Reverse Transcription Optimization for qPCR: A Complete Guide to Enhance Sensitivity, Reproducibility, and Data Reliability

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing reverse transcription (RT) for quantitative PCR (qPCR).

Reverse Transcription Optimization for qPCR: A Complete Guide to Enhance Sensitivity, Reproducibility, and Data Reliability

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing reverse transcription (RT) for quantitative PCR (qPCR). Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it details how proper RT optimization is critical for accurate gene expression analysis, reliable diagnostic assay development, and robust biomarker discovery. The content addresses key challenges including RNA integrity, primer selection, enzyme choice, and experimental design, while emphasizing adherence to MIQE guidelines to ensure data reproducibility and translational validity in biomedical research.

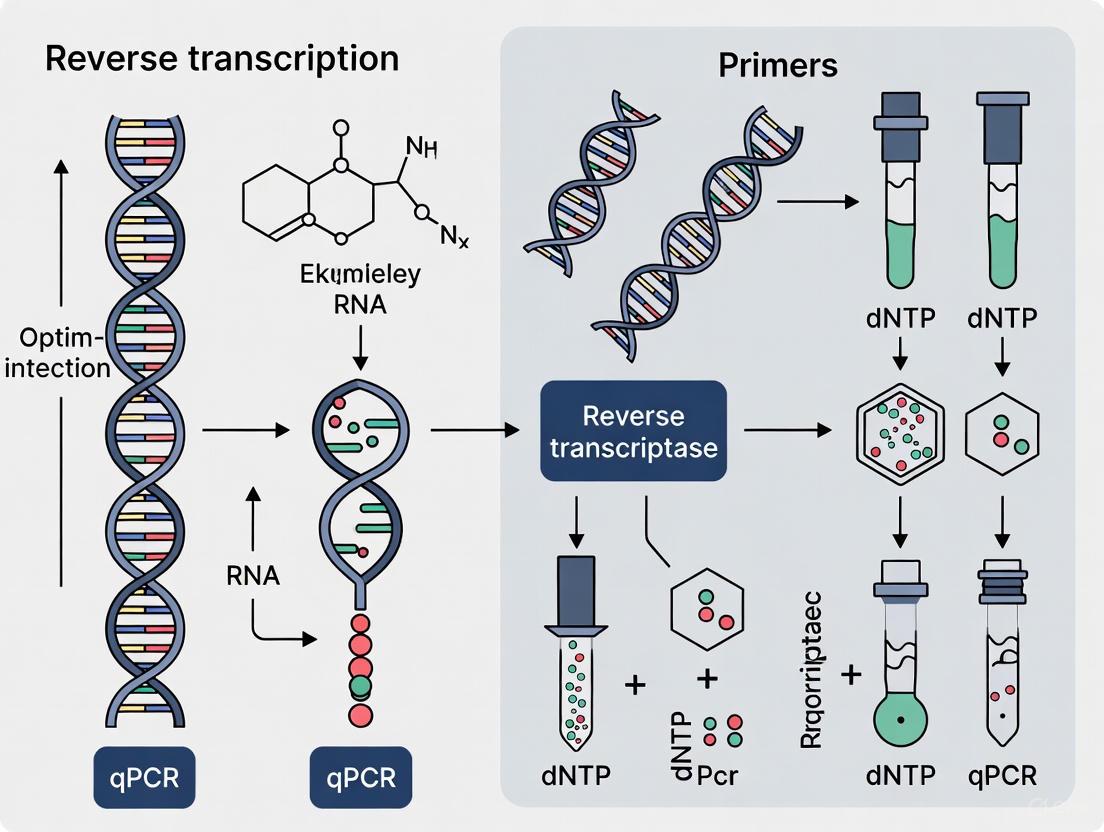

Understanding Reverse Transcription: The Critical First Step in Reliable qPCR

The Role of Reverse Transcription in Accurate Gene Quantification

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) is the gold standard technique for mRNA quantification, combining the sensitivity of PCR with the ability to quantify nucleic acids [1] [2]. This method allows researchers to detect rare transcripts and measure small variations in gene expression, making it indispensable for gene expression profiling, biomarker discovery, and validating results from high-throughput genomic studies [2] [3]. The accuracy of RT-qPCR, however, is entirely dependent on the initial reverse transcription step that converts RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) [4]. This conversion process introduces multiple technical variables that, if not properly controlled, can compromise data integrity and lead to misleading biological conclusions [3]. Within the context of a broader thesis on optimization strategies for qPCR research, this application note examines the critical role of reverse transcription in ensuring accurate gene quantification, providing detailed protocols and analytical frameworks to enhance experimental reproducibility and data reliability for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Critical Factors Influencing Reverse Transcription Fidelity

The reverse transcription process is a pivotal source of variability in RT-qPCR experiments, with several factors significantly impacting the accuracy of gene expression measurements.

RNA Integrity and Quality Control

RNA integrity is a fundamental prerequisite for accurate gene quantification. Degraded RNA templates can introduce substantial errors in expression measurements, with studies demonstrating that RNA degradation could introduce up to 100% error in gene expression measurements when data were normalized solely to total RNA concentration [1]. The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) provides a standardized metric for assessing RNA quality, with values ranging from 10 (intact) to 1 (fully degraded). Research has established a linear relationship between RIN values and expression ratios, with lower RIN values corresponding to significantly reduced detection of transcript levels [1]. The table below quantifies the maximum observed error in gene expression measurements across different RIN value categories.

Table 1: Impact of RNA Integrity on Gene Expression Measurement Error

| RIN Value Range | Maximum Observed Error (%) | Minimum Expression Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| RIN ≥ 8 | 47% | 0.68 |

| 7 ≤ RIN < 8 | 75% | 0.57 |

| 6 ≤ RIN < 7 | 92% | 0.52 |

| 5 ≤ RIN < 6 | 104% | 0.49 |

| RIN = 4.7 | 108% | 0.48 |

To compensate for variations in RNA integrity, researchers have developed corrective algorithms that incorporate RNA quality metrics into normalization strategies. This approach has been shown to reduce the average error in quantitative measurements to approximately 8%, significantly improving the reliability of sample comparisons, particularly in clinical biopsies where RNA degradation is common [1].

Reverse Transcriptase Selection and Properties

The choice of reverse transcriptase enzyme profoundly influences cDNA synthesis efficiency and fidelity. Key enzymatic properties to consider include:

- Thermal stability: Enzymes with higher thermal stability (e.g., M-MLV RT variants) can function efficiently at elevated temperatures (42-55°C), facilitating the reverse transcription of RNA templates with complex secondary structures [5] [4].

- RNase H activity: This inherent activity degrades the RNA strand in RNA-DNA hybrids following transcription. While excessive RNase H activity can result in truncated cDNA transcripts, controlled activity can enhance qPCR efficiency by melting RNA-DNA duplexes during initial PCR cycles [5] [4].

- Processivity: High-processivity enzymes synthesize longer cDNA fragments without dissociating from the template, providing more complete representation of the target transcript [6].

Modern reverse transcriptases engineered for improved performance often feature reduced RNase H activity coupled with enhanced thermal stability, offering superior cDNA yield and representation across diverse RNA templates [5] [6].

Primer Selection for cDNA Synthesis

The priming strategy employed during reverse transcription determines which RNA species are converted to cDNA and can introduce substantial bias in downstream quantification. The three primary priming approaches each offer distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 2: Comparison of Priming Strategies for Reverse Transcription

| Primer Type | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) | Binds to poly(A) tail of mRNA | Generates full-length cDNA from polyadenylated transcripts; minimizes ribosomal RNA background | 3' bias in cDNA synthesis; inefficient for degraded RNA or non-poly(A) transcripts |

| Random Primers | Hexamers or nonamers bind at multiple points along all RNA transcripts | Comprehensive coverage of all RNA species; effective for degraded RNA and transcripts with secondary structure | Generates truncated cDNAs; can prime ribosomal RNA, diluting mRNA signal |

| Gene-Specific Primers | Designed to complement specific target sequences | Maximum sensitivity for specific targets; ideal for one-step RT-qPCR protocols | Only reverse transcribes predetermined targets; not suitable for multiple targets from single reaction |

For two-step RT-qPCR applications where analyzing multiple targets from a single cDNA synthesis reaction is desirable, a mixed priming approach using both oligo(dT) and random primers often provides the optimal balance, mitigating the 3' bias associated with oligo(dT) priming while maintaining focus on mRNA targets [5] [7].

Optimized Protocols for Accurate Gene Quantification

Two-Step RT-qPCR with Integrity Correction

This optimized protocol incorporates quality control measures and normalization strategies to account for RNA integrity variations, making it particularly suitable for analyzing clinical samples with potentially compromised RNA quality.

Protocol: Two-Step RT-qPCR with RNA Integrity Correction

Step 1: RNA Quality Assessment and Normalization

- Quantify RNA concentration using a tray cell spectrophotometer system to ensure accurate measurement [1].

- Assess RNA integrity using microfluidic capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer) to determine RIN values [1].

- Normalize input RNA amounts based on both concentration and integrity metrics, using the corrective algorithm:

Normalized Amount = (Measured Concentration × RIN Correction Factor)[1].

Step 2: Reverse Transcription with Controls

- Prepare RT reaction mixture:

- RNA template (1-1000 ng) in nuclease-free water

- Reverse transcription primers (2.5 μM oligo(dT), 50 ng/μL random primers, or 0.2 μM gene-specific primers)

- dNTP mix (1 mM each)

- RNase inhibitor (20 U)

- Reverse transcriptase (200 U)

- Appropriate reaction buffer with MgClâ‚‚ (final concentration 2.5-5.0 mM)

- Incubate reactions:

- Primer annealing: 65°C for 5 minutes

- cDNA synthesis: 50°C for 30-60 minutes

- Enzyme inactivation: 85°C for 5 minutes

- Include minus reverse transcriptase controls (-RT) to detect genomic DNA contamination [5].

Step 3: Quantitative PCR Amplification

- Prepare qPCR master mix:

- cDNA template (diluted 1:5 to 1:20)

- Forward and reverse primers (0.1-0.5 μM each)

- DNA polymerase (0.5-1.25 U)

- dNTPs (200 μM each)

- MgClâ‚‚ (1.5-4.0 mM)

- Fluorescent detection system (SYBR Green or TaqMan probe)

- Perform thermal cycling:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15-30 seconds

- Annealing: 55-65°C for 15-30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 15-30 seconds

- Fluorescence acquisition at each cycle during extension phase

Step 4: Data Analysis with Integrity Normalization

- Calculate Ct values for target and reference genes

- Apply the ΔΔCt method for relative quantification [2]

- Incorporate RNA integrity correction factor:

Normalized Expression = 2^(-ΔΔCt) × RIN Correction Factor[1]

One-Step RT-qPCR for High-Throughput Applications

One-step RT-qPCR offers advantages for processing large sample numbers while minimizing handling steps and contamination risk.

Protocol: One-Step RT-qPCR for High-Throughput Applications

Step 1: Reaction Setup

- Prepare master mix containing:

- One-step RT-qPCR enzyme blend (reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase)

- Reaction buffer with optimized salt composition

- dNTP mix (0.4-1.0 mM each)

- Gene-specific primers (0.2-0.6 μM each)

- Fluorescent probe or dye

- RNA template (1-100 ng)

- Aliquot reactions into qPCR plate

Step 2: Combined Reverse Transcription and Amplification

- Perform thermal cycling with integrated protocol:

- Reverse transcription: 50°C for 10-30 minutes

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes

- 40-45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 10-15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 30-60 seconds with fluorescence acquisition

Step 3: Data Analysis

- Determine Ct values directly from amplification curves

- Calculate relative expression using standard curves or comparative Ct method [2] [7]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of RT-qPCR requires careful selection of reagents and appropriate controls to ensure data accuracy and reproducibility.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Reverse Transcription and qPCR

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptases | M-MLV RT, AMV RT, engineered RT variants | Catalyzes cDNA synthesis from RNA templates; selection based on thermal stability, processivity, and RNase H activity [5] [4] |

| RNA Quality Tools | Microfluidic capillary electrophoresis, RIN algorithm | Assesses RNA integrity; critical for normalization of degraded samples [1] |

| Priming Systems | Oligo(dT)â‚₈, random hexamers, gene-specific primers | Initiates cDNA synthesis; choice depends on target specificity and RNA quality [5] [7] |

| Fluorescent Detection | SYBR Green, TaqMan probes, molecular beacons | Enables real-time quantification; SYBR Green for cost-effectiveness, TaqMan for specificity [2] [4] |

| Reference Genes | GAPDH, ACTB, 18S rRNA, HPRT1, RPLP0 | Normalizes technical and biological variation; requires validation for specific sample types [1] [2] |

| Quality Controls | Minus RT control, exogenous RNA controls, inter-plate calibrators | Detects DNA contamination, monitors reaction efficiency, ensures inter-assay reproducibility [5] [3] |

| p32 Inhibitor M36 | p32 Inhibitor M36, MF:C23H28N8O2, MW:448.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| IK1 inhibitor PA-6 | IK1 inhibitor PA-6, MF:C31H32N4O2, MW:492.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting and Quality Assurance

Implementing robust quality control measures is essential for generating reliable gene expression data, particularly when working with challenging sample types.

Addressing Reverse Transcription Variability

The reverse transcription step introduces significantly more variability than the PCR amplification phase [3]. To minimize this variability:

- Include technical replicates at the reverse transcription stage, not just during PCR amplification [3]

- Use exogenous RNA controls (e.g., CAB mRNA) added to the RT reaction to monitor conversion efficiency across samples [1]

- Demonstrate reverse transcriptase linear dynamic range empirically for each enzyme and priming system [3]

- Maintain consistent reaction conditions (temperature, incubation times, buffer composition) across all samples in a study

Normalization Strategies for Accurate Quantification

Appropriate normalization is critical for meaningful biological interpretation of RT-qPCR data. A multi-factorial normalization approach is recommended:

- RNA integrity-based normalization: Implement corrective algorithms that account for RNA quality differences between samples [1]

- Reference gene normalization: Select and validate multiple reference genes with stable expression under experimental conditions [1] [2]

- Total RNA input normalization: Precisely quantify RNA concentration using fluorescence-based methods [1]

Each normalization strategy addresses different sources of variability, and combining these approaches provides the most robust framework for accurate gene quantification, particularly in clinical samples where RNA quality may be compromised.

Reverse transcription plays a fundamental role in determining the accuracy of gene quantification by RT-qPCR. Optimization of this critical first step—through careful attention to RNA integrity, reverse transcriptase selection, priming strategies, and appropriate normalization methods—ensures that resulting data truly reflect biological reality rather than technical artifacts. The protocols and quality control measures outlined in this application note provide a framework for generating reliable, reproducible gene expression data that can withstand the rigors of scientific scrutiny and facilitate meaningful biological insights. As RT-qPCR continues to be a cornerstone technology in molecular research and clinical diagnostics, adherence to these optimized practices becomes increasingly important for advancing our understanding of gene regulation and translating this knowledge into practical applications.

Within the framework of optimizing reverse transcription for quantitative PCR (qPCR) research, the selection of appropriate enzymatic components is paramount. The reverse transcription (RT) reaction, which converts RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), is a critical first step in RT-qPCR and a significant source of technical variability [8]. The properties of the reverse transcriptase enzyme itself—including its processivity, thermostability, and inherent enzymatic activities—directly influence cDNA yield, accuracy, and the faithful representation of the original RNA population [9] [10]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of reverse transcriptase properties, outlines selection criteria based on experimental requirements, and offers standardized protocols to ensure reproducible, high-quality results for gene expression analysis and drug development research.

Reverse Transcriptase Core Properties and Comparative Analysis

Reverse transcriptases are RNA-directed DNA polymerases. Their functionality in cDNA synthesis is governed by a set of key biochemical attributes that must be carefully matched to the experimental aims [9] [10].

- DNA Polymerase Activity: This is the primary function, enabling the enzyme to synthesize a DNA strand using an RNA template. The enzyme must operate efficiently in the presence of dNTPs and a divalent cation cofactor (Mg²⺠or Mn²âº) [10].

- RNase H Activity: This activity degrades the RNA strand in an RNA-DNA hybrid. While it can be beneficial for melting difficult structures during the initial PCR cycles, it is generally undesirable for producing long, full-length cDNAs because it can cleave the RNA template before the reverse transcriptase has finished synthesis [5] [10]. Engineered enzymes with reduced or eliminated RNase H activity often yield higher amounts of full-length cDNA [11] [10].

- Thermostability: An enzyme's ability to function at higher temperatures is crucial for denaturing RNA templates with extensive secondary structures or high GC content. Thermostable RTs allow reactions to be performed at temperatures up to 55°C or higher, leading to more efficient transcription of challenging templates and higher specificity in priming [11] [10].

- Processivity: This refers to the number of nucleotides a reverse transcriptase can incorporate in a single binding event. A highly processive enzyme can synthesize longer cDNA fragments more quickly and is often more tolerant of common reaction inhibitors found in RNA samples isolated from blood, plants, or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues [10].

- Fidelity: Fidelity denotes the accuracy of DNA synthesis. Wild-type reverse transcriptases have a high error rate because they lack 3'→5' proofreading exonuclease activity [12]. While this is negligible for most RT-qPCR applications, high-fidelity RTs are critical for applications like cDNA library construction and RNA sequencing [12].

- Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase (TdT) Activity: This activity results in the non-template-directed addition of extra nucleotides (typically dA, dG, or dC) to the 3' end of the synthesized cDNA. This is generally undesirable but can be exploited intentionally in techniques like RACE (Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends) and template-switching protocols for full-length cDNA cloning [10].

The table below provides a comparative analysis of common reverse transcriptases based on these properties.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Common Reverse Transcriptases

| Property | AMV Reverse Transcriptase | MMLV Reverse Transcriptase | Engineered MMLV RT (e.g., SuperScript IV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNase H Activity | High [11] | Medium [11] | Low or absent [11] |

| Optimal Reaction Temperature | 42°C - 48°C [11] | 37°C [11] | Up to 55°C [11] |

| Recommended Target Length | ≤ 5 kb [11] | ≤ 7 kb [11] | ≤ 12 kb [11] |

| Processivity | Moderate [11] | Lower than AMV [11] | High (e.g., ~65x wild-type MMLV) [10] |

| Fidelity (Error Rate) | Relatively high [10] | Lower than AMV [10] | Varies by engineering; proofreading versions available [12] |

| Best Suited For | Templates with strong secondary structure [11] | General-purpose, long transcripts (with low RNase H) [11] | GC-rich templates, long transcripts, degraded/inhibited samples [11] [10] |

Selection Criteria for Reverse Transcription Workflows

One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

The first major decision in experimental design is choosing between a one-step or two-step RT-qPCR protocol. This choice has significant implications for throughput, flexibility, and potential variability [5] [13].

Table 2: Comparison of One-Step and Two-Step RT-qPCR

| Factor | One-Step RT-qPCR | Two-Step RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow | Reverse transcription and qPCR occur in the same tube [5] | Reverse transcription and qPCR are performed in separate tubes [5] |

| Throughput | Suitable for high-throughput screening [5] | Less suited for high-throughput due to more handling steps [5] |

| Flexibility | Low; cDNA cannot be stored or used for multiple targets [13] | High; stable cDNA pool can be used for multiple qPCR assays [5] |

| Optimization | Compromised conditions for both RT and PCR [5] | Individual optimization of RT and PCR steps is possible [5] |

| Risk of Contamination | Lower, due to a closed-tube system [5] | Higher, due to additional pipetting steps [5] |

| Priming | Requires sequence-specific primers [5] | Flexible; can use oligo(dT), random, or gene-specific primers [5] |

Priming Strategies for cDNA Synthesis

The choice of primer for the reverse transcription reaction determines which RNA species are converted to cDNA and can impact yield, sensitivity, and the region of the transcript that is reverse-transcribed [5] [14].

- Oligo(dT) Primers: These primers, typically 12-18 nucleotides long, anneal to the poly(A) tail of eukaryotic mRNA. They are ideal for generating full-length cDNA and are preferred for analyzing gene expression of polyadenylated transcripts. However, they are not suitable for prokaryotic RNA, non-polyadenylated RNAs (e.g., some non-coding RNAs), or degraded RNA samples, and they can introduce a 3' bias [14] [15]. Anchored oligo(dT) primers, which include one degenerate nucleotide (V) at the 3' end, prevent "slippage" and ensure priming at the start of the poly(A) tail [14].

- Random Primers: These are short oligonucleotides (usually hexamers) with random sequences that anneal at multiple points along all RNA transcripts. This makes them suitable for all RNA types, including those without a poly(A) tail, degraded RNA, and transcripts with strong secondary structure. A drawback is that they generate a heterogeneous population of short cDNA fragments and can lead to the synthesis of cDNA from ribosomal RNA, potentially diluting the mRNA signal [14] [15].

- Gene-Specific Primers: These primers are designed to anneal to a specific mRNA sequence of interest. They offer the highest sensitivity for a single target by directing all RT activity to one transcript and are mandatory for one-step RT-PCR. Their main disadvantage is that a separate RT reaction is required for each gene being studied [5] [14].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate reverse transcriptase and priming strategy based on experimental goals.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Two-Step RT-qPCR for Gene Expression Analysis

This protocol is designed for high-quality total RNA and provides the flexibility to analyze multiple genes from a single cDNA synthesis reaction [5] [14].

I. First-Strand cDNA Synthesis

- RNA Template Preparation: Use high-integrity RNA (A260/A280 ratio ~2.0, RIN >8) [14]. Treat samples with DNase I or a double-strand-specific DNase (e.g., ezDNase) to remove genomic DNA contamination, followed by enzyme inactivation [14].

- Assemble the Reaction Mix in a nuclease-free tube on ice:

- 1 µg – 1 µL of total RNA (up to 1 µg)

- 1 µL of Oligo(dT)â‚₈ (50 µM) or 2 µL of Random Hexamers (50 µM) or 1 µL of Gene-Specific Primer (2 µM)

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 13 µL

- Denature RNA Secondary Structure: Incubate the mixture at 65°C for 5 minutes, then immediately place on ice for at least 1 minute.

- Prepare Master Mix: Combine on ice:

- 4 µL of 5X Reverse Transcription Buffer

- 1 µL of RNase Inhibitor (20 U/µL)

- 2 µL of Deoxynucleotide Mix (10 mM each dNTP)

- Combine and Equilibrate: Add the master mix to the primed RNA template. Mix gently and centrifuge briefly. Incubate at 25°C for 5 minutes for primer annealing.

- Initiate Reverse Transcription: Add 1 µL (200 U) of a selected reverse transcriptase (e.g., M-MLV RNase H- point mutant). Mix gently.

- Incubate: Perform the reverse transcription reaction:

- For Oligo(dT) or Gene-Specific primers: 50°C for 50 minutes.

- For Random Hexamers: 25°C for 10 minutes followed by 37°C for 50 minutes.

- Enzyme Inactivation: Heat the reaction at 70°C for 15 minutes to inactivate the reverse transcriptase. The resulting cDNA can be stored at -20°C or used directly in qPCR.

II. Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

- Prepare qPCR Reaction: Assemble reactions in a qPCR plate or tube:

- 10 µL of 2X SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix

- 2 µL of forward primer (10 µM)

- 2 µL of reverse primer (10 µM)

- 4 µL of nuclease-free water

- 2 µL of cDNA template (from the first-strand synthesis; a 1:5 or 1:10 dilution is often optimal)

- Run qPCR Program: Use the following standard cycling conditions on a real-time PCR instrument:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 3 minutes

- 40 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 30 seconds (acquire fluorescence)

- (Optional) Melt Curve: 65°C to 95°C, increment 0.5°C for 5 seconds each.

Protocol: Determining Reverse Transcription Efficiency

Accurate quantification in RT-qPCR requires an understanding of the efficiency (E) of the reverse transcription step, which can be highly variable and gene-specific [8]. This protocol uses synthetic RNA standards and digital PCR (dPCR) for absolute quantification.

- Obtain Synthetic RNA Standards: Acquire or synthesize known concentrations of in vitro transcribed (IVT) RNA for the gene of interest.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a dilution series of the IVT RNA (e.g., 10 fg, 1 fg, 100 ag per reaction) in a background of carrier RNA (e.g., 10 pg yeast RNA) to mimic a complex sample [8].

- Reverse Transcription: Perform the first-strand cDNA synthesis protocol (Section 4.1, Part I) on each dilution, including at least 10 technical replicates for each concentration to robustly assess variability.

- Digital PCR: Use the synthesized cDNA as a template for absolute quantification by dPCR.

- Assemble dPCR reactions according to the manufacturer's instructions for your system.

- Load the reaction mix into the dPCR chip or plate and run the amplification program.

- Data Analysis:

- The dPCR software will provide an absolute count of cDNA molecules per microliter.

- Calculate RT Efficiency: Compare the measured number of cDNA molecules to the known input number of RNA molecules.

- RT Efficiency (%) = (Number of cDNA molecules detected / Number of input RNA molecules) × 100% [8]

- Assess Variability: Calculate the Coefficient of Variation (CV = Standard Deviation / Mean) for the replicates at each concentration. A CV of less than 12% is generally acceptable [8].

- Incorporate into Analysis: The determined efficiency and variability values for each transcript should be factored into the final quantitative analysis of experimental RNA samples to improve accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reverse Transcription

| Item | Function & Importance | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality RNA | Starting template; integrity (RIN >8) and purity (A260/A280 ≈ 2.0) are critical for success [14]. | Qubit RNA Assay, Agilent Bioanalyzer |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Core enzyme for synthesizing cDNA from RNA. Selection is based on thermostability, RNase H activity, and processivity [11]. | SuperScript IV (Thermo Fisher), GoScript (Promega), Transcriptor High Fidelity (Roche) |

| Primers | Initiates cDNA synthesis. Choice (Oligo(dT), random, gene-specific) dictates which RNAs are reverse-transcribed [5] [14]. | Anchored Oligo(dT)â‚‚â‚€, Random Hexamers |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks for cDNA synthesis. | 10 mM solution of each dNTP |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects the RNA template from degradation by RNases during the reaction. | Recombinant RNase Inhibitor |

| DNase | Removes contaminating genomic DNA from RNA preparations to prevent false-positive signals in qPCR [14]. | DNase I, RNase-free; ezDNase (Thermo Fisher) |

| Buffer Systems | Provides optimal pH, ionic strength, and co-factors (Mg²âº) for enzyme activity. | 5X First-Strand Buffer |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and fluorescent dye (SYBR Green) or probe for real-time quantification [13]. | SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix, TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix |

| Neoandrographolide | Neoandrographolide, CAS:27215-14-1, MF:C26H40O8, MW:480.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Yamogenin | Yamogenin, CAS:512-06-1, MF:C27H42O3, MW:414.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- Genomic DNA Contamination: Always include a minus-reverse transcriptase control ("no-RT" control) in RT-qPCR experiments. If amplification is detected in this control, it indicates genomic DNA contamination. This can be addressed by DNase treatment during RNA purification or by designing PCR primers that span an exon-exon junction [5] [15].

- Low cDNA Yield: Ensure RNA is not degraded. Check the integrity of rRNA bands on a gel or the RNA Integrity Number (RIN). Increase the amount of reverse transcriptase or reaction time. Use a mixture of oligo(dT) and random primers to improve overall yield [14] [15].

- High Variability: Run replicates starting from the reverse transcription step. Use a master mix for both RT and qPCR steps to minimize pipetting error. Ensure the quality and quantity of input RNA are consistent across all samples [16] [8].

- Inhibition of Reverse Transcription: If using difficult sample types (e.g., blood, plant tissue), use a highly processive reverse transcriptase that is more resistant to inhibitors. Diluting the RNA sample or including additional purification steps may also help [10].

The accuracy of reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the starting RNA material. RNA integrity, purity, and structural characteristics directly impact cDNA synthesis efficiency and the subsequent reliability of gene expression quantification [17] [18]. For researchers and drug development professionals, failure to address these pre-analytical variables systematically can lead to false conclusions, wasted resources, and compromised experimental outcomes. This application note details evidence-based protocols to overcome the three major challenges in RNA analysis—integrity, purity, and secondary structures—within the critical context of reverse transcription optimization for qPCR workflows. Recognizing that quality requirements vary significantly across applications, with techniques like microarrays demanding higher standards than qPCR with its short amplicons, is essential for allocating resources appropriately [18].

Assessing RNA Integrity: From Traditional Methods to Advanced Metrics

Gel Electrophoresis-Based Assessment

The most traditional method for assessing RNA integrity involves denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis. Intact total RNA from eukaryotic samples displays sharp, clear 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA bands, with the 28S band exhibiting approximately twice the intensity of the 18S band (a 2:1 ratio) [17]. Partially degraded RNA appears as a smear with diminished or absent ribosomal bands, while completely degraded RNA manifests as a low molecular weight smear. While this method is accessible, its significant drawback is the relatively large amount of RNA required (at least 200 ng) for visualization with ethidium bromide, making it unsuitable for precious samples with low yields [17]. Alternative fluorescent stains like SYBR Gold or SYBR Green II can enhance sensitivity, detecting as little as 1-2 ng of RNA, but these stains still require significant hands-on time and present potential hazards [17] [18].

Table 1: Methods for Assessing RNA Integrity and Purity

| Method | Key Metric(s) | RNA Required | Information Provided | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturing Agarose Gel [17] | 28S:18S rRNA ratio (2:1 ideal) | ≥200 ng (EtBr); ~1-2 ng (SYBR dyes) | Visual assessment of degradation; qualitative | Semi-quantitative; requires significant RNA input; hazardous stains |

| UV Spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) [18] | A260/A280 (~1.8-2.2); A260/A230 (>1.7) | 0.5-2 µL | Concentration and purity (salt, solvent, protein contamination) | Does not detect degradation or genomic DNA contamination |

| Fluorometric Assays (e.g., QuantiFluor) [18] | Concentration via fluorescence | As little as 100 pg | Highly sensitive concentration measurement | No purity or integrity information; may bind DNA |

| Microfluidics Capillary Electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer) [17] [18] | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | 1 µL of 10 ng/µL | Quantitative integrity score, concentration, and purity | Higher instrument cost; specialized chips |

The RNA Integrity Number (RIN): A Quantitative Standard

The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) provides a standardized, numerical assessment of RNA quality (range 1-10, with 10 being fully intact) [19]. This algorithm considers the entire electrophoretic trace from microfluidics-based systems like the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, not just the ribosomal ratios, offering a more objective and reliable quality metric [17] [18]. The RIN metric is particularly valuable for applications requiring high-quality RNA and is emerging as a predictive tool in fields like genebanking, where it can detect early stages of RNA degradation in seeds before viability loss occurs [19]. This system simultaneously provides data on RNA concentration and purity, offering a comprehensive quality control assessment from a minimal sample aliquot (as little as 5 ng) [17].

Ensuring RNA Purity: Spectrophotometric and Fluorometric Methods

RNA purity is critical for downstream enzymatic reactions like reverse transcription. contaminants such as proteins, salts, guanidine thiocyanate, or phenolic compounds can inhibit enzyme activity and lead to inaccurate quantification [18].

UV Absorbance Ratios

UV spectrophotometry provides rapid assessment of common contaminants through absorbance ratios:

- A260/A280 Ratio: Primarily indicates protein contamination. A ratio of ~1.8–2.2 is generally accepted for pure RNA [18].

- A260/A230 Ratio: Indicates contamination from salts, solvents, or guanidine thiocyanate. Ratios typically >1.7 are considered acceptable [18].

It is crucial to note that absorbance methods cannot distinguish between RNA and DNA, nor can they detect RNA degradation, as nucleotides from degraded RNA still contribute to the 260 nm reading [18].

Fluorescent Dye-Based Quantification

Fluorometric methods (e.g., using QuantiFluor RNA System) offer superior sensitivity, detecting concentrations as low as 1 pg/μL, which is substantially lower than absorbance-based methods [18]. This makes them ideal for precious, low-yield samples. A significant limitation is that many fluorescent dyes are not RNA-specific and will also bind to DNA, potentially leading to overestimation of RNA concentration. To ensure accuracy, treatment of samples with DNase I prior to measurement is recommended [18] [20].

RNA Secondary Structures: Challenges and Computational Predictions

RNA molecules form complex secondary and tertiary structures through base pairing interactions, which play vital functional roles but can severely hinder reverse transcription and PCR amplification by blocking polymerase progression [21] [22].

The Impact of Secondary Structure on Reverse Transcription

Secondary structures such as stem-loops, hairpins, and pseudoknots can cause reverse transcriptase enzymes to stall or dissociate, leading to truncated cDNA products and biased representation of transcript abundance in downstream qPCR [21]. This is particularly problematic when the amplicon spans a region of stable secondary structure.

Advanced Prediction Methods

Computational methods for predicting RNA secondary structure have evolved from thermodynamic models (e.g., Vienna RNAfold) to modern deep learning (DL) approaches (e.g., SPOT-RNA, UFold, BPfold) [22]. These DL methods leverage large datasets to achieve high accuracy but often struggle with generalizability to unseen RNA families [22]. A recent integrative approach, BPfold, combines deep learning with a "base pair motif energy" library—a comprehensive enumeration of locally adjacent three-neighbor base pairs and their thermodynamic energies—to improve prediction robustness and accuracy, even for novel sequences [22]. Using these prediction tools during the assay design phase allows researchers to avoid primers in regions prone to stable secondary structures.

Table 2: Solutions for RNA Secondary Structure Challenges in RT-qPCR

| Challenge | Solution | Experimental Protocol | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase Pausing [20] | Use thermostable RT enzymes; increase RT temperature | Use Luna RT at 55–60°C for 10 min [20] | Improved full-length cDNA synthesis; reduced truncation artifacts |

| Primer Binding Inefficiency [23] | Design primers avoiding structured regions; use prediction tools | Use BPfold, SPOT-RNA, or UFold to predict structure; design primers in unstructured loops [22] | Lower Cq values; improved amplification efficiency |

| Low PCR Efficiency [20] | Design short amplicons (70–200 bp); use PCR additives | Keep GC content 40–60%; use 400 nM primer concentration; optimize with 100–900 nM range [20] | PCR efficiency of 90–110%; better linearity (R² ≥ 0.99) [20] |

Integrated Experimental Protocol for RT-qPCR Optimization

RNA Quality Control Protocol

- Extraction and Storage: Purify RNA using a method appropriate for your sample type. For long-term stability, resuspend and store purified RNA in EDTA-containing buffer (e.g., 1X TE) at -80°C [20].

- Quality Assessment:

- Concentration and Purity: Dilute 1-2 µL of RNA in nuclease-free water for UV spectrophotometry. Acceptable samples should have A260/A280 = 1.8–2.2 and A260/A230 > 1.7 [18]. For low-concentration samples, use a fluorometric RNA-specific assay.

- Integrity: Use an Agilent Bioanalyzer or similar system to determine the RIN. A RIN ≥ 8 is generally recommended for sensitive downstream applications like sequencing. For qPCR, lower RIN values may be acceptable depending on amplicon size [18].

- Genomic DNA Removal: Treat 1 µg of RNA with DNase I (e.g., NEB #M0303) according to manufacturer's instructions to eliminate genomic DNA contamination [20].

RT-qPCR Assay Design and Optimization

- Target and Primer Design:

- Select amplicons of 70–200 bp with GC content of 40–60% [20].

- Design primers 15–30 nucleotides long with Tm ≈ 60°C. For sequence-specific targeting, align all homologous gene sequences and place SNPs at the 3'-end of primers [23].

- Use computational tools (e.g., BPfold) to predict and avoid regions of strong secondary structure [22].

- One-Step RT-qPCR Setup:

- Prepare reactions on ice using a master mix. A typical 20 µL reaction contains 100 pg–100 ng total RNA, 400 nM of each primer, and appropriate master mix components [20].

- Include mandatory controls: no-template control (NTC) and no-RT control to check for contamination.

- Thermocycling and Analysis:

- Use the following modified cycling conditions for Luna kits: Reverse transcription at 55°C for 10 min (increase to 60°C for structured templates); initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min; 40–45 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 30 sec [20].

- Validate assay performance: PCR efficiency of 90–110%, linearity R² ≥ 0.99, and specificity confirmed by melt curve analysis [20].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA Analysis and RT-qPCR

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Key Features/Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with RNA 6000 LabChip [17] [18] | Integrated RNA quality assessment | Provides RIN, concentration, and purity from 1 µL sample (10 ng/µL); replaces multiple QC methods |

| SYBR Gold/SYBR Green II RNA gel stain [17] | High-sensitivity RNA detection in gels | Detects 1-2 ng RNA; safer alternative to ethidium bromide |

| Luna Universal One-Step RT-qPCR Kit [20] | Integrated reverse transcription and qPCR | WarmStart feature prevents non-specific amplification; inhibitor-resistant; includes passive reference dye |

| DNase I (e.g., NEB #M0303) [20] | Genomic DNA removal | Eliminates false-positive signals in RNA samples; essential for accurate gene expression analysis |

| Antarctic Thermolabile UDG (e.g., NEB #M0372) [20] | Carry-over contamination prevention | Degrades uracil-containing contaminants prior to amplification; incubation at room temperature |

| BPfold Software [22] | RNA secondary structure prediction | Deep learning approach integrated with base pair motif energy; superior generalizability for novel sequences |

Successful RT-qPCR outcomes depend on a systematic approach to RNA quality management. By implementing rigorous assessment of RNA integrity (using RIN when possible), verifying purity through spectrophotometric and fluorometric methods, and proactively addressing secondary structure challenges through computational prediction and optimized reverse transcription conditions, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their gene expression data. The protocols and solutions detailed in this application note provide a comprehensive framework for overcoming the major pre-analytical challenges in qPCR research, enabling more robust and reproducible results in both basic research and drug development applications.

Impact of RT Efficiency on Final qPCR Results and Data Interpretation

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is a cornerstone technique for gene expression analysis, yet its quantitative accuracy is fundamentally dependent on the efficiency of the initial reverse transcription (RT) step. This conversion of RNA to complementary DNA (cDNA) is widely recognized as a major source of inefficiency and variability in transcriptomics workflows [8]. The RT efficiency directly influences subsequent quantitative PCR (qPCR) results, potentially leading to inaccurate gene expression quantification if not properly controlled and understood. This application note examines the critical impact of RT efficiency on final qPCR results and provides detailed methodologies for optimizing, measuring, and accounting for this crucial parameter within the broader context of reverse transcription optimization for qPCR research.

The Critical Role of Reverse Transcription Efficiency

Understanding RT Efficiency and Its Consequences

Reverse transcription efficiency refers to the percentage of RNA molecules successfully converted into cDNA during the RT reaction. Ideal 100% efficiency would mean every RNA transcript is completely converted to a full-length cDNA copy. However, in practice, RT efficiency is highly variable and often substantially lower, leading to systematic underestimation of true RNA concentrations [8].

The fundamental problem stems from the multi-step nature of RT-qPCR: what is ultimately quantified in the qPCR reaction is not the original RNA, but the cDNA produced from it. Therefore, any inefficiency in the RT step directly reduces the starting template available for qPCR amplification. This effect is particularly problematic because it occurs before the qPCR quantification begins and cannot be corrected by normal qPCR controls. Studies have reported widely varying RT efficiency ranges from 0-114%, with much of this variability being gene-specific [8]. This transcript-dependent variability means that different genes within the same sample may be converted to cDNA with markedly different efficiencies, potentially distorting relative expression ratios.

Quantitative Impact on qPCR Results

The effect of RT efficiency on final quantification cycles (Cq values) is mathematically substantial. Research has demonstrated that varying primer concentrations alone—just one factor affecting RT efficiency—can lead to Cq value differences exceeding 5 cycles for some assays [24]. Since each Cq difference approximately corresponds to a two-fold change in template concentration, a 5-cycle difference represents a 32-fold (2âµ) difference in apparent transcript abundance, all attributable to suboptimal RT conditions rather than true biological variation.

Table 1: Documented Ranges of Reverse Transcription Efficiency from Literature

| Efficiency Range | Experimental System | Key Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| 49-114% [8] | Multiple systems | Primer selection, enzyme type, RNA quality |

| 50-77% [8] | Single-cell digital PCR | Sample type, reaction volume |

| 0-102% [8] | Probe-based assays | Background RNA, inhibitors |

| 39-65% [8] | SYBR Green assays | RNA secondary structure, GC content |

This efficiency problem extends to digital PCR (dPCR) platforms as well, demonstrating that the issue is fundamental to the RT process itself rather than specific to qPCR detection chemistry [8]. The gene-dependent nature of RT efficiency means that some transcripts reverse transcribe more efficiently than others, potentially distorting expression ratios in multi-gene panels.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing RT Efficiency

Determining RT Efficiency Using Synthetic RNA Standards

The most accurate method for determining absolute RT efficiency involves using synthetic in vitro-transcribed (IVT) RNA standards of known concentration. This approach eliminates biological variables and provides a direct measurement of conversion efficiency.

Materials Required:

- Purified IVT RNA standards for target genes of interest

- Selected reverse transcriptase and associated buffer system

- Primers (gene-specific, random hexamers, or oligo-dT)

- Digital PCR system or highly precise qPCR platform

- Nuclease-free water and standard molecular biology reagents

Procedure:

- Standard Preparation: Prepare a dilution series of IVT RNA standards covering the expected concentration range of your biological samples (e.g., 10 fg/μL to 100 ag/μL).

- Reverse Transcription: Perform RT reactions on each dilution using your standard protocol. Include sufficient replicates (minimum n=5-10) to assess variability.

- Absolute Quantification: Quantify the resulting cDNA using dPCR or a qPCR standard curve with known standards.

- Efficiency Calculation: Calculate RT efficiency for each transcript and concentration using the formula:

- Efficiency (%) = (cDNA molecules measured / RNA molecules input) × 100

- Variability Assessment: Determine the coefficient of variation (CV) for replicate measurements to assess technical variability [8].

This method provides transcript-specific efficiency values that can be directly incorporated into downstream quantification models to correct apparent expression levels.

Primer and Probe Optimization Matrix

Systematic optimization of primer and probe concentrations is essential for robust assay performance, particularly when establishing multi-gene panels requiring common cycling conditions.

Materials Required:

- Forward and reverse primers (100 μM stock solutions)

- Probe (if using probe-based chemistry, 100 μM stock)

- cDNA template (from a well-characterized control sample)

- qPCR master mix compatible with your detection chemistry

- qPCR instrument capable of multiplexed fluorescence detection

Procedure:

- Primer Matrix Setup: Prepare a primer concentration matrix testing multiple combinations of forward and reverse primers (e.g., 100 nM, 200 nM, and 300 nM each) while keeping all other reaction components constant [24].

- Probe Concentration Testing: For probe-based assays, test multiple probe concentrations (e.g., 100 nM and 200 nM) in combination with optimal primer concentrations [24].

- qPCR Amplification: Run all reactions using standardized cycling conditions appropriate for your assay.

- Performance Evaluation: Identify optimal conditions based on:

- Lowest Cq value with minimal replicate variability

- Absence of primer-dimer formation (verified by melt curve analysis for dye-based chemistries)

- Highest fluorescence amplitude (signal-to-noise ratio)

- Reaction efficiency between 90-110% when calculated from dilution series [25]

Table 2: Optimal Primer Concentration Distribution from Optimization Study

| Primer Concentration Combination | Percentage of Assays Optimal | Key Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Asymmetric concentrations | 65% | Improved efficiency for assays with differing primer properties |

| Symmetric concentrations (200 nM each) | 12% | Satisfactory for well-designed assays |

| Other symmetric combinations | 23% | Gene-specific requirements |

Research demonstrates that approximately 65% of assays perform optimally with asymmetric primer concentrations, while only 12% perform best with the commonly used default of 200 nM for each primer [24]. This highlights the critical importance of empirical optimization rather than relying on default conditions.

Key Optimization Strategies for Improved RT Efficiency

Reverse Transcriptase Selection

The choice of reverse transcriptase significantly impacts cDNA yield, especially with challenging templates. Different enzymes exhibit varying capabilities to reverse transcribe long transcripts, GC-rich regions, and templates with secondary structure.

Table 3: Properties of Common Reverse Transcriptases

| Property | AMV Reverse Transcriptase | MMLV Reverse Transcriptase | Engineered MMLV (e.g., SuperScript IV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNase H activity | High | Medium | Low |

| Reaction temperature | 42°C | 37°C | 55°C |

| Reaction time | 60 min | 60 min | 10 min |

| Target length | ≤5 kb | ≤7 kb | ≤12 kb |

| Yield with challenging RNA | Medium | Low | High |

Engineered MMLV reverse transcriptases with reduced RNase H activity and increased thermal stability generally provide superior performance for difficult templates and can significantly improve RT efficiency [14]. The higher reaction temperatures (up to 55°C) help denature RNA secondary structures that can impede reverse transcription.

Primer Selection Strategy

The choice of RT priming strategy should align with experimental goals and RNA characteristics:

- Oligo(dT) Primers: Ideal for eukaryotic mRNA analysis, full-length cDNA synthesis, and 3' RACE. Not suitable for degraded RNA, prokaryotic RNA, or RNAs lacking poly(A) tails. May introduce 3' bias [14].

- Random Hexamers: Enable reverse transcription of entire RNA populations, including non-coding RNAs. Suitable for degraded RNA (e.g., FFPE samples) and RNAs with secondary structure. Produce shorter cDNA fragments, especially at higher concentrations [14].

- Gene-Specific Primers: Provide the most specific priming for individual targets but are not suitable for transcriptome-wide analyses. Ideal for quantifying specific transcripts with maximal efficiency [14].

For comprehensive gene expression analysis, a mixture of oligo(dT) and random primers often provides the most balanced representation across transcript lengths and types.

RNA Quality and Purity Considerations

RNA integrity is fundamental to reliable RT efficiency. Several methods are available for assessing RNA quality:

- UV Spectrophotometry: A260/A280 ratios ~2.0 and A260/A230 ratios >1.8 indicate pure RNA free of protein and organic compound contamination [14].

- Fluorometric Methods: RNA-specific dyes (e.g., Qubit RNA assays) provide more accurate quantification than UV absorbance alone [14].

- Electrophoretic Methods: Gel-based assessment of 28S:18S rRNA ratios (~2:1 indicates intact RNA) or automated electrophoresis systems (RIN >8.0 indicates high-quality RNA) [14].

Genomic DNA contamination can cause false-positive signals and should be eliminated using DNase I treatment or double-strand-specific DNases that minimize RNA damage [14].

Data Interpretation and Normalization Accounting for RT Efficiency

Efficiency-Corrected Quantification

The standard 2−ΔΔCT method for relative quantification assumes perfect (100%) amplification efficiency for both target and reference genes. This assumption is frequently violated in practice, potentially introducing significant inaccuracies. Efficiency-corrected quantification incorporates actual measured efficiency values to improve accuracy:

- Calculate Per-Run Efficiency: Determine qPCR efficiency for each assay using a standard curve or linear regression method [26].

- Apply Efficiency Correction: Convert Cq values into efficiency-corrected target quantities using the formula:

- Quantity = Efficiency^(Cq)

- Normalize to Reference Genes: Calculate normalized expression values by dividing efficiency-corrected target quantities by the geometric mean of efficiency-corrected reference gene quantities [27].

Advanced statistical approaches such as Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) can provide greater robustness to efficiency variations compared to traditional 2−ΔΔCT methods, particularly when analyzing raw fluorescence data across multiple samples [27].

Reporting Guidelines

Adherence to the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines ensures transparent reporting of RT efficiency parameters [28]. Essential information to report includes:

- RNA quality assessment metrics (RIN, A260/A280, etc.)

- Reverse transcriptase and priming strategy used

- cDNA synthesis reaction conditions

- For each assay: measured RT efficiency values with associated variability

- qPCR amplification efficiency with confidence intervals

- Normalization strategy and reference gene validation

The updated MIQE 2.0 guidelines emphasize reporting Cq values as efficiency-corrected target quantities with prediction intervals to communicate measurement uncertainty appropriately [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for RT Efficiency Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptases | SuperScript IV, SuperScript III, SuperScript II | Converts RNA to cDNA; engineered enzymes offer higher temperature and processivity |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Qubit RNA IQ Assay, Agilent Bioanalyzer | Accurately determines RNA integrity and quantity |

| gDNA Removal | ezDNase, DNase I | Eliminates genomic DNA contamination without damaging RNA |

| Primers | Oligo(dT)20, Random Hexamers, Gene-specific | Initiates cDNA synthesis; choice affects coverage and bias |

| dNTPs | PCR-grade dNTP Mix | Building blocks for cDNA synthesis |

| RNase Inhibitors | Recombinant RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA templates from degradation |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green, TaqMan Master Mixes | Enables accurate quantification of cDNA |

| Reference Genes | ACTB, GAPDH, HPRT1, etc. | Provides stable normalization for relative quantification |

| Nesosteine | Nesosteine|CAS 84233-61-4|Research Chemical | Nesosteine is a chemical compound for research use only (RUO). It is strictly for laboratory applications and not for personal use. Request a quote today. |

| Netilmicin Sulfate | Netilmicin Sulfate, CAS:56391-57-2, MF:C42H92N10O34S5, MW:1441.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Impact Visualization

Diagram 1: Impact of RT Efficiency on qPCR Results. This workflow illustrates how various factors influence reverse transcription efficiency and subsequently impact final qPCR results through incomplete template conversion and gene-specific bias.

Reverse transcription efficiency is not merely a technical detail but a fundamental parameter that directly determines the accuracy of RT-qPCR quantification. The gene-dependent nature of RT efficiency, with variations capable of causing greater than 30-fold differences in apparent expression levels, necessitates careful optimization and characterization for each experimental system. Through systematic assessment of RNA quality, judicious selection of reverse transcriptase and priming strategy, empirical optimization of reaction conditions, and incorporation of efficiency values into data analysis, researchers can significantly improve the reliability and reproducibility of their RT-qPCR results. Adherence to these practices and comprehensive reporting in line with MIQE guidelines ensures that the impact of RT efficiency is appropriately accounted for in final data interpretation, ultimately leading to more biologically meaningful conclusions in gene expression studies.

Strategic Workflow Design: Selecting and Implementing the Optimal RT-qPCR Method

Within the broader context of optimizing reverse transcription for quantitative PCR (qPCR) research, the fundamental decision between employing a one-step or a two-step reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) protocol is a critical one. This choice significantly impacts the workflow, efficiency, reliability, and ultimate success of gene expression analysis, pathogen detection, and other RNA-based applications [29] [5]. RT-qPCR is a powerful and widely used method for detecting and quantifying RNA, where the RNA template is first transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) before quantitative PCR amplification [5]. This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of one-step and two-step RT-qPCR methodologies, offering structured data, detailed protocols, and clear guidance to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals select and optimize the most appropriate approach for their specific experimental needs.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Workflow Analysis

The core difference between the two methods lies in the configuration of the reverse transcription and PCR amplification steps.

- One-Step RT-qPCR combines the reverse transcription and PCR amplification in a single tube and reaction buffer, utilizing a reverse transcriptase along with a DNA polymerase. This method exclusively uses sequence-specific primers for both cDNA synthesis and amplification [29] [5].

- Two-Step RT-qPCR physically separates the reverse transcription and PCR amplification into two distinct reactions performed in separate tubes. This allows for individually optimized buffers, reaction conditions, and priming strategies for each step [29] [30].

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the procedural differences between these two methods.

One-Step RT-qPCR Workflow

Two-Step RT-qPCR Workflow

Systematic Comparison of Methodologies

The choice between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR involves a trade-off between workflow convenience and experimental flexibility. The two methods differ significantly in their primer requirements, suitability for different applications, and inherent advantages and disadvantages.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

| Feature | One-Step RT-qPCR | Two-Step RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Setup | Combined RT and PCR in a single tube/buffer [29] | Separate, optimized reactions for RT and PCR [29] |

| Priming Strategy | Gene-specific primers only [29] [30] | Oligo(dT), random hexamers, gene-specific primers, or a mix [30] [5] |

| Ideal Application | Analysis of a few genes; high-throughput screening [29] [31] | Analysis of multiple targets from a single RNA sample [29] [31] |

| Throughput | Amenable to high-throughput and automated platforms [29] | Less suitable for high-throughput due to extended workflow [29] |

| Sample Commitment | Full RNA sample is committed to a single target analysis [31] | cDNA pool can be stored and used for multiple future analyses [29] [5] |

| Sensitivity | Can be less sensitive due to compromised reaction conditions [29] | Potentially higher sensitivity and cDNA yield with optimized steps [29] [31] |

Table 2: Advantages and Disadvantages at a Glance

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| One-Step RT-qPCR | ||

| Two-Step RT-qPCR |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful RT-qPCR requires careful selection of reagents. The following table outlines key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for RT-qPCR

| Reagent | Function & Importance | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme that synthesizes cDNA from an RNA template [5]. | Thermostable RTs (e.g., engineered mutants) are preferred for higher temperature RT to resolve RNA secondary structure [30] [32]. |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Amplifies the cDNA template during qPCR. | Often provided in a master mix with buffers, dNTPs, and salts. Hot-start enzymes are common to prevent non-specific amplification [33]. |

| Primers (RT Step) | Initiates cDNA synthesis. | Two-Step: Oligo(dT) (for mRNA, biased to 3' end), random hexamers (for all RNA, can yield truncated cDNA), or gene-specific [5]. One-Step: Gene-specific only [29]. |

| Primers (qPCR Step) | Amplifies the specific target cDNA. | Should be 15-30 bp, Tm ~60°C, and designed to span an exon-exon junction to avoid genomic DNA amplification [5] [33]. |

| Fluorescence Detection System | Enables real-time quantification of amplicons. | Intercalating dyes (e.g., SYBR Green): Cost-effective; require reaction specificity [34]. Hydrolysis probes (e.g., TaqMan): Higher specificity; require probe design and optimization [34] [33]. |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protects the integrity of RNA templates during reaction setup. | Crucial for obtaining reliable and reproducible results, especially in two-step protocols. |

| dNTPs | Building blocks for cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification. | Provided in optimized concentrations in commercial master mixes. |

| Netivudine | Netivudine, CAS:84558-93-0, MF:C12H14N2O6, MW:282.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Netzahualcoyone | Netzahualcoyone, CAS:87686-36-0, MF:C30H36O6, MW:492.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for One-Step RT-qPCR

This protocol is ideal for high-throughput studies of a limited number of targets, such as viral load detection [32] or routine gene expression analysis.

- RNA Template Preparation: Use high-quality, purified RNA. For long-term stability, resuspend RNA in EDTA-containing buffer (e.g., TE). Treat samples with DNase I if primers cannot be designed to distinguish between cDNA and genomic DNA [5] [33]. A standard input range of 10 pg to 100 ng total RNA is recommended [33].

- Primer and Probe Design: Design gene-specific primers and probes.

- Primers: Length of 15-30 nucleotides; Tm ~60°C; 40-60% GC content; avoid secondary structures and G homopolymer repeats. Amplicons should be 70-200 bp for maximum efficiency [33].

- Probes (for TaqMan): Length of 15-30 nucleotides; Tm 5-10°C higher than primers; avoid a G at the 5' end; labeled with a 5' reporter dye and a 3' quencher [33].

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix on ice containing:

- 1X One-Step RT-qPCR Master Mix (contains RT enzyme, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer)

- Forward and Reverse Primers (typically 400 nM each, but may require optimization between 100-900 nM)

- Probe (if using, typically 200 nM, optimizable between 100-500 nM)

- RNA template

- Nuclease-free water to volume

- Include a no-RT control (replace RT enzyme with water) to check for genomic DNA contamination [5].

- Thermal Cycling: Perform in a real-time PCR instrument with a protocol similar to:

- Reverse Transcription: 55°C for 10-20 minutes (can be increased to 60°C for difficult templates) [33].

- RT Inactivation / Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 1-2 minutes.

- Amplification (40-45 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 10 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 30-60 seconds (acquire fluorescence at this step)

- Data Analysis: Generate a standard curve using serial dilutions of known template for absolute quantification, or use the comparative ΔΔCt method for relative quantification once assay efficiency (90-110%) and linearity (R² ≥ 0.99) are confirmed [33].

Protocol for Two-Step RT-qPCR

This protocol is preferred for analyzing multiple targets from a single, potentially scarce, RNA sample [31] [32], and allows for extensive reaction optimization.

Step 1: cDNA Synthesis

- RNA Template: Use 10 pg to 1 µg of total RNA in a 20 µl reaction [33].

- Priming: Use oligo(dT) primers (for mRNA), random hexamers (for all RNA including non-coding), a combination of both, or gene-specific primers. Consistent priming is key for comparative studies [5] [32].

- Reaction Setup: Combine RNA, primers, dNTPs, reverse transcriptase, and reaction buffer.

- Incubation: Typically 25°C for 10 minutes (for random hexamer annealing), followed by 42-55°C for 30-60 minutes for elongation, and finally 70°C for 15 minutes to inactivate the RT enzyme.

- Output: The resulting cDNA can be diluted and used immediately or stored at -20°C for long-term use [29].

Step 2: Quantitative PCR

- Template: Use 1-5 µl of the undiluted or diluted cDNA reaction per 20 µl qPCR.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix containing:

- 1X qPCR Master Mix (DNA polymerase, buffer, dNTPs, Mg²âº)

- Forward and Reverse Primers (optimized concentration, e.g., 400 nM)

- Probe or intercalating dye

- cDNA template

- Water to volume

- Thermal Cycling:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes

- Amplification (40 cycles): 95°C for 10 seconds (denaturation) and 60°C for 30-60 seconds (annealing/extension; acquire fluorescence).

- Controls: Include no-template controls (NTC) and, if needed, a no-RT control from the first step.

Critical Optimization Steps

- Primer and Probe Concentration: Optimize by testing a matrix of primer (e.g., 100-900 nM) and probe (e.g., 62.5-250 nM) concentrations to find the combination yielding the lowest Ct and highest fluorescence intensity [34].

- Annealing Temperature Optimization: Perform a gradient PCR (e.g., 51°C to 59°C) to determine the temperature that provides the highest reaction efficiency and specificity [23] [34].

- cDNA Input Concentration: Test a series of cDNA dilutions to ensure the reaction is within the dynamic range and is not inhibited. A standard curve with an R² ≥ 0.99 and efficiency of 100% ± 5% is ideal for reliable quantification using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method [23] [33].

The decision between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR is not a matter of which is universally superior, but which is more appropriate for the specific research context. The following diagram provides a logical pathway for making this decision.

Method Selection Guide

In conclusion, both one-step and two-step RT-qPCR are robust and invaluable tools in modern molecular biology. The one-step method offers speed, simplicity, and a minimized risk of contamination, making it the preferred choice for dedicated, high-throughput applications like diagnostic testing [35] [32] or repetitive analysis of a few genes. Conversely, the two-step method provides unparalleled flexibility, the ability to create a permanent cDNA archive, and superior optimization potential, making it ideal for exploratory research where analyzing multiple targets from a single, valuable RNA sample is required [29] [31]. By understanding the fundamental principles, carefully optimizing their protocols, and applying the selection logic outlined in this application note, researchers can confidently choose the optimal RT-qPCR strategy to ensure accurate, reliable, and efficient results for their specific projects in drug development and basic research.

Within the framework of reverse transcription optimization for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) research, the selection of an appropriate priming strategy is a critical foundational step that directly influences the accuracy, specificity, and efficiency of gene expression analysis. Reverse transcription (RT), the process of converting RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), is universally required for sensitive qPCR detection of RNA targets [4]. The short DNA oligonucleotide, or primer, that initiates this reaction dictates which RNA molecules are copied and how representatively the resulting cDNA pool reflects the original RNA population [36]. The three primary primer classes—oligo(dT) primers, random hexamers, and gene-specific primers (GSPs)—each possess distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations [14]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these strategies, supported by quantitative data and optimized protocols, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the most effective priming method for their specific experimental context.

Primer Mechanisms and Applications

Oligo(dT) Primers

Mechanism: Oligo(dT) primers are composed of a stretch of 12 to 18 deoxythymidine nucleotides that anneal specifically to the 3' poly(A)+ tail of eukaryotic messenger RNAs (mRNAs) [14]. This binding initiates cDNA synthesis starting from the extreme 3' end of the transcript.

Key Considerations:

- Specificity and Bias: This method ensures synthesis is restricted to polyadenylated mRNAs, which typically constitute only 1-5% of total RNA [14]. However, it can introduce a 3' bias in the cDNA representation. For long transcripts or those with significant secondary structure, reverse transcriptase may not reach the 5' end, leading to under-representation of sequences distal to the poly(A) tail [14].

- Risk of Truncation: A significant, often overlooked flaw is the generation of truncated cDNAs due to internal poly(A) priming. Oligo(dT) can anneal to internal stretches of adenosine residues within an mRNA sequence, resulting in cDNA products that are shortened at their 3' end. One study estimates that such artifacts may constitute up to 12% of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) in public databases [37].

- Mitigation Strategy: Using anchored oligo(dT) primers (e.g., VN or TTTTTTV, where V is A, G, or C) can effectively diminish internal priming by "locking" the primer to the very beginning of the poly(A) tail [37].

Random Hexamers

Mechanism: Random primers, most commonly random hexamers (NNNNNN), are oligonucleotides with random base sequences that can anneal to any complementary sequence on any RNA molecule—including mRNA, ribosomal RNA (rRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), and non-coding RNA—at multiple points along the transcript [38] [14].

Key Considerations:

- Comprehensive Coverage: This is the most general priming method, ideal for reverse transcribing all RNA species, notably those without poly(A) tails such as prokaryotic RNAs and some viral genomes [36]. It is also highly suitable for degraded RNA samples (e.g., from FFPE tissue), as it can generate cDNA fragments from any region of a partially degraded transcript [14].

- Lack of 3' Bias and Risk of Shorter Products: Because priming occurs throughout the transcript length, random hexamers facilitate a more uniform representation of the entire RNA molecule, reducing 3' bias [36]. However, increasing the concentration of random hexamers promotes binding at multiple sites on a single template, favoring the production of shorter cDNA fragments at the expense of full-length products [14].

Gene-Specific Primers (GSPs)

Mechanism: Gene-specific primers are designed to be perfectly complementary to a predefined sequence of a target RNA of interest. They are typically 18-25 nucleotides in length and offer the highest specificity among the three methods [4].

Key Considerations:

- Maximum Specificity and Sensitivity: GSPs are the primer of choice for one-step RT-qPCR protocols, where cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification occur in a single tube. They directly target the gene of interest, thereby enhancing sensitivity for low-abundance transcripts and minimizing background from non-target RNAs [39].

- Limited Utility: The primary limitation of GSPs is that they are designed for a single target. Consequently, they are not suitable for applications requiring the synthesis of a broad cDNA library for multiple downstream gene expression analyses [14].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanistic differences between these three priming strategies.

Comparative Analysis and Strategic Selection

Quantitative Performance Comparison

A systematic comparison using GoScript Reverse Transcription Mixes highlights how priming strategy affects the detection of genes with varying abundance. In this study, reverse transcription was performed on serial dilutions of Universal Human Reference RNA using oligo(dT), random primers, or a 50/50 mixture. The resulting cDNA was analyzed via qPCR for three genes: high-abundance GAPDH, medium-abundance SDHA, and low-abundance UBC [36].

Table 1: Average Cq Values from Comparison of Reverse Transcription Priming Methods

| Target Gene | Expression Level | Oligo(dT) Primers | Random Primers | Mixed Primers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | High | 21.7 | 21.5 | 21.5 |

| SDHA | Medium | 26.9 | 25.3 | 25.4 |

| UBC | Low | 30.5 | 28.6 | 28.7 |

Source: Adapted from Hook and Lewis, 2017 [36].

The data demonstrates that while all methods perform similarly for high-abundance targets, random and mixed primers yield significantly lower (better) Cq values for medium- and low-abundance transcripts, suggesting a more efficient conversion of these RNAs [36].

Strategic Selection Workflow

Choosing the optimal primer is a strategic decision based on RNA template characteristics and experimental goals. The following workflow provides a guided approach to this selection process.

Table 2: Comprehensive Characteristics of Reverse Transcription Priming Strategies

| Feature | Oligo(dT) Primers | Random Primers | Gene-Specific Primers | Mixed Primers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Site | Poly(A) tail of mRNA [14] | Anywhere on any RNA [14] | Pre-defined gene sequence [4] | Poly(A) tail & random sites |

| Ideal RNA Template | Intact eukaryotic mRNA [14] | Degraded RNA, prokaryotic RNA, viral RNA, total RNA [36] [14] | Any RNA for a specific target | Eukaryotic mRNA & total RNA |

| cDNA Representative-ness | 3' biased; may under-represent 5' ends [14] | More uniform coverage; no 3' bias [36] | Specific only to the target | Comprehensive; combines benefits |

| Primary Applications | cDNA libraries, 3' RACE, full-length cloning [14] | Gene expression profiling (multiple targets), degraded samples [39] [14] | One-step RT-qPCR, low-abundance targets [39] | Two-step RT-qPCR for versatile profiling [36] [40] |

| Key Advantages | Specific for poly(A)+ mRNA; good for full-length cDNA [14] | Most general method; works with degraded RNA [36] | High sensitivity and specificity [4] | Balances coverage and yield [36] |

| Key Limitations | Not for non-poly(A) RNA; internal priming artifacts [37] | May yield shorter cDNAs; can prime rRNA [14] | Only for one pre-determined target [14] | Requires optimization of ratio |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Comparative Analysis of Priming Strategies

This protocol is adapted from the Promega GoScript comparison study to empirically determine the optimal priming method for specific targets [36].

I. Materials

- RNA Sample: Universal Human Reference RNA or your specific RNA of known concentration.

- Reverse Transcription Kits: GoScript Reverse Transcription Mix, Oligo(dT) (Cat.# A2790); GoScript Reverse Transcription Mix, Random Primers (Cat.# A2800).

- qPCR Master Mix: e.g., GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Cat.# A6001).

- Primers: Validated qPCR primers for high-, medium-, and low-abundance genes.

- Equipment: Veriti 96-Well Thermal Cycler (or equivalent), CFX96 Real-Time Detection System (or equivalent), microcentrifuge, nuclease-free tubes and tips.

II. Procedure

- RNA Serial Dilution: Prepare an 8-point tenfold serial dilution of the reference RNA, ranging from 100 ng/µL to 1 fg/µL, in nuclease-free water.

- Reverse Transcription:

- Set up three separate RT reactions for each RNA sample point:

- Condition A (Oligo(dT)): Use 4 µL of GoScript Oligo(dT) Mix per reaction.

- Condition B (Random): Use 4 µL of GoScript Random Primers Mix per reaction.

- Condition C (Mixed): Use 2 µL of GoScript Oligo(dT) Mix + 2 µL of GoScript Random Primers Mix per reaction.

- Perform reverse transcription according to the manufacturer's protocol (e.g., 25°C for 5 min, 42°C for 60 min, 70°C for 15 min).

- Set up three separate RT reactions for each RNA sample point:

- Quantitative PCR:

- For each cDNA product, perform qPCR in a 20 µL total reaction volume using a qPCR master mix. Use 2 µL of the undiluted RT reaction product as template.

- Run triplicate reactions for each primer set (GAPDH, SDHA, UBC or your selected targets).

- Use the following cycling conditions: Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 min; 40 cycles of: 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 60 sec.

III. Data Analysis

- Record the average Cq values for each target gene under each priming condition (as in Table 1).

- Generate standard curves from the serial dilution for each gene and condition. Calculate PCR amplification efficiency (E) using the formula E = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) * 100%. An efficiency of 90–110% is generally acceptable [36].

- The optimal priming strategy is indicated by the lowest Cq values for your targets of interest and PCR efficiencies within the acceptable range.

Protocol: Two-Step RT-qPCR with Mixed Primers

This is a generalized, optimized protocol for two-step RT-qPCR, which is ideal for analyzing multiple targets from a single RNA sample [39] [40].

I. First-Strand cDNA Synthesis

- RNA Denaturation: In a nuclease-free tube, combine 1 µg of high-quality total RNA (A260/A280 ≈ 2.0), 1 µL of a mixed primer solution (e.g., 0.5 µg Oligo(dT) and 0.5 µg Random Hexamers), and nuclease-free water to 12 µL. Incubate at 70°C for 5 minutes to denature secondary structures, then immediately place on ice.

- Prepare Master Mix: On ice, prepare the following master mix for each reaction:

- 4 µL 5X Reaction Buffer

- 1 µL RNase Inhibitor (optional)

- 2 µL 10mM dNTP Mix

- 1 µL Reverse Transcriptase (e.g., MMLV or engineered variants)