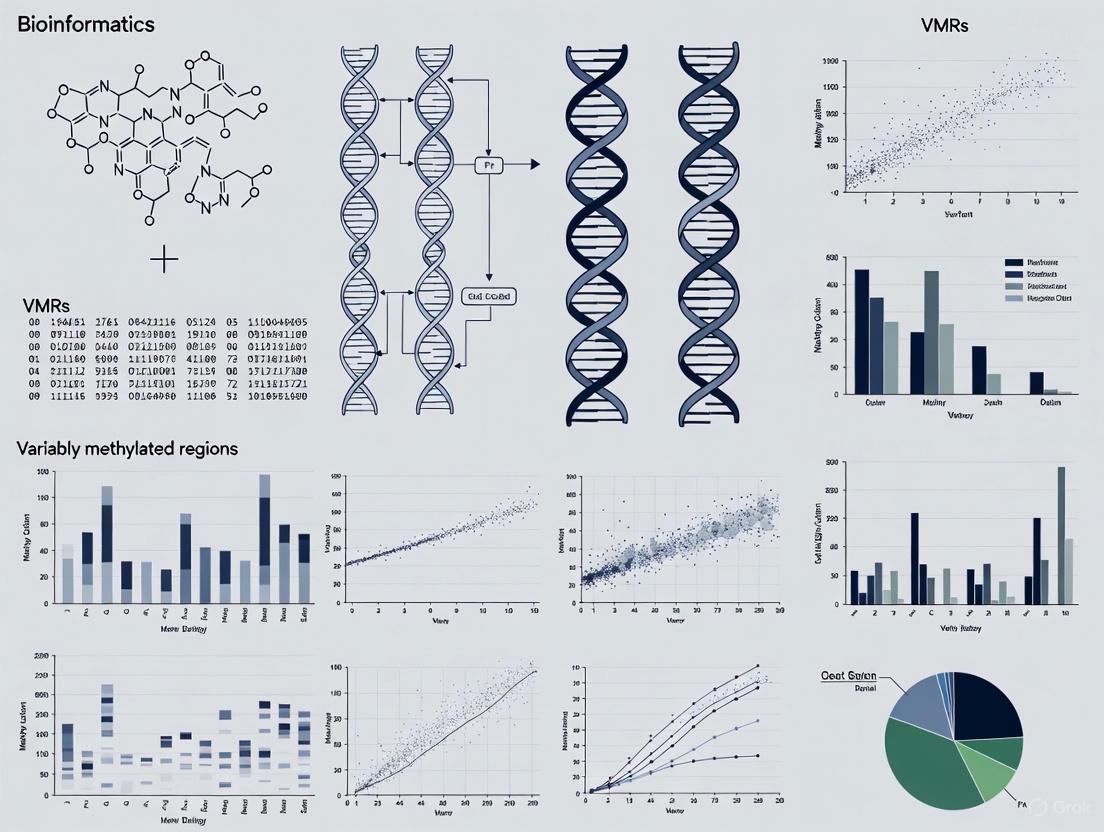

Identifying Variably Methylated Regions (VMRs) in scBS Data: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on identifying and analyzing Variably Methylated Regions (VMRs) from single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS) data.

Identifying Variably Methylated Regions (VMRs) in scBS Data: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on identifying and analyzing Variably Methylated Regions (VMRs) from single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS) data. We cover foundational principles of DNA methylation heterogeneity, evaluate advanced computational methods including MethSCAn and vmrseq, address critical troubleshooting strategies for sparse and noisy data, and present rigorous validation frameworks. By integrating the latest methodological advances with practical application guidelines, this resource aims to empower scientists to accurately pinpoint epigenetic features of cell types and states, facilitating discoveries in developmental biology, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development.

Understanding VMRs and Their Biological Significance in Single-Cell Epigenomics

Defining Variably Methylated Regions (VMRs) and Their Role in Cellular Heterogeneity

In multicellular organisms, even morphologically identical cells can exhibit substantial functional differences. This cellular heterogeneity is crucial for development, tissue function, and disease processes like cancer [1]. While genetic variation plays a role, epigenetic mechanisms—particularly DNA methylation—are fundamental in establishing and maintaining this diversity without altering the underlying DNA sequence [1].

Variably Methylated Regions (VMRs) represent segments of the genome where DNA methylation patterns show significant intercellular or interindividual variation. These regions are not merely stochastic artifacts but are biologically significant, as they identify "regions of stochastic epigenetic variation in developmentally important genes" and serve as "a new type of molecular fingerprint stable over more than a decade" [2]. In essence, VMRs represent structured epigenetic variation that contributes to phenotypic diversity in cell populations.

The advent of single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS) technologies has revolutionized our ability to study these epigenetic patterns at unprecedented resolution, moving beyond bulk tissue averages to reveal the complex mosaic of methylation states in individual cells [3] [1]. This technical advancement has positioned VMR analysis as a powerful tool for deciphering the epigenetic underpinnings of cellular heterogeneity.

Technical Foundations: Analyzing VMRs from scBS Data

Computational Challenges in scBS Data Analysis

Single-cell bisulfite sequencing generates sparse and noisy data that presents significant computational challenges. Typically, 80% to 95% of CpG dinucleotides are not observed in high-throughput scBS studies, creating substantial gaps in methylation measurements for individual cells [3]. Additional technical variability arises from amplification biases and errors inherent to working with minimal input DNA [3].

The standard analytical approach involves dividing the genome into tiles (often 100 kb) and calculating average methylation fractions for each tile per cell [4]. However, this method can lead to signal dilution and fails to optimally capture biologically relevant patterns [4]. The sparsity of coverage means that many tiles contain limited information, reducing statistical power for detecting true variation.

Improved Methodologies for VMR Detection

Recent methodological advances have addressed these limitations through more sophisticated computational approaches:

Read-position-aware quantitation: MethSCAn improves quantification by first obtaining a smoothed average of methylation across all cells for each CpG position, then quantifying each cell's deviation from this average using shrunken residuals. This approach reduces variance compared to simple averaging of raw methylation calls [4].

Probabilistic modeling with vmrseq: This two-stage method first scans the genome for candidate regions containing consecutive CpGs with evidence of cell-to-cell variation, then applies a hidden Markov model (HMM) to determine whether a VMR is present and precisely define its boundaries [3] [5]. The HMM models methylation states of individual CpG sites while accounting for technical noise and spatial correlation between nearby sites [3].

Smoothing and threshold-based approaches: Methods like kernel smoothing help mitigate limited coverage and counteract noise in single-cell data [3] [2]. Statistical thresholds are then applied to identify genomic regions showing variability above background levels, with significance calculations specifically designed for variability rather than mean differences [2].

Table 1: Key Computational Tools for VMR Detection from scBS Data

| Tool/Method | Core Approach | Key Advantages | Applicable Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| vmrseq [3] [5] | Two-stage method: candidate region identification + hidden Markov model | Base-pair resolution; sensitive to heterogeneity level; no predefined regions needed | scBS-seq, other single-cell methylation protocols |

| MethSCAn [4] | Read-position-aware quantitation using shrunken residuals | Better discrimination of cell types; reduces need for large cell numbers | scBS-seq data |

| Sliding Window + Thresholding [2] [6] | Identify clusters of neighboring CpGs with high variability | Simple implementation; proven in population studies | Bulk methylation arrays, single-cell data |

The following diagram illustrates the core analytical workflow of vmrseq, one of the most sophisticated methods for VMR detection from scBS data:

Experimental Protocols: From Data Generation to VMR Detection

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

Proper sample preparation is critical for generating high-quality scBS data. The following protocol outlines key steps based on established methodologies:

Cell Processing and Quality Control:

- Cell isolation: Use fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting (FANS) with NeuN (RBFOX3) staining to purify neuronal nuclei when studying brain tissues [7]. Similar cell-type-specific markers should be used for other tissues.

- Bisulfite conversion: Treat DNA with bisulfite to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils while preserving methylated cytosines.

- Library preparation and sequencing: Generate libraries using scBS protocols and sequence with sufficient depth (typically >10X coverage post-processing) [7].

- Quality filtering:

- Remove cells with high non-conversion rates (>1% in mouse, >2% in human)

- Eliminate potential contaminated samples with low numbers of non-clonal mapped reads

- Exclude cells with exceptionally high coverage that may indicate multiple cells per well

- Filter out cells with low CpG site coverage (<50,000 CpGs) [5]

Data Processing and VMR Detection with vmrseq

For the vmrseq method, the analytical workflow proceeds as follows:

Data Preprocessing:

- Process individual-cell read files into a binary methylation matrix using the

poolDatafunction - Format data as a

SummarizedExperimentobject with CpG sites as rows and cells as columns - Remove sites with hemimethylation or intermediate methylation levels (0 < methread/totalread < 1) [5]

VMR Detection:

- Smoothing stage: Perform kernel smoothing on single-cell methylation data using the

vmrseqSmoothfunction - Model fitting: Apply the

vmrseqFitfunction to:- Define candidate regions based on variance thresholds

- Fit hidden Markov models to detect VMRs

- Determine precise genomic boundaries of identified VMRs [5]

- Parallelization: Use BiocParallel to register multiple cores for computationally efficient analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for VMR Analysis

| Category | Item/Software | Specification/Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | NeuN (RBFOX3) Antibody [7] | Neuronal nuclei purification | Cell-type-specific isolation |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | DNA treatment | Converts unmethylated C to U | |

| scBS Library Prep Kit | Library preparation | Single-cell bisulfite sequencing | |

| Computational Tools | vmrseq R Package [3] [5] | VMR detection | Probabilistic modeling; base-pair resolution |

| MethSCAn [4] | scBS data analysis | Read-position-aware quantitation | |

| Bioconductor [5] | Analysis framework | Genomic data analysis ecosystem | |

| Data Formats | BED-like files [5] | Input format | chr, pos, strand, methread, totalread |

| SummarizedExperiment [5] | Data container | Efficient representation of methylation data | |

| HDF5 format [5] | Data storage | Memory-efficient handling of large datasets |

Biological Significance and Research Applications

VMRs as Markers of Cellular Heterogeneity and Disease

VMRs identified through scBS analysis provide crucial insights into both normal development and disease processes. Studies of human brain regions have revealed that neuronal VMRs in the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex, and hippocampus are "enriched for heritability of schizophrenia," suggesting that epigenetic variation in these regions contributes to neuropsychiatric disorder risk [7].

Beyond the brain, VMRs form co-regulated networks that differ between cell types and are enriched for specific transcription factor binding sites and biological pathways with functional relevance to each tissue [6]. For example:

- In T cells, networks of co-regulated VMRs are enriched for genes involved in T-cell activation

- In fibroblasts, VMR networks comprise HOX gene clusters and are enriched for control of tissue growth

- In neurons, VMR networks are enriched for genes with roles in synaptic signaling [6]

These patterns demonstrate that VMRs are not randomly distributed but reflect functionally coordinated epigenetic regulation that defines cell identity and function.

Environmental Responsiveness of VMRs

A subset of VMRs shows low heritability and appears responsive to environmental influences. Studies culturing genetically identical fibroblasts under varying conditions demonstrated that "some VMR networks are responsive to the environment, with methylation levels at these loci changing in a coordinated fashion in trans dependent on cellular growth" [6]. Intriguingly, these environmentally responsive VMRs show "strong enrichment for imprinted loci (p<10â»â¸â°)," suggesting particular sensitivity to environmental conditions [6].

Applications in Drug Development and Biomarker Discovery

The ability to profile epigenetic heterogeneity at single-cell resolution has important implications for drug development. VMR analysis can:

- Identify patient subgroups with distinct epigenetic profiles for targeted therapies

- Monitor epigenetic responses to pharmacological interventions

- Discover epigenetic biomarkers for disease diagnosis and progression monitoring

- Understand mechanisms of drug resistance in cancer and other diseases

In neuropsychiatric drug development, for instance, brain region-specific VMRs associated with disease risk may represent novel therapeutic targets or biomarkers for treatment response [7].

Variably Methylated Regions represent a critical layer of epigenetic regulation that contributes substantially to cellular heterogeneity in health and disease. Advanced single-cell bisulfite sequencing technologies, coupled with sophisticated computational tools like vmrseq and MethSCAn, now enable precise mapping of these regions at single-cell resolution. The detection and analysis of VMRs provides insights into developmental processes, cellular responses to environmental stimuli, and the epigenetic underpinnings of complex diseases. As these methodologies continue to evolve, VMR analysis promises to become an increasingly powerful approach for understanding epigenetic diversity and its functional consequences across biological systems.

Single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS) represents a transformative advancement in epigenomics, enabling the assessment of DNA methylation at single-base pair and single-cell resolution. This technology has opened new avenues for understanding cellular heterogeneity, developmental processes, and disease mechanisms. However, the analysis of scBS data, particularly for identifying variably methylated regions (VMRs) crucial for understanding cell-type-specific regulation, faces three fundamental technological challenges: extreme data sparsity, substantial technical noise, and incomplete genomic coverage.

The pursuit of VMR identification exemplifies the core challenge in scBS analysis. VMRs are genomic regions showing methylation variability across cells, often associated with dynamic regulatory elements such as enhancers. Unlike consistently methylated or unmethylated regions, VMRs contain rich information about cell state differences. However, their detection requires sufficient data density and quality to distinguish genuine biological variation from technical artifacts. The inherent limitations of scBS data thus create a significant bottleneck for discovering these functionally important regions.

This technical guide examines the sources and consequences of these limitations while providing actionable solutions for researchers aiming to extract biologically meaningful signals from scBS data, with particular emphasis on robust VMR identification within the context of broader research on cellular heterogeneity and epigenetic regulation.

Understanding the Core Technical Limitations

The Sparsity Challenge

Data sparsity in scBS arises from both biological and technical factors. Each single cell contains only two copies of the genome, and the bisulfite conversion process required for methylation detection is destructive, leading to substantial DNA degradation and loss. Consequently, for any given cell, most CpG sites remain unobserved. Sparsity levels typically range from 80% to 95% of CpGs missing per cell, creating significant challenges for direct cell-to-cell comparisons [8].

The impact of sparsity is particularly pronounced in VMR identification, as distinguishing true methylation heterogeneity from random missing data becomes statistically challenging. When coverage is sparse, even regions with genuine biological variability may appear uniformly methylated or unmethylated in individual cells due to limited sampling of CpG sites.

Technical Noise and Signal Dilution

Beyond sparsity, scBS data contain multiple sources of technical noise. The bisulfite conversion process is incomplete, with conversion rates typically below 99%, introducing false positive methylation signals. Amplification biases during library preparation and sequencing errors further contribute to noise. A common but problematic approach to managing sparsity and noise involves dividing the genome into large tiles (e.g., 100 kb) and averaging methylation signals within each tile. This coarse-graining approach leads to signal dilution, where small but biologically important VMRs are obscured by surrounding regions with different methylation patterns [4].

Coverage Limitations

scBS methods suffer from limited genomic coverage compared to bulk approaches. While techniques like scBS-seq and scWGBS aim for whole-genome coverage, the efficiency of library generation varies substantially. Traditional scBS methods typically cover only 5-30% of CpGs per cell, even at moderate sequencing depths [9]. This sparse sampling hinders comprehensive analysis of regulatory elements, as many key promoters and enhancers may have insufficient coverage for confident methylation assessment in individual cells.

Table 1: Comparison of scBS Method Performance Characteristics

| Method | Typical CpG Coverage per Cell | Bisulfite Conversion Efficiency | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scBS-seq | 5-15% | High (~99.5%) | Established protocol | Low coverage, high sparsity |

| scWGBS | 10-20% | High (~99.5%) | Whole-genome coverage | Inefficient library generation |

| snmC-seq2 | 15-25% | High (~99.5%) | Improved mapping efficiency | Low library yield |

| Cabernet (bisulfite-free) | ~30% | Lower (~98.5%) | Higher coverage, measures 5hmC | Incomplete conversion, methylation bias |

| scDEEP-mC | ~30% | High (~99.5%) | High complexity, efficient libraries | Technical complexity |

Computational Strategies for Enhanced Analysis

Improved Quantification Methods

Novel computational approaches address sparsity and noise more effectively than simple averaging. Read-position-aware quantitation represents one significant advancement. Instead of averaging raw methylation calls within large genomic windows, this method first computes a smoothed ensemble methylation average across all cells for each CpG position, then quantifies each cell's deviation from this average as shrunken residuals. This approach reduces variance in situations where reads from different cells cover non-overlapping CpGs within the same region but show no actual evidence of differential methylation [4].

The MethSCAn toolkit implements this residual-based quantification, using kernel smoothing (typically with 1,000 bp bandwidth) to obtain stable ensemble averages despite sparse coverage. The resulting shrunken mean residuals provide a more reliable measure of relative methylation for downstream analysis, enabling better discrimination of cell types with fewer cells required [4].

Bayesian Modeling for Heterogeneity Quantification

scMET employs a hierarchical Bayesian framework specifically designed to overcome scBS data limitations. The model uses a beta-binomial distribution to capture both technical and biological variability, sharing information across cells and genomic features to overcome sparsity. A key innovation in scMET is the introduction of residual overdispersion parameters as a measure of cell-to-cell DNA methylation variability that is not confounded by mean methylation levels [8].

The scMET framework enables three critical analyses particularly relevant to VMR identification:

- Highly Variable Feature (HVF) detection identifies genomic features driving epigenetic heterogeneity

- Differential mean methylation testing between cell groups

- Differential variability testing to detect features with significantly different methylation heterogeneity between conditions

Table 2: Computational Tools for Addressing scBS Limitations

| Tool | Core Methodology | Primary Application | Advantages for VMR Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| MethSCAn | Read-position-aware quantitation with shrinkage | Cell type discrimination, DMR detection | Reduces variance from sparse coverage |

| scMET | Hierarchical Bayesian modeling | HVF detection, differential variability testing | Explicitly quantifies biological heterogeneity |

| Melissa | Bayesian mixture modeling | Methylation state imputation | Shares information across cells and genomic regions |

| DeepCpG | Deep neural networks | Imputation of missing methylation states | Captures complex patterns in methylation data |

Feature Selection Strategies

Rather than analyzing the entire genome, informed feature selection significantly improves VMR detection. Focusing on genomic regions with higher potential for biological variability, such as enhancers and gene regulatory elements, increases signal-to-noise ratio. The standard approach of tiling the genome into fixed-size intervals is suboptimal because VMR boundaries rarely align with arbitrary tile borders [4].

Supervised feature selection using existing annotations of regulatory elements or unsupervised approaches that identify regions with sufficient coverage and variability across the cell population can enhance detection power. scMET's HVF detection provides a principled approach for this selection, prioritizing features that contribute most to epigenetic heterogeneity while controlling for false discoveries.

Experimental and Technical Advancements

Bisulfite-Free Methods

Emerging bisulfite-free approaches address fundamental limitations of conventional scBS. The Cabernet method utilizes enzymatic conversion instead of bisulfite treatment, combining TET oxidation, BGT-mediated glycosylation, and APOBEC-mediated deamination to detect 5mC and 5hmC at single-base resolution without DNA degradation. This approach approximately doubles genomic coverage compared to scBS-seq while enabling simultaneous profiling of 5hmC modifications [10].

Cabernet incorporates several key innovations:

- Tn5 transposome fragmentation minimizes DNA loss

- Carrier DNA prevents dsDNA loss during purification

- Direct library amplification without ssDNA purification

These improvements yield higher mapping rates and more uniform coverage, though enzymatic conversion methods may have slightly lower specificity (99.7% recall for 5hmC, 98.5% for 5mC) compared to bisulfite-based approaches [10].

Protocol Optimization

Substantial improvements can be achieved through optimization of existing scBS protocols. The scDEEP-mC method enhances traditional PBAT approaches through several key modifications:

- Cell sorting directly into high-concentration bisulfite buffer eliminates cleanup-related DNA loss

- Base-composition-adjusted random nonamers complement the bisulfite-converted genome (49% A, 20% C, 30% T, 1% G in CpG context)

- Careful primer titration minimizes off-target priming and adapter dimers

- Directional library construction enables more efficient alignment

These optimizations result in libraries with high complexity and sequencing efficiency, allowing coverage of approximately 30% of CpGs at moderate sequencing depths (20 million reads/cell) while maintaining high bisulfite conversion rates [9].

Allele-Resolved Methylation Analysis

Advanced methods now enable allele-resolved methylation analysis in single cells, providing insights into imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, and replication dynamics. scDEEP-mC facilitates this through high-coverage data and bisulfite-aware phasing algorithms. This capability is particularly valuable for distinguishing hemi-methylation patterns during DNA replication from genuine epigenetic heterogeneity, reducing misinterpretation in VMR identification [9].

Integrated Analysis Workflow for VMR Identification

Preprocessing and Quality Control

A robust preprocessing pipeline is essential for mitigating scBS limitations. Key steps include:

- Alignment with bisulfite-aware tools (Bismark, BWA-meth)

- Duplicate marking to remove PCR artifacts

- Cytosine conversion rate assessment (≥99% in CpY context for bisulfite methods)

- Filtering of low-quality cells based on coverage and conversion metrics

- Doublet detection to exclude multiplets with methylation discordance

For Cabernet and other enzymatic methods, specific quality controls must address conversion efficiency using spike-in controls and monitor potential methylation biases [10] [9].

Analytical Framework for VMR Detection

An integrated analytical workflow maximizes the potential for robust VMR identification:

- Quality-controlled data processing following best practices for scBS data

- Methylation quantification using read-position-aware methods (MethSCAn) rather than simple averaging

- Feature definition using pre-annotated regulatory elements or variable-sized windows

- Hierarchical modeling with scMET to quantify biological heterogeneity

- HVF detection using probabilistic decision rules controlling false discovery rate

- Differential testing between cell groups or conditions

- Biological validation through integration with complementary assays

This workflow explicitly addresses sparsity through information sharing across cells and features, reduces noise through appropriate statistical modeling, and maximizes coverage efficiency through focused analysis of informative genomic regions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scBS Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium bisulfite | Cytosine conversion | High-purity grades improve conversion efficiency; concentration affects DNA damage |

| Tagged random nonamers | Library amplification | Base composition should complement bisulfite-converted genome (49% A, 20% C, 30% T, 1% G) |

| Tn5 transposase | DNA fragmentation (Cabernet) | Enables high-throughput profiling; reduces DNA loss compared to sonication |

| TET2/BGT/APOBEC enzymes | Enzymatic conversion (Cabernet) | Enables bisulfite-free conversion; specific for 5mC/5hmC detection |

| SPRI beads | Size selection and cleanup | Ratio affects size selection stringency; critical for removing primer dimers |

| Carrier DNA | Minimize adsorption loss (Cabernet) | Inert DNA (e.g., lambda phage) preserves low-input samples during purification |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Duplicate identification | Critical for distinguishing PCR duplicates from unique molecules |

| Methylated control DNA | Conversion monitoring | Spike-in controls essential for assessing conversion efficiency |

| Tin tetrabutanolate | Tin Tetrabutanolate|CAS 14254-05-8|Supplier | |

| (S)-(-)-Nicotine-15N | (S)-(-)-Nicotine-15N|High-Purity Isotope for Research | Explore (S)-(-)-Nicotine-15N, a stable isotope-labeled internal standard for precise LC-MS/MS quantitation in ADME and metabolic studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The technological challenges of scBS data - sparsity, noise, and coverage limitations - remain significant but not insurmountable barriers to robust VMR identification. Strategic approaches combining improved experimental methods with advanced computational techniques are steadily overcoming these limitations.

Future progress will likely come from several directions: continued development of bisulfite-free methods with higher efficiency and accuracy, integrated multi-omic approaches that leverage complementary information from transcriptomics or chromatin accessibility, and more sophisticated machine learning methods that can better distinguish technical artifacts from biological signals. The application of foundation models pretrained on large-scale methylation datasets shows particular promise for improving analysis of sparse single-cell data [11].

As these technologies mature, the identification of VMRs from scBS data will become increasingly routine, providing deeper insights into the epigenetic regulation of development, disease, and cellular heterogeneity. By understanding and addressing the current technical limitations, researchers can design more effective studies and extract richer biological knowledge from their single-cell methylome experiments.

In the realm of epigenetics, Variably Methylated Regions (VMRs) represent genomic areas where DNA methylation patterns show significant variation across cells or individuals. Unlike static epigenetic marks, VMRs capture dynamic regulatory information that provides a window into cellular identity, developmental history, and disease susceptibility. DNA methylation, which involves the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases primarily at CpG dinucleotides, is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism that governs gene expression and chromatin organization without altering the underlying DNA sequence [12] [13]. While approximately 60-80% of CpGs in the human genome are consistently methylated, VMRs constitute the subset of the epigenome where this methylation is variable and potentially informative [13].

The emergence of single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS) technologies has revolutionized our ability to study VMRs at unprecedented resolution. This technique enables the assessment of DNA methylation at single-base pair resolution in individual cells, revealing the epigenetic heterogeneity that exists within seemingly homogeneous cell populations [4]. As we transition from bulk tissue analyses to single-cell approaches, VMR identification has become increasingly crucial for deciphering the complex epigenetic landscape that underpins cellular diversity in development, normal physiology, and disease states.

VMRs as Determinants and Reflectors of Cellular Identity

Establishing and Maintaining Cell Identity

DNA methylation serves as a stable epigenetic mark that can be inherited through multiple cell divisions, functioning as a component of cellular memory [13]. During development and cell differentiation, DNA methylation patterns are dynamic, but specific configurations are retained to maintain cell type-specific gene expression states that define cellular identity and function [12] [14]. VMRs are particularly enriched at genomic elements that must remain responsive to environmental cues and developmental signals, such as enhancers and other regulatory regions [4].

The remarkable fidelity of DNA methylation patterns in defining cell types is evidenced by recent comprehensive methylome atlases. Studies have demonstrated that replicates of the same cell type show greater than 99.5% identity in their methylation patterns, highlighting the robustness of cell identity programs to environmental perturbation [14]. This conservation of epigenetic patterns across individuals underscores that DNA methylation is primarily determined by cell lineage and cell-type-specific programs rather than genetic or environmental factors alone.

Lineage Tracing and Developmental History

VMRs not only reflect current cellular identity but also encode information about developmental history. Unsupervised clustering of methylomes systematically groups biological samples of the same cell type and recapitulates key elements of tissue ontogeny [14]. For example:

- Pancreatic islet cell types (alpha, beta, and delta) cluster together, reflecting their origin from the same embryonic endocrine progenitor

- Endoderm-derived cells (such as hepatocytes and pancreatic cells) cluster separately from ectoderm-derived neurons despite shared functional characteristics

- Shared methylation patterns can be traced back to early developmental stages, with some regions maintaining methylation states established in germ layers

These observations demonstrate that VMR patterns can serve as persistent records of developmental lineage, retained since embryonic development and maintained throughout an organism's lifespan [14].

Methodological Approaches for VMR Analysis in scBS Data

Analytical Challenges in scBS Data

The analysis of scBS data presents unique computational challenges that differ from those encountered in bulk sequencing approaches. The standard method for constructing a methylation matrix from scBS data has been to divide the genome into large tiles (e.g., 100 kb) and calculate the average methylation within each tile for every cell [4]. This coarse-graining approach aims to reduce data size, improve signal-to-noise ratio, and provide interpretability for downstream analyses similar to those used in single-cell RNA sequencing (such as clustering and trajectory inference).

However, this conventional approach has significant limitations. Dividing the genome into fixed, equally-sized intervals is biologically arbitrary and unlikely to align with functional epigenetic units. More critically, this method can lead to signal dilution, where genuinely variable methylation signals are averaged out with non-variable regions, reducing the ability to distinguish biologically meaningful patterns [4]. This is particularly problematic in scBS data where read coverage per cell is inherently sparse.

Advanced Strategies for VMR Identification

Read-Position-Aware Quantitation

Novel approaches address these limitations by implementing read-position-aware quantitation that considers the spatial distribution of methylation signals. Rather than simply averaging raw methylation calls within a region, these methods:

- Compute ensemble averages: For each CpG position, calculate a smoothed average methylation across all cells using kernel smoothing (e.g., with 1,000 bp bandwidth) to create a reference methylation landscape [4]

- Calculate cell-specific residuals: For each cell, measure deviations from the ensemble average at each covered CpG site, with positive values indicating methylation above average and negative values indicating unmethylated positions relative to the average

- Apply shrinkage toward zero: Compute shrunken means of these residuals using pseudocounts to trade bias for variance, effectively dampening signals in cells with low coverage

This approach significantly improves the signal-to-noise ratio by reducing variation in situations where reads from different cells cover non-overlapping portions of a region but show no actual evidence of differential methylation when their coverage areas align [4].

Identifying Genuinely Variable Regions

A critical advancement in VMR analysis is the focused identification of genuinely variable genomic regions rather than uniformly tiling the genome. This strategy recognizes that many genomic regions show consistent methylation patterns across cells (e.g., CpG-rich promoters of housekeeping genes are uniformly unmethylated, while much of the remaining genome is highly methylated regardless of cell type) [4]. Only the subset of regions showing meaningful variability across cells contains discriminatory information for distinguishing cell types or states.

The MethSCAn toolkit implements improved strategies to identify these informative regions for methylation quantification, enabling better discrimination of cell types with reduced requirements for large cell numbers [4]. These approaches typically involve:

- Scanning the genome for regions with high intercellular methylation variance

- Applying statistical thresholds to distinguish biological variability from technical noise

- Integrating complementary epigenetic annotations to prioritize functional regions

Experimental Workflow for VMR Analysis

The table below outlines key computational tools and their applications in VMR analysis from scBS data:

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for VMR Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MethSCAn [4] | Comprehensive scBS data analysis | Implements read-position-aware quantitation, identifies informative regions, detects DMRs | Cell type discrimination, differential methylation analysis |

| wgbstools [14] | WGBS data processing and analysis | Segments genome into methylation blocks, identifies differentially methylated regions | Methylome atlas construction, cell-type-specific marker identification |

| ChromHMM [15] | Chromatin state discovery | Uses multivariate HMM to learn combinatorial epigenetic patterns across individuals | Identification of global patterns of epigenetic variation |

| ChAMP [16] | Methylation array data processing | Processes IDAT files, performs probe filtering, calculates beta values | Microarray-based methylation analysis, quality control |

Visualizing the Analytical Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comparative workflow between conventional and advanced methods for VMR analysis in scBS data:

Diagram 1: scBS Data Analysis Workflow Comparison

VMRs in Disease Pathogenesis and Dysregulation

Cancer and Aberrant Methylation Patterns

Cancer cells frequently exhibit widespread disruption of normal DNA methylation patterns, characterized by both genome-wide hypomethylation and site-specific hypermethylation [13] [17]. These aberrant methylation states can be conceptualized as pathological VMRs that contribute to tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms:

- Hypomethylation of normally repressed regions can lead to chromosomal instability and activation of oncogenes

- Hypermethylation of CpG islands in promoter regions can result in silencing of tumor suppressor genes

- Epigenetic noise enables cancer cells to sample more of the genome, activating programs specific to other tissues to develop into more aggressive, malignant states [18]

The early aberrant DNA methylation states occurring during cellular transformation appear to be retained during tumor evolution, making them valuable markers for understanding cancer lineage and progression [13]. Similarly, DNA methylation differences among different regions of a tumor reflect the history of cancer cells and their response to the tumor microenvironment.

Neurodevelopmental and Neuropsychiatric Disorders

VMR analysis has revealed significant epigenetic disturbances in neurodevelopmental disorders. Studies of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have identified global patterns of epigenetic variation that differentiate cases from controls in prefrontal cortex tissue [15]. These findings suggest that coordinated epigenetic dysregulation at multiple genomic loci may contribute to the complex pathophysiology of ASD.

The stacked ChromHMM model applied to histone modification data from ASD cases and controls has demonstrated that global patterns of epigenetic variation are associated with diagnosis status, reflecting known associations with molecular features [15]. This approach enables researchers to move beyond single-locus analyses to identify system-level epigenetic disturbances that may underlie complex neuropsychiatric conditions.

Imprinting Disorders and Multi-Locus Methylation Defects

Imprinting disorders provide compelling examples of how VMR dysregulation leads to disease. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS), a condition linked to overgrowth and tumors, is frequently associated with loss of methylation at the KCNQ1OT1-TSS germline differentially methylated region (gDMR) on chromosome 11p15.5 [19]. Approximately one-third of BWS patients with this specific epigenetic defect exhibit multi-locus imprinting disturbances (MLID), affecting multiple genomic regions beyond the primary locus.

Research has demonstrated that BWS patients with MLID show highly variable methylation changes affecting both imprinted and non-imprinted loci in a seemingly stochastic manner throughout the genome [19]. These findings support the hypothesis that MLID results from interactions between maternal-effect genes and environmental factors in aged oocytes, leading to disordered DNA methylation across the genome.

Disease-Associated VMR Patterns

Table 2: VMR Patterns in Human Diseases

| Disease Category | Specific Condition | VMR Characteristics | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imprinting Disorders | Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) | Loss of methylation at KCNQ1OT1-TSS gDMR; multi-locus disturbances in 1/3 of cases | Overgrowth, tumor susceptibility, stochastic genome-wide methylation changes [19] |

| Cancer | Multiple cancer types | Genome-wide hypomethylation; promoter-specific hypermethylation; increased epigenetic noise | Oncogene activation, tumor suppressor silencing, tissue identity confusion [13] [18] |

| Neurodevelopmental Disorders | Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | Global patterns of epigenetic variation in prefrontal cortex; correlated histone modifications | Altered gene regulation in brain development and function [15] |

| Autoimmune Disease | Thymic epithelial cell dysfunction | Epigenetic noise enabling promiscuous gene expression; p53 downregulation | Failure to eliminate self-reactive T cells, multi-organ autoimmunity [18] |

Technological Advances and Future Directions in VMR Research

Emerging Technologies for VMR Analysis

The field of VMR research is being transformed by several technological advances:

- Single-cell multi-omics approaches that simultaneously profile DNA methylation alongside other molecular features such as chromatin accessibility or gene expression

- Long-read sequencing technologies that enable phased methylation detection, providing haplotype-resolution epigenetic information

- Spatially resolved epigenomics that contextualizes VMR patterns within tissue architecture

- CRISPR-based epigenetic editing that allows functional validation of VMR roles in gene regulation

Therapeutic Targeting of Disease-Associated VMRs

The dynamic nature of epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, makes them attractive therapeutic targets. Several strategies are being explored:

- DNMT inhibitors (e.g., azacitidine, decitabine) that reverse hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes

- Combination therapies that target multiple epigenetic regulators simultaneously

- Nanoparticle-based delivery systems that improve the specificity and efficacy of epigenetic drugs while reducing side effects [17]

- Context-specific epigenetic modulation that considers the cellular environment and disease state

As epigenetic therapies continue to evolve, VMR analysis will play an increasingly important role in identifying responsive patient populations, monitoring treatment efficacy, and understanding mechanisms of resistance.

VMRs represent a critical dimension of epigenetic regulation that transcends static genomic information to capture dynamic aspects of cellular identity and function. The integration of advanced computational methods with single-cell technologies has dramatically enhanced our ability to identify and interpret VMRs, revealing their essential roles in development, cellular differentiation, and disease pathogenesis. As we continue to decipher the complex language of epigenetic variation, VMR analysis promises to yield novel biomarkers for disease diagnosis and prognosis, uncover fundamental mechanisms of gene regulation, and inspire new therapeutic approaches for a wide range of human diseases. The ongoing development of comprehensive epigenetic databases and analytical tools will further accelerate our understanding of how variable methylation shapes biological complexity and disease susceptibility across diverse cell types and physiological contexts.

Enhancers are distal cis-regulatory elements that orchestrate spatiotemporal gene expression patterns during development by integrating transcription factor binding, epigenetic modifications, and environmental signals. This technical guide examines enhancer biology within the context of identifying variably methylated regions (VMRs) in single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS) data, with emphasis on methodology, data analysis challenges, and clinical applications. We provide comprehensive protocols for enhancer characterization, computational frameworks for VMR detection, and integrative approaches linking enhancer dysfunction to disease pathogenesis, offering researchers a structured pathway for investigating the epigenetic regulation of developmental genes and environmentally responsive elements.

Enhancers are short DNA sequences (typically 200-1500 bp) that function as cis-regulatory elements to control gene expression from distances ranging from several kilobases to over one megabase, independent of orientation and position [20] [21]. First identified in the Simian virus 40 (SV40) genome, enhancers serve as docking platforms for transcription factors that interpret developmental and environmental cues in a highly context-specific manner [20]. The functional definition of an enhancer hinges on its ability to activate transcription of a target gene through spatial proximity, often facilitated by chromatin looping that brings distant regulatory elements into contact with promoters [22] [21].

Enhancer activity is precisely orchestrated during development through combinatorial binding of lineage-determining transcription factors to cell type-specific enhancer signatures [20]. Mammals possess approximately 200 specialized cell types, each with distinct transcriptional outcomes reflecting unique enhancer repertoires that represent only a small subset of all genomic regulatory domains [20]. The pre-established enhancer landscape plays a crucial role in lineage determination, with disturbances in this landscape affecting cellular differentiation potential and potentially contributing to disease states [20].

Table 1: Key Features of Enhancer Elements

| Feature | Description | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Distance Independence | Can function from distances up to 1 Mb from target gene | Enables complex regulatory networks with limited coding sequences |

| Orientation Independence | Functions in either forward or reverse orientation | Provides evolutionary stability to regulatory elements |

| Cell Type Specificity | Activity restricted to specific cell types or developmental stages | Drives cellular differentiation and lineage commitment |

| Combinatorial Binding | Contains multiple transcription factor binding sites | Integrates diverse signaling inputs for precise expression control |

| Tissue-Specific Epigenetic Marks | Defined histone modifications (H3K4me1, H3K27ac) | Facilitates identification and functional characterization |

Enhancer Classification and Epigenetic Signatures

Enhancers exist in distinct functional states characterized by specific histone modification patterns that define their regulatory potential [20]. Primed enhancers are marked by histone H3 lysine 4 monomethylation (H3K4me1) alone and represent a transcriptionally poised state. Active enhancers carry both H3K4me1 and H3K27ac marks and are associated with active gene regulation. Poised enhancers contain H3K4me1 with the repressive mark H3K27me3 but lack H3K27ac, typically associating with developmental genes that remain inactive in stem cells but become expressed during differentiation [20]. During cellular differentiation, poised enhancers lose H3K27me3, acquire H3K27ac, and transition to an active state, functioning as molecular switches that tune target gene expression during the transition from undifferentiated to differentiated phenotypes [20].

Super-enhancers (SEs), also termed stretch enhancers or enhancer clusters, represent large clusters of active enhancers with robust enrichment for transcriptional coactivators [20]. These regulatory hubs frequently regulate master regulators of pluripotency such as OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, and are often enriched near oncogenes in tumor cells [20]. Single-cell assays have revealed that enhancer activity is highly dynamic during development, with the enhancer landscape being reshaped at each differentiation step through creation of new enhancers and the closing and reopening of pre-existing elements [20].

Diagram 1: Enhancer states transition during development (76 characters)

Enhancer- Promoter Interactions in Development

The relationship between enhancer-promoter (E-P) proximity and transcriptional activity varies significantly across developmental stages [22]. During cell-fate specification, E-P interactions frequently operate in a permissive mode, with preformed chromatin loops establishing proximity hours before gene activation [22]. These permissive topologies maintain surprisingly similar architectures between different lineages (e.g., myogenic and neuronal cells) despite divergent transcriptional programs, suggesting a basal regulatory framework that precedes lineage commitment [22].

In contrast, during terminal tissue differentiation, E-P interactions transition to an instructive mode, where changes in spatial proximity directly correlate with changes in transcriptional activity [22]. This developmental stage exhibits a dramatic increase in both the number and complexity of E-P interactions, with many new distal interactions emerging specifically in differentiated tissues [22]. The shift from permissive to instructive regulation may enable developmental plasticity during early cell-fate decisions while ensuring precise transcriptional control during terminal differentiation.

The mechanistic basis for these differential interaction modes involves distinct transcription factor complexes. Permissive interactions often involve ubiquitously expressed factors like CTCF/cohesin, while instructive interactions typically require lineage-specific transcription factors that emerge during terminal differentiation [22]. This model is supported by Capture-C studies in Drosophila embryos showing that the number of high-confidence E/P interactions increases substantially during development, from approximately 1,000-3,000 during specification stages to 3,000-9,000 during differentiation stages [22].

Experimental Methods for Enhancer Characterization

Chromatin-Based Enhancer Identification

Chromatin-based approaches provide powerful tools for genome-wide enhancer identification [23]. Single-cell ATAC-Seq enables identification of thousands of potential enhancers with cell-type specific resolution by mapping regions of accessible chromatin [23]. Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-Seq) targets histone modifications such as H3K4me1 (primed enhancers), H3K27ac (active enhancers), or H3K27me3 (poised enhancers) to map enhancer locations and states [20] [21]. Additionally, chromosome conformation capture assays (Hi-C, Capture-C) identify enhancers that engage in 3D chromatin interactions with putative target genes, providing functional context for distal regulatory elements [23] [22].

Functional Enhancer Validation

Reporter Assays

Reporter assays represent the gold standard for functional enhancer validation [23]. In these assays, putative enhancer sequences are cloned downstream of a minimal promoter driving expression of a reporter gene (e.g., lacZ, luciferase, GFP) [23]. Spatial activity patterns during development can be visualized in transgenic embryos using imaging-based approaches, providing high-resolution spatiotemporal characterization of enhancer function [23]. The VISTA Enhancer Browser documents thousands of enhancers experimentally validated using reporter assays in embryonic mice, offering a valuable resource for developmental enhancer annotation [23].

Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRAs)

MPRAs utilize next-generation sequencing to measure enhancer activity at scale [23]. In these approaches, thousands of DNA sequences are cloned into reporter constructs upstream of a minimal promoter, fluorescent marker, and barcode [23]. By sequencing the barcodes and measuring their abundance, the expression level driven by each enhancer can be quantitatively determined [23]. Recent adaptations combine MPRAs with single-cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-seq) to characterize enhancer activity in heterogeneous cell systems, enabling simultaneous mapping of enhancer function and cellular identity [23].

CRISPR-Based Screening

CRISPR-based approaches enable functional characterization of enhancers in their native genomic context [23]. CRISPR inhibition (CRISPRi) and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) systems target transcriptional repressors or activators to specific enhancer sequences, allowing researchers to assess the functional consequences of enhancer perturbation [23]. When coupled with single-cell readouts, these technologies enable high-resolution functional mapping of enhancer networks during development and disease [23].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Enhancer Characterization

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| scATAC-Seq | Maps accessible chromatin regions | High | Identification of putative enhancers with cell-type resolution |

| ChIP-Seq | Identifies histone modifications or TF binding sites | Medium-High | Mapping enhancer states (primed, active, poised) |

| Reporter Assays | Tests enhancer activity on minimal promoter | Low | Functional validation of spatiotemporal activity |

| MPRA | Quantifies activity of thousands of sequences | Very High | High-throughput enhancer screening |

| CRISPR Screening | Perturbs enhancers in native context | Medium-High | Functional validation and target gene identification |

| Capture-C | Maps chromatin interactions | Medium | Linking enhancers to target promoters |

Single-Cell Bisulfite Sequencing and VMR Detection

scBS Data Analysis Challenges

Single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS) provides assessment of DNA methylation at single-base pair and single-cell resolution, enabling identification of methylation heterogeneity within complex tissues [4]. However, analysis of scBS data presents significant challenges due to sparse coverage (typically 5-20% of CpGs per cell), binary nature of methylation calls, and the absence of natural feature boundaries for quantification [4]. Standard analytical approaches divide the genome into large tiles (e.g., 100 kb) and calculate average methylation within each tile, but this coarse-graining approach can lead to signal dilution and poor discrimination of cell types [4].

Advanced VMR Detection Methodology

Read-Position-Aware Quantitation

MethSCAn, a comprehensive software toolkit for scBS data analysis, implements improved strategies for VMR detection that address limitations of simple averaging approaches [4]. The read-position-aware quantitation method first obtains a smoothed ensemble average of methylation across all cells for each CpG position using kernel smoothing (typically 1,000 bp bandwidth), then quantifies each cell's deviation from this average as signed residuals [4]. For each genomic region, the shrunken mean of residuals across all covered CpGs provides a more accurate quantification of relative methylation that accounts for positional effects and reduces technical variation [4].

Identification of Variably Methylated Regions

VMRs represent genomic intervals showing variable methylation patterns across cells and are particularly valuable for distinguishing cell types or states [4]. Not all genomic regions are equally informative for this purpose—housekeeping gene promoters typically remain unmethylated while CpG-rich regions show consistently high methylation regardless of cell type [4]. In contrast, enhancers often exhibit dynamic methylation patterns that correlate with their regulatory activity, making them prime candidates for VMR detection [21]. MethSCAn implements specialized algorithms to identify these informative regions before quantification, significantly improving signal-to-noise ratio in downstream analyses [4].

Diagram 2: VMR detection workflow from scBS data (65 characters)

Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering

Following VMR quantification, the resulting matrix (cells × VMRs) undergoes dimensionality reduction to enable visualization and clustering [4] [24]. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is commonly applied to the methylation matrix, with the top components (typically 20-50) capturing biological variance while averaging out technical noise [4] [24]. The PCA representation then serves as input for nonlinear dimensionality reduction techniques such as t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) or Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), which provide two-dimensional visualizations of cellular relationships based on methylation patterns [4] [24]. This analytical pipeline enables identification of distinct cell populations, trajectory inference, and correlation of methylation states with cellular phenotypes.

Machine Learning Approaches for Epigenomic Analysis

Dimensionality Reduction Strategies

The high-dimensional nature of epigenomic data (typically >>10,000 features) necessitates effective dimensionality reduction before modeling [24]. Feature extraction methods transform original data to lower dimensions while preserving information, with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) providing computationally efficient linear transformation, t-SNE capturing local nonlinear patterns, and UMAP offering fast manifold learning with preservation of global structure [24]. Feature selection algorithms directly identify informative features, with Correlation-based Feature Selection (CFS) ranking features by class correlation, Information Gain evaluating feature relevance via mutual information, and ReliefF identifying attributes that distinguish nearest neighbors of different classes [24].

Supervised and Deep Learning Applications

Machine learning enables prediction of disease markers, gene expression, enhancer-promoter interactions, and chromatin states from epigenomic data [25]. Conventional supervised methods including Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests, and gradient boosting have been employed for classification and feature selection across thousands of CpG sites [24] [11]. Deep learning approaches such multilayer perceptrons and convolutional neural networks capture nonlinear interactions between CpGs and genomic context for tasks including tumor subtyping, tissue-of-origin classification, and survival risk evaluation [11]. Recently, transformer-based foundation models (MethylGPT, CpGPT) pretrained on large methylome datasets (≥150,000 human methylomes) have demonstrated robust cross-cohort generalization and contextually aware CpG embeddings [11].

Table 3: Machine Learning Applications in Epigenomics

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Epigenomics Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensionality Reduction | PCA, t-SNE, UMAP | Visualization of methylation landscapes, identification of sample clusters |

| Feature Selection | CFS, Information Gain, ReliefF | Identification of diagnostic CpG markers, reduction of feature space |

| Supervised Learning | SVM, Random Forest, Logistic Regression | Disease classification, cancer subtyping, age prediction |

| Deep Learning | CNN, MLP, Transformer models | Enhancer-promoter interaction prediction, chromatin state annotation |

| Foundation Models | MethylGPT, CpGPT | Cross-cohort generalization, context-aware embedding |

Enhanceropathies: Enhancer Dysregulation in Disease

Enhancer disruption represents an important mechanism in developmental diseases, with non-coding variants at enhancers contributing extensively to disease risk [23]. Well-characterized enhanceropathies include point mutations in a distal sonic hedgehog (SHH) enhancer located over 1 Mb away from its target promoter that cause preaxial polydactyly [23]. Similarly, congenital heart defects (CHD) can result from genetic variants that ablate TBX5 enhancer activity, phenocopying TBX5 haploinsufficiency caused by coding mutations [23]. These examples illustrate how enhanceropathies can mimic the effects of protein-coding mutations while involving completely different genomic mechanisms.

Enhancer dysregulation also contributes to cancer pathogenesis through multiple mechanisms. Super-enhancers are frequently enriched near oncogenes in tumor cells, and genome-wide association studies have identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at enhancers associated with several common diseases [20]. Specific examples include distinct regulatory signatures of fusion proteins (RUNX1-ETO, RUNX1-EV1) in myeloid leukemia that display unique binding patterns and interact with different transcription factors to alter the epigenome [20]. Similarly, MLL-Af9 and MLL-AF4 oncofusion proteins show distinct enhancer binding patterns in 11q23 acute myeloid leukemia, targeting the RUNX1 program [20].

The clinical translation of enhancer research is advancing through DNA methylation-based classifiers that standardize diagnoses across disease subtypes. For central nervous system cancers, methylation classifiers have altered histopathologic diagnosis in approximately 12% of prospective cases and are accompanied by online portals facilitating routine pathology application [11]. In rare diseases, genome-wide episignature analysis correlates patient blood methylation profiles with disease-specific signatures, demonstrating clinical utility in genetic workflows [11]. Liquid biopsy approaches combining targeted methylation assays with machine learning enable early cancer detection from plasma cell-free DNA with excellent specificity and accurate tissue-of-origin prediction [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Enhancer and VMR Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| MethSCAn | Software toolkit for scBS data analysis | Identification of VMRs, dimensionality reduction, differential methylation analysis [4] |

| Illumina Infinium BeadChip | Methylation microarray platform | Cost-effective methylation profiling of predefined CpG sites [11] |

| VISTA Enhancer Browser | Database of validated enhancers | Reference for spatiotemporal enhancer activity in embryonic development [23] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Genome editing | Functional validation of enhancers through perturbation in native context [23] |

| p300/CBP Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of enhancer regions | Identification of active enhancer elements [21] |

| scATAC-Seq Kits | Single-cell chromatin accessibility profiling | Identification of putative enhancers with cell-type resolution [23] |

| MPRA Libraries | Massively parallel reporter assays | High-throughput functional screening of enhancer sequences [23] |

| Ned-K | Ned-K, MF:C31H31N5O3, MW:521.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ATTO488-ProTx-II | ATTO488-ProTx-II is a fluorescently labeled, high-affinity blocker for Nav1.7 channels. This product is for research use only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic applications. |

Enhancer biology represents a rapidly advancing field with significant implications for understanding development and disease. The integration of single-cell bisulfite sequencing with advanced computational methods for VMR detection provides powerful approaches for mapping the epigenetic heterogeneity of enhancer elements across cell types and states. As machine learning algorithms continue to evolve, particularly through foundation models pretrained on large epigenomic datasets, we anticipate enhanced ability to predict enhancer function, identify pathogenic non-coding variants, and develop targeted epigenetic therapies.

Future challenges include the development of improved experimental methods for simultaneous profiling of multiple epigenetic modalities in single cells, computational techniques for integrating epigenomic data across spatial and temporal dimensions, and clinical translation of enhancer-based diagnostics and therapeutics. By combining rigorous experimental characterization of enhancer elements with advanced computational analysis of methylation patterns, researchers can continue to unravel the complex regulatory logic underlying development, disease, and cellular responses to environmental signals.

For decades, DNA methylation analysis relied on bulk sequencing approaches that profiled populations of cells, providing an average methylation level that masked cell-to-cell variation. The emergence of single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS-seq) and related technologies has revolutionized the field by enabling the detection of epigenetic heterogeneity within complex tissues and rare cell populations [26] [27]. This paradigm shift is particularly crucial for identifying variably methylated regions (VMRs)—genomic regions where methylation patterns differ between individual cells, serving as potential markers of cellular identity, stochastic epigenetic variation, and dynamic regulatory processes [3]. While bulk sequencing methods like whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) provide comprehensive coverage or cost-effective targeted analysis, they cannot resolve the cellular diversity that underlies development, disease progression, and treatment response [27] [28]. The move to single-cell resolution has therefore transformed our understanding of epigenetic regulation, revealing new insights into cellular diversity in complex systems including cancer, brain tissue, and embryonic development [26] [29].

Technological Evolution: From Bulk to Single-Cell Resolution

Foundational Bulk Methylation Sequencing Methods

Traditional DNA methylation analysis methods provided the foundation for current single-cell approaches. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) remains the gold standard for bulk analysis, offering single-base resolution methylation measurements across the entire genome [30] [28]. In this method, genomic DNA is treated with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines after sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain protected from conversion [28]. The main limitations of WGBS include high sequencing costs, significant DNA degradation during bisulfite treatment (up to 90% loss), and reduced sequence complexity that complicates alignment [28]. Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) was developed to provide a more cost-effective alternative by using restriction enzymes to enrich for CpG-rich regions, covering approximately 10-15% of all CpGs but capturing most CpG islands and promoters [27] [28]. While both methods generate valuable data, they inherently average methylation signals across thousands to millions of cells, obscuring cell-to-cell heterogeneity [27].

Breakthrough Single-Cell Methylation Technologies

The development of scBS-seq in 2014 marked a critical turning point in epigenetic analysis [26]. This method adapted post-bisulfite adapter tagging (PBAT) for single cells, performing bisulfite treatment first to simultaneously fragment and convert DNA, followed by adapter ligation and amplification [26] [9]. This technical innovation enabled genome-wide methylation profiling from individual cells, revealing previously hidden epigenetic heterogeneity. Initial applications demonstrated that scBS-seq could accurately measure DNA methylation at up to 48.4% of CpGs in single mouse oocytes and embryonic stem cells (ESCs), revealing distinct "2i-like" cell subpopulations within serum-cultured ESCs [26].

Subsequent methodological advances have addressed limitations in coverage, throughput, and multimodal integration:

- scRRBS (single-cell reduced representation bisulfite sequencing) applies RRBS principles to single cells, providing targeted coverage of CpG-rich regions with reduced sequencing costs [27] [28].

- sciMET (single-cell combinatorial indexing for methylation analysis) uses iterative indexing to exponentially increase throughput while reducing costs per cell, enabling atlas-scale studies [29].

- scDEEP-mC (single-cell deep and efficient epigenomic profiling of methyl-C) represents a recent improvement in scWGBS, offering high-coverage libraries that cover ~30% of CpGs at moderate sequencing depths (20 million reads/cell) through optimized random primer design and library construction [9].

- scEpi2-seq enables multi-omic detection of both DNA methylation and histone modifications in the same single cell, revealing how these epigenetic layers interact [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Cell DNA Methylation Sequencing Technologies

| Technology | Coverage | Resolution | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scBS-seq [26] | ~48% of CpGs (saturation) | Single-base | Embryonic stem cell heterogeneity, oocyte methylation | Lower mapping efficiency (~25%), technical noise |

| scRRBS [27] [28] | ~10-15% of CpGs (CpG-rich regions) | Single-base | Cancer epigenetics, biomarker discovery | Biased toward CpG islands, misses regulatory elements |

| sciMET [29] | Varies with indexing | 100kb windows recommended | Brain cell atlas, glial cell identification | Computational challenges with large datasets |

| scDEEP-mC [9] | ~30% of CpGs (at 20M reads) | Single-base | Cell lineage tracing, replication dynamics | Protocol complexity, higher cost |

| scEpi2-seq [31] | >50,000 CpGs/cell + histone marks | Single-molecule | Epigenetic interaction dynamics, cell cycle influence | Antibody dependency, complex data integration |

Analytical Challenges and Computational Solutions for scBS-seq Data

Navigating Data Sparsity and Technical Noise

Single-cell methylation data presents unique analytical challenges distinct from bulk sequencing. The most significant issue is extreme sparsity, with typically 80-95% of CpG sites remaining unobserved in individual cells due to limited genomic DNA and the destructive nature of bisulfite treatment [3]. This sparsity is compounded by technical noise from amplification biases, bisulfite conversion inefficiencies, and sequencing errors [3] [9]. Additionally, allelic dropout and coverage bias can create false patterns of methylation heterogeneity if not properly accounted for in analytical workflows [9].

A critical step in scBS-seq analysis is quality control and filtering. Cells with low numbers of unique cut sites or abnormal methylation levels should be identified and removed. For example, in scEpi2-seq experiments, approximately 35-40% of cells typically pass quality thresholds, with exclusions based on read counts, fraction of reads in peaks (FRiP), and average methylation levels [31]. Conversion efficiency must also be rigorously monitored, with most protocols achieving >97% bisulfite conversion rates as measured by non-CpG methylation in contexts where it is biologically rare [26] [9].

Computational Tools for VMR Detection

Identifying variably methylated regions (VMRs)—genomic regions with cell-to-cell methylation differences—is a primary objective in scBS-seq analysis. Several computational approaches have been developed specifically for this purpose:

vmrseq is a probabilistic method that detects VMRs without predefining genomic regions [3]. It employs a two-stage approach: first constructing candidate regions by smoothing methylation data and identifying loci with high cross-cell variance, then applying a hidden Markov model (HMM) to precisely determine VMR boundaries and methylation states. This method outperforms sliding-window approaches in accuracy and feature selection for downstream analyses [3].

Amethyst is a comprehensive R package designed for atlas-scale single-cell methylation data [29]. It efficiently processes data from hundreds of thousands of cells by calculating methylation levels over feature sets (e.g., 100kb genomic windows), performing dimensionality reduction, clustering, and differential methylation analysis. Benchmark studies show Amethyst performs comparably or faster than existing single-cell methylation packages while offering enhanced visualization capabilities [29].

MethSCAn focuses specifically on VMR and differentially methylated region (DMR) identification, though it requires computationally expensive preparation steps [29].

scMET employs a hierarchical Bayesian model to capture cell-to-cell heterogeneity and select features through heterogeneity ranking [3].

Table 2: Computational Tools for Single-Cell Methylation Analysis

| Tool | Methodology | Primary Function | Strengths | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| vmrseq [3] | Hidden Markov Model | VMR detection | Base-pair resolution, no predefined regions | R |

| Amethyst [29] | Dimensionality reduction | End-to-end analysis | Handles large datasets, comprehensive workflow | R |

| MethSCAn [29] | Statistical testing | VMR/DMR identification | Fast DMR testing | Multiple |

| scMET [3] | Bayesian hierarchical model | Feature selection | Models overdispersion, handles sparsity | R |

| ALLCools [29] | Feature aggregation | Multi-modal analysis | Integration with snmC-seq data | Python |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental and computational workflow for single-cell DNA methylation analysis, from cell isolation through biological interpretation:

Successful single-cell methylation analysis requires specialized reagents and computational resources. The following table details essential components of the experimental workflow:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for scBS-seq

| Category | Specific Reagents/Resources | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Isolation | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [31] [27] | High-throughput single-cell sorting | Preserves cell viability, enables marker-based selection |

| Microfluidic platforms (10X Genomics) [27] | Automated single-cell partitioning | Integrated barcoding, high throughput | |

| Bisulfite Conversion | Sodium bisulfite conversion buffer [9] | Chemical conversion of unmethylated C to U | Optimization needed to minimize DNA degradation |

| Methylated/unmethylated spike-in controls [31] | Conversion efficiency monitoring | Essential for quality control | |

| Library Preparation | Protein A-micrococcal nuclease (pA-MNase) [31] | Targeted chromatin profiling | Used in multi-omics approaches like scEpi2-seq |

| TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS) reagents [31] | Bisulfite-free methylation detection | Alternative to bisulfite with less DNA damage | |

| Tagged random nonamers (scDEEP-mC) [9] | Efficient primer design for bisulfite-converted DNA | Base composition optimized for converted genome | |

| Computational Resources | High-performance computing cluster [29] | Data processing and analysis | Essential for large-scale studies |

| R/Bioconductor packages (Amethyst, vmrseq) [3] [29] | Specialized statistical analysis | Rich ecosystem for single-cell analysis |

Research Applications and Biological Insights

Characterizing Cellular Heterogeneity in Development and Disease

Single-cell methylation analysis has revealed unprecedented insights into cellular heterogeneity during development. In embryonic stem cells (ESCs), scBS-seq uncovered distinct epigenetic states within seemingly homogeneous cultures, identifying "2i-like" cells in serum cultures that exhibited global hypomethylation similar to ESCs grown in 2i conditions [26]. These findings demonstrated that DNA methylation heterogeneity serves as a key regulator of pluripotency states. In brain development, single-cell methylation profiling has revealed cell-type-specific patterns of non-CG methylation (mCH) in human astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, challenging the previous notion that this form of methylation was primarily relevant to neurons [29]. These glial mCH patterns accumulate across neuronal genes in a manner anticorrelated with expression and show similar trinucleotide context preferences to neuronal mCH [29].

In cancer research, single-cell methylation analysis has uncovered epigenetic heterogeneity within tumors that may drive treatment resistance and disease progression. The technology enables identification of rare cell populations, such as cancer stem cells, that are masked in bulk analyses but may have critical clinical implications [27]. Furthermore, integration with other single-cell modalities has revealed how DNA methylation interacts with histone modifications to establish stable epigenetic states in cancer cells [31].

Multi-Omic Integration and Machine Learning Approaches

The integration of scBS-seq with other single-cell modalities represents the cutting edge of epigenetic analysis. Methods like scEpi2-seq simultaneously profile DNA methylation and histone modifications (H3K9me3, H3K27me3, H3K36me3) in the same single cell [31]. This multi-omic approach has revealed how DNA methylation maintenance is influenced by local chromatin context during the cell cycle and how H3K27me3 and DNA methylation interact during cell type specification in the mouse intestine [31].

Machine learning approaches are increasingly being applied to single-cell methylation data to enhance pattern recognition and prediction. vmrseq uses probabilistic modeling to detect VMRs with greater accuracy than sliding-window approaches [3]. More recently, transformer-based foundation models like MethylGPT and CpGPT have been pretrained on large methylome datasets (over 150,000 human methylomes) to support imputation and prediction tasks with attention to regulatory regions [30]. These models demonstrate robust cross-cohort generalization and produce contextually aware CpG embeddings that transfer efficiently to age and disease-related outcomes [30].

Analytical Pipeline Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow for identifying biologically relevant patterns from single-cell methylation data, specifically focusing on VMR detection and cell type identification:

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The field of single-cell DNA methylation analysis continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future trajectory. Multi-omic integration is advancing beyond parallel measurements to truly integrated analyses that reveal how epigenetic layers interact dynamically in individual cells [31]. Spatial methylation profiling approaches are being developed to combine single-cell resolution with tissue context preservation, bridging a critical gap in our understanding of epigenetic regulation in tissue microenvironments [27]. As methods like scDEEP-mC [9] and combinatorial indexing strategies [29] improve coverage and throughput, single-cell methylation analysis will become increasingly accessible for studying large, complex tissues and clinical samples.

Computational innovations will be equally important for unlocking the full potential of single-cell methylation data. Machine learning approaches, particularly deep learning models trained on large-scale methylation datasets, show promise for imputing missing data, identifying subtle patterns of variation, and predicting functional outcomes [30]. The development of comprehensive analytical frameworks like Amethyst [29] and vmrseq [3] will make sophisticated analyses accessible to a broader range of researchers, accelerating discoveries across diverse biological contexts.