Mining Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Patterns: From Foundational Technologies to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on mining genome-wide DNA methylation data.

Mining Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Patterns: From Foundational Technologies to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on mining genome-wide DNA methylation data. It covers the evolution of foundational technologies like bisulfite sequencing and microarrays, explores advanced methodologies including machine learning and novel computational tools, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges in data analysis, and discusses rigorous validation and comparative frameworks. By synthesizing current technologies and analytical approaches, this resource aims to bridge the gap between epigenetic research and the development of robust, clinically applicable biomarkers and diagnostic tools.

Core Technologies and Principles for Genome-Wide Methylation Discovery

DNA methylation, specifically the addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of cytosine (5-methylcytosine or 5mC), is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism regulating gene expression, genomic imprinting, and cellular differentiation [1] [2]. Accurate genome-wide mapping of this modification is crucial for elucidating its role in development, aging, and disease pathogenesis, particularly in cancer [3] [4]. For decades, bisulfite sequencing has been the gold standard method for detecting 5mC at single-base resolution [5] [6]. However, recent advancements have introduced enzymatic methods such as Enzymatic Methyl Sequencing (EM-seq) and TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS) as powerful alternatives [3] [7]. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these core technologies, framing their utility within a broader thesis on mining genome-wide DNA methylation patterns.

Fundamental Principles of Conversion Chemistry

Bisulfite Conversion

The principle of bisulfite conversion, first reported in 1992, relies on the differential reactivity of sodium bisulfite with cytosine versus 5-methylcytosine [7] [6]. Treatment of DNA with sodium bisulfite under acidic conditions deaminates unmethylated cytosine residues to uracil, which is then read as thymine during subsequent PCR amplification and sequencing. In contrast, methylated cytosines (5mC) are largely resistant to this conversion and remain as cytosine [7] [5]. This process creates specific C-to-T transitions in the sequence data, enabling base-resolution discrimination between methylated and unmethylated sites. A key limitation is that bisulfite treatment cannot distinguish between 5mC and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), as both are protected from deamination [7] [6].

Enzymatic Conversion (EM-seq and TAPS)

Enzymatic methods achieve the same end result—C-to-T transitions in sequencing data—through a series of enzyme-catalyzed reactions, thereby avoiding the harsh conditions of bisulfite chemistry.

EM-seq (Enzymatic Methyl Sequencing): This method employs a two-step enzymatic process. First, the TET2 enzyme oxidizes 5mC and 5hmC to 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC). Simultaneously, T4-BGT glucosylates 5hmC, protecting it from downstream deamination. In the second step, the APOBEC3A enzyme deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracil, while the oxidized methylcytosines (5caC) remain intact [7] [2] [8]. Subsequent PCR amplification then converts uracils to thymines.

TAPS (TET-assisted Pyridine borane Sequencing): TAPS utilizes the TET enzyme to oxidize 5mC and 5hmC to 5caC, followed by chemical reduction of 5caC to uracil using pyridine borane [7]. In the subsequent PCR, uracil is amplified as thymine. A variant, TAPSβ, uses a bisulfite step after oxidation to deaminate unmodified cytosines, combining enzymatic and chemical approaches [7].

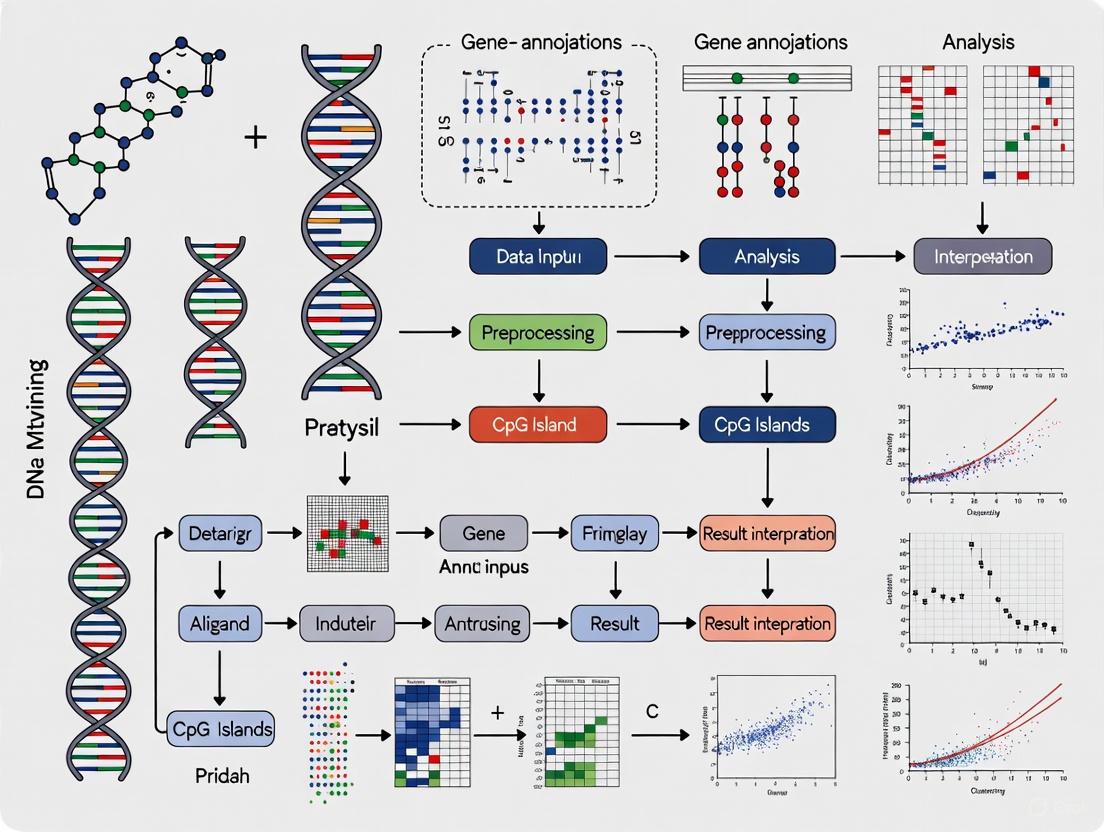

Diagram 1: Comparative workflows of Bisulfite, EM-seq, and TAPS conversion methods. Each pathway transforms genomic DNA, distinguishing methylated from unmethylated cytosines for sequencing.

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Metrics

Robust comparison of these methods requires evaluating key performance metrics across different sample types, especially clinically relevant samples like cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of DNA Methylation Detection Methods

| Performance Metric | Conventional Bisulfite (CBS) | Ultra-Mild Bisulfite (UMBS) | EM-seq | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Library Yield | Low, significantly degraded | High, outperforms CBS & EM-seq at low inputs | Moderate, lower than UMBS due to purification losses | [3] |

| DNA Damage & Fragmentation | Severe, significant fragmentation | Substantially reduced, preserves integrity | Minimal, non-destructive | [3] [7] |

| Duplication Rate (Library Complexity) | High (lower complexity) | Low (higher complexity) | Low to moderate (good complexity) | [3] |

| Background Noise (Non-conversion) | <0.5% | ~0.1% (very low and consistent) | >1% (can be high and inconsistent at low inputs) | [3] |

| CpG Coverage Uniformity | Significant bias, poor in GC-rich regions | Good improvement over CBS | Excellent, most uniform | [3] [2] |

| Detection of Unique CpGs | Lower | High | Highest | [2] [8] |

| Input DNA Requirements | High (typically >100ng) | Very Low (10pg - 10ng) | Low (10ng - 100ng) | [3] [8] |

| Distinction of 5mC from 5hmC | No | No | Yes (with T4-BGT protection) | [7] [8] |

Recent advancements like Ultra-Mild Bisulfite Sequencing (UMBS-seq) have addressed some traditional bisulfite limitations. UMBS-seq uses an optimized formulation of ammonium bisulfite at a specific pH and a lower reaction temperature (55°C for 90 minutes) to maximize conversion efficiency while minimizing DNA damage [3]. In evaluations, UMBS-seq demonstrated higher library yields and complexity than both CBS-seq and EM-seq across a range of low-input DNA amounts (5 ng to 10 pg), with significantly lower background noise (~0.1% unconverted cytosines) than EM-seq, which exceeded 1% at the lowest inputs [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) Protocol

This protocol is adapted from standard procedures using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research) or similar.

- DNA Shearing and Input: Use 50-200 ng of genomic DNA. For FFPE samples, consider prior repair. Shear DNA to desired fragment size (e.g., 200-500 bp) via sonication or enzymatic fragmentation.

- Bisulfite Conversion:

- Denature DNA by adding NaOH (final concentration 0.1-0.3 M) and incubating at 37-42°C for 15-30 minutes.

- Add sodium bisulfite solution (pH ~5.0) and incubate in a thermal cycler using a programmed regimen (e.g., 95-99°C for 30-60 seconds for denaturation, followed by 50-60°C for 45-90 minutes for conversion, for 10-20 cycles). Newer ultra-mild protocols use a single, longer incubation at 55°C [3].

- Desalt and purify the converted DNA using spin columns or beads. Elute in a low-salt buffer or water.

- Library Preparation: Use commercial kits designed for bisulfite-converted DNA (e.g., NEBNext Q5U Master Mix, NEB #M0597). These kits employ DNA polymerases tolerant of uracil and high AT content [9].

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate methylated or universal adapters to the purified, converted DNA.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the library with 6-18 cycles using primers compatible with your sequencer.

- Purification and Quality Control:

- Purify the final library using size-selection beads.

- Assess quality and quantity via bioanalyzer, and validate conversion efficiency using spike-in controls like unmethylated lambda DNA (expected conversion rate ≥99.5%) [5].

Enzymatic Methyl Sequencing (EM-seq) Protocol

This protocol is based on the NEBNext EM-seq kit (New England Biolabs).

- DNA Input and Shearing: Use 1-100 ng of genomic DNA. Shear DNA as in WGBS.

- Oxidation and Protection:

- Set up the oxidation master mix containing TET2 enzyme and oxidation booster. Add to DNA.

- Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour. This step oxidizes 5mC and 5hmC to 5caC and glucosylates 5hmC.

- Deamination:

- Add the deamination master mix containing APOBEC3A enzyme.

- Incubate at 37°C for 3 hours. This step deaminates unmodified cytosines to uracil.

- Library Preparation:

- The subsequent steps can be performed using standard Illumina library prep kits or the accompanying NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate adapters to the enzymatically converted DNA.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the library with a limited number of cycles (e.g., 6-12).

- Purification and Quality Control:

- Purify the library via size-selection beads.

- QC as for WGBS, confirming conversion efficiency with lambda and pUC19 controls [8].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflows for Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) and Enzymatic Methyl Sequencing (EM-seq). Key differences include conversion chemistry and DNA handling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of DNA methylation studies requires careful selection of reagents and kits tailored to the chosen method and sample type.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for DNA Methylation Analysis

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Application | Key Features / Notes | Method Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research) | Bisulfite conversion of DNA | Common in published protocols; includes all reagents for conversion and cleanup. | CBS, UMBS |

| NEBNext EM-seq Kit (New England Biolabs) | Enzymatic conversion for whole-genome methylation sequencing | Includes TET2 and APOBEC3A enzymes; minimal DNA damage. | EM-seq |

| NEBNext Q5U Master Mix (NEB #M0597) | PCR amplification of bisulfite-converted libraries | Hot start, high-fidelity polymerase tolerant of uracil. | CBS, UMBS |

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit (NEB #E7645) | Library preparation for NGS | Robust yield from low-input and GC-rich targets; can be used post-EM-seq conversion. | EM-seq, CBS (with conversion) |

| NEBNext Multiplex Oligos | Indexing and multiplexing samples | Unique Dual Indexes to prevent cross-talk; compatible with bisulfite sequencing. | CBS, UMBS, EM-seq |

| Methylated & Unmethylated Control DNA (e.g., Lambda, pUC19) | Conversion efficiency control | Unmethylated lambda DNA (expect ~0.2% C); methylated pUC19 (expect >95% C). | All Methods |

| Accel-NGS Methyl-Seq DNA Library Kit (Swift Biosciences) | Full library prep for bisulfite sequencing | Uses post-bisulfite adapter tagging (PBAT) to minimize loss. | CBS |

| Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip (Illumina) | Genome-wide methylation array | Interrogates >850,000 CpG sites; uses bisulfite-converted DNA. | CBS (Microarray) |

| PyOxim | PyOxim, CAS:153433-21-7, MF:C17H29F6N5O3P2, MW:527.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| RR6 | RR6, CAS:1351758-37-6, MF:C16H23NO4, MW:293.36 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Application in Mining Genome-Wide Methylation Patterns

The choice of methodology directly impacts the quality and scope of conclusions drawn in genome-wide methylation data mining.

Bias Correction in Data Analysis: WGBS data often requires stringent non-conversion filters (e.g., discarding reads with >3 consecutive unconverted CHH sites) to mitigate false positives, a step less critical for EM-seq due to its lower background noise [2]. Furthermore, WGBS can overestimate methylation levels, particularly in CHG and CHH contexts, in regions with high GC content or methylated cytosine density. EM-seq demonstrates more consistent performance across varying genomic contexts, leading to more accurate differential methylation calling [2].

Clinical and Biomarker Discovery: For analyzing cell-free DNA (cfDNA) or FFPE samples—where DNA is fragmented and scarce—methods that preserve DNA integrity are paramount. UMBS-seq and EM-seq both effectively preserve the characteristic triple-peak profile of plasma cfDNA after treatment, enabling robust biomarker detection for early cancer diagnosis and monitoring [3] [7]. A 2025 study on chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) successfully used enzymatic WGMS on a clinical trial cohort to identify methylation changes linked to treatment response, highlighting the clinical utility of this method [7].

Integration with Machine Learning: Large-scale methylation datasets generated by these methods are increasingly analyzed with machine learning (ML) to build diagnostic classifiers. For instance, ML algorithms have been used to predict cancer outcomes and standardize diagnoses across over 100 central nervous system tumor subtypes using methylation profiles [1]. The higher data quality, greater coverage of CpGs, and reduced bias from enzymatic methods and UMBS-seq provide cleaner input features for these models, potentially improving their accuracy and generalizability.

The evolution from conventional bisulfite sequencing to milder bisulfite protocols and fully enzymatic methods represents a significant advancement in the field of epigenomics. While bisulfite conversion remains a robust and widely used technology, enzymatic methods like EM-seq offer superior performance in terms of DNA preservation, library complexity, coverage uniformity, and accuracy, especially for low-input and clinically derived samples. The development of ultra-mild bisulfite methods demonstrates that chemical conversion still has room for innovation. The choice between these methods for genome-wide data mining depends on the specific research question, sample type, and resource constraints. For projects requiring the highest data quality from precious samples, enzymatic conversion is increasingly the method of choice, whereas for larger-scale studies with ample high-quality DNA, bisulfite methods remain cost-effective. As the field moves towards the integration of methylation data with other omics layers and its application in liquid biopsies and personalized medicine, the adoption of these advanced conversion technologies will be crucial for generating reliable and biologically meaningful insights.

Enrichment-based methods represent a cornerstone technique in the field of epigenomics for profiling DNA methylation patterns on a genome-wide scale. These approaches, primarily Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeDIP-seq) and Methylated DNA Capture sequencing (MethylCap-seq), rely on the physical isolation of methylated DNA fragments prior to sequencing, offering a cost-effective alternative to bisulfite-based methods [10] [11]. MeDIP-seq utilizes 5-methylcytosine (5mC)-specific antibodies to immunoprecipitate methylated DNA, whereas MethylCap-seq employs the methyl-binding domain (MBD) of human MBD2 protein to capture methylated fragments [12] [10]. Their utility is particularly pronounced in scenarios requiring low DNA input, such as clinical tumor biopsies, oocytes, and early embryos, or when working with archived biobank samples like dried blood spots where DNA quantity and quality are limiting factors [10] [13]. Furthermore, these methods provide unbiased, full-genome coverage without the limitations of restriction sites or pre-defined CpG islands, making them powerful tools for discovery-oriented research into the role of epigenetic alterations in cancer, neurodevelopmental disorders, and complex multifactorial diseases [12] [10] [1].

Core Methodological Principles

MeDIP-seq (Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation Sequencing)

The MeDIP-seq protocol begins with the fragmentation of genomic DNA, typically via sonication, to create a library of random fragments. These fragments are then denatured to produce single-stranded DNA, a crucial step as the 5mC antibody requires single-stranded DNA for efficient immunoprecipitation [10]. The denatured DNA is incubated with a specific antibody against 5-methylcytosine (5mC), which binds to and enriches the methylated fragments. The antibody-DNA complexes are then captured using beads coated with an antibody-binding protein (e.g., protein A or G). After rigorous washing to remove non-specifically bound DNA, the enriched methylated DNA is eluted from the beads, purified, and converted into a sequencing library [10] [14]. A key consideration in MeDIP-seq is the CpG density bias; the antibody's binding efficiency is influenced by the density of methylated CpGs, meaning regions with very low methylation density (<1.5%) may be underrepresented or misinterpreted as unmethylated [10].

MethylCap-seq (Methylated DNA Capture Sequencing)

MethylCap-seq also starts with the sonication of genomic DNA, but the fragments remain double-stranded. The fragmented DNA is incubated with the MBD domain of the MBD2 protein, which has a high affinity for methylated CpG dinucleotides. This MBD protein is often immobilized on beads, such as the M-280 Streptavidin Dynabeads used in the MethylMiner kit, to facilitate the capture process [12]. A distinctive feature of some MethylCap-seq protocols is the ability to perform sequential elutions with buffers of increasing salt concentration (e.g., low, medium, and high salt). This can fractionate the DNA based on the density of methylated CpGs, potentially providing a rudimentary level of quantitative information [11]. The eluted, methylated DNA is then purified and processed for library construction and high-throughput sequencing [12]. Benchmarking studies have suggested that MethylCap-seq can be more effective at interrogating CpG islands than MeDIP-seq [12].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows for both methods, highlighting their key similarities and differences.

Comparative Analysis of Enrichment Techniques

When selecting an appropriate methodology for a DNA methylation study, researchers must consider the relative strengths and limitations of each approach. The following table provides a structured comparison of MeDIP-seq and MethylCap-seq across several critical parameters.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of MeDIP-seq and MethylCap-seq

| Parameter | MeDIP-seq | MethylCap-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Immunoprecipitation with 5mC antibody [10] | Affinity capture with MBD2 protein domain [12] |

| Genomic Resolution | ~150 bp (lower than bisulfite sequencing) [10] | Similar to MeDIP-seq; ~500 bp bins common for analysis [12] |

| Key Advantages | Covers CpG and non-CpG 5mC; requires low input DNA; cost-effective [10] [13] | Effective at CpG island interrogation; high genome coverage; potential for fractionated elution [12] [11] |

| Inherent Limitations | Antibody-based selection bias; under-represents low mC density regions; resolution is region-based, not single-base [10] [14] | CpG density and GC-content bias; sequence data requires correction for CpG density [15] |

| Optimal Use Cases | Genome-wide methylation patterns; low-input samples (e.g., biopsies, embryos) [10] [13] | Discovery of DMRs with high genome coverage; studies focused on CpG-rich regions [12] [15] |

Independent, large-scale comparisons of these methods with microarray-based approaches like the Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip have revealed important performance differences. One study on glioblastoma and normal brain tissues found that while the microarray demonstrated higher sensitivity for detecting methylation at predefined loci, MethylCap-seq offered a far larger genome-wide coverage, identifying more potentially relevant methylation regions [15]. However, this more comprehensive character did not automatically translate into the discovery of more statistically significant differentially methylated loci in a biomarker discovery context, underscoring their complementary nature [15]. Another benchmark study noted that all evaluated methods, including MeDIP-seq and MethylCap-seq, produced accurate data but differed in their power to detect differentially methylated regions between sample pairs [11].

Successful execution of an enrichment-based methylation study requires both wet-lab reagents and robust bioinformatics tools. The table below outlines key components of the research toolkit.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for enrichment-based methylation profiling

| Category | Item | Function / Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | 5mC-specific Antibody (for MeDIP) | Immunoprecipitation of methylated DNA fragments [10]. |

| MBD2-Biotin Protein & Streptavidin Beads (for MethylCap) | Capture and purification of methylated DNA fragments [12]. | |

| MethylMiner Kit (Invitrogen) | Commercial kit for performing MethylCap-seq [12]. | |

| Sonication Device (e.g., Covaris) | Fragmentation of input genomic DNA to desired size [12] [13]. | |

| Computational Tools | MEDIPS (R Bioconductor) | Quality control, normalization, and DMR analysis for MeDIP-seq/MethylCap-seq data [12] [14]. |

| Batman | Bayesian tool for methylation analysis; estimates absolute methylation levels [14]. | |

| MeDUSA | Pipeline for full analysis, including sequence alignment, QC, and DMR annotation [10]. | |

| Bowtie / BWA | Short-read aligners for mapping sequenced reads to a reference genome [12] [13]. | |

| SAMtools | Processing and manipulation of sequence alignment files [12]. |

Data Analysis Workflow: From Raw Sequences to Biological Insight

The computational analysis of MeDIP-seq and MethylCap-seq data involves a multi-step process to translate raw sequencing reads into interpretable biological results. A standardized workflow is essential for robust and reproducible findings.

Sequence Processing and Alignment: Raw sequencing reads (e.g., in FASTQ format) are first pre-processed, which includes quality control checks and adapter trimming. The clean reads are then aligned to a reference genome using short-read aligners like Bowtie or BWA, generating files in SAM/BAM format [12] [13]. A critical subsequent step is the removal of PCR duplicates to mitigate artifacts and ensure accurate representation of unique fragments [12].

Quality Control (QC) and Enrichment Assessment: Assay-specific QC is vital. The MEDIPS package is commonly used to calculate key metrics [12] [14]. These include:

- Saturation Analysis: Assesses sequencing library complexity and potential reproducibility via Pearson correlation [12].

- CpG Enrichment Calculation: The relative frequency of CpGs in sequenced reads compared to the reference genome; a value >1 indicates successful enrichment [12] [13].

- CpG Coverage: The fraction of CpG dinucleotides in the genome covered by a minimum number of reads (e.g., 5x) [12].

Read Quantification and Differential Methylation Analysis: The aligned reads are counted in predefined genomic bins (e.g., 500 bp) or across features of interest (e.g., promoters, CpG islands) [12]. Reads per million (RPM) scaling is applied to normalize for sequencing depth. For differential analysis between biological groups, non-parametric statistical tests like the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for two groups) or Kruskal-Wallis test (for >2 groups) are often employed on the binned count data. Results are adjusted for multiple testing (e.g., False Discovery Rate, FDR) to generate a list of significant differentially methylated regions (DMRs) [12].

Data Visualization and Integration: The final step involves visualizing the results for interpretation. Tools like the Anno-J web browser can display methylation profiles across genomic regions [12]. Furthermore, DMRs can be integrated with other genomic datasets, such as gene expression or chromatin modification data, to infer functional biological context [14].

The following diagram summarizes this multi-stage analytical pipeline.

MeDIP-seq and MethylCap-seq are powerful, cost-efficient technologies for generating genome-wide DNA methylation profiles. Their compatibility with low-input DNA makes them particularly suited for precious clinical samples and large-scale biobank studies [10] [13]. While they offer lower resolution than bisulfite sequencing, their ability to provide unbiased coverage of the entire genome, including non-RefSeq genes and repetitive elements, makes them excellent tools for agnostic discovery [12] [13]. The choice between them hinges on the specific research question: MeDIP-seq is advantageous for its sensitivity to non-CpG methylation and well-established low-input protocols, whereas MethylCap-seq may offer more effective coverage of CpG-rich regions. As with all genomic technologies, the integrity of the results is deeply connected to rigorous experimental execution and a bioinformatic pipeline that accounts for the specific biases inherent in each enrichment method. Their continued application, often integrated with other genomic data types and increasingly powerful machine learning algorithms, promises to further illuminate the critical role of DNA methylation in health and disease [1] [14].

The Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip represents a cornerstone technology in the field of epigenomics, enabling genome-wide DNA methylation profiling at single-nucleotide resolution. This platform has become instrumental for uncovering the role of epigenetic modifications in gene regulation, cellular differentiation, and disease pathogenesis. As a robust and cost-effective solution for large-scale epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS), cancer research, and biomarker discovery, the EPIC BeadChip provides extensive coverage of biologically significant regions within the human methylome [16]. Its integration within a broader DNA methylation data mining framework allows researchers to extract meaningful patterns from complex epigenetic datasets, thereby advancing our understanding of genome-wide regulatory mechanisms in both normal physiology and disease states.

The Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip is a microarray-based technology designed for quantitative methylation analysis. The current version, the Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0,interrogates approximately 930,000 methylation sites per sample, focusing on CpG islands, gene promoters, enhancers, and other functionally relevant genomic regions [16]. This extensive coverage captures critical epigenetic information while maintaining cost-effectiveness for population-scale studies.

Table 1: Key Specifications of the Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 BeadChip

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Number of Markers | ~930,000 methylation sites [16] |

| Sample Throughput | 8 samples per array; up to 3,024 samples per week on a single iSCAN system [16] |

| Input DNA Requirement | 250 ng DNA [16] |

| Assay Reproducibility | >98% reproducibility between technical replicates [17] |

| Compatible Sample Types | Whole blood, FFPE tissue, and other specialized types [16] |

| Instruments | iScan System, NextSeq 550 System [16] |

The technology employs two distinct Infinium assay chemistries to achieve optimal genome coverage. Both chemistries enable highly multiplexed genotyping of bisulfite-converted genomic DNA, providing precise methylation measurements independent of read depth [16] [17]. The content of the EPIC v2.0 BeadChip represents an expert-curated selection that builds upon previous versions, with enhanced coverage of regulatory elements such as enhancers, CTCF-binding sites, and open chromatin regions identified through techniques like ATAC-Seq and ChIP-seq [16]. This strategic content expansion facilitates more comprehensive investigation of the functional epigenome.

Experimental Workflow

The end-to-end workflow for the Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip involves a series of critical steps, from sample preparation to data generation. Adherence to standardized protocols at each stage is paramount for ensuring data quality and reproducibility.

Sample Preparation and Bisulfite Conversion

The initial phase focuses on nucleic acid extraction and bisulfite treatment. For fresh or frozen tissues, high-purity DNA with an A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0 is recommended, achievable through phenol-chloroform or magnetic bead-based extraction methods [18]. When working with Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) samples, additional steps including deparaffinization, proteinase K digestion, and fragment screening are necessary to address cross-linking and DNA fragmentation [18]. The requirement for FFPE compatibility is significant given the vast biorepositories of tumor samples available for research [16].

Bisulfite conversion follows DNA extraction, serving as the fundamental reaction that enables methylation detection. During this process, unmethylated cytosines are converted to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged [18]. Conversion efficiency must exceed 95%, typically monitored using spike-in controls like Lambda DNA [18]. Traditional bisulfite treatment can cause substantial DNA degradation (30-50%); however, novel enzymatic conversion techniques (e.g., EM-seq) can reduce degradation to less than 5%, offering a significant advantage for limited or precious samples [18]. Following conversion, DNA undergoes purification and amplification to prepare it for hybridization.

BeadChip Hybridization and Scanning

The subsequent phase encompasses the actual microarray processing. The bisulfite-converted, single-stranded DNA is combined with the BeadChip, where it hybridizes to specific 50-70 base pair probes [18]. The hybridization process requires meticulous optimization of buffer conditions (e.g., 3M TMAC salt concentration) and temperature gradients (45-55°C) to balance probe binding specificity with background signal [18]. Molecular engineering techniques, such as probe shielding, have been employed to reduce non-specific binding and lower background noise by over 30% [18].

Following hybridization, the BeadChip undergoes stringent washing to remove unbound DNA. The bound DNA is then fluorescently labeled, and the array is scanned using a high-resolution system, such as the iScan [16] [18]. The resulting fluorescence signals are captured as images, which are processed to generate intensity data files (IDAT files) for downstream bioinformatics analysis.

Data Analysis Pipeline

The transformation of raw IDAT files into biological insights requires a sophisticated bioinformatics pipeline. This process involves quality control, preprocessing, normalization, and differential methylation analysis.

Quality Control and Preprocessing

Rigorous quality control is the first critical step. This includes assessing sample-level metrics such as DNA integrity and bisulfite conversion efficiency, and array-level metrics like signal intensity and detection p-values [18] [19]. Probes with a high detection p-value (> 0.01) are typically filtered out, as are probes known to contain single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), cross-reactive probes that map to multiple genomic locations, and those with negative intensity values [20] [19]. Tools like DRAGEN Array Methylation QC and MethylAid automate this process, using multidimensional clustering to identify and flag anomalous samples [18] [19].

After QC, the data undergoes preprocessing to calculate methylation levels. The most common metric is the beta-value (β), which represents the ratio of the methylated allele intensity to the sum of both methylated and unmethylated intensities, providing a value between 0 (completely unmethylated) and 1 (completely methylated) [19]. For statistical tests requiring homoscedasticity, the M-value (logit transformation of β) is often preferred [21].

Normalization and Differential Methylation Analysis

Normalization corrects for technical variability, such as systematic biases between arrays and differences in the hybridization efficiency of Infinium Type I and Type II probes [18]. Common methods include quantile normalization, which enforces a consistent signal distribution across all samples, and the Beta Mixture Quantile (BMIQ) dilation algorithm, which adjusts for the distributional differences between the two probe types [18].

Differential methylation analysis aims to identify CpG sites (DMPs) or regions (DMRs) that show significant methylation changes between experimental groups (e.g., disease vs. control). This is frequently performed using linear regression models (e.g., in the limma package) or Bayesian methods, while adjusting for covariates like age and gender [21] [18]. Multiple testing correction, such as the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, is essential to control the false discovery rate [21] [18]. Region-based analysis with tools like bumphunter can increase biological interpretability by identifying coherently methylated genomic regions [21] [19].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful execution of EPIC BeadChip workflows relies on a suite of specialized laboratory reagents and bioinformatics software.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Core Reagents | Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 Kit [16] | Includes BeadChips and reagents for amplification, fragmentation, hybridization, labeling, and detection. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit (e.g., Zymo Research) [16] | Converts unmethylated cytosine to uracil; purchased separately. | |

| FFPE QC and DNA Restoration Kits [16] | Recommended for optimal results with FFPE tissue samples. | |

| Laboratory Instruments | iScan System [16] [17] | High-throughput scanner for reading the fluorescence signals from BeadChips. |

| Automated Liquid Handling Systems [17] | Streamlines sample preparation workflow and reduces manual errors. | |

| Primary Analysis Software | GenomeStudio Methylation Module [16] [19] | Visualizes controls and performs basic analysis; not recommended for advanced differential methylation. |

| DRAGEN Array Methylation QC [22] [19] | Cloud-based software providing high-throughput, quantitative QC reporting. | |

| Partek Flow [19] | Offers interactive visualization, powerful statistics, and comprehensive downstream analysis. | |

| Bioconductor Packages (R) | SeSAMe [19] | End-to-end data analysis including advanced QC, normalization, and differential methylation. |

| Minfi & ChAMP [20] [19] | Comprehensive packages for preprocessing, QC, DMR calling, and EWAS. | |

| RnBeads [20] [19] | End-to-end analysis with enhanced reporting and exploratory analysis capabilities. |

Integration with Broader Data Mining and Research Applications

The true power of EPIC BeadChip data is unlocked through integration with other data types and the application of advanced computational approaches. In multi-omics frameworks, methylation data is correlated with transcriptomic (RNA-seq) and chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) data to build causal regulatory networks and distinguish direct epigenetic effects from indirect associations [18]. Tools like ChAMP facilitate this integration by constructing gene regulatory networks that link methylation changes with expression alterations [19].

Machine learning (ML) has become pivotal for mining genome-wide methylation patterns. Conventional supervised methods, such as support vector machines and random forests, are widely used for sample classification, prognosis, and feature selection [1]. More recently, deep learning models, including convolutional neural networks and transformer-based foundational models like MethylGPT and CpGPT, have demonstrated superior capability in capturing non-linear interactions between CpGs [1]. These models, pre-trained on vast methylome datasets (e.g., >150,000 samples), show robust cross-cohort generalization and offer more physiologically interpretable insights into regulatory regions [1].

A compelling application of this integrated approach is seen in cancer research. For instance, a study on osteosarcoma used EPIC array data to identify genome-wide methylation subtypes strongly predictive of chemotherapy response and patient survival [21]. Unsupervised clustering revealed a hypermethylated subgroup associated with poor treatment response and shorter survival, independent of clinical variables like metastatic status [21]. This highlights the potential of methylation data mining to uncover clinically relevant biomarkers that transcend the limitations of traditional genomic analyses.

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) represents the gold standard in epigenomic research for comprehensively detecting DNA methylation status at single-base resolution across the entire genome. This powerful technique relies on the fundamental principle that sodium bisulfite conversion differentially treats methylated and unmethylated cytosines, enabling researchers to create genome-wide methylation maps with unprecedented accuracy. WGBS has matured into an indispensable tool for uncovering the critical role of DNA methylation in gene regulation, cellular differentiation, and disease pathogenesis, providing the epigenetics community with an unparalleled capability to explore methylation patterns beyond CpG islands to include regulatory elements and repetitive regions.

The technological foundation of WGBS was established through the convergence of bisulfite chemistry and next-generation sequencing platforms. The first single-base-resolution DNA methylation map of the entire human genome was created using WGBS in 2009, marking a watershed moment in epigenomic research [23]. Since then, continuous methodological refinements have enhanced the efficiency, reduced DNA input requirements, and improved the cost-effectiveness of WGBS protocols, solidifying its position as the reference standard against which all other methylation profiling methods are validated [24] [25]. As a cornerstone technology in the data mining of genome-wide methylation patterns, WGBS provides the complete and unbiased methylation data necessary for constructing sophisticated epigenetic models and biomarkers.

Core Principles and Methodological Framework

Fundamental Biochemical Principles

The entire WGBS methodology hinges on the differential susceptibility of cytosine residues to bisulfite conversion based on their methylation status. When genomic DNA is treated with sodium bisulfite under controlled acidic conditions, unmethylated cytosines undergo a series of chemical transformations: sulfonation at the C-6 position, hydrolytic deamination to uracil sulfonate, and subsequent desulfonation under alkaline conditions to yield uracil. During PCR amplification, these uracil residues are replicated as thymines, resulting in C-to-T transitions in the sequencing data [23] [26]. In contrast, methylated cytosines (5-methylcytosine) are protected from this deamination process due to the methyl group at the C-5 position and thus remain as cytosines throughout the procedure [27].

This biochemical disparity creates a distinct genomic "fingerprint" where the methylation status of every cytosine can be deduced by comparing the bisulfite-converted sequence to the original reference genome. The key strength of this approach lies in its ability to detect methylation contexts beyond CpG sites, including CHG and CHH methylation (where H = A, T, or C), which are particularly relevant in plant epigenomics and stem cell biology [28] [23]. However, a significant limitation of conventional bisulfite treatment is its inability to distinguish between 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), as both modifications resist conversion [27]. This challenge has been addressed through specialized protocols like oxidative bisulfite sequencing (oxBS-Seq), which incorporates an additional oxidation step to specifically differentiate these closely related epigenetic marks [26].

Experimental Workflow and Technical Considerations

The end-to-end WGBS workflow comprises multiple critical stages, each requiring meticulous optimization to ensure data quality and reliability:

DNA Extraction and Quality Control: High-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA is extracted from target cells or tissues. Input requirements traditionally ranged from 500-1000 ng but have been substantially reduced to as little as 20 ng with novel library preparation techniques like tagmentation-based WGBS (T-WGBS) [26].

Library Preparation: DNA is fragmented through sonication, enzymatic digestion, or tagmentation approaches. Following end repair and A-tailing, methylated adapters are ligated to fragment ends. Two primary strategies exist: pre-bisulfite adapter ligation (where adapters are ligated before bisulfite treatment) and post-bisulfite adapter tagging (PBAT), which reduces DNA loss and is preferred for low-input samples [24].

Bisulfite Conversion: Adapter-ligated DNA undergoes sodium bisulfite treatment, typically using commercial kits optimized for complete conversion while minimizing DNA degradation. This represents the most critical step, as incomplete conversion can lead to false positive methylation calls [27].

PCR Amplification and Sequencing: Converted DNA is amplified using methylation-aware polymerases and subjected to high-throughput sequencing on platforms such as Illumina, with recommended coverage of 30x for mammalian genomes to ensure accurate methylation quantification [24] [23].

The following diagram illustrates the core WGBS workflow and the bisulfite conversion principle:

Advanced Methodological Variations

Library Preparation Methodologies

The evolution of WGBS library preparation strategies has significantly expanded its application across diverse research scenarios, particularly for limited or precious samples. The table below summarizes the principal library preparation methods, their applications, and performance characteristics:

Table 1: WGBS Library Preparation Methods and Performance Characteristics

| Method | Principle | DNA Input | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-bisulfite | Adapter ligation precedes bisulfite conversion | 500-1000 ng (standard) | Established protocol, high complexity libraries | Significant DNA loss, over-representation of methylated fragments |

| Post-bisulfite Adapter Tagging (PBAT) | Adapter ligation after bisulfite conversion | 100 ng (mammalian) | Reduced DNA loss, better for low-input samples | Potential site preferences in random priming |

| Tagmentation-based WGBS (T-WGBS) | Tn5 transposase mediates fragmentation and adapter insertion | ~20 ng | Minimal DNA input, fast protocol with fewer steps | Sequence bias related to Tn5 preferences |

| Enzymatic Methyl-seq (EM-seq) | Enzymatic conversion instead of bisulfite | Variable | Reduced DNA damage, better GC coverage, distinguishes 5mC from 5hmC | Newer method with less established protocols |

Specialized WGBS Derivatives

The fundamental WGBS approach has been adapted into several specialized derivatives to address specific research needs:

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS): This method utilizes restriction enzymes (e.g., MspI) to selectively target CpG-rich regions, including promoters and CpG islands, thereby reducing sequencing costs while maintaining coverage of functionally relevant methylated areas. Although RRBS covers only 10-15% of genomic CpGs, it provides deep coverage of CpG islands at single-base resolution [26].

Oxidative Bisulfite Sequencing (oxBS-Seq): By incorporating an initial oxidation step that converts 5hmC to 5-formylcytosine (5fC), which subsequently undergoes bisulfite-mediated deamination to uracil, oxBS-Seq enables precise discrimination between 5mC and 5hmC at single-base resolution [27] [26].

Single-Cell BS-Seq (scBS-Seq): Adapted from PBAT protocols, scBS-Seq enables methylation profiling of individual cells, revealing epigenetic heterogeneity within cellular populations that is masked in bulk tissue analyses. This approach typically involves multiple rounds of random priming and amplification to generate sufficient material from minute starting DNA [26].

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline

The computational analysis of WGBS data presents unique challenges due to the reduced sequence complexity resulting from C-to-T conversions. A robust bioinformatics pipeline must address these challenges through specialized tools and algorithms:

Table 2: WGBS Bioinformatics Pipeline Components and Tools

| Analysis Step | Key Considerations | Representative Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control & Trimming | Assessment of bisulfite conversion efficiency, adapter contamination, sequence quality | FastQC, Trim Galore!, Cutadapt |

| Alignment | Specific mapping to account for C-T mismatches; requires specialized bisulfite-aware aligners | Bismark, BSMAP, BS-Seeker2 |

| Methylation Calling | Quantitative determination of methylation levels at each cytosine; calculation of methylation ratios | MethylDackel, Bismark methylation extractor |

| Differential Methylation Analysis | Identification of DMRs (differentially methylated regions) and DMLs (differentially methylated loci) | methylKit, DSS, Metilene |

| Functional Annotation | Integration of methylation data with genomic features and functional elements | ChIPseeker, annotatr |

The alignment phase represents a particularly critical computational challenge, as conventional alignment algorithms struggle with the reduced sequence complexity of bisulfite-converted DNA. Specialized bisulfite-aware aligners employ strategies such as in silico conversion of reference sequences to align against all possible conversion outcomes. Following alignment, methylation ratios are calculated for each cytosine position as the number of reads containing C divided by the total reads covering that position (C/(C+T)), providing a quantitative measure of methylation levels ranging from 0 (completely unmethylated) to 1 (completely methylated) [24].

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the WGBS data analysis pipeline:

Research Applications and Case Studies

Cancer Research and Biomarker Discovery

WGBS has revolutionized cancer epigenomics by enabling comprehensive profiling of methylation alterations in tumorigenesis. In a landmark study published in Nature Communications (2024), researchers employed WGBS to analyze cell-free DNA (cfDNA) methylomes from 460 individuals with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) or precancerous lesions alongside matched healthy controls [29]. Through their developed Extended Multimodal Analysis (EMMA) framework, which integrated differentially methylated regions (DMRs), copy number variations (CNVs), and fragment features, they achieved exceptional diagnostic performance with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.99. The WGBS analysis detected methylation markers in 70% of ESCC cases and 50% of precancerous lesions, demonstrating the exceptional sensitivity of methylation-based early cancer detection [29].

Another comprehensive WGBS analysis of 45 esophageal samples (including ESCC, esophageal adenocarcinoma, and non-malignant tissues) revealed both cell-type-specific and cancer-specific epigenetic regulation through the identification of partially methylated domains (PMDs) and DMRs [29]. These findings highlight how WGBS can disentangle the complex epigenetic landscape of cancer, providing insights into tumor heterogeneity and molecular subtypes that inform precision oncology approaches.

Developmental Biology and Stem Cell Research

WGBS has been instrumental in elucidating the dynamic DNA methylation reprogramming events during early embryonic development. A groundbreaking 2024 study in Nature Communications utilized WGBS in a mouse model to investigate the role of Pramel15 in zygotic nuclear DNMT1 degradation and DNA demethylation [29]. Through comparative WGBS analysis of MII oocytes, zygotes, and 2-cell embryos from wild-type and Pramel15-deficient mice, researchers discovered that Pramel15 interacts with the RFTS domain of DNMT1 and regulates its stability through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Pramel15 deficiency resulted in significantly increased DNA methylation levels, particularly in regions enriched with H3K9me3, demonstrating how WGBS can uncover the precise mechanisms governing epigenetic reprogramming in development [29].

Neuroscience and Neurodegenerative Disorders

The application of WGBS to neuroscience research has opened new avenues for understanding the epigenetic basis of neurological function and disease. A 2025 study in Cell Bioscience employed WGBS to profile cell-free DNA (cfDNA) methylation patterns in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients [29]. The research identified 1,045 differentially methylated regions (DMRs) in gene bodies, promoters, and intergenic regions in ALS patients compared to controls. These DMRs were associated with key ALS pathways including endocytosis and cell adhesion. Integrated analysis with spinal cord transcriptomics revealed that 31% of DMR-associated genes showed differential expression in ALS patients, with over 20 genes significantly correlating with disease duration [29]. This innovative approach demonstrates how WGBS of cfDNA can provide non-invasive insights into epigenetic dysregulation in neurodegenerative diseases, potentially serving as a biomarker for disease progression and treatment response.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of WGBS requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for bisulfite-based applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for WGBS Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracils | Critical for complete conversion while minimizing DNA degradation; commercial kits ensure reproducibility |

| Methylated Adapters | Platform-specific adapters for library preparation | Must be pre-methylated to prevent bias against unmethylated sequences during amplification |

| DNA Polymerase for Bisulfite-Treated DNA | Amplification of converted DNA | Must lack CpG site bias and efficiently amplify uracil-rich templates |

| Bisulfite Conversion Control DNA | Quality control for conversion efficiency | Typically includes fully methylated and unmethylated standards to validate conversion rates |

| Size Selection Beads | Library fragment size selection | Magnetic beads enable precise size selection to optimize library diversity and sequencing efficiency |

| High-Sensitivity DNA Assay Kits | Quantification of library DNA | Fluorometric methods provide accurate quantification of low-concentration bisulfite-converted libraries |

| Bisulfite-Aware Alignment Software | Bioinformatics processing | Specialized algorithms account for C-T conversions during sequence alignment to reference genomes |

Technical Limitations and Emerging Solutions

Despite its status as the gold standard, WGBS presents several technical challenges that researchers must consider in experimental design:

DNA Degradation and Input Requirements: Bisulfite treatment causes substantial DNA fragmentation and degradation, with estimates reaching 90% DNA loss [26]. While traditional protocols required microgram quantities of input DNA, emerging methods like T-WGBS and PBAT have reduced input requirements to nanogram levels, enabling applications to precious clinical samples and limited cell populations [24] [26].

Sequence Complexity and Alignment Challenges: The bisulfite-induced C-to-T conversions reduce sequence complexity, complicating alignment to reference genomes. Approximately 10% of CpG sites may be difficult to align after conversion, potentially introducing mapping biases [26]. Bioinformatics solutions continue to evolve, with newer aligners demonstrating improved performance with bisulfite-converted sequences.

Inability to Distinguish 5mC from 5hmC: Conventional bisulfite treatment cannot differentiate between 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), as both resist conversion [27] [26]. Solutions like oxBS-Seq or enzymatic conversion methods (EM-seq) address this limitation but add complexity and cost to the workflow.

Cost and Computational Resources: Comprehensive genome-wide coverage requires substantial sequencing depth (typically 30x for mammalian genomes), making large-scale studies resource-intensive [23]. The computational infrastructure for storing and analyzing terabyte-scale WGBS datasets presents additional challenges, though decreasing sequencing costs and cloud-based solutions are improving accessibility.

Emerging technologies like the Illumina 5-base solution offer promising alternatives that directly detect 5mC without damaging bisulfite conversion, potentially addressing several limitations of conventional WGBS while maintaining single-base resolution [26]. Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches with WGBS data is enhancing biomarker discovery and enabling the development of sophisticated diagnostic models with improved sensitivity and specificity for clinical applications [25].

Long-read sequencing technologies, particularly those developed by Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), have revolutionized genomics research by enabling the analysis of DNA and RNA fragments thousands to millions of bases long in a single read [30]. Unlike short-read sequencing platforms, which typically produce reads of a few hundred base pairs, these single-molecule technologies provide unprecedented access to comprehensive structural, epigenetic, and transcriptional data [31]. This capability is particularly valuable for DNA methylation research, where understanding the genomic context of epigenetic modifications is essential for unraveling their role in gene regulation, cellular differentiation, and disease mechanisms [4].

The fundamental advantage of single-molecule sequencing lies in its ability to analyze individual DNA or RNA molecules in real-time without the need for pre-amplification, thereby eliminating PCR-induced biases that particularly affect regions with extreme GC content or repetitive elements [31]. Both ONT and PacBio platforms can detect DNA methylation and other base modifications natively, without the chemical conversions required by bisulfite sequencing methods that can fragment DNA and introduce biases [4] [32]. This technical overview examines the core technologies, performance characteristics, and experimental methodologies for both platforms within the specific context of genome-wide DNA methylation pattern research.

Core Technology Platforms

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT)

Fundamental Principles and Evolution

ONT's sequencing technology is based on the principle of passing DNA strands through protein nanopores embedded in a synthetic membrane while measuring changes in electrical current as individual bases pass through the pore [33] [31]. The concept was first documented in 1989, with the commercial MinION sequencer launched in 2014 [33]. The core innovation involves threaded DNA molecules through protein nanopores, differentiating between purine and pyrimidine bases using current blockade signals, and controlling DNA movement through the nanopore using phi29 DNA Polymerase [33].

Key technological milestones include the development of the R9.4.1 flow cell with a single sensor per pore, and the more recent R10.4.1 flow cell featuring a longer barrel with dual reader heads that capture two current perturbations as DNA passes through, significantly improving accuracy in homopolymer regions [33] [34]. ONT has continuously improved nanopore proteins, motor proteins, and library preparation chemistry, with recent "Q20+" chemistry enabling raw read accuracy exceeding 99% (Q20) [33].

Platform Portfolio and Specifications

ONT offers a scalable instrument portfolio ranging from portable devices to high-throughput systems:

- MinION: A compact, portable device ideal for field sequencing and rapid pathogen detection [30].

- GridION: Allows simultaneous sequencing of five MinION flow cells for increased throughput [33].

- PromethION: An ultra-high throughput platform utilizing flow cells with 3,000 channels each, supporting up to 48 flow cells simultaneously and producing several terabases of data per experiment [33].

Table 1: Oxford Nanopore Technology Specifications for Methylation Analysis

| Feature | Specifications | Relevance to Methylation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | Ultra-long (up to 1 Mb+) [30] | Spans repetitive regions and complete amplicons |

| Accuracy | R10.4.1: >99% raw read accuracy (Q20) [33] | Reliable base calling for methylation context |

| Methylation Detection | Direct detection via current deviations [4] | Identifies 5mC, 5hmC without conversion |

| Throughput | MinION: 15-30 Gb; PromethION: Tb range [33] | Scalable for population epigenomic studies |

| Real-time Analysis | Yes [30] | Immediate data access and adaptive sampling |

Pacific Biosciences (PacBio)

Fundamental Principles and Evolution

PacBio's Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing technology employs zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs)—picoliter-sized wells that function as individual reaction chambers to observe a single molecule of DNA polymerase [31]. The system immobilizes polymerase at the bottom of each ZMW and introduces fluorescently labeled deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs). As the polymerase incorporates nucleotides into the complementary DNA strand, it generates unique fluorescent signals captured in real-time [31].

A significant advancement in PacBio's technology is the development of HiFi (High-Fidelity) reads using Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS). This approach involves circularizing DNA molecules, then repeatedly sequencing the circular template with the polymerase [31]. The resulting subreads are computationally processed using an internal consensus algorithm that dramatically reduces random sequencing errors while retaining long read lengths [31]. The kinetic information captured during nucleotide incorporation, specifically the interpulse duration (IPD), provides data for direct epigenetic profiling without additional chemical treatments or separate workflows [32] [31].

Platform Portfolio and Specifications

PacBio's current sequencing systems include:

- Revio: A high-throughput system designed for population-scale studies.

- Vega: Offers flexibility for various throughput needs.

Both systems support HiFi sequencing, which provides simultaneous readout of the genome and epigenome from native DNA without chemical conversion, additional sample preparation, or parallel workflows [35]. Recent developments include licensing the Holistic Kinetic Model 2 (HK2) from CUHK, which enhances detection of 5hmC and hemimethylated 5mC through an AI deep learning framework that integrates convolutional and transformer layers to model local and long-range kinetic features [35].

Table 2: Pacific Biosciences Technology Specifications for Methylation Analysis

| Feature | Specifications | Relevance to Methylation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | Long (HiFi reads ~15 kb) [30] | Excellent for structural variant context |

| Accuracy | Very high (HiFi Q20-Q30+) [30] | Precision variant calling and methylation detection |

| Methylation Detection | Kinetic analysis (IPD) of native DNA [31] | Detects 5mC, 6mA; 5hmC with HK2 [35] |

| Throughput | High throughput on Revio/Vega [32] | Suitable for large cohort epigenomic studies |

| Real-time Analysis | Fast, but not real-time [30] | Rapid turnaround for clinical applications |

Performance Comparison for Methylation Analysis

Technical Capabilities and Limitations

Direct comparisons between sequencing platforms reveal distinct strengths and limitations for DNA methylation research. A 2025 comparative evaluation of DNA methylation detection approaches assessed whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS), Illumina methylation microarray (EPIC), enzymatic methyl-sequencing (EM-seq), and ONT sequencing across human genome samples from tissue, cell lines, and whole blood [4]. While EM-seq showed the highest concordance with WGBS, ONT sequencing captured certain loci uniquely and enabled methylation detection in challenging genomic regions that are problematic for bisulfite-based methods [4].

PacBio HiFi sequencing has demonstrated advantages in coverage uniformity and comprehensiveness compared to WGBS. In a twin cohort study, HiFi sequencing identified approximately 5.6 million more CpG sites than WGBS, particularly in repetitive elements and regions of low WGBS coverage [32]. Coverage patterns differed markedly: PacBio HiFi showed a unimodal symmetric pattern peaking at 28-30×, indicating uniform coverage, while WGBS datasets displayed right-skewed distributions with the majority of CpGs covered at low depth (4-10×) [32]. Over 90% of CpGs in the PacBio HiFi dataset had ≥10× coverage, compared to approximately 65% in the WGBS dataset [32].

Accuracy and Concordance in Methylation Detection

ONT sequencing demonstrates high reliability for methylation detection, with R10.4.1 chemistry showing a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.868 against bisulfite sequencing data, compared to 0.839 for R9.4.1 chemistry [34]. Direct comparison between R9 and R10 chemistries shows high concordance, with WT replicates exhibiting a Pearson correlation of 0.9185 and KO replicates correlating at 0.9194 [34]. Specifically, R9 WT and R10 WT methylation data had 72.00% of methylation sites with ≤10% difference in methylation percentage, while R9 KO and R10 KO had 72.67% of sites with similarly small differences [34].

Both ONT chemistries exhibit some detection bias for methylation, with cross-chemistry comparisons showing lower correlation values (0.8432 for R9 WT against R10 KO vs. 0.8612 for R9 WT against R9 KO) [34]. This indicates that methylation differences across ONT sequencing chemistries can substantially affect differential methylation investigations across conditions. Discordant methylation sites between chemistries tend to cluster in specific genomic contexts, requiring careful interpretation in cross-study comparisons [34].

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

Successful methylation analysis with long-read technologies requires careful sample preparation and library construction. For ONT sequencing, the standard protocol involves:

DNA Extraction: Use high-molecular-weight DNA extraction methods such as the Nanobind Tissue Big DNA Kit (Circulomics) or similar approaches that preserve long DNA fragments [34]. DNA purity should be assessed using NanoDrop 260/280 and 260/230 ratios, with quantification via fluorometric methods (Qubit) [4].

Library Preparation: ONT offers both 1D and sequencing kits. Recent advancements have phased out the 2D library preparation method in favor of 1D library preparation where each strand of dsDNA is sequenced independently, providing an optimal balance between accuracy and throughput [33]. The procedure typically involves DNA repair and end-prep, adapter ligation, and purification steps.

Sequencing: Utilize either R9.4.1 or R10.4.1 flow cells depending on project requirements. R10.4.1 chemistry is particularly advantageous for methylation studies in repetitive regions due to improved basecalling in homopolymers [33] [34].

For PacBio HiFi sequencing for methylation analysis:

DNA Extraction: Similar to ONT, obtain high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA. The recently introduced SMRTbell prep kit 3.0 reduces time by 50%, cost, and DNA quantity requirements by 40% while maintaining assembly quality [36].

Library Preparation: Construct SMRTbell libraries through DNA repair, end-polishing, adapter ligation, and purification. The process is amenable to automation for higher throughput applications [36].

Sequencing: Perform sequencing on Revio or Vega systems with polymerase binding and diffusion optimization. The HK2 model enhancement for improved 5hmC and hemimethylation detection will be delivered through software updates without changes to sequencing protocols [35].

Data Processing and Methylation Analysis

ONT Data Analysis Workflow

The standard ONT methylation analysis workflow involves several key steps [34]:

Basecalling: Use ONT's Dorado basecaller (version 7.2.13 or newer) for converting raw FAST5 signal data to nucleotide sequences. Dorado performs basecalling and methylation calling simultaneously, detecting 5mC modifications from the raw electrical signals.

Read Alignment: Map sequences to a reference genome using minimap2 or similar long-read aligners. This produces BAM files containing both sequence alignment information and methylation tags [34].

Methylation Profiling: Process aligned BAM files using modbam2bed or similar tools to generate whole-genome methylation profiles [34]. modbam2bed summarizes methylation states at each CpG site, calculating coverage and methylation percentages.

Coverage and Methylation Calculation: Apply appropriate coverage filters (typically ≥10×) to ensure statistical reliability [34]. Different methods for calculating coverage and methylation percentages can impact results, requiring consistent approaches across comparisons.

PacBio Data Analysis Workflow

The PacBio methylation analysis workflow leverages kinetic information [32] [35]:

HiFi Read Generation: Process subreads from circular consensus sequencing to generate highly accurate HiFi reads. This involves computational correction of random errors through multiple passes of the same DNA molecule.

Variant Calling: Identify genetic variants using standard tools optimized for long reads. The high accuracy of HiFi reads enables precise SNP and indel detection alongside epigenetic marks.

Kinetic Analysis: Extract interpulse duration (IPD) metrics from the sequencing data. The HK2 model uses convolutional and transformer layers to analyze local and long-range kinetic features for detecting 5mC, 6mA, and 5hmC modifications [35].

Integrated Analysis: Correlate methylation patterns with genetic variants and genomic features. The uniform coverage of HiFi sequencing enables de novo DNA methylation analysis, reporting CpG sites beyond reference sequences [32].

Research Reagent Solutions and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Long-Read Methylation Analysis

| Category | Specific Products/Tools | Function in Methylation Research |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Nanobind Tissue Big DNA Kit (Circulomics) [34], DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) [4] | Obtain high-molecular-weight DNA preserving long-range epigenetic information |

| Library Prep Kits | ONT Ligation Sequencing Kits [33], PacBio SMRTbell prep kit 3.0 [36] | Prepare DNA for sequencing with minimal bias for epigenetic marks |

| Basecalling Software | Dorado (ONT) [34], SMRT Link (PacBio) | Convert raw signals to base sequences while calling modifications |

| Alignment Tools | minimap2 [34] | Map long reads to reference genomes |

| Methylation Callers | modbam2bed [34], HK2 model (PacBio) [35] | Identify and quantify methylation states from sequencing data |

| Quality Control | NanoDrop, Qubit fluorometer [4] | Assess DNA quality and quantity before library preparation |

Oxford Nanopore and PacBio sequencing technologies offer powerful, complementary approaches for genome-wide DNA methylation research. ONT provides unique advantages in read length, portability, and real-time analysis, with recent R10.4.1 chemistry significantly improving accuracy, particularly in homopolymer regions problematic for methylation studies [33] [34]. PacBio's HiFi sequencing delivers exceptional base-level accuracy and uniform coverage that enables detection of millions more CpG sites than bisulfite-based methods, especially in repetitive regions [32]. The emerging capability to detect 5hmC and hemimethylated sites through kinetic analysis advancements further enhances its utility for comprehensive epigenomic profiling [35].

For researchers investigating DNA methylation patterns, platform selection depends on specific project requirements: ONT excels in applications requiring ultra-long reads, portability, or real-time analysis, while PacBio offers advantages for applications demanding the highest base-level accuracy and uniform coverage across CpG-rich regions [30]. Both technologies continue to evolve rapidly, with ongoing improvements in accuracy, throughput, and methylation detection capabilities promising to further transform our understanding of epigenomic regulation in health and disease.

DNA methylation represents a fundamental epigenetic mechanism that regulates mammalian cellular differentiation, gene expression, and disease states without altering the underlying DNA sequence [37]. In traditional bulk sequencing approaches, DNA methylation patterns are averaged across thousands or millions of cells, obscuring cell-to-cell epigenetic heterogeneity that drives developmental processes, disease progression, and therapeutic responses. The emergence of single-cell methylation profiling technologies has revolutionized our capacity to mine genome-wide epigenetic patterns at unprecedented resolution, enabling researchers to deconvolve mixed cell populations and identify rare cell types based on their distinctive methylation signatures [38].

Among the arsenal of single-cell epigenomic tools, single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS-seq) and single-cell reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (scRRBS) have emerged as powerful techniques for base-resolution mapping of DNA methylation landscapes in individual cells [37] [39]. These methods have proven particularly valuable for investigating cellular heterogeneity in complex tissues, embryonic development, cancer evolution, and neurological systems where epigenetic variation drives functional diversity [38] [40]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these cornerstone methodologies, their experimental workflows, analytical considerations, and applications within the broader context of genome-wide DNA methylation data mining research.

Fundamental Principles of DNA Methylation Analysis

In mammalian genomes, DNA methylation occurs predominantly through the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of cytosine residues (5-methylcytosine) within CpG dinucleotides [37]. While non-CpG methylation occurs in specific biological contexts such as neuronal cells and stem cells, approximately 60-80% of the 28 million CpG sites in the human genome are typically methylated [37]. The distribution of CpGs throughout the genome is non-random, with dense clusters known as CpG islands (CGIs) frequently occurring near gene promoters and serving as crucial regulatory platforms for transcription [37].

The functional consequences of DNA methylation depend strongly on genomic context. Promoter methylation typically correlates with gene repression, playing essential roles in genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, and silencing of retroviral elements [37]. In contrast, gene body methylation often associates with transcriptional activity, suggesting complex context-dependent regulatory functions [37]. This nuanced relationship underscores the importance of genome-wide methylation mapping rather than targeted approaches that might miss functionally significant epigenetic events.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of DNA Methylation in Mammalian Genomes

| Feature | Description | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Site | Cytosine in CpG dinucleotides | Major epigenetic modification |

| Genomic Distribution | 28 million sites in human genome; 60-80% methylated | Widespread regulatory potential |

| CpG Islands | ~1% of genome; dense CpG regions near promoters | Key regulatory platforms for transcription |

| Promoter Methylation | Often repressive | Gene silencing, imprinting, X-inactivation |

| Gene Body Methylation | Often permissive | Correlates with transcriptional activity |

Technical Approaches to Single-Cell Methylation Profiling

Bisulfite Conversion: The Foundation of Methylation Detection

Bisulfite conversion represents the gold standard for DNA methylation profiling, achieving single-base resolution through selective chemical modification of unmethylated cytosines [37] [26]. When genomic DNA is treated with sodium bisulfite, unmethylated cytosines undergo deamination to uracils, which are subsequently amplified as thymines during PCR. In contrast, methylated cytosines remain protected from conversion and are read as cytosines after sequencing [26]. The resulting sequence differences allow absolute quantification of methylation status at individual cytosine residues through comparison of converted and unconverted sequences.

Despite its widespread adoption, bisulfite conversion presents several technical challenges, particularly in single-cell applications. The reaction conditions cause substantial DNA degradation (up to 90% loss) and reduce sequence complexity through C-to-T conversions, complicating subsequent alignment to reference genomes [37] [26]. To mitigate these limitations, post-bisulfite adaptor tagging (PBAT) approaches perform adaptor ligation after bisulfite conversion, thereby minimizing loss of fragmented DNA during library preparation [37] [38]. This modification has proven particularly valuable for single-cell workflows where starting material is extremely limited.

scBS-seq: Comprehensive Genome-Wide Methylation Mapping

Single-cell bisulfite sequencing (scBS-seq) provides unbiased whole-genome methylation mapping through a PBAT-based approach that maximizes coverage while minimizing material loss [38]. In this method, bisulfite treatment simultaneously fragments DNA and converts unmethylated cytosines, followed by multiple rounds of random priming using oligonucleotides containing Illumina adapter sequences [38]. The method captures digitized methylation patterns from individual cells, with approximately 48.4% of CpGs detectable per cell at saturating sequencing depths [38].

The scBS-seq protocol involves several critical steps that ensure high-quality data from minimal input. After bisulfite conversion and fragmentation, complementary strand synthesis is primed using custom oligos with Illumina adapter sequences and 3' random nonamers, repeated five times to tag maximum DNA strands [38]. Following capture of tagged strands, the second adapter is integrated similarly, with final PCR amplification using indexed primers for multiplexing [38]. This workflow typically yields information for 3.7 million CpGs per cell (range: 1.8M-7.7M), representing approximately 17.7% of all CpGs genome-wide [38].

scBS-seq Experimental Workflow: The comprehensive whole-genome approach begins with single-cell isolation and bisulfite conversion, followed by library construction through multiple rounds of random priming and amplification.

scRRBS: Targeted Profiling of Informative CpG-Rich Regions

Single-cell reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (scRRBS) offers a cost-effective alternative that focuses on CpG-rich genomic regions likely to contain the most biologically informative methylation changes [37] [39]. This method utilizes restriction enzymes (typically MspI) to selectively digest genomic DNA at CCGG sites, generating fragments enriched for promoters, CpG islands, and other regulatory elements [39] [11]. Following digestion, fragments undergo size selection, bisulfite conversion, and library preparation in a single-tube reaction that minimizes handling losses [39].

The strategic enzymatic digestion enables scRRBS to profile approximately 1 million CpG sites per diploid mammalian cell, with particular enrichment in CpG islands and gene promoters [39]. While this represents only 10-15% of all genomic CpGs, the targeted regions include the majority of dynamically regulated methylation sites with known regulatory functions [11] [26]. The efficiency and lower per-cell cost of scRRBS make it particularly suitable for larger-scale studies where cellular throughput must be balanced with genomic coverage.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of scBS-seq and scRRBS Methodologies

| Parameter | scBS-seq | scRRBS |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | Whole-genome (~48.4% of CpGs) | Targeted (~1 million CpGs/cell) |

| CpG Island Coverage | Comprehensive but unbiased | Enriched (focus on informative regions) |

| Key Steps | PBAT, random priming | Restriction digest, size selection |

| Sequencing Depth | Higher (15-20M reads/cell) | Lower (1-5M reads/cell) |

| Cost per Cell | Higher | Lower |

| Primary Advantage | Unbiased genome-wide data | Cost-effective for large studies |

| Primary Limitation | Higher cost per cell | Misses non-CpG island regulation |

| Ideal Application | Discovery studies, heterogeneous populations | Focused studies, larger sample sizes |

scRRBS Experimental Workflow: The targeted approach begins with restriction enzyme digestion to enrich for informative genomic regions, followed by size selection and bisulfite conversion before library construction.

Analytical Frameworks for Single-Cell Methylation Data

Data Processing and Quality Control

The analysis of single-cell bisulfite sequencing data requires specialized computational approaches that address its unique characteristics, including sparsity, binary nature, and technical artifacts [41]. Initial processing typically involves alignment to a reference genome using bisulfite-aware tools such as Bismark or BSMAP, followed by methylation calling at individual cytosine positions [37] [38]. Critical quality control metrics include bisulfite conversion efficiency (typically >97-99%, measured via non-CpG cytosine conversion), mapping efficiency, and coverage distribution across genomic contexts [38] [40].