A Comprehensive Guide to Outlier Detection in RNA-Seq Analysis: Methods, Tools, and Best Practices

Outlier detection in RNA-Seq data is a critical quality control and discovery step for researchers in genomics and drug development.

A Comprehensive Guide to Outlier Detection in RNA-Seq Analysis: Methods, Tools, and Best Practices

Abstract

Outlier detection in RNA-Seq data is a critical quality control and discovery step for researchers in genomics and drug development. This article provides a complete overview of the field, from foundational concepts explaining why outliers occur and their impact on differential expression analysis, to a detailed examination of modern statistical and computational methods like OUTRIDER, OutSingle, and robust PCA. We offer a practical guide for implementing these algorithms, troubleshooting common issues, and validating results through benchmark comparisons. By synthesizing the latest methodologies, this resource empowers scientists to improve the reliability of their RNA-Seq data interpretation, enhance biomarker discovery, and advance precision medicine applications.

Understanding RNA-Seq Outliers: Why They Matter and Where They Come From

The identification of outliers in RNA-sequencing data represents a critical challenge in transcriptomic analysis, standing at the intersection of technical artifact detection and biological discovery. Traditionally treated as noise to be removed, extreme expression values are now recognized as potential signals of rare biological events, including pathogenic variants in Mendelian disorders or spontaneous transcriptional activation [1] [2]. This paradigm shift necessitates robust methodological frameworks that can distinguish technical artifacts from biologically significant outliers—a distinction vital for researchers and drug development professionals advancing precision medicine approaches for rare diseases and cancer [3] [4].

The fundamental challenge in outlier analysis resides in the confounding effects that can mask true biological signals. Technical variability, batch effects, and library preparation artifacts can create expression patterns that mimic biological outliers, while true pathological expressions may be obscured by these same confounders [1] [5]. This Application Note synthesizes current methodologies and protocols for outlier detection, emphasizing practical implementation within a broader thesis on RNA-seq analysis research.

Quantitative Landscape of RNA-Seq Outliers

Understanding the expected frequency and distribution of outliers provides crucial context for interpreting analytical results. The quantitative characteristics of outlier genes vary significantly across species, tissues, and experimental conditions.

Table 1: Prevalence of Outlier Genes Across Biological Systems

| Biological System | Sample Size | Outlier Threshold | Percentage of Outlier Genes | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Populations (Outbred) | 48 individuals (5 organs) | Q3 + 5 × IQR | ~3-10% (350-1350 genes) | Similar patterns across tissues; declining frequency with increasing threshold [2] |

| Human (GTEx) | 51 individuals (3-4 tissues) | Q3 + 5 × IQR | Comparable to mouse models | Conserved patterns across mammals; spontaneous over-expression [2] |

| Drosophila Species | 19-27 individuals | Q3 + 5 × IQR | Comparable patterns | Evolutionary conservation of outlier phenomenon [2] |

| Pediatric Cancer (CARE) | 11,427 tumor profiles | Expression > 2 standard deviations | Varies by cancer type | Identified targetable oncogenes in ultra-rare malignancies [3] |

The selection of outlier thresholds significantly impacts the number and biological interpretation of identified outliers. At k = 3 (corresponding to 4.7 standard deviations above the mean), approximately 3-10% of all genes exhibit extreme outlier expression in at least one individual across multiple datasets [2]. This percentage declines continuously with increasing stringency without a natural cutoff, necessitating careful threshold selection based on research objectives.

Table 2: Impact of Statistical Thresholds on Outlier Detection

| Threshold (k) | Standard Deviation Equivalence | Theoretical P-value | Percentage of Outlier Genes | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 2.7 σ | 0.0069 | Higher sensitivity | Exploratory analysis, high sensitivity required |

| 3.0 | 4.7 σ | 2.6 × 10⁻⁶ | ~3-10% | Standard analysis with multiple testing correction |

| 5.0 | 7.4 σ | 1.4 × 10⁻¹³ | More conservative | High-confidence calls, clinical applications [2] |

Methodological Frameworks for Outlier Detection

The OutSingle Algorithm for Confounder-Controlled Detection

The OutSingle method addresses a critical limitation in RNA-seq outlier detection: the confounding effects that can obscure true biological signals. This approach utilizes a two-step process that combines log-normal transformation with advanced confounder control [1].

Experimental Protocol: OutSingle Implementation

Step 1: Log-Normal Z-score Calculation

- Input: Raw count matrix (J genes × N samples)

- Transformation: Log-transform count data using the formula:

log(kji + 1)where kji represents the count for gene j in sample i - Normalization: Calculate gene-specific z-scores based on the log-transformed data

- Output: Z-score matrix representing deviation of each gene expression from its expected distribution [1]

Step 2: Confounder Control via Optimal Hard Threshold (OHT)

- Input: Z-score matrix from Step 1

- Decomposition: Perform Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) on the z-score matrix

- Noise Reduction: Apply OHT to identify and retain significant singular values

- Reconstruction: Reconstruct confounder-corrected z-score matrix using thresholded singular values

- Output: De-noised outlier scores for each gene in each sample [1]

Performance Characteristics:

- Execution Time: Near-instantaneous compared to previous methods

- Advantage: Does not require parameter initialization or convergence monitoring

- Benchmarking: Outperforms OUTRIDER on real biological datasets with confounding effects [1]

Transcriptome-Wide Splicing Outlier Analysis

Beyond expression-level outliers, splicing abnormalities represent another critical dimension of transcriptional dysregulation. The FRASER/FRASER2 framework enables detection of aberrant splicing patterns across the transcriptome, particularly valuable for identifying spliceosome pathologies [4] [6].

Experimental Protocol: Splicing Outlier Detection

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- Starting Material: Whole blood collected in PAXgene RNA tubes

- RNA Quality: RIN > 7-8 for all samples (assessed by Bioanalyzer or TapeStation)

- Library Preparation: Illumina TrueSeq Stranded mRNA or Tecan Universal Plus mRNA-seq with NuQUANT

- Depletion: Remove globin and ribosomal RNAs using AnyDeplete module

- Sequencing: 2×150bp paired-end reads on Illumina NovaSeq or NextSeq 550 platforms

- Quality Threshold: >80% bases with Q30 score [6]

Computational Analysis

- Input: FASTQ files from RNA-seq of whole blood

- Splicing Metric Calculation: Compute intron retention scores using FRASER and FRASER2

- Outlier Detection: Identify samples with excess intron retention outliers in minor intron-containing genes (MIGs)

- Pattern Recognition: Focus on transcriptome-wide signatures suggesting spliceosome dysfunction

- Validation: Sanger sequencing of candidate variants in minor spliceosome snRNAs (RNU4ATAC, RNU6ATAC) [4]

Clinical Utility: This approach successfully identified five individuals with excess intron retention outliers in MIGs from a cohort of 390 rare disease patients, all harboring rare biallelic variants in minor spliceosome components [4].

Comparative Analysis of RNA Expression (CARE) for Oncology

The CARE framework exemplifies the clinical translation of outlier analysis for precision oncology applications, particularly for rare pediatric cancers with limited treatment options [3].

Experimental Protocol: CARE Analysis

Comparator Cohort Construction

- Data Aggregation: Compile 11,427 tumor RNA-seq profiles from public repositories

- Uniform Processing: Implement standardized bioinformatic processing across all samples

- Cohort Definition: Create personalized comparator cohorts based on:

- Same diagnosis matches

- Molecularly similar profiles (Spearman correlation)

- First and second-degree molecular neighbors

- Diseases represented in most similar datasets [3]

Outlier Identification and Clinical Annotation

- Expression Comparison: Compute expression z-scores relative to personalized cohorts

- Thresholding: Identify overexpression outliers exceeding cohort-defined thresholds

- Pathway Analysis: Detect enriched oncogenic pathways among outlier genes

- Target Nomination: Map outlier genes to potentially targetable pathways

- IHC Validation: Confirm protein-level overexpression (e.g., CDK4 staining) [3]

Clinical Implementation: In a case study of myoepithelial carcinoma, CARE analysis identified CCND2 overexpression and FGFR/PDGF pathway activation, leading to successful treatment with ribociclib after pazopanib failure [3].

Visualizing Analytical Workflows

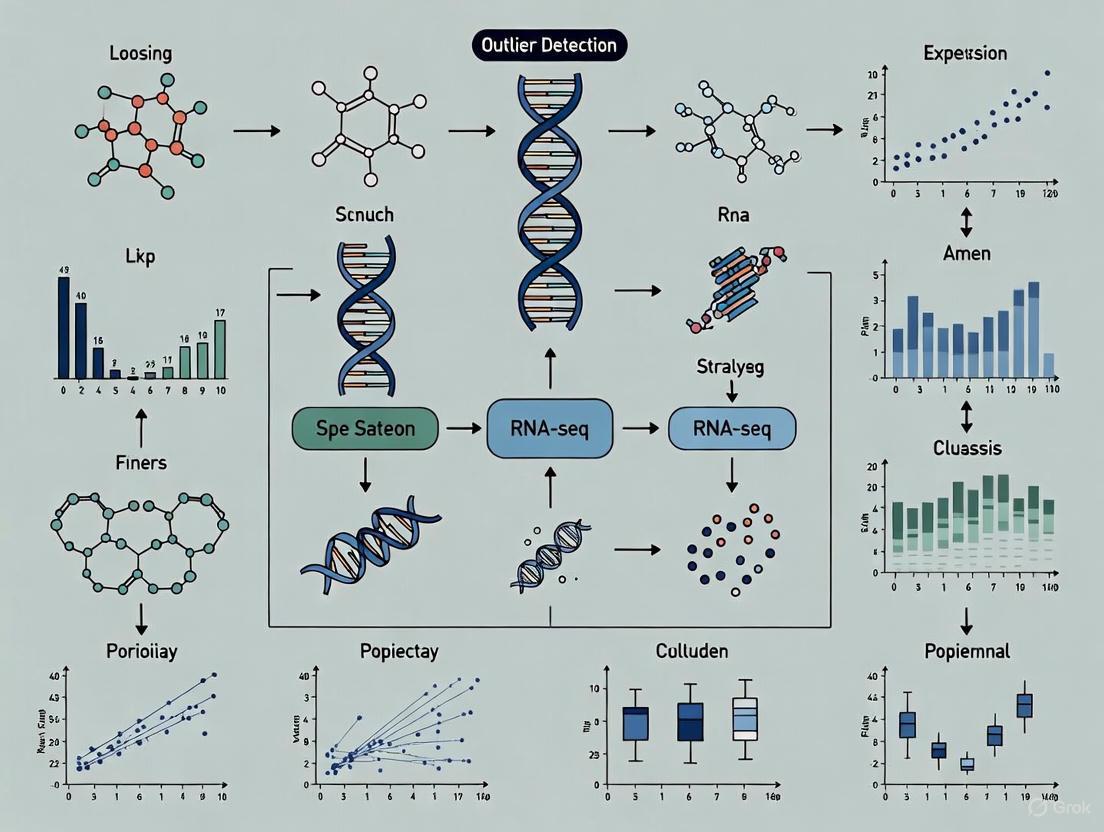

The following diagram illustrates the core decision process for interpreting and validating RNA-seq outliers, integrating both technical and biological considerations:

Diagram 1: A framework for distinguishing technical artifacts from biologically significant outliers in RNA-seq data analysis.

The experimental workflow for outlier detection and validation involves multiple coordinated steps from initial sequencing to biological interpretation:

Diagram 2: End-to-end experimental workflow for RNA-seq outlier detection studies.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful implementation of RNA-seq outlier detection requires specific research reagents and computational tools optimized for various aspects of the analytical pipeline.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Outlier Detection Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Tool | Function in Outlier Analysis | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization | PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes | Preserves RNA integrity in whole blood samples | Maintains RIN >7 for reliable outlier detection [6] |

| rRNA Depletion | Illumina Ribo-Zero Plus rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes ribosomal RNA to enrich mRNA | Improves detection of low-abundance transcripts [6] |

| Library Preparation | Tecan Universal Plus mRNA-seq with NuQUANT | Prepares sequencing libraries with UMI incorporation | Reduces PCR duplicates, improves quantification accuracy [6] |

| Outlier Detection Algorithms | OutSingle [1] | Identifies expression outliers with confounder control | SVD/OHT-based, near-instantaneous execution |

| Splicing Outlier Tools | FRASER/FRASER2 [4] | Detects aberrant splicing patterns | Identifies intron retention outliers in rare diseases |

| Comparative Analysis | CARE Framework [3] | Identifies overexpression outliers in cancer | Uses large comparator cohorts (11,427 tumors) |

The distinction between technical artifacts and biologically significant outliers in RNA-seq data represents a critical challenge with profound implications for research and clinical applications. Methodologies such as OutSingle, FRASER/FRASER2, and the CARE framework provide robust approaches for confounder-controlled detection of meaningful transcriptional outliers. As these protocols demonstrate, rigorous experimental design, appropriate statistical thresholds, and validation through orthogonal methods are essential components for accurate outlier interpretation. The growing evidence for biological significance of extreme expression values—from spontaneous transcriptional activation in model organisms to pathological expression in rare diseases and cancer—supports the continued refinement of these analytical approaches for precision medicine applications.

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, outliers are data points that deviate significantly from the expected expression or splicing pattern of a gene. These outliers can stem from diverse sources, broadly categorized into biological outliers, which reveal genuine and often rare physiological or technical effects, and technical artifacts introduced during the library preparation and sequencing workflow. Historically, samples with numerous outliers were frequently excluded from analyses under the assumption that technical noise was the primary driver [7] [2]. However, emerging research demonstrates that these outliers can harbor critical biological insights, including the identification of rare genetic disorders and novel regulatory mechanisms [7] [2]. This document outlines the major sources of these outliers, providing a framework for their identification and interpretation within transcriptomic studies.

Biological outliers arise from genuine, often sporadic, changes in a cell's transcriptome. Dismissing them as noise can lead to a loss of significant biological discovery.

Genetic Variants Affecting Splicing

Rare genetic variants can cause transcriptome-wide aberrant splicing patterns, a hallmark of "spliceopathies." Pathogenic variants in components of the major or minor spliceosome can lead to hundreds of splicing outliers [7] [6].

- Minor Spliceosome Defects: The minor spliceosome, which removes only ~0.5% of all introns (approximately 800 minor introns), is particularly vulnerable. Bi-allelic pathogenic variants in minor spliceosome small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) like RNU4ATAC and RNU6ATAC cause a specific and detectable pattern: excess intron retention outliers in minor intron-containing genes (MIGs) [7] [6]. This pattern has been used to diagnose rare diseases such as RNU4atac-opathy [7].

- Major Spliceosome Defects: Variants in genes encoding proteins of the major spliceosome (e.g., SNRNP40, PPIL1) also cause distinct outlier signatures. For instance, PPIL1 variants lead to the retention of short, high-GC-content introns, while SF3B1 variants are associated with the retention of large introns (>1kb) [6].

Spontaneous and Non-Inherited Expression Variation

Some outlier expression appears to be a biological reality of complex regulatory networks, not attributable to common genetic variants.

- Sporadic Over-expression: Analyses across multiple species (mice, humans, Drosophila) show that different individuals can harbor vastly different numbers of over-expression outlier genes. Longitudinal and family studies in mice indicate that most of this extreme over-expression is not inherited but spontaneously generated [2].

- Edge of Chaos Effect: These outlier patterns are consistent across tissues and species, suggesting they may reflect "edge of chaos" effects within gene regulatory networks. These are systems of non-linear interactions and feedback loops that can produce sporadic, co-regulated bursts of transcription in different individuals [2].

Table 1: Characteristics of Biological Outliers

| Source Category | Specific Mechanism | Key Genes/Pathways | Molecular Signature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spliceopathies | Minor spliceosome dysfunction | RNU4ATAC, RNU6ATAC | Excess intron retention in minor intron-containing genes (MIGs) [7] [6] |

| Spliceopathies | Major spliceosome dysfunction | PPIL1, SF3B1, SNRNP40 | Retention of short, high-GC introns; retention of large introns (>1kb); hundreds of intron retention events [7] [6] |

| Regulatory Networks | Spontaneous co-activation | Prolactin, Growth hormone | Co-regulatory modules show extreme over-expression in single or few individuals, not inherited [2] |

Technical Artifacts and Workflow-Related Outliers

Technical artifacts are introduced during the experimental workflow, from sample preparation to sequencing. Vigilant quality control is required to identify and mitigate these sources.

Library Preparation

This initial stage is a major source of bias and outliers.

- RNA Quality: The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is critical. Samples with RIN < 7 are often excluded from analysis, as RNA degradation leads to biased representation of transcripts and an increase in technical outliers [6].

- rRNA and Globin Depletion: Inefficient removal of highly abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) or, in blood samples, globin mRNAs, can consume a disproportionate share of sequencing reads. This reduces the library complexity and can mask the detection of true, lowly expressed transcripts, creating expression outliers [6].

- cDNA Synthesis and PCR Amplification: Biases during reverse transcription and the use of too many cycles during PCR amplification can lead to duplicated reads and over-representation of certain fragments, skewing expression estimates [8].

Sequencing and Data Preprocessing

Errors during the sequencing run and subsequent data handling can generate artifacts.

- Sequencing Depth: Inadequate sequencing depth (e.g., below 20-30 million reads per sample for standard differential expression) reduces the power to detect true expression differences and increases the variance of low-count genes, making them appear as outliers [8].

- Adapter Contamination and Low-Quality Bases: Leftover adapter sequences and bases with low Phred quality scores, if not properly trimmed, can prevent reads from mapping correctly or lead to misalignment, creating false splicing or expression outliers [8].

- Misalignment and Multi-Mapped Reads: Reads that originate from repetitive regions, paralogous genes, or multiple splice junctions can map to an incorrect location in the reference genome. If not filtered out, these reads artificially inflate the expression of the incorrect gene [8].

Diagram 1: Technical workflow of RNA-seq and potential sources of outliers at each stage.

Experimental Protocols for Outlier Detection and Validation

Transcriptome-Wide Splicing Outlier Analysis

This protocol is designed to identify individuals with rare spliceopathies by looking for global patterns of aberrant splicing [7] [6].

- RNA-Seq and Preprocessing: Perform RNA sequencing on whole blood or other clinically accessible tissues. Align reads to a reference genome using a splice-aware aligner like STAR [8] [6].

- Splicing Quantification and Outlier Callling: Use specialized outlier detection algorithms such as FRASER or FRASER2 to identify aberrant splicing events at the intron level across the entire transcriptome [7] [6].

- Pattern Recognition: Examine the results for an excess of a specific type of splicing outlier. For example, a significant enrichment of intron retention events in minor intron-containing genes (MIGs) is a strong indicator of a minor spliceosome defect [7].

- Genetic Validation: In individuals with a clear outlier signature, perform targeted analysis of genome or exome sequencing data to identify rare variants in spliceosome components (e.g., RNU4ATAC, RNU6ATAC) [7].

Inhibition of Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD) to Reveal Splice Defects

NMD can degrade transcripts with premature termination codons, masking the presence of aberrant splicing. This protocol uses cycloheximide (CHX) to inhibit NMD and reveal these hidden events [9].

- Cell Culture and Treatment: Culture peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs). Split the culture and treat one aliquot with CHX (e.g., 100 µg/mL for 4-6 hours) to inhibit NMD. Leave an untreated aliquot as a control [9].

- RNA Extraction and Library Prep: Extract total RNA from both treated and untreated cells using a standard method (e.g., Qubit HS RNA kit, Bioanalyzer for RIN). Ensure RIN > 7. Prepare RNA-seq libraries, ideally with protocols that retain strand information and use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) [9] [6].

- Validation of NMD Inhibition: Use an internal control to confirm NMD inhibition. Monitor the expression of the NMD-sensitive transcript of SRSF2, which should show increased expression in CHX-treated samples compared to untreated controls [9].

- Comparative Analysis: Compare RNA-seq data from CHX-treated and untreated samples. The treated sample will often reveal aberrant splice variants that were degraded and thus absent in the untreated sample, allowing for the confirmation of splicing-altering variants [9].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Outlier Analysis

| Category | Reagent/Tool | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | FRASER / FRASER2 [7] | Identifies splicing outliers from RNA-seq data in a transcriptome-wide manner. |

| Computational Tools | STAR [8] | Splice-aware aligner for accurate mapping of RNA-seq reads. |

| Computational Tools | FastQC / MultiQC [8] | Performs initial quality control on raw and processed sequencing data. |

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Cycloheximide (CHX) [9] | Inhibits nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) to stabilize aberrant transcripts for detection. |

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Paxgene RNA Tubes [6] | Preserves RNA in whole blood samples for transport and storage. |

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Tecan Universal Plus / Illumina Stranded Prep [6] | Library preparation kits for constructing RNA-seq libraries, often with globin/rRNA depletion. |

Diagram 2: A decision workflow for analyzing and validating outliers from RNA-seq data.

The Critical Impact of Outliers on Differential Expression Analysis and Biomarker Discovery

In transcriptomic analysis, differential expression analysis serves as a foundational technique for identifying genes with significant expression changes between conditions. Traditional methods, predominantly based on comparisons of mean expression values (e.g., Student's t-statistic), perform effectively when expression changes homogeneously across sample groups [10]. However, in complex biological contexts such as cancer heterogeneity and rare genetic diseases, informative expression changes often occur only in a subset of samples, manifesting as statistical outliers that can be overlooked by mean-based approaches [10] [11]. The growing recognition of this limitation has spurred the development of specialized outlier-based methods to detect these atypical expression patterns, thereby enhancing biomarker discovery and diagnostic yields in precision medicine [11] [9].

Outlier-Based Methodologies in Transcriptomics

Conceptual Foundation and Key Methods

Outlier analysis in transcriptomics is predicated on the concept that biologically significant expression changes may not affect all samples uniformly. An outlier, defined as "an observation which deviates so much from the other observations as to arouse suspicions that it was generated by a different mechanism," can reveal crucial insights when systematically investigated [12]. In biomedical research, outliers may stem from various root causes, including errors, faults, natural deviations, or—most importantly for discovery—novelty-based mechanisms that represent previously uncharacterized biological phenomena [12].

Several statistical frameworks have been developed specifically for outlier detection in gene expression studies:

- Cancer Outlier Profile Analysis (COPA): Identifies genes with significant overexpression in a subset of samples by calculating robust measures of central tendency and dispersion, then flagging extreme values in the disease group [10].

- Outlier Sum (OS): Computes scores based on extreme values in the non-reference set relative to the reference distribution, effectively capturing outliers in one or both distribution tails [10].

- Bayesian Outlier Detection: Employs consensus background distributions derived from all available data to quantify overexpression in individual samples without requiring manual selection of comparison sets, making it particularly valuable for precision medicine applications [13].

When to Use Outlier-Based Approaches

Outlier-based methods demonstrate particular utility in specific biological contexts and data patterns:

Table 1: Scenarios Favoring Outlier-Based Differential Expression Analysis

| Scenario | Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Disease Heterogeneity | Only a subset of disease samples exhibits altered expression for a particular gene | Cancer subtypes with distinct oncogene activation patterns [10] |

| Rare Genetic Disorders | Causal variants with trans-acting effects on splicing transcriptome-wide | Minor spliceopathies caused by variants in minor spliceosome components [11] |

| Tissue-Specific Effects | Extreme expression patterns manifest in only one organ or tissue type | Sporadic over-expression observed in single organs of human and mouse models [2] |

| Composite Phenotypes | Samples with misidentified or mixed tissue origins | Cancer samples with ambiguous or composite tissue phenotypes [13] |

Simulation studies reveal that the performance advantage of outlier-based methods over mean-based approaches becomes pronounced when differential expression is strongly concentrated in the distribution tails. For sample sizes and effect sizes typical in proteomics and transcriptomics studies, the outlier pattern must be strong for these methods to provide meaningful benefits [10].

Quantitative Assessment of Outlier Impact

Prevalence and Patterns of Expression Outliers

Recent large-scale transcriptomic studies have quantified the prevalence and characteristics of extreme expression outliers across diverse biological systems:

Table 2: Prevalence of Extreme Expression Outliers Across Species and Tissues

| Dataset | Species | Tissues | Extreme Outlier Threshold | Genes with Outliers | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outbred Mice | M. m. domesticus | 5 organs | Q3 + 5 × IQR | 3-10% of genes (k=3) | Some individuals show extreme outlier numbers in only one organ [2] |

| GTEx Human | H. sapiens | Multiple tissues | Q3 + 5 × IQR | Comparable patterns | Outlier genes occur in co-regulatory modules, some corresponding to known pathways [2] |

| Drosophila | D. melanogaster, D. simulans | Head, trunk, whole fly | Q3 + 5 × IQR | Comparable patterns | Patterns consistent across evolutionarily divergent species [2] |

| Rare Disease | H. sapiens | PBMCs | Statistical outliers | Diagnostic in 6/46 individuals | Identified splicing defects in 6 of 9 individuals with splice variants [9] |

The biological significance of these outliers is underscored by their non-random distribution. Studies in mouse models demonstrate that extreme overexpression is typically not inherited but appears sporadically, suggesting these patterns may reflect edge of chaos effects inherent in complex gene regulatory networks with non-linear interactions and feedback loops [2].

Diagnostic Utility in Rare Diseases

In clinical diagnostics, transcriptome-wide outlier analysis has demonstrated significant value for identifying rare genetic disorders that evade detection by standard genomic approaches:

- In a study of 385 individuals from rare disease consortia, outlier analysis identified five individuals with excess intron retention outliers in minor intron-containing genes, all harboring rare, bi-allelic variants in minor spliceosome components ( [11]).

- Implementation of a minimally invasive RNA-seq protocol using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) enabled diagnostic resolution in six of nine individuals with splice variants, allowing reclassification of seven variants of uncertain significance [9].

- Global outlier analysis using methods like FRASER and OUTRIDER supported findings but did not yield new diagnoses beyond targeted approaches, suggesting complementary roles for hypothesis-driven and exploratory methods [9].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Transcriptome-Wide Outlier Analysis for Rare Disorder Diagnosis

Diagram 1: Rare Disorder Diagnostic Workflow

Protocol Steps:

Sample Preparation and RNA Sequencing

- Collect peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients and relevant family members

- Process samples with and without cycloheximide treatment to inhibit nonsense-mediated decay (NMD)

- Perform RNA sequencing using standard library preparation protocols [9]

Bioinformatic Processing

- Quality control: Assess sequence quality, adapter contamination, and potential sample swaps

- Read alignment and transcript quantification using standardized pipelines

- Normalization to account for technical variability (e.g., TPM, CPM) [2]

Outlier Detection

- Apply multiple outlier detection algorithms:

- FRASER/FRASER2: For detecting splicing outliers

- OUTRIDER: For identifying expression outliers

- Calculate expression thresholds using robust statistical measures (e.g., Q3 + 5 × IQR) [2]

- Focus on intron retention events in minor intron-containing genes [11]

- Apply multiple outlier detection algorithms:

Variant Interpretation and Validation

- Correlate outlier findings with genomic variants from exome or genome sequencing

- Perform functional validation of suspected splice variants

- Reclassify variants of uncertain significance based on transcriptomic evidence [9]

Diagnostic Decision Framework for Outlier Analysis

Diagram 2: Outlier Analysis Integration Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Outlier Analysis in Transcriptomics

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) | Clinically accessible tissue for transcriptomics | ~80% of intellectual disability/epilepsy panel genes expressed; minimally invasive [9] |

| NMD Inhibition | Cycloheximide (CHX) | Inhibits nonsense-mediated decay to detect unstable transcripts | More effective than puromycin in PBMCs; use SRSF2 transcripts as internal control [9] |

| Computational Tools | FRASER/FRASER2 | Detects splicing outliers from RNA-seq data | Identifies aberrant splicing patterns; effective for splice variant interpretation [11] [9] |

| Computational Tools | OUTRIDER | Identifies expression outliers across samples | Useful for detecting aberrant expression patterns; requires appropriate normalization [9] |

| Statistical Framework | Bayesian Outlier Detection | Quantifies overexpression in individual samples | Uses consensus background distributions; does not require manually selected comparison sets [13] |

| Quality Control | SRSF2 NMD-sensitive transcripts | Endogenous control for NMD inhibition efficacy | Monitors effectiveness of CHX treatment; essential for quality assessment [9] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The integration of outlier analysis into transcriptomic workflows represents a paradigm shift in differential expression analysis, moving beyond mean-centered comparisons to embrace biological heterogeneity. The critical impact of this approach is evidenced by its growing diagnostic utility in rare diseases and its ability to reveal novel biological mechanisms that operate in subsets of samples or individuals [11] [9] [2].

Methodologically, future advances will likely focus on multi-optic integration, combining transcriptomic outliers with genomic, proteomic, and clinical data to distinguish functional outliers from technical artifacts. Similarly, temporal outlier analysis incorporating longitudinal sampling may help distinguish sporadic from persistent outlier expression, with implications for understanding disease dynamics and treatment response [2].

From a practical perspective, current evidence supports a hierarchical diagnostic approach that begins with targeted analysis of specific candidate variants but incorporates transcriptome-wide outlier analysis when initial tests are inconclusive. This balanced approach maximizes diagnostic yield while managing computational and interpretive complexity [9].

As transcriptomic technologies become increasingly accessible and analytical methods more sophisticated, outlier-based approaches will undoubtedly assume an increasingly central role in both basic research and clinical diagnostics, ultimately advancing biomarker discovery and personalized therapeutic development.

Connecting Outlier Detection to Rare Disease Research and Precision Medicine

Outlier detection has emerged as a powerful computational paradigm in the analysis of high-throughput biological data, particularly for diagnosing rare genetic diseases where traditional methods often fall short. This approach identifies unusual observations in genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data that deviate significantly from normal patterns—deviations that frequently harbor pathogenic significance. By framing clinical discovery as an outlier detection problem, researchers can systematically identify individuals with aberrant molecular phenotypes that might otherwise escape notice through standard variant-filtering approaches [12]. The integration of outlier detection into RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis represents a particularly promising advancement, enabling the identification of aberrant gene expression and splicing events across the entire transcriptome. This transcriptome-wide outlier approach has demonstrated remarkable potential for increasing diagnostic yields in rare diseases, providing functional evidence to interpret variants of uncertain significance (VUS) and uncovering novel disease mechanisms [11] [14].

Quantitative Evidence from Recent Studies

Recent large-scale studies have generated compelling quantitative evidence supporting the clinical utility of outlier detection in RNA-seq data for rare disease diagnosis. The following table summarizes key findings from major research initiatives:

Table 1: Diagnostic Yield of Outlier Detection in Rare Disease Cohorts

| Study / Cohort | Cohort Size | Previous Diagnostic Method | Outlier Detection Method | Additional Diagnostic Yield | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100,000 Genomes Project [15] | 4,400 individuals | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | OUTRIDER (expression), LeafCutterMD (splicing) via DROP | Potential to diagnose ~25% of previously undiagnosed | ~5.4 expression and ~5.3 splicing outliers per person; ~0.2 relevant outliers after gene panel filtering |

| Neurodevelopmental Disorders (NDDs) [14] | 34 patients | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | DROP (RNA) + PROTRIDER (proteomics) | 32.4% (11/34 patients) diagnosed | Multi-omics guided exome reanalysis; 5 diagnoses directly from RNA/protein outliers |

| Minor Spliceopathies [11] | 385 individuals from GREGoR/UDN | Standard genomic analyses | FRASER/FRASER2 (splicing) | 5 individuals with rare, bi-allelic variants in minor spliceosome snRNAs | Identified excess intron retention in Minor Intron-containing Genes (MIGs) |

The quantitative evidence demonstrates that RNA-seq outlier analysis consistently provides substantial incremental diagnostic yield beyond DNA-based sequencing alone. The approach is particularly valuable for resolving variants of uncertain significance (VUS), which contribute to 18-28% of genetically undiagnosed cases [14]. By providing functional evidence at the transcript level, outlier detection helps reclassify these ambiguous variants, directly addressing one of the most significant challenges in rare disease genomics.

Experimental Protocols for Outlier Detection

Protocol 1: Transcriptome-Wide Splicing Outlier Analysis for Spliceopathy Detection

This protocol details the methodology for identifying individuals with splicing defects, particularly in minor spliceosome components, using the FRASER/FRASER2 framework [11].

- Sample Requirements: Whole blood RNA-seq data from patients with undiagnosed rare diseases and matched controls.

- Quality Control: Assess RNA integrity (RIN > 7), sequencing depth (>50 million reads), and alignment rates.

- Splicing Quantification: Process RNA-seq data through the DROP pipeline to calculate splice junctions and intron retention levels.

- Outlier Detection: Apply FRASER/FRASER2 to identify significant splicing outliers per sample. The model employs a denoising autoencoder to control for technical confounders and biological covariates.

- Pattern Recognition: Examine transcriptome-wide patterns, specifically focusing on excess intron retention outliers in Minor Intron-containing Genes (MIGs), which account for only 0.5% of human introns.

- Variant Correlation: Correlate splicing outlier signatures with rare, bi-allelic variants in minor spliceosome genes (e.g., RNU4ATAC, RNU6ATAC).

- Validation: Confirm suspected spliceosomal variants through orthogonal methods such as Sanger sequencing.

Protocol 2: Multi-Omics Integration for Neurodevelopmental Disorder Diagnosis

This protocol describes a comprehensive workflow integrating proteomics with RNA-seq to resolve undiagnosed Neurodevelopmental Disorder (NDD) cases [14].

- Sample Preparation: Collect patient-derived skin fibroblasts for RNA and protein extraction. Include control samples (e.g., in-house and from repositories like GTEx).

- Data Generation:

- RNA-seq: Perform standard RNA sequencing (e.g., Illumina). Target >30 million reads per sample.

- Proteomics: Conduct quantitative liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) proteomics.

- Outlier Analysis:

- RNA Level: Process data through the DROP pipeline, which integrates:

- OUTRIDER: For detecting aberrant expression (AE) outliers.

- FRASER: For detecting aberrant splicing (AS) outliers.

- Monoallelic Expression (MAE): For detecting allelic imbalance.

- Protein Level: Analyze proteomics data with PROTRIDER to identify aberrant protein expression outliers.

- RNA Level: Process data through the DROP pipeline, which integrates:

- Data Integration and Prioritization:

- Filter all outlier events (AE, AS, MAE, protein) for genes associated with Mendelian disease (e.g., OMIM genes).

- Integrate the prioritized outlier list with reanalyzed exome data.

- Manually curate variants based on ACMG/AMP guidelines, incorporating functional evidence from RNA and protein outliers.

- Interpretation: Classify variants as pathogenic or likely pathogenic based on combined genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic evidence.

Protocol 3: The OutSingle Algorithm for Confounder-Resistant Outlier Detection

This protocol outlines the use of the OutSingle tool, a rapid method for detecting outliers in RNA-seq gene expression data that is robust to confounding effects [1].

- Input Data: A J × N matrix of RNA-seq counts, where J is the number of genes and N is the number of samples.

- Step 1: Log-Normal Z-score Calculation:

- Log-transform the count data (e.g., log2(counts + 1)).

- For each gene, calculate Z-scores across samples based on the log-normal distribution assumption.

- Step 2: Confounder Control via SVD and Optimal Hard Threshold (OHT):

- Perform Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) on the Z-score matrix.

- Apply the Gavish-Donoho Optimal Hard Threshold (OHT) method to denoise the matrix by discarding non-significant singular values.

- Outlier Identification: Genes with absolute adjusted Z-scores beyond a defined threshold (e.g., |Z| > 3) in a given sample are flagged as outliers.

- Artificial Outlier Injection (Optional for Benchmarking): The model can be run in reverse to inject artificial outliers masked by confounders, enabling method validation and power calculations.

Visualizing Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Multi-Omics Outlier Detection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated multi-omics workflow for diagnosing rare neurological diseases, as implemented in recent studies [14].

Diagram 1: Multi-omics workflow for rare disease diagnosis.

Minor Spliceosome Dysfunction Pathway

This diagram outlines the biological pathway and analytical process connecting genetic variants in minor spliceosome components to disease, as identified through transcriptome-wide outlier analysis [11].

Diagram 2: Pathway from genetic variant to disease diagnosis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of outlier detection in a research or clinical setting requires specific computational tools and analytical frameworks. The following table catalogs key resources.

Table 2: Essential Tools and Resources for RNA-seq Outlier Detection

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DROP [14] [15] | Computational Pipeline | Modular workflow for RNA-seq outlier detection (AE, AS, MAE). | Comprehensive RNA analysis in rare disease cohorts. |

| OUTRIDER [1] [14] [15] | Algorithm / R Package | Detects aberrant gene expression outliers using autoencoders. | Identifying over/underexpressed genes in patient samples. |

| FRASER/FRASER2 [11] [14] | Algorithm / R Package | Detects aberrant splicing outliers from RNA-seq data. | Finding mis-splicing events in spliceopathies and other disorders. |

| PROTRIDER [14] | Computational Pipeline | Detects aberrant protein expression outliers from proteomics data. | Multi-omics integration for variants affecting protein stability. |

| OutSingle [1] | Algorithm | Rapid outlier detection using SVD and Optimal Hard Threshold. | Fast confounder-controlled analysis on gene expression counts. |

| LeafCutterMD [15] | Computational Tool | Identifies splicing outliers from RNA-seq data. | Splicing analysis in large cohorts (e.g., 100,000 Genomes). |

The integration of outlier detection methodologies into RNA-seq analysis represents a transformative advancement for rare disease research and precision medicine. By systematically identifying aberrant molecular phenotypes that elude conventional DNA-based analyses, these approaches significantly increase diagnostic yields—by 15-32% in recent studies—and provide a functional framework for interpreting the growing number of variants of uncertain significance. As the field progresses, the combination of transcriptomic, proteomic, and genomic data within unified outlier detection frameworks promises to further accelerate discovery, refine diagnostic precision, and ultimately deliver answers to an increasing number of patients and families affected by rare disorders.

The analysis of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data presents unique statistical challenges that must be adequately addressed to draw valid biological conclusions. Three fundamental concepts—confounding factors, overdispersion, and appropriate statistical distributions—form the bedrock of robust differential expression analysis. Confounding variables are unmeasured or uncontrolled factors that can unintentionally affect study outcomes, leading to spurious associations if not properly managed [16]. In RNA-seq data, overdispersion represents the empirical phenomenon where the variance of read counts exceeds the mean, violating the assumptions of simpler statistical models [17]. The choice of statistical distribution for modeling count data directly impacts the accuracy of differential expression testing and outlier detection [18]. Together, these concepts influence experimental design, analytical approaches, and interpretation of transcriptomic studies, particularly in the context of outlier detection methods for RNA-seq analysis.

Core Conceptual Foundations

Confounding Factors in Transcriptomics

A confounding variable is defined as an unmeasured factor that may unintentionally affect the outcome of a research study by creating spurious associations between variables [16]. In experimental design, independent variables represent manipulated conditions (e.g., genotype, treatment), while dependent variables represent measured outcomes (e.g., gene expression levels). Confounders can affect both independent and dependent variables, potentially reversing, eliminating, or obscuring true effects [16].

In RNA-seq experiments, confounding can occur when nuisance variables (factors not of direct interest) become associated with the primary factor under investigation. For example, if all knockout mouse samples are harvested in the morning while wild-type controls are harvested in the afternoon, time of collection becomes a confounding factor whose effects cannot be separated from the genetic effect [19]. Additional examples include having different laboratory technicians process different experimental groups, or using samples with systematically different RNA quality between conditions [19].

Overdispersion in Count Data

Overdispersion refers to the characteristic of RNA-seq data where the variance of read counts is larger than the mean, a phenomenon that contradicts the assumptions of traditional Poisson models [17]. This extra-Poisson variability arises from multiple sources including biological variability (natural variation between individuals or cells), technical noise (from sample processing and sequencing protocols), and measurement error [18] [2].

The practical implication of overdispersion is that it complicates the identification of differentially expressed genes. When overdispersion is not properly accounted for, statistical tests may produce artificially small p-values, leading to false discoveries. As noted in research on microglial RNA-seq datasets, "the main challenge... lies in the high and heterogeneous overdispersion in the read counts," where read counts are highly spread out with variances much larger than means [17].

Statistical Distributions for RNA-Seq Data

Several statistical distributions have been proposed to model RNA-seq count data, each with distinct characteristics and applications:

- Poisson Distribution: Defined by a single parameter (μ) where the variance equals the mean (E(Y) = Var(Y) = μ) [20]. While theoretically appealing for count data, the Poisson distribution is often inadequate for RNA-seq data due to its inability to model overdispersion [18].

- Negative Binomial Distribution: Characterized by mean (μ) and overdispersion parameter (θ), with variance defined as Var(Y) = μ + μ²/θ [17]. This distribution models variance as a quadratic function of the mean and has become a standard choice for many RNA-seq analysis tools.

- Quasi-Poisson Distribution: Another overdispersed alternative where E(Y) = μ and Var(Y) = θμ, modeling variance as a linear function of the mean [17].

Table 1: Statistical Distributions for RNA-Seq Count Data

| Distribution | Mean-Variance Relationship | Overdispersion Parameter | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poisson | Var = μ | None | Technical replicates [20] |

| Negative Binomial | Var = μ + μ²/θ | θ (smaller θ = higher dispersion) | DESeq2, EdgeR [17] |

| Quasi-Poisson | Var = θμ | θ (larger θ = higher dispersion) | DEHOGT method [17] |

Quantitative Characterization of Overdispersion

Empirical Evidence and Measurement

The high-replicate yeast RNA-seq experiment (48 biological replicates) provided robust empirical evidence for overdispersion in transcriptomic data [18]. This study demonstrated that observed gene read counts were consistent with both log-normal and negative binomial distributions, with the mean-variance relation following a constant dispersion parameter of approximately 0.01 [18].

The recently proposed DEHOGT (Differentially Expressed Heterogeneous Overdispersion Genes Testing) method addresses limitations in existing approaches by adopting a gene-wise estimation scheme that does not assume homogeneous dispersion levels across genes with similar expression strength [17]. This approach recognizes that "shrinking the estimates of gene-wise dispersion towards a common value might diminish the true differences in gene expression variability between different genes or conditions" [17].

Impact on Outlier Detection

Overdispersion directly influences outlier detection in RNA-seq analysis. Research has shown that 3-10% of all genes (approximately 350-1350 genes) exhibit extreme outlier expression in at least one individual when using conservative thresholds [2]. These outlier patterns appear to be biological realities rather than technical artifacts, occurring universally across tissues and species [2].

A study of multiple datasets including outbred and inbred mice, human GTEx data, and Drosophila species found that different individuals can harbor very different numbers of outlier genes, with some showing extreme numbers in only one out of several organs [2]. Longitudinal analysis revealed that most extreme over-expression is not inherited but appears sporadically, suggesting these patterns may reflect "edge of chaos" effects in gene regulatory networks characterized by non-linear interactions and feedback loops [2].

Table 2: Methods Addressing Overdispersion in RNA-Seq Analysis

| Method | Approach to Overdispersion | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 [17] | Shrinkage estimation of dispersions | Improved stability and interpretability | May overestimate true biological variability [17] |

| EdgeR [17] | Overdispersed Poisson model | Established methodology for replicated data | Assumes homogeneous dispersion for genes with similar expression [17] |

| DEHOGT [17] | Gene-wise heterogeneous overdispersion modeling | Enhanced power with limited replicates; accounts for dispersion heterogeneity | Computationally intensive for very large datasets |

| sctransform [21] | Regularized negative binomial model with residuals | Effectively removes relationship between UMI count and expression | Primarily designed for single-cell data |

Experimental Protocols for Addressing Confounding and Overdispersion

Robust Experimental Design Protocol

Objective: Design an RNA-seq experiment that minimizes confounding and accurately estimates biological variability.

Procedure:

- Define Factors of Interest: Clearly identify primary experimental factors (e.g., genotype, treatment) and potential nuisance variables (e.g., batch, sex, age) [19].

- Implement Randomization: Randomly assign samples to processing batches and sequencing lanes to prevent systematic confounding [16] [19].

- Balance Experimental Groups: Ensure equal distribution of potential confounding factors (e.g., age, sex) across experimental conditions [19].

- Include Adequate Replication: Include a minimum of 3 biological replicates per condition, with higher replication (10-15) for studies of subtle effects [19].

- Control Technical Variability: Keep testing environments, personnel, and protocols consistent throughout the study [16].

- Record Metadata: Document all potential sources of variation for use in statistical modeling [19].

Quality Control Considerations:

- Assess RNA Integrity Number (RIN) for all samples, ensuring consistency between conditions (RIN ≥ 8 recommended) [19].

- Perform sample correlation analysis to identify "bad" replicates with atypical expression profiles [18].

- Calculate outlier fractions by comparing each gene's expression in individual replicates to trimmed means across replicates [18].

Normalization and Quality Control Protocol

Objective: Account for library size differences and identify technical artifacts.

Procedure:

- Library Size Normalization: Apply appropriate normalization method based on data type:

Variance Stabilizing Transformation: Apply log2 transformation to normalized CPM/TPM values to address heteroskedasticity [21].

Quality Assessment:

Batch Effect Correction: If batches cannot be avoided, apply statistical methods (e.g., ComBat, limma removeBatchEffect) to adjust for batch effects during differential expression analysis.

Outlier Detection and Validation Protocol

Objective: Identify biological versus technical outliers in expression data.

Procedure:

- Normalization: Normalize raw count data using TMM normalization to account for sequencing depth and RNA composition [17].

- Distribution Fitting: For each gene, fit observed read counts to theoretical distributions (Poisson, negative binomial, quasi-Poisson) [17].

- Outlier Identification: Apply Tukey's fences method using interquartile ranges (IQR) around median expression values [2]:

- Calculate Q1 (25th percentile) and Q3 (75th percentile)

- Compute IQR = Q3 - Q1

- Identify outliers as values below Q1 - k×IQR or above Q3 + k×IQR

- Use k=5 for conservative detection of extreme outliers [2]

- Co-expression Analysis: Identify modules of co-regulated outlier genes using correlation networks [2].

- Biological Validation: Examine outlier genes for enrichment in known pathways and functional categories [2].

Visualization Frameworks

RNA-Seq Experimental Design and Confounding

Overdispersion in RNA-Seq Data Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for RNA-Seq Quality Control

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-in Controls [18] | Synthetic RNAs of known concentration for technical variability assessment | Normalization and quality control in bulk RNA-seq |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) [22] | Molecular barcodes to correct for amplification biases | Single-cell RNA-seq experiments for absolute molecule counting |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kits | Remove abundant ribosomal RNA to enrich for mRNA | Working with degraded samples or non-coding RNA analysis |

| Poly-A Selection Kits | Enrich for polyadenylated mRNA molecules | Standard mRNA sequencing from high-quality RNA |

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) Standards | Quantify RNA degradation level using microfluidics | Sample quality assessment prior to library preparation |

| Quantitative PCR Assays | Validate expression of outlier genes | Technical confirmation of RNA-seq findings |

A Practical Guide to Key Outlier Detection Algorithms and Implementation

Outlier detection in RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis is crucial for identifying aberrant gene expression events associated with rare diseases and other pathological conditions. Within this domain, distribution-based methods employing negative binomial models have emerged as powerful statistical frameworks for distinguishing biologically significant outliers from technical noise. The negative binomial distribution is particularly well-suited for modeling RNA-seq count data due to its ability to handle overdispersion—a common characteristic where the variance exceeds the mean in sequencing datasets [23]. This review focuses on two sophisticated implementations of negative binomial models: OUTRIDER (Outlier in RNA-Seq Finder) and ppcseq (Probabilistic Outlier Identification for RNA Sequencing Generalized Linear Models). OUTRIDER utilizes an autoencoder to control for confounders before identifying outliers within a negative binomial framework [24] [25], while ppcseq employs a Bayesian approach with posterior predictive checks to flag transcripts with outlier data points that violate negative binomial assumptions [26] [27]. Both methods address critical limitations in earlier approaches that either lacked proper statistical significance assessments or relied on subjective manual corrections for technical covariates.

Theoretical Foundations of Negative Binomial Models for RNA-Seq Data

The Negative Binomial Distribution in Count Data Modeling

The negative binomial distribution serves as a fundamental statistical framework for modeling RNA-seq count data due to its ability to accommodate overdispersion. The probability mass function (PMF) for a negative binomial random variable X, representing the number of failures before the s-th success in a sequence of Bernoulli trials, is given by:

[P(X=x) = \binom{s+x-1}{x} p^s (1-p)^x]

where (x = 0, 1, 2, \ldots), (s > 0), and (0 < p \leq 1) [23]. The mean and variance of the distribution are (\mu = s\frac{1-p}{p}) and (\sigma^2 = s\frac{1-p}{p^2}), respectively. The variance exceeding the mean ((\sigma^2 > \mu)) makes this distribution particularly suitable for RNA-seq data, which typically exhibits greater variability than would be expected under a Poisson sampling model [27] [23].

The negative binomial distribution can be reparameterized in terms of (\mu) and dispersion parameter (\theta), where (\theta = 1/s). This parameterization is more intuitive for biological applications where the mean expression level and degree of overdispersion are natural parameters of interest. As (\theta \rightarrow 0), the negative binomial distribution converges to the Poisson distribution, illustrating how the former generalizes the latter to account for extra-Poisson variation [23].

In RNA-seq experiments, overdispersion arises from multiple biological and technical sources. Biological replicates exhibit intrinsic variability in mRNA synthesis and degradation rates, even under controlled experimental conditions [27]. Technical variations stem from library preparation protocols, sequencing depth differences, and batch effects [24]. The negative binomial model captures these combined variability sources through its dispersion parameter, providing a more accurate statistical representation of RNA-seq count distributions compared to Poisson models.

OUTRIDER: Implementation of Negative Binomial Models with Autoencoder-Based Covariate Control

Statistical Framework and Algorithm

OUTRIDER implements a sophisticated statistical framework that combines negative binomial modeling with autoencoder-based normalization. The algorithm assumes that the read count (k_{ij}) of gene (j) in sample (i) follows a negative binomial distribution:

[P(k{ij}) = NB(k{ij}|\mu{ij} = c{ij}, \theta_j)]

where (\thetaj) represents the gene-specific dispersion parameter, and the expected count (c{ij}) is the product of a sample-specific size factor (si) and the exponential of the fitted value (y{ij}): (c{ij} = si \cdot \exp(y{ij})) [24]. The size factors (si) account for variations in sequencing depth across samples and are estimated using the median-of-ratios method as implemented in DESeq2 [24].

The key innovation in OUTRIDER is the use of an autoencoder to model the covariation structure (y_{ij}) across genes. The autoencoder, with encoding dimension (q) where (1 < q < \min(p,n)) for (p) genes and (n) samples, captures technical and biological confounders through the transformation:

[yi = hi W_d + b]

[hi = \tilde{x}i W_e]

where (We) is the (p \times q) encoding matrix, (Wd) is the (q \times p) decoding matrix, (h_i) is the encoded representation, and (b) is a bias term [24]. This approach automatically learns and controls for covariation patterns resulting from technical artifacts, environmental factors, or common genetic variations without requiring a priori specification of covariates.

Experimental Protocol for OUTRIDER Implementation

Software Installation and Data Preparation

- Install OUTRIDER from Bioconductor using the R command:

BiocManager::install("OUTRIDER")[28] - Prepare RNA-seq data as a SummarizedExperiment object containing raw count values

- Filter for expressed genes using OUTRIDER's built-in functions (e.g., retain genes with FPKM > 1 in at least 5% of samples) [24]

Model Fitting and Outlier Detection

- Compute size factors for count normalization using the median-of-ratios method

- Fit the autoencoder to estimate expected counts by controlling for covariation:

- Set the encoding dimension (q) using hyperparameter optimization

- Optimize parameters to maximize the recall of artificially corrupted data

- Estimate gene-specific dispersion parameters (\theta_j) constrained to [0.01, 1000] to prevent convergence issues

- Identify aberrantly expressed genes as read counts that significantly deviate from the fitted negative binomial distribution using false-discovery-rate-adjusted p-values [24]

Result Interpretation

- Visualize results using OUTRIDER's plotting functions

- Identify outlier samples with an excessive number of aberrantly expressed genes

- Prioritize candidate genes for further biological validation

Table 1: Key Parameters in OUTRIDER Implementation

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Encoding dimension (q) | Determines complexity of captured covariation | Optimized via cross-validation |

| Dispersion bounds | Constrains gene-specific dispersion estimates | [0.01, 1000] |

| FDR threshold | Controls false discoveries in outlier calls | 0.05 (default) |

| Minimum expression | Filters lowly expressed genes | FPKM > 1 in ≥5% samples |

Figure 1: OUTRIDER Analytical Workflow. The diagram illustrates the stepwise process from raw count data to outlier detection, highlighting the integration of autoencoder-based normalization with negative binomial modeling.

ppcseq: Bayesian Negative Binomial Models with Posterior Predictive Checks

Statistical Framework and Algorithm

ppcseq implements a Bayesian approach to outlier detection in differential expression analyses using negative binomial models with posterior predictive checks. The method addresses the limitation that traditional negative binomial models with thin-tailed gamma distributions are not robust against extreme outliers, which can disproportionately influence statistical inference [27].

The ppcseq framework employs a hierarchical negative binomial regression model that jointly accounts for three types of uncertainty: (1) the mean abundance and overdispersion of transcripts and their log-scale-linear association; (2) the effect of sequencing depth; and (3) the association between transcript abundance and the factors of interest [27]. The core innovation lies in its two-step iterative outlier detection process:

Discovery Step: The model is fitted to differentially expressed transcripts, and posterior predictive distributions are generated. Observed read counts falling outside the 95% posterior credible intervals are flagged as potential outliers.

Test Step: The model is refitted excluding the potential outliers using a truncated negative binomial distribution, and the observed read counts are tested against the refined theoretical distribution with more stringent criteria controlling the false positive rate [27].

This iterative approach prevents outliers from skewing parameter estimates and improves both the sensitivity and specificity of outlier detection.

Experimental Protocol for ppcseq Implementation

Software Installation and System Configuration

- For Linux systems, configure R for multi-threading by creating

~/.R/Makevarswith: - Install ppcseq from Bioconductor:

BiocManager::install("ppcseq")[26]

Data Preparation and Model Fitting

- Format input data as a tidy data frame with columns for sample, symbol (gene identifier), logCPM, LR (likelihood ratio), PValue, FDR, value (count), and experimental factors

- Pre-filter for statistically significant transcripts (e.g., FDR < 0.0001) to focus computational resources

- Implement the outlier identification workflow:

- For large datasets, consider using

approximate_posterior_inference = TRUEto reduce computation time [26]

Posterior Inference and Result Interpretation

- Extract posterior predictive check results and visualize using

plot_credible_intervals() - Identify transcripts with

tot_deleterious_outliers > 0as containing significant outliers - Examine the

ppc_samples_failedcolumn to assess the number of samples where the observed data significantly deviates from the model expectations

Table 2: Key Parameters in ppcseq Implementation

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Setting |

|---|---|---|

| percentfalsepositive_genes | Controls false positive rate in discovery phase | 1-5% |

| approximateposteriorinference | Uses variational Bayes approximation for speed | FALSE for accuracy, TRUE for large datasets |

| cores | Number of processing cores for parallelization | 1 to maximum available |

| .do_check | Logical vector indicating which transcripts to test | Pre-filtered significant transcripts |

Figure 2: ppcseq Iterative Outlier Detection Workflow. The two-stage process identifies potential outliers with relaxed criteria, then tests them against a refined model with stringent false positive control.

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

Technical Comparisons Between OUTRIDER and ppcseq

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of OUTRIDER and ppcseq

| Feature | OUTRIDER | ppcseq |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Foundation | Frequentist with FDR control | Bayesian with posterior predictive checks |

| Primary Application | Rare disease diagnostics: identifying aberrant expression in individual samples | Differential expression quality control: flagging outlier-inflated statistics |

| Confounder Control | Autoencoder (unsupervised) | Experimental design factors (supervised) |

| Dispersion Estimation | Gene-specific with constraints | Hierarchical Bayesian shrinkage |

| Input Requirements | Raw counts from multiple samples | Differential expression results with raw counts |

| Computational Demand | Moderate (autoencoder training) | High (MCMC sampling) |

| Multiple Testing Correction | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR | Bayesian false positive rate control |

| Output | Significance-based outlier calls | Posterior probabilities of outlier status |

Practical Applications in Rare Disease Research

Both OUTRIDER and ppcseq have demonstrated significant utility in rare disease diagnostics and transcriptomic analysis. OUTRIDER has been successfully applied to identify aberrantly expressed genes in rare disease cohorts, serving as a complementary approach to genome sequencing for pinpointing regulatory variants that may escape detection in standard analyses [24] [25]. The method's ability to automatically control for technical and biological confounders makes it particularly valuable in diagnostic settings where a priori knowledge of relevant covariates may be limited.

ppcseq addresses a different but equally important challenge in transcriptomic studies: ensuring the reliability of differential expression results. By identifying and flagging transcripts whose statistics are inflated by outlier values, ppcseq improves the validity of downstream analyses and biological interpretations. Applied studies have revealed that 3-10% of differentially abundant transcripts across algorithms and datasets contain statistics inflated by outliers [27], highlighting the importance of this quality control step.

Recent research has further demonstrated the value of transcriptome-wide outlier approaches in identifying specific rare disease mechanisms. A 2025 study by Arriaga et al. utilized splicing outlier detection methods to identify individuals with minor spliceopathies, discovering five individuals with excess intron retention outliers in minor intron-containing genes who harbored rare variants in minor spliceosome components [7] [11]. This work illustrates how outlier detection methods can reveal novel disease mechanisms that would be missed by standard variant-centric approaches.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Implementation

| Resource | Type | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| OUTRIDER R Package | Software | Implements autoencoder-controlled negative binomial outlier detection | Available via Bioconductor; requires R>=3.6 [28] |

| ppcseq R Package | Software | Bayesian outlier detection with posterior predictive checks | Requires Stan and rstan dependencies [26] |

| DESeq2 | Software | Provides core negative binomial functionality and size factor estimation | Dependency for both OUTRIDER and ppcseq [24] [27] |

| Stan | Software | Probabilistic programming language for Bayesian inference | Required for ppcseq; enables Hamiltonian Monte Carlo sampling [27] |

| RNA-seq Count Data | Data Input | Raw read counts per gene across multiple samples | Essential input format for both methods |

| High-Performance Computing | Infrastructure | Parallel processing for computationally intensive steps | Multi-core systems significantly reduce runtime for both tools |

| Housekeeping Gene Set | Reference Data | Transcripts with stable expression for normalization | Used by ppcseq for inferring sequencing depth effects [27] |

Negative binomial models implemented in OUTRIDER and ppcseq represent sophisticated approaches to outlier detection in RNA-seq analysis, each with distinct strengths and applications. OUTRIDER's integration of autoencoder-based confounder control with negative binomial modeling provides a powerful framework for identifying aberrant expression in rare disease diagnostics, particularly when technical and biological covariates are unknown or complex. Meanwhile, ppcseq's Bayesian approach with iterative posterior predictive checks offers robust quality control for differential expression analyses by identifying transcripts with statistics inflated by outlier values. As RNA-seq continues to evolve as a diagnostic and research tool, these distribution-based methods will play an increasingly important role in ensuring the validity and biological interpretability of transcriptomic findings.

In the analysis of high-dimensional RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data, the accurate detection of outlier samples is a critical preprocessing step. Outliers can arise from technical artifacts during complex multi-step protocols or from genuine but extreme biological variation [29]. Their presence can significantly skew downstream analyses, such as differential gene expression testing, leading to reduced accuracy and unreliable biological conclusions [29] [2]. This application note focuses on two powerful dimension-reduction-based approaches for outlier detection: OUTSINGLE, which utilizes Singular Value Decomposition and the Optimal Hard Threshold (SVD/OHT), and Robust PCA methods, specifically PcaGrid and PcaHubert. These methods are particularly suited for the high-dimensionality and small sample sizes typical of RNA-seq datasets [29] [30]. We detail their protocols, performance, and integration into a robust RNA-seq analysis workflow, providing a essential guide for researchers and drug development scientists.

Key Concepts and Methodologies

OutSingle: SVD and Optimal Hard Threshold (OHT)

OUTSINGLE is a Python tool designed to identify outliers in RNA-seq gene expression count data. Its core innovation lies in using SVD to decompose the gene expression matrix, followed by the application of an Optimal Hard Threshold to the singular values. This process effectively separates the signal from the noise, allowing for the calculation of robust outlier scores for each gene [30]. The method is classified as a backward search gene filtering approach, meaning it starts with the full gene set and removes those deemed uninformative or noisy [31]. OUTSINGLE has been benchmarked against other gene filtering methods and has shown proficiency in identifying genes with anomalous expression confined to specific samples, thereby reducing technical noise while preserving biologically relevant signals [31].

Robust PCA (PcaGrid and PcaHubert)

Classical Principal Component Analysis (cPCA) is highly sensitive to outliers, which can disproportionately influence the principal components and mask the true data structure. Robust PCA (rPCA) methods, such as PcaGrid and PcaHubert, address this limitation by employing robust statistical estimators that are less susceptible to extreme values [29]. These algorithms first fit the majority of the data before flagging deviant data points.

- PcaGrid: This method achieves a high breakdown point, meaning it can tolerate a large proportion of outliers without its estimates being significantly affected. It has demonstrated 100% sensitivity and specificity in tests with RNA-seq data containing positive control outliers [29] [32].

- PcaHubert: This approach combines robust covariance estimation with a projection-pursuit method to identify outliers effectively [29].

In comparative studies on real biological RNA-seq data, both rPCA methods successfully identified outlier samples that classical PCA failed to detect [29]. The application of rPCA for sample-level outlier detection is distinct from gene filtering and is a recommended quality control step prior to differential expression analysis [33].

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Data

The following tables summarize the key characteristics and performance metrics of the outlined outlier detection methods as reported in the literature.

Table 1: Method Overview and Key Features

| Method | Core Algorithm | Implementation | Primary Target | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OUTSINGLE | SVD with Optimal Hard Threshold | Python | Outlier Genes | Identifies sample-biased genes; reduces technical noise [30] [31] |

| PcaGrid | Robust PCA | R (rrcov package) | Outlier Samples | High breakdown point; 100% sens/spec in controlled tests [29] [34] |

| PcaHubert | Robust PCA (Projection Pursuit) | R (rrcov package) | Outlier Samples | Effective outlier flagging; robust covariance estimation [29] |

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks from Literature

| Method | Reported Sensitivity & Specificity | Use Case Evidence | Comparative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PcaGrid | 100% sensitivity and specificity on simulated RNA-seq data with positive control outliers [29] [32] | Detection of two outlier samples in mouse cerebellum RNA-seq data; improved DEG analysis post-removal [29] | Superior to classical PCA, which failed to detect the outliers [29] |

| PcaHubert | High accuracy in outlier detection (specific metrics not provided) [29] | Detected the same two outlier samples as PcaGrid in a real mouse RNA-seq dataset [29] | Comparable to PcaGrid on real data [29] |

| OUTSINGLE | Effective identification of artificial outliers injected into real datasets [30] | Identification of outlier genes in TCGA cancer data and COVID-19 scRNA-seq data [31] | Proficiently identifies genes with expression anomalies in specific samples [31] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Outlier Sample Detection with Robust PCA in R

This protocol details the steps for identifying outlier samples in an RNA-seq dataset using robust PCA methods, specifically PcaGrid, within the R statistical environment [29] [34].

1. Preprocessing and Data Preparation:

- Begin with a normalized count matrix, such as the one obtained from DESeq2's rlog or vst transformation. The matrix should be structured with genes as rows and samples as columns.

- Critical Step: Transpose the normalized count matrix so that samples are rows and genes are columns, as required by the PcaGrid function [34].

2. Execute Robust PCA:

- Utilize the rrcov package in R. Compute the robust PCA on the transposed matrix.

- Code Example:

3. Identify and Review Outlier Samples:

- The PcaGrid object contains a @flag slot where FALSE values indicate outliers.

- Code Example:

4. Downstream Analysis: - Remove the identified outlier samples from the original dataset or include the robust PCA components as covariates in subsequent differential expression models to control for their effects [29].

Protocol 2: Outlier Gene Detection with OUTSINGLE in Python

This protocol describes the process of detecting outlier genes using the OUTSINGLE tool from a Python command-line interface [30].

1. Environment and Data Setup:

- Clone the OUTSINGLE repository from GitHub and install its dependencies using pip install -r requirements.txt.

- Prepare your input data as a tab-separated CSV file. The file's first column should contain gene names, the first row should contain sample names, and all other cells should contain integer count data [30].

2. Z-score Estimation: - Run the initial z-score estimation on your dataset. - Code Example (execute in terminal):

3. Outsingle Score Calculation: - Calculate the final OUTSINGLE score, which produces several files with artificial outliers and corresponding outlier mask files for evaluation. - Code Example (execute in terminal):

4. Results Interpretation:

- The output includes files with suffixes indicating the parameters of the analysis (e.g., -f1-b-z6.00.txt signifies a frequency of 1 outlier per sample, both positive and negative outliers, and a z-score magnitude of 6.00).

- The outlier mask files (with omask in the name) contain matrices of zeros with 1 or -1 indicating the location and direction of outlier genes [30]. These coordinates can be used to filter the gene set before downstream analyses like differential expression.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points for integrating these outlier detection methods into a standard RNA-seq analysis pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Packages for Implementation

| Tool Name | Language/Platform | Function/Purpose | Key Command/Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| rrcov | R | Provides implementations of robust PCA methods, including PcaGrid and PcaHubert. |

PcaGrid(), PcaHubert() [29] [34] |

| DESeq2 | R | Used for normalization and transformation of RNA-seq count data prior to outlier detection. | rlog(), vst() [34] |

| OUTSINGLE | Python | A dedicated package for finding outlier genes in RNA-seq count data using SVD and OHT. | fast_zscore_estimation.py, outsingle.py [30] |

| EIGENSOFT/smartpca | C++/Unix | A standard suite for population genetics, often used for PCA in genomics; can be complemented with robust methods. | smartpca [33] |

| PLINK | C++/Unix | Used for LD pruning and quality control of genetic data prior to PCA, a common step in GWAS. | --indep-pairwise [33] |