qPCR Data Normalization: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Validation, and Troubleshooting for Reliable Gene Expression Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide to qPCR data normalization, a critical step for ensuring the accuracy and reproducibility of gene expression results in biomedical research and drug development. It covers foundational principles, from the necessity of normalization to minimize technical variability to the detailed mechanics of the ΔΔCq method. The guide explores established and emerging methodological strategies, including the use of single or multiple reference genes and global mean normalization. It delivers practical troubleshooting advice for common pitfalls and a rigorous framework for validating and comparing normalization approaches, empowering researchers to produce robust, reliable, and publication-ready data.

qPCR Data Normalization: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Validation, and Troubleshooting for Reliable Gene Expression Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to qPCR data normalization, a critical step for ensuring the accuracy and reproducibility of gene expression results in biomedical research and drug development. It covers foundational principles, from the necessity of normalization to minimize technical variability to the detailed mechanics of the ΔΔCq method. The guide explores established and emerging methodological strategies, including the use of single or multiple reference genes and global mean normalization. It delivers practical troubleshooting advice for common pitfalls and a rigorous framework for validating and comparing normalization approaches, empowering researchers to produce robust, reliable, and publication-ready data.

Why Normalization is Non-Negotiable: The Foundation of Accurate qPCR Data

The Critical Role of Normalization in Minimizing Technical Variability

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary goal of normalization in qPCR experiments?

Normalization aims to eliminate technical variation introduced during sampling, RNA extraction, and cDNA synthesis procedures. This ensures your analysis focuses exclusively on biological variation resulting from experimental intervention rather than technical artifacts. Proper normalization is fundamental for accurate data quantification and interpretation [1] [2].

How many reference genes should I use for reliable normalization?

The MIQE guidelines recommend using at least two validated reference genes [3]. However, studies have shown that using three or more stable reference genes can provide even more robust normalization. For example, one study identified HPRT, 36B4, and HMBS as a stable triplet for reliable normalization in adipocyte research [4], while another found RPS5, RPL8, and HMBS formed a stable combination for canine gastrointestinal tissue [1].

Can I use a single reference gene like GAPDH or ACTB?

Using a single reference gene, particularly without validation, is strongly discouraged. Commonly used genes like GAPDH and ACTB have frequently been shown to exhibit variable expression under different experimental conditions. One study concluded that "the widely used putative genes in similar studies—GAPDH and Actb—did not confirm their presumed stability," emphasizing the need for experimental validation of internal controls [4].

What alternative methods exist beyond traditional reference gene approaches?

Several data-driven normalization methods offer alternatives to traditional reference genes, particularly when profiling many genes:

- Global Mean (GM): Uses the average expression of all profiled genes; performs well when profiling >55 genes [1]

- Quantile Normalization: Assumes the overall distribution of gene expression is constant across samples [5]

- Rank-Invariant Set Normalization: Identifies genes with stable rank order across conditions from your dataset [5]

- NORMA-Gene: Uses a least squares regression algorithm to calculate a normalization factor [3]

How do I validate the stability of my reference genes?

Stability should be assessed using specialized algorithms:

- geNorm: Calculates stability measure M; lower M values indicate greater stability [1] [4]

- NormFinder: Evaluates intra- and inter-group variation [1] [3]

- BestKeeper: Uses raw Cq values to determine stability [4]

- RefFinder: Aggregates results from multiple algorithms [3]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Technical Variation Persists After Normalization

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Gene Selection | Using unvalidated single reference gene | Validate multiple genes (2-3) using geNorm/NormFinder [1] [4] |

| Sample Quality | Degraded RNA or inconsistent cDNA synthesis | Check RNA integrity, use consistent reverse transcription protocols [6] |

| Amplification Efficiency | Varying efficiency between target/reference genes | Determine efficiency via standard curve, apply corrections [6] |

| Normalization Method | Suboptimal method for your experimental design | Consider switching to global mean for large gene sets (>55 genes) [1] |

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Technical Replicates

Investigation Protocol:

- Check Amplification Efficiency: Confirm efficiencies between 90-110% for all assays [1]

- Verify Replicate Consistency: Remove replicates differing by >2 PCR cycles [1]

- Assess Reaction Quality: Identify bubbles or irregularities in PCR runs [1]

- Evaluate Specificity: Check for single peaks in melting curves [3]

Problem: Reference Gene Performance Varies Across Experimental Conditions

Solution Strategy:

- Pre-validation: Test candidate reference genes in pilot studies matching your experimental conditions [4]

- Multi-Algorithm Assessment: Use both geNorm and NormFinder for complementary stability assessment [1]

- Functionally Diverse Genes: Select reference genes from different functional pathways to avoid co-regulation [1]

- Alternative Methods: Consider data-driven normalization (NORMA-Gene, quantile) if stable reference genes cannot be identified [5] [3]

Normalization Method Comparison

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of different normalization approaches based on recent studies:

| Normalization Method | Optimal Use Case | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Reference Genes (2-3 validated) | Most qPCR studies with limited targets | Well-established, MIQE-compliant | Requires validation, reduces sample for targets [1] [4] |

| Global Mean (GM) | Large gene sets (>55 genes) | Data-driven, no pre-selection | Requires many genes, not for small panels [1] |

| NORMA-Gene | Studies with ≥5 target genes | Reduces variance effectively, fewer resources | Less familiar to reviewers [3] |

| Quantile Normalization | High-throughput qPCR across multiple plates | Corrects plate effects, robust distribution alignment | Complex implementation, assumes same distribution [5] |

| Pairwise/Triplet Normalization | miRNA studies, diagnostic panels | High accuracy, model stability | Computational complexity [7] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Reference Gene Validation for qPCR Normalization

Purpose: To identify and validate stable reference genes for specific experimental conditions.

Materials:

- cDNA samples from all experimental conditions

- qPCR reagents and instrument

- Primers for candidate reference genes (minimum 6-8 candidates recommended)

Procedure:

- Select Candidate Genes: Choose 6-8 candidate reference genes from different functional classes [4]

- qPCR Amplification: Run all candidates across all experimental samples (minimum 3 biological replicates per condition)

- Data Quality Control:

- Stability Analysis:

- Final Selection: Choose 2-3 most stable genes with different biological functions [1]

Protocol 2: Global Mean Normalization Implementation

Purpose: To implement global mean normalization when profiling large gene sets.

Materials:

- qPCR data for all genes across all samples

- Statistical software (R, Python, or specialized packages)

Procedure:

- Data Curation:

- Calculate Global Mean:

- Compute average Cq value of all genes for each sample [1]

- Normalize Expression:

- Subtract sample-specific global mean from each gene's Cq value

- Alternatively, use the global mean as denominator in 2^(-ΔΔCq) calculations

- Performance Validation:

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Normalization |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Gene Assays | RPS5, RPL8, HMBS, HPRT1, HSP90AA1, B2M | Stable endogenous controls for sample-to-sample variation [1] [3] |

| RNA Quality Tools | RNeasy Mini Kits, QIAzol Lysis Reagent, DNase treatment kits | Ensure input RNA quality and genomic DNA removal [3] [4] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green, TaqMan probes, Power SYBR Green chemistry | Consistent amplification chemistry across samples [2] [8] |

| Stability Analysis Software | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, RefFinder | Algorithmic assessment of reference gene stability [1] [3] [4] |

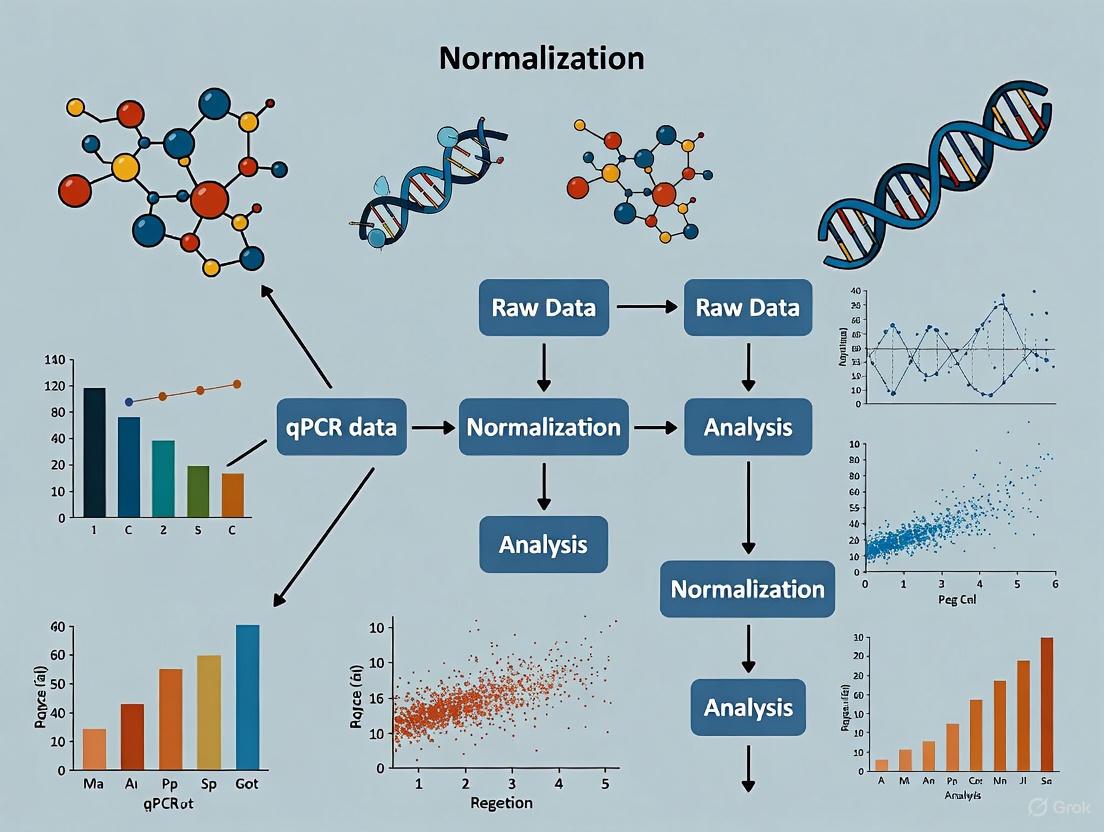

Workflow Diagram: qPCR Normalization Strategy Selection

Technical Note: Statistical Approaches Beyond 2^(-ΔΔCq)

While the 2^(-ΔΔCq) method remains widely used, recent research suggests alternative statistical approaches can provide enhanced rigor. Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) offers greater statistical power and isn't affected by variability in qPCR amplification efficiency. ANCOVA uses raw Cq values as the response variable in a linear model, providing a flexible multivariable approach to differential expression analysis [9].

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) is a powerful technique for quantifying nucleic acids, but its accuracy and reproducibility are heavily influenced by multiple sources of variation. Understanding and controlling these variables is crucial for generating reliable, publication-quality data, especially in the context of normalizing qPCR data for gene expression studies.

Variation in a qPCR experiment can be categorized into three main types: system variation (inherent to the measuring equipment and reagents), biological variation (true variation in target quantity among samples within the same group), and experimental variation (the measured variation which estimates biological variation) [10]. System variation can significantly impact experimental variation, making its minimization a primary goal during experimental design and execution [10].

Pre-Analytical Variation

Pre-analytical variation encompasses all inconsistencies occurring before the qPCR run itself, from sample collection to cDNA synthesis.

Sample Collection and Storage

The initial steps of handling biological material introduce significant variability. Using a dedicated pre-PCR workspace, physically separated from post-PCR areas, is essential to prevent contamination from amplified PCR products [11]. Samples should be stored correctly; DNA is best preserved at -20°C or -70°C under slightly basic conditions to prevent depurination [11].

Nucleic Acid Extraction and Quality Assessment

The quality of the starting template is paramount. Inaccurate quantification of nucleic acid concentration or the presence of inhibitors can severely skew results.

- Purity and Concentration: Use a spectrophotometer or fluorometer to assess sample quality and concentration. A 260/280 nm absorbance ratio within 1.8-2.0 indicates pure DNA [11].

- Inhibitors: Template material containing inhibitors is a common cause of poor amplification efficiency, unusually shaped amplification curves, and irreproducible data [12]. Diluting the input sample can sometimes mitigate this effect [12].

Reverse Transcription and cDNA Synthesis

The reverse transcription step, crucial for gene expression analysis, is a major source of variability.

- gDNA Contamination: Genomic DNA (gDNA) contamination in RNA samples can lead to falsely early Cq values. A recommended corrective step is to treat RNA samples with DNase before reverse transcription [12].

- Reagent Quality: Degraded reagents or inefficient reverse transcription can lead to failed reactions and "no data" outcomes [12]. Using master mixes that include reagents to remove gDNA and inhibit RNase activity is a best practice [11].

Analytical Variation

Analytical variation arises during the setup and execution of the qPCR reaction.

Reagent Quality and Pipetting

- Reagent Integrity: Degraded reagents, such as dNTPs or master mix, can result in a lower-than-expected amplification plateau [12]. Aliquoting reagents prevents degradation from multiple freeze-thaw cycles and reduces contamination risk [11].

- Pipetting Error: This is a primary contributor to system variation and can lead to high variability between technical replicates (Cq differences > 0.5 cycles) [12]. To improve precision, calibrate pipettes regularly, use positive-displacement pipettes with filtered tips, and ensure proper vertical pipetting technique [12] [10].

Reaction Plate Setup and Instrumentation

- Plate Preparation: Bubbles in a well can cause baseline drift and a jagged amplification signal [12]. After sealing the plate, centrifuging it removes bubbles and ensures all liquid is at the bottom of the wells [10].

- Instrument Performance: Regular maintenance, including temperature verification and calibration, is necessary for optimal instrument performance [10].

Assay Design and Optimization

- Primer Design: Poor primer specificity can cause multiple issues, including unexpected data values, earlier-than-anticipated Cq values (due to non-specific amplification or primer-dimer formation), and irreproducible data [12]. Primers should be designed to have similar melting temperatures (within 2-5°C), and their formation of primer-dimers should be checked with melt curve analysis [12] [11].

- Amplification Efficiency: Poor PCR efficiency, potentially caused by an inappropriate annealing temperature or unanticipated variants in the target sequence, leads to unusually shaped amplification curves and later-than-expected Cq values [12]. Assay efficiency should be optimized and tested against carefully quantified controls [12].

The following workflow summarizes the key sources of variation and their impact on the qPCR process:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My No Template Control (NTC) shows exponential amplification. What is wrong? This indicates contamination, likely from laboratory exposure to the target sequence or from the reagents themselves. Corrective steps include cleaning the work area with 10% bleach, preparing the reaction mix in a clean lab space separated from template sources, and ordering new reagent stocks [12].

Q2: The amplification curves for my samples are jagged. What could be the cause? A jagged signal throughout the amplification plot is often due to poor amplification, a weak probe signal, or a mechanical error. Ensure a sufficient amount of probe is used, try a fresh batch of probe, and mix the primer/probe/master solution thoroughly during reaction setup [12].

Q3: My technical replicates are too variable (Cq difference > 0.5 cycles). How can I fix this? High variability between technical replicates is commonly caused by pipetting error or insufficient mixing of solutions. Calibrate your pipettes, use positive-displacement pipettes with filtered tips, and mix all solutions thoroughly during preparation [12].

Q4: I see a much lower plateau phase than expected. What does this mean? A low plateau suggests limiting or degraded reagents (e.g., dNTPs or master mix), an inefficient reaction, or incorrect probe concentration. Check your master mix calculations and repeat the experiment with fresh stock solutions [12].

Q5: What is the difference between technical and biological replicates? Technical replicates are repetitions of the same sample reaction, helping to estimate system precision and identify outliers. Biological replicates are different samples from the same experimental group, accounting for the natural variation within a population. Both are essential for robust statistical analysis [10].

Troubleshooting Guide for Common qPCR Issues

The table below summarizes frequent problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions based on observed amplification curve anomalies and data outputs.

| Observation | Potential Causes | Corrective Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Exponential amplification in NTC [12] | Contamination from lab environment or reagents. | Clean work area with 10% bleach; use new reagent stocks; prepare mix in a clean lab [12] [11]. |

| High noise in early cycles; data point looping [12] | Baseline set too early; too much template. | Reset baseline; dilute input sample to within linear range [12]. |

| Unusually shaped amplification; late Cq [12] | Poor reaction efficiency; inhibitors; suboptimal annealing temperature. | Optimize primer concentration and annealing temp; redesign primers; dilute sample to reduce inhibitors [12]. |

| Plateau much lower than expected [12] | Limiting or degraded reagents; inefficient reaction. | Check master mix calculations; repeat with fresh stock solutions [12] [11]. |

| Cq much earlier than anticipated [12] | gDNA contamination in RNA; high primer-dimer; poor specificity. | DNase-treat RNA; redesign primers for specificity; optimize annealing temperature [12]. |

| Jagged amplification signal [12] | Poor amplification/weak probe; mechanical error; bubble in well. | Use more probe; try fresh probe; mix solutions thoroughly; centrifuge plate [12] [10]. |

| Variable technical replicates (Cq >0.5 cycles apart) [12] | Pipetting error; insufficient mixing; low expression. | Calibrate pipettes; use filtered tips; mix solutions thoroughly; add more sample [12]. |

| Irreproducible sample comparisons [12] | Low amplification efficiency; RNA degradation; inaccurate dilutions. | Redesign primers; repeat with fresh reagents/sample; check sample dilutions [12]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials crucial for minimizing variation and ensuring successful qPCR experiments.

| Item | Function | Best Practice / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Filtered Pipette Tips [12] [11] | To prevent aerosol contamination from entering the pipette barrel and cross-contaminating samples. | Use consistently for all pre-PCR setup. |

| Master Mix [11] | A pre-mixed solution containing core PCR reagents (e.g., Taq polymerase, dNTPs, buffer). | Reduces pipetting steps, well-to-well variation, and improves reproducibility. |

| Nuclease-Free Water [11] | Used to dilute samples and as a component in reactions. | Should be autoclaved and filtered through a 0.45-micron filter dedicated to pre-PCR use. |

| UNG (Uracil-N-Glycosylase) [11] | Enzyme used in some master mixes to prevent carryover contamination from previous PCR products. | Renders prior dUTP-containing amplicons non-amplifiable. |

| Passive Reference Dye [10] | A dye included in the reaction at a fixed concentration to normalize for non-PCR-related fluorescence variations. | Corrects for differences in well volume and optical anomalies, improving precision. |

| DNase I [12] | Enzyme that degrades genomic DNA. | Critical for RNA work to prevent false positives from gDNA contamination during RT-qPCR. |

| Stable Reference Genes (RGs) [1] [13] | Genes used for data normalization to correct for technical variation. | Must be validated for stability under specific experimental conditions; using a combination of RGs is often best. |

| 3-Methylglutarylcarnitine | 3-Methylglutarylcarnitine, CAS:102673-95-0, MF:C13H23NO6, MW:289.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 8-Dehydrocholesterol | 8-Dehydrocholesterol (8-DHC) for SLOS Research |

Normalization Strategies to Minimize Variation

Normalization is a critical process to minimize technical variability and reveal true biological variation [1]. The choice of strategy can significantly impact data interpretation.

Reference Gene (RG) Normalization

This is the most common method, using internal control genes presumed to be stably expressed across all samples.

- Validation is Crucial: So-called "housekeeping" genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) are not always stable. Their expression can vary with tissue type, disease state, and experimental conditions [1] [13]. It is essential to validate RG stability for each specific experimental setup.

- Use Multiple RGs: The MIQE guidelines recommend using more than one verified reference gene [1]. Using a combination of stable genes can balance out minor fluctuations in individual genes. GeNorm and NormFinder are standard algorithms used to rank candidate RGs by their expression stability [1] [13].

Global Mean (GM) Normalization

This method uses the geometric mean of the expression of a large number of genes (often tens to hundreds) as the normalizer.

- When to Use: The GM method can be a superior alternative to RGs, particularly when profiling many genes. One study found GM to be the best-performing method for reducing technical variability when more than 55 genes were profiled [1].

- Advantage: It does not rely on the stability of a small number of pre-selected genes, potentially offering a more robust normalization factor.

The Gene Combination Method

An emerging approach involves finding an optimal combination of a fixed number (k) of genes whose individual expressions balance each other across all conditions of interest, even if the individual genes are not particularly stable [13]. This method can be identified in silico using comprehensive RNA-Seq databases before experimental validation [13].

Core Principles of the 2^(-ΔΔCq) Method for Relative Quantification

The 2-ΔΔCq method (commonly known as the 2-ΔΔCt method) is a foundational strategy in quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) for determining relative changes in gene expression [14]. This approach calculates the fold change in expression of a target gene between an experimental sample and a reference sample (such as an untreated control), normalized to one or more reference genes used as an internal control [15]. Its widespread adoption is largely due to its convenience, as it directly uses the threshold cycle (Cq or Ct) values generated by the qPCR instrument, eliminating the need for constructing standard curves in every run [16] [17].

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundation

The 2-ΔΔCq method is built upon several key principles and mathematical assumptions that researchers must understand to apply it correctly.

The Mathematical Workflow

The calculation follows a clear, stepwise procedure to arrive at the final fold-change value [17]:

Calculate ΔCq for Each Sample: For every sample (both test and control), subtract the Cq of the reference gene from the Cq of the target gene.

- ΔCq (test) = Cq (target, test) - Cq (ref, test)

- ΔCq (control) = Cq (target, control) - Cq (ref, control)

Calculate ΔΔCq: Subtract the ΔCq of the control sample from the ΔCq of the test sample.

- ΔΔCq = ΔCq (test) - ΔCq (control)

Calculate Fold Change: Use the result as the exponent for base 2.

- Fold Change = 2^(-ΔΔCq)

The final value represents the fold change of your gene of interest in the test condition relative to the control, normalized to the reference gene[s] [17]. A value of 1 indicates no change, a value above 1 indicates upregulation, and a value below 1 indicates downregulation.

Foundational Assumptions

The validity of the 2-ΔΔCq method rests on three critical assumptions [16] [17]:

- Optimal PCR Efficiency: The method assumes that the amplification efficiencies of both the target and reference genes are 100%, meaning the amount of PCR product doubles every cycle (represented by the base of 2 in the formula) [16].

- Equal Efficiencies: It assumes that the amplification efficiencies of the target and reference genes are approximately equal [15].

- Stable Reference Genes: The reference gene(s) must be stably expressed across all experimental conditions and unaffected by the experimental treatment [17].

Comparison of qPCR Quantification Methods

The 2-ΔΔCq method is one of several approaches for analyzing qPCR data. Understanding its position relative to other methods provides context for its appropriate application [15] [18].

| Method | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-ΔΔCq (Relative) | Calculates fold change relative to a calibrator sample, normalized to a reference gene [14]. | No standard curve needed; increased throughput; simple calculation [15]. | Relies on strict efficiency and reference gene stability assumptions [16]. | Large number of samples, few genes, when assumptions are validated [17]. |

| Standard Curve (Relative) | Determines relative quantity from a standard curve, normalized to a reference gene [15]. | Less optimization than comparative CT; runs target and control in separate wells [15]. | Requires running a standard curve, uses more wells [15]. | When amplification efficiencies are not equal or are unknown [15]. |

| Standard Curve (Absolute) | Relates Cq to a standard curve with known starting quantities to find absolute copy number [18]. | Provides absolute copy number, not just fold change [18]. | Requires pure, accurately quantified standards; prone to dilution errors [15]. | Determining absolute viral copies, transgene copies [15] [18]. |

| Digital PCR (Absolute) | Partitions sample into many reactions and counts positive vs. negative partitions [15]. | No standards needed; highly precise; tolerant to inhibitors [15]. | Requires specialized instrumentation; limited dynamic range. | Absolute quantification of rare alleles, copy number variation [15]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Validating the 2-ΔΔCq Method

Q1: How do I validate that my primers have near-100% and equal amplification efficiencies? A validation experiment is required before using the 2-ΔΔCq method [15]. Prepare a serial dilution (e.g., 1:10) of your cDNA sample and run it with both your target and reference gene primers. Plot the Cq values against the logarithm of the dilution factor. The slope of the resulting standard curve should be between -3.1 and -3.6, which corresponds to an efficiency between 110% and 90% [19]. The efficiencies for the target and reference genes must be within 5% of each other to use this method reliably [17].

Q2: My reference gene seems to be regulated by the experimental treatment. What should I do? Using an unstable reference gene is a major source of inaccurate results. You should [1]:

- Test multiple reference genes: Identify and use the most stable ones.

- Use a geometric mean of multiple genes: Combining several stable reference genes (e.g., the 2-3 most stable) increases normalization accuracy [1].

- Consider data-driven normalization: For high-throughput qPCR (dozens to hundreds of genes), methods like the Global Mean (GM) or Quantile Normalization can be more robust alternatives, as they use the entire dataset for normalization rather than relying on a few pre-selected genes [5] [1].

Q3: My fold change results seem biologically implausible. What could be wrong? Implausible results often stem from violations of the method's core assumptions [16] [19]:

- Check PCR Efficiencies: Re-run the validation experiment. Even small efficiency differences between target and reference genes can lead to large miscalculations [19].

- Review Cq Values: Check for very high Cq values (e.g., >35), which indicate low template concentration and increased variability. Also, ensure the background fluorescence has been correctly handled, as improper subtraction can distort results [16].

- Re-inspect Raw Data: Always look at the amplification and melt curves for anomalies like primer-dimers or non-specific amplification, which can lead to inaccurate Cq calls [19].

Q4: Can I compare ΔCq or ΔΔCq values directly between different experimental runs or laboratories? No, this is not recommended. Cq values are highly dependent on machine-specific settings, the chosen quantification threshold, and reagent efficiencies, which can vary between runs and laboratories [19]. The 2-ΔΔCq calculation is designed for comparison within a single, optimally calibrated run. For comparisons across runs, the use of an inter-run calibrator sample is advised.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines essential materials and their critical functions in a typical 2-ΔΔCq experiment.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Primers | To amplify the target and reference genes with high specificity. | Must be validated for efficiency and specificity. Amplicon length should be kept similar [18]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and fluorescent dye (e.g., SYBR Green) for detection. | Choice of dye or probe chemistry affects sensitivity and specificity [19]. |

| RNA/DNA Template | The sample material containing the genetic target to be quantified. | For gene expression, high-quality RNA with a high RIN is crucial. Input amount must be consistent [19]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | (For gene expression) Converts RNA to cDNA for PCR amplification. | RT efficiency can be a major source of variation and should be kept consistent across samples [15]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Serves as a solvent and negative control. | Essential for preventing degradation of reagents and templates. |

| Validated Reference Genes | Used for normalization of technical variations. | Must be confirmed to be stable under your specific experimental conditions (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB, ribosomal genes) [16] [1]. |

Normalization is a critical step in the analysis of quantitative PCR (qPCR) data, serving to minimize technical variability introduced during sample processing so that the analysis focuses on true biological variation. When performed poorly or omitted, normalization can lead to severe data misinterpretation and irreproducible results, undermining research validity. This guide details the consequences of inadequate normalization and provides troubleshooting advice to help researchers avoid these common pitfalls, framed within the broader context of methodological rigor in qPCR research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary purpose of normalizing qPCR data? Normalization aims to eliminate technical variation introduced during sampling, RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and loading differences. This ensures that observed gene expression changes result from biological variation due to the experimental intervention and not from technical artifacts [1].

2. Why is using a single reference gene like GAPDH or ACTB often insufficient? Using a single reference gene is problematic because so-called "housekeeping" genes can vary under different physiological or pathological conditions. For example, studies have shown that GAPDH is not stable in models of age-induced neuronal apoptosis, and ACTB varies in ischemic/hypoxic conditions [20]. Relying on a single, unstable gene for normalization can introduce significant bias.

3. What are the minimum information guidelines for publishing qPCR experiments? The MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines were established to standardize reporting and avoid misinterpretations. A key recommendation is using multiple, validated reference genes for reliable normalization, not just one [20] [9].

4. When can the global mean (GM) method be a good alternative to reference genes? The global mean of expression of all profiled genes can be a robust normalization strategy, particularly when a large number of genes (e.g., more than 55) are being assayed. One study found GM to be the best-performing method for reducing variability in complex sample sets [1].

5. How can poor normalization affect my final results? Poor normalization can skew normalized data, causing a significant bias. This can lead to both false-positive results (type I errors), where you believe an effect exists when it does not, and false-negative results (type II errors), where you miss genuine biological effects [21].

Troubleshooting Common Normalization Problems

Problem 1: Unstable Reference Genes

- Symptoms: High variability in target gene expression within the same treatment group; reference gene expression shows significant changes across experimental conditions.

- Causes: The chosen reference gene is regulated by the experimental treatment. This is common in processes like ageing or disease states. For instance, in a study of ageing mouse brains, common reference genes like Hmbs, Sdha, and ActinB showed statistically significant variation in structures like the hippocampus and cerebellum [20].

- Solutions:

- Validate Gene Stability: Prior to your main experiment, test candidate reference genes using algorithms like GeNorm or NormFinder to rank their stability in your specific experimental system [20] [1].

- Use Multiple Genes: Never rely on a single gene. Normalize using a normalization factor based on the geometric mean of several (at least two) of the most stable reference genes [20].

- Choose Functionally Diverse Genes: If using multiple reference genes, avoid selecting genes from the same functional pathway (e.g., multiple ribosomal proteins), as they may be co-regulated. Incorporate genes with distinct cellular functions for a more robust baseline [1].

Problem 2: High Technical Variation After Normalization

- Symptoms: Inconsistent results between biological replicates; high coefficient of variation (CV) after normalization.

- Causes: Inconsistency can stem from RNA degradation, minimal starting material, or pipetting errors. Furthermore, the normalization method itself may be ineffective at removing non-biological noise [22].

- Solutions:

- Check RNA Quality: Prior to reverse transcription, check RNA concentration and integrity. A 260/280 ratio outside the ideal 1.9–2.0 range can indicate contamination, and a smeared gel can indicate degradation [22].

- Consider Alternative Methods: For high-throughput qPCR profiling dozens of genes, data-driven normalization methods like Quantile Normalization or the NORMA-Gene algorithm can be more robust than standard housekeeping gene approaches [5] [21].

- Improve Pipetting Technique: Perform technical replicates and ensure proficiency to minimize pipetting errors [23] [22].

Problem 3: Inability to Reproduce Published Findings

- Symptoms: Your qPCR results do not match previously published data, even when using the same reference genes.

- Causes: A widespread reliance on the 2–ΔΔCT method often overlooks critical factors such as variations in amplification efficiency and reference gene stability between different experimental setups [9]. Furthermore, a lack of shared raw data and analysis code prevents proper evaluation [9].

- Solutions:

- Go Beyond 2–ΔΔCT: Consider using statistical methods like ANCOVA (Analysis of Covariance), which can offer greater statistical power and robustness by directly accounting for efficiency variations [9].

- Adhere to FAIR Principles: Share your raw qPCR fluorescence data and detailed analysis scripts. This allows others to evaluate potential biases and reproduce your findings accurately [9].

- Use Automated, Reproducible Tools: Leverage open-source analysis software like Auto-qPCR to create a systematic, error-minimized workflow from raw data to final analysis, reducing "user-dependent" variation [24].

Reference Gene Stability Across Conditions

The table below summarizes quantitative data from a study investigating reference gene stability in different mouse brain structures during ageing, illustrating that a gene stable in one context may be unstable in another [20].

Table 1: Stability of Common Reference Genes in Ageing Mouse Brain Structures P-values from ANOVA test for expression differences across ages; lower p-value indicates less stability.

| Gene | Cortex | Hippocampus | Striatum | Cerebellum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ppib | 0.0407 * | 0.2252 | 0.7391 | 0.5919 |

| Hmbs | 0.5114 | 0.0078 | 0.0344 * | 0.0047 |

| ActinB | 0.4707 | 0.0011 | 0.4552 | <0.0001 * |

| Sdha | 0.0017 | 0.0045 | 0.1322 | <0.0001 * |

| GAPDH | 0.0501 | 0.0279 * | 0.5062 | 0.0593 |

| Significance | p<0.05; * p<0.01; * p<0.001* |

Comparison of Normalization Methods

Different normalization strategies offer varying levels of effectiveness in reducing technical variability. The following table compares several common approaches.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of qPCR Normalization Methods

| Method | Principle | Best Use Case | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Reference Gene | Adjusts data based on one stably expressed gene | Quick, low-cost pilot studies; when a gene's stability is thoroughly validated in the specific system | Simplicity and low resource requirement | High risk of bias; many classic housekeeping genes (GAPDH, ACTB) are often unstable [20] [5] |

| Multiple Reference Genes | Uses a normalization factor from several stable genes (e.g., via GeNorm) | Most standard qPCR experiments; MIQE guideline recommendation [20] | More robust than single-gene; reduces impact of co-regulation | Requires upfront validation; consumes samples for extra assays [1] |

| Global Mean (GM) | Normalizes to the average Cq of all profiled genes | High-throughput studies profiling many genes (>55) [1] | Data-driven; no need for pre-selected reference genes | Requires a large number of genes; assumes most genes are not differentially expressed [1] |

| Quantile Normalization | Forces the distribution of expression values to be identical across all samples | High-throughput qPCR where samples are distributed across multiple plates [5] | Effectively removes plate-to-plate technical effects | Makes strong assumptions about the data distribution [5] |

| NORMA-Gene | Data-driven algorithm that estimates and reduces systematic bias per replicate | Studies with a limited number of target genes (as few as 5) [21] | Does not require reference genes; handles missing data well | Less known and adopted; performance depends on number of genes [21] |

Workflow: From Poor to Robust Normalization

The following diagram illustrates a robust workflow for avoiding the consequences of poor normalization, from experimental design to data analysis.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example(s) / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Reference Genes | Genes with invariant expression used as internal controls for normalization. | Genes like RPS5, RPL8, HMBS were identified as stable in canine GI tissue; stability must be validated for your system [1]. |

| qPCR Plates & Seals | Physical consumables for housing reactions. | Ensure plates are properly sealed to prevent evaporation, which causes inconsistent traces and poor replication [23]. |

| RNA Quality Assessment Tools | To verify RNA integrity before cDNA synthesis. | Spectrophotometer (for 260/280 ratio), agarose gel electrophoresis. Degraded RNA is a major source of irreproducible results [22]. |

| Stability Analysis Software | Algorithms to objectively rank candidate reference genes by stability. | GeNorm [1], NormFinder [1]. Integrated into software like QBase+ [20]. |

| Data-Driven Normalization Software | Tools that perform normalization without pre-defined reference genes. | qPCRNorm R package (Quantile Normalization) [5], NORMA-Gene Excel workbook [21], Auto-qPCR web app [24]. |

From Theory to Bench: Implementing Robust qPCR Normalization Strategies

What are housekeeping genes and why are they important for qPCR? Housekeeping genes, also known as reference or endogenous controls, are constitutively expressed genes that regulate basic and ubiquitous cellular functions essential for cellular existence [25] [26]. In quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR), these genes serve as critical internal controls to normalize gene expression data, correcting for variations in sample quantity, RNA quality, and technical efficiency across samples [27]. This normalization is mandatory for accurate interpretation of results, as it ensures that observed expression changes reflect true biological differences rather than technical artifacts [25].

What are the key criteria for an ideal reference gene? An ideal reference gene should demonstrate stable expression under all experimental conditions, cell types, developmental stages, and treatments being studied [26] [27]. While early definitions focused primarily on genes expressed in all tissues, current best practices require that potential reference genes also be expressed at a constant level across the specific conditions of the experiment [28]. The expression of a suitable reference gene cannot be influenced by the experimental conditions [29].

Validating Reference Genes: Experimental Protocols

Step-by-Step Validation Procedure

Before using reference genes in your study, they must be empirically validated. Follow this detailed protocol to test candidate gene stability:

Select Candidate Genes: Choose 3-10 potential reference genes from literature reviews or endogenous control panels. Include genes with different cellular functions to avoid co-regulation [30] [27]. The TaqMan endogenous control plate provides 32 stably expressed human genes for initial screening [27].

Prepare Representative Samples: Collect RNA samples across all experimental conditions, time points, and tissue types relevant to your study. Ensure consistent RNA purification methods across all samples [27].

Conduct Reverse Transcription: Convert equal amounts of RNA to cDNA using consistent methodology. In two-step RT-qPCR, use a mixture of random hexamers and oligo(dT) primers for comprehensive cDNA representation [31].

Perform qPCR Analysis: Amplify candidate genes across all sample types in at least triplicate reactions. Use the same volume of cDNA template for each reaction to maintain consistency [27].

Analyze Expression Stability: Calculate Ct values and assess variability using specialized algorithms. The most suitable candidate genes will show the least variation in Ct values (lowest standard deviation) across all tested conditions [27].

Workflow Diagram for Reference Gene Validation

Troubleshooting Common Issues

How many reference genes should I use for accurate normalization? The MIQE guidelines recommend using multiple reference genes rather than relying on a single gene [29]. The optimal number can be determined using the geNorm algorithm, which calculates a pairwise variation value (V) to determine whether adding another reference gene improves normalization stability [32]. Generally, including three validated reference genes provides significantly more reliable normalization than using one or two genes.

What should I do if my favorite housekeeping gene (GAPDH, ACTB) shows variable expression? Many commonly used housekeeping genes like GAPDH and ACTB show significant variability across different tissue types and experimental conditions [25] [27]. If your initial testing reveals instability in these classic reference genes:

- Expand your candidate panel to include less traditional housekeeping genes such as TBP, RPLP2, YWHAZ, or CYC1 [25].

- Use statistical algorithms like geNorm or NormFinder to identify the most stable genes for your specific experimental system [32] [30].

- Consider alternative genes from different functional pathways that may be more stable in your particular experimental context.

How do I handle tissue-specific or condition-specific reference gene selection? Gene expression stability is highly context-dependent, meaning a gene stable in one tissue or condition may be variable in another [25]. For example, wounded and unwounded tissues show contrasting housekeeping gene expression stability profiles [25]. To address this:

- Always validate reference genes specifically for your experimental conditions.

- Consult databases like NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus to check expression patterns of candidate genes in your tissue of interest [27].

- Consider that genes stably expressed in healthy tissues may show variability in disease states or after experimental manipulations.

What if my reference genes show high variability (Ct value differences >0.5)? High variability in Ct values (standard deviation >0.5 cycles between samples) indicates an inappropriate reference gene [27]. Address this by:

- Verifying RNA quality and cDNA synthesis consistency across samples.

- Testing additional candidate genes to identify more stable alternatives.

- Using statistical methods to identify genes with the lowest M-values (geNorm) or highest equivalence (network-based methods) [25] [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Reference Gene Validation

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzymes | Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV) RT, Avian Myeloblastosis Virus (AMV) RT | Converts RNA to cDNA; select enzymes with high thermal stability for RNA with secondary structure [31]. |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green, TaqMan assays | Provides fluorescence detection for quantification; TaqMan assays offer higher specificity through dual probes [25]. |

| Reference Gene Assays | TaqMan Endogenous Control Panel (32 human genes) | Pre-optimized assays for screening potential reference genes [27]. |

| Primer Options | Oligo(dT), random hexamers, gene-specific primers | cDNA synthesis priming; mixture of random hexamers and oligo(dT) recommended for comprehensive coverage [31]. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | RNAlater | Preserves RNA integrity in tissues prior to extraction [25]. |

Statistical Analysis and Data Interpretation

Several statistical algorithms are available to assess reference gene stability:

- geNorm: Determines the most stable reference genes from a set of candidates and calculates the optimal number of genes needed for accurate normalization [32]. The algorithm computes an M-value representing expression stability, with lower M-values indicating greater stability [25].

- NormFinder: Another popular algorithm that ranks candidate genes by stability, though it may produce different rankings than geNorm [30].

- Network-based equivalence tests: A newer method that uses equivalence tests on expression ratios to select genes proven to be stable with controlled statistical error [30].

Decision Framework for Normalization Strategy

Advanced Applications and Considerations

How do I approach reference gene selection for specialized applications like cancer research or developmental studies? In specialized contexts like cancer biology, where gene expression patterns are significantly altered, the use of multiple controls is essential [27]. Studies classifying tumors into subtypes based on gene expression patterns typically select 2-3 optimal control genes from a larger panel of 11 or more candidates [27]. Similarly, in developmental studies with multiple stages, validate reference genes specifically for each developmental time point.

What are the emerging trends and computational tools for reference gene selection? Recent approaches include:

- Data-driven normalization: Methods like quantile normalization that directly correct for technical variation without presuming specific housekeeping genes, especially useful when standard reference genes are regulated by experimental conditions [5].

- Gini coefficient analysis: A statistical measure quantifying inequality in expression across samples, with lower values indicating more stable expression [26].

- Global mean normalization: Particularly useful for normalizing data from large, unbiased gene sets such as miRNA expression profiles [32].

Table 2: Common Reference Genes and Their Cellular Functions

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Primary Cellular Function | Stability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Glycolysis, dehydrogenase activity | Highly variable across tissues; requires validation [25] [27] |

| ACTB | Actin, beta | Cytoskeleton structure | Commonly used but often variable; shorter introns/exons [25] [28] |

| B2M | Beta-2-microglobulin | Histocompatibility complex antigen | Frequently used but stability varies by condition [25] |

| TBP | TATA box binding protein | Transcription initiation | Often shows high stability in validation studies [25] |

| RPLP2 | Ribosomal protein large P2 | Translation, ribosomal function | Good candidate with stable expression in many systems [25] |

| YWHAZ | Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase activation protein | Signal transduction | Validated as stable in multiple models [25] [28] |

| 18S | 18S ribosomal RNA | Ribosomal RNA component | Highly expressed; may require dilution in reactions [27] |

Accurate normalization is a foundational step in reliable quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) gene expression analysis. Technical variations introduced during sample collection, RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and PCR amplification can significantly obscure true biological differences [3] [1]. Normalization controls for this technical noise, ensuring that observed expression changes reflect experimental conditions rather than procedural artifacts. The use of internal reference genes (RGs), or housekeeping genes (HKGs), is the most common normalization strategy. These genes, involved in basic cellular maintenance, are presumed to be stably expressed across various tissues and conditions. However, a growing body of evidence confirms that no single reference gene is universally stable; their expression can vary considerably depending on the species, tissue, experimental treatment, and even pathological state [33] [1] [34]. The inappropriate selection of an unstable reference gene can lead to inaccurate data, misleading fold-change calculations, and incorrect biological conclusions [3] [35].

To address this challenge, algorithm-assisted selection methods have been developed to systematically identify the most stable reference genes for a specific experimental setup. This technical support document, framed within a thesis on normalization methods for qPCR data research, provides a detailed guide to utilizing three cornerstone algorithms: geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper. It offers troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigate common pitfalls and implement these powerful tools effectively in their experiments.

Understanding the Algorithms: Principles and Workflow

The three algorithms, geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper, employ distinct mathematical approaches to rank candidate reference genes based on their expression stability. Using them in concert provides a robust, consensus-based selection.

Algorithm Comparison and Workflow

The table below summarizes the core principles, outputs, and key considerations for each algorithm.

Table 1: Comparison of geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper Algorithms

| Algorithm | Core Principle | Primary Output | Key Strength | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| geNorm [36] | Pairwise comparison of variation between all candidate genes. | M-value: Lower M-value indicates higher stability. Pairwise variation (V): Determines optimal number of RGs (V<0.15 is typical cutoff) [33]. | Intuitively identifies the best pair of genes; recommends the optimal number of RGs. | Tends to select co-regulated genes; cannot rank a single best gene [37]. |

| NormFinder [1] | Model-based approach estimating intra- and inter-group variation. | Stability value: Lower value indicates higher stability. | Accounts for sample subgroups within the experiment; less likely to select co-regulated genes. | Requires pre-defined group structure (e.g., control vs. treatment) for best results. |

| BestKeeper [36] | Correlates each candidate gene's Cq values to a synthetic index (geometric mean of all candidates). | Standard Deviation (SD) & Coefficient of Variation (CV): Lower values indicate higher stability. Correlation coefficient (r) with the BestKeeper Index. | Provides direct measures of expression variability (SD/CV) based on raw Cq values. | Relies on raw Cq values and assumes high PCR efficiency; can be sensitive to outliers [37]. |

To integrate the rankings from these algorithms, the tool RefFinder is often used. It employs a geometric mean to aggregate results from geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the comparative ΔCt method, providing a comprehensive stability ranking [33] [38].

The following diagram illustrates the typical experimental workflow for algorithm-assisted reference gene selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful implementation of algorithm-assisted selection requires careful planning and the right tools. The table below lists essential materials and software used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Reference Gene Validation

| Category / Item | Specific Examples from Literature | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | Trizol reagent [3] [35], RNeasy Plant Mini Kit [33] | Isolation of high-quality, intact total RNA from biological samples. |

| DNase Treatment | RQ1 RNase-Free DNase [3] | Removal of genomic DNA contamination from RNA samples. |

| cDNA Synthesis | Maxima H Minus Double-Stranded cDNA Synthesis Kit [33] | Reverse transcription of RNA into stable complementary DNA (cDNA). |

| qPCR Master Mix | Not specified in results, but essential. | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, and dyes for efficient amplification. |

| Stability Algorithms | geNorm [36], NormFinder [1], BestKeeper [36] | Excel-based software to calculate gene expression stability. |

| Comprehensive Ranking Tool | RefFinder [33] [38] | Web tool that integrates results from multiple algorithms for a final ranking. |

| (Z)-7-Dodecen-1-ol | (Z)-7-Dodecen-1-ol, CAS:20056-92-2, MF:C12H24O, MW:184.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Bombykol | Bombykol | Bombykol, the first characterized insect sex pheromone. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. Study olfaction and pest control. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't I just use a single, well-known reference gene like GAPDH or ACTB?

A: It is a common misconception that classic HKGs are universally stable. Numerous studies demonstrate that their expression can vary significantly with experimental conditions. For instance, in canine gastrointestinal tissue, ACTB was less stable than ribosomal proteins [1]. In Vigna mungo under stress, TUB was the least stable gene [33]. Using an unvalidated single gene risks introducing substantial bias into your data [3] [34].

Q2: What is the minimum number of candidate genes I should test? A: The MIQE guidelines recommend using at least two validated reference genes [3]. In practice, you should start with a panel of 3 to 10 candidate genes selected from the literature relevant to your species, tissue, and experimental treatment [33] [38]. Testing too few genes may not provide a stable normalization factor.

Q3: My results from geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper are slightly different. Which one should I trust? A: Discrepancies are common and expected due to their different computational principles [34] [37]. The most robust approach is to use an integrated tool like RefFinder, which generates a comprehensive ranking based on all three methods [33] [38]. Alternatively, you can manually compare the outputs and select genes that consistently rank in the top tier across all algorithms.

Q4: I am profiling a large number of genes. Are there alternative normalization methods? A: Yes. When profiling tens to hundreds of genes, the Global Mean (GM) method can be a powerful alternative. This method uses the geometric mean of the expression of all reliably detected genes as the normalization factor. One study in canine tissues found the GM method outperformed traditional reference gene normalization when more than 55 genes were profiled [1]. Another algorithm-based method, NORMA-Gene, which requires data from at least five genes and uses least-squares regression, has been shown to reduce variance effectively and requires fewer resources than traditional reference gene validation [3].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High variation in Cq values for all candidate genes.

- Potential Cause 1: Poor RNA quality or inconsistent cDNA synthesis.

- Solution: Check RNA integrity (e.g., RIN > 8.0) using an instrument like a Bioanalyzer. Standardize RNA quantity and quality input for all reverse transcription reactions [3] [33].

- Potential Cause 2: Inefficient or variable PCR amplification.

- Solution: Check primer efficiencies; they should be between 90-110% and consistent across assays. Optimize qPCR conditions to ensure specific amplification with a single peak in the melt curve [3] [35].

Problem: geNorm recommends too many genes (high V-value).

- Potential Cause: No set of genes in your panel is sufficiently stable, or the experimental conditions profoundly affect cellular physiology.

- Solution: Re-evaluate your candidate gene panel. Include genes from different functional classes (e.g., cytoskeletal, ribosomal, metabolic) to avoid co-regulation. Consider using an alternative normalization strategy like NORMA-Gene or the Global Mean method if applicable [3] [1].

Problem: Discrepancy between algorithm rankings and RefFinder output.

- Potential Cause: RefFinder uses raw Cq values as input and may not account for differences in PCR amplification efficiency, unlike the original software packages. A study demonstrated that when raw data were reanalyzed assuming 100% efficiency, the original software outputs aligned with RefFinder [37].

- Solution: Be aware of this limitation. It is best practice to use the original software with efficiency-corrected Cq values for the most accurate results. Use RefFinder as a convenient tool for a consolidated, but potentially efficiency-biased, overview.

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Methodology

The following protocol is synthesized from multiple studies validating reference genes [3] [33] [34].

Objective: To identify and validate the most stable reference genes for normalizing qPCR data in a specific experimental system.

Step 1: Candidate Gene Selection

- Action: Select 5-10 candidate reference genes from the scientific literature relevant to your species, tissue, and experimental context.

- Rationale: Genes commonly stable in one system (e.g.,

GAPDHin some plants [38]) may be unstable in another (e.g.,GAPDHin canine intestine [1]). A diverse panel increases the likelihood of finding stable genes.

Step 2: Sample Preparation and qPCR

- Action:

- Subject organisms or cells to all planned experimental conditions (e.g., control, treatment A, treatment B).

- Harvest tissues/cells and extract total RNA using a reliable method (e.g., column-based kits or Trizol). Treat with DNase.

- Quantify RNA and check purity (A260/280 ratio ~2.0). Synthesize cDNA using a high-quality reverse transcriptase kit.

- Run qPCR for all candidate genes on all samples. Include no-template controls. Perform technical replicates.

- Critical Note: Ensure PCR efficiencies are optimized and consistent (90-110%) for all primer pairs, as this is a critical input for geNorm and NormFinder [37].

Step 3: Data Pre-processing and Analysis

- Action:

- Record Cq values. Calculate PCR efficiencies for each gene if not already known.

- Input the Cq values and efficiency data into geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper according to the software manuals.

- Software Note: BestKeeper works with raw Cq values, while geNorm and NormFinder can utilize efficiency-corrected quantities [37].

Step 4: Interpretation and Validation

- Action:

- From geNorm, note the M-values and the point where the pairwise variation (Vn/n+1) falls below 0.15, indicating the sufficient number of reference genes.

- From NormFinder, rank genes by their stability value.

- From BestKeeper, rank genes by their standard deviation (SD) and correlation coefficient (r) with the index.

- Compile a final ranked list. Select the top 2-3 most stable genes for normalization.

- Validation: Test the selected genes by normalizing a target gene with known or expected expression behavior. Compare the results when normalizing with the most versus the least stable gene; a significant difference confirms the importance of proper selection [38].

In quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) research, normalization is not merely a data processing step; it is a fundamental prerequisite for obtaining biologically accurate and reproducible results. The process aims to eliminate technical variability introduced during sample collection, RNA extraction, and cDNA synthesis, thereby ensuring that the final analysis reflects true biological variation. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the optimal normalization strategy is critical for validating RNA sequencing results, quantifying biomarker expression, and making pivotal decisions in the drug development pipeline. While the use of internal reference genes (RGs) has been the traditional cornerstone of qPCR normalization, the Global Mean (GM) normalization method has emerged as a powerful and often superior alternative, particularly in studies profiling a large number of genes. This guide provides a technical deep-dive into implementing GM normalization, complete with troubleshooting FAQs and validated experimental protocols.

What is Global Mean Normalization?

Global Mean (GM) normalization is a method where the expression level of a target gene is normalized against the geometric mean of the expression levels of a large number of genes profiled across all samples in the experiment [1]. Unlike traditional reference gene methods that rely on a few stably expressed "housekeeping" genes, GM normalization uses the bulk expression of the transcriptome as its baseline. This approach is conventionally used in gene expression microarrays and miRNA profiling and has proven to be a valuable alternative for high-throughput qPCR studies [1].

Key Advantages and Considerations

- Reduces Bias from Co-regulated Genes: Using a large number of genes minimizes the risk of bias that can occur when using a small set of reference genes that might be co-regulated under specific experimental conditions [1].

- No Need for Pre-Validation: The method eliminates the resource-intensive process of validating candidate reference genes for every new experimental condition.

- Requires a Sufficient Number of Genes: Its performance is dependent on profiling a sufficient number of genes to accurately represent the global expression baseline.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: When is GM Normalization the Most Appropriate Method?

Answer: GM normalization is most appropriate and outperforms traditional methods when your qPCR experiment profiles a large number of genes.

- Strong Recommendation: A 2025 study on canine gastrointestinal tissues explicitly advises the implementation of the GM method "when a set greater than 55 genes is profiled" [1]. The study systematically compared six normalization strategies and found GM normalization to be the best-performing method in reducing the coefficient of variation (CV) across samples.

- Weaker Performance with Small Gene Sets: The stability of the global mean is dependent on the number of genes used. With smaller gene sets (e.g., fewer than 10-20 genes), the mean can be easily skewed by the high variation of a few genes, making traditional stable reference genes a more reliable choice [1].

FAQ 2: How Does GM Normalization Compare to Traditional Reference Genes?

Answer: Direct comparative studies have demonstrated that GM normalization can significantly reduce technical variation compared to using even multiple, validated reference genes.

The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison from a study that evaluated different normalization strategies on 81 genes in canine intestinal tissues [1].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Normalization Methods in a qPCR Study

| Normalization Method | Number of Genes Used for Normalization | Reported Performance (Mean Coefficient of Variation) |

|---|---|---|

| Global Mean (GM) | 81 (all profiled genes) | Lowest observed across all tissues and conditions [1] |

| Most Stable RGs | 5 | Higher variability than GM method |

| Most Stable RGs | 4 | Higher variability than GM method |

| Most Stable RGs | 3 | Higher variability than GM method |

| Most Stable RGs | 2 | Higher variability than GM method |

| Most Stable RGs | 1 | Highest variability among the tested methods |

FAQ 3: My Global Mean is Unstable. What Could Be the Cause?

Answer: An unstable global mean typically indicates an issue with the input data or the experimental design.

- Insufficient Number of Genes: This is the most common cause. Re-evaluate your panel size. If you are profiling fewer than 50 genes, consider switching to a validated panel of reference genes or expanding your gene panel [1].

- Poor RNA Quality or Technical Artifacts: The GM method assumes that the overall transcriptome profile is consistent. Degraded RNA or technical issues during reverse transcription or qPCR (e.g., inhibitors, pipetting errors) can create systematic biases that affect the global mean. Always check RNA integrity numbers (RIN) and inspect amplification curves for anomalies.

- Extreme Biological Outliers: If a sample is an extreme biological outlier (e.g., a severely diseased tissue vs. healthy controls), its global expression profile might be fundamentally different. In such cases, it is crucial to ensure that the gene panel is representative and not biased towards a specific metabolic pathway.

FAQ 4: Are There Algorithmic Alternatives to GM Normalization?

Answer: Yes, other algorithm-based normalization methods exist that also do not require stable reference genes. A prominent example is NORMA-Gene.

- How it works: NORMA-Gene uses a least squares regression model on the expression data of at least five genes to calculate a normalization factor that minimizes variation across samples [3].

- Demonstrated Performance: A 2025 study on sheep liver found that NORMA-Gene was better at reducing the variance in the expression of target genes than normalization using the top three validated reference genes [3].

- Practical Benefit: Like GM normalization, it saves resources by eliminating the need for extensive reference gene validation [3].

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol for GM Normalization

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps for implementing GM normalization in a qPCR study, from experimental design to data analysis.

Detailed Protocol

Experimental Design & Gene Profiling:

- Design your qPCR assay to profile a large number of genes. As per recent evidence, a panel of more than 55 genes is recommended for GM normalization to be effective [1].

- Include a diverse set of genes representing various biological functions to ensure the global mean is a robust representation of the transcriptome.

Data Curation (Critical Step):

- Before normalization, rigorously curate your qPCR data. Exclude assays with poor PCR efficiency (e.g., outside 90-110%) or non-specific amplification as judged by melt curve analysis [1].

- Identify and handle any technical outliers. A published study excluded over 15% of initially profiled genes due to poor efficiency or low signal before final analysis [1].

Calculation of Global Mean and Normalization:

- For each sample, calculate the geometric mean of the Cq (or Ct) values for all reliably profiled genes. The geometric mean is used because it is less sensitive to extreme values than the arithmetic mean.

- The normalization factor (NF) for each sample is this global mean value.

NF_sample = geometric_mean(Cq_g1, Cq_g2, ..., Cq_gn) - Calculate the normalized expression for each target gene (ΔCq):

ΔCq_target = Cq_target - NF_sample

Downstream Analysis:

- Proceed with standard relative quantification methods, using the ΔCq values for statistical analysis and calculation of fold-changes (e.g., 2^(-ΔΔCq)) or using more robust statistical models like ANCOVA [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful implementation of GM normalization relies on high-quality starting materials and reagents. The following table lists key solutions required for the featured methodology.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR with GM Normalization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Key Considerations for GM Normalization |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality RNA Isolation Kit | To extract intact, pure total RNA from biological samples. | Critical. RNA integrity is paramount, as degradation can skew the global expression profile. Use systems like QIAzol Lysis Reagent [3]. |

| RT-qPCR Master Mix | A ready-to-use mixture containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and salts for amplification. | Choose a robust mix suitable for high-throughput platforms. Verify that it provides consistent efficiency across all assays in your large panel. |

| High-Throughput qPCR Platform | A system capable of profiling 96 or more genes simultaneously. | Essential for efficiently running the large gene panels required for a stable GM. Enables consistent thermal cycling across all reactions [1]. |

| Primer Assays | Sequence-specific primers for each gene in the panel. | Design or select primers with high efficiency and specificity. Validate using melting curves. Plan a panel that exceeds the minimum gene number threshold [1] [3]. |

| Data Analysis Software | Software capable of handling Cq data and performing geometric mean calculations. | Ensure the software (e.g., R, Python scripts, specialized qPCR analysis suites) can efficiently compute the global mean from dozens to hundreds of genes per sample. |

| N-Benzylacetamide | N-Benzylacetamide, CAS:588-46-5, MF:C9H11NO, MW:149.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3,3-Dimethylglutaric acid | 3,3-Dimethylglutaric acid, CAS:4839-46-7, MF:C7H12O4, MW:160.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Decision Workflow: Choosing Your Normalization Strategy

The flowchart below provides a logical pathway to help researchers decide whether GM normalization is the optimal choice for their specific experimental setup.

NORMA-Gene is a data-driven normalization method for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) that eliminates the need for traditional reference genes. This algorithm-only approach uses the expression data of the target genes themselves to calculate a normalization factor for each replicate, effectively reducing technical variance introduced during sample processing. The method is based on a least squares regression applied to log-transformed data to estimate and correct for systematic, between-replicate bias [39].

Key Advantages of NORMA-Gene

| Advantage | Description |

|---|---|

| Eliminates Reference Gene Validation | No need to identify and validate stably expressed reference genes, saving time and resources [39] [3]. |

| Robust Performance | Demonstrated to reduce technical variance more effectively than reference gene normalization in multiple independent studies [39] [3] [1]. |

| Handles Missing Data Efficiently | Can normalize samples even with missing data points, unlike reference gene methods which may lead to the loss of an entire replicate [39]. |

| Applicable to Small Gene Sets | Valid for data-sets containing as few as five target genes [39]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing NORMA-Gene

The following workflow outlines the core steps for normalizing qPCR data using the NORMA-Gene method.

Detailed Methodology

The NORMA-Gene algorithm operates on the log-transformed expression data within each experimental treatment group. For a treatment where n genes are measured across m replicates, the key calculation is the normalization factor for each replicate, known as the bias coefficient (aj) [39]:

- Calculate Mean Gene Expression: For each gene

iin the data-set, calculate the mean expression value (Mi) across all replicates within the treatment. - Calculate the Bias Coefficient: The normalization factor for each replicate

jis calculated as: > aj = (1/Nj) * Σ [ logXji - Mi ] Where:- Nj is the number of genes measured for replicate

j. - logXji is the log-transformed expression value for gene

iin replicatej. - Mi is the mean expression value for gene

iacross all replicates.

- Nj is the number of genes measured for replicate

- Apply Normalization: The coefficient aj is used to normalize all gene expression values within the corresponding replicate

j[39].

Performance and Validation

NORMA-Gene's performance has been benchmarked against traditional reference gene normalization in both artificial and real qPCR data-sets. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from these studies.

Comparative Performance of Normalization Methods

| Study Model | Key Finding | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Data-Sets [39] | Precision of normalization at different bias-to-variation ratios. | NORMA-Gene yielded more precise results under a large range of tested parameters. |

| Sheep Liver [3] | Variance reduction in target genes (CAT, GPX1, etc.). | NORMA-Gene was better at reducing variance than normalization using 3 reference genes (HPRT1, HSP90AA1, B2M). |

| Canine Intestinal Tissue [1] | Coefficient of variation (CV) after normalization with different strategies. | The global mean method (similar principle) showed the lowest mean CV across all tissues and conditions. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and performance outcome when choosing between normalization methods, as demonstrated in recent research.

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the minimum number of target genes required for NORMA-Gene? NORMA-Gene is valid for data-sets containing as few as five target genes [39]. The precision of the normalization improves as more genes are included in the data-set.

How does NORMA-Gene handle missing data points? The algorithm is very flexible and can proceed with missing data. It is not required that the same set of genes is available in all replicates within a treatment. Normalization can be performed as long as a minimum number of data points (five or more) is available within a replicate across the genes [39].

Can NORMA-Gene be used in studies with a large number of genes? Yes. While originally demonstrated for smaller sets, the underlying principle—using a global measure of gene expression for normalization—is also applicable and often superior in larger-scale gene profiling studies [1].

What are the main practical advantages for a research setting? The primary advantages are resource efficiency and robustness. NORMA-Gene eliminates the time and cost associated with selecting, validating, and running additional assays for reference genes. It also prevents invalid conclusions that can arise from using unsuitable, unvalidated reference genes [39] [3].

Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variance after normalization. | Underlying technical errors or outliers in the raw qPCR data. | Perform careful quality control (e.g., verify PCR efficiencies, inspect melting curves) prior to normalization, as the least squares method is non-robust to outliers [39]. |

| Limited number of target genes. | Experimental design focuses on a small gene panel. | Ensure you have at least five target genes. If possible, include more genes to improve the precision of the normalization [39]. |

| Uncertainty in results. | Lack of familiarity with data-driven normalization. | Compare normalized results with those from a traditional method if reference gene data is available, to build confidence in the algorithm [3]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials required for a typical qPCR experiment where NORMA-Gene normalization can be applied.

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| NORMA-Gene Excel Workbook | A macro-based workbook (freely available from the original authors) that automates all normalization calculations upon import of raw expression data [39]. |

| qPCR Instrument | Platform for performing real-time quantitative PCR, such as those from Bio-Rad, Thermo Fisher, or Roche. |

| RNA Extraction Kit | For isolating high-quality total RNA from biological samples (e.g., QIAzol Lysis Reagent) [3]. |

| DNase Treatment Kit | To remove genomic DNA contamination from RNA samples prior to reverse transcription (e.g., RQ1 RNase-Free DNase) [3]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase & Reagents | For synthesizing complementary DNA (cDNA) from the purified RNA template. |

| qPCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, salts, and optimized buffer for efficient amplification. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Validated primer pairs for each target gene, designed to be intron-spanning and have high amplification efficiency [3]. |