A Comprehensive Guide to Performing PCA on Gene Expression Data: From Theory to Clinical Applications

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for applying Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to gene expression data.

A Comprehensive Guide to Performing PCA on Gene Expression Data: From Theory to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for applying Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to gene expression data. Covering foundational concepts of dimensionality reduction in transcriptomics, we detail practical implementation workflows in R, address common troubleshooting scenarios, and explore advanced optimization techniques. The guide also examines validation methodologies and compares PCA with emerging techniques, empowering biomedical professionals to effectively leverage PCA for uncovering biological patterns in high-throughput genomic data.

Understanding PCA and the Dimensionality Challenge in Genomics

The Curse of Dimensionality in Transcriptomic Data

High-throughput transcriptomic technologies generate data where the number of variables (genes) vastly exceeds the number of observations (samples), creating a scenario known as the "curse of dimensionality." This phenomenon presents substantial challenges for statistical analysis and biological interpretation. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as a fundamental computational technique to address these challenges by reducing dimensionality while preserving essential biological signals. This technical guide examines the theoretical foundations of high-dimensional spaces in transcriptomics, provides practical PCA implementation workflows, and explores advanced methodologies for extracting meaningful biological insights from complex gene expression data.

Transcriptomic technologies, including microarrays and RNA-sequencing, routinely generate datasets where each sample is characterized by tens of thousands of gene expression measurements. A typical experiment might yield 20,000-50,000 measurements per sample, often with fewer than 100 biological replicates [1] [2]. This P≫N scenario (where P represents variables/genes and N represents observations/samples) creates fundamental analytical challenges that transcend mere computational burden.

The "curse of dimensionality" refers to the collection of problems that arise when working with data in high-dimensional spaces that do not occur in low-dimensional settings [3]. These include spurious correlations, distance concentration phenomena (where nearest and farthest neighbors become equidistant), and model overfitting that can lead to biologically implausible conclusions [3]. In transcriptomics, these challenges are compounded by the biological reality that gene expression is controlled by complex, interconnected regulatory networks rather than independent variables.

Principal Component Analysis addresses these challenges by transforming the original high-dimensional gene expression space into a lower-dimensional subspace defined by orthogonal principal components that capture maximum variance. When properly applied, PCA can mitigate overfitting, reduce noise, and reveal underlying biological structures such as cell types, disease subtypes, and developmental trajectories [4] [5].

Fundamental Challenges in High-Dimensional Transcriptomic Spaces

Mathematical and Statistical Consequences

High-dimensional gene expression spaces exhibit properties that often contradict human geometric intuition. As dimensionality increases, the available data becomes increasingly sparse, with pairwise distances between samples becoming more similar [3]. This distance concentration effect can impair the performance of clustering and classification algorithms that rely on distance metrics.

The table below summarizes key statistical challenges in high-dimensional transcriptomic analysis:

Table 1: Statistical challenges posed by high-dimensional transcriptomic data

| Challenge | Impact on Analysis | Potential Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Testing Problem | When testing 20,000 genes at α=0.05, 1,000 false positives are expected by chance [1] | High false discovery rates without appropriate correction |

| Spurious Correlations | Apparent but biologically meaningless correlations increase with dimensionality [3] | Incorrect inference of gene regulatory relationships |

| Model Overfitting | Models with thousands of parameters fit to dozens of samples memorize noise rather than learning signal [3] | Poor generalizability to new datasets; irreproducible findings |

| Data Sparsity | Data points become isolated in high-dimensional space, breaking distance-based algorithms [3] | Reduced clustering performance and neighborhood detection |

Biological Interpretation Complexities

Beyond mathematical challenges, high-dimensional transcriptomic data reflects biological complexity. Gene expression patterns exhibit multimodality due to heterogeneous cell populations within samples, concurrent activation of multiple biological processes, and tissue-specific gene activities [3]. This biological richness can confound simple interpretations, as principal components may capture technical artifacts, batch effects, or dominant biological processes that obscure more subtle but functionally important signals.

Studies of large, heterogeneous gene expression datasets suggest that while the first few principal components often capture major biological axes (e.g., hematopoietic vs. neural lineages, malignant vs. normal states), tissue-specific information frequently resides in higher-order components [5]. This indicates that the linear intrinsic dimensionality of global gene expression space is higher than previously recognized, with relevant biological signal distributed beyond the first 3-4 principal components.

Principal Component Analysis: Theoretical Foundations

Core Mathematical Framework

PCA transforms possibly correlated variables (gene expression levels) into a set of linearly uncorrelated variables called principal components (PCs), ordered by the fraction of total variance they explain. The first PC accounts for the largest possible variance, with each succeeding component accounting for the highest possible variance under the constraint of orthogonality to preceding components.

Given a gene expression matrix X with dimensions n×p (n samples, p genes), after centering the data to have zero mean, PCA computes the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the covariance matrix C = XᵀX/(n-1). The principal components are obtained by projecting the original data onto the eigenvectors: Z = XV, where V contains the eigenvectors of C.

The proportion of total variance explained by the k-th principal component is λₖ/∑ᵢλᵢ, where λₖ is the k-th eigenvalue. This allows researchers to determine how many components to retain for downstream analysis.

Advanced PCA Variations for Transcriptomic Data

Several specialized PCA variants have been developed to address specific challenges in transcriptomic data analysis:

Sparse PCA: Incorporates sparsity constraints to produce loading vectors with many zero elements, improving biological interpretability by identifying smaller gene subsets that drive each component [4]. The optimization problem can be formulated as minimizing the reconstruction error with L1 regularization: min‖X - XWWᵀ‖₂² + λ‖W‖₁.

Kernel PCA: Applies kernel functions to capture non-linear relationships in gene expression data by implicitly mapping observations into higher-dimensional feature spaces before performing PCA [4]. This approach can reveal complex patterns that linear PCA might miss.

Functional PCA (fPCA): Designed for analyzing time-series transcriptomic data, such as gene expression during differentiation or treatment response, by treating observations as functions over a continuous domain rather than discrete measurements [4].

Practical Workflow for PCA on Transcriptomic Data

Preprocessing and Normalization

Proper preprocessing is critical for meaningful PCA results. For transcriptomic data, this typically involves:

- Quality Control: Filtering genes with low expression and samples with poor quality metrics.

- Normalization: Correcting for technical variation (e.g., sequencing depth, batch effects) while preserving biological signal.

- Transformations: Applying appropriate transformations (e.g., log, VST) to stabilize variance across the dynamic range of expression.

For single-cell RNA-seq data, recent methods like regularized negative binomial regression (sctransform) effectively normalize count data while controlling for technical covariates like sequencing depth [6]. Traditional size-factor-based normalization methods (e.g., TMM, RLE) may inadequately handle genes with different abundance levels, potentially introducing artifacts in PCA [6].

Table 2: Normalization methods for unbalanced transcriptomic data

| Method | Platform | Reference Strategy | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRSN | Microarray | Data-driven subset | Uses global rank-invariant sets with loess smoothing |

| IRON | Microarray | Data-driven subset | Iterative rank-order normalization for skewed data |

| TMM | RNA-seq | Entire gene set | Trimmed mean of M-values; assumes most genes not DE |

| sctransform | scRNA-seq | Regularized GLM | Negative binomial regression with regularization |

| Spike-in Controls | Both | Foreign reference | Uses externally added controls as reference |

Component Selection Strategies

Determining the number of components to retain represents a critical step in PCA. Several automated methods exist:

- Scree Plot Analysis: Visual inspection of the eigenvalue curve to identify an "elbow" point where eigenvalues plateau.

- Kaiser Criterion: Retaining components with eigenvalues greater than 1.

- Cross-Validation: Evaluating reconstruction error across training and validation splits.

- Parallel Analysis: Comparing observed eigenvalues to those from random datasets with equivalent dimensionality.

For large, heterogeneous transcriptomic datasets, evidence suggests that more components contain biological signal than previously assumed. While early studies suggested only 3-4 components were meaningful, more recent analyses of datasets with 5,000+ samples indicate that 10+ components may capture biologically relevant variation, particularly for within-tissue comparisons [5].

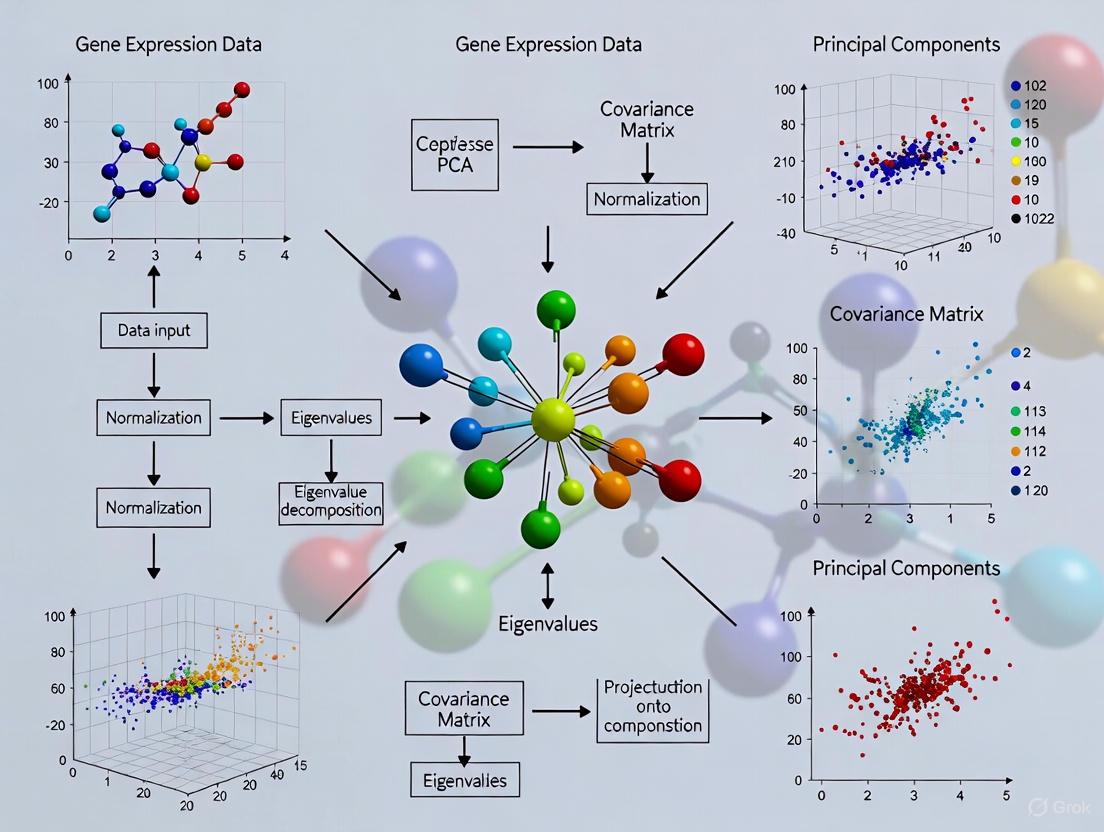

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete PCA process for transcriptomic data:

Interpretation and Validation of PCA Results

Biological Interpretation of Components

Interpreting principal components biologically requires connecting mathematical representations to biological knowledge. Effective strategies include:

- Gene Loading Analysis: Examining genes with highest absolute loadings for each component to identify biologically coherent gene sets.

- Pathway Enrichment: Testing whether high-loading genes are enriched for specific biological pathways or functions.

- Correlation with Phenotypes: Assessing relationships between component scores and sample metadata (e.g., clinical variables, treatment responses).

In large-scale analyses, the first principal components often separate major biological categories. For example, in a pan-tissue analysis of 7,100 samples, the first three components separated hematopoietic cells, neural tissues, and cell lines, while the fourth component captured liver-specific expression [5]. The specific components recovered depend strongly on sample composition, with overrepresented tissues dominating early components.

Validation and Robustness Assessment

Validating PCA results is essential to ensure findings reflect biology rather than analytical artifacts:

- Stability Analysis: Assessing consistency of components across subsampled datasets or bootstrapped samples.

- Visualization Diagnostics: Using tools like distnet to examine discrepancies between low-dimensional embeddings and actual high-dimensional distances [7].

- Independent Validation: Confirming biological interpretations in external datasets or through experimental follow-up.

Interactive visualization tools like focusedMDS enable exploration of specific sample relationships by creating embeddings that accurately preserve distances between a focal point and all other samples [7]. This approach helps verify whether apparent clustering in standard PCA plots reflects true biological similarity.

Advanced Applications and Integration with Other Methods

PCA in Integrated Analysis Workflows

PCA serves as a foundational step in more complex analytical workflows:

- Clustering Post-PCA: Applying clustering algorithms to PCA-reduced data mitigates the curse of dimensionality and improves cluster stability and biological interpretability [4].

- Principal Component Regression (PCR): Using principal components as predictors in regression models addresses multicollinearity in high-dimensional transcriptomic data [4].

- Multi-Omics Integration: Applying PCA to combined datasets from multiple molecular platforms (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics) to identify cross-platform patterns.

Beyond Linear Dimensionality Reduction

While PCA is invaluable for linear dimensionality reduction, several methods address its limitations:

- PHATE (Potential of Heat-diffusion for Affinity-based Transition Embedding): A visualization method that captures both local and global nonlinear structures using information-geometric distances, often revealing patterns missed by PCA [8].

- t-SNE and UMAP: Nonlinear techniques particularly effective for visualizing complex manifold structures in single-cell transcriptomic data, though with potential limitations in preserving global structure [8].

The following diagram compares dimensionality reduction approaches:

Table 3: Computational tools for high-dimensional transcriptomic analysis

| Tool/Package | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat | Single-cell analysis | scRNA-seq | PCA integration, visualization, downstream analysis |

| SCANPY | Single-cell analysis | scRNA-seq | PCA, clustering, trajectory inference in Python |

| sctransform | Normalization | scRNA-seq | Regularized negative binomial regression |

| PHATE | Visualization | Various | Captures nonlinear progression and branches |

| distnet/focusedMDS | Validation | Various | Interactive visualization of distance preservation |

| Scran | Normalization | scRNA-seq | Pool-based size factor estimation |

The curse of dimensionality presents significant but surmountable challenges in transcriptomic data analysis. Principal Component Analysis remains a cornerstone technique for addressing these challenges, providing a mathematically principled approach to dimensionality reduction that preserves biological signal while mitigating technical noise. Successful application requires careful attention to preprocessing, component selection, and validation, with awareness that biological information often extends beyond the first few components.

As transcriptomic technologies continue to evolve, generating ever-larger and more complex datasets, advanced PCA variations and complementary nonlinear methods will play increasingly important roles in extracting biologically meaningful insights. By understanding both the capabilities and limitations of these approaches, researchers can more effectively navigate high-dimensional transcriptomic spaces to advance biological discovery and therapeutic development.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as a foundational dimensionality reduction technique in computational biology, transforming high-dimensional gene expression data into a lower-dimensional space defined by core mathematical principles. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of how variance, covariance, and eigen decomposition form the mathematical bedrock of PCA, with specific application to gene expression data analysis. We detail the theoretical framework, practical implementation workflows, and experimental considerations for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with transcriptomic data. The guidance emphasizes proper application in bioinformatics contexts where the number of variables (genes) dramatically exceeds the number of observations (samples), including critical considerations for effective dimensionality determination and biological interpretation.

Gene expression studies from technologies like RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and microarrays generate data matrices of profound dimensionality, where measurements for tens of thousands of genes (features) span relatively few biological samples (observations) [9] [10]. This "large d, small n" characteristic presents significant analytical challenges for visualization, statistical analysis, and pattern recognition. Principal Component Analysis (PCA), first introduced by Karl Pearson in 1901, addresses these challenges through an orthogonal transformation that converts potentially correlated gene expression measurements into a set of linearly uncorrelated variables called principal components (PCs) [11] [12].

In bioinformatics, PCA transcends mere dimensionality reduction, serving as an indispensable tool for exploratory data analysis, quality assessment, outlier detection, and batch effect identification [10]. The technique operates on a fundamental premise: while genomic data inhabits a high-dimensional space, the biologically relevant signals often concentrate in a much lower-dimensional subspace. PCA identifies this subspace through a mathematical framework built upon three core principles: variance, covariance, and eigen decomposition. These principles collectively enable researchers to project gene expression data into a new coordinate system where the greatest variances align with the first principal component, subsequent orthogonal directions capture remaining variance, and noise is systematically filtered [13] [9].

Mathematical Foundations

Variance and Covariance

In the context of gene expression analysis, variance measures the dispersion of individual gene expression values across biological samples. For a single gene ( g ) with expression values ( \mathbf{x}g = (x{g1}, x{g2}, ..., x{gn}) ) across ( n ) samples, the sample variance is calculated as:

[ \text{Var}(\mathbf{x}g) = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum{i=1}^{n} (x{gi} - \bar{x}g)^2 ]

where ( \bar{x}_g ) represents the mean expression of gene ( g ) across all samples. High variance indicates a gene with expression levels that fluctuate substantially across samples, potentially reflecting biologically relevant differential expression rather than technical noise [14].

Covariance quantifies the coordinated relationship between pairs of genes across samples. For two genes ( g ) and ( h ) with expression vectors ( \mathbf{x}g ) and ( \mathbf{x}h ), their sample covariance is:

[ \text{Cov}(\mathbf{x}g, \mathbf{x}h) = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum{i=1}^{n} (x{gi} - \bar{x}g)(x{hi} - \bar{x}_h) ]

Positive covariance indicates that the two genes tend to be upregulated or downregulated together across samples, potentially suggesting co-regulation or functional relationship. Negative covariance implies an inverse relationship, where one gene's increased expression correlates with the other's decrease. A covariance near zero suggests independence between the genes' expression patterns [11].

The covariance matrix ( \mathbf{\Sigma} ) comprehensively captures these relationships across all genes in the dataset. For a gene expression matrix ( \mathbf{X} ) with ( p ) genes (rows) and ( n ) samples (columns), where each column has been mean-centered, the covariance matrix is computed as:

[ \mathbf{\Sigma} = \frac{1}{n-1} \mathbf{X} \mathbf{X}^T ]

This ( p \times p ) symmetric matrix contains the variance of each gene along its diagonal and covariances between gene pairs in off-diagonal elements [11] [12]. The covariance matrix is fundamental to PCA as it encodes the complete variance structure of the gene expression dataset.

Eigen Decomposition

Eigen decomposition, also known as spectral decomposition, extracts the fundamental directions and magnitudes of variance from the covariance matrix. For the covariance matrix ( \mathbf{\Sigma} ), eigen decomposition solves the equation:

[ \mathbf{\Sigma} \mathbf{v}i = \lambdai \mathbf{v}_i ]

where:

- ( \lambda_i ) represents the ( i )-th eigenvalue, quantifying the amount of variance captured along the corresponding direction

- ( \mathbf{v}_i ) represents the ( i )-th eigenvector, defining the direction of the ( i )-th principal component in the original gene space [11] [12]

The eigenvectors form a new orthonormal basis for the data, with the crucial property that ( \mathbf{v}i^T \mathbf{v}j = 0 ) for ( i \neq j ) and ( \mathbf{v}i^T \mathbf{v}i = 1 ). The eigenvalues are typically ordered in decreasing magnitude (( \lambda1 \geq \lambda2 \geq \ldots \geq \lambda_p )), establishing a hierarchy of principal components by their importance in explaining the overall variance [13] [9].

The proportion of total variance explained by the ( i )-th principal component is given by:

[ \text{Variance Explained}i = \frac{\lambdai}{\sum{j=1}^{p} \lambdaj} ]

This allows researchers to determine how many principal components are needed to capture a sufficient amount of the biological signal in the data [13].

Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) Relationship

While eigen decomposition operates on the covariance matrix, PCA can be equivalently implemented via Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) applied directly to the mean-centered data matrix ( \mathbf{X} ). The SVD approach decomposes:

[ \mathbf{X} = \mathbf{U} \boldsymbol{\Delta} \mathbf{V}^T ]

where:

- ( \mathbf{U} ) is an ( n \times n ) orthogonal matrix containing the left singular vectors

- ( \boldsymbol{\Delta} ) is an ( n \times p ) rectangular diagonal matrix with non-negative singular values ( \delta_i ) on the diagonal

- ( \mathbf{V} ) is a ( p \times p ) orthogonal matrix containing the right singular vectors [15]

The equivalence emerges through the relationship:

- The right singular vectors ( \mathbf{V} ) correspond to the eigenvectors of ( \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X} )

- The singular values ( \deltai ) relate to eigenvalues via ( \lambdai = \delta_i^2 / (n-1) )

- The principal components (scores) are given by ( \mathbf{U} \boldsymbol{\Delta} ) [15]

SVD provides computational advantages for gene expression data where ( p \gg n ) by avoiding explicit construction of the massive ( p \times p ) covariance matrix.

Workflow for Gene Expression Data

Data Preprocessing

Proper preprocessing of gene expression data is critical for meaningful PCA results. For RNA-seq count data, this typically involves:

Normalization: Addressing differences in sequencing depth across samples using methods like DESeq2's median-of-ratios, TPM (Transcripts Per Million), or other normalization techniques implemented in packages such as DESeq2 [10].

Transformation: Converting count data to approximate homoscedasticity (equal variance) through variance-stabilizing transformations (VST) or log2 transformation after adding a pseudocount [10].

Standardization: Scaling genes to have mean zero and unit variance (Z-score normalization), which gives equal weight to all genes regardless of their original expression levels. This is particularly important when using covariance-based PCA, as high-expression genes would otherwise dominate the analysis [13] [12].

Mean Centering: Subtracting the mean expression of each gene across all samples, a prerequisite for covariance matrix computation [12].

Covariance Matrix and Eigen Decomposition

Following preprocessing, the mathematical core of PCA begins with computation of the covariance matrix ( \mathbf{\Sigma} ) from the processed expression matrix ( \mathbf{X} ). For a gene expression dataset with ( p ) genes and ( n ) samples:

[ \mathbf{\Sigma} = \frac{1}{n-1} \mathbf{X} \mathbf{X}^T ]

Eigen decomposition of ( \mathbf{\Sigma} ) yields eigenvectors (principal directions) and eigenvalues (variance explained). In practice, for high-dimensional gene expression data where ( p \gg n ), computational efficiency is dramatically improved by performing SVD directly on ( \mathbf{X} ) rather than explicitly computing the ( p \times p ) covariance matrix [15].

Component Selection

Determining the number of meaningful principal components represents a critical step with significant implications for biological interpretation. Several methods facilitate this decision:

Table 1: Methods for Determining Principal Components in Gene Expression Studies

| Method | Description | Application Context | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scree Plot | Visual inspection of eigenvalue magnitude drop-off | Initial exploratory analysis | Intuitive visualization | Subjective interpretation |

| Cumulative Variance | Components explaining >80-95% total variance | General purpose gene expression studies | Objective threshold | May retain noise components |

| Amemiya's Test | Statistical testing for dimensionality [16] | Formal hypothesis testing | Statistical rigor | Computationally intensive |

| Factor-Analytic Modeling | Mixed-model framework [16] | Experimental designs with random effects | Integrates with linear models | Complex implementation |

In gene expression studies, the effective dimensionality often proves much lower than the number of samples or genes. Research indicates that while 3-4 principal components might capture major patterns in heterogeneous datasets, additional components frequently contain biologically relevant information specific to particular tissues or conditions [14].

Data Projection and Interpretation

The original gene expression data projects onto the selected principal components through matrix multiplication:

[ \mathbf{Z} = \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{V}_k ]

where ( \mathbf{V}_k ) contains the first ( k ) eigenvectors and ( \mathbf{Z} ) represents the projected data in the new ( k )-dimensional space. This transformed data enables two primary types of biological interpretation:

Sample-Level Patterns: The projected coordinates (PC scores) reveal sample relationships, clusters, and outliers when visualized in 2D or 3D plots [13] [10].

Gene-Level Contributions: Eigenvector elements (loadings) indicate how strongly each gene contributes to each principal component. Genes with large absolute loadings drive the separation of samples along that component and may represent biologically coherent gene sets [13].

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Standard Protocol for RNA-seq Data PCA

Purpose: To identify major patterns of variation, batch effects, outliers, and potential confounders in RNA-seq gene expression data.

Materials:

- Raw count matrix from RNA-seq alignment (e.g., from featureCounts or HTSeq)

- Experimental metadata table with sample annotations

- Computational environment with R/Bioconductor

Procedure:

- Load count data and metadata into R, creating a DESeqDataSet or similar object [10].

- Apply normalization (e.g., DESeq2's median-of-ratios) and transformation (variance-stabilizing or log2).

- Perform mean centering and optional scaling of the transformed expression values.

- Execute PCA using the

prcomp()function in R. - Extract eigenvalues and eigenvectors from the result object.

- Generate diagnostic plots including scree plot and cumulative variance plot.

- Visualize sample relationships using the first 2-3 principal components, coloring by experimental conditions.

- Identify genes with extreme loadings on biologically interesting components.

- Perform functional enrichment analysis on high-loading genes.

Troubleshooting:

- If first PC correlates strongly with technical batches, consider batch correction before PCA.

- If samples form unexpected clusters, investigate potential confounding variables.

- If few components explain little variance, assess data quality and normalization.

Advanced Protocol: Determining Effective Dimensionality

Purpose: To statistically determine the number of significant biological dimensions in gene expression data.

Materials:

- Processed gene expression matrix

- Experimental design information

Procedure (adapted from Amemiya's approach [16]):

- Compute the between-groups and within-groups mean square matrices (( \mathbf{MB} ) and ( \mathbf{MW} )) based on the experimental design.

- Calculate the characteristic roots (( \lambdai )) of ( \mathbf{MB} ) in the metric of ( \mathbf{MW} ) by solving ( \|\mathbf{MB} - \lambda \mathbf{M_W}\| = 0 ).

- Order characteristic roots from largest to smallest.

- Sequentially test null hypotheses ( m \leq b ) for ( b = 0, 1, 2, \ldots ) using the test statistic:

[ Yb = (M + N - 2b - 2) \sum{i=b+1}^{k} \ln(1 + \lambdai) - 2 \sum{i=b+1}^{k} \ln(\lambda_i) ]

where ( M ) and ( N ) are between-groups and within-groups degrees of freedom.

- Compare test statistics to critical values from Amemiya et al. (1990) [16].

- Reject the null hypothesis when test statistic exceeds critical value, establishing evidence for at least ( b+1 ) dimensions.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for PCA in Gene Expression Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Normalization and transformation of RNA-seq counts | Bulk RNA-seq data preprocessing | R/Bioconductor package |

| pcaExplorer | Interactive exploration of PCA results | RNA-seq data visualization | R/Bioconductor package [10] |

| prcomp() | Core PCA computation using SVD | General gene expression data | Base R function [13] |

| FactoMineR | Advanced PCA with supplementary variable projection | Integration of clinical and expression data | R package |

| SCONE | PCA-based quality control for single-cell RNA-seq | Single-cell transcriptomics | R/Bioconductor package |

Case Study: PCA in Large-Scale Transcriptomics

A landmark study by Lukk et al. (2016) applied PCA to a massive gene expression dataset comprising 5,372 samples from 369 different human tissues, cell types, and disease states [14]. This analysis demonstrated both the power and limitations of PCA for global transcriptome analysis.

The first three principal components captured approximately 36% of the total variance and corresponded to broad biological categories:

- PC1 separated hematopoietic cells from other tissues

- PC2 distinguished malignant from non-malignant samples

- PC3 differentiated neural tissues from other cell types

However, subsequent investigation revealed that higher-order components contained significant biological information despite explaining less variance. When the dataset was decomposed into the first three components ("projected" space) and remaining components ("residual" space), tissue-specific correlation patterns persisted strongly in the residual space [14]. This finding contradicted the assumption that biological signals concentrate exclusively in the first few components and highlighted the importance of methodical component selection.

Further analysis demonstrated that sample composition dramatically influences PCA results. When the proportion of liver samples was systematically varied, the fourth principal component transitioned from non-interpretable to clearly separating liver and hepatocellular carcinoma samples [14]. This underscores how study design and sample selection fundamentally shape the principal components obtained.

Advanced Considerations

Limitations and Assumptions

PCA operates under several mathematical assumptions that merit consideration in gene expression contexts:

Linearity: PCA assumes linear relationships between variables, while gene regulatory networks often exhibit nonlinear behaviors. Kernel PCA addresses this limitation for certain applications [12] [9].

Variance Maximization: Components capturing maximal variance may not align with biologically relevant directions, particularly when technical artifacts introduce large variances [14].

Orthogonality: The constraint of orthogonal components may not reflect biological reality, where overlapping gene programs often operate simultaneously.

Sample Size Sensitivity: PCA results demonstrate sensitivity to sample composition, with rare cell types or conditions potentially underrepresented in the major components [14].

Extension to Supervised and Sparse PCA

Several PCA extensions address specific analytical challenges in genomics:

Supervised PCA incorporates response variables (e.g., clinical outcomes) to identify components associated with specific phenotypes, enhancing biological interpretability [9].

Sparse PCA introduces regularization to produce principal components with sparse loadings (many exact zeros), improving interpretability by associating each component with smaller, more biologically coherent gene sets [9].

Functional PCA extends the framework to time-course gene expression data, modeling temporal patterns in transcriptomic dynamics [9].

Variance, covariance, and eigen decomposition constitute the mathematical foundation enabling Principal Component Analysis to reduce the dimensionality of gene expression data while preserving biologically relevant information. The covariance matrix encodes the complete variance structure, while eigen decomposition extracts orthogonal directions of maximum variance ranked by importance. Successful application in transcriptomics requires careful attention to data preprocessing, component selection, and interpretation within biological context. While the first few principal components often capture major experimental conditions and batch effects, higher components may contain biologically meaningful patterns specific to particular tissues or conditions. Advanced implementations addressing sparsity, supervision, and nonlinear relationships continue to enhance the utility of this century-old technique for modern genomic research.

The N × P Matrix Format

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) has become an indispensable tool in the analysis of high-dimensional genomic data, particularly in gene expression studies where researchers routinely encounter datasets with tens of thousands of genes (features) measured across multiple samples (observations). The foundation of any successful PCA lies in the proper structuring of data into an N × P matrix format, where N represents samples and P represents features. This technical guide provides comprehensive methodologies for constructing, validating, and analyzing the N × P matrix within the context of gene expression research, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to extract biologically meaningful patterns from complex transcriptomic data while avoiding common analytical pitfalls.

In gene expression studies using technologies such as RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), the initial data processing steps (quality control, alignment, and feature counting) often yield a count matrix that forms the basis for all subsequent analyses [17]. The standard convention for structuring this data places samples as rows (N) and genes as columns (P) in what is termed the N × P matrix format [18]. This structure aligns with the mathematical framework of most statistical packages, where observations (samples) form the rows and variables (genes) form the columns. The fundamental challenge in genomics lies in the high-dimensional nature of this matrix, where P (number of genes, typically ~20,000) vastly exceeds N (number of samples, often in the tens or hundreds) [5], creating unique statistical challenges that PCA helps to address.

The N × P matrix format enables researchers to capture the complete transcriptomic landscape of their experimental system in a mathematical framework amenable to multivariate analysis. Each cell in the matrix contains the normalized expression value for a specific gene (column) in a particular sample (row), creating a comprehensive data structure that preserves the relationships between samples and genes [17] [19]. Proper construction of this matrix is critical, as variations in sample preparation, sequencing depth, and experimental conditions can introduce technical artifacts that may confound biological interpretation if not adequately addressed [20].

Data Preparation and Normalization Methods

Construction of the Count Matrix

The initial RNA-Seq data processing typically results in a count matrix where genes are represented as rows and samples as columns [17] [19]. To conform to the standard N × P format where rows are samples and columns are variables, this matrix must be transposed before PCA analysis. As detailed in the GENAVi tool implementation, the featureCounts function of the subread package is commonly used to generate the initial count data by counting reads that map to genomic features, accounting for alternate transcripts and collapsing them to gene level [17]. The resulting data frame typically includes gene identification information, chromosomal position, strand information, and gene length in addition to the expression counts across samples.

Table 1: Essential Components of a Properly Formatted N × P Matrix

| Component | Description | Example Format |

|---|---|---|

| Sample IDs | Unique identifiers for each biological sample | Sample1, Sample2, ..., SampleN |

| Gene IDs | Standardized gene identifiers | ENSG00000139618, ENSG00000284662, ... |

| Expression Values | Normalized counts or transformed values | 15.342, 28.901, 0.000, ... |

| Metadata | Experimental conditions, batches, or phenotypes | Treatment: Control vs. Treated |

Normalization and Transformation Techniques

Normalization is a critical preprocessing step that ensures comparability of expression values across samples with potential differences in sequencing depth and other technical variations. GENAVi provides multiple normalization approaches, each with distinct characteristics and applications [17]:

- Row Normalization: Resembles a t-score normalization, transforming the expression of each individual gene across all samples

- logCPM (Counts Per Million): Implemented from the edgeR package, calculates CPM values for every feature followed by log₂ transformation

- Variance Stabilizing Transformation (VST): From the DESeq2 package, stabilizes variance across the dynamic range of expression values

- Regularized Logarithmic Transformation (rlog): Also from DESeq2, applies regularized log transformation for datasets with small sample sizes

Table 2: Comparison of Normalization Methods for RNA-Seq Data

| Method | Package | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| logCPM | edgeR | Simple interpretation, handles sequencing depth differences | May not stabilize variance for low counts |

| VST | DESeq2 | Stabilizes variance across expression range, fast computation | Less optimal for very small sample sizes |

| rlog | DESeq2 | Optimal for small sample sizes, similar to log₂ for large counts | Computationally intensive for large datasets |

After normalization, data should be standardized to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one for each gene [21]. This standardization ensures that all variables (genes) contribute equally to the PCA analysis, regardless of their original expression levels or variability, preventing highly expressed genes from dominating the principal components simply due to their magnitude rather than biological importance.

Principal Component Analysis Implementation

Computational Framework for PCA

The mathematical foundation of PCA involves transforming the original variables (genes) into a new set of orthogonal variables called principal components (PCs) that capture decreasing amounts of variance in the data [21]. The implementation follows these computational steps:

- Standardization: The normalized expression matrix is centered and scaled such that each gene has a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1

- Covariance Matrix Calculation: Compute the covariance matrix representing relationships between all pairs of genes

- Eigenvalue Decomposition: Calculate eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the covariance matrix

- Component Selection: Select top components based on eigenvalues, which represent variance explained

For the high-dimensional data typical of gene expression studies (where P >> N), computational efficiency becomes crucial. The irlba package (Fast Truncated Singular Value Decomposition) provides both faster computation and better memory efficiency compared to standard singular value decomposition (SVD) for computing the largest singular vectors and values [18]. This approach is implemented in tools such as Seurat for single-cell RNA-seq data, where dimensionality is particularly challenging.

Determining Significant Components

A critical challenge in applying PCA to gene expression data is determining how many principal components to retain for downstream analysis. While traditional approaches often focus on the first 2-4 components, evidence suggests that biologically relevant information may be contained in higher components [5]. Several statistical approaches address this challenge:

- JackStraw Permutation Test: Implemented in Seurat, randomly permutes a subset of data and calculates projected PCA scores for 'random' genes, then compares these with observed PCA scores to determine statistical significance [18]

- Horn's Parallel Analysis: Compares eigenvalues from actual data with those from permuted data, retaining components where actual eigenvalues exceed those from permuted data [18]

- Information Ratio Criterion: Quantifies the distribution of information content between projected versus residual gene expression space using genome-wide log-p-values of gene expression differences [5]

The assumption of low intrinsic dimensionality in gene expression data has been challenged by research showing that tissue-specific information often remains in the residual space after subtracting the first three PCs [5]. The information content in higher components becomes particularly important when comparing samples within large-scale groups (e.g., between two brain regions or two hematopoietic cell types), where most information may be contained beyond the first few components.

Advanced Applications and Methodological Considerations

Robust PCA for Outlier Detection

In RNA-Seq data with limited biological replicates (typically 2-6 per condition), accurately detecting outlier samples presents significant challenges. Robust PCA (rPCA) methods address this limitation by using robust statistics to obtain principal components not influenced by outliers and to objectively identify anomalous observations [20]. Two particularly effective methods include:

- PcaHubert: Provides high sensitivity for outlier detection

- PcaGrid: Achieves the lowest estimated false positive rate, with demonstrated 100% sensitivity and specificity in controlled tests [20]

These methods overcome limitations of classical PCA (cPCA), where the first components are often attracted toward outlying points and may not capture the variation of regular observations. In comparative studies, rPCA methods have successfully detected outlier samples that cPCA failed to identify, leading to significant improvements in differential expression analysis [20].

Interactive Visualization and Analysis

Modern RNA-Seq analysis platforms such as DEBrowser and GENAVi provide interactive visualization capabilities that enable researchers to explore PCA results dynamically [17] [19]. These tools allow users to:

- Visualize any pair of principal components in interactive scatter plots

- Color samples by experimental conditions or batches

- Select subsets of data directly from plots for further investigation

- Dynamically update plots based on parameter changes

- Hover over data points to obtain detailed sample information

This interactive approach facilitates the identification of technical artifacts such as batch effects, which can then be addressed through appropriate normalization or batch correction methods [19]. The ability to iteratively visualize and refine the analysis based on PCA results significantly enhances the analytical process, particularly for researchers without extensive programming expertise.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for PCA of Gene Expression Data

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application in PCA Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality RNA | Ensure input material quality for sequencing |

| Stranded RNA-Seq Library Prep Kits | Construction of sequencing libraries | Generate count data for matrix formation |

| DESeq2 | Differential expression analysis | Provides VST and rlog normalization methods |

| edgeR | Differential expression analysis | Provides logCPM normalization method |

| rrcox R Package | Robust statistical methods | Implements PcaHubert and PcaGrid for outlier detection |

| irlba R Package | Fast truncated SVD | Efficient PCA computation for large matrices |

| GENAVi Web Application | Interactive analysis platform | GUI-based normalization, PCA, and visualization |

The proper implementation of the N × P matrix format provides the foundational framework for successful principal component analysis of gene expression data. By adhering to standardized procedures for data structuring, normalization, and computational analysis, researchers can extract biologically meaningful patterns from high-dimensional transcriptomic data. The integration of robust statistical methods with interactive visualization platforms has made sophisticated PCA approaches accessible to researchers without extensive bioinformatics training, potentially accelerating discovery in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Future methodological developments will likely address current limitations in capturing nonlinear relationships and improving interpretation of principal components in biological contexts. As single-cell technologies continue to produce increasingly large-scale datasets, the importance of efficient, robust PCA implementations will grow accordingly, maintaining the N × P matrix as a central component in the analysis of gene expression data.

Interpreting Principal Components as Linear Combinations

In the analysis of high-dimensional genomic data, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as a fundamental dimensionality reduction technique that transforms complex gene expression datasets into a more manageable set of representative variables [9]. This transformation is achieved through the construction of linear combinations of the original gene expressions, creating new variables known as principal components (PCs) [22]. In bioinformatics research, where datasets often contain thousands of genes measured across relatively few samples, PCA provides a powerful approach to overcome the "large d, small n" challenge that renders many standard statistical techniques inapplicable [9].

The core mathematical foundation of PCA lies in its ability to create these linear combinations that capture the maximum variance in the data while remaining orthogonal to one another [23]. For gene expression studies, this means that researchers can project high-dimensional gene expression data onto a reduced set of components that effectively summarize the key patterns of biological variation [9]. These components, often referred to as "metagenes" or "super genes" in genomic contexts, enable researchers to visualize sample relationships, identify underlying structures, and perform downstream analyses that would be computationally prohibitive or statistically unstable with the full gene set [9].

Mathematical Foundation of Principal Components

The Linear Combination Framework

At its core, each principal component represents a linear combination of the original variables (gene expressions), constructed to capture the direction of maximum variance in the data [23] [22]. Given a set of p genes, the first principal component (PC1) is defined as a weighted combination of the original variables:

- PC1 = w₁₁X₁ + w₁₂X₂ + ... + w₁ₚXₚ

- PC2 = w₂₁X₁ + w₂₂X₂ + ... + w₂ₚXₚ

where X₁, X₂, ..., Xₚ represent the standardized expressions of genes 1 through p, and the weights w₁₁, w₁₂, ..., w₁ₚ are chosen to maximize the variance captured by PC1 [22]. Each subsequent component is constructed under the constraint that it must be orthogonal to all previous components while capturing the next highest possible variance [23] [9].

The weights (w) in these linear combinations, known as loadings, indicate the contribution of each original gene to the principal component [22]. Genes with larger absolute loading values have a stronger influence on that particular component. The mathematical procedure for identifying these optimal weights involves computing the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the data's covariance matrix through singular value decomposition (SVD) [23] [9].

Geometric Interpretation

Geometrically, PCA can be understood as fitting a p-dimensional ellipsoid to the data, where each axis of the ellipsoid represents a principal component [23]. The principal components are essentially the directions of the axes of this ellipsoid, with the first principal component corresponding to the longest axis, the second principal component to the second longest, and so forth [23] [22]. The length of each axis is proportional to the variance captured by that component, quantified by its associated eigenvalue [22].

In the context of gene expression analysis, this geometric interpretation allows researchers to understand how samples cluster together in reduced-dimensional space based on their overall expression patterns. When samples project closely together along a principal component, they share similar expression profiles for the genes that contribute most strongly to that component [24].

PCA Applications in Genomics Research

Principal Component Analysis serves multiple critical functions in genomic studies, particularly in the analysis of high-throughput gene expression data from microarray and RNA-seq experiments [9]. The table below summarizes the primary applications of PCA in bioinformatics research:

Table 1: Applications of PCA in Gene Expression Analysis

| Application Area | Specific Use Cases | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Exploratory Analysis & Visualization | Projecting high-dimensional gene expressions onto 2D or 3D PCA plots [9] | Enables graphical examination of sample relationships and identification of potential outliers [25] |

| Clustering Analysis | Using principal components as input for sample or gene clustering algorithms [26] | Reduces noise by focusing on components capturing biological signal rather than technical variation |

| Regression Modeling | Employing PCs as covariates in predictive models for clinical outcomes [9] [5] | Solves collinearity problems and enables standard regression techniques with high-dimensional genomic data |

| Differential Expression | Visualizing group separations in PCA space to complement statistical testing [25] | Provides unsupervised validation of expression differences between experimental conditions |

| Survival Analysis | Utilizing PCs to stratify patients into risk groups based on expression profiles [27] | Captures coordinated gene expression patterns associated with clinical outcomes |

Beyond these standard applications, recent methodological advances have introduced non-standard implementations of PCA in genomics, including approaches that accommodate interactions among genes, pathways, and network modules [9]. For instance, researchers can conduct PCA on genes within predefined biological pathways and then use the resulting principal components to represent pathway-level effects in downstream analyses [5]. Similarly, PCA can be applied to genes within network modules to capture the effects of functionally related gene groups [23].

Experimental Protocol: PCA for Gene Expression Analysis

Data Preprocessing and Standardization

The initial critical step in performing PCA on gene expression data involves proper data preprocessing to ensure that all genes contribute equally to the analysis [22]. RNA-seq count data typically requires normalization to account for differences in sequencing depth and library composition between samples [24]. Common approaches include calculating size factors and normalizing counts using packages like DESeq2 [24]. Following normalization, gene expression values should be standardized to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one [22]. This step is crucial because PCA is sensitive to the variances of the initial variables, and without standardization, genes with larger expression ranges would dominate the resulting principal components [22].

Covariance Matrix and Eigen Decomposition

Once the data is properly standardized, the next step involves computing the covariance matrix to understand how variables vary from the mean with respect to each other [22]. This symmetric matrix (where p is the number of genes) contains the covariances associated with all possible pairs of genes, with the diagonal elements representing the variances of each individual gene [22]. The covariance matrix reveals the underlying correlation structure between genes, identifying redundant information that may exist due to co-regulated genes or shared biological pathways [22].

The core computational step of PCA involves performing eigen decomposition on this covariance matrix to identify the eigenvectors and eigenvalues [22]. The eigenvectors represent the directions of maximum variance (principal components), while the corresponding eigenvalues indicate the amount of variance carried by each component [22] [9]. This process is mathematically equivalent to singular value decomposition (SVD) of the standardized data matrix, which is the approach implemented in most computational tools [9].

Component Selection and Interpretation

Following eigen decomposition, researchers must determine how many principal components to retain for downstream analysis. The scree plot, which displays eigenvalues in descending order, provides a visual tool for this decision [24] [22]. Components before the "elbow" point in the scree plot typically represent meaningful biological signal, while those after primarily capture noise [24]. Alternatively, researchers can retain enough components to capture a predetermined percentage of total variance (e.g., 70-90%) [22].

Biological interpretation of principal components involves examining the gene loadings for each component [22]. Genes with the largest absolute loading values contribute most strongly to a given component. Researchers can then perform functional enrichment analysis on these high-loading genes to identify biological processes, pathways, or functions associated with each component [9].

Figure 1: PCA Workflow for Gene Expression Data

Case Study: PCA in Lung Cancer Transcriptomics

A practical application of PCA in genomic research can be found in a lung cancer study conducted by the Whitehead Institute and MIT Center for Genome Research [27]. This study aimed to identify subclasses of lung adenocarcinoma based on gene expression profiles from 125 tumor samples and 17 normal lung specimens, with each sample profiled using Affymetrix U95A arrays containing 12,625 probe sets [27].

In this analysis, researchers first filtered non-differentially expressed genes between cancer and normal groups, then applied PCA to the remaining genes [27]. The principal components derived from the gene expression data were used as covariates in survival models, replacing the original high-dimensional gene expressions [27]. This approach effectively addressed the correlation structure among genes while reducing dimensionality to a manageable number of components. The study demonstrated that PCA-based survival models could successfully stratify patients into distinct risk groups with significantly different survival outcomes [27].

This case highlights a key advantage of PCA in genomic analysis: the ability to capture coordinated gene expression patterns that might be biologically meaningful but difficult to detect when examining individual genes in isolation. By projecting correlated genes onto the same principal components, PCA effectively summarizes the activity of biological pathways or gene networks that collectively influence clinical phenotypes [27].

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for PCA in Gene Expression Studies

| Research Reagent | Function in PCA Workflow | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Normalization Algorithms | Adjust for technical variability in sequencing depth and library composition [24] | DESeq2 size factors, TPM normalization, RPKM/FPKM for RNA-seq [24] |

| Statistical Software | Perform covariance matrix calculation and eigen decomposition [9] | R (prcomp), SAS (PRINCOMP), SPSS (Factor), MATLAB (princomp) [9] |

| Visualization Packages | Create PCA score plots, scree plots, and biplots for result interpretation [25] | ggplot2 (R), matplotlib (Python), specialized RNA-seq visualization tools [25] |

| Gene Set Analysis Tools | Interpret PC biological meaning through functional enrichment of high-loading genes [9] | GSEA, DAVID, clusterProfiler for pathway and GO term analysis [9] |

Comparative Analysis of Dimensionality Reduction Methods

While PCA represents a foundational dimensionality reduction technique, researchers in genomics should be aware of alternative methods that may be more appropriate for specific data types or research questions. The table below compares PCA with two other commonly used ordination techniques:

Table 3: Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Methods for Genomics

| Characteristic | PCA | PCoA | NMDS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input Data | Original feature matrix (e.g., gene expression values) [26] | Distance matrix (e.g., Bray-Curtis, Jaccard) [26] | Distance matrix (e.g., Bray-Curtis, Jaccard) [26] |

| Distance Measure | Covariance/correlation matrix, assumes Euclidean structure [26] | Various ecological distances (Bray-Curtis, UniFrac) [26] | Rank-order relations, preserves ordinal relationships [26] |

| Underlying Model | Linear combinations of original variables [26] [22] | Linear projection of distance matrix [26] | Nonlinear, iterative optimization of rank orders [26] |

| Optimal Use Case | Linear data structures, feature extraction [26] | Beta-diversity analysis, ecological distances [26] | Complex datasets with nonlinear structures [26] |

| Application in Genomics | Gene expression analysis, identifying major patterns of variation [26] [9] | Microbial community analysis, beta-diversity visualization [26] | Complex gene expression patterns where linearity assumption fails [26] |

PCA is particularly well-suited for gene expression data, which often exhibits approximately linear relationships between variables and where the Euclidean distance underlying PCA provides a biologically meaningful measure of similarity [26]. However, for microbiome data or other ecological community analyses, PCoA (Principal Coordinate Analysis) with specialized distance metrics like Bray-Curtis or UniFrac may be more appropriate [26]. Similarly, when analyzing complex gene expression patterns where the linearity assumption may not hold, NMDS (Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling) offers a valuable alternative that preserves the rank-order of distances between samples [26].

Advanced PCA Extensions in Bioinformatics

Recent methodological advances have extended the standard PCA framework to address specific challenges in genomic data analysis. Sparse PCA incorporates regularization to produce principal components with sparse loadings, forcing many gene coefficients to zero and thereby enhancing interpretability by focusing on smaller gene subsets [9]. Supervised PCA incorporates phenotype information during the dimension reduction process, potentially improving the relevance of resulting components for predicting clinical outcomes [9]. Functional PCA extends the approach to time-course gene expression data, capturing dynamic patterns across multiple time points [9].

Another innovative application involves using PCA to study interactions between biological pathways [9]. Rather than conducting PCA on all genes simultaneously, researchers can perform separate PCA on genes within predefined pathways, then examine interactions between the principal components of different pathways [9]. This approach maintains biological interpretability while capturing higher-order relationships that might be missed in single-pathway analyses.

These advanced techniques demonstrate how the core concept of interpreting principal components as linear combinations continues to evolve to meet the analytical challenges of modern genomic research, maintaining PCA's relevance as a fundamental tool in the bioinformatics toolkit.

Visualizing High-Dimensional Data Through Projection

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a fundamental statistical technique for the unsupervised analysis of high-dimensional data, allowing researchers to summarize the information content of large datasets into a smaller set of "summary indices" called principal components [28]. In the field of genomic research, where gene expression datasets routinely contain measurements for thousands of genes across multiple samples, PCA provides an essential tool for visualizing overall data structure, identifying patterns, and detecting sample similarities or clusters without prior biological annotation [5]. This dimensionality reduction is crucial because gene expression data from microarrays or RNA-sequencing creates mathematical spaces with thousands of dimensions (genes), making direct visualization and analysis computationally challenging and often unintuitive [29].

The application of PCA to gene expression microarray data has revealed that the linear intrinsic dimensionality of global gene expression maps may be higher than previously reported. While early studies suggested that only the first three to four principal components contained biologically relevant information, more recent investigations indicate that significant biological information resides in higher-order components, especially for tissue-specific comparisons [5]. This refinement in understanding highlights the importance of properly executing and interpreting PCA within the research pipeline for drug development and basic biological discovery, where distinguishing true biological signal from technical noise is paramount.

Theoretical Foundation of PCA

Mathematical Principles

Principal Component Analysis operates on the fundamental principle of identifying the dominant directions of maximum variance in high-dimensional data through eigen decomposition of the covariance matrix [30]. Mathematically, given a standardized data matrix ( X ) with ( n ) observations (samples) and ( p ) variables (genes), PCA seeks to find a set of new variables (principal components) that are linear combinations of the original variables [31]. These components are uncorrelated and ordered such that the first component (( PC1 )) captures the maximum variance in the data, the second component (( PC2 )) captures the next highest variance subject to being orthogonal to the first, and so on [28].

The mathematical transformation involves solving the characteristic equation of the covariance matrix: [ \det(\Sigma - \lambda I) = 0 ] where ( \Sigma ) represents the covariance matrix, ( \lambda ) represents the eigenvalues, and ( I ) is the identity matrix [31]. The eigenvalues ( \lambda ) quantify the amount of variance captured by each principal component, while the corresponding eigenvectors define the direction of these components in the original feature space [30] [31]. The projection of the original data onto the principal component axes is achieved through: [ Y = X \times W ] where ( W ) contains the selected eigenvectors and ( Y ) represents the transformed data in the new subspace [31].

Signal vs. Noise in Dimensionality Reduction

In the context of PCA, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) provides a useful framework for understanding dimensionality reduction [30]. The "signal" represents the biologically relevant information stored in the spread (variance) of the data, while "noise" constitutes unexplained variation due to random factors or measurement error [30]. The objective of PCA is to maximize signal content and reduce noise by rotating the coordinate axes so they capture the maximum possible information content or variance [30].

In gene expression analysis, this distinction becomes critical when interpreting components. Studies on large heterogeneous microarray datasets (containing 5,000+ samples from hundreds of cell types and tissues) have shown that while the first few components often capture broad biological categories (e.g., hematopoietic cells, neural tissues), higher components may contain important tissue-specific information rather than merely noise [5]. This challenges the common assumption that components beyond the first three to four are necessarily irrelevant, suggesting instead that the biological dimensionality of gene expression spaces is higher than previously recognized [5].

PCA Workflow for Gene Expression Data

Preprocessing and Data Preparation

Table 1: Gene Expression Data Preprocessing Steps

| Step | Purpose | Common Methods | Impact on PCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missing Value Handling | Address incomplete data points | Removal or imputation (mean/median) | Prevents computational errors; maintains data integrity [29] |

| Data Filtering | Remove uninformative genes | Variance filters, entropy filters | Reduces noise; focuses on biologically relevant signals [29] |

| Standardization | Normalize feature scales | Z-score transformation (mean=0, SD=1) | Prevents dominance of highly expressed genes [30] [31] |

| Quality Control | Identify technical artifacts | Relative Log Expression (RLE) metrics | Minimizes technical bias in principal components [5] |

Before applying PCA, careful preprocessing of gene expression data is essential. The initial step involves filtering genes that do not show meaningful variation or expression. In a yeast gene expression dataset analyzing the metabolic shift from fermentation to respiration, researchers first removed spots marked 'EMPTY' and genes with missing values (NaN) [29]. Subsequent filtering steps typically include:

- Variance filtering: Removing genes with small variance over time using approaches like

genevarfilter, which retains genes with variance above a specific percentile (e.g., 10th percentile) [29]. - Low-value filtering: Eliminating genes with very low absolute expression values using functions like

genelowvalfilterwith appropriate thresholds (e.g., log2(3)) [29]. - Entropy filtering: Removing genes with low entropy profiles using tools like

geneentropyfilterto retain genes in higher percentiles (e.g., 85th percentile) [29].

Following filtering, standardization is critical. This involves transforming the data such that each gene has a mean of zero and standard deviation of one, calculated as ( z = \frac{(x - \mu)}{\sigma} ), where ( x ) is the expression value, ( \mu ) is the mean, and ( \sigma ) is the standard deviation [31]. This ensures that highly expressed genes do not dominate the PCA simply due to their larger numerical values [30] [31].

Core Computational Steps

The computational implementation of PCA involves several sequential steps that transform the preprocessed gene expression data into its principal components:

Covariance Matrix Computation: After standardization, compute the covariance matrix ( \Sigma = \frac{1}{n-1} X^T X ), where ( X ) is the standardized data matrix and ( n ) is the number of observations [31]. This symmetric matrix captures the pairwise covariances between all genes, representing how gene expression levels vary together across samples [30].

Eigen Decomposition: Calculate the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the covariance matrix [30]. The eigenvalues ( \lambda ) represent the amount of variance captured by each principal component, while the eigenvectors define the direction vectors of the new component axes [31]. This step essentially transforms the original covariance matrix into a new matrix where the diagonals contain the eigenvalues (variance explained) and off-diagonal elements become close to zero, indicating that the new axes capture all the information content [30].

Component Selection: Determine how many principal components to retain based on either the scree plot method (looking for an "elbow" point in the eigenvalue plot) or the variance explained criterion (selecting enough components to capture a desired percentage, e.g., 95%, of the total variance) [31]. In gene expression studies, the first two or three components typically explain between 36-90% of the total variance, with the exact percentage dependent on dataset heterogeneity [5] [29].

Data Projection: Project the original data onto the selected principal components by constructing a feature vector matrix ( W ) containing the chosen eigenvectors and transforming the original data ( X ) into the new subspace ( Y ) via ( Y = X \times W ) [31]. This creates a lower-dimensional representation of the data that retains most of the significant biological variance.

Experimental Design and Protocols

Case Study: Analysis of Yeast Diauxic Shift

A representative example of PCA application in gene expression analysis comes from a study of metabolic shifts in yeast published by DeRisi, et al. 1997 [29]. In this experiment, researchers used DNA microarrays to study temporal gene expression of almost all genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae during the diauxic shift from fermentation to respiration, with expression levels measured at seven time points [29].

The experimental protocol began with loading the dataset containing expression values (log2 of ratio of CH2DNMEAN and CH1DNMEAN) from the seven time steps, along with gene names and time measurement points. The initial dataset contained 6,400 genes, which was subsequently refined through multiple filtering steps [29]:

- Empty Spot Removal: Identification and removal of spots marked 'EMPTY' using string comparison functions (

strcmp), reducing the dataset to 6,314 genes [29]. - Missing Data Handling: Removal of genes with any NaN values using

isnanfunction, resulting in 6,276 genes [29]. - Variance Filtering: Application of

genevarfilterto remove genes with small variance over time (below the 10th percentile), yielding 5,648 genes [29]. - Low-Value Filtering: Implementation of

genelowvalfilterwith absolute value threshold of log2(3) to remove genes with very low expression, resulting in 822 genes [29]. - Entropy Filtering: Final filtering with

geneentropyfilterto remove genes with low entropy profiles (below 15th percentile), producing a final set of 614 informative genes [29].

After preprocessing, PCA was performed using the pca function, which computed the principal components, scores, and variances [29]. The analysis revealed that the first principal component accounted for 79.83% of the variance, while the second component explained an additional 9.59%, meaning the first two components together captured nearly 90% of the variance in the dataset [29].

Case Study: Large-Scale Human Tissue Analysis

Another influential application comes from analysis of large-scale human gene expression datasets. Lukk et al. (2016) performed PCA on a dataset of 5,372 samples from 369 different tissues, cell lines, and disease states hybridized on Affymetrix Human U133A microarrays [5]. This study demonstrated how sample composition significantly influences PCA results.

The experimental approach involved:

- Dataset Assembly: Compiling a comprehensive collection of gene expression samples from public repositories, carefully curating sample annotations [5].

- PCA Implementation: Performing principal component analysis on the normalized expression matrix.

- Component Interpretation: Correlating principal components with biological annotations and array quality metrics.

- Subset Analysis: Applying PCA to biologically relevant subsets (e.g., "brain subset" with samples from caudate nucleus, hypothalamus, frontal cortex, and cerebellum) to uncover additional structure [5].

A key finding was that the first three PCs separated hematopoietic cells, malignancy (proliferation), and neural tissues, respectively, explaining approximately 36% of the total variability [5]. The fourth PC in the original analysis correlated with an array quality metric (relative log expression, RLE), suggesting technical rather than biological variation [5].

Follow-up analysis with a larger dataset (7,100 samples from Affymetrix Human U133 Plus 2.0 platform) revealed that the fourth PC could capture biologically meaningful information (liver and hepatocellular carcinoma samples) when the dataset contained sufficient samples from these tissues [5]. This highlights how sample size effects strongly influence PCA results in gene expression studies.

Table 2: Variance Explained in Gene Expression PCA Studies

| Dataset | Sample Size | PC1 Variance | PC2 Variance | PC3 Variance | Cumulative Variance (PC1-3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Diauxic Shift [29] | 614 genes | 79.83% | 9.59% | 4.08% | 93.50% |

| Human Tissues (Lukk et al.) [5] | 5,372 samples | ~16% | ~12% | ~8% | ~36% |

| Human Tissues (Extended) [5] | 7,100 samples | Similar to Lukk et al. | Similar to Lukk et al. | Similar to Lukk et al. | ~36% |

Visualization and Interpretation Strategies

Creating Effective Visualizations

Visualization of PCA results enables researchers to identify patterns, clusters, and outliers in their gene expression data. The most common visualization approaches include:

- Score Plots: Scatter plots of the first two or three principal components (e.g., PC1 vs. PC2) that show how samples relate to each other in the reduced-dimensionality space [28] [29]. Samples with similar expression profiles appear closer together, while dissimilar samples are farther apart.

- Biplots: Combined visualizations that display both sample scores and variable loadings, allowing researchers to see which genes contribute most to the separation of samples along each component [31].

- Heat Maps with Dendrograms: Using functions like

clustergramto create heat maps of expression levels alongside dendrograms from hierarchical clustering, complementing PCA visualization [29]. - 3D Scatter Plots: Interactive three-dimensional plots of the first three principal components that can reveal clusters not apparent in two dimensions.

In the yeast diauxic shift data, plotting the first two principal components revealed two distinct regions in the data, corresponding to different expression program activations during the metabolic transition [29]. For the large-scale human tissue data, similar plots showed clear separation of hematopoietic, neural, and cell line samples in the first three components [5].

Interpreting Biological Meaning

Interpreting PCA output requires connecting mathematical components to biological reality. Effective interpretation strategies include:

- Component-Trait Correlation: Correlating principal component scores with sample annotations or phenotypic traits. In the Lukk et al. dataset, PC1 correlated with hematopoietic cells, PC2 with malignancy/proliferation, and PC3 with neural tissues [5].

- Gene Loading Analysis: Examining which genes have the strongest contributions (loadings) to each component. Genes with large absolute loadings for a particular component are those whose expression varies most along that component's axis [31].

- Information Localization: Determining whether specific biological information is concentrated in early or later components. Analysis of the "residual space" after removing the first three components showed that tissue-specific information often remains in higher components, particularly for comparisons within large-scale groups (e.g., between two brain regions or two hematopoietic cell types) [5].

- Reconstruction Validation: Computing reconstruction error ( \|X - \hat{X}\| ) where ( \hat{X} ) is the data reconstructed from principal components to ensure the PCA model retains most of the original data's variability [31].

A critical insight from gene expression PCA studies is that sample composition dramatically affects results. When the number of liver samples in a dataset was reduced to 60% or less of the original, the liver-specific component (PC4) disappeared, explaining why different studies might detect different numbers of "biologically relevant" components [5].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Expression PCA

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application in PCA Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Microarrays | Genome-wide expression profiling | Data generation: Measuring mRNA abundance for thousands of genes simultaneously [5] [29] |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality RNA from tissues/cells | Sample preparation: Ensuring input material integrity for reliable expression data [29] |

| Normalization Algorithms | Technical variation removal | Preprocessing: Correcting for technical artifacts before PCA [5] |

| Gene Filtering Tools | Selection of informative genes | Data reduction: Identifying genes with meaningful variation for inclusion in PCA [29] |