A Practical Guide to Hierarchical Clustering for Transcriptomics Data: From Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for performing hierarchical clustering on transcriptomics data.

A Practical Guide to Hierarchical Clustering for Transcriptomics Data: From Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for performing hierarchical clustering on transcriptomics data. Covering foundational concepts through advanced applications, the article explores how this classical method compares with modern algorithms like graph-based and deep learning approaches. It delivers practical guidance on data preprocessing, distance metric selection, and dendrogram interpretation while addressing critical challenges such as clustering consistency and performance optimization. Through validation strategies and comparative analysis with methods like PCA and state-of-the-art tools, this resource equips researchers to effectively implement hierarchical clustering for robust cell type identification and biological discovery across diverse transcriptomics applications.

Understanding Hierarchical Clustering: Core Concepts and Role in Transcriptomics Analysis

Hierarchical clustering is a fundamental unsupervised machine learning technique used to build a hierarchy of nested clusters, providing a powerful approach for exploring transcriptomic data. In biological research, this method is indispensable for identifying patterns in high-dimensional data, such as gene expression profiles from RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) or single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) experiments [1]. The resulting dendrogram offers an intuitive visual representation of relationships between genes or samples, revealing natural groupings that may correspond to functional gene modules, distinct cell types, or disease subtypes [2]. Within the field of transcriptomics, hierarchical clustering has been successfully applied to identify novel molecular subtypes of cancer, build phylogenetic trees, group protein sequences, and discover biomarkers or functional gene groups [3]. The technique is particularly valuable because it doesn't require prior knowledge of the number of clusters, making it ideal for exploratory analysis where the underlying data structure is unknown [3].

Hierarchical clustering methods primarily fall into two categories: agglomerative (bottom-up) and divisive (top-down) approaches [4]. Both methods produce tree-like structures called dendrograms that illustrate the nested organization of clusters at different similarity levels. In transcriptomics, this hierarchy often reflects biological reality, where genes belong to pathways, cells form tissues, and species share evolutionary histories [3]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these two approaches, along with detailed protocols for their application in transcriptomics research.

Fundamental Principles: Agglomerative vs. Divisive Clustering

Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering

Agglomerative clustering follows a "bottom-up" approach where each data point begins as its own cluster, and pairs of clusters are successively merged until only one cluster remains [3]. The algorithm follows these steps: (1) Start by considering each of the N samples as an individual cluster; (2) Compute the proximity matrix containing distances between all clusters; (3) Find the two closest clusters and merge them; (4) Update the proximity matrix to reflect the new cluster arrangement; and (5) Repeat steps 3-4 until only a single cluster remains [4]. This process creates a hierarchy of clusters that can be visualized as a dendrogram, with the final single cluster at the root and individual data points as leaves [2].

Divisive Hierarchical Clustering

Divisive clustering employs a "top-down" approach that begins with all samples in a single cluster, which is recursively split into smaller clusters until each cluster contains only one sample [4]. The process involves: (1) Starting with all samples in one cluster; (2) Dividing the cluster into two subclusters using a selected criterion; (3) Recursively applying the division process to each resulting subcluster; and (4) Continuing until each cluster contains only one sample [4]. While conceptually straightforward, the divisive approach is computationally challenging because the first step alone requires considering all possible divisions of the data, amounting to 2^(n-1)-1 combinations for n samples [4].

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their directionality. Agglomerative methods build the hierarchy by successively merging smaller clusters, while divisive methods create the hierarchy by successively splitting larger clusters. In practice, agglomerative methods are more widely used due to their computational efficiency, though divisive methods are generally considered safer because starting with the entire dataset may reduce the impact of early false decisions [4].

Linkage Methods and Distance Metrics

The definition of "closeness" between clusters is determined by linkage methods, which significantly impact the resulting cluster structure. Different linkage methods are available, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 1: Comparison of Linkage Methods in Hierarchical Clustering

| Linkage Method | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Transcriptomics Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Linkage | Uses the shortest distance between any two points in two clusters [5] | Can detect non-elliptical shapes | Sensitive to noise and outliers; can cause "chaining" [4] | Rarely used for transcriptomics due to noise sensitivity |

| Complete Linkage | Uses the farthest distance between points in two clusters [5] | Creates compact clusters of similar size | Sensitive to outliers [4] | Useful when expecting well-separated, compact cell populations |

| Average Linkage | Uses the average of all pairwise distances between clusters [5] | Balanced approach; less sensitive to outliers | Computationally more intensive than single/complete | Most commonly used method for gene expression data [5] |

| Ward's Linkage | Merges clusters that minimize the increase in total within-cluster variance [3] | Creates tight, spherical clusters | Biased toward producing clusters of similar size | Ideal for scRNA-seq to identify distinct cell types |

Distance metrics quantify the similarity between gene expression profiles. Common metrics include:

- Euclidean distance: The straight-line distance between points in high-dimensional space [3]

- Manhattan distance: Distance along axes, like walking city blocks [3]

- Correlation-based distance: Measures whether genes go up and down together across samples [3]

- Cosine similarity: Measures the angle between expression vectors [3]

In transcriptomics, correlation-based distances often perform well because they capture co-expression patterns regardless of absolute expression levels.

Experimental Protocols for Transcriptomics Data

Protocol 1: Agglomerative Clustering for Bulk RNA-seq Data

This protocol details the application of agglomerative hierarchical clustering to bulk transcriptomics data for identifying sample groups and co-expressed genes.

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Data Collection: Obtain normalized gene expression matrix (samples × genes) from RNA-seq processing pipeline.

- Quality Control: Filter out genes with low expression (e.g., genes with counts <10 in >90% of samples).

- Normalization: Apply appropriate normalization method (e.g., TPM, FPKM, or variance-stabilizing transformation).

- Gene Selection: Select genes with highest variance (e.g., top 5000 most variable genes) to reduce dimensionality.

Clustering Implementation

- Distance Calculation: Compute pairwise distances between samples using selected distance metric (Euclidean or correlation-based recommended).

- Linkage Method: Apply average linkage or Ward's linkage to build cluster hierarchy.

- Dendrogram Construction: Visualize results as a dendrogram using statistical software (R, Python).

- Cluster Identification: Cut dendrogram at appropriate height to obtain desired number of clusters.

Validation and Interpretation

- Cluster Stability: Assess cluster robustness through resampling methods.

- Biological Validation: Perform enrichment analysis on gene clusters using GO, KEGG, or GSEA.

- Visualization: Create heatmaps with dendrograms to display expression patterns.

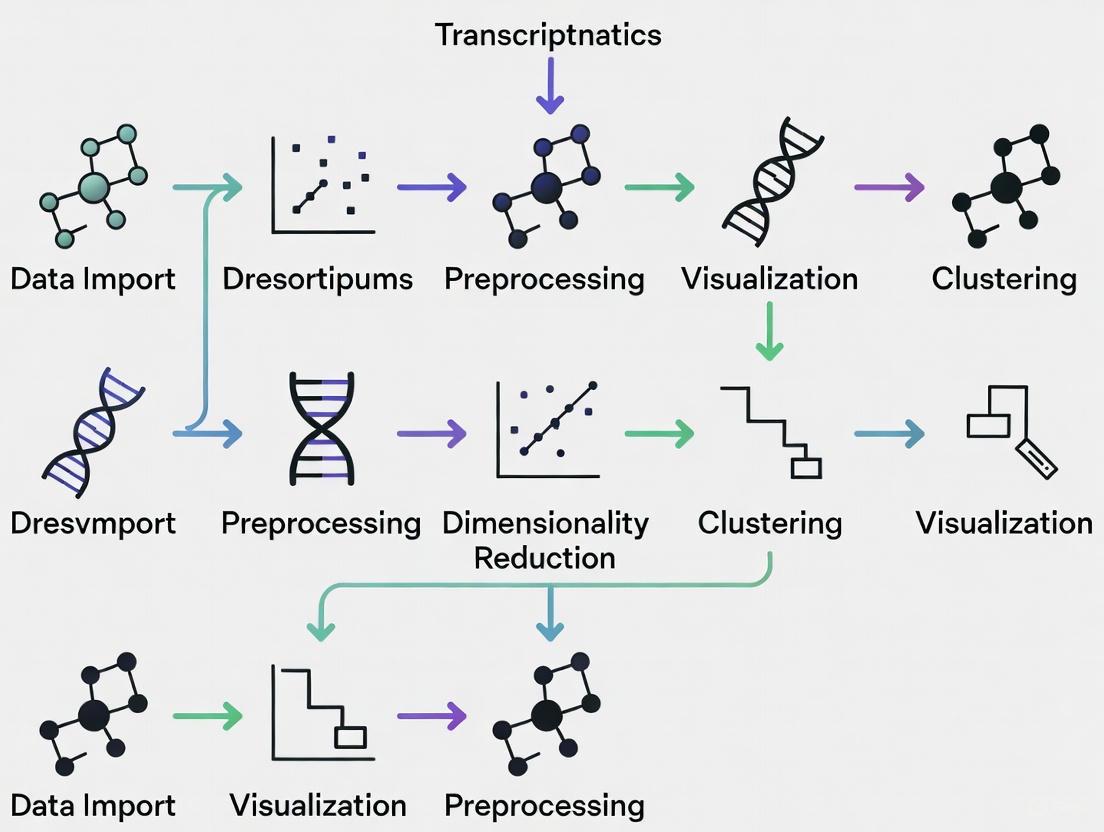

Figure 1: Workflow for Agglomerative Clustering of Bulk RNA-seq Data

Protocol 2: Divisive Clustering for Single-Cell Transcriptomics

This protocol adapts the divisive approach for single-cell RNA sequencing data, which benefits from the method's tendency to make more global decisions early in the clustering process.

Data Preprocessing for Single-Cell Data

- Data Collection: Obtain count matrix from scRNA-seq processing (cells × genes).

- Quality Control: Filter out low-quality cells using metrics like mitochondrial percentage, number of detected genes, and total counts.

- Normalization: Apply scRNA-seq specific normalization (e.g., SCTransform or log-normalization).

- Feature Selection: Identify highly variable genes using mean-variance relationship.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Perform PCA on highly variable genes to reduce technical noise.

Divisive Clustering Implementation

- Initialization: Begin with all cells in a single cluster.

- Division Criterion: Use maximum likelihood clustering (DRAGON algorithm) to identify optimal split [4].

- Recursive Division: Apply division criterion recursively to resulting subclusters.

- Stopping Condition: Continue until clusters cannot be significantly divided or biological relevance is lost.

- Cluster Annotation: Assign cell type identities based on marker gene expression.

Validation in Single-Cell Context

- Differential Expression: Identify marker genes for each cluster.

- Cell Type Annotation: Compare with known cell type markers.

- Trajectory Analysis: Investigate developmental relationships between clusters.

- Integration with Protein Expression: Validate clusters with CITE-seq data when available [6].

Figure 2: Workflow for Divisive Clustering of Single-Cell RNA-seq Data

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated clustering performance across multiple transcriptomic datasets. A comprehensive assessment of 28 clustering algorithms on 10 paired transcriptomic and proteomic datasets revealed significant differences in performance across methods [6].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Clustering Methods on Transcriptomic Data

| Method | Type | ARI Score | NMI Score | Scalability | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scDCC | Deep Learning | High (0.78) | High (0.81) | Medium | Large-scale scRNA-seq data |

| scAIDE | Deep Learning | High (0.80) | High (0.83) | Medium | Integrating multiple omics data |

| FlowSOM | Agglomerative | High (0.76) | High (0.79) | High | Proteomic and transcriptomic data [6] |

| Louvain | Agglomerative | Medium (0.68) | Medium (0.72) | High | Large single-cell datasets [7] |

| DRAGON | Divisive | Medium-High | Medium-High | Low-Medium | Small to medium datasets with clear separation [4] |

Performance metrics include Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), where values closer to 1 indicate better clustering performance [6]. The benchmarking revealed that top-performing methods like scAIDE, scDCC, and FlowSOM demonstrate strong performance across different omics modalities [6].

For agglomerative methods, studies comparing conventional algorithms on biological data have shown that graph-based techniques often outperform conventional approaches when validated against known gene classifications [8]. The Jaccard similarity coefficient has been used to measure cluster agreement with functional annotation sets like GO and KEGG, providing biological validation of clustering results [8].

Divisive methods like DRAGON have demonstrated superior accuracy in specific contexts, correctly clustering data with distinct topologies and achieving the highest clustering accuracy with multi-dimensional leukemia data [4]. However, these methods remain computationally challenging for very large datasets.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Tools for Hierarchical Clustering in Transcriptomics Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat | R Package | Single-cell analysis toolkit | Cell clustering, visualization, and differential expression [7] |

| SCTransform | Normalization Method | Variance-stabilizing transformation | Normalization of scRNA-seq data [9] |

| PCA | Dimensionality Reduction | Linear projection to lower dimensions | Noise reduction before clustering [7] |

| MAST | Statistical Test | Differential expression analysis | Identifying cluster-specific biomarkers [7] |

| DAVID | Bioinformatics Database | Functional enrichment analysis | Interpreting biological meaning of clusters [7] |

| Cytoscape | Network Visualization | Biological network analysis | Visualizing gene co-expression networks [7] |

Implementation in Research Workflows

Successful application of hierarchical clustering in transcriptomics requires integration of these tools into coherent workflows. For agglomerative clustering, a typical pipeline involves: (1) data preprocessing with Seurat, (2) normalization with SCTransform, (3) highly variable gene selection, (4) dimensionality reduction with PCA, (5) distance calculation, (6) hierarchical clustering with appropriate linkage method, and (7) biological interpretation with functional enrichment tools [7].

For divisive approaches, the DRAGON algorithm provides a maximum likelihood framework that can be implemented in MATLAB, offering an alternative to conventional hierarchical methods [4]. This approach is particularly valuable when working with datasets where the global structure is more important than local relationships.

Advanced Applications and Integration with Multi-Omics Data

Hierarchical clustering has evolved beyond single-omics applications to become a cornerstone of integrative genomics. The decreasing cost of high-throughput technologies has motivated studies involving simultaneous investigation of multiple omic data types collected on the same patient samples [5]. Integrative clustering methods enable researchers to discover molecular subtypes that reflect coordinated alterations across genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic levels [5].

Advanced applications include:

- Multi-Omics Subtyping: Simultaneous clustering of transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data to identify disease subtypes with distinct clinical outcomes.

- Temporal Clustering: Analysis of time-series transcriptomic data during differentiation processes, such as stem cell differentiation into cardiomyocytes [1].

- Cross-Species Integration: Combining human and mouse transcriptomic data to identify conserved cell states, as demonstrated in CD8+ T cell exhaustion studies [9].

- Spatial Transcriptomics: Integrating spatial information with hierarchical clustering to identify tissue domains with distinct expression profiles.

The integration of clustering results with protein expression data through CITE-seq or similar technologies provides a powerful validation mechanism, ensuring that transcriptomic clusters correspond to biologically meaningful cell states [6].

Hierarchical clustering remains an essential tool in transcriptomics research, with agglomerative and divisive approaches offering complementary strengths. Agglomerative methods provide computationally efficient clustering suitable for most applications, while divisive methods offer potentially more accurate global structure identification at higher computational cost. The choice between these approaches depends on research goals, dataset size, and biological context. As transcriptomics technologies continue to evolve, hierarchical clustering methods adapt to new challenges, particularly in single-cell and multi-omics integration. By following standardized protocols and leveraging appropriate tools, researchers can extract biologically meaningful insights from complex transcriptomic datasets, advancing our understanding of health and disease.

The Critical Role of Clustering in scRNA-seq Analysis for Cell Type Identification

Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biomedical research by enabling the profiling of gene expression at the level of individual cells, uncovering cellular heterogeneity in complex tissues that is masked in bulk RNA-seq analyses [10] [11]. Cell clustering represents a fundamental computational step in scRNA-seq analysis, serving as the primary method for distinguishing distinct cell populations and identifying cell types based on transcriptional similarities [12] [6]. The underlying assumption is that cells sharing similar gene expression profiles likely correspond to the same cell type or state [12]. This process is crucial for constructing comprehensive cell atlases, understanding disease pathogenesis, identifying rare cell populations, and developing targeted therapeutic strategies [10] [6]. In clinical applications, clustering has enabled the discovery of clinically significant cellular subpopulations, such as cancer cells with poor prognosis features in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and metastatic breast cancer cells with strong epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition signatures [10].

Computational Foundations of scRNA-seq Clustering

The ScRNA-seq Data Analysis Workflow

Clustering does not occur in isolation but represents a critical step in an integrated analytical pipeline. The standard workflow begins with raw data processing and quality control to remove damaged cells, dying cells, and doublets (multiple cells mistakenly identified as one) [10]. Following quality control, data normalization addresses technical variations between cells, enabling meaningful biological comparisons [13]. Feature selection then identifies highly variable genes that drive cell-to-cell heterogeneity, reducing noise and computational complexity [10] [13]. Dimensionality reduction techniques, particularly principal component analysis, transform the high-dimensional gene expression data into a lower-dimensional space that preserves essential biological signals [14]. Finally, clustering algorithms group cells based on their proximity in this reduced space, revealing distinct cell populations [6].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and sequential dependencies between these key analytical steps:

Algorithmic Approaches to Clustering

Clustering algorithms for scRNA-seq data can be broadly categorized into three computational paradigms, each with distinct mechanisms and advantages:

Classical Machine Learning Methods: These include algorithms like SC3, CIDR, and TSCAN that often employ k-means, hierarchical clustering, or model-based approaches. They typically operate on dimension-reduced data and are valued for their interpretability [6].

Community Detection Methods: Algorithms such as Leiden and Louvain leverage graph theory by constructing cell-to-cell similarity graphs and identifying densely connected communities within these graphs. These methods are particularly efficient for large-scale datasets [6].

Deep Learning Methods: Modern approaches including scDCC, scAIDE, and scDeepCluster use neural networks to learn non-linear representations that are optimized for clustering performance. These methods can capture complex biological relationships but require greater computational resources [6].

Benchmarking Clustering Performance

Comparative Algorithm Performance

A comprehensive 2025 benchmarking study evaluated 28 clustering algorithms across 10 paired transcriptomic and proteomic datasets using multiple performance metrics, including Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), clustering accuracy, purity, memory usage, and running time [6]. The table below summarizes the top-performing methods based on this systematic evaluation:

Table 1: Top-performing single-cell clustering algorithms across transcriptomic and proteomic data

| Algorithm | Class | Overall Ranking (Transcriptomics) | Overall Ranking (Proteomics) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scAIDE | Deep Learning | 2nd | 1st | Top performance across modalities |

| scDCC | Deep Learning | 1st | 2nd | Excellent performance, memory efficient |

| FlowSOM | Classical ML | 3rd | 3rd | Robustness, fast processing |

| PARC | Community Detection | 5th | N/R | Strong in transcriptomics |

| CarDEC | Deep Learning | 4th | N/R | Strong in transcriptomics |

Practical Considerations for Method Selection

Algorithm selection should be guided by specific experimental needs and constraints. For researchers prioritizing clustering accuracy across both transcriptomic and proteomic data, scAIDE, scDCC, and FlowSOM consistently deliver top-tier performance [6]. When computational efficiency is paramount, TSCAN, SHARP, and MarkovHC offer excellent time efficiency, while scDCC and scDeepCluster provide memory-efficient operation [6]. Community detection methods like Leiden and Louvain present a balanced option when seeking a compromise between performance and computational demands [6]. The choice of clustering resolution should align with biological questions - broader resolution may suffice for identifying major cell types, while finer resolution enables discovery of subtle cell states [6].

Experimental Protocol for scRNA-seq Clustering

Standardized Clustering Workflow

The following protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for clustering scRNA-seq data using the Seurat framework, a widely adopted analysis toolkit:

Data Normalization: Normalize raw count data using the

SCTransform()function, regressing out confounding variables such as mitochondrial content percentage and total read counts [14].Feature Selection: Identify highly variable genes that exhibit strong cell-to-cell variation, typically using the

FindVariableFeatures()function in Seurat.Dimensionality Reduction: Perform principal component analysis (PCA) using the

RunPCA()function. Determine the number of informative principal components to retain for downstream analysis by examining the elbow plot generated withElbowPlot()[14].Batch Effect Correction: For multi-sample datasets, integrate batches using the Harmony package with the

RunHarmony()function to remove technical batch effects while preserving biological variation [14].Cell Clustering: Construct a shared nearest neighbor graph using

FindNeighbors()followed by community detection clustering withFindClusters()across a range of resolution parameters [14].Quality Assessment: Identify and remove low-quality clusters characterized by high mitochondrial content using

VlnPlot()to visualize QC metrics across clusters. Repeat clustering iteratively until no such clusters remain [14].Visualization: Generate two-dimensional embeddings using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) with the

RunUMAP()function for exploratory data visualization [14].Cluster Annotation: Perform differential expression analysis between clusters using

FindMarkers()orFindConservedMarkers()to identify marker genes for cell type identification [14].

The following workflow diagram maps this procedural sequence from data input to biological interpretation:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools and their functions in scRNA-seq clustering analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Seurat | Comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis | Primary framework for clustering and visualization |

| Harmony | Batch effect correction | Multi-sample dataset integration |

| SCTransform | Normalization and variance stabilization | Data preprocessing |

| scAIDE | Deep learning clustering | High-performance cell type identification |

| scDCC | Deep learning clustering | Memory-efficient analysis of large datasets |

| FlowSOM | Classical machine learning clustering | Robust clustering across modalities |

| 10X Genomics Cell Ranger | Raw data processing | UMI count matrix generation from fastq files |

Advanced Applications and Integrative Approaches

Multi-Omics Integration for Enhanced Cell Identity Mapping

Clustering approaches are increasingly being extended to multimodal single-cell data, integrating transcriptomics with simultaneous measurements of surface protein expression (CITE-seq), chromatin accessibility (scATAC-seq), and other molecular features [6] [15]. Such integration provides a more comprehensive definition of cellular identity beyond transcriptomics alone. For clustering multi-omics data, specialized integration methods such as moETM, sciPENN, and totalVI create shared representations that combine information across modalities [6]. The emerging framework HALO advances this further by modeling causal relationships between chromatin accessibility and gene expression, decomposing these relationships into coupled (dependent changes) and decoupled (independent changes) components to better understand regulatory dynamics [15].

Clinical and Translational Applications

In Alzheimer's disease research, clustering of snRNA-seq data has revealed cell-type-specific molecular changes in neurodegenerative brains, identifying vulnerable neuronal populations and activated glial subpopulations contributing to disease pathology [16]. In oncology, clustering analyses have uncovered intratumoral heterogeneity, therapy-resistant cell subpopulations, and the cellular ecosystem of the tumor microenvironment [10] [11]. For drug discovery, clustering enables the identification of novel cell states that may represent therapeutic targets and facilitates drug screening using patient-derived organoid models [10] [11].

Clustering remains the cornerstone computational method for extracting biological meaning from scRNA-seq data, transforming high-dimensional gene expression measurements into interpretable cellular taxonomies. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve toward multi-omic assays and increased throughput, clustering methodologies must similarly advance to leverage these rich data sources. The integration of causal modeling approaches like HALO [15] with robust clustering frameworks represents the cutting edge of cell identity mapping. For biomedical researchers, careful selection of clustering algorithms based on benchmarking studies [6] and implementation of standardized workflows [14] will ensure biologically meaningful results that accelerate both basic research and translational applications across diverse fields from neurobiology to oncology.

How Hierarchical Clustering Complements Other Exploratory Methods like PCA

In transcriptomics research, exploratory data analysis is a critical first step for extracting meaningful biological insights from high-dimensional datasets. Among the most widely used unsupervised methods, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering each offer distinct advantages and, when used together, provide a more comprehensive understanding of cellular heterogeneity and gene expression patterns [17]. PCA serves as a powerful dimensionality reduction technique, creating a low-dimensional representation of samples that optimally preserves the variance within the original dataset [17]. In contrast, hierarchical clustering builds a tree-like structure that successively groups similar objects based on their expression profiles, serving both visualization and partitioning functions [17] [2]. This application note examines the complementary relationship between these methods within the context of transcriptomics data analysis, providing detailed protocols for their implementation and integration.

Theoretical Foundation and Comparative Analysis

Core Principles of PCA and Hierarchical Clustering

PCA reduces data dimensionality by identifying orthogonal principal components (PCs) that capture maximum variance, with the first component (PC1) representing the largest variance source, followed by PC2, and so on [18]. The resulting low-dimensional projection filters out weak signals and noise, potentially revealing cleaner patterns than raw data visualizations [17]. PCA also provides synchronized sample and variable representations, allowing researchers to identify variables characteristic of specific sample groups [17].

Hierarchical clustering creates a hierarchical nested clustering tree through iterative pairing of the most similar objects [2]. The algorithm employs a bottom-up (agglomerative) approach, calculating similarity between all sample pairs using measures like Euclidean distance, then successively merging the closest pairs into clusters until all objects unite in a single tree [17] [2]. The resulting dendrogram provides intuitive visualization of relationships between samples or genes, with heatmaps enabling simultaneous examination of expression patterns across the entire dataset [17].

Comparative Strengths and Limitations

Table 1: Comparative analysis of PCA and hierarchical clustering characteristics

| Characteristic | PCA | Hierarchical Clustering |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Dimensionality reduction and variance capture | Grouping and tree-structure visualization |

| Data Processing | Filters out low-variance components | Uses all data without filtering |

| Output | Low-dimensional sample projection | Dendrogram with associated heatmap |

| Group Definition | Reveals natural groupings through variance separation | Always creates clusters, even with weak signal |

| Noise Handling | Discards low-variance components (often noise) | Displays all data, including potential noise |

| Interpretation | Sample positions indicate similarity | Branch lengths indicate similarity degrees |

The most significant distinction lies in their fundamental approaches: PCA prioritizes variance representation while hierarchical clustering focuses on similarity-based grouping [17]. This difference makes them naturally complementary rather than competitive. In practice, when strong biological signals exist (e.g., distinct cell subtypes), both methods typically reveal concordant patterns, as demonstrated in studies of acute lymphoblastic leukemia where both approaches clearly separated different patient subtypes [17].

Integrated Analytical Protocol for Transcriptomics Data

Preprocessing and Quality Control

Sample Preparation and RNA Sequencing

- Isolate high-quality RNA (RIN > 7.0) from samples using appropriate kits (e.g., PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit) [18]

- Prepare cDNA libraries using poly(A) selection and library preparation kits (e.g., NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit) [18]

- Sequence libraries on appropriate platforms (e.g., Illumina NextSeq 500) to obtain sufficient read depth (e.g., 8 million aligned reads per library) [18]

Data Processing and Normalization

- Demultiplex raw sequencing data (e.g., using bcl2fastq) [18]

- Align reads to reference genome (e.g., mm10 for mouse) using aligners like TopHat2 [18]

- Generate raw count matrices using tools like HTSeq [18]

- Apply appropriate normalization methods (e.g., Scran or SCNorm) to address technical variability [19]

Batch Effect Mitigation

- Control for technical variations by processing experimental and control conditions simultaneously [18]

- Minimize operator variability through standardized protocols

- Harvest samples at consistent times to control for circadian effects

- Sequence all comparison groups in the same run to minimize technical batch effects [18]

Protocol for Complementary Analysis

PCA Implementation and Interpretation

- Input Preparation: Use normalized count matrices, optionally filtering low-count genes

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply PCA to obtain principal components using standard implementations (R:

prcomp, Python:sklearn.decomposition.PCA) [19] - Variance Assessment: Examine scree plot to determine the number of meaningful components

- Visualization: Plot samples in 2D or 3D space using the first 2-3 principal components

- Pattern Identification: Identify sample groupings and outliers in the reduced space

- Variable Examination: Analyze component loadings to identify genes driving separation

Hierarchical Clustering Implementation

- Distance Calculation: Compute pairwise distances between samples using Euclidean distance

- Linkage Method Selection: Choose appropriate linkage method (e.g., Ward's method)

- Tree Construction: Build dendrogram through iterative clustering (R:

hclust, Python:scikit-learnhierarchical clustering) [19] - Heatmap Integration: Visualize data matrix with samples ordered by dendrogram structure

- Cluster Identification: Cut dendrogram at appropriate height to define sample groups

Integrated Interpretation

- Concordance Check: Compare PCA groupings with hierarchical clustering results

- Pattern Validation: Use consistent coloring in both visualizations to identify corresponding patterns

- Marker Identification: Combine PCA loadings with heatmap patterns to identify group-specific genes

- Biological Validation: Correlate computational groupings with known biological variables

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Integrated analytical workflow for transcriptomics data exploration

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key reagents and computational tools for transcriptomics analysis

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation | PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit | High-quality RNA extraction from limited samples [18] |

| Library Prep | NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Kit | mRNA enrichment for transcriptome sequencing [18] |

| cDNA Synthesis | NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit | Library preparation for Illumina sequencing [18] |

| Alignment | TopHat2 | Read alignment to reference genomes [18] |

| Quantification | HTSeq | Generation of raw count matrices from aligned reads [18] |

| Normalization | Scran | Pool-based size factors for single-cell normalization [19] |

| Differential Expression | edgeR | Negative binomial models for DEG identification [18] |

| Clustering Algorithms | Hierarchical clustering, K-means, Leiden | Sample and gene grouping approaches [19] |

Advanced Applications and Method Integration

Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics Extensions

The PCA and hierarchical clustering framework extends to advanced transcriptomics applications. In single-cell RNA sequencing, these methods help identify cell subpopulations and validate clustering results [6]. For spatial transcriptomics, specialized tools like BayesSpace, SpaGCN, and STAGATE incorporate spatial coordinates alongside expression values to define spatially coherent domains while maintaining the fundamental principles of expression-based clustering [20].

Multi-Omics Data Integration

Recent benchmarking studies demonstrate that clustering methods like scDCC, scAIDE, and FlowSOM perform robustly across both transcriptomic and proteomic data [6]. When analyzing integrated multi-omics data, PCA and hierarchical clustering remain valuable for initial exploration and quality assessment before applying more specialized integration algorithms.

Figure 2: Complementary strengths of PCA and hierarchical clustering

PCA and hierarchical clustering offer complementary approaches for exploratory transcriptomics analysis. PCA excels at capturing major variance components and filtering noise, while hierarchical clustering provides intuitive similarity-based groupings with detailed expression pattern visualization. Used together within a structured analytical protocol, these methods enable robust identification of biologically meaningful patterns in transcriptomics data, forming an essential foundation for subsequent hypothesis-driven research and biomarker discovery in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling the comprehensive analysis of gene expression profiles at the individual cell level, providing unprecedented insights into cellular heterogeneity in complex biological systems [11]. This technology has fundamentally transformed our ability to investigate how different cells behave at single-cell resolution, uncovering new insights into biological processes that were previously masked in bulk RNA-seq experiments [11]. The key contrast between bulk RNA-seq and scRNA-seq lies in whether each library reflects an individual cell or a cell group, driven by unique challenges including scarce transcripts in single cells, inefficient mRNA capture, losses in reverse transcription, and bias in cDNA amplification due to the minute amounts involved [11].

The applications of scRNA-seq span multiple domains including drug discovery, tumor microenvironment characterization, biomarker discovery, and microbial profiling [11]. Through scRNA-seq, researchers have gained the potential to uncover previously unknown cell types, map developmental pathways, and investigate the complexity of tumor diversity [11]. This technology is particularly valuable when addressing crucial biological inquiries related to cell heterogeneity and early embryo development, especially in cases involving a limited number of cells [11]. The ability to resolve cellular heterogeneity through clustering analysis forms the foundation for many of these applications, making hierarchical clustering approaches essential for extracting meaningful biological insights from high-dimensional scRNA-seq data.

Analytical Framework and Workflow

Core Computational Workflow

A robust analytical workflow is essential for transforming raw scRNA-seq data into biologically meaningful insights. The standard workflow encompasses multiple critical stages, beginning with quality control to identify and remove low-quality cells and data that might represent multiple cells [11]. Subsequent steps include data normalization, feature selection, dimensionality reduction, and clustering analysis—with the latter being particularly crucial for identifying distinct cell populations [11]. The clustering results then enable downstream analyses such as differential expression, which can compare average expression between cell types or conditions [21].

Specialized computational tools tailored to scRNA-seq data are essential due to the unique characteristics of this data type, which is often noisy, high-dimensional, and sparsely populated [11]. The selection of appropriate analytical methods is further complicated by the explosion of single-cell analysis tools, making it challenging for researchers to choose the right tool for their specific dataset [11]. This challenge extends to clustering algorithms, where methodological selection significantly impacts the reliability and interpretation of results.

Table 1: Key Stages in scRNA-seq Data Analysis

| Analysis Stage | Purpose | Common Tools/Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | Filter low-quality cells and multiplets | FastQC, Trimmomatic |

| Normalization | Account for technical variability | SCTransform, LogNormalize |

| Feature Selection | Identify biologically relevant genes | HVG selection |

| Dimensionality Reduction | Visualize and compress data | PCA, UMAP, t-SNE |

| Clustering | Identify distinct cell populations | Leiden, Louvain, scDCC |

| Differential Expression | Find marker genes between groups | MAST, DESeq2, edgeR |

Workflow Visualization

Application 1: Resolving Cellular Heterogeneity

Experimental Protocol for Cell Type Identification

Objective: To identify distinct cell populations within a complex tissue sample using scRNA-seq clustering analysis.

Sample Preparation and Single-Cell Isolation:

- Extract viable single cells from the tissue of interest using appropriate dissociation protocols [11].

- For tissues where dissociation is challenging, consider single-nuclei RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) as an alternative [11].

- Isolate individual cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or droplet-based microfluidics depending on throughput requirements [11].

- Perform cell lysis to release RNA molecules and capture polyadenylated mRNA using poly[T]-primers while minimizing ribosomal RNA capture [11].

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Select appropriate scRNA-seq protocol based on research goals (e.g., full-length transcript protocols like Smart-Seq2 for isoform analysis, or 3'-end counting protocols like Drop-Seq for high-throughput applications) [11].

- Incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification bias and enable accurate transcript quantification [11].

- Prepare sequencing libraries following protocol-specific guidelines, with particular attention to amplification method (PCR-based or in vitro transcription) [11].

- Sequence libraries using an Illumina platform with sufficient depth to capture the transcriptional diversity of individual cells.

Computational Analysis:

- Perform quality control using tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic to remove low-quality reads and adapter sequences [22].

- Align reads to the reference genome using dedicated scRNA-seq alignment tools for efficient resource utilization [11].

- Generate a gene expression matrix with cells as columns and genes as rows, incorporating UMI counts [11].

- Apply normalization methods to correct for technical variability between cells [22].

- Identify highly variable genes to focus on biologically relevant features [6].

- Perform dimensionality reduction using PCA followed by visualization with UMAP or t-SNE [6].

- Execute clustering analysis using graph-based methods (Leiden, Louvain) or other advanced algorithms [6] [23].

Benchmarking Clustering Performance

The selection of appropriate clustering algorithms is critical for accurate cell type identification. Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated 28 computational algorithms on 10 paired transcriptomic and proteomic datasets, assessing performance across various metrics including clustering accuracy, peak memory usage, and running time [6]. These studies reveal that different algorithms demonstrate varying strengths depending on the data modality and analytical requirements.

Table 2: Performance of Top scRNA-seq Clustering Algorithms

| Algorithm | Type | ARI Score | NMI Score | Computational Efficiency | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scDCC | Deep learning | High | High | Moderate | Top performance across omics |

| scAIDE | Deep learning | High | High | Moderate | Proteomic data |

| FlowSOM | Machine learning | High | High | High | Large datasets, robustness |

| PARC | Community detection | Moderate | Moderate | High | Transcriptomic data |

| Leiden | Graph-based | Moderate | Moderate | High | Standard scRNA-seq analysis |

| Louvain | Graph-based | Moderate | Moderate | High | General purpose clustering |

The table above summarizes the performance characteristics of leading clustering algorithms, with scDCC, scAIDE, and FlowSOM demonstrating the strongest performance across both transcriptomic and proteomic data [6]. These algorithms excel in key metrics including Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI), which quantify clustering quality by comparing predicted and ground truth labels [6].

Enhancing Clustering Reliability

A significant challenge in clustering analysis is the inconsistency that arises from stochastic processes in clustering algorithms [23]. The single-cell Inconsistency Clustering Estimator (scICE) was developed to address this limitation by evaluating clustering consistency and providing consistent clustering results [23]. This approach achieves up to a 30-fold improvement in speed compared to conventional consensus clustering-based methods such as multiK and chooseR, making it practical for large datasets exceeding 10,000 cells [23].

The scICE framework employs the inconsistency coefficient (IC) to evaluate label consistency without requiring hyperparameters or computationally expensive consensus matrices [23]. When applied to real and simulated scRNA-seq datasets, scICE revealed that only approximately 30% of clustering numbers between 1 and 20 were consistent, enabling researchers to focus on a narrower set of reliable candidate clusters [23]. This approach significantly enhances the efficiency and robustness of cellular heterogeneity analysis.

Application 2: Uncovering Developmental Trajectories

Experimental Protocol for Trajectory Inference

Objective: To reconstruct cellular differentiation pathways and developmental processes from scRNA-seq data.

Experimental Design:

- Collect samples across multiple time points during the developmental process of interest.

- Ensure sufficient cell coverage at each time point to capture rare transitional states.

- Process samples individually with appropriate sample multiplexing to minimize batch effects.

- Include biological replicates to ensure statistical robustness of inferred trajectories.

Computational Analysis for Trajectory Inference:

- Perform standard scRNA-seq processing and clustering as described in Section 3.1.

- Identify potential branching points and transitional cell states through careful examination of clustering results in low-dimensional embeddings.

- Apply trajectory inference algorithms (e.g., Monocle3, Slingshot) to reconstruct developmental paths.

- Order cells along pseudotime trajectories to model progression through developmental stages.

- Identify genes with dynamic expression patterns along the trajectories.

- Validate key transitional states using marker gene expression and functional enrichment analysis.

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Beyond standard trajectory inference, several advanced approaches enhance the resolution of developmental analyses:

Differential Detection Analysis: While traditional differential expression tools compare average expression between cell types, differential detection workflows infer differences in the average fraction of cells in which expression is detected [21]. This approach provides complementary information to standard differential expression analysis, both in terms of individual genes reported and their functional interpretation [21]. Through simulations and case studies, joint analyses of differential expression and differential detection have demonstrated enhanced capability to uncover biologically relevant patterns in developmental processes [21].

Spatial Transcriptomics Integration: Spatial transcriptomics technologies significantly advance trajectory analysis by quantifying gene expression within tissue sections while preserving crucial spatial context information [24]. By integrating multiple tissue slices, researchers can achieve a comprehensive 3D reconstruction of developing tissues, preserving spatial relationships that cannot be captured in isolated 2D slices [24]. This holistic perspective is critical for studying complex tissue architectures and developmental processes, offering insights into cellular organization, interactions, and spatial gradients of gene expression [24].

Trajectory Analysis Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for scRNA-seq Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Protocols | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly[T] Primers | Capture polyadenylated mRNA | All scRNA-seq protocols | Minimizes ribosomal RNA capture |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Correct for amplification bias | Drop-Seq, inDrop, 10X Genomics | Enables accurate transcript counting |

| Hydrogel Beads | Encapsulate individual cells | inDrop | Low cost per cell |

| Microfluidic Chips | Single-cell isolation | Drop-Seq, 10X Genomics | High-throughput processing |

| Cell Lysis Buffers | Release RNA content | All protocols | Maintains RNA integrity |

| Reverse Transcription Mix | cDNA synthesis | Smart-Seq2, CEL-Seq2 | Protocol-specific optimization |

| PCR Amplification Mix | cDNA amplification | Most protocols | Can introduce bias if not optimized |

| In Vitro Transcription Mix | RNA amplification | CEL-Seq2, inDrop | Linear amplification reduces bias |

The selection of computational tools is as critical as wet laboratory reagents for successful scRNA-seq applications. Recent benchmarking studies provide guidance for tool selection across various analytical scenarios [6] [23]. For clustering analysis, methods such as scDCC, scAIDE, and FlowSOM demonstrate strong performance across different data modalities, while tools like scICE enhance reliability by evaluating clustering consistency [6] [23].

For differential expression analysis, a comprehensive benchmarking of 288 pipelines revealed that careful selection of analytical tools based on the specific biological context provides more accurate biological insights compared to default software configurations [22]. This highlights the importance of tailored analytical strategies rather than indiscriminate tool selection for achieving high-quality results [22].

Single-cell RNA sequencing has fundamentally transformed our ability to investigate cellular heterogeneity and developmental trajectories at unprecedented resolution. The applications outlined in this document—from resolving complex cell populations to reconstructing developmental pathways—demonstrate the power of this technology to uncover novel biological insights. However, realizing this potential requires careful experimental design, appropriate protocol selection, and robust computational analysis.

The integration of advanced computational methods, including reliable clustering algorithms and trajectory inference approaches, enables researchers to extract meaningful biological knowledge from high-dimensional scRNA-seq data. Furthermore, emerging technologies such as spatial transcriptomics and multi-omics integration promise to further enhance our understanding of biological systems in their native context. As the field continues to evolve, the standardized protocols and benchmarking data presented here provide a foundation for rigorous and reproducible single-cell research, ultimately advancing our knowledge of cellular behavior in health and disease.

Core Concepts and Workflow

Hierarchical clustering is an unsupervised machine learning method used to build a hierarchy of clusters, revealing underlying structures within complex datasets like those in transcriptomics research [25] [26]. Its application allows researchers to explore gene expression patterns without a priori assumptions, grouping genes or samples based on similarity [1].

There are two primary algorithmic strategies, as outlined in Table 1 [25] [26]:

Table 1: Hierarchical Clustering Algorithm Types

| Algorithm Type | Approach | Description | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agglomerative | Bottom-Up | Begins with each data point as its own cluster and iteratively merges the most similar pairs until one cluster remains. [25] | Common default method; suitable for identifying smaller, tighter clusters. [25] [26] |

| Divisive | Top-Down | Starts with all data points in a single cluster and recursively splits them into smaller clusters. [25] | Identifying large, distinct clusters first; can be more accurate but computationally expensive. [25] [26] |

The results are universally presented in a dendrogram, a tree-like diagram that visualizes the sequence of cluster merges (or splits) and the similarity (distance) at which each merge occurred [25] [26]. The height at which two clusters are joined represents the distance between them, allowing researchers to understand the nested cluster relationships intuitively.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for performing hierarchical clustering on transcriptomics data, from raw data to biological interpretation.

Distance Metrics

The choice of distance metric fundamentally defines the concept of "similarity" between two data points, such as genes or samples. For transcriptomics data, where the pattern of expression across conditions is often more critical than absolute expression levels, correlation-based distances are widely used [27].

Table 2: Common Distance Metrics for Transcriptomics Data

| Distance Metric | Formula | Application in Transcriptomics |

|---|---|---|

| Euclidean | ( d(x, y) = \sqrt{\sum{i=1}^n (xi - y_i)^2} ) | Measures geometric ("as-the-crow-flies") distance. Sensitive to absolute expression levels. [27] |

| Correlation | ( d(x, y) = 1 - r ) (Pearson/Spearman) | Ideal for clustering genes based on co-expression patterns, as it is invariant to shifts in baseline expression. [27] |

| Absolute Correlation | ( d(x, y) = 1 - |r| ) | Clusters genes with strong positive OR negative correlations (e.g., regulatory relationships). [27] |

| Manhattan | ( d(x, y) = \sum{i=1}^n |xi - y_i| ) | Less sensitive to outliers than Euclidean distance. [27] |

A critical step in transcriptomics analysis is data pre-processing. Centering (subtracting the mean) and scaling (dividing by the standard deviation to create z-scores) transform the data. Using Euclidean distance on z-scores is equivalent to using correlation distance on the original data, which focuses the analysis purely on expression patterns [27].

Linkage Methods

The linkage criterion determines how the distance between clusters (as opposed to individual points) is calculated, profoundly influencing the shape and compactness of the resulting clusters [25] [27].

Table 3: Comparison of Common Linkage Methods

| Linkage Method | Formula | Cluster Shape Tendency | Pros and Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single | ( D(A,B) = \min{d(a,b) | a \in A, b \in B} ) | String-like, elongated | Pro: Can handle non-elliptical shapes. Con: Sensitive to noise and outliers; "chaining effect." [26] [27] |

| Complete | ( D(A,B) = \max{d(a,b) | a \in A, b \in B} ) | Ball-like, compact | Pro: Less sensitive to noise; produces tight, spherical clusters. Con: Can be biased by large clusters. [25] [26] [27] |

| Average (UPGMA) | ( D(A,B) = \frac{1}{|A|\cdot|B|}\sum{a \in A}\sum{b \in B} d(a,b) ) | Ball-like, compact | A balanced compromise between Single and Complete linkage. [25] [27] |

| Ward | ( D(A,B) = \frac{|A|\cdot|B|}{|A \cup B|} || \muA - \muB ||^2 ) | Ball-like, compact | Pro: Minimizes within-cluster variance; creates clusters of similar size. Less affected by outliers. [26] |

For gene expression data, a combination of correlation distance and complete linkage clustering is frequently employed and often provides biologically meaningful results [27].

Protocol for Hierarchical Clustering of Transcriptomics Data

Pre-processing and Distance Calculation

- Data Normalization: Normalize raw read counts (e.g., from RNA-seq) to account for library size and other technical variations. Common methods include TPM (Transcripts Per Million), FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Million), or using tools like DESeq2 or edgeR.

- Transformation: Apply a logarithmic transformation, typically ( \log2(\text{expression} + \text{pseudocount}) ), to stabilize variance and make the data more symmetric. A pseudocount (e.g., 0.25, 1) is added to handle zero values [27].

- Filtering: Filter out genes with very low expression or minimal variance across samples to reduce noise.

- Distance Matrix Computation: Calculate the pairwise distance matrix between all items (genes or samples). For clustering genes by expression pattern, correlation distance is highly recommended [1] [27].

Agglomerative Clustering Execution

- Input: Begin with a dissimilarity matrix and 'n' clusters, each containing a single data point [25] [26].

- Linkage Criterion: Select a linkage method (see Table 3). Complete linkage is a robust default for transcriptomics [27].

- Iterative Merging: Identify the two clusters with the smallest distance according to the linkage criterion. Merge these two clusters into a new, larger cluster [25] [26].

- Matrix Update: Update the distance matrix to reflect the distances between the new cluster and all remaining clusters using the Lance-Williams recursive formula [26].

- Repetition: Repeat steps 3 and 4 until all data points are contained within a single root cluster [25] [26].

Interpreting the Dendrogram and Defining Clusters

The final dendrogram provides a complete history of the merging process. To obtain specific clusters for downstream analysis, the dendrogram must be "cut."

Figure 2: Interpreting a dendrogram. Cutting at different heights (H1, H2) yields different numbers of clusters, allowing researchers to choose the most biologically relevant granularity.

- Determine the Cut Height: The number of clusters is determined by the number of vertical lines intersected by a horizontal "cut" line across the dendrogram. The height of this line corresponds to the dissimilarity at which clusters are defined [26].

- Selecting the Number of Clusters (k):

- Domain Knowledge: Use biological context to guide a sensible number of clusters (e.g., expected cell types or pathways).

- The Elbow Method: Plot the within-cluster sum of squares against the number of clusters. The "elbow" point, where the sum of squares stops decreasing sharply, can indicate a good value for k [26].

- Dendrogram Inspection: Look for the highest levels of the tree where branches are long, indicating a clear separation between clusters. The optimal number of clusters is often where the vertical lines in the dendrogram have the most considerable space to move up and down without crossing another horizontal merge line [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomics Clustering

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | Generates the sequencing libraries from RNA samples. Essential for producing the raw count data used in clustering. |

| Normalization Software (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR) | Performs statistical normalization on raw count data to remove technical biases, a critical pre-processing step before clustering. |

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Provides the computational environment and libraries (e.g., R stats, hclust, factoextra) to perform distance calculation, clustering, and visualization. |

| Visualization Package (e.g., ggplot2, pheatmap) | Enables the creation of publication-quality dendrograms and heatmaps to visualize clustering results and communicate findings. |

Step-by-Step Implementation: From Data Preparation to Dendrogram Interpretation

In transcriptomics research, hierarchical clustering is a fundamental technique for exploring gene expression patterns and identifying novel biological relationships. The reliability of its output is profoundly dependent on the quality of the input data, making optimal data preprocessing not merely a preliminary step but the foundation of robust analysis. This document details applied protocols for two critical preprocessing steps—data normalization and highly variable gene (HVG) selection—specifically framed within the context of preparing data for hierarchical clustering. Proper normalization removes technical noise, enabling valid comparisons across samples, while effective HVG selection reduces dimensionality to highlight biologically meaningful signals. Together, these steps ensure that hierarchical clustering reveals true underlying biological structure rather than technical artifacts or random noise [28] [29].

Normalization Strategies

Normalization adjusts raw gene expression data to eliminate systematic technical variations, such as those arising from differences in sequencing depth, library preparation, or platform-specific effects. This is a prerequisite for any downstream comparative analysis, including hierarchical clustering, as it ensures that the distances between data points reflect biological differences rather than technical bias [28].

Normalization Methods for Transcriptomic Data

Various normalization methods are employed in transcriptomic data analysis. The choice of method depends on the data type (e.g., microarray vs. RNA-seq) and the specific goals of the analysis, such as cross-platform compatibility.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Normalization Methods

| Method Name | Underlying Principle | Best For | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOG_QN [28] | Applies a log transformation followed by quantile normalization. | Cross-platform classification (e.g., Microarray & RNA-seq). | Effective for machine learning model transfer across platforms. | Performance may vary with dataset characteristics. |

| LOG_QNZ [28] | LOG_QN with an added z-score standardization. | Cross-platform classification where feature scaling is critical. | Improves model performance by standardizing feature scales. | Adds complexity to the data pipeline. |

| NDEG-Based Normalization [28] | Uses non-differentially expressed genes (NDEGs) as a stable reference set. | Scenarios requiring a robust, biologically-informed reference set. | Leverages biologically stable genes; improves cross-platform performance. | Relies on accurate identification of NDEGs. |

| Standard Z-Score | Standardizes data to a mean of zero and standard deviation of one. | General-purpose normalization for many downstream analyses. | Simple, intuitive, and widely applicable. | Can be sensitive to outliers. |

| Quantile Normalization | Forces the distribution of expression values to be identical across samples. | Making sample distributions comparable. | Creates uniform distributions across samples. | Assumes most genes are not differentially expressed. |

Protocol: NDEG-Based Normalization for Cross-Platform Robustness

This protocol outlines a robust normalization strategy using NDEGs, which is particularly useful when building models on one transcriptomics platform (e.g., RNA-seq) and applying them to another (e.g., microarray) [28].

Experimental Reagents and Equipment

- Raw Gene Expression Matrix: A count matrix (for RNA-seq) or intensity matrix (for microarray) where rows represent genes and columns represent samples.

- Computational Environment: Python (version 3.11.9 or later) with scientific computing libraries (NumPy, Pandas, Scikit-learn).

- Sample Annotation File: A file containing the molecular subtype or experimental group for each sample.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Data Cleaning: Load the raw gene expression matrix and sample annotation file. Filter the dataset to retain only samples with available class labels (e.g., molecular subtypes). Subsequently, remove any genes that contain missing values to create a complete matrix of shared genes across all samples [28].

- Non-Differentially Expressed Gene (NDEG) Selection:

a. Perform ANOVA: For each gene in the cleaned matrix, perform a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) using the sample class labels as groups. The goal is to test the null hypothesis that the gene's expression does not differ between classes.

b. Calculate F-value: Compute the F-statistic for each gene using the formula:

F = MSB / MSW = [Σn_i(Ȳ_i - Ȳ)^2 / (k-1)] / [ΣΣ(Y_ij - Ȳ_i)^2 / (N-k)]where MSB is the mean square between groups, MSW is the mean square within groups,kis the number of groups,Nis the total sample size,n_iis the sample size per group,Ȳ_iis the group mean, andȲis the overall mean [28]. c. Select NDEGs: Genes with a high p-value (e.g.,p > 0.85) from the ANOVA test fail to reject the null hypothesis, indicating their expression is stable across classes. These genes are selected as the NDEG set for normalization [28]. - Apply Normalization: a. Subset Data: Create a new matrix containing only the expression values of the selected NDEGs. b. Perform LOGQN Normalization: i. Log Transformation: Apply a log2 transformation to the NDEG expression matrix to reduce the effect of extreme values. ii. Quantile Normalization: Normalize the log-transformed data across samples so that the distribution of expression values is identical for each sample [28]. c. (Optional) Perform LOGQNZ Normalization: For an additional standardization step, apply a z-score transformation to the LOG_QN normalized data, standardizing each gene to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 [28].

Selection of Highly Variable Genes

Following normalization, selecting HVGs is a critical dimensionality reduction step. This process filters out genes that exhibit little variation across cells or samples, which likely represent uninteresting technical noise or biological "housekeeping" functions. By focusing on the most variable genes, the analysis highlights features that are most likely to be biologically informative, such as those driving cellular heterogeneity. This leads to a cleaner and more interpretable distance matrix for hierarchical clustering, ultimately revealing more distinct and biologically relevant clusters [29] [30].

HVG Selection Methods

Multiple computational methods have been developed to identify HVGs, each with different underlying assumptions and strengths.

Table 2: Comparison of Highly Variable Gene (HVG) Selection Methods

| Method Name | Underlying Principle | Key Feature | Advantages | Disadvantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLP [29] | Optimized LOESS regression on the relationship between a gene's positive ratio (f) and its mean expression (λ). | Uses Bayesian Information Criterion for automatic bandwidth selection to avoid overfitting. | Robust to sparsity and dropout noise; enhances downstream clustering. | A newer method, less integrated into standard pipelines. |

| VST [29] [30] | Fits a smooth curve to the mean-variance relationship and standardizes expression based on this model. | Part of the widely used Seurat package. | Established, widely-used method. | Can be influenced by high sparsity. |

| SCTransform [29] [30] | Uses Pearson residuals from a regularized negative binomial generalized linear model. | Models single-cell data specifically, accounting for over-dispersion. | Integrated into Seurat workflow; models count data well. | Computationally more intensive than VST. |

| M3Drop [29] | Fits a Michaelis-Menten function to model the relationship between mean expression and dropout rate. | Leverages dropout information, common in single-cell data. | Useful for capturing genes with bimodal expression. | Relies on characteristics of dropout noise. |

Protocol: HVG Selection using the GLP Algorithm

The GLP (LOESS with Positive Ratio) algorithm is a robust feature selection method that precisely captures the non-linear relationship between a gene's average expression level and its positive ratio, making it particularly effective for sparse data like single-cell RNA-seq [29].

Experimental Reagents and Equipment

- Normalized Expression Matrix: A pre-processed and normalized gene expression matrix (from Section 2).

- Computational Environment: R or Python with necessary statistical libraries and the GLP implementation.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Calculate Metrics:

a. Mean Expression (λ): For each gene

j, calculate its mean expression level across all samples (or cells)cusing the formula:λ_j = (1/c) * Σ X_ijwhereX_ijis the expression of genejin samplei[29]. b. Positive Ratio (f): For each genej, calculate the proportion of samples (or cells) in which it is detected. Formally:f_j = (1/c) * Σ min(1, X_ij)[29]. - Filter Low-Prevalence Genes: Remove any genes that are detected in fewer than a minimum number of samples (e.g., 3 cells in scRNA-seq data) to avoid unreliable metrics [29].

- Determine Optimal Smoothing Parameter:

a. The LOESS regression requires a smoothing parameter

⍺. The GLP algorithm automatically determines the optimal⍺by testing a range of values (e.g., from 0.01 to 0.1) [29]. b. For each candidate⍺, perform a LOESS regression ofλ(dependent variable) onf(independent variable). Calculate the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for each model:BIC = c * ln(RSS/c) + k * ln(c), whereRSSis the residual sum of squares,cis the number of observations (genes), andkis the model degrees of freedom [29]. c. Select the⍺value that yields the lowest BIC, indicating the best fit without overfitting. - Perform Two-Step LOESS Regression:

a. First Fit: Using the optimal

⍺, fit a LOESS model to the(f, λ)data for all genes. Apply Tukey's biweight robust method to identify genes that are outliers from the fitted curve [29]. b. Second Fit: Assign zero weight to the outlier genes identified in the first step and re-fit the LOESS model. This minimizes the influence of true biological outliers, leading to a more accurate baseline [29]. - Select Highly Variable Genes: Genes whose actual mean expression level (

λ) is significantly greater than the value predicted (λ_pred) by the final LOESS model are considered highly variable. Select the top N genes with the largest positive residuals (λ - λ_pred) for downstream hierarchical clustering [29].

Integrated Workflow for Hierarchical Clustering

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of data preprocessing and its direct connection to hierarchical clustering, integrating the protocols described in this document.

Preprocessing Workflow for Clustering

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details the essential software and computational tools required to implement the protocols described in this document.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Preprocessing | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Python (v3.11+) | Programming Language | Provides the core environment for implementing custom normalization and HVG selection scripts, such as the NDEG-based and GLP protocols. | Flexible, code-based analysis pipelines [28]. |

| R | Programming Language | Ecosystem for statistical computing; hosts implementations of many popular HVG methods (e.g., in Seurat, SCTransform) and normalization techniques. | Statistical analysis and visualization [31] [30]. |

| Seurat | R/Python Package | A comprehensive toolkit for single-cell analysis, offering integrated functions for normalization (e.g., LogNormalize) and HVG selection (e.g., VST, SCTransform) [29] [30]. | Standardized single-cell RNA-seq analysis. |

| Scanpy | Python Package | A scalable toolkit for single-cell data analysis, analogous to Seurat, providing similar normalization and HVG selection capabilities within the Python ecosystem. | Standardized single-cell RNA-seq analysis. |

| TCGA BRCA Dataset | Reference Data | A publicly available dataset containing matched microarray and RNA-seq data, used for benchmarking and validating cross-platform normalization methods [28]. | Method validation and benchmarking. |

In transcriptomics research, distance metrics are mathematical functions that quantify the dissimilarity between gene expression profiles. The choice of metric fundamentally shapes the outcome of hierarchical clustering and all subsequent biological interpretations. Transcriptomic data, particularly from single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), presents unique challenges including high dimensionality, significant technical noise, and inherent data sparsity due to dropout events. These characteristics mean that no single metric is universally superior; the optimal choice is highly dependent on the biological structure of the dataset under study [32].

The performance of a proximity metric is substantially influenced by whether the data has a discrete structure (with well-separated, terminally differentiated cell types) or a continuous structure (featuring multifaceted gradients of gene expression, as in differentiation or development). A metric that excels for identifying discrete cell types may perform poorly when applied to a continuous developmental trajectory [32]. Furthermore, dataset properties such as cell-population rarity, sparsity, and dimensionality significantly impact metric performance, necessitating a tailored approach to analysis [32].

Comparison of Distance Metrics

Quantitative Comparison of Metric Categories

Table 1: Characteristics and Performance of Major Metric Categories in Transcriptomics

| Metric Category | Specific Examples | Key Characteristics | Recommended Data Context | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-based | Pearson, Spearman, Kendall, Weighted-Rank [32] [33] | Measures linear (Pearson) or monotonic (Spearman, Kendall) relationships. Focuses on expression profile shape rather than magnitude. | Continuous data structures, identifying co-expressed gene modules. | Pearson and Spearman are frequently recommended but performance is dataset-dependent [32]. |

| True Distance | Euclidean, Manhattan, Canberra, Chebyshev [32] [33] | Satisfies mathematical properties of distance (symmetry, triangle inequality). Sensitive to magnitude and background noise. | Discrete data structures with well-separated cell populations. | Euclidean and Manhattan often perform poorly compared to more specialized metrics [32]. |

| Proportionality-based | (\rhop), (\phis) [33] | Designed for compositional data. Measures relative, rather than absolute, differences in abundance. | ScRNA-seq data where relative expression is more informative than absolute counts. | Proposed as strong alternatives to correlation for co-expression analysis [32]. |

| Binary/Dissimilarity | Jaccard Index, Hamming, Yule, Kulsinski [32] | Operates on binarized data (e.g., expression > 0). Captures presence/absence patterns, potentially mitigating dropout effects. | Very sparse datasets, focusing on the pattern of genes detected versus not detected. | Performance varies; Jaccard is used in ensemble methods like ENGEP [33]. |

Practical Performance Insights from Benchmarking

Benchmarking studies reveal that correlation-based metrics (Pearson, Spearman) and proportionality-based measures ((\rhop), (\phis)) often demonstrate strong performance in scRNA-seq clustering tasks [32]. The Canberra distance is also noted for its effectiveness [32]. In contrast, ubiquitous default metrics like Euclidean and Manhattan distances frequently underperform compared to these more specialized alternatives, suggesting that common software defaults should be re-evaluated for transcriptomic applications [32].

Furthermore, advanced tools for predicting gene expression in spatial transcriptomics, such as ENGEP, leverage an ensemble of ten different similarity measures. This set includes Pearson, Spearman, Cosine similarity, Manhattan, Canberra, Euclidean, (\rhop), (\phis), Weighted Rank correlation, and the Jaccard index, acknowledging that no single metric can capture all relevant biological relationships [33].

Experimental Protocols for Metric Evaluation and Application

Protocol: A Framework for Evaluating Distance Metric Performance

Objective: To systematically evaluate and select an optimal distance metric for hierarchical clustering of a given transcriptomics dataset.

I. Data Pre-processing and Normalization

1. Quality Control: Filter out low-quality cells and genes. Standard thresholds include removing cells with fewer than 200 detected genes and genes detected in fewer than 10% of cells [32].

2. Normalization: Normalize gene expression measurements to account for varying cellular sequencing depths. A common approach is to use regularized negative binomial regression (e.g., sctransform) to remove technical noise without dampening biological heterogeneity [34]. Alternatively, normalize by total expression, scale by a factor of 10,000, and apply a log-transform (log1p) [32].

3. Feature Selection: Identify highly variable genes to reduce dimensionality and computational load for subsequent steps.

II. Define Data Structure and Analysis Goal 1. Hypothesize Data Structure: Determine if the biological system is expected to be Discrete (distinct cell types) or Continuous (a differentiation trajectory, developmental process) [32]. 2. Identify Key Challenges: Note the presence of rare cell populations (<5% abundance), high sparsity, or other dataset-specific properties [32].

III. Benchmarking and Metric Selection 1. Select Candidate Metrics: Choose a panel of metrics from different categories based on the initial hypothesis (e.g., Spearman, Canberra, and (\rho_p) for continuous data). 2. Perform Clustering: Apply hierarchical clustering to the dataset using each candidate metric. 3. Evaluate Performance: Assess clustering results using ground truth annotations if available (e.g., Adjusted Rand Index, Silhouette Score). If ground truth is unavailable, evaluate the stability and biological coherence of the resulting clusters. 4. Iterate: If performance is unsatisfactory, return to Step 1 and adjust the pre-processing pipeline or test a different set of metrics.

Protocol: Applying a Chosen Metric for Hierarchical Clustering

Objective: To perform robust hierarchical clustering on a normalized transcriptomics matrix using a selected distance metric.

I. Input Preparation 1. Data Format: Begin with a normalized, log-transformed gene expression matrix (cells x genes). 2. Metric Selection: Use the results from Protocol 3.1 to select the most appropriate distance metric.

II. Distance Matrix Computation