Uncharted Epigenetic Territories: A Guide to Methylation Analysis in Non-Model Organisms

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals embarking on DNA methylation studies in non-model organisms.

Uncharted Epigenetic Territories: A Guide to Methylation Analysis in Non-Model Organisms

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals embarking on DNA methylation studies in non-model organisms. It covers the foundational principles of epigenetic exploration in species lacking extensive genomic resources, detailing cutting-edge methodologies from non-invasive sampling to AI-driven analysis. The content addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes rigorous frameworks for data validation and cross-species comparison. By synthesizing recent technological advances and analytical strategies, this guide aims to empower the scientific community to unlock the vast, untapped potential of non-model organisms for evolutionary biology, biomarker discovery, and clinical insights.

The Unexplored Epigenome: Establishing Foundational Methylation Principles in Non-Model Systems

The field of epigenetics has traditionally been dominated by research on a limited number of model organisms, such as mice, fruit flies, and the Arabidopsis plant. However, evolution has yielded an amazing array of biological traits and capabilities across the tree of life that remain largely unexplored [1]. Non-model organisms—species not traditionally established in laboratory settings—represent an untapped frontier for epigenetic research. These organisms often possess unique biological features, occupy diverse ecological niches, and hold distinctive positions in the evolutionary tree, offering unparalleled opportunities to understand the fundamental principles of epigenetic regulation beyond conventional models [1]. The study of DNA methylation patterns in non-model organisms is particularly promising for revealing how environmental interactions shape genomes and influence phenotypic diversity.

This technical guide examines the emerging opportunities and significant challenges in studying epigenetic mechanisms, with a particular focus on DNA methylation, in non-model organisms. Framed within the context of a broader thesis on methylation patterns and exploratory analysis, this review provides researchers with methodological frameworks, analytical tools, and practical considerations for advancing epigenetics beyond traditional model systems. By leveraging innovative technologies and adapted protocols, scientists can now explore epigenetic phenomena in organisms ranging from marine algae to wild primates, potentially transforming our understanding of gene regulation, environmental adaptation, and evolutionary processes.

Defining Non-Model Organisms in Epigenetic Research

Characteristics and Scientific Value

Non-model organisms in epigenetic research are typically characterized by several key attributes: the absence of established laboratory cultivation methods, lack of high-quality reference genomes, and limited availability of genetic and molecular tools [2] [1]. Despite these limitations, they offer exceptional scientific value for epigenetic studies. For instance, the green macroalga Ulva mutabilis, a marine species with remarkably high global DNA methylation levels, provides insights into how epigenetic mechanisms operate in densely methylated genomes and in response to bacterial symbionts [2]. Similarly, wild capuchin monkeys enable the study of age-associated epigenetic changes in natural environments, revealing how social and ecological factors shape DNA methylation patterns throughout life [3].

The distinctive biological traits found in non-model organisms are particularly valuable for understanding epigenetic regulation. Regenerative species like planarians and apple snails offer models for studying epigenetic control during complete tissue and organ regeneration [1]. Long-lived species such as bats, naked mole-rats, and certain fish varieties provide opportunities to investigate epigenetic correlates of longevity and negligible senescence. Similarly, extremophiles that thrive in harsh environments (e.g., high salinity, temperature extremes, or toxic conditions) can reveal how epigenetic mechanisms facilitate rapid environmental adaptation without genetic changes.

Comparative Epigenetics and Evolutionary Insights

Comparative studies across diverse non-model species are crucial for understanding the evolution of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms [4]. By examining DNA methylation patterns in species with different evolutionary histories, life history strategies, and ecological adaptations, researchers can distinguish conserved epigenetic features from lineage-specific innovations. For example, plants exhibit DNA methylation in three sequence contexts (CG, CHG, and CHH, where H represents A, T, or C), while animals predominantly show methylation at CG dinucleotides [4]. Such comparative approaches reveal how epigenetic machinery has been adapted to different genomic environments and biological needs across the tree of life.

Methodological Approaches for DNA Methylation Analysis in Non-Model Organisms

Global Methylation Analysis Techniques

For non-model organisms where reference genomes may be incomplete or unavailable, global methylation analysis provides a valuable alternative to locus-specific methods. These approaches quantify overall methylation levels without requiring positional information, making them particularly suitable for initial epigenetic characterization.

Acid Hydrolysis with Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry: This method employs highly efficient acid hydrolysis of DNA followed by liquid chromatography and high-resolution mass spectrometry detection to accurately quantify methyl-modified nucleobases (5-methylcytosine and 6-methyladenine) along with their unmodified counterparts [2]. The protocol involves hydrolyzing DNA with hydrochloric acid, which releases methylated and unmethylated nucleobases that are then separated by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) and detected by Orbitrap mass spectrometry. This approach enables direct, rapid, cost-efficient, and sensitive quantification requiring only small amounts of DNA [2]. Unlike sequencing techniques, it provides quantitative information on the overall degree of methylation without depending on lengthy bioinformatic analyses, making it ideal for rapid methylome screening and comparison across biological contexts [2].

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) of Hydrolyzed DNA: Similar in principle to the acid hydrolysis method, LC-MS-based approaches analyze hydrolyzed DNA nucleosides or nucleobases, allowing detection of any DNA modification and absolute quantification independent of sequence context [2]. While enzymatic hydrolysis is more common, it faces efficiency constraints with highly methylated DNA, whereas the chemical hydrolysis approach avoids enzyme-related limitations including matrix effects and nucleoside background [2].

Table 1: Global DNA Methylation Analysis Methods for Non-Model Organisms

| Method | Resolution | DNA Input | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acid Hydrolysis + Orbitrap MS | Global | Low (nanogram scale) | Sequence-independent; absolute quantification; detects various modifications | No locus-specific information |

| LC-MS of Hydrolyzed DNA | Global | Low to moderate | Broad modification detection; quantitative | No genomic context |

| Luminometric Methylation Assay (LUMA) | Global | Moderate | Cost-effective; high-throughput | Limited to CG methylation; requires specific restriction sites |

| Immunochemical Detection | Global | Low | Simple workflow; low-cost | Semi-quantitative; antibody specificity issues |

Bisulfite Sequencing and Adaptations for Non-Model Systems

Bisulfite sequencing remains the gold standard for DNA methylation detection at single-base resolution, with several adaptations making it suitable for non-model organisms.

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS): This approach provides the most comprehensive view of cytosine methylation, covering nearly all CpG sites in the genome [5]. For non-model organisms, WGBS offers the advantage of not requiring prior genomic annotation, as it detects methylation patterns across the entire genome. However, it demands high sequencing depth (>30× for diploid methylation calling) and suffers from bisulfite-induced DNA degradation, which reduces sequence complexity and complicates alignment [5]. The technique is particularly challenging for non-model organisms with large or complex genomes where reference sequences may be incomplete.

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS): RRBS offers a cost-effective alternative to WGBS by focusing sequencing efforts on CpG-rich regions through methylation-insensitive restriction enzyme digestion (typically MspI) and size selection [5]. This method enables efficient profiling of approximately 4 million CpG sites in mammalian genomes, making it well-suited for large-cohort studies and non-model organisms [5]. However, RRBS has limitations in genome coverage, excluding distal enhancers, low-CpG-density intergenic regions, and repetitive elements that may harbor functionally relevant methylation changes [5]. Its dependence on restriction sites also introduces sequence bias.

Epigenotyping-by-Sequencing (epiGBS): This RRBS-based method enables methylation analysis without relying on a reference genome, making it highly applicable in ecological studies of non-model plant species [5]. By combining restriction enzyme digestion with bisulfite conversion and subsequent sequencing, epiGBS allows for simultaneous SNP discovery and methylation analysis in populations without prior genomic information.

Emerging Technologies for Epigenetic Profiling

Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq): This bisulfite-free method uses the TET2 enzyme to convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-carboxylcytosine and APOBEC to deaminate unmodified cytosines, thereby preserving DNA integrity and reducing sequencing bias [6]. EM-seq demonstrates high concordance with WGBS while offering improved CpG detection and lower DNA input requirements [6]. For non-model organisms, its gentler treatment of DNA can yield higher-quality data from suboptimal samples.

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) Sequencing: This third-generation sequencing approach directly detects DNA modifications including 5mC and 5hmC through deviations in electrical signals as DNA passes through protein nanopores [6]. The technology benefits from long-read sequencing, enabling resolution of highly repetitive genomic regions that are challenging for short-read methods [6]. For non-model organisms, ONT allows for simultaneous genome assembly and methylation calling, though it requires relatively high DNA amounts (approximately 1μg of 8kb fragments) [6].

Table 2: Genome-Wide Methylation Profiling Methods for Non-Model Organisms

| Method | Resolution | Genomic Coverage | Input DNA | Pros for Non-Models | Cons for Non-Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGBS | Single-base | ~80% of CpGs | High (μg) | No prior annotation needed | Expensive; complex analysis |

| RRBS | Single-base | CpG-rich regions | Moderate | Cost-effective; focused on functional regions | Reference bias; incomplete coverage |

| EM-seq | Single-base | Comprehensive | Low to moderate | Gentle on DNA; high accuracy | Enzymatic cost; protocol complexity |

| Nanopore | Single-base | Comprehensive | High (μg) | Long reads; direct detection | High error rate; computational demands |

| Methylation Arrays | Probe-based | Predefined sites | Low | Cost-effective for large cohorts | Limited to predefined sites |

Analytical Frameworks and Bioinformatics Challenges

Bioinformatics Tools for Non-Model Organisms

The analysis of DNA methylation data from non-model organisms presents unique bioinformatics challenges, particularly when reference genomes are incomplete or poorly annotated. Specialized tools have been developed to address these limitations.

BSXplorer is specifically designed for exploratory analysis of bisulfite sequencing data in non-model systems [4]. This lightweight tool provides graphical analysis of methylation levels in metagenes or user-defined regions, enables comparative analyses across experimental samples and species, and identifies modules with similar methylation signatures at functional genomic elements [4]. BSXplorer processes methylation data quickly and offers both API and command-line capabilities, creating high-quality publication-ready figures without requiring extensive bioinformatics expertise [4].

Key features of BSXplorer include:

- Profiling methylation levels using line plots and heatmaps

- Generation of summary statistics charts

- Comparative analysis of methylation patterns across samples and species

- Identification of co-methylated genomic regions

- Support for multiple input formats (cytosine report, bedGraph, CGmap)

- Compatibility with poorly annotated genomes [4]

Methylation Analysis Pipelines: For more comprehensive analyses, integrated pipelines like RnBeads 2.0, msPIPE, MethylC-analyzer, and the EpiDiverse Toolkit offer all-in-one solutions for methylation data processing [4]. However, these tools are often optimized for model organisms with well-annotated genomes and may require adaptation for non-model systems.

Reference Genome Considerations

The quality and completeness of reference genomes significantly impact methylation analysis in non-model organisms. When only draft genomes are available, several strategies can improve analytical outcomes:

- Focus on global patterns: Prioritize analyses that don't require precise genomic localization, such as overall methylation levels or methylation in repetitive elements

- Utilize synteny: Leverage genomic conservation with related species to infer positional information

- Iterative improvement: Use methylation data to improve genome assembly, particularly in repetitive regions

- De novo epiallele discovery: Identify consistently methylated regions across samples without reference to annotation

Case Studies: Epigenetic Research in Non-Model Organisms

Marine Macroalga Ulva mutabilis

In a proof-of-concept study, researchers applied acid hydrolysis coupled with Orbitrap mass spectrometry to investigate DNA methylation levels in the green macroalga Ulva mutabilis under standardized culture conditions [2]. This marine organism exhibits exceptionally high global DNA methylation levels, attributed to its densely methylated CpG content [2]. The method successfully quantified cytosine methylation in highly methylated DNA samples where enzymatic approaches might fail, demonstrating the utility of global methylation analysis for non-model organisms with extreme epigenetic features [2]. The study further revealed changes in methylation signatures in Ulva grown in the presence or absence of co-occurring bacterial symbionts that release growth- and morphogenesis-promoting factors, illustrating how epigenetic analysis can elucidate organism-environment interactions in non-model systems [2].

Wild Capuchin Monkey Fecal Epigenetics

Researchers developed a novel protocol for quantifying DNA methylation in non-invasively collected fecal samples from wild white-faced capuchin monkeys (Cebus imitator), demonstrating the feasibility of field epigenetics in wild populations [3]. By combining Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (fecalFACS) with Twist Targeted Methylation Sequencing, they efficiently captured host DNA methylation profiles from fecal matter, covering approximately 905,950 CpG sites despite the fragmented nature of fecal DNA [3]. The resulting epigenetic clock predicted chronological age to within 1.59 years (~3.5% of capuchin lifespan), comparable to highly accurate blood-based clocks in humans [3]. This approach opens new avenues for studying ecological and social determinants of aging in natural populations without requiring invasive sampling.

Non-Invasive Sampling and Field Applications

The expansion of epigenetic research to non-model organisms has driven innovation in non-invasive and minimally invasive sampling techniques. These approaches are particularly valuable for studying endangered species, wild populations, and organisms where traditional tissue sampling is impractical.

Table 3: Non-Invasive Sampling Methods for Epigenetic Studies

| Sample Type | Target Cells | DNA Yield/Quality | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal | Intestinal epithelium | Moderate/fragmented | Age estimation; population studies | Host DNA enrichment needed |

| Urine | Urothelial | Low/fragmented | Developmental studies; health monitoring | Low epithelial cell count |

| Feather pulp | Mesenchymal | Low/moderate | Avian studies; migration | Seasonal availability |

| Hair/bristle | Follicle cells | Low/moderate | Mammalian studies; stress response | Contamination risk |

| Shed skin | Epidermal | Low/fragmented | Reptile and amphibian studies | Degradation issues |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful epigenetic research in non-model organisms requires careful selection of reagents and methodologies adapted to the specific challenges of these systems. The following toolkit highlights essential solutions for overcoming common obstacles.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Non-Model Organism Epigenetics

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application in Non-Models | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acid hydrolysis protocol [2] | Chemical DNA hydrolysis | Global methylation analysis without reference genome | Avoids enzymatic limitations in highly modified DNA |

| EpiTect Fast DNA Bisulfite Kit [7] | Rapid bisulfite conversion | Preservation of DNA quality from suboptimal samples | Faster processing reduces DNA degradation |

| Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip [7] | Genome-wide methylation screening | Cross-species application with conserved CpGs | Limited to species with established probe alignment |

| TET2/APOBEC enzyme mix (EM-seq) [6] | Enzymatic conversion | Gentle alternative to bisulfite for degraded samples | Higher cost but better DNA preservation |

| Nanopore sequencing adapters [6] | Direct methylation detection | Simultaneous genome assembly and methylation calling | Optimal for organisms without reference genomes |

| Bismark bisulfite mapper [4] | Read alignment and methylation calling | Flexible reference genome requirements | Compatible with draft-quality assemblies |

| BSXplorer software [4] | Data visualization and exploration | Analysis without comprehensive annotation | User-friendly for non-bioinformaticians |

| Relcovaptan-d6 | Relcovaptan-d6|Stable Isotope (unlabeled) | Relcovaptan-d6 is a deuterated, selective V1a vasopressin receptor antagonist for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| rac-Pregabalin-d4 | rac-Pregabalin-d4, MF:C₈H₁₃D₄NO₂, MW:163.25 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

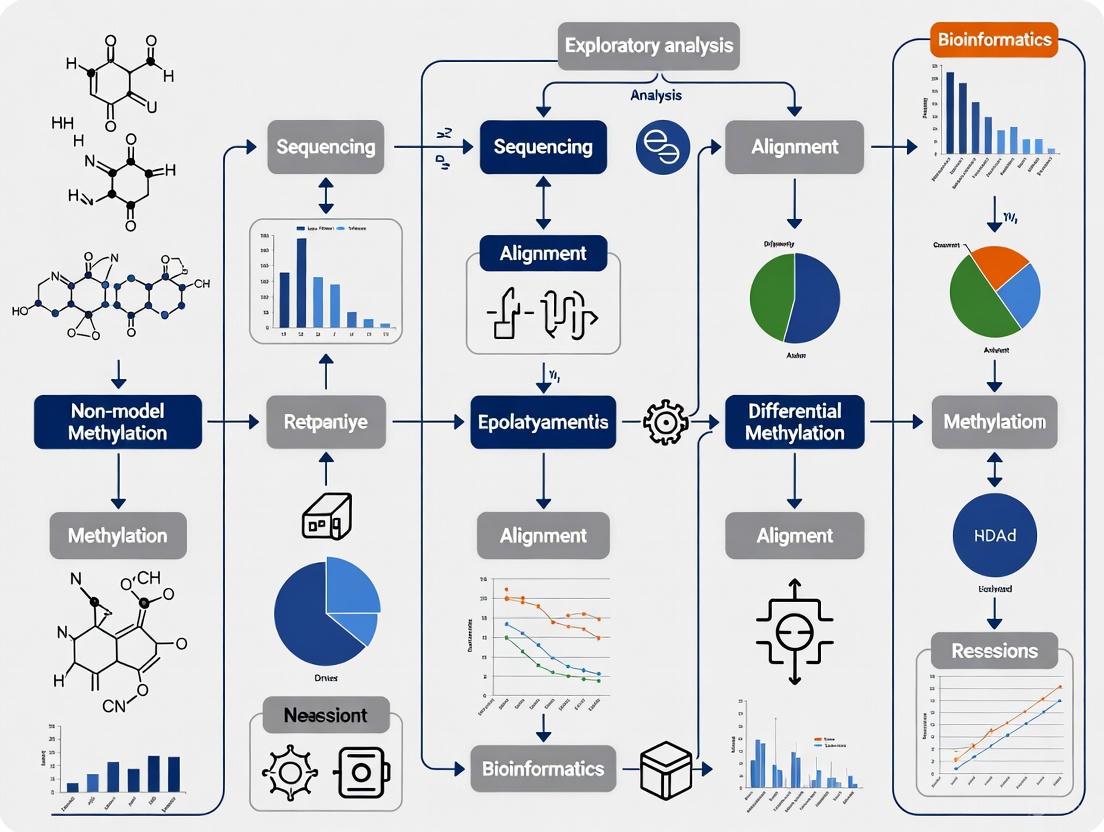

DNA Methylation Analysis Workflow for Non-Model Organisms

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for DNA methylation analysis in non-model organisms, highlighting critical decision points and methodological alternatives at each stage:

Non-Invasive Epigenetic Analysis Pathway

For ecological and conservation applications, non-invasive sampling requires specialized processing pathways as demonstrated in wild capuchin research [3]:

Challenges and Future Directions

Technical and Analytical Limitations

Epigenetic research in non-model organisms faces several significant challenges that require methodological innovation and adapted approaches:

Genomic Resource Limitations: The absence of high-quality reference genomes remains a primary obstacle for precise methylation mapping in non-model organisms. While global methylation analyses circumvent this limitation, they sacrifice genomic context and locus-specific information. Potential solutions include using chromosomal-level assemblies from related species, long-read sequencing technologies for de novo genome assembly, and reference-free analysis methods that identify consistent methylation patterns across samples without positional mapping [4].

Sample Quality and Quantity Issues: Non-model organisms often present challenges in sample collection, particularly for wild populations, endangered species, or organisms with small body sizes. Non-invasive sampling techniques yield fragmented DNA in limited quantities, requiring specialized protocols for DNA extraction and library preparation [3]. Methods like multiple displacement amplification can increase DNA yield but may introduce biases in methylation patterns. EM-seq and optimized bisulfite conversion protocols offer gentler alternatives that preserve DNA integrity better than standard WGBS approaches [6].

Analytical Framework Gaps: Most bioinformatics tools for DNA methylation analysis were developed for model organisms with well-annotated genomes and may perform poorly on non-model systems [4]. There is a critical need for specialized software that accommodates incomplete genomes, supports comparative analyses across diverse taxa, and enables exploratory (rather than hypothesis-driven) research approaches. Tools like BSXplorer represent steps in this direction, but more comprehensive solutions are needed [4].

Standardization and Reproducibility

The lack of standardized protocols for non-model organism epigenetics presents challenges for reproducibility and cross-study comparisons. Variation in DNA extraction methods, bisulfite conversion efficiency, sequencing depth, and bioinformatic pipelines can significantly impact results. Future efforts should focus on establishing best practice guidelines for:

- Sample collection and preservation under field conditions

- DNA quality assessment for degraded samples

- Reference-free methylation analysis

- Cross-species comparative frameworks

- Data reporting standards for improved reproducibility

Integration with Other Omics Approaches

The full potential of non-model organism epigenetics will be realized through integration with complementary omics technologies. Multi-omics approaches combining DNA methylation analysis with transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics can provide mechanistic insights into how epigenetic variation influences phenotype. For example, studies linking methylation patterns to gene expression changes in response to environmental stressors can reveal functional epigenetic mechanisms in ecological contexts. Similarly, connecting epigenetic markers with physiological measurements or behavioral observations can illuminate the functional consequences of epigenetic variation in natural populations.

Non-model organisms represent both a challenge and tremendous opportunity for advancing epigenetic research. The methodological frameworks presented in this review provide multiple entry points for exploring DNA methylation patterns in organisms lacking extensive genomic resources or established laboratory protocols. From global methylation analysis using mass spectrometry to adapted sequencing approaches and specialized bioinformatics tools, researchers now have an expanding toolkit for epigenetic discovery beyond traditional model systems.

The unique biological features, ecological adaptations, and evolutionary diversity of non-model organisms offer unparalleled opportunities to understand how epigenetic mechanisms operate across the tree of life. By embracing these opportunities and addressing the associated methodological challenges, researchers can uncover fundamental principles of epigenetic regulation that may be invisible within the constrained context of traditional model organisms. As technologies continue to advance and methodologies become more accessible, non-model organism epigenetics promises to transform our understanding of gene-environment interactions, adaptive evolution, and the dynamic regulation of genomes across diverse biological contexts.

DNA methylation, the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of a cytosine base (5-methylcytosine, 5mC), constitutes a fundamental epigenetic mechanism that regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [8] [9]. This reversible modification is crucial for a myriad of biological processes, including genomic imprinting, repression of transposable elements, cell differentiation, and the maintenance of cellular identity [8] [10]. In mammals, DNA methylation occurs primarily at cytosine-guanine dinucleotides (CpG sites), with genomic patterns that are dynamically regulated by opposing enzymatic activities [9].

The interpretation and maintenance of these methylation patterns are governed by three principal classes of proteins: "writers" that install the methyl mark, "erasers" that remove it, and "readers" that recognize and translate it into functional biological states [11] [12]. This tripartite system facilitates a responsive and plastic regulatory layer over the genetic code. While these core principles are largely conserved across the animal kingdom, recent comparative epigenomic studies across 580 animal species have revealed both deeply conserved and lineage-specific features, underscoring the dynamic evolution of DNA methylation machinery and its role in shaping species-specific traits [13] [10]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these core components, with a specific focus on implications for research in non-model organisms.

The Core Machinery: Writers, Erasers, and Readers

The establishment, interpretation, and removal of DNA methylation marks are executed by a coordinated set of enzymatic and binding proteins.

Writers: DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs)

DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) are the "writer" enzymes that catalyze the transfer of a methyl group from the universal methyl donor, S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM), to the fifth carbon of a cytosine base, producing 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [9] [11].

- DNMT1 is the primary maintenance methyltransferase in somatic cells. It exhibits a strong preference for hemi-methylated DNA, making it highly effective at copying DNA methylation patterns from the parent strand to the newly synthesized daughter strand during DNA replication, thereby ensuring the faithful inheritance of methylation patterns across cell divisions [9].

- DNMT3A and DNMT3B are de novo methyltransferases responsible for establishing new methylation patterns ab initio, particularly during embryonic development when the methylome is erased and reprogrammed [9]. Their activity is essential for setting up cell-type-specific methylation landscapes.

- DNMT3L is a catalytically inactive regulatory cofactor that stimulates the de novo methylation activity of DNMT3A and DNMT3B, especially in the germline [11].

Table 1: Core DNA Methylation "Writer" Enzymes in Mammals

| Enzyme | Primary Type | Key Function | Catalytic Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Maintenance | Copies methylation patterns after DNA replication | Active |

| DNMT3A | De novo | Establishes new methylation patterns | Active |

| DNMT3B | De novo | Establishes new methylation patterns | Active |

| DNMT3L | Regulatory cofactor | Stimulates DNMT3A/B activity | Inactive |

Erasers: Active DNA Demethylation Pathways

While DNA methylation was long considered a stable modification, the discovery of enzymes capable of active DNA demethylation revealed the dynamic nature of this epigenetic mark. The erasure of 5mC is not performed by a direct "demethylase" but rather through a multi-step process involving the TET (Ten-Eleven Translocation) family of enzymes [11].

TET enzymes (TET1, TET2, TET3) are α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases that iteratively oxidize 5mC to form 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) [11]. These oxidized methylcytosine derivatives are not recognized by the maintenance methyltransferase DNMT1 and can be replaced by an unmodified cytosine via base excision repair (BER) pathways, thereby achieving active DNA demethylation [11]. This pathway is critical for both targeted gene activation and global epigenetic reprogramming events, such as those occurring in early embryogenesis and in primordial germ cells.

Readers: Methyl-Binding Proteins (MBPs)

The biological message encoded by DNA methylation is interpreted by "reader" proteins that specifically recognize and bind to methylated DNA. These readers then recruit additional protein complexes to execute downstream transcriptional outcomes, primarily gene silencing [9].

The classic readers are the Methyl-CpG-Binding Domain (MBD) family of proteins, which includes MeCP2, MBD1, MBD2, and MBD4 [9] [12]. Upon binding to methylated CpG sites, these proteins recruit co-repressor complexes containing factors such as histone deacetylases (HDACs) and histone methyltransferases [9]. HDACs remove activating acetyl marks from histone tails, leading to a more condensed chromatin state. This mechanism exemplifies the profound crosstalk between DNA methylation and histone modifications, where DNA methylation readers directly influence the histone code to reinforce a repressive chromatin environment [9] [14].

Evolutionary Perspectives Across Species

Comparative epigenomic analyses are revolutionizing our understanding of how DNA methylation systems have evolved and how they contribute to phenotypic diversity across the tree of life.

Conservation and Divergence of Methylation Patterns

A landmark study profiling DNA methylation in 580 animal species (535 vertebrates and 45 invertebrates) revealed a broadly conserved link between DNA methylation and the underlying genomic DNA sequence, but with two major evolutionary transitions: one at the emergence of the first vertebrates and another with the rise of reptiles [10]. This suggests significant shifts in how the methylation machinery interacts with the genome at these pivotal points.

Despite these shifts, tissue-specific DNA methylation signatures are deeply conserved. Cross-species comparisons demonstrate that methylation patterns can distinguish tissue types (e.g., heart vs. liver) more strongly than they distinguish individuals within the same species for fish, birds, and mammals [10]. This indicates a fundamental and evolutionarily ancient role for DNA methylation in defining and maintaining cellular identity.

Role in Species-Trait Evolution and Plasticity

DNA methylation is increasingly recognized not just as a static mark but as a dynamic mediator of phenotypic plasticity and evolutionary adaptation [15].

- Short-Term Acclimation: Methylation states can change rapidly in response to environmental stressors such as temperature, salinity, or diet, potentially facilitating acclimation within a single generation [15]. These changes are often transient, highlighting the plasticity of the epigenome.

- Stable Phenotypic Evolution: In some cases, environmentally induced methylation changes can lead to stable, ecologically important phenotypes within a generation, such as sex determination in some fish and reptiles, or caste determination in social insects [15].

- Genomic Evolution: There is a reciprocal relationship between genetic and epigenetic evolution. DNA methylation can be genetically controlled, but it can also promote mutations (e.g., deamination of 5mC to T) and contribute to genomic sequence evolution over longer timescales [15]. Furthermore, promoter methylation changes have been correlated with the evolution of species-specific traits, such as body patterning [13].

Table 2: Evolutionary Roles of DNA Methylation Across Timescales

| Timescale | Role of DNA Methylation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Short-Term (Acclimation) | Rapid, reversible response to environmental cues. | Thermal stress response in fish [15]. |

| Medium-Term (Phenotypic Evolution) | Stable encoding of functional phenotypes within a generation. | Environmental sex determination in reptiles [15]. |

| Long-Term (Genomic Evolution) | Contribution to mutation rates and genomic sequence change; species-specific trait evolution. | Correlation with body patterning evolution in mammals [13]. |

Methodologies for Exploratory Analysis in Non-Model Organisms

For researchers investigating methylation in non-model organisms, where high-quality reference genomes are often unavailable, specific methodologies have been developed.

Reference-Genome-Independent Profiling with RRBS

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) is a powerful, cost-effective method for genome-scale DNA methylation profiling that is particularly suited for cross-species studies [10]. The protocol is as follows:

- Digestion: Genomic DNA is digested with the MspI restriction enzyme (cuts at CCGG sites regardless of methylation). This enzyme has a short, highly common target sequence, ensuring consistent performance across a wide range of species [10].

- Size Selection: The digested fragments are size-selected (typically 40-220 bp) via gel electrophoresis or bead-based clean-up. This step enriches for CpG-rich regions, including many gene promoters and regulatory elements.

- Bisulfite Conversion: The size-selected fragments are treated with sodium bisulfite, which deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. During subsequent PCR amplification, uracils are read as thymines (T).

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Adapters are ligated, and the library is sequenced on a high-throughput platform.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: The sequencing reads are analyzed by comparing C-to-T conversion rates. A C in the original sequence that is read as a T indicates an unmethylated cytosine, while a C that remains a C indicates a methylated cytosine. Because RRBS fragments start and end at defined MspI sites, reads can be grouped and analyzed based on their sequence context alone, without the need for a reference genome assembly [10].

Emerging Single-Cell Multi-Omic Technologies

Cutting-edge technologies now allow for the simultaneous profiling of DNA methylation and histone modifications in the same single cell. The scEpi2-seq (single-cell Epi2-seq) method exemplifies this advance [16].

- Cell Permeabilization and Antibody Binding: Single cells are permeabilized, and a protein A-micrococcal nuclease (pA-MNase) fusion protein is tethered to specific histone modifications (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K9me3) using antibodies.

- MNase Digestion: MNase digestion is activated by adding Ca²âº, cleaving DNA around the bound nucleosomes. This releases fragments bearing the histone mark of interest.

- Adaptor Ligation and TAPS: The released fragments are repaired, A-tailed, and ligated to adaptors containing cell barcodes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs). The material is then subjected to TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS). Unlike bisulfite sequencing, TAPS chemically converts 5mC to uracil, leaving the barcoded adaptors intact, which improves library complexity and quality [16].

- Library Prep and Multi-Omic Readout: The library is prepared via in vitro transcription, reverse transcription, and PCR. Sequencing data provides simultaneous readouts: mapped genomic locations reveal histone modification patterns, while C-to-T conversions identify methylated cytosines, all attributable to a single cell [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

This section details essential reagents and tools for studying DNA methylation, drawing from the experimental protocols discussed.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Methylation Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| MspI Restriction Enzyme | Restriction enzyme for CpG-rich locus enrichment. | DNA fragmentation in RRBS protocol [10]. |

| Sodium Bisulfite | Chemical conversion of unmethylated C to U. | Distinguishing methylated vs. unmethylated cytosines in BS-seq/RRBS [10]. |

| Protein A-MNase (pA-MNase) | Fusion protein for targeted chromatin cleavage. | tethering to antibodies for histone mark profiling in scEpi2-seq [16]. |

| TET Enzymes / Pyridine Borane | Chemical conversion of 5mC to U. | Non-destructive 5mC detection in TAPS-based methods [16]. |

| Anti-Histone Modification Antibodies | Specific recognition of epigenetic marks. | Immunoprecipitation or tethering in scEpi2-seq (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K9me3) [16]. |

| DNMT Inhibitors | Small molecule inhibition of DNA methyltransferases. | Experimental demethylation (e.g., 5-Azacytidine) [12]. |

| MBD Domain Proteins | Affinity enrichment of methylated DNA. | Methylated DNA pulldown for downstream analysis [9]. |

| 2-Azidoethanol-d4 | 2-Azidoethanol-d4, MF:C₂HD₄N₃O, MW:91.11 | Chemical Reagent |

| 10Z-Vitamin K2-d7 | 10Z-Vitamin K2-d7|Deuterated Research Standard | High-purity 10Z-Vitamin K2-d7 for research. An internal standard for LC-MS/MS analysis of Vitamin K2 metabolites. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

The core principles of DNA methylation—governed by the coordinated actions of writers, erasers, and readers—form a dynamic and complex regulatory system that is fundamental to genomic function and integrity. Research in non-model organisms, facilitated by reference-free and multi-omic technologies like RRBS and scEpi2-seq, is critically enriching our understanding of this system. These studies reveal that while the basic machinery is conserved, its deployment and evolutionary impact are fluid, contributing to both stable cellular memory and remarkable phenotypic plasticity. Integrating this epigenetic perspective is therefore indispensable for a unified understanding of evolution, development, and disease.

Evolutionary Conservation and Divergence in Methylation Patterns

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) methylation, the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases, is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism regulating gene expression and genomic stability across eukaryotic life [17]. Its study has evolved from a focus on model organisms to an expansive field that leverages non-model organisms to uncover the evolutionary principles governing epigenetic regulation. Research in diverse species—from marsupials and flatfish to wild primates—reveals a complex interplay between deeply conserved functions and lineage-specific adaptations in methylation systems. This whitepaper synthesizes recent findings from comparative epigenomics to provide a technical guide for researchers exploring methylation patterns in non-model systems, framing them within the context of a broader thesis on evolutionary epigenetics. It details conserved and divergent dynamics, provides standardized protocols for cross-species analysis, and offers a toolkit for exploratory research, aiming to bridge the gap between fundamental epigenetic knowledge and its application in comparative and translational biology.

Core Concepts: Conservation and Divergence in Methylation Systems

DNA methylation predominantly targets cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, though non-CpG methylation is also observed in some contexts [18]. Its functional impact is tightly linked to genomic location: methylation within gene promoter regions typically suppresses gene expression, whereas gene body methylation often associates with active transcription and plays a role in splicing and genomic stability [18] [17]. The distribution of CpG sites and their methylation status across the genome varies significantly among species, forming the basis for comparative evolutionary studies.

Conserved Patterns in Higher Vertebrates: Among higher vertebrates (amniotes), a "global" methylation pattern is highly conserved. This pattern is characterized by near-complete methylation of the genome, with the crucial exception of CpG islands located in promoter regions [17]. These promoter-associated CpG islands are typically unmethylated, allowing for potential gene activation. This system is so fundamental that the regulatory logic of promoter methylation is shared across humans, mice, rats, cows, dogs, and chickens [17]. Furthermore, the development of epigenetic clocks—predictive models of biological age based on DNA methylation patterns—has been successfully demonstrated in wild capuchin monkeys using non-invasive fecal samples. The high accuracy of these clocks (predicting age to within ~3.5% of lifespan) underscores a deeply conserved link between methylation changes and the aging process across mammals, including humans [3].

Divergent Patterns Across Evolutionary Lineages: In contrast to the global pattern of amniotes, many invertebrates, plants, and fungi exhibit a "mosaic" methylation pattern, where heavily methylated domains are interspersed with unmethylated regions [17]. A striking example of evolutionary divergence in methylation dynamics comes from embryogenesis. In eutherian mammals (placental mammals), the paternal genome undergoes active demethylation immediately after fertilization, followed by global passive demethylation, resulting in a hypomethylated early blastocyst [19]. This reprogramming is thought to be essential for resetting epigenetic memory and establishing totipotency. However, recent work in the marsupial Monodelphis domestica (the opossum) reveals a different paradigm. The opossum genome remains hypermethylated during cleavage stages, with demodification occurring later, being transient and modest in the epiblast but sustained in the trophectoderm [19]. This suggests that global erasure is not an absolute requirement for mammalian embryogenesis and highlights divergent uses of DNA demethylation during development.

Table 1: Comparative DNA Methylation Patterns Across Eukaryotes

| Organism Group | Example Species | Methylation Pattern | Key Features and Functional Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher Vertebrates (Amniotes) | Human, Mouse, Cow, Chicken [17] | Global | Genome-wide methylation except for promoter CpG islands; role in promoter-driven gene regulation is conserved. |

| Marsupials | Opossum (Monodelphis domestica) [19] | Divergent Embryonic | Genome remains hypermethylated during early cleavage; no global erasure; sustained hypomethylation in trophectoderm. |

| Flatfish | Turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) [20] | Dynamic Developmental | Stage-specific hypermethylation during metamorphosis climax; role in visual system remodeling. |

| Plants & Invertebrates | Arabidopsis, Fruit Fly (D. melanogaster) [17] | Mosaic | Methylation targeted to gene bodies and transposable elements; crucial for transcriptional silencing of repeats. |

| Non-Methylators | S. cerevisiae (Yeast), C. elegans (Nematode) [17] | Absent | Lack DNA methyltransferase genes and therefore genomic DNA methylation. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Cross-Species Methylation Analysis

Non-Invasive DNA Methylation Profiling for Wild Populations

Studying methylation in wild or non-model species often precludes invasive tissue sampling. The following protocol, adapted from research on wild capuchin monkeys, enables robust methylome analysis from fecal samples [3].

- Step 1: Sample Collection and Cell Sorting. Collect fresh fecal samples and immediately preserve them in a stabilizing buffer (e.g., RNAlater) to prevent DNA degradation. To enrich for host epithelial cells, the protocol employs Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS). A fluorescence-activated cell sorter is used to isolate specific cell populations from the homogenized fecal matter, effectively separating host intestinal cells from the complex microbial background [3].

- Step 2: DNA Extraction and Quality Control. Extract genomic DNA from the sorted cell population using a commercial kit designed for complex or low-quality samples. Assess DNA purity and quantity via spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop) and fluorometry (e.g., Qubit). Verify DNA integrity using gel electrophoresis or a Fragment Analyzer [3] [18].

- Step 3: Targeted Methylation Sequencing. For non-invasive samples with fragmented DNA, whole-genome bisulfite sequencing can be inefficient. Instead, use a capture-based targeted approach like Twist Targeted Methylation Sequencing (TTMS). This method uses a probe set (e.g., designed for the human genome but with demonstrated cross-species applicability) to capture ~4 million CpG sites. Following capture, the library is prepared for sequencing using enzymatic methyl-sequencing (EM-seq), which avoids the DNA degradation associated with traditional bisulfite treatment by using enzymes to distinguish methylated from unmethylated cytosines [3] [18].

- Step 4: Bioinformatic Analysis. Process the sequenced reads: align to a reference genome (or a closely related species' genome), and perform methylation calling to generate a methylation level (beta-value) for each CpG site. Downstream analysis can include building an epigenetic clock with an elastic net regression model, identifying differentially methylated regions (DMRs), and annotating DMRs to genomic features [3] [21].

Base-Resolution Methylation Mapping in Embryonic Tissues

Investigating dynamic processes like embryogenesis requires high-resolution maps from low-input material.

- Step 1: Low-Input Sample Preparation. Manually isolate gametes or preimplantation embryos under a microscope. For marsupial models like the opossum, embryos are collected at precise embryonic days corresponding to key developmental milestones (e.g., embryonic genome activation, lineage specification) [19].

- Step 2: Library Preparation and Sequencing. Utilize low-input bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq). This involves bisulfite converting the minimal genomic DNA, which deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines during sequencing), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged. Libraries are prepared with protocols optimized for low DNA quantities and sequenced on a high-throughput platform [19].

- Step 3: Single-Cell Multi-Omics for Lineage Resolution. To dissect cell-type-specific methylation within an embryo, employ single-cell multi-omics. This technique allows for the simultaneous profiling of DNA methylation and transcriptome from the same single cell. Cells are isolated from embryos at different stages (e.g., pre- and post-lineage divergence) and processed using a commercial single-cell multi-ome kit. This enables the direct correlation of methylation status with gene expression in individual cells of the epiblast and trophectoderm [19].

- Step 4: Data Integration and Comparative Analysis. Generate base-resolution methylation maps for each developmental stage and cell type. Perform differential methylation analysis between stages and lineages. Compare these dynamics to known benchmarks from model eutherians like mice to identify conserved and species-specific reprogramming events [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Selecting the appropriate methodology is critical for successful methylation analysis, especially with challenging samples from non-model organisms. The table below summarizes key solutions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Methylation Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Product/Technology | Function and Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation Profiling | Twist Targeted Methylation Sequencing (TTMS) [3] | Targeted capture of ~4 million CpG sites; ideal for fragmented DNA (e.g., from feces). | Uses human probes with cross-species applicability; combines with EM-seq. |

| Bisulfite-Free Sequencing | Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq) [18] | Bisulfite-free whole-methylome profiling; preserves DNA integrity. | Higher concordance with WGBS; better for low-input/long-range methylation. |

| Third-Generation Sequencing | Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) [18] [22] | Direct detection of modifications during sequencing; no conversion needed. | Enables long-reads, access to complex regions; requires high DNA input. |

| Global Methylation Analysis | Acid Hydrolysis & UHPLC-HRMS [2] | Quantifies global 5mC levels; does not provide locus-specific data. | Rapid, cost-effective; ideal for highly methylated DNA where enzymes fail. |

| Bioinformatic Tools | MethylomeMiner [22] | Processes nanopore methylation calls; assigns sites to genomic features. | Python-based, integrates with pangenome data for population-level analysis. |

| (Z)-Roxithromycin-d7 | (Z)-Roxithromycin-d7, MF:C₄₁H₆₉D₇N₂O₁₄, MW:828.09 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 5-Carboxy Imazapyr | 5-Carboxy Imazapyr | High-purity 5-Carboxy Imazapyr for research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling and Metabolic Pathways Involving DNA Methylation

Methylation Dynamics in Flatfish Metamorphosis

The dramatic remodeling of the visual system during turbot metamorphosis provides a powerful model of how methylation regulates adaptive development. Research using Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) has revealed that the climax stage of metamorphosis is marked by widespread stage-specific hypermethylation, coinciding with the upregulation of the de novo methyltransferase gene dnmt3ab [20]. This wave of methylation is implicated in the remodeling of both the migrating and non-migrating eyes as the fish adapts to a benthic lifestyle.

A key finding is the divergent methylation and expression of transcription factors essential for retinal ganglion cell (RGC) development, such as eomesa and tbr1b, between the migrating and non-migrating eyes [20]. RGCs form the optic nerve, connecting the eye to the brain. The differential epigenetic regulation of these genes likely underlies the asymmetric development of the visual pathway, potentially explaining anatomical differences like the shorter optic nerve in the migrating eye. Furthermore, while genes involved in the phototransduction cascade did not show methylation-linked regulation, their expression profiles shifted as expected: rod-specific genes (for low-light vision) increased, and cone-specific genes decreased post-metamorphosis [20]. This indicates that methylation's primary role in this context is in guiding the structural remodeling of the visual system rather than directly regulating the light-sensing apparatus itself.

The comparative analysis of DNA methylation across the tree of life reveals a nuanced picture of evolutionary dynamics. Deeply conserved mechanisms, such as the regulatory logic of promoter methylation in higher vertebrates and the link between methylation and aging, underscore the fundamental role of this epigenetic mark in animal biology. Simultaneously, profound divergences, exemplified by the alternative reprogramming strategies in marsupial embryos or the context-specific methylation dynamics during flatfish metamorphosis, highlight the plasticity of epigenetic systems. For researchers engaged in exploratory analysis of non-model organisms, this duality is paramount. It necessitates robust, adaptable methodologies—from non-invasive sampling to bisulfite-free sequencing—that can be applied across diverse species. The findings and protocols detailed herein provide a framework for such investigations, emphasizing that the integration of evolutionary context with advanced epigenetic tools is key to unlocking the full functional significance of DNA methylation patterns in shaping biological diversity, health, and disease. The ongoing expansion of epigenomics into wild and non-traditional species promises to further refine our understanding of what is fundamental and what is flexible in the epigenetic regulation of life.

Linking Methylation to Phenotypic Diversity and Environmental Adaptation

DNA methylation, the addition of a methyl group to cytosine or adenine bases, represents a fundamental epigenetic mechanism that influences gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [23]. In the context of ecology and evolutionary biology, DNA methylation provides a potential molecular mechanism for organisms to rapidly respond to environmental challenges, potentially facilitating adaptation [24]. While earlier epigenetic research focused on model organisms and biomedical applications, advances in sequencing technologies and analytical methods now enable detailed investigation of DNA methylation in non-model species [25]. This technical guide explores the current methodologies, key findings, and analytical frameworks for studying the role of DNA methylation in generating phenotypic diversity and promoting environmental adaptation in natural populations.

The study of DNA methylation in non-model organisms presents unique challenges and opportunities. Unlike traditional model systems, non-model species often lack reference genomes, standardized protocols, and established bioinformatic pipelines [25]. However, they offer unparalleled insights into how epigenetic mechanisms operate in natural environments and under realistic selective pressures. This guide synthesizes current approaches for investigating the link between methylation variation, phenotypic diversity, and environmental adaptation, with particular emphasis on technical considerations for research in non-model systems.

Core Concepts: Methylation as an Adaptive Mechanism

Functional Roles of DNA Methylation

DNA methylation serves distinct biological functions across taxa. In eukaryotes, cytosine methylation predominantly occurs in CpG dinucleotides and plays crucial roles in gene regulation, genomic imprinting, and silencing transposable elements [23] [26]. In plants, methylation in CHG and CHH contexts (where H is A, T, or C) provides additional regulatory complexity, particularly for controlling transposable elements [27]. Bacterial systems utilize additional methylation forms, including 6-methyladenine (6mA) and 4-methylcytosine (4mC), primarily involved in restriction-modification systems and gene regulation [28].

The potential for DNA methylation to contribute to adaptive processes stems from several key characteristics: its responsiveness to environmental cues, influence on gene expression, and the heritable nature of certain methylation marks [24]. Environmentally induced methylation changes can create phenotypic heterogeneity that provides substrate for selection, potentially leading to consistent methylation patterns across generations in stable environmental conditions [24]. Additionally, methylation can increase mutation rates at targeted cytosines, potentially capturing beneficial epigenetic variants as genetic mutations over evolutionary time [24].

Evidence for Environmentally Induced Methylation Variation

Recent studies across diverse taxa provide compelling evidence for environmentally associated methylation variation. Research on Arabidopsis lyrata transplanted between lowland and alpine field sites revealed that gene expression is highly plastic, with many more genes differentially expressed between field sites than between populations [27]. While DNA methylation at genic regions was largely insensitive to the environment in this system, transposable elements (TEs) showed significant environmental effects, with higher expression and methylation levels at high-altitude sites [27]. This suggests a broad-scale TE activation under environmental stress, potentially creating novel heritable variation.

In marine macroalga Ulva mutabilis, methylation patterns change in the presence or absence of co-occurring bacterial symbionts that release growth- and morphogenesis-promoting factors [2]. Similarly, wild baboon populations exhibit methylation differences associated with early life experiences and resource base variation [25]. These consistent findings across diverse systems highlight the potential for methylation to mediate organism-environment interactions.

Table 1: Documented Cases of Environmentally Associated DNA Methylation Variation

| Species | Environmental Factor | Methylation Response | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis lyrata [27] | Altitude (lowland vs alpine) | Increased TE methylation and expression | Potential creation of novel heritable variation |

| Ulva mutabilis [2] | Bacterial symbionts | Global changes in cytosine methylation | Altered growth and morphogenesis |

| Baboons (Papio cynocephalus) [25] | Resource base (wild vs human-food) | Differential methylation at specific loci | Unknown fitness consequences |

| Three-spine stickleback [29] | Freshwater vs saltwater adaptation | Population-specific methylation patterns | Potential contribution to local adaptation |

| Heliosperma plants [29] | Alpine vs sub-alpine habitats | Conserved methylation profiles despite ecological divergence | Developmental constraints on methylation |

Quantitative Evidence: Methylation Patterns in Environmental Adaptation

Empirical studies reveal consistent patterns in how methylation variation associates with environmental gradients. A critical finding across multiple systems is that despite the potential for rapid epigenetic change, methylation patterns often show remarkable conservation, suggesting evolutionary constraints [29].

Research on Heliosperma plants adapted to divergent ecological conditions (alpine vs. sub-alpine habitats) revealed surprisingly consistent methylation profiles between species, pointing to significant molecular or developmental constraints acting on DNA methylation variation [29]. This constitutive stability indicates that not all genomic regions are equally prone to environmentally induced methylation changes, with certain loci potentially buffered against epigenetic perturbation.

In humans, a comprehensive methylation atlas of normal cell types demonstrated that methylation patterns are extremely robust across individuals, with less than 0.5% of genomic blocks showing substantial variation across donors [26]. This conservation highlights the fundamental role of DNA methylation in maintaining cell identity and suggests that most interindividual methylation variation occurs at specific regulatory loci rather than affecting the entire genome.

Table 2: Quantitative Patterns of Methylation Variation in Response to Environmental Factors

| Pattern Category | Example System | Key Finding | Technical Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue/Cell Specificity | Human cell types [26] | >99.5% methylation conservation across individuals; tissue-specific patterns at enhancers | Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing |

| Environmental Plasticity | Arabidopsis lyrata [27] | Gene expression highly plastic; TE methylation responsive to altitude | Whole-genome bisulfite & transcriptome sequencing |

| Evolutionary Divergence | Heliosperma species [29] | High methylation conservation despite ecological divergence | bsRADseq |

| Taxonomic Variation | Bacteria vs Eukaryotes [28] | 6mA and 4mC dominant in bacteria; 5mC predominant in eukaryotes | Nanopore sequencing |

| Temporal Stability | Baboons [25] | Early life adversity associated with stable methylation differences later in life | Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing |

Methodological Approaches for Non-Model Systems

Sequencing-Based Methylation Analysis

The advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies has revolutionized methylation analysis in non-model organisms. The following experimental workflows represent the most widely applied approaches:

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) provides base-resolution methylation data across the entire genome but requires substantial sequencing depth and computational resources [27] [26]. The standard protocol involves: (1) DNA extraction and quality control; (2) bisulfite conversion using sodium bisulfite (converts unmethylated cytosines to uracil); (3) library preparation and high-throughput sequencing; (4) alignment to a reference genome; and (5) methylation calling and differential analysis [27]. This approach is particularly valuable for organisms with reference genomes and when comprehensive methylation mapping is required.

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) offers a cost-effective alternative by targeting CpG-rich regions through restriction enzyme digestion (typically Mspl) [25]. This method reduces sequencing costs while capturing methylation information at functionally relevant genomic regions, making it suitable for population-level studies with multiple individuals.

Bisulfite-Converted Restriction Site Associated DNA Sequencing (bsRADseq) combines RADseq with bisulfite sequencing, providing a flexible reduced-representation approach that doesn't require a reference genome [29]. The methodology involves: (1) genomic DNA digestion with selected restriction enzymes; (2) bisulfite conversion of restriction fragments; (3) library preparation and sequencing; and (4) construction of synthetic references for mapping if no reference genome is available. This approach is particularly advantageous for non-model organisms with large genomes or when studying many individuals across populations.

Single-Molecule Real-Time Bisulfite Sequencing (SMRT-BS) leverages third-generation sequencing to achieve long read lengths (up to ~1.5 kb) for targeted CpG methylation analysis [30]. The protocol includes: (1) bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA; (2) amplification of bisulfite-treated DNA using region-specific primers; (3) re-amplification with sample-specific barcodes for multiplexing; (4) SMRT sequencing; and (5) CpG methylation quantitation. This method excels when haplotypic information or long-range methylation patterns are needed.

Nanopore Sequencing enables direct detection of DNA modifications without bisulfite conversion by monitoring changes in electrical current as DNA passes through protein nanopores [28]. This approach can detect all three common bacterial methylation types (5mC, 4mC, and 6mA) with equivalent sequencing depth and is particularly valuable for organisms where bisulfite conversion may be challenging [28].

Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches

As an alternative to sequencing-based methods, mass spectrometry provides quantitative analysis of global DNA methylation levels without sequence context. A recently developed approach uses acid hydrolysis of DNA followed by liquid chromatography and Orbitrap mass spectrometry to directly quantify methyl-modified nucleobases (5-methylcytosine and 6-methyladenine) along with their unmodified counterparts [2].

This method offers several advantages for non-model organisms: (1) it requires only small amounts of DNA (as little as 100 ng); (2) it provides absolute quantification of modification levels; (3) it is independent of the total methylation rate; and (4) it doesn't require reference genomes or complex bioinformatics [2]. The limitations include the lack of locus-specific information and inability to detect sequence context of modifications. This approach is ideal for rapid screening of global methylation differences across multiple samples or treatment conditions.

Bioinformatics and Statistical Considerations

Analysis of methylation data from non-model organisms presents unique bioinformatic challenges. For bisulfite sequencing data, specialized alignment tools like Bismark or BS-Seeker account for C-to-T conversions following bisulfite treatment [31]. For species without reference genomes, de novo assembly of bisulfite-converted reads is particularly challenging, making reduced-representation approaches like bsRADseq advantageous [29].

Statistical analysis must account for the compositional nature of methylation data (percentages between 0-100%) and the potential confounding effects of genetic variation. Methods like MACAU incorporate kinship and population structure into methylation analysis, reducing false positives in structured natural populations [25]. Power analysis is particularly important, as studies with insufficient samples often yield unreliable results—generally, investing in more samples provides better returns than deeper sequencing [25].

Visualizing Methylation-Environment Relationships: Conceptual Framework and Technical Workflows

Conceptual Framework for Methylation in Environmental Adaptation

The relationship between environmental variation, DNA methylation, and phenotypic outcomes can be visualized as a conceptual framework that integrates molecular, organismal, and evolutionary processes:

Technical Workflow for Methylation Analysis in Non-Model Organisms

The experimental pipeline for studying methylation in non-model systems involves multiple steps from sample collection to biological interpretation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful investigation of methylation-environment relationships requires careful selection of laboratory reagents and computational tools. The following table summarizes key solutions for studying DNA methylation in non-model organisms:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Methylation Studies

| Category | Specific Solution | Function/Application | Considerations for Non-Model Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Epigentek Methylamp, Qiagen EpiTect | Convert unmethylated cytosines to uracil for sequencing-based methods | Test conversion efficiency without reference genome using spike-in controls [30] |

| Restriction Enzymes | Mspl (RRBS), various (bsRADseq) | Genome reduction for cost-effective population studies | Enzyme selection affects genomic coverage; test multiple enzymes for optimal representation [29] |

| Library Prep Kits | NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq (EM-seq) | Alternative to bisulfite conversion with less DNA damage | Enables use of degraded samples (e.g., field collections) [31] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina (WGBS, RRBS), PacBio (SMRT-BS), Oxford Nanopore | Detection of methylation patterns | Nanopore detects all modification types without conversion; ideal for bacterial methylation [28] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Orbitrap LC-MS/MS | Global quantification of modified bases | Requires minimal genomic information; ideal for highly methylated genomes [2] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Bismark, MethylKit, MACAU, wgbstools | Read alignment, methylation calling, differential analysis | MACAU accounts for population structure in natural populations [25] |

| Reference Databases | Custom genome assemblies, synthetic references | Mapping and annotation of methylation data | For species without genomes, create synthetic references from RAD loci [29] |

| GNE-0877-d3 | GNE-0877-d3, MF:C₁₄H₁₃D₃F₃N₇, MW:342.34 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 22Z-Paricalcitol | 22Z-Paricalcitol|C27H44O3 | 22Z-Paricalcitol is a stereoisomer for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

The study of DNA methylation in environmental adaptation continues to evolve with rapid methodological advancements. Current evidence suggests that DNA methylation contributes to phenotypic diversity and environmental adaptation through multiple mechanisms: (1) direct regulation of environmentally responsive genes; (2) control of transposable element activity under stress conditions; and (3) creation of heritable variation that can be subject to selection. However, the relative importance of genetic versus epigenetic variation in adaptive processes remains a rich area for future investigation.

Emerging technologies like long-read sequencing and mass spectrometry-based approaches are overcoming previous limitations in studying non-model organisms. These tools, combined with sophisticated statistical methods that account for population structure and genetic relatedness, promise to provide unprecedented insights into the role of epigenetic mechanisms in evolution. Future research should focus on integrating multiple molecular approaches (epigenomic, transcriptomic, and genomic) with field-based phenotypic measurements to establish causal links between methylation variation, phenotypic traits, and fitness outcomes in natural environments.

As the field progresses, standardization of methodologies and data analysis pipelines will be crucial for comparing results across studies and taxa. Particular attention should be paid to distinguishing between causative epigenetic changes and correlated consequences of genetic variation or environmental induction. Through carefully designed studies that leverage the methodologies outlined in this guide, researchers can continue to unravel the complex relationship between DNA methylation, phenotypic diversity, and environmental adaptation across the tree of life.

The study of epigenetic mechanisms in non-model organisms is crucial for understanding the evolutionary landscape of gene regulation and environmental adaptation. DNA methylation, a key epigenetic mark, plays a fundamental role in controlling gene activity without altering the underlying DNA sequence. This case study focuses on the marine macroalga Ulva mutabilis, a pivotal species in coastal ecosystems worldwide and a emerging model organism for epigenetic research in non-model systems [32] [2] [33]. U. mutabilis possesses a remarkably high level of global DNA methylation, characterized by densely methylated CpG content, making it an excellent subject for investigating methylation dynamics [32] [2]. The exploration of these dynamics provides critical insights into how environmentally responsive epigenetic mechanisms operate in organisms beyond traditional models, bridging fundamental knowledge gaps in epigenetics.

Global DNA Methylation Analysis inUlva mutabilis

Quantitative Epigenetics Approach

Recent methodological advances have enabled precise quantification of DNA methylation in highly methylated algal genomes. A novel approach based on acid hydrolysis of DNA coupled with ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography and high-resolution mass spectrometry (UHPLC-HRMS) has been developed specifically for global methylome analysis in Ulva mutabilis [32] [2]. This method offers significant advantages over conventional sequencing techniques for quantitative assessment, providing direct, rapid, cost-efficient, and sensitive quantification of the methyl-modified nucleobase 5-methylcytosine (5mC) along with unmodified nucleobases [32].

Table 1: Key Features of the UHPLC-HRMS Global Methylation Analysis Method

| Feature | Description | Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis Method | HCl-based chemical hydrolysis | Avoids incomplete digestion issues of enzymatic approaches; robust for highly methylated DNA |

| Detection Technique | UHPLC-HRMS | Enables absolute quantification independent of sequence context |

| Data Output | Global methylation percentage | Simple comparison across samples and conditions |

| Sample Requirement | Small DNA amounts | Suitable for limited biological material |

| Bioinformatic Demand | Minimal | No complex sequencing data analysis required |

| Throughput | High | Enables comparison of multitude of samples |

This technical approach addresses a critical methodological gap, as conventional enzymatic hydrolysis methods often demonstrate constrained efficiency with highly methylated DNA samples like those from U. mutabilis [2]. The chemical hydrolysis protocol effectively releases methylated and unmethylated nucleobases without destroying methylation patterns, enabling accurate global methylation assessment.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Ulva Methylation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Standards | 100% unmodified or methylated cytosines (Zymo Research) | Quantification standards and method calibration |

| Internal Standards | 2ˈ-deoxycytidine-13C1, 15N2; 2ˈ-deoxy-5-methylcytidine-13C1, 15N2 | Isotope-labeled internal standards for precise quantification |

| Chemical Standards | Cytosine, 5-methylcytosine, 2ˈ-deoxycytidine (Sigma-Aldrich) | Reference compounds for method development |

| DNA Extraction | Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit with RNase I | High-quality, RNA-free DNA preparation |

| Cultivation Media | Ulva Culture Medium (UCM) | Standardized algal growth conditions |

| Bacterial Symbionts | Roseovarius sp. MS2, Maribacter sp. MS6 | Tripartite community studies; morphogenesis-promoting factors |

Experimental Design and Cultivation Conditions

Standardized Cultivation Protocol

The experimental framework for studying methylation dynamics in Ulva mutabilis requires strictly controlled cultivation conditions. The standard protocol involves maintaining the 'slender' morphotype (strain FSU-UM5-1) in Ulva Culture Medium (UCM) under defined parameters [32] [2]:

- Temperature: 18 ± 2°C

- Light Cycle: 17-hour light/7-hour dark period

- Light Intensity: 40-80 μmol photons mâ»Â²sâ»Â¹

- Culture Types: Axenic conditions or in presence of specific bacterial symbionts (Roseovarius sp. MS2 and Maribacter sp. MS6)

This highly standardized approach yields synchronized clonal populations with minimal variance among biological replicates, essential for robust epigenetic analysis [32]. The ability to culture U. mutabilis under both axenic and symbiotic conditions provides a unique opportunity to investigate cross-kingdom interactions and their epigenetic implications.

DNA Extraction and Hydrolysis Methodology

The sample preparation workflow involves critical steps to ensure accurate methylation quantification:

DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA is extracted from freeze-dried and homogenized algal tissue using the Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit with addition of 50 μg RNase I during cell lysis to ensure RNA-free preparation [32].

Acid Hydrolysis: One μg of extracted DNA undergoes HCl-based hydrolysis, optimizing the release of methylated and unmethylated nucleobases without formylated side-products that complicate analysis [2].

UHPLC-HRMS Analysis: The hydrolyzed samples are directly submitted to chromatographic separation and mass spectrometric detection, allowing simultaneous quantification of 5-methylcytosine and unmodified cytosine [32] [2].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for global DNA methylation analysis in Ulva mutabilis

Comparative Methylation Dynamics in Related Ulva Species

DNA Methylation Patterns in Ulva prolifera Under Stress

Research on the related species Ulva prolifera provides valuable insights into methylation dynamics under environmental stress. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) analysis revealed that the U. prolifera genome exhibits approximately 1.18% cytosine methylation with distinct distribution patterns [34] [35]:

- CpG context: ~72% methylation

- CHG context: ~10% methylation

- CHH context: ~3% methylation

Under elevated temperature-light stress (30°C and 300 μmol photons mâ»Â²sâ»Â¹), U. prolifera showed significant hypomethylation in CpG contexts, while CHG and CHH methylation remained relatively stable [34] [35]. This stress-induced demethylation was particularly associated with transcriptionally active regions, revealing a negative correlation between CG methylation and gene expression patterns.

Functional Implications of Methylation Changes

The methylation changes observed in Ulva species under stress conditions have significant functional implications:

Transcriptional Regulation: CG hypomethylation under abiotic stress provokes transcriptional responses, facilitating expression of stress-responsive genes [34] [35]

Transposon Control: CHG and CHH methylation predominantly found in transposable elements and intergenic regions possibly contribute to genetic stability by restricting transposon activity during stress [34]

Metabolic Reprogramming: Stress conditions trigger upregulation of glycolytic pathway genes, with methylation changes potentially influencing this metabolic shift [34] [35]

Table 3: Stress-Induced Molecular Changes in Ulva Species

| Parameter | Normal Conditions | Stress Conditions | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global CG Methylation | Higher (~72%) | Decreased (hypomethylation) | Enhanced transcriptional responsiveness |

| Glycolysis Genes | Basal expression | Upregulated (GCK, G6PC, GPI, etc.) | Metabolic adaptation to stress |

| Transposable Elements | Controlled methylation | Maintained CHG/CHH methylation | Genome stability preservation |

| Regenerative Capacity | Standard | Rapid spore ejection, new thalli formation | Stress memory and resilience |

| Antioxidant Systems | Basal levels | Increased peroxidase, variable catalase | Oxidative stress management |

Methodological Comparisons in DNA Methylation Analysis

Technical Approaches for Methylation Assessment

The study of DNA methylation in algae employs diverse methodological approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) provides comprehensive, base-resolution methylation mapping but requires substantial resources and complex bioinformatics [5]. Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) offers a cost-effective alternative by focusing on CpG-rich regions but excludes distal regulatory elements [5]. The novel acid hydrolysis/UHPLC-HRMS approach enables rapid global methylation quantification but lacks locus-specific information [32] [2].

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Advanced computational approaches are increasingly being applied to DNA methylation research. Artificial intelligence and machine learning methods show promise for analyzing complex methylation datasets, with models like DeepCpG, MethylNet, and Deep6mA demonstrating capabilities in pattern recognition and prediction [36]. The integration of long-read sequencing technologies (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio SMRT) further expands the toolbox for epigenetic investigation in non-model organisms like Ulva [36] [2].

Diagram 2: Proposed mechanism of methylation-mediated stress response in Ulva