Optimizing STAR Alignment Parameters for Enhanced Novel Splice Junction Detection in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing the STAR aligner for novel splice junction detection, a critical capability for identifying disease-relevant splicing variants. We cover foundational concepts of spliced alignment, detail step-by-step protocols for two-pass alignment and parameter configuration, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present rigorous validation frameworks. By integrating current methodological insights with practical optimization strategies, this resource empowers scientists to maximize sensitivity and accuracy in splicing analyses, thereby advancing transcriptomic studies in cancer, neurodegeneration, and other splicing-associated diseases.

Optimizing STAR Alignment Parameters for Enhanced Novel Splice Junction Detection in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing the STAR aligner for novel splice junction detection, a critical capability for identifying disease-relevant splicing variants. We cover foundational concepts of spliced alignment, detail step-by-step protocols for two-pass alignment and parameter configuration, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present rigorous validation frameworks. By integrating current methodological insights with practical optimization strategies, this resource empowers scientists to maximize sensitivity and accuracy in splicing analyses, thereby advancing transcriptomic studies in cancer, neurodegeneration, and other splicing-associated diseases.

Understanding Splice Junction Detection: Why Novel Junctions Matter in Disease Research

The Critical Role of Alternative Splicing in Disease Mechanisms and Drug Targeting

Alternative splicing (AS) is a fundamental mechanism enabling a single gene to produce multiple protein isoforms with diverse or even opposing functions, thereby greatly expanding the functional complexity of the proteome [1]. This process is critically regulated by the spliceosome, a molecular complex that acts as 'cellular scissors' to remove introns and join exons in pre-messenger RNA (pre-mRNA), with different exon combinations generating distinct mature mRNAs [1]. When alternative splicing is dysregulated, it can contribute to the pathogenesis of numerous diseases, ranging from rare genetic disorders to common complex diseases, making it a compelling target for therapeutic intervention [2] [1]. This application note explores the mechanisms linking splicing defects to disease, highlights successful drug targeting strategies, and provides detailed protocols for investigating alternative splicing in a research setting, with a specific focus on optimizing STAR aligner parameters for novel splice junction detection.

Alternative Splicing in Disease Pathogenesis

Mechanisms of Splicing Dysregulation

Dysregulation of alternative splicing can occur through multiple mechanisms, each with significant pathological consequences:

- Cis-acting mutations: Genetic variants in splice sites or regulatory elements (e.g., exonic or intronic splicing enhancers/silencers) can disrupt normal splicing patterns. For example, in Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA), incorrect skipping of an exon in the SMN1 gene produces a non-functional protein, leading to motor neuron loss [1].

- Trans-acting factor dysregulation: Altered expression or function of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and core spliceosome components can have widespread effects on splicing networks. For instance, the splicing factor Muscleblind1 depletion causes specific exon skipping in heart tissue, as visualized through Sashimi plots [3].

- Environmental stress-induced splicing changes: Cellular stress responses can directly influence splicing decisions, contributing to disease progression in conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where immune cells under stress produce different isoforms of the BCL gene to control survival and proliferation [1].

Approximately 10-30% of disease-causing variants are estimated to affect splicing, highlighting the broad impact of splicing dysregulation on human health [1].

Disease Associations and Quantitative Evidence

Table 1: Alternative Splicing Associations in Human Diseases

| Disease Category | Specific Disease | Key Gene(s) | Splicing Defect | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rare Genetic Disorder | Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) | SMN1 | Exon skipping | Loss of motor neurons [1] |

| Metabolic Disorder | Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, Dyslipidemias | Multiple (sQTL associated) | Tissue-specific mis-splicing | Metabolic dysregulation [2] |

| Inflammatory Disease | Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | >200 genomic regions | Intronic variant disruption | Altered immune cell regulation [1] |

| Neurological Disease | Epilepsy | SCN1A (sodium channel) | Splicing variation | Altered response to antiepileptic drugs [4] |

Table 2: Splicing Quantitative Trait Loci (sQTL) Impact on Complex Traits

| sQTL Feature | Impact and Prevalence |

|---|---|

| Definition | Genetic loci that influence variation in alternative splicing patterns [2] [4] |

| Association | Strongly associated with cardiometabolic traits and disease risk [2] |

| Detection Method | Robust statistical models like GLiMMPS using RNA-seq data [4] |

| Validation Rate | 100% validation rate for 26 randomly selected sQTLs via RT-PCR [4] |

Therapeutic Targeting of Alternative Splicing

Approved Splicing-Targeted Therapies

The most prominent success in splicing-directed therapeutics is Nusinersen (Spinraza), an FDA-approved antisense oligonucleotide for Spinal Muscular Atrophy that corrects the aberrant skipping of exon 7 in the SMN1 gene, transforming a fatal condition into a manageable disorder [1]. This therapy exemplifies the principle of using antisense oligonucleotides to modulate splicing outcomes by binding to specific pre-mRNA sequences and blocking or promoting the inclusion of specific exons.

Emerging Therapeutic Approaches

- RNA-based medicines: Following the success of mRNA vaccines, RNA-targeted therapeutics are emerging as a promising modality for correcting splicing errors, with several now approved for clinical use [1].

- Small molecule splicing modulators: Compounds that target specific components of the splicing machinery or regulatory complexes offer potential for oral administration and broader application.

- Population-scale splicing maps: Initiatives like the IsoIBD project and Project JAGUAR are building detailed maps of splicing variation in disease-relevant tissues across diverse populations, providing foundations for targeted treatment development [1].

Therapeutic Development Pipeline

Experimental Protocols for Splicing Analysis

RNA Sequencing and Splice Junction Detection

The accurate detection of splice junctions from RNA-seq data presents significant computational challenges, particularly in distinguishing between biologically relevant isoforms and technical artifacts [5]. The STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) aligner uses a novel algorithm based on sequential maximum mappable seed search in uncompressed suffix arrays followed by seed clustering and stitching, enabling precise mapping of reads across splice junctions without prior knowledge of junction locations [6].

Table 3: STAR Aligner Parameter Optimization for Splice Junction Detection

| Parameter | Standard Setting | Optimized for Novel Junctions | Impact on Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment Mode | 1-pass mapping | 2-pass mapping with filtered junctions | Increases novel junction discovery [7] |

| Junction Filtering | None | Remove low-coverage (column 7 < 5) and non-canonical junctions | Improves reproducibility [7] |

| Genome Alignment | Basic genome index | Include comprehensive annotation | Reduces false positives [6] |

| Read Mapping | Default parameters | Increase alignments per read for multimapping | Enhances sensitivity [6] |

Protocol: Two-Pass STAR Alignment with Junction Filtering

Materials Required:

- RNA-seq data in FASTQ format

- Reference genome and annotation (GTF/GFF)

- STAR aligner software

- Computing resources (12-core server recommended for efficiency [6])

Procedure:

- Generate genome index: Create a STAR genome index using the reference genome and annotation file.

- First-pass alignment: Run STAR in first-pass mode to identify novel splice junctions for each sample.

- Junction filtering: Concatenate SJ.out.tab files from all samples and filter junctions with low read support (<5 reads), non-canonical splice sites, and mitochondrial genes.

- Second-pass alignment: Re-run STAR using the filtered junction file from step 3 to improve alignment accuracy and novel junction detection.

- Output analysis: Process the resulting BAM files for downstream splicing quantification using tools like MAJIQ or MISO.

Note: While 2-pass mapping increases detection of splicing changes, it may reduce uniquely mapped reads by 1-2% and increase computational time. For most applications, 1-pass mapping provides more reproducible results, while 2-pass is preferable for hypothesis-generating studies seeking maximal junction discovery [7].

Splicing Quantification and Statistical Analysis

The GLiMMPS (Generalized Linear Mixed Model Prediction of sQTL) method provides a robust statistical framework for detecting splicing quantitative trait loci (sQTLs) from RNA-seq data, explicitly accounting for individual variation in sequencing coverage and overdispersion prevalent in RNA-seq data [4]. Unlike simple linear models, GLiMMPS models the estimation uncertainty of exon inclusion levels (PSI, Percent Spliced In) by using reads from both inclusion and skipping isoforms, significantly improving detection reliability with a demonstrated 100% validation rate for identified sQTLs [4].

RNA-seq Splicing Analysis Workflow

Visualization and Interpretation

Sashimi Plots for Quantitative Splicing Visualization

Sashimi plots provide a quantitative multi-sample visualization of RNA sequencing read alignments, enabling direct comparison of splicing patterns across different conditions or genotypes [3]. These plots display genomic reads as density plots (in RPKM units) and splice junction reads as arcs whose width is proportional to the number of junction reads spanning connected exons, with raw junction read counts annotated on each arc [3].

Protocol: Generating Sashimi Plots with IGV and Command-Line Tools

- Input Requirements: Alignments in BAM format and gene model annotations in GFF3 format.

- IGV-Sashimi Integration: Use the Integrated Genome Browser (IGV) for dynamic, exploratory analysis of genomic regions with on-the-fly Sashimi plot generation.

- Static Sashimi Plots: Use the command-line Python implementation (packaged with MISO) for publication-quality figures with customizable colors, scales, fonts, and sizes.

- Quantitative Integration: Optionally decorate plots with PSI (Ψ) values from MISO estimation to provide quantitative measures of alternative exon inclusion levels.

Long-Read Sequencing for Comprehensive Isoform Characterization

While short-read sequencing (75-150 base pairs) has been the standard for RNA studies, long-read technologies from Pacific Biosciences and Nanopore now enable sequencing of full-length RNA molecules spanning thousands of base pairs, providing unambiguous information about alternative splicing structure without assembly [1]. This is particularly valuable for clinical applications where accurately determining the complete structure of splicing variants is essential for understanding pathogenic mechanisms and developing targeted interventions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Splicing Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Category | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAR Aligner [6] | Computational Tool | Spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads to reference genome | Ultra-fast, detects canonical and non-canonical junctions |

| GLiMMPS [4] | Statistical Model | Detection of splicing quantitative trait loci (sQTLs) | Accounts for read depth variation and overdispersion |

| Sashimi Plots [3] | Visualization | Quantitative visualization of splicing across samples | Junction read arcs and read density profiles |

| Pacific Biosciences [1] | Sequencing Technology | Long-read sequencing for full-length isoform detection | Resolves complex splicing patterns without assembly |

| MISO [3] | Computational Tool | Quantification of alternative splicing from RNA-seq data | Bayesian estimation of isoform abundance (PSI values) |

| MAJIQ [7] | Computational Tool | Detection and quantification of splicing changes | Models local splicing variations (LSVs) and confidence |

| Rosthornin B | Rosthornin B, MF:C24H34O7, MW:434.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 6-O-Cinnamoylcatalpol | 6-O-Cinnamoylcatalpol | High-purity 6-O-Cinnamoylcatalpol for research applications. Explore its potential anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor properties. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Alternative splicing represents a critical layer of genetic regulation with profound implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies. The integration of advanced computational methods like STAR alignment with robust statistical approaches such as GLiMMPS enables comprehensive detection and quantification of splicing variations associated with disease. As long-read sequencing technologies mature and population-scale splicing maps expand, researchers and drug developers are increasingly equipped to identify splicing-specific therapeutic targets and develop innovative RNA-directed medicines that can correct pathogenic splicing defects across a wide spectrum of human diseases.

The accurate detection of novel splice junctions from RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data is crucial for advancing our understanding of transcriptome complexity, particularly in disease research and drug development. However, standard alignment methodologies exhibit inherent biases that favor known junctions, impeding the discovery of unannotated splicing events. Within the context of optimizing STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) alignment parameters, this application note delineates the primary challenges and provides detailed protocols to overcome these technical limitations, enabling more sensitive and accurate novel junction detection.

The Core Challenge: Alignment Biases Against Novel Junctions

Conventional RNA-seq aligners, including STAR, typically use annotated gene references to facilitate the alignment process. This practice creates a systematic bias where alignment algorithms require substantially more evidence to align reads across novel splice junctions compared to known, annotated junctions [8]. The preference for known junctions is often implemented through varied alignment scores or multi-stage alignment processes, which inadvertently reduces sensitivity for discovering novel biological events [8]. This bias directly impacts the detection of clinically significant splice-altering somatic variants, which are crucial for predicting treatment risk and making therapeutic decisions in hematologic malignancies [9].

Solution: Two-Pass Alignment with STAR

The two-pass alignment method effectively separates the discovery of splice junctions from their quantification. In the first pass, junctions are identified with high stringency. These discovered junctions are then used as a custom "annotation" in the second alignment pass, which is performed with lower stringency to permit higher sensitivity for aligning reads to these now-known novel junctions [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

1. First-Pass Alignment for Junction Discovery

Note: The --alignSJoverhangMin 8 parameter sets a high stringency for novel junction discovery in the first pass [8].

2. Genome Re-indexing with Discovered Junctions

3. Second-Pass Alignment for Sensitive Quantification

Note: The --alignSJDBoverhangMin 3 parameter in the second pass allows reads to span splice junctions with fewer nucleotides, significantly increasing sensitivity [8].

Performance Characteristics

The following table summarizes the quantitative improvements observed with two-pass alignment across various RNA-seq datasets:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Two-Pass Alignment Across Diverse RNA-seq Datasets

| Sample Type | Read Length | Junctions Improved | Median Read Depth Ratio | Expected Read Depth Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Adenocarcinoma Tissue | 48 nt | 99% | 1.68× | 1.75× |

| Lung Normal Tissue | 48 nt | 98% | 1.71× | 1.75× |

| Reference RNA (UHRR) | 75 nt | 94-97% | 1.25-1.26× | 1.35× |

| Lung Cancer Cell Lines | 101 nt | 97% | 1.19-1.21× | 1.23× |

| Arabidopsis Samples | 101 nt | 95-97% | 1.12× | 1.12× |

Data adapted from systematic evaluation of two-pass alignment performance [8].

Critical STAR Parameters for Novel Junction Detection

Parameter Optimization Strategy

Optimizing specific STAR parameters is essential for balancing sensitivity and precision in novel junction detection. The following parameters have demonstrated significant impact on performance:

Table 2: Key STAR Alignment Parameters for Optimizing Novel Junction Detection

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Impact on Performance | Biological Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

--alignSJoverhangMin |

8 (1st pass), 3 (2nd pass) | Higher values increase precision; lower values increase sensitivity | Prevents false positives while enabling detection of junctions with short overhangs |

--alignIntronMin |

20 | Reduces false positives from small indels | Matches minimum known intron size in eukaryotes |

--alignIntronMax |

1000000 | Allows discovery of long-range splicing | Accommodates the longest known human introns |

--outFilterType |

BySJout | Reduces false junctions in output | Filters out alignments with spurious splice junctions |

--scoreGenomicLengthLog2scale |

0 | Eliminates intron length bias | Prevents penalization of longer introns during alignment |

Experimental Workflow for Parameter Optimization

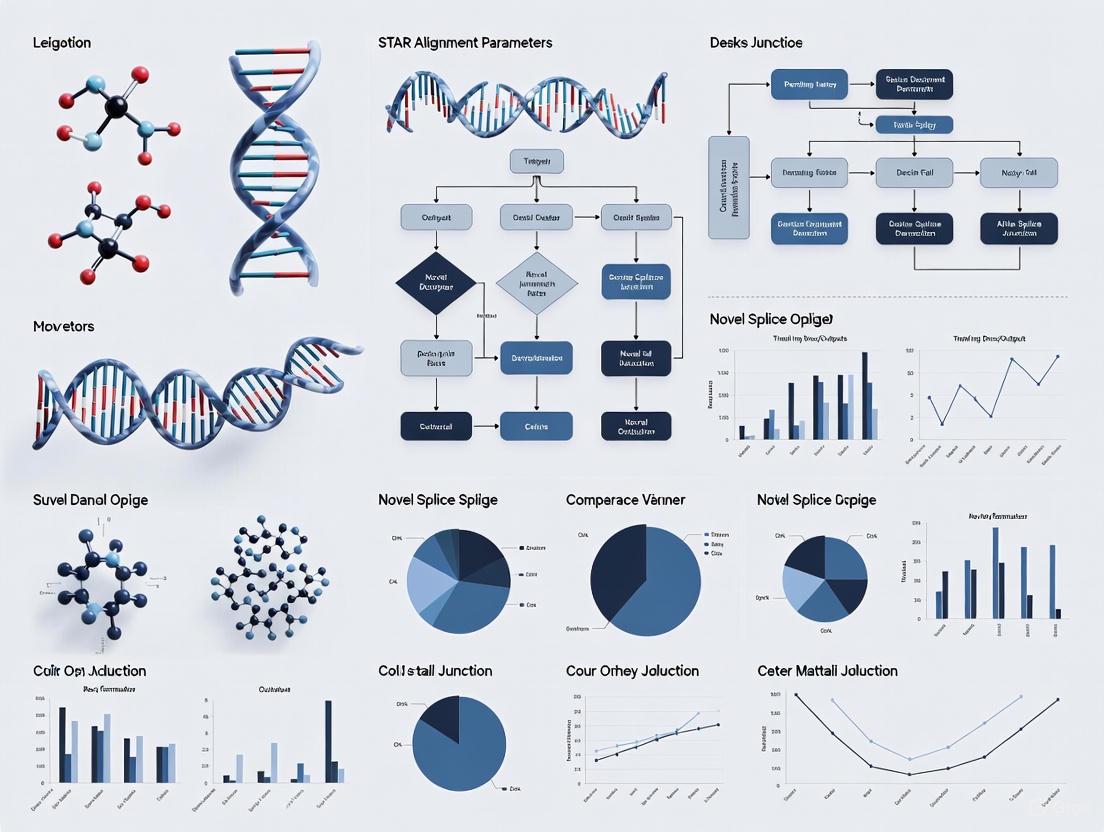

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for optimizing STAR parameters to address alignment biases:

Validation and Quality Control Measures

Addressing Potential Alignment Errors

While two-pass alignment significantly improves sensitivity, it may introduce alignment errors. These potential errors are readily identifiable through simple classification methods and can be filtered using the following criteria:

1. Multi-mapping Read Filtering

- Discard junctions supported predominantly by reads that map to multiple genomic locations

- Require at least 2-3 uniquely mapping reads per novel junction

2. Sequence Motif Validation

- Verify presence of canonical splice motifs (GT-AG, GC-AG, AT-AC)

- Flag non-canonical junctions for additional scrutiny

3. Experimental Validation Protocol For high-priority novel junctions, experimental validation remains the gold standard:

This approach has demonstrated success rates of 80-90% in validating novel intergenic splice junctions [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Splice Junction Studies

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAR Aligner | Software | Spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads | Ultrafast mapping of spliced sequences of any length [6] [10] |

| GENCODE Annotation | Database | Comprehensive gene and transcript annotation | Reference for known splice junctions and gene models [8] |

| Two-pass Alignment | Protocol | Enhanced novel junction quantification | Increases sensitivity for unannotated splicing events [8] |

| ENCODE Guidelines | Framework | Standardized parameter settings | Ensures reproducibility across experiments [8] |

| PolyA Site Databases | Resource | Annotated polyadenylation sites | Context for 3' UTR splicing and alternative polyadenylation [11] |

| 16-Epivoacarpine | 16-Epivoacarpine, MF:C21H24N2O4, MW:368.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Spiramilactone B | Spiramilactone B|Supplier | Spiramilactone B (CAS 180961-65-3) is a diterpenoid for research. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

The implementation of optimized two-pass alignment with carefully tuned STAR parameters effectively mitigates the inherent biases against novel splice junction detection. The detailed protocols provided herein enable researchers to achieve as much as 1.7-fold improvement in read coverage over novel junctions, significantly enhancing the discovery of biologically and clinically relevant splicing events. This approach is particularly valuable in oncology and drug development contexts where splice-altering variants represent important therapeutic targets and biomarkers.

The fundamental challenge of RNA-seq read alignment, compared to genomic DNA alignment, stems from the non-contiguous nature of mature messenger RNA (mRNA) transcripts. In eukaryotic cells, pre-mRNA undergoes splicing where introns are removed and exons are joined together to form the final mRNA molecule. Consequently, reads derived from RNA-seq experiments may span these splice junctions, meaning one portion of the read aligns to one exon while the remaining portion aligns to a non-adjacent exon separated by a potentially large intron in the reference genome. A splice-aware aligner like STAR is specifically designed to handle this biological reality by not attempting to align RNA-seq reads contiguously across introns and instead identifying possible downstream exons to align to, effectively ignoring introns altogether [12].

In contrast, traditional DNA-DNA aligners are considered "splice-unaware." When encountering a read that spans a splice junction, such an aligner would need to introduce a very long gap in the alignment to bridge the intron. This is computationally undesirable and often leads to false mappings, as the aligner might instead find an incorrect, contiguous genomic sequence that partially matches the read [12]. Therefore, while it is possible to align RNA-seq reads to a reference transcriptome using a splice-unaware aligner, aligning to the full genome—which enables the discovery of unannotated genes and novel splice junctions—absolutely requires a splice-aware aligner [12].

The STAR Algorithm: Core Mechanics

STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) employs a unique two-step strategy that sets it apart from traditional aligners and underpins its high speed and accuracy [6] [13].

Seed Searching with Maximal Mappable Prefixes (MMPs)

For each read, STAR performs a sequential search to find the longest subsequence that exactly matches one or more locations on the reference genome [6] [13]. These longest matches are called Maximal Mappable Prefixes (MMPs). The algorithm starts from the beginning of the read, finds the first MMP (designated seed1), then repeats the search for the unmapped portion of the read to find the next MMP (seed2). This process continues until the entire read is processed [13]. This sequential search of only the unmapped portions is a key factor in STAR's efficiency. The MMP search is implemented using uncompressed suffix arrays (SAs), which allow for rapid searching against large reference genomes with logarithmic scaling of search time relative to genome size [6]. If a read contains mismatches or indels that prevent an exact match, the previously identified MMPs are extended to accommodate the differences. If extension fails, poor quality or adapter sequences are soft-clipped [13].

Clustering, Stitching, and Scoring

In the second phase, STAR builds complete alignments by stitching the individual seeds together. The seeds are first clustered based on their proximity to a set of "anchor" seeds, which are seeds that map uniquely to the genome. A dynamic programming algorithm then stitches the seeds within a cluster, allowing for mismatches and a single insertion or deletion (gap). The final alignment is selected based on a scoring model that accounts for mismatches, indels, and gaps [6] [13]. For paired-end reads, STAR clusters and stitches seeds from both mates concurrently, treating the read pair as a single sequence. This approach increases sensitivity, as only one correct anchor from one mate is often sufficient to accurately align the entire read pair [6].

Table 1: Core Algorithmic Differences Between Spliced and Genomic Alignment

| Feature | Splice-Aware Aligner (STAR) | Standard Genomic Aligner |

|---|---|---|

| Handling of Spliced Reads | Aligns segments to separate exons; identifies splice junctions | Attempts contiguous alignment; often fails or misaligns |

| Reference Requirement | Genome (preferred) or transcriptome | Genome or transcriptome |

| Key Innovation | Maximal Mappable Prefix (MMP) search & seed stitching | Full-length or seed-and-extend alignment |

| Gap Handling | Interprets large gaps as introns; uses splice junction penalties | Interprets large gaps as potential indels |

| Output Capabilities | Identifies canonical & novel splice junctions, chimeric transcripts | Identifies genomic variants (SNPs, indels) |

Two-Pass Alignment for Novel Junction Discovery

A critical protocol for enhancing the detection of novel splice junctions is the two-pass alignment method [8] [14]. This strategy is particularly valuable for research aimed at comprehensive splice junction discovery, such as in the context of the user's broader thesis on STAR parameters.

Protocol Rationale and Workflow

In standard single-pass alignment, the aligner uses existing gene annotations to guide the mapping of reads across known splice junctions. While this reduces noise, it also introduces a bias against the alignment of reads that span novel, unannotated junctions, as these require more evidence than known junctions [8]. The two-pass method addresses this by separating the processes of junction discovery and sensitive read quantification [8].

The workflow consists of two sequential alignment steps:

- First Pass: Alignment is performed with high stringency using only the existing genome and annotations. The goal is to generate a high-confidence set of novel splice junctions from the data, which are recorded in the

SJ.out.taboutput file. - Second Pass: The novel junctions discovered in the first pass are provided to STAR as an additional set of "annotations" via the

--sjdbFileoption. The data is then realigned. In this pass, reads can be mapped across these novel junctions with the same lower stringency typically reserved for known junctions, thereby increasing sensitivity and the accuracy of quantification for these novel sites [8] [14].

Performance and Considerations

Two-pass alignment has been demonstrated to significantly improve the quantification of novel splice junctions. Studies show it can improve the median read depth over novel junctions by as much as 1.7-fold, with 94-99% of simulated novel junctions being more accurately quantified compared to single-pass alignment [8].

However, this increased sensitivity comes with trade-offs that must be considered for a research project. It can lead to a 1-2% decrease in the percentage of uniquely mapped reads and a substantial increase in run time, especially with large datasets that generate many novel junction annotations [7]. Furthermore, while two-pass mapping detects more splicing changes, the additional splicing events identified may be less reproducible than those found with single-pass mapping [7]. To mitigate some of these issues, it is recommended to filter the junctions from the first pass before the second pass, removing junctions with low read support (e.g., < 5 reads), non-canonical motifs, and those on the mitochondrial chromosome [7].

Table 2: Two-Pass vs. One-Pass Alignment for Splice Junction Detection

| Characteristic | One-Pass Alignment | Two-Pass Alignment |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Efficient mapping with reference annotation | Maximized discovery of novel splice junctions |

| Sensitivity to Novel Junctions | Lower (biased towards annotated junctions) | Higher (treats novel junctions as known in second pass) |

| Quantification Accuracy | Good for annotated junctions | Improved for novel junctions (up to 1.7x read depth) |

| Computational Load | Faster, less resource-intensive | ~3-5 minutes more per sample; requires more storage |

| Uniquely Mapped Reads | Higher percentage | 0.4% - 2% lower |

| Best Use Case | Standard gene expression quantification, well-annotated organisms | Exploratory research, novel isoform detection, less-studied genomes |

Experimental Protocol for STAR Alignment

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for generating genome indices and performing read alignment with STAR, forming the basis for reproducible RNA-seq analysis [13] [14].

Hardware

- Computer with Unix, Linux, or Mac OS X.

- Substantial RAM: at least 10 x genome size (e.g., ~30 GB for human). 32 GB is recommended for human genomes [14].

- Sufficient disk space (>100 GB) for output files and temporary storage.

- Multiple CPU cores for parallel processing. The number of threads (

--runThreadN) is typically set to the number of physical cores.

Software

- STAR software, available from https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR [14].

Input Files

- Reference genome sequence in FASTA format.

- Gene annotation in GTF format (e.g., from Ensembl or GENCODE).

- RNA-seq reads in FASTQ format (uncompressed or gzipped).

Step-by-Step Procedures

Alternate Protocol 1: Generating Genome Indices Genome indices must be created once for each genome/annotation combination.

Create Directory and Navigate:

Run Genome Generation: Execute the STAR command in

genomeGeneratemode. The--sjdbOverhangshould be set to the maximum read length minus 1 [13].

Basic Protocol: Mapping RNA-seq Reads This is the core mapping procedure, which can be performed as a single-pass or as the first pass of a two-pass strategy.

Create and Navigate to Run Directory:

Execute Alignment Job: The command below is for paired-end reads. For single-end, specify only one file after

--readFilesIn. The--outSAMtypeoption specifies a coordinate-sorted BAM file, which is standard for downstream analysis.

Alternate Protocol 2: Two-Pass Mapping To perform two-pass mapping for novel junction discovery [14]:

- First Pass: Run the Basic Protocol alignment. This generates a file

sample1_SJ.out.tabcontaining discovered junctions. - Second Pass: Run the Basic Protocol again, but add the junctions from the first pass as additional input.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for STAR RNA-seq Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example Source/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | Linear genomic sequence for read alignment; the foundational mapping coordinate system. | FASTA file (e.g., GRCh38 from GENCODE/Ensembl) |

| Gene Annotation | Provides known transcript models and splice junctions to guide the initial alignment. | GTF/GFF3 file (e.g., from GENCODE, Ensembl, or RefSeq) |

| RNA-seq Reads | The experimental data; short sequence fragments derived from fragmented mRNA. | FASTQ files (single- or paired-end, gzipped or uncompressed) |

| Splice Junction Database (e.g., SJ.out.tab) | A list of high-confidence, sample-derived junctions used as custom annotation for the second pass of alignment. | Tab-delimited file generated by a first-pass STAR run |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Environment | Essential for handling the significant memory (~30 GB for human) and multi-core processing requirements of STAR. | Unix/Linux server or cluster with >=32 GB RAM and multiple cores |

| Pseudolaric acid D | Pseudolaric acid D, MF:C20H30O3, MW:318.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Neolinine | Neolinine, MF:C23H37NO6, MW:423.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing the STAR Alignment Algorithm

The following diagram illustrates the core two-step process of the STAR aligner, from seed search to final stitched alignment.

STAR's Two-Phase Spliced Alignment Process

Implementing Two-Pass STAR Alignment: Step-by-Step Protocols and Parameter Configuration

The two-pass alignment workflow is a sophisticated bioinformatic method designed to enhance the detection and quantification of novel splice junctions from RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data. In standard, single-pass alignment, computational tools align reads to a reference genome using existing gene annotations, which inherently biases the process towards known splice junctions and requires substantially more evidence to align reads across novel, unannotated junctions [8]. This presents a significant challenge for research focused on discovering novel splicing events, such as in disease modeling or non-model organism studies.

The two-pass approach elegantly overcomes this limitation by separating the processes of splice junction discovery and read quantification [8]. In the first pass, alignment is performed with high stringency to identify a comprehensive set of splice junctions from the data itself. These newly discovered junctions are then used as a custom annotation to guide a second, more sensitive alignment pass. This method effectively levels the playing field, allowing novel junctions to be penalized similarly to known ones, thereby increasing sensitivity without compromising specificity. Originally developed for short-read technologies, this approach has been successfully adapted for long-read sequencing platforms like Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), where higher error rates can further complicate accurate splice junction detection [15].

Theoretical Foundation and Performance

Rationale and Mechanism

The core rationale behind two-pass alignment is to reduce the alignment penalty bias against novel splice junctions. In a typical single-pass alignment, algorithms like STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) give preference to reads that align across known, annotated splice junctions [8]. This means a read spanning a novel junction must meet a higher burden of proof—often requiring longer and more perfect sequence matches—to be aligned correctly. The two-pass process mitigates this by treating junctions discovered in the first pass as "known" in the second pass.

The performance improvement primarily stems from an increased ability to align reads that have shorter sequence lengths spanning the splice junctions [8]. In practical terms, two-pass alignment has been demonstrated to permit alignment of reads with shorter overhangs at novel splice junctions, which would otherwise be rejected in a conventional single-pass approach. For long-read sequencing data, tools like 2passtools further refine this concept by applying machine-learning-based filters to the junctions discovered in the first pass, removing spurious alignments before the second pass to increase the overall accuracy of intron detection [15].

Quantitative Performance Gains

Empirical studies across diverse RNA-seq datasets have consistently demonstrated the substantial benefits of the two-pass alignment method. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from an evaluation of twelve public RNA-seq samples, showcasing the widespread applicability of the technique.

Table 1: Performance of Two-Pass Alignment Across RNA-Seq Datasets [8]

| Sample | Description | Read Pairs (millions) | Splice Junctions Improved | Median Read Depth Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA-50â€5933_T | Lung Adenocarcinoma Tissue | 48 | 99% | 1.68× |

| TCGA-50â€5933_N | Lung Normal Tissue | 52 | 98% | 1.71× |

| UHRR_rep1 | Reference RNA | 83 | 94% | 1.25× |

| UHRR_rep2 | Reference RNA | 85 | 97% | 1.26× |

| LCS22T | Lung Adenocarcinoma Tissue | 52 | 98% | 1.20× |

| LCS22N | Lung Normal Tissue | 35 | 96% | 1.18× |

| A549 | Lung Cancer Cell Line | 92 | 97% | 1.21× |

| NCI-H1437 | Lung Cancer Cell Line | 76 | 97% | 1.19× |

| AT_flowerbuds | Arabidopsis Flower Buds | 192 | 97% | 1.12× |

| AT_leaves | Arabidopsis Leaves | 202 | 95% | 1.12× |

The data reveals that two-pass alignment improved the quantification accuracy for 94% to 99% of simulated novel splice junctions across all tested samples, including human and Arabidopsis thaliana data [8]. The median read depth over these novel junctions increased by a factor of 1.12× to 1.71×, providing significantly greater power for downstream analysis and validation.

For long-read data, the benefits are similarly pronounced. In a study on Arabidopsis nanopore Direct RNA Sequencing (DRS) data, using reference splice junctions to guide minimap2 alignment (a form of two-pass principle) resulted in 92.1% of simulated reads aligning to the correct transcript isoform for a challenging locus (FLM gene), compared to only 19.3% with standard alignment and 40.3% with post-alignment correction tools like FLAIR [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Two-Pass Alignment with STAR for Short Reads

This protocol is optimized for Illumina short-read RNA-seq data and utilizes the STAR aligner, which is designed for high sensitivity and speed [16] [17].

A. Software and Data Preparation

- STAR Aligner: Ensure STAR (version 2.4.0h1 or later) is installed and available in your

PATH[8] [17]. - Reference Genome: Obtain the reference genome sequence (e.g., GRCh38 for human, TAIR10 for Arabidopsis) in FASTA format [8] [17].

- Annotation File (Optional): For an enhanced first pass, a high-quality annotation file (e.g., GENCODE-Basic for human) in GTF format can be used [8] [17].

- RNA-seq Reads: Provide the sequencing reads in FASTQ format. For paired-end reads, you will have two files per sample [17].

B. Generating the Genome Index

The genome index must be generated once for a given reference genome and annotation combination.

- Create a directory for the genome indices:

mkdir genomeDir - Run the STAR genome generation command:

Note: The

--sjdbOverhangvalue should be set to the read length minus 1 [17].

C. First-Pass Alignment and Junction Discovery

The goal of this step is to map the reads and extract a comprehensive set of splice junctions from your data.

- Run the first alignment pass:

- Upon completion, STAR will generate a splice junction file named

sample1_pass1_SJ.out.tab. This file contains the coordinates and structural information for all splice junctions detected in the first pass.

D. Second-Pass Alignment with Discovered Junctions

In this critical step, the junctions discovered in the first pass are used to create a refined genome index for the final, more sensitive alignment.

- Re-generate the genome index, this time including the novel junctions from the first pass:

Note: Multiple junction files from several samples can be combined at this stage using a space-separated list with the

--sjdbFileparameter for a unified project-level analysis. - Run the second and final alignment pass using the new index:

The final, high-quality alignments will be in

sample1_pass2_Aligned.sortedByCoord.out.bam.

Protocol 2: Two-Pass Alignment for Long Reads using 2passtools

This protocol is designed for long-read technologies (ONT or PacBio) and uses 2passtools, which incorporates machine learning to filter splice junctions, addressing the higher error rates of these platforms [15].

A. Software and Data Preparation

- 2passtools: Install the software suite from https://github.com/bartongroup/2passtools [15].

- Minimap2: Ensure this aligner is available, as it is often used within the workflow [15].

- Reference Genome: Genome sequence in FASTA format.

- Long-read RNA-seq Data: Reads in FASTQ format.

B. Workflow Execution

- Perform First-Pass Alignment: Map the reads to the genome using a long-read aware aligner like minimap2.

- Filter Splice Junctions: Use

2passtoolsto process the first-pass alignments. It applies a combination of alignment metrics and a logistic regression (LR) model to filter out spurious splice junctions, retaining only high-confidence junctions [15]. This step leverages biological sequence signatures (e.g., GU-AG intron motifs) to distinguish genuine junctions. - Perform Second-Pass Alignment: Use the filtered set of high-confidence junctions to guide the realignment of the original reads. This yields a final BAM file with significantly improved accuracy in intron identification and transcript isoform structure [15].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram provides a consolidated overview of the two-pass alignment logic, applicable to both short-read and long-read variations of the workflow.

Two-Pass Alignment Workflow Logic

Table 2: Key Resources for Two-Pass Alignment Experiments

| Item | Function / Relevance | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| STAR Aligner | A fast, sensitive RNA-seq read mapper specifically designed for splice-aware alignment. It is a standard tool for implementing two-pass workflows with short reads [8] [16] [17]. | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR; Version 2.4.0h1 or later [8]. |

| 2passtools | A software package designed for two-pass alignment of long-read RNA-seq data, using machine learning to filter spurious splice junctions [15]. | https://github.com/bartongroup/2passtools |

| Reference Genome | The canonical DNA sequence of the organism under study, serving as the reference for read alignment. | GRCh38 (human), TAIR10 (Arabidopsis) [8]. |

| Annotation File (GTF) | A file containing known gene models and splice junctions. Used for initial indexing or as a benchmark [8] [17]. | GENCODE-Basic (human), Ensembl, or RefSeq. |

| Splice Junction File | A file output by aligners like STAR listing discovered splice junctions. This is the key artifact passed from the first to the second alignment step [8]. | File format: SJ.out.tab |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Alignment, especially with two passes and large genomes, is computationally intensive and requires significant memory and processing power [17]. | Recommended: 32+ GB RAM, multiple CPU cores. |

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Key Parameters and Their Mechanisms

- Experimental Protocols

- Performance and Validation Data

- The Scientist's Toolkit

The discovery of novel splice junctions from RNA-seq data is a fundamental step in understanding transcriptome diversity, with significant implications for basic research and drug discovery. The STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) aligner is a widely used tool for this task, but its performance is highly dependent on the configuration of critical parameters that govern sensitivity and precision. Misconfiguration can lead to either a failure to detect genuine biological events or an overload of false positives, compromising downstream analyses. This application note details the core parameters—--sjdbOverhang, --alignSJoverhangMin, and key filtering strategies—within the context of a broader research thesis on optimizing novel junction detection. We provide structured quantitative data, step-by-step protocols from cited studies, and visual workflows to equip researchers with the knowledge to reliably uncover novel splicing events.

Key Parameters and Their Mechanisms

Proper configuration of STAR parameters is essential to balance the sensitivity of novel junction discovery with the accuracy of alignment. The parameters --sjdbOverhang and --alignSJoverhangMin are particularly crucial, operating at different stages of the alignment process.

--sjdbOverhang: Genome Indexing for Junction Sensitivity

- Function and Workflow Stage: This parameter is used exclusively during the genome indexing step (

--runMode genomeGenerate). It determines how many exonic bases from the donor and acceptor sites are used to construct a database of splice junction sequences that are added to the genome reference [18] [19]. - Mechanism: For each annotated junction, STAR creates a new sequence in the genomic reference by concatenating

Nbases from the end of the upstream exon withNbases from the start of the downstream exon, whereNis the value specified by--sjdbOverhang[19]. This expanded reference allows reads to map across known (and later, discovered) junctions more sensitively. - Setting the Value:

- Ideal Scenario: The manual states the ideal value is

mate_length - 1[18] [19]. For example, for 100 bp paired-end reads, the ideal value is 99. - Practical Guidance: For read lengths below 50 bp, adhering to

read_length - 1is strongly recommended [19]. For longer reads (e.g., 75 bp, 100 bp, 150 bp), using a generic value of 100 is safe, efficient, and recommended by the STAR developer, as it works effectively without needing to re-index for every slight variation in read length [19]. Using a value that is too long is safer than one that is too short [19].

- Ideal Scenario: The manual states the ideal value is

--alignSJoverhangMinvs.--alignSJDBoverhangMin: Alignment-Time Filtering

- Function and Workflow Stage: These parameters are used during the read alignment step to define the minimum number of bases a read must map to each side of a splice junction for the alignment to be accepted.

- Mechanism and Differentiation:

--alignSJDBoverhangMin: This parameter sets the minimum overhang for junctions that are already annotated in the supplied database (sjdb) or discovered in a first pass and used in the second [18]. The default value is 3.--alignSJoverhangMin: This parameter sets the minimum overhang for novel (unannotated) junctions. The default value is 5, reflecting the higher stringency required for non-canonical events [8].

- Impact and Tuning: Lowering these values increases sensitivity, allowing the detection of junctions supported by reads with very short alignments, but at the risk of increasing false positives. Raising them enhances specificity. Research has shown that two-pass alignment improves the quantification of novel junctions by specifically permitting alignments with shorter overhangs that would otherwise be filtered out [8]. For microexons (very small internal exons),

--alignSJDBoverhangMindoes not apply if both flanking junctions are annotated [20].

The following diagram illustrates how these key parameters function at different stages of the STAR workflow for junction discovery.

Experimental Protocols

Here, we detail two foundational experimental protocols cited in the literature for optimizing novel junction discovery with STAR.

Protocol 1: Two-Pass Alignment for Novel Junction Discovery and Quantification

This protocol, adapted from [8] [14], separates the discovery and quantification of splice junctions to increase sensitivity for novel events.

- Principle: Splice junctions are discovered in a first alignment pass with high stringency. These newly discovered junctions are then used as an augmented annotation in a second alignment pass, allowing lower stringency alignment and higher sensitivity for quantification [8].

- Steps:

- First Pass Alignment:

- Run STAR in the default single-pass mode using a standard set of annotations (e.g., GENCODE or Ensembl GTF).

- Critical output: The

SJ.out.tabfile from this pass contains a list of detected junctions, both annotated and novel.

- Junction Filtering (Recommended):

- To prevent an accumulation of false positives in the second pass, filter the

SJ.out.tabfile. Common filters include [7]:- Removing junctions with low read support (e.g., column 7,

read_count < 5). - Keeping only canonical junctions (column 5,

intron_motif = 1) if the study focus is on major splicing events. - Removing junctions on mitochondrial DNA (

chrM).

- Removing junctions with low read support (e.g., column 7,

- To prevent an accumulation of false positives in the second pass, filter the

- Second Pass Alignment:

- Re-run STAR on the same reads, but this time include the filtered

SJ.out.tabfile from the first pass using the--sjdbFileChrStartEndparameter. This directs STAR to treat these junctions as "known" in the second pass. - Alternatively, the

--twopassMode Basicoption can be used to perform these steps automatically, though it offers less control over junction filtering [21] [14].

- Re-run STAR on the same reads, but this time include the filtered

- First Pass Alignment:

- Key Parameters from [8]:

--alignSJoverhangMin 8--alignSJDBoverhangMin 3--seedSearchStartLmax 30(for increased sensitivity with shorter reads)

Protocol 2: Post-Alignment Junction Filtration with Portcullis

This protocol, based on [22], addresses the high false-positive rate of junction callers by using a dedicated filtration tool.

- Principle: Portcullis analyzes the set of mapped split reads supporting each SJ from a STAR BAM file, combining multiple metrics (e.g., read stacking, genome sequence at splice sites) to distinguish genuine from invalid junctions [22].

- Steps:

- Initial Alignment: Run STAR in a standard single-pass mode to generate a BAM file.

- Run Portcullis: Execute Portcullis with the BAM file and the reference genome as input.

portcullis full -t <threads> <reference_genome> <input.bam> <output_prefix>

- Output: Portcullis produces a high-confidence set of junctions in various formats (BED, GTB) suitable for downstream analyses or for use as a filtered junction database in a two-pass STAR workflow.

- Performance: Independent benchmarking shows that Portcullis significantly improves precision over raw STAR output, maintaining F1 scores above 97% across different species and read lengths, even as sequencing depth increases [22].

Performance and Validation Data

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from studies that evaluated the impact of different STAR parameters and workflows on junction discovery.

Table 1: Performance of Two-Pass Alignment on Novel Junction Quantification [8] This study treated known junctions as unannotated to simulate novel junction discovery, comparing one-pass versus two-pass alignment across diverse RNA-seq samples.

| Sample Type | Read Length | Junctions Improved | Median Read Depth Ratio (2-pass / 1-pass) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | 48 nt | 99% | 1.68× |

| Reference RNA (UHRR) | 75 nt | 94% | 1.25× |

| Lung Cell Lines | 101 nt | 97% | 1.21× |

| Arabidopsis Tissues | 101 nt | 95% | 1.12× |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of 1-pass vs. 2-pass Alignment in Splicing Analysis [7] A study using the MAJIQ pipeline to analyze differential splicing in GTEx and ENCODE data revealed trade-offs between discovery and reproducibility.

| Metric | 1-Pass Alignment | 2-Pass Alignment (Unfiltered) | 2-Pass Alignment (Filtered) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Splicing Changes Detected | Baseline | More LSVs found | More LSVs found than 1-pass |

| Uniquely Mapped Reads | Baseline | 1-2% decrease | ~0.4% decrease |

| Run Time | Baseline | 3-5 min/sample increase | 1-2 min/sample increase |

| Reproducibility of Unique LSVs | Higher for 1-pass-only LSVs | Lower for 2-pass-only LSVs | Still lower than 1-pass-only LSVs |

| Recommendation | Preferred for most studies | Useful for hypothesis-generation | Mitigates downsides of unfiltered 2-pass |

Table 3: Effect of Read Length and Depth on Junction Calling Accuracy [22] Simulated data analysis reveals fundamental trends affecting all RNA-seq mappers, including STAR.

| Experimental Condition | Effect on Splice Junction Recall | Effect on Splice Junction Precision |

|---|---|---|

| Increasing Read Length (e.g., 76bp to 101bp) | Improves | Improves |

| Increasing Sequencing Depth | Marginally Improves | Significantly Decreases |

The Scientist's Toolkit

This table lists essential reagents, software, and data resources required for implementing the protocols described in this note.

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| STAR Aligner | Ultra-fast RNA-seq read aligner capable of detecting canonical and non-canonical splice junctions. | GitHub Repository [14] |

| Reference Genome | The genomic sequence for the organism of interest. | GRCh38 for human, GRCm39 for mouse (ENSEMBL, Gencode) |

| Gene Annotation File | A file in GTF or GFF3 format containing known gene models and splice junctions. | Gencode Basic annotations are recommended to exclude poorly supported transcripts [8]. |

| Portcullis | A tool for rapidly and accurately filtering false-positive splice junctions from RNA-seq BAM files. | GitHub Repository [22] |

| Splice Junction Database | A file listing high-confidence splice junctions, used to guide the second pass of alignment. | Typically generated from a first pass of STAR (SJ.out.tab) and optionally filtered. |

| Trim Galore | A wrapper tool for Cutadapt and FastQC that performs automated adapter and quality trimming. | Used for pre-processing in published splicing studies [23]. |

| Gynosaponin I | Gynosaponin I, MF:C42H72O12, MW:769.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Autogramin-2 | Autogramin-2, MF:C21H27N3O4S, MW:417.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The accuracy of differential splicing analysis is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the input alignment files. Preparing BAM files that optimally represent splice junctions requires careful consideration of alignment strategies and parameters, particularly when using the popular STAR aligner. Within a broader research thesis on STAR alignment parameters for novel splice junction detection, this protocol details the steps for generating and refining BAM files to ensure they are properly structured for downstream differential splicing tools such as rMATS, DEXSeq, and Bisbee. We present a standardized workflow, benchmarked performance data, and reagent solutions to facilitate robust splicing analysis in research and drug development contexts.

Alignment Strategy Comparison: One-Pass vs. Two-Pass STAR

The choice between one-pass and two-pass alignment with STAR significantly impacts splice junction detection sensitivity, especially for novel (unannotated) junctions. The following section quantitatively compares these approaches.

Table 1: Performance comparison of one-pass versus two-pass STAR alignment

| Performance Metric | One-Pass Alignment | Two-Pass Alignment | Technical Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel Junction Quantification | Baseline | Up to 1.7-fold median read depth improvement [8] | Uses junctions discovered in Pass 1 as annotations for Pass 2, reducing bias against novel junctions. |

| Sensitivity | Standard | Higher sensitivity for novel and low-coverage junctions [8] | Lower stringency in the second pass allows alignment of reads with shorter overhangs. |

| Computational Load | Lower (Baseline) | Higher (3-5 minutes more per sample) [7] | Requires two sequential alignment steps and generation of a new genome index. |

| Unique Read Mapping Rate | Higher (Baseline) | 0.4% - 2% reduction [7] | Increased number of annotated junctions can lead to more multi-mapping reads. |

| Reproducibility of Splicing Changes | High for core events | Detects more LSVs, but additional events can be less reproducible [7] | Junctions with low support from the first pass may introduce less reliable signals. |

The core principle of two-pass alignment is to enhance sensitivity. In the first pass, splice junctions are discovered de novo with high stringency. These discovered junctions are then used as a custom annotation file during the second alignment pass, allowing the aligner to recognize them with the same sensitivity as pre-defined annotated junctions [8].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision process for choosing and implementing an alignment strategy:

Experimental Protocol for BAM File Preparation

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for generating high-quality BAM files suitable for differential splicing analysis.

Protocol 1: Two-Pass STAR Alignment with Junction Filtering

Primary Objective: To generate a BAM file with enhanced sensitivity for novel splice junctions while controlling for potential false positives.

Materials and Reagents:

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing cluster recommended.

- Software: STAR aligner (v2.4.0h1 or newer), SAMtools.

- Data Input: RNA-seq FASTQ files (paired-end recommended), reference genome (e.g., GRCh38), high-quality gene annotation in GTF format (e.g., GENCODE).

Methodology:

- First Pass Alignment & Junction Discovery:

- Align RNA-seq reads using STAR with standard parameters and high stringency for novel junction detection.

- Key Parameters:

--alignSJoverhangMin 8(require 8 nt overhang for novel junctions),--alignIntronMin 20,--alignMatesGapMax 1000000[8]. - The critical output is the

SJ.out.tabfile, which contains all detected splice junctions.

Filtering Discovered Junctions (Critical Step):

- Concatenate

SJ.out.tabfiles from multiple samples if applicable. - Filter the combined junction list to remove low-quality artifacts. Retain only junctions that are:

- Canonical: Filter out non-canonical splice sites (column 5 != 0 in

SJ.out.tab). - High-Coverage: Remove junctions with low read support (e.g., column 7 < 5) [7].

- Non-Mitochondrial: Exclude mitochondrial junctions (chromosome "chrM") to reduce noise.

- Canonical: Filter out non-canonical splice sites (column 5 != 0 in

- Concatenate

Second Pass Alignment:

- Use the filtered junction list from Step 2 as the

--sjdbFileChrStartEndinput for STAR. - Perform the second alignment pass using the original FASTQ files and the same reference genome. This pass will treat the filtered, discovered junctions as "annotated," significantly improving the mapping rate of reads spanning novel junctions.

- Use the filtered junction list from Step 2 as the

Protocol 2: Splice Junction Validation with Portcullis

Primary Objective: To further refine the BAM file by culling alignments associated with invalid splice junctions, producing a cleaner resource for downstream analysis [24].

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: Portcullis (available via Docker, Singularity, Conda, or source).

- Input: A sorted BAM file and its index (

.bai) from Protocol 1, and a reference genome in FASTA format.

Methodology:

- Install Portcullis: The most straightforward method is via Conda:

conda install portcullis -c bioconda[24]. - Run the Full Portcullis Pipeline: The

fullmode executes all necessary steps in sequence. - Outputs: Portcullis generates a filtered junction file and, optionally, a filtered BAM file (

*.portcullis.bam) where reads supporting invalid junctions have been removed. This refined BAM is ideal for tools that perform their own junction counting.

Downstream Integration with Differential Splicing Tools

Properly prepared BAM files are the starting point for various differential splicing algorithms. The choice of tool depends on the specific biological question and the type of splicing events of interest.

Table 2: Differential splicing tools and their input requirements

| Tool | Statistical Method | Primary Input | Splicing Events Detected | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rMATS-turbo [25] [26] | Replicate Multivariate Analysis | BAM or directly from FASTQ | SE, A5SS, A3SS, MXE, RI | Can be resource-heavy; requires consistent read lengths if using BAM. |

| Bisbee [27] | Beta-Binomial Model | Splice event counts (e.g., from SplAdder) | Annotated and novel events with protein-effect prediction | Focuses on Percent Spliced In (PSI); integrates proteomic validation. |

| DEXSeq [28] | Negative Binomial GLM (DESeq2-based) | HTSeq-count-like exon bin counts | Differential exon usage | Works on "exon bins," providing a gene-level perspective on usage. |

| LeafCutter [27] | Non-parametric | Intron excision counts | Splicing clusters (intron retention) | Detects variation in intron usage without pre-defined event types. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

A curated list of key materials and computational tools required for implementing the protocols described in this application note.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Splicing Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| STAR Aligner [16] | Spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads to a reference genome. | Fast; supports splice-junction and fusion detection; requires a genome index. |

| Portcullis [24] | Filters false positive splice junctions from RNA-seq alignment BAM files. | Improves junction quality for downstream analysis; outputs filtered BAM/junctions. |

| rMATS-turbo [26] | Detects differential alternative splicing from RNA-seq data. | Analyzes five core event types; efficient for large-scale datasets. |

| GENCODE Annotation | A high-quality reference gene annotation. | Provides a comprehensive set of known splice junctions for alignment guidance. |

| SAMtools | A suite of utilities for processing and viewing alignments. | Used for sorting, indexing, and manipulating BAM files; a foundational tool. |

The integration between alignment preparation and downstream splicing analysis is critical for generating biologically meaningful results. The application of a two-pass STAR alignment strategy, followed by rigorous junction filtering with tools like Portcullis, produces BAM files of sufficient quality to empower differential splicing detection tools like rMATS and Bisbee. While two-pass alignment enhances novel junction discovery, researchers must balance sensitivity with reproducibility and computational overhead. The protocols and benchmarks provided here offer a reliable roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to standardize their splicing analysis workflows, thereby increasing the robustness of conclusions drawn in both basic research and clinical applications.

The accurate detection of novel splice junctions from RNA-seq data is a cornerstone of advanced transcriptomics, with significant implications for understanding gene regulation, disease mechanisms, and drug target discovery. This process is technically challenging due to the inherent limitations of alignment algorithms, which must map short sequencing reads to reference genomes while distinguishing canonical splicing events from biological novelties and technical artifacts. The core challenge lies in the algorithmic bias of aligners toward known, annotated junctions, which can suppress the detection of unannotated splicing events [8].

The choice of alignment parameters and strategies directly influences detection sensitivity, specificity, and ultimately, the reproducibility of downstream analyses. This case study examines the implementation of a reproducible pipeline for novel splice junction detection, framed within a broader investigation of Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) parameters. We focus specifically on the empirical comparison of one-pass versus two-pass alignment modes, a critical methodological decision point that significantly impacts novel junction quantification [8] [7].

Key Concepts and Algorithmic Foundations

The STAR Alignment Algorithm

STAR employs a novel strategy for spliced alignments based on sequential maximum mappable seed search in uncompressed suffix arrays followed by seed clustering and stitching. This two-phase approach represents a fundamental departure from earlier algorithms that were extensions of DNA short-read mappers [6].

- Seed Search Phase: The algorithm identifies the Maximal Mappable Prefix (MMP), defined as the longest substring from the read start that matches one or more genomic locations exactly. When a splice junction or misalignment is encountered, the MMP search restarts from the first unmapped base of the read, naturally identifying splice junction boundaries in a single alignment pass without prior knowledge of junction loci [6].

- Clustering and Stitching Phase: All seeds aligned in the first phase are clustered by genomic proximity and stitched together using a dynamic programming algorithm that allows for mismatches and small indels. This principled approach allows STAR to handle non-canonical splices and chimeric transcripts while maintaining exceptional mapping speed [6].

The Two-Pass Alignment Rationale

Standard single-pass alignment gives preference to known splice junctions, which reduces noise but introduces systematic bias against novel junctions by requiring stronger evidence for their detection [8]. Two-pass alignment addresses this limitation through a elegant strategy:

- First Pass: High-stringency alignment is performed to discover splice junctions de novo from the data.

- Second Pass: The junctions discovered in the first pass are supplied as an augmented annotation file, enabling the aligner to apply lower stringency parameters specifically for these newly documented junctions, thereby increasing mapping sensitivity [8].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

- Alignment Software: STAR (version 2.4.0h1 or later) for its speed, sensitivity, and fine-grained parameter control [8].

- Reference Genomes: Use standard references (e.g., GRCh38 for human, TAIR10 for Arabidopsis) to ensure consistency with public data resources [8].

- Gene Annotation: For human studies, the GENCODE-Basic gene annotation set (e.g., v21) provides a comprehensive yet high-quality transcriptome reference excluding poorly supported nominations [8].

- Computing Infrastructure: A modest 12-core server suffices for processing large datasets (e.g., 550 million paired-end reads per hour) [6].

Core Two-Pass Alignment Protocol with Filtering

Step 1: First-Pass Alignment and Junction Discovery

This initial pass generates a SJ.out.tab file containing all discovered splice junctions [7].

Step 2: Junction Filtering

Critical for managing computational burden and reducing false positives, this step processes the SJ.out.tab file by:

- Removing junctions with read count < 5 (column 7) [7]

- Excluding non-canonical junctions (column 5 = 0) [7]

- Filtering out mitochondrial genes (column 1 = "chrM") [7]

Step 3: Second-Pass Alignment

The filtered junction file from Step 2 is supplied via the --sjdbFileChrStartEnd parameter, creating a sample-specific augmented reference for more sensitive alignment [8] [7].

Parameter Optimization for Splice Junction Detection

Beyond the basic workflow, these STAR parameters critically affect junction detection performance:

--alignSJoverhangMin 8: Requires reads span novel splice junctions by at least 8 nucleotides for specificity [8].--alignSJDBoverhangMin 3: Requires reads span known splice junctions by at least 3 nucleotides, balancing sensitivity and error reduction [8].--alignIntronMin 20and--alignIntronMax 1000000: Sets biologically plausible intron size boundaries [8].--scoreGenomicLengthLog2scale 0: Eliminates intron length-based scoring penalties that can bias against long introns [8].

Experimental Validation Protocol

While computational detection is essential, experimental validation remains crucial for confirming novel junctions:

- RT-PCR Amplification: Design primers flanking predicted novel junctions using RNA from the original sample [6].

- Roche 454 Sequencing: Sequence RT-PCR amplicons to validate junction structure at nucleotide resolution [6].

- Validation Rate Assessment: Calculate the percentage of computationally predicted junctions confirmed experimentally. Published validation studies report success rates of 80-90% for novel intergenic junctions detected by STAR [6].

Results and Performance Benchmarking

Quantitative Assessment of Two-Pass Alignment Benefits

Table 1: Performance Improvements with Two-Pass Alignment Across Diverse RNA-seq Datasets

| Sample Type | Description | Read Length | Junctions Improved | Median Read Depth Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | Tumor vs. Normal Tissue | 48 nt | 98-99% | 1.68-1.71× |

| Reference RNA | Universal Human Reference RNA | 75 nt | 94-97% | 1.25-1.26× |

| Lung Cancer Cell Lines | Multiple Cell Lines | 101 nt | 97% | 1.19-1.21× |

| Arabidopsis Tissues | Flower Buds & Leaves | 101 nt | 95-97% | 1.12× |

The data demonstrate that two-pass alignment consistently improves quantification across diverse biological contexts, with the most substantial benefits observed in human tumor samples [8].

Trade-offs Between Detection Power and Reproducibility

Independent analyses comparing one-pass versus two-pass alignment reveal critical operational considerations:

- Detection Sensitivity: Two-pass alignment identifies more splicing changes (LSVs) than one-pass across multiple datasets including GTEx tissues and ENCODE knockdown experiments [7].

- Reproducibility Cost: The additional LSVs detected only by two-pass alignment show lower reproducibility across biological replicates compared to events detected by both methods [7].

- Computational Overhead: Two-pass mapping increases runtime (3-5 minutes per sample) and decreases uniquely mapped reads by 1-2%, effects that amplify in larger studies [7].

Impact on Splicing Quantification Accuracy

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of One-Pass vs. Two-Pass Alignment Outcomes

| Performance Metric | One-Pass Alignment | Two-Pass Alignment |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Detected Splicing Changes | Baseline | Increased |

| Reproducibility of Findings | Higher | Lower for uniquely detected events |

| Computational Requirements | Lower | Higher (time + memory) |

| dPSI Correlation Between Methods | Reference | High (>0.99) for shared events |

| Effect on Novel Junction Quantification | Under-quantification | Improved quantification |

While two-pass alignment improves sensitivity, the dPSI values (change in percent-spliced-in) for most events show minimal differences between methods, with ~99% of changes < 0.025, indicating generally consistent quantification for the majority of splicing events [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Function/Application | Specifications/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| STAR Aligner | Spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads | Version 2.4.0h1+; requires C++ compilation [8] |

| GENCODE Annotation | Reference transcriptome for alignment | Use "Basic" gene set for balanced sensitivity/specificity [8] |

| GRCh38 Reference | Primary alignment genome | Use "full" version without alternate contigs [8] |

| High-Performance Computing | Execution of alignment pipeline | 12+ cores; 32GB+ RAM recommended for mammalian genomes [6] |

| RT-PCR Reagents | Experimental validation of novel junctions | Follow manufacturer's protocols for RNA template [6] |

Workflow Visualization

Two-Pass Novel Junction Detection Pipeline

Decision Framework for Alignment Strategy Selection

The implementation of a reproducible novel junction detection pipeline requires careful consideration of the trade-offs between detection sensitivity and result reliability. While two-pass alignment with STAR demonstrably improves quantification of novel splice junctions—providing as much as 1.7-fold deeper read coverage—this comes with operational costs including reduced reproducibility of uniquely detected events and increased computational requirements [8] [7].

For most focused studies where specific splicing events are of interest, one-pass alignment provides sufficient sensitivity with superior reproducibility and faster computation. For broad, discovery-oriented investigations where comprehensive junction detection is prioritized, two-pass alignment with stringent junction filtering represents the optimal approach, particularly when supplemented with experimental validation [7].

The reproducibility of any novel junction detection pipeline depends critically on comprehensive documentation of parameters, version control for all software components, and transparent reporting of filtering strategies. By implementing the protocols and considerations outlined in this case study, researchers can establish robust, reproducible workflows for splice junction detection that advance our understanding of transcriptome complexity and its implications for disease and drug development.

Solving Common Challenges: Balancing Sensitivity, Specificity, and Computational Efficiency

Large-scale RNA-seq studies, such as those involving thousands of samples, present significant computational challenges. The STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) aligner is a cornerstone for splice junction detection but requires substantial system resources and careful parameter configuration. Genome indexing, in particular, is a memory-intensive process demanding at least 32GB of RAM for optimal performance with large genomes [29]. As dataset scale increases, strategies to manage computational burden—such as optimizing alignment passes and filtering junction data—become critical for efficient and accurate novel splice junction discovery. This document outlines proven strategies to address these challenges.

Optimization Strategies and Comparative Analysis

Selecting appropriate alignment strategies and parameters is fundamental to balancing computational cost with result accuracy. The choice between one-pass and two-pass alignment, along with specific filtering thresholds, directly impacts runtime, mapping rates, and the reliability of downstream splicing analysis.

Table 1: Comparison of STAR Alignment Strategies for Large-Scale Studies

| Strategy | Key Parameters & Actions | Impact on Performance | Impact on Splice Junction Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-Pass Alignment | Single alignment to the reference genome. | Faster (saves 3-5 min/sample) Higher uniquely mapped reads (by 1-2%) [7] | Fewer novel junctions detected; high reproducibility for detected events [7]. |

| Two-Pass Alignment | First pass discovers junctions; second pass uses these as annotations. | Slower Lower uniquely mapped reads [7] | Detects more potential novel junctions, but a subset may be less reproducible [7]. |

| Filtered Two-Pass | Filter SJ.out.tab from first pass: remove low-coverage (e.g., < 5 reads), non-canonical junctions, and mitochondrial junctions [7]. |

Moderate runtime increase (1-2 min/sample) Small drop in unique reads (0.4%) [7] | Increases overlap with one-pass results; reduces spurious junctions while retaining sensitivity [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Filtered Two-Pass Workflow

This protocol is designed for processing dozens to hundreds of RNA-seq samples for novel splice junction discovery, balancing thoroughness with computational efficiency.

1. Resource Provisioning and Genome Indexing

- System Requirements: Ensure access to a 64-bit Linux system with a minimum of 8 CPU cores (16+ ideal) and at least 32GB of RAM [29].

- Genome Index Generation: Generate the STAR genome index using comprehensive reference genome (FASTA) and annotation (GTF) files [29].

2. First-Pass Alignment and Junction Extraction

- Execute the first alignment pass for all samples. This step maps reads and generates a file of detected splice junctions for each sample (

SJ.out.tab).

3. Junction Filtering and Consolidation

- Concatenate all

SJ.out.tabfiles and apply filters to create a high-confidence, sample-specific annotation file for the second pass.

4. Second-Pass Alignment

- Realign all reads using the filtered splice junction file. This informs the aligner of novel junctions, improving mapping accuracy.

Experimental Validation and Data Analysis

The effectiveness of alignment strategies must be validated by examining their impact on downstream splicing analysis, such as the quantification of alternative splicing events.

Table 2: Impact of Alignment Strategy on Splicing Quantification (MAJIQ Analysis)

| Metric | One-Pass vs. Filtered Two-Pass Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall dPSI Correlation | ~99% of splicing events show minimal difference ( | dPSI | < 0.025) [7]. |

| Significant Event Overlap | High concordance for events detected by both methods; strong dPSI correlation [7]. | ||

| Strategy-Specific Events | Each method detects a small subset of significant events unique to it [7]. | ||

| Reproducibility of Unique Events | Events detected only in two-pass mode tend to be less reproducible across independent sample sets compared to one-pass-only events [7]. |

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Reagents for Splice Junction Discovery

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| STAR Aligner | A splice-aware aligner that accurately maps RNA-seq reads to a reference genome, detecting both annotated and novel splice junctions [29]. |

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | The genomic sequence for the target organism, required for building the alignment index [29]. |