Whole-Transcriptome qPCR Benchmarking: The Gold Standard for Validating RNA-Seq in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to whole-transcriptome quantitative PCR (qPCR) and its critical role as a gold standard for benchmarking RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) technologies and workflows.

Whole-Transcriptome qPCR Benchmarking: The Gold Standard for Validating RNA-Seq in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to whole-transcriptome quantitative PCR (qPCR) and its critical role as a gold standard for benchmarking RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) technologies and workflows. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of using transcriptome-wide qPCR data for validation. The scope covers methodological applications across different research scenarios, from high-throughput drug discovery to clinical diagnostics, and delves into troubleshooting common pitfalls and optimizing protocols using established guidelines like MIQE. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of RNA-seq workflows against qPCR benchmarks, synthesizing key takeaways to enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of transcriptome profiling for robust biomedical and clinical research.

The Foundational Role of qPCR in the RNA-Seq Era: Principles and Necessity

Why qPCR Remains the Gold Standard for Transcriptome Validation

In the era of high-throughput genomics, next-generation sequencing (RNA-Seq) has become the premier tool for the unbiased discovery of transcriptomic changes. However, the transition from discovery to validation and application remains critically dependent on a time-tested technique: quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR). Despite the comprehensive nature of RNA-Seq, its results require confirmation through a highly sensitive, specific, and reproducible method. For this purpose, qPCR maintains its status as the undisputed gold standard for transcriptome validation, a fact consistently demonstrated in rigorous whole-transcriptome benchmarking research. This application note details the experimental protocols and analytical frameworks that solidify qPCR's pivotal role in confirming gene expression data.

The Validation Paradigm: qPCR in the Transcriptomics Workflow

The typical workflow for comprehensive gene expression analysis begins with a broad, discovery-phase screen using RNA-Seq, which can quantify thousands of transcripts simultaneously without a priori knowledge. This is followed by a targeted, validation-phase where the expression levels of key candidate genes are confirmed using qPCR. The reasons for this hierarchical approach are rooted in the complementary strengths of each technology [1] [2].

RNA-Seq excels in discovery but can be variable due to its complex workflow involving library preparation and massive data processing. qPCR, in contrast, provides a direct, focused, and highly accurate measurement that is ideal for confirming the expression of a defined set of genes. Its unparalleled sensitivity allows for the detection of low-abundance transcripts that might be near the detection limit of sequencing assays, and its dynamic range is sufficient to quantify even large fold-changes with precision [3] [4].

Table 1: Technology Comparison for Gene Expression Analysis

| Feature | RNA-Seq | NanoString nCounter | qPCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Discovery, novel transcript identification [1] | Validation & clinical research [1] | Gold standard for validation [5] |

| Throughput | High (entire transcriptome) | Medium (~800 targets) | Low (1-10 targets per reaction) |

| Sensitivity & Dynamic Range | High | Narrower than RNA-Seq [1] | Very High (detection down to one copy) [3] |

| Ease of Use & Workflow | Complex, requires bioinformatics | Simple, 48-hour workflow [1] | Fast, simple (1-3 days) [1] |

| Cost & Resource Demand | High (sequencing & computational cost) | Moderate | Low cost for targeted studies [1] |

Core Experimental Protocol: A Framework for Robust Validation

The following section provides a detailed methodology for using RT-qPCR to validate transcriptome data, from assay design to data analysis.

Critical Pre-Validation Step: Selection of Reference Genes from RNA-Seq Data

A common pitfall in validation is the use of traditional housekeeping genes (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH) as reference genes without verifying their stability. These genes can exhibit significant expression variability under different biological conditions, leading to misinterpretation of results [5]. A more robust strategy is to use the RNA-seq data itself to identify the most stable genes for the specific biological system under study.

Software Solution: The Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) software is a purpose-built tool that identifies optimal reference and variable candidate genes directly from RNA-seq data (Transcripts Per Million, or TPM, values) [5]. Its algorithm applies a series of filters to select genes that are both stable and highly expressed, ensuring they are suitable for reliable detection by qPCR.

GSV Filtering Criteria for Reference Genes:

- Expression greater than zero in all RNA-seq libraries.

- Low variability: standard deviation of log2(TPM) < 1.

- No outlier expression: |log2(TPMi) - mean(log2(TPM))| < 2.

- High expression: mean(log2(TPM)) > 5.

- Low coefficient of variation: (σ / μ) < 0.2 [5].

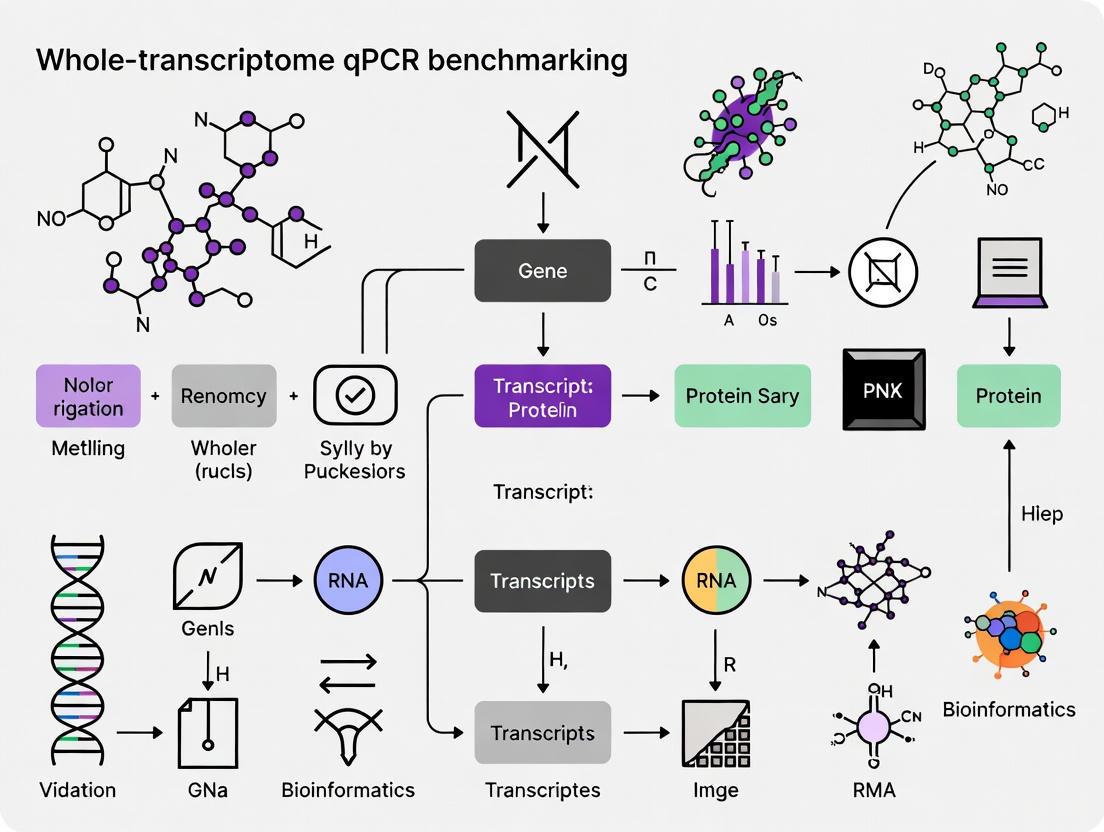

Figure 1: GSV software workflow for selecting stable reference genes from RNA-seq data.

Detailed Step-by-Step RT-qPCR Protocol

Principle: Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) involves the conversion of RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) followed by its amplification and quantification in real-time using fluorescent reporters [3].

I. RNA Extraction and Quality Control

- Input Material: Use high-quality, DNA-free total RNA. RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 7 is recommended for reliable results [6].

- Protocol: Extract RNA using a phenol-guanidine isothiocyanate-based reagent (e.g., TRIzol) or silica-membrane columns, following manufacturer protocols [6].

II. Reverse Transcription (cDNA Synthesis)

- Reaction Setup: Use 1 μg of total RNA in a 20 μL reaction.

- Priming Strategy:

- Random Hexamers: Ideal for validating a diverse set of genes, including those without poly-A tails.

- Oligo-d(T) Primers: Suitable for enriching mRNA from total RNA.

- Enzyme: Use a reverse transcriptase with high efficiency and stability (e.g., SuperScript III/IV) [6].

- Thermocycler Conditions:

- 10 minutes at 25°C (primer annealing)

- 50 minutes at 50°C (reverse transcription)

- 5 minutes at 85°C (enzyme inactivation)

III. Quantitative PCR

- Reaction Composition:

- 1X SYBR Green Master Mix (includes DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and dye)

- Forward and Reverse Primers (200 nM each, final concentration)

- cDNA template (2-100 ng equivalent of input RNA)

- Nuclease-free water to 20 μL

- Primer Design Guidelines:

- Length: 15-30 base pairs.

- Amplicon Size: 70-200 bp (optimal for efficiency).

- Melting Temperature (Tm): 60-65°C for both primers.

- GC Content: 40-60% [4].

- qPCR Run Parameters:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes (also activates hot-start polymerase).

- 40-45 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute.

- Melting Curve Analysis: 60°C to 95°C, with continuous fluorescence measurement (if using SYBR Green chemistry).

Essential qPCR Controls

- No Template Control (NTC): Contains all reaction components except cDNA. Checks for contamination.

- No Reverse Transcription Control (NRT): Uses RNA that has not been reverse transcribed. Checks for genomic DNA contamination.

- Positive Control: A sample with known expression of the target gene. Verifies assay functionality.

- Inter-Run Calibrator: A constant sample included in all runs to normalize for inter-assay variation.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptome Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagent | Preserves RNA integrity at sample collection | TRIzol, RNAlater |

| Reverse Transcriptase Kit | Synthesizes cDNA from RNA template | SuperScript III/IV (Thermo Fisher) |

| SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix | Provides all components for amplification & fluorescence detection | TaqPath ProAmp (Thermo Fisher) |

| Assay-on-Demand Primers/Probes | Pre-validated, highly specific assays for target genes | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent free of RNases and DNases | Essential for reaction consistency |

| Optical Plates & Seals | Ensure optimal thermal conductivity and prevent evaporation | Compatible with real-time PCR instrument |

Data Analysis and Statistical Considerations

Quantification Methods

For transcriptome validation, the Comparative Cq (ΔΔCq) Method is most commonly used for relative quantification [3] [4]. This method calculates the fold-change in expression of a target gene in a treated sample relative to a control sample, normalized to one or more stable reference genes.

Calculation Steps:

- Calculate ΔCq for each sample: ΔCq = Cq (target gene) - Cq (reference gene)

- Calculate ΔΔCq: ΔΔCq = ΔCq (test sample) - ΔCq (control sample)

- Calculate Fold-Change: Fold-Change = 2^(-ΔΔCq)

Accounting for Efficiency: The Pfaffl method provides a more accurate calculation when the amplification efficiencies of the target and reference genes are not equal and perfect (100%) [7]. The formula is: [ \text{Fold Change} = \frac{(E{\text{target}})^{-\Delta Cq{\text{target}}}}{(E{\text{ref}})^{-\Delta Cq{\text{ref}}}} ] Where E is the amplification efficiency (1 for 100% efficiency, 2 for perfect doubling).

Statistical Analysis and Software

Robust statistical analysis is required to assign confidence to the fold-change results. The rtpcr package in R is a comprehensive tool designed for this purpose [7]. It can:

- Accommodate up to two reference genes and incorporate amplification efficiency values (Pfaffl method).

- Perform statistical tests (t-test, ANOVA, ANCOVA) on efficiency-weighted ΔCq values.

- Provide standard errors, confidence intervals, and mean comparisons for fold-change or relative expression values.

- Generate publication-quality graphs.

Figure 2: Statistical analysis workflow for qPCR validation data using the rtpcr package.

Case Study: Validating a Pancreatic Cancer Signature

A 2025 study exemplifies the gold-standard validation workflow. Researchers used machine learning on 14 public pancreatic cancer transcriptomic datasets to identify a novel 5-gene diagnostic signature (LAMC2, TSPAN1, MYO1E, MYOF, SULF1) [6].

Validation Protocol:

- Sample Cohort: 55 peripheral blood samples (30 pancreatic cancer patients, 25 healthy controls).

- RNA Source: Total RNA extracted from peripheral blood.

- qPCR Method: SYBR Green-based one-step RT-qPCR on an ABI 7900HT system. Each reaction was performed in triplicate.

- Normalization: GAPDH was used as the endogenous control.

- Quantification: The 2^(-ΔΔCq) method was used to calculate relative expression.

Result: The qPCR validation successfully confirmed the differential expression of all five genes in patient blood samples, achieving an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.83 for distinguishing cancer from normal conditions. This independent validation using a different technology (qPCR) and a different sample type (blood vs. tissue) confirmed the robustness and clinical potential of the computationally derived signature [6].

Quantitative PCR remains an indispensable component of the modern transcriptomics pipeline. Its unique combination of sensitivity, precision, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness for targeted gene expression analysis is unmatched by other current technologies. By following the detailed protocols outlined herein—from bioinformatic selection of stable reference genes using RNA-seq data to rigorous experimental execution and statistical analysis with tools like the rtpcr package—researchers can confidently employ qPCR to provide the final, definitive validation of their transcriptomic discoveries, thereby ensuring the robustness and reliability of their scientific conclusions.

Reference materials are indispensable tools for assessing the reliability and reproducibility of transcriptomic technologies, including RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and whole-transcriptome quantitative PCR (qPCR). They provide a "ground truth" that enables laboratories to benchmark their analytical performance, from sample processing to data analysis. The MicroArray/Sequencing Quality Control (MAQC) consortium and the more recent Quartet Project have developed the two most prominent suites of RNA reference materials. The MAQC consortium established its reference samples to assess the performance of microarray and next-generation sequencing technologies [8]. The Quartet Project, initiated as part of MAQC phase IV, developed multi-omics reference materials from a Chinese family quartet to enable more sensitive assessment of transcriptomic technologies, particularly for detecting subtle biological differences relevant to clinical diagnostics [9] [10].

The choice between these reference materials is not trivial; it fundamentally shapes the conclusions a researcher can draw about their platform's capability. This note details the properties, applications, and experimental protocols for using the MAQC and Quartet reference materials, with a specific focus on their role in whole-transcriptome qPCR benchmarking research.

Material Properties and Comparative Characteristics

The MAQC Reference Materials

The MAQC project established two primary RNA reference materials:

- MAQC A (Universal Human Reference RNA): A pool of total RNA from ten human cell lines.

- MAQC B (Human Brain Reference RNA): Sourced from brain tissues of 23 donors [8] [11].

These samples were designed to have substantial biological differences, enabling initial validation of platform performance for large-fold-change differential expression. They have been extensively used by the community to benchmark RNA-seq workflows against qPCR data [11].

The Quartet Reference Materials

The Quartet Project developed a suite of four reference materials derived from immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines from a Chinese family quartet:

- D5 and D6: Monozygotic twin daughters.

- F7: Father.

- M8: Mother [9].

A key advantage of this design is the subtle biological differences between the samples, which are more representative of the challenges encountered in clinical scenarios, such as distinguishing between disease subtypes or stages [8] [9].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of MAQC and Quartet Reference Materials

| Characteristic | MAQC A & B | Quartet (D5, D6, F7, M8) |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Origin | 10 cancer cell lines (A) vs. 23 donor brains (B) | Lymphoblastoid cell lines from a family quartet |

| Key Feature | Large biological differences | Subtle, clinically relevant differences |

| Sample Differences | ~16,500 mean DEGs [9] | ~2,100 mean DEGs [9] |

| "Ground Truth" | TaqMan datasets for hundreds of genes [8] | Ratio-based reference datasets; family relationships provide built-in truth [9] [10] |

| Primary Application | Initial platform validation; workflow benchmarking | Proficiency testing for subtle differential expression; cross-batch integration [8] |

Application in Whole-Transcriptome qPCR Benchmarking

Benchmarking RNA-seq against qPCR

Whole-transcriptome qPCR is often considered a gold standard for validating gene expression measurements from high-throughput platforms like RNA-seq. A foundational study used the MAQC A and B samples to benchmark five different RNA-seq data processing workflows (Tophat-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks, STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, and Salmon) against a whole-transcriptome qPCR dataset of 18,080 protein-coding genes [11].

Key findings from this benchmark include:

- High Concordance: Overall, high gene expression fold-change correlations (R² > 0.93) were observed between all RNA-seq workflows and qPCR data when comparing MAQC A and B [11].

- Systematic Discrepancies: A small but significant set of genes showed inconsistent measurements between RNA-seq and qPCR across all workflows. These genes were typically shorter, had fewer exons, and were lower expressed, suggesting technology-specific biases that researchers must account for [11].

- Workflow Performance: Alignment-based methods like Tophat-HTSeq showed a slightly lower fraction of non-concordant genes (15.1%) compared to pseudoalignment methods like Salmon (19.4%) [11].

Assessing Subtle Differential Expression

While the MAQC samples are excellent for assessing large fold-changes, the Quartet samples provide a more stringent and clinically relevant test. The Quartet study demonstrated that quality control based solely on MAQC samples does not guarantee accurate identification of subtle differential expression [8]. In a multi-center study involving 45 laboratories, inter-laboratory variation was significantly greater when analyzing the subtle differences among Quartet samples compared to the large differences between MAQC A and B [8]. This underscores the necessity of using reference materials like the Quartet for validating assays intended for clinical diagnostics, where distinguishing subtle expression patterns is critical.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Protocol 1: Benchmarking with MAQC Samples against qPCR

This protocol is adapted from the study that validated RNA-seq workflows using whole-transcriptome qPCR data [11].

Procedure:

- Sample Acquisition and Preparation: Obtain MAQC A and B reference materials. Perform RNA extraction if necessary, though these are often available as purified RNA.

- cDNA Synthesis and qPCR: Convert RNA to cDNA. Perform whole-transcriptome qPCR using a validated assay panel. The benchmark study used assays detecting specific transcript subsets, with Cq-values used for downstream analysis.

- RNA-seq Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare RNA-seq libraries from the same MAQC A and B samples. Sequence on your chosen platform.

- Data Processing with Multiple Workflows: Process the raw RNA-seq reads through several representative workflows. The benchmark included:

- Alignment-based workflows: Tophat or STAR for read alignment, followed by HTSeq for gene-level counting or Cufflinks for transcript-level quantification.

- Pseudoalignment workflows: Kallisto or Salmon for transcript-level quantification.

- Expression Quantification and Normalization:

- For gene-level workflows (HTSeq), convert read counts to TPM (Transcripts Per Million).

- For transcript-level workflows (Cufflinks, Kallisto, Salmon), aggregate transcript TPMs to the gene level based on the transcripts detected by the qPCR assays.

- Filter genes based on a minimal expression threshold (e.g., 0.1 TPM in all samples) to reduce noise.

- Benchmarking Analysis:

- Fold-Change Correlation: Calculate log2 fold-changes for all genes between MAQC A and B. Correlate these fold-changes with the ΔCq values from qPCR.

- Concordance Analysis: Categorize genes based on their differential expression status (e.g., DE vs. non-DE) in both RNA-seq and qPCR to identify a set of non-concordant genes for further inspection.

Protocol 2: Proficiency Testing with Quartet Samples

This protocol leverages the Quartet reference materials to assess a platform's ability to detect subtle differential expression and integrate data across batches [8] [9].

Procedure:

- Study Design: Include the four Quartet RNA reference materials (D5, D6, F7, M8) with multiple technical replicates in each batch. For comprehensive benchmarking, spike-in controls (e.g., ERCC RNA) can be added.

- Sample Processing and Data Generation: Process the samples using your standard RNA-seq or qPCR protocol. For multi-batch studies, distribute the same set of Quartet samples across all batches.

- Quality Control with Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR):

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the gene expression data of the Quartet samples.

- Calculate the PCA-based SNR. This metric quantifies the ability to distinguish the intrinsic biological differences ("signal") among the four Quartet samples from the technical variations ("noise") among replicates [9].

- A higher SNR indicates better proficiency. An SNR near or below zero suggests an inability to distinguish the sample groups due to high technical noise [9].

- Accuracy Assessment:

- Use the ratio-based reference datasets provided by the Quartet Project as "ground truth" [9].

- Compare your measured expression ratios (e.g., D5/D6, F7/D6) against these reference values to assess quantitative accuracy.

- Data Integration Assessment (for multi-batch studies): Use the Quartet samples as a common anchor to evaluate and correct for batch effects. The ratio-based profiling approach, which scales the absolute values of a study sample relative to a common reference sample (e.g., D6), has been shown to improve cross-batch data integration [10].

The following diagram illustrates the core logical relationship and workflow for using the Quartet reference materials:

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Benchmarking Studies

| Item | Function in Benchmarking | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| MAQC A & B RNA | Validating workflows for large differential expression; benchmarking against legacy data. | FDA-led MAQC Consortium [8] [11] |

| Quartet RNA Reference Materials | Proficiency testing for subtle differential expression; assessing cross-batch integration in multi-center studies. | Quartet Project; approved as Chinese National Reference Materials (GBW09904-GBW09907) [9] |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | External RNA controls added to samples to monitor technical performance and dynamic range. | External RNA Control Consortium (ERCC) [8] |

| Whole-Transcriptome qPCR Assays | Providing a orthogonal "gold standard" dataset for validating gene expression measurements from RNA-seq. | Studies utilize validated panels covering thousands of genes [11] |

| Ratio-Based Reference Datasets | Provide "ground truth" for expression ratios between specific samples (e.g., D5/D6), enabling accuracy assessment. | Quartet Project Data Portal [9] |

| Quartet Multi-Omics Data | Allow for integrated benchmarking across genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. | Quartet Data Portal (https://chinese-quartet.org/) [12] |

The integration of quantitative PCR (qPCR) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data represents a critical challenge and opportunity in modern genomic research. While RNA-seq has become the gold standard for whole-transcriptome gene expression quantification, qPCR remains the method of choice for validating gene expression data due to its precision, sensitivity, and established reliability in regulated bioanalysis [11] [13]. This practical framework addresses the pressing need for standardized approaches to align these complementary technologies, enabling researchers to leverage the comprehensive scope of RNA-seq with the analytical precision of qPCR validation.

The necessity for robust alignment protocols is particularly evident in drug development contexts, where regulatory submissions require rigorous methodological validation [14] [13]. Furthermore, with the expanding applications of these technologies in cell and gene therapy development—including biodistribution, transgene expression, viral shedding, and cellular kinetics studies—harmonization of qPCR and RNA-seq data has become increasingly important for advancing therapeutic innovations [14].

Fundamental Technological Principles and Challenges

Understanding Methodological Differences

qPCR and RNA-seq approach gene expression quantification through fundamentally different experimental and computational paradigms. qPCR relies on amplification efficiency and threshold cycles (Ct) to quantify specific targets through fluorescence measurements, while RNA-seq uses high-throughput sequencing to generate millions of short reads that are computationally mapped to reference genomes [15] [16].

The core challenge in aligning these datasets stems from their different quantification fundamentals: qPCR measures amplification kinetics for predefined targets, whereas RNA-seq infers expression through read counting and statistical modeling [17] [11]. This fundamental difference means that expression measurements from these platforms represent distinct molecular phenotypes, with qPCR typically targeting specific transcript regions and RNA-seq providing gene- or transcript-level coverage [17].

Several technical factors contribute to discrepancies between qPCR and RNA-seq expression measurements. Library preparation protocols for RNA-seq introduce multiple potential biases, including amplification biases, fragmentation effects, and sequencing depth variations [16]. For highly polymorphic gene families like HLA, standard RNA-seq alignment methods may fail to accurately represent true expression due to reference genome mismatches and cross-alignments between paralogs [17].

qPCR measurements face their own challenges, including primer efficiency variations, amplification stochasticity at low template concentrations, and the critical selection of appropriate normalization genes [18] [11]. These methodological differences manifest in systematic discrepancies, with studies showing that a small but consistent set of genes shows divergent expression measurements between platforms [11].

Experimental Design for Cross-Platform Alignment

Sample Preparation and Processing

Consistent sample handling is paramount for successful dataset alignment. RNA should be extracted using standardized protocols across all planned assays, with attention to RNA integrity and purity [19]. For cell line experiments, the number of biological replicates significantly impacts reliability, with at least three replicates per condition considered the minimum standard for robust statistical inference [20].

When designing experiments that will incorporate both technologies, researchers should implement parallel processing pathways where samples are divided for RNA-seq and qPCR analysis at the earliest possible stage. This approach minimizes technical variations introduced through separate handling procedures. For single-cell applications, collection directly into lysis buffers is recommended rather than RNA extraction, due to limited starting material [18].

Platform-Specific Optimization

For RNA-seq library preparation, sequencing depth must be carefully considered. While 20-30 million reads per sample is often sufficient for standard differential expression analysis, deeper sequencing may be required for detecting low-abundance transcripts [20]. The choice between short-read (Illumina) and long-read (Nanopore, PacBio) technologies should align with research goals, considering the trade-offs between throughput, error rates, and transcript reconstruction capability [16].

For qPCR assays, primer design should target exons separated by substantial introns to prevent genomic DNA amplification [18]. Reverse transcriptase selection significantly impacts results, with studies recommending high-efficiency enzymes like Maxima H- or SuperScript IV for single-cell applications [18]. Validation of amplification efficiency for each primer pair is essential for accurate quantification.

Table 1: Key Considerations for Experimental Design

| Design Factor | qPCR Optimization | RNA-seq Optimization | Alignment Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Quality | RIN > 8 for consistent reverse transcription | RIN > 8 for library preparation | Identical RNA quality metrics for both platforms |

| Replication | Minimum 3 technical replicates | Minimum 3 biological replicates | Balanced replication across platforms |

| Normalization | Multiple reference genes [11] | Advanced methods (e.g., TMM, median-of-ratios) [20] | Validation of normalization approaches |

| Dynamic Range | 5-6 logs with efficiency validation | 5+ logs with sufficient sequencing depth | Comparable range verification |

| Target Specificity | Primer validation with melt curves | Mapping quality control | Consistent transcript annotation |

Computational Framework for Data Alignment

RNA-seq Processing and Normalization

The computational processing of RNA-seq data significantly impacts correlation with qPCR measurements. A systematic evaluation of 192 alternative RNA-seq processing pipelines revealed substantial variation in performance, emphasizing the importance of pipeline selection [19]. Processing workflows generally fall into two categories: alignment-based methods (e.g., STAR-HTSeq, Tophat-HTSeq) and pseudoalignment methods (e.g., Kallisto, Salmon) [11].

For gene expression quantification, normalization approach selection is critical. Simple normalization methods like Counts Per Million (CPM) account only for sequencing depth, while more advanced methods like Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) and median-of-ratios (DESeq2) correct for library composition biases [20]. These advanced methods generally show better concordance with qPCR measurements for differential expression analysis [20] [11].

Table 2: RNA-seq Normalization Methods and Applications

| Method | Sequencing Depth Correction | Library Composition Correction | Suitable for DE Analysis | qPCR Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Yes | No | No | Low |

| FPKM/RPKM | Yes | No | No | Moderate |

| TPM | Yes | Partial | No | Moderate |

| TMM | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Median-of-Ratios | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

Cross-Platform Data Integration

Successful alignment of qPCR and RNA-seq datasets requires careful transcript annotation matching. For RNA-seq workflows that perform transcript-level quantification (Cufflinks, Kallisto, Salmon), gene-level expression values should be calculated by aggregating transcript-level values corresponding to the specific transcripts detected by the qPCR assays [11].

Expression correlation analysis should assess both absolute expression levels and relative fold changes between conditions. Studies demonstrate that while absolute expression correlations between RNA-seq and qPCR are generally high (Pearson R² = 0.80-0.85), fold change correlations show even better concordance (R² = 0.93-0.94) [11]. This supports the practice of prioritizing fold change comparisons when integrating data across platforms.

A benchmarked analysis framework should include outlier detection to identify genes with inconsistent measurements between platforms. These outliers frequently share characteristics such as shorter gene length, fewer exons, and lower expression levels [11]. For highly polymorphic genes like HLA loci, specialized computational pipelines that account for known diversity significantly improve expression estimation accuracy [17].

Experimental Protocol for Method Alignment

Sample Processing Workflow

The following integrated protocol ensures optimal alignment between qPCR and RNA-seq datasets:

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

- Extract total RNA using standardized kits (e.g., RNeasy Plus Mini)

- Assess RNA Integrity Number (RIN) using Bioanalyzer (RIN > 8 required)

- Aliquot identical RNA samples for parallel qPCR and RNA-seq analysis

RNA-seq Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Use TruSeq Stranded mRNA library preparation kit or equivalent

- Sequence on Illumina platform (minimum 30 million paired-end 101bp reads per sample)

- Include biological replicates (minimum n=3 per condition)

qPCR Assay Implementation

- Reverse transcribe 1μg total RNA using SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System

- Perform TaqMan qPCR assays in duplicate

- Include no-template controls and inter-run calibrators

Data Processing

- Process RNA-seq data through selected alignment pipeline (e.g., STAR-HTSeq)

- Normalize using TMM or median-of-ratios methods

- Analyze qPCR data using global median normalization or most stable reference genes

Validation and Quality Assessment

Implement rigorous quality assessment at each processing stage:

- RNA-seq QC: Review FastQC reports, alignment rates, and genomic distribution of reads

- qPCR QC: Assess amplification efficiency, melt curves for SYBR Green assays, and replicate consistency

- Cross-platform QC: Calculate correlation coefficients and identify systematic outliers

For genes showing discrepant measurements between platforms, conduct additional investigation through orthogonal validation methods or inspection of sequence characteristics that might explain technical artifacts.

Visualization of Integrated Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for aligning qPCR and RNA-seq datasets, highlighting parallel processing paths and integration points:

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Quality Assessment | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, RIN scoring | RNA integrity verification | Critical for both platforms; requires RIN >8 |

| Reverse Transcription | Maxima H- Reverse Transcriptase, SuperScript IV | cDNA synthesis from RNA | High efficiency crucial for low-input samples |

| qPCR Chemistry | TaqMan probes, SYBR Green | Target amplification & detection | TaqMan offers better specificity for complex genes |

| RNA-seq Library Prep | TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit | Library construction | Maintains strand information for accurate mapping |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina HiSeq/MiSeq | High-throughput sequencing | Balanced read depth and cost considerations |

| Alignment Tools | STAR, HISAT2, TopHat2 | Read mapping to reference | STAR recommended for speed and sensitivity |

| Quantification Tools | HTSeq-count, featureCounts, Kallisto | Gene expression quantification | Kallisto offers fast pseudoalignment |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, edgeR | Statistical analysis of DE genes | Incorporate normalization specific to each |

| Specialized HLA Tools | HLA-specific alignment pipelines | Expression of polymorphic genes | Required for accurate HLA expression quantification |

The alignment of qPCR and RNA-seq datasets requires a systematic approach addressing both experimental and computational dimensions. By implementing standardized protocols, selecting appropriate normalization strategies, and applying rigorous quality control measures, researchers can effectively integrate these complementary technologies. The framework presented here enables robust cross-platform validation essential for confident biological interpretation and regulatory applications in drug development contexts.

As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve and qPCR maintains its position as a validation gold standard, the continued refinement of alignment methodologies will remain crucial for maximizing the value of transcriptomic data across basic research and clinical applications.

In the context of whole-transcriptome qPCR benchmarking research, ensuring data reliability requires rigorous assessment of key performance metrics. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is not a "quick confirmation" tool but a precise measurement system demanding analytical scrutiny equal to microarrays or next-generation sequencing [21]. Challenges in data interpretation persist, particularly at low target concentrations where technical variability, stochastic amplification, and efficiency fluctuations confound quantification [21]. The widespread assumption that qPCR outputs are intrinsically reliable has exacerbated reproducibility issues and contributed to misleading conclusions in both diagnostic settings and gene expression studies [21].

This protocol outlines standardized methodologies for evaluating three fundamental qPCR performance metrics—correlation, fold-change, and dynamic range—within a whole-transcriptome benchmarking framework. Accurate measurement of these metrics is particularly crucial for detecting subtle differential expression, which manifests as minor changes in gene expression profiles between sample types with similar transcriptomes [8]. Such precision is essential for distinguishing biologically meaningful signals from technical noise, especially when validating high-throughput sequencing data where small fold changes can be overinterpreted without proper statistical support [21].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for qPCR Assay Validation

| Metric | Calculation Method | Optimal Performance Range | Impact of Low Target Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | Serial dilutions of quantified standards across 3+ orders of magnitude | R² ≥ 0.99 for standard curve [21] | Increased variability exceeding biologically meaningful differences [21] |

| Amplification Efficiency | Standard curve slope (E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1) | 90-105% (approximately 3.6-3.1 Cq per 10-fold dilution) [22] | Efficiency fluctuations significantly impact fold change calculations [21] |

| Technical Variability (Precision) | Standard Deviation (SD) or Coefficient of Variation (CV) of Cq values | Tight Cq clustering (SD 0.07-0.21 for optimized assays) [21] | Markedly increased variability, often requiring ≥5 replicates at Cq >30 [21] |

| Fold Change Accuracy | Efficiency-adjusted ΔΔCq model [22] | CI should exclude 1.0 for biological significance | 95% confidence intervals often exceed fold change magnitude [21] |

| Correlation with Reference Methods | Pearson correlation with ddPCR or TaqMan data [8] | r ≥ 0.875 for protein-coding genes [8] | Lower correlations (r ≈ 0.825) for broader gene sets [8] |

Table 2: Inter-Instrument Variability in ΔCq Measurements

| Comparison Type | Observed ΔCq Variability | Equivalent Fold Change | Biological Significance Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-Instrument | 1.4-1.7 ΔCq [21] | 2.6-3.2 fold | Exceeds common 2-fold threshold [21] |

| Pooled Instruments | 1.5 ΔCq [21] | 2.9 fold | Exceeds common 2-fold threshold [21] |

| Inter-Instrument | Platform-specific shifts observed | Varies by platform | Can produce biologically meaningful ΔCq shifts [21] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing Dynamic Range and Amplification Efficiency

Purpose: To characterize the linear dynamic range and amplification efficiency of qPCR assays for whole-transcriptome analysis.

Materials:

- ddPCR-quantified DNA standards or cDNA synthetic constructs

- Optimal primer pairs and probes

- qPCR master mix compatible with detection system

- Multi-platform qPCR instruments (e.g., Bio-Rad CFX Opus, BMS Mic)

Procedure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of quantified standards spanning at least 3 orders of magnitude (e.g., 10^1 to 10^6 copies/μL) in triplicate [21].

- Set up qPCR reactions with 2.5-20μL reaction volumes, avoiding 1μL volumes which show markedly increased variability [21].

- Amplify using manufacturer-recommended cycling conditions with fluorescence acquisition.

- Analyze amplification curves with proper baseline setting (typically cycles 5-15) to avoid reaction stabilization artifacts [22].

- Set threshold in the logarithmic linear phase where all amplification plots are parallel [22].

- Generate standard curve by plotting Cq values against log10 template concentration.

- Calculate amplification efficiency using the formula: E = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) × 100% [22].

- Validate assay performance with R² ≥ 0.99 and efficiency of 90-105% [21].

Technical Notes: For low concentration targets (<50 copies/reaction), increase technical replicates to 5-24 to account for Poisson noise [21]. Determine Limit of Detection (LoD) by testing 24 replicates at 50, 20, and 5 copies per reaction [21].

Protocol 2: Assessing Correlation with Reference Methods

Purpose: To validate qPCR quantification accuracy against reference methods using well-characterized transcriptome reference materials.

Materials:

- Quartet or MAQC reference RNA samples [8]

- ERCC RNA spike-in controls [8]

- Reverse transcription reagents

- TaqMan assays or digital PCR systems for validation

Procedure:

- Extract RNA from reference samples (e.g., Quartet project samples: M8, F7, D5, D6) [8].

- Spike with ERCC RNA controls at defined ratios for built-in truth [8].

- Perform reverse transcription to cDNA using standardized protocols.

- Analyze samples by both qPCR and reference method (ddPCR or TaqMan) in parallel.

- Calculate Pearson correlation coefficients between qPCR results and reference datasets for protein-coding genes [8].

- For absolute quantification, compare with ERCC nominal concentrations (target r ≥ 0.964) [8].

- Assess accuracy of differential expression using known mixing ratios (e.g., 3:1 and 1:3 sample mixtures) [8].

Technical Notes: Target correlation coefficients of ≥0.876 with Quartet TaqMan datasets and ≥0.825 with MAQC TaqMan datasets for protein-coding genes [8]. Lower correlations are expected for broader gene sets, highlighting the importance of large-scale reference datasets for performance assessment [8].

Protocol 3: Quantifying Fold-Change Accuracy with Efficiency Correction

Purpose: To accurately measure expression fold changes between samples with proper efficiency correction and confidence interval estimation.

Materials:

- Test and control cDNA samples

- Validated reference gene assays

- Efficiency-corrected calculation tools

Procedure:

- Amplify target and reference genes in test and control samples with sufficient technical replication (≥3 replicates, increasing to ≥5 for high Cq targets) [21].

- Calculate ΔCq values for each sample (Cqtarget - Cqreference).

- Calculate ΔΔCq between test and control samples (ΔCqtest - ΔCqcontrol).

- Determine amplification efficiency for each assay from standard curve analysis.

- Apply efficiency-adjusted relative quantification model:

Ratio = (Etarget)^(-ΔΔCqtarget) / (Ereference)^(-ΔΔCqreference) [22]

Where E is the amplification efficiency (1.0 = 100% efficiency).

- Calculate confidence intervals from technical replicate data rather than relying on arbitrary thresholds [21].

- Report both fold change and 95% confidence intervals to distinguish technical noise from biological effects.

Technical Notes: Avoid the common assumption of 100% efficiency (2^(-ΔΔCq) method) as it significantly impacts fold change accuracy [22]. For inter-laboratory studies, account for platform-specific ΔCq variations that can produce 2.9-fold differences even with high intra-instrument reproducibility [21].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comprehensive qPCR Performance Assessment Workflow

Diagram 2: Fold Change Quantification with Efficiency Correction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for qPCR Benchmarking

| Reagent/Material | Function | Performance Specification |

|---|---|---|

| ddPCR-Quantified Standards | Baseline quantification for standard curves | Accurately characterized copy numbers for dynamic range assessment [21] |

| ERCC RNA Spike-In Controls | Built-in truth for quantification accuracy | 92 synthetic RNAs with known concentrations for correlation validation [8] |

| Quartet Reference RNA Samples | Homogenous transcriptome reference materials | Enable assessment of subtle differential expression detection [8] |

| MAQC Reference RNA Samples | Large biological difference controls | Benchmark performance for large fold changes [8] |

| Optimal Primer/Probe Sets | Target-specific amplification | High linearity (R² ≥ 0.99), efficiency 92-99% [21] |

| Multi-Platform Master Mixes | Consistent amplification chemistry | Compatible across different qPCR instruments for inter-platform studies [21] |

| Neuromedin N | Neuromedin N, CAS:102577-25-3, MF:C38H63N7O8, MW:745.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pritelivir mesylate | Pritelivir Mesylate|Helicase-Primase Inhibitor | Pritelivir mesylate is a potent helicase-primase inhibitor for herpes simplex virus (HSV) research. This product is For Research Use Only, not for human consumption. |

From Bench to Bedside: Methodological Applications in Research and Drug Discovery

Digital RNA with pertUrbation of Genes (DRUG-seq) is a high-throughput, cost-effective platform designed for comprehensive transcriptome profiling in drug discovery. It addresses a critical limitation in pharmaceutical screening: while high-throughput screening is a staple of discovery, current platforms often offer limited readouts. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is a powerful tool for investigating drug effects via transcriptome changes, but standard library construction is prohibitively costly for large-scale screens. DRUG-seq captures transcriptional changes detected in standard RNA-seq at 1/100th the cost, enabling its application in massive compound profiling campaigns [23].

The technology is engineered for miniaturization, functioning efficiently in both 384- and 1536-well formats. This allows researchers to screen vast collections of compounds across multiple doses, generating rich datasets on mechanism of action (MoA) and off-target activities. By forgoing RNA purification and employing a streamlined, multiplexed workflow, DRUG-seq drastically reduces library construction time and costs, making comprehensive transcriptome readout feasible in a high-throughput screening environment [23].

Technical Specifications and Benchmarking

DRUG-seq was developed to bridge the gap between the limited readouts of standard high-throughput screening and the comprehensive but expensive nature of traditional RNA-seq. The following table summarizes its key technical features and how it compares to other transcriptional profiling methods.

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput Transcriptomic Profiling Platforms

| Platform | Readout Type | Throughput Format | Cost per Sample (USD) | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRUG-seq | Whole transcriptome (3' end) | 384-well, 1536-well | $2 - $4 | Direct measurement of all genes at low cost | Focus on 3' end of transcripts |

| Standard RNA-seq | Whole transcriptome | 96-well (low throughput) | ~$200 - $400 (approx. 100x DRUG-seq) | Full-length transcript information; detects isoforms | High cost and labor for many samples |

| L1000/Luminex | ~1,000 "landmark" genes | High-throughput | Lower than standard RNA-seq | Extremely high throughput and cost-effective | Relies on imputation for genes not directly measured |

| Gene Expression Microarray | Pre-defined probe set | Varies | Varies | High accuracy for known sequences; fast | Cannot detect novel transcripts [24] |

The performance of DRUG-seq has been rigorously validated. In proof-of-concept experiments, it detected a median of 11,000 genes at a shallow sequencing depth of 2 million reads per well, increasing to 12,000 genes at 13 million reads. This captures the majority of biologically relevant transcripts and includes most of the landmark genes used in the L1000 platform [23]. Despite the lower read depth, DRUG-seq reliably identifies differentially expressed genes (DEGs), with compound potency measurements correlating well with those from the established Connectivity Map database (r = 0.80) [23]. This demonstrates that DRUG-seq provides a robust and quantitative readout of transcriptional perturbations for drug discovery.

Detailed DRUG-seq Experimental Protocol

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for conducting a DRUG-seq experiment, from cell seeding to data analysis.

The DRUG-seq workflow is designed for simplicity and automation, with key innovations that reduce hands-on time and cost.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Cell Seeding and Compound Treatment

- Seed osteosarcoma U2OS cells (or other relevant cell line) into a 384-well or 1536-well tissue culture plate using an automated liquid handler.

- Incubate until cells reach desired confluency.

- Treat cells with a library of compounds. A typical screen might involve 433 compounds across 8 doses (e.g., 10 μM, 3.2 μM, 1 μM, 0.32 μM, 0.1 μM, 32 nM, 10 nM, 3.2 nM), including DMSO vehicle controls, in triplicate [23].

- Incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 12 hours) to allow for transcriptomic changes to occur. This time should be optimized to balance detection of compound effectiveness and cytotoxicity.

Step 2: Cell Lysis and Reverse Transcription

- After treatment, lyse cells directly in the culture well. This step eliminates the need for RNA purification, a major cost and time savings [23].

- Perform reverse transcription (RT) immediately in the lysis buffer. The RT primer is critical and contains several functional elements:

- A poly(dT) sequence to capture mRNA.

- A well-specific barcode to label cDNA from each well, enabling multiplexing.

- A 10-nucleotide Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) to correct for PCR amplification biases and enable digital counting [23].

- The reverse transcriptase enzyme adds a poly(dC) sequence to the 3' end of the first-strand cDNA.

Step 3: cDNA Pooling and Library Construction

- Pool cDNA from all wells after the RT reaction. This drastically reduces downstream processing steps [23].

- Add a Template-Switching Oligo (TSO), which binds to the poly(dC) tail, allowing for pre-amplification of the cDNA pool by PCR.

- Use an enzymatic tagmentation reaction (e.g., with Tn5 transposase) to fragment the cDNA and add sequencing adapters in a single step.

- Perform a final, limited-cycle PCR to amplify the library and add full sequencing adapters.

- Purify the library using solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads and quantify.

Step 4: Sequencing and Data Analysis

- Sequence the library on an Illumina platform (e.g., HiSeq 4000) to a depth of approximately 2 million reads per well. This low depth is sufficient and contributes to the low cost [23].

- Process the raw sequencing data through a bioinformatic pipeline:

- Demultiplexing: Assign reads to samples based on the well-specific barcodes.

- UMI Processing: Collapse reads with identical UMIs to correct for PCR duplicates.

- Alignment: Map reads to a reference genome.

- Quantification: Generate a digital count matrix of genes x samples.

- Differential Expression: Identify genes significantly altered by compound treatment (e.g., |log2(Fold Change)| > 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05) [23].

- Clustering: Use techniques like t-SNE or hierarchical clustering to group compounds with similar transcriptional signatures and infer MoA.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and materials required to establish the DRUG-seq protocol in a laboratory setting.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DRUG-seq

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protocol | Key Features/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplexed RT Primer | Initiates cDNA synthesis and labels each well | Contains poly(dT), well-specific barcode, UMI, and priming sites for amplification [23]. |

| Template-Switching Oligo (TSO) | Enables PCR amplification after RT | Binds to poly(dC) tail added by reverse transcriptase to the 3' cDNA end [23]. |

| Master Mix | Cell lysis and reaction buffer | A proprietary formulation that allows for direct lysis and subsequent enzymatic reactions without RNA purification. |

| Tagmentation Enzyme Mix | Fragments cDNA and adds sequencing adapters | A hyperactive Tn5 transposase complexed with oligonucleotides (e.g., Illumina Nextera). |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Precise liquid transfer in microtiter plates | Essential for reproducibility in 384/1536-well formats for seeding, compound addition, and reagent dispensing. |

Application in Drug Discovery: Mechanism of Action Deconvolution

A primary application of DRUG-seq is the clustering of compounds based on their induced transcriptional signatures to elucidate their Mechanism of Action (MoA). In a landmark study profiling 433 compounds, DRUG-seq successfully grouped compounds into functional clusters by their intended targets [23].

For example, the platform clustered a compound with an unknown target (brusatol) with known translation inhibitors like homoharringtonine and cycloheximide. This clustering correctly suggested that brusatol's MoA involved targeting the translation machinery, a finding later supported by independent research [23]. The following diagram illustrates the analytical workflow for MoA deconvolution.

The analysis also revealed that compounds engaging the same target can show distinct dose-dependent kinetics in their transcriptome changes, providing insights into compound-specific potency and secondary effects. Furthermore, DRUG-seq can capture nuanced differences between compound treatment and genetic perturbation (e.g., CRISPR) on the same target, offering a more holistic view of target biology [23].

Translating RNA-seq from a research tool into clinical diagnostics requires the reliable detection of subtle differential expression, a key challenge when distinguishing between different disease subtypes, stages, or treatment responses [8]. These clinically relevant biological differences are often minor, manifesting in the detection of fewer differentially expressed genes (DEGs), and are challenging to distinguish from the technical noise inherent to RNA-seq workflows [8]. Unlike research environments with controlled protocols, real-world clinical scenarios present significant variations in sample processing, experimental protocols, sequencing platforms, and bioinformatics pipelines across different laboratories [8]. This article details application notes and protocols, framed within whole-transcriptome benchmarking research, to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility necessary for clinical application.

Experimental Design and Benchmarking for Subtle Expression Changes

Reference Materials and Study Design

A robust benchmarking study requires reference materials with well-characterized, subtle expression differences that mimic clinical samples.

- Quartet Reference Materials: Utilize multi-omics reference materials derived from immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines from a family quartet (parents and monozygotic twin daughters). These samples provide small inter-sample biological differences, exhibiting a number of DEGs comparable to clinically relevant sample groups [8].

- MAQC Reference Materials: For comparison, include established reference samples from the MicroArray/Sequencing Quality Control (SEQC/MAQC) Consortium, derived from ten cancer cell lines (MAQC A) and brain tissues (MAQC B), which feature larger biological differences [8].

- Spike-in Controls: Spike samples with synthetic RNA from the External RNA Control Consortium (ERCC) to provide an external standard for absolute quantification and process control [8].

- Sample Mixing: Prepare defined ratio mixtures (e.g., 3:1 and 1:3) of the Quartet samples to create a built-in truth for assessing quantification accuracy [8].

A typical study design involves distributing these reference materials to multiple laboratories, each employing its own in-house RNA-seq workflow, to assess inter-laboratory reproducibility [8].

Workflow for a Multi-Center Benchmarking Study

The following diagram illustrates the foundational workflow for a multi-center benchmarking study, from sample preparation to data integration.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

- Input Material: Use 50-500 ng of high-quality total RNA with an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) greater than 8.0.

- Protocol: Extract RNA using a silica-membrane column-based kit. Preferentially use kits that include a DNase I digestion step to remove genomic DNA contamination. Quantify the purified RNA using a fluorometric method and verify integrity with a microfluidic electrophoresis system.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Critical choices during library preparation significantly impact the ability to detect subtle expression changes.

- mRNA Enrichment: Perform poly-A selection for mRNA enrichment. This step is a primary source of variation; strict adherence to protocol is essential to maintain mRNA integrity and representation [8].

- Library Strandedness: Use a stranded library preparation protocol. This preserves the strand information of the originating transcript, which is crucial for accurate quantification, especially for genes with overlapping transcripts, and is identified as a key factor affecting inter-laboratory consistency [8].

- Library Construction: Convert RNA into a sequencing library using a reverse transcription kit with template switching oligo (TSO) technology. Use a double-stranded cDNA synthesis module, followed by end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation. Amplify the final library with a limited number of PCR cycles (e.g., 12-15) to minimize duplication bias.

- Sequencing: Sequence the libraries on a platform of choice to a minimum depth of 30 million paired-end (2x150 bp) reads per sample. Ensure sequencing is performed across multiple flow cells or lanes to introduce and account for batch effects reflective of real-world conditions [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for ensuring reliable RNA-seq in a clinical diagnostic context.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Quartet & MAQC Reference Materials [8] | Provides "ground truth" samples with known, subtle expression differences for benchmarking and quality control. | Homogeneity, stability, and well-characterized transcriptome profiles. |

| ERCC Spike-in Mix [8] | Synthetic RNA controls spiked into samples to monitor technical performance and enable absolute quantification. | Known concentration ratios provide a built-in truth for assessment. |

| Stranded mRNA-seq Kit | For library preparation with poly-A selection and strand information retention. | High efficiency, low bias, and compatibility with low-input samples. |

| RT-qPCR Assay Kits [25] | Used for orthogonal validation of gene expression levels (e.g., TaqMan assays). | PCR efficiency between 85-110% is critical for accurate results [25]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines [8] | Computational tools for read alignment, gene quantification, and differential expression analysis. | Choice of alignment and quantification tools significantly impacts results. |

| Proadifen | Proadifen, CAS:62-68-0, MF:C23H31NO2, MW:353.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pronethalol | Pronetalol | Pronetalol, the first beta-blocker. A key compound for adrenergic receptor research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

Computational Analysis and Data Interpretation

Bioinformatics Pipeline for Differential Expression

A standardized yet flexible pipeline is required to assess the impact of various bioinformatics tools. The following framework allows for systematic benchmarking.

Performance Assessment Metrics

Systematically evaluate the generated data using multiple, orthogonal metrics to form a comprehensive performance assessment framework [8].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for RNA-seq Benchmarking

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Description and "Ground Truth" Used |

|---|---|---|

| Data Quality | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) [8] | PCA-based metric assessing the ability to distinguish biological signals from technical noise in replicates. Calculated using both Quartet and MAQC samples. |

| Expression Accuracy | Pearson Correlation [8] | Accuracy of absolute gene expression levels, measured against orthogonal TaqMan datasets for Quartet and MAQC samples. |

| Spike-in Performance | Correlation with Nominal Concentration [8] | Accuracy of quantification for the 92 ERCC spike-in RNAs with known concentrations. |

| DEG Accuracy | Precision and Recall [8] | Accuracy of the final differentially expressed gene (DEG) list, benchmarked against a reference DEG dataset established for the Quartet and MAQC samples. |

Interpreting qPCR Validation Data

RT-qPCR is a standard method for orthogonal validation of RNA-seq findings. Proper interpretation of the data is crucial.

- Cycle Threshold (Ct): The intersection between an amplification curve and a threshold line; a relative measure of the concentration of the target in the PCR reaction [25]. Lower Ct values indicate higher starting quantities of the target.

- PCR Efficiency: A ratio of the number of amplified target DNA molecules at the end of the PCR cycle to the number at the beginning. It is calculated from a standard curve of serial dilutions using the formula: Efficiency (%) = (10^(-1/Slope) - 1) x 100 [25]. An efficiency between 85% and 110% is acceptable.

- Relative Quantification (Livak Method): A common method to compare gene expression, which assumes PCR efficiencies of target and reference genes are approximately equal and near 100% [25]. It uses the formulae:

- ∆Ct = Ct(target) - Ct(reference)

- ∆∆Ct = ∆Ct(treatment) - ∆Ct(control)

- Fold Change = 2^(-∆∆Ct)

Key Findings and Best Practice Recommendations

Large-scale benchmarking reveals major sources of variation and informs the following best practices.

Table 2: Summary of Factors Influencing RNA-seq Reproducibility

| Process Stage | Key Influencing Factors | Best Practice Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental | mRNA enrichment protocol, library strandedness, experimental execution. | Use stranded library preparation protocols. Execute mRNA enrichment steps with rigorous consistency. Acknowledge that laboratory execution is as critical as protocol choice [8]. |

| Bioinformatics | Gene annotation source, read alignment tool, quantification method, normalization strategy. | Provide a detailed analysis pipeline. Strategically filter low-expression genes. Select optimal gene annotation and analysis pipelines based on benchmarked performance [8]. |

| Quality Assessment | Reliance on reference materials with large biological differences. | Implement quality control using reference materials like the Quartet samples that reflect subtle differential expression, as quality issues are more easily detected this way [8]. |

The translation of RNA-seq into clinical diagnostics for detecting subtle differential expression is challenging but achievable through rigorous benchmarking and standardized practices. The use of appropriate reference materials, careful attention to both experimental and computational steps, and quality control based on subtle expression differences are fundamental to ensuring reliable and reproducible results. The protocols and application notes detailed here provide a framework for laboratories to develop and validate RNA-seq assays suitable for sensitive clinical applications.

Benchmarking Single-Cell and Long-Read RNA-Seq Protocols

The advancement of RNA sequencing technologies has moved transcriptomic research from bulk-level analysis to a high-resolution focus on individual cells and full-length isoforms. This evolution is critical for understanding cellular heterogeneity and the functional impact of alternative splicing, areas that are foundational to modern drug discovery and development. Framed within the context of whole-transcriptome qPCR benchmarking research, which establishes a "ground truth" through precise, ratio-based measurements, this application note provides a systematic evaluation of single-cell (scRNA-seq) and long-read RNA-seq (lrRNA-seq) protocols. We summarize key performance benchmarks from recent large-scale consortium studies, detail standardized experimental methodologies, and provide a curated toolkit to guide researchers in selecting and implementing these transformative technologies.

Performance Benchmarks and Quantitative Comparisons

Recent multi-platform studies have generated comprehensive data to objectively compare the performance of various RNA-seq technologies. The tables below summarize key quantitative findings on sequencing performance and analytical accuracy.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Long-Read RNA-Seq Technologies

| Sequencing Platform/ Protocol | Typical Read Length | Throughput (Million Reads per run) | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) direct RNA | Full-length, ultra-long | ~20 M [26] | Sequences native RNA; enables detection of RNA modifications [27] [26] | Lower throughput; higher error rates [26] [28] |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) direct cDNA | Full-length | ~130 M [26] | Amplification-free; reduces bias [27] | Requires more input RNA [27] |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) PCR-cDNA | Full-length | High (~130 M) [26] | High throughput; low input requirement [27] | PCR amplification biases [27] |

| PacBio Iso-Seq | Full-length, high accuracy | Varies | High base-level accuracy; superior for novel isoform discovery [29] | Higher cost per sample; lower throughput than ONT [27] |

| Illumina Short-Read | 50-300 bp | Very High | High accuracy for gene-level quantification; low cost [8] [28] | Cannot resolve full-length isoforms [30] [27] |

Table 2: Analytical Accuracy in Transcript Identification (LRGASP Consortium Findings)

| Analysis "Challenge" | Best Performing Approach | Key Performance Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Challenge 1: Transcript Isoform Detection | Reference-based tools (e.g., Bambu, IsoQuant) [28] | Longer, more accurate reads (PacBio) outperform increased depth for accuracy [28]. |

| Challenge 2: Transcript Quantification | Tools utilizing greater sequencing depth [28] | Long-read quantification lags behind short-read tools due to throughput and error rate [28]. |

| Challenge 3: De Novo Transcript Discovery | Multi-tool, orthogonal validation approach [28] | PacBio demonstrates superior accuracy in identifying novel transcripts and allele-specific expression [29]. |

Table 3: Single-Cell RNA-Seq Protocol Comparison

| Protocol | Cell Isolation | Transcript Coverage | UMI | Amplification Method | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart-Seq2 [31] | FACS | Full-length | No | PCR | Detecting low-abundance transcripts & isoforms |

| CEL-Seq2 [31] | FACS | 3'-only | Yes | IVT | High-throughput, reduced amplification bias |

| Drop-Seq [31] | Droplet-based | 3'-end | Yes | PCR | Profiling thousands of cells at low cost |

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Droplet-based | 3'-end or 5'-end | Yes | PCR | Standardized high-throughput cell typing |

| SPLiT-Seq [31] | Combinatorial Indexing | 3'-only | Yes | PCR | Fixed or very large numbers of cells |

A pivotal finding from the LRGASP consortium is that while lrRNA-seq excels at discovering novel transcripts, its accuracy in quantifying transcript abundance is currently inferior to well-established short-read methods [28]. This highlights the complementary nature of these technologies. For single-cell analysis, third-generation sequencing (TGS) platforms like PacBio and ONT can be applied to single-cell cDNA libraries, successfully capturing cell types and enabling isoform-level analysis, though with lower gene detection sensitivity due to limited sequencing throughput [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Multi-Platform Long-Read RNA-Seq Benchmarking Workflow

This protocol is adapted from the SG-NEx and LRGASP projects to enable robust comparison of lrRNA-seq methods [27] [28].

1. Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction

- Starting Material: Use universal reference RNA or well-characterized cell lines (e.g., HCT116, HepG2, WTC11) to ensure comparability across labs.

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA using a silica-membrane column method with DNase I treatment. Assess RNA integrity using an Agilent Bioanalyzer; only proceed with samples having an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) > 8.5.

- Spike-in Controls: Spike in known quantities of synthetic RNA controls (e.g., ERCC, Sequin, SIRVs) prior to library preparation. This provides an internal standard for assessing quantification accuracy, sensitivity, and dynamic range [8] [27].

2. Library Preparation for Multiple Platforms

- ONT Direct RNA Sequencing: Use the SQK-RNA002 kit. Do not perform PCR amplification. This protocol preserves native RNA modifications but yields lower throughput [27] [26].

- ONT Direct cDNA Sequencing: Use the SQK-DCS109 kit. This protocol is amplification-free, reducing biases associated with PCR, but requires 1-5 µg of high-quality total RNA [27].

- ONT PCR-cDNA Sequencing: Use the SQK-PCS109 kit. This protocol is ideal for low-input samples (10-100 ng total RNA) and generates the highest throughput for ONT, but may introduce amplification biases [27].

- PacBio HiFi Iso-Seq: Prepare libraries according to the SMRTbell prep kit protocol. Aim to generate full-length cDNA using the Clontech SMARTer PCR cDNA Synthesis Kit. Size-select the libraries (e.g., using the BluePippin system) to enrich for longer transcripts [27] [28].

3. Sequencing and Data Generation

- Sequencing: Sequence each library on the respective platform. The SG-NEx project recommends a minimum of 3 technical replicates per protocol and a target of 100 million long reads per core cell line for robust analysis [27].

- Quality Control: Perform base-calling (for ONT) or circular consensus sequencing (CCS) analysis (for PacBio) with platform-specific tools (e.g., Guppy, Dorado).

4. Data Processing and Analysis

- Alignment: Map reads to the reference genome using specialized long-read aligners (e.g., Minimap2).

- Transcriptome Reconstruction: Process the aligned reads through multiple bioinformatic pipelines (e.g., Bambu, IsoQuant, FLAIR) for transcript identification and quantification [28].

- Benchmarking Metrics:

- Sensitivity & Precision: Calculate the number of known transcripts correctly identified versus the number of false-positive novel transcripts, using spike-ins and reference annotations as ground truth.

- Quantification Accuracy: Assess the correlation of transcript-level abundance estimates with known spike-in concentrations and with orthogonal qPCR validation data [8] [28].

- Analysis of Novelty: Use SQANTI3 to categorize discovered transcripts into structural categories (FSM, ISM, NIC, NNC) and prioritize those with orthogonal support [26] [28].

Protocol 2: Integrating Long-Read Sequencing with Single-Cell RNA-Seq

This protocol outlines the process for applying long-read sequencing to single-cell libraries to resolve transcript isoforms at the cellular level [29].

1. Single-Cell Library Preparation

- Cell Isolation: Use a high-viability (>90%) single-cell suspension. Isolate cells using a droplet-based method (e.g., 10x Genomics) or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

- cDNA Synthesis: Generate full-length cDNA from single cells using a template-switching protocol (e.g., Smart-Seq2) to preserve complete transcript information [31].

- Library Amplification: Amplify cDNA by LD PCR for a limited number of cycles to minimize bias.

2. Long-Read Sequencing of scRNA-seq Libraries

- Pooling and Shearing: Pool amplified single-cell cDNAs and shear them to an optimal size for long-read sequencing (e.g., ~2-3 kb for ONT).

- Library Preparation: Prepare a long-read sequencing library from the pooled, sheared cDNA using the ONT PCR-cDNA kit (SQK-PCS109) or the PacBio Iso-Seq protocol.

- Sequencing: Sequence the library on the chosen long-read platform. Note that due to pooling, the resulting long reads cannot be automatically assigned to individual cells.

3. Data Deconvolution and Analysis

- Cell Barcoding: During the initial single-cell library prep, ensure that each cell's transcripts are tagged with a unique barcode (UBI) and cell barcode.

- Bioinformatic Deconvolution: Map long reads to the reference genome. Assign each long read back to its cell of origin by matching the embedded cell barcode and UMI. This creates a gene and isoform expression matrix per cell [29].

- Validation: Compare the cell type identification and clustering results from the long-read data with those generated from the same libraries sequenced on a short-read platform to validate performance [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for RNA-Seq Benchmarking

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Products/ Kits |

|---|---|---|

| Reference RNA Materials | Provides a consistent, homogeneous standard for cross-lab comparison and quality control. | Quartet Project RNA Reference Materials [8]; MAQC Reference RNA [8] |

| Spike-in RNA Controls | In-process controls for absolute quantification, sensitivity, and dynamic range assessment. | ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix [8]; Sequin RNA Spike-ins [27]; SIRV Spike-ins [27] |

| Full-Length cDNA Synthesis Kit | Ensures high-quality, unbiased reverse transcription for long-read sequencing. | Clontech SMARTer PCR cDNA Synthesis Kit [28] |

| Long-Range PCR Enzyme | Amplifies full-length cDNA with high fidelity and yield for PacBio and ONT cDNA protocols. | KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix |

| Magnetic Bead-Based Cleanup | For efficient size selection and cleanup of long cDNA fragments and sequencing libraries. | AMPure XP Beads |

| Library Prep Kits (ONT) | Standardized reagents for preparing sequencing-ready libraries. | ONT Direct RNA Seq Kit (SQK-RNA002); ONT PCR-cDNA Seq Kit (SQK-PCS109) [27] |

| Library Prep Kits (PacBio) | For constructing SMRTbell libraries for Iso-Seq. | SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 |

| Cell Barcoding Kits (scRNA-seq) | Enables high-throughput, multiplexed single-cell analysis. | 10x Genomics Single Cell 3' Reagent Kits |

| (+)-Sparteine | High-purity (+)-Sparteine for research applications. A valuable chiral ligand in organic synthesis. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | |

| Palbociclib hydrochloride | Palbociclib hydrochloride, CAS:827022-32-2, MF:C24H30ClN7O2, MW:484.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of single-cell and long-read RNA-seq technologies represents a powerful frontier in transcriptomics, moving beyond simple gene-level quantification to reveal the intricate landscape of isoform diversity across individual cells. As benchmarked against the rigorous standards of whole-transcriptome qPCR research, these protocols offer unprecedented resolution. However, the choice of technology and analysis pipeline must be guided by the specific biological question, weighing the need for high-throughput cell typing against the demand for full-length isoform resolution. The ongoing development of more accurate sequencing chemistries, higher-throughput platforms, and robust bioinformatic tools will continue to close the current performance gaps, further solidifying the role of these technologies in foundational research and clinical application.

In modern drug discovery, elucidating the Mechanism of Action (MOA) of a compound—the biological pathway through which it exerts its therapeutic effect—is a fundamental challenge. The advent of high-throughput transcriptomic technologies has made the analysis of genome-wide gene expression changes a powerful proxy for understanding MOA. The core hypothesis is that drugs sharing similar MOAs will induce similar transcriptional signatures, often described as the "guilt-by-association" principle [32] [33]. This case study details the application of transcriptomic profiling and computational clustering to group drugs by their MOAs, providing a critical tool for drug repurposing and the de novo characterization of novel compounds.

Key Technologies in Pharmacotranscriptomics

Pharmacotranscriptomics-based drug screening (PTDS) has emerged as a distinct class of drug screening, alongside target-based and phenotype-based approaches [34]. Several technologies enable the generation of transcriptional signatures for MOA studies.

The table below summarizes the primary transcriptomic profiling platforms used in high-throughput screening:

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput Transcriptomic Profiling Platforms

| Technology | Profiling Scope | Throughput | Key Features and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DRUG-seq [23] | Whole transcriptome (unbiased) | 384-/1536-well format | Cost-effective (~$2-4/sample); digital counting of 3' end transcripts; groups compounds into functional clusters by MOA. |

| L1000 Assay [35] | 978 "Landmark" genes + ~11,000 inferred genes | High | Used in LINCS/CMap database; cost-effective; connects small molecules, genes, and diseases via gene-expression signatures. |

| Gene Expression Microarray [24] | Pre-defined probe sets | High | High accuracy in screening differentially expressed genes after qPCR verification; used in drug screening and biomarker detection. |

| Standard RNA-seq [24] | Whole transcriptome (unbiased) | Lower throughput & higher cost than targeted methods | Provides deeper interrogation of complex changes; broader application prospects, especially with single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq). |

Computational Workflow for MOA Clustering

The process of clustering drugs by MOA using their transcriptional signatures involves a multi-step computational workflow, from data generation to pattern recognition.

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of a standard analysis:

Figure 1. Overall workflow for clustering drug MOAs.