A Comprehensive Guide to RNA-seq Exploratory Analysis with DESeq2: From Raw Data to Biological Insight

This article provides a complete workflow for performing gene-level exploratory and differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data using the DESeq2 package in R/Bioconductor.

A Comprehensive Guide to RNA-seq Exploratory Analysis with DESeq2: From Raw Data to Biological Insight

Abstract

This article provides a complete workflow for performing gene-level exploratory and differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data using the DESeq2 package in R/Bioconductor. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the guide covers the foundational principles of count-based models, a step-by-step methodological pipeline from data import to result visualization, practical troubleshooting for common issues, and a comparative overview of alternative tools. By integrating foundational knowledge with practical application, this resource empowers users to conduct robust, reproducible transcriptomic analyses and confidently interpret results in the context of biomedical and clinical research.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Data Preparation for RNA-seq Analysis

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptome studies by providing a comprehensive method for profiling gene expression across the entire genome. This high-throughput technology enables researchers to not only quantify expression levels but also discover novel transcripts, identify alternative splicing events, and detect post-transcriptional modifications [1]. The fundamental objective of most RNA-seq experiments is to identify differentially expressed genes between biological conditions—such as treated versus untreated samples or mutant versus wild-type organisms—which provides crucial insights into cellular responses and disease mechanisms [2].

The typical RNA-seq workflow begins with RNA extraction from biological samples, followed by library preparation where RNA is fragmented and converted to cDNA with adapters ligated for sequencing. Libraries are then sequenced using platforms such as Illumina, producing millions of short reads [3]. These raw sequences undergo several computational steps including quality control, alignment to a reference genome, and quantification of reads mapping to genomic features, ultimately generating a count matrix where rows represent genes and columns represent samples [4] [5].

Fundamentals of Differential Expression Analysis

Differential expression analysis identifies genes whose expression levels change significantly between experimental conditions. This analysis must account for several unique characteristics of RNA-seq data: count-based output, dependence of variance on mean expression levels, and technical variability from sequencing depth and sample preparation [2]. The core statistical challenge involves distinguishing biological signal from technical noise when working with typically small numbers of replicates (often 3-6 per condition).

DESeq2 has emerged as one of the most widely used tools for this analysis, employing a negative binomial generalized linear model (GLM) to account for over-dispersion common in count data [6]. The method is cited thousands of times in the literature and remains actively maintained through Bioconductor, ensuring ongoing improvements and support [1] [2].

DESeq2 Workflow: From Count Data to Results

The DESeq2 analysis pipeline incorporates multiple steps that handle normalization, dispersion estimation, and statistical testing in an integrated framework.

Input Data Preparation

DESeq2 requires two primary inputs:

- Count matrix: A table of raw, non-normalized integer counts where rows correspond to genes and columns to samples

- Sample metadata: A table describing the experimental conditions for each sample, with row names matching column names in the count matrix [6]

Proper experimental design is crucial, with replication being particularly important. As noted in training materials, "RNA-seq experiments are performed with an aim to comprehend transcriptomic changes in organisms in response to a certain treatment" [5]. The design formula specification is critical, as it informs DESeq2 how to model counts based on the metadata variables.

Key Computational Steps

The DESeq2 workflow involves several automated steps when calling the DESeq() function:

- Estimation of size factors to control for differences in library depth using the median of ratios method [2]

- Estimation of gene-wise dispersions to model the relationship between mean expression and variance

- Fitting of a curve to the gene-wise dispersion estimates

- Shrinkage of dispersion estimates toward the fitted curve to improve accuracy for genes with low counts

- Fitting of the negative binomial GLM and performing statistical testing using the Wald test or likelihood ratio test [2]

Table 1: Key Steps in the DESeq2 Analysis Workflow

| Step | Purpose | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| Size Factor Estimation | Normalizes for library depth | estimateSizeFactors() |

| Dispersion Estimation | Models mean-variance relationship | estimateDispersions() |

| Model Fitting | Fits negative binomial GLM | nbinomWaldTest() |

| Results Extraction | Generates DE genes table | results() |

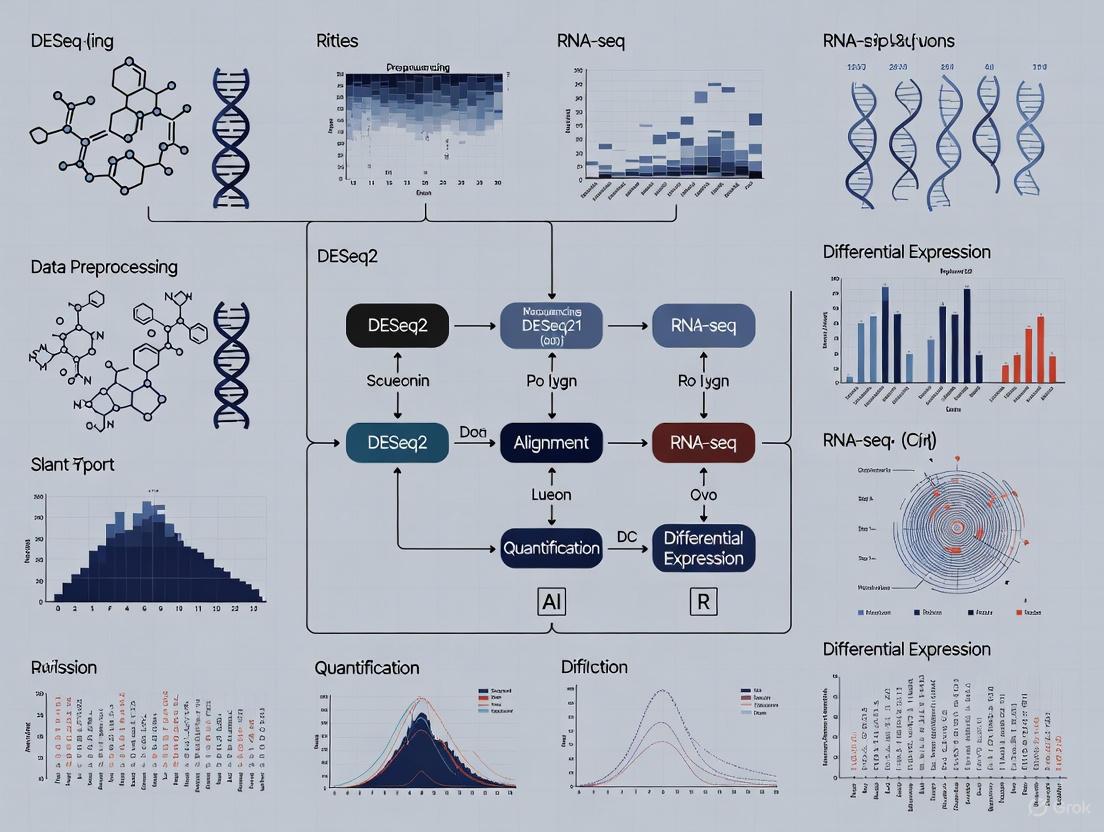

Visualization of the DESeq2 Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete DESeq2 analytical process from raw data to results interpretation:

Detailed Protocol: Differential Expression Analysis with DESeq2

Data Input and Pre-processing

Begin by installing and loading required packages:

Import count data and sample metadata. Critical attention must be paid to ensuring sample names consistency:

Pre-filtering is recommended to remove genes with minimal expression, reducing memory usage and improving performance:

Creating the DESeqDataSet and Specifying Design

Construct the DESeqDataSet object, which stores all experiment information:

The design formula is a critical component that specifies how counts depend on experimental variables. For basic two-group comparisons, the formula ~ condition is sufficient. For more complex designs with confounding variables, these should be included: ~ sex + age + treatment [2].

Running DESeq2 and Extracting Results

Execute the comprehensive DESeq2 analysis with a single command:

This function performs all analysis steps sequentially: size factor estimation, dispersion estimation, and statistical testing. Extract results using:

The results table includes base mean expression, log2 fold changes, standard errors, test statistics, p-values, and adjusted p-values.

Quality Control and Visualization

DESeq2 provides multiple visualization methods for quality assessment:

Statistical Framework of DESeq2

Normalization: Median of Ratios Method

DESeq2 employs a size factor normalization approach that accounts for differences in sequencing depth between samples. This method calculates for each sample a size factor as the median of the ratios of its counts relative to the geometric mean across all samples [2]. The approach is robust to large numbers of differentially expressed genes.

Dispersion Estimation and Shrinkage

The dispersion parameter (α) in DESeq2 models the relationship between mean expression and variance, addressing the mean-variance dependence in count data. DESeq2 uses shrinkage estimation to borrow information across genes, providing more reliable dispersion estimates, particularly for genes with low counts [2].

Hypothesis Testing

For standard pairwise comparisons, DESeq2 uses the Wald test to assess whether log2 fold changes are significantly different from zero. For more complex experimental designs, the likelihood ratio test (LRT) can be employed to test multiple factors simultaneously [2].

Advanced Experimental Designs

DESeq2 supports complex experimental designs beyond simple group comparisons:

Multi-factor Designs

When multiple variables may influence gene expression, these can be incorporated into the design formula:

This controls for batch effects while testing for condition-specific effects.

Interaction Terms

To test whether the effect of treatment differs between groups, interaction terms can be included:

Alternatively, a combined factor approach may be more interpretable:

Case Study: RNA-seq in Colorectal Cancer Research

A practical application of DESeq2 can be illustrated through a published dataset (E-GEOD-50760) investigating gene expression in colorectal cancer [6]. This study analyzed 54 samples from 18 individuals, with each contributor providing three tissue types: normal colon epithelium, primary colorectal cancer, and metastatic liver tumor.

The analysis followed this protocol:

This design appropriately accounts for paired samples from the same individuals while identifying tissue-specific expression patterns. The analysis revealed numerous differentially expressed genes involved in cancer progression and metastasis.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for RNA-seq Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Purpose and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Alignment Tools | HISAT2, STAR | Splice-aware alignment of RNA-seq reads to reference genomes |

| Quantification Tools | featureCounts, HTSeq | Generate count matrices from aligned reads |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2, edgeR | Statistical analysis of expression differences |

| Functional Analysis | g:Profiler, Gene Ontology | Biological interpretation of DE genes |

| Data Repositories | ENA, GEO, SRA | Public access to raw and processed data |

| Quality Control | FastQC, MultiQC | Assessment of read quality and preparation of reports |

| Reference Annotations | Ensembl, RefSeq, GENCODE | Genome annotations for read assignment |

Interpretation of Results and Biological Validation

Understanding DESeq2 Output

The results table from DESeq2 contains several key columns:

- baseMean: Average normalized counts across all samples

- log2FoldChange: Effect size estimate (log2 scale)

- lfcSE: Standard error of the log2 fold change

- stat: Wald test statistic

- pvalue: Raw p-value

- padj: Multiple testing adjusted p-value (Benjamini-Hochberg)

Genes with adjusted p-values below a threshold (typically padj < 0.05) are considered significantly differentially expressed.

Functional Interpretation

Following differential expression analysis, functional interpretation tools like g:Profiler and the Expression Atlas can identify enriched biological processes, molecular functions, and pathways among significant genes [7]. This step translates statistical findings into biological insights by connecting gene lists with known functions and pathways.

Methodological Considerations and Best Practices

Experimental Design Recommendations

- Include sufficient biological replicates (minimum 3, preferably more) to increase statistical power

- Randomize processing order to avoid batch effects

- Balance experimental groups across sequencing batches when possible

- Record all relevant metadata for potential inclusion in statistical models

Quality Control Metrics

Rigorous QC should be performed throughout the analysis pipeline:

- Sequence quality: Assess base quality scores, GC content, and adapter contamination

- Alignment metrics: Monitor mapping rates, ribosomal RNA alignment, and strand specificity

- Sample relationships: Verify that replicates cluster together in PCA plots

- Count distributions: Check for outliers and ensure appropriate dispersion estimates

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between key statistical concepts in DESeq2:

DESeq2 provides a comprehensive, statistically rigorous framework for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Its careful handling of count distribution characteristics, incorporation of sophisticated normalization methods, and flexibility for complex experimental designs have established it as a cornerstone tool in computational biology. When applied following established best practices for experimental design and quality control, DESeq2 enables researchers to reliably identify transcriptomic changes underlying biological processes and disease states, forming a critical component of modern genomics research.

The integration of DESeq2 into broader analysis workflows—from raw data processing to biological interpretation—empowers researchers to extract meaningful insights from transcriptomic data, accelerating discovery in fields ranging from basic biology to drug development.

Within the context of a broader thesis on using DESeq2 for RNA-seq exploratory analysis research, mastering the DESeqDataSet (DDS) is a fundamental step. This object serves as the central container for your RNA-seq dataset, holding the raw input data, intermediate calculations, and final results of a differential expression analysis [8] [9]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a thorough understanding of its structure and components is critical for conducting a robust and reproducible analysis. This document details the essential elements of the DESeqDataSet, provides protocols for its creation, and visualizes its role in the analytical workflow.

The Essential Components of a DESeqDataSet

The DESeqDataSet is an S4 class object that extends the SummarizedExperiment class from Bioconductor. It is designed to store all the necessary information for a differential expression analysis [8]. The table below summarizes its core components.

Table 1: Core Components of a DESeqDataSet Object

| Component | Description | Data Type | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count Matrix | The matrix of raw, un-normalized read counts [10]. | Integer matrix |

Primary input data; genes as rows, samples as columns. |

| Column Data | Metadata describing the experimental conditions of each sample [11]. | DataFrame |

Links samples to experimental groups (e.g., treatment, control). |

| Design Formula | A symbolic representation of the experimental design for statistical modeling [9]. | Formula |

Defines how counts depend on variables in colData (e.g., ~ condition). |

| Normalization Factors | Internal size factors for correcting library size and composition [10]. | Numeric matrix |

Used by DESeq2's internal normalization via the median-of-ratios method. |

| Dispersion Estimates | Gene-wise estimates of the dispersion, measuring the variance relative to the mean [10]. | Numeric vector |

Key parameter for the Negative Binomial model used in testing. |

| Model Results | Results of the differential expression testing, including log2 fold changes and p-values [8]. | DataFrame |

Stored in the rowData slot after running results(). |

Protocol: Constructing a DESeqDataSet from a Count Matrix

This protocol details the creation of a DESeqDataSet from a count matrix and sample metadata, a common starting point for many analyses.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Software for DESeq2 Analysis

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| R Environment | The programming language and console for executing analysis. |

| RStudio | An integrated development environment (IDE) for R. |

| DESeq2 Package | The Bioconductor package that performs differential expression analysis [8] [9]. |

| Count Quantification Tool | Software like featureCounts, HTSeq, or Salmon (with tximport) to generate the raw count matrix from sequence files [12]. |

| Sample Metadata File | A CSV or TSV file specifying the experimental group for each sample in the count matrix. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Load Packages and Data

Step 2: Verify Data Integrity Ensure the column names of the count matrix exactly match the row names of the metadata table.

Step 3: Create the DESeqDataSet

Use DESeqDataSetFromMatrix to construct the object.

Step 4: Pre-Filter Low-Count Genes This optional step removes genes with very few reads, reducing memory usage and improving performance.

Visualizing the DESeq2 Workflow and Data Object Structure

The following diagram illustrates the lifecycle of the DESeqDataSet object throughout a standard DESeq2 analysis, from creation to the extraction of results.

DESeq2 Analysis Workflow

The internal structure of the DESeqDataSet and its relationship to input files can be visualized as follows.

DESeqDataSet Object Structure

Critical Considerations for Experimental Design

The Design Formula

The design formula is a critical component that defines the statistical model. A simple formula like ~ condition tests for the effect of 'condition' while accounting for other factors. More complex designs, such as ~ batch + condition, can account for batch effects [9].

Pre-Filtering

Pre-filtering genes with low counts is recommended to reduce the object's memory size and increase the speed of downstream transformations and testing functions [9].

Factor Level Reference

By default, R orders factor levels alphabetically. To ensure the correct comparison (e.g., "control" vs. "treatment"), explicitly set the reference level.

Troubleshooting Common Data Object Issues

Table 3: Common Issues and Solutions When Creating a DESeqDataSet

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

Error: countData must be a matrix |

The count data is likely a data frame. | Use countdata <- as.matrix(countdata) to convert. |

Column names of countData do not match row names of colData |

Mismatch between sample names in the count matrix and metadata. | Use colnames(countdata) and rownames(metadata) to check and correct. |

| Model fails to converge | A problem with the design formula or too few replicates. | Simplify the design formula or check for complete separation in groups. |

results() returns all NA values |

The comparison specified does not match the factor levels in the design. | Verify factor levels with levels(dds$condition) and use the contrast argument in results(). |

The DESeqDataSet is the foundational data structure for any differential expression analysis with DESeq2. It seamlessly integrates raw data, sample metadata, and statistical parameters into a single, manageable object. A correct initial setup, with special attention to the count matrix, column data, and design formula, is paramount for the validity of all subsequent analytical steps. By following the protocols and guidelines outlined in this document, researchers can ensure their analysis is built upon a solid and reliable foundation.

Within the comprehensive framework of RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) research, differential gene expression (DGE) analysis stands as a fundamental objective for researchers and drug development professionals. The accuracy of this analysis hinges on the proper preparation and normalization of input data. Historically, workflows relied on read alignment and count assignment using alignment-based methods. However, the advent of fast, alignment-free quantification tools such as Salmon and Kallisto has revolutionized this initial step by providing transcript-level abundance estimates without generating large BAM files [13] [14]. These methods offer significant advantages in speed and reduced disk usage but present a new challenge: their output consists of estimated counts and abundances that require careful handling to be used effectively with count-based DGE tools like DESeq2 [13] [11].

The tximport and tximeta Bioconductor packages serve as the critical bridge between these modern quantification tools and downstream DGE analysis in R. Using these packages correctly is paramount because it ensures that the statistical models underlying DESeq2 are supplied with data that accounts for technical biases, such as changes in gene length across samples due to differential isoform usage [15] [16]. This guide provides detailed application notes and protocols for importing Salmon and Kallisto outputs, facilitating a robust and accurate exploratory analysis and differential expression testing within the broader context of an RNA-seq research thesis.

The Role of tximport and tximeta

The primary function of tximport is to import transcript-level abundance estimates from various software and summarize them to the gene-level, producing count matrices and normalizing offsets for use with DGE packages like DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom [15] [16]. This process offers several key benefits:

- Corrects for Gene Length Changes: It adjusts for potential changes in effective gene length across samples that can arise from differential isoform usage, ensuring that expression changes are not confounded by length variations [15] [16].

- Increases Sensitivity: By working at the transcript level initially, it avoids discarding fragments that can align to multiple genes with homologous sequence, thereby increasing the sensitivity of the analysis [15] [16].

- Computational Efficiency: It leverages the speed and computational efficiency of alignment-free quantifiers like Salmon and Kallisto, which skip the generation of large BAM files [13] [14].

The tximeta package extends the functionality of tximport by automatically adding rich annotation metadata (e.g., from GENCODE, Ensembl) to the created object, provided a commonly used transcriptome was employed [16]. This reduces manual error and enhances reproducibility.

Workflow Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for incorporating tximport or tximeta into an RNA-seq analysis pipeline, from raw data to a DESeq2 object ready for exploratory analysis and differential expression.

Materials and Reagents: The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table details the essential computational tools and data files required to execute the import and analysis protocol.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Import and Analysis

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salmon [13] | Software | Transcript-level quantification from RNA-seq data. | Fast, alignment-free, accuracy via bias correction models. |

| Kallisto [13] [11] | Software | Transcript-level quantification from RNA-seq data. | Pseudo-alignment, extremely fast, lightweight. |

| tximport [15] [16] | R/Bioconductor Package | Imports and summarizes transcript-level estimates. | Generates gene-level count matrices & offsets for DGE tools. |

| tximeta [16] | R/Bioconductor Package | Imports and annotates transcript-level data. | Automatic genomic annotation addition to summarized data. |

| DESeq2 [17] [18] | R/Bioconductor Package | Differential gene expression analysis. | Models count data using a negative binomial distribution. |

| Transcriptome [19] | Reference Data | A collection of all known transcript sequences for an organism. | Serves as the reference for Salmon/Kallisto (e.g., GENCODE, Ensembl). |

| Annotation File (.GTF/.GFF) [19] | Reference Data | Describes the coordinates and relationships of transcripts and genes. | Required for genome indexing and creating the tx2gene table. |

| tx2gene Table [15] [16] | Lookup Table | Maps transcript identifiers to their corresponding gene identifiers. | Crucial for tximport to summarize transcript-level data to the gene-level. |

Detailed Methodologies

Preparing thetx2geneLookup Table

A critical prerequisite for gene-level summarization is a two-column lookup table that associates transcript identifiers with parent gene identifiers. This tx2gene data frame must have the transcript ID as the first column and the gene ID as the second [15] [16].

Protocol:

- Obtain Annotation File: Download a gene transfer format (.GTF) file from a source like ENSEMBL or UCSC that corresponds to the reference transcriptome used for quantification [19].

- Generate the Table in R: Use Bioconductor annotation packages to create the table programmatically. For an Ensembl transcriptome, the

ensembldbpackages are recommended. The following code provides an example using aTxDbobject: - Verify the Table: Inspect the first few rows of the

tx2genedata frame to ensure it is correctly formatted.

Importing Quantification Data withtximport

The core import functionality is handled by the tximport() function. The protocol differs slightly between Salmon and Kallisto, primarily in the type argument and the file paths.

Protocol for Salmon Output:

- Set Up File Paths: Create a named vector of file paths pointing to the

quant.sffiles for each sample. - Run

tximport: Execute the import function with the correct arguments.

Protocol for Kallisto Output:

- Set Up File Paths: Point the vector to the Kallisto

abundance.h5files. - Run

tximport: Specifytype = "kallisto".

The resulting txi object is a list containing several matrices at the gene level: abundance (TPM), counts (estimated counts), length (effective gene lengths), etc. [15] [16].

Integrating with DESeq2 for Exploratory Analysis

With the txi object created, you can now construct a DESeqDataSet, which is the central data structure for analysis with DESeq2 [17].

Protocol:

- Prepare Sample Metadata: Load a table (

colData) that describes the experimental conditions of each sample. The row names of this table must match the names of thefilesvector used intximport. - Create DESeqDataSet: Use the

DESeqDataSetFromTximport()function, which automatically uses thetxi$countsmatrix and incorporates the gene length information as normalization offsets to correct for potential gene length biases [17] [15]. - Proceed with Standard DESeq2 Workflow: The

ddsobject is now ready for the standard DGE analysis workflow, which includes exploratory analysis such as data transformation and visualization.

Data Presentation and Interpretation

Comparison of Import Methods

The following table summarizes the key parameters and outputs for the different import strategies, providing a clear guide for researchers to choose the appropriate method.

Table 2: Comparison of tximport/tximeta Functionality for Salmon and Kallisto

| Aspect | tximport | tximeta |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | General import, custom transcriptomes. | Automated annotation for common transcriptomes (GENCODE, Ensembl). |

Input type for Salmon |

type = "salmon" |

type = "salmon" |

Input type for Kallisto |

type = "kallisto" |

type = "kallisto" |

| Required Lookup Table | tx2gene (must be supplied by user). |

tx2gene (can be inferred automatically). |

| Output Object | Simple list of matrices. | SummarizedExperiment with rich rowRanges annotation. |

| Downstream DESeq2 Input | DESeqDataSetFromTximport(txi, ...) |

DESeqDataSetFromTximport(se, ...) or makeDGEList(se) for edgeR. |

| Key Advantage | Flexibility with any transcriptome. | Enhanced reproducibility and automated metadata attachment. |

Advanced Configuration Options

The tximport function provides advanced arguments to handle specific analytical scenarios.

Table 3: Key Advanced Arguments in tximport

| Argument | Default | Alternative Options | Effect and Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

countsFromAbundance |

"no" |

"scaledTPM", "lengthScaledTPM", "dtuScaledTPM" |

Generates counts from abundances. Use "no" for standard DGE with an offset; "scaledTPM" or "lengthScaledTPM" produce length-corrected counts where an offset is not needed [15] [16]. |

txOut |

FALSE |

TRUE |

When TRUE, skips gene-level summarization and returns transcript-level matrices. Essential for differential transcript usage (DTU) analysis [17] [16]. |

ignoreTxVersion |

FALSE |

TRUE |

Ignores the version suffix (e.g., .1) on transcript identifiers. Useful if versions differ between quantification and annotation. |

ignoreAfterBar |

FALSE |

TRUE |

Ignores part of the identifier after a | bar, a common feature in GENCODE FASTA headers. |

The tximport and tximeta packages are indispensable tools for modern RNA-seq analysis pipelines that utilize fast quantification software like Salmon and Kallisto. By correctly following the protocols outlined in this guide—preparing the tx2gene lookup table, importing data with the appropriate type argument, and leveraging the DESeqDataSetFromTximport function—researchers can ensure their data is properly structured and normalized for all subsequent analysis. This workflow not only capitalizes on the speed of alignment-free quantification but also robustly accounts for technical factors like gene length and composition bias, laying a solid foundation for statistically sound exploratory analysis and differential gene expression discovery within a DESeq2 framework. This rigorous approach to data import is a critical first step in a reproducible RNA-seq research project, directly contributing to the reliability and integrity of the biological insights generated.

In differential expression (DE) analysis with DESeq2, the statistical testing of whether gene expression differs between experimental conditions relies not only on the count data but fundamentally on the accompanying sample metadata [20]. The sample table and the design formula form the critical link between the raw quantitative data and the biological conclusions, formally defining the experimental groups and covariates for statistical modeling [21]. Proper construction of these elements is a prerequisite for a statistically sound and biologically interpretable analysis. Errors in metadata specification are a common source of failure in RNA-seq studies, as they can lead to incomplete or incorrect models, producing misleading results [22]. This protocol details the creation of effective sample tables and design formulas, framed within the context of a DESeq2 workflow for exploratory RNA-seq research.

Constructing a Comprehensive Sample Table

The sample table is a data frame that uniquely identifies each sequencing library and describes all relevant experimental conditions and batch variables.

Essential Components and Structure

A sample table must contain a unique identifier for each sample and all known factors that could systematically affect gene expression. The following table outlines the core columns required in a minimal sample table for DESeq2.

Table 1: Essential Columns for a DESeq2 Sample Table

| Column Name | Description | Data Type | Example Entry |

|---|---|---|---|

sampleName |

Unique identifier for the sample. | character |

"SRR479052", "Patient_1" |

fileName |

Path to the corresponding count or BAM file. | character |

"SRR479052.bam" |

condition |

The primary biological condition of interest. | factor |

"Control", "DPN" |

treatment |

Another major experimental factor (if applicable). | factor |

"Control", "OHT" |

time |

Time point of sample collection. | factor or numeric |

"24h", "48h" |

batch |

Technical batch factor (e.g., sequencing lane). | factor |

"Batch1", "Batch2" |

A properly constructed sample table, as derived from the parathyroidSE package, should resemble the following [23]:

Key Considerations for Sample Table Design

- Replication: The number of biological replicates is a crucial design factor. Power analysis should be performed before sequencing to determine the number of replicates needed to detect effect sizes of biological interest with sufficient statistical power [22].

- Randomization: To avoid confounding technical biases with biological effects, the processing of samples (e.g., RNA extraction, library preparation) should be randomized across experimental groups [22].

- Factor Levels: In R, the base level for any factor is set to the first level in alphabetical order by default. Since the results in DESeq2 will compare other groups against this base level, it is critical to set it intentionally. For example, to set "Uninfected" as the baseline for a "Status" factor, you would use

mutate(Status = fct_relevel(Status, "Uninfected"))[21].

Defining the Design Formula

The design formula specifies the linear model that DESeq2 will use to analyze the data. It tells DESeq2 which variables from the sample table should be used to model the counts.

Formula Syntax and Principles

The design formula uses standard R formula syntax and is provided to DESeq2 during data object construction [21]. The formula always starts with a tilde (~), followed by the model variables.

- Simple Design: For an experiment with only one condition, the formula is

~ condition[21]. - Multifactor Design: For multiple variables, for example, condition and batch, the formula would be

~ batch + condition. The order can matter if the variables are not independent; including batch effects in the model helps to control for their influence and increases the sensitivity for detecting the primary biological effect [20]. - Interaction Terms: To test if the effect of one factor depends on another level of a second factor, an interaction term can be included:

~ genotype + treatment + genotype:treatment.

Practical Application: Building the DESeqDataSet

The sample table and design formula are integrated when creating the DESeqDataSet object, the core data structure for DESeq2. This can be done from a count matrix or directly from tximport output [21].

A Protocol for Experimental Design and Metadata Setup

This section provides a step-by-step workflow for researchers to define their experimental model and initialize a DESeq2 analysis.

Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Pre-Sequencing Planning. Before preparing libraries, define all biological and technical factors. Ensure adequate biological replication and plan for randomization of sample processing to prevent batch effects from confounding the primary condition [22].

Step 2: Construct the Sample Table. After sequencing and quantification, compile all metadata into a data frame in R, as detailed in Section 2.1. Verify that the sampleName and fileName columns accurately link each sample to its corresponding quantitative data file [23].

Step 3: Define the Statistical Model. Formulate the design formula based on the experimental question. Start with a simple model containing the primary condition of interest. Only add other variables (like batch) if they are known to account for significant variation [20] [21].

Step 4: Set Factor Levels. Explicitly set the reference (base) level for all categorical factors in the sample table to ensure that the resulting log2 fold changes are biologically intuitive (e.g., "Control" vs. "Treated") [21].

Step 5: Create and Validate the DESeqDataSet. Use the DESeqDataSetFromTximport() or DESeqDataSetFromMatrix() function to create the DDS object. Crucially, check that the order of the samples in the colData (sample table) matches the order of the columns in the count matrix [21].

Step 6: Run the DESeq2 Pipeline. After creating and checking the DDS object, perform the standard DESeq2 analysis: estimation of size factors, dispersion estimation, and model fitting using the DESeq() wrapper function [21].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in the process of designing an experiment and setting up metadata for DESeq2.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Software and Packages for RNA-seq Differential Expression Analysis

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 [23] [20] | Differential expression analysis | Statistical modeling of count data, hypothesis testing, and results generation. |

| tximport [21] | Import transcript-level quantifications | Streamlines the import of abundance estimates from tools like Salmon into DESeq2. |

| GenomicAlignments [23] | Read counting | The summarizeOverlaps function generates count matrices from BAM files. |

| GenomicFeatures [23] | Gene model management | Used to create transcript databases from GTF files for read counting. |

| STAR [24] | Read alignment | A splice-aware aligner for mapping RNA-seq reads to a reference genome. |

| Salmon [24] | Expression quantification | Provides fast and accurate transcript-level quantification with bias correction. |

| nf-core/rnaseq [24] | Automated pipeline | A portable, community-maintained workflow for comprehensive RNA-seq data processing. |

Within the broader context of employing DESeq2 for RNA-seq exploratory analysis research, the initial quality assessment (QA) of raw count data represents a critical first step in ensuring analytically sound and biologically valid conclusions. This initial QA phase focuses on evaluating two fundamental properties of the dataset: raw count distributions across features and overall library sizes per sample. These metrics provide crucial insights into technical variability, potential biases, and overall data quality before proceeding with sophisticated statistical modeling in DESeq2.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling genome-wide quantification of RNA abundance with high sensitivity and accuracy [25] [26]. Unlike earlier methods such as microarrays, RNA-seq provides more comprehensive transcriptome coverage, finer resolution of dynamic expression changes, and improved signal-to-noise ratios [25]. The reliability of downstream differential expression analysis, including those performed with DESeq2, depends strongly on thoughtful experimental design and rigorous quality assessment at every processing stage [25] [27].

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for evaluating raw count distributions and library sizes, incorporating visualization techniques and quantitative metrics that serve as prerequisites for robust differential expression analysis using DESeq2.

Theoretical Foundations

Understanding Raw Count Data

RNA-seq data analysis begins with converting sequenced reads into a count matrix where rows typically represent genes or transcripts and columns represent samples [25] [28]. Each value in this matrix indicates the number of sequencing reads (for single-end sequencing) or fragments (for paired-end sequencing) that have been unambiguously assigned to a particular genomic feature in a specific sample [28].

The raw count matrix generated through alignment and quantification steps serves as the fundamental input for DESeq2 analysis [6] [28]. It is crucial that these values represent actual counts rather than normalized values, as DESeq2's statistical model relies on the count-based nature of the data to properly assess measurement precision and account for library size differences internally [28].

Importance of Library Size Assessment

Library size, defined as the total number of sequenced reads or fragments per sample after alignment, varies across samples due to technical rather than biological reasons [25]. These differences arise from variations in sequencing depth, RNA input quality, and efficiency of library preparation steps [25] [29]. During initial QA, researchers must evaluate whether library sizes are sufficiently large and comparable across samples, as insufficient sequencing depth can reduce sensitivity for detecting differentially expressed genes, particularly those with low expression [25] [30].

Characteristics of Raw Count Distributions

RNA-seq count data typically exhibits a highly skewed distribution with a majority of genes showing low counts and a minority with very high counts [25]. This distribution pattern reflects biological reality but must be assessed for technical artifacts that could compromise downstream analysis. Understanding the expected distribution helps identify potential issues such as dominance by highly expressed genes, batch effects, or failed libraries that might require additional normalization or sample exclusion [25] [31].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between key components of RNA-seq initial quality assessment:

Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential computational tools for RNA-seq quality assessment

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in QA |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 [6] [28] | Differential expression analysis | Create DESeqDataSet object for QA, calculate size factors, and assess library sizes |

| FastQC [27] | Sequence quality control | Evaluate raw read quality before alignment |

| R/Bioconductor [28] | Statistical computing environment | Provide infrastructure for count data manipulation and visualization |

| HISAT2 [32] | Read alignment | Map reads to reference genome/transcriptome |

| featureCounts [32] | Read quantification | Generate raw count matrix from aligned reads |

| SAMtools [25] | Alignment processing | Process and quality check aligned reads |

Data Requirements

The initial QA process requires two primary data components:

Raw Count Matrix: A table containing non-normalized integer counts of sequencing reads/fragments assigned to genomic features (genes or transcripts) for each sample [28]. These values must not be pre-normalized for sequencing depth or library size to maintain the count-based properties required by DESeq2's statistical model [28].

Sample Metadata: A data frame linking sample identifiers to experimental variables (e.g., treatment conditions, batch information, replicate groups) [6]. This metadata is essential for interpreting patterns observed during QA in the context of the experimental design.

Methodology

Data Import and Preprocessing

Begin by importing the raw count matrix and sample metadata into R, then creating a DESeqDataSet object, which serves as the primary container for the count data and intermediate calculations in DESeq2 [6]:

Basic pre-filtering is recommended to remove genes with minimal expression, which reduces dataset size and improves computational efficiency without compromising biological information [6]:

Library Size Calculation and Evaluation

Library sizes are calculated as the sum of all counts for each sample. These values should be evaluated for consistency across the experiment:

Table 2: Recommended library size guidelines for different RNA-seq applications

| Experiment Type | Recommended Reads per Sample | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gene expression profiling | 5-25 million | Sufficient for highly expressed genes; enables high multiplexing [30] |

| Standard differential expression | 30-60 million | Captures global expression patterns and some splicing information [30] |

| Comprehensive transcriptome analysis | 100-200 million | Required for novel transcript assembly and in-depth analysis [30] |

| Targeted RNA sequencing | ~3 million | Appropriate for focused gene panels [30] |

| Small RNA analysis | 1-5 million | Varies by tissue type [30] |

Assessment of Count Distributions

Evaluate the distribution of counts across genes for each sample using summary statistics and visualization:

The distribution of raw counts typically follows a negative binomial distribution, which accounts for the over-dispersion common in count data compared to a Poisson distribution [27] [6].

Data Analysis and Visualization

Library Size Visualization

Create visualizations to assess library size distribution across samples:

Significant variations in library sizes (e.g., greater than 3-fold differences) may indicate technical issues that require attention before proceeding with differential expression analysis [25].

Count Distribution Visualization

Visualize the distribution of counts using boxplots or violin plots:

This visualization helps identify samples with unusual distributions that might indicate technical problems.

Sample Similarity Assessment

Examine overall similarity between samples based on count distributions:

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process for initial quality assessment of RNA-seq data:

Troubleshooting and Quality Flags

Identifying Common Issues

During initial QA, several common issues may emerge that require attention before proceeding with DESeq2 analysis:

- Extreme library size variations: Samples with library sizes less than 50% of the median may indicate failed libraries and should be investigated further [25] [32].

- Excessive zero counts: An unusually high proportion of genes with zero counts in specific samples may indicate technical problems with those samples [25].

- Batch effects: Systematic differences in count distributions correlated with processing batches rather than biological conditions may require batch correction approaches [31].

- Outlier samples: Samples that cluster separately from their experimental groups in distance metrics may need to be excluded or investigated further [18].

Quality Thresholds and Decision Points

Table 3: Quality assessment thresholds and recommended actions

| Quality Metric | Acceptable Range | Concerning Range | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library size variation | < 3-fold difference | > 3-fold difference | Investigate technical causes; consider additional normalization [25] |

| Percentage of zero counts | < 50% of genes | > 50% of genes | Check RNA quality and library preparation [25] |

| Sample clustering | Groups by experimental condition | Groups by batch or other non-biological factors | Consider batch correction or covariate adjustment [31] |

| Alignment rate | > 70% | < 50% | Exclude sample from analysis [32] |

Rigorous initial quality assessment of raw count distributions and library sizes establishes a crucial foundation for all subsequent RNA-seq analyses using DESeq2. By systematically evaluating these fundamental data properties, researchers can identify technical artifacts, ensure data quality, and make informed decisions about appropriate normalization strategies and analytical approaches. This protocol provides a comprehensive framework for conducting these essential QA checks, supporting the generation of robust and reproducible results in transcriptomic studies.

The insights gained from this initial assessment directly inform the next steps in the DESeq2 workflow, including data normalization, dispersion estimation, and statistical testing for differential expression. Through careful implementation of these QA procedures, researchers can maximize the reliability of their biological interpretations while minimizing the risk of technical confounders influencing their conclusions.

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the predominant technology for profiling transcriptome-wide gene expression, generating vast amounts of count-based data that present unique statistical challenges. The analysis of this data requires specialized methods that properly account for its distinct characteristics: inherent discreteness, non-normality, and a dependence between variance and mean expression levels [33] [34]. Early approaches to differential expression analysis often relied on statistical models assuming a Poisson distribution. However, this assumption proves problematic for biological data because the Poisson model requires that the variance equals the mean, an condition rarely met in practice due to both technical variability and genuine biological heterogeneity between replicates [34] [35]. This phenomenon, where the observed variance exceeds the mean, is termed "overdispersion" and must be properly accounted for to avoid inflated false discovery rates and unreliable statistical inference.

DESeq2 addresses these challenges through a comprehensive statistical framework built upon the negative binomial distribution, which incorporates a dispersion parameter to model the variance as a function of the mean [33]. This approach enables more accurate modeling of count data by explicitly accommodating the overdispersion typical of RNA-seq experiments. The methodology further employs sophisticated shrinkage estimation techniques that stabilize both dispersion and fold-change estimates by borrowing information across genes, thereby improving the reliability of differential expression calls, particularly in studies with limited sample sizes [33]. This combination of robust statistical modeling and information sharing across features makes DESeq2 particularly powerful for the small sample sizes common in genomic research, where typical experiments may include as few as three to six replicates per condition [2] [33].

The Negative Binomial Distribution as a Model for RNA-seq Counts

Mathematical Foundation

The negative binomial distribution serves as the cornerstone of DESeq2's statistical framework, providing a flexible model for count data that adequately captures the overdispersion observed in RNA-seq experiments. The distribution is parameterized by two values for each gene: the mean expression level (μ) and the dispersion parameter (α), which quantifies the extent to which the variance exceeds the mean [33]. The relationship between these parameters is defined by the variance function: Var(K) = μ + αμ², where K represents the observed count data [33]. This quadratic relationship between variance and mean effectively addresses the limitation of the Poisson distribution, which assumes Var(K) = μ, a condition rarely satisfied in biological data due to both technical variability and genuine biological heterogeneity between replicates [34].

The dispersion parameter (α) plays a crucial role in the model, with its magnitude directly influencing the variance of the distribution. When α = 0, the negative binomial model reduces to the Poisson distribution, but with α > 0, the variance increases proportionally to the square of the mean [33] [35]. This relationship accurately reflects the behavior of RNA-seq data, where highly expressed genes typically demonstrate greater absolute variability than lowly expressed genes, while maintaining a lower coefficient of variation (the ratio of standard deviation to mean) [2]. The coefficient of variation for a gene's counts is given by √α, meaning that a dispersion value of 0.01 corresponds to 10% variation around the mean expected across biological replicates [2].

Comparative Advantages Over Alternative Distributions

The selection of an appropriate statistical distribution is critical for accurate differential expression analysis. The table below compares the negative binomial distribution with other potential models for count data:

Table 1: Comparison of Statistical Distributions for RNA-seq Count Data

| Distribution | Parameters | Variance-Mean Relationship | Suitability for RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poisson | λ (mean) | Var = μ | Poor - assumes no biological variability |

| Binomial | n (trials), p (success probability) | Var = np(1-p) | Poor - assumes fixed number of trials |

| Geometric | p (success probability) | Var = (1-p)/p² | Limited - special case of NB |

| Negative Binomial | μ (mean), α (dispersion) | Var = μ + αμ² | Excellent - accounts for overdispersion |

The Poisson distribution's fundamental limitation for RNA-seq data analysis stems from its inability to account for the biological variability that persists even between technical replicates of the same sample [34]. While the binomial distribution models discrete outcomes, it assumes a fixed number of trials, making it inappropriate for count data without a theoretical upper bound. The negative binomial distribution effectively generalizes both the Poisson and geometric distributions, offering the flexibility needed to model the overdispersed nature of genomic count data while maintaining mathematical tractability for statistical inference [34] [35].

The DESeq2 Workflow: From Raw Counts to Differential Expression

Comprehensive Analysis Pipeline

The DESeq2 package implements a sophisticated multi-step workflow that transforms raw count data into robust differential expression results. The complete process integrates normalization, parameter estimation, and statistical testing into a cohesive analytical framework, with each step addressing specific challenges in RNA-seq data analysis. The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the DESeq2 workflow:

Normalization: Accounting for Sequencing Depth and Composition

The initial step in the DESeq2 workflow addresses the critical issue of library size normalization, which ensures that count comparisons between samples are not confounded by differences in sequencing depth or RNA composition [36]. DESeq2 employs the median-of-ratios method, which calculates sample-specific size factors without relying on a reference sample [36] [33]. This method operates under the assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed, making it robust to situations where a small subset of genes shows extreme expression differences [36].

The normalization process involves three key steps. First, DESeq2 creates a pseudo-reference sample for each gene by calculating the geometric mean across all samples [36]. Second, it computes the ratio of each sample to this pseudo-reference, generating a distribution of ratios for each sample. Third, the size factor for each sample is derived as the median of these ratios, excluding genes with zero counts in any sample [36]. The mathematical representation of this process for a count K_ij of gene i in sample j is:

Normalized Count = Kij / sj

where s_j represents the size factor for sample j [36] [33]. This normalization approach effectively accounts for both differences in sequencing depth and RNA composition, addressing the limitation of simple counts-per-million normalization methods that can be skewed by highly expressed genes [36].

Table 2: Comparison of Normalization Methods for RNA-seq Data

| Method | Accounted Factors | Recommended Use | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Sequencing depth | Between replicates of same group | Not for DE analysis |

| TPM | Sequencing depth, Gene length | Within sample comparisons | Not for between-sample DE |

| RPKM/FPKM | Sequencing depth, Gene length | Within sample comparisons | Not comparable between samples |

| DESeq2 Median-of-Ratios | Sequencing depth, RNA composition | DE analysis, between samples | Not for within sample comparisons |

| edgeR TMM | Sequencing depth, RNA composition, Gene length | DE analysis, within and between | More complex computation |

Dispersion Estimation and Shrinkage

The accurate estimation of dispersion parameters represents one of DESeq2's most significant methodological advances. In RNA-seq experiments with small sample sizes, gene-wise dispersion estimates derived solely from a handful of replicates are inherently unreliable due to high stochastic variability [33] [35]. DESeq2 addresses this challenge through a sophisticated shrinkage approach that leverages information across the entire dataset to produce more stable and accurate estimates [33].

The dispersion estimation process follows a three-step procedure. First, gene-wise dispersion estimates are calculated for each gene using maximum likelihood estimation [2] [33]. Second, DESeq2 fits a smooth curve to model the relationship between dispersion and mean expression across all genes, capturing the overall trend where dispersion typically decreases with increasing expression levels [33]. Third, the gene-wise estimates are shrunk toward the curve using an empirical Bayes approach, with the strength of shrinkage determined by both the variability of gene-wise estimates around the curve and the number of replicates available [33]. This approach effectively balances gene-specific information with the overall trend observed across all genes, resulting in more reliable dispersion estimates particularly for genes with low counts or few replicates [33].

The shrinkage process incorporates an important safeguard: when a gene's dispersion estimate lies more than two residual standard deviations above the curve, DESeq2 uses the gene-wise estimate rather than the shrunken value [33]. This prevents excessive shrinkage for genes that genuinely exhibit unusually high variability, ensuring that biological heterogeneity is not artificially suppressed in the statistical model.

Experimental Protocols for Differential Expression Analysis

Comprehensive DESeq2 Analysis Workflow

Implementing a robust differential expression analysis requires careful attention to both computational procedures and experimental design considerations. The following protocol outlines the complete workflow for analyzing RNA-seq count data using DESeq2, from data preparation through interpretation of results:

1. Input Data Preparation

- Obtain a count matrix where rows represent genes, columns represent samples, and values contain raw (un-normalized) read counts [9] [37].

- Prepare a metadata table with sample information including experimental conditions, batch effects, and other relevant covariates [6] [37].

- Ensure that column names in the count matrix exactly match row names in the metadata table [9].

2. DESeqDataSet Creation

- Create a DESeqDataSet object using the

DESeqDataSetFromMatrix()function, specifying the count data, metadata, and design formula [9] [37]. - Define the design formula to include all major sources of biological variation, with the factor of interest specified last [2]. For example:

design = ~ batch + condition. - Perform pre-filtering to remove genes with very low counts (e.g.,

rowSums(counts(dds)) > 5) to reduce memory usage and improve computational efficiency [6] [9].

3. Differential Expression Analysis

- Execute the core analysis with a single call to

DESeq():dds <- DESeq(dds)[2] [38]. - This function automatically performs estimation of size factors, dispersion estimation, fitting of generalized linear models, and Wald statistics [2].

- For large datasets, enable parallel processing using the BiocParallel package to reduce computation time [6].

4. Results Extraction and Interpretation

- Extract results using

results()function, specifying the contrast of interest for multi-factor designs [38] [6]. - Apply independent filtering to automatically remove low-count genes, improving multiple testing correction [33].

- Sort results by adjusted p-value and filter based on both statistical significance (e.g., padj < 0.05) and biological relevance (e.g., |log2FoldChange| > 1) [38] [37].

Successful implementation of DESeq2 analysis requires both biological and computational resources. The following table details key components of the research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for DESeq2 Analysis

| Category | Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Materials | RNA samples | High-quality (RIN > 8) | Source of transcriptomic data |

| Library preparation kit | Poly-A selection or rRNA depletion | cDNA library construction | |

| Sequencing platform | Illumina recommended | Generation of raw sequence data | |

| Computational Resources | R environment | Version 4.0 or higher | Statistical computing platform |

| Bioconductor | Version 3.18 or higher | Genomic analysis repository | |

| DESeq2 package | Version 1.44.0 or higher | Differential expression analysis | |

| Supporting packages | tidyverse, pheatmap, ggplot2 | Data manipulation and visualization | |

| Computational Hardware | Memory | 8-64 GB depending on sample size | Handling large count matrices |

| CPU cores | 1-16 cores for parallel processing | Speeding up computation | |

| Storage | SSD recommended | Fast data access and processing |

Advanced Considerations in Experimental Design

Design Formula Specification

The design formula represents a critical component of DESeq2 analysis, specifying how samples should be grouped and compared. Proper specification of the design formula ensures that the statistical model accurately captures the experimental structure and appropriately controls for sources of variation beyond the condition of interest [2]. For basic two-group comparisons (e.g., treated vs. control), the design formula is straightforward: ~ condition. However, more complex experimental designs require additional considerations:

For studies with multiple factors (e.g., batch effects, sex, age), the design formula should include these as additive terms: ~ batch + sex + condition [2]. When investigating interaction effects between variables (e.g., whether the treatment effect differs by sex), an interaction term can be included: ~ age + treatment + sex:treatment [2]. Alternatively, a combined factor approach can be used by creating a new variable that represents the interaction and including it in the design: ~ age + treat_sex [2].

The order of factors in the design formula matters for the default comparisons made by DESeq2, though specific contrasts can always be explicitly specified in the results() function [2] [6]. The factor of interest for differential expression should typically be placed last in the formula when using default settings [2].

Dispersion Shrinkage: Technical Implementation

The dispersion shrinkage methodology in DESeq2 represents a sophisticated empirical Bayes approach that stabilizes parameter estimates by sharing information across genes with similar expression levels [33]. The technical implementation involves:

1. Gene-wise Dispersion Estimates: Initial estimates are obtained using the method of moments, providing a gene-specific measure of variability [35]. These estimates are calculated solely from the data for each individual gene without borrowing information from other genes [33].

2. Curve Fitting: A smooth curve is fit to the gene-wise estimates as a function of the mean normalized counts, capturing the overall trend where dispersion typically decreases with increasing expression strength [33]. This curve represents a prior expectation for the dispersion of a gene with a given expression level.

3. Shrinkage Toward the Prior: The final dispersion values are calculated by shrinking the gene-wise estimates toward the fitted curve, with the strength of shrinkage determined by the precision of the gene-wise estimate and the variance of the dispersion estimates around the curve [33]. The mathematical formulation can be represented as:

αi^final = wi · αi^gene-wise + (1 - wi) · α_i^fitted

where w_i represents a gene-specific weight that depends on the residual variance and the number of replicates [33]. This approach results in more stable estimates, particularly for genes with low counts or few replicates, while preserving the biological reality that some genes may genuinely exhibit higher-than-expected variability [33].

Interpretation of Results and Biological Validation

Key Output Metrics and Their Interpretation

The DESeq2 analysis pipeline generates several important metrics for each gene, which must be properly interpreted to draw meaningful biological conclusions. The primary results table includes:

- baseMean: The average of the normalized counts across all samples, providing a measure of overall expression level [38].

- log2FoldChange: The estimated logarithmic fold change between experimental conditions, representing the effect size [38] [9].

- lfcSE: The standard error of the log2 fold change estimate, indicating the precision of the effect size measurement [38].

- stat: The Wald statistic, calculated as log2FoldChange / lfcSE, used for significance testing [38].

- pvalue: The nominal p-value from the Wald test assessing the null hypothesis that the log2 fold change equals zero [38] [9].

- padj: The p-value adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, controlling the false discovery rate (FDR) [38] [9].

When interpreting results, researchers should consider both statistical significance (padj < 0.05 or another appropriate threshold) and biological significance (magnitude of log2FoldChange) [37]. The independent filtering automatically applied by DESeq2 removes genes with very low counts from multiple testing considerations, as these genes have little power to detect differential expression regardless of effect size [33].

Visualization and Downstream Analysis

Effective visualization of results facilitates biological interpretation and quality assessment. DESeq2 supports several diagnostic plots that aid in result evaluation:

- MA-plots: Display log2 fold changes versus mean expression, helping to visualize the distribution of differential expression across expression levels [38] [6].

- Dispersion plot: Shows the relationship between dispersion estimates and mean normalized counts, allowing assessment of the shrinkage procedure [2].

- PCA plots: Generated from regularized log-transformed or variance-stabilized counts, revealing sample-to-sample distances and potential batch effects [37].

- Heatmaps: Visualize expression patterns of differentially expressed genes across samples, facilitating identification of co-regulated genes or sample clusters [37].

For downstream analysis, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) or pathway analysis tools can identify biological processes, pathways, or functions enriched among differentially expressed genes. The integration of these approaches with careful statistical modeling provided by DESeq2 enables comprehensive biological interpretation of transcriptomic data.

The DESeq2 Workflow in Action: A Step-by-Step Analytical Pipeline

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, the initial count of reads mapped to a gene is not only proportional to the actual RNA expression but is also influenced by multiple technical factors [36]. Normalization is the crucial process of scaling raw count values to account for these "uninteresting" factors, making gene expression levels more comparable between and within samples [36]. Library depth, or sequencing depth, is a primary factor that must be corrected for during between-sample comparisons. Without this correction, a sample with a higher total number of reads might falsely appear to have higher expression for all genes compared to a sample with fewer reads [36] [39].

The DESeq2 package implements a robust normalization method known as the median of ratios method, which simultaneously accounts for sequencing depth and RNA composition [36] [33] [40]. This method is a critical first step in the differential expression workflow, ensuring that the statistical model, which operates on raw counts, is provided with data where technical biases have been minimized [40].

The Principles Behind DESeq2's Median of Ratios Method

Comparison with Other Normalization Methods

Several normalization methods exist for RNA-seq data, each with different strengths, weaknesses, and appropriate use cases. The table below summarizes common methods.

Table 1: Common RNA-Seq Count Normalization Methods

| Normalization Method | Description | Accounted Factors | Recommendations for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPM (Counts Per Million) | Counts scaled by the total number of reads | Sequencing depth | Gene count comparisons between replicates of the same sample group; NOT for within-sample comparisons or DE analysis. |

| TPM (Transcripts per Kilobase Million) | Counts per length of transcript (kb) per million reads mapped | Sequencing depth and gene length | Gene count comparisons within a sample or between samples of the same group; NOT for DE analysis. |

| RPKM/FPKM | Similar to TPM | Sequencing depth and gene length | Gene count comparisons between genes within a sample; NOT for between-sample comparisons or DE analysis. |

| DESeq2's Median of Ratios [36] | Counts divided by sample-specific size factors determined by the median ratio of gene counts relative to geometric mean per gene | Sequencing depth and RNA composition | Gene count comparisons between samples and for DE analysis; NOT for within-sample comparisons. |

| EdgeR's TMM [36] | Uses a weighted trimmed mean of the log expression ratios between samples | Sequencing depth, RNA composition, and gene length | Gene count comparisons between and within samples and for DE analysis. |

DESeq2's method is particularly suited for differential expression analysis because it is robust to the presence of a large number of differentially expressed (DE) genes or a few extreme outlier genes, which can skew other methods like those based on total count [36] [39]. A key reason for avoiding methods like RPKM/FPKM for between-sample comparisons is that the total normalized counts can differ between samples, preventing a direct comparison of expression levels for the same gene across samples [36].

Theoretical Foundation and Assumptions

The median of ratios method relies on a fundamental assumption: the majority of genes in an experiment are not differentially expressed [36] [33]. This allows for the distribution of expression ratios between a sample and a pseudo-reference to be centered around a value that represents the technical bias factor, rather than biological differences.

This method specifically corrects for:

- Sequencing depth: The total number of reads obtained per sample.

- RNA composition: A situation where a few highly expressed genes in one sample consume a large share of the sequencing counts, making all other genes appear less expressed in that sample relative to others, even if their true biological expression is unchanged [36] [39].

The mathematical goal is to find, for each sample ( j ), a size factor ( s_j ) such that:

[ \hat{K}{ij} = \frac{K{ij}}{s_j} ]

where ( K{ij} ) is the raw count for gene ( i ) in sample ( j ), and ( \hat{K}{ij} ) is the normalized count. These size factors ( s_j ) are then incorporated directly into DESeq2's generalized linear model [33].

Step-by-Step Protocol for Size Factor Estimation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for estimating size factors in DESeq2.

Diagram 1: Workflow for DESeq2 Size Factor Estimation

Detailed Computational Steps

The workflow can be broken down into the following detailed steps:

Create a pseudo-reference sample: For each gene ( i ), a pseudo-reference count is computed as the geometric mean across all samples ( j ) in the experiment. [ \text{pseudo-reference}i = \sqrt[n]{\prod{j=1}^n K_{ij}} ] In practice, this is calculated as the exponentiated mean of the natural logarithms of the counts [36].

Calculate the ratio of each sample to the reference: For every gene in every sample, the ratio of its count to the pseudo-reference count is calculated. [ \text{ratio}{ij} = \frac{K{ij}}{\text{pseudo-reference}_i} ] This step generates a table of ratios for all genes across all samples [36].

Calculate the normalization factor (size factor) for each sample: The size factor for sample ( j ) is the median of all gene ratios for that sample, excluding genes where the count is zero in any sample. [ sj = \text{median}({\text{ratio}{ij} \; | \; i=1,\dots,M}) ] The use of the median is what provides robustness against genes that are extremely differentially expressed, as they will not disproportionately influence the central tendency [36].

Calculate normalized count values: The final normalized counts for each gene in each sample are obtained by dividing the raw counts by the estimated size factor for that sample. [ \hat{K}{ij} = \frac{K{ij}}{s_j} ]

Table 2: Example Calculation of Size Factors

| Gene | Sample A | Sample B | Pseudo-Reference | Ratio A | Ratio B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF2A | 1489 | 906 | ( \sqrt{1489 \times 906} \approx 1161.5 ) | ( 1489/1161.5 \approx 1.28 ) | ( 906/1161.5 \approx 0.78 ) |

| ABCD1 | 22 | 13 | ( \sqrt{22 \times 13} \approx 16.9 ) | ( 22/16.9 \approx 1.30 ) | ( 13/16.9 \approx 0.77 ) |

| MEFV | 793 | 410 | ( \sqrt{793 \times 410} \approx 570.2 ) | ( 793/570.2 \approx 1.39 ) | ( 410/570.2 \approx 0.72 ) |

| BAG1 | 76 | 42 | ( \sqrt{76 \times 42} \approx 56.5 ) | ( 76/56.5 \approx 1.35 ) | ( 42/56.5 \approx 0.74 ) |

| MOV10 | 521 | 1196 | ( \sqrt{521 \times 1196} \approx 883.7 ) | ( 521/883.7 \approx 0.59 ) | ( 1196/883.7 \approx 1.35 ) |

| Size Factor (( s_j )) | median(1.28, 1.30, 1.39, 1.35, 0.59) = 1.30 | median(0.78, 0.77, 0.72, 0.74, 1.35) = 0.77 |

Practical Implementation in R

The following code demonstrates how to perform size factor estimation and count normalization using DESeq2 in R. It assumes you have a count matrix countData and a sample information dataframe colData with matching row and column names.

In this code, the estimateSizeFactors() function performs all the steps outlined in the protocol above. The DESeqDataSet object (dds) stores both the raw counts and the calculated size factors, which are then used internally by the counts(dds, normalized=TRUE) function to output the normalized counts [41] [40].

Validation and Troubleshooting

Assessing Size Factor Quality

After estimation, it is good practice to examine the size factors.

- Size factors typically center around 1. Large deviations from 1 (e.g., 0.1 or 10) indicate substantial differences in sequencing depth between samples [36].

- A strong linear relationship between size factors and total library size (column sums of raw counts) is generally expected. A scatter plot of size factors against total counts can reveal any anomalies [41].

Common Issues and Solutions

- Extreme Size Factors: If a sample has a very large or small size factor, inspect the raw counts for that sample. It may have an unusual number of zeros or an extremely high count for a single gene, potentially indicating a technical issue.

- Assumption Violations: The median-of-ratios method may perform poorly in experiments with widespread, asymmetric differential expression (e.g., global transcriptional shutdown). In such cases, using spike-in controls or alternative normalization methods as implemented in other packages may be necessary [39].

- Data Integrity: Ensure that the count matrix does not contain normalized values (e.g., RPKM, FPKM) as input, as this will violate the statistical assumptions of DESeq2's model [40].

Integration with Downstream Analysis

The estimated size factors are seamlessly integrated into subsequent stages of the DESeq2 workflow.

- Dispersion Estimation: The normalized counts are used to estimate the dispersion of each gene, which quantifies the within-group variability [33].

- Statistical Testing: During the testing for differential expression, the size factors are incorporated as offsets in the negative binomial generalized linear model. This ensures that comparisons of counts between samples are adjusted for differences in library depth [33] [40].

- Exploratory Data Analysis: For visualization methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), it is recommended to use transformations of the normalized data that stabilize variance across the mean, such as the variance stabilizing transformation (VST) or the regularized logarithm (rlog) available in DESeq2, rather than the normalized counts directly [41] [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DESeq2 Normalization

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Count Matrix | Integer matrix of unambiguously mapped reads per gene per sample. Essential input for DESeq2. | Can be generated from BAM files using summarizeOverlaps [23] or from abundance estimators via tximport [40]. |

| DESeq2 R Package | Primary software package implementing the median of ratios normalization and differential expression analysis. | Available via Bioconductor. Replaces and extends the original DESeq package [33] [40]. |

| Annotation Database | Provides genomic ranges information linking count matrix rows to genes. | e.g., GenomicFeatures package to create a TranscriptDb object from a GTF file [23]. |

| tximport / tximeta | R packages to import and summarize transcript-level abundance estimates (e.g., from Salmon, kallisto) to the gene-level. | Corrects for potential changes in gene length across samples; recommended over direct read counting [40]. |

| Variance Stabilizing Transformation (VST) | A transformation applied to normalized counts to stabilize variance across the dynamic range of expression. | Used for downstream visualizations (e.g., PCA, heatmaps) to prevent highly variable genes from dominating the analysis [41] [40]. |

In the analysis of RNA-seq data, accurately estimating the variability of gene expression counts is a critical step for robust identification of differentially expressed genes. The challenge arises from the typical structure of RNA-seq datasets: they measure thousands of genes, yet often include only a small number of biological replicates (e.g., 3-6 per condition) [33]. With so few replicates, traditional methods that treat each gene independently produce highly unreliable variance estimates. DESeq2 addresses this fundamental limitation through a sophisticated two-step process for modeling dispersion, which involves initial gene-wise estimation followed by shrinkage towards a consensus trend [2] [33]. This protocol details the theoretical framework and practical implementation of dispersion estimation and shrinkage within the context of a comprehensive RNA-seq exploratory analysis using DESeq2, providing researchers and drug development professionals with essential methodology for accurate variance estimation.

Theoretical Foundation

The Negative Binomial Model and Dispersion Parameter