Optimized ChIP-seq for Histone Modifications: A Complete Guide from Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) for histone modification analysis.

Optimized ChIP-seq for Histone Modifications: A Complete Guide from Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) for histone modification analysis. It covers foundational epigenetic principles, detailed methodological protocols for diverse sample types including challenging solid tissues, systematic troubleshooting for common issues like high background and low signal, and rigorous data validation standards as defined by the ENCODE consortium. The content integrates the latest refinements in tissue processing, low-input methods such as carrier ChIP-seq, and differential analysis tools to enable robust, reproducible epigenomic profiling in both basic research and clinical contexts.

Understanding Histone Modifications and ChIP-seq Fundamentals

The Biochemical Language of the Histone Code

The concept of an "epigenetic landscape" was first introduced by embryologist Conrad Waddington in 1942 to describe how genes interact with their environment to bring about phenotypic outcomes during development [1]. Today, epigenetics is understood as the study of heritable changes in gene expression that do not involve alterations to the underlying DNA sequence. The histone code represents a crucial epigenetic mechanism wherein chemical modifications to histone proteins serve as a sophisticated biochemical language that regulates chromatin structure and genome function.

Histones are the fundamental protein components of chromatin, around which DNA is wrapped to form nucleosomes—the basic repeating units of chromatin structure. Each nucleosome consists of an octamer of core histone proteins (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) [1]. The N-terminal tails of these histones extend outward from the nucleosome core, serving as platforms for diverse post-translational modifications (PTMs) including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, and SUMOylation [2] [1].

These modifications mediate their effects through two primary mechanisms: by altering the electrostatic charge of histones, thereby changing chromatin structure and DNA-binding properties; or by creating docking sites for protein recognition modules that recruit chromatin-modifying complexes [2]. Specific histone modifications are associated with distinct chromatin states and functions—H3K27ac and H3K4me3 typically mark active promoters and enhancers, while H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 characterize repressed heterochromatic regions [1]. The dysregulation of these modification patterns is implicated in various human diseases, including cancer, making their precise mapping essential for understanding both normal development and disease pathogenesis [2] [1].

Advanced Sequencing Technologies for Mapping the Histone Code

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Followed by Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

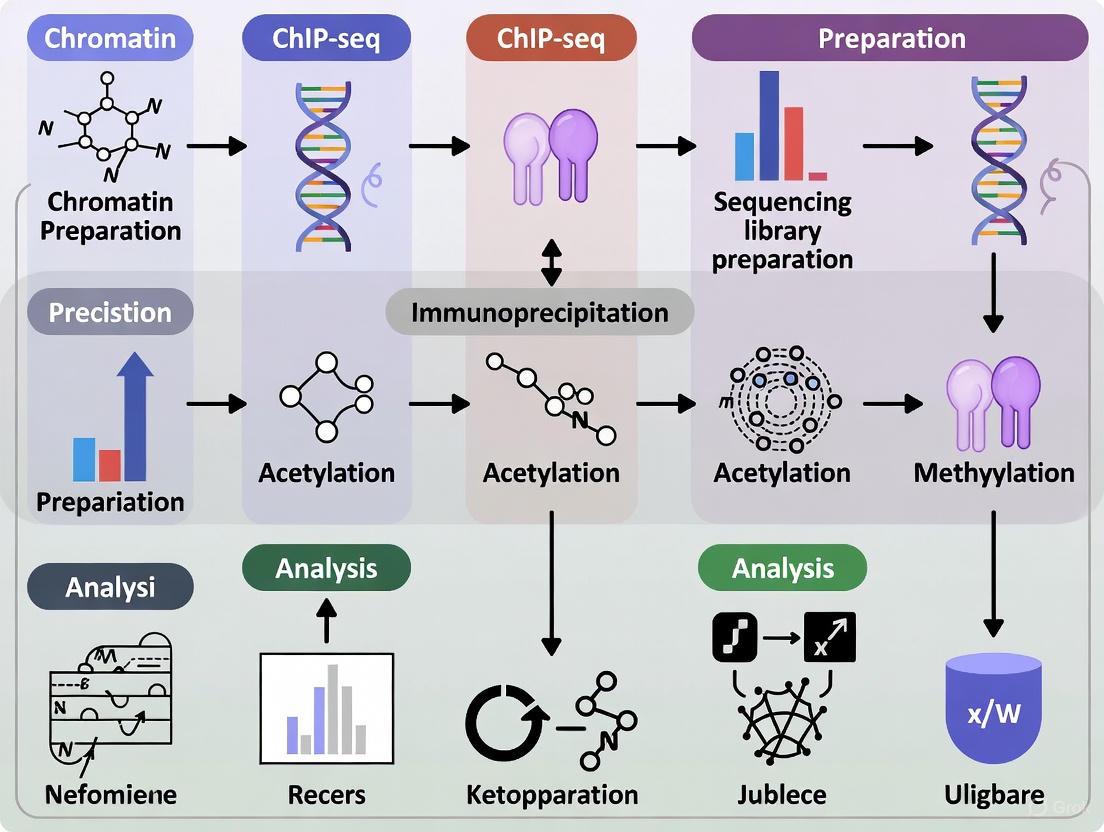

ChIP-seq has served as the cornerstone technique for genome-wide mapping of histone modifications since its development in 2007 [1]. The standard protocol involves: (1) cross-linking proteins to DNA using formaldehyde; (2) chromatin fragmentation by sonication or enzymatic digestion; (3) immunoprecipitation with modification-specific antibodies; (4) DNA purification and library preparation; and (5) high-throughput sequencing [3]. Despite its widespread adoption, traditional ChIP-seq faces limitations including substantial input requirements, cross-linking artifacts, and background noise from antibody nonspecificity [1].

Recent methodological advances have substantially improved the resolution, specificity, and quantitative capabilities of histone modification mapping:

Table 1: Advanced Methods for Histone Modification Mapping

| Method | Key Features | Advantages Over Traditional ChIP-seq | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MINUTE-ChIP [4] | Multiplexed barcoding before IP | Enables quantitative comparison of 12 samples simultaneously; eliminates experimental variation | High-throughput screening across multiple conditions |

| CUT&Tag [1] | Antibody-targeted tagmentation | Higher resolution (~20 bp); lower background; suitable for single-cell analysis | Mapping histone modifications in rare cell populations |

| CUT&RUN [1] | Antibody-guided MNase cleavage | In situ mapping; minimal background; requires fewer cells | Mapping histone marks in low-input samples |

| dxChIP-seq [5] | Double-crosslinking protocol | Enhanced detection of indirect chromatin binders; improved signal-to-noise ratio | Challenging chromatin factors and complex tissues |

| ChIP-nexus [6] | Exonuclease digestion with efficient circularization | Near nucleotide resolution; minimal amplification artifacts | Precise transcription factor footprinting alongside histones |

Quantitative Normalization Strategies for ChIP-seq

A significant challenge in comparative ChIP-seq analysis is the normalization of signals across samples to enable meaningful biological interpretations. Spike-in normalization, which involves adding exogenous chromatin from a different species as a quantitative reference, has been widely used but shows limitations in reliability and mathematical rigor [7].

The recently developed siQ-ChIP (sans spike-in quantitative ChIP) method provides an alternative approach that measures absolute immunoprecipitation efficiency genome-wide without requiring exogenous controls [7]. This method explicitly accounts for critical experimental factors including antibody behavior, chromatin fragmentation efficiency, and input DNA quantification—reinforcing fundamental ChIP-seq best practices while providing mathematically robust normalization.

Optimized ChIP-seq Protocol for Histone Modifications

Sample Preparation and Chromatin Fragmentation

The foundation of successful ChIP-seq begins with proper sample preparation. For histone modifications, the protocol can be performed on either native or cross-linked chromatin, with specific considerations for each approach [4]. The double-crosslinking dxChIP-seq protocol has demonstrated particular utility for challenging chromatin targets, employing sequential crosslinking with disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG) followed by formaldehyde to stabilize both direct and indirect protein-DNA interactions [5].

Critical Step: Chromatin Fragmentation

- Sonication: Applied to cross-linked samples; produces random fragments of 100-300 bp [3]. Optimal for transcription factors and histone marks in linker regions.

- Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) Digestion: Preferentially degrades linker DNA, yielding uniform mononucleosome-sized fragments (∼147 bp) [8]. Provides higher resolution for nucleosome-positioned histone modifications.

Immunoprecipitation and Library Preparation

Antibody specificity remains the most critical factor determining ChIP-seq success. The ENCODE consortium has established rigorous validation guidelines requiring that the primary reactive band in immunoblot analyses contains at least 50% of the total signal, ideally corresponding to the expected size of the target protein or modification [3].

The MINUTE-ChIP protocol introduces a revolutionary approach by barcoding chromatin samples from different conditions before immunoprecipitation, enabling multiplexed processing of up to 12 samples in parallel [4]. This strategy not only increases throughput but also eliminates inter-experimental variability, allowing for precise quantitative comparisons across conditions.

For library preparation, the ChIP-nexus protocol significantly improves mapping resolution by incorporating a unique barcoding system and efficient DNA circularization step, requiring only one successful ligation per DNA fragment rather than the two needed in conventional protocols [6]. This results in higher quality libraries with reduced amplification artifacts.

Computational Analysis and Differential Binding

The analysis of ChIP-seq data requires specialized computational tools tailored to different biological questions. A comprehensive assessment of 33 differential ChIP-seq analysis tools revealed that performance is strongly dependent on peak characteristics and biological context [9].

Table 2: Computational Tools for Differential ChIP-seq Analysis

| Tool Category | Representative Tools | Optimal Use Cases | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak-dependent Tools | bdgdiff (MACS2), MEDIPS, PePr | Transcription factors, sharp histone marks (H3K4me3, H3K27ac) | Require external peak calling; performance affected by peak size |

| Peak-independent Tools | csaw, GenoGAM | Broad histone marks (H3K27me3, H3K36me3) | Handle peak calling internally; more consistent across peak types |

| Scenario-specific Tools | NarrowPeaks, uniquepeaks | Global changes (e.g., inhibitor treatments) | Performance varies by regulation scenario (50:50 vs. 100:0 changes) |

Tools such as bdgdiff (MACS2), MEDIPS, and PePr have demonstrated the highest median performance across diverse scenarios, though optimal tool selection should be guided by the specific biological question and the expected binding pattern changes [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ChIP-seq Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crosslinking Agents | Formaldehyde, Disuccinimidyl Glutarate (DSG) | Stabilize protein-DNA interactions | Double-crosslinking (dxChIP-seq) enhances indirect binding detection [5] |

| Chromatin Fragmentation Reagents | Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase), Sonication systems | Fragment chromatin to appropriate size | MNase preferred for histone modifications; sonication for transcription factors [8] |

| Validated Antibodies | H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K27me3, H3K9me3 | Specific enrichment of target epitopes | Require rigorous validation; ≥50% specific signal in immunoblots [3] |

| Barcoding Adapters | MINUTE-ChIP barcodes, Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Sample multiplexing and PCR duplicate removal | Enable multiplexed quantitative comparisons [4] |

| Spike-in Controls | S. pombe chromatin, Drosophila chromatin | Normalization reference for quantitative comparisons | Limitations in reliability; siQ-ChIP provides mathematical alternative [7] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina-compatible, Tn5-based tagmentation | Preparation of sequencing libraries | ChIP-nexus improves efficiency via circularization [6] |

Future Perspectives in Histone Code Research

The field of epigenetic mapping continues to evolve with emerging technologies that promise to overcome current limitations. Third-generation sequencing platforms offer potential solutions for long-read epigenetic analysis but still face challenges in accuracy and cost-effectiveness compared to next-generation sequencing [1]. The development of antibody-free approaches for base-resolution mapping of histone modifications represents an exciting frontier that could eliminate the specificity issues inherent to antibody-based methods.

The integration of multiplexed quantitative approaches like MINUTE-ChIP with advanced normalization strategies such as siQ-ChIP provides a powerful framework for future studies of the histone code [4] [7]. As these technologies mature, they will enable increasingly sophisticated investigations into how combinatorial histone modification patterns regulate gene expression programs in development, physiology, and disease—ultimately fulfilling the potential of epigenetics as a diagnostic and therapeutic target in human health.

Core Principle of Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) is an antibody-based technology used to selectively enrich specific DNA-binding proteins along with their DNA targets, providing a snapshot of protein-DNA interactions within their native chromatin context [10] [11]. This technique enables researchers to investigate a particular protein-DNA interaction, several interactions, or interactions across the entire genome, offering critical insights into gene regulatory mechanisms [10]. The fundamental principle behind ChIP involves using antibodies to isolate, or precipitate, a specific protein, histone, transcription factor, or cofactor and its bound chromatin from a protein mixture extracted from cells or tissues [10]. The immunoprecipitated DNA fragments are subsequently identified and quantified using various downstream analytical methods including quantitative PCR (qPCR), microarray (ChIP-chip), or next-generation sequencing (ChIP-seq) [12] [11].

ChIP has revolutionized our understanding of epigenetic regulation, particularly in studying post-translational modifications (PTMs) of histones that influence chromatin structure and gene expression [12] [11]. These modifications—including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination—serve as epigenetic marks that dynamically regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [12] [11]. The technique's versatility allows applications ranging from mapping transcription factor binding sites to profiling histone modifications across the genome, making it indispensable for understanding transcriptional regulation in development, disease, and normal cellular physiology [13] [14].

Core Principles and Methodology

Fundamental Workflow

The ChIP procedure follows a systematic workflow designed to preserve and capture transient protein-DNA interactions occurring in living cells. The process begins with in vivo crosslinking to stabilize these interactions, followed by cell lysis, chromatin fragmentation, immunoprecipitation with specific antibodies, and finally, analysis of the enriched DNA [12] [10]. This workflow enables researchers to obtain a snapshot of protein-DNA interactions at a specific time point under defined physiological conditions [12].

Table 1: Key Steps in the ChIP Workflow

| Step | Key Objective | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Crosslinking | Covalently stabilize protein-DNA complexes | Formaldehyde concentration and duration; requires quenching [12] |

| Cell Lysis | Dissolve membranes, liberate cellular components | Detergent-based lysis; protease/phosphatase inhibitors essential [12] |

| Chromatin Fragmentation | Shear chromatin into workable fragments | Fragment size (200-1000 bp); sonication or enzymatic digestion [12] [10] |

| Immunoprecipitation | Enrich target protein-DNA complexes | Antibody specificity and concentration; incubation time [12] [10] |

| DNA Purification | Reverse crosslinks and purify DNA | Proteinase K treatment; DNA cleanup methods [15] |

| Downstream Analysis | Identify and quantify enriched DNA | qPCR, microarray, or next-generation sequencing [10] [11] |

ChIP Variants: Native versus Crosslinked Approaches

Researchers can employ two primary ChIP variations depending on their experimental goals: crosslinked ChIP (X-ChIP) and native ChIP (N-ChIP). Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different applications [10] [11].

In X-ChIP, chemical fixatives such as formaldehyde are used to crosslink the protein of interest to DNA, preserving transient interactions [10]. Chromatin fragmentation is typically achieved through sonication or nuclease digestion [10]. The key advantage of X-ChIP is its broad applicability to both histone and non-histone proteins, including transcription factors, while minimizing the loss of chromatin proteins during extraction [10]. However, this method suffers from less efficient precipitation and requires DNA amplification for downstream analyses [10].

In contrast, N-ChIP uses unfixed chromatin isolated from cell nuclei digested with nuclease, without crosslinking agents [10] [11]. This approach offers better antibody recognition to their target antigens since antibodies are raised against unfixed epitopes [10]. While N-ChIP is ideal for studying strong histone-DNA interactions due to the inherent stability of these complexes, it is generally unsuitable for analyzing transcription factors and cofactors, as it may lead to loss of protein binding during chromatin processing [10].

Antibody Selection: The Foundation of Specificity

Antibody selection represents one of the most critical factors in ChIP experimental design [12]. The ideal antibody must recognize its target epitope in the context of crosslinked and fragmented chromatin while exhibiting minimal cross-reactivity with related epitopes [12]. For example, an antibody targeting histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylation (H3K9me2) should not significantly recognize the monomethyl (H3K9me1) or trimethyl (H3K9me3) forms, as these marks can be associated with opposing transcriptional outcomes [12].

Researchers can choose between monoclonal, oligoclonal, and polyclonal antibodies, each offering distinct advantages [12]. Monoclonal antibodies provide superior specificity but may recognize a single epitope that could be buried in crosslinked chromatin [12]. Polyclonal and oligoclonal antibodies recognize multiple epitopes, potentially increasing the chance of successful immunoprecipitation, but require thorough validation to ensure specificity [12]. For targets without suitable antibodies available, alternative approaches include tagging the target with epitopes such as Myc, His, HA, T7, GST, or V5 [12].

ChIP-Seq: Genome-Wide Mapping of Protein-DNA Interactions

From ChIP to ChIP-Seq: Technological Evolution

ChIP-sequencing (ChIP-Seq) represents the integration of chromatin immunoprecipitation with massive parallel sequencing technologies, enabling genome-wide profiling of protein-DNA interactions [15] [11]. This powerful combination provides a comprehensive snapshot of transcription factor binding sites, histone modifications, and other regulatory elements across the entire genome [15]. The method has largely superseded earlier approaches like ChIP-chip (which used microarrays) due to its higher resolution, greater coverage, reduced background noise, and increased dynamic range [15].

The ChIP-Seq process builds upon the standard ChIP protocol but incorporates additional steps to prepare sequencing libraries from the immunoprecipitated DNA [16] [13]. Following DNA purification, fragments undergo end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation to create a library compatible with next-generation sequencing platforms [16] [13]. The prepared library is then sequenced, generating millions of short reads that are subsequently aligned to a reference genome to identify regions of significant enrichment [15].

ChIP-Seq Applications in Histone Modification Research

ChIP-Seq has become the method of choice for comprehensive epigenomic studies, particularly for mapping histone modifications associated with distinct chromatin states [13]. Different histone modifications correlate with specific functional genomic elements, creating a "histone code" that influences gene expression patterns [13]. For example:

- H3K4me3 marks active gene promoters [13]

- H3K4me1 identifies transcriptional enhancers [13]

- H3K36me3 covers transcribed regions of the genome [13]

- H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 are associated with repressed chromatin states [13]

Knowing the genome-wide pattern of these histone modifications provides crucial information about cell identity and disease states [13]. The ENCODE Consortium and Roadmap Epigenomics Project have established standardized pipelines for processing histone ChIP-Seq data, enabling comparative analyses across cell types and conditions [17].

Table 2: Key Histone Modifications and Their Functional Associations

| Histone Mark | Chromatin State | Genomic Location | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Active | Promoters | Gene activation [13] |

| H3K4me1 | Active | Enhancers | Enhancer activation [13] |

| H3K9ac | Active | Promoters/Enhancers | Transcription activation [13] |

| H3K27ac | Active | Enhancers/Promoters | Active enhancers/promoters [13] |

| H3K36me3 | Active | Gene bodies | Transcriptional elongation [13] |

| H3K27me3 | Repressive | Promoters | Facultative heterochromatin [13] |

| H3K9me3 | Repressive | Constitutive heterochromatin | Transcriptional repression [13] |

Advanced ChIP-Seq Methodologies

Recent technological advancements have addressed several limitations of conventional ChIP-Seq approaches, particularly regarding quantitative comparisons and sample throughput. MINUTE-ChIP (Multiplexed Quantitative Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing) represents one such innovation, enabling profiling of multiple samples against multiple epitopes in a single workflow [18]. This multiplexed approach not only dramatically increases throughput but also facilitates accurate quantitative comparisons across conditions [18].

The MINUTE-ChIP protocol involves sample barcoding before pooling and splitting into parallel immunoprecipitation reactions, followed by preparation of next-generation sequencing libraries from both input and immunoprecipitated DNA [18]. This methodology empowers researchers to perform ChIP-Seq experiments with appropriate numbers of replicates and control conditions, delivering more statistically robust and biologically meaningful results [18].

Optimized ChIP Protocols for Histone Modification Research

Tissue-Specific Protocol Optimization

Performing ChIP assays on solid tissues presents unique technical challenges, including tissue heterogeneity, complex cell matrices, and difficulties in chromatin fragmentation [16]. Recent protocols have addressed these limitations through optimized procedures for tissue preparation, chromatin extraction, and immunoprecipitation [16] [19]. For frozen tissue samples, proper preparation begins with mincing frozen tissues under cold conditions, followed by homogenization using either a semi-automated gentleMACS Dissociator or a manual Dounce tissue grinder [16].

The refined tissue ChIP-seq protocol incorporates several key improvements: (1) simplified and efficient procedures for tissue preparation; (2) optimized chromatin extraction methods preserving tissue-specific chromatin features; (3) enhanced immunoprecipitation steps with optimized buffer composition and washing steps to minimize background; and (4) library construction compatible with multiple sequencing platforms [16]. These optimizations enable highly reproducible, sensitive, and scalable analysis of disease-relevant chromatin states in vivo, particularly valuable for cancer research using clinical specimens [16] [19].

Critical Experimental Parameters and Controls

Successful ChIP experiments require careful optimization of several key parameters and implementation of appropriate controls. Crosslinking time represents one of the most critical variables needing empirical determination, as over-fixation can reduce antigen accessibility and hinder chromatin fragmentation, while under-fixation may fail to preserve transient interactions [12] [14]. Similarly, chromatin fragmentation must be optimized to achieve ideal fragment sizes of 200-1000 base pairs, whether using sonication or enzymatic approaches [12] [10].

Essential controls for ChIP experiments include:

- No-antibody control (mock IP) for each IP performed [12]

- Positive control region known to be enriched for the target [12]

- Negative control region not expected to be enriched [12]

- Input DNA representing the whole chromatin sample before IP [12]

- Biological replicates to ensure reproducibility [17]

For ChIP-Seq experiments, the ENCODE Consortium has established specific quality standards, including library complexity metrics (NRF > 0.9, PBC1 > 0.9, PBC2 > 10) and sequencing depth requirements (20 million usable fragments per replicate for narrow histone marks, 45 million for broad marks) [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ChIP Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Crosslinking Reagents | Formaldehyde, EGS, DSG | Covalently stabilize protein-DNA interactions; formaldehyde most common [12] |

| Cell Lysis Buffers | RIPA buffer, Commercial kits | Dissolve membranes, liberate cellular components; protease inhibitors essential [12] [14] |

| Chromatin Shearing | Sonication (Bioruptor), Enzymatic (MNase) | Fragment chromatin; sonication provides random fragments, MNase gives precise nucleosomal cleavage [12] [10] |

| Specific Antibodies | H3K4me3 (CST #9751S), H3K27me3 (CST #9733S) | Target-specific immunoprecipitation; require ChIP-grade validation [13] |

| Immunoprecipitation | Protein A/G magnetic beads | Capture antibody-target complexes; magnetic beads facilitate washing steps [14] |

| DNA Purification | Phenol-chloroform, Commercial kits | Purify DNA after reverse crosslinking; remove proteins and contaminants [15] |

| Library Preparation | Illumina, MGI-compatible kits | Prepare sequencing libraries; platform-specific protocols [16] |

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation remains a cornerstone technique for studying protein-DNA interactions in their native chromatin context. The core principle of using specific antibodies to isolate and analyze protein-bound DNA fragments has enabled unprecedented insights into gene regulatory mechanisms, particularly in the realm of histone modifications and epigenetics. While the fundamental workflow has remained consistent, ongoing methodological refinements—especially the integration with next-generation sequencing and development of multiplexed approaches—continue to expand ChIP's applications and quantitative capabilities.

The successful implementation of ChIP and ChIP-Seq requires careful attention to multiple experimental parameters, including crosslinking conditions, chromatin fragmentation, antibody specificity, and appropriate controls. The continued optimization of protocols, particularly for challenging samples like solid tissues, ensures that ChIP methodologies will remain essential tools for unraveling the complex landscape of gene regulation in health and disease. As sequencing technologies advance and become more accessible, ChIP-Seq is poised to remain the preferred method for comprehensive epigenomic studies, providing increasingly detailed insights into the fundamental mechanisms controlling gene expression.

ChIP-seq vs. Other Epigenomic Profiling Methods

Epigenomic profiling encompasses a suite of powerful techniques designed to map the molecular annotations on the genome that regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These modifications include histone post-translational modifications, transcription factor binding, and DNA methylation, which collectively orchestrate chromatin architecture and cellular identity. Among the most widely used methods is Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq), a targeted approach for mapping the genomic binding sites of specific proteins. However, to fully understand the epigenetic landscape, ChIP-seq is often used in conjunction with other, broader profiling techniques such as those for analyzing DNA methylation.

The choice of epigenomic method is critical and depends on the specific biological question, the required resolution, and practical considerations such as sample type, DNA input, and cost. This article provides a detailed comparison of these methods, with a specific focus on presenting an optimized ChIP-seq protocol for histone modification studies, framed within the context of a broader research thesis. The protocols and application notes are designed to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the most appropriate epigenomic tools for their investigative needs.

Comparative Analysis of Epigenomic Profiling Techniques

DNA Methylation Profiling Methods

While ChIP-seq targets protein-DNA interactions, understanding DNA methylation provides a complementary layer of epigenetic information. A 2025 comparative evaluation assessed four key DNA methylation detection approaches, revealing distinct strengths and limitations for each [20].

Table 1: Comparison of Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Detection Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Resolution | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Bisulfite conversion of unmodified cytosines | Single-base | Considered the gold standard; assesses nearly every CpG site | DNA degradation; high cost; data analysis challenges [20] |

| Illumina MethylationEPIC Microarray | Bisulfite conversion followed by hybridization to probes | Single-base (but only at pre-defined sites) | Cost-effective; easy, standardized data processing | Interrogates only a pre-designed set of ~935,000 CpG sites [20] |

| Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq) | Enzymatic conversion and protection of methylated cytosines | Single-base | Preserves DNA integrity; high concordance with WGBS; lower DNA input | Relatively newer method [20] |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) Sequencing | Direct detection via electrical signal changes in nanopores | Single-base | Long-read sequencing enables haplotype-resolution; no conversion needed | Requires high DNA input; lower agreement with WGBS/EM-seq in some comparisons [20] |

The study found that EM-seq showed the highest concordance with the established WGBS method and offered more uniform coverage, while ONT sequencing excelled in capturing methylation in challenging genomic regions and providing long-range information [20]. Despite substantial overlap, each method uniquely identified a set of CpG sites, underscoring their complementary nature in exploring the methylome.

Positioning of ChIP-seq in the Epigenomic Toolkit

ChIP-seq occupies a distinct and crucial niche in the epigenomic toolkit. Unlike the methods described above that directly probe DNA modification, ChIP-seq is designed to investigate protein-DNA interactions. This makes it indispensable for mapping the genomic occupancy of transcription factors, specific histone modifications (e.g., H3K27ac, H3K4me3), and other chromatin-associated proteins. The fundamental principle involves cross-linking proteins to DNA, fragmenting the chromatin, immunoprecipitating the protein-DNA complexes with a specific antibody, and then sequencing the bound DNA fragments.

The choice between a method like ChIP-seq and a DNA methylation profiling technique is therefore dictated by the biological target. A researcher studying enhancer activation would select ChIP-seq for H3K27ac, while an investigator examining imprinting disorders might prioritize a DNA methylation method. Furthermore, these techniques can be integrated in multi-omics approaches to build a comprehensive model of gene regulation.

Optimized ChIP-seq Protocol for Histone Modifications

Refined Protocol for Solid Tissues

Performing ChIP-seq on solid tissues presents unique challenges, including cellular heterogeneity, complex extracellular matrices, and difficulty in chromatin fragmentation. A 2025 refined protocol addresses these hurdles with optimized procedures for tissue preparation, chromatin immunoprecipitation, and library construction, making it highly suitable for histone modification research in physiologically relevant contexts like colorectal cancer [19].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ChIP-seq in Solid Tissues

| Research Reagent | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Specific Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of cross-linked protein-DNA complexes; crucial for specificity and signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Chromatin Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality, intact chromatin from complex tissue matrices. |

| Library Preparation Kit | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from immunoprecipitated DNA; compatible with the sequencing platform. |

| DNBSEQ-G99RS Platform | A sequencing platform (e.g., from MGI) used for generating high-quality data from the prepared libraries [19]. |

| Cross-linking Agent (e.g., Formaldehyde) | Stabilizes protein-DNA interactions in their native state within the tissue. |

| Cell Lysis & Chromatin Shearing Buffers | Cell lysis and fragmentation of cross-linked chromatin to an optimal size for sequencing. |

The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages of this optimized protocol:

Quantitative ChIP-seq Data Processing

A critical step after sequencing is the accurate processing and normalization of data to enable meaningful biological comparisons. A 2025 protocol emphasizes the use of the sans spike-in quantitative ChIP (siQ-ChIP) method for absolute quantification of immunoprecipitation efficiency and normalized coverage for relative comparisons [21]. This approach overcomes the limitations of traditional spike-in normalization by providing a mathematically rigorous framework that relies on fundamental experimental parameters like antibody behavior, chromatin fragmentation efficiency, and input DNA quantification [21].

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for ChIP-seq Data Processing

| Software Tool | Function | Recommended Version/OS |

|---|---|---|

| Atria | Read preprocessing and trimming | 4.0.3 (macOS, Linux) [21] |

| Bowtie2 | Alignment of sequenced reads to a reference genome | 2.5.4 (macOS, Linux) [21] |

| Samtools | Processing and manipulation of alignment files | 1.21 (macOS, Linux) [21] |

| IGV (Integrative Genomics Viewer) | Visualization of genome-wide ChIP-seq signals | 2.19.1 (macOS) [21] |

| Julia / Python | Programming languages for running custom siQ-ChIP scripts | Julia 1.8.5; Python 3.12.7 [21] |

The bioinformatic workflow for processing ChIP-seq data, from raw reads to quantitative signals, can be visualized as follows:

Advanced Applications and Integrative Analyses

Differential ChIP-seq Analysis

A common goal in epigenomics is to compare protein binding or histone modification levels between biological states (e.g., disease vs. healthy, treated vs. untreated). This is known as differential ChIP-seq (DCS) analysis. A comprehensive 2022 benchmark of 33 computational tools for DCS revealed that tool performance is highly dependent on the shape of the ChIP-seq signal and the biological regulation scenario [9].

- Peak Shapes: Transcription factors (TFs) produce "sharp" peaks over narrow genomic regions. Histone marks like H3K27ac also produce "sharp" peaks, while marks like H3K27me3 and H3K36me3 produce "broad" domains that can span large genomic regions [9].

- Regulation Scenarios: Performance varies between scenarios where some peaks increase and others decrease (50:50 ratio) versus scenarios involving a global loss of signal (100:0 ratio), as seen after protein inhibition or knockout [9].

- Tool Recommendations: The study found that performance was not dominated by a single tool. Instead, tools like bdgdiff (MACS2), MEDIPS, and PePr showed robust median performance, but the optimal tool choice depends on the specific experimental context [9].

Integration with Other Omics Data

ChIP-seq data gains maximum biological insight when integrated with other datasets. A prime example is a protocol that combines affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) with ChIP-seq to map transcription factor interactomes and composite DNA motifs [22]. This integrated approach allows for the concurrent identification of a transcription factor's protein interaction partners and its genomic binding sites, with each dataset validating and informing the other.

Another advanced application involves highly quantitative comparisons across different cell states or models. The PerCell method uses cellular spike-ins of orthologous species' chromatin combined with a bioinformatic pipeline to enable precise, normalized comparisons of ChIP-seq data across experimental conditions, such as between zebrafish embryos and human cancer cells [23].

The selection of an epigenomic profiling method is a strategic decision that directly impacts the quality and scope of biological insights. For mapping protein-DNA interactions, particularly histone modifications, ChIP-seq remains a cornerstone technique. The availability of optimized wet-lab protocols for challenging samples like solid tissues [19], coupled with robust and quantitative bioinformatic processing methods like siQ-ChIP [21], empowers researchers to generate high-quality, reproducible data.

The field is moving beyond simple mapping towards quantitative and integrative analyses. As benchmark studies show, the careful selection of differential analysis tools is paramount [9]. Furthermore, combining ChIP-seq with interactome data [22] or using advanced normalization for cross-species comparisons [23] represents the cutting edge. By understanding the comparative landscape of epigenomic methods and implementing the detailed protocols outlined herein, researchers can systematically unravel the complex epigenetic mechanisms underlying development, disease, and drug response.

Histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) are fundamental epigenetic mechanisms that regulate gene expression by altering chromatin structure without changing the underlying DNA sequence [24]. These modifications include methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation of specific amino acid residues on histone tails, which influence whether chromatin adopts an open, transcriptionally active state or a closed, repressive state [24]. Among the numerous histone modifications, H3K4me3 (Histone H3 Lysine 4 trimethylation) and H3K27me3 (Histone H3 Lysine 27 trimethylation) represent two of the most widely studied marks with largely antagonistic functions [25] [26].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has revolutionized our ability to study these modifications genome-wide [17]. This powerful method combines the specificity of antibodies with the throughput of next-generation sequencing to map protein-DNA interactions and epigenetic landscapes [27]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the precise distribution of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 provides critical insights into gene regulatory networks disrupted in disease states and reveals potential therapeutic targets [24].

Characterizing Key Histone Modifications

Properties and Genomic Distributions

H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 represent opposing regulatory forces in epigenetic control, with distinct genomic distributions and functional consequences.

Table 1: Characteristics of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 Histone Modifications

| Feature | H3K4me3 | H3K27me3 |

|---|---|---|

| Associated Chromatin State | Open, accessible chromatin | Closed, facultative heterochromatin |

| Transcriptional Influence | Activation | Repression |

| Primary Genomic Location | Active promoters [26] | Promoters of developmentally-regulated genes [26] |

| Depositing Enzyme | SET1/MLL family methyltransferases [24] | Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) [26] |

| Stability | Dynamic regulation | Relatively stable, maintenance of cellular memory [28] |

| Role in Development | Maintains pluripotency genes in active state [25] | Represses lineage-specific genes until differentiation [25] |

| Forensic Potential | Detectable in degraded samples [28] | Chemically stable in postmortem tissues [28] |

Functional Roles in Gene Regulation

The functional interplay between H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 creates a sophisticated regulatory system for precise developmental control. H3K4me3 establishes a permissive environment at promoters of actively transcribed genes and genes poised for activation, facilitating recruitment of transcription machinery [24]. H3K27me3 maintains stable, heritable transcriptional silencing of developmental genes, particularly those regulating cell fate decisions [26]. Remarkably, in some contexts including stem cells and early development, these apparently opposing marks can co-occur at the same genomic locations, creating "bivalent" domains that keep genes in a transcriptionally poised state—repressed but capable of rapid activation upon differentiation signals [29] [25] [26].

Recent research has revealed evolutionary conservation of H3K27me3 function in the closest living relatives of animals. In the choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta, H3K27me3 decorates cell type-specific genes and marks transposable elements, suggesting dual roles in gene regulation and genome defense that predate animal multicellularity [26].

Optimized ChIP-Seq Experimental Design

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

Successful ChIP-seq begins with proper sample preparation. For histone modifications, cross-linked chromatin is typically sheared to 200-600 bp fragments using sonication, with optimized conditions required for challenging tissues like frozen adipose tissue with high lipid content [30]. Key quality metrics include:

- Chromatin Integrity: Assess fragment size distribution after shearing

- Antibody Specificity: Validate using peptide competition or knockout cells

- Input Control: Prepare matched input DNA (whole cell extract) for background subtraction [31]

The ENCODE consortium recommends specific quality thresholds including NRF > 0.9, PBC1 > 0.9, and PBC2 > 10 for library complexity [17]. For histone ChIP-seq, biological replicates are essential, with sequencing depth requirements of 20 million usable fragments for narrow marks (including H3K4me3) and 45 million for broad marks (including H3K27me3) per replicate [17].

Controls and Standards

Appropriate controls are critical for meaningful ChIP-seq data interpretation. The most common controls include:

- Whole Cell Extract (WCE): Also called "input," this sample undergoes shearing but no immunoprecipitation [31]

- Histone H3 Control: For histone modifications, an H3 pull-down maps overall nucleosome distribution [31]

- IgG Control: Non-specific antibody immunoprecipitation assesses background binding

Comparative studies indicate that H3 controls better account for nucleosome positioning biases in histone modification ChIP-seq, while WCE measures enrichment relative to uniform genomic background [31]. The ENCODE consortium provides rigorous antibody characterization standards and recommends matched control experiments with identical run type, read length, and replicate structure [17].

ChIP-seq Protocol for Histone Modifications

Chromatin Preparation and Immunoprecipitation

The following protocol has been optimized for histone modifications based on recent methodological advances [29] [30]:

Day 1: Cross-linking and Chromatin Preparation

- Cross-link cells or tissue with 1% formaldehyde for 8-12 minutes at room temperature

- Quench cross-linking with 125 mM glycine for 5 minutes

- Wash cells twice with cold PBS containing protease inhibitors (PIC, PMSF, NaBu)

- Resuspend cell pellet in Cell Lysis Buffer (5 mM PIPES, 85 mM KCl, 1% NP-40) and incubate 15 minutes on ice

- Pellet nuclei and resuspend in Nuclear Lysis Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS)

- Sonicate chromatin to 200-500 bp fragments using Bioruptor or Covaris sonicator

- Centrifuge at 13,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C; collect supernatant

Day 2: Immunoprecipitation

- Dilute chromatin 10-fold in RIPA Zero-SDS Buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS)

- Pre-clear chromatin with Protein G beads for 1-2 hours at 4°C

- Incubate with histone modification-specific antibody (1-5 μg per reaction) overnight at 4°C with rotation

- Add pre-washed Protein G beads and incubate 4-6 hours at 4°C

- Wash beads sequentially with:

- Low Salt Wash Buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl)

- High Salt Wash Buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl)

- LiCl Wash Buffer (0.25 M LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl)

- TE Buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA)

- Elute chromatin with Elution Buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO₃)

- Reverse cross-links overnight at 65°C with 200 mM NaCl

- Treat with RNase A and Proteinase K, then purify DNA with MinElute columns

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Quantify recovered DNA using Qubit fluorometer

- Verify fragment size distribution with Agilent Bioanalyzer

- Prepare sequencing libraries using ThruPLEX DNA-Seq kit with unique dual indexes

- Amplify with 10-12 PCR cycles based on input amount

- Perform size selection with AMPure XP beads

- Validate final libraries by Bioanalyzer and qPCR

- Sequence on Illumina platform with 50+ bp single-end reads, aiming for 20-45 million reads per sample depending on mark [17]

ChIP-seq Experimental Workflow

Data Analysis and Quality Assessment

Processing Pipeline and Standards

The ENCODE consortium has established standardized processing pipelines for histone ChIP-seq data [17]. Key steps include:

- Read Mapping: Align reads to reference genome using appropriate tools (Bowtie2)

- Peak Calling: Identify significantly enriched regions using MACS2 or similar tools

- Signal Tracking: Generate fold-change over control and signal p-value tracks in bigWig format

- Quality Metrics: Calculate FRiP scores, library complexity, and reproducibility

For differential binding analysis, specialized tools like diffBind are recommended. The ROSALIND platform provides accessible ChIP-seq analysis without programming requirements, enabling interactive exploration of differential binding and pathway enrichment [27].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Table 2: ChIP-seq Quality Control Metrics and Troubleshooting

| Quality Metric | Target Value | Potential Issue | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment Rate | >80% [27] | Poor sample quality or wrong reference | Check DNA degradation, verify genome build |

| Duplicate Rate | <25% [27] | Over-amplification or insufficient sequencing depth | Increase starting material, sequence deeper |

| FRiP Score | >1% for broad marks, >5% for narrow marks | Inefficient IP or poor antibody | Optimize antibody amount, verify antibody specificity |

| Peak Number | Mark-dependent | Under- or over-digestion | Optimize sonication conditions |

| Reproducibility | IDR < 0.05 | Technical or biological variability | Increase replicates, standardize protocols |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Technologies

Innovative Methodologies

Recent technological advances have expanded histone modification profiling capabilities:

- ChIP-reChIP: Enables investigation of bivalent histone modifications by performing sequential immunoprecipitations [29]

- EpiDamID: Uses antibody-directed methylation to profile histone modifications at single-cell resolution while simultaneously measuring transcription [32]

- CUT&Tag: An efficient alternative to ChIP-seq that uses antibody-directed tethering of Tn5 transposase for low-input profiling [28]

- RPPA (Reverse Phase Protein Array): Enables high-throughput quantification of histone PTMs across hundreds of samples [24]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Histone Modification Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | H3K4me3 (Active Motif), H3K27me3 (Millipore) | Target-specific immunoprecipitation | Validate specificity using peptide competition [31] |

| Chromatin Shearing | Covaris sonicator, Bioruptor | Fragment chromatin to optimal size | Optimize for cell/tissue type; 200-500 bp ideal [30] |

| Library Prep | ThruPLEX DNA-Seq kit, TruSeq DNA Sample Prep | Prepare sequencing libraries | Select kits compatible with low-input DNA [30] |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | PIC, PMSF, NaBu | Preserve histone modifications during processing | Include HDAC inhibitors (NaBu) for acetylation marks [30] |

| Magnetic Beads | Dynabeads Protein G | Antibody capture and washing | More consistent than agarose beads for low-abundance targets |

Research Applications and Case Studies

Biological Insights from Histone Modification Studies

Comprehensive profiling of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 has yielded fundamental insights across diverse biological systems:

In chicken germline specification, researchers discovered that H3K4me3 depletion facilitates the transition of bivalent chromatin states toward repression, enabling proper germ cell differentiation [25]. Experimental inhibition of H3K4me3 deposition enhanced primordial germ cell-like cell (PGCLC) induction efficiency by repressing BMP signaling antagonists [25].

Evolutionary studies in choanoflagellates revealed that H3K27me3 marks both cell type-specific genes and transposable elements, suggesting an ancestral dual role in gene regulation and genome defense that predates animal multicellularity [26]. These findings indicate the deep evolutionary conservation of these key regulatory modifications.

Emerging forensic applications leverage the chemical stability of histone modifications in degraded samples. H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 show promise for differentiating monozygotic twins, estimating postmortem intervals, and analyzing compromised biological evidence [28].

Therapeutic Implications

The reversible nature of histone modifications makes them attractive therapeutic targets. Small molecule inhibitors targeting histone-modifying enzymes have shown promise in clinical contexts [24]:

- EZH2 inhibitors target H3K27me3 deposition and are being evaluated in clinical trials for cancer therapy [24]

- Bromodomain inhibitors disrupt reading of acetylated histones to modulate oncogene expression [24]

- Histone demethylase inhibitors of LSD1/LSD2 (H3K4me demethylases) can reactivate silenced tumor suppressor genes [24]

The ability to profile these modifications through optimized ChIP-seq protocols enables monitoring of therapeutic efficacy and identification of epigenetic biomarkers for patient stratification.

H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 represent pivotal counterbalancing forces in epigenetic regulation of gene expression. The continuous refinement of ChIP-seq methodologies—from sample preparation through data analysis—has dramatically enhanced our resolution for mapping these modifications genome-wide. As single-cell and low-input technologies mature, and as computational methods grow more sophisticated, our ability to decipher the complex interplay between these histone marks will continue to accelerate.

For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these protocols provides powerful tools for uncovering disease mechanisms, identifying novel therapeutic targets, and developing epigenetic biomarkers. The integration of histone modification profiling into multi-omics approaches promises to further illuminate the dynamic regulatory networks that govern cellular identity and function in health and disease.

The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) and its model organism counterpart (modENCODE) represent large-scale collaborative research initiatives funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) with the primary goal of building a comprehensive parts list of functional elements in human and model organism genomes [33] [34]. Launched in 2003, ENCODE was designed as a natural successor to the Human Genome Project, addressing the critical challenge that while only approximately 1% of the human genome codes for proteins, the vast majority exhibits biochemical activity and requires systematic functional characterization [35] [36]. These consortia bring together hundreds of researchers from dozens of institutions worldwide to establish standardized methods, rigorous quality metrics, and centralized data resources for the genomics community [36] [33].

The establishment of standardized ChIP-seq guidelines emerged as a critical need within these consortia as the technology became the method of choice for mapping protein-DNA interactions genome-wide [37] [3]. Before these standardized frameworks, considerable differences existed in how ChIP-seq experiments were conducted, scored, evaluated for quality, and archived, significantly affecting data quality, utility, and cross-study comparability [3]. The ENCODE and modENCODE consortia have performed more than a thousand individual ChIP-seq experiments for over 140 different factors and histone modifications across more than 100 cell types in humans, mice, Drosophila melanogaster, and Caenorhabditis elegans, providing an extensive empirical foundation for developing evidence-based guidelines [3]. These guidelines address critical experimental parameters including antibody validation, experimental replication, sequencing depth, data reporting, and quality assessment, creating a robust framework that has significantly enhanced the reliability and reproducibility of ChIP-seq data, particularly for profiling histone modifications [37] [17].

Experimental Design and Quality Control Framework

Antibody Validation and Characterization

The quality of any ChIP-seq experiment is fundamentally governed by the specificity of the antibody employed in the immunoprecipitation step [3]. The ENCODE consortium has established a rigorous two-test framework for antibody characterization—a primary and secondary test—that must be performed for each monoclonal antibody or different lots of the same polyclonal antibody [3]. For antibodies directed against transcription factors, immunoblot analysis serves as the primary characterization method, with the guideline that the primary reactive band should contain at least 50% of the signal observed on the blot and ideally correspond to the expected size of the target protein [3]. When immunoblot analysis proves unsuccessful, immunofluorescence demonstrating expected nuclear localization patterns serves as an acceptable alternative primary characterization method [3].

For histone modifications, the consortium's standards require demonstrating that the antibody specifically recognizes the intended modified histone without cross-reacting to similar epitopes or unmodified histones [17]. This characterization includes dot blot assays using a panel of modified and unmodified peptides to establish specificity [17]. The metadata pertaining to antibodies, including source, product number, and most critically, the specific lot number, must be comprehensively recorded due to potential lot-to-lot variation in specificity and sensitivity [38]. This rigorous validation framework ensures that the reagents used in ChIP-seq experiments provide specific and reproducible enrichment of the intended targets, forming the foundation for reliable histone modification mapping.

Experimental Replication and Controls

The ENCODE guidelines mandate the inclusion of two or more biological replicates for all ChIP-seq experiments to ensure findings are reproducible and not attributable to technical artifacts or random biological variation [17]. Biological replicates are defined as independent samples prepared and processed through the entire experimental workflow separately, providing measures of both technical and biological variability [3]. This replication strategy allows for statistical assessment of reproducibility and provides confidence in the identified binding sites or modification domains.

Additionally, each ChIP-seq experiment must include a corresponding input control experiment with matching run type, read length, and replicate structure [17]. The input control consists of genomic DNA that has been cross-linked and fragmented similarly to the ChIP sample but without immunoprecipitation, serving to control for technical biases introduced during sample processing, sequencing, and analysis, such as those arising from chromatin accessibility, DNA fragmentation, and amplification [3] [17]. For experiments where specific histone modifications are being investigated, the use of matched input controls is particularly critical for distinguishing true enrichment from background signal in different genomic regions [17].

Table 1: ENCODE Experimental Replication and Control Requirements

| Component | Requirement | Purpose | Quality Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Replicates | Minimum of two | Assess reproducibility and statistical significance | Overlap between replicates; IDR (Irreproducible Discovery Rate) |

| Input Control | Required for each experiment | Control for technical biases | Matching read length and replicate structure to experimental samples |

| Library Complexity | NRF > 0.9; PBC1 > 0.9; PBC2 > 10 | Ensure sufficient sequencing depth without amplification artifacts | Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF); PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients (PBC1/PBC2) |

Sequencing Depth and Library Quality Standards

The ENCODE consortium has established target-specific sequencing depth requirements based on the characteristics of the histone modification being studied [17]. For narrow histone marks such as H3K4me3 and H3K27ac, each biological replicate should contain at least 20 million usable fragments, while for broad histone marks such as H3K27me3 and H3K36me3, each replicate should contain 45 million usable fragments [17]. The exception to these standards is H3K9me3, which is enriched in repetitive regions of the genome and thus requires special consideration regarding mapping and interpretation [17].

Library complexity represents another critical quality parameter, with the consortium recommending specific metrics to evaluate potential amplification biases [17]. The Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) should exceed 0.9, while the PCR Bottlenecking Coefficients should demonstrate PBC1 > 0.9 and PBC2 > 10 [17]. These metrics ensure that the sequencing library captures sufficient diversity of DNA fragments without excessive PCR amplification, which can introduce artifacts and reduce the complexity of the sequenced material. The establishment of these quantitative standards provides clear benchmarks for researchers to assess whether their ChIP-seq experiments have achieved sufficient depth and quality for robust biological interpretation.

Optimized ChIP-seq Protocol for Histone Modifications

Cross-linking and Chromatin Shearing Optimization

The initial steps of cross-linking and chromatin fragmentation represent critical determinants of success in ChIP-seq experiments for histone modifications. While transcription factor ChIP-seq typically requires formaldehyde cross-linking to capture transient DNA-protein interactions, native ChIP (without cross-linking) can often be employed for histone modifications due to the stable integration of histones into chromatin [3]. However, when cross-linking is necessary, particularly when studying histone modifications in conjunction with other DNA-associated proteins, optimization of formaldehyde concentration is essential.

Recent methodological advances demonstrate that 1% formaldehyde typically provides sufficient cross-linking efficiency while maintaining antibody accessibility to histone epitopes [39]. Following cross-linking, chromatin must be fragmented to sizes appropriate for high-resolution mapping. Both sonication and enzymatic digestion (e.g., with micrococcal nuclease) represent valid fragmentation approaches, with sonication being more widely applied in ENCODE protocols [3]. Optimization experiments should target DNA fragment sizes of 200-500 base pairs, with 250 bp representing an ideal median size that balances resolution and immunoprecipitation efficiency [39]. As demonstrated in optimized protocols for green algae, systematic testing of sonication conditions (e.g., duration, amplitude, and pulse settings) is necessary to establish laboratory-specific parameters that achieve the desired fragmentation [39].

Immunoprecipitation and Library Preparation

The immunoprecipitation step represents the core enrichment process in ChIP-seq, where validated antibodies specific to the histone modification of interest are used to precipitate the cross-linked protein-DNA complexes. The ENCODE guidelines emphasize the importance of using characterized antibodies with demonstrated specificity for the target epitope [3] [17]. Following immunoprecipitation, cross-links are reversed, proteins are digested, and the enriched DNA is purified. The quality and quantity of this immunoprecipitated DNA should be assessed before proceeding to library preparation, with quantitative PCR at positive and negative control genomic regions providing a rapid method for evaluating enrichment efficiency.

Library preparation for sequencing follows standard protocols, but particular attention should be paid to minimizing PCR amplification biases, which can distort the representation of different genomic regions [17]. The use of minimal PCR cycles and library complexity metrics (NRF, PBC1, PBC2) provides quantitative assessment of potential amplification artifacts [17]. Modern library preparation methods incorporating unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) can further help to control for amplification biases and improve quantitative accuracy, though these have not yet been formally incorporated into ENCODE standards. The final sequencing library should be quantitatively assessed using appropriate methods (e.g., qPCR, Bioanalyzer, or TapeStation) to ensure adequate concentration and size distribution before sequencing.

Table 2: Target-Specific Sequencing Standards for Histone Modifications

| Histone Modification Type | Examples | Minimum Reads per Replicate | Peak Calling Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow Marks | H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K9ac | 20 million | Sharp peak calling |

| Broad Marks | H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K9me2 | 45 million | Broad domain calling |

| Special Case | H3K9me3 | 45 million (with special considerations for repetitive regions) | Broad domain calling |

Data Analysis and Quality Assessment Pipeline

The ENCODE consortium has developed specialized analysis pipelines for histone ChIP-seq data that differ from those used for transcription factors, reflecting the distinct genomic distributions of these protein classes [17]. The histone analysis pipeline is designed to resolve both punctate binding and longer chromatin domains, generating two primary types of signal tracks: fold change over control and signal p-value tracks that test the null hypothesis that the signal at each genomic location is present in the control [17]. This dual approach provides complementary perspectives on enrichment patterns.

For peak calling, the histone pipeline employs a two-stage approach that first identifies relaxed peak calls from individual replicates and pooled data, then applies statistical methods to identify reproducible peaks across replicates [17]. For experiments with biological replicates, the final peak set consists of regions observed in both replicates or in pseudoreplicates derived from random partitioning of pooled reads [17]. Key quality metrics including the FRiP score (Fraction of Reads in Peaks), which measures the enrichment of the immunoprecipitated sample relative to the input control, with specific targets varying based on the histone mark being studied [17]. Additional quality measures include cross-correlation analysis and reproducibility metrics between replicates, which collectively provide a comprehensive assessment of data quality.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ENCODE-Compliant Histone ChIP-seq

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance | ENCODE Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibodies | H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K27me3, H3K36me3 | Specific immunoprecipitation of target histone modifications | Primary and secondary validation required; lot number tracking |

| Cross-linking Reagents | Formaldehyde (1% final concentration) | Preservation of protein-DNA interactions | Concentration optimization required for different cell types |

| Chromatin Shearing | Sonication systems (Bioruptor, Covaris) | DNA fragmentation to 200-500bp | Fragment size distribution validation |

| Library Preparation | Illumina-compatible kits with minimal PCR cycles | Preparation of sequencing libraries | Monitoring of library complexity metrics (NRF, PBC) |

| Quality Assessment | QPCR reagents, Bioanalyzer/TapeStation kits | Assessment of DNA quality and quantity | FRiP score calculation; cross-correlation analysis |

The guidelines established by the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia have fundamentally transformed the practice of ChIP-seq for histone modification research, replacing ad hoc protocols with standardized, evidence-based methods that prioritize reproducibility, rigor, and data quality [37] [3]. These standards have enabled the creation of comprehensive reference epigenomes across diverse cell types and tissues, providing invaluable resources for interpreting genome function and regulation [35] [36]. The systematic application of these guidelines has revealed that at least 80% of the human genome participates in biochemical activity, predominantly in regulatory functions, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of genome biology and challenging the concept of "junk" DNA [35] [36].

The legacy of ENCODE and modENCODE continues to evolve through next-generation initiatives such as the Impact of Genomic Variation on Function (IGVF) Consortium, which aims to build upon ENCODE's foundational resources by investigating how genomic variation influences the function of regulatory elements identified through these standardized approaches [35]. Furthermore, technological advances in single-cell multiomics are pushing beyond the bulk tissue analyses that characterized much of the ENCODE production phase, enabling the characterization of gene expression, functional states, and regulatory motifs from the same single cells [35]. These advances, built upon the rigorous foundation established by ENCODE and modENCODE, promise to further illuminate the intricate regulatory landscape of the genome and its implications for human health and disease.

Executing a Robust ChIP-seq Protocol: From Sample Prep to Sequencing

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) represents a cornerstone technique in molecular biology for investigating protein-DNA interactions within their natural chromatin context [40]. This antibody-based technology enables researchers to selectively enrich specific DNA-binding proteins along with their genomic targets, providing critical insights into gene regulatory mechanisms, transcription factor binding, and epigenetic landscapes [41]. The fundamental principle behind ChIP relies on using antibodies to isolate, or precipitate, a target protein (such as a histone, transcription factor, or cofactor) and its bound DNA from a complex protein mixture extracted from cells or tissues [41]. The immunoprecipitated DNA fragments are then identified and quantified using various downstream analytical methods, including qPCR, microarrays (ChIP-chip), or next-generation sequencing (ChIP-seq) [41].

When designing a ChIP experiment, researchers face a critical methodological decision: whether to use crosslinked ChIP (X-ChIP) or native ChIP (N-ChIP). This decision profoundly impacts every subsequent step of the protocol and ultimately determines the success and biological relevance of the experiment. X-ChIP utilizes chemical fixatives, typically formaldehyde, to crosslink proteins to DNA prior to chromatin fragmentation, thereby preserving transient protein-DNA interactions [41] [42]. In contrast, N-ChIP employs native, non-crosslinked chromatin prepared by nuclease digestion of cell nuclei, maintaining proteins in their natural state without artificial stabilization [41] [43]. The choice between these approaches must be guided by the specific biological question, the nature of the target protein, and the desired resolution of the study.

Comparative Analysis: X-ChIP versus N-ChIP

Technical and Practical Differences

The decision between X-ChIP and N-ChIP involves careful consideration of multiple technical parameters, each with distinct advantages and limitations that make them suitable for different experimental scenarios.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of X-ChIP and N-ChIP Methodologies

| Parameter | Native ChIP (N-ChIP) | Crosslinked ChIP (X-ChIP) |

|---|---|---|

| Crosslinking | No chemical fixation; cells remain in native state [42] | Formaldehyde-based fixation "freezes" protein-DNA interactions [41] |

| Chromatin Fragmentation | Enzymatic digestion with micrococcal nuclease (MNase) [41] [40] | Sonication or nuclease digestion [41] [42] |

| Ideal Fragment Size | ~147 bp (mononucleosomes) [40] | 200-1000 bp [41] |

| Target Applications | Histone modifications and abundant targets [41] [42] | Histone modifications, transcription factors, cofactors [41] [42] |

| Antibody Efficiency | Increased affinity as antibodies recognize native epitopes [42] [43] | Potential epitope masking due to crosslinking [42] [43] |

| Resolution | High (nucleosome-level) [40] | Lower (broader regions) [40] |

| Precipitation Efficiency | Highly efficient for histones [40] | Less efficient, requires PCR amplification [41] |

| Transient Interaction Capture | Poor for transient binders [41] | Effective capture of transient interactions [41] |

Performance and Outcome Comparison

Recent genome-wide comparative studies have provided quantitative insights into the performance characteristics of both N-ChIP and X-ChIP methodologies. Research utilizing Chromatrap spin column technology demonstrated that both approaches can generate high-quality data suitable for next-generation sequencing applications [44]. In a comprehensive comparison focusing on the histone mark H3K4me3 (associated with gene activation), N-ChIP identified approximately 65,000 enrichment peaks with 3 to >30-fold enrichment over input, while X-ChIP detected approximately 39,000 peaks [44]. The higher number of peaks in N-ChIP may result from formaldehyde crosslinks potentially masking protein epitopes in X-ChIP, making them less accessible to antibody recognition [44].

Both methods have demonstrated capability to produce high-quality sequencing metrics, with Q-scores above 30 (indicating a base call accuracy of 99.9%) and low duplication rates (<5%) [44]. When analyzing uniquely identified genes associated with H3K4me3 enrichment, studies revealed approximately 90% similarity between N-ChIP and X-ChIP samples, with 20,315 uniquely mapped genes for N-ChIP and 19,508 for X-ChIP [44]. This high degree of concordance suggests that despite their methodological differences, both techniques can yield biologically consistent results when appropriately optimized.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for N-ChIP vs. X-ChIP

| Performance Metric | N-ChIP | X-ChIP |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Peak Numbers (H3K4me3) | ~65,000 peaks [44] | ~39,000 peaks [44] |

| Peak Enrichment Range | 3 to >30-fold over input [44] | Variable, typically lower than N-ChIP [44] |

| Sequencing Quality (Q30) | >30 [44] | >30 [44] |

| Duplication Rates | 4.13% [44] | 2.58% [44] |

| Uniquely Identified Genes | 20,315 [44] | 19,508 [44] |

| Inter-Method Concordance | ~90% similarity [44] | ~90% similarity [44] |

Decision Framework: Selecting the Appropriate ChIP Method

Protein- and Application-Specific Considerations

The nature of the DNA-associated protein under investigation represents the primary determinant in selecting between N-ChIP and X-ChIP approaches. This decision framework incorporates both the characteristics of the target protein and the specific research objectives.

For histone proteins and their modifications, N-ChIP generally represents the preferred approach [41] [43]. Histones exhibit strong, stable binding to DNA and do not require stabilization through crosslinking [40]. The absence of formaldehyde fixation in N-ChIP preserves native protein epitopes, allowing for optimal antibody recognition and binding efficiency [42] [43]. This results in higher immunoprecipitation efficiency and superior resolution at the nucleosome level (~147 bp) [40]. Additionally, N-ChIP eliminates potential epitope masking that can occur with formaldehyde crosslinking, which is particularly important when studying histone modifications where antibodies are often raised against unfixed peptide antigens [43].

For transcription factors and loosely-bound chromatin proteins, X-ChIP is essential [41] [40]. These proteins typically exhibit transient interactions with DNA that would be lost during the chromatin preparation steps of N-ChIP [41]. Formaldehyde crosslinking stabilizes these fleeting interactions by creating covalent bonds between proteins and DNA, effectively "freezing" the binding events at the moment of fixation [41]. X-ChIP also enables the study of proteins that interact with DNA indirectly through larger protein complexes, as formaldehyde can crosslink protein-protein interactions in addition to protein-DNA contacts [40]. While X-ChIP generally provides lower resolution than N-ChIP (200-1000 bp fragments versus mononucleosomal fragments) and may reduce antibody efficiency due to epitope masking, it remains the only viable option for many non-histone chromatin proteins [41] [42].

Experimental Design and Practical Implementation Factors

Beyond the nature of the target protein, several additional experimental considerations should inform the choice between N-ChIP and X-ChIP:

Starting material requirements differ between the two approaches. X-ChIP generally requires less cellular material than N-ChIP, making it more suitable for experiments with limited sample availability [41]. However, tissue type and complexity can present additional challenges. Dense or complex tissues may require specialized processing, such as the mincing and homogenization methods described for frozen tissues in colorectal cancer samples [16]. For plant tissues with high polysaccharide content, such as peach fruit mesocarp, optimization of crosslinking conditions and chromatin extraction is particularly important [45].

Fragmentation method represents another critical differentiator. N-ChIP exclusively employs enzymatic digestion with micrococcal nuclease (MNase), which cleaves DNA between nucleosomes [41] [40]. While this provides excellent resolution, MNase exhibits sequence preference and may not digest chromatin evenly across the genome [40]. X-ChIP offers flexibility, allowing either sonication or enzymatic digestion for chromatin fragmentation [41] [42]. Sonication generates truly random fragments but requires extensive optimization and can damage chromatin through heat and detergent exposure [41].

Downstream applications should also influence method selection. For genome-wide studies (ChIP-seq), both methods can generate high-quality data, though N-ChIP may yield higher peak numbers for histone marks [44]. For quantitative comparisons at specific loci (ChIP-qPCR), N-ChIP's superior efficiency and resolution provide advantages [41]. When studying multiple proteins or complex interactions, X-ChIP's ability to capture protein-protein interactions may be beneficial [40].

Protocols and Procedures

Native ChIP (N-ChIP) Workflow

The N-ChIP protocol utilizes native, non-crosslinked chromatin and is ideally suited for studying histone modifications and tightly-bound chromatin proteins.

Critical Step: Chromatin Preparation and MNase Digestion Begin with 1 × 10⁶ cells grown to 80% confluency. Scrape cells in ice-cold PBS and collect by centrifugation. Perform cell lysis in Hypotonic Buffer and separate nuclei by centrifugation. Digest chromatin with micrococcal nuclease (MNase) to yield fragments between 100-500 bp in length [44]. For increased resolution, mononucleosomes (~147 bp) can be isolated through sucrose gradient centrifugation [43]. Dialyze samples to remove impurities before immunoprecipitation. Consistently aliquot MNase enzyme stocks to maintain digestion consistency, as chromatin compaction varies between preparations [40].

Critical Step: Immunoprecipitation and DNA Recovery Prepare immunoprecipitation slurries at a 5:2 chromatin-to-antibody ratio (5 μg chromatin: 2 μg antibody) [44]. Incubate slurries for 1 hour at 4°C with constant rotation. Use solid-phase support matrices (such as Chromatrap columns or magnetic beads) to capture antibody-chromatin complexes. After washing to remove non-specifically bound material, elute specifically bound complexes. Perform brief proteinase K digestion to remove proteins and purify DNA using dedicated purification columns [44]. Include input controls (5 μg chromatin not subjected to immunoprecipitation) for normalization in downstream analyses.

Crosslinked ChIP (X-ChIP) Workflow

The X-ChIP protocol incorporates formaldehyde crosslinking to stabilize protein-DNA interactions, making it suitable for transcription factors and loosely-associated chromatin proteins.

Critical Step: Optimization of Crosslinking Conditions For tissue samples, optimal crosslinking is essential. Using frozen tissue samples, mince tissue finely with scalpel blades on a petri dish placed on ice [16]. Homogenize using either a Dounce tissue grinder (8-10 strokes with pestle A) or a gentleMACS Dissociator with the "htumor03.01" program [16]. Crosslink with 1% formaldehyde for efficient fixation without over-crosslinking, which can reduce fragmentation efficiency and antibody binding [41] [45]. For complex tissues like peach buds and fruits, 1% formaldehyde has proven more effective than 3% for recovering substantial DNA after reverse crosslinking while avoiding over- or under-fixation [45]. Quench crosslinking with glycine before proceeding to chromatin preparation.