Mastering ChIP-seq: A Comprehensive Guide to H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3 Epigenetic Analysis

ChIP-seq is a cornerstone technique for profiling histone modifications like H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3, which play pivotal roles in gene regulation, cellular identity, and disease.

Mastering ChIP-seq: A Comprehensive Guide to H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3 Epigenetic Analysis

Abstract

ChIP-seq is a cornerstone technique for profiling histone modifications like H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3, which play pivotal roles in gene regulation, cellular identity, and disease. This article delivers a thorough resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, encompassing foundational insights into these marks' biological functions, step-by-step methodological protocols, practical troubleshooting for common challenges, and rigorous validation through comparative omics integration. By addressing current advancements and applications, it empowers robust epigenetic investigations in biomedicine and therapeutic discovery.

Unlocking Epigenetic Code: The Essential Roles of H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3 in Gene Regulation

The Histone Code and Core Mechanisms

The fundamental unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, consisting of 147 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of core histone proteins: two copies each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 [1]. Histone modifications are post-translational alterations to these histone proteins that constitute a sophisticated "histone code" capable of dictating the transcriptional state of local genomic regions without changing the underlying DNA sequence [1] [2]. These modifications play critical roles in cell fate determination, development, and disease by regulating access to DNA for transcriptional machinery [2] [3].

Chromatin architecture exists in two primary states governed by histone modifications. Euchromatin represents an open, transcriptionally active conformation where modifications disrupt histone-DNA interactions, allowing transcriptional machinery to access DNA [1]. In contrast, heterochromatin forms a tightly packed, transcriptionally silent structure where modifications strengthen histone-DNA interactions, preventing DNA access [1]. The dynamic interconversion between these states enables precise spatial and temporal control of gene expression.

At least nine distinct types of histone modifications have been identified [1]. Acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitylation represent the most thoroughly characterized modifications, while newer discoveries including GlcNAcylation, citrullination, crotonylation, and isomerization remain under active investigation [1]. Each modification is added or removed from specific histone amino acid residues by dedicated enzymatic machinery [1] [2].

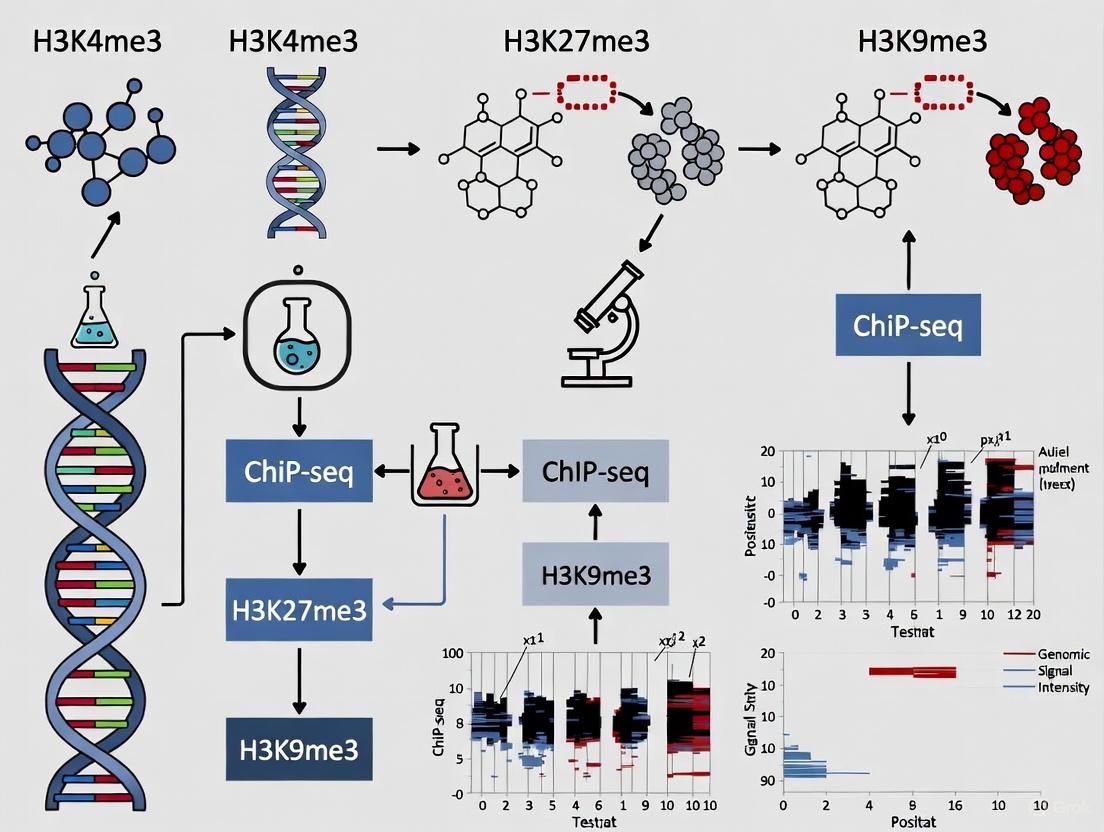

Figure 1: Fundamental Mechanism of Histone Modifications in Chromatin Regulation

Major Histone Modifications and Their Functions

Histone Acetylation

Histone acetylation, one of the most extensively studied modifications, involves the addition of acetyl groups to lysine residues on histones H3 and H4 by histone acetyltransferases (HATs), with removal mediated by histone deacetylases (HDACs) [1]. This modification neutralizes the positive charge on lysine residues, weakening histone-DNA interactions and significantly increasing gene expression [1]. Acetylation is involved in cell cycle regulation, proliferation, apoptosis, cellular differentiation, DNA replication and repair, nuclear import, and neuronal repression [1]. An imbalance in histone acetylation equilibrium is strongly associated with tumorigenesis and cancer progression [1] [2].

Prominent examples include H3K9ac and H3K27ac, which typically mark enhancers and promoters of active genes [1]. The dynamic nature of histone acetylation makes it one of the fastest post-translational modifications, faster than methylation but slower than phosphorylation [2]. Overexpression and enhanced activity of HDACs have been identified as drivers of tumor development and metastasis, leading to the development of HDAC inhibitors approved for cancer treatment [2].

Histone Methylation

Histone methylation occurs on lysine or arginine residues of histones H3 and H4, with divergent impacts on transcription [1]. Arginine methylation generally promotes transcriptional activation, while lysine methylation can either activate or repress transcription depending on the specific site [1]. Lysines can be mono-, di-, or tri-methylated, adding considerable functional diversity [1]. This modification differs from acetylation in that it does not alter histone charge or directly impact histone-DNA interactions [1].

Methylation is considered a relatively stable mark that can be propagated through multiple cell divisions, though it is now recognized as actively reversible through demethylase activity [1]. Mutations in histone methyltransferases and demethylases are frequently observed in cancer cells, resulting in altered chromatin methylation patterns that drive tumor development and metastasis [2].

Additional Histone Modifications

Histone phosphorylation adds negative charge primarily to serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues on histone tails, serving as a critical intermediate step in chromosome condensation during cell division, transcriptional regulation, and DNA damage repair [1]. Unlike acetylation and methylation, phosphorylation often establishes interactions between other histone modifications and serves as a platform for effector proteins [1]. For example, phosphorylation of H3S10 and H3S28 plays important roles in chromatin compaction and regulation during mitosis [1].

Histone ubiquitylation can occur on all core histones, though H2A and H2B are most commonly modified [1]. This modification plays a central role in the DNA damage response, with monoubiquitylated H2A associated with gene silencing and H2B with transcription activation [1]. Histone ubiquitylation also participates in crosstalk with other modifications; for instance, ubiquitination of H2B is a prerequisite for methylation of H3K4 and H3K79 [2].

Table 1: Major Histone Modifications and Their Functional Roles

| Histone Modification | Function | Genomic Location | Catalytic Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Transcriptional activation | Promoters, bivalent domains | SET1/MLL complexes (Writers); KDM5 family (Erasers) [4] |

| H3K27me3 | Transcriptional repression | Promoters in gene-rich regions, developmental regulators | EZH1/EZH2 (Writers); KDM6 family (Erasers) [1] [2] |

| H3K9me3 | Permanent heterochromatin formation | Satellite repeats, telomeres, pericentromeres | SUV39H1/2, SETDB1 (Writers); KDM4 family (Erasers) [1] [3] |

| H3K27ac | Transcriptional activation | Enhancers, promoters | p300/CBP (Writers); HDAC1-3 (Erasers) [1] [3] |

| H3K9ac | Transcriptional activation | Enhancers, promoters | GCN5/PCAF (Writers); HDAC1-3 (Erasers) [1] |

| H3K36me3 | Transcriptional activation | Gene bodies | SETD2 (Writer); KDM2/4 families (Erasers) [1] [3] |

| γH2A.X | DNA damage response | DNA double-strand breaks | ATM/ATR kinases (Writers); phosphatases (Erasers) [1] |

Key Histone Modifications in Experimental Research

H3K4me3: A Prime Activation Mark

H3K4me3 represents one of the most studied histone modifications due to its enrichment at transcription start sites and association with active gene expression [4]. This mark plays critical roles in regulating specific phases of transcription, including RNA polymerase II initiation, pause-release, heterogeneity, and consistency [4]. The protein complexes catalyzing mono-, di-, and trimethylation of H3K4, along with their corresponding demethylases and reader proteins, are essential for differentiation and development [4].

Recent studies have revealed that the roles of H3K4me3 in gene expression may differ from original assumptions, with precise regulation proving essential for normal development and disease prevention [4]. Somatic alterations in genes regulating H3K4 methylation are common in cancer, highlighting its therapeutic relevance [4]. In experimental contexts, H3K4me3 typically displays a narrow peak distribution pattern at transcriptional start sites [5].

H3K27me3: A Repressive Mark with Developmental Significance

H3K27me3 functions as a repressive histone modification that serves as a temporary signal at promoter regions to control developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells [1]. This modification is catalyzed by EZH2 within the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) and is frequently dysregulated in cancer [2]. H3K27me3 works in concert with H2AK119ub to establish facultative heterochromatin, particularly at intergenic and silenced coding regions [1] [2].

The dynamic nature of H3K27me3 makes it particularly important during development and cellular differentiation. In experimental profiling, H3K27me3 often displays broad chromosomal domains rather than sharp peaks, presenting distinct analytical challenges [5].

H3K9me3: A Marker of Constitutive Heterochromatin

H3K9me3 represents a more permanent signal for heterochromatin formation in gene-poor chromosomal regions with tandem repeat structures, including satellite repeats, telomeres, and pericentromeres [1]. This modification creates binding sites for HP1 family proteins, which facilitate the formation of higher-order heterochromatin architecture [2]. H3K9me3 also marks retrotransposons and specific families of zinc finger genes [1].

Unlike H3K27me3, H3K9me3 is generally associated with stable, long-term gene silencing. In certain contexts, H3K9me3 can form bivalent chromatin domains with H3K4me3 to maintain adipogenic master regulatory genes expressed at low levels yet poised for activation when differentiation is required [6].

Table 2: Characteristics of Key Histone Modifications in ChIP-seq Analysis

| Modification | Peak Type | Recommended Sequencing Depth | Typical Antibody Target | Biological Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Narrow peak | 10-20 million reads [5] | C-terminal region of H3 [7] | Active promoters, developmental poised promoters |

| H3K27me3 | Broad peak | 10-45 million reads [5] | Residues 25-44 of H3 [8] | Facultative heterochromatin, developmental gene silencing |

| H3K9me3 | Broad peak | 10-45 million reads [5] | N-terminal tail of H3 [6] | Constitutive heterochromatin, repetitive elements |

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq) Methodology

Fundamental Principles of ChIP-seq

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) represents a powerful antibody-based technology that enables selective enrichment of specific DNA-binding proteins and their genomic targets [9]. This method provides critical information about chromatin state and gene transcription by combining protein analysis with molecular biology techniques [9]. ChIP-seq offers higher resolution, reduced noise, and greater coverage compared to earlier technologies like ChIP-chip [5].

The core principle involves using antibodies that selectively detect and bind to target proteins, including histones, histone modifications, transcription factors, and cofactors, along with their associated DNA fragments [9]. These immunoprecipitated DNA fragments are then sequenced and mapped to a reference genome to identify the protein or modification's genomic location and abundance [1] [9].

Experimental Workflow and Technical Considerations

The standard ChIP-seq protocol consists of several critical steps. First, protein-DNA crosslinking using formaldehyde-based reagents stabilizes protein-DNA interactions for subsequent analysis [9]. Next, chromatin fragmentation through enzymatic digestion (using micrococcal nuclease) or sonication breaks chromatin into appropriate-sized fragments [9]. Immunoprecipitation with specific antibodies then enriches for target protein-DNA complexes, followed by DNA purification and library preparation for next-generation sequencing [9] [7].

Two primary ChIP approaches exist: Native ChIP (N-ChIP) uses non-crosslinked chromatin and works optimally for histone modifications, while Crosslinked ChIP (X-ChIP) employs formaldehyde fixation and can capture both histone and non-histone protein interactions [9]. N-ChIP offers better antibody affinity but is restricted to stable interactions like histone-DNA binding, while X-ChIP can capture transient interactions but requires more optimization [9].

Figure 2: Standard ChIP-seq Experimental Workflow

Critical Success Factors in ChIP-seq

Antibody quality represents the most crucial factor in ChIP-seq success, as the technique relies entirely on antibody specificity and affinity for target epitopes [5]. Antibodies must be rigorously validated for ChIP applications, with Western blot analysis of knock-down samples providing helpful validation data [5]. Chromatin fragmentation quality significantly impacts resolution and success, with ideal fragment sizes ranging from 200-1000 base pairs [9].

Appropriate sequencing depth varies by target, with transcription factors requiring 10-20 million reads and broad histone marks needing 10-45 million reads for comprehensive coverage [5]. Proper experimental controls, including input DNA and appropriate negative controls, are essential for distinguishing true signal from background [9] [5].

Advanced Technologies and Applications

Emerging Methodologies: CUT&Tag

CUT&Tag (Cleavage Under Targets & Tagmentation) represents an emerging enzyme-tethering approach that offers a streamlined, easily scalable, and cost-effective alternative to ChIP-seq [8]. This method uses permeabilized nuclei to allow antibodies to bind chromatin-associated factors, which then tether a protein A-Tn5 transposase fusion protein (pA-Tn5) that cleaves intact DNA and inserts adapters for sequencing [8].

CUT&Tag demonstrates superior signal-to-noise ratio compared to ChIP-seq, with approximately 200-fold reduced cellular input and 10-fold reduced sequencing depth requirements [8]. Recent benchmarking studies show that CUT&Tag recovers approximately 54% of known ENCODE ChIP-seq peaks for histone modifications like H3K27ac and H3K27me3, with the identified peaks representing the strongest ENCODE peaks and showing the same functional and biological enrichments [8].

Multiplexed Approaches

Multiplexed ChIP-seq methodologies like MINUTE-ChIP enable researchers to profile multiple samples against multiple epitopes in a single workflow [10]. This approach dramatically increases throughput while enabling accurate quantitative comparisons [10]. The protocol involves sample preparation with chromatin fragmentation and barcoding of native or formaldehyde-fixed material, followed by pooling and splitting of barcoded chromatin into parallel immunoprecipitation reactions [10].

Multiplexed approaches empower biologists to perform ChIP-seq experiments with appropriate numbers of replicates and control conditions, delivering more statistically robust and biologically meaningful results [10]. These advancements address traditional limitations of ChIP-seq, including laborious parallel experiments, experimental variation, and challenges in quantitative comparison [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Histone Modification Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibodies | H3K4me3: Abcam ab8580; H3K27me3: Cell Signaling 9733; H3K9me3: Active Motif 39783 [8] | Target-specific immunoprecipitation; primary determinant of ChIP success | Must be ChIP-seq grade; validate with knock-down controls [5] [7] |

| Chromatin Preparation Kits | SimpleChIP Plus Sonication Chromatin IP Kit [9] | Standardized cell lysis, chromatin fragmentation & preparation | Ensure compatibility with downstream applications [7] |

| DNA Purification Kits | ChIP DNA Clean & Concentrator kits [7] | Post-IP DNA cleanup and concentration | Remove contaminants while maximizing DNA recovery [7] |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina ChIP-seq Library Prep kits [10] | Sequencing library construction from low-input ChIP DNA | Optimized for low DNA inputs; include unique barcodes for multiplexing [10] |

| Enzymatic Reagents | Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase), Proteinase K, RNase A [9] | Chromatin digestion, protein removal, RNA elimination | Titrate enzymes for optimal activity; ensure complete RNA removal [9] |

Biological Significance and Research Applications

Role in Development and Cellular Differentiation

Histone modifications play indispensable roles in developmental processes and cellular differentiation. During neurogenesis, for example, modifications allow fine-tuning and coordination of spatiotemporal gene expressions as neural stem cells differentiate into specialized brain cell types [3]. Both embryonic and adult neurogenesis are regulated by complex histone modification patterns that determine neural progenitor cell proliferation, fate specification, and differentiation [3].

Bivalent chromatin domains represent particularly important configurations in developmental regulation, initially characterized in embryonic stem cells as regions containing both H3K4me3 (activating) and H3K27me3 (repressing) marks that keep developmental regulatory genes poised for activation [6]. Recent research has revealed alternative bivalent signatures, such as H3K4me3 paired with H3K9me3 in lineage-committed mesenchymal stem cells, which maintain adipogenic master regulatory genes at low expression levels yet primed for activation when differentiation is required [6].

Implications in Disease and Therapeutics

Dysregulation of histone modifications contributes significantly to human diseases, particularly cancer and neurological disorders [2] [3]. In cancer, abnormal alterations in histone modifications affect genome stability and disrupt gene expression patterns, leading to tumor development and metastasis [2]. Mutations within histones or chromatin remodeling complexes represent common features across many tumor types, with histone mutations like H3K27M, H3K36M, and H4G34V/R/W/L frequently occurring in pediatric cancers [2].

Neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric diseases also demonstrate strong connections to histone modification dysregulation [3]. Alterations in H3K27ac have been associated with neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders, including Alzheimer's disease [8]. The reversible nature of histone modifications makes them attractive therapeutic targets, with several HDAC inhibitors and other epigenetic drugs already approved for cancer treatment [2].

The strategic investigation of histone modifications through robust methodologies like ChIP-seq continues to provide critical insights into normal development and disease pathogenesis, offering promising avenues for targeted therapeutic interventions across a spectrum of human disorders.

Trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) represents one of the most extensively studied and evolutionarily conserved epigenetic modifications, serving as a fundamental marker of transcriptionally active promoters across diverse eukaryotic species. This modification is catalyzed by complexes containing H3K4 methyltransferases and dynamically regulated by demethylase enzymes, creating a sophisticated system for transcriptional control [11] [12]. The presence of H3K4me3 at gene promoters facilitates an open chromatin configuration that promotes RNA polymerase II recruitment and activity, thereby enabling and amplifying transcriptional initiation [11]. Beyond its canonical role at promoters, emerging research has revealed that H3K4me3 also operates in intergenic regions, where it participates in regulatory elements and contributes to pervasive transcription throughout mammalian genomes [11] [12]. The precise regulation of H3K4me3 is biologically crucial, as demonstrated by the essential roles of H3K4 methyltransferase and demethylase complexes in cell differentiation, development, and their frequent mutation in various cancers [11].

Within the broader context of histone modification analysis, H3K4me3 represents one pillar of a sophisticated epigenetic regulatory system that includes repressive marks such as H3K27me3 and H3K9me3. While H3K27me3 is associated with facultative heterochromatin and developmental gene repression, and H3K9me3 with constitutive heterochromatin formation, H3K4me3 consistently correlates with active gene expression [13] [14]. This opposing relationship creates a dynamic regulatory balance that controls cellular identity and function. The comprehensive analysis of these modifications through Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has revolutionized our understanding of epigenetic regulation in development, disease, and therapeutic intervention.

Genomic Distribution and Functional Significance

Distinct Genomic Localization Patterns

H3K4me3 exhibits distinct genomic distribution patterns that correlate with specific regulatory functions. At active gene promoters, H3K4me3 is highly enriched around transcription start sites (TSSs), where it interacts directly with transcriptional cofactor TAF3 and chromatin remodelers such as BPTF and CHD1 to facilitate transcription initiation [11] [12]. This promoter-associated H3K4me3 is characterized by sharp, well-defined peaks in ChIP-seq profiles. In contrast, intergenic H3K4me3 is found at a subset of active candidate cis-regulatory elements (acCREs), particularly those marked by both H3K27ac and H3K4me1, suggesting a role in enhancer function [11]. These intergenic regions with H3K4me3 enrichment demonstrate distinct characteristics, including slightly broader peaks, higher H3K4me2 and H3K27ac signals, stronger RNA polymerase II binding, and increased initiating polymerase (Pol II-S5P) compared to H3K4me3-negative regulatory elements [11].

Table 1: Characteristics of H3K4me3 at Different Genomic Locations

| Genomic Location | Peak Characteristics | Associated Markers | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoters | Sharp, defined peaks | High H3K4me3, Pol II binding | Transcription initiation, pause release |

| Intergenic acCREs | Broader peaks | H3K27ac, H3K4me1, H3K4me2 | Enhancer activity, non-coding transcription |

| CpG Island-associated | Unimodal H3K27ac | CpG islands | Recruitment of SET1/MLL complexes |

Transcriptional Regulation Mechanisms

H3K4me3 contributes to transcriptional activation through multiple interconnected mechanisms. The modification directly facilitates RNA polymerase II activity through interactions with transcriptional cofactors and chromatin remodeling complexes [11]. Experimental evidence demonstrates that H3K4me3 is actively involved in both transcription initiation and promoter-proximal pause release, a critical regulatory step in gene expression control [11] [12]. The level of H3K4me3 enrichment shows a strong correlation with the rate of transcription initiation, suggesting a quantitative relationship between this histone modification and transcriptional output [11].

Recent research utilizing epigenetic editing tools has provided causal evidence for H3K4me3 function. Targeted deposition of H3K4me3 at candidate promoters using dCas9-fusion systems was sufficient to increase transcript levels when DNA methylation was low, though it could not overcome hypermethylated states [11] [12]. This highlights the context-dependent nature of H3K4me3 functionality and its interaction with other epigenetic regulators. Interestingly, H3K4me3 appears to amplify transcription at intergenic regulatory elements independently of distance to the nearest gene or physical interaction with promoter regions, suggesting a more general role in supporting transcription throughout the genome [12].

Latest Research Advances and Key Findings

Intergenic H3K4me3 and Transcriptional Amplification

Groundbreaking research published in 2025 has revealed novel functions of H3K4me3 in intergenic regions, fundamentally expanding our understanding of this epigenetic mark. Yu et al. demonstrated that dynamic intergenic deposition of H3K4me3 promotes local transcription at permissive chromatin loci independent of enhancer function or target gene activity [11]. Through systematic, targeted H3K4me3 deposition at intergenic cis-regulatory elements using an epigenetic editing tool (dCas9-PRDM9), the researchers established that H3K4me3 is sufficient to increase transcription at active candidate cis-regulatory elements (cCREs) regardless of genomic position [11] [12]. This effect was unlinked from transcript levels of putative target genes and dependent on chromatin context rather than specific cCRE identity or location.

The study further revealed that H3K4me3 is actively remodeled at intergenic regions under normal conditions. Disruption of demethylase function (RACK7/KDM5C complex) caused significant new H3K4me3 deposition at intergenic sites substantially more than at gene promoters, suggesting continuous removal of this mark from intergenic regions [11]. Surprisingly, depletion of Cfp1 (Cxxc1), a subunit of the SET1 H3K4 trimethyltransferase complex that recruits the complex to unmethylated CpG islands, also resulted in increased intergenic H3K4me3 peaks [11]. This suggests that loss of active promoter recruitment may release the complex to deposit H3K4me3 at intergenic sites, indicating a competitive balance between genic and intergenic H3K4me3 deposition.

Context-Dependent Functionality

The functional outcome of H3K4me3 deposition appears highly dependent on chromatin context and coexisting epigenetic marks. Research indicates that approximately one-fourth of H3K4me3-positive active cis-regulatory elements (acCREs) contain CpG islands, whereas almost no H3K4me3-negative acCREs include annotated CpG islands [11]. This suggests that recruitment of SET1/MLL H3K4 methyltransferase complexes to intergenic CpG islands may bias these sites toward H3K4me3 accumulation by helping overcome active H3K4 demethylation. However, the presence of CpG islands cannot explain H3K4me3 at the majority of intergenic acCREs, indicating additional recruitment mechanisms exist.

The relationship between H3K4me3 and transcriptional activity is influenced by promoter characteristics. Studies from 2010 revealed that the nature of the promoter (viral or endogenous) affects H3K4me3 much more than it affects H3K4me2, suggesting potential fundamental differences in the recruitment of methyltransferases for H3K4 trimethylation [15]. Furthermore, transcriptional activity significantly impacts both the overall level and distribution of H3K4me3 in coding regions, while showing minimal effect on H3K4me2 patterns [15].

Table 2: H3K4me3 Dynamics Under Different Biological Contexts

| Biological Context | H3K4me3 Pattern | Functional Consequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid growth conditions (A. pacificum) | Increased modification abundance under high light/nitrogen | Upregulation of nitrogen metabolism, endocytosis, vitamin metabolism | [16] |

| CpG-methylated DNA regions | H3K4me3 depletion | Transcriptional repression | [15] |

| Demethylase disruption (RACK7/KDM5C) | Increased intergenic deposition | Enhanced local transcription | [11] |

| Cfp1 depletion | Increased intergenic peaks | Altered SET1 complex distribution | [11] |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

ChIP-seq Workflow for H3K4me3 Analysis

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) represents the gold standard technique for genome-wide mapping of H3K4me3 distributions. The standard ChIP-seq protocol begins with cross-linking proteins to DNA using formaldehyde to stabilize protein-DNA interactions, followed by chromatin fragmentation typically through sonication or micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion [17]. While MNase digestion produces uniform mononucleosome-sized fragments ideal for histone modification mapping, sonication is preferred when preserving transcription factor binding sites in linker regions is important [17]. Immunoprecipitation is then performed using specific antibodies against H3K4me3, followed by DNA purification, library preparation, and high-throughput sequencing.

Critical considerations for successful H3K4me3 ChIP-seq include antibody specificity, cross-linking efficiency, and fragmentation optimization. The number of cells used for ChIP is also crucial, with standard protocols requiring 1-10 million cells, though recent advances have enabled histone modification analysis with significantly fewer cells [17]. Proper controls are essential for data interpretation, with input chromatin (non-immunoprecipitated) generally preferred over non-specific IgG controls as it provides better estimation of background biases introduced during chromatin preparation and sequencing [17].

ChIP-seq Workflow for H3K4me3 Profiling

Peak Calling and Data Analysis

Bioinformatic analysis of H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data involves multiple computational steps. Sequence reads are first aligned to a reference genome, followed by peak calling using specialized algorithms. For H3K4me3, which typically produces sharp, well-defined peaks, algorithms such as MACS2 are commonly employed with parameters optimized for histone modification analysis [18] [17]. A standard approach includes peak calling with MACS2 using arguments such as '--BAMPE --q 0.05', followed by quality filtering to retain peaks with q-value scores higher than established thresholds (e.g., 25th percentile) [18].

For comprehensive atlas generation, samples yielding sufficient high-quality peaks (typically >6,000 filtered peaks) can be merged to create a union peak list, with overlapping genomic ranges combined into single features that fully encompass each overlapping peak [18]. This approach enables comparative analysis across multiple experimental conditions or cell types. Advanced analytical methods also consider peak characteristics such as intensity, width, and shape, which can provide insights into the functional state of associated regulatory elements.

Epigenetic Editing Approaches

Beyond observational studies, epigenetic editing tools have emerged as powerful approaches for establishing causal relationships between H3K4me3 and transcriptional outcomes. The development of dCas9-PRDM9 fusion proteins, which combine catalytically dead Cas9 with the catalytic (SET) domain of the H3K4 trimethyltransferase PRDM9, enables targeted deposition of H3K4me3 at specific genomic loci [11] [12]. This approach allows researchers to directly test the functional consequences of H3K4me3 deposition at candidate promoters and enhancers without disturbing other regulatory elements.

Experimental applications of this technology have demonstrated that targeted H3K4me3 deposition can increase transcript levels when DNA methylation is low, but cannot overcome DNA hypermethylated states [11]. This highlights both the potency and limitations of H3K4me3 as a transcriptional activator and underscores the complex interplay between different epigenetic modification systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for H3K4me3 Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 Antibodies | Anti-trimethyl-histone H3 (lys4) from Upstate Biochemical | Chromatin immunoprecipitation; western blot | Specificity validation crucial; different lots may vary |

| ChIP-Seq Kits | Micrococcal nuclease-based kits; sonication-based kits | Chromatin fragmentation for ChIP-seq | MNase preferred for histone modifications; sonication for transcription factors |

| Epigenetic Editing Tools | dCas9-PRDM9 fusion constructs | Targeted H3K4me3 deposition | Enables causal testing of H3K4me3 function |

| Bioinformatic Tools | MACS2, SICER, ChromaBlocks | Peak calling and domain identification | MACS2 optimal for sharp peaks; SICER for broad domains |

| Positive Control Cell Lines | Human breast cancer cell lines (e.g., MCF-7) | Positive controls for H3K4me3 signals | Known H3K4me3 patterns established |

| Demethylase Inhibitors | KDM5C inhibitors | Modulating H3K4me3 levels | Useful for functional studies |

H3K4me3 in Disease and Therapeutic Applications

Role in Disease Pathogenesis

Dysregulation of H3K4me3 patterning contributes significantly to various disease states, particularly cancer. Mutations in H3K4 methyltransferases and demethylases are frequently observed in numerous cancers, highlighting the importance of proper H3K4me3 regulation for maintaining cellular homeostasis [11] [19]. Abnormal H3K4me3 distributions can lead to altered transcriptional programs that drive oncogenic processes, including uncontrolled proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and metabolic reprogramming. Beyond cancer, H3K4me3 dysregulation has been implicated in neurological disorders, developmental abnormalities, and immune dysfunction, establishing it as a broad contributor to human disease.

Research across multiple cancer types has revealed that H3K4me3 profiles can serve as biomarkers for disease classification and prognosis. In tumorigenesis, the redistribution of H3K4me3 occurs in coordination with other epigenetic changes, including alterations in DNA methylation and repressive histone marks [14]. This epigenetic reprogramming can silence tumor suppressor genes or activate oncogenes, contributing to cancer initiation and progression. The context-dependent nature of H3K4me3 function is particularly relevant in disease states, where the cellular environment and coexisting epigenetic marks influence the functional outcomes of H3K4me3 deposition.

Applications in Drug Discovery

ChIP-seq profiling of H3K4me3 has emerged as a valuable tool in pharmaceutical research and development, enabling the identification of novel drug targets and providing insights into drug mechanisms of action [19]. By mapping H3K4me3 patterns in disease versus normal states, researchers can identify key regulatory elements and genes driving pathological processes, which may represent promising therapeutic targets. Additionally, monitoring H3K4me3 changes in response to drug treatment can reveal epigenetic mechanisms contributing to therapeutic efficacy or resistance.

The application of ChIP-seq in drug discovery has already contributed to notable successes, particularly in oncology [19]. For instance, H3K4me3 profiling has helped identify oncogenic transcription factors and their target genes in various cancers, leading to the development of targeted therapies that disrupt these regulatory networks. Furthermore, characterizing H3K4me3 patterns in drug-resistant versus sensitive cells has provided insights into epigenetic mechanisms underlying treatment failure, suggesting strategies to overcome resistance through combination therapies targeting multiple epigenetic pathways.

Therapeutic Applications of H3K4me3 Research

Comparative Analysis with Other Histone Modifications

Understanding H3K4me3 within the broader epigenetic landscape requires comparison with other key histone modifications, particularly H3K27me3 and H3K9me3. While H3K4me3 is unequivocally associated with transcriptional activation, H3K27me3 represents a repressive mark deposited by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) and is typically associated with facultative heterochromatin and developmental gene silencing [13] [14]. H3K9me3, in contrast, is a hallmark of constitutive heterochromatin formation, particularly in pericentromeric and telomeric regions, and is mediated by SUV39H1/2 methyltransferases [13].

These modifications exhibit distinct genomic distributions and functional characteristics. H3K4me3 typically forms sharp peaks at promoters, while H3K27me3 can form large organized chromatin lysine domains (LOCKs) spanning hundreds of kilobases [14]. Interestingly, these marks can co-occur at certain genomic locations, creating "bivalent" domains that maintain genes in a transcriptionally poised state, ready for rapid activation or stable repression during cellular differentiation [14]. The antagonistic relationship between H3K4me3 and repressive marks creates a dynamic regulatory system that controls cell identity and function.

Technically, the analysis of these different modifications requires tailored experimental and computational approaches. While H3K4me3 peaks are typically sharp and well-defined, requiring peak-calling algorithms like MACS2, broader marks like H3K27me3 LOCKs benefit from domain-calling algorithms such as SICER or ChromaBlocks [17]. Understanding these technical considerations is essential for appropriate experimental design and data interpretation in comprehensive epigenetic studies.

Future Directions and Concluding Remarks

The study of H3K4me3 continues to evolve with emerging technologies and conceptual frameworks. Recent advances in single-cell ChIP-seq methods promise to reveal H3K4me3 heterogeneity within cell populations, potentially uncovering novel regulatory principles in development and disease. Similarly, the integration of H3K4me3 data with other genomic and epigenomic datasets through multi-omics approaches provides increasingly comprehensive views of epigenetic regulation.

The development of more precise epigenetic editing tools represents another exciting frontier, enabling not only targeted deposition but also erasure of H3K4me3 at specific genomic locations. These approaches will further elucidate the causal relationships between H3K4me3 and transcriptional outcomes, potentially leading to novel therapeutic strategies for epigenetic diseases. Additionally, the discovery of "reader" proteins that specifically recognize H3K4me3 and mediate its functional effects continues to expand our understanding of the mechanistic basis of H3K4me3-dependent transcription.

In conclusion, H3K4me3 represents a central epigenetic mark with well-established roles in promoter activity and transcriptional initiation, while ongoing research continues to reveal novel functions in intergenic regions and diverse biological contexts. Its analysis through ChIP-seq and related technologies provides critical insights into normal development and disease processes, with growing applications in drug discovery and therapeutic development. As part of the broader epigenetic landscape including H3K27me3 and H3K9me3, H3K4me3 contributes to the sophisticated regulatory systems that control genome function and cellular identity.

Histone modifications serve as crucial epigenetic markers that regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Among these, the trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3) represents a fundamental repressive mark associated with transcriptional silencing. This modification is centrally deposited and maintained by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), which plays pivotal roles in cell fate determination, developmental regulation, and disease pathogenesis [20]. The precise mechanisms through which H3K27me3 contributes to gene silencing—through direct chromatin compaction, recruitment of additional repressive complexes, or facilitation of long-range chromatin interactions—have become increasingly refined through advanced genomic technologies. This technical guide examines H3K27me3 within the broader context of chromatin landscape analysis using ChIP-seq methodologies, particularly when integrated with complementary histone marks such as H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 to decode the multilayer regulatory logic of eukaryotic genomes.

Molecular Machinery: PRC2 Complex and H3K27me3 Deposition

Architecture of the PRC2 Core Complex

The PRC2 complex exhibits an exquisite molecular architecture that permits functional modulation and precise regulation of its enzymatic activity. The core PRC2 complex in mammals comprises four essential subunits [20]:

- EZH2 or EZH1: The catalytic subunit containing the SET domain responsible for methyltransferase activity. EZH2-containing complexes show robust allosteric activation, while EZH1 complexes are less responsive to such activation.

- EED: Mediates allosteric activation and chromatin spreading through its WD40 repeat domain that recognizes H3K27me3, creating a positive feedback loop for propagation.

- SUZ12: Provides structural integrity through its C-terminal VEFS domain and serves as a platform for recruiting various accessory factors via its N-terminal extension.

- RBBP4/7: Facilitates chromatin recruitment by directly binding nucleosomes, a process inhibited by H3K4 methylation.

PRC2 Subcomplexes and Accessory Factors

Beyond the core complex, PRC2 incorporates accessory factors that define distinct subcomplexes with specialized targeting capabilities [20]:

Table 1: PRC2 Subcomplexes and Their Key Accessory Factors

| Subcomplex | Accessory Factors | Recruitment Mechanisms | Functional Specialization |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRC2.1 | PCL1/2/3 (PHF1, MTF2, PHF19) | Binds CpG islands via EH module; recognizes H3K36me3 via Tudor domain | De novo chromatin targeting |

| EPOP (C17ORF96) | Interacts with Elongin complex; suppresses transcriptional elongation | Modulation of transcriptional activity | |

| PALI1/2 (C10ORF12) | Positively modulates catalytic activity during embryogenesis | Developmental gene regulation | |

| PRC2.2 | JARID2 | Binds H2AK119ub1, lncRNAs, and DNA; its K116me3 mimics H3K27me3 for allosteric activation | Facilitates recruitment to H2AK119ub1-marked regions |

| AEBP2 | Stabilizes PRC2 binding to genomic targets; interacts with DNA | Complex stabilization and DNA binding |

Figure 1: PRC2 Core Complex Architecture and Recruitment Mechanisms. The diagram illustrates the core subunits and accessory factors that define PRC2.1 and PRC2.2 subcomplexes, highlighting their specialized roles in targeting and depositing the H3K27me3 repressive mark.

Regulation of PRC2 Activity

The catalytic function of PRC2 is subject to multifaceted regulation through various mechanisms [20]:

- Allosteric activation: EED recognition of H3K27me3 creates a positive feedback loop for propagation of this mark along chromatin.

- Competitive inhibition: CXORF67/EZHIP uses an H3-like peptide sequence to competitively inhibit PRC2 activity by binding the EZH2 SET domain.

- Oncohistone inhibition: Cancer-associated H3K27M mutant histones potently inhibit PRC2 activity by sequestering the enzyme.

- RNA-mediated regulation: Both nascent mRNAs and long noncoding RNAs can facilitate PRC2 eviction or functional restriction.

Genomic Distribution and Functional Profiles of H3K27me3

Distinct H3K27me3 Enrichment Profiles

Advanced ChIP-seq analyses have revealed that H3K27me3 exhibits distinct genomic distribution patterns with specialized functional consequences [21]:

- Broad Domains: Extensive H3K27me3 enrichment across gene bodies correlates with strong transcriptional repression, representing the canonical silencing function.

- Promoter-Focused Peaks: Sharp H3K27me3 enrichment at transcription start sites, often associated with bivalent genes that also carry H3K4me3 marks, maintaining genes in a poised state.

- Actively Transcribed Genes: Surprisingly, promoter-proximal H3K27me3 peaks can sometimes associate with actively transcribed genes, suggesting context-dependent functions.

The prevalence of these profiles varies significantly across cell types, reflecting cell-type-specific epigenetic landscapes [21].

Large Organized Chromatin K-domains (LOCKs)

H3K27me3 frequently organizes into large chromatin domains spanning hundreds of kilobases, termed H3K27me3 LOCKs or H3K27me3-rich regions (MRRs) [22] [23]. These macro-domains display distinct characteristics:

Table 2: Characteristics of H3K27me3 Domain Types

| Feature | Typical Peaks | Short LOCKs (<100 kb) | Long LOCKs (>100 kb) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | Limited, discrete regions | Up to 100 kb | Several hundred kb |

| Peak Intensity | Moderate | High | Very High |

| DNA Methylation | Intermediate | Low | Very Low |

| Gene Expression | Variable repression | Strong repression | Very strong repression |

| Functional Enrichment | Diverse functions | Poised promoters | Developmental processes |

| Tumor Suppressor Association | Limited | Moderate | Strong |

Comparative analyses indicate that as domain size increases, so does the enrichment for developmental processes such as "epithelial cell differentiation," "embryonic organ development," and "gland development" [22]. These large repressive domains show preferential localization in partially methylated domains (PMDs), particularly short-PMDs in normal cells, where they contribute to robust silencing of developmental genes and oncogenes [22].

Silencing Mechanisms: From Chromatin Modification to Gene Repression

Effector Recruitment and Chromatin Compaction

H3K27me3 executes transcriptional silencing through several interconnected mechanisms [20]:

- Canonical PRC1 Recruitment: H3K27me3 is recognized by canonical PRC1 complexes through chromodomain-containing subunits, leading to H2AK119ub1 deposition and subsequent chromatin compaction.

- BAH Module-Containing Proteins: Proteins like BAHCC1 in humans directly recognize H3K27me3 and facilitate gene silencing through mechanisms including histone deacetylation.

- Phase Separation: Emerging evidence suggests that H3K27me3-rich domains may facilitate phase separation, leading to compaction of repressive chromatin.

Long-Range Chromatin Interactions

H3K27me3-rich regions function as silencer elements that can repress gene expression over long genomic distances through chromatin looping [23]. Key findings include:

- MRRs show dense chromatin interactions and preferentially interact with each other, forming repressive nuclear compartments.

- CRISPR excision of MRRs at interaction anchors leads to upregulated expression of interacting genes, altered H3K27me3 and H3K27ac levels at interacting regions, and disrupted chromatin interactions.

- Genes associated with MRR-mediated long-range interactions are particularly susceptible to H3K27me3 depletion strategies.

- This silencer functionality impacts cell identity, differentiation capacity, and in the context of cancer, xenograft tumor growth [23].

Figure 2: H3K27me3-Mediated Silencing Mechanisms. The diagram illustrates how H3K27me3 deposition leads to gene silencing through multiple effector pathways including PRC1 recruitment, BAH domain protein engagement, and long-range chromatin looping, ultimately maintaining cellular identity and developmental programs.

Bivalent Domains and Poised Transcription

A specialized chromatin configuration called the "bivalent domain" features both H3K4me3 (activating) and H3K27me3 (repressing) marks at promoter regions, maintaining developmental genes in a transcriptionally poised state [21] [24]. These bivalent domains:

- Are enriched in embryonic stem cells on key developmental regulators.

- Adopt a "winner-takes-all" approach during differentiation, resolving toward either active (H3K4me3-only) or repressed (H3K27me3-only) states.

- Allow rapid activation or silencing in response to developmental cues while maintaining low basal expression.

- In differentiated cells, bivalent promoters are often found in short LOCKs and are particularly susceptible to deregulation in cancer [22].

Experimental Analysis: H3K27me3 ChIP-seq Methodology

Standardized ChIP-seq Protocol

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) represents the gold standard for genome-wide mapping of H3K27me3 distributions. A robust protocol includes [25]:

Cell Fixation and Chromatin Preparation

- Crosslink proteins to DNA using 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Quench crosslinking with glycine.

- Prepare chromatin by sonicating to 200-500 bp fragments using a focused ultrasonicator.

- Verify fragment size distribution by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Immunoprecipitation

- Incubate 2-10 μg of H3K27me3-specific antibody (e.g., Millipore 07-449) with chromatin equivalent to 2×10^7 cells.

- Use Protein A/G magnetic beads for antibody capture.

- Wash beads sequentially with low salt, high salt, and LiCl buffers.

- Reverse crosslinks and purify DNA.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- End-repair, A-tail, and adapter-ligate immunoprecipitated DNA.

- Size-select libraries (~200-300 bp) using agarose gel electrophoresis or SPRI beads.

- Amplify libraries with 10-14 PCR cycles.

- Sequence using Illumina platforms (50-75 bp single-end reads recommended).

Bioinformatics Processing Pipeline

Quality Control and Alignment

- Trim adapters using Trim Galore! v0.4.0.

- Align to reference genome (hg19/mm10) using bowtie2 v2.2.5 with parameters to suppress multimapping.

- Remove PCR duplicates using picard MarkDuplicates.

- Filter out blacklisted regions (ENCODE blacklists).

Peak Calling and Domain Identification

- Call broad peaks using epic2 or similar broad peak callers compared to input controls.

- Merge peaks within 3 kb using bedtools merge.

- Identify H3K27me3-rich regions (MRRs) by clustering nearby peaks and ranking by H3K27me3 signal intensity [23].

- Detect LOCKs using the CREAM R package with size thresholds (short: <100 kb, long: >100 kb) [22].

Downstream Analysis

- Generate normalized bigWig files using deepTools bamCoverage with scaling factors.

- Compute enrichment matrices over features of interest using deepTools computeMatrix.

- Visualize data with deepTools plotHeatmap and Integrated Genome Viewer.

- Correlate with expression data from RNA-seq.

Integration with Multi-histone Mark Analyses

Comprehensive epigenetic analysis requires integration of H3K27me3 data with other key histone modifications [26] [24]:

- H3K4me3: Active promoter mark that combined with H3K27me3 defines bivalent promoters.

- H3K27ac: Active enhancer mark that antagonizes H3K27me3.

- H3K9me3: Constitutive heterochromatin mark with distinct silencing mechanisms.

- H3K36me3: Active transcription mark mutually exclusive with H3K27me3.

Integrative analysis reveals coordinated patterns where promoter/active chromatin marks (H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac) form one functional cluster, while heterochromatin marks (H3K27me3, H3K9me3) form another [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for H3K27me3 Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Millipore 07-449 (H3K27me3) | Well-validated for ChIP-seq; recommended by multiple protocols [21] [25] |

| Diagenode C15200147 (H4K20me1) | Used in co-immunoprecipitation studies with PRC components [27] | |

| Cell Lines | K562, ES cells, G1ME | Well-characterized models with established H3K27me3 profiles [21] [23] [27] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Bowtie2, SAMtools, Picard | Standard alignment and processing tools [25] |

| deepTools v3.3.1 | Comprehensive suite for ChIP-seq data analysis [25] | |

| CREAM R package | Specialized for LOCK identification [22] | |

| Epic2 | Broad peak caller optimized for H3K27me3 [25] | |

| Critical Assays | ChIP-seq | Genome-wide mapping of H3K27me3 distribution [21] [25] |

| ChIP-qPCR | Validation of specific loci [21] | |

| RNA-seq | Correlation of repression with expression [24] | |

| Hi-C/ChIA-PET | Chromatin interaction analyses [23] |

Evolutionary Conservation and Functional Adaptation

The PRC2 system and H3K27me3 mark exhibit remarkable evolutionary conservation across eukaryotes while showing functional adaptations [28] [29]:

- In the closest relatives of animals (choanoflagellates), H3K27me3 decorates cell type-specific genes and regulates transposable elements, suggesting these are ancestral functions.

- Across diverse eukaryotes including diatoms, red algae, and ciliates, PRC2 represses transposable elements through H3K27me3 deposition.

- During plant evolution, the proportion of transposable elements directly repressed by PRC2 decreased, while its role in developmental gene regulation expanded.

- In flowering plants, H3K27me3-marked transposable elements often contain transcription factor binding sites and may have been co-opted to shape transcriptional regulatory networks.

This evolutionary perspective suggests that PRC2 initially functioned in transposable element silencing in the last eukaryotic common ancestor, with developmental gene regulation representing a derived function that expanded in animals and plants [29].

H3K27me3 represents a central repressive signal in the eukaryotic epigenetic landscape, mediating flexible yet stable gene silencing through multifaceted mechanisms. Its functions span from transposable element control to developmental gene regulation, executed through molecular effectors that compact chromatin, modify histones, and facilitate long-range genomic interactions. The analytical framework provided here—encompassing molecular mechanisms, standardized protocols, and integrative bioinformatics approaches—equips researchers to decipher H3K27me3-mediated silencing in diverse biological contexts. As our understanding of PRC2 regulation and H3K27me3 functionality continues to evolve, particularly through comparative evolutionary analyses and single-cell methodologies, so too will our ability to target this system for therapeutic intervention in cancer and developmental disorders.

Histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation (H3K9me3) represents a fundamental epigenetic mark associated with transcriptionally repressed heterochromatin. This in-depth technical review examines the established role of H3K9me3 in maintaining genomic stability through silencing repetitive elements and its emerging functions in cell fate determination and disease pathogenesis. Within the broader context of ChIP-seq analysis research for H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3, we detail the specialized methodologies required for investigating this repressive mark, summarize key biological findings through structured data presentation, and explore the therapeutic potential of targeting the H3K9me3 regulatory machinery in human malignancies, particularly acute myeloid leukemia.

H3K9me3 demarcates transcriptionally silent genomic regions and serves as a cornerstone of constitutive heterochromatin, particularly at pericentromeric and telomeric regions [30] [31]. Beyond its traditional role in genomic stability, emerging evidence identifies H3K9me3 as a dynamic regulator of lineage-specific gene expression during cellular differentiation and development [30] [31] [32]. This positions H3K9me3 alongside other critical histone modifications like the activating H3K4me3 and the repressive H3K27me3 as essential markers for comprehensive epigenomic mapping using Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq).

Unlike the facultative heterochromatin mark H3K27me3, which maintains regions accessible to transcription factors and paused RNA polymerase, H3K9me3 domains are typically inaccessible to DNA-binding factors [30] [31]. This fundamental difference in chromatin accessibility necessitates distinct analytical approaches for ChIP-seq data interpretation. The following sections provide a technical examination of H3K9me3's molecular regulation, biological functions, and analysis methodologies.

Molecular Mechanisms of H3K9me3 Establishment and Function

Writers, Readers, and Erasers

The H3K9me3 landscape is dynamically regulated by a precise enzymatic machinery:

- Methyltransferases (Writers): SUV39H1, SUV39H2, and SETDB1 primarily catalyze H3K9me3, with SUV39H enzymes preferring H3K9me1 substrates to establish H3K9me3, while SETDB1 can mono-, di-, and tri-methylate H3K9me0 in vitro [30] [31]. G9a and GLP contribute to earlier methylation states (H3K9me1/2) in euchromatic regions [30].

- Reader Proteins: Heterochromatin Protein 1 (HP1) recognizes and binds to H3K9me2/3 marks through its chromodomain. Through self-oligomerization and interactions with other repressive complexes, HP1 facilitates chromatin compaction and spreading of heterochromatin [30] [33].

- Demethylases (Erasers): Enzymes such as KDM3A and KDM4C remove H3K9 methylation, providing dynamic regulation of this epigenetic mark and enabling developmental gene activation [31].

Heterochromatin Assembly and Physical States

H3K9me3-dependent heterochromatin formation occurs through both RNAi-dependent and RNAi-independent mechanisms [30]. In fission yeast and plants, RNAi machinery components are essential for constitutive heterochromatin formation, while transcription factor-mediated recruitment of H3K9 methyltransferases represents a key RNAi-independent pathway [30].

Recent research suggests heterochromatin exists in multiple physical states regulated by HP1a protein:

- A soluble state allowing DNA access

- A liquid-droplet state regulating gene repression through phase separation

- A gel-like state characterizing constitutive heterochromatin with structural functions [30]

Table 1: Key Enzymes Regulating H3K9me3 Dynamics

| Enzyme | Role | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| SUV39H1/SUV39H2 | Methyltransferase | Preferentially catalyzes H3K9me3, crucial for pericentromeric heterochromatin [30] |

| SETDB1 | Methyltransferase | Mono-, di-, and tri-methylates H3K9; silences developmental genes in ES cells [30] [31] |

| G9a/GLP | Methyltransferase | Establishes H3K9me1/2 in euchromatic regions [30] |

| HP1 (α,β,γ) | Reader | Binds H3K9me2/3; facilitates compaction through self-oligomerization [30] [33] |

| KDM4D | Demethylase | Removes H3K9me3 marks; improves somatic cell nuclear transfer efficiency [34] |

Figure 1: H3K9me3 Establishment and Recognition Pathway. The diagram illustrates the stepwise methylation of H3K9 by specific methyltransferases, recognition by HP1 proteins, and the reversal by demethylases.

Biological Functions of H3K9me3

Genomic Stability and Repetitive Element Silencing

H3K9me3 serves as a crucial guardian of genomic integrity by packaging repeat-rich sequences at centromeres and telomeres into constitutive heterochromatin [30] [31]. This silencing function prevents aberrant recombination between conserved genomic portions and maintains chromosome stability [30]. Recent research has highlighted the role of H3K9me3 in forming boundaries that maintain centromere position, size, and number, with loss of these boundaries leading to progressive expansion of CENP-A domains and nucleation of additional functional centromeres [35].

Cell Identity and Lineage Commitment

During cellular differentiation, H3K9me3 domains are reorganized to silence lineage-inappropriate genes, thereby promoting stable cell identity [30] [31]. In murine ES cells, Setdb1 binds and silences developmental regulatory genes and functions as a co-repressor of Oct3/4 to suppress trophoblast genes [31]. Conversely, Oct3/4 positively regulates the expression of demethylases KDM3A and KDM4C, which remove H3K9me2/3 from pluripotency genes like Tcl1 and Nanog [31].

Barrier to Cellular Reprogramming

H3K9me3 domains constitute a major barrier to changes in cell identity, impeding reprogramming of terminally differentiated cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [31] [32]. During reprogramming, large regions marked by H3K9me3 prevent binding of the Yamanaka factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc) in fibroblast genomes, while these same regions are accessible in pluripotent cells [31]. Reduction of H3K9me3 levels significantly improves reprogramming efficiency in somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) experiments [34].

Table 2: H3K9me3 Functions in Development and Disease

| Biological Context | H3K9me3 Function | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Early Embryogenesis | Differential establishment in maternal vs. paternal genomes; paternal pericentromeres show H3K9me1 and H3K27me3 instead [30] | Studies in zygotes showing asymmetric patterns [30] |

| Cell Fate Stability | Silences lineage-inappropriate genes in differentiated cells [31] [32] | Setdb1 knockout in ES cells leads to derepression of developmental genes [31] |

| Cellular Reprogramming | Acts as a barrier to iPSC generation; impedes transcription factor binding [31] [32] | Only <0.1% of cells successfully reprogram; H3K9me3 demethylation improves efficiency [32] |

| Cancer Pathogenesis | Aberrant methylation silences tumor suppressor genes in AML [33] | Preferential decrease of H3K9me3 at core promoter regions in AML blasts [33] |

| Centromere Stability | Forms boundaries maintaining centromere position and size [35] | Loss of H3K9me3 leads to CENP-A domain expansion and ectopic centromeres [35] |

Analytical Approaches: ChIP-seq for H3K9me3

Specialized Methodologies for H3K9me3 Mapping

The ENCODE consortium has established specific guidelines for H3K9me3 ChIP-seq due to its unique enrichment in repetitive genomic regions [36]. Key methodological considerations include:

- Sequencing Depth: Tissues and primary cells should have 45 million total mapped reads per replicate - significantly higher than requirements for narrow histone marks [36].

- Library Complexity: Preferred quality metrics include NRF > 0.9, PBC1 > 0.9, and PBC2 > 10 [36].

- Peak Calling: The broad-domain nature of H3K9me3 requires specialized peak-calling algorithms different from those used for punctate transcription factor binding sites [36].

Advanced methodologies like Gradient-seq have been developed to directly map compacted heterochromatin by separating sonication-resistant heterochromatin (srHC) from euchromatic fractions [30]. This method has revealed that srHC strongly correlates with H3K9me3, DNA methylation, Lamin B association, and DNase inaccessibility [30].

Comparative Analysis with Other Histone Marks

In computational analyses of histone modifications, H3K9me3 consistently clusters with H3K27me3 as heterochromatin marks, distinct from the active chromatin marks H3K4me3, H3K9ac, and H3K27ac [26]. This clustering reflects their shared repressive functions despite their distinct mechanisms of action.

Recent research in fungal models has identified distinct facultative heterochromatin subcompartments: K4-fHC (adjacent to euchromatin) and K9-fHC (adjacent to constitutive heterochromatin), each with different patterns of gene content and chromatin regulation [37]. These findings demonstrate the complex interplay between different histone modifications in organizing chromosomal domains.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for H3K9me3 Heterochromatin Analysis. The diagram outlines key steps from chromatin preparation through to bioinformatic identification of heterochromatin domains, highlighting the separation of sonication-resistant heterochromatin.

H3K9me3 in Disease and Therapeutic Targeting

Role in Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Other Cancers

In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), alterations in H3K9 methylation at promoter regions are associated with inactivation of tumor suppressor genes, blocked differentiation, and deregulated proliferation [33]. Comparative analysis of AML samples versus normal CD34+ stem cells revealed a preferential decrease in H3K9me3 at core promoter regions in AML blasts, with approximately 20% of differentially modified loci showing greater than 2-fold change [33].

Beyond hematological malignancies, H3K9me3 dysregulation has been documented in solid tumors. In pancreatic cancer metastasis, global changes in H3K9 methylation status provide selective advantage and increased treatment resistance without changes to the somatic mutation burden [33].

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

The reversible nature of H3K9 trimethylation makes its regulatory enzymes attractive therapeutic targets. Current strategies include:

- G9a Inhibitors: Treatment with G9a inhibitors (G9ai) reduces H3K9me1/2 levels, causing secondary loss of H3K9me3 and significantly improving development of mouse SCNT embryos [34]. Combined G9ai and trichostatin A treatment increased cloning efficiency to 14.5% [34].

- Histone Demethylase Activators: Forcing expression of demethylases like KDM4C and KDM3A to remove repressive H3K9 methylation marks [31].

- Combination Epigenetic Therapy: Leveraging the interplay between H3K9me3 and DNA methylation, where loss of H3K27me3 LOCKs in tumors leads to H3K9me3 redistribution [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for H3K9me3 Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| H3K9me3-specific Antibodies | Validated ChIP-grade antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of H3K9me3-associated chromatin for sequencing [36] |

| Methyltransferase Inhibitors | G9a inhibitors (RK-701) | Reduce H3K9me1/2 levels with secondary effects on H3K9me3 [34] |

| Histone Demethylase Enzymes | KDM4D, KDM3A, KDM4C mRNA | Experimental removal of H3K9me3 marks to improve reprogramming [31] [34] |

| Chromatin Assembly Factors | HP1 proteins (α, β, γ isoforms) | Study heterochromatin formation and phase separation mechanisms [30] [33] |

| Epigenetic Modulators | Trichostatin A (HDAC inhibitor) | Combined treatment to enhance H3K9me3 demethylation and zygotic genome activation [34] |

H3K9me3 represents a dynamic epigenetic mark with far-reaching functions beyond its classical role in constitutive heterochromatin. As a key regulator of cell identity and genomic stability, its precise manipulation offers promising therapeutic avenues for cancer and regenerative medicine. Future research should focus on elucidating the RNA-dependent mechanisms of H3K9me2/3 establishment in mammalian systems, the molecular basis for tissue-specific H3K9me3 domain organization, and developing more selective inhibitors targeting the H3K9me3 regulatory machinery. The integration of H3K9me3 mapping with other epigenomic datasets will continue to reveal new insights into chromosomal organization and gene regulatory networks in health and disease.

Biological Implications in Development, Differentiation, and Disease Pathogenesis

The packaging of DNA into chromatin is a dynamic regulator of gene expression, and post-translational modifications of histone proteins serve as a primary mechanism for controlling this dynamic process [38]. Among these modifications, the trimethylation of lysine residues on histone H3—specifically, H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3—constitutes a critical epigenetic layer governing cell identity, developmental transitions, and disease states [38] [26]. These marks form a complex regulatory language: H3K4me3 is predominantly associated with active gene promoters, H3K27me3 with facultative heterochromatin and repressed developmental genes, and H3K9me3 with constitutive heterochromatin and long-term silencing [38] [26]. The precise profiling of their genomic locations is essential for understanding transcriptional control.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has been the cornerstone method for generating genome-wide maps of these histone modifications [38]. By capturing a snapshot of protein-DNA interactions in vivo, ChIP-seq enables researchers to correlate the presence of specific histone marks with gene expression outcomes, thereby deciphering their biological functions [38]. This technical guide explores the roles of H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3 in development, differentiation, and disease, detailing the experimental and computational frameworks for their analysis and presenting key findings that underscore their therapeutic relevance.

Functional Roles of Key Histone Modifications

The table below summarizes the core functions and genomic distributions of H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3.

Table 1: Core Functional Characteristics of H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3

| Histone Mark | Associated Enzyme(s) | Primary Genomic Location | Transcriptional Role | Key Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | COMPASS/MLL complexes | Transcription Start Sites (TSS), Promoters [39] [40] | Activation [39] [26] | Promotes open chromatin; marks active and poised genes [38] [39] |

| H3K27me3 | Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) [21] [14] | Promoters, Gene bodies; can form broad domains (LOCKs) [21] [14] | Repression [21] [26] | Silences developmental genes; maintains cell identity; forms bivalent domains with H3K4me3 [38] [21] |

| H3K9me3 | SUV39H, SETDB1 | Constitutive heterochromatin, repetitive elements [38] [26] | Repression [26] | Maintains genomic stability; silences repeats and transposons [38] [14] |

Distinct and Combinatorial Signaling

These histone modifications rarely function in isolation. A quintessential example of their interplay is the bivalent domain, where a promoter is co-marked by the activating H3K4me3 and the repressing H3K27me3 [21]. This configuration maintains key developmental genes in a poised state, ready for rapid activation or stable silencing upon receiving differentiation cues [21] [14]. In embryonic stem cells (ESCs), over 85% of H3K27me3-marked promoters are bivalent, enriching for lineage-specific transcription factors [14].

Furthermore, these marks can form large chromatin domains. H3K27me3 Large Organized Chromatin Lysine Domains (LOCKs), spanning hundreds of kilobases, are strongly associated with developmental functions and show dynamic redistribution in cancer [14]. An antagonistic relationship exists between H3K27me3 and DNA methylation, as they exhibit negative correlation and limited genomic overlap [14].

Experimental Methodologies for ChIP-seq Profiling

Standard Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP-seq) Protocol

The standard ChIP-seq protocol involves crosslinking proteins to DNA in living cells, followed by chromatin fragmentation, immunoprecipitation with specific antibodies, and high-throughput sequencing [38]. The following diagram illustrates this core workflow.

Diagram 1: ChIP-seq Experimental Workflow

Detailed Protocol Steps:

- Crosslinking: Treat cells with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature to covalently crosslink histones to DNA. Quench the reaction with glycine [38] [21].

- Cell Lysis and Chromatin Preparation: Resuspend cell pellets in cell lysis buffer (e.g., 5 mM PIPES pH 8, 85 mM KCl, 1% igepal) with protease inhibitors. Pellet nuclei and resuspend in nuclei lysis buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) [38].

- Chromatin Fragmentation: Sonicate chromatin using a focused ultrasonicator (e.g., Bioruptor) to shear DNA to fragments between 200–500 bp. Critical optimization is required to achieve appropriate fragment size [38] [21].

- Immunoprecipitation: Dilute sheared chromatin in IP dilution buffer and incubate with validated, histone modification-specific antibodies overnight at 4°C [38].

- Recovery of Complexes: Add protein A/G magnetic beads to capture antibody-bound complexes. Wash beads extensively with low-salt and high-salt buffers to remove non-specific binding [38].

- Elution and Reverse Crosslinks: Elute protein-DNA complexes from beads using elution buffer (e.g., 50 mM NaHCO3, 1% SDS). Reverse crosslinks by incubating at 65°C with high salt [38].

- DNA Purification: Treat samples with RNase A and proteinase K. Purify DNA using a PCR purification kit (e.g., QIAquick from QIAGEN) [38].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from purified ChIP DNA using kits for the Illumina platform. The library is then amplified and sequenced [38] [21].

Advanced and Low-Input Methods

For samples with limited cell numbers, such as preimplantation embryos or rare cell populations, CUT&Tag (Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation) offers a powerful alternative [40]. This method uses a protein A-Tn5 transposase fusion protein targeted by antibodies to simultaneously cleave and tag genomic regions with sequencing adapters in situ, bypassing crosslinking, fragmentation, and library prep steps required in ChIP-seq [40]. A modified version, NON-TiE-UP CUT&Tag (NTU-CAT), has been successfully applied to profile H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 in single bovine blastocysts [40].

Data Analysis and Quality Control

Key Analytical Steps for ChIP-seq Data

- Read Alignment and Quality Control: Map sequenced reads to a reference genome (e.g., hg38) using aligners like BWA-MEM. Tools like FastQC assess raw read quality [41].

- Peak Calling: Identify significantly enriched regions using tools such as MACS2. H3K4me3 typically produces narrow peaks, while H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 often form broad domains, requiring appropriate settings [14] [41].

- Genome Partitioning and Domain Identification: For broad marks, partitioning algorithms (e.g., ChIP-Part) can segment the genome into signal-rich and signal-poor regions. The CREAM package can identify large domains like H3K27me3 LOCKs [14] [42].

- Differential Enrichment and Integrative Analysis: Compare peak signals between conditions to identify dynamic changes. Integration with RNA-seq data is crucial to correlate epigenetic states with gene expression [43] [41].

Critical Quality Control Checkpoints

- Fragment Size: Post-sonication fragment size should be verified, ideally 200-500 bp [38].

- Antibody Specificity: Use ChIP-grade antibodies validated for specificity to avoid false positives [38].

- Library Complexity: Ensure high complexity of the final library to guarantee even genome coverage [38].

Biological Implications in Development and Disease

Roles in Normal Development and Differentiation

The coordinated action of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 is fundamental to maintaining pluripotency and guiding differentiation. In ESCs, PRC2-dependent H3K27me3 represses developmental gene promoters, many of which are simultaneously marked by H3K4me3, creating a bivalent, poised state [21] [14]. Upon differentiation, resolution of bivalency—loss of H3K27me3 for activation or loss of H3K4me3 for stable silencing—directs cells toward specific lineages [14]. H3K9me3, in contrast, stabilizes heterochromatin and silences repetitive elements, ensuring genomic integrity during rapid cell divisions [38].

Dysregulation in Human Disease and Cancer

Dysregulation of these epigenetic marks is a hallmark of cancer, driving aberrant gene expression programs that promote tumorigenesis [14] [43] [41].

- H3K27me3 Redistribution in Cancer: In tumors, the distribution of H3K27me3 LOCKs is reconfigured. In normal cells, long H3K27me3 LOCKs are often found in partially methylated domains (PMDs) and help suppress oncogenes. In cancer cell lines (e.g., from esophageal and breast cancer), these long LOCKs shift away from short-PMDs, and a subset shows reduced H3K9me3, suggesting H3K27me3 may compensate for H3K9me3 loss to maintain silencing [14].

- Metabolic and Microenvironmental Influence: Studies in breast cancer cells (MCF7) under hypoxia revealed that H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 markings are dynamically modulated. Hypoxia can induce bivalency at promoters of developmental genes, a mechanism that may contribute to tumor cell plasticity and adaptation [43].

- Epigenetic Dysregulation in Breast Cancer Subtypes: Integrative analysis of H3K4me3 ChIP-seq and RNA-seq in breast cancer cell lines has identified subtype-specific miRNA-gene regulatory networks. For instance, distinct H3K4me3 patterns at miRNA promoters in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) versus luminal-A subtypes correlate with differential expression of target genes involved in cancer pathways [41].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ChIP-seq Analysis

| Reagent / Resource | Specification / Example | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Crosslinking Agent | Formaldehyde (37%) [38] | Covalently links DNA and associated proteins in vivo |

| Chromatin Shearing Device | Bioruptor Sonicator (Diagenode) [38] | Fragments chromatin to 200-500 bp for immunoprecipitation |

| Core Histone Modification Antibodies | H3K4me3: CST #9751S; H3K27me3: Millipore #07-449; H3K9me3: CST #9754S [38] [21] | Specific immunoprecipitation of target histone mark |

| DNA Purification Kit | QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN) [38] | Purification of immunoprecipitated DNA after reverse crosslinking |

| Sequencing Platform | Illumina Genome Analyzer / NovaSeq [38] | High-throughput sequencing of ChIP DNA fragments |

| Alignment Software | BWA-MEM [41] | Maps sequenced reads to a reference genome |

| Peak Calling Software | MACS2 (Model-based Analysis of ChIP-Seq) [41] | Identifies statistically significant regions of enrichment |

The following diagram illustrates how the interplay of histone modifications contributes to cell fate decisions and how their dysregulation leads to disease, particularly cancer.

Diagram 2: Histone Modification Dynamics in Fate and Disease

The combinatorial analysis of H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3 through ChIP-seq provides a powerful lens through which to view the mechanisms of development, differentiation, and disease. The ability to map these marks genome-wide has revealed fundamental principles of gene regulation, including the poised state of bivalent promoters and the large-scale organization of repressive chromatin. The dynamic redistribution of these marks, particularly H3K27me3 LOCKs, in diseases like cancer, highlights their profound clinical relevance. As low-input methods like CUT&Tag become more widespread, and as integrative multi-omics analyses become more sophisticated, our understanding of this epigenetic code will deepen. This knowledge is paving the way for novel therapeutic strategies, including epigenetic drugs that target the writers and erasers of these marks, offering new hope for modulating the epigenome in human disease.

Practical ChIP-seq Workflow: From Sample to Insight for H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3