Optimizing STAR Genome Indexing for Human RNA-seq: A Complete Guide to Parameters, Troubleshooting, and Best Practices

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on generating and optimizing a STAR genome index for the human genome, a critical first step in RNA-seq analysis. It covers foundational concepts of the STAR aligner's algorithm, a step-by-step methodological workflow for index generation with key parameters, solutions to common memory and performance issues, and guidance on validation and comparative analysis. The content is tailored to empower professionals in biomedical and clinical research to achieve accurate, efficient, and reproducible transcriptomic mapping, directly supporting downstream applications in gene expression quantification and biomarker discovery.

Optimizing STAR Genome Indexing for Human RNA-seq: A Complete Guide to Parameters, Troubleshooting, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on generating and optimizing a STAR genome index for the human genome, a critical first step in RNA-seq analysis. It covers foundational concepts of the STAR aligner's algorithm, a step-by-step methodological workflow for index generation with key parameters, solutions to common memory and performance issues, and guidance on validation and comparative analysis. The content is tailored to empower professionals in biomedical and clinical research to achieve accurate, efficient, and reproducible transcriptomic mapping, directly supporting downstream applications in gene expression quantification and biomarker discovery.

Understanding STAR's Core Algorithm and Why Genome Indexing is Crucial

STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) is a highly efficient RNA-seq aligner specifically designed for mapping high-throughput sequencing reads to a reference genome with exceptional speed and accuracy [1]. It addresses the unique challenges of RNA-seq data mapping, which involves aligning reads that may span splice junctions—gaps in alignment caused by the removal of introns during transcription. Unlike DNA-seq aligners, STAR must perform "splice-aware" alignment to accurately map reads that can be split across exons located far apart in the genome [2].

The algorithm is renowned for its exceptional performance, demonstrating alignment speeds more than 50 times faster than earlier aligners while maintaining high accuracy [2] [3]. This efficiency makes STAR particularly valuable for large-scale transcriptomic studies, such as those found in human genomics research and drug development projects where processing tens or hundreds of terabytes of RNA-sequencing data is common [4].

The STAR Alignment Algorithm: A Two-Step Process

STAR employs a sophisticated two-step strategy that enables both high speed and splice-aware alignment. This process involves first identifying mappable segments of reads and then reconstructing their complete alignment across potential splice junctions.

Step 1: Seed Searching with Maximal Mappable Prefixes (MMPs)

The foundation of STAR's alignment strategy lies in its use of Maximal Mappable Prefixes (MMPs). For each RNA-seq read, STAR searches for the longest sequence that exactly matches one or more locations on the reference genome [2]. This initial longest matching sequence is designated as seed1.

If portions of the read remain unmapped after the first MMP is identified, STAR iteratively continues this process, searching for the next longest exactly matching sequence in the unmapped portions of the read to identify seed2, and so on [2]. This sequential searching of only unmapped read portions significantly enhances algorithmic efficiency compared to methods that process entire reads multiple times.

STAR utilizes an uncompressed suffix array (SA) to enable rapid searching for these MMPs, even against large reference genomes such as the human genome [2]. When exact matches are compromised by sequencing errors or polymorphisms, STAR can extend previous MMPs to accommodate mismatches or indels. For poor quality or adapter sequences at read ends, STAR employs soft clipping to exclude these regions from alignment [5].

Step 2: Clustering, Stitching, and Scoring

After identifying all potential seeds (MMPs) for a read, STAR proceeds to reconstruct the complete alignment through a multi-stage process:

- Clustering: The algorithm clusters seeds based on their proximity to established "anchor" seeds—those with unique, unambiguous genomic positions [2].

- Stitching: Seeds are stitched together to form a complete read alignment, potentially spanning large genomic distances corresponding to introns [2].

- Scoring: Competing alignments are evaluated based on comprehensive scoring that considers mismatches, indels, gaps, and splice junction quality [2].

This two-step process enables STAR to efficiently handle the complex task of spliced alignment while maintaining both speed and accuracy in transcriptomic analyses.

Table 1: Key Components of STAR's Alignment Strategy

| Algorithm Component | Function | Genomic Feature Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Maximal Mappable Prefix (MMP) | Identifies longest exact match between read and genome | Read segmentation across features |

| Suffix Array (SA) | Enables fast genome searching | Large genome size |

| Seed Clustering | Groups alignable segments | Proximity constraints |

| Stitching & Scoring | Reconstructs complete read alignment | Splice junctions, structural variants |

Genome Indexing for Human Genomics

STAR requires a precomputed genome index to achieve its rapid alignment performance. For human genome research, this indexing process involves specific considerations due to the genome's size and complexity.

Reference Genome and Annotation Requirements

Creating a STAR genome index requires two primary input files:

- Reference Genome: A genome sequence in FASTA format (e.g., GRCh38 for human)

- Annotation File: Gene annotations in GTF or GFF format specifying known transcript structures [2] [1]

These files should be obtained from authoritative sources such as ENSEMBL, UCSC, or RefSeq, and must represent compatible versions to ensure accurate splice junction identification [1].

Indexing Procedure and Parameters

The basic command for genome index generation is:

For human genomes, the --sjdbOverhang parameter deserves special attention. This parameter specifies the length of the genomic sequence around annotated splice junctions to be included in the index. The recommended value is read length minus 1 [2]. For contemporary sequencing platforms producing 100bp or 150bp reads, values of 99 or 149 are appropriate.

Table 2: Key Genome Indexing Parameters for Human Research

| Parameter | Recommended Setting for Human Genome | Function |

|---|---|---|

--sjdbOverhang |

99-149 (read length - 1) | Defines junction sequence inclusion |

--genomeChrBinNbits |

15-18 (reduce if needed) | Controls memory usage for large genomes |

--runThreadN |

6-16 | Number of parallel threads |

--genomeSAindexNbases |

14 | Suffix array index base size |

Computational Requirements for Human Genomes

Human genome indexing is computationally intensive, typically requiring:

- RAM: Minimum 32GB, ideally 64GB for comprehensive annotations [6] [7]

- Storage: Approximately 30-40GB for the final index

- Time: Several hours depending on processor speed and parallelization [2]

Failure to allocate sufficient memory often manifests as incomplete index generation, with critical files like Genome, SA, and SAindex missing from the output directory [7].

Experimental Protocol for RNA-seq Alignment

This section provides a detailed workflow for aligning RNA-seq data using STAR, optimized for human genomic research.

Preliminary Setup

Begin by ensuring all software dependencies are available in your environment. Using conda facilitates this process:

Organize your directory structure to separate raw data, indices, and results:

Alignment Execution

With the genome index prepared, perform read alignment with the following command:

Critical Alignment Parameters

--outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate: Outputs alignments in sorted BAM format for downstream analysis--quantMode GeneCounts: Provides read counts per gene for expression analysis--outFilterMismatchNmax: Controls maximum allowed mismatches per read (default: 10)--outFilterMultimapNmax: Limits multi-mapping reads (default: 10) [2]

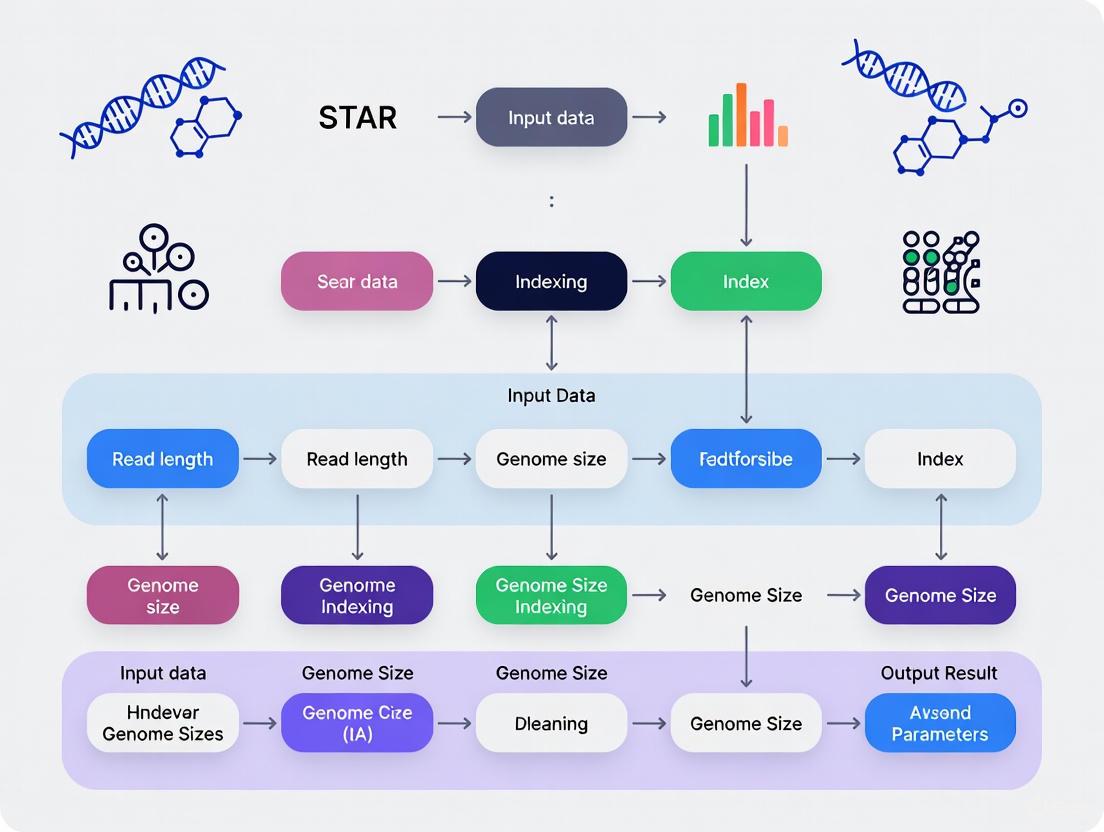

Visualization of the STAR Alignment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete STAR alignment process, from read input to final aligned output:

STAR Alignment Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of STAR alignment requires both computational tools and biological data resources. The following table details essential components for a complete RNA-seq analysis workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | Genomic sequence for alignment | ENSEMBL, UCSC, NCBI |

| Annotation File | Gene models for splice junction guidance | ENSEMBL, GENCODE, RefSeq |

| RNA-seq Reads | Experimental data for analysis | NCBI SRA, ENA, in-house sequencing |

| STAR Software | Alignment algorithm execution | GitHub repository, conda |

| Computing Infrastructure | Hardware for alignment execution | HPC clusters, cloud computing (AWS) |

| SRA Toolkit | Access and conversion of public data | NCBI, conda |

| Metasequoic acid A | Metasequoic acid A, CAS:113626-22-5, MF:C20H30O2, MW:302.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Magnolianin | Magnolianin | Explore Magnolianin, a natural compound for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only and not for human or veterinary diagnostics. |

Advanced Considerations for Human Genomics Research

Addressing Alignment Artifacts

Recent research has identified that splice-aware aligners including STAR can occasionally introduce erroneous spliced alignments between repeated sequences, leading to falsely spliced transcripts [8]. These artifacts particularly affect:

- Genomic Regions with high sequence similarity between flanking regions

- Repetitive Elements such as Alu elements in human genomes

- Experimental Protocols using rRNA-depletion (ribo-minus) which show higher rates of spurious alignments compared to poly(A) selection methods [8]

Tools such as EASTR (Emending Alignments of Spliced Transcript Reads) have been developed to detect and remove these falsely spliced alignments by examining sequence similarity between intron-flanking regions [8].

Cloud-Based Optimization

For large-scale studies, implementing STAR in cloud environments requires special considerations:

- Instance Selection: Memory-optimized instances (e.g., AWS r5 family) provide the best price-to-performance ratio [4]

- Parallelization: Optimal core allocation typically ranges from 6-16 cores per instance [4]

- Early Stopping: Implementing this optimization can reduce total alignment time by up to 23% [4]

STAR's alignment strategy, based on Maximal Mappable Prefixes and sophisticated seed clustering, provides an efficient and accurate solution for the complex challenge of RNA-seq read alignment. The two-step process of seed searching followed by clustering and stitching enables comprehensive detection of both known and novel splice junctions—a critical capability for transcriptomic studies in human health and disease.

Proper implementation requires careful attention to genome indexing parameters, computational resource allocation, and understanding of potential algorithmic limitations. When configured appropriately for human genome research, STAR delivers the performance and reliability required for both small-scale investigations and large-scale transcriptomic atlases, forming a foundation for robust gene expression analysis in basic research and drug development contexts.

The accuracy of any RNA-seq experiment is fundamentally dependent on the initial choice of a reference genome and its corresponding annotation. For human studies, researchers are faced with a decision between several major providers: GENCODE, Ensembl, and UCSC. While these institutions often use the same underlying genome assembly from the Genome Reference Consortium (e.g., GRCh38), they differ significantly in their annotation methodologies, coordinate systems, and transcript models [9] [10]. Selecting mismatched components—such as a UCSC genome fasta file with a GENCODE annotation file—without proper adjustments is a common pitfall that can introduce substantial errors in alignment and quantification [9]. This application note provides a structured framework for making these critical choices within the context of STAR genome indexing for human research, ensuring reproducible and biologically accurate results.

Decoding the Genome Annotation Landscape

Understanding the provenance and key differences between the major annotation sources is the first step in making an informed selection.

GENCODE, Ensembl, and UCSC: Origins and Relationships

The GENCODE annotation is the product of merging manually curated gene annotations from the Ensembl-Havana team with automated annotations from the Ensembl-genebuild pipeline. It serves as the default annotation displayed in the Ensembl browser. For practical purposes, the GENCODE annotation is essentially identical to the Ensembl annotation, though the GENCODE GTF file often includes additional attributes such as annotation remarks, APPRIS tags, and tags for experimentally validated transcripts [11].

Ensembl generates its annotations through an automated pipeline, supplemented by manual curation. A key historical difference was the handling of genes in the pseudoautosomal regions (PARs) of chromosomes X and Y. While Ensembl previously included only the chromosome X copy, GENCODE included identical annotation for both chromosomes, requiring unique identifiers [10] [11]. As of Ensembl release 110 (GENCODE release 44), this has been resolved, and both now provide distinct annotations for the PAR genes on both chromosomes [10].

The UCSC genome browser provides its own genome sequences and a variety of gene annotation tracks. Some, like the "UCSC Genes" track (now discontinued for hg38), were built with a UCSC-developed gene predictor [10]. For the hg38 genome, UCSC also imports and displays annotations from other groups, such as the GENCODE track, which provides the same gene models as the canonical GENCODE release [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Genome Annotation Sources for Human (hg38/GRCh38)

| Feature | GENCODE | Ensembl | UCSC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | High-quality, comprehensive annotation | Automated pipeline with manual curation | Genome browser & gene models |

| Curation Level | Manual + Automated | Manual + Automated | Varies by track (e.g., displays GENCODE, RefSeq) |

| Chromosome Naming | chr1, chrX, chrM [12] |

1, X, MT [12] |

chr1, chrX, chrM [12] |

| Relationship | Identical to Ensembl annotation [11] | Identical to GENCODE annotation [11] | Provides GENCODE and RefSeq tracks [10] |

| Key Differentiator | Rich attributes (tags, support levels) [13] | Integrated with Ensembl tools and resources | Historical gene builds; visualization platform |

The Critical Distinction: Genome Assembly vs. Gene Annotation

A common point of confusion is conflating the genome assembly with its gene annotation.

- The Genome Assembly (e.g., GRCh38.p14) is the actual DNA sequence, provided as a FASTA file. The GRCh38 and hg38 assemblies are functionally equivalent, both originating from the Genome Reference Consortium [9].

- The Gene Annotation defines the coordinates and metadata of genomic features (genes, transcripts, exons, etc.) and is provided as a GTF or GFF file. The differences in coordinates for a gene like Mecp2 between UCSC and Ensembl are due to divergent annotation methodologies, not different underlying DNA sequences [9].

Therefore, the version of the annotation file must precisely match the version of the genome FASTA file it was built upon. Using an annotation based on a different patch version of the genome assembly (e.g., GRCh38.p13 vs. GRCh38.p14) can lead to incorrect mapping of features [9].

A Structured Workflow for Selection and Alignment

The following diagram and protocol outline the critical decision points and steps for generating a STAR genome index, ensuring all components are compatible.

Diagram 1: A decision and workflow for selecting and preparing reference genome and annotation files for STAR indexing. The central principle is ensuring chromosome name consistency between the FASTA and GTF files.

Recommended Protocol: STAR Genome Index Generation with GENCODE

This protocol details the generation of a STAR genome index using human GENCODE data, which is the recommended source for human and mouse studies due to its high quality and consistency [12].

Step 1: Download Reference Files

- Download the primary genome assembly FASTA file from the GENCODE website (e.g.,

GRCh38.primary_assembly.genome.fa.gz). This file contains the sequence of the primary chromosomes and unlocalized/unplaced scaffolds, excluding alternate haplotypes [12]. - Download the comprehensive annotation GTF file from the same GENCODE release (e.g.,

gencode.v45.annotation.gtf.gz). Using files from the same release ensures version compatibility.

Step 2: Prepare the Files

- Decompress the downloaded files.

- Confirm that the chromosome names in the FASTA file use the

chrprefix (e.g.,chr1,chrX) by checking the header lines. GENCODE FASTA files follow this convention [12] [13].

Step 3: Execute the STAR Genome Generate Command

- Load the STAR module or ensure the STAR binary is in your

$PATH. - Run the following command, adjusting paths and the

--sjdbOverhangparameter as needed.

Protocol Notes:

--runThreadN: Specifies the number of CPU threads to use. For the human genome, allocate as many as available (e.g., 16).--genomeDir: The directory where the genome indices will be written. This directory must be created before running the command (mkdir /path/to/output_genome_index).--sjdbOverhang: This critical parameter should be set toReadLength - 1. For example, for 100-base paired-end reads, this value is 99 [2] [12]. For reads of variable length, usemax(ReadLength) - 1.- Memory Requirements: Indexing the human genome is memory-intensive. It is recommended to have at least 32 GB of RAM [6].

Successful genome indexing and alignment require a specific set of bioinformatics "reagents." The following table details these essential components.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for STAR Alignment

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | The canonical DNA sequence against which RNA-seq reads are aligned. | GENCODE "Genome sequence, primary assembly" [12] |

| Gene Annotation (GTF) | Provides coordinates of genomic features (genes, exons, etc.) for guided alignment and quantification. | GENCODE "comprehensive annotation" GTF [13] |

| STAR Aligner | Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference; a splice-aware aligner for RNA-seq data. | https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR [6] |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | A server with substantial memory and multiple CPUs to handle the computational load of indexing and alignment. | 16+ cores, 32+ GB RAM node [2] [6] |

| Sequence Read Files | The raw data output from the sequencer, typically in FASTQ format. | Illumina, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore reads |

| sjdbOverhang Parameter | Defines the length of sequence around annotated junctions used in constructing the splice junction database. | Set to ReadLength - 1 (e.g., 99 for 100bp reads) [2] [12] |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Coordinate Mismatches: If STAR fails or produces empty alignments, the most likely cause is a mismatch between the chromosome names in the FASTA and GTF files. Use commands like

grep "^>" genome.fa | headandcut -f1 annotation.gtf | sort | uniq | headto inspect the naming conventions and use scripts to add or remove thechrprefix as needed [9] [12]. - Memory Errors During Indexing: Indexing the full human genome requires significant RAM (typically >30GB). If the job fails, request more memory from your HPC cluster or use a genome file that excludes alternate haplotypes (e.g., the "primary assembly" only) [6].

- Low Alignment Rates: Ensure the

--sjdbOverhangparameter is correctly set for your read length. An incorrect value can lead to poor alignment at splice junctions [2].

By meticulously selecting compatible reference files and following the detailed protocols outlined in this document, researchers can establish a robust foundation for their RNA-seq analyses, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of all downstream results.

The accurate and efficient analysis of the human genome is a cornerstone of modern biomedical research, enabling advancements in personalized medicine, drug discovery, and our fundamental understanding of human biology. As genomic datasets grow exponentially—with global genomic data projected to reach 40 exabytes by 2025 [14]—the strategic allocation of computational resources has become increasingly critical. The process of genome indexing, which involves creating a searchable reference for aligning sequencing reads, represents one of the most computationally intensive steps in many analysis pipelines. This application note provides a detailed assessment of memory (RAM) and computational requirements for human genome analysis, with particular focus on optimizing STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) genome indexing parameters. We frame these technical specifications within the broader context of sustainable research practices and evolving data security requirements that affect researchers and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Resource Requirements for Human Genome Analysis

Memory (RAM) Requirements for Genome Indexing

Genome indexing represents one of the most memory-intensive processes in bioinformatics workflows. The specific requirements vary significantly depending on the reference genome assembly used and the parameters configured in analysis tools like STAR.

Table 1: Memory Requirements for STAR Genome Indexing with Different Human Reference Assemblies

| Reference Assembly Type | Minimum RAM | Recommended RAM | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Assembly | 16 GB | 32 GB | Suitable for most standard analyses; requires 30-35 GB with 20 threads [15] |

| Toplevel Assembly | 168 GB+ | 200 GB+ | Includes chromosomes, unplaced scaffolds, and haplotype/patch regions; substantially more memory-intensive [15] |

For the STAR aligner specifically, the developer recommends a minimum of 16 GB of RAM for mammalian genomes, with 32 GB being ideal [16]. However, these requirements can be dramatically influenced by the specific reference genome used. Attempting to index the comprehensive "toplevel" assembly (approximately 60 GB in size) can require more than 168 GB of RAM [15], whereas the "primary assembly" file can typically be indexed with 30-35 GB of RAM when using multiple threads [15].

Storage and Computational Scaling for Population Studies

The storage footprint of genomic data continues to expand with the growth of population-scale sequencing initiatives. By 2025, an estimated 40 exabytes of storage capacity will be required for human genomic data [14]. The All of Us research program, which has enrolled over 860,000 participants, provides a striking illustration of this scale: just the short-read DNA sequences would require "a DVD stack three times taller than Mount Everest" to store physically [17].

Computational requirements for analyzing these massive datasets have similarly escalated. In one exome-wide association analysis of 19.4 million variants for body mass index in 125,077 individuals from the All of Us project, the initial runtime was 695.35 minutes (11.5 hours) on a single machine [18]. Through algorithmic optimizations integrated into PLINK 2.0, this was reduced to just 1.57 minutes with 30 GB of memory and 50 threads, demonstrating how software improvements can dramatically enhance computational efficiency [18].

Experimental Protocols for Resource-Efficient Genome Analysis

Protocol: STAR Genome Indexing with Optimized Memory Parameters

Principle: Generate a genome index for RNA-seq read alignment while managing memory utilization based on available computational resources.

Materials:

- Human reference genome (FASTA format)

- Annotation file (GTF format)

- STAR aligner software (version 2.7.9a or newer)

- Computational resources meeting specifications in Table 1

Procedure:

- Genome Selection: Download the appropriate reference genome based on analytical needs and available resources. For most applications, the primary assembly (e.g.,

Homo_sapiens.GRCh38.dna.primary_assembly.fa.gz) is sufficient and requires significantly less memory than the toplevel assembly [15].

Basic Indexing Command:

Memory-Optimized Parameters for Limited RAM (16 GB): When working with constrained memory resources, employ the following parameters recommended by the STAR developer [16]:

Verification: Monitor the process for successful completion without

std::bad_allocerrors, which indicate insufficient memory [15].

Protocol: Benchmarking Assembly and Analysis Pipelines

Principle: Evaluate the performance and accuracy of different analytical workflows using standardized metrics.

Materials:

- Reference samples (e.g., HG002 human reference material)

- Sequencing data (Oxford Nanopore Technologies and Illumina)

- Evaluation tools (QUAST, BUSCO, Merqury)

- Computational benchmarking environment

Procedure:

- Pipeline Comparison: Test multiple assembly tools, including both long-read only assemblers (e.g., Flye) and hybrid assemblers, combined with various polishing schemes [19].

Quality Assessment: Evaluate outputs using multiple complementary metrics:

- QUAST: Assess assembly continuity and completeness

- BUSCO: Evaluate gene content completeness

- Merqury: Measure assembly accuracy

Computational Cost Analysis: Document runtime, memory usage, and storage requirements for each pipeline.

Validation: Apply the best-performing pipeline to non-reference human and non-human routine laboratory samples to verify robustness [19].

Regulatory and Sustainability Considerations

Data Security Requirements

Effective January 25, 2025, researchers accessing genomic data from NIH repositories must comply with new data management and storage requirements per updated "NIH Security Best Practices for Users of Controlled-Access Data" [20]. These requirements include:

Institutional Attestation: Approved users must attest that institutional systems used to access or store controlled-access data comply with NIST SP 800-171 security requirements [20] [21].

Third-Party Providers: Researchers using third-party IT systems or Cloud Service Providers must provide attestation affirming the third-party system's compliance with NIST SP 800-171 [20].

Covered Repositories: These requirements apply to data from dbGaP, AnVIL, BioData Catalyst, NCI Genomic Data Commons, and other listed repositories [21].

Sustainable Computational Practices

The environmental impact of genomic computation has become an increasing concern, with algorithmic efficiency representing a key strategy for reducing carbon emissions. The Centre for Genomics Research at AstraZeneca has demonstrated that advanced algorithmic development can reduce "both compute time and CO2 emissions several-hundred-fold—more than 99%—compared to current industry standards" [17].

Tools like the Green Algorithms calculator enable researchers to model the carbon emissions of computational tasks by incorporating parameters such as runtime, memory usage, processor type, and computation location [17]. This allows for more environmentally conscious experimental planning and algorithm design.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Analysis

| Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| STAR Aligner | Spliced transcriptional alignment | RNA-seq read mapping against reference genomes [16] [15] |

| PLINK 2.0 | Whole genome association analysis | Population-scale genomic studies with optimized efficiency [18] |

| Genomic Benchmarks | Standardized datasets for model evaluation | Training and validation of deep learning models in genomics [22] |

| DNALONGBENCH | Benchmark suite for long-range DNA prediction | Evaluating models on tasks with dependencies up to 1 million base pairs [23] |

| Green Algorithms Calculator | Modeling computational carbon emissions | Sustainable research planning and environmental impact assessment [17] |

| Secure Research Enclaves | NIST 800-171 compliant computing environments | Managing controlled-access genomic data per NIH requirements [21] |

Workflow and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and workflow for determining appropriate computational resources for human genome analysis:

Strategic assessment of memory and computational requirements is fundamental to successful human genome analysis. The STAR aligner typically requires 16-32 GB of RAM for standard human reference genomes, though this can exceed 168 GB for comprehensive toplevel assemblies. Researchers must balance these technical requirements with emerging considerations including NIH data security mandates requiring NIST SP 800-171 compliant environments for controlled-access data, and sustainability concerns that can be addressed through algorithmic efficiency improvements. By implementing the protocols and optimization strategies outlined in this application note, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure both computationally efficient and scientifically rigorous genomic analyses while complying with evolving regulatory frameworks.

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Building Your Human Genome Index

In the context of human genome research, the genomeGenerate command of the Spliced Transcript Alignment to a Reference (STAR) software is a foundational preliminary step for all subsequent RNA-seq data analysis. STAR performs ultra-fast alignment of high-throughput sequencing reads by utilizing a uncompressed suffix array-based genome index to identify seed matches efficiently [24]. This index is generated offline once for each genome/annotation combination and is then reused for all mapping jobs. For research and drug development professionals, constructing a robust and accurate genome index is paramount for ensuring the reliability of downstream analyses, including novel isoform discovery, chimeric RNA detection, and gene expression quantification [24]. This protocol details the essential parameters and methodologies for executing the core genomeGenerate command, with a specific focus on the requirements for large genomes such as human.

Essential Parameters for thegenomeGenerateCommand

The genomeGenerate run mode requires the specification of several critical parameters that define the genome sequence, annotations, and structural properties of the index. A thorough understanding of these parameters is necessary to optimize performance and accuracy.

Critical Input Parameters

The following parameters are mandatory for generating a functional genome index.

| Parameter | Description | Example Value for Human |

|---|---|---|

--genomeDir |

Path to the directory where the genome index will be stored. | /path/to/STAR_Index/ |

--genomeFastaFiles |

One or more FASTA files containing the reference genome sequences. | GRCh38.primary_assembly.genome.fa |

--sjdbGTFfile |

GTF file with transcript annotations. | Homo_sapiens.GRCh38.109.gtf |

--sjdbOverhang |

Length of the genomic sequence around annotated junctions used for constructing the splice junction database. | 100 |

--runThreadN |

Number of threads (CPU cores) to use for the indexing process. | 12 |

System Requirements and Optional Parameters

Successful index generation, particularly for large mammalian genomes, is contingent upon adequate computational resources and potentially beneficial optional parameters.

| Category | Parameter / Specification | Notes and Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| System Requirements | RAM | At least 10 x GenomeSize in bytes. For the human genome (~3 Gb), 32 GB is recommended [24]. |

| Disk Space | Sufficient free space (>100 GB) for storing the final index and intermediary files [24]. | |

| Operating System | Unix, Linux, or Mac OS X [24]. | |

| Optional Parameters | --genomeSAindexNbases |

For small genomes (e.g., yeast), this may need to be reduced. For human, the default is typically sufficient. |

--genomeChrBinNbits |

Can be adjusted for genomes with a large number of small chromosomes/scaffolds. |

Detailed Protocol for Generating a Human Genome Index

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for generating a STAR genome index suitable for human RNA-seq data analysis.

Pre-Indexing Preparation: Resource Acquisition

- Obtain Reference Genome Sequences: Download the primary assembly of the human reference genome in FASTA format from a source such as the Genome Reference Consortium or Ensembl. Avoid including alternative haplotypes or patches in the primary index, as this can drastically increase memory requirements.

- Obtain Gene Annotations: Download a comprehensive GTF file from a database such as Ensembl, GENCODE, or RefSeq. Ensure the annotation file corresponds to the same genome assembly version as your FASTA files (e.g., both GRCh38).

- Verify Computational Resources: Confirm that the server or computational node has at least 32 GB of available RAM and over 100 GB of free disk space. The process is CPU-intensive, so a multi-core system is strongly recommended.

Protocol Execution: Index Generation

The following commands demonstrate the process of generating a genome index for the human genome.

Critical Steps and Notes:

--sjdbOverhang: This parameter is critical for accurate mapping of RNA-seq reads across splice junctions. The value should be set to the maximum read length minus 1. For example, with common 101-base paired-end reads, the optimal value is100[24].- Runtime: The indexing process for a human genome can take several hours, depending on the system's performance. Progress messages will be output to the terminal.

- Troubleshooting: If the job fails with an out-of-memory error, verify that the system has sufficient RAM. For genomes with a very large number of scaffolds, adjusting

--genomeChrBinNbitsmight be necessary.

The following table details the key materials and computational resources required for generating and utilizing a STAR genome index in a research setting.

| Item | Function / Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | Provides the DNA sequence to which RNA-seq reads will be aligned. | Use a primary assembly without alternative haplotypes (e.g., GRCh38 primary assembly). |

| Gene Annotation (GTF) | Informs STAR of known gene models and splice junctions, dramatically improving mapping accuracy. | Use a comprehensive source (e.g., GENCODE, Ensembl) matching the genome assembly version. |

| High-Memory Server | Host for the computationally intensive genome indexing and subsequent alignment steps. | Minimum 32 GB RAM for human genomes; multiple CPU cores significantly speed up the process [24]. |

| STAR Software | The alignment software used for both generating the genome index and performing the read mapping. | Obtain the latest release from the official GitHub repository for production use [6] [24]. |

| Pre-built Genome Indices | Alternative to local index generation; can save significant time and computational effort. | Available for common model organisms; verify the exact genome and annotation versions match your needs [24]. |

Within the framework of a broader thesis on optimizing STAR aligner for human genome research, a deep understanding of key genome indexing parameters is paramount. The accuracy and efficiency of RNA-seq data analysis, a cornerstone in modern genomics and drug development, hinge on the correct configuration of these parameters. This application note provides a detailed examination of three critical parameters—--sjdbOverhang, --runThreadN, and --genomeDir—outlining their theoretical basis, optimal configuration for human genomes, and integration into robust experimental protocols.

The following parameters are used during the genome generation step (--runMode genomeGenerate) to create a custom reference index, which is subsequently used during the read alignment step.

Table 1: Critical STAR Genome Indexing Parameters for Human Genome Research

| Parameter | Function & Role in Genome Indexing | Ideal Value for Human Genome | Impact of Suboptimal Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

--sjdbOverhang |

Defines the length of genomic sequence on each side of annotated splice junctions to be included in the genome index. [25] | 99 for 100bp reads; 149 for 150bp reads; 100 (default) is safe for longer or variable-length reads. [26] [2] |

Too short: Loss of sensitivity for junction read mapping. [26]Too long: Marginally slower mapping speed; generally safer. [26] |

--runThreadN |

Specifies the number of CPU threads for parallelization during genome generation and alignment. | A value close to, but not exceeding, the number of available CPU cores. [27] | Too high: Can overload the system, leading to swapping and severe performance degradation. [27]Too low: Unnecessarily long run times. |

--genomeDir |

Provides the path to a directory where the genome index will be, or has been, generated and stored. | A directory with sufficient write permissions and ample disk space (~30-35GB for human). | Incorrect path: Failure of both genome generation and alignment steps. |

Experimental Protocol for Genome Indexing

This protocol details the steps for generating a STAR genome index for human RNA-seq data, incorporating the critical parameters defined above.

I. Prerequisite Data and Resource Allocation

- Reference Genome: Download the primary assembly FASTA file for the human genome (e.g., GRCh38) from Ensembl or GENCODE.

- Gene Annotation: Obtain the corresponding comprehensive gene annotation file (GTF format) from the same source.

- Computational Resources:

- Memory (RAM): Allocate at least 32 GB; 64 GB is recommended for default parameters to prevent swapping. [27]

- Storage: Ensure the

--genomeDirlocation has at least 35 GB of free space. - CPU Cores: Identify the number of available physical cores to inform the

--runThreadNsetting.

II. Genome Generation Command

The following command exemplifies the genome indexing process. Replace the paths in --genomeDir, --genomeFastaFiles, and --sjdbGTFfile with those specific to your system and data.

III. Validation and Troubleshooting

- Successful Completion: The command will output several index files (e.g.,

Genome,SAindex) into the specified--genomeDir. - Common Failure Modes:

- Process is slow or hangs: This is almost always due to insufficient RAM, causing the system to use slow disk-based swap memory. [27] Verify available memory and reduce

--runThreadNif it exceeds available cores. - "Could not open genome file" error during alignment: This indicates an incorrect or inaccessible path provided to

--genomeDirin the alignment command.

- Process is slow or hangs: This is almost always due to insufficient RAM, causing the system to use slow disk-based swap memory. [27] Verify available memory and reduce

Workflow Visualization and Logical Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the role of the critical parameters within the broader context of the RNA-seq analysis workflow, from data preparation to final alignment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Featured Experiment

| Item | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| STAR Aligner Software [6] | The core C++ software package required for performing both genome indexing and read alignment. |

| Human Reference Genome (FASTA) | The canonical DNA sequence of the human genome against which RNA-seq reads are aligned. |

| Gene Annotation (GTF) | File containing coordinates of known genes, transcripts, and exon-intron junctions, used by --sjdbGTFfile to create the splice junction database. [2] |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Server | A computer with substantial RAM (>32GB) and multiple CPU cores, as the human genome indexing process is computationally intensive. [27] |

| RNA-seq Reads (FASTQ) | The raw sequencing data from the experiment, which will be aligned against the generated genome index. |

| Cabralealactone | Cabralealactone, CAS:19865-87-3, MF:C27H42O3, MW:414.6 g/mol |

| JTE-952 | JTE-952, MF:C30H34N2O6, MW:518.6 g/mol |

Within the context of a broader thesis on optimizing STAR genome indexing for human genome research, managing the substantial computational resources required remains a significant challenge for researchers and bioinformaticians. The process of generating a genome index, a critical first step in RNA-seq analysis, frequently demands memory resources that exceed typical laboratory computing allocations, particularly for large genomes like human. This application note addresses this hardware barrier by detailing the function and application of two advanced parameters, --genomeChrBinNbits and --genomeSAsparseD. These parameters enable researchers to strategically balance memory usage against mapping speed and sensitivity, thereby making large-scale genomic analyses feasible in standard research environments. The guidance herein is particularly relevant for scientists in drug development who require robust, reproducible RNA-seq workflows for analyzing patient-derived data without access to high-performance computing infrastructure.

Parameter Definition and Function

--genomeChrBinNbits: Managing Genome Storage Bins

The --genomeChrBinNbits parameter controls the memory allocated for storing genome sequences in bins during the indexing process. It is defined as log2(chrBin), where chrBin represents the size of the bins into which each chromosome or scaffold is divided [28] [29]. The default value is 18 [28] [29].

For genomes with a large number of scaffolds or chromosomes (typically >5,000), the default setting may allocate excessive memory. The official STAR recommendation is to scale this parameter as follows [28] [29]:

--genomeChrBinNbits = min(18, log2[max(GenomeLength/NumberOfReferences, ReadLength)])

For the human genome, using the primary assembly instead of the larger toplevel assembly is a critical first step that significantly reduces the number of references and overall genome length, thereby enabling more effective use of this parameter [15] [30].

--genomeSAsparseD: Controlling Suffix Array Sparsity

The --genomeSAsparseD parameter determines the sparsity of the suffix array (SA) index, which is a core data structure for the aligner. It is defined as the distance between consecutive indices of the suffix array [28] [29]. A higher value creates a sparser index, meaning fewer indices are stored, which reduces RAM consumption during both genome generation and the mapping stage, albeit at the cost of reduced mapping speed [28] [29]. The default value is 1 [28] [29].

This parameter is particularly effective for managing memory with very large genomes. For instance, one reported success involved using --genomeSAsparseD 2 to overcome the 32 GB RAM limit on a MacBook Pro [31]. It is important to note that using a sparser index can potentially lead to differences in read counts compared to the default setting, suggesting a slight trade-off in accuracy for memory efficiency [32].

Table 1: Summary of Key STAR Genome Generation Parameters

| Parameter | Default Value | Function | Effect of Increasing Value | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

--genomeChrBinNbits |

18 [28] [29] | Sets bin size for genome storage (log2(chrBin)) [28] [29]. |

Decreases RAM usage [33]. | Genomes with many scaffolds/contigs [33] [34]. |

--genomeSAsparseD |

1 [28] [29] | Sets sparsity of suffix array index [28] [29]. | Decreases RAM usage, reduces mapping speed [28] [29]. | All genome sizes when RAM is limited [31]. |

--genomeSAindexNbases |

14 [28] [29] | Length of the SA pre-indexing string [28] [29]. | Increases memory use but allows faster searches [28] [29]. | Typically left at default; reduced for small genomes [28]. |

Optimization Strategies for Large Genomes

Primary vs. Toplevel Genome Assemblies

A critical, often overlooked strategy for reducing memory requirements is the selection of an appropriate genome assembly file. The "toplevel" assembly from Ensembl (e.g., Homo_sapiens.GRCh38.dna.toplevel.fa) includes primary chromosomes, unlocalized sequences, and haplotype/patch regions, resulting in a very large file (~60 GB uncompressed) [15] [30]. In contrast, the "primary" or "primary assembly" file (e.g., Homo_sapiens.GRCh38.dna.primary_assembly.fa from Ensembl or the "PRI" files from GENCODE) contains only the primary chromosomes and is significantly smaller (~3 GB uncompressed) [15] [30] [12]. For the vast majority of RNA-seq analyses, including gene expression quantification and differential expression, the primary assembly is sufficient [15] [12]. Switching from the toplevel to the primary assembly is the most effective single action to avoid memory issues, reducing the RAM requirement for the human genome from over 150 GB to a more manageable 30-35 GB [15] [30].

A Strategic Workflow for Parameter Optimization

The following diagram outlines a logical decision process for optimizing STAR genome generation for large genomes, integrating both assembly selection and parameter adjustment.

Quantitative Resource Requirements

Understanding the typical resource requirements for different scenarios is essential for project planning. The following table summarizes key resource considerations based on documented experiences.

Table 2: Resource Requirements and Recommendations for Human Genome Indexing

| Scenario | Genome File | Approx. RAM Required | Reported Successful Parameters | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default (Problematic) | Ensembl Toplevel (~60G) | 150-168 GB | (Fails even with 128 GB RAM) [15] | [15] |

| Standard Primary | GENCODE/GENCODE Primary (~3G) | 30-35 GB | Default parameters sufficient [15] [30] | [15] [30] |

| Constrained Memory | Primary Assembly | < 32 GB | --genomeSAsparseD 2 (or higher) [31] |

[31] |

| Many Scaffolds | Any genome with >5,000 scaffolds | Variable | --genomeChrBinNbits 14 (for wheat genome) [34] |

[34] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating a Human Genome Index with Standard Parameters

This protocol is designed for generating a human genome index where approximately 30-35 GB of RAM is available [15] [30] [12].

- Obtain Genome and Annotation Files: Download the human primary assembly genome FASTA file and corresponding GTF annotation file. GENCODE is recommended for human and mouse data due to its high-quality, reliable annotation [12].

- Example Download Command:

- Decompress Files: STAR requires unzipped input files for genome generation [12].

- Run STAR genomeGenerate: Execute the genome generation command. The

--sjdbOverhangshould be set to the maximum read length minus 1 [12]. For example, for 100-base reads, the value should be 99, and for 150-base reads, 149 [12]. - Post-processing: To save disk space, the genome FASTA file can be re-compressed after the index is successfully built [12].

Protocol 2: Generating a Genome Index Under Memory Constraints

This protocol should be followed when the standard run fails due to insufficient RAM, or when working with limited resources (e.g., less than 32 GB of RAM) [31] [34].

- Follow Protocol 1, Steps 1 and 2: Ensure you are using the primary assembly and have decompressed the files.

- Calculate

--genomeChrBinNbits(if applicable): For genomes with a large number of scaffolds, calculate the value using the recommended formula. For example, for a 17 GBase genome with 735,945 scaffolds, the calculation would belog2(17000000000/735945) ≈ 14.5, so a value of 14 or 15 is appropriate [34]. - Run STAR genomeGenerate with Optimized Parameters: Incorporate the parameters for reducing memory usage. The value for

--genomeSAsparseDcan be incrementally increased (e.g., 2, 3, 4) if memory issues persist [31]. - Verify the Index: Confirm that the output directory contains all necessary index files, including

Genome,SA,SAindex, andgenomeParameters.txt[12].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for STAR Genome Indexing

| Item | Function / Role | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome (FASTA) | The reference sequence to which reads will be aligned. | Use "primary assembly" from GENCODE (human/mouse) or Ensembl. Avoid "toplevel" assemblies [15] [30] [12]. |

| Annotation File (GTF) | Provides gene model information to create the splice junctions database. | Use the annotation that matches your genome FASTA file (e.g., from GENCODE or Ensembl) [12]. |

| STAR Aligner | The software that performs the alignment of RNA-seq reads. | Use a pre-compiled binary for your operating system or compile from source [15]. |

| High-Performance Computing Node | Provides the necessary CPU and memory resources for index generation. | For human primary assembly: Request at least 35 GB RAM and multiple cores. Avoid using all available threads to reserve memory [15] [34]. |

Genome indexing is a critical first step in RNA-seq analysis, enabling efficient alignment of sequencing reads to a reference genome. For the widely used STAR aligner, this process involves pre-processing a reference genome and annotation into a specialized index that facilitates rapid, splice-aware mapping [2]. This resource provides detailed protocols and scripts for executing STAR genome indexing in High-Performance Computing (HPC) and cloud environments, specifically optimized for human genome research.

The following diagram illustrates the complete STAR genome indexing workflow, from data preparation to validation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Computational Resources for STAR Genome Indexing

| Item Name | Specification/Function | Example Source/Details |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome (Human) | FASTA format; primary assembly provides fundamental genomic sequence | GRCh38.primary_assembly.genome.fa from GENCODE [35] |

| Gene Annotation File | GTF format; contains coordinates of known genes, transcripts, and splice junctions | gencode.v29.primary_assembly.annotation.gtf from GENCODE [35] |

| STAR Aligner Software | C++ package for performing alignment and genome indexing | Version 2.7.6a-2.7.11b from GitHub repository [6] [36] |

| High-Memory Compute Node | Essential for holding the genome and complex index structures in RAM | Minimum 32GB for mammalian genomes; 60GB+ recommended for large genomes [6] [7] |

| High-Throughput Storage | Fast read/write capabilities for handling large temporary files during indexing | Local scratch storage (e.g., /scratch directory) recommended [36] |

Example Scripts for Different Environments

HPC Environment with SLURM Scheduler

This example demonstrates genome indexing on an HPC cluster using the SLURM workload manager, configuring parameters specifically for the human genome.

Cloud Environment Implementation

For cloud-based execution, this script illustrates key considerations for optimal performance and cost management in environments like AWS.

Parameter Optimization Guidelines

Table: Critical STAR Indexing Parameters for Human Genome

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Biological & Computational Rationale |

|---|---|---|

--runThreadN |

Match available CPU cores | Parallelizes indexing process; optimal performance typically with 12-32 threads [37] [35] |

--genomeSAindexNbases |

14 for human genome | Sets the length of the suffix array index; calculated as min(14, log2(GenomeLength)/2 - 1) [35] |

--genomeChrBinNbits |

18 for large genomes | Reduces memory usage for genomes with many small contigs or chromosomes [7] |

--sjdbOverhang |

ReadLength - 1 | Optimizes the alignment of reads across splice junctions; typically 74-100 for modern sequencing [2] |

--limitGenomeGenerateRAM |

60000000000 (60GB) | Prevents job failure by capping memory usage, particularly important in shared environments [7] |

Validation and Troubleshooting

Expected Output Files

After successful index generation, your genome directory should contain the following key files [37] [35]:

- Genome: Binary representation of the genome sequence

- SA: Suffix array for rapid sequence searching

- SAindex: Suffix array index

- chrName.txt, chrLength.txt: Chromosome name and length records

- geneInfo.tab, transcriptInfo.tab: Gene and transcript information extracted from GTF

- genomeParameters.txt: Summary of key parameters used for indexing

Common Issues and Solutions

Insufficient Memory Error: For human genomes, ensure at least 32GB of RAM is available, with 60GB recommended for full genomes with comprehensive annotations [6] [7].

Index Generation Failure: If the process terminates prematurely without generating SA and Genome files, check available disk space and adjust

--genomeChrBinNbitsfor genomes with many small contigs [7].Thread Optimization: Benchmark performance with different thread counts; excessive threads may not improve performance due to I/O bottlenecks, particularly in cloud environments with network-attached storage [4].

Performance Considerations for Large-Scale Studies

Recent research on cloud-based transcriptomics has identified several key optimizations for large-scale STAR indexing and alignment workflows [4]:

- Early Stopping: Implementation of early stopping criteria can reduce total alignment time by up to 23%

- Instance Selection: Memory-optimized instances (e.g., AWS r5 series) provide the best price-to-performance ratio

- Spot Instance Usage: Spot instances are viable for alignment jobs, offering significant cost savings with minimal performance impact

- Index Distribution: For multi-node workflows, efficient distribution of pre-built genome indexes to worker instances reduces initialization overhead

Proper configuration of STAR genome indexing parameters is essential for efficient RNA-seq analysis in both HPC and cloud environments. The scripts and parameters provided here, specifically optimized for the human genome, form a robust foundation for transcriptomic studies in drug development and biomedical research. Implementation of these protocols ensures reproducible, high-performance genome indexing, enabling researchers to focus on biological interpretation rather than computational challenges.

Solving Common STAR Indexing Errors and Maximizing Performance

The process of generating a genome index with the Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) aligner is a foundational step in RNA-seq data analysis, yet it presents significant memory challenges for researchers. STAR's unparalleled alignment speed stems from its use of uncompressed suffix arrays during the seed searching phase of its algorithm, which trades off computational speed against substantial RAM usage [38]. For the human genome, this memory requirement typically ranges from 27 GB to 30 GB under standard conditions [39], making it a considerable bottleneck for researchers with limited computational resources. Understanding and managing these memory demands is crucial for successful genomic analyses, particularly as dataset sizes continue to grow. This application note provides detailed methodologies for optimizing STAR genome indexing across various memory configurations, enabling researchers to tailor their computational approaches to available resources while maintaining analytical integrity.

The memory footprint of STAR's genome generation is primarily determined by the size and complexity of the reference genome itself. The algorithm requires the entire genome index to be loaded into memory during the alignment process, with RAM requirements scaling approximately 10 times the genome size [39]. For the human genome (~3.3 gigabases), this translates to approximately 33 GB of RAM under optimal conditions. However, real-world experience shows that these requirements can vary significantly based on specific parameters and genome assembly choices, with some scenarios requiring over 160 GB of RAM when using comprehensive "toplevel" genome assemblies that include haplotype and patch sequences [15].

Table 1: Memory Requirements for STAR Genome Indexing with Human Genome

| Resource Tier | Minimum RAM | Recommended RAM | Genome Assembly Type | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limited (16GB) | 16 GB | 32 GB | Primary Assembly | Requires aggressive parameter optimization; may fail with complex genomes [16] [39] |

| Standard (32GB) | 27-30 GB | 32 GB | Primary Assembly | Suitable for most analyses; handles standard parameters [39] |

| High (128GB+) | 32 GB | 128 GB+ | Toplevel Assembly | Required for comprehensive analyses including patches and haplotypes [15] |

Table 2: Impact of Genome Assembly Choice on Memory Requirements

| Assembly Type | Description | File Size | Estimated RAM Requirement | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Assembly | Main chromosome sequences without haplotypes | Standard (~3 GB) | 30-35 GB [15] | Most standard RNA-seq analyses |

| Toplevel Assembly | Includes chromosomes, unplaced scaffolds, and N-padded haplotypes | Large (~60 GB) [15] | 168 GB+ [15] | Specialized analyses requiring comprehensive genomic context |

The quantitative requirements for STAR genome indexing demonstrate significant variation based on both computational resources and biological material choices. As shown in Table 1, memory requirements span from 16 GB for limited resource environments to 128 GB+ for comprehensive analyses. Table 2 highlights a critical finding from empirical studies: the choice between primary and toplevel genome assemblies dramatically impacts memory requirements, with toplevel assemblies increasing RAM needs by approximately 5-6 times compared to primary assemblies [15]. This distinction is often overlooked in experimental planning but can determine the feasibility of an analysis on available hardware.

Research indicates that the memory-intensive nature of STAR stems from its use of uncompressed suffix arrays, which provide significant speed advantages over compressed implementations used in other aligners [38]. This design choice enables STAR's remarkable mapping speed of 550 million paired-end reads per hour on a 12-core server [38] but necessitates substantial RAM allocation. For most mammalian genomes, the developers recommend at least 16 GB of RAM, with 32 GB being ideal [16], though these are baseline figures that require careful parameter optimization to achieve in practice.

Experimental Protocols for Varied Memory Configurations

Protocol for 16GB RAM Systems

For researchers operating with 16GB RAM systems, successful genome generation requires careful parameter optimization and appropriate genome assembly selection. The following protocol has been empirically validated to work with human genomes on limited-memory systems:

Genome Preparation: Download the primary assembly file (typically named

*primary_assembly.fa) rather than the toplevel assembly. This avoids the excessive memory requirements associated with haplotype and patch sequences [15].Parameter Optimization: Use the specific parameter combination recommended by STAR developer Alexander Dobin [16]:

These parameters reduce the density of the suffix array index (

--genomeSAsparseD 3) and adjust the index base size (--genomeSAindexNbases 12) to decrease memory usage.Execution Considerations: Limit thread count to 1-2 to conserve memory, as higher thread counts increase overall memory footprint. Monitor memory usage during execution using

toporhtopto ensure the system does not exhaust available RAM.

This protocol represents a trade-off between index comprehensiveness and resource constraints. While the resulting index may have slightly reduced sensitivity for complex splice variants, it maintains high utility for standard RNA-seq analyses while enabling operation on consumer-grade hardware.

Protocol for 32GB RAM Systems

With 32GB RAM, researchers can implement STAR genome indexing with standard parameters and primary assembly genomes:

Genome Preparation: Utilize the primary assembly genome file. Verify file integrity and ensure the corresponding GTF annotation file matches the genome build.

Standard Parameter Set:

This configuration allocates 30GB of RAM, leaving 2GB for system operations.

Optional Optimization: If encountering memory issues, consider adjusting the

--genomeChrBinNbitsparameter with values between 12-15 to fine-tune memory allocation [15]. Higher values reduce memory usage but may impact alignment accuracy for some applications.

This configuration represents the standard use case for STAR with human genomes and should successfully complete genome generation within 2-4 hours depending on storage system performance.

Protocol for High-Memory Systems (128GB+)

For research institutions with high-performance computing infrastructure, the comprehensive protocol enables maximum analytical sensitivity:

Genome Selection: Utilize the toplevel genome assembly to include all available genomic context, including haplotype information and patch sequences [15].

Parameter Configuration:

This configuration allocates 120GB of RAM for genome generation, leveraging the full capabilities of high-memory systems.

Validation Step: Following index generation, validate against a test RNA-seq dataset to confirm sensitivity for detecting canonical and non-canonical splice junctions.

The comprehensive approach is particularly valuable for projects aiming to detect rare splice variants, fusion transcripts, or performing population-scale analyses where complete genomic context is essential.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Resources for STAR Genome Indexing

| Resource Category | Specific Solution | Function in Experiment | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | GRCh38 Primary Assembly (GCF_000001405.39) | Standardized reference sequence for alignment | Ensures compatibility with most public RNA-seq data [15] |

| Reference Genome | GRCh38 Toplevel Assembly (incl. patches/haplotypes) | Comprehensive reference for specialized analyses | Required for detecting population variants; increases RAM needs 5x [15] |

| Annotation Resource | GENCODE Basic GTF Annotation | Provides transcript models for junction database | Critical for --sjdbGTFfile parameter; enables splice junction awareness |

| Memory Parameter | --limitGenomeGenerateRAM | Explicitly controls maximum RAM usage during index generation | Must be set lower than available physical RAM to prevent swapping [40] |

| Index Optimization | --genomeSAsparseD | Controls sparsity of suffix array index | Higher values reduce memory but may decrease sensitivity [16] |

| Index Optimization | --genomeSAindexNbases | Adjusts fundamental index structure size | Reduction to 12 enables operation on 16GB systems [16] |

| Azepinomycin | Azepinomycin|C6H8N4O2|RUO | Azepinomycin (C6H8N4O2) is a guanase inhibitor for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or diagnostic use. | Bench Chemicals |

The research reagents and computational parameters detailed in Table 3 represent the essential components for successful STAR genome indexing experiments. Beyond the computational parameters, the choice of reference genome assembly emerges as perhaps the most critical determinant of experimental success. The primary assembly, containing only the standard chromosome sequences without alternative haplotypes, provides the most memory-efficient option and should be the default choice for most applications [15]. In contrast, the toplevel assembly includes all sequence regions flagged as toplevel in the Ensembl schema, including chromosomes, regions not assembled into chromosomes, and N-padded haplotype/patch regions, making it substantially more memory-intensive but also more comprehensive for specialized analyses.

The biochemical reagents used in RNA sequencing protocols indirectly influence computational requirements through their impact on read length and quality. The --sjdbOverhang parameter should be set to the maximum read length minus 1, reflecting the biochemical preparation of sequencing libraries [15]. For most contemporary Illumina sequencing runs, values between 99-149 are appropriate and influence the construction of the junction database during genome indexing.

Alternative Aligner Considerations for Memory-Limited Environments

When computational resources are insufficient for STAR genome indexing even with optimized parameters, alternative aligners with lower memory footprints present viable options. HISAT2 (hierarchical indexing for spliced alignment of transcripts) represents the most directly relevant alternative, requiring only 4.3 gigabytes of memory for human genome alignment while maintaining competitive accuracy [41]. This remarkable reduction in memory requirements stems from HISAT2's use of a hierarchical indexing scheme based on the Burrows-Wheeler transform and FM index, employing both a whole-genome index for alignment anchoring and numerous local indexes for rapid extension of alignments.

The transition from STAR to HISAT2 involves both conceptual and practical considerations. While STAR excels in mapping speed and sensitivity for novel junction detection, HISAT2 provides a more resource-efficient solution suitable for standard RNA-seq analyses on consumer hardware. For researchers with 16GB RAM systems where STAR indexing fails even with optimized parameters, HISAT2 offers a scientifically rigorous alternative without requiring hardware upgrades. Additionally, pre-built HISAT2 indexes are readily available for common reference genomes, eliminating the need for local index generation altogether.

For researchers requiring the specific analytical capabilities of STAR but lacking sufficient local resources, cloud-based genomic analysis platforms provide another alternative. These services offer on-demand access to high-memory computational instances, enabling STAR genome indexing without capital investment in hardware. The economic trade-offs between cloud computing costs and local hardware investment depend on project scope and frequency of analysis, with cloud solutions typically favoring occasional users and local hardware benefiting high-volume laboratories.

Effective management of memory limitations during STAR genome indexing requires a comprehensive understanding of both computational parameters and biological reagent choices. This application note demonstrates that successful human genome indexing is achievable across a spectrum of hardware configurations, from 16GB consumer systems to 128GB+ high-performance workstations, through appropriate parameter optimization and informed genome assembly selection. The critical distinction between primary and toplevel genome assemblies, with their dramatically different memory profiles, provides researchers with a fundamental choice between resource efficiency and analytical comprehensiveness.

The ongoing evolution of sequencing technologies toward longer reads and higher throughput continues to intensify computational demands, making resource-aware analytical strategies increasingly valuable. The parameter optimizations and decision frameworks presented here enable researchers to maintain analytical quality within hardware constraints, ensuring the accessibility of advanced RNA-seq analysis to laboratories with varying computational resources. As genomic medicine progresses toward clinical applications, these resource-optimized protocols will play an essential role in democratizing access to cutting-edge analytical capabilities across diverse research environments.

Within the context of a broader thesis on optimizing STAR genome indexing parameters for human genome research, managing computational resources is a foundational challenge. Researchers in genomics and drug development frequently encounter two primary issues when using the STAR aligner: jobs that are inexplicably "killed" without error messages, or alignment processes that run for excessively long times, sometimes exceeding 24 hours [42] [27]. These interruptions significantly hinder research progress in critical areas such as gene expression analysis, variant discovery, and therapeutic development. This application note provides detailed, evidence-based protocols to diagnose, prevent, and resolve these computational bottlenecks, enabling more efficient and successful RNA-seq analysis workflows. The strategies outlined below are particularly crucial for human genome studies, where the scale of data and reference genomes presents unique computational demands.

Diagnosing the Problem: Killed Jobs and Excessive Run Times

Root Cause Analysis

The "killed" status in STAR jobs, particularly during the genome indexing phase, almost invariably indicates that the operating system's Out-of-Memory (OOM) killer has terminated the process. This occurs when the physical RAM is exhausted, and the system begins to swap to disk, leading to a catastrophic performance degradation followed by process termination [42] [43]. One user reported: "This process kept on getting killed without a clear error message," which is characteristic of OOM killer intervention [42]. For human genome indexing, STAR requires approximately 30 GB of RAM as a minimum, with 32 GB recommended for stable operation [24] [27]. When insufficient memory is available, the process may run for an extended period while swapping occurs before ultimately being terminated, creating the appearance of a "long-running" job that eventually fails.

Quantitative Resource Requirements

Table 1: STAR Resource Requirements for Human Genome (hg38)

| Process Stage | Minimum RAM | Recommended RAM | Expected Duration | CPU Threads |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Indexing | 30 GB | 32-64 GB | 1-2 hours (with sufficient RAM) | 4-8 |

| Read Alignment | 16 GB | 32 GB | Varies by dataset size | 4-16 |

Evidence from multiple user reports confirms that upgrading from 16 GB to 64 GB of RAM resolved previously failed indexing jobs [42]. Another user reported that jobs running for over 24 hours were likely due to insufficient RAM causing extensive swapping [27]. The relationship between memory allocation and successful completion is therefore direct and quantifiable.

Experimental Protocols for Resolving STAR Job Failures

Protocol 1: Optimized Genome Index Generation for Limited RAM Environments

This protocol provides a method for generating STAR genome indices when system RAM is constrained, using parameter adjustments that reduce memory footprint at the cost of increased computation time.

Necessary Resources:

- Computer system with Unix, Linux, or Mac OS X

- Minimum 16 GB RAM (32 GB recommended)

- Sufficient disk space (>100 GB)

- STAR software installed from GitHub repository [6]

- Reference genome in FASTA format

- Gene annotations in GTF format

Methodology:

- Create a directory for genome indices:

mkdir /path/to/genomeDir - Execute the modified genome generation command with memory-optimized parameters:

Parameters Explanation:

--genomeChrBinNbits 14: Reduces the number of bits for chromosome bins, decreasing RAM usage for genomes with many small chromosomes [27].--genomeSAsparseD 2: Controls the sparsity of the suffix array, reducing memory requirements [42].--runThreadN 4: Limits thread count to prevent memory overcommitment, even on systems with more cores [27].

Validation:

Successful index generation produces a complete set of files in the genomeDir, including Genome, SA, SAindex, and various .tab information files. Incomplete file sets (missing Genome or SA files) indicate premature termination, typically due to insufficient RAM despite parameter adjustments [7].

Protocol 2: Two-Pass Alignment for Enhanced Spliced Alignment Accuracy

This protocol implements a two-pass alignment strategy that improves detection of novel splice junctions while managing computational resources effectively.

Necessary Resources:

- Pre-generated genome indices (from Protocol 1)

- RNA-seq reads in FASTQ format (single-end or paired-end)

- Sufficient disk space for temporary files

Methodology:

- First Pass: Discover novel splice junctions by aligning reads with basic parameters

- Second Pass: Incorporate discovered junctions from the first pass for refined alignment

This approach is particularly valuable for human transcriptome studies where novel isoform discovery is critical for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets [24].

Computational Resource Strategies

Resource Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting the appropriate strategy based on available resources and research goals:

Infrastructure Solutions for Large-Scale Studies

For drug development research involving large-scale RNA-seq analyses, alternative computational infrastructures provide practical solutions:

High-Performance Computing (HPC) Clusters: Migration to institutional HPC clusters represents the most straightforward solution, as confirmed by users who resolved failures by "moving to the lab's cluster" [42]. These environments typically provide sufficient RAM (64-512 GB per node) and parallel processing capabilities that dramatically reduce alignment times from days to hours.

Cloud-Based Solutions: Serverless container platforms like AWS ECS with Fargate provide viable alternatives for human genome alignment, supporting up to 120 GB of RAM and 14-day execution windows [44]. In comparative studies, processing 17 TB of sequence data cost approximately $127 using ECS versus $96 using traditional EC2 instances, making cloud solutions cost-effective for small to medium-scale batch processing without requiring institutional HPC access [44].

Alternative Aligner Considerations: When resource constraints cannot be overcome, HISAT2 represents a memory-efficient alternative that maintains good accuracy for splice-aware alignment [42]. While STAR generally provides superior accuracy and speed on well-resourced systems, HISAT2 requires significantly less memory, making it suitable for standard workstations conducting human transcriptome analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Research Reagents for STAR Alignment

| Resource Category | Specific Solution | Function in Workflow | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Genomes | GRCh38 (hg38) FASTA files | Provides reference sequence for alignment | Download from ENSEMBL or UCBI genome browsers |

| Gene Annotations | ENSEMBL GTF files (release 109+) | Defines known splice junctions for accurate alignment | --sjdbGTFfile Homo_sapiens.GRCh38.109.gtf |

| Pre-computed Indices | Publicly available genome indices | Bypasses resource-intensive index generation | STAR Pre-built Indices |

| Memory Optimization | --genomeChrBinNbits parameter |

Reduces RAM requirements for large genomes | --genomeChrBinNbits 14 for human genome |

| Sparse Indexing | --genomeSAsparseD parameter |

Controls suffix array sparsity to manage memory | --genomeSAsparseD 2 for memory-constrained systems |

Successful execution of STAR alignment for human genome research requires careful attention to computational resource allocation, particularly RAM requirements during the genome indexing phase. By implementing the protocols outlined in this application note—including memory-optimized parameters, two-pass alignment strategies, and appropriate infrastructure selection—researchers can overcome the challenges of killed jobs and excessive run times. These solutions enable more efficient and reliable RNA-seq analysis pipelines, accelerating research in gene expression studies, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic development. For ongoing optimization, researchers should monitor the official STAR GitHub repository for updates and new parameter recommendations as the software continues to evolve.