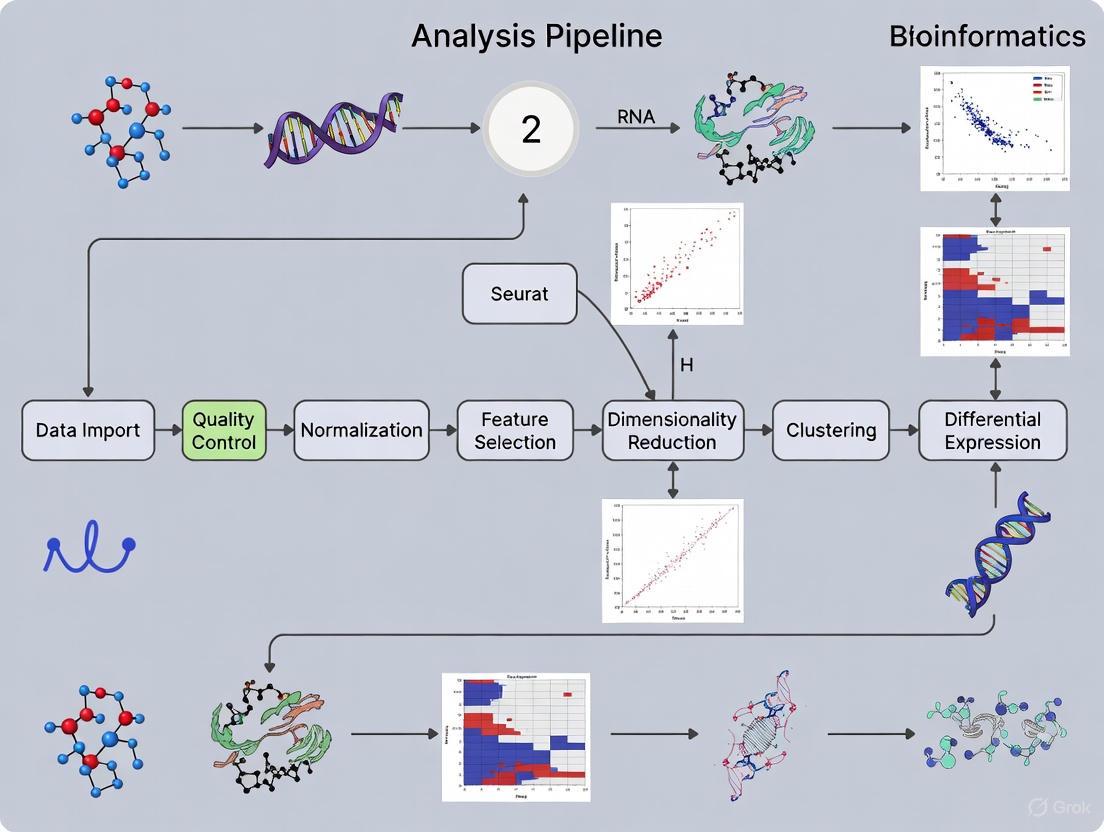

A Comprehensive Guide to Building a Robust Single-Cell RNA-Seq Analysis Pipeline with Seurat

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for implementing a single-cell RNA-seq analysis pipeline using the Seurat toolkit.

A Comprehensive Guide to Building a Robust Single-Cell RNA-Seq Analysis Pipeline with Seurat

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for implementing a single-cell RNA-seq analysis pipeline using the Seurat toolkit. Covering the entire workflow from foundational quality control and data exploration to advanced integration techniques and spatial transcriptomics, it offers practical, step-by-step guidance. The content also addresses critical troubleshooting for large-scale projects and benchmarking for method validation, empowering users to generate biologically insightful and reproducible results for biomedical and clinical research.

Laying the Groundwork: Quality Control, Normalization, and Initial Clustering

Setting Up the Seurat Object and Understanding Count Matrix Structure

In single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis, the count matrix represents the fundamental data structure from which all subsequent biological insights are derived. This matrix quantifies gene expression at the single-cell level, where each entry contains the number of RNA molecules originating from a specific gene within an individual cell [1]. The precise construction and interpretation of this matrix is therefore a critical first step in any scRNA-seq analysis pipeline.

Depending on the library preparation method used, sequencing reads can be derived from either the 3' ends of transcripts (10X Genomics, Drop-seq, inDrops) or from full-length transcripts (Smart-seq2) [2]. For the increasingly popular 3' end sequencing methods used in droplet-based platforms, the resulting data incorporates unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) that enable distinction between biological duplicates and technical amplification duplicates [2]. This technical consideration directly influences how the count matrix is constructed and interpreted.

The Seurat package for R provides a comprehensive toolkit for scRNA-seq analysis, with the Seurat object serving as a centralized container that integrates both raw data (like the count matrix) and analytical results (such as clustering or differential expression) [3] [4]. Establishing a properly formatted Seurat object with correctly interpreted count data establishes the foundation for all downstream analyses including cell clustering, marker identification, and trajectory inference.

Composition and Generation of the Count Matrix

Fundamental Components

A scRNA-seq count matrix is structured with genes as rows and cells as columns, where each value represents the expression level of a particular gene in a specific cell [5]. For droplet-based methods employing UMIs, these values typically represent the number of deduplicated UMIs mapped to each gene, providing a digital measure of gene expression that is resistant to PCR amplification biases [2].

The generation of a count matrix from raw sequencing data requires several processing steps that vary depending on the experimental protocol. For 10X Genomics data, the Cell Ranger software suite provides a customized pipeline that aligns reads to the reference genome using STAR and counts UMIs per gene [5]. Alternative approaches include pseudo-alignment methods such as alevin, which can process data more quickly by avoiding explicit alignment [5]. For other multiplexed protocols, more generalized tools like scPipe can process the data using the Rsubread aligner [5].

Key Information Elements

The construction of a proper count matrix relies on several crucial information components extracted from the sequencing data [2]:

- Cellular barcode: A unique nucleotide sequence that identifies which cell each read originated from

- Unique molecular identifier (UMI): A random nucleotide sequence that distinguishes individual mRNA molecules, enabling PCR duplicate removal

- Gene identifier: The specific gene transcript from which the read originated

Table 1: Essential Components of scRNA-seq Sequencing Data

| Component | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Barcode | Identifies cell of origin | 10X Chromium: 16 nucleotides |

| UMI | Identifies individual molecules | 10-12 random nucleotides |

| Gene Identifier | Maps reads to genes | ENSG00000139618 (BRCA2) |

These components are protocol-specific. For example, in 10X Genomics data, the cellular barcode and UMI are contained in Read 1, while the gene sequence is in Read 2. For inDrops v3, this information is distributed across four separate reads [2].

From Sequencing to Count Matrix

The transformation of raw sequencing data into a count matrix follows a standardized workflow regardless of the specific droplet-based method used [2]. After obtaining FASTQ files from the sequencing facility, the process involves:

- Read formatting and barcode filtering: Extracting cellular barcodes and UMIs, then filtering out low-quality barcodes

- Sample demultiplexing: Separating reads from different samples using sample barcodes

- Mapping/pseudo-mapping: Aligning reads to a reference genome or transcriptome

- UMI collapsing and quantification: Removing PCR duplicates and generating final counts per gene per cell

This process yields the final count matrix where each value represents the number of deduplicated UMIs (or reads for full-length protocols) mapped to each gene in each cell [2].

Creating the Seurat Object

Reading in Count Data

The first step in Seurat analysis is importing the count matrix into R and creating a Seurat object. For data processed through the 10X Genomics pipeline, Seurat provides the Read10X() function, which reads the output directory of Cell Ranger and returns a UMI count matrix [3]. This matrix can then be used to create a Seurat object:

The CreateSeuratObject() function requires the count matrix as its primary input, with cells as columns and features (genes) as rows [6]. Key parameters include min.cells, which filters out genes detected in fewer than this number of cells, and min.features, which filters out cells containing fewer than this number of detected genes [6].

Structure of the Seurat Object

The Seurat object employs an organized structure to store various types of data throughout the analysis workflow [7]. Key components include:

- Assays: Container for expression data (e.g., RNA, SCT), with slots for raw counts, normalized data, and scaled data

- meta.data: Data frame storing cell-level metadata including QC metrics

- reductions: Dimensionality reductions (PCA, UMAP, etc.)

- graphs: Nearest neighbor graphs used for clustering

- active.ident: Current cell identity classes

Table 2: Key Slots in the Seurat Object

| Slot | Contents | Access Method |

|---|---|---|

| assays | Expression data (counts, normalized data) | pbmc[["RNA"]] |

| meta.data | Cell-level metadata | pbmc@meta.data or pbmc$nFeature_RNA |

| reductions | Dimensionality reductions | pbmc[["pca"]] |

| active.ident | Current cell identities | Idents(pbmc) |

| graphs | Neighbor graphs for clustering | pbmc[["RNA_nn"]] |

Upon creation, the Seurat object automatically computes and stores basic QC metrics in the meta.data slot, including nCount_RNA (total UMIs per cell) and nFeature_RNA (number of genes detected per cell) [3] [4]. These metrics form the basis for subsequent quality control steps.

Quality Control and Count Matrix Filtering

QC Metrics Calculation

After creating the Seurat object, additional QC metrics should be calculated to identify potentially problematic cells. A particularly important metric is the percentage of mitochondrial reads, which serves as an indicator of cell viability [3] [4]. This can be calculated and added to the object metadata using:

The mitochondrial percentage is biologically informative because low-quality or dying cells often exhibit extensive mitochondrial contamination due to impaired membrane integrity [3]. Similarly, unusually high or low numbers of detected genes can indicate doublets/multiplets or low-quality cells respectively [4].

Data Filtering Thresholds

Appropriate filtering thresholds depend on the biological system and technology used, but general guidelines exist. Typical approaches include [3] [1]:

- Filtering cells with unique gene counts outside expected ranges (typically 200-2,500 for standard 10X protocols)

- Removing cells with excessively high mitochondrial content (often >5-15%)

- Eliminating genes detected in very few cells (default min.cells = 3 in Seurat)

Table 3: Standard QC Thresholds for scRNA-seq Data

| QC Metric | Typical Threshold | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| nFeature_RNA (lower bound) | 200-500 | Removes empty droplets/low-quality cells |

| nFeature_RNA (upper bound) | 2,500-5,000 | Removes doublets/multiplets |

| percent.mt | 5-15% | Removes dying/low viability cells |

| min.cells | 3 | Removes rarely detected genes |

These thresholds can be visualized using violin plots or scatterplots to identify appropriate cutoffs before applying them with the subset() function [3]:

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Analysis

| Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Ranger (10X Genomics) | Processing raw sequencing data to count matrix | 10X Genomics library preparations |

| STARsolo | Alignment and quantification of scRNA-seq data | Alternative to Cell Ranger, faster processing |

| Seurat Package | Comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis platform | Primary tool for downstream analysis |

| GENCODE Annotation | Comprehensive gene annotation reference | Improved read assignment versus RefSeq |

| UCSC/Ensembl Genome Browser | Reference genome sequences | Essential for read alignment |

| bcl2fastq | Conversion of BCL to FASTQ format | Processing raw sequencing output |

| DoubletFinder/scds | Doublet detection algorithms | Identifying multiplets in droplet data |

Count Matrix Characteristics and Storage

Sparse Matrix Representation

scRNA-seq data is characterized by an abundance of zero values, as each individual cell expresses only a fraction of the total transcriptome. This sparsity makes efficient storage crucial for managing computational resources [3]. Seurat automatically uses sparse matrix representations whenever possible, resulting in significant memory savings:

In typical analyses, sparse matrix representations can reduce memory usage by 20-fold or more compared to dense matrices [3]. This efficiency becomes increasingly important as dataset sizes grow into the tens or hundreds of thousands of cells.

Count Matrix Inspection

Direct examination of the count matrix can provide valuable insights into data quality and structure. Seurat enables focused inspection of specific genes across subsets of cells [3]:

This examination typically reveals the sparse nature of the data, with most entries represented as zeros (indicated by "." in the output) [3]. Understanding this sparsity is essential for selecting appropriate analytical approaches in downstream steps.

The creation of a properly structured Seurat object and thorough understanding of count matrix composition establish the critical foundation for any successful single-cell RNA sequencing analysis. The count matrix, with genes as rows and cells as columns, encapsulates the essential gene expression information extracted through specialized processing of raw sequencing data [2] [5]. Implementation of appropriate quality control measures, including filtering based on detected gene counts and mitochondrial percentage, ensures that downstream analyses reflect biological reality rather than technical artifacts [3] [1].

The structured organization of the Seurat object provides an efficient framework for maintaining data integrity throughout the analytical workflow, seamlessly integrating raw counts, normalized values, cell metadata, and analytical results [7]. By establishing this robust foundation during the initial phases of analysis, researchers position themselves to extract biologically meaningful insights from their single-cell data through subsequent clustering, differential expression, and trajectory analysis procedures.

Within the framework of establishing a robust single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis pipeline using Seurat, quality control (QC) represents a critical first computational step. The primary goals of QC are to filter the data to retain only high-quality, genuine cells and to identify any failed samples, thereby ensuring that subsequent analyses like clustering accurately reflect distinct biological cell type populations rather than technical artifacts [8]. This process is challenging because it requires distinguishing between poor-quality cells and biologically relevant but less complex cell types, all while choosing appropriate filtering thresholds to avoid discarding valuable biological information [8] [9]. This protocol outlines a comprehensive methodology for assessing cell quality based on three cornerstone metrics: the number of detected genes per cell (nFeature_RNA), the total number of UMIs per cell (nCount_RNA), and the percentage of reads mapping to the mitochondrial genome (percent.mt).

Key Quality Control Metrics and Their Biological Interpretation

The following table summarizes the core QC metrics used for filtering cells in a scRNA-seq experiment, detailing their technical interpretations and biological significance.

Table 1: Key QC Metrics for Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data

| Metric | Description | Indication of Low Quality | Biological Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

nFeature_RNA |

Number of unique genes detected per cell [3]. | Very few genes: empty droplets or heavily degraded cells [3] [10]. | Low complexity can be a genuine feature of quiescent cell populations or small cells [10]. |

nCount_RNA |

Total number of RNA molecules (UMIs) detected per cell [3]. | Low counts: ambient RNA or non-cell entities [10]. | Cells with high counts may be larger or metabolically active; extreme highs can suggest multiplets [8] [3]. |

percent.mt |

Percentage of mitochondrial transcript counts per cell [3]. | High percentage: cellular stress, apoptosis, or broken membranes [3] [10]. | Certain cell types involved in respiration may naturally have higher mitochondrial activity [10]. |

The interplay of these metrics is crucial for accurate QC decision-making. As visually summarized in the workflow below, the process involves calculating these metrics, performing a joint assessment through visualization, and applying informed thresholds to remove low-quality cells.

Materials and Methods

Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and computational tools are essential for executing the QC workflow described in this protocol.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for scRNA-seq QC

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Ranger | Software suite for processing raw sequencing data from 10X Genomics assays into a count matrix [9]. | Version 7.0+ incorporates intronic reads in UMI counting by default [9]. |

| Seurat R Package | Comprehensive toolkit for the loading, processing, analysis, and exploration of scRNA-seq data [3] [10]. | The central environment for executing the entire QC protocol. |

| Loupe Browser | 10X Genomics' visual software for preliminary data exploration and cell filtering [9]. | Provides an intuitive interface for visual QC with real-time feedback [9]. |

| Mitochondrial Gene Set | A predefined set of genes used to calculate the percentage of mitochondrial reads. | Pattern is species-specific: "^MT-" for human, "^mt-" for mouse [3] [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

Step 1: Calculation of QC Metrics

After initializing a Seurat object, the first step is to compute the key QC metrics, including the mitochondrial percentage.

Code Chunk 1: Calculating Mitochondrial Percentage and Metadata Preparation

Step 2: Visualization and Joint Assessment of QC Metrics

Visualization is critical for understanding the distributions of QC metrics and their correlations, which informs the setting of appropriate thresholds.

Code Chunk 2: Generating Multi-Metric QC Plots

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making logic for interpreting these visualizations and identifying cells that should be filtered out.

Step 3: Application of Filtering Thresholds

Based on the visual assessment, filter the Seurat object to retain only high-quality cells. The following table provides common starting thresholds, which must be tailored to the specific biological context of the experiment [3] [10].

Table 3: Example Thresholds for Cell Filtering

| Metric | Typical Lower Bound | Typical Upper Bound | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

nFeature_RNA |

200 - 500 [3] [10] | 2000 - 6000 (dataset-dependent) | Removes empty droplets and filters potential multiplets. |

nCount_RNA |

500 - 1000 [8] [10] | Typically derived in correlation with nFeature_RNA |

Filters cells with low sequencing depth. |

percent.mt |

- | 5% - 20% (biology-dependent) [3] [10] | Removes stressed, dying, or low-quality cells. |

Code Chunk 3: Filtering the Seurat Object

Discussion

Implementing rigorous quality control is a foundational step in any scRNA-seq analysis pipeline. The protocol described here leverages the Seurat package to filter cells based on three cardinal metrics, providing a balance between removing technical artifacts and preserving biological heterogeneity. A key consideration is that thresholds are not universal; they must be informed by the biological context. For instance, thresholds for nFeature_RNA and nCount_RNA can vary significantly based on the cell capture technology and the sequencing depth [8] [11], while the cutoff for percent.mt must be adjusted if the biological sample contains inherently high mitochondrial activity, such as in metabolically active tissues [10].

Furthermore, researchers should be aware that current best practices recommend a more permissive approach to filtering, as overly aggressive thresholds can lead to the loss of rare but biologically genuine cell populations [10]. While this protocol focuses on standard metrics, the field is evolving with dedicated tools for addressing specific challenges like doublet detection (e.g., Scrublet, DoubletFinder) and ambient RNA removal (e.g., SoupX) [8] [10], which can be integrated for a more sophisticated QC pipeline. Ultimately, the decisions made at this initial stage profoundly impact all downstream analyses, from dimensionality reduction and clustering to the final biological interpretations, making careful and documented QC an indispensable component of reproducible single-cell research.

In the analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data, normalization is a critical preprocessing step designed to remove technical variability, such as differences in sequencing depth between cells, thereby enabling meaningful biological comparisons [12]. Without effective normalization, technical artifacts can confound biological signals, severely impacting downstream analyses like clustering, dimensional reduction, and differential expression [12]. Within the widely used Seurat toolkit, two primary normalization methodologies are employed: the conventional LogNormalize approach and the more recently developed SCTransform (Single-Cell Transform) [13] [3] [14]. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for implementing these strategies within a robust single-cell RNA-seq analysis pipeline, framed for researchers and drug development professionals.

The fundamental challenge addressed by normalization is the heteroskedasticity of count data, where the variance of a gene's counts depends strongly on its mean expression level [15]. Technical factors, most notably varying sequencing depths (total UMIs per cell), can create differences in observed counts that are not reflective of true biological states [13] [12]. The goal of any normalization procedure is to mitigate these technical effects while preserving and highlighting the biological heterogeneity of interest.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Frameworks

The LogNormalize Method

The LogNormalize method, often referred to as global-scaling normalization, operates on a relatively straightforward principle. It normalizes the feature expression measurements for each cell by the total expression for that cell, multiplies this by a scale factor (defaulting to 10,000), and then log-transforms the result [3]. This process can be summarized by the following equation for a count ( y_{gc} ) of gene ( g ) in cell ( c ):

[ \text{Normalized Expression} = \ln\left( \frac{y{gc}}{\sum{g} y_{gc}} \times \text{scale.factor} + 1 \right) ]

The addition of 1 (a pseudo-count) prevents taking the logarithm of zero. This method implicitly assumes that each cell was originally expected to contain the same number of RNA molecules—an assumption that does not always hold true in real-world single-cell experiments [3] [14]. Following normalization, the data is typically scaled (a z-score transformation) such that the mean expression across cells is 0 and the variance is 1 for each gene, giving equal weight to all genes in downstream analyses [3] [16].

The SCTransform Method

SCTransform represents a significant methodological advancement by using a regularized negative binomial regression model to simultaneously normalize data, stabilize variance, and identify variable features [13] [14] [16]. It directly models the UMI counts using a gamma-Poisson (negative binomial) distribution to account for the overdispersed nature of single-cell data. The core of the method involves calculating Pearson residuals for each gene in each cell:

[ r{gc} = \frac{y{gc} - \hat{\mu}{gc}}{\sqrt{\hat{\mu}{gc} + \hat{\alpha}{g} \hat{\mu}{gc}^2}} ]

Here, ( \hat{\mu}{gc} ) is the expected count based on the model, and ( \hat{\alpha}{g} ) is the estimated dispersion parameter for gene ( g ) [15] [16]. These residuals, which represent normalized expression values, are variance-stabilized—meaning they have approximately constant variance across the dynamic range of expression levels—making them suitable for downstream statistical analyses [13] [16]. A key advantage of this approach is its ability to account for the strong relationship between a gene's mean expression and its variance, which simpler methods like LogNormalize do not adequately address [15] [16].

Table 1: Core Mathematical Principles of Each Normalization Method

| Feature | LogNormalize | SCTransform |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Model | Heuristic scaling | Regularized Negative Binomial |

| Transformation | Log with pseudo-count | Pearson Residuals |

| Variance Stabilization | Limited | Explicitly modeled |

| Handling of Overdispersion | No | Yes |

| Technical Noise Modeling | Basic (library size only) | Comprehensive |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Analytical Benchmarks

When comparing the performance of these normalization methods, several key differences emerge. SCTransform consistently demonstrates superior performance in handling the mean-variance relationship inherent in single-cell data, effectively reducing technical artifacts while preserving biological heterogeneity [13] [15]. In practical benchmarks, SCTransform has been shown to reveal sharper biological distinctions between cell subtypes compared to the standard LogNormalize workflow [13]. For instance, analysis of PBMC datasets normalized with SCTransform typically shows clearer separation of CD8 T cell populations (naive, memory, effector) and additional developmental substructure in B cell clusters [13].

A significant advantage of SCTransform is its ability to mitigate the influence of sequencing depth variation on higher principal components. Whereas log-normalized data often shows persistent confounding effects of sequencing depth, sctransform substantially removes this technical variation, enabling the use of more principal components in downstream analyses that may capture subtle biological signals [13]. Furthermore, SCTransform automatically identifies a larger set of variable features (3,000 by default versus 2,000 for LogNormalize), with these additional features being less driven by technical differences and more likely to represent meaningful biological fluctuations [13].

Practical Implementation Considerations

Table 2: Practical Comparison for Pipeline Implementation

| Aspect | LogNormalize | SCTransform |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow Steps | NormalizeData(), FindVariableFeatures(), ScaleData() | Single SCTransform() command |

| Computation Time | Faster | Slower but more comprehensive |

| Data Output | Normalized counts in RNA@data |

Residuals in SCT@scale.data |

| Downstream Compatibility | Standard Seurat workflow | Compatible with most Seurat functions |

| Integration Performance | Requires separate integration steps | Excellent for integration workflows |

| Confounding Factor Regression | Manual during scaling | Built-in vars.to.regress parameter |

From an implementation perspective, SCTransform offers a more streamlined workflow by replacing three separate commands—NormalizeData(), FindVariableFeatures(), and ScaleData()—with a single function call [13] [14]. This consolidation reduces the potential for user error and ensures consistency in the preprocessing steps. Additionally, SCTransform includes a built-in capability to regress out unwanted sources of variation, such as mitochondrial percentage or cell cycle effects, during the normalization process itself [13] [14].

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: LogNormalize Workflow Implementation

The following step-by-step protocol details the implementation of the standard LogNormalize workflow within Seurat:

Quality Control and Filtering: Begin by removing low-quality cells based on QC metrics. Typical thresholds include filtering cells with unique gene counts (nFeature_RNA) outside the 200-2,500 range and mitochondrial percentage (percent.mt) below 5% [3].

Normalization: Apply the LogNormalize method with default parameters.

Variable Feature Identification: Select the top 2,000 most variable genes for downstream analysis.

Scaling and Confounding Factor Regression: Scale the data and optionally regress out unwanted sources of variation such as mitochondrial percentage.

Proceed to Downstream Analysis: The normalized and scaled data is now ready for dimensional reduction (PCA, UMAP) and clustering [3].

Protocol 2: SCTransform Workflow Implementation

The following protocol outlines the implementation of the SCTransform workflow, which replaces multiple steps of the conventional approach:

Quality Control and Filtering: Apply the same QC filtering criteria as in Protocol 1.

SCTransform Normalization: Perform normalization, variance stabilization, and variable feature identification in a single step, with optional regression of mitochondrial percentage.

Note: During normalization, SCTransform automatically accounts for sequencing depth. The

vars.to.regressparameter can be used to simultaneously remove other unwanted sources of variation [13] [14].Proceed to Downstream Analysis: The transformed data is stored in the "SCT" assay, which is automatically set as the default for subsequent analyses.

Protocol 3: Integration of Multiple Samples with SCTransform

For studies involving multiple samples or conditions, SCTransform provides a powerful approach for data integration:

Split Object by Sample: Divide the Seurat object by the sample identifier.

Independent SCTransform: Apply SCTransform independently to each sample.

Select Integration Features: Identify features that are variable across all datasets.

Prepare Data for Integration: Run the PrepSCTIntegration command.

Identify Anchors and Integrate: Find integration anchors and perform the actual integration.

Downstream Analysis: Run dimensional reduction and clustering on the integrated data.

Visualization of Methodologies and Workflows

Normalization Method Conceptual Diagram

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows of LogNormalize and SCTransform Methods. The diagram illustrates the sequential steps in each normalization approach, highlighting the more integrated nature of SCTransform.

Data Transformation Pathway

Diagram 2: Data Transformation Pathways. This diagram contrasts how each method processes challenging aspects of single-cell data, with SCTransform providing more comprehensive handling of technical artifacts.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Normalization

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Function | Application Context | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Framework | Seurat R Package | Overall analysis environment | Required for both normalization methods |

| Normalization Method | NormalizeData() | LogNormalize workflow | With method = "LogNormalize" |

| Advanced Normalization | SCTransform() | SCTransform workflow | Replaces multiple preprocessing steps |

| Integration Tool | IntegrateLayers() | Multi-sample integration | Works with SCT-normalized data [17] |

| Quality Control Metric | PercentageFeatureSet() | Mitochondrial content calculation | Pattern = "^MT-" for human data |

| Variable Feature Selection | FindVariableFeatures() | LogNormalize workflow | selection.method = "vst" |

| Dimensional Reduction | RunPCA(), RunUMAP() | Downstream analysis | Applies to both methods |

| Visualization | DimPlot(), FeaturePlot() | Result exploration | Group.by parameter for comparisons |

Based on current benchmarks and theoretical considerations, SCTransform generally outperforms LogNormalize in most scRNA-seq analysis scenarios, particularly for complex datasets with significant technical variation or when integrating multiple samples [13] [15] [14]. Its ability to simultaneously normalize data, stabilize variance, and identify variable features through a unified statistical framework represents a substantial advancement over the conventional approach.

However, the LogNormalize method remains valuable for certain applications, particularly for researchers in the early stages of pipeline development or when working with computationally constrained environments. The simpler method may also be preferred when performing direct comparisons with historical datasets processed with conventional normalization approaches.

For drug development professionals and researchers implementing single-cell RNA-seq pipelines, the following strategic recommendations are provided:

- Default to SCTransform for new analyses, particularly when working with multiple samples requiring integration or when analyzing cell populations with subtle biological differences.

- Leverage the Built-in Covariate Regression in SCTransform to simultaneously address confounding factors like mitochondrial percentage during the normalization process itself.

- Validate Key Findings with multiple normalization approaches when investigating critical biological questions, as methodological consistency strengthens conclusions.

- Consult Method-Specific Vignettes for specialized applications, particularly for complex experimental designs involving multiple conditions or time series.

The implementation of appropriate normalization strategies forms the foundation for all subsequent analyses in single-cell RNA sequencing workflows. By selecting the method best suited to their experimental design and research questions, scientists and drug development professionals can ensure that their conclusions are built upon a robust analytical foundation, ultimately leading to more reliable biological insights and therapeutic discoveries.

Identification of Highly Variable Features for Downstream Analysis

Within the framework of a single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis pipeline, the identification of Highly Variable Features (HVFs) constitutes a critical computational step that directly influences the resolution of all subsequent biological interpretations. This protocol details the implementation of HVF selection using the Seurat package, a cornerstone tool in modern single-cell genomics. The procedure enables researchers to isolate a subset of genes that exhibit high cell-to-cell variation, effectively filtering out technical noise and highlighting genes likely to be driving meaningful biological heterogeneity. For drug development professionals, this step is particularly vital as it focuses analysis on genes that may define distinct cell states or populations, potentially revealing novel therapeutic targets or biomarkers. The following sections provide a comprehensive guide to the theory, application, and quality control of HVF identification, formatted as standardized application notes for seamless integration into research workflows.

Biological and Technical Rationale

In any scRNA-seq dataset, the majority of genes are either uniformly expressed across cells or detected at levels indistinguishable from technical background noise. Highly variable genes (HVGs), in contrast, demonstrate significant variation in expression across the cell population. This variation can stem from several biologically relevant sources, including:

- Dynamic regulatory processes such as those governing cell differentiation, metabolic states, or cell cycle progression.

- Distinct cellular identities, where genes serve as markers for specific cell lineages or subtypes.

- Responses to external stimuli, including drug treatments or microenvironmental signals.

From a statistical perspective, selecting HVFs enhances the signal-to-noise ratio in downstream dimensional reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA). By focusing computational power on features that contain the most biologically relevant information, this step ensures that subsequent clustering and visualization are driven by true cellular heterogeneity rather than technical artifacts or uninformative genes [3] [4].

Workflow Integration and Prerequisites

The identification of HVFs occupies a specific position within the broader scRNA-seq analysis workflow. The following diagram illustrates the complete standard pre-processing workflow, with the HVF identification step highlighted in its critical context.

Prerequisite Steps: HVF identification requires properly normalized data. Prior to this step, researchers must have:

- Completed Quality Control (QC): Removed low-quality cells and potential doublets based on metrics like the number of detected genes per cell (

nFeature_RNA), total molecular counts per cell (nCount_RNA), and the percentage of mitochondrial reads (percent.mt) [3] [4] [18]. - Performed Data Normalization: Adjusted raw counts for systematic technical biases, most commonly using a global-scaling method like

LogNormalize, which normalizes by total cellular expression, multiplies by a scale factor (e.g., 10,000), and log-transforms the result [3].

Computational Methodologies

Seurat provides three distinct algorithms for HVF identification, each with unique statistical foundations and performance characteristics. The choice of method depends on the dataset size, biological question, and computational considerations.

The "vst" Method

The "vst" (variance stabilizing transformation) method is the most sophisticated and generally recommended approach. Its algorithm involves a multi-step procedure to account for the strong mean-variance relationship inherent in count-based sequencing data [19] [20].

The "mean.var.plot" (mvp) Method

The "mean.var.plot" method is a bin-based approach that controls for the expression mean when evaluating dispersion. It functions by:

- Calculating average expression and dispersion (variance-to-mean ratio) for each feature.

- Binning genes into a predefined number (

num.bin, default 20) of groups based on their average expression. - Calculating a z-score for dispersion within each bin to identify genes that are outliers relative to their expression-level peers [19] [20].

The "dispersion" (disp) Method

The "dispersion" method is the simplest and fastest of the three. It directly selects genes with the highest dispersion values, calculated as the variance-to-mean ratio. While computationally efficient, this method does not explicitly control for the relationship between mean expression and dispersion, which can lead to the selection of highly expressed but biologically uninteresting genes [19] [20].

Table 1: Comparison of HVF Selection Methods in Seurat

| Method | Key Function | Primary Advantage | Key Parameter(s) | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

vst |

FindVariableFeatures(selection.method = "vst") |

Directly models and removes the mean-variance relationship; most robust. | nfeatures, clip.max, loess.span |

Standard for most datasets; ideal for large or complex datasets. |

mean.var.plot (mvp) |

FindVariableFeatures(selection.method = "mvp") |

Controls for mean via binning and z-scoring; allows explicit cutoffs. | mean.cutoff, dispersion.cutoff |

When user-defined mean/dispersion cutoffs are desired. |

dispersion (disp) |

FindVariableFeatures(selection.method = "disp") |

Computational speed and simplicity. | nfeatures |

For rapid preliminary analysis on smaller datasets. |

Step-by-Step Protocol

This section provides a detailed, executable protocol for identifying HVFs in R using Seurat.

Code Implementation

The following code block demonstrates a complete workflow from normalization through HVF identification and visualization, using the "vst" method.

Parameter Optimization and Interpretation

The default parameters in FindVariableFeatures are well-suited for many datasets, but may require optimization for specific applications. The most critical parameters are:

nfeatures: Determines the number of top variable features to select for downstream analysis. The default is 2000. Increasing this number retains more features but can incorporate more noise; decreasing it focuses on the most prominent signals [3] [4].mean.cutoff&dispersion.cutoff: (Forselection.method = "mvp") Allows setting lower and upper bounds on the mean expression and dispersion of selected features. Useful for manually excluding very lowly expressed genes or extremely high outliers [19] [20].clip.max: (Forselection.method = "vst") Sets the maximum value for standardized feature values after variance stabilization. The default'auto'sets this to the square root of the number of cells [19].

Interpreting the Visualization: The plot generated by VariableFeaturePlot and LabelPoints is a mean-variance plot. Genes shown in red are selected as highly variable. The labeled top genes often include known cell-type-specific markers (e.g., CD3D for T cells, MS4A1 for B cells in PBMC data), providing a quick sanity check for the biological validity of the selection [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for HVF Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Seurat Package | Primary software environment for single-cell analysis in R. | Provides the FindVariableFeatures() function. Critical for the entire workflow [3]. |

| Log-Normalized Data | Normalized expression matrix. Required input for HVF detection. | Generated by NormalizeData(). Corrects for library size and transforms data [3] [4]. |

| Variable Feature Plot | Diagnostic visualization. | Verifies HVG selection. Top genes can be labeled for biological validation [3]. |

| Alternative Workflow: SCTransform | A comprehensive normalization and variance stabilization method. | Can replace NormalizeData, FindVariableFeatures, and ScaleData. Uses regularized negative binomial regression [3] [4]. |

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

A successful HVF selection is paramount for the entire downstream analysis. Common issues and their solutions include:

- Too Few/Too Many Variable Features: Adjust the

nfeaturesparameter. If the resulting list is consistently small, inspect the mean-variance plot for unusual distributions and consider relaxing themean.cutoffordispersion.cutoffin the "mvp" method. - Lack of Known Markers in HVF List: If well-established cell type markers for your system are not being selected, it may indicate overly stringent filtering during QC or normalization issues. Revisit the QC metrics and violin plots to ensure a valid cell population is being analyzed.

- Integration Across Batches: For datasets combining multiple samples or conditions, the standard HVF selection performed on a merged object can be confounded by technical batch effects. In such cases, use the

SelectIntegrationFeaturesfunction as part of Seurat's integration workflow, which identifies features that are variable across multiple datasets to improve integration and conserve biological signal while minimizing technical artifacts [17].

Downstream Applications

The set of highly variable features serves as the direct input for several subsequent analytical steps:

- Data Scaling: The

ScaleDatafunction centers and scales the expression values of the HVFs, giving equal weight to all selected genes in downstream dimensionality reduction [3] [4]. - Linear Dimensional Reduction: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is performed exclusively on the scaled HVF data. These features encapsulate the majority of the biological signal, allowing PCA to effectively reduce data dimensionality while preserving meaningful heterogeneity [3] [4].

- Clustering and Visualization: The principal components generated from HVFs form the basis for graph-based clustering (

FindNeighbors,FindClusters) and non-linear dimensionality reduction for visualization (RunUMAP,RunTSNE). The quality of these results is therefore fundamentally tied to the initial identification of HVFs [3].

The precise identification of Highly Variable Features is a non-negotiable, foundational step in a robust single-cell RNA-seq analysis pipeline using Seurat. The protocols outlined herein provide researchers and drug developers with a standardized framework for executing this task, complete with methodological comparisons, practical code, and quality control measures. By carefully selecting genes that drive cellular heterogeneity, this process ensures that downstream analyses—from population clustering to biomarker discovery—are conducted on a solid foundation of high-confidence biological signal, ultimately leading to more reliable and interpretable scientific conclusions.

Dimensionality Reduction with PCA and Initial Cell Clustering

In the broader context of implementing a single-cell RNA-seq analysis pipeline with Seurat, dimensionality reduction represents a critical computational step that bridges the gap between normalized gene expression data and biological interpretation. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) generates high-dimensional datasets where each cell is represented by expression levels of thousands of genes, immediately presenting the challenge known as the "curse of dimensionality" [21]. Not all genes are informative for distinguishing cell identities, and the data contains substantial technical noise and redundancy that can obscure biological signals.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as a fundamental linear dimensionality reduction technique that creates a new set of uncorrelated variables called principal components (PCs) through an orthogonal transformation of the original dataset [21]. These PCs are linear combinations of the original features (genes) ranked by the amount of variance they explain in the data. By focusing on the top principal components, researchers can dramatically reduce data complexity while retaining the most biologically relevant information. This reduction is essential for downstream analyses, including clustering and trajectory inference, as it mitigates noise and computational burden while highlighting meaningful patterns of cellular heterogeneity.

The initial cell clustering that follows PCA leverages these reduced dimensions to group cells based on similar gene expression profiles, effectively partitioning the cellular landscape into putative cell types or states. Within the Seurat ecosystem, this integrated process of dimensionality reduction and clustering forms the backbone of exploratory scRNA-seq analysis, enabling researchers to move from raw expression matrices to biologically meaningful categorizations of cellular diversity.

Theoretical Foundation

The Mathematics of PCA

Principal Component Analysis operates on the fundamental principle of identifying directions of maximum variance in high-dimensional data. Mathematically, given a normalized and scaled gene expression matrix X with dimensions m×n (where m represents cells and n represents genes), PCA seeks to find a set of orthogonal vectors (principal components) that capture the dominant patterns of variation. The first principal component is defined as the linear combination of genes that maximizes the variance:

PC₁ = w₁₁Gene₁ + w₁₂Gene₂ + ... + w₁ₙGeneₙ

where the weights w₁ = (w₁₁, w₁₂, ..., w₁ₙ) are chosen to maximize Var(PC₁) subject to w₁ᵀw₁ = 1. Subsequent components PC₂, PC₃, etc., are defined similarly with the additional constraint that each must be orthogonal to (uncorrelated with) all previous components.

The principal components correspond to the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix of X, and the eigenvalues represent the amount of variance explained by each component. In biological terms, the early PCs that capture the most variance typically represent major sources of cellular heterogeneity, such as distinctions between major cell types, while later PCs with less variance may represent more subtle biological differences or technical noise.

Alternative Dimensionality Reduction Methods

While PCA remains the standard initial dimensionality reduction method for scRNA-seq workflows, several non-linear techniques have gained popularity for visualization and specific applications:

t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE): A non-linear graph-based technique that projects high-dimensional data onto 2D or 3D components by defining a Gaussian probability distribution based on high-dimensional Euclidean distances between data points, then recreating the probability distribution in low-dimensional space using Student t-distribution [21]. An independent comparison of 10 different dimensionality reduction methods proposed t-SNE as yielding the best overall performance [21].

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP): Another graph-based non-linear dimensionality reduction technique that constructs a high-dimensional graph representation of the dataset and optimizes the low-dimensional graph representation to be structurally as similar as possible [21]. UMAP has shown the highest stability and best separation of original cell populations in comparative studies [21].

Boosting Autoencoder (BAE): A recently developed approach that combines unsupervised deep learning for dimensionality reduction with boosting for formalizing structural assumptions [22]. This method selects small sets of genes that explain latent dimensions, providing enhanced interpretability by linking specific patterns in the low-dimensional space to individual explanatory genes.

Table 1: Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Methods for scRNA-seq Data

| Method | Type | Key Features | Best Use Cases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Linear | Computationally efficient, highly interpretable, preserves global structure | Initial dimensionality reduction, large datasets | Limited for capturing complex non-linear relationships |

| t-SNE | Non-linear | Preserves local structure, creates visually distinct clusters | Visualization of cell subpopulations | Computational intensive for large datasets, stochastic results |

| UMAP | Non-linear | Preserves both local and global structure, faster than t-SNE | Visualization, trajectory analysis | Parameter sensitivity, less interpretable than PCA |

| BAE | Non-linear | Incorporates structural assumptions, identifies explanatory gene sets | Pattern discovery in complex systems, temporal data | Computational complexity, newer less-established method |

Experimental Protocol

Pre-processing for Dimensionality Reduction

Before performing dimensionality reduction, proper data pre-processing is essential to ensure meaningful results. The Seurat-guided clustering tutorial outlines this standard workflow [3] [23]:

Quality Control and Cell Filtering: Filter out low-quality cells based on QC metrics including the number of detected genes per cell (nFeatureRNA), total UMI counts per cell (nCountRNA), and percentage of mitochondrial reads (percent.mt). Typical thresholds include removing cells with fewer than 200 detected genes, more than 2,500 detected genes (potential doublets), and more than 5% mitochondrial counts [3].

Normalization: Normalize the feature expression measurements for each cell using the "LogNormalize" method, which normalizes by total expression, multiplies by a scale factor (10,000 by default), and log-transforms the result. The normalized values are stored in

pbmc[["RNA"]]$datain Seurat v5 [3].Feature Selection: Identify highly variable features (genes) that exhibit high cell-to-cell variation using the

FindVariableFeatures()function with the "vst" selection method. By default, 2,000 features are selected for downstream analysis [3].Scaling: Scale the data using the

ScaleData()function to shift the expression of each gene so the mean expression across cells is 0 and scale the expression so the variance is 1. This gives equal weight in downstream analyses, preventing highly-expressed genes from dominating [3]. The results are stored inpbmc[["RNA"]]$scale.data.

PCA Implementation

The core protocol for performing PCA in Seurat consists of the following steps [3]:

Execute PCA: Run PCA on the scaled data using the

RunPCA()function. By default, only the previously identified variable features are used as input.Determine Significant PCs: Identify the number of significant principal components to retain for downstream analyses. While no universal method exists, the following approaches are commonly used:

- Elbow Plot Visualization: Plot the standard deviations of the principal components using

ElbowPlot()to identify an "elbow" point where the explained variance starts to plateau. - Statistical Methods: Use more quantitative approaches such as the JackStraw procedure, though this is computationally intensive.

- Heuristic Thresholds: Commonly, the top 10-50 PCs are selected, capturing the majority of biological variation while excluding technical noise [21].

- Elbow Plot Visualization: Plot the standard deviations of the principal components using

PC Visualization: Explore the PCA results using several visualization techniques:

VizDimLoadings(): Visualize the genes that drive variation in selected principal components.DimPlot(): Plot cells in reduced PCA space, colored by experimental conditions or sample origins.DimHeatmap(): Explore the primary sources of heterogeneity in the dataset by plotting the genes and cells with the strongest positive and negative loadings across multiple PCs.

Initial Cell Clustering

Following dimensionality reduction, cluster cells based on their expression profiles in the reduced PCA space:

Construct Nearest Neighbor Graph: Build a shared nearest neighbor (SNN) graph based on the Euclidean distance in PCA space using the

FindNeighbors()function, specifying the same number of dimensions as selected in the PCA step.Cluster Cells: Perform graph-based clustering using the Louvain algorithm (default) or other methods via the

FindClusters()function. The resolution parameter controls the granularity of clustering, with higher values leading to more clusters.Non-linear Visualization: Project the clustering results into 2D space using non-linear dimensionality reduction methods like UMAP or t-SNE for visualization purposes.

Parameter Optimization

Table 2: Key Parameters for Dimensionality Reduction and Initial Clustering

| Step | Parameter | Default Value | Recommended Range | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Selection | nfeatures | 2000 | 1000-3000 | Number of highly variable genes used as PCA input |

| PCA | npcs | 50 | 10-50 | Maximum number of PCs to compute |

| PC Selection | dims | 1:10 | 1:10 to 1:50 | Number of PCs used for downstream clustering |

| Clustering | resolution | 0.8 | 0.4-1.2 | Higher values increase cluster number |

| UMAP | n.neighbors | 30 | 5-50 | Balances local vs. global structure |

Visualization

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process of dimensionality reduction and initial cell clustering within the broader scRNA-seq analysis pipeline:

Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering

| Tool/Software | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat | Comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis | Primary tool for PCA and clustering in R | PCA implementation, graph-based clustering, visualization |

| Scanpy | Scalable scRNA-seq analysis | Python alternative to Seurat | PCA, clustering, visualization, integration with machine learning libraries |

| Harmony | Batch effect correction | Integration of multiple datasets | Projects cells into shared embedding correcting for dataset-specific conditions |

| scran | Scalable scRNA-seq analysis | Low-level processing and normalization | Computes highly variable genes, performs PCA |

| SCTransform | Normalization workflow | Alternative to standard log normalization | Replaces NormalizeData, FindVariableFeatures, ScaleData steps |

| SingleR | Cell type annotation | Automated cell type identification | Uses reference datasets to annotate clusters |

| scType | Cell type identification | Automated cell typing | Uses comprehensive cell marker database for annotation |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Challenges and Solutions

Insufficient Cluster Separation: If clusters appear poorly separated in visualization, consider increasing the number of PCs used (

dimsparameter inFindNeighbors()), adjusting the clustering resolution, or re-evaluating the number of highly variable genes.Over-clustering or Under-clustering: The resolution parameter in

FindClusters()significantly impacts cluster number. Test multiple resolutions (typically 0.4-2.0) and evaluate biological plausibility using known marker genes.Batch Effects: When integrating multiple samples or datasets, batch effects can confound dimensionality reduction. Consider using integration methods such as Harmony, Seurat's CCA integration [17], or the SCTransform normalization workflow with variance stabilization.

Computational Resources: For large datasets (>50,000 cells), PCA can become computationally intensive. Utilize Seurat's support for sparse matrices, consider approximate PCA methods, or utilize tools like Scanorama for extremely large datasets.

Validation and Interpretation

Validating clustering results is essential for biological interpretation:

Differential Expression Analysis: Identify cluster-specific marker genes using

FindAllMarkers()to validate that clusters represent distinct cell populations with unique transcriptional profiles.Annotation with Known Markers: Compare cluster expression profiles with established cell-type markers from literature or databases to assign biological identities.

Conserved Marker Identification: When analyzing multiple conditions, use

FindConservedMarkers()to identify canonical cell type marker genes that are conserved across conditions [17].Cluster Stability: Assess cluster robustness through sub-sampling approaches or by comparing results across different dimensionality reduction methods.

Dimensionality reduction with PCA and initial cell clustering represents a foundational analytical phase in single-cell RNA sequencing analysis that transforms high-dimensional gene expression data into biologically interpretable patterns of cellular heterogeneity. The methodical application of this workflow within the Seurat framework enables researchers to identify distinct cell populations, uncover novel cell states, and form initial hypotheses about cellular function and relationships.

The robustness of this approach lies in its mathematical foundation, which systematically distills the most biologically relevant information from complex transcriptional profiles while mitigating technical noise. When properly implemented with appropriate quality controls and parameter optimization, this analytical sequence serves as a critical gateway to more specialized downstream analyses, including differential expression testing, trajectory inference, and cell-cell communication analysis.

As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, producing increasingly large and complex datasets, the principles of dimensionality reduction and clustering remain essential for extracting meaningful biological insights from the high-dimensional landscape of cellular transcriptomes.

Visualization with UMAP/t-SNE and Exploratory Data Analysis

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) reveals cellular heterogeneity by profiling transcriptomes of individual cells, generating high-dimensional data where each of the thousands of genes represents a dimension [24]. Analyzing this data requires dimensionality reduction techniques that transform these high-dimensional measurements into lower-dimensional spaces while preserving meaningful biological structure. This process is fundamental for effective visualization and identifying patterns such as cell subpopulations, developmental trajectories, and disease-associated states [25] [26].

Two nonlinear dimensionality reduction methods have become standard in scRNA-seq analysis pipelines: t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) [24]. These techniques enable researchers to project high-dimensional single-cell data into two or three dimensions for visualization, facilitating the exploration of complex cellular relationships. Within the Seurat framework, these methods operate downstream of quality control, normalization, and feature selection steps, providing crucial insights into dataset structure that guide subsequent biological interpretation [3] [17].

Table 1: Key Dimensionality Reduction Methods for scRNA-seq Data

| Method | Type | Key Characteristics | Optimization Goal | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Linear | Maximizes variance, orthogonal components | Global covariance structure | Initial feature reduction, noise reduction |

| t-SNE | Nonlinear | Preserves local neighborhoods, exaggerates cluster separation | Local probability distributions | Cluster visualization emphasizing separation |

| UMAP | Nonlinear | Preserves local and more global structure | Topological representation | Cluster visualization with preservation of continuum relationships |

Theoretical Foundations of t-SNE and UMAP

The Evolution from SNE to t-SNE to UMAP

The development of modern dimensionality reduction techniques represents an evolutionary progression from Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (SNE) to t-SNE and finally to UMAP [25]. SNE, the original algorithm, computed probabilities that reflect similarities between data points in both high and low-dimensional spaces using Gaussian neighborhoods [25]. It aimed to minimize the mismatch between these probability distributions using Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence as a cost function. However, SNE suffered from optimization difficulties and the "crowding problem"—where moderately distant data points became overcrowded in the lower-dimensional representation [25].

t-SNE introduced two critical modifications to address SNE's limitations: symmetrization of the probability distribution and the use of the Student t-Distribution with one degree of freedom for the low-dimensional probabilities [25]. The symmetric approach simplified the gradient computation, significantly improving optimization performance. Meanwhile, the heavier-tailed t-distribution alleviated the crowding problem by allowing moderate distances to be modeled more effectively in the low-dimensional space [25]. These innovations made t-SNE the state-of-the-art method for dimensional reduction visualization for many years.

UMAP builds upon the foundation of t-SNE with theoretical underpinnings in manifold theory and topological data analysis [25]. While sharing conceptual similarities with t-SNE, UMAP employs a different theoretical framework that enables it to preserve more of the global data structure while still capturing local neighborhoods [25] [24]. Algorithmically, UMAP constructs a weighted k-neighbor graph in high dimensions and optimizes the low-dimensional embedding to preserve this graph's topological structure [24].

Mathematical Underpinnings and Comparative Mechanics

The t-SNE algorithm operates through a specific probabilistic framework. First, it computes pairwise similarities between high-dimensional data points, representing them as conditional probabilities ( p{j|i} ) that point ( xi ) would pick point ( x_j ) as its neighbor:

( p{j|i} = \frac{\exp(-||xi - xj||^2 / 2\sigmai^2)}{\sum{k \neq i} \exp(-||xi - xk||^2 / 2\sigmai^2)} )

where ( \sigmai ) is determined through binary search to achieve a user-specified perplexity value, which represents the effective number of local neighbors [25]. t-SNE then symmetrizes these probabilities to create a joint probability distribution: ( p{ij} = \frac{p{j|i} + p{i|j}}{2n} ).

In the low-dimensional space, t-SNE employs a Student t-distribution with one degree of freedom to compute similarities:

( q{ij} = \frac{(1 + ||yi - yj||^2)^{-1}}{\sum{k \neq l} (1 + ||yk - yl||^2)^{-1}} )

The algorithm minimizes the KL divergence between the two probability distributions:

( C = KL(P || Q) = \sumi \sumj p{ij} \log \frac{p{ij}}{q_{ij}} )

This cost function heavily penalizes cases where nearby points in high-dimensional space are mapped far apart in the low-dimensional representation, which causes t-SNE to prioritize preserving local structure over global relationships [25].

UMAP uses a different theoretical approach, defining similarities in high-dimensional space using an exponential kernel:

( p{ij} = \exp(-||xi - xj||^2 / \sigmai) )

where the bandwidth ( \sigma_i ) is determined based on the distance to the k-th nearest neighbor, with k being a user-specified parameter [24]. In the low-dimensional space, UMAP uses a different family of functions:

( q{ij} = (1 + a ||yi - y_j||^{2b})^{-1} )

where a and b are hyperparameters. UMAP then minimizes the cross-entropy between the two fuzzy topological representations:

( C{UMAP} = \sum{i,j} [p{ij} \log \frac{p{ij}}{q{ij}} + (1 - p{ij}) \log \frac{1 - p{ij}}{1 - q{ij}}] )

This symmetric cost function allows UMAP to better preserve both local and global structure compared to t-SNE [25] [24].

Practical Implementation in Seurat Framework

Preprocessing for Dimensionality Reduction

Successful UMAP/t-SNE visualization in Seurat requires meticulous data preprocessing. The standard workflow begins with quality control to remove low-quality cells that could distort the dimensional reduction. Key QC metrics include the number of unique genes detected per cell (nFeatureRNA), total molecules detected per cell (nCountRNA), and the percentage of mitochondrial reads (percent.mt) [3] [18]. Typically, we filter out cells with either anomalously high or low gene counts, and those with elevated mitochondrial percentage (often >5-10% for PBMCs), indicating potential cell stress or apoptosis [3] [27].

Following quality control, data normalization ensures technical variations don't dominate biological signals. Seurat's default approach uses global-scaling normalization ("LogNormalize") that normalizes each cell's feature expression measurements by total expression, multiplies by a scale factor (10,000), and log-transforms the result [3]. The normalized values are stored in pbmc[["RNA"]]$data. Alternatively, the SCTransform() function provides a more advanced normalization approach that can simultaneously account for technical confounding factors [3].

The next critical step is identification of highly variable features—genes that exhibit high cell-to-cell variation, which typically represent biologically meaningful signals rather than technical noise. Seurat's FindVariableFeatures() function selects these features using a variance-stabilizing transformation, typically returning 2,000 genes for downstream analysis [3]. Finally, scaling centers and scales the data so that highly-expressed genes don't dominate the dimensional reduction. The ScaleData() function shifts expression so the mean is 0 and scales variance to 1 across cells, with results stored in pbmc[["RNA"]]$scale.data [3].

Executing UMAP and t-SNE in Seurat

After preprocessing and principal component analysis (PCA), Seurat provides streamlined functions for both UMAP and t-SNE visualization. The standard workflow applies these methods to the principal components that capture the most significant biological variation, rather than directly to the thousands of genes in the original data [3] [17].

For UMAP, the RunUMAP() function generates the embedding:

For t-SNE, the analogous RunTSNE() function creates the embedding:

Both methods typically use the first 20-30 principal components as input, as these capture the most biologically relevant variance while filtering out noise [3] [17]. The resulting embeddings can be colored by cluster identity, experimental condition, expression of specific genes, or other metadata to extract biological insights.

Table 2: Key Parameters for Dimensionality Reduction in Seurat

| Parameter | t-SNE | UMAP | Effect on Output | Recommended Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perplexity | ~5-50 [25] | N/A | Balances local/global structure attention | 30 (default) |

| n.neighbors | N/A | ~5-50 [24] | Controls local connectivity vs global structure | 30 (default) |

| Dims | 1:30 [17] | 1:30 [17] | Number of PCs used as input | 10-50 (dataset dependent) |

| Learning Rate | 200 (default) | 1 (default) | Optimization step size | Typically default values |

| Minimum Distance | N/A | 0.3 (default) | Controls cluster compactness | 0.1-0.5 (cluster separation) |

Advanced Applications and Integration Approaches

Multi-Sample Integration with UMAP/t-SNE

When analyzing multiple scRNA-seq datasets—whether from different batches, donors, or experimental conditions—directly applying UMAP or t-SNE to concatenated data can yield misleading visualizations where technical effects dominate biological signals [17]. Seurat's integration workflow addresses this by identifying "anchors" between datasets—pairs of cells from different datasets that are in a matched biological state [17].

The integration process begins by splitting the RNA assay into different layers for each condition:

Next, the IntegrateLayers() function identifies integration anchors and creates a combined dimensional reduction that captures shared biological variance:

After integration, standard UMAP or t-SNE can be applied to the integrated space, yielding visualizations where cells cluster primarily by biological identity rather than technical origin [17]. This enables direct comparison of similar cell states across conditions, facilitating downstream analyses like differential expression and conserved marker identification.

CCP-Assisted Dimensionality Reduction

Recent methodological advances include Correlated Clustering and Projection (CCP), a data-domain approach that serves as an effective preprocessing step for UMAP and t-SNE [24]. CCP operates by partitioning genes into clusters based on their correlations and projecting genes within each cluster into "super-genes" that represent accumulated gene-gene correlations [24].

The CCP-assisted UMAP/t-SNE workflow involves:

- Gene clustering: Partitioning genes into N clusters using k-means or k-medoids based on correlation measures

- Gene projection: Projecting each gene cluster into a single super-gene descriptor using the Flexibility Rigidity Index (FRI)

- Visualization: Applying standard UMAP or t-SNE to the super-gene representation

This approach has demonstrated significant improvements over standard methods, with reported enhancements of 22% in Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), 14% in Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), and 15% in Element-Centric Measure (ECM) for UMAP visualization [24]. Similarly, CCP improves t-SNE by 11% in ARI, 9% in NMI, and 8% in ECM [24]. CCP is particularly valuable for handling low-variance genes that might otherwise be discarded, instead grouping them into a consolidated descriptor that preserves subtle biological signals.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Analysis

| Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat [3] | R Package | Comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis toolkit | Primary framework for data processing, normalization, clustering, and visualization |

| SingleR [18] | R Package | Automated cell type annotation | Reference-based cell type identification using reference transcriptomic datasets |

| celldex [18] | R Package | Reference dataset collection | Provides curated reference datasets for cell type annotation with SingleR |

| scDblFinder [28] | R Package | Doublet detection | Identification and removal of multiplets from single-cell data |

| SoupX [18] [27] | R Package | Ambient RNA correction | Removal of background contamination from free-floating RNA in solution |

| 10X Genomics Cell Ranger [27] | Computational Pipeline | Raw data processing | Alignment, filtering, barcode counting, and initial feature-barcode matrix generation |

| Loupe Browser [27] | Visualization Software | Interactive data exploration | Visualization and preliminary analysis of 10X Genomics single-cell data |

| SCTransform [3] | Normalization Method | Advanced normalization | Improved normalization accounting for technical confounding factors |

Advanced Analytical Techniques: Data Integration, Marker Identification, and Spatial Transcriptomics

Integrating Multiple Datasets with CCA to Overcome Batch Effects

The integration of multiple single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) datasets is a standard step in modern bioinformatics pipelines, essential for unlocking new biological insights that cannot be obtained from individual datasets alone. Pooling datasets from different studies enables robust cross-condition comparisons, population-level analyses, and the revelation of evolutionary relationships between cell types [29]. However, the joint analysis of two or more single-cell datasets presents unique challenges, primarily due to the presence of batch effects—systematic technical variations arising from differences in cell isolation protocols, library preparation technologies, sequencing platforms, or handling personnel [30] [31]. These batch effects are inevitable in multi-dataset studies and can confound true biological variation, leading to misinterpretation of results if not properly addressed [31] [32].

Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) has emerged as a powerful computational strategy for batch-effect correction, particularly within the widely-used Seurat toolkit. Unlike approaches that aggressively remove all variation between datasets, CCA identifies shared correlation structures across datasets to align them in a common subspace, effectively removing technical artifacts while preserving meaningful biological heterogeneity [33] [32]. This approach is particularly valuable for large-scale "atlas" projects that aim to combine diverse public datasets with substantial technical and biological variation, including samples from multiple organs, developmental stages, and experimental systems [29]. The following sections provide a detailed protocol for implementing CCA-based integration, benchmark its performance against alternative methods, and outline essential reagents for successful implementation.

Comparative Performance of scRNA-seq Batch Correction Methods

Independent benchmarking studies have comprehensively evaluated numerous batch-effect correction methods across diverse integration scenarios. These benchmarks typically assess methods based on both batch correction efficacy (how well technical variations are removed) and biological preservation (how well true cell-type distinctions are maintained). The table below summarizes key findings from a large-scale benchmark of 14 methods across ten datasets:

Table 1: Benchmarking metrics for popular batch-effect correction methods

| Method | Basis of Approach | Batch Correction Efficacy | Biological Preservation | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat (CCA) | Canonical Correlation Analysis + Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) anchors | High | High | General purpose; datasets with shared cell types [32] |

| Harmony | Iterative clustering with PCA dimensionality reduction | High | High | First choice due to fast runtime; multiple batches [34] [32] |

| LIGER | Integrative Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) | Medium-High | High | When biological differences between batches are expected [32] |

| scVI | Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | High | High | Very large datasets; atlas-level integration [29] [34] |

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes framework | Medium | Low-Medium | Simple batch adjustments; may not handle scRNA-seq sparsity well [35] [32] |

| fastMNN | Mutual Nearest Neighbors in PCA space | High | Medium-High | Rapid analysis with minimal parameter tuning [32] |

A more recent evaluation of method performance in complex integration scenarios—such as cross-species, organoid-tissue, and single-cell/single-nuclei RNA-seq integrations—reveals that while CCA-based methods generally perform well, advanced deep learning approaches like scVI and scANVI may be preferable for extremely challenging integration tasks with substantial batch effects [29] [34]. However, for most standard applications, CCA-based integration in Seurat provides an excellent balance of performance, interpretability, and computational efficiency.

Table 2: Quantitative performance scores across integration scenarios (higher values indicate better performance)

| Method | Batch Correction (iLISI/LISI) | Cell Type Conservation (NMI/ARI) | Runtime Efficiency | Scalability to Large Datasets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat (CCA) | 0.82 | 0.88 | Medium | High [32] |

| Harmony | 0.85 | 0.86 | High | High [32] |

| scVI | 0.80 | 0.85 | Medium (GPU accelerated) | Very High [29] [34] |

| LIGER | 0.78 | 0.89 | Low-Medium | Medium [32] |

Detailed Protocol: CCA-Based Integration Using Seurat

Preparation of Individual Seurat Objects

The initial phase involves processing each dataset independently to ensure proper normalization and identification of variable features prior to integration:

Step 1: Load and Initialize Seurat Objects

Step 2: Quality Control and Filtering Apply standard QC metrics to remove low-quality cells and potential doublets:

Step 3: Normalization and Variable Feature Selection Process each dataset independently using standard Seurat workflow:

Integration Anchors Identification and Dataset Integration

The core integration process involves identifying correspondence points (anchors) between datasets and using these to correct batch effects:

Step 4: Select Features and Find Integration Anchors Identify features consistently variable across datasets and use them to find correspondence anchors:

Step 5: Integrate Datasets Use the identified anchors to create a batch-corrected integrated dataset:

Integrated Analysis and Downstream Applications

After integration, perform a unified analysis on the combined dataset and conduct comparative analyses across conditions:

Step 6: Integrated Analysis Workflow

Step 7: Identify Conserved Cell Type Markers Switch back to the original RNA assay to find markers conserved across conditions:

Step 8: Differential Expression Across Conditions Compare expression profiles between conditions within specific cell types:

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for scRNA-seq integration

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Framework | Seurat v4+ | Comprehensive toolkit for single-cell analysis, including CCA integration | R package [30] |

| Alternative Methods | Harmony, scVI, LIGER | Alternative integration approaches for specific use cases | R/Python packages [34] [32] |

| Quality Control | scDblFinder, SoupX | Doublet detection and ambient RNA correction | R packages [34] |

| Normalization | SCTransform, LogNormalize | Data normalization and variance stabilization | Seurat functions [30] |

| Visualization | UMAP, t-SNE | Dimensionality reduction for data visualization | Seurat/Scanpy [32] |

| Benchmarking | scIB | Comprehensive integration benchmarking metrics | Python package [34] |