Optimizing STAR Aligner Performance: A Comprehensive Guide to Parameter Tuning Across Diverse RNA-seq Read Lengths

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenge of optimizing STAR aligner parameters for different RNA-seq read lengths, a fundamental requirement for accurate transcriptomic analysis in biomedical research and drug development.

Optimizing STAR Aligner Performance: A Comprehensive Guide to Parameter Tuning Across Diverse RNA-seq Read Lengths

Abstract

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenge of optimizing STAR aligner parameters for different RNA-seq read lengths, a fundamental requirement for accurate transcriptomic analysis in biomedical research and drug development. Drawing from recent large-scale benchmarking studies and technical documentation, we explore foundational principles of STAR alignment, provide methodological guidance for application-specific tuning, troubleshoot common optimization challenges, and establish validation frameworks for performance assessment. The content equips researchers with practical strategies to enhance detection sensitivity for clinically relevant subtle differential expressions, improve mapping accuracy across various sequencing platforms, and implement cost-effective computational workflows without compromising data quality.

Understanding STAR Alignment Fundamentals: How Read Length Impacts Mapping Performance and Accuracy

Frequently Asked Questions

How does read length fundamentally affect my alignment results? Read length directly impacts the ability of an aligner to uniquely place reads in the genome, especially in complex repetitive regions. Longer reads provide more contextual information, allowing the aligner to span across multiple exons, repetitive elements, and splice junctions, which leads to more accurate mapping and better detection of structural variants and novel splicing events [1] [2].

I am using a newer genome assembly. Why does this matter for my STAR alignment? Using a newer genome assembly can drastically reduce computational requirements and improve alignment speed. One study demonstrated that updating the Ensembl human genome from release 108 to 111 reduced the index size from 85 GiB to 29.5 GiB and made the alignment process more than 12 times faster on average. This allows for the use of smaller, cheaper cloud instances without sacrificing mapping rates [3].

Can I save computational resources if my data is of poor quality?

Yes, implementing an "early stopping" approach can significantly reduce resource wastage. By monitoring the Log.progress.out file generated by STAR, you can check the mapping rate after aligning a portion of the reads (e.g., 10%). If the mapping rate is unacceptably low (e.g., below 30%), you can terminate the job early. This approach has been shown to reduce total STAR execution time by nearly 20% [3].

What is the minimum read length needed for detecting structural variants? Research based on simulated long-read data from human genomes indicates that optimal discovery of structural variants (SVs) is achieved with reads of at least 20 kb. While some saturation in performance metrics can be seen with shorter reads, 20 kb is the point beyond which substantial improvements in recall are no longer observed [1].

Why is the --sjdbOverhang parameter so important, and how do I set it?

The --sjdbOverhang parameter defines the length of the genomic sequence around the annotated splice junctions that is used for constructing the STAR index. This region is critical for the aligner to accurately map reads that cross splice sites. Setting it incorrectly can lead to poor mapping rates at exon boundaries [4].

The recommended value is read length minus 1. For example:

- 100 bp reads:

--sjdbOverhang 99 - 150 bp reads:

--sjdbOverhang 149 - 250 bp reads:

--sjdbOverhang 249

If you have a mixture of read lengths, use the maximum read length minus one. In most cases, the default value of 100 is sufficient, but for longer reads, explicitly setting this parameter is best practice [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Symptoms

- Uniquely mapped reads % is significantly lower than expected in the

Log.final.outfile. - High percentage of reads unmapped due to being "too short".

Potential Causes and Solutions

- Incorrect

--sjdbOverhang:- Cause: The splice junction database was built with an overhang value too small for your read length, preventing reads from spanning junctions correctly.

- Solution: Re-generate the genome index with the

--sjdbOverhangparameter set correctly toRead Length - 1[4].

Outdated Genome Assembly:

- Cause: An older genome assembly may contain unlocalized sequences and errors that cause spurious mappings.

- Solution: Switch to a newer genome assembly (e.g., Ensembl release 111 vs. 108). This can dramatically improve performance and reduce resource usage [3].

Data Type Mismatch:

- Cause: The input data might be from a sequencing technology incompatible with a standard RNA-seq pipeline, such as single-cell data, which often has an inherently lower mapping rate due to incomplete mRNA coverage.

- Solution: Implement an early stopping check. Analyze the mapping rate in the

Log.progress.outfile after about 10% of reads are processed. If the rate is very low, terminate the job to save resources for more suitable datasets [3].

Problem: Poor Detection of Splice Junctions or Structural Variants

Symptoms

- Low "Number of splices" in the

Log.final.outfile. - Failure to detect known or novel splice junctions or structural variants.

Potential Causes and Solutions

- Read Length Limitations:

- Cause: Short reads are unable to span long exons or repetitive regions, making it impossible to connect distant genomic segments.

- Solution: If possible, switch to a sequencing technology that produces longer reads. The table below summarizes the minimal read lengths required for optimal results in different applications based on simulated data [1].

| Application | Minimal Read Length for Optimal Performance | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Variant Discovery | 20 kb | Recall (sensitivity) no longer increases substantially after 20 kb. |

| Variant Phasing Across Genes | 100 kb | Optimum for haplotyping variants across entire genes is only reached with 100 kb reads. |

- Insufficient Read Depth:

- Cause: Splice junctions and rare structural variants may not be supported by enough reads to pass detection thresholds.

- Solution: Ensure you are using sufficient sequencing coverage (e.g., 40x is common for long-read SV discovery). You can also consider using a 2-pass mapping mode in STAR to improve novel junction detection [4].

Problem: Excessive Memory Usage or Slow Alignment

Symptoms

- STAR alignment fails due to running out of memory.

- The alignment process takes an impractically long time.

Potential Causes and Solutions

- Oversized Genome Index:

- Cause: Using a large, redundant "toplevel" genome assembly from an old release.

- Solution: As highlighted earlier, use a newer genome assembly. The reduction in index size from 85 GiB to 29.5 GiB in one example directly translates to lower RAM requirements and faster index loading [3].

Under-provisioned Computational Resources:

- Cause: The instance type or computer used does not have enough RAM to hold the genome index and process the data.

- Solution: Refer to the table below for recommended computational resources for aligning to a human-sized genome. If using a cloud environment, consider using a memory-optimized instance type (e.g., AWS r6a series) [3] [4].

Table 2: Computational Recommendations for STAR

| Parameter | Minimum Recommendation (Human Genome) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RAM | 32 GB - 64 GB | Essential for loading the genome index. Larger genomes require more RAM [4]. |

| CPU Cores | 8 - 12 threads | More cores significantly speed up alignment via parallelization [4]. |

| Disk Space | 100 - 500 GB | Must accommodate the raw reads, temporary files, and final BAM outputs [4]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building an Optimized STAR Genome Index

This protocol is designed to create a genome index that balances accuracy, sensitivity, and computational efficiency.

Obtain Reference Files:

- Genome FASTA: Download the most recent version of the reference genome for your species (e.g., from Ensembl or GENCODE).

- Gene Annotation (GTF): Download the annotation file that corresponds to your chosen genome version.

Generate the Index: Use the following STAR command.

Key Parameter Rationale:

--sjdbOverhang 149: Optimized for common 150 bp sequencing reads [4].--runThreadN 12: Utilizes 12 CPU threads to speed up the indexing process.

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Effect of Read Length on SV Discovery

This methodology is derived from a published analysis that used simulated reads [1].

Read Simulation:

- Tool: Use SimLoRD (v1.0.2) or a similar read simulator.

- Input: A high-quality, phased genome assembly (e.g., HG00733).

- Parameters: Simulate multiple datasets with 40x coverage, varying only the read length (e.g., from 1 kb to 100 kb).

Read Alignment and Variant Calling:

- Alignment: Align all simulated reads to the reference genome (GRCh38) using

minimap2(v2.14). - Variant Calling: Call SVs using

Sniffles(v1.0.10).

- Alignment: Align all simulated reads to the reference genome (GRCh38) using

Performance Assessment:

- Truth Set: Generate a truth set of SVs by aligning the original genome assembly to the reference.

- Comparison: Use tools like

survyvorto compare the called SVs against the truth set, calculating precision, recall, and F-measure.

Expected Workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Resources for Read Alignment Experiments

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Reference Genome | Provides the sequence against which reads are aligned for variant discovery. Newer versions can offer significant performance gains. | Ensembl Release 111+ "toplevel" genome [3]. |

| Splice-Aware Aligner | Software specifically designed to handle RNA-seq data, which contains reads spanning exon-intron boundaries. | STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) [3] [4]. |

| Long-Read Simulator | Generates synthetic sequencing reads of a fixed length from a known genome, enabling controlled studies of read length impact. | SimLoRD [1]. |

| Structural Variant Caller | Identifies large-scale genomic variations (e.g., deletions, insertions) from aligned sequencing data. | Sniffles (for long-read data) [1]. |

| Compute Infrastructure | Provides the necessary RAM and CPU power to run memory-intensive aligners like STAR on large genomes. | 32+ GB RAM, 8+ CPU cores (for human genomes); Cloud instances (e.g., AWS r6a.4xlarge) [3] [4]. |

| Gpx4-IN-4 | Gpx4-IN-4, MF:C22H21ClN2O5S, MW:460.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Keap1-Nrf2-IN-16 | Keap1-Nrf2-IN-16, MF:C73H114N16O26, MW:1631.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Table: Sequencing Strategy Selection Guide

| Analysis Goal | Recommended Read Type | Recommended Depth/Length | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Gene Expression | Short-read, Paired-end | 25-40 million PE reads; 2x75 bp or 2x100 bp [5] | Cost-effective and robust for high-quality RNA (RIN ≥8) [5]. |

| Isoform Detection & Splicing | Long-read or Deeper Short-read | ≥100 million PE reads; 2x100 bp or Long-reads [5] | Short reads miss splice events; long reads provide full-length transcript resolution [5] [6]. |

| Fusion Gene Detection | Paired-end | 60-100 million PE reads; 2x75 bp minimum, 2x100 bp preferred [5] | Paired-end reads are crucial to anchor breakpoints and resolve junctions [5]. |

| Allele-Specific Expression | Paired-end | ~100 million PE reads [5] | Higher depth is essential for accurate variant allele frequency estimation [5]. |

| Degraded RNA (e.g., FFPE) | rRNA-depletion or Capture-based | Standard depth + 25-50% more reads; use UMIs [5] | Avoid poly(A) selection. Increased depth and UMIs counteract reduced complexity [5]. |

Q1: How do I choose between short-read and long-read sequencing for my RNA-seq experiment?

Your choice should be driven by your primary biological question. Short-read RNA-seq (e.g., Illumina) is highly efficient and accurate for quantifying gene-level expression, making it the standard for differential expression studies [5] [7]. Long-read RNA-seq (e.g., PacBio or Oxford Nanopore) sequences full-length transcripts in a single read, making it superior for discovering and quantifying specific isoforms, identifying novel transcripts, detecting fusion genes, and profiling RNA modifications [8] [6]. If your goal is standard gene-level differential expression and cost is a factor, short-reads are sufficient. For any investigation into transcriptome complexity, long-reads are recommended [5].

Q2: My RNA is from FFPE tissue and is degraded. How should I adjust my sequencing design?

For degraded RNA, standard poly(A) selection protocols should be avoided. Instead, use rRNA depletion or capture-based protocols [5]. Due to reduced library complexity and higher duplication rates, you should sequence deeper—typically adding 25% to 50% more reads than standard recommendations. Whenever possible, incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) during library preparation to accurately collapse PCR duplicates and restore quantitative precision [5].

Q3: What is the minimum read length I should use for differential expression analysis with STAR?

For differential gene expression, a minimum of 50 bp is generally sufficient [7]. However, the standard and more reliable recommendation is to use paired-end reads of 75-100 bp in length [5]. While STAR does not have a direct "minimum read length" parameter, its sensitivity can be tuned for shorter reads using parameters like --outFilterMatchNmin (e.g., setting it to 20 requires a 20 bp aligned length) and --seedSearchStartLmax to increase sensitivity for shorter sequences [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Alignment Rates in STAR

Problem: A high percentage of reads are unmapped, or specifically unmapped because they are "too short".

Investigation & Solutions:

- Check Read Quality: First, use quality control tools like FastQC to inspect your raw reads. Look for issues like pervasive adapter contamination or steep quality drops that might require more aggressive trimming before alignment [10].

- Verify Genome Indices: Ensure the STAR genome indices were generated with an

--sjdbOverhangparameter set appropriately. The recommended value is read length minus 1 [11]. For 100 bp paired-end reads, this should be 99. - Tune Alignment Parameters: If your reads are shorter or of lower quality, you can adjust STAR's stringency to improve mapping [10] [9]:

--outFilterMatchNmin: Lower this value (e.g., to 20) to require a shorter minimum aligned length [9].--seedSearchStartLmax: Increase this value (e.g., to 30) to use longer seeds in the search step, improving sensitivity [9].--outFilterScoreMinOverLread&--outFilterMatchNminOverLread: Set these to 0 to relax score thresholds relative to read length [9].

Issue 2: Low Junction Coverage

Problem: Tools report "low junction coverage" or you have a high proportion of splice junctions supported by very few reads, even with acceptable overall alignment rates [12].

Investigation & Solutions:

- Increase Sequencing Depth: Junction detection is highly dependent on coverage. If a large fraction of your introns are supported by fewer than 10 reads, the simplest solution is to sequence more deeply to saturate the detection of splicing events [12].

- Check for Over-aggressive Filtering: In STAR, the

--outFilterMultimapNmaxparameter limits the number of loci a read can map to. If set too low (default is 10), it may discard reads from complex, repetitive, or multi-isoform regions. Consider increasing this value for isoform-level analyses [10]. - Adjust Intron Size Boundaries: The parameters

--alignIntronMinand--alignIntronMaxdefine the expected intron size range. STAR's defaults are optimized for mammalian genomes. If working with a non-model organism with smaller introns, these parameters must be reduced to allow the aligner to detect smaller splicing events [10] [11].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: STAR Alignment for RNA-seq

This protocol is for aligning paired-end RNA-seq reads to a reference genome using STAR, optimized for a range of read lengths [11].

1. Generate Genome Indices

- Inputs: Reference genome (FASTA file) and gene annotation (GTF file).

- Command Example:

- Key Parameter:

--sjdbOverhang: This is critical for junction discovery. For paired-end reads, this should be set to the length of your read minus one. For example, use 99 for 100 bp reads and 74 for 75 bp reads [11].

2. Align Reads

- Inputs: FASTQ files and the genome indices from step 1.

- Command Example:

- Key Parameters for Read-Length Flexibility:

--outFilterMatchNmin: Sets the minimum aligned length. Consider lowering for shorter reads [9].--outFilterMultimapNmax: Increase this if analyzing isoforms or genes in repetitive regions [10].--alignIntronMinand--alignIntronMax: Adjust these based on the known biology of your organism to improve spliced alignment accuracy [10].

Sequencing Platform Comparison

Table: Sequencing Platform Specifications and Applications

| Platform / Technology | Read Type | Typical Read Length | Key Strengths | Common RNA-seq Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina (Sequencing-by-Synthesis) [13] | Short-read | 50-300 bp | Very high accuracy (~99.9%), ultra-high throughput, low cost per base. | Differential gene expression [5], standard splicing analysis, SNP calling in expressed regions. |

| PacBio HiFi (Circular Consensus Sequencing) [13] | Long-read | 10-25 kb | High accuracy (>99.9%), long read lengths. | Full-length isoform sequencing, novel transcript discovery, fusion detection, allele-specific expression without phasing [6]. |

| Oxford Nanopore (Direct RNA/cDNA) [6] [13] | Long-read | Varies, can be very long | Real-time sequencing, ultra-long reads, detects native RNA modifications. | Isoform quantification, direct RNA-seq (no cDNA bias), detection of RNA modifications (e.g., m6A) [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Kit | Function in RNA-seq Workflow |

|---|---|

| Poly(A) Selection Kit | Enriches for messenger RNA (mRNA) by capturing the poly-adenylated tail. Standard for most gene expression studies but unsuitable for degraded RNA or non-polyadenylated RNAs. |

| rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) to enrich for other RNA species (mRNA, lncRNA). Essential for working with degraded samples (e.g., FFPE) or for total RNA analysis. |

| 10x Genomics Single Cell 3' Kit [8] | Enables single-cell RNA-seq by partitioning individual cells into droplets, where transcripts are barcoded with a unique cell identifier (barcode) and molecular identifier (UMI). |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [5] | Short random nucleotide sequences added to each molecule during library prep. Allows for precise digital counting and accurate removal of PCR duplicates, crucial for degraded or low-input samples. |

| Spike-in RNAs (e.g., ERCC, SIRV, Sequin) [6] | Synthetic RNA controls added to the sample in known quantities. Used to benchmark sequencing protocol performance, assess sensitivity, accuracy, and dynamic range of transcript detection. |

| RSV L-protein-IN-2 | RSV L-protein-IN-2, MF:C32H36N4O5, MW:556.7 g/mol |

| Doxifluridine-d2 | Doxifluridine-d2, MF:C9H11FN2O5, MW:248.20 g/mol |

Experimental Workflow and Decision Logic

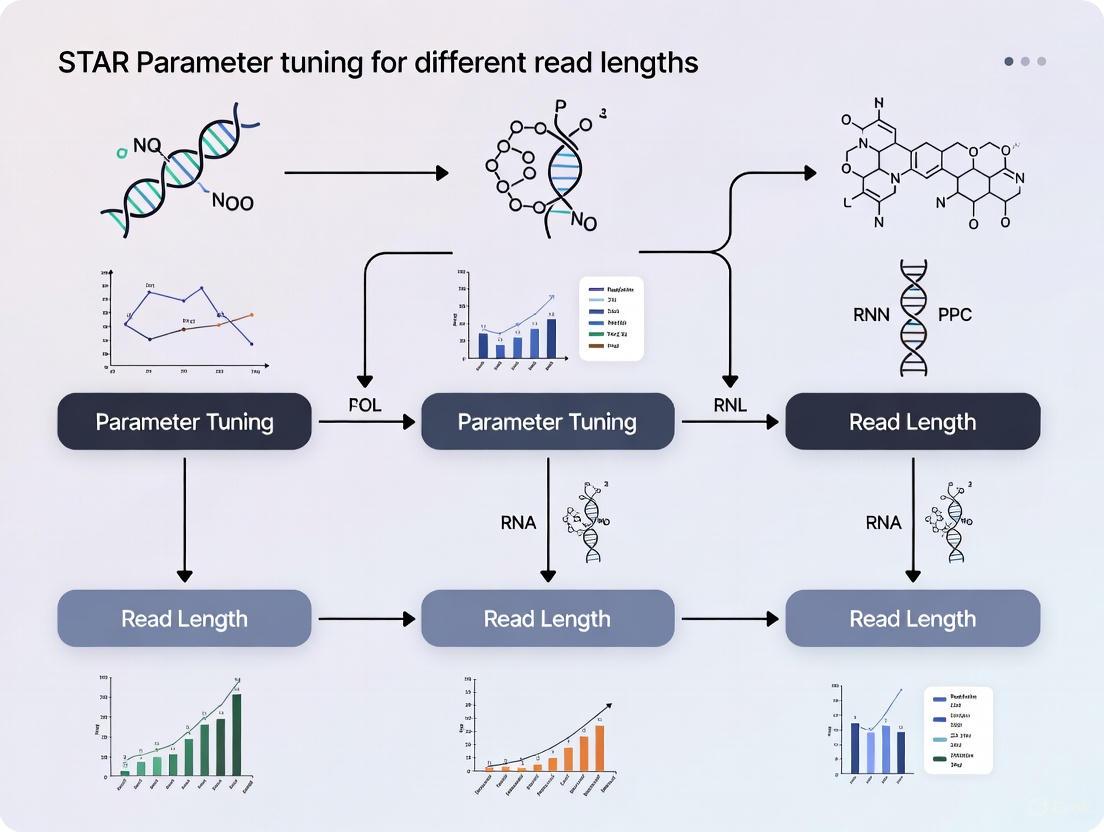

The following diagram outlines the key decision points for selecting an RNA-seq strategy, from experimental goal to data generation, highlighting where STAR parameter tuning is critical.

This guide explains the core mechanics of the STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) aligner and provides practical troubleshooting advice for common experimental challenges, framed within the context of parameter tuning for different read lengths.

Core Mechanics of the STAR Alignment Algorithm

STAR employs a two-step strategy designed for high sensitivity and speed in aligning RNA-seq reads, which may be split across exons by introns [11].

Two-Step Alignment Strategy

STAR uses a sequential two-step process to align reads [11]:

Seed Searching:

- For each read, STAR searches for the longest sequence that exactly matches one or more locations on the reference genome, known as the Maximal Mappable Prefix (MMP).

- The first MMP mapped is called

seed1. STAR then searches the unmapped portion of the read to find the next longest exact match,seed2. This process of sequential searching on unmapped portions is key to its efficiency. - The aligner uses an uncompressed suffix array (SA) for rapid searching against large genomes. If exact matches are not found due to mismatches or indels, it extends the MMPs.

Clustering, Stitching, and Scoring:

- The separate seeds are clustered together based on proximity to a set of reliable "anchor" seeds.

- These clustered seeds are then stitched together to form a complete read alignment. The final alignment is chosen based on a scoring system that accounts for mismatches, indels, and gaps.

The diagram below illustrates this workflow and how different read types are handled.

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

FAQ 1: What does "too short" mean in my STAR alignment report and how can I fix it?

The "too short" error indicates that the final stitched alignment for a read covers a length that falls below STAR's filtering thresholds. This does not refer to the original read length [14]. The primary parameters controlling this filter are --outFilterScoreMinOverLread and --outFilterMatchNminOverLread [14] [15]. Relaxing these parameters from their default of 0.66 can rescue alignments that would otherwise be discarded.

Recommended Experimental Protocol:

- Initial Test: Run STAR with default parameters to establish a baseline.

- Parameter Adjustment: Re-run alignment, lowering

--outFilterScoreMinOverLreadand--outFilterMatchNminOverLreadto0.3or0[14]. - Evaluation: Compare the

Log.final.outfiles from both runs. Monitor changes in the% of reads unmapped: too short,Uniquely mapped reads %, andMismatch rate per base. Be aware that lowering thresholds may increase multi-mapping reads and mismatch rates [15]. - Validation: For a subset of reads rescued by the new parameters, use BLAST to verify their biological relevance and rule out spurious alignment to contaminating sequences [14].

FAQ 2: How should I adjust STAR parameters for shorter reads (e.g., 50 bp or less)?

Short reads require careful parameter tuning to maximize the information gained from limited sequence data.

Key Parameters to Tune for Short Reads:

--scoreGapNoncanand--scoreGapGCAG: Consider increasing gap penalty scores to discourage overly fragmented alignments and ensure only high-confidence splices are called.--seedSearchStartLmax: Reduce this parameter to adjust the initial seed search length for shorter reads [15].--outFilterMatchNmin: Set an absolute minimum alignment length (e.g.,--outFilterMatchNmin 20) to ensure meaningful alignments while still rescuing short valid alignments [15].--alignEndsType: For very short reads, using--alignEndsType EndToEndcan be beneficial, as local alignment may not be feasible [15].--sjdbOverhang: During genome index generation, set--sjdbOverhangtomax(ReadLength)-1. For 50 bp single-end reads, this value should be 49 [11] [15].

FAQ 3: How do I set parameters for non-model organisms with limited annotation?

For organisms without well-defined gene annotations, a two-pass mapping method is recommended to discover novel junctions de novo [16].

Two-Pass Mapping Protocol:

- First Pass: Run STAR on all samples without a GTF file or with a basic one if available. Use the

--twopassMode Basicoption. - Junction Collection: STAR will use the alignments from the first pass to identify and collect novel splice junctions detected across all samples.

- Second Pass: STAR automatically uses the newly discovered set of junctions for a more sensitive and accurate second mapping round. This approach allows the algorithm to leverage information from your specific dataset to improve alignment [16].

Parameter Tuning Guide for Different Read Types

The following tables summarize key parameter adjustments for common experimental scenarios.

Table 1: Core Parameter Adjustments for Read Length

| Parameter | Standard Reads (75-150bp) | Short Reads (<50bp) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

--sjdbOverhang |

100 (default) | max(ReadLength)-1 (e.g., 49) |

Overhang for splice junction database; critical for short reads [11] [15]. |

--outFilterScoreMinOverLread |

0.66 (default) | 0.3 or 0 | Minimum aligned (normalized) score to keep read [14] [15]. |

--outFilterMatchNminOverLread |

0.66 (default) | 0.3 or 0 | Minimum aligned (normalized) length to keep read [14] [15]. |

--seedSearchStartLmax |

50 (default) | Lower value (e.g., 30) | Controls the initial seed search length [15]. |

--alignEndsType |

Local (default) |

EndToEnd |

Can improve alignment for very short fragments [15]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Alignment Issues

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Parameters to Investigate |

|---|---|---|

| High "% unmapped: too short" | Aligned segment is below threshold | Lower --outFilterScoreMinOverLread, --outFilterMatchNminOverLread [14] [15]. |

| Low unique mapping rate | High multimapping due to repeats | Adjust --outFilterMultimapNmax (default 10) or use --outFilterMultimapNmax 1 for unique mappings only [10]. |

| Missed splice junctions | Intron size outside default range | Adjust --alignIntronMin and --alignIntronMax based on organism biology [17] [10]. |

| High mismatch rate | High polymorphism/error rate | Increase --outFilterMismatchNmax or --outFilterMismatchNoverLmax [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for STAR Alignment

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Reference Genome FASTA | The sequence against which reads are aligned. Essential for genome index generation [11] [16]. |

| Annotation GTF File | Contains known gene models and splice junctions. Improves mapping accuracy by informing the aligner of known features [16]. |

| High-Quality RNA-seq FASTQ Files | The raw input data. Quality control (e.g., with FastQC) and adapter trimming are critical pre-processing steps [10]. |

| STAR Aligner Software | The core software package that performs the spliced alignment algorithm [16]. |

| Computational Resources | STAR is memory-intensive. For the human genome, ~30GB RAM is required; 32GB is recommended. Multiple CPU cores significantly speed up the process [16]. |

| Antioxidant agent-13 | Antioxidant agent-13, MF:C12H8N4O7, MW:320.21 g/mol |

| Isocrenatoside | Isocrenatoside, CAS:221895-09-6, MF:C29H34O15, MW:622.6 g/mol |

In the context of optimizing STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) parameters for different read lengths, researchers must account for significant technical variations that arise when the same experiment is performed across different laboratories. High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become a foundational tool for transcriptome analysis, but its reliability for detecting biologically significant changes, especially subtle differential expression, can be compromised by inconsistencies in experimental and bioinformatic workflows [18]. A large-scale multi-center RNA-seq benchmarking study involving 45 independent laboratories revealed greater inter-laboratory variations in detecting subtle differential expressions compared to samples with large biological differences [18]. This article provides a technical support framework, including troubleshooting guides and FAQs, to help researchers identify, understand, and mitigate these sources of variation, thereby ensuring more robust and reproducible results for STAR-based analyses.

Troubleshooting Guides: Identifying and Resolving Common Issues

Guide 1: Addressing Inconsistent Differential Expression Results Across Labs

Problem: Your laboratory identifies a set of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using STAR-aligned data, but a collaborating lab, analyzing the same biological samples, reports a different DEG list.

Explanation: This inconsistency often stems from variations in the entire RNA-seq workflow, not just the alignment step. A multi-center study found that both experimental factors (like mRNA enrichment and library strandedness) and bioinformatics factors (each step of the pipeline) are primary sources of variation [18].

Solution:

- Standardize Experimental Protocols: Agree upon and document a common protocol for key steps, especially:

- mRNA Enrichment: Use the same method (e.g., poly-A selection vs. rRNA depletion) across all labs.

- Library Strandedness: Ensure all labs use the same stranded or un-stranded protocol.

- Harmonize Bioinformatics Pipelines: For STAR alignment and downstream analysis, use the same:

- STAR version and genome indices.

- Gene annotation file (GTF).

- Downstream quantification and differential expression tools.

- Utilize Reference Materials: Incorporate standardized RNA reference materials, such as those from the Quartet project or the MAQC consortium, into your sequencing batches. These provide "ground truth" for benchmarking your lab's performance against others [18].

Guide 2: Optimizing STAR for Different Read Lengths in a Consortium

Problem: Your multi-lab project must integrate data from different sequencing platforms that produce varying read lengths (e.g., short-read Illumina vs. long-read PacBio), making consistent alignment with STAR challenging.

Explanation: The optimal parameters for STAR, particularly the --sjdbOverhang option, depend on read length. Using a default value for data of varying lengths can reduce the accuracy of splice junction detection [16]. Furthermore, the technologies themselves have inherent biases; for example, short reads offer higher sequencing depth while long reads provide full-length isoform resolution [8] [19].

Solution:

- Set the

--sjdbOverhangParameter Correctly: This parameter should be set to the maximum read length minus 1. If reads are of variable length, set it to 100 as a safe default for most mammalian genomes [16]. - Employ a Two-Pass Mapping Strategy: For the most accurate discovery of novel splice junctions, especially with diverse datasets, use STAR's 2-pass mapping. This involves:

- First Pass: Run STAR on all samples to discover novel junctions.

- Second Pass: Re-run STAR, incorporating the newly discovered junctions from the first pass as annotations for all samples [16].

- Acknowledge Platform Strengths: Do not expect perfect concordance between long- and short-read data. Long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio Kinnex) allows for the identification of novel isoforms and can filter out artefacts identifiable only from full-length transcripts, which can affect gene count correlations with short-read data [8].

Guide 3: Diagnosing Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Gene Expression Data

Problem: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of your gene expression data shows poor separation of sample groups, indicated by a low Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), suggesting high technical noise is obscuring biological signals.

Explanation: A low PCA-based SNR indicates a diminished ability to distinguish biological signals from technical noise in replicates. This is particularly problematic when trying to detect subtle differential expression, as is often the case in clinical diagnostics for different disease subtypes or stages [18].

Solution:

- Calculate the SNR: Use the PCA-based SNR metric to quantitatively assess data quality. The multi-center study found that low SNR values (e.g., less than 12 for Quartet samples) were indicative of quality issues [18].

- Identify Outliers: Use the SNR calculation to identify and exclude individual sample replicates that are low-quality outliers, which can significantly improve the overall SNR [18].

- Review Library Preparation: Low SNR is often linked to issues in library preparation. Ensure consistent execution of the experimental protocol and use high-quality input RNA.

Table: Key Metrics for Assessing Inter-Laboratory RNA-seq Performance

| Metric | Description | Interpretation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCA-based Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Measures ability to distinguish biological signals from technical noise. | Low values (<12) indicate high technical variation obscuring biological effects. | [18] |

| Correlation with Reference Datasets | Pearson correlation of gene expression with TaqMan or Quartet reference data. | Lower correlations (e.g., 0.825 vs 0.876) indicate challenges in accurate quantification. | [18] |

| Gene Expression Accuracy | Accuracy of absolute gene expression measurements against ground truth. | Highlights challenges in quantifying a broader set of genes accurately. | [18] |

| Alignment Accuracy | Proportion of reads uniquely mapped to the genome. | Foundational for downstream analysis; high accuracy (>90%) is achievable with STAR. | [16] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Protocol: Basic STAR Alignment for RNA-seq Reads

This protocol is the foundational step for mapping RNA-seq reads to a reference genome, critical for subsequent gene expression analysis [16].

Necessary Resources:

- Hardware: Computer with Unix/Linux/Mac OS X. For a human genome, at least 30GB RAM (32GB recommended) and >100GB free disk space.

- Software: Latest STAR software release.

- Input Files:

- Reference genome indices (pre-built or generated by user).

- Annotation file in GTF format (e.g., from Ensembl).

- RNA-seq data in FASTQ format (gzipped or uncompressed).

Steps:

- Create and Navigate to a Run Directory:

Execute the STAR Mapping Command: The following command maps paired-end, gzipped FASTQ files.

Monitor Progress: STAR will print status messages to the screen. Detailed progress statistics (reads processed, mapping rates) are updated in the

Log.progress.outfile.- Output: Successful execution produces several output files, including a SAM/BAM file with alignments, which serves as the basis for downstream quantification and analysis [16].

Protocol: Multi-Center Performance Assessment Using Reference Materials

This methodology details how to systematically assess technical performance and variation across multiple laboratories, as performed in a large-scale benchmarking study [18].

Necessary Resources:

- Reference Materials: Quartet RNA reference materials (D5, D6, F7, M8) and/or MAQC samples (A, B).

- Spike-in Controls: ERCC RNA spike-in mixes.

- Standardized Sample Panel: Includes parent samples and defined mixtures (e.g., T1: 3:1 mix of M8 and D6).

Steps:

- Study Design: Distribute a panel of reference RNA samples (including technical replicates) to all participating laboratories. Each lab uses its in-house RNA-seq protocol and bioinformatics pipeline.

- Data Generation: Each laboratory performs library preparation and sequencing according to their standard practices. The study should aim for high coverage (e.g., the benchmark generated over 120 billion reads from 1080 libraries) [18].

- Performance Assessment: Analyze the collected data using a multi-faceted framework:

- Data Quality: Calculate the PCA-based Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR).

- Expression Accuracy: Measure correlation of gene expression with orthogonal reference datasets (e.g., TaqMan) and spike-in concentrations.

- DEG Accuracy: Assess the accuracy of detected differentially expressed genes against the reference DEGs.

- Source Variation Analysis: Systematically evaluate factors in 26 experimental processes and 140 bioinformatics pipelines to identify primary sources of inter-laboratory variation [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical factors causing performance variation in RNA-seq across labs? A1: According to a large-scale benchmark, the primary sources of variation are experimental factors (especially mRNA enrichment method and library strandedness) and every step of the bioinformatics pipeline. The specific analysis pipeline used had a profound influence on the final results [18].

Q2: How can we ensure our STAR alignment is optimized for our specific read length?

A2: The most critical parameter is --sjdbOverhang. It should be set to your maximum read length minus 1. For most mammalian genomes with reads of 100bp or longer, a value of 100 is recommended and safe. Always use a known annotation file (--sjdbGTFfile) and consider a 2-pass mapping approach for novel junction discovery [16].

Q3: Our lab is considering switching to long-read RNA-seq. How comparable is it to short-read data? A3: Data from the two methods are highly comparable for gene-level counts, but platform-dependent biases exist. Short-read sequencing provides higher sequencing depth, while long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio) provides isoform resolution and can filter out artefacts only identifiable from full-length transcripts. This filtering can, however, reduce gene count correlation between the two methods [8]. Long-read tools are improving but can still lag behind short-read tools in quantification accuracy due to throughput and error limitations [20].

Q4: What quality control metrics are most important for identifying issues in a multi-lab study? A4: Beyond standard QC metrics, the PCA-based Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a robust metric for characterizing the ability to distinguish biological signals from technical noise. Additionally, consistently track correlation with reference datasets (e.g., Quartet or TaqMan) and the accuracy of absolute gene expression measurements [18].

Q5: Why should we use reference materials like the Quartet samples? A5: Reference materials provide a "ground truth" for benchmarking. The Quartet samples, for instance, have small biological differences that mimic the challenge of detecting subtle differential expression in clinical samples. Using them allows labs to quality control their workflows at this challenging level, which is not possible with samples that have large biological differences [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for RNA-seq Benchmarking and STAR Alignment

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Quartet Reference Materials | Stable RNA reference materials with small biological differences for benchmarking subtle differential expression detection. | Quartet Project [18] |

| MAQC Reference Materials | RNA reference materials (samples A & B) with large biological differences for initial pipeline validation. | MAQC Consortium [18] |

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | Synthetic RNA spikes at known concentrations used to assess technical accuracy and dynamic range of RNA-seq measurements. | External RNA Control Consortium [18] |

| STAR Aligner | Ultra-fast and accurate software for aligning RNA-seq reads to a reference genome, capable of detecting spliced and novel junctions. | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR [16] |

| PacBio Kinnex / Iso-Seq | Long-read RNA sequencing kits and platforms for full-length transcript sequencing and isoform discovery, enabling artefact filtering. | Pacific Biosciences [21] [8] |

| Reference Genome & Annotation | High-quality reference genome sequence and gene annotation file (GTF) essential for accurate read mapping and quantification. | ENSEMBL, GENCODE [16] |

| Ferroptosis-IN-6 | Ferroptosis-IN-6, MF:C15H17NO, MW:227.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Egfr-IN-79 | Egfr-IN-79, MF:C23H16ClN3O3, MW:417.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Within the framework of a comprehensive thesis on optimizing STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) alignment for diverse experimental designs, this guide addresses a recurring analytical challenge: the systematic tuning of key parameters to accommodate varying RNA-seq read lengths. The alignment of sequencing reads is a foundational step in RNA-seq analysis, directly influencing all subsequent interpretations of gene expression, splicing, and novel transcript discovery. The STAR aligner, while exceptionally fast and sensitive, possesses numerous parameters whose optimal settings are intimately connected to the specifics of the input data, particularly read length. Misconfiguration of these parameters can introduce substantial biases, leading to inaccurate quantification and potentially invalid biological conclusions. This technical support document, structured around frequently asked questions (FAQs) and troubleshooting guides, provides a detailed examination of three pivotal parameters: --sjdbOverhang, --seedSearchStartLmax, and --alignIntronMax. By synthesizing community knowledge, developer recommendations, and empirical evidence, we aim to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the protocols and insights necessary to achieve robust, reproducible alignments across a spectrum of read lengths, from very short (<50 bp) to long-read sequencing technologies.

Core Parameter Specifications and Recommendations

Parameter --sjdbOverhang: Optimizing Splice Junction Detection

Question: What is the purpose of the --sjdbOverhang parameter, and how should I set it for my read length?

Answer: The --sjdbOverhang parameter is used during genome index generation. It specifies the length of the genomic sequence around annotated splice junctions to be included in the splice junctions database, which significantly improves the accuracy of aligning reads that cross splice junctions [22]. The parameter defines how many bases of the read sequence overhang the splice junction on each side.

Recommendation: The established best practice is to set --sjdbOverhang to ReadLength - 1 [11] [23]. For instance, for standard Illumina 2x100 bp paired-end reads, the ideal value is 100 - 1 = 99. In cases where your reads are of varying lengths, the recommendation is to use max(ReadLength) - 1 [11]. For most standard experiments, the default value of 100 will work similarly to the ideal value [11] [22]. For very short reads (e.g., 20-30 bp), the same logic applies: use the maximum read length minus one [24].

Table: Recommended --sjdbOverhang Values for Common Read Lengths

| Read Type | Read Length | Recommended --sjdbOverhang | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-read SE | 50 bp | 49 | Ideal value is read length - 1 [23] |

| Short-read PE | 75 bp | 74 | Ideal value is read length - 1 |

| Short-read PE | 100 bp | 99 | Ideal value is read length - 1 [11] |

| Varying Lengths | 20-150 bp | 149 | Use max(ReadLength) - 1 [11] |

| Long-read (e.g., Nanopore) | >1000 bp | 100 (or default) | The default of 100 is often sufficient; may require testing [22] |

Parameter --seedSearchStartLmax: Controlling Seed Search for Varied Read Lengths

Question: When and why should I modify the --seedSearchStartLmax parameter, especially for non-standard read lengths?

Answer: The --seedSearchStartLmax parameter controls the maximum length of the alignment "seed," which is the initial exactly-matching sequence STAR uses to find a candidate genomic location [25]. During the seed searching step, STAR splits reads into pieces no longer than this value. The default is 50, which is suitable for longer reads but can be problematic for very short reads (where 50 bp exceeds the total read length) or for optimizing the alignment of longer reads.

Recommendation: For a standard experiment with reads of 75 bp or longer, the default value is typically adequate. The primary need for adjustment arises with very short reads. For reads around 25-30 bp, it is advisable to set --seedSearchStartLmax to a lower value, such as 10-12, to ensure effective seed generation [24]. Alternatively, you can use --seedSearchStartLmaxOverLread 0.5, which will split each read in half, providing a more universal setting for mixed or short read lengths [24]. If both parameters are set, the shorter value for each read will be used.

Figure 1: Decision workflow for configuring --seedSearchStartLmax based on read length.

Parameter --alignIntronMax: Setting Biological Limits for Spliced Alignment

Question: How does the --alignIntronMax parameter influence alignment, and what values are appropriate for different organisms?

Answer: The --alignIntronMax parameter defines the maximum intron size that STAR will consider during alignment. Reads that would require a spliced alignment with an intron larger than this value will not be mapped as spliced. This is critical for both limiting spurious alignments and respecting the known biology of the organism you are studying.

Recommendation: The default value of --alignIntronMax is 1,000,000 (1 Mb), which is tuned for mammalian genomes where very large introns exist [15] [17]. For organisms with smaller genomes and smaller introns, such as plants, yeast, or specific fish models, this value should be decreased significantly to improve mapping accuracy and speed. Consult organism-specific databases or annotations (e.g., the GTF file used for genome generation) to determine a biologically realistic maximum intron size. For example, in the plant Physcomitrella patens, a value much lower than 500,000 is appropriate [17]. For troubleshooting high rates of unmapped reads, testing values like 100,000 has been used [15].

Table: Recommended --alignIntronMax Settings by Organism Type

| Organism Type | Recommended --alignIntronMax | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Mammalian (e.g., Human, Mouse) | 1,000,000 (Default) | Accommodates known large introns [26] |

| Fish Models (e.g., Zebrafish) | 100,000 - 500,000 | Based on known genome biology; used in troubleshooting [15] |

| Plants (e.g., Physcomitrella patens) | < 500,000 | Organisms with generally smaller introns [17] |

| Yeast | 1,000 - 5,000 | Very small genomes with minimal introns |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Scenarios

Scenario 1: High Percentage of "Unmapped - Too Short" Reads

Observed Problem: A high percentage (e.g., 40-55%) of reads are reported as "UNMAPPED: TOO SHORT" in the final STAR log file [15].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify Read Quality: Confirm that read trimming has been performed to remove adapters and low-quality bases. High-quality reads should be the input for alignment [15].

- Check for Contamination: BLAST a subset of unmapped reads against the NCBI nt database to identify potential contamination from rRNA, mtDNA, or other species [15].

- Inspect Parameter Settings: Mismatched parameter settings are a common cause.

Solutions and Parameter Adjustments:

- Adjust Alignment Length Filters: The default filters requiring a long aligned length can be too stringent for short reads. Relax these filters to allow alignments with shorter matches [15].

- Example:

--outFilterScoreMinOverLread 0 --outFilterMatchNminOverLread 0 --outFilterMatchNmin 20allows alignments with 20 or more matching bases. Note that this may increase multimapping rates and mismatch rates [15].

- Example:

- Review

--seedSearchStartLmax: For short reads (e.g., 36-50 bp), ensure--seedSearchStartLmaxis set lower than the read length (e.g., to 10-30) as described in Section 2.2 [24] [15]. - Ensure

--sjdbOverhangis Correct: When generating a new index, verify that--sjdbOverhangis set tomax(ReadLength)-1[15]. This optimizes the splice junction database for your specific data.

Scenario 2: Read Length Bias in Comparative Studies

Observed Problem: When analyzing multiple samples with different read lengths (e.g., 40 bp, 75 bp, 150 bp), Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots show a strong separation of samples by read length rather than biological group [26].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Confirm Adapter Trimming: Longer reads are more likely to include adapter sequences if not properly trimmed. This can prevent them from mapping correctly. Use tools like Trimmomatic or STAR's built-in clipping functions [26].

- Compare Quantification: Determine if the bias is introduced during alignment or during read counting. Compare results from different quantification tools (e.g., STAR's

--quantMode, HTSeq-count, featureCounts). - Investigate Anomalous Expression: Check if the genes driving the separation are features like processed pseudogenes, which might be artifacts of incomplete alignment [26].

Solutions and Parameter Adjustments:

- Trim All Reads to a Uniform Length: The most straightforward solution is to use the

--clip3pNbases <N>option in STAR to trim all reads to a common length (e.g., 40 bp) before alignment. This has been shown to effectively remove the length-based batch effect [26]. - Avoid Overly Permissive Parameters: As recommended by the STAR developer, avoid using parameters like

--outFilterScoreMinOverLread 0.33and--outFilterMatchNminOverLread 0.33, as they can allow low-quality or discordant alignments that are more likely to be mis-mappings or artifacts, potentially contributing to bias [26]. - Validate with an Alternative Pipeline: Compare your STAR results with those from another aligner/quantification tool (e.g., CLC, HISAT2/HTSeq) to see if the bias is reproducible [26].

Scenario 3: Handling Paired-End Reads with Different Lengths

Observed Problem: After processing (e.g., UMI/barcode removal), the two mates in a paired-end library can end up being different lengths. Users may observe high "unmapped - too short" rates in this context [27].

Solution:

STAR can handle mates of different lengths. The key is to ensure that the remaining sequence for each mate is of sufficient length and quality for alignment. The parameters discussed in Scenario 1, particularly relaxing the --outFilterMatchNmin and adjusting --seedSearchStartLmax, are also applicable here. There is no need for a special mode; simply input the two fastq files as normal.

Table: Key Software and Data Resources for STAR Alignment

| Resource | Function | Usage in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| STAR Aligner | Spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads to a reference genome. | Primary tool for executing the alignment workflow with tuned parameters [11] [25]. |

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | The genomic sequence of the organism under study. | Used with --genomeFastaFiles during the genomeGenerate step to create the alignment index [11]. |

| Annotation File (GTF) | File containing annotated gene and transcript structures, including splice junctions. | Used with --sjdbGTFfile during the genomeGenerate step to build the splice junction database [11]. |

| Trimmomatic / Cutadapt | Read quality control and adapter trimming tools. | Essential pre-alignment step to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases, ensuring high-quality input for STAR [15] [26]. |

| RSEM / featureCounts | Quantification tools for estimating gene and isoform abundance from aligned reads. | Downstream quantification after alignment; STAR can also perform basic counting with --quantMode [28]. |

| SAMtools | Utilities for manipulating and indexing aligned read files (BAM/SAM). | Used to index the final BAM file for visualization and downstream analysis [11]. |

This guide has detailed the critical importance of tuning STAR's parameters to match the specific characteristics of your RNA-seq data, with a particular focus on read length. The following integrated protocol summarizes the key steps for a successful alignment experiment.

Figure 2: Integrated workflow for STAR parameter tuning and alignment.

Consolidated Best Practices Protocol:

- Pre-alignment Quality Control: Always perform quality and adapter trimming using a tool like Trimmomatic. This is the most critical step to ensure high-quality input data [15] [26].

- Genome Index Generation with

--sjdbOverhang: When generating a custom genome index, always set--sjdbOverhangtomax(ReadLength) - 1. For most standard experiments (50-150 bp), the default of 100 is a safe and effective choice [11] [22]. - Organism-Specific

--alignIntronMax: Do not blindly use the default intron size for non-mammalian organisms. Consult annotation files and literature to set a biologically realistic value for--alignIntronMaxto improve accuracy [17]. - Seed Search Tuning for Short Reads: If your reads are shorter than 75 bp, proactively adjust

--seedSearchStartLmax(to a value like 10) or use--seedSearchStartLmaxOverLread 0.5to ensure robust seed finding [24]. - Validation and Troubleshooting: After alignment, carefully examine the

Log.final.outfile. A high percentage of "unmapped - too short" reads is a primary indicator that parameter re-tuning, as outlined in the troubleshooting scenarios, is necessary [15].

Practical Implementation: STAR Parameter Optimization Strategies for Specific Read Length Ranges

How does read length impact my STAR alignment strategy for standard Illumina reads?

For standard Illumina reads (50-150bp), your alignment strategy must balance sufficient unique mappability with the ability to accurately span splice junctions. Longer reads within this range (e.g., 150bp) provide more sequence context, which improves the confidence of unique alignments, especially in complex or repetitive regions of the genome [29]. This is crucial for detecting structural rearrangements in paired-end sequencing [29]. Conversely, shorter reads (e.g., 50-75bp) are often sufficient for gene-level counting studies and can be more cost-effective [29] [30].

A key parameter in STAR that is directly influenced by your read length is --sjdbOverhang. Its ideal value is set to your read length minus 1. For reads of varying lengths, use max(ReadLength)-1 [11]. For a mix of 50bp and 150bp reads, a value of 149 is appropriate. In most cases, a default value of 100 will work similarly to the ideal value [11].

What are the recommended baseline STAR parameters for 50-150bp reads?

The table below summarizes the key parameters for standard RNA-seq experiments with 50-150bp reads. These are a starting point for "long RNA-seq" (e.g., mRNA and lincRNA), and differ from parameters used for small RNA-seq (<200bp) [31].

Table 1: Recommended Baseline STAR Parameters for 50-150bp Reads

| Parameter | Recommended Setting for 50-150bp Reads | Function and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

--sjdbOverhang |

ReadLength - 1 (e.g., 149 for 150bp reads) | Defines the length of the genomic sequence around annotated junctions used for constructing the splice junction database. Critical for accurate alignment of reads spanning splice sites [31] [11]. |

--outFilterMismatchNoverLmax |

0.05 (or 0.04) | Sets the maximum proportion of mismatched bases per read relative to its mapped length. A value of 0.05 means no more than 5% of the aligned length can be mismatches. This automatically adjusts the stringency based on read length [31]. |

--outFilterMatchNmin |

Do not set for long RNA-seq (use default) | In long RNA-seq, you should not use parameters that prohibit splicing or allow for very short alignments, which are recommended for small RNA-seq [31]. |

--alignIntronMax |

Do not set for long RNA-seq (use default) | In long RNA-seq, you should not use parameters that prohibit splicing or allow for very short alignments, which are recommended for small RNA-seq [31]. |

--outFilterMultimapNmax |

10 (Default) | This is the maximum number of loci a read is allowed to map to. Reads aligning to more locations are considered unmapped. The default is generally acceptable, though shorter reads (e.g., 35bp) will naturally have a higher multimapping proportion [31]. |

--outSAMtype |

BAM SortedByCoordinate | Outputs alignments directly in sorted BAM format, which is efficient and ready for downstream analysis [11]. |

--readFilesIn |

Read1 Read2 (for paired-end) | Specifies the input files. For paired-end reads, list both files [11]. |

How should I handle samples with different read lengths in the same study?

When your dataset contains libraries sequenced with different read lengths (e.g., 75bp and 150bp), you have two primary strategies:

- Separate Alignment and Merge Results: Process the different datasets separately through alignment and then merge the results at the count level. Before merging, it is critical to assess for batch effects using tools like PCA (e.g., with Deeptools

plotPCA) or correlation matrices (e.g., with DESeq2) to ensure the sequencing types do not introduce major biases [32]. - Trim to Uniform Length and Combine: Trim all longer reads down to the length of your shortest reads (e.g., trim 150bp reads to 75bp) before performing a single alignment. This is the most stringent approach to ensure mappability is consistent across all samples, which is especially important for differential expression analysis [31] [32].

STAR cannot natively process paired-end and single-end reads of different lengths simultaneously in a single run. The strategies above are necessary to handle such mixed datasets [32].

What is a standard workflow for aligning 50-150bp reads with STAR?

The following diagram illustrates the two main steps for aligning RNA-seq reads with STAR: generating a genome index and performing the read alignment.

A high percentage of my reads are unmapped or multi-mapped. How should I troubleshoot this?

A high rate of unmapped or multi-mapped reads, particularly with shorter reads (e.g., 35bp), is a common issue [31]. The following troubleshooting steps are recommended:

- For Unmapped Reads (~15-20% is often not a major issue [31]):

- Check for Contamination: Manually BLAST a subset (e.g., 10 sequences) of the unmapped reads against the full NCBI nucleotide database. Hits against other species may indicate sample contamination [31].

- Trim Adapters: Adapter contamination can prevent reads from aligning. Use STAR's internal trimer with

--clip3pAdapterSeq(specifying the first 10-20 bases of the 3' adapter sequence) or a dedicated tool likecutadapt[31]. - Map Reads Separately: For paired-end data, try mapping Read 1 and Read 2 separately to see if the number of unmapped reads decreases significantly, which can provide diagnostic information [31].

- For Multi-mapped Reads:

- Acknowledge the Limitation: The proportion of multimappers is inherently higher for shorter reads and is largely determined by the transcript species in your sample (e.g., rRNA, paralogous genes). It cannot be drastically changed with mapping parameters alone [31].

- Check Wet-lab Protocols: A very high percentage of multimappers may indicate issues with wet-lab procedures, such as incomplete ribosomal RNA depletion [31].

- Adjust Multimapping Threshold: You can make the filter more stringent by reducing

--outFilterMultimapNmaxfrom the default of 10 to a lower number, but this will result in more reads being lost.

Which key reagents and tools are essential for these experiments?

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Illumina Sequencing Kits | Generate the sequencing data. Common for 50-150bp outputs include MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (2x75bp) and NovaSeq 6000 S1/S2/S4 flow cells (2x100bp, 2x150bp) [33] [34]. |

| STAR Aligner | A splice-aware aligner designed for accurate and fast alignment of RNA-seq reads to a reference genome [11]. |

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | The reference sequence for the organism you are studying (e.g., GRCh38 for human, GRCm39 for mouse) against which reads are aligned [35] [11]. |

| Gene Annotation (GTF) | A file containing the coordinates of known genes, transcripts, and exon boundaries. This is used by STAR during genome indexing to create a database of splice junctions [35] [11]. |

| Cutadapt/fastp | Tools for quality control and adapter trimming of raw sequencing reads, which is a critical pre-processing step [31] [36]. |

| SAMtools | A suite of programs for manipulating alignments in SAM/BAM format, such as sorting, indexing, and extracting unmapped reads [31]. |

Short RNA sequencing (sRNA-seq) is a specialized next-generation sequencing (NGS) application designed to profile small non-coding RNA molecules approximately 20-40 nucleotides in length. This technology enables researchers to comprehensively identify and quantify various small RNA types, including microRNAs (miRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), and other non-coding RNAs [37]. Unlike standard RNA-seq that targets messenger RNA, sRNA-seq employs unique library preparation methods that specifically recognize the 5' and 3' ends of RNA fragments processed by DICER, allowing for precise capture of these small molecules [38].

The importance of sRNA-seq in biological research and drug development stems from the crucial regulatory roles these molecules play in cellular processes. miRNAs, typically 19-25 nucleotides long, are particularly important as they mediate post-transcriptional regulation by binding to target mRNAs, thereby influencing gene expression [37]. Their disease-specific profiles and presence in various biofluids make them valuable non-invasive biomarkers for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic development [39]. The ability of sRNA-seq to provide genome-wide profiling of both known and novel miRNA variants, including biologically active isoforms called isomiRs, has made it an indispensable tool for researchers exploring the complex regulatory networks governing development, cellular differentiation, and disease pathogenesis [39] [37].

FAQ: Small RNA Sequencing Experimental Design

Q1: What are the key differences between standard RNA-seq and small RNA-seq?

Standard RNA-seq and small RNA-seq differ significantly in their library preparation methods and applications. Standard RNA-seq typically uses either poly-A selection or ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion to enrich for messenger RNA and long non-coding RNA, followed by fragmentation and adapter ligation. In contrast, small RNA-seq uses kits that specifically recognize the 5' and 3' ends of mature small RNA molecules after DICER processing without requiring fragmentation [38]. While standard RNA-seq provides a snapshot of the coding transcriptome, small RNA-seq enables specific detection of miRNAs, siRNAs, piRNAs, and snoRNAs, making it essential for studying RNA interference and post-transcriptional regulation [37].

Q2: Can I prepare both small RNA and standard RNA libraries from the same total RNA sample?

Yes, you can prepare both library types from the same total RNA preparation if sufficient input material is provided and the total RNA sample contains small RNAs. However, since Standard RNA-Seq and Small RNA-Seq use different library preparation methods, the total RNA sample must be split and processed separately for each application [38].

Q3: What are the specific RNA quality requirements for small RNA sequencing?

Requirements depend on the library preparation method. For oligo(dT)-primed kits (like SMARTer Ultra Low kits), high-quality input RNA with RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥8 is required to ensure selective and efficient full-length cDNA synthesis from mRNAs. For random-primed kits (like SMARTer Stranded kits or SMARTer Universal Low Input RNA Kit), degraded RNA with RIN as low as 2-3 can be used, making them suitable for FFPE samples. In all cases, total RNA should be free of genomic DNA and contaminants that could interfere with reverse transcription [40].

Q4: Why is ribosomal RNA removal necessary for some small RNA-seq protocols?

For protocols utilizing random priming for first-strand cDNA synthesis (such as the SMARTer Universal Low Input RNA Kit), ribosomal RNA (rRNA) removal is critical because if rRNA is not depleted, up to 90% of sequencing reads are expected to map to rRNA, drastically reducing the useful sequencing depth for target small RNAs [40]. For oligo(dT)-primed protocols, rRNA removal is typically not required as the method selectively targets polyadenylated RNAs.

Q5: How many sequencing reads are recommended for small RNA-seq experiments?

For small RNA sequencing, the required read depth depends on the experimental goals. For miRNA profiling, 5-10 million reads per sample often provides sufficient coverage. However, for discovery of novel small RNAs or for detecting low-abundance species, higher sequencing depths of 20-30 million reads per sample may be necessary. The appropriate depth should be determined based on genome complexity and the specific research objectives [38].

Specialized STAR Aligner Settings for Short Reads

When analyzing short RNA sequencing data (20-40bp) with STAR, standard parameters designed for longer reads must be adjusted to accommodate the unique characteristics of small RNAs. The following settings optimize alignment sensitivity and accuracy for short RNA species:

Table: Recommended STAR Parameters for Short RNA Sequencing (20-40bp)

| Parameter | Standard Setting | sRNA-Optimized Setting | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

--alignEndsType |

EndToEnd |

Local |

Allows soft-clipping of adapter sequences and improves mapping of partial fragments |

--seedSearchStartLmax |

50 | 15 | Reduces search start points for short reads, decreasing false alignments |

--outFilterScoreMin |

0 | 10 | Sets minimum alignment score to filter low-quality alignments common with short reads |

--outFilterMatchNmin |

0 | 15-18 | Sets minimum matched bases based on read length (approximately 75% of read length) |

--outFilterMismatchNmax |

10 | 2-4 | Reduces allowed mismatches appropriate for short read lengths |

--alignSJoverhangMin |

5 | 3 | Reduces minimum overhang for spliced junctions as small RNAs typically don't span junctions |

--alignSJDBoverhangMin |

3 | 2 | Similar reduction for annotated splice junctions |

--outSAMattributes |

Standard | All |

Includes all SAM attributes for downstream miRNA analysis |

These parameter adjustments address the specific challenges of aligning short RNA sequences. The --alignEndsType Local setting is particularly important as it enables soft-clipping of residual adapter sequences that are common in sRNA-seq data due to the short insert sizes [41]. The reduced --seedSearchStartLmax optimizes the alignment algorithm for shorter seeds appropriate for 20-40bp reads, while the stricter --outFilterMismatchNmax accounts for the lower probability of sequencing errors in shorter sequences.

For comprehensive analysis, STAR should be run with the --quantMode GeneCounts option to generate expression counts directly during alignment [41]. Additionally, when working with sRNA-seq data, it's recommended to disable typical RNA-seq filters that assume longer reads, such as --outFilterType BySJout, as small RNAs rarely contain splice junctions.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Table: Common Small RNA Sequencing Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Troubleshooting Steps | STAR Parameter Adjustments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low mapping rates | Incorrect read length parameters, adapter contamination | Verify read length specifications; perform adapter trimming; validate RNA quality | Increase --outFilterScoreMin; adjust --scoreDelOpen and --scoreDelBase parameters |

| Biased miRNA representation | Ligation bias during library prep, PCR amplification bias | Use protocols with randomized adapters; incorporate UMIs; optimize PCR cycles | Use --outSAMattributes All to retain UMI information; employ --outFilterMultimapNmax 1 for unique mapping |

| Detection of few miRNAs | Low input material, suboptimal RNA quality, insufficient sequencing depth | Increase input RNA; verify RNA quality (RIN >8); increase sequencing depth | Decrease --outFilterScoreMin to 5; reduce --outFilterMismatchNmax to 3 |

| High ribosomal RNA contamination | Inefficient rRNA depletion | Optimize rRNA removal protocol; use ribodepletion kits designed for small RNAs | Pre-filter rRNA sequences using --genomeLoad and custom rRNA sequences |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Technical variation in library prep, batch effects | Standardize library preparation protocol; include technical replicates; use UMIs | Use identical STAR parameters across all samples; implement --outFilterScoreMinOverLread and --outFilterMatchNminOverLread for length-normalized filtering |

The variability in protocol performance highlighted in multi-center studies emphasizes the importance of standardized processing [18]. Laboratory-specific factors including mRNA enrichment methods, library preparation protocols, and sequencing platforms all contribute to inter-laboratory variations in detecting subtle differential expressions [18]. Implementing Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) is particularly valuable for correcting PCR amplification bias, which is a significant source of technical variation in sRNA-seq data [39] [38].

When troubleshooting consistently low mapping rates across multiple samples, consider that recent benchmarking studies have revealed substantial inter-laboratory variations in RNA-seq performance, with experimental factors such as mRNA enrichment and strandedness emerging as primary sources of variation [18]. In such cases, examining the distribution of read lengths in the raw FASTQ files can help determine if the issue stems from library preparation rather than alignment parameters.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Small RNA Library Preparation Protocol

The construction of cDNA libraries for small RNA sequencing involves several critical steps that differ significantly from standard RNA-seq protocols. The following workflow outlines the key stages:

Step-by-Step Protocol:

RNA Sample Collection and Quality Control: Extract total RNA from your biological sample (cells, tissue, or biofluids). Assess RNA quality using an Agilent Bioanalyzer with the RNA 6000 Pico Kit to ensure RIN ≥8 for high-quality requirements. For degraded samples (FFPE), RIN of 2-3 is acceptable with random-primed protocols [40].

3' Adapter Ligation: Ligate the 3' adapter to the RNA molecules using T4 RNA Ligase 2, truncated. This enzyme shows preference for adenylated 3' adapters and reduces ligation bias compared to non-truncated versions [39].

5' Adapter Ligation: Ligate the 5' adapter using T4 RNA Ligase. Consider using protocols with randomized adapter sequences to minimize ligation bias, which is a significant source of technical variation in sRNA-seq [39].

Reverse Transcription: Perform reverse transcription using a primer complementary to the 3' adapter. Protocols incorporating Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) at this stage are recommended to correct for PCR amplification biases [39] [38].

cDNA Amplification: Amplify the cDNA using a limited number of PCR cycles (typically 10-15) to prevent overamplification. The optimal cycle number should be determined empirically for each sample type.

Size Selection: Purify the amplified libraries to select fragments in the 150-200bp range, which corresponds to the adapter-ligated small RNAs. This step removes adapter dimers and other non-specific products.

Library QC and Quantification: Assess the final library quality using the Agilent Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA kit or similar methods. Quantify libraries by qPCR for accurate pooling and sequencing.

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

The standard analysis pipeline for small RNA sequencing data includes the following steps, with particular attention to STAR alignment configuration:

Table: Small RNA-seq Bioinformatics Pipeline

| Step | Tool Options | Key Parameters | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | FastQC, MultiQC | Check for adapter contamination, read length distribution | QC report, per-base sequence quality |

| Adapter Trimming | cutadapt, fastp | -a [3'adapter] -u [5'adapter] -m 18 -M 40 | Trimmed FASTQ, length-filtered reads |

| Alignment | STAR | Parameters detailed in Section 3 | BAM files with alignment information |

| Quantification | featureCounts, HTSeq | -t exon -g gene_id -M --fraction | Count tables for known miRNAs |

| Novel miRNA Prediction | miRDeep2, miRPlant | Minimum read depth = 5, hairpin structure | BED files with novel miRNA coordinates |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, edgeR | Fold change >2, adjusted p-value <0.05 | Lists of differentially expressed miRNAs |

| Target Prediction | TargetScan, miRanda | Context++ score, conservation | Annotated target genes and pathways |

For STAR alignment in this pipeline, after implementing the parameters described in Section 3, it's crucial to validate alignment quality using metrics such as mapping rate, distribution of read lengths in aligned files, and percentage of reads mapping to known miRNA loci. The alignment should be performed against a reference genome with comprehensive annotation of known small RNAs from databases such as miRBase.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Small RNA Sequencing

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Library Prep Kits | SMARTer smRNA-Seq Kit (Takara Bio), QIAseq miRNA Library Kit (Qiagen), CleanTag Small RNA Library Prep Kit (TriLink) | Incorporate optimized adapters and enzymes for efficient small RNA capture; some include UMIs for PCR bias correction [39] [40] |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Agilent RNA 6000 Pico/Nano Kit (Agilent Technologies) | Critical for assessing RIN and ensuring sample quality meets protocol requirements [40] |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | RiboGone - Mammalian Kit (Takara Bio) | Essential for random-primed protocols to remove ribosomal RNA that would otherwise dominate sequencing reads [40] |

| RNA Purification Kits | NucleoSpin RNA XS (Macherey-Nagel) | Designed for low-input samples; avoid kits using poly(A) carriers which interfere with oligo(dT)-primed cDNA synthesis [40] |

| Spike-in Controls | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix (Thermo Fisher) | Synthetic RNA controls of known concentration to monitor technical variation and quantify sensitivity [38] [18] |

| UMI Adapters | QIAseq miRNA Library Kit (12bp UMIs), TrueQuant SmallRNA Seq Kit (GenXPro) | Unique Molecular Identifiers enable accurate quantification by correcting for PCR amplification bias [39] [38] |

The selection of appropriate reagents is critical for successful small RNA sequencing experiments. When choosing a library preparation kit, consider factors such as input RNA requirements, compatibility with your sample type (especially for degraded samples from FFPE tissue), and whether the protocol includes measures to reduce ligation bias, such as randomized adapters [39]. For low-input samples, such as liquid biopsies where miRNA concentration is typically low, select kits specifically validated for these applications [39]. The incorporation of UMIs is particularly recommended for experiments requiring precise quantification, as they enable bioinformatic correction of PCR amplification biases that disproportionately affect the representation of different small RNA species [38].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Can the STAR aligner be used for Oxford Nanopore (ONT) long-read data?

Answer: While technically possible, STAR is generally not recommended for Oxford Nanopore long-read data. Performance is often poor, with a very low percentage of reads mapping successfully. One user reported that only 5.73% of ONT reads were uniquely mapped using STARlong, while the vast majority (89.20%) were unmapped because they were classified as "too short," despite being very long reads [42]. For ONT data, dedicated long-read aligners like minimap2 are the preferred and more efficient choice [42].

FAQ 2: What are the main limitations of short-read RNA-seq that long-read sequencing overcomes?

Answer: Short-read RNA-seq (e.g., Illumina) has limitations that long-read technologies (e.g., PacBio Iso-Seq) directly address, as summarized in the table below [43] [44].

| Feature | Short-Read RNA-Seq | Long-Read Iso-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | ~150-300 bp [44] | ~10-15 kb (HiFi reads) [44] |

| Transcript Coverage | Fragmented [44] | Full-length [44] |

| Isoform Resolution | Indirect, assembly-dependent [44] | Direct, accurate [44] |

| Splice Junction Accuracy | Lower, inference-based [44] | High [44] |

| PolyA & TSS Detection | Indirect [44] | Direct [44] |

| Fusion Gene / SV Detection | Limited [44] | High-resolution [44] |

FAQ 3: My STAR alignment for a custom genome has low mapping rates. What could be wrong?

Answer: Low mapping rates with a custom genome, such as a plasmid, can result from improper index generation. A critical parameter is --genomeSAindexNbases, which must be adjusted for small genomes. The rule of thumb is to calculate this value using the formula min(14, log2(GenomeLength)/2 - 1). For example, when aligning to a plasmid, you may need to reduce this parameter to 5 instead of the default 14 used for a human genome [45].

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Integrated Analysis of PacBio Iso-Seq Data Using the TAGET Toolkit