A Comprehensive Guide to Differential Gene Expression Analysis with DESeq2: From Raw Counts to Biological Insights

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for performing differential gene expression analysis using DESeq2.

A Comprehensive Guide to Differential Gene Expression Analysis with DESeq2: From Raw Counts to Biological Insights

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for performing differential gene expression analysis using DESeq2. Covering everything from foundational concepts and statistical methodologies to practical implementation, troubleshooting, and validation techniques, this resource addresses critical challenges in RNA-seq data analysis. Readers will learn to design robust experiments, execute the DESeq2 workflow, interpret results accurately, and apply these findings to advance biomedical research and therapeutic discovery.

Understanding DESeq2: Statistical Foundations and Experimental Design Principles

DESeq2 is a widely used R/Bioconductor package designed for differential expression analysis of high-throughput sequencing count data, such as RNA-seq [1]. A fundamental task in the analysis of this data is the detection of differentially expressed genes, which involves identifying genes that show systematic changes in expression levels across different experimental conditions (e.g., treated vs. control) [2]. DESeq2 addresses this by employing statistical inference based on a negative binomial generalized linear model [1]. The methodology incorporates data-driven prior distributions to stabilize the estimates of dispersion and logarithmic fold changes, enabling a more quantitative analysis focused on the strength, and not merely the presence, of differential expression [2] [1]. Since its original publication in 2014, DESeq2 has become a cornerstone tool in genomic studies, with its approach also being applicable to other comparative sequencing assays like ChIP-Seq, HiC, and mass spectrometry [2] [3].

The Negative Binomial Model: Rationale and Formulation

Why the Negative Binomial Distribution?

RNA sequencing data presents specific statistical challenges that make standard parametric models like the Poisson distribution unsuitable. The primary limitation of the Poisson model is its assumption that the mean equals the variance in the data [4]. In real RNA-seq data, the variance between biological replicates is typically greater than the mean, a phenomenon known as overdispersion [5] [1]. This overdispersion arises from both biological variability (true differences in gene expression between replicates of the same group) and technical variability inherent to the sequencing process [5].

The negative binomial (NB) distribution, also referred to as the gamma-Poisson distribution, generalizes the Poisson distribution by introducing an additional dispersion parameter (α) that accounts for the extra variance [6] [1]. This makes it a robust and flexible model for RNA-seq count data, as it can accurately capture the mean-variance relationship observed in these experiments [4].

Mathematical Model Specification

DESeq2 models raw read counts, K~ij~, for gene i and sample j as following a negative binomial distribution with a mean μ~ij~ and a gene-specific dispersion parameter α~i~ [1]. The distribution is defined such that the variance, Var(K~ij~), is a function of both the mean and the dispersion:

Var(K~ij~) = μ~ij~ + α~i~ * μ~ij~^2^ [7] [1]

The mean μ~ij~ is itself modeled as the product of a quantity q~ij~ (proportional to the true concentration of cDNA fragments from the gene in the sample) and a size factor s~ij~ (a normalization factor accounting for differences in sequencing depth between samples) [1]:

μ~ij~ = s~ij~ * q~ij~

To test for differential expression, DESeq2 uses a generalized linear model (GLM) with a logarithmic link function [1]. The linear model for the quantity q~ij~ is expressed as:

log~2~(q~ij~) = ∑~r~ *x~jr~ β~ir~*

Here, the coefficients β~ir~ are the log2 fold changes for the gene for the different explanatory variables in the design formula. The use of GLMs provides the flexibility to analyze complex experimental designs beyond simple two-group comparisons [1].

The DESeq2 Analytical Workflow

The differential expression analysis in DESeq2 is a multi-step process that is efficiently executed with a single call to the DESeq() function [7] [5]. The workflow can be broken down into four key stages, which are automatically performed in sequence.

Step 1: Estimation of Size Factors (Normalization)

The first step accounts for differences in library size (sequencing depth) between samples. DESeq2 uses the median-of-ratios method to calculate a size factor for each sample [6] [1]. This method:

- Calculates the geometric mean for each gene across all samples.

- Computes the ratio of each gene's count in a sample to its geometric mean.

- The size factor for a sample is the median of these ratios for all genes [6].

These size factors are then used to normalize the raw counts, effectively bringing all samples to a common scale for comparison. The DESeq2 model internally corrects for library size, which is why it requires un-normalized, raw count data as input [2] [3] [8].

Step 2: Estimation of Gene-wise Dispersion

The dispersion parameter (α) is critical as it quantifies the variability of a gene's expression around its mean. For each gene, DESeq2 calculates a gene-wise dispersion estimate using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) [7] [5]. This initial estimate, however, is unreliable when based on only a few replicates, as is common in RNA-seq experiments. Genes with low counts tend to have high and highly variable dispersion estimates, while high-count genes have more stable estimates [7] [5].

Step 3: Fitting a Dispersion Trend Curve and Shrinkage

To overcome the noise in gene-wise estimates, DESeq2 employs an empirical Bayes shrinkage procedure [1]. The method assumes that genes with similar average expression strength tend to have similar dispersion. A smooth curve is fitted to the gene-wise dispersion estimates as a function of the mean normalized counts (the red line in the diagram below) [7] [1]. This curve represents a prior mean for the dispersion.

The final dispersion value for each gene is determined by shrinking the gene-wise estimate towards the value predicted by the curve [7]. The strength of shrinkage depends on:

- The closeness of the gene-wise estimate to the curve.

- The number of replicates (more replicates lead to less shrinkage) [1].

This shrinkage improves the stability and reliability of dispersion estimates, which is crucial for accurate statistical testing and helps reduce false positives [7].

Step 4: Model Fitting and Hypothesis Testing

In the final step, DESeq2 fits the negative binomial GLM to the normalized count data using the shrunken dispersion estimates. To test for differential expression, it typically uses the Wald test, which compares the estimated log2 fold change for a gene to its standard error [5]. A significant p-value indicates that the observed change in gene expression between conditions is greater than what would be expected by chance alone. These p-values are then adjusted for multiple testing using procedures like the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate (FDR) and provide an adjusted p-value (padj) [4].

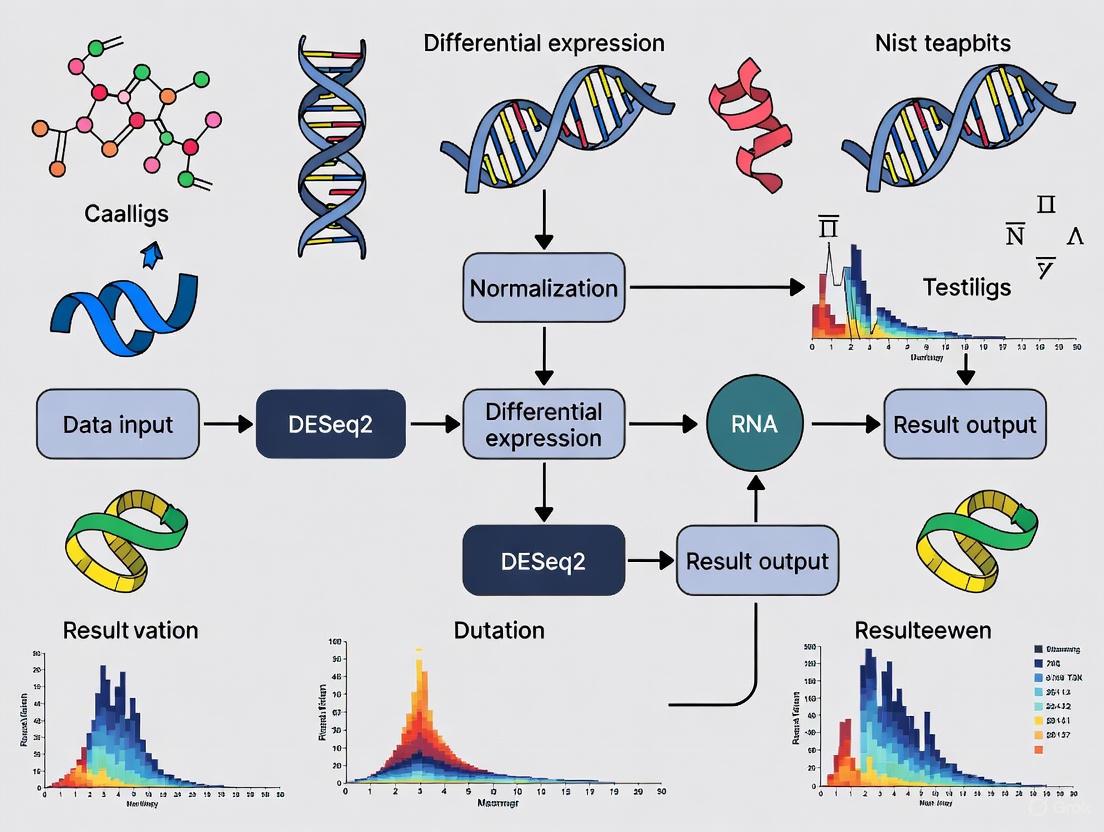

The following diagram illustrates the complete DESeq2 analysis workflow:

Key Experimental Protocols and Parameters

Input Data and Constructing a DESeqDataSet

The analysis begins with the creation of a DESeqDataSet object, which stores the count data, sample information, and model formula. DESeq2 can import data from various upstream quantification tools [2] [9].

Table: Methods for Creating a DESeqDataSet Object

| Method/Function | Input Data Type | Common Upstream Tools | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

DESeqDataSetFromTximport |

Transcript abundance estimates | Salmon [2], kallisto [2], Sailfish [2], RSEM [2] | Corrects for potential changes in gene length; faster than alignment-based methods [2]. |

DESeqDataSetFromMatrix |

Count matrix | featureCounts [3], HTSeq [10] | Use when a count matrix has already been generated. |

DESeqDataSet |

SummarizedExperiment object | tximeta [2] | Automatically populates annotation metadata for common transcriptomes. |

A critical step is defining the design formula using the tilde (~) operator. This formula expresses the variables in the column data that will be used to model the counts. To benefit from default settings, the variable of interest should be the last term in the formula, and the control level should be set as the first factor level [2] [3]. For example, to test for the effect of treatment while controlling for batch effects, the design would be ~ batch + treatment.

Running the Analysis and Extracting Results

The core analysis is performed with a single command:

This function executes the entire workflow: estimating size factors, estimating dispersions, fitting the dispersion trend, shrinking estimates, and fitting the models [7] [5].

Results for a specific comparison are extracted using the results() function. For factors with more than two levels, or for complex designs, the comparison must be specified with the contrast argument [10].

DESeq2 also offers log2 fold change shrinkage methods like apeglm to improve the accuracy and interpretability of fold change estimates, particularly for low-count genes [9] [1]. This is done with the lfcShrink() function.

Table: Key Parameters in a DESeq2 Analysis

| Parameter/Function | Description | Options / Notes |

|---|---|---|

fitType |

Type of fitting for dispersions to the mean intensity. | "parametric" (default), "local", "mean" [8]. |

testType |

The statistical test used for hypothesis testing. | "Wald" (default) or "LRT" (Likelihood Ratio Test) [8]. |

alpha |

The significance threshold for adjusted p-values. | Default is 0.1 [2]. |

lfcThreshold |

A non-zero log2 fold change threshold for testing. | Enables testing against a biologically meaningful threshold [1]. |

independentFiltering |

Automatically filter low-count genes to improve power. | Enabled by default [2]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful differential expression analysis requires both computational tools and well-annotated biological materials. The following table details key components for a typical DESeq2-based RNA-seq study.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq and DESeq2 Analysis

| Item / Resource | Function / Role | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome & Annotation | Provides the coordinate and feature system for read alignment and quantification. | GENCODE, Ensembl, or RefSeq human/mouse transcriptomes. Required for tools like Salmon [2] [6]. |

| Quantification Software (Pseudo-aligners) | Fast and accurate estimation of transcript/gene abundance from raw sequencing reads. | Salmon (recommended with --gcBias flag [2]), kallisto, or RSEM. |

| Alignment Software | Maps sequencing reads to a reference genome (traditional approach). | STAR (splice-aware aligner [6]), HISAT2. |

| DESeq2 R Package | Performs statistical testing for differential expression from count data. | Available via Bioconductor. Requires R [2]. |

| tximport / tximeta R Packages | Imports transcript abundance estimates and summarizes to gene-level for DESeq2. | tximport creates a list; tximeta creates a SummarizedExperiment with automatic metadata [2]. |

| BiocParallel R Package | Enables parallel computing to speed up the DESeq() and results() functions. |

Register multiple cores to reduce computation time [10]. |

| Sample Metadata (colData) | A data frame linking sample IDs to experimental conditions and covariates. | Critical: Must be accurate and match the columns of the count matrix. Used to define the design formula [6]. |

DESeq2 provides a statistically robust and computationally efficient framework for identifying differentially expressed genes in RNA-seq data. Its core innovation lies in the use of a negative binomial generalized linear model coupled with empirical Bayes shrinkage for dispersion and fold change estimates. This approach effectively handles the challenges of overdispersion and limited replication typical of sequencing experiments, leading to improved stability, interpretability, and power in differential expression analysis [1]. The standardized workflow, from raw count input to results extraction, along with its flexibility in handling complex designs, has cemented DESeq2's role as an indispensable tool for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in the field of genomics.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling comprehensive profiling of gene expression. However, two significant statistical challenges inherent to RNA-seq count data are the frequent use of low replicate numbers and the discrete nature of the data. These characteristics can compromise the power and reliability of differential expression analysis if not properly addressed. The DESeq2 package provides a robust statistical framework specifically designed to overcome these obstacles, making it an indispensable tool for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. This application note details the methodologies and advantages of using DESeq2 within a typical differential gene expression workflow, focusing on its handling of low replication and data discreteness.

The Statistical Challenges of RNA-Seq Data

Data Discreteness and Over-Dispersion

RNA-seq data is fundamentally composed of integer counts of sequencing reads mapped to genomic features. These counts are non-normally distributed and exhibit a mean-variance relationship, where the variance typically exceeds the mean—a property known as over-dispersion. Standard linear models assume normally distributed, continuous data with constant variance, making them unsuitable for raw RNA-seq counts [1]. DESeq2 employs a negative binomial generalized linear model (GLM) that accurately captures this over-dispersed count data structure, providing a more appropriate statistical foundation for inference [1] [10].

The Problem of Low Replicate Numbers

Controlled experiments in RNA-seq, particularly those involving human tissues or complex model organisms, often face practical constraints on sample size, resulting in low biological replication (often as few as 2-3 replicates per condition) [1]. With limited replicates, traditional per-gene variance estimates become highly unstable and lack statistical power. One study demonstrated that with only three biological replicates, common differential expression tools identified just 20-40% of the significantly differentially expressed (SDE) genes detected when using 42 replicates. Performance improved substantially for genes with large expression changes (>4-fold), where >85% were detected even with low replication [11]. This highlights the critical need for methods that enhance power in small-sample scenarios.

DESeq2's Statistical Framework for Enhanced Inference

Empirical Bayes Shrinkage for Dispersion Estimation

DESeq2's primary strategy for handling low replication is information sharing across genes through empirical Bayes shrinkage. Rather than estimating dispersion for each gene in isolation, DESeq2 assumes genes with similar average expression levels share similar dispersion. The method:

- Calculates initial gene-wise dispersion estimates using maximum likelihood.

- Fits a smooth curve modeling the relationship between dispersion and mean expression across all genes (Figure 1).

- Shrinks gene-wise dispersion estimates towards the curve-predicted values, generating final maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimates [1].

The strength of shrinkage is data-driven, automatically adjusting based on the dispersion variability around the fit and the available degrees of freedom (i.e., sample size). With fewer replicates, shrinkage is stronger, borrowing more information from the gene ensemble to produce stable, reliable estimates. As replication increases, shrinkage decreases, allowing gene-specific estimates to dominate [1].

Shrinkage Estimation of Logarithmic Fold Changes

For genes with low counts, logarithmic fold change (LFC) estimates are inherently noisy. DESeq2 incorporates a second empirical Bayes step that shrinks LFC estimates toward zero, using a prior distribution that models the expected effect sizes in the dataset. This shrinkage:

- Reduces the false positive rate from genes with high variance.

- Improves the power to detect true differential expression.

- Enables more accurate ranking and visualization of genes by effect size [1].

Table 1: Impact of Biological Replicates on Differential Expression Detection

| Number of Biological Replicates | Proportion of Significantly Differentially Expressed Genes Detected | Recommended Differential Expression Tool |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 20%-40% | edgeR, DESeq2 |

| 6 (minimum general recommendation) | ~50% (depending on effect size) | edgeR, DESeq2 |

| 12 (for all fold changes) | >85% | DESeq2 |

| >20 | >85% for all SDE genes | DESeq (marginally outperforms others) |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard DESeq2 Workflow

Input Data Preparation

DESeq2 requires a matrix of un-normalized integer counts (e.g., from HTSeq-count or featureCounts) and a sample information table [2] [10]. Do not supply pre-normalized data, as DESeq2 internally corrects for library size and other factors.

Protocol 4.1.1: Constructing a DESeqDataSet from a Count Matrix

Note: The design formula should reflect the experimental structure. For multi-factor designs, include all relevant variables (e.g., ~ batch + condition).

Protocol 4.1.2: Importing Transcript Abundance Quantifications with tximport

For tools like Salmon or kallisto that output transcript-level abundance, use tximport to generate gene-level count matrices while correcting for potential transcript length changes [2].

Differential Expression Analysis

The core analysis is executed with a single function, which performs size factor estimation, dispersion estimation, model fitting, and hypothesis testing.

Protocol 4.2: Running the DESeq2 Analysis Pipeline

Results Interpretation and Visualization

Protocol 4.3: Generating Diagnostic and Results Plots

Visualization of the DESeq2 Statistical Workflow

The following diagram illustrates DESeq2's core statistical workflow for handling discrete count data and low replication through information sharing across genes.

Figure 1: DESeq2 Statistical Workflow for Handling Discrete Data and Low Replication

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Analysis with DESeq2

| Item | Type | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 R/Bioconductor Package | Software | Primary tool for differential expression analysis implementing negative binomial GLM with shrinkage. |

| Salmon / kallisto | Software | Fast transcript quantification for raw read alignment and count estimation. |

| tximport / tximeta R Packages | Software | Import and summarize transcript-level abundance to gene-level counts for DESeq2. |

| HTSeq / featureCounts | Software | Generate count matrices from aligned BAM files for input to DESeq2. |

| Bioconductor | Software Platform | Provides dependency management and genomic context for DESeq2 and related packages. |

| Illumina Sequencing Platform | Laboratory Instrument | Generates short-read RNA-seq data; common source of input data. |

| Truseq RNA Library Prep Kit | Laboratory Reagent | Prepares RNA-seq libraries for sequencing on Illumina platforms. |

| RNase Inhibitors | Laboratory Reagent | Preserves RNA integrity during sample preparation and library construction. |

DESeq2 provides a statistically rigorous solution to the twin challenges of data discreteness and low replicate numbers in RNA-seq experiments. Through its use of empirical Bayes shrinkage for both dispersion and fold change estimation, it enables robust and powerful differential expression analysis even with limited samples. The standardized protocols and workflows outlined in this application note provide researchers with a reliable framework for unlocking biological insights from their transcriptomic studies, accelerating discovery in basic research and drug development.

Proper experimental design forms the foundation of robust differential gene expression (DGE) analysis using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) with DESeq2. Two particularly critical considerations that directly impact statistical power, result reliability, and biological validity are biological replicates and sequencing depth. This document outlines evidence-based recommendations for researchers designing RNA-seq experiments within the context of pharmacogenomics, drug development, and basic biological research. Optimal design choices at this stage prevent irreversible limitations in data interpretation and ensure meaningful biological conclusions from transcriptomic studies.

The Role of Biological Replicates

Definition and Importance

Biological replicates are defined as multiple, independent measurements of biological material collected from different specimens or sources under the same experimental condition. They are distinct from technical replicates, which involve repeated measurements of the same biological sample. Biological replicates are essential because they allow researchers to estimate the natural biological variability present in a population, which is separate from technical variability introduced during library preparation or sequencing [1].

In the context of DESeq2 analysis, biological replicates provide the necessary data for accurately estimating the dispersion of gene counts—a key parameter in the negative binomial generalized linear model that DESeq2 employs. Without adequate replication, dispersion estimates become unreliable, compromising the accuracy of statistical tests for differential expression [12] [1].

Consequences of Inadequate Replication

The DESeq2 package explicitly does not support analysis without biological replicates (1 vs. 1 comparison) [13]. Attempting such analysis is strongly discouraged because:

- No measures of statistical significance can be calculated for differential expression [13]

- Dispersion estimates become unstable or impossible to compute [1]

- High false positive and false negative rates are likely

- Biological conclusions cannot be generalized beyond the specific samples tested

When biological replicates are unavailable, the only option is to analyze log fold changes without significance testing, which provides limited biological insight [13].

Recommended Number of Replicates

While the optimal number of biological replicates depends on experimental constraints and expected effect sizes, general guidelines have emerged from statistical theory and practical experience:

Table 1: Recommended Biological Replicates for RNA-seq Experiments

| Experimental Scenario | Minimum Replicates per Condition | Ideal Replicates per Condition | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard experiments with moderate effect sizes | 3 | 5-6 | Balances practical constraints with reasonable power to detect 2-fold changes [13] |

| Experiments with subtle expression changes (<1.5-fold) | 5-6 | 10-12 | Increased power needed for detecting small effect sizes [1] |

| Pilot studies | 2-3 | - | Minimal level for preliminary data; limited statistical power |

| Clinical cohorts with high heterogeneity | 10+ | 20+ | Accounts for substantial biological variability in human populations |

For most experimental contexts, a minimum of three biological replicates per condition provides a reasonable balance between practical constraints and statistical needs [13]. However, power increases substantially with additional replicates, particularly for detecting subtle expression changes or working with heterogeneous populations.

Sequencing Depth Considerations

Definition and Impact on Detection Power

Sequencing depth refers to the number of sequenced reads obtained per sample, typically measured in millions of reads. Appropriate sequencing depth ensures sufficient coverage to detect expressed transcripts across the dynamic range of expression levels while maintaining cost-effectiveness.

Insufficient sequencing depth reduces the power to detect differentially expressed genes, particularly those with low expression levels. Excessive depth provides diminishing scientific returns for increased cost and may necessitate stricter multiple testing corrections due to increased detection of very low-abundance transcripts.

Recommended Sequencing Depth

Based on typical RNA-seq experiments, the following depth recommendations apply for standard bulk RNA-seq studies:

Table 2: RNA-seq Sequencing Depth Guidelines

| Application Context | Recommended Depth (Millions of Reads) | Coverage Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standard differential expression analysis | 10-30 million reads per library [13] | Adequate for detecting medium- to high-abundance transcripts |

| Studies focusing on low-abundance transcripts | 30-50+ million reads | Improved detection of transcription factors and regulatory RNAs |

| Complex genomes with high alternative splicing | 30-60 million reads | Enables more accurate isoform-level quantification |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Varies by protocol | Typically lower depth per cell but many more cells |

For most standard DGE analyses using DESeq2, targeting 20-25 million reads per library provides a robust balance between cost and detection power, as this depth typically captures most medium- to high-abundance transcripts while allowing for accurate gene-level quantification [13].

Relationship Between Replicates and Depth

When designing experiments with fixed resources, researchers must balance the number of biological replicates against sequencing depth. In general, prioritizing more biological replicates over greater sequencing depth provides better statistical power for differential expression analysis [1]. For a fixed sequencing budget, the optimal design typically includes more replicates at moderate depth rather than few replicates at very high depth.

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points in experimental design and how they interrelate:

DESeq2-Specific Technical Requirements

Input Data Specifications

DESeq2 operates on raw, un-normalized count data rather than normalized values such as counts per million (CPM) or fragments per kilobase per million (FPKM) [2] [14]. The package expects a matrix of integer values representing the number of sequencing reads or fragments assigned to each gene in each sample. These raw counts allow DESeq2 to correctly assess measurement precision, as the variance of count data depends on the mean count value [2] [14].

DESeq2 internally corrects for differences in library size (sequencing depth) using its median-of-ratios method for size factor estimation [1]. The package does not require gene length normalization during this process, as gene length remains constant across samples and therefore does not affect differential expression comparisons [13].

Experimental Design Formula

Proper specification of the design formula is critical for DESeq2 analysis. The formula should include all major known sources of variation in the experiment, with the variable of interest specified last [2] [12]. For example, if studying treatment effects while accounting for sex differences, the design formula would be: ~ sex + treatment.

For paired experimental designs (e.g., before and after treatment in the same subjects), the design must include both subject and treatment information: ~ subject + condition [13]. This approach estimates treatment effect while accounting for inherent differences between subjects.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete DESeq2 analysis process with emphasis on the critical design considerations:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for RNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA extraction kit (e.g., column-based) | Isolation of high-quality RNA from biological samples | Select based on sample type (cells, tissues, FFPE); prioritize RNA integrity |

| DNase treatment reagents | Removal of genomic DNA contamination | Critical for accurate RNA quantification; reduces background noise |

| Ribosomal RNA depletion kits | Enrichment for mRNA by removing abundant rRNA | Essential for non-polyA transcripts (e.g., bacterial RNA) |

| Poly(A) selection beads | Enrichment for eukaryotic mRNA | Standard for eukaryotic mRNA sequencing; may introduce 3' bias |

| Reverse transcriptase | cDNA synthesis from RNA template | High processivity important for full-length cDNA representation |

| DNA library prep kit | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries | Compatibility with sequencing platform; efficiency for low-input samples |

| Size selection beads | Fragment size selection for libraries | Critical for insert size optimization; affects sequencing uniformity |

| Quality control reagents (Bioanalyzer, Qubit) | Assessment of RNA and library quality | Essential for troubleshooting; prevents sequencing failures |

Table 4: Essential Software Tools for RNA-seq Analysis with DESeq2

| Tool/Resource | Purpose | DESeq2 Integration |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Quality control of raw sequencing data | Preliminary step before alignment |

| HISAT2/STAR | Read alignment to reference genome | Generates BAM files for read counting |

| featureCounts/HTSeq | Generation of count matrices from aligned reads | Direct input to DESeq2 |

| tximport | Import of transcript-level quantifications | Creates gene-level count matrices for DESeq2 [2] |

| IGV | Visualization of aligned reads | Validation and exploration of specific genes |

| R/Bioconductor | Statistical analysis environment | Required platform for DESeq2 implementation |

Careful attention to biological replicates and sequencing depth during experimental design substantially enhances the reliability and interpretability of RNA-seq studies using DESeq2. Researchers should prioritize adequate biological replication (minimum 3, ideally 5-6 replicates per condition) and appropriate sequencing depth (10-30 million reads per library for standard applications) to ensure statistically robust differential expression analysis. These foundational elements, combined with proper specification of the experimental design formula and use of raw count data as input, form the basis for successful transcriptomic investigations in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Differential gene expression analysis with DESeq2 requires two primary components: a raw count matrix and a sample metadata table [5] [10]. These inputs form the foundation for the statistical model that identifies expression differences between experimental conditions. The raw count matrix contains the unnormalized sequencing read counts assigned to each gene across all samples, while the sample metadata describes the experimental design and biological conditions for each sample [15] [16]. Proper preparation and formatting of these inputs is critical for generating biologically meaningful and statistically valid results, as DESeq2 uses the raw counts and the information in the metadata to model the data using a negative binomial distribution and test for differential expression [5] [17].

Raw count matrix specifications

Definition and purpose

The raw count matrix is a tabular data structure where rows represent genes (or other genomic features) and columns represent samples [10] [16]. Each value in the matrix contains the number of sequencing reads (or UMIs for UMI-based protocols) that have been uniquely assigned to a specific gene in a specific sample [17]. These counts are derived from alignment tools (like STAR/HTSeq) or pseudo-alignment methods (like Salmon or kallisto) [18] [19]. DESeq2 uses these raw counts because its statistical model internally accounts for library size differences and other technical factors during the normalization process [5] [17].

Essential characteristics

The table below outlines the critical characteristics of a properly formatted raw count matrix for DESeq2 analysis:

Table 1: Key characteristics of DESeq2 raw count matrices

| Characteristic | Requirement | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Data Type | Integer values only | Counts represent discrete sequencing reads/fragments [17] |

| Pre-normalization | No transformation or normalization | DESeq2 performs internal normalization using size factors [5] [17] |

| Missing Values | Not allowed | All genes should have counts for all samples; zeros are acceptable [10] |

| Matrix Format | Genes as rows, samples as columns | Standard format for DESeq2 input functions [15] [10] |

| Gene Identifiers | Stable identifiers (e.g., Ensembl ID, Entrez) | Avoids ambiguity from gene symbols that may change over time [19] |

Generation methods

Count matrices can be generated through various bioinformatics pipelines depending on the experimental platform. For bulk RNA-seq data, common approaches include:

- Alignment-based methods: Tools like STAR align reads to a reference genome, followed by feature counting with HTSeq-count or featureCounts [18] [17].

- Pseudo-alignment methods: Tools like Salmon, kallisto, or alevin that provide fast transcript quantification without full alignment [19] [16].

- NCBI-generated counts: For human and mouse data in public repositories, NCBI's standardized pipeline uses HISAT2 for alignment and featureCounts for quantification [20].

Sample metadata requirements

Purpose and importance

The sample metadata table (also called colData) provides the experimental context for each sample, enabling DESeq2 to model the relationship between sample characteristics and gene expression patterns [5] [16]. This table connects the technical sample identifiers (matching the count matrix column names) to the biological and technical variables of interest, such as treatment conditions, time points, or batch information [10]. In complex experimental designs, proper metadata documentation is essential for specifying the statistical model that will test the hypotheses of interest [5].

Critical components

The sample metadata must include specific information to ensure proper analysis:

Table 2: Essential components of sample metadata for DESeq2

| Component | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Sample IDs | Must exactly match column names in count matrix [15] | "SRR3383696", "treated1", "control2" |

| Condition of Interest | Primary experimental factor being tested [5] | "untreated", "treated", "infected", "healthy" |

| Batch Covariates | Technical factors to control for [5] | "sequencingbatch", "libraryprep_date" |

| Biological Covariates | Biological factors that may affect expression [5] [17] | "sex", "age", "genotype" |

| Factor Levels | Proper ordering of factor levels with control as reference [15] [10] | condition: levels = c("untreated", "treated") |

Design formula specification

The metadata directly informs the design formula, which specifies how DESeq2 models the data [5] [16]. The design formula uses tilde notation (~) followed by the variables that account for major sources of variation, with the factor of interest typically specified last [5]. For example:

- Simple design:

~ condition(compares two groups) - Controlled design:

~ batch + condition(accounts for batch effects) - Paired design:

~ individual + treatment(for paired experiments) - Interaction design:

~ genotype + treatment + genotype:treatment(tests interaction effects)

Experimental workflow integration

From sequencing to count matrix

The complete workflow for generating DESeq2 inputs begins with raw sequencing data and proceeds through multiple quality control and processing steps:

Diagram 1: Workflow from raw sequences to DESeq2 analysis

Data import into DESeq2

Once the count matrix and metadata are prepared, they are imported into R using the DESeqDataSetFromMatrix() function, which requires that the column names of the count matrix exactly match the row names of the metadata table [15] [10]. Proper ordering is critical, as DESeq2 will not guess which column of the count matrix belongs to which row of the metadata [15]. The following example demonstrates this process:

The scientist's toolkit: Research reagent solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents, tools, and resources for RNA-seq analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Alignment Tools | STAR, HISAT2, Rsubread [20] [19] | Map sequencing reads to reference genome |

| Quantification Tools | HTSeq-count, featureCounts, Salmon [20] [19] | Generate raw counts for each gene |

| Quality Control | FastQC, RSeQC, Qualimap, Trimmomatic [18] | Assess read quality, alignment metrics |

| Reference Genomes | ENSEMBL, UCSC, GENCODE [20] [17] | Provide standardized genome sequences |

| Annotation Sources | Ensembl, Entrez, TAIR (for Arabidopsis) [21] [19] | Provide stable gene identifiers |

| Data Repositories | GEO, SRA, ArrayExpress [22] [20] | Source of public datasets and metadata |

Quality assessment and troubleshooting

Pre-analysis quality checks

Before performing differential expression analysis, several quality checks should be performed on both the count matrix and metadata:

- Count matrix checks: Verify that the matrix contains only integer values, check for excessive zeros, and confirm that row sums are reasonably distributed [10] [18].

- Metadata checks: Ensure factor levels are properly ordered with control as reference level, confirm no missing values, and verify that sample IDs exactly match count matrix column names [15] [10].

- Sample-level QC: Examine library sizes, gene detection rates, and outlier samples using PCA or other multivariate methods [18] [17].

Common issues and solutions

- Issue: "Error in DESeqDataSetFromMatrix: countData and colData have different numbers of columns"

- Solution: Verify that all samples in colData are present in countData and vice versa [15].

- Issue: Inflated false positives due to batch effects

- Solution: Include batch as a covariate in the design formula [5].

- Issue: Overabundance of zeros leading to inflated fold changes

- Solution: Use lfcShrink for effect size estimation [17].

- Issue: Low power to detect differential expression

- Solution: Ensure sufficient biological replicates and check for appropriate sequencing depth [18].

The importance of proper controls and minimizing batch effects in experimental design

In high-throughput genomic studies, such as differential gene expression analysis with RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), batch effects represent a significant challenge to data integrity and biological interpretation. Batch effects are unwanted technical variations introduced into data due to factors unrelated to the biological question under investigation [23] [24]. These non-biological fluctuations can arise from differences in sample collection, inconsistencies in pre-experimental processing, reagent lot changes, instrument drift over time, operator variability, or environmental conditions such as humidity and temperature [23]. In the context of DESeq2 research, which relies on accurate count data from RNA-seq experiments, batch effects can distort true biological signals and lead to both false positives and false negatives in differential expression testing [24].

The critical impact of batch effects stems from their potential to confound biological signals of interest. When technical variation correlates with experimental conditions, it becomes challenging to distinguish true differential expression from technical artifacts. This is particularly problematic in longitudinal studies or multi-batch experiments where biological variation may be masked by artificial technical noise [23]. Research has demonstrated that batch effects can affect a substantial proportion of features in a dataset, with one study noting that up to 99.5% of features showed significant correlation with technical variables [25]. For researchers using DESeq2 for differential expression analysis, understanding, detecting, and correcting for batch effects is therefore not merely optional but essential for producing robust, reproducible results.

Batch effects in RNA-seq experiments can originate from multiple technical sources throughout the experimental workflow. Sample preparation inconsistencies represent a major source, including variations in extraction duration, solvents used, or processing times by different technicians [23]. Instrumental factors also contribute significantly, with LC-MS systems exhibiting drift over time due to calibration changes or performance degradation. Additionally, environmental conditions such as room temperature and humidity fluctuations can introduce systematic biases, while reagent lot changes may alter background signals or reaction efficiencies [23]. Even the injection order of samples in large sets can create detectable patterns of technical variation that correlate with run sequence rather than biological groups.

The confounding nature of batch effects becomes particularly problematic when the batch variable correlates with the biological variable of interest. For instance, if all control samples are processed in one batch and all treatment samples in another, any observed differences become inextricably linked to the technical processing differences [24]. This confounding can lead to spurious findings where technical artifacts are misinterpreted as biological signals, or can mask true biological effects by introducing additional variance that reduces statistical power [24] [25]. The consequences extend beyond individual studies, as failure to account for batch effects can decrease reproducibility in meta-analyses and lead to inefficient resource utilization in follow-up studies [25].

Impact on Differential Expression Analysis with DESeq2

DESeq2 relies on accurate modeling of count data using negative binomial distributions to identify differentially expressed genes [2] [5]. When batch effects are present but unaccounted for, they violate key assumptions of the statistical model. The extra technical variation introduced by batch effects can inflate variance estimates, leading to reduced power to detect true differential expression. Conversely, when batch effects correlate with experimental conditions, they can produce artificially inflated fold changes that result in false positives [24].

The normalization process in DESeq2, which uses a median of ratios method to estimate size factors, assumes that most genes are not differentially expressed [5]. Batch effects that systematically alter the expression levels of large numbers of genes can disrupt this normalization, leading to improper adjustment of library size differences. Similarly, the dispersion estimation process, which models within-group variability, can be significantly impacted by batch effects, particularly when samples from the same biological group are processed in different batches with different technical artifacts [5].

Strategies for Minimizing Batch Effects Through Experimental Design

Proactive Experimental Design

The most effective approach to managing batch effects begins with proactive experimental design that anticipates and minimizes technical variation before data generation. When possible, processing all samples in a single batch represents the most straightforward solution, as it eliminates inter-batch variation entirely [23]. However, for large studies where multiple batches are unavoidable, strategic sample allocation across batches becomes critical to prevent confounding of technical and biological variables.

Randomization of sample order across batches ensures that no experimental group is disproportionately affected by technical variation. This approach distributes batch effects randomly across biological groups, making it easier to statistically separate technical from biological variation during analysis [23]. For complex studies with multiple potentially confounding variables, more sophisticated allocation methods have been developed, including anticlustering algorithms that explicitly avoid forming unwanted clusters of similar elements when dividing data into groups [26]. These methods actively maximize the similarity between batches with respect to known covariates, creating more balanced experimental designs.

Table 1: Batch Effect Minimization Strategies in Experimental Design

| Strategy | Implementation | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Batch Processing | Process all samples in one continuous run | Eliminates inter-batch variation | Often impractical for large studies |

| Randomization | Randomly assign samples to batches | Simple to implement; breaks systematic confounding | May not balance multiple covariates |

| Stratified Randomization | Randomize within strata defined by key covariates | Balances important known variables | Requires prior knowledge of relevant covariates |

| Anticlustering | Use algorithms to maximize similarity between batches | Optimal balance of multiple covariates; prevents grouping by known variables | Computational complexity for large sample sizes |

| Propensity Score Matching | Allocate samples to minimize differences in propensity scores between batches | Handles multiple confounding variables simultaneously; dimension reduction | Requires complete covariate data before allocation |

Advanced Allocation Methods

Recent methodological advances have introduced sophisticated approaches to sample allocation that explicitly minimize batch effects. The anticlustering method developed by researchers at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf provides a systematic way to partition samples into batches while maximizing between-batch similarity [26]. This approach has been extended with a "Must-Link Method" that ensures related samples (such as multiple tissue samples from the same patient) are grouped in the same batch, enabling meaningful within-subject comparisons while maintaining balance across batches [26].

Another innovative approach utilizes propensity scores to guide sample allocation [25]. Propensity scores, which represent the probability of group membership conditional on a set of covariates, provide a dimension reduction technique that captures the overall balance in covariate distribution between groups. By selecting the batch allocation that minimizes differences in average propensity score between batches, researchers can create optimally balanced designs that minimize potential confounding [25]. Studies comparing this optimal allocation strategy to randomization and stratified randomization have demonstrated reduced bias in both null and alternative hypothesis conditions, particularly prior to batch correction [25].

Integrating Batch Effect Considerations into DESeq2 Workflow

Experimental Design Phase

Successful differential expression analysis with DESeq2 begins with thoughtful experimental planning that incorporates batch effect considerations from the earliest stages. Researchers should carefully consider all potential sources of technical variation and document them systematically. This includes recording metadata such as processing dates, technician identifiers, reagent lot numbers, and instrument calibration records. This metadata will prove essential for both statistical adjustment and troubleshooting potential issues that arise during analysis.

When designing a multi-batch experiment, researchers should utilize balanced allocation methods to ensure that biological groups of interest are proportionally represented across all batches. Additionally, including technical replicates across batches provides valuable data for assessing batch-to-batch variation and validating correction methods [23]. For RNA-seq experiments specifically, the use of quality control (QC) samples is highly recommended. These pooled QC samples, inserted at regular intervals throughout the run, allow for monitoring and correction of instrumental drift over time [23].

Sample Processing and Quality Control

During sample processing, several specific practices can help minimize batch effects. Standardizing protocols across all samples reduces introduction of technical variation, while randomizing processing order prevents systematic correlations between experimental conditions and run sequence. For large studies that necessarily span multiple batches, including internal reference samples that are processed in every batch enables direct quantification of batch effects and facilitates more effective correction [23].

The inclusion of controls specifically designed for batch effect assessment is crucial. Pooled quality control (QC) samples, created by combining equal aliquots from all samples or a representative subset, provide a technical baseline that should remain constant across batches [23]. Significant deviations in QC sample measurements between batches indicate technical variation that needs addressing. For studies expecting subtle biological effects, positive control samples with known expected differences can help verify that batch effect correction methods are not removing genuine biological signals.

Computational Approaches for Batch Effect Detection and Correction

Batch Effect Detection Methods

Before applying batch correction methods, it is essential to detect and quantify the presence and magnitude of batch effects in the data. Several visualization and statistical approaches are commonly used for this purpose. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is particularly valuable, as it can reveal clustering patterns driven by batch rather than biological variables [23] [24]. When samples group by processing batch rather than experimental condition in PCA space, batch effects are likely present.

Hierarchical clustering and heatmaps provide complementary approaches for visualizing batch-related patterns [24]. These methods can reveal systematic differences in expression profiles between batches, particularly when combined with annotation tracks that color-code samples by batch and biological group. Additionally, correlation analysis of technical replicates across batches can quantitatively assess the impact of batch effects, with decreased correlation indicating stronger batch effects [23].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Batch Effect Correction

| Method | Underlying Strategy | Best Applied When | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RemoveBatchEffect (Limma) | Linear models | Batches are known and balanced; mild to moderate effects | Can be applied to normalized counts; may not handle complex nonlinear patterns |

| ComBat | Empirical Bayes | Batch effects are severe; small sample sizes | Shrinks batch effects toward overall mean; handles known batches only |

| SVA (Surrogate Variable Analysis) | Factor analysis | Unknown batches or unmodeled factors; complex confounding | Identifies unknown technical factors; risk of removing biological signal |

| RUV (Remove Unwanted Variation) | Factor analysis using control genes | Housekeeping or negative control genes are available | Requires appropriate control genes; choice of controls is critical |

| SVR (Support Vector Regression) | QC-based non-linear correction | QC samples are available at regular intervals | Models signal drift with flexibility; requires sufficient QC samples |

Batch Effect Correction Strategies

When batch effects are detected, several computational approaches can correct for them, falling into three main categories. Internal standard-based correction relies on spiked-in standards to adjust for technical variation, but requires the internal standard and target to behave similarly, limiting its general application [23]. Sample-based correction methods assume the total metabolite content is similar across samples, using approaches like Total Ion Count (TIC) normalization, where metabolite content is divided by the sum of all metabolite contents in each sample [23].

QC-based correction methods utilize regularly interspersed quality control samples to model and remove technical variation. These include Support Vector Regression (SVR) in the metaX R package, Robust Spline Correction (RSC) also in metaX, and the Random Forest-based QC-RFSC method in statTarget [23]. These approaches use the trend observed in QC samples to correct the entire dataset, effectively removing technical drift while preserving biological signals.

Implementing Batch Effect Correction in DESeq2 Analysis

Design Formula Specification

DESeq2 provides flexible modeling capabilities that can incorporate batch information directly into the statistical model. The key mechanism for this is the design formula, which specifies the variables to be included in the differential expression model [5]. When batch effects are known and recorded, they can be included in the design formula to control for their influence while testing for the biological effect of interest.

For example, if a researcher has samples processed across three batches and wants to test for differences between treatment and control groups, while controlling for batch effects, the design formula would be:

In this formula, batch represents the batch identifier and condition represents the biological groups of interest. The order of terms is important, as DESeq2 sequentially fits the model, first estimating batch effects and then estimating condition effects after accounting for batch [5]. This approach explicitly models batch as a separate factor, effectively adjusting the condition comparisons for batch differences.

Complex Experimental Designs

For more complex experimental designs with multiple factors and potential interactions, DESeq2 can accommodate extended design formulas. For instance, if researchers suspect that the effect of treatment might differ by batch (an interaction effect), this can be modeled by including an interaction term:

However, interpretation of such models becomes more complex, and the DESeq2 vignette often recommends creating a combined factor that represents the interaction of interest [5]. For example, combining batch and condition into a single factor (e.g., batch1control, batch1treatment, batch2_control, etc.) and then using a likelihood ratio test to examine specific contrasts.

When using the combined factor approach, the design formula would be:

With this approach, specific contrasts of interest can be tested using the contrast argument in the results() function. This provides flexibility in testing particular comparisons while controlling for batch effects.

Validation and Quality Assessment Post-Correction

Assessing Correction Effectiveness

After applying batch correction methods, it is crucial to validate their effectiveness and ensure that biological signals have not been unintentionally removed. Several approaches can be used for this validation. Principal Component Analysis should be repeated post-correction to verify that batch-driven clustering has been reduced or eliminated while biological groupings remain intact [23] [24]. Similarly, correlation analysis of technical replicates should show improved correlation after correction [23].

The negative control approach utilizes genes or samples known not to differ between biological groups to verify that correction hasn't introduced spurious differences. Conversely, positive controls (genes known to be differentially expressed) should maintain their significant differences after correction. When available, validation by orthogonal methods such as qPCR on a subset of genes provides the strongest evidence that correction has preserved biological truth while removing technical artifacts [27].

Managing Overcorrection and Signal Loss

A significant risk in batch effect correction is overcorrection, where biological signal is inadvertently removed along with technical variation. This occurs particularly when batch effects are partially confounded with biological effects, or when correction methods are too aggressive. Studies have reported instances where methods like Robust Spline Correction (RSC) and QC-RFSC actually decreased replicate correlation, indicating potential overcorrection or model mismatch [23].

To minimize this risk, researchers should apply multiple correction strategies and compare results, using visualization techniques to ensure biological patterns remain intact. Additionally, differential analysis consistency across methods can indicate robust biological findings [23]. When possible, biological validation of key findings through independent methods remains the gold standard for confirming that correction has preserved rather than removed true signals.

Successfully managing batch effects in DESeq2-based differential expression analysis requires an integrated approach spanning experimental design, processing, computational correction, and validation. No single batch correction method universally outperforms others across all datasets [23], making methodological flexibility and validation essential. Researchers should prioritize preventive measures through balanced experimental design whenever possible, as well-designed experiments with minimal confounding are more amenable to subsequent computational correction than severely confounded designs.

The most robust approach combines multiple complementary methods with careful validation to ensure that technical artifacts are removed while biological signals are preserved. By implementing these comprehensive strategies for batch effect management, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability, reproducibility, and biological validity of their DESeq2 differential expression analyses.

Integrated Batch Effect Management Workflow: This diagram illustrates the comprehensive approach to managing batch effects throughout the differential expression analysis pipeline, from experimental design to biological interpretation.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Batch Effect Management

| Reagent/Material | Function in Batch Effect Management | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pooled QC Samples | Monitoring technical variation across batches | Create by combining equal aliquots from all samples; analyze at regular intervals |

| Internal Standards | Correction of technical variation per sample | Use isotopically labeled compounds; limited to same compound type |

| Reference RNA Samples | Assessment of cross-batch technical performance | Commercial reference materials; process in each batch for comparison |

| Spike-in Controls | Normalization for technical variation | Add known quantities of foreign RNA to each sample |

| Multiple Reagent Lots | Assessing lot-to-lot variability | Intentionally include multiple lots when possible to model this effect |

Differential expression (DE) analysis represents a fundamental step in understanding how genes respond to different biological conditions using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data. This analytical process identifies systematic changes in gene expression patterns across tens of thousands of genes simultaneously, while accounting for biological variability and technical noise inherent in RNA-seq experiments [28]. The field has developed several sophisticated tools to address specific challenges in RNA-seq data, including count data overdispersion, small sample sizes, complex experimental designs, and varying levels of biological and technical noise [28]. Among the most widely used tools are DESeq2, edgeR, and NOISeq, each employing distinct statistical approaches with unique strengths and limitations. Understanding these differences is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select the most appropriate methodology for their specific research context and experimental design. This comparative overview examines the statistical foundations, practical implementations, and performance characteristics of these three prominent methods, providing a framework for their application in differential gene expression analysis.

Statistical Foundations and Algorithmic Approaches

Core Methodologies

The three methods employ fundamentally different statistical frameworks for identifying differentially expressed genes:

DESeq2 utilizes a negative binomial modeling approach with empirical Bayes shrinkage for dispersion estimates and fold changes. It models the observed relationship between the mean and variance when estimating dispersion, allowing a more general, data-driven parameter estimation [28] [29]. This approach aims for a balanced selection of differentially expressed genes throughout the dynamic range of the data. DESeq2 incorporates automatic outlier detection and independent filtering to improve the reliability of its results [28].

edgeR also employs a negative binomial model but with a more flexible dispersion estimation approach. It uses an empirical Bayes procedure to moderate the degree of overdispersion across transcripts by borrowing information between genes, improving the reliability of inference [30] [29]. edgeR offers multiple testing strategies, including exact tests analogous to Fisher's exact test but adapted for overdispersed data, as well as quasi-likelihood options [30] [28].

NOISeq represents a non-parametric approach that contrasts fold changes and absolute expression differences within conditions to determine a null distribution, then compares observed differences to this null [31] [29]. Unlike the model-based approaches, NOISeq does not assume specific data distributions, making it less restrictive but requiring larger sample sizes to achieve good statistical power [32] [31].

Data Handling and Normalization

Each method employs distinct strategies for data normalization and variance handling:

DESeq2 performs internal normalization based on the geometric mean and uses adaptive shrinkage for dispersion estimates and fold changes [28] [15]. It calculates size factors to account for differences in sequencing depth across samples [33].

edgeR typically uses TMM normalization (Trimmed Mean of M-values) to correct for composition biases between samples, which adjusts to minimize differences in expression levels between samples when most genes are not expected to be differentially expressed [34] [29].

NOISeq offers multiple normalization options including RPKM, TMM, and upper quartile normalization, providing flexibility to address different technical biases [31] [29]. The package includes comprehensive quality control tools to guide normalization choices based on detected biases.

Table 1: Statistical Foundations of DESeq2, edgeR, and NOISeq

| Aspect | DESeq2 | edgeR | NOISeq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Statistical Approach | Negative binomial modeling with empirical Bayes shrinkage | Negative binomial modeling with flexible dispersion estimation | Non-parametric method using fold changes and absolute differences |

| Data Distribution Assumption | Negative binomial distribution | Negative binomial distribution | No specific distribution assumption |

| Differential Expression Test | Wald statistical test | Exact test or quasi-likelihood F-tests | Comparison to empirically derived null distribution |

| Normalization Method | Internal normalization based on geometric mean | TMM normalization by default | RPKM, TMM, or upper quartile normalization |

| Variance Handling | Adaptive shrinkage for dispersion estimates and fold changes | Empirical Bayes moderation of overdispersion across genes | No explicit variance modeling; relies on empirical distributions |

Performance Characteristics and Method Comparison

False Discovery Rate Control and Power

Recent evaluations have revealed crucial differences in how these methods control false discoveries, particularly in studies with large sample sizes:

A 2022 study published in Genome Biology demonstrated that when analyzing human population RNA-seq samples with large sample sizes (ranging from 100 to 1376), DESeq2 and edgeR exhibited exaggerated false positive rates [32]. In permutation analyses where any identified differentially expressed genes should theoretically be false positives, DESeq2 and edgeR had 84.88% and 78.89% chances, respectively, to identify more DEGs from permuted datasets than from the original dataset [32]. The actual false discovery rates of DESeq2 and edgeR sometimes exceeded 20% when the target FDR was 5% [32].

In contrast, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (a non-parametric method similar in spirit to NOISeq) consistently controlled the FDR under a range of thresholds from 0.001% to 5% in the same study [32]. NOISeq, as a non-parametric method, has been reported to efficiently control false discoveries in experiments with biological replication [31]. This suggests that for population-level RNA-seq studies with large sample sizes, non-parametric methods like NOISeq may provide more reliable FDR control.

Sample Size Considerations and Robustness

The performance of these methods varies significantly with sample size:

DESeq2 generally performs well with moderate to large sample sizes (≥3 replicates, performs better with more) and can handle high biological variability and subtle expression changes effectively [28]. However, its performance deteriorates with very large sample sizes in population studies, showing inflated false positive rates [32].

edgeR is particularly efficient with very small sample sizes (≥2 replicates) and large datasets, making it valuable for experiments with limited replication [30] [28]. It shows strengths in analyzing genes with low expression counts, where its flexible dispersion estimation can better capture inherent variability in sparse count data [28].

NOISeq requires larger sample sizes to achieve good power due to its non-parametric nature [32] [31]. At FDR thresholds of 1%, non-parametric methods like NOISeq had almost no power when the per-condition sample size was smaller than 8, though this improves significantly with adequate replication [32].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics Under Different Experimental Conditions

| Performance Aspect | DESeq2 | edgeR | NOISeq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal Sample Size | ≥3 replicates, performs well with more | ≥2 replicates, efficient with small samples | Requires larger sample sizes (≥8 per condition) |

| FDR Control in Large Samples | Problematic (actual FDR can exceed 20%) | Problematic (actual FDR can exceed 20%) | Robust FDR control |

| Power with Small Samples | Moderate | Good | Limited |

| Robustness to Outliers | Moderate | Moderate | High (due to non-parametric nature) |

| Handling Low-Count Genes | Conservative | Good with flexible dispersion | Requires careful filtering |

| Computational Efficiency | Can be intensive for large datasets | Highly efficient, fast processing | Moderate |

Practical Implementation and Workflow

DESeq2 Implementation Protocol

DESeq2 operates through a structured workflow that can be implemented in R:

Step 1: Data Preparation and Pre-filtering

- Read the count matrix into R, ensuring row names are gene identifiers and column names are samples

- Create a sample information data frame (colData) that specifies experimental conditions

- Ensure that columns of the count matrix and rows of the column data are in the same order [15]

- Perform minimal pre-filtering to remove genes with very few reads (e.g., fewer than 10 reads total across all samples) to reduce memory usage and improve speed [15] [10]

Step 2: DESeqDataSet Construction

- Construct a DESeqDataSet object using the

DESeqDataSetFromMatrix()function, specifying the count data, column data, and design formula [15] [10] - The design formula should reflect the experimental design, typically starting with "~" followed by the condition of interest

- Explicitly set factor levels using

factor()orrelevel()to control the reference level for comparisons [15]

Step 3: Differential Expression Analysis

- Run the core analysis using

DESeq()function, which performs estimation of size factors, dispersion estimation, and negative binomial GLM fitting [10] [33] - Extract results using the

results()function, specifying contrast if the design is multi-factorial [10] - Apply log-fold change shrinkage using

lfcShrink()to improve accuracy for visualization and ranking of genes [33]

Step 4: Results Interpretation

- Filter results based on adjusted p-values and log-fold change thresholds

- Perform visualization using MA-plots, PCA plots, or heatmaps to explore results

- Export significant differentially expressed genes for downstream analysis

edgeR Implementation Protocol

edgeR provides alternative approaches for differential expression analysis:

Step 1: Data Object Creation

- Read count data into R and create a DGEList object using

DGEList()function, combining counts and group information [34] - The group factor should specify the experimental condition for each sample

Step 2: Filtering and Normalization

- Filter lowly expressed genes using

filterByExpr()to retain genes with sufficient counts across samples [34] - Perform TMM normalization using

calcNormFactors()to correct for composition biases between samples [34]

Step 3: Dispersion Estimation and Testing

- Create a design matrix using

model.matrix()based on the experimental design - Estimate dispersions using

estimateDisp()to model biological variability [34] - For simple designs, use exact tests; for complex designs, use GLM approaches

- Perform quasi-likelihood F-tests using

glmQLFit()andglmQLFTest()for more rigorous statistical testing [34]

Step 4: Results Extraction

- Extract top differentially expressed genes using

topTags()with specified FDR threshold [34] - Consider adjusting results based on log-fold change thresholds in addition to statistical significance

NOISeq Implementation Protocol

NOISeq offers a non-parametric alternative with integrated quality control:

Step 1: Data Input and Quality Control

- Read count data into R and create a NOISeq data object

- Perform comprehensive quality control using NOISeq's diagnostic tools, including:

- Biotype detection plots to visualize percentage of genes detected per biotype

- Saturation plots to assess sequencing depth adequacy

- GC content and length bias plots to identify technical biases [31]

Step 2: Data Filtering and Normalization

- Apply low-count filtering using one of NOISeq's methods (CPM, proportion test, or Wilcoxon test) that consider the experimental design [31]

- Choose appropriate normalization based on quality control results (RPKM, TMM, or upper quartile)

Step 3: Differential Expression Analysis

- For experiments with biological replicates, use NOISeqBIO which implements an empirical Bayes approach to handle biological variability [31]

- Specify the comparison of interest and run the core analysis

- The method computes statistics based on fold changes and absolute expression differences compared to empirically derived null distributions

Step 4: Results Exploration

- Extract differentially expressed genes based on probability thresholds

- Utilize NOISeq's visualization capabilities to explore results, including expression plots, MD plots, and chromosomal distribution of DEGs [31]

Experimental Design Considerations and Recommendations

Method Selection Guide

Choosing between DESeq2, edgeR, and NOISeq depends on multiple factors:

For experiments with small sample sizes (n < 5 per group), edgeR is often preferable due to its efficient handling of limited replication and robust performance with minimal replicates [28]. Its flexible dispersion estimation provides good power even with few samples.

For moderate-sized experiments (5 ≤ n ≤ 20) with complex designs involving multiple factors, DESeq2 offers excellent capabilities for modeling complex relationships and provides reliable results with good FDR control [28]. Its sophisticated shrinkage estimation improves accuracy for low-count genes.

For large population studies (n > 50), non-parametric methods like NOISeq become advantageous due to their robust false discovery rate control [32]. As sample size increases, the power limitations of non-parametric methods diminish while their robustness to model assumptions becomes increasingly valuable.

For data with suspected outliers or severe violations of distributional assumptions, NOISeq provides a safer alternative as it doesn't rely on specific parametric assumptions [31]. This is particularly relevant when analyzing data from novel organisms or experimental conditions where distributional properties may be unknown.

For routine analyses with standard experimental designs, both DESeq2 and edgeR perform well and often show substantial concordance in their results [28]. The choice between them may depend on specific analytical needs or personal preference.

Integrated Analysis Strategy

Given the complementary strengths of these methods, an integrated approach can provide more robust results:

Primary analysis with multiple methods: Run both parametric (DESeq2 or edgeR) and non-parametric (NOISeq) methods, focusing on genes identified as significant by multiple approaches. This conservative strategy reduces false positives at the potential cost of some false negatives.

Method-specific validation: For genes identified by only one method, perform additional scrutiny based on effect size, biological plausibility, and experimental validation potential.

Quality assessment: Use NOISeq's comprehensive quality control metrics to inform data preprocessing decisions regardless of the primary analysis method chosen.

Power considerations: When designing experiments, consider the methodological requirements – non-parametric methods typically require larger sample sizes to achieve equivalent power to parametric approaches.

Diagram 1: Method Selection Workflow for Differential Expression Analysis

Computational Tools and Software Packages

Successful differential expression analysis requires specific computational tools and resources:

R Programming Environment: The foundational platform for all three methods, providing the computational environment for statistical analysis and visualization [15] [34]. R serves as the common interface for package installation, data manipulation, and analysis execution.

Bioconductor Project: A repository for bioinformatics packages including DESeq2, edgeR, and NOISeq [30] [31]. Bioconductor provides standardized installation and maintenance of these specialized tools along with extensive documentation.

DESeq2 Package: Specialized software for differential analysis of count-based RNA-seq data, implementing negative binomial generalized linear models with empirical Bayes shrinkage [15] [10]. Key functions include DESeqDataSetFromMatrix(), DESeq(), and results() for core analysis workflow.

edgeR Package: Software for examining differential expression of replicated count data using an overdispersed Poisson model to account for biological and technical variability [30] [34]. Essential functions include DGEList(), calcNormFactors(), and glmQLFTest().

NOISeq Package: Comprehensive resource for quality control and non-parametric analysis of count data, featuring both NOISeq and NOISeqBIO methods [31]. Provides extensive diagnostic plots and normalization options.

Additional Utility Packages: Supporting packages such as pheatmap for visualization, data.table for efficient data handling, and BiocParallel for parallel processing to reduce computation time [15] [10].

Proper analysis requires specific data formats and resources:

Raw Read Counts: Table of non-normalized sequence read counts at gene or transcript level, typically generated by tools like HTseq-count or featureCounts [10] [33]. Must be in matrix format with genes as rows and samples as columns.

Sample Metadata: Data frame specifying the experimental design, including sample identifiers, experimental conditions, and any batch information [10]. Critical for proper experimental design specification in all three methods.

Gene Annotation Data: Optional but recommended feature data containing gene identifiers, symbols, and genomic coordinates to enhance biological interpretation of results [15].

Quality Control Metrics: Pre-computed quality assessments from sequencing pipelines, including mapping statistics, insert size distributions, and sequencing depth information to inform analytical decisions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Formats | Function in Analysis | Method Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Software | DESeq2 R Package | Negative binomial GLM with empirical Bayes moderation | Primary analysis tool |

| edgeR R Package | Negative binomial modeling with flexible dispersion | Primary analysis tool | |

| NOISeq R Package | Non-parametric differential expression analysis | Primary analysis tool | |

| Input Data | Raw Count Matrix | Unnormalized read counts for genes across samples | Required for all methods |