A Comprehensive Guide to Differentially Methylated Cytosine (DMC) Calling Tools: Benchmarking, Application, and Best Practices

This article provides a comprehensive overview of computational methods for identifying Differentially Methylated Cytosines (DMCs) from bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq) data.

A Comprehensive Guide to Differentially Methylated Cytosine (DMC) Calling Tools: Benchmarking, Application, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of computational methods for identifying Differentially Methylated Cytosines (DMCs) from bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq) data. It covers foundational concepts of DNA methylation, details the statistical models underpinning major DMC detection tools, and offers a comparative analysis of their performance based on benchmarking studies. Aimed at researchers and bioinformaticians, the guide also delivers practical advice on parameter optimization, troubleshooting for common challenges like limited replicates, and validation strategies to ensure biologically meaningful results in disease research.

Understanding DMCs: The Role of DNA Methylation in Biology and Disease

Biological Foundations of DNA Methylation

DNA methylation is a fundamental epigenetic modification involving the addition of a methyl group to the 5' position of cytosine, primarily at CpG dinucleotides, resulting in 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [1]. This modification regulates gene expression and chromatin structure without altering the underlying DNA sequence [1]. DNA methylation is essential for numerous biological processes including genomic imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, transposon silencing, cellular development, and differentiation [1].

The functional consequence of DNA methylation depends critically on its genomic context. Methylation within promoter regions typically suppresses gene expression by promoting chromatin densification [2]. In contrast, gene body methylation involves complex regulatory mechanisms that influence gene expression and maintain genomic stability, potentially increasing transcription by regulating splicing processes [2]. During development, the overall pattern of DNA methylation established in the early embryo serves as a sophisticated mechanism for maintaining a genome-wide network of gene regulatory elements in an inaccessible chromatin structure [3]. As development progresses, programmed demethylation in each cell type then provides specificity for maintaining select elements in an open structure, allowing these regulatory elements to interact with transcription factors and define cell identity [3].

Analytical Methods for DNA Methylation Profiling

Accurate assessment of DNA methylation patterns is essential for understanding their role in biological processes and disease mechanisms. The following table compares the principal technologies used for genome-wide DNA methylation analysis:

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Methylation Detection Methods

| Method | Resolution | Genomic Coverage | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | ~80% of CpGs; entire genome | Gold standard; high coverage; base-pair resolution | DNA degradation; requires deep sequencing; resource-intensive computational processing | Whole-genome methylation in high-quality DNA samples [4] |

| Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq) | Single-base | Comprehensive genome-wide | Reduced DNA damage; better with low-input samples; distinguishes 5mC and 5hmC | Relatively new with fewer comparative studies | High-precision profiling in low-input or degraded samples [2] [4] |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) | Single-base (direct detection) | Long-read capability enables access to repetitive regions | Direct methylation detection; long-read phasing; minimal sample processing | Higher error rates; more DNA required; fewer established pipelines | Phasing methylation with genetic variants; repetitive regions [2] [4] |

| Illumina MethylationEPIC Microarray | Predefined CpG sites | >935,000 CpG sites | Cost-effective for large samples; well-established; high reproducibility | Limited to predefined sites; favors CpG islands; no sequencing data | Large-scale studies where predefined coverage is sufficient [2] [4] |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Single-base | ~5-10% of CpGs | Cost-effective; focused on CpG islands and promoters | Limited genome coverage; biased for high CpG density | Cost-sensitive studies focusing on CpG islands and promoters [4] |

| meCUT&RUN | Regional (base-pair optional) | Captures 80% of methylation with 20-50M reads | 20-fold less sequencing than WGBS; low-cost; robust with 10,000 cells | Nonquantitative; no percent methylation analysis | Cost-sensitive studies where base-pair resolution isn't required [4] |

Recent comparative evaluations demonstrate that EM-seq shows the highest concordance with WGBS, indicating strong reliability due to similar sequencing chemistry, while ONT sequencing captures certain loci uniquely and enables methylation detection in challenging genomic regions [2]. Despite substantial overlap in CpG detection among methods, each technique identifies unique CpG sites, emphasizing their complementary nature in comprehensive methylome analysis [2].

DNA Methylation in Development and Disease

During embryonic development, DNA methylation patterns undergo dynamic reprogramming [3]. The establishment and maintenance of cell-type specific methylation patterns are critical for cellular differentiation and tissue-specific gene expression [3]. This programmed demethylation allows regulatory elements to interact with transcription factors to establish the gene expression profiles that define cellular identity [3].

In cancer, DNA methylation patterns are frequently altered, with tumors typically displaying both genome-wide hypomethylation and hypermethylation of CpG-rich gene promoters [1]. Promoter hypermethylation of key tumor suppressor genes is commonly associated with gene silencing, while global hypomethylation can induce chromosomal instability [1]. These alterations often emerge early in tumorigenesis and remain stable throughout tumor evolution, making cancer-specific DNA methylation patterns highly relevant as biomarkers [1].

The stability of the DNA double helix provides additional protection compared to single-stranded nucleic acid-based biomarkers, and methylated DNA fragments appear enriched within circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) due to nucleosome interactions that protect them from nuclease degradation [1]. These features contribute to the high potential of DNA methylation-based biomarkers for liquid biopsy applications in cancer detection and monitoring [1].

Experimental Protocols for Methylation Analysis

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing Protocol

Principle: Sodium bisulfite converts unmethylated cytosines to uracil, while methylated cytosines remain unchanged, allowing base-pair resolution DNA methylation sequencing across the entire genome [4].

Procedure:

- DNA Quality Control: Assess DNA purity using NanoDrop (260/280 and 260/230 ratios) and quantify using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit Fluorometer) [2].

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat DNA (500ng recommended) with sodium bisulfite using commercial kits (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation Kit, Zymo Research) [2].

- Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries following manufacturer protocols with bisulfite-converted DNA.

- Sequencing: Perform deep sequencing on appropriate platforms (Illumina recommended) to achieve sufficient coverage.

- Data Analysis: Process data using established bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., Bismark, MethylKit) to determine methylation status reported as β-values (ratio of methylated probe intensity to total intensity) [2].

Technical Notes: Bisulfite treatment causes DNA fragmentation; input DNA quality is critical. Include unmethylated and methylated controls to assess conversion efficiency [4].

Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing Protocol

Principle: Enzymatic conversion using TET2 and T4-BGT proteins protects modified cytosines while APOBEC deaminates unmodified cytosines, providing gentler alternative to bisulfite treatment [4].

Procedure:

- DNA Input: Use 1-100ng of DNA as starting material.

- Enzymatic Conversion: Treat DNA with TET2 enzyme to oxidize 5mC to 5caC and include T4-BGT to glucosylate 5hmC, protecting both from deamination.

- APOBEC Treatment: Apply APOBEC to deaminate unmodified cytosines to uracils.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Proceed with standard library prep and sequencing.

- Data Analysis: Use modified pipelines accounting for enzymatic conversion chemistry.

Technical Notes: EM-seq better preserves DNA integrity, reduces sequencing bias, improves CpG detection, and can handle lower DNA inputs compared to WGBS [2] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Methylation Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) | Bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines for downstream analysis [2] |

| Enzymatic Conversion Modules | EM-seq Kit (New England Biolabs) | Enzymatic conversion of unmodified cytosines preserving DNA integrity [4] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Nanobind Tissue Big DNA Kit; DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | High-quality DNA extraction from various sample types [2] |

| Methylation Arrays | Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip | High-throughput analysis of >935,000 CpG sites [2] |

| Targeted Methylation Analysis | Methylation-Specific PCR; Digital PCR | Locus-specific methylation validation with high sensitivity [1] |

| Antibodies for Enrichment | 5-Methylcytosine Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of methylated DNA (MeDIP) [4] |

| Long-read Sequencing | Oxford Nanopore; PacBio | Direct detection without conversion; long-range phasing [4] |

Regulatory Pathways and Workflows

DNA Methylation Analysis Workflow

Developmental Gene Regulation by DNA Methylation

Defining Differentially Methylated Cytosines (DMCs) and Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs)

DNA methylation is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism involving the covalent addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon position of cytosine residues, predominantly at cytosine-phospho-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides [5]. This chemical modification regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence, influencing chromatin structure, DNA conformation, and DNA-protein interactions [6]. In somatic cells, approximately 60-80% of CpG cytosines are methylated, with patterns varying dramatically between cell types, functional states, and disease conditions [5].

Differential methylation analysis identifies specific genomic locations where methylation patterns differ between biological conditions—such as disease versus healthy states, treated versus untreated samples, or different developmental time points. This analysis occurs at three primary levels of resolution [6]:

- DMCs (Differentially Methylated Cytosines): Individual cytosine sites showing statistically significant methylation differences between experimental groups.

- DMRs (Differentially Methylated Regions): Genomic regions containing multiple adjacent DMCs that exhibit coordinated methylation changes.

- DMGs (Differentially Methylated Genes): Genes functionally associated with DMRs in their promoter or gene body regions.

The identification of DMCs and DMRs represents a crucial initial step in understanding the functional consequences of epigenetic regulation in development, homeostasis, and disease pathogenesis [7].

Measurement Technologies for Genome-Wide Methylation Analysis

Several technologies enable genome-wide measurement of DNA methylation, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and appropriate applications [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Measurement Technologies

| Technique | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Bisulfite conversion followed by whole-genome sequencing | Single-nucleotide resolution; comprehensive genome coverage; identifies non-CpG methylation | High cost; computationally intensive; requires high sequencing depth | Single base |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Bisulfite conversion of restriction enzyme-digested fragments | Cost-effective; focuses on CpG-rich regions; lower computational demands | Limited to ~10% of genomic CpGs; bias toward CpG islands | Single base |

| Methylation Arrays (e.g., Illumina Infinium) | Bead-based probes hybridizing to bisulfite-converted DNA | High-throughput; cost-effective for large cohorts; well-established analysis pipelines | Limited to pre-defined CpG sites (~850,000 sites); genome coverage gaps | Single base (pre-defined) |

| Affinity Enrichment Methods (MeDIP/MBD) | Antibody-based enrichment of methylated DNA | Lower cost than WGBS; familiar protocol for ChIP-seq labs | Lower resolution; bias from copy number variation and CpG density | 100-500 bp |

Bisulfite conversion-based methods, particularly WGBS, represent the current gold standard for DNA methylation assessment due to their single-nucleotide resolution and comprehensive coverage [5]. The fundamental principle involves treating genomic DNA with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines in sequencing data), while methylated cytosines remain protected from conversion [5]. After PCR amplification and sequencing, methylation status is determined by comparing the ratio of cytosines to thymines at each reference cytosine position, typically calculated as C/(T+C) [8].

Computational Identification of DMCs and DMRs

Statistical Frameworks for DMC Detection

Identifying DMCs involves applying statistical tests to individual CpG sites to assess whether methylation differences between experimental groups are significant. Common approaches include [8] [7]:

- Fisher's exact test: Used when single replicates are available per group, assessing independence between methylation counts and group assignment.

- Beta-binomial regression: Accounts for biological variability and read coverage across multiple replicates.

- Logistic regression: Models methylation status as a function of experimental group and other covariates.

- Welch's t-test: Applied to methylation percentages when multiple replicates are available.

A critical challenge in DMC detection involves addressing the spatial correlation of methylation levels across neighboring CpG sites, which violates the independence assumption of many statistical tests [8]. Advanced methods like the Wavelet-Based Functional Mixed Model (WFMM) address this limitation by incorporating correlation structures across the genome, resulting in higher sensitivity and specificity—particularly for detecting weak methylation effects (<1% average difference) [8].

Algorithms for DMR Detection

DMR detection algorithms identify genomic regions with statistically significant coordinated methylation changes. These methods generally outperform single-CpG analyses by increasing statistical power and reducing multiple testing burden.

Table 2: Computational Tools for DMR Identification

| Tool | Statistical Approach | Key Features | Input Formats | Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defiant | Weighted Welch Expansion (WWE) | Fast execution; accepts 10 input formats; standalone program | BS Seeker, Bismark, BED, etc. | GNU99 standard system |

| metilene | Binary segmentation + 2D KS-test | Fast for whole genomes; minimal resource requirements | BED-like custom format | Pre-installed libraries |

| MethylKit | Logistic/Fisher's exact test | Flexible; handles multiple experimental designs | Bismark, generic tabular | R programming language |

| BSmooth | Local likelihood smoothing + t-test | Robust for low-coverage data; smooths methylation profiles | BS Seeker, Bismark | R/Bioconductor |

| BSDMR | Non-homogeneous Hidden Markov Model | Models spatial correlation; optimized for paired samples | Bismark coverage files | R programming language |

| MethylSig | Beta-binomial test | Incorporates coverage and biological variation | Bismark, BS Seeker | R/Bioconductor |

DMR definition criteria vary between tools but generally include [7] [6]:

- Minimum number of CpGs per region (typically ≥5)

- Minimum methylation difference between groups (often ≥10-20%)

- Statistical significance threshold (p-value < 0.05, adjusted for multiple testing)

- Maximum distance between adjacent CpGs (commonly 200-300 bp)

- Minimum read coverage per CpG (usually ≥5-10x)

The Defiant tool exemplifies a modern approach, employing a Weighted Welch Expansion method that considers coverage-weighted methylation percentages and allows for a limited number of non-differentially methylated CpGs within DMRs [7]. Meanwhile, BSDMR represents a Bayesian approach using a non-homogeneous hidden Markov model that explicitly accounts for genomic distance effects on correlation between neighboring CpGs, showing superior performance particularly under low read depth conditions [9].

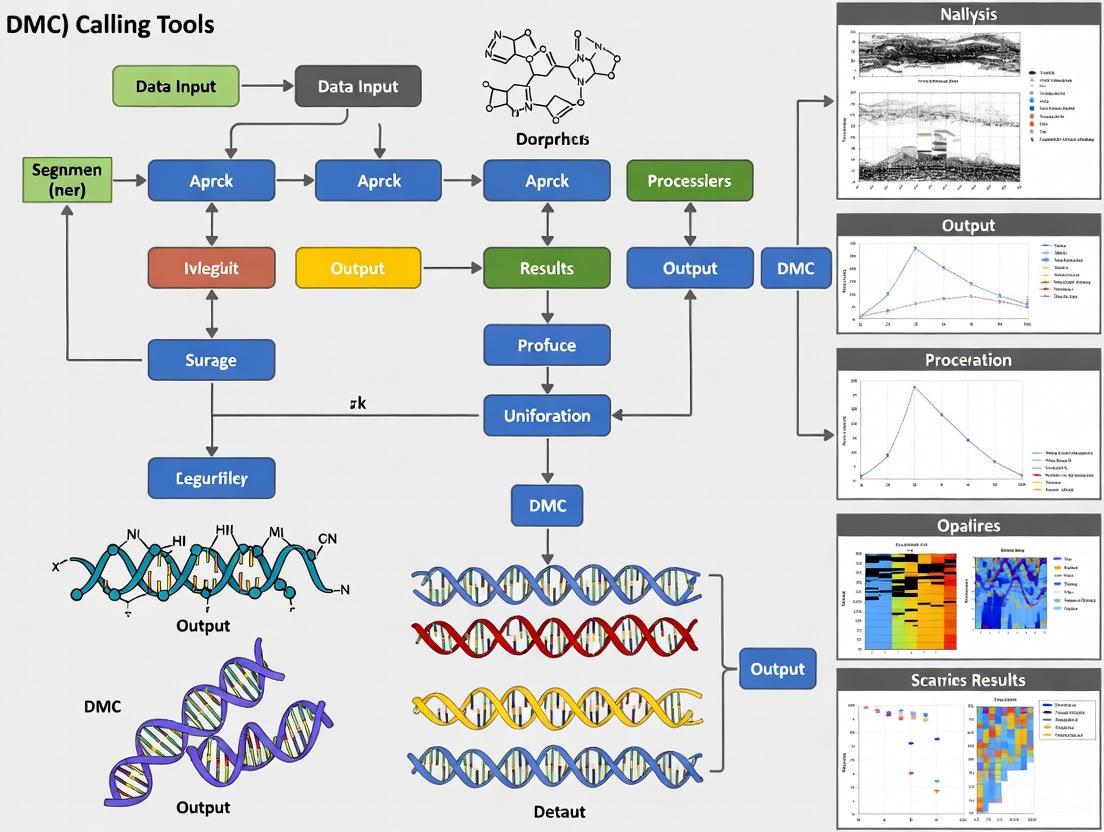

Workflow for DMC and DMR Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for identifying and analyzing DMCs and DMRs from raw sequencing data:

Figure 1: Comprehensive Workflow for DMC and DMR Analysis

Experimental Protocol for WGBS-Based DMR Identification

Library Preparation and Sequencing

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying DMRs from biological samples using whole-genome bisulfite sequencing, based on established methodologies [5] [7].

Materials:

- DNA Extraction Kit (e.g., Allprep DNA/RNA mini kit, Qiagen)

- Covaris M220 Ultrasonicator or equivalent mechanical shearing system

- NEBNext DNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs)

- Methylated Adapters (Illumina)

- Imprint DNA Modification Kit (Sigma) or equivalent bisulfite conversion kit

- Size Selection System (e.g., Pippin Prep, Sage Science)

- PfuTurbo Cx Hotstart DNA Polymerase (Agilent Technologies)

- Illumina Sequencing Platform (HiSeq/NovaSeq)

Procedure:

DNA Extraction and Quality Control

- Extract genomic DNA from tissues or cells using appropriate methods.

- Assess DNA quality and quantity using spectrophotometry (A260/280 ratio ~1.8-2.0) and fluorometry.

- Use 1μg of high-molecular-weight genomic DNA as input material.

DNA Fragmentation and Library Preparation

- Fragment DNA to 300bp using Covaris M220 ultrasonicator.

- Repair ends and adenylate 3' ends using NEBNext library preparation kit.

- Ligate methylated Illumina adapters to fragments.

Bisulfite Conversion

- Treat adapter-ligated DNA with sodium bisulfite using Imprint DNA Modification Kit.

- Conduct conversion with the following cycling conditions:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes

- Incubation: 60°C for 20-45 minutes

- Hold: 20°C indefinitely

- Purify converted DNA using provided columns or beads.

Library Amplification and Size Selection

- Amplify converted libraries using PfuTurbo Cx Hotstart DNA polymerase with the following program:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- Cycling (12-15 cycles): 95°C for 30s, 60°C for 30s, 72°C for 45s

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

- Select 300-600bp fragments using Pippin Prep system.

- Validate library quality and quantity using Bioanalyzer and qPCR.

- Amplify converted libraries using PfuTurbo Cx Hotstart DNA polymerase with the following program:

Sequencing

- Sequence libraries on Illumina platform (HiSeq2000 or equivalent) to generate 100bp single-end or paired-end reads.

- Aim for minimum 30x genome-wide coverage for mammalian genomes.

Bioinformatics Analysis

Data Processing and Alignment:

- Quality Control and Adapter Trimming

- Assess read quality using FastQC.

- Trim adapters and low-quality bases using Trim Galore! or similar tools.

Alignment to Reference Genome

- Align bisulfite-converted reads using specialized aligners (BS Seeker, Bismark, or BSMAP).

- Command example for BS Seeker:

- Calculate and verify bisulfite conversion efficiency (>99%) using spike-in controls (e.g., λ-bacteriophage genome) [5].

Methylation Calling

- Extract methylation information at each cytosine using the aligned BAM files.

- Generate coverage files containing counts of methylated and unmethylated reads per cytosine.

DMR Identification Using Defiant:

- Installation

- Download Defiant from official repository and compile:

Execution

- Run Defiant with appropriate parameters:

- Essential parameters:

- Minimum coverage: 10x per CpG

- Minimum methylation difference: 10%

- p-value threshold: 0.05

- Minimum CpGs per DMR: 5

- Maximum distance between CpGs: 300bp

Output Interpretation

- Defiant generates BED files containing genomic coordinates of significant DMRs.

- Columns include: chromosome, start, end, methylation difference, p-value, and number of CpGs.

Annotation and Functional Interpretation

Genomic Annotation of DMRs/DMCs

Annotation associates identified DMRs/DMCs with genomic features to generate biological hypotheses. Common approaches include [10]:

Gene-Based Annotation

- Associate DMRs with nearby genes using tools like genomation or ChIPseeker.

- Categorize by genomic context:

- Promoter regions: Typically defined as ±2kb from transcription start site (TSS)

- Gene bodies: Introns and exons

- Intergenic regions: Distal to annotated genes

Regulatory Element Annotation

- Overlap with ENCODE regulatory elements (enhancers, promoters, DNase hypersensitive sites).

- Integration with chromatin state segmentation maps.

Sequence Context Analysis

- CpG island annotation: Shore (0-2kb from island), shelf (2-4kb from island), open sea (>4kb from island).

- Transcription factor binding site motif analysis.

Table 3: Genomic Distribution of DMRs in a Representative Analysis

| Genomic Feature | Percentage of DMRs | Potential Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter | 28.24% | Direct transcriptional regulation |

| Exon | 15.27% | Alternative splicing, gene expression |

| Intron | 33.59% | Enhancer activity, splicing regulation |

| Intergenic | 58.02% | Long-range regulation, unknown function |

Functional Enrichment Analysis

Functional analysis interprets the potential biological consequences of methylation changes [6] [11]:

Gene Ontology (GO) Enrichment

- Identify overrepresented biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components among genes associated with DMRs.

- Use hypergeometric test with multiple testing correction (Benjamini-Hochberg FDR).

Pathway Analysis

- KEGG Pathway Enrichment: Detect signaling and metabolic pathways enriched for differentially methylated genes.

- Reactome Pathway Analysis: Identify molecular pathways and cascades affected.

Disease Association

- DisGeNET/Disease Ontology: Link DMGs to specific diseases and pathological processes.

- Integration with GWAS catalog to identify co-localization with disease-associated genetic variants.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for DMC/DMR Analysis

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | Allprep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Simultaneous DNA/RNA preservation for multi-omics |

| Bisulfite Conversion | Imprint DNA Modification Kit (Sigma) | High conversion efficiency (>99%) with minimal DNA degradation |

| Library Preparation | NEBNext DNA Methylation Kit (NEB) | Optimized for bisulfite-converted DNA |

| Targeted Methylation | EpiTYPER MassARRAY (Agena) | Validation of DMRs without sequencing |

| Data Analysis | R/Bioconductor Packages (genomation, DSS, methylKit) | Comprehensive statistical analysis and visualization |

| Genome Annotation | genomation Package | Integration of DMRs with genomic features |

| Functional Analysis | clusterProfiler R package | GO and KEGG enrichment of DMGs |

The precise identification and interpretation of DMCs and DMRs is essential for understanding the functional role of DNA methylation in biological processes and disease. While bisulfite sequencing remains the gold standard measurement technology, appropriate statistical methods that account for spatial correlation and biological variability are crucial for accurate detection. The integration of DMR/DMC data with other genomic annotations and functional genomics datasets enables researchers to move beyond mere identification to mechanistic insights, ultimately advancing our understanding of epigenetic regulation in health and disease.

Bisulfite Sequencing (BS-seq) is a cornerstone technique in epigenetics for detecting DNA methylation at single-base resolution. The method leverages the differential sensitivity of cytosine bases to sodium bisulfite conversion, allowing researchers to precisely map 5-methylcytosine (5mC) across the genome. This protocol is fundamental for studies investigating differential methylation patterns in development, disease, and drug discovery. Within the context of Differentially Methylated Cytosines (DMC) calling tools research, a robust and well-optimized BS-seq workflow is critical, as the quality of the initial data directly impacts the reliability of all downstream bioinformatic analyses [12]. This application note provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for the entire BS-seq workflow, from library preparation to methylation quantification.

The complete BS-seq workflow, from sample to analysis, involves a series of critical wet-lab and computational steps, culminating in data ready for DMC calling. The following diagram illustrates this integrated process:

Experimental Protocol

Bisulfite Conversion of Genomic DNA

Principle: Sodium bisulfite deaminates unmethylated cytosine to uracil, while methylated cytosine (5mC) remains unconverted. Subsequent PCR amplification treats uracil as thymine, creating sequence differences that reflect the original methylation status [13] [14] [12].

Materials:

- Source DNA: High-quality genomic DNA (1–10 µg) from cells, tissues, or paraffin-embedded sections [12].

- Key Reagents: Sodium bisulfite solution (3-5 M), NaOH (3 M), ammonium acetate, hydroquinone (optional), ethanol, and isopropanol [12]. Commercial kits (e.g., EpiTect Bisulfite Kit [Qiagen], EZ DNA Methylation Kit [Zymo Research]) are recommended for efficiency and consistency [12] [15].

Detailed Procedure:

- DNA Denaturation: Dilute 1-10 µg of genomic DNA in deionized water to a final volume of 18 µL. Denature the DNA by adding 2 µL of 3 M fresh NaOH and incubating at 37°C for 15 minutes [12].

- Bisulfite Treatment: Add 380 µL of a freshly prepared 5 M sodium bisulfite solution (pH 5.0) to the denatured DNA. Mix thoroughly. To prevent evaporation, overlay the reaction with 500 µL of heavy mineral oil [12].

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture in the dark at 50°C for 12–16 hours. This long incubation is crucial for complete conversion [12].

- Purification and Desulfonation: Purify the bisulfite-treated DNA using a commercial clean-up kit (e.g., Wizard DNA Clean-Up System). Elute the DNA and add NaOH to a final concentration of 0.3 M to desulphonate the DNA. Incubate at 37°C for 15 minutes [12].

- DNA Precipitation: Precipitate the DNA by adding 5 M ammonium acetate, absolute ethanol, and isopropanol. Incubate at -20°C for 2-4 hours. Pellet the DNA by centrifugation at maximum speed for 10 minutes, wash with 70% ethanol, and air-dry the pellet [12].

- Resuspension: Resuspend the purified, bisulfite-converted DNA in 10-20 µL of TE buffer or deionized water. The DNA is now ready for library preparation [12].

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Incomplete Conversion: Ensure reagents are fresh, the pH of the bisulfite solution is correct (pH 5.0), and the incubation time is sufficient.

- Low DNA Yield: Bisulfite treatment causes significant DNA degradation (up to 90%); using carrier RNA or commercial kits designed to minimize loss is advised [13].

- PCR Amplification Issues: Design bisulfite-specific primers that do not contain CpG sites and optimize PCR conditions, as the converted DNA has reduced sequence complexity [12].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Following bisulfite conversion, standard library preparation protocols are used, incorporating specific considerations. For Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS), fragmented DNA is used to construct libraries for whole-genome coverage. For Reduced-Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS), genomic DNA is digested with a restriction enzyme (e.g., MspI) to enrich for CpG-rich regions, thereby reducing sequencing costs [13]. The constructed libraries are then sequenced on an appropriate NGS platform.

Bioinformatics Analysis

Pre-mapping Quality Control and Read Trimming

Before mapping, raw sequencing reads must be assessed for quality using tools like FastQC. Adapter sequences and low-quality bases should be trimmed with tools such as Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to ensure high-quality data for alignment.

Bisulfite-Aware Read Mapping

Principle: Mapping bisulfite-treated reads is computationally challenging because the reference genome must be converted in silico to account for C-to-T (and G-to-A) changes. Specialized aligners simultaneously map reads to original and converted reference genomes [16].

Protocol using CLC Genomics Workbench:

- Tool Selection: Navigate to

Toolbox | Epigenomics Analysis | Bisulfite Sequencing | Map Bisulfite Reads to Reference[16]. - Input and Directionality: Select the trimmed read files. Critically, specify whether your library preparation protocol was directional (e.g., Illumina TruSeq DNA Methylation Kit) or non-directional (e.g., Zymo Pico Methyl-Seq). This informs the mapper which strands to expect reads from and is essential for accuracy [16].

- Reference Selection: Select the appropriate reference genome(s). Note that RAM requirements are doubled because the mapper indexes both the original and bisulfite-converted versions of the reference [16].

- Mapping Parameters:

- Cost Scheme: Adjust the match score (default 1), mismatch cost, insertion cost, and deletion cost. An affine gap cost is often preferred as it favors longer contiguous gaps over multiple short indels, which can improve mapping accuracy [16].

- Filtering Thresholds: Set the length fraction (minimum portion of the read that must align) and similarity fraction (minimum percent identity in the aligned region). The defaults (0.5 and 0.8, respectively) are a good starting point [16].

Table 1: Key Parameters for Bisulfite Read Mapping [16]

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Directionality | Specifies the library protocol type. | Must be determined from the experimental protocol. |

| Length Fraction | Minimum fraction of the read length that must align. | 0.5 - 0.9 |

| Similarity Fraction | Minimum percent identity of the aligned region. | 0.8 - 0.9 |

| Gap Cost | Cost model for insertions/deletions. | Affine (favors longer contiguous gaps) |

| Mismatch Cost | Penalty for a nucleotide mismatch. | Typically 2-3 |

Methylation Calling and Quantification

After mapping, the methylation status of each cytosine is determined. The number of reads supporting a methylated C (unconverted) versus an unmethylated C (converted to T) is counted. The methylation level (or beta-value) for a cytosine is calculated as:

[ \text{Methylation Level} = \frac{\text{Number of reads with methylated C}}{\text{Total reads covering the position}} ]

This generates a genome-wide methylation profile at single-base resolution, which is the direct input for DMC calling tools.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for the BS-seq Workflow

| Item | Function | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Chemically converts unmethylated C to U, critical for distinguishing methylation status. | EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen), EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) [12] [15]. |

| DNA Purification Kits | For cleanup and concentration of DNA after bisulfite conversion and desulphonation. | Wizard DNA Clean-Up System (Promega), QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) [12]. |

| Bisulfite-Specific PCR Primers | Amplify target regions from bisulfite-converted DNA; must be designed for sequence after conversion. | Designed to be bisulfite-specific (avoiding CpGs) and strand-specific [12]. |

| Cloning & Sequencing Vectors | Required for cloning PCR products to analyze methylation patterns of single DNA molecules. | pGEM-T Easy Vector System (Promega) [12]. |

| Bisulfite Read Mapper | Software to align sequencing reads to a reference genome, accounting for C-to-T conversions. | CLC Genomics Workbench, Bismark, BS-Seeker [16]. |

Integration with DMC Calling Tools

The final output of the BS-seq workflow is a table of methylation levels for cytosines across the genome. This data serves as the primary input for computational tools designed to identify Differentially Methylated Cytosines (DMCs) and Regions (DMRs). The choice of DMC tool (e.g., MethylKit, DSS, MethylSig, bsseq, or newer tools like DiffMethylTools) depends on the experimental design and statistical considerations [17]. The reliability of the DMC results is inherently dependent on the precision and quality control applied at every stage of the BS-seq protocol detailed in this document.

Application Notes

The reliable identification of differentially methylated cytosines (DMCs) is fundamental to advancing our understanding of epigenetic regulation in development, disease, and therapeutic intervention. However, researchers face three interconnected challenges that can compromise the validity and reproducibility of findings: technical variation introduced by profiling platforms, biological heterogeneity stemming from tissue composition and disease states, and insufficient statistical power in study design and analysis. This document outlines these challenges and provides detailed protocols to enhance the rigor of DMC detection in epigenetic research.

Navigating Technical Variation in Methylation Profiling

Technical variation arises from differences in methylation detection technologies, each with distinct strengths and limitations regarding coverage, resolution, and data structure. Inconsistent results often stem from this technical landscape rather than true biological differences.

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Methylation Detection Methods

| Method | Resolution | Genomic Coverage | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | ~80% of CpGs (unbiased) | Gold standard for comprehensive profiling; detects non-CpG methylation [2] | DNA degradation from bisulfite treatment; high cost and data complexity [2] | Discovery studies requiring full genome coverage |

| Enzymatic Methyl-Seq (EM-seq) | Single-base | Comparable to WGBS | Preserves DNA integrity; high concordance with WGBS [2] | Relatively new method; less established protocols [2] | Studies where DNA integrity is a primary concern |

| Illumina EPIC Array | Pre-defined CpG sites | ~850,000 CpG sites | Cost-effective; standardized processing; large sample capacity [2] | Limited to pre-designed probes; cannot discover novel CpGs [2] | Large-scale epidemiological or validation studies |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) | Single-base (Long-read) | High, including challenging regions | Long reads for haplotype resolution; no bisulfite conversion [2] | Higher DNA input required; lower agreement with WGBS/EM-seq [2] | Detecting methylation in complex, repetitive regions |

Accounting for Biological Heterogeneity

Biological heterogeneity manifests at multiple levels, from the cellular composition of bulk tissue samples to the molecular subtypes of diseases. Ignoring this heterogeneity can obscure genuine DMCs or create false positives.

A critical source of heterogeneity is the cellular composition of bulk tissue samples. A bulk tissue sample is a mixture of different cell types, each with its unique methylome. An observed methylation difference between case and control groups could be driven by a difference in the proportion of a specific cell type rather than a uniform change across all cells [18]. Furthermore, within a single disease category, such as breast cancer, significant inter-patient molecular heterogeneity exists. HER2-low breast cancers, for instance, comprise distinct subgroups that molecularly resemble either HER2-0 or HER2-positive disease, requiring separate analysis to uncover true DMCs [19].

Ensuring Statistical Power and Robust Analysis

The analysis of methylation data demands specialized statistical methods that account for its unique properties. Using inappropriate models or failing to account for data structure is a major source of low statistical power and irreproducible results.

A key consideration is model directionality. Statistical models for differential methylation implicitly assume a direction of effect. Modeling methylation (X) as dependent on a condition (Y), denoted X\|Y, is natural when the condition may affect methylation (e.g., smoking). The reverse direction, Y\|X, is more appropriate when methylation might affect the condition (e.g., mediating genetic risk for disease) [18]. Using a model with an incorrect directionality can drastically reduce performance and increase false positives [18].

Furthermore, standard methods like t-tests or ANOVA, which ignore the correlation between adjacent CpGs and the beta-binomial distribution of sequencing count data, are prone to higher false positive rates [20]. They also often discard positions with missing data, leading to substantial information loss and bias [20]. Powerful statistical methods like Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) and penalized trans-dimensional approaches are better suited for DMC detection as they can smooth methylation levels by leveraging local autocorrelation and handle missing data effectively [20].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Robust Workflow for DMC Detection from Sequencing Data

This protocol utilizes the DMCTHM R package, a method based on a penalized trans-dimensional Hidden Markov Model, which is designed to address several key statistical challenges in DMC detection [20].

1. Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- Input Material: High-quality genomic DNA.

- Platform Recommendation: For discovery studies, use WGBS or EM-seq. EM-seq is advantageous when DNA degradation is a concern [2].

- Sequencing Depth: Aim for a minimum of 10-30x coverage per CpG site to ensure reliable methylation level quantification.

2. Data Preprocessing

- Quality Control: Use FastQC to assess raw read quality.

- Adapter Trimming and Read Alignment: Trim adapters (e.g., with Trim Galore!) and align reads to a reference genome using a bisulfite-aware aligner such as

BismarkorBS-Seeker2. - Methylation Calling: Extract methylation counts (methylated and unmethylated reads per cytosine) using the alignment tool's built-in functions.

3. DMC Detection with DMCTHM

- Rationale: This method models methylated counts with a beta-binomial distribution and uses an HMM to capture correlation among adjacent CpGs. It simultaneously estimates model parameters and smooths methylation levels, which is robust to outliers and missing data [20].

- Software Installation: Install the

DMCTHMR package (Version 0.1 or higher) from a relevant repository. - Input Data Preparation: Prepare a data object containing methylated and total read counts for each CpG site across all samples.

- Model Fitting:

- Output: The function returns a list of DMCs with their genomic coordinates, methylation differences, and statistical significance.

4. Result Interpretation and Annotation

- Annotation: Annotate significant DMCs with genomic features (e.g., promoters, gene bodies, CpG islands) using packages like

GenomicRangesand annotation databases (e.g.,AnnotationHub). - Visualization: Create Manhattan plots, volcano plots, and heatmaps to visualize the distribution and effect size of DMCs.

DMC Detection Workflow: A step-by-step process from sample preparation to final result reporting.

Protocol 2: A Framework for Cell-Type-Specific DMC Analysis from Bulk Tissue

This protocol outlines the use of TCA for deconvoluting bulk methylation data to identify DMCs at the cell-type-specific level, which is crucial for understanding the true cellular origin of epigenetic signals [18].

1. Data Requirements

- Bulk Methylation Data: Matrix of methylation values (β-values or M-values) from your bulk tissue samples.

- Cell-Type Proportions: A matrix of estimated cell-type proportions for each sample. These can be derived:

- Experimentally: Using cell sorting (e.g., FACS) and profiling of pure cell populations.

- Computationally: Using reference-based deconvolution tools (e.g.,

EpiDISH,minfi) if a reference methylome is available.

2. Choosing Model Directionality with TCA

- Decision Point: The choice between X\|Y (condition affects methylation) and Y\|X (methylation affects condition) is critical and should be based on biological plausibility [18].

- X\|Y Direction: Use for most case-control studies (e.g., disease state, environmental exposure).

- Y\|X Direction: Use when investigating methylation as a potential mediator, for example, between a genetic variant and a phenotype.

3. Running TCA Analysis

- Software Installation: Install the

TCAR package. - Input Data: Prepare your bulk methylation matrix, design matrix (condition of interest), and matrix of cell-type proportions.

- Execution:

4. Validation

- Where possible, validate key findings using independent methods, such as pyrosequencing on sorted cell populations or in situ techniques.

Tissue Deconvolution Logic: Illustrates how bulk tissue methylation data is a mixture of signals from constituent cell types, which statistical deconvolution aims to resolve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for DMC Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation Kit | Bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA for WGBS or EPIC array | Efficient conversion while minimizing DNA degradation | Used in EPIC array protocol [2] |

| Nanobind Tissue Big DNA Kit | High-molecular-weight DNA extraction from tissue | Preserves long DNA fragments for long-read sequencing (ONT) or EM-seq | [2] |

| DMCTHM R Package | Statistical detection of DMCs from sequencing data | Handles missing data, autocorrelation; uses beta-binomial HMM | [20] |

| TCA R Package | Cell-type-specific analysis of bulk tissue methylation data | Deconvolutes bulk signals; allows for different model directionalities | [18] |

| Limma R Package | Differential analysis for microarray data (e.g., EPIC array) | Fits linear models with empirical Bayes moderation for stable inference | Used for DMC identification from arrays [21] |

| BSgenome.Hsapiens.UCSC.hg19 | Reference genome for annotation and coordinate mapping | Provides standardized genomic coordinates for CpG site annotation | Used for validating genomic regions [21] |

A Practical Toolkit: Statistical Models and Operational Workflows of Popular DMC Tools

The precise identification of differentially methylated cytosines (DMCs) represents a fundamental analytical procedure in epigenetics research, enabling investigators to locate individual cytosine bases exhibiting significant methylation variation between biological conditions. DMCs serve as crucial epigenetic markers associated with gene expression regulation, cellular differentiation, and disease pathogenesis [6]. The detection of DMCs typically constitutes the initial discovery phase in DNA methylation analysis, often preceding the investigation of larger differentially methylated regions (DMRs) which comprise clustered DMCs with synergistic effects [17]. The accuracy of DMC detection profoundly influences subsequent biological interpretations, making the selection of appropriate computational tools with understood assumptions and requirements a critical consideration for researchers.

DNA methylation, predominantly occurring as 5-methylcytosine (5mC) at cytosine-phospho-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides in mammalian genomes, represents a chemically stable yet biologically dynamic epigenetic mark [5]. DMC detection tools statistically compare methylation measurements between experimental groups (e.g., disease versus control, treated versus untreated) to identify CpG sites with significant methylation differences [6]. These computational approaches must account for biological variability, technical noise, and the unique statistical challenges posed by methylation data, which often consists of count-based measurements (methylated versus unmethylated reads) exhibiting binomial distributions [17] [5].

This application note provides a comprehensive comparative overview of DMC detection methodologies, emphasizing their underlying model assumptions, input requirements, and practical implementation protocols. By synthesizing this information within a structured framework, we aim to equip researchers with the necessary knowledge to select and implement appropriate DMC detection strategies for their specific experimental contexts.

Computational Tools for DMC Detection: A Comparative Analysis

Methodological Categories and Statistical Foundations

DMC detection tools employ diverse statistical frameworks that can be broadly categorized into five methodological approaches, each with distinct assumptions and performance characteristics [17]. Understanding these foundational statistical approaches is essential for selecting tools appropriate for specific experimental designs and data characteristics.

Generalized Linear Model (GLM) Based Methods represent the most prevalent category, modeling methylation counts using binomial or beta-binomial distributions to account for both biological variability and technical noise [17]. Tools in this category, including methylSig, DSS, and methylKit, implement sophisticated approaches for overdispersion estimation, which is critical for controlling false positive rates in experiments with biological replicates. These methods generally perform well with high-coverage sequencing datasets but may suffer from variance estimation instability with low-coverage data [17].

Statistical Testing-Based Methods utilize fundamental statistical tests such as Fisher's exact test, t-tests, or non-parametric alternatives to compare methylation frequencies between conditions [17]. While computationally efficient and straightforward to implement, these approaches often fail to adequately account for biological variability between replicates, potentially leading to inflated false discovery rates in heterogeneous sample populations. Methods like DMRfinder and eDMR fall into this category [17].

Smoothing-Based Methods, including BSmooth and BiSeq, employ local smoothing algorithms to aggregate information from neighboring CpG sites, reducing random noise and improving detection power for low-coverage data [17]. These methods assume correlation in methylation status between adjacent cytosines, which generally holds true in biological systems but may vary across genomic contexts.

Hidden Markov Model (HMM) Based Methods model methylation states and transitions along the genome using hidden Markov models, effectively capturing spatial dependencies in methylation patterns [17]. Tools like HMM-DM and Bisulfighter can handle low-coverage data more effectively than binomial-based methods but are computationally intensive and may be difficult to generalize across diverse experimental designs.

Linear Regression-Based Methods apply linear models to methylation levels assuming normal distribution of residuals, with implementations found in DMAP, RnBeads, and COHCAP [17]. These approaches perform optimally with high-quality, high-coverage data from array-based platforms or deeply sequenced bisulfite experiments but may lack robustness with count-based sequencing data exhibiting limited dynamic range.

Table 1: Methodological Categories of DMC Detection Tools

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Core Statistical Model | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLM-Based | methylSig, DSS, methylKit | Binomial/Beta-binomial | High-coverage data with biological replicates |

| Statistical Testing | DMRfinder, eDMR | Fisher's exact test, t-tests | Preliminary screening of high-coverage data |

| Smooth-Based | BSmooth, BiSeq | Local likelihood smoothing | Low-coverage WGBS data |

| HMM-Based | HMM-DM, Bisulfighter | Hidden Markov Model | Data with strong spatial correlation |

| Linear Model | RnBeads, COHCAP | Linear regression | Array data or high-coverage BS-seq |

Tool-Specific Implementations and Requirements

DiffMethylTools represents a recently developed end-to-end solution that addresses analytical and computational difficulties in differential methylation dissection [17]. This tool supports versatile input formats for seamless transition from upstream methylation detection tools and offers diverse annotations and visualizations to facilitate downstream investigations. Comparative evaluations on multiple datasets, including both short-read and long-read methylomes, demonstrated that DiffMethylTools achieved overall better performance in detecting differential methylation than existing tools like MethylKit, DSS, MethylSig, and bsseq [17]. The tool implements robust statistical models specifically optimized for handling the increasing volume of long-read methylation data from third-generation sequencing technologies.

SMART2 provides a comprehensive toolkit for deep analysis of DNA methylation data from bisulfite sequencing platforms, with specific functionality for DMC identification [22]. The software supports analysis of data from whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS), reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS), and targeted bisulfite sequencing techniques including TruSeqEPIC, SureSelect and CpGiant. SMART2 incorporates specialized handling for replicate samples and includes functionality for missing value replacement using the median methylation value of other available samples from the same group [22]. For DMC detection, the tool employs entropy-based procedures to quantify methylation specificity for each CpG site, followed by statistical testing to identify significant differences across groups.

MethylKit represents a widely adopted GLM-based tool that models methylation counts using a binomial distribution and conducts statistical testing with likelihood ratio tests [17]. The tool accommodates multiple experimental designs through its flexible model specification but requires careful parameter tuning for overdispersion correction. MethylKit operates on methylation count data or preprocessed methylation percentage files and includes basic functionality for annotation and visualization, though these features are less comprehensive than those in integrated platforms like DiffMethylTools [17].

DSS (Dispersion Shrinkage for Sequencing) employs a Bayesian hierarchical framework to model methylation counts with a beta-binomial distribution, incorporating shrinkage estimation for overdispersion parameters to enhance stability with limited replicates [17]. This approach improves detection reliability in studies with small sample sizes, though it may exhibit conservative behavior in highly heterogeneous systems. DSS requires input data in BSseq object format or tab-delimited text files containing methylation counts.

Table 2: Input Requirements and Key Assumptions of DMC Detection Tools

| Tool | Input Data Format | Minimum Input Requirements | Key Statistical Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| DiffMethylTools | BED, BedGraph, BSseq objects | ≥ 2 samples per group | Models biological variability and technical noise |

| SMART2 | Methylation matrix (chrome, start, end, beta values) | CpG sites with coverage data | Assumes methylation specificity follows entropy patterns |

| methylKit | TAB-delimited, BSseq objects | ≥ 3 replicates recommended for each group | Binomial distribution of methylation counts |

| DSS | BSseq objects, custom text formats | ≥ 2 samples per condition | Beta-binomial distribution with shrinkage |

| BSmooth | BSseq objects | Low-coverage across many samples | Spatial correlation of nearby CpG sites |

Experimental Protocols for DMC Detection

Benchmarking Framework for Tool Performance Assessment

Robust evaluation of DMC detection tools requires implementation of a standardized benchmarking framework that assesses both sensitivity and specificity across diverse data types. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for comparative tool evaluation:

Experimental Design and Data Preparation: Begin by selecting appropriate benchmark datasets representing various sequencing technologies (e.g., WGBS, RRBS, targeted panels) and biological contexts [17]. Ideally, include both real datasets with validated DMCs and synthetic datasets with known ground truth. For synthetic data generation, utilize real methylation data as a starting methylome to preserve biological characteristics. Cluster CpG sites into regions with maximum gap of 100 base pairs, retaining only regions containing at least 20 CpG sites. Apply smoothing algorithms such as LOWESS (locally weighted scatterplot smoothing) to obtain baseline methylation profiles [17].

Simulation of Control and Case Conditions: Generate control methylomes by sampling methylation levels at individual CpG sites from a truncated normal distribution with mean equal to the local smoothed methylation level and standard deviation independently generated from a uniform distribution (e.g., ranging from 2 to 15) [17]. For case conditions, introduce structured methylation changes across the genome, with predetermined proportions of CpG sites assigned to different effect size categories (e.g., 40% minimal change, 30% ±5% difference, 10% ±10% difference, 10% ±15% difference, and remaining sites with larger differences of ±20%, ±30%, ±40%, and ±50%) [17].

Tool Execution and Parameter Optimization: Execute each DMC detection tool using multiple parameter configurations to assess sensitivity to settings. For tools employing statistical testing, apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction with standard thresholds (e.g., FDR < 0.05). Include coverage-based filtering appropriate for each dataset (e.g., minimum 5-10x coverage per CpG site) [6]. For tools supporting replication, utilize the built-in methods for handling biological replicates rather than pre-averaging methylation values.

Performance Metrics Calculation: Evaluate detection performance using standard metrics including sensitivity (recall), precision, F1-score, and area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC). Calculate these metrics across a range of methylation difference thresholds (e.g., absolute methylation difference ≥ 0.1, 0.2, 0.3) and statistical significance thresholds (e.g., FDR < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001) [17]. Assess computational efficiency through runtime and memory consumption measurements on standardized computing infrastructure.

Standardized Workflow for DMC Detection with SMART2

The following protocol details a standardized approach for DMC identification using SMART2, which supports comprehensive methylation analysis across multiple sample groups:

Input Data Preparation: Format input data as a methylation matrix where each row represents a CpG site and columns contain chromosomal coordinates (chrome, start, end) followed by methylation values (ranging from 0 for unmethylated to 1 for fully methylated) for all samples [22]. The methylation matrix can be generated from individual BED files using BEDTools unionbedg command with appropriate parameters. Sample names should follow the convention G11, G12, G21, G22, etc., where Gi represents group i. Missing values should be denoted with "-" characters.

Command Line Execution: Execute SMART2 with the DMC project type using the following command structure:

Where the parameters specify: -t DMC for DMC detection; -MR for missing value replacement threshold (0.5 indicates replacement when ≥50% of group samples have data); -AG for percentage of available groups required for CpG inclusion (0.8 = 80%); -PD for p-value threshold for DMC significance (0.05); and -AD for absolute mean methylation difference threshold (0.1 = 10%) [22].

Result Interpretation and Validation: The primary output file (7_DMC.txt) contains identified differentially methylated CpG sites with statistical metrics including methylation specificity, Euclidean distance, entropy values, and ANOVA p-values [22]. Perform validation through integration with orthogonal data sources such as gene expression profiles or functional enrichment analysis of genes associated with identified DMCs. For technical validation, select a subset of DMCs for confirmation using targeted bisulfite sequencing or methylation-sensitive PCR.

Figure 1: Standardized workflow for DMC detection analysis illustrating key stages from data preparation through experimental validation.

Critical Considerations for Robust DMC Detection

Impact of Sequencing Technologies on Detection Accuracy

The choice of sequencing technology significantly influences DMC detection accuracy due to fundamental differences in detection principles, coverage distributions, and technical artifacts. Bisulfite sequencing-based methods, including WGBS and RRBS, represent the current gold standard for DNA methylation assessment, providing single-nucleotide resolution with conversion rates typically exceeding 99% [5]. These methods chemically convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils while methylated cytosines remain protected, effectively transforming epigenetic information into sequence information [5]. However, bisulfite conversion introduces DNA fragmentation and reduces sequence complexity, complicating alignment and increasing potential for PCR artifacts.

Emerging long-read technologies from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) offer bisulfite-free methylation detection while overcoming limitations in repetitive regions that challenge short-read approaches [23]. Comparative analyses demonstrate high concordance between ONT and bisulfite sequencing data, with Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.868 for R10.4.1 chemistry and 0.839 for R9.4.1 chemistry relative to bisulfite sequencing [23]. However, chemistry-specific biases exist between ONT platforms, with cross-chemistry comparisons showing reduced correlation values (e.g., R9 WT against R10 KO correlates at 0.8432 versus 0.8612 for R9 WT against R9 KO) [23]. These technology-specific biases must be considered when designing studies and analyzing data, particularly for meta-analyses combining datasets from multiple platforms.

Quality Control and Preprocessing Requirements

Robust DMC detection necessitates implementation of rigorous quality control measures throughout the data generation and processing pipeline. The following QC checkpoints are essential for reliable results:

Sequencing Data Quality Assessment: Evaluate raw sequencing quality metrics including per-base quality scores, adapter contamination, and bisulfite conversion efficiency (using spike-in controls such as λ-bacteriophage DNA) [5]. For ONT data, assess raw current signal quality and basecalling accuracy. Filter low-quality reads and trim adapter sequences using specialized bisulfite-aware preprocessing tools.

Alignment and Methylation Calling: Align processed reads to reference genomes using bisulfite-aware aligners such as Bismark or BSMAP, optimizing parameters for specific sequencing technologies [5]. Calculate methylation percentages at each CpG site using count-based approaches (methylated versus unmethylated reads). Apply coverage-based filtering, typically requiring minimum 5-10x coverage per CpG site for confident methylation assessment [6].

Sample-Level QC and Normalization: Examine sample-level metrics including coverage distribution, average methylation levels, and correlation between replicates. Identify potential outliers through multidimensional scaling or principal component analysis. For large-scale studies, apply normalization procedures to correct for technical variation while preserving biological signals, selecting methods appropriate for specific technologies (e.g., subset quantile normalization for array data, global scaling for sequencing data).

Figure 2: Essential quality control workflow for DMC detection analysis from raw sequencing data through preprocessing stages.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DMC Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosine to uracil | Bisulfite treatment of genomic DNA for WGBS and RRBS |

| Methylated Lambda Phage DNA | Bisulfite conversion efficiency control | Spike-in control for quantification of conversion rates |

| DNA Methyltransferases | Enzymatic methylation for control experiments | Generation of positive controls for methylation detection |

| Targeted Bisulfite Sequencing Kits | Validation of identified DMCs | Amplification and sequencing of specific genomic regions |

| Oxford Nanopore Flow Cells | Long-read methylation detection | R10.4.1 flow cells for native DNA methylation detection |

| Quality Control Software | Assessment of data quality | FastQC, MultiQC for sequencing quality metrics |

| Alignment Tools | Mapping of bisulfite-converted reads | Bismark, BSMAP for BS-seq data; minimap2 for ONT data |

| Statistical Computing Environment | Data analysis and visualization | R/Bioconductor with packages like DSS, methylSig |

The rapidly evolving landscape of DMC detection tools offers researchers diverse methodological approaches, each with distinctive assumptions and requirements that significantly influence detection performance. This comparative overview highlights the critical importance of matching tool selection to experimental design, data characteristics, and biological questions. As methylation profiling technologies continue to advance, particularly with the maturation of long-read sequencing platforms, computational methods must similarly evolve to address new challenges and opportunities.

Future methodology development will likely focus on improved integration of multi-omics data, enhanced normalization approaches for cross-platform analyses, and machine learning approaches for prioritizing functionally relevant methylation alterations. Additionally, as single-cell methylation profiling becomes more accessible, specialized tools for handling the unique characteristics of sparse single-cell data will become increasingly important. By maintaining awareness of both the capabilities and limitations of available DMC detection tools, researchers can maximize the biological insights gained from their epigenomic investigations while ensuring rigorous and reproducible analysis.

Table 1: Core Beta-Binomial Tools for Differential Methylation Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Model/Feature | Handles Biological Replicates |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSS (Dispersion Shrinkage for Sequencing data) [24] [25] | DMC & DMR detection | Beta-binomial with genome-wide dispersion prior | Yes |

| MethylSig [25] | DMC & DMR detection | Beta-binomial with local smoothing | Yes |

| RADMeth (Regression Analysis of Differential Methylation) [24] [25] | DMC & DMR detection | Beta-binomial regression | Yes |

| MACAU (Binomial Mixed Model) [24] | DMC detection | Binomial Mixed Model (accounts for population structure) | Yes, including genetic relatedness |

The quest to understand the epigenetic basis of cellular regulation and disease has made the identification of differentially methylated cytosines (DMCs) a critical bioinformatics challenge. Cytosine methylation, particularly in CpG contexts, is a fundamental epigenetic mark involved in gene regulation, genomic imprinting, and cellular differentiation [26] [5]. Bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq), including whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS), provides quantitative methylation information at single-nucleotide resolution throughout the genome [27] [5]. These techniques exploit the differential sensitivity of methylated and unmethylated cytosines to sodium bisulfite conversion, which transforms unmethylated cytosines to uracils (read as thymines during sequencing) while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged [26] [5].

A fundamental characteristic of bisulfite sequencing data is its binomial nature: at each cytosine site, the data consists of the number of reads showing methylation (successes) and the total read coverage (trials) [27] [24]. However, biological and technical variability introduce over-dispersion—where the observed variation exceeds what the binomial distribution expects. This occurs because true methylation levels (pi) vary between biological replicates due to natural epigenetic variation and technical artifacts [27] [28]. Standard statistical tests that ignore this between-sample variability, or that convert counts to proportions, lack power and can produce misleading results [24] [25]. Beta-binomial models address this limitation by combining a binomial distribution (for sampling variability) with a beta distribution (for between-sample variability of methylation levels), providing a robust statistical framework for differential methylation analysis in complex experimental designs [27] [24].

Statistical Foundations of the Beta-Binomial Model

The beta-binomial model is a compound probability distribution that naturally handles over-dispersed count data. In the context of bisulfite sequencing, for a given cytosine site, the number of methylated reads (Mi) from sample *i* with total coverage *ni* is modeled in two stages [27]:

- Binomial Sampling: Conditional on the methylation level p_i, Mi ∼ Binomial(*pi, *n_i).

- Beta Distribution: The methylation level p_i itself varies across biological replicates following a Beta distribution, p_i ∼ Beta(α, β).

The parameters α and β of the Beta distribution are re-parameterized in terms of a mean methylation level π = α/(α+β) and a dispersion parameter γ = 1/(α+β+1). This leads to the following properties for the beta-binomial distribution [27]:

- E(Mi) = *niπ*

- Var(Mi) = *niπ(1-π)(1 + (n_i - 1)γ)*

The dispersion parameter γ quantifies the extra-binomial variation. When γ=0, the variance reduces to that of a binomial distribution. The larger the γ, the greater the over-dispersion between replicates. Beta-binomial regression extends this core model by allowing the mean methylation level π to be linked to a linear predictor of covariates (e.g., cell type, treatment) through a link function (e.g., logit), enabling the analysis of multifactor experiments [27] [29].

Tool-Specific Methodologies and Protocols

DSS (Dispersion Shrinkage for Sequencing Data)

Experimental Protocol for DMR Detection with DSS:

- Data Input Preparation: Prepare data as a matrix of methylated read counts and total read coverage counts for each CpG site and each sample. Data should be organized by experimental condition (e.g., case vs. control).

- Model Fitting: Use the

DMLfitfunction to estimate mean methylation levels and dispersion parameters for each condition. DSS employs a Bayesian shrinkage estimator for the dispersion parameter, borrowing information from across the entire genome to produce stable estimates even with small sample sizes [24] [25]. - Statistical Testing: Perform hypothesis testing for differential methylation between conditions using the

DMLtestfunction. This function computes test statistics and p-values for each CpG site based on the fitted beta-binomial models and the dispersion estimates. - DMR Calling: Utilize the

callDMRfunction to identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs). This function groups adjacent significant CpG sites into regions, using a threshold for the p-value difference and a minimum length requirement [25].

DSS is particularly noted for its ability to handle experiments with a small number of replicates through its robust dispersion shrinkage approach [25].

MethylSig

Experimental Protocol for DMR Detection with MethylSig:

- Data Input and Filtering: Input sorted BAM files or base-level coverage files. Filter CpG sites based on a minimum coverage threshold (e.g., at least 5 reads per site in each sample) to reduce false positives caused by low coverage [25].

- Local Information Smoothing: MethylSig improves parameter estimation for low-coverage sites by borrowing information from neighboring CpG sites. This local smoothing technique assumes that methylation levels are correlated within small genomic windows [25].

- Beta-Binomial Model Fitting: Fit a beta-binomial model at each CpG site. MethylSig estimates a separate dispersion parameter for each site or group of sites, in contrast to DSS's genome-wide shrinkage.

- Statistical Testing and Multiple Testing Correction: Test for significant differential methylation using a likelihood ratio test or a Wald test against the null hypothesis of no difference between groups. Apply multiple testing correction (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg) to control the False Discovery Rate (FDR).

MethylSig's use of local smoothing makes it powerful for detecting DMRs, especially in regions with sparse but coordinated methylation changes [25].

RADMeth (Regression Analysis of Differential Methylation)

Experimental Protocol for DMR Detection with RADMeth:

- Data Input: Prepare data as a matrix of methylated and total read counts, along with a design matrix specifying the experimental conditions and any additional covariates (e.g., batch effects, age).

- Beta-Binomial Regression: The core of RADMeth is a beta-binomial regression model that can directly incorporate continuous or categorical covariates into the differential methylation test [24] [25]. This is represented as: g(π) = Xβ, where g is a link function (e.g., logit), X is the design matrix, and β are the coefficients.

- Dispersion Modeling: RADMeth accounts for over-dispersion by including a dispersion parameter in the regression model.

- Significance Testing and DMR Calling: Perform regression-based hypothesis tests on the coefficients of interest. RADMeth then combines evidence from adjacent CpG sites using a weighted Z-test to call DMRs, where the weights are based on the coverage at each site [25].

RADMeth's regression framework is its key strength, allowing for the analysis of complex experimental designs beyond simple two-group comparisons [24].

Diagram 1: A simplified workflow illustrating the core analytical pathways for DSS, MethylSig, and RADMeth, highlighting their key methodological distinctions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools for Beta-Binomial Analysis

| Item Name | Type | Function/Description | Example/Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Bisulfite | Chemical | Converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, enabling methylation state discrimination [5]. | Sigma-Aldrich, Thermo Fisher |

| Unmethylated λ-DNA | Control | Spiked into reactions to empirically measure and confirm bisulfite conversion efficiency [5]. | Promega |

| CpG Island Reference | Bioinformatics | Genomic coordinates of CpG-rich regions for annotation and targeted analysis [5]. | UCSC Genome Browser |

| Bisulfite-Aware Aligner | Software | Aligns BS-seq reads to a reference genome, accounting for C-to-T conversions [26] [30]. | Bismark [26], BatMeth2 [30], BSMAP [26] |

| Methylation Caller | Software | Estimates methylation levels per cytosine from aligned BAM files [30]. | Bismark Methylation Extractor, BatMeth2 |

| Statistical Environment | Software | Platform for statistical analysis, visualization, and running specialized packages [25]. | R/Bioconductor |

| DSS / MethylSig / RADMeth | R Package | Implements the beta-binomial model for differential methylation testing [24] [25]. | Bioconductor |

Critical Analysis and Practical Considerations

Performance and Comparative Evaluation

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Beta-Binomial Tools

| Feature | DSS | MethylSig | RADMeth | MACAU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Strength | Stability with few replicates | Power for coordinated sparse changes | Complex designs & covariates | Accounts for population structure |

| Dispersion Handling | Genome-wide shrinkage | Local estimation & smoothing | Regression-based | Mixed model component |

| Covariate Adjustment | Limited | Limited | Yes (in regression model) | Yes (as fixed effects) |

| Smoothing Approach | No | Yes (local CpGs) | No (but uses weighted Z-test for DMRs) | No |

| Optimal Use Case | Two-group comparisons with low replication | Defining precise DMR boundaries | Multi-factor or batch-adjusted designs | Structured populations (e.g., EWAS) |

Independent evaluations of beta-binomial methods have shown that they provide a major advantage over non-replicate methods like Fisher's exact test by properly controlling for between-sample variability [25]. However, the performance of each tool can vary depending on the data structure. A key finding is that while these methods are powerful, no single tool uniformly dominates all others across all scenarios [25]. For instance, DSS's shrinkage estimator provides robustness with small sample sizes, while RADMeth's regression framework is unparalleled in studies requiring adjustment for confounders [24] [25].

Limitations and Advanced Modeling

A significant limitation of standard beta-binomial models is their inability to account for genetic relatedness or population structure among samples [24]. In studies of structured populations or where kinship exists, this can lead to spurious associations, as DNA methylation levels are often heritable [24]. To address this, the binomial mixed model (BMM) implemented in MACAU incorporates a random effect to model the covariance between individuals due to population structure [24]. MACAU has been demonstrated to provide well-calibrated p-values in the presence of population structure and can detect more true positive associations than beta-binomial models in such scenarios [24].

Furthermore, beta-binomial models face challenges with extremely low coverage sites and very small sample sizes (e.g., fewer than 3 per group), where parameter estimation becomes unreliable. Methods like MethylSig's local smoothing and DSS's global shrinkage are attempts to mitigate these issues, but careful data filtering and cautious interpretation remain essential [25].

Within the framework of a broader thesis on Differentially Methylated Cytosines (DMC) calling tools, this document delves into three sophisticated computational approaches designed for identifying Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs): metilene, BSmooth, and BiSeq. The accurate detection of DMRs is a critical prerequisite for characterizing epigenetic states linked to development, tumorigenesis, and systems biology [31]. While DMC callers focus on single cytosines, DMR tools like these aggregate information across multiple nearby CpG sites to identify broader, often more biologically meaningful, epigenetic patterns. These tools were developed to address the significant bottleneck in methylome analysis posed by the complexity and scale of data from whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) [31] [26]. This note details their underlying statistical models, provides structured performance comparisons, and outlines explicit protocols for their application in research and drug development.

The selection of an appropriate DMR detection tool depends heavily on the experimental design, data type, and specific biological question. The table below summarizes the core methodologies, key features, and optimal use cases for metilene, BSmooth, and BiSeq.

Table 1: Overview and Comparison of DMR Detection Tools

| Feature | metilene | BSmooth | BiSeq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Algorithm | Binary segmentation (CBS) combined with a two-dimensional Kolmogorov-Smirnov test [31]. | Local likelihood smoothing followed by a t-test accounting for biological variability [32]. | Beta-binomial regression model that smooths methylation levels within predefined regions [31] [26]. |

| Primary Approach | Non-parametric, model-free segmentation. | Smoothing-based, empirical Bayes. | Parametric, regression-based smoothing. |

| Key Strength | High speed and sensitivity; precise boundary detection; handles low-coverage data [31]. | Effectively accounts for biological variability; superior for low-coverage designs [32]. | Models biological variability explicitly through a random effect; provides well-calibrated error rates [31] [26]. |

| Optimal Data Type | WGBS, RRBS [31]. | WGBS, especially with biological replicates [32]. | RRBS, targeted bisulfite sequencing [31]. |

| Typical Output | Genomic coordinates of DMRs with p-values and methylation differences. | Smoothed methylation levels per sample and called DMRs. | DMRs with associated posterior probabilities or p-values. |