STAR RNA-seq Workflow: A Comprehensive Benchmarking and Optimization Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a definitive guide to the STAR RNA-seq alignment workflow, offering a critical comparison with alternative pipelines like Salmon and HISAT2.

STAR RNA-seq Workflow: A Comprehensive Benchmarking and Optimization Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide to the STAR RNA-seq alignment workflow, offering a critical comparison with alternative pipelines like Salmon and HISAT2. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes findings from large-scale benchmarking studies to explore foundational concepts, methodological applications, common troubleshooting issues, and performance validation. The content delivers actionable insights for selecting, optimizing, and validating RNA-seq pipelines to ensure accurate and reproducible transcriptomic analysis in both basic research and clinical settings, with a focus on achieving reliable detection of subtle differential expression crucial for biomarker discovery.

Understanding RNA-seq Alignment: The Role of STAR in the Modern Transcriptomics Toolkit

The Central Role of Alignment in RNA-seq Analysis

A critical step in RNA-seq analysis is aligning sequencing reads to a reference genome or transcriptome. The choice of alignment tool directly impacts the accuracy of all downstream analyses, from differential expression to novel transcript discovery [1]. This guide compares the performance of prominent RNA-seq aligners, focusing on the STAR workflow and its alternatives, to help researchers make informed decisions.

Alignment Algorithms: A Fundamental Divide

The core difference between alignment tools lies in their underlying algorithms, which dictate their speed, resource consumption, and optimal use cases.

Traditional Read-Mapping Aligners

These tools perform full alignment of reads to a reference genome, providing detailed positional information.

- STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference): Uses a seed-search and clustering algorithm to identify maximal mappable prefixes (MMPs), making it particularly adept at detecting splice junctions without prior annotation [2]. It is a comprehensive aligner that produces a BAM file of alignments and can simultaneously output read counts [1] [3].

- HISAT2 (Hierarchical Indexing for Spliced Alignment of Transcripts 2): Employs a Hierarchical Graph FM index (HGFM) to efficiently map reads against a global genome index and numerous small local indexes, which reduces memory usage compared to STAR [2].

Pseudoalignment / Lightweight Quantifiers

These tools bypass full alignment for quantification purposes, offering significant speed advantages.

- Kallisto: Utilizes a pseudoalignment algorithm that compares k-mers in the reads directly to a reference transcriptome to determine compatibility, avoiding the computationally intensive steps of computing misalignments or reporting full alignment positions [1] [4].

- Salmon: Employs a similar selective alignment approach but incorporates additional sample-specific bias models (e.g., for GC content and sequence biases) to refine its abundance estimates [4] [5].

Table 1: Core Algorithmic Differences Between RNA-seq Alignment and Quantification Tools

| Tool | Core Algorithm | Reference Type | Primary Output | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR | Maximal Mappable Prefix (MMP) search [2] | Genome | Aligned reads (BAM), read counts [1] | Splice junction discovery [1] |

| HISAT2 | Hierarchical Graph FM index [2] | Genome | Aligned reads (BAM) | Lower memory footprint [5] |

| Kallisto | Pseudoalignment via k-mer matching [4] | Transcriptome | Transcript abundances (TPM/Counts) [1] | Speed and simplicity [5] |

| Salmon | Selective alignment with bias correction [4] | Transcriptome | Transcript abundances (TPM/Counts) | Advanced bias modeling [5] |

| Eicosyl methane sulfonate | Eicosyl methane sulfonate, MF:C21H44O3S, MW:376.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| Sacituzumab Govitecan | Sacituzumab Govitecan, CAS:1491917-83-9, MF:C76H104N12O24S, MW:1601.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Independent benchmarking studies reveal critical trade-offs between accuracy, computational speed, and resource requirements.

Base-Level and Junction-Level Accuracy

A comprehensive benchmarking study using simulated Arabidopsis thaliana data assessed alignment accuracy at both the base level and the more challenging junction level [2].

- STAR demonstrated superior performance in base-level accuracy, achieving over 90% accuracy under various test conditions [2].

- SubRead aligner emerged as the most promising for junction base-level accuracy, with an overall accuracy of over 80% [2].

- Performance consistency of aligners was noted at the base level, but junction-level assessment produced varying results depending on the applied algorithm [2].

Runtime and Memory Consumption

Computational demands are a major practical consideration, especially for large-scale studies.

- STAR is characterized by fast alignment but requires substantial memory (RAM), as it builds large genome indices to accelerate mapping [5].

- HISAT2 provides a balanced compromise, focusing on a smaller memory footprint while maintaining competitive, splice-aware mapping accuracy [5].

- Kallisto and Salmon show dramatic speedups and reduced storage needs as they avoid full alignment, with Kallisto often noted for its simplicity and speed [4] [5].

Table 2: Performance and Resource Comparison Based on Benchmarking Studies

| Tool | Base-Level Accuracy | Junction-Level Accuracy | Typical Runtime | Memory Footprint |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR | ~90% and above (Superior) [2] | Varies (Dependent on algorithm) [2] | Fast [5] | High (Substantial RAM usage) [5] |

| HISAT2 | Information missing | Information missing | Moderate [5] | Low (Small memory footprint) [5] |

| Kallisto | Information missing | Information missing | Very Fast [4] [5] | Low [4] |

| Salmon | Information missing | Information missing | Very Fast [5] | Low [4] |

Experimental Factors Influencing Tool Selection

The optimal choice of an aligner is not universal; it depends heavily on the experimental design and data quality [1].

Impact of Experimental Design

- Transcriptome Completeness: For well-annotated transcriptomes, Kallisto's pseudoalignment offers speed and accuracy. When the transcriptome is incomplete or contains many novel splice junctions, STAR's traditional alignment is more suitable [1].

- Sample Size and Resources: For large-scale studies with hundreds of samples, Kallisto's speed and lower memory usage are advantageous. For smaller studies where computational resources are less constrained, STAR's comprehensive alignment may be preferred [1].

Impact of Data Quality and Type

- Read Length: Kallisto performs well with short read lengths, while STAR may be more suitable for longer reads which can help identify novel splice junctions [1].

- Analysis Goal: For rapid quantification of gene expression levels, Kallisto is an excellent choice. If the goal is to uncover novel splice junctions, detect fusion genes, or perform variant calling, STAR is the superior option [1] [5].

- Single-Cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq): Specific tools like STARsolo (part of the STAR package) and Kallisto-bustools are designed to handle the demands of scRNA-seq data, including cell barcode and UMI processing. Benchmarks show differences in cell detection and gene quantification, with tools like Alevin showing strength in avoiding overrepresentation of cells with low gene content [4].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Aligners

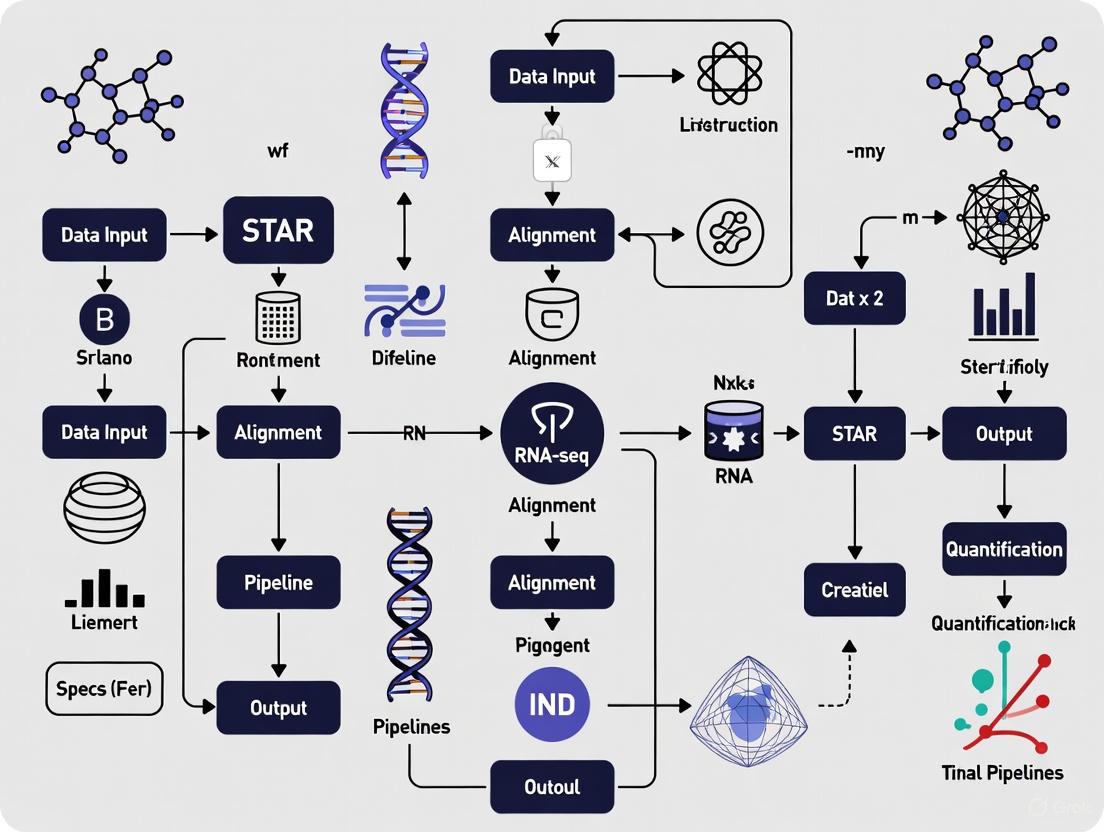

To ensure fair and reproducible comparisons, benchmarking studies typically follow a structured workflow. The diagram below outlines a standard protocol for evaluating aligner performance using both simulated and real RNA-seq data.

Key Steps in the Workflow:

- Genome Collection and Indexing: A standard reference genome (e.g., human, mouse, or A. thaliana) and its annotation file (GTF/GFF) are collected. Each aligner builds its specific index from this reference [2].

- RNA-seq Data Simulation: Tools like Polyester are used to generate synthetic RNA-seq reads. Simulation allows for the introduction of known features like SNPs, indels, and differential expression, providing a ground truth for assessing accuracy [2].

- Read Preprocessing: Raw sequencing reads (FASTQ) are processed with quality control tools like FastQC and trimming tools like Trimmomatic or fastp to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases, ensuring clean input for alignment [6] [7].

- Execution of Alignments: The preprocessed reads are aligned using each tool under evaluation (e.g., STAR, HISAT2, Kallisto). Both default and optimally tuned parameters should be tested, as performance can vary significantly with different settings [8] [2].

- Performance Assessment: The outputs of each aligner are evaluated against the known ground truth from simulation.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for RNA-seq Alignment Analysis

| Item / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Reference Genome | The sequence to which reads are mapped (e.g., GRCh38 for human). |

| Annotation File (GTF/GFF) | Provides the coordinates of genes, transcripts, and exons for guided alignment and quantification. |

| FastQC | Quality control tool for high-throughput sequence data, checks for adapter contamination, base quality, etc. [6] [7] |

| Trimmomatic / fastp | Tools to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases from raw reads [6] [7]. |

| STAR | Aligner for comprehensive splice-aware mapping to a reference genome [1] [2]. |

| Kallisto | Pseudoaligner for ultra-fast transcript-level quantification [1] [4]. |

| Salmon | Lightweight quantifier with bias correction for accurate transcript abundance estimates [4] [5]. |

| DESeq2 / EdgeR | Downstream differential expression analysis packages that use count matrices from tools like STAR or transcript-level abundances from Kallisto/Salmon (after aggregation to the gene level) [5] [7]. |

The choice of an RNA-seq alignment tool involves balancing accuracy, computational cost, and the specific biological question. Based on the benchmarking data and functional comparisons:

- For comprehensive genomic analyses where the discovery of novel splice junctions, fusion genes, or variant identification is a priority, and where sufficient computational resources (especially memory) are available, STAR is the recommended choice due to its high base-level accuracy and powerful junction discovery [1] [2].

- For focused transcript-level quantification in large-scale differential expression studies where speed and computational efficiency are paramount, Kallisto or Salmon provide excellent accuracy with dramatic reductions in runtime and storage requirements [1] [5].

- In environments with limited computational memory, HISAT2 offers a robust, splice-aware alternative to STAR with a significantly smaller footprint [5].

Ultimately, researchers should consider their experimental design, data quality, and analytical goals when selecting an aligner, as there is no single best tool for all scenarios [1].

STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) represents a fundamental shift in RNA-seq read alignment methodology, employing a sequential maximum mappable prefix search strategy that enables unprecedented mapping speeds while maintaining high accuracy. This algorithm outperforms traditional aligners by more than a factor of 50 in mapping speed, aligning 550 million 2×76 bp paired-end reads per hour on a modest 12-core server, while simultaneously improving alignment sensitivity and precision. Engineered specifically for spliced alignment challenges, STAR's core innovation lies in its two-phase process of seed searching followed by clustering, stitching, and scoring, allowing it to accurately identify canonical and non-canonical splices, chimeric transcripts, and full-length RNA sequences without a priori junction databases. Benchmarking studies demonstrate that STAR generates more precise alignments compared to HISAT2, which shows propensity to misalign reads to retrogene genomic loci, particularly in clinically relevant FFPE samples. As RNA-seq applications expand across diverse biological and clinical contexts, understanding STAR's algorithmic foundations provides researchers with critical insights for selecting appropriate alignment tools based on their specific experimental requirements, computational resources, and analytical objectives.

The alignment of high-throughput RNA sequencing data presents unique computational challenges distinct from DNA read mapping, primarily due to the non-contiguous nature of transcript sequences resulting from splicing. Eukaryotic cells reorganize genomic information by splicing together non-contiguous exons to create mature transcripts, requiring aligners to identify reads spanning splice junctions that may be separated by large genomic distances. Prior to STAR's development, available RNA-seq aligners suffered from significant limitations including high mapping error rates, low mapping speed, read length restrictions, and mapping biases that compromised their utility for large-scale transcriptome projects.

STAR was originally developed to align the massive ENCODE Transcriptome RNA-seq dataset exceeding 80 billion reads, necessitating breakthroughs in both alignment accuracy and computational efficiency. The algorithm's design specifically addresses the two fundamental tasks of RNA-seq alignment: accurate alignment of reads containing mismatches, insertions, and deletions caused by genomic variations and sequencing errors; and precise mapping of sequences derived from non-contiguous genomic regions comprising spliced sequence modules. Unlike earlier approaches that extended DNA short read mappers through junction databases or arbitrary read splitting, STAR implements a novel strategy that aligns non-contiguous sequences directly to the reference genome without requiring preliminary contiguous alignment passes.

STAR has established itself as one of the two predominant aligners in contemporary RNA-seq analysis alongside HISAT2, having superseded earlier tools like TopHat due to superior computational speed and alignment accuracy. Its performance advantages are particularly evident in large-scale consortia efforts and clinical research settings where both throughput and precision are paramount, especially when working with challenging sample types like formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues that exhibit increased RNA degradation and decreased poly-A binding affinity.

Core Algorithmic Framework

The Two-Step Alignment Strategy

STAR's algorithmic architecture employs a carefully engineered two-step process that enables both exceptional speed and accuracy in spliced alignment. This structured approach allows STAR to efficiently handle the computational challenges inherent in RNA-seq mapping while maintaining precision in junction detection.

Maximal Mappable Prefix (MMP) Search

The cornerstone of STAR's efficiency lies in its Maximal Mappable Prefix search strategy, which fundamentally differs from the approaches used by earlier generation aligners. The MMP is formally defined as the longest substring starting from a given read position that matches exactly one or more substrings of the reference genome. This sequential application of MMP search exclusively to unmapped read portions creates significant computational advantages over methods that find all possible maximal exact matches before processing.

STAR implements MMP search through uncompressed suffix arrays, which provide several algorithmic benefits. The binary search nature of suffix array lookups yields logarithmic scaling of search time with reference genome length, enabling rapid searching even against large mammalian genomes. For each MMP identified, the suffix array search can efficiently locate all distinct exact genomic matches with minimal computational overhead, facilitating accurate alignment of multimapping reads. This approach also naturally accommodates variable read lengths without performance degradation, making it suitable for emerging sequencing technologies that generate longer reads.

The MMP search handles various alignment scenarios through structured fallback mechanisms. When exact matching is interrupted by mismatches or indels, the identified MMPs serve as anchors that can be extended with allowance for alignment errors. In cases where extension fails to produce viable alignments, the algorithm can identify and soft-clip poor quality sequences, adapter contaminants, or poly-A tails. The search is conducted bidirectionally from the read ends and can be initiated from user-defined start points throughout the read, enhancing mapping sensitivity for reads with elevated error rates near terminal.

Clustering, Stitching, and Scoring

Following seed identification, STAR enters its comprehensive clustering and stitching phase, which reconstructs complete alignments from the discrete MMP segments. The process begins with clustering seeds based on proximity to strategically selected "anchor" seeds—preferentially chosen from seeds with limited genomic mapping locations to reduce computational complexity. This clustering occurs within user-defined genomic windows that effectively determine the maximum intron size permitted for spliced alignments.

The stitching process employs a frugal dynamic programming algorithm that connects seed pairs while allowing for unlimited mismatches but restricting to single insertion or deletion events. This balanced approach maintains computational efficiency while accommodating common sequencing artifacts. The scoring system evaluates potential alignments based on comprehensive parameters including mismatch counts, indel penalties, and gap penalties, with user-definable weightings that can be optimized for specific experimental conditions or organismal characteristics.

A particularly innovative aspect of STAR's algorithm is its principled handling of paired-end reads. Rather than processing mates independently, STAR clusters and stitches seeds from both mates concurrently, treating the paired-end read as a single contiguous sequence with a potential gap or overlap between inner ends. This methodology increases alignment sensitivity significantly, as a single correct anchor from either mate can facilitate accurate alignment of the entire read pair. The algorithm also systematically explores chimeric alignment possibilities, detecting arrangements where read segments map to distal genomic loci, different chromosomes, or opposing strands, enabling identification of fusion transcripts and complex rearrangement events.

Performance Comparison with Alternative Aligners

Comprehensive Benchmarking Results

Multiple independent studies have systematically evaluated STAR's performance against other prominent RNA-seq aligners across various metrics including alignment accuracy, computational efficiency, splice junction detection, and performance with degraded samples. The results demonstrate context-dependent advantages that inform tool selection for specific research scenarios.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of RNA-seq Alignment Tools

| Performance Metric | STAR | HISAT2 | BWA | TopHat2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment Speed | 550 million reads/hour (12 cores) [10] | Fastest in category [11] | Not specified | Significantly slower than STAR [10] |

| Alignment Rate | High precision, especially for spliced reads [12] | High speed with good accuracy [11] | Highest alignment rate [11] | Lower mapping speed [10] |

| Memory Requirements | High (~30GB for human genome) [13] [14] | Moderate [12] | Moderate | Moderate |

| Splice Junction Detection | Excellent for novel junctions [10] [14] | Good with known junctions [12] | Not specified | Good with known junctions |

| FFPE Sample Performance | Superior alignment precision [12] | Prone to retrogene misalignment [12] | Not specified | Not specified |

| Chimeric RNA Detection | Built-in capability [10] [14] | Limited | Not specified | Limited |

When compared specifically with HISAT2—the other leading contemporary aligner—STAR demonstrates particular advantages in scenarios requiring precise alignment of challenging sequences. In a comprehensive analysis of breast cancer progression series from FFPE samples, STAR generated significantly more precise alignments, while HISAT2 showed propensity to misalign reads to retrogene genomic loci, particularly in early neoplasia samples [12]. This precision advantage makes STAR particularly valuable for clinical research applications where accurate variant calling and junction detection are critical for downstream analysis.

Experimental Validation of Alignment Accuracy

The precision of STAR's alignment strategy, particularly for novel splice junction detection, has been rigorously validated through experimental approaches. In the original algorithm development paper, researchers experimentally validated 1,960 novel intergenic splice junctions discovered by STAR using Roche 454 sequencing of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction amplicons, achieving impressive validation rates of 80-90% [10]. This high confirmation rate demonstrates STAR's exceptional precision in identifying bona fide splicing events rather than computational artifacts.

STAR's sophisticated handling of spliced alignment enables detection of diverse transcriptomic features beyond standard splice junctions. The algorithm can identify non-canonical splices, chimeric (fusion) transcripts, and circular RNAs through its comprehensive alignment scoring system and capacity to detect discontinuities in genomic mapping. This capability was demonstrated through successful detection of the BCR-ABL fusion transcript in K562 erythroleukemia cells, showcasing its utility in cancer transcriptomics [10]. The aligner's capacity to map full-length RNA sequences further positions it as a valuable tool for emerging third-generation sequencing technologies that generate longer reads.

Implementation Protocols

Genome Index Generation

Constructing a properly optimized genome index represents a critical prerequisite for efficient STAR alignment. The indexing process requires careful parameter selection tailored to the specific experimental design and reference genome characteristics.

Table 2: Essential Parameters for STAR Genome Index Generation

| Parameter | Typical Setting | Explanation | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

--runThreadN |

6-12 cores | Number of parallel threads | Increases indexing speed proportionally |

--runMode |

genomeGenerate | Specifies index generation mode | Required for creating indices |

--genomeDir |

/path/to/directory | Output directory for indices | Critical for organizational structure |

--genomeFastaFiles |

/path/to/fa | Reference genome FASTA file(s) | Determines reference sequences |

--sjdbGTFfile |

/path/to/gtf | Gene annotation GTF file | Crucial for splice junction awareness |

--sjdbOverhang |

ReadLength-1 | Overhang for splice junctions | Optimizes junction detection; 100 is commonly used [13] |

A typical genome indexing command follows this structure:

The --sjdbOverhang parameter deserves particular attention, as it specifies the length of the genomic sequence around annotated junctions to be included in the index. The optimal value equals the maximum read length minus 1, though the default value of 100 performs well in most scenarios with reads of varying lengths [13].

Read Alignment Protocol

The core alignment process in STAR requires careful parameterization to balance sensitivity, specificity, and computational efficiency based on experimental requirements.

A standard alignment command for paired-end reads demonstrates the essential parameters:

For advanced applications, STAR supports specialized mapping strategies including a two-pass alignment method for enhanced novel junction discovery. This approach involves a first mapping pass to detect novel junctions, followed by genome re-indexing incorporating these newly discovered junctions, and a second mapping pass using the enhanced index. This strategy significantly improves sensitivity for detecting rare splicing events and condition-specific junctions without compromising alignment speed.

The Researcher's Toolkit for STAR Alignment

Successful implementation of STAR alignment workflows requires appropriate computational infrastructure and software components tailored to the scale of the RNA-seq experiment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for STAR Implementation

| Resource Type | Specific Solution | Function/Role | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | ENSEMBL GRCh38 (human) | Genomic coordinate system | Ensure compatibility with annotation version |

| Gene Annotations | ENSEMBL GTF file | Splice junction awareness | Critical for alignment accuracy |

| Quality Control | FastQC | Raw read quality assessment | Identifies need for trimming |

| Read Trimming | fastp, Trimmomatic | Adapter removal, quality filtering | fastp shows superior quality enhancement [6] |

| Memory Resources | 32-64 GB RAM | Genome loading and alignment | Human genome requires ~30GB [14] |

| Processing Cores | 8-16 CPU cores | Parallel alignment | Reduces computation time significantly |

| Storage | High-speed SSD | Intermediate file handling | Improves I/O performance during alignment |

| FAM49B (190-198) mouse | FAM49B (190-198) mouse, MF:C49H71N9O14S, MW:1042.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| TP-004 | TP-004, MF:C17H16F3N5O, MW:363.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Specialized Applications and Modifications

STAR's alignment engine supports numerous specialized analysis scenarios through parameter adjustments and workflow modifications:

For stranded RNA-seq protocols, researchers can implement specific output options that preserve strand information through the --outSAMstrandField parameter, enabling correct attribution of reads to their transcriptional origin. This is particularly important for accurate quantification of antisense transcription and overlapping genes.

In clinical research contexts utilizing FFPE samples, STAR's precision advantages make it particularly valuable despite the challenges of degraded RNA. The aligner's ability to accurately map shorter fragments and its robust handling of sequencing artifacts compensates for some limitations of suboptimal sample preservation.

For large-scale consortia projects processing terabytes of RNA-seq data, recent optimizations demonstrate significant performance improvements. Cloud-based implementations with early stopping optimization can reduce total alignment time by 23%, while appropriate instance selection and spot instance usage provide additional cost efficiencies [15].

The integration of pseudoalignment tools like Salmon with STAR alignment represents an emerging hybrid approach that leverages STAR's precise junction detection for transcript quantification while maintaining computational efficiency. Such integrative strategies highlight STAR's continued relevance within evolving RNA-seq analytical ecosystems.

Integrated RNA-seq Analysis Workflow

STAR functions most effectively as part of a comprehensive RNA-seq analysis pipeline that begins with raw read processing and culminates in differential expression analysis. A robust workflow integrates multiple specialized tools, each optimized for specific analytical steps while maintaining data consistency across the entire pipeline.

A recommended integrated workflow begins with quality assessment using FastQC, followed by read trimming with fastp, which has demonstrated superior performance in enhancing data quality and improving subsequent alignment rates [6]. The alignment phase utilizes STAR with organism-appropriate parameters, generating BAM files sorted by coordinate. Downstream quantification can be performed using featureCounts to generate count matrices, followed by normalization and differential expression analysis with specialized tools like edgeR or DESeq2.

This integrated approach exemplifies the modern RNA-seq analysis paradigm where tool selection at each processing stage influences ultimate analytical outcomes. Studies comparing complete pipelines reveal that while most established tools produce generally concordant results, careful selection of analytical components based on specific experimental requirements—including sample type, sequencing characteristics, and biological questions—can optimize the accuracy and reliability of biological insights derived from transcriptomic data.

The transition from traditional genome aligners to modern pseudoalignment methods represents a significant paradigm shift in RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) data analysis. This evolution is driven by the competing demands for computational efficiency and analytical accuracy in modern transcriptomics, particularly as studies scale to encompass thousands of samples across multiple laboratories [16]. Traditional splice-aware aligners like STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) and HISAT2 (Hierarchical Indexing for Spliced Alignment of Transcripts) provide comprehensive alignment against reference genomes, while pseudoaligners such as Kallisto and Salmon use lightweight algorithms to directly quantify transcript abundance without generating base-by-base alignments [17]. Understanding the relative strengths, limitations, and optimal use cases for each approach is essential for researchers designing transcriptomic studies, especially in clinical and drug development contexts where both accuracy and throughput are critical.

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their methodological framework. Traditional aligners identify the precise genomic origin of each sequencing read, generating alignment files that facilitate both quantification and advanced analyses like novel isoform discovery [18]. In contrast, pseudoaligners employ k-mer matching or de Bruijn graphs to rapidly determine transcript compatibility, sacrificing positional alignment information for dramatic improvements in speed and reduced computational resources [17]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, supported by experimental data from benchmarking studies, to inform selection criteria for different research scenarios.

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons Across Platforms

Accuracy and Sensitivity Metrics

Multiple independent studies have systematically evaluated the performance of traditional aligners versus pseudoalignment methods using standardized datasets and ground truth references. In base-level resolution assessments using simulated Arabidopsis thaliana data, STAR demonstrated superior overall accuracy exceeding 90% under varied testing conditions, outperforming other traditional aligners like HISAT2 and SubRead [2]. However, for the specific task of junction base-level assessment, which critically impacts alternative splicing analysis, SubRead emerged as the most accurate tool with over 80% accuracy [2]. This indicates that performance characteristics are highly dependent on the specific analytical task, with different tools excelling in different domains.

For transcript isoform quantification, a comprehensive evaluation of seven quantification tools revealed that alignment-free methods provide competitive accuracy compared to traditional approaches. When assessed using RSEM-simulated data and experimental datasets from Universal Human Reference RNA (UHRR) and Human Brain Reference RNA (HBRR), Salmon and Kallisto demonstrated accuracy comparable to traditional methods like RSEM and Cufflinks while achieving dramatic speed improvements [17]. The robustness of these tools was confirmed through high correlation coefficients (typically R > 0.9) between technical replicates, indicating that the computational shortcuts employed by pseudoaligners do not substantially compromise quantification reliability for well-annotated transcripts.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of RNA-Seq Alignment and Quantification Tools

| Tool | Type | Base-Level Accuracy | Junction Detection Accuracy | Speed Relative to STAR | Memory Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR | Traditional aligner | ~90-95% [2] | Medium [2] | 1x (reference) [18] | High (≥32GB) [18] |

| HISAT2 | Traditional aligner | ~85-90% [2] | Medium [2] | ~2x faster than STAR [2] | Medium |

| SubRead | Traditional aligner | ~80-85% [2] | ~80-85% [2] | ~3x faster than STAR [2] | Low |

| Kallisto | Pseudoaligner | N/A | N/A | ~10-50x faster than STAR [17] | Low |

| Salmon | Pseudoaligner | N/A | N/A | ~10-50x faster than STAR [17] | Low |

| RSEM | Quantification (aligner-dependent) | N/A | N/A | ~0.5x slower than STAR [17] | Medium |

Computational Resource Requirements

The computational burden of RNA-Seq analysis varies dramatically between approaches, influencing tool selection for large-scale studies. Traditional aligners like STAR typically require substantial memory resources (often ≥32GB for human genomes) and processing time, though recent optimizations have improved scalability [18]. Cloud-based implementations of STAR have demonstrated efficient processing of tens to hundreds of terabytes of RNA-Seq data through parallelization and optimized resource allocation [18].

In contrast, pseudoaligners achieve remarkable efficiency gains by circumventing full alignment. Salmon and Kallisto typically process samples 10-50 times faster than traditional aligners with substantially reduced memory footprints [17]. This efficiency advantage makes pseudoalignment particularly valuable for large-scale meta-analyses or clinical applications requiring rapid turnaround. A benchmarking study noted that while traditional aligners provide more comprehensive output, the resource requirements can be prohibitive: "BBMap takes as much memory as the system provides" with minimum requirements of 24GB for human genomes [9].

Reproducibility Across Laboratories

Large-scale multi-center studies have revealed significant variability in RNA-Seq results depending on the analytical pipelines employed. The Quartet project, encompassing 45 laboratories using diverse RNA-Seq workflows, found that both experimental factors and bioinformatics pipelines introduce substantial variation in gene expression measurements [16]. Specifically, mRNA enrichment protocols, library strandedness, and each step in the bioinformatics workflow emerged as primary sources of inter-laboratory variation.

Importantly, the study found that detection of subtle differential expression was particularly variable across pipelines, with performance gaps between laboratories ranging from 4.7 to 29.3 based on signal-to-noise ratio measurements [16]. This has critical implications for clinical applications where detecting subtle expression differences between disease subtypes or treatment responses is essential. Consistency in pipeline application was identified as a key factor in achieving reproducible results, with the study recommending standardized workflows for cross-study comparisons.

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Benchmarking Approaches and Ground Truth Definitions

Robust evaluation of RNA-Seq methodologies requires carefully designed experiments with established ground truths. Current benchmarking approaches include:

Reference Materials: Large-scale consortia have developed well-characterized RNA reference materials, including the Quartet reference materials (derived from immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines) and MAQC samples [16]. These materials provide known transcriptional profiles for accuracy assessment.

Spike-in Controls: The External RNA Control Consortium (ERCC) provides synthetic RNA spikes at known concentrations that are added to samples before library preparation [16]. These enable absolute quantification accuracy measurements and normalization validation.

Experimental Datasets: Technical replicates from reference RNA samples (e.g., Universal Human Reference RNA and Human Brain Reference RNA) allow assessment of technical reproducibility [17].

Simulated Data: Tools like RSEM and Polyester generate in silico datasets with predetermined expression values, enabling precise accuracy calculations [17] [2]. Simulation parameters can be adjusted to model different sequencing depths, isoform ratios, and experimental artifacts.

The Quartet project's design exemplifies comprehensive benchmarking, incorporating multiple types of ground truth: "the Quartet reference datasets and the TaqMan datasets for Quartet and MAQC samples, and 'built-in truth' involving ERCC spike-in ratios and known mixing ratios" [16]. This multi-faceted approach enables robust cross-platform comparisons.

Standardized Processing Pipelines

To enable fair comparisons between tools, benchmarking studies typically implement standardized processing workflows. The Treehouse Childhood Cancer Initiative exemplifies this approach with their consistently processed compendia containing "gene expression data derived from 16,446 diverse RNA sequencing datasets" [19]. Their pipeline employs "the dockerized TOIL RNA-Seq pipeline" with quality assessment via the "MEND pipeline" to ensure uniform processing across datasets [19].

For traditional alignment workflows, a common reference is essential. Most benchmarking studies use "the human reference genome GRCh38 and the human gene models GENCODE" as standardized references [19]. Consistent annotation ensures that differences in quantification reflect algorithmic variations rather than annotation discrepancies.

Diagram 1: RNA-seq analysis workflow comparison. The workflow diverges after quality control, with traditional aligners and pseudoaligners following different paths to expression quantification.

Practical Implementation and Clinical Applications

Tool Selection Criteria for Different Research Scenarios

The optimal choice between traditional aligners and pseudoaligners depends on specific research objectives, experimental designs, and available resources:

Clinical Diagnostics Applications: For clinical settings requiring rapid turnaround, pseudoaligners offer significant advantages. The CARE IMPACT study demonstrated clinical utility of RNA-Seq analysis for pediatric cancers, with a median turnaround time of 20 days from sample collection to clinical report [20]. While this study employed comprehensive analysis including alignment-based approaches, the integration of faster quantification methods could further accelerate clinical implementation.

Large-Scale Consortia Studies: Projects integrating data from multiple sources benefit from standardized processing pipelines. The Treehouse Initiative successfully processed data from 50 sources by implementing "a dockerized, freely available pipeline" [19]. For such large-scale endeavors, computational efficiency must be balanced against analytical comprehensiveness.

Novel Organism Studies: For non-model organisms or studies focusing on novel transcript discovery, traditional aligners remain essential. As noted in plant pathogen studies, "different analytical tools demonstrate some variations in performance when applied to different species" [6], with traditional aligners providing more flexibility for detecting unannotated features.

Impact of Preprocessing and Normalization

The choice of alignment method interacts significantly with downstream preprocessing steps. A systematic evaluation of preprocessing pipelines found that "the choice of data preprocessing operations affected the performance of the associated classifier models" for tissue of origin prediction in cancer [21]. Specifically, batch effect correction improved performance when classifying against GTEx data but worsened performance against ICGC/GEO datasets [21], highlighting the context-dependent nature of optimal pipeline configuration.

Normalization strategies should be aligned with the quantification approach. While methods like TPM (Transcripts Per Million) can be derived from both alignment and pseudoalignment outputs, count-based differential expression tools typically require careful consideration of normalization factors that account for transcript length and compositional biases [17]. The evaluation of isoform quantification tools revealed that accuracy was particularly influenced by "the complexity of gene structures and caution must be taken when interpreting quantification results for short transcripts" [17].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Benchmarking

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in Evaluation | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Quartet RNA references [16], MAQC samples [16] | Provide ground truth for expression measurements | Well-characterized, homogeneous, stable |

| Spike-in Controls | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix [16] | Enable absolute quantification assessment | Known concentrations, cover dynamic range |

| Software Containers | Dockerized RNA-Seq pipeline [19] | Ensure reproducible processing across environments | Version-controlled, portable |

| Reference Annotations | GENCODE [19], Ensembl [17] | Standardized gene models for alignment and quantification | Comprehensive, regularly updated |

| Cloud Computing | AWS EC2 instances [18] | Enable scalable processing of large datasets | Configurable, cost-effective with spot instances |

The RNA-Seq analytical ecosystem has evolved to offer researchers multiple paths from sequencing reads to biological insights, with traditional aligners and pseudoaligners representing complementary rather than mutually exclusive approaches. Traditional aligners like STAR provide comprehensive genomic context necessary for novel isoform discovery, fusion detection, and variant calling, while pseudoaligners offer unprecedented efficiency for large-scale quantification studies [2] [17]. The optimal selection depends on research priorities: investigations requiring maximal biological discovery benefit from traditional alignment approaches, while large-scale differential expression studies can leverage pseudoaligners for rapid, resource-efficient analysis.

Future methodological developments will likely further blur the boundaries between these approaches, with traditional aligners incorporating efficiency optimizations and pseudoaligners expanding their functional capabilities. For clinical applications, standardization and reproducibility are paramount, with the Quartet project's recommendation for quality controls "at subtle differential expression levels" being particularly relevant [16]. As RNA-Seq continues to transition from basic research to clinical diagnostics, the strategic selection and consistent application of analytical workflows will be critical for generating reliable, actionable results in precision oncology and biomarker development.

Diagram 2: Decision framework for selecting RNA-seq analysis tools. This framework guides researchers to the most appropriate analytical approach based on their specific research requirements and constraints.

High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the primary method for transcriptome analysis, enabling discoveries in basic biology and drug development. A critical step in this process is read alignment, where sequenced fragments are mapped to a reference genome. The choice of alignment tool and the overall bioinformatics pipeline significantly impacts the accuracy, reproducibility, and scalability of results. This guide provides an objective comparison of the STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) RNA-seq workflow against other prominent pipelines, synthesizing evidence from large-scale, multi-center benchmarking studies to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Performance Comparison of RNA-seq Pipelines

Large-scale consortium-led projects have systematically evaluated RNA-seq performance. The table below summarizes key findings on pipeline performance from recent major studies.

Table 1: Key RNA-seq Benchmarking Studies and Their Findings on Pipeline Performance

| Study/Project | Scale | Primary Focus | Key Findings on Pipeline Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartet Project [16] | 45 labs, 140 analysis pipelines | Accuracy in detecting subtle differential expression | Found greater inter-laboratory variation for subtle expression changes; experimental factors and each bioinformatics step are primary variation sources. |

| SEQC/MAQC-III [22] | >100 billion reads, multiple platforms | Cross-platform/site reproducibility and accuracy | RNA-seq provides highly reproducible results for differential expression; measurement performance depends on platform and data analysis pipeline. |

| Corchete et al. [23] | 192 pipelines, 18 samples | Precision and accuracy of gene expression quantification | Identified top-performing pipelines for raw gene expression quantification; performance varied significantly across different method combinations. |

| Gupta et al. [11] | Tool comparison at each step | Best practices for pipeline construction | Noted that no single tool is best for all scenarios; recommendations provided for each analytical step. |

Accuracy and Reproducibility Metrics

Accuracy in RNA-seq is measured by the ability to recover "ground truth" expression differences, often defined by spike-in controls (e.g., ERCC RNAs) [16] [22] or sample mixtures with known ratios [22]. Reproducibility, or precision, is measured by the consistency of results across technical replicates, sequencing lanes, and different laboratories.

The Quartet project emphasized that detecting subtle differential expression—small expression changes between biologically similar samples, as often seen in clinical subtypes—is particularly challenging and highly dependent on the analysis pipeline [16]. In real-world scenarios involving 45 laboratories, inter-laboratory variations were significant for these subtle changes, whereas pipelines performed more consistently when analyzing samples with large biological differences.

Comparative Performance of STAR and Alternative Workflows

Alignment and Quantification Tools

The alignment step is foundational, influencing all downstream results. STAR is a widely used aligner designed specifically for RNA-seq data.

Table 2: Comparison of RNA-seq Alignment and Quantification Tools

| Tool | Category | Key Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAR [24] | Spliced aligner | Ultrafast, detects annotated/novel splice junctions, outputs data for downstream analysis. | High alignment rate and accuracy; recommended in benchmarking studies [16]. |

| HiSat2 [11] | Spliced aligner | Fast, low memory requirements, successor to TopHat2. | Fastest aligner in some comparisons; performs well with unmapped reads [11]. |

| BWA [11] | Aligner | Algorithm for mapping low-divergent sequences. | Reported highest alignment rate and coverage in some studies [11]. |

| Kallisto/Salmon [11] [23] | Pseudoaligner | Quantification via pseudoalignment and lightweight algorithm. | Similar precision and accuracy; faster than alignment-based methods [11]. |

Differential Expression Analysis Tools

Differential expression (DE) analysis is a primary goal of many RNA-seq studies. Different tools use distinct statistical models to call differentially expressed genes (DEGs).

Table 3: Comparison of Differential Gene Expression (DGE) Tools

| DGE Tool | Statistical Model / Basis | Key Characteristics | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| NOISeq [25] | Non-parametric | Robust to variations in sequencing depth and sample size. | Most robust in comparative studies, followed by edgeR and voom [25]. |

| edgeR [11] [25] | Negative binomial | Uses TMM normalization; part of Bioconductor project. | Ranked among top tools for accuracy; high robustness [11] [25]. |

| limma-voom [11] [25] | Linear modeling | Adapts microarray methods for RNA-seq data (voom transformation). | High accuracy and robustness; performs well in multiple comparisons [11] [25]. |

| DESeq2 [25] | Negative binomial | Uses median-based normalization method (RLE). | Widely used but shown to be less robust in some comparisons [25]. |

| baySeq [11] | Empirical Bayesian | Estimates posterior probability of differential expression. | Ranked as best overall tool in one comparison for multiple parameters [11]. |

| Cuffdiff [11] | Transcript-level | Part of the Tuxedo suite for isoform-level analysis. | Generates the least number of DEGs [11]. |

Integrated Pipeline Performance

No single tool operates in isolation; performance depends on the entire workflow. A study comparing 288 pipelines for fungal data analysis found that tool performance can vary when applied to different species, underscoring the need for careful pipeline selection based on the organism and research question [6]. Another systematic comparison of 192 pipelines applied to human cell lines identified specific optimal combinations for raw gene expression quantification [23].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized high-performance RNA-seq analysis workflow, integrating top-performing tools as identified in the cited studies.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure robust and reproducible pipeline comparisons, benchmarking studies follow rigorous experimental designs.

Reference Materials and Ground Truth

The most reliable benchmarking studies use reference samples with built-in controls:

- MAQC Reference Samples: Universal Human Reference RNA (UHRR) and Human Brain Reference RNA (HBRR) with known differential expression profiles [22].

- Quartet Project Reference Materials: RNA from immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines from a Chinese quartet family, providing samples with small, clinically relevant biological differences [16].

- Spike-in Controls: Synthetic RNA controls from the External RNA Control Consortium (ERCC) are spiked into samples in known concentrations to provide an absolute metric for accuracy [16] [22].

- Sample Mixtures: MAQC samples A (UHRR) and B (HBRR) are mixed in known ratios (3:1, 1:3) to create additional samples with defined expression fold-changes [22].

Multi-Laboratory Study Design

The Quartet project exemplifies a comprehensive approach: providing identical RNA samples to 45 independent laboratories, each using their in-house experimental protocols and bioinformatics pipelines [16]. This design captures real-world technical variation and allows researchers to disentangle sources of variability arising from wet-lab procedures versus computational analysis.

Performance Assessment Metrics

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Calculated based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to measure the ability to distinguish biological signals from technical noise [16].

- Accuracy of Expression Measurements: Assessed by correlation with orthogonal validation data, such as TaqMan qPCR assays or known spike-in concentrations [16] [23].

- Reproducibility: Measured by consistency between technical replicates and across different testing sites [22].

- Accuracy of Differential Expression: Evaluated by the ability to recover known differentially expressed genes between reference samples and to control false discovery rates [16] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Benchmarking

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Pipeline Evaluation | Example Sources/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference RNA Samples | Provide biologically defined materials with known expression relationships for accuracy assessment. | MAQC UHRR & HBRR [22]; Quartet Project reference materials [16] |

| ERCC Spike-in Controls | Synthetic RNA mixes with known concentrations to create absolute ground truth for quantification. | Available from commercial vendors; 92 distinct sequences [16] [22] |

| Stranded cDNA Libraries | Preserve transcript orientation information, improving accuracy of transcript assignment. | Various commercial kits; important for detecting overlapping genes [26] |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kits | Remove abundant rRNA to increase informative sequencing reads, critical for non-polyA RNAs. | Both probe-based and RNase H-mediated methods available [26] |

| RNA Integrity Assessment | Evaluate RNA quality; crucial for obtaining reliable results. | RIN >7 generally recommended; Agilent Bioanalyzer/TapeStation [26] |

| Mini gastrin I, human tfa | Mini gastrin I, human tfa, MF:C76H102F3N15O28S, MW:1762.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Gavestinel sodium salt | Gavestinel sodium salt, MF:C18H11Cl2N2NaO3, MW:397.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Defining pipeline performance in RNA-seq requires a multi-faceted approach considering accuracy, reproducibility, and scalability. Evidence from large-scale benchmarking studies indicates that the STAR aligner consistently demonstrates high performance in alignment accuracy and splice junction detection. For differential expression, non-parametric methods like NOISeq and negative binomial-based methods like edgeR and limma-voom show superior robustness. The optimal pipeline combination depends on the biological question, with studies requiring detection of subtle expression differences needing particularly rigorous standardization. As RNA-seq moves toward clinical applications, continued pipeline optimization and standardization using well-characterized reference materials will be essential for generating reliable, actionable results in drug development and clinical diagnostics.

From Raw Reads to Results: Implementing and Comparing RNA-seq Pipelines

This guide provides an objective comparison of the standard alignment-based RNA-seq workflow, with a focus on the STAR aligner, against other modern pipelines. Performance data and methodologies from recent studies are synthesized to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their analysis choices.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the primary method for transcriptome analysis, enabling the detailed study of gene expression patterns across different biological conditions. The analysis of RNA-seq data typically follows one of two principal computational strategies: the standard alignment-based workflow or the pseudoalignment-based workflow. The alignment-based approach, which involves mapping sequencing reads to a reference genome before quantification, is renowned for its high accuracy and reliability, particularly for detecting novel splice variants and genomic features. Within this paradigm, the STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) aligner has emerged as a widely adopted tool due to its high accuracy and unique splice-aware algorithm. However, the landscape of bioinformatics tools is rich with alternatives, each with distinct performance characteristics in terms of speed, computational resource consumption, and accuracy. This guide objectively compares the STAR-centric workflow against other popular aligners and pipelines, drawing on recent benchmarking studies and performance analyses to provide a data-driven foundation for pipeline selection in research and drug development contexts.

The standard alignment-based workflow for RNA-seq data analysis is a multi-stage process that transforms raw sequencing reads into interpretable gene expression counts. The following diagram illustrates the key steps and the tools commonly available for each stage.

Detailed Workflow Steps

Trimming and Quality Control: The initial step involves processing raw sequencing reads to remove adapter sequences, poly-A tails, and low-quality nucleotides. This is crucial for increasing the subsequent mapping rate and the reliability of downstream analysis while reducing computational requirements. Tools like fastp and Trim Galore are commonly used; fastp is noted for its rapid analysis and operational simplicity, while Trim Galore integrates Cutadapt and FastQC for comprehensive quality control in a single step [6].

Read Alignment: Processed reads are aligned to a reference genome using splice-aware aligners. This is the most computationally intensive step. STAR utilizes a two-step strategy of seed searching followed by clustering, stitching, and scoring to efficiently identify aligned regions, including across splice junctions [13]. Alternative aligners like HISAT2 and TopHat2 employ different algorithms and have varying performance profiles.

Quantification: After alignment, the number of reads mapped to each genomic feature (e.g., gene or transcript) is counted. Tools like featureCounts (from the Subread package) and HTSeq-Count are frequently used for this purpose [27]. This step generates the count matrix that serves as the input for differential expression analysis.

Differential Expression Analysis: Finally, statistical models are applied to the count data to identify genes that are significantly differentially expressed between biological conditions. Tools like DESeq2 and edgeR are standard for this stage, employing robust normalization methods to account for technical variability [11].

Performance Comparison of Alignment Tools

Alignment Performance Metrics

The choice of an aligner significantly impacts the results and resource consumption of an RNA-seq pipeline. The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of popular alignment tools based on published comparisons and user manuals.

| Tool | Alignment Strategy | Speed | Memory Usage | Key Strengths | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR [13] | Seed search, clustering/stitching | Fast (outperforms others by >50x) [13] | High (tens of GiBs for large genomes) [13] [18] | High accuracy, splice-aware, ideal for novel junction detection [13] | Memory-intensive; requires significant computational resources [13] |

| HISAT2 [11] | Graph-based FM index | Very Fast [11] | Low [11] | Fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements [11] | May perform slightly worse than STAR for unmapped reads [11] |

| TopHat2 [28] | Based on Bowtie 2 | Slower on large datasets [28] | Moderate | Good for detecting novel splice junctions [28] | Lacks advanced features of newer tools; can be slower [28] |

| BWA [11] | Burrows-Wheeler Transform | Moderate | Moderate | High alignment rate and coverage [11] | Not specifically designed for spliced RNA-seq reads [11] |

Experimental Data from Benchmarking Studies

Large-scale, multi-center studies provide "real-world" performance data for these tools. One such study, part of the Quartet project, analyzed 140 different bioinformatics pipelines across 45 laboratories. It found that the choice of genome alignment tool was a primary source of variation in gene expression measurements, significantly impacting the accuracy of downstream differential expression analysis [16]. This underscores the importance of aligner selection for reproducible results.

Another comprehensive study evaluating tools for plant pathogenic fungal data also highlighted that performance can vary significantly when applied to different species, suggesting that the optimal aligner may depend on the specific biological context and organism under study [6].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful execution of a computational RNA-seq workflow relies on several key components. The following table details essential "research reagents" for the bioinformatician.

| Item | Function in the Workflow | Example Sources/Formats |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | Serves as the foundational scaffold for the alignment process, providing a comprehensive representation of the species' genetic material [18]. | FASTA file (e.g., from Ensembl, UCSC, or NCBI) [13]. |

| Gene Annotation File | Provides the coordinates of genomic features (genes, exons, transcripts) required for the quantification of aligned reads. | GTF or GFF3 file (e.g., from Ensembl or RefSeq) [13]. |

| STAR Genome Index | A precomputed data structure required by STAR for efficient alignment. It must be generated from the reference genome and annotation files [13]. | Directory with binary index files, generated using STAR --runMode genomeGenerate [13]. |

| SRA Toolkit [18] | A collection of tools for accessing and handling RNA-seq files stored in the NCBI SRA database. | Includes prefetch to download SRA files and fasterq-dump to convert them to FASTQ format [18]. |

| Quality Control Reports | Assesses the quality of raw sequencing data and the success of the trimming step, informing decisions on downstream processing. | HTML reports generated by FastQC or fastp [6] [27]. |

| Lenalidomide-C4-NH2 hydrochloride | Lenalidomide-C4-NH2 hydrochloride, MF:C17H22ClN3O3, MW:351.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflow Steps

Generating a STAR Genome Index

Before alignment, STAR requires a genome index to be generated. The following command provides a standard protocol for index creation [13].

Parameter Explanation:

--runThreadN 6: Specifies the number of CPU threads to use.--runMode genomeGenerate: Instructs STAR to run in genome index generation mode.--genomeDir: Path to the directory where the genome indices will be stored.--genomeFastaFiles: Path to the reference genome FASTA file.--sjdbGTFfile: Path to the annotation file in GTF format.--sjdbOverhang: This crucial parameter should be set to (read length - 1). It specifies the length of the genomic sequence around annotated junctions used for constructing the splice junction database [13].

Performing Read Alignment with STAR

Once the index is built, reads can be aligned. The command below demonstrates the alignment of a single sample [13].

Parameter Explanation:

--readFilesIn: Input FASTQ file(s). For paired-end reads, provide two files.--outFileNamePrefix: Path and prefix for all output files.--outSAMtype BAM SortedByCoordinate: Outputs the alignment as a BAM file, sorted by genomic coordinate, which is the standard input for many downstream tools.--outSAMunmapped Within: Keeps information about unmapped reads within the output BAM file.--quantMode GeneCounts: An optional but useful parameter that directs STAR to also output read counts per gene, as defined in the supplied GTF file, integrating the quantification step directly into the alignment process [3].

Comparison with Alternative Pipelines

Pseudoalignment and Quantification Pipelines

A major alternative to the standard alignment-based workflow is the pseudoalignment pipeline, which combines alignment, counting, and normalization into a single step. Tools like Kallisto and Salmon are leading this category [11].

Performance and Characteristics:

- Speed and Cost: Pseudoaligners are significantly faster and less computationally intensive than alignment-based tools like STAR. Research has shown they are recommended when cost and speed play a critical role [18].

- Accuracy: When compared, Kallisto, Salmon, and Sailfish showed similar performance in terms of precision and accuracy for transcript-level quantification [11].

- Pros: Faster (due to the lack of a full alignment step) and capable of quantifying known isoforms [3].

- Cons: The generated expression values are considered more abstract and less easy to explain than simple read counts. Gene-level analysis requires extra work to aggregate transcript-level counts [3].

Integrated Quantification Tools

Even within the alignment-based workflow, there are choices for the quantification step after using STAR.

- STAR's

--quantMode: This is a convenient option that provides gene counts during alignment, similar to HTSeq-Count output. It is straightforward but less sophisticated in handling ambiguous reads [3]. - RSEM (RNA-Seq by Expectation-Maximization): RSEM is a separate, alignment-based quantification tool that is "smarter about dealing with ambiguous reads." It can use the BAM file generated by STAR as input. Results from RSEM are often considered superior for isoform-level quantification, though it is slower than pseudoaligners [3].

- featureCounts: This tool is known for its high efficiency in counting reads mapped to genomic features. Studies have indicated that pipelines using StringTie (for transcript assembly) combined with featureCounts (for quantification) rank highly in performance comparisons [11] [27].

The choice between the standard STAR alignment workflow and its alternatives involves a fundamental trade-off between analytical depth and computational efficiency. The STAR-centric pipeline is ideal for projects where the discovery of novel splice variants, high accuracy, and comprehensive genomic context are priorities, and where sufficient computational resources (particularly memory) are available. In contrast, pseudoalignment tools like Kallisto and Salmon offer a compelling solution for projects with limited computational time or cost, or when the primary goal is rapid differential expression analysis of known transcripts.

Based on the synthesized data, for researchers requiring the robustness of full alignment, a best-practice, high-accuracy pipeline would involve using STAR for alignment followed by RSEM or featureCounts for quantification. This combination leverages STAR's superior alignment capabilities while utilizing a dedicated, accurate tool for the final counting step [11] [3]. Ultimately, the selection of tools should be guided by the specific research objectives, the biological system under investigation (e.g., human, plant, fungus), and the available computational infrastructure [6].

In the context of RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, the STAR aligner represents a powerful and accurate traditional alignment-based method for mapping reads to a reference genome [18]. However, for the fundamental task of transcript quantification—estimating the abundance of RNA transcripts—researchers now have access to a faster, more efficient class of tools known as pseudoaligners. Kallisto and Salmon are the leading tools in this category, employing a fundamental shift in methodology that bypasses base-by-base alignment [29] [30]. Instead of determining the exact genomic coordinates of each read, these tools use pseudoalignment or quasi-mapping to rapidly identify the set of transcripts from which a read could have originated, focusing solely on transcript compatibility for quantification [31] [32]. This approach offers dramatic speed improvements while maintaining, and in some cases enhancing, accuracy compared to traditional alignment-based quantification pipelines, making them particularly valuable for large-scale studies and precision medicine applications where both throughput and reliability are paramount [33].

Kallisto: Pioneer of Pseudoalignment

Kallisto, introduced by Bray et al. in 2016, pioneered the pseudoalignment approach for transcript quantification [31]. Its core innovation is the use of k-mer based pseudoalignment via the transcriptome de Bruijn graph (T-DBG) to quickly determine read-transcript compatibility without performing costly nucleotide-level alignment [29]. This method allows Kallisto to process tens of millions of reads in mere minutes on standard desktop hardware, offering exceptional speed and resource efficiency [31] [29]. The tool groups reads into equivalence classes—sets of reads that map to the same set of transcripts—which simplifies the underlying quantification model and accelerates computation [29]. Kallisto outputs transcript abundance estimates in units of transcripts per million (TPM) and estimated counts, which can be directly used for downstream differential expression analysis [1].

Salmon: Bias-Aware Quantification

Salmon, developed by Patro et al., shares the speed advantages of lightweight mapping but incorporates a more complex, multi-phase inference procedure to account for various technical biases present in RNA-seq data [32] [34]. While it employs a rapid quasi-mapping procedure similar to pseudoalignment, its distinguishing feature is the implementation of sample-specific bias models that correct for sequence-specific bias, fragment GC-content bias, and positional bias [34]. Salmon operates in two phases: an online phase that estimates initial expression levels and model parameters, and an offline phase that refines these estimates using an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm over rich equivalence classes [34]. This sophisticated modeling allows Salmon to provide highly accurate abundance estimates that are robust to common experimental artifacts, potentially leading to fewer false positives in differential expression studies [34].

Comparative Analysis: Features and Performance

Feature Comparison

Table 1: Core Feature Comparison of Kallisto and Salmon

| Feature | Kallisto | Salmon |

|---|---|---|

| Core Algorithm | Pseudoalignment via T-DBG [29] | Quasi-mapping with dual-phase inference [34] |

| Bias Correction | Basic models | Comprehensive (sequence, GC, positional) [34] |

| Input Flexibility | FASTQ files | FASTQ, BAM, or SAM files [29] |

| Strandedness Support | Yes (updated) [29] | Yes [29] |

| Output Metrics | TPM, estimated counts [1] | TPM, estimated counts |

| Companion Tools | Sleuth for differential expression [29] | Wasabi for Sleuth compatibility [29] |

| Computational Footprint | Very lightweight [30] | Lightweight with higher memory for bias models [34] |

Performance and Benchmarking Data

Experimental comparisons between Kallisto and Salmon reveal nuanced performance differences. In benchmark studies using standard RNA-seq data, both tools demonstrate remarkably fast processing times, significantly outperforming traditional alignment-based workflows.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks on Standard RNA-seq Data

| Metric | Kallisto | Salmon | STAR + Cufflinks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time (22M PE reads) | ~3.5 minutes [29] | ~8 minutes [29] | Substantially longer [29] |

| Memory Usage | Low [1] | Moderate [34] | High [18] |

| Accuracy (vs Cufflinks) | r = 0.941 [29] | r = 0.939 [29] | Baseline |

| Differential Expression | High sensitivity [29] | Higher sensitivity, fewer false positives [34] | Standard |

Salmon's bias correction capabilities provide measurable advantages in specific scenarios. In differential expression analysis, Salmon has demonstrated 53% to 250% higher sensitivity at the same false discovery rates compared to Kallisto and eXpress, while also producing fewer false-positive calls in comparisons expected to contain few true expression differences [34]. Salmon also significantly reduces instances of erroneous isoform switching—cases where different tools predict different dominant isoforms between samples—particularly for genes with moderate to high GC content [34].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standardized Workflow for Tool Evaluation

To ensure fair and reproducible comparison between Kallisto and Salmon in the context of broader STAR workflow evaluations, researchers should follow standardized experimental protocols. The fundamental workflow begins with quality control of raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files) using tools like FastQC, followed by adapter trimming if necessary. The subsequent quantification steps differ slightly between tools but follow the same general principles.

Kallisto Quantification Protocol:

- Indexing: Build a Kallisto index from a reference transcriptome in FASTA format.

- Quantification: Run the quantification process on sequencing reads.

The

-b 100flag generates 100 bootstrap samples for uncertainty estimation in downstream tools like Sleuth [29].

Salmon Quantification Protocol:

- Indexing: Build a Salmon index from the reference transcriptome.

- Quantification: Execute quantification with appropriate library type specifications.

Here,

-l ISRspecifies a stranded library type where read 1 comes from the reverse strand [29].

For comprehensive benchmarking, results should be compared against a STAR-based workflow where reads are first aligned to the genome with STAR, followed by transcript quantification using a tool like Cufflinks or HTSeq [18] [1].

Workflow Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for RNA-seq Quantification

| Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Sources/Formats |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Transcriptome | Set of known transcripts for quantification | ENSEMBL, GENCODE (FASTA format) [29] |

| Reference Genome | Genome sequence for alignment-based methods | ENSEMBL, UCSC (FASTA format) [18] |

| RNA-seq Reads | Experimental data for quantification | FASTQ files (paired-end/single-end) [29] |

| Alignment Files | Pre-aligned reads for Salmon BAM input | BAM/SAM files [29] |

| Kallisto Index | Pre-processed transcriptome for rapid pseudoalignment | Output of kallisto index [29] |

| Salmon Index | Pre-processed transcriptome for quasi-mapping | Output of salmon index [29] |

| STAR Genome Index | Pre-processed genome for STAR alignment | Output of STAR --runMode genomeGenerate [18] |

| Strandedness Information | Critical parameter for accurate quantification | Library type specification (e.g., ISR) [29] |

Within the broader comparison of STAR RNA-seq workflows, Kallisto and Salmon present compelling alternatives for researchers focused specifically on transcript quantification. The choice between these tools depends on experimental priorities and resource constraints.

Kallisto is recommended when maximum speed and computational efficiency are paramount, such as in large-scale screening studies, exploratory analyses, or environments with limited computational resources [29] [1]. Its straightforward implementation and minimal parameter tuning make it accessible for users seeking rapid results without complex configuration.

Salmon excels in scenarios requiring maximum quantification accuracy and robust handling of technical biases, particularly in sensitive applications like clinical biomarker discovery or precision oncology where accurate detection of expression differences is critical [33] [34]. Its sophisticated bias models make it more suitable for datasets with notable technical artifacts or when analyzing genes with extreme GC content.

Both tools integrate effectively into broader RNA-seq analysis ecosystems through companion tools like Sleuth for differential expression analysis, enabling researchers to move rapidly from raw sequencing data to biological insights while maintaining analytical rigor [29]. For modern transcriptomics, particularly in drug development and clinical applications where both throughput and reliability are essential, these pseudoalignment tools offer a powerful alternative to traditional alignment-based quantification within comprehensive STAR workflows.

A critical phase in any RNA-seq workflow is the bridge between aligning sequencing reads and performing statistical analysis for differential expression (DE). Selecting the optimal pipeline, which often involves pairing a splice-aware aligner like STAR with a robust DE tool such as DESeq2, edgeR, or limma-voom, is paramount for generating accurate, biologically meaningful results. This guide objectively compares the performance of these integrated pipelines, drawing on large-scale benchmarking studies to provide evidence-based recommendations for researchers and drug development professionals.

From Aligned Reads to a Count Matrix

The immediate output of any aligner, including STAR, is a BAM file containing the genomic coordinates of each read. To perform DE analysis with count-based methods, these alignments must be quantified to generate a gene-by-sample count matrix.

- Core Quantification Tools: The most common tools for this step are featureCounts (from the Subread package) and HTSeq. [35] [5] These tools take the BAM file and a reference annotation file (GTF/GFF) and count the number of reads overlapping each gene feature.

- STAR's Integrated Quantification: STAR can optionally perform read counting internally using the

-quantMode GeneCountsparameter, which streamlines the workflow by generating counts during alignment. [18] - Alignment-Free Alternatives: Pseudo-aligners like Salmon and Kallisto offer a powerful alternative by bypassing traditional alignment. They directly estimate transcript abundances from raw reads using k-mers and a reference transcriptome, often with greater speed and reduced memory requirements. [35] [5] While they do not use BAM files, their output (estimated counts) can be imported into DESeq2 or edgeR, making them a viable part of a modern DE pipeline. [35]

The following diagram illustrates the primary workflows for connecting alignment output to differential expression analysis.

Benchmarking Pipeline Performance

Large-scale consortium studies and independent benchmarking efforts have systematically evaluated the accuracy and reproducibility of RNA-seq pipelines. The table below summarizes key findings on how different tool combinations perform in real-world scenarios.

| Analysis Stage | Tool/Metric | Performance Summary | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment | STAR | High accuracy and alignment rate; fast but memory-intensive. [5] [18] | A multi-center study found STAR to be a well-established and accurate aligner, though it requires substantial RAM. [18] |

| Alignment | HISAT2 | Competitive accuracy with a significantly smaller memory footprint than STAR; ideal for constrained compute environments. [5] | Benchmarks show HISAT2 offers a balanced compromise between memory usage and accuracy. [5] |