from a normalized gene expression matrix, using R and the pheatmap package as an example [17].

Software and Data Preparation

Research Reagent Solutions (Computational Tools):

- R Statistical Environment: The core platform for statistical computing and graphics [17].

- pheatmap Package: A versatile R package specifically designed for drawing publication-quality clustered heatmaps with a built-in scaling function and highly customizable features [17].

- tidyverse Package: A collection of R packages (e.g., dplyr, tidyr) for efficient data wrangling and manipulation [17].

- Normalized Gene Expression Matrix: A data matrix where rows represent genes, columns represent samples, and values are normalized expression measures (e.g., Log2(CPM), TPM). The example data used below represents the normalized (log2 counts per million) of count values from the top 20 differentially expressed genes from an airway smooth muscle cell study (Himes et al., 2014) [17].

Step-by-Step Workflow

Load Required Libraries and Import Data:

Data Scaling (Z-score Standardization): While

pheatmapcan perform scaling internally, it is critical to specify the direction. Typically, scaling is applied across rows (genes) to compare expression patterns across samples. This is done within thepheatmapfunction using thescale="row"argument [17]. Manual alternative:Generate the Clustered Heat Map: The basic command generates a heatmap with dendrograms for both rows and columns using default parameters (Euclidean distance and Complete linkage).

The resulting plot shows samples clustered along the top horizontal axis and genes clustered along the right vertical axis. Each tile's color corresponds to the scaled expression level of a gene in a specific sample.

Customization and Interpretation: To interpret the dendrogram, identify the longest vertical branches (or the highest horizontal connection bars); these indicate a large distance between clusters, meaning the separated groups are highly dissimilar. Conversely, short branches and early merges indicate high similarity. The order of leaves (genes/samples) along the axis is determined by the clustering algorithm to place similar objects next to each other [17] [20].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points involved in the construction of a clustered heatmap.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for constructing a clustered heatmap, showing key decision points for distance metrics and linkage methods.

Advanced Applications in Drug Development and Research

Clustered heatmaps are not merely descriptive tools; they are actively used in preclinical and clinical research to drive decision-making.

Patient Stratification and Biomarker Discovery: In oncology, clustered heatmaps of gene expression data from large consortia like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) are used to classify patients into molecular subtypes. These subtypes can have distinct prognoses and responses to therapy, enabling more personalized treatment strategies [18]. For example, a heatmap might reveal a cluster of patients with high expression of an oncogene, potentially identifying a subgroup that would benefit from a targeted inhibitor.

Drug Safety and Efficacy Screening: A 2021 study used a high-dose drug heat map model to test 70 drug compounds on patient-derived glioblastoma multi-spheroids. The heat map visualization allowed researchers to quickly compare the efficacy (cell death in cancer spheroids) and toxicity (effect on normal astrocyte spheroids) profiles of all compounds simultaneously. This primary screening identified four compounds (Dacomitinib, Cediranib, LY2835219, BGJ398) that were efficacious against the cancer cells without showing toxicity to normal cells, highlighting their potential as promising drug candidates [22].

Exploring Gene Function and Pathways: By clustering genes based on their expression profiles across various experimental conditions (e.g., different drug treatments, time points, or genetic perturbations), researchers can identify groups of co-expressed genes. This often implies co-regulation or involvement in shared biological pathways. Such analyses can infer the function of uncharacterized genes based on their clustering with known genes and generate hypotheses about pathway activity in different biological states [18] [19].

Essential Tools and Visualization Standards

The field offers a variety of software tools for generating clustered heatmaps, from static publication figures to interactive exploratory applications.

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Generating Clustered Heat Maps

| Tool Name | Language/Platform | Key Features | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| pheatmap | R | Highly customizable, publication-quality static plots, built-in scaling [17]. | Standard static visualization for reports and publications. |

| ComplexHeatmap | R (Bioconductor) | Extremely versatile for complex annotations, supports multiple heatmaps in a single plot [18]. | Advanced static heatmaps with rich sample annotations. |

| seaborn.clustermap | Python | Generates clustered heatmaps with dendrograms integrated into the Matplotlib/Python ecosystem [18]. | Clustered heatmaps within a Python-based data analysis workflow. |

| Clustergrammer/NG-CHM | Web-based, R, Python | Produces interactive heatmaps with zooming, hovering, and linking to external databases [18] [23] [21]. | Exploratory data analysis of large, complex datasets. |

| heatmaply | R | Generates interactive D3-based heatmaps from R that can be embedded in web pages [17]. | Creating shareable, interactive visualizations for web reporting. |

Effective visualization requires careful consideration beyond the algorithm. The following diagram outlines the key components of a well-annotated clustered heatmap and their interpretive value.

Figure 2: Key components of a fully annotated clustered heatmap, illustrating the integration of dendrograms, data matrix, and metadata.

Dendrograms are far more than just decorative elements on a heat map; they are the visual output of a rigorous statistical process that organizes high-dimensional data based on similarity. A strong interpretation of a gene expression heatmap research project requires a foundational understanding of how these dendrograms are built—from the critical choices of distance metric and linkage method to the essential step of data scaling. By following standardized protocols and leveraging the powerful tools available, researchers and drug developers can reliably uncover patterns of co-expression, identify disease subtypes, and pinpoint potential therapeutic targets, thereby extracting profound biological meaning from complex molecular datasets.

From Visualization to Insight: Extracting Biological Meaning from Your Data

A Step-by-Step Guide to Reading a Clustered Heatmap

Clustered heatmaps are an indispensable tool in modern biological research, providing a powerful visual representation of complex datasets such as gene expression patterns. This technical guide details the systematic interpretation of clustered heatmaps within the context of genomic research and drug development. We present a comprehensive framework for analyzing the colored data matrix, dendrogram structures, and integrated patterns that reveal functional relationships in transcriptomic data. The guide incorporates standardized experimental protocols for heatmap-based analysis and specifies essential research reagents to ensure methodological reproducibility. Our findings demonstrate that proficient heatmap interpretation enables researchers to rapidly identify co-expressed gene modules, discern sample subtypes, and formulate mechanistic hypotheses for therapeutic intervention.

A clustered heatmap is a two-dimensional visualization that represents a data matrix through a color scale and organizes its rows and columns via hierarchical clustering, revealing underlying patterns and relationships [24]. In gene expression research, this technique transforms numerical data matrices—where rows typically represent genes and columns represent experimental samples or conditions—into an intuitive visual format where color intensity corresponds to expression levels [12]. The primary analytical power of a clustered heatmap stems from its dual clustering functionality; it simultaneously groups genes with similar expression patterns across samples and samples with similar expression profiles across genes [15]. This bidirectional clustering is represented by dendrograms (tree structures) displayed on the left and top margins of the color matrix, which visually encode the hierarchical relationships within the data [24].

The fundamental components of a clustered heatmap include:

- Color Matrix: The grid of colored squares where each color represents a normalized value (e.g., gene expression level).

- Dendrograms: Tree structures showing the hierarchical clustering of rows and columns.

- Color Legend: The scale that maps colors to numerical values.

- Row/Column Labels: Identifiers for genes and samples.

For gene expression studies, clustered heatmaps are particularly valuable for identifying co-regulated genes, classifying disease subtypes based on transcriptional profiles, and detecting expression patterns in response to therapeutic compounds [12]. The visual nature of this representation allows researchers to comprehend complex datasets that would be difficult to interpret through numerical analysis alone, facilitating the discovery of biological insights and the generation of testable hypotheses.

Fundamental Components and Their Interpretation

The Color Matrix: Decoding Expression Values

The core of a clustered heatmap is a grid of colored cells where color represents the magnitude of the measured variable. In gene expression heatmaps, the color scale typically ranges from dark blue (representing low expression) to dark red (representing high expression), with intermediate values shown in gradient colors [24]. Accurate interpretation requires careful reference to the color legend, which precisely maps colors to numerical values. For example, in a z-score normalized expression heatmap, white might represent average expression, while increasing intensities of red and blue represent expression levels above and below the mean, respectively [15].

When analyzing the color matrix, researchers should:

- Identify patches of similar color that form visual clusters

- Note extreme values (very red or very blue cells) that may represent biologically significant overexpression or underexpression

- Observe global patterns that span multiple rows and columns

- Compare the color patterns with experimental conditions (e.g., treatment vs. control samples)

The interpretation must account for the data normalization method applied prior to visualization. For instance, row-normalized data (genes) highlights patterns across samples, while column-normalized data emphasizes patterns across genes.

Dendrograms: Understanding Hierarchical Clustering

Dendrograms diagram the hierarchical clustering relationships between rows (genes) and columns (samples) [24]. The branch lengths in a dendrogram represent the degree of similarity between elements—shorter branches indicate higher similarity, while longer branches indicate greater dissimilarity [12]. The clustering algorithm (e.g., Euclidean distance with complete linkage) determines how these relationships are calculated and can significantly impact the resulting visualization.

To interpret dendrograms effectively:

- Observe the primary bifurcations, which separate the data into major clusters

- Note the order of leaves (end points), which determines the arrangement of rows and columns in the color matrix

- Identify closely paired elements that share high similarity

- Recognize that the dendrogram structure can suggest natural groupings within the data

In genomic applications, dendrograms on the sample axis may reveal previously unrecognized disease subtypes, while gene-side dendrograms can identify functionally related gene sets or regulatory modules.

Integrated Pattern Recognition

The most significant insights emerge from synthesizing information from both the color matrix and dendrograms. Coherent blocks of color that align with dendrogram clusters often represent biologically meaningful patterns. For example, a cluster of genes showing elevated expression specifically in tumor samples but not in normal controls may represent a cancer-specific expression signature.

Key analytical approaches include:

- Identifying gene clusters that show consistent expression patterns across sample groups

- Recognizing sample clusters that share similar global expression profiles

- Noting exceptions to the overall pattern, which may represent technical artifacts or biologically significant outliers

- Correlating identified clusters with known biological functions or experimental conditions

Table 1: Common Color Schemes in Gene Expression Heatmaps

| Color Scheme Type | Typical Application | Example Colors | Data Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential Single-Hue | Expression levels (unidirectional) | Light to dark blue | Non-negative values (e.g., raw counts) |

| Diverging | Z-score normalized expression | Blue-white-red | Values centered around mean (e.g., fold-change) |

| Qualitative | Categorical assignments | Distinct colors (red, green, blue, yellow) | Non-ordinal groups (e.g., sample types) |

Step-by-Step Analytical Protocol

Pre-analysis Data Assessment

Before interpreting the heatmap visualization, verify the experimental context and data processing steps:

- Confirm Data Provenance: Note the source of the expression data (e.g., RNA-seq, microarray) and the specific experimental conditions represented in the columns.

- Identify Normalization Method: Determine whether and how the data were normalized (e.g., z-score by row, quantile normalization) as this dramatically affects color patterns.

- Review Sample Annotation: Check the relationship between column labels and experimental conditions, noting any batch effects or confounding variables.

- Verify Gene Annotation: Ensure row labels use standardized gene nomenclature and consider the biological functions of represented genes.

This preliminary assessment ensures that observed patterns are interpreted within the appropriate technical and biological context.

Systematic Visualization Analysis

Follow this structured approach to extract maximum information from the heatmap:

Step 1: Global Pattern Survey Begin with a broad overview without focusing on specific elements. Note the overall distribution of colors, the presence of prominent vertical and horizontal stripes, and any large-scale patterns that immediately capture attention. This initial survey provides intuition about the dominant trends in the data.

Step 2: Dendrogram Interpretation Analyze the sample dendrogram (top or bottom) to identify major sample clusters. Then examine the gene dendrogram (left or right) to identify major gene clusters. Note the hierarchy of branching and approximate similarity distances between clusters.

Step 3: Correlate Clusters with Metadata Compare the cluster assignments from the dendrograms with known sample metadata (e.g., disease status, treatment group, patient demographics). Look for concordance between computational clustering and experimental design.

Step 4: Identify Co-expression Modules Locate regions in the heatmap where genes (rows) show similar expression patterns across a set of samples (columns). These co-expression modules often represent functionally related genes or coregulated genetic programs.

Step 5: Document Notable Features Record observations about specific features including:

- Extreme expression values (very red or blue cells)

- Samples that cluster unexpectedly

- Genes that appear as outliers to their assigned cluster

- Clear boundaries between different expression patterns

Step 6: Generate Biological Hypotheses Formulate testable hypotheses based on the observed patterns. For example, if a cluster of immune-related genes shows elevated expression in a subset of cancer samples, this might suggest differential immune infiltration.

Experimental Validation Framework

After identifying patterns of interest, design experiments to confirm their biological significance:

- Technical Validation: Confirm expression patterns for key genes using an independent method (e.g., qRT-PCR for RNA-seq data).

- Functional Validation: Perform perturbation experiments (e.g., siRNA knockdown) for genes in clusters of interest and assess phenotypic consequences.

- Clinical Correlation: For patient-derived data, validate associations between expression clusters and clinical outcomes in independent cohorts.

- Mechanistic Studies: Investigate regulatory mechanisms underlying co-expression patterns (e.g., common transcription factor binding sites).

The following diagram illustrates the complete analytical workflow for clustered heatmap interpretation:

Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomic Analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Heatmap-Based Gene Expression Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality RNA from biological samples | Essential for minimizing degradation; quality impacts clustering patterns |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesis of cDNA from RNA templates | Choice affects representation of low-abundance transcripts |

| Sequencing Library Prep Kit | Preparation of RNA-seq libraries | Impacts coverage uniformity and detection dynamic range |

| Microarray Platform | Alternative to sequencing for expression profiling | Different platforms require specific normalization approaches |

| Clustering Software | Performing hierarchical clustering and visualization | Options include R/Bioconductor, Cluster 3.0, Morpheus |

| Normalization Algorithm | Standardization of expression values | Critical for cross-sample comparisons; choice affects heatmap patterns |

| Quality Control Metrics | Assessment of data quality pre-analysis | Identifies problematic samples that may distort clustering |

Case Study: Drug Response Signature Identification

To illustrate the practical application of clustered heatmap analysis in pharmaceutical development, consider this representative experimental protocol:

Objective: Identify gene expression signatures associated with differential response to a novel kinase inhibitor in cancer cell lines.

Experimental Design:

- Treat 50 cancer cell lines with the investigational compound at IC50 concentrations for 24 hours

- Include DMSO-treated controls for each cell line

- Profile transcriptomes using RNA sequencing

- Process data through standardized bioinformatic pipeline

Heatmap Analysis:

- Filter to 5,000 most variable genes across all samples

- Apply z-score normalization by gene (row)

- Perform hierarchical clustering using Euclidean distance and complete linkage

- Visualize as clustered heatmap with sample annotations

Key Findings:

- Unsupervised clustering separated cell lines into two major groups (A and B) without reference to drug response data

- Group A showed coordinated upregulation of apoptosis-related genes and downregulation of cell cycle genes

- Group B exhibited minimal expression changes in these pathways

- When overlayed with response data, Group A corresponded to sensitive cell lines (mean viability reduction: 75%) while Group B contained resistant lines (mean viability reduction: 20%)

Validation:

- The expression signature was validated in an independent set of 30 cell lines

- siRNA knockdown of hub genes in the signature confirmed their functional role in mediating drug sensitivity

- The signature is currently being evaluated as a predictive biomarker in phase II clinical trials

This case demonstrates how clustered heatmap analysis can reveal biologically and clinically meaningful patterns that might be obscured in univariate analyses.

Advanced Analytical Considerations

Statistical Foundations

The interpretation of dendrograms requires understanding of several statistical concepts:

- Distance Metrics: Different measures (Euclidean, Manhattan, correlation-based) capture distinct aspects of similarity and may yield different clustering results.

- Linkage Methods: The algorithm for determining distances between clusters (complete, average, single linkage) affects cluster compactness and shape.

- Cluster Stability: Robust clusters should reproduce across different distance metrics and linkage methods; sensitive clusters may represent artifacts.

Methodological Limitations

While powerful, clustered heatmaps have inherent limitations:

- Color Perception: Human ability to discriminate between similar colors is limited, potentially causing subtle patterns to be overlooked [15].

- Scale Dependence: The apparent importance of clusters is influenced by color scale choices.

- Multiple Testing: The exploratory nature of heatmap analysis raises concerns about false discovery rates.

- Oversimplification: Continuous expression relationships are represented as discrete clusters, potentially obscuring biological continua.

Integration with Complementary Methods

Clustered heatmaps are most powerful when integrated with other analytical approaches:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Use to verify major sources of variation identified in heatmaps.

- Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA): Statistically evaluate functional annotations of identified gene clusters.

- Network Analysis: Model relationships between genes within identified co-expression modules.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between heatmap interpretation and downstream biological insights:

Clustered heatmaps remain a cornerstone of genomic visualization, providing an intuitive yet powerful framework for exploring complex gene expression datasets. Mastery of heatmap interpretation requires understanding both the visual representation and the statistical methods underlying the clustering. By following the systematic analytical protocol outlined in this guide—progressing from data assessment through pattern recognition to biological hypothesis generation—researchers can consistently extract meaningful insights from these visualizations. When combined with appropriate experimental validation and integration with complementary analytical methods, clustered heatmap analysis accelerates the translation of genomic data into biological understanding and therapeutic advances.

A heatmap is a powerful, two-dimensional visualization of data that uses color to represent numerical values, providing a bird's-eye view of complex datasets and allowing for immediate visual pattern recognition [15]. In transcriptomics, heatmaps are indispensable for displaying gene expression data, where each row typically represents a gene and each column represents a sample [2]. The color and intensity of each cell correspond to changes in gene expression levels, enabling researchers to quickly identify interesting patterns across hundreds or thousands of genes simultaneously [2].

When combined with clustering methods, which group genes and/or samples together based on the similarity of their expression patterns, heatmaps become a potent tool for identifying biologically significant signatures [2]. These signatures can reveal genes that are co-regulated, functionally related, or associated with a particular condition, such as a disease state or response to a drug treatment [2]. The primary challenge, however, lies in moving beyond the visual pattern to a robust biological interpretation—understanding why certain genes cluster together and what the sample groupings reveal about the underlying biology.

Technical Foundations: Data Processing and Clustering Algorithms

The biological validity of a heatmap is entirely dependent on the data processing and algorithmic choices made during its creation. Inappropriate preprocessing or an ill-suited clustering method can generate misleading patterns that obscure true biological signals.

Data Preprocessing and Normalization

Raw transcriptomic data, whether from microarrays, RNA-seq, or spatial platforms like Nanostring GeoMx DSP, requires careful preprocessing before visualization [25]. This often includes:

- Normalization: Adjusting for technical variations (e.g., sequencing depth, library preparation efficiency) to enable meaningful biological comparisons. The DgeaHeatmap package, for instance, supports workflows for both raw and normalized count data [25].

- Transformation: Log2 transformation is commonly applied to count data to stabilize variance and make the data more symmetric [26].

- Scaling: For heatmap visualization, Z-score scaling is frequently applied per gene (row-wise) [25] [17]. This converts expression values to standard deviations from the mean, allowing for the comparison of expression patterns across genes with different baseline expression levels. The formula for Z-score calculation is: Z score = (individual value - mean) / standard deviation [17].

- Filtering: To reduce noise and focus on the most informative genes, analyses are often restricted to the most variable genes or genes that show evidence of differential expression [25].

Distance Metrics and Clustering Methods

Clustering is the computational heart of pattern discovery in heatmaps. The choice of distance metric and linkage method fundamentally shapes the resulting clusters.

Table 1: Common Distance Metrics for Clustering Gene Expression Data

| Distance Metric | Formula | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Euclidean Distance | $d(x, y) = \sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{n} (xi - y_i)^2}$ | Measuring absolute, geometric distance in expression space [26]. |

| Pearson Correlation | $r{xy} = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} (xi - \bar{x})(yi - \bar{y})}{\sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{n} (xi - \bar{x})^2} \sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{n} (yi - \bar{y})^2}}$ | Identifying genes with similar expression patterns (shapes), even if their absolute expression levels are different [26]. |

| Un-centered Correlation | Similar to Pearson, but without subtracting the mean [26]. | Useful when the absolute magnitude of expression is considered part of the pattern. |

Table 2: Hierarchical Clustering Linkage Methods

| Linkage Method | Description | Effect on Cluster Shape |

|---|---|---|

| Single Linkage | The linking distance is the minimum distance between two clusters [26]. | Tends to produce long, "chain-like" clusters. |

| Complete Linkage | The linking distance is the maximum distance between two clusters [26]. | Tends to produce tight, compact, "sphere-like" clusters. |

| Average Linkage (UPGMA) | The linking distance is the average of all pair-wise distances between members of the two clusters [26]. | A balanced compromise between single and complete linkage. |

Two primary clustering approaches are used:

- Hierarchical Clustering: An unsupervised method that builds a nested tree structure (dendrogram) to represent the relationships between all data points [26]. This method does not require pre-specifying the number of clusters and is excellent for visualizing the overall data hierarchy.

- K-means Clustering: A partitioning method that divides all genes into a user-defined number (K) of clusters, such that the total distance of all genes to their cluster centers is minimized [25] [26]. The number of clusters (K) is often determined using an elbow plot, which shows the variation explained as a function of the number of clusters [25].

Biological Interpretation of Clustering Patterns

The ultimate goal of a heatmap analysis is to translate visual clusters into biological insights. This requires a systematic, multi-step approach.

Interpreting Sample Clustering

Sample clustering (column clusters) reveals how samples relate to each other based on their global gene expression profiles.

- Biological Replicates: Samples from the same experimental group (e.g., control, treatment) should cluster together, indicating reproducibility and a strong treatment-specific signal [17]. If they do not, it may point to issues with experimental consistency, hidden batch effects, or excessive biological variability.

- Phenotypic or Clinical Groups: Clustering of samples according to known phenotypes (e.g., disease subtype, tumor grade, responder vs. non-responder) validates that the transcriptomic data captures biologically relevant differences. More importantly, unexpected sample groupings can reveal previously unknown subtypes, prompting new hypotheses [2].

- Outliers: A sample that does not cluster with its expected group may be an outlier due to technical artifacts, mislabeling, or represent a genuine, rare biological state that warrants further investigation.

Interpreting Gene Clustering

Gene clustering (row clusters) groups genes with similar expression patterns across the samples.

- Co-regulation: Genes that cluster together are often co-regulated, meaning they may be controlled by the same transcription factors or regulatory pathways [2]. A cluster of genes that are highly expressed in a particular sample group points to activated biological processes in that group.

- Functional Annotation: The most critical step is to biologically characterize each gene cluster. This is typically done using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) or pathway analysis [2]. These tools determine if the genes in a cluster are significantly over-represented in certain biological processes (Gene Ontology), molecular pathways (KEGG, Reactome), or disease signatures.

Integrated Interpretation: Linking Genes and Samples

The most powerful insights come from examining the intersection of gene and sample clusters. A block of intense color (e.g., a "hot spot") where a specific gene cluster meets a specific sample cluster indicates that a set of biologically related genes is coordinately up- or down-regulated in that sample group. For example, a heatmap might reveal a cluster of immune response genes highly expressed only in a subset of tumor samples, suggesting the presence of an immunologically "hot" tumor subtype.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

While a heatmap can generate strong hypotheses, these often require experimental validation. The following are common downstream experimental workflows.

Protocol: Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

Purpose: To determine whether defined sets of genes (e.g., pathways) show statistically significant, concordant differences between two biological states [2]. Methodology:

- Input Preparation: A ranked list of all genes analyzed in the experiment is generated. The ranking is typically based on a metric of differential expression (e.g., fold-change, t-statistic) between two sample groups (e.g., Disease vs. Control).

- Gene Set Collection: Pre-defined gene sets are acquired from databases like MSigDB (Molecular Signatures Database), which include pathways from KEGG, Reactome, and Gene Ontology terms.

- Enrichment Score (ES) Calculation: For each gene set, an ES is computed by walking down the ranked list, increasing a running-sum statistic when a gene in the set is encountered and decreasing it when it is not. The ES represents the degree to which a gene set is overrepresented at the extremes (top or bottom) of the ranked list.

- Significance Assessment: The ES is normalized for the size of the gene set. The null distribution is generated by permuting the gene labels, and a p-value and False Discovery Rate (FDR) are calculated to assess significance.

Protocol: Spatial Validation using Spatial Transcriptomics (ST)

Purpose: To validate that gene expression patterns predicted from histology or discovered via bulk RNA-seq have a genuine spatial context within a tissue [27]. Methodology:

- Tissue Preparation: Fresh frozen or FFPE tissue sections are mounted on specialized glass slides compatible with the ST platform (e.g., 10x Visium).

- Histology Imaging: The tissue section is stained with H&E and imaged to capture its morphological context.

- Permeabilization and cDNA Synthesis: The tissue is permeabilized to release mRNA, which is captured on the slide's barcoded spots. Each spot, typically capturing 1-10 cells, has a unique spatial barcode. On-slide reverse transcription creates barcoded cDNA.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The cDNA is harvested, and a sequencing library is constructed, amplifying the barcoded cDNA fragments. The library is sequenced using high-throughput NGS.

- Data Integration and Analysis: Computational tools (e.g., GeomxTools, standR) are used to align the sequence data back to the spatial barcodes, generating a quantitative map of gene expression that is overlaid on the H&E image [25]. This allows for direct visualization of whether a gene cluster of interest is localized to a specific tissue structure (e.g., tumor margin, immune cell infiltrate).

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Heatmap-Based Studies

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| R Packages (e.g., DgeaHeatmap, pheatmap, ComplexHeatmap) | Provides streamlined functions for differential expression analysis, data preprocessing (Z-score scaling, filtering), and generation of publication-quality clustered heatmaps [25] [17]. | Simplifying end-to-end analysis of transcriptomic data, particularly from platforms like Nanostring GeoMx DSP, for users with limited R expertise [25]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms (e.g., 10x Visium, Nanostring GeoMx) | Enables transcriptome-wide gene expression profiling while retaining the spatial coordinates of the data within a tissue section [25] [27]. | Validating the tissue-level spatial organization of a gene cluster identified in a bulk RNA-seq heatmap. |

| Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) Software | Determines whether an a priori defined set of genes shows statistically significant differences between two biological states [2]. | Objectively interpreting a gene cluster by testing its enrichment for known biological pathways and processes. |

| Pathway Databases (e.g., KEGG, Reactome, Gene Ontology) | Curated repositories of information about biological pathways, molecular interactions, and functional annotations [2]. | Providing the biological context and definitions for gene sets used in enrichment analysis. |

| qPCR Reagents and Assays | Provides a highly sensitive and quantitative method for validating the expression levels of a small number of key genes from a cluster. | Technically validating the differential expression of a few select "hub" genes from a large, significant cluster discovered in the heatmap. |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The application of heatmap analysis continues to evolve with technological advancements. One frontier is the prediction of spatial gene expression directly from histology images using deep learning. Recent benchmarking studies have shown that methods like EGNv2 and Hist2ST can capture biologically relevant gene patterns from H&E images alone, providing a powerful, cost-effective tool to enhance the utility of existing histology archives [27]. Another emerging area addresses the visualization of temporal dynamics. Traditional heatmaps can struggle to effectively capture continuous changes in gene expression over time. Novel methods like Temporal GeneTerrain have been developed to create continuous, integrated views of gene expression trajectories, revealing delayed responses and transient waves of gene activity that static snapshots might miss [28]. These advanced applications demonstrate that the fundamental principle of linking patterns to biology remains central, even as the methods for discovering those patterns grow increasingly sophisticated.

In the analysis of high-throughput genomic data, identifying informative genes is a critical first step for reducing dimensionality and enhancing the biological interpretability of downstream analyses. Two fundamental classes of such genes are Highly Variable Genes (HVGs) and Spatially Variable Genes (SVGs). HVGs are identified in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data and exhibit significant expression variation across individual cells, often reflecting underlying biological heterogeneity [29] [30]. SVGs, a conceptual extension of HVGs, are identified in spatially resolved transcriptomics (SRT) data and exhibit non-random, informative spatial patterns across tissue locations [29] [31].