A Practical Protocol for Assessing Predicted Protein Model Quality: From Foundations to Clinical Applications

Accurate assessment of predicted protein model quality is a critical bottleneck in structural bioinformatics, directly impacting the utility of models for function annotation and drug discovery.

A Practical Protocol for Assessing Predicted Protein Model Quality: From Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

Accurate assessment of predicted protein model quality is a critical bottleneck in structural bioinformatics, directly impacting the utility of models for function annotation and drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step protocol for researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate protein structure predictions. We cover foundational concepts, categorize modern quality assessment (QA) methods, and provide practical guidance for method selection and troubleshooting. The protocol synthesizes insights from Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments and recent advances in machine learning, including single-model and consensus approaches. We also address validation strategies and future directions, empowering scientists to confidently integrate computational models into their research pipelines.

Understanding Protein Model Quality Assessment: Why Accuracy Matters in Structural Biology

The fundamental challenge in structural biology, known as the sequence-structure gap, represents the disconnect between the vast and rapidly expanding repository of protein sequence data and the relatively small number of experimentally determined protein structures. While sequencing technologies have advanced to the point where we now have hundreds of millions of protein sequences in databases such as UniProt, only a tiny fraction of these—approximately 1%—have been functionally annotated through experimental characterization [1]. This disparity continues to widen exponentially with advances in sequencing technologies, creating a critical bottleneck in our ability to understand protein function from sequence information alone.

The biological significance of this gap cannot be overstated, as protein structure determines function—a principle central to molecular biology. Proteins must fold into specific three-dimensional configurations to perform their biological roles, whether as enzymes catalyzing biochemical reactions, antibodies recognizing pathogens, or structural components maintaining cellular integrity [2] [3]. Understanding these structures is therefore essential for fundamental biological research and has profound implications for drug discovery, where precise knowledge of target protein structures enables rational drug design [4] [5].

Computational modeling has emerged as the only viable approach to bridge this ever-widening gap. The development of artificial intelligence-based structure prediction tools, particularly AlphaFold2 and its subsequent versions, has revolutionized the field by providing accurate structural models for nearly all cataloged proteins [3] [6]. However, these advances have simultaneously highlighted the critical need for robust methods to assess the quality and reliability of computational models before they can be confidently applied in biological research and therapeutic development.

Computational Modeling Approaches to Bridge the Gap

Several computational strategies have been developed to address the sequence-structure gap, each with distinct methodologies, strengths, and limitations. These approaches leverage different principles and information to predict three-dimensional structures from amino acid sequences.

Table 1: Computational Protein Structure Prediction Methods

| Method | Fundamental Principle | Data Requirements | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative/Homology Modeling [2] | Evolutionary conservation: proteins with similar sequences share similar structures | Known protein structures (templates) with sequence similarity to target | High accuracy when template available (>50% sequence identity); Fast computation | Highly dependent on template availability; Accuracy decreases sharply below 30% sequence identity |

| Threading/Fold Recognition [2] | Structural compatibility: sequences can adopt similar folds even with low sequence similarity | Library of known protein folds/structures | Can detect distant evolutionary relationships; Useful when sequence similarity low | Computationally intensive; Limited by fold library coverage |

| De Novo/Ab Initio Modeling [2] | Physical principles: protein native state corresponds to global free energy minimum | Amino acid sequence only; Physical energy functions or structural fragments | No template required; Can potentially predict novel folds | Extremely computationally demanding; Challenging for large proteins |

| Deep Learning Methods (AlphaFold) [7] [8] | Integration of evolutionary, physical, and geometric constraints through neural networks | Multiple sequence alignments; sometimes template structures | State-of-the-art accuracy; End-to-end learning | Significant computational resources required; Limited explainability |

The revolutionary impact of AlphaFold2 deserves particular emphasis. This deep learning system combines novel transformer architecture with training based on evolutionary, physical, and geometric constraints [8]. Its Evoformer module processes multiple sequence alignments and structural templates through attention mechanisms and triangular updates, enabling the model to reason about spatial and evolutionary relationships simultaneously [8]. The subsequent structure module builds the protein backbone using invariant point attention to integrate all information, directly predicting 3D coordinates for all heavy atoms [7] [8]. This approach achieved unprecedented accuracy in the CASP14 assessment, with a median score of 92.4% (scores above 90% are generally considered acceptable for most applications) [8].

More recently, AlphaFold3 has expanded these capabilities to predict structures of protein complexes with other biological molecules, including nucleic acids, small molecules (ligands), and ions [6]. This represents a significant advancement for drug discovery, as it enables researchers to model how potential drug compounds might interact with their protein targets. AlphaFold3's architecture incorporates a diffusion-based approach—similar to that used in AI image generation—which starts from an atomic cloud and iteratively refines it into the most accurate molecular structure [6].

Protein Model Quality Assessment (MQA) Protocols

The critical step following structure prediction is evaluating model reliability. Protein Model Quality Assessment (MQA) methods have become indispensable tools for determining whether a computational model is sufficiently accurate for downstream applications. These methods can be broadly categorized into three classes: consensus methods, single-model methods, and quasi-single-model methods [9].

MQA Methodologies and Workflows

Consensus methods (also known as multi-model methods) operate on the principle that structural features recurring across multiple independently generated models for the same target are likely to be correct. These methods compare ensembles of models to identify consensus structural elements. Single-model methods evaluate individual structures based on statistical potentials or physical energy functions that capture known properties of native protein structures, such as preferred torsion angles, residue packing densities, and atomic contact patterns. Quasi-single-model methods represent a hybrid approach that incorporates evolutionary information or predicted structural features without directly comparing multiple models [9].

Deep learning has dramatically advanced MQA capabilities, as exemplified by DeepUMQA2, which integrates sequence co-evolution information, protein family structural features, and model-dependent features through an enhanced deep neural network [3]. The system employs triangular multiplication updates and axial attention mechanisms to iteratively refine its assessments, finally predicting residue-residue distance deviations and contact maps to compute per-residue accuracy estimates [3].

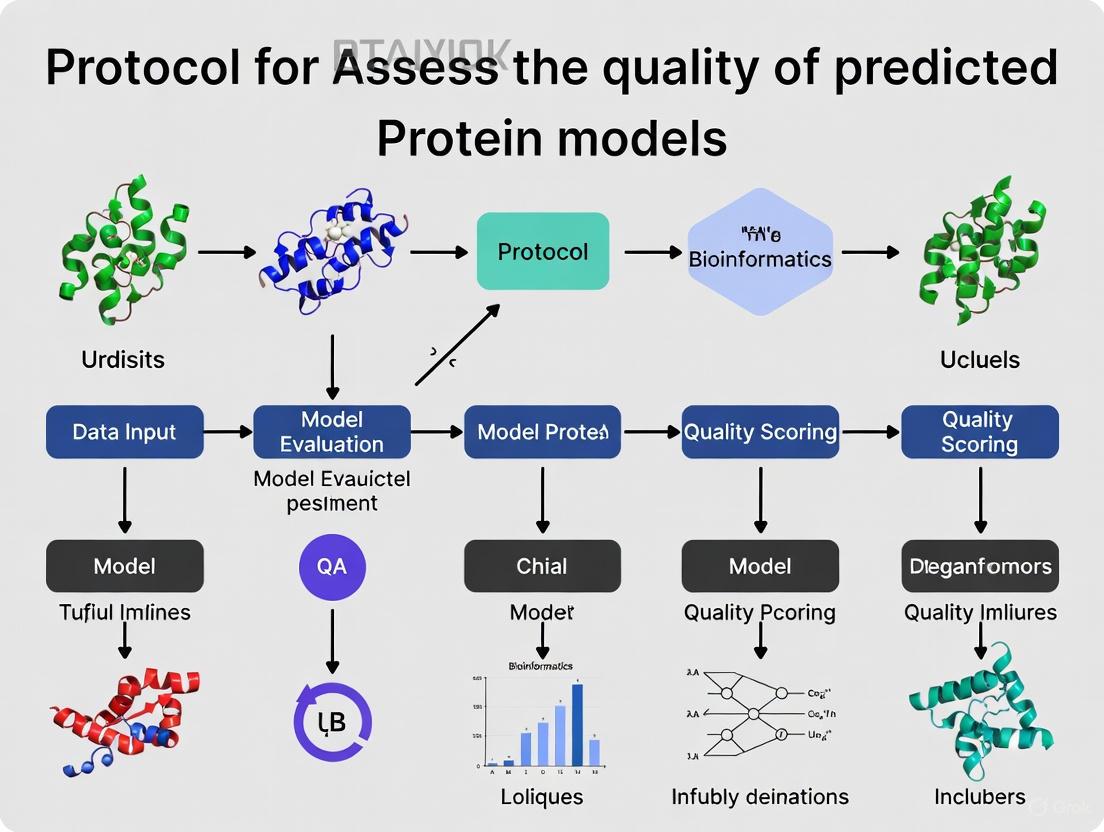

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for quality assessment of protein structural models:

Quantitative Assessment Metrics and Benchmarks

Rigorous assessment of MQA methods requires standardized metrics and benchmarks. The Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments and the Continuous Automated Model Evaluation (CAMEO) platform serve as gold standards for independent evaluation [9]. These benchmarks utilize multiple quantitative metrics to evaluate different aspects of quality assessment performance.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Protein Model Quality Assessment

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Evaluation Focus | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Quality Assessment | Pearson Correlation Coefficient | Linear relationship between predicted and actual global scores | Values >0.9 indicate excellent performance; <0.7 concerning |

| Top 1 Loss | Ability to identify best model from ensemble | Lower values preferable; <0.05 considered excellent | |

| AUC (ROC Analysis) | Discrimination between good and bad models | Values approaching 1.0 ideal; >0.9 considered excellent | |

| AUC₀,₀.₂ (Pruned AUC) | Discrimination at low false-positive rates | Particularly important for practical applications | |

| Local Quality Assessment | Pearson Correlation Coefficient | Per-residue accuracy estimation | Values >0.8 indicate strong local accuracy estimation |

| Average Sequence Entropy (ASE) | Per-residue score calibration | Higher values indicate better performance | |

| pLDDT (AlphaFold) | Predicted Local Distance Difference Test | >90: very high; 70-90: confident; 50-70: low; <50: very low |

The performance of leading MQA methods on standardized datasets demonstrates substantial advances in the field. For instance, DeepUMQA2 achieved Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.919 and 0.899 on CASP13 and CASP14 datasets respectively, outperforming other state-of-the-art methods like ProQ3D and DeepAccNet [3]. Similarly, its top 1 loss values of 0.049 (CASP13) and 0.035 (CASP14) indicate a remarkable ability to identify the most accurate model from an ensemble of predictions [3].

Experimental Protocols for MQA Validation

Model Quality Assessment Using DeepUMQA2

Purpose: To evaluate the accuracy of protein structural models using the DeepUMQA2 framework, which integrates sequence and structural information through enhanced deep neural networks.

Materials:

- Protein structural models in PDB format

- Amino acid sequence of the target protein

- Computational resources (CPU and GPU-enabled system)

- Databases: UniClust30 (for MSA), PDB100 (for template search)

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Prepare the protein structural model and amino acid sequence. Models can be generated by AlphaFold, RoseTTAFold, I-TASSER, or other prediction methods.

- Feature Extraction: a. Run HHblits against UniClust30 to generate Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSA) b. Run HHsearch against PDB100 to identify structural templates c. Extract sequence features from MSA, structural features from templates, and model-dependent features from the input structure

- Feature Integration: Combine all extracted features into initial "pair features" for input to the neural network

- Neural Network Processing: Process features through the DeepUMQA2 network architecture employing: a. Triangular multiplication updates for efficient information propagation b. Axial attention mechanisms to capture long-range interactions

- Output Generation: The network produces: a. Residue-residue distance deviations b. Contact maps (15Å threshold)

- Quality Score Calculation: Compute per-residue accuracy estimates and global quality scores from the network outputs

Validation: Compare predictions against experimental structures using local Distance Difference Test (lDDT) when experimental references are available.

Troubleshooting: If feature extraction fails due to database issues, ensure all required databases are properly downloaded and formatted. The complete databases require approximately 2.62 TB of storage space [8].

Large-Scale Structure Prediction Quality Control

Purpose: To implement quality control for large-scale protein structure prediction pipelines, addressing computational challenges and ensuring consistent assessment across thousands of models.

Materials:

- High-performance computing environment (cloud or cluster)

- Parallel file system (e.g., FSx for Lustre)

- Containerization platform (Docker/Singularity)

- Batch job scheduling system (e.g., AWS Batch)

Procedure:

- Infrastructure Optimization: a. Configure parallel file system with appropriate capacity (≥9.6TB recommended for hundreds of targets) b. Collocate compute instances and file systems in the same availability zone to minimize latency c. Enable file system compression (LZ4) to optimize I/O performance

- Batch Processing: a. Organize input sequences into batches (20-50 concurrent jobs) b. Use g4dn.4xlarge instances for improved CPU performance in MSA stage c. Monitor file system throughput and adjust capacity if I/O bottlenecks occur

- Quality Assessment Integration: a. Run AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold prediction pipelines b. Execute DeepUMQA2 or similar MQA methods on all output models c. Aggregate quality scores across all predictions

- Results Analysis: a. Filter models based on global quality scores (pLDDT >70 for high-confidence) b. Identify best model for each target using top 1 loss optimization c. Flag low-confidence regions (pLDDT <50) for experimental validation priority

Performance Optimization: Based on benchmark testing, a 9.6TB FSx for Lustre file system with g4dn.4xlarge instances can process approximately 200-250 structures per day [4]. Scaling to 19.2TB enables processing of 400-500 structures daily but increases infrastructure costs.

Successful implementation of protein model quality assessment requires access to specific databases, software tools, and computational resources. The following table catalogues essential resources for researchers working in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Protein Model Quality Assessment

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt [1] | Database | Comprehensive protein sequence and functional information | https://www.uniprot.org/ |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [2] | Database | Experimentally determined protein structures | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [3] | Database | Pre-computed AlphaFold predictions for multiple proteomes | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

| CASP Assessment Results [9] | Benchmark Data | Standardized evaluation data for method comparison | https://predictioncenter.org/ |

| DeepUMQA2 [3] | Software | State-of-the-art quality assessment using deep learning | Available from research group |

| ProQ3/ProQ4 [3] | Software | Model quality assessment tools | https://proq3.bioinfo.se/ |

| ModFOLD8 [3] | Software | Server for model quality assessment | https://www.reading.ac.uk/bioinf/ModFOLD/ |

| AlphaFold Server [6] | Software Platform | Free access to AlphaFold3 for non-commercial research | https://alphafoldserver.com/ |

| PDB100 [3] | Database | Clustered PDB sequences (<100% identity) for template search | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| UniClust30 [3] | Database | Clustered protein sequences (<30% identity) for MSA | https://www.uniprot.org/help/uniref |

The sequence-structure gap presents both a fundamental challenge and a compelling opportunity for computational structural biology. While AI-based structure prediction methods like AlphaFold have dramatically expanded the structural universe, their effective application in biological research and drug discovery depends critically on robust quality assessment protocols. The development of sophisticated MQA methods, particularly those leveraging deep learning architectures, has enabled researchers to distinguish reliable models from inaccurate predictions and to identify the most accurate structural models from ensembles of possibilities.

Looking forward, several emerging trends promise to further advance the field. The integration of protein dynamics into quality assessment frameworks represents a crucial next step, as static structures cannot fully capture functional mechanisms [5]. Additionally, methods for assessing complex structures—including protein-ligand complexes, multi-chain assemblies, and membrane proteins—require continued refinement [6]. Finally, the development of explainable AI approaches for MQA will enhance trust and adoption within the broader biological research community, providing intuitive insights into why specific models are deemed high or low quality [3].

As these computational methods mature, the sequence-structure gap will increasingly transform from an impediment to a gateway—enabling researchers to rapidly generate structural hypotheses from sequence information alone, accelerating both fundamental biological discovery and the development of new therapeutic agents for human disease.

In structural biology, computational protein structure prediction has become an indispensable tool, with methods like AlphaFold2 demonstrating remarkable accuracy [10]. However, the reliability of any predicted model must be rigorously evaluated before it can be applied in downstream research or drug development. This necessitates robust, quantitative quality metrics that can assess how closely a computational model resembles the true, experimentally determined structure of a protein. Among the most critical and widely adopted metrics in the field are the Global Distance Test-Total Score (GDT-TS), Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD), and Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT) [11]. These metrics form the cornerstone of protein model validation, both in blind prediction experiments like the Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) and in practical research applications. This protocol outlines the detailed methodologies for employing these metrics, providing a standardized framework for researchers to assess the quality of protein structural models accurately.

Metric Definitions and Quantitative Interpretation

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and interpretation guidelines for the three primary quality metrics.

Table 1: Core Protein Model Quality Metrics

| Metric | Full Name | Type | Range | Key Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDT-TS | Global Distance Test-Total Score | Global | 0-100% (or 0-1) | High (>90%): High accuracy, very similar/identical structures [10].Medium (50-90%): Acceptable, depends on task resolution [11].Low (<50%): Low accuracy, unreliable prediction [11]. |

| RMSD | Root-Mean-Square Deviation | Global | 0 Å to ∞ | Low (<2 Å): High atomic-level accuracy, highly similar structures [11].Medium (2-4 Å): Residue-level accuracy acceptable for some tasks [11].High (>4 Å): Low domain-level accuracy, very different structures [11]. |

| lDDT | Local Distance Difference Test | Local | 0-100 | High (>80): High local accuracy, reliable side chains [11].Medium (50-80): Acceptable local accuracy [11].Low (<50): Low local confidence, likely disordered regions [11]. |

Global Distance Test-Total Score (GDT-TS)

GDT-TS is a global metric that quantifies the overall structural similarity between two protein structures with known amino acid correspondence [11]. It measures the largest set of Cα atoms in the model structure that fall within a defined distance cutoff from their positions in the reference (experimental) structure after optimal superposition. The algorithm calculates this percentage across multiple distance cutoffs (typically 1, 2, 4, and 8 Å), and the final GDT-TS score is the average of these four values [12] [11]. A higher GDT-TS score indicates a greater proportion of the model's backbone is structurally congruent with the reference. This metric is particularly valuable for assessing the overall topological correctness of a protein fold.

Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD)

RMSD is one of the most traditional metrics for quantifying the average magnitude of displacement between equivalent atoms (typically Cα atoms) in two superimposed protein structures [11]. It is calculated as the square root of the average of the squared distances between all matched atom pairs. An RMSD of 0 indicates a perfect match. While intuitive, a key limitation of RMSD is its sensitivity to large errors in a small number of residues and its dependence on the length of the protein. It is most informative when comparing highly similar structures, as it can be heavily skewed by conformational differences in flexible loops or terminal regions.

Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT)

lDDT is a local stability measure that assesses the quality of a model without the need for a global superposition, making it robust to domain movements [11]. It evaluates the conservation of inter-atomic distances in the model compared to the reference structure. The score is calculated by checking the agreement of distances between atoms within a certain cutoff in the model versus the reference. A per-residue version, pLDDT, is famously output by AlphaFold2 and provides a reliability score for each residue in a predicted model, helping researchers identify well-modeled regions and potentially disordered segments [11]. This makes lDDT exceptionally useful for judging local reliability and model utility for specific applications like active site analysis.

Experimental Protocol for Metric Calculation

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for assessing the quality of a predicted protein model using the three core metrics.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Input Structure Preparation

- Objective: Ensure model and reference structures are in a compatible state for comparison.

- Methods:

- Obtain the predicted protein model (e.g., from AlphaFold, Rosetta, I-TASSER) and the experimental reference structure (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank, PDB).

- Isolate the protein chains to be compared. Remove non-protein atoms (water, ions, ligands) unless the analysis specifically requires them.

- Ensure the sequence of the model and the reference structure are identical or can be unambiguously aligned. Trim any residues that are not present in both structures.

Step 2: Structural Alignment

- Objective: Spatially superimpose the model onto the reference structure to minimize the overall coordinate differences.

- Methods:

- Select atoms for alignment, typically Cα atoms for the protein backbone.

- Use a robust superposition algorithm, such as the Kabsch algorithm, to find the optimal rotation and translation that minimizes the RMSD between the equivalent atoms.

- Apply the calculated transformation to the entire model structure.

Step 3: RMSD Calculation

- Objective: Quantify the average global deviation after superposition.

- Methods:

- Using the superimposed structures from Step 2, extract the coordinates of equivalent Cα atoms.

- Calculate the RMSD using the standard formula:

RMSD = √[ Σ( (xi - xrefi)² + (yi - yrefi)² + (zi - zref_i)² ) / N ]

where

iiterates over all N paired atoms. - Record the global RMSD value. Optionally, calculate RMSD for specific domains or secondary structure elements to gain localized insights.

Step 4: GDT-TS Calculation

- Objective: Measure the percentage of the structure that is modeled within different thresholds of accuracy.

- Methods:

- Using the superimposed structures, calculate the Euclidean distance for each pair of equivalent Cα atoms.

- For a series of distance cutoffs (e.g., 1Å, 2Å, 4Å, 8Å), determine the percentage of residues whose Cα atoms fall within that cutoff in the model compared to the reference.

- The GDT-TS score is the average of these four percentages: GDT-TS = (P1 + P2 + P4 + P8) / 4.

Step 5: lDDT Calculation

- Objective: Assess local distance agreement without the influence of global domain shifts.

- Methods:

- Do not perform a global superposition. The calculation is done on the native coordinates.

- For each residue in the model, identify all atoms within a specified distance cutoff (e.g., 15 Å).

- Compare the distances between all pairs of these atoms in the model versus the reference structure.

- The lDDT score is the fraction of these atom-pair distances that are below a defined deviation threshold in the model. A per-residue pLDDT score is also computed.

Step 6: Integrated Analysis and Reporting

- Objective: Synthesize the results from all metrics to form a holistic judgment of model quality.

- Methods:

- Cross-Reference Metrics: Use the quantitative interpretation guidelines in Table 1.

- Identify Discrepancies: A high RMSD but medium GDT-TS may indicate a generally correct fold with a few large errors. A low pLDDT in specific regions (e.g., loops) flags localized unreliability.

- Generate a Report: Create a summary that includes the global scores (GDT-TS, RMSD), the overall lDDT, and a visualization of the pLDDT profile mapped onto the 3D model.

Table 2: Key Software Tools and Databases for Quality Assessment

| Category | Item/Resource | Brief Function Description | Example Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Tools | Quality Assessment Servers | Web servers that calculate multiple quality metrics from a submitted model. | Qprob [12], GOBA [13], ProQ2 [12] |

| Structural Biology Suites | Software packages with built-in commands for structure comparison and metric calculation. | UCSF ChimeraX, PyMOL, VMD | |

| Standalone Scoring Tools | Specialized programs or scripts for high-throughput model evaluation. | TM-score calculator [11] | |

| Databases | Experimental Structures | Repository of experimentally determined structures used as gold-standard references. | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [14] [15] |

| Prediction Results | Archives of models from community-wide experiments for benchmarking. | CASP Prediction Center [10] | |

| Computational Frameworks | Structure Prediction Systems | Advanced pipelines that generate models and provide intrinsic quality estimates (e.g., pLDDT). | AlphaFold2 [16] [10], AlphaFold3 [16] [17], NuFold (for RNA) [15], DeepSCFold (for complexes) [17], I-TASSER [14] |

In the field of computational biology, protein model Quality Assessment (QA) is a crucial procedure for evaluating the accuracy of computationally predicted protein tertiary structures without knowledge of the native structure. This process is fundamental for selecting the most reliable structural models from a pool of decoys generated by prediction algorithms, thereby determining a model's utility for downstream applications in biological research and drug development [18] [19]. The performance of QA methods is typically measured by their correlation between predicted and true quality scores (often GDT-TS) and their capability to select the best-quality models from a set of decoys [12].

QA methods have coalesced into three distinct methodological pillars, each with characteristic strengths, limitations, and optimal use cases. Single-model methods assess quality based solely on the information contained within an individual protein model. Quasi-single-model methods leverage external information from known protein structures (templates) to assess a query model. Multi-model methods (or consensus methods) evaluate a model by comparing it against an ensemble of other predicted models for the same target [20] [19]. The choice of approach involves critical trade-offs between accuracy, data requirements, and computational expense, making the understanding of all three pillars essential for researchers.

The Single-Model Approach

Core Principles and Applications

The single-model approach to quality assessment predicts the quality of a protein structure using only the features derived from that single model itself, without any reference to other predicted models or external templates [20] [18]. This independence makes it indispensable in scenarios where only one or a few models are available, when the pool of models is dominated by low-quality decoys that could mislead consensus methods, or when computational efficiency is a priority for assessing thousands of models [21] [18] [12].

The primary strength of this approach is its self-contained nature, which provides robustness against poor model pools. However, its performance can sometimes lag behind template-based or consensus methods when high-quality references are available [12].

Representative Methods and Performance

Recent years have seen significant advances in single-model QA methods, many of which employ machine learning techniques.

- Qprob utilizes a novel probability density framework. It calculates the absolute error for each of 11 protein feature values against true GDT-TS scores and uses these errors to estimate a probability density distribution for quality assessment. When tested in CASP11, it demonstrated strong performance, particularly on models of "hard" targets [12].

- MASS employs the random forests algorithm trained on 70 diverse features, including six novel statistical potentials developed by its authors (e.g., pseudo-bond angle potential, accessible surface potential). MASS reportedly outperformed most of the top-performing single-model methods from CASP11 across multiple evaluation metrics [19].

- ProQ2 and ProQ3 are well-known methods that use support vector machines (SVM) with features such as Rosetta energy terms, achieving top-tier performance in community benchmarks [19].

Table 1: Representative Single-Model QA Methods and Features

| Method | Core Algorithm | Key Input Features | Reported Performance (Correlation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qprob [12] | Feature-based Probability Density Functions | 11 features including DFIRE2, RWplus, RFCBSRS_OD, ModelEvaluator, and DOPE scores. | CASP11: Correlation ~0.64 (Stage 1), ~0.40 (Stage 2) |

| MASS [19] | Random Forests | 70 features in 7 categories, including novel MASS potentials, secondary structure agreement, and Rosetta energies. | Outperformed most CASP11 single-model methods. |

| ProQ2/ProQ3 [19] | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Rosetta energy terms, structural features. | Ranked among top methods in CASP benchmarks. |

Experimental Protocol for Single-Model QA using Feature Extraction and Machine Learning

This protocol outlines the use of a machine learning-based single-model QA method, such as MASS or Qprob, to assess the global quality of an individual protein structure model. The output is a predicted global quality score (e.g., GDT-TS).

Materials:

- Input: A single protein model in PDB format.

- Software: A QA tool implementation (e.g., MASS, Qprob). Secondary structure prediction tools (e.g., SCRATCH). Statistical potential calculators (e.g., for RWplus, GOAP, DFIRE). The Rosetta software suite (if using energy terms).

Procedure:

- Feature Extraction: Execute computational tools to calculate a comprehensive set of features from the input model.

- Structural Compatibility: Calculate statistical potential scores (e.g., DOPE, DFIRE, RWplus) [12] [19].

- Physicochemical Properties: Assign secondary structure and solvent accessibility (e.g., using STRIDE). Compare with sequence-based predictions (e.g., from SCRATCH) to compute Q3 and SOV scores [19].

- Geometric Properties: Compute the radius of gyration, residue-residue contact patterns, and torsion angles [19].

- Evolutionary Information: Calculate features like pseudo-amino acid composition from the sequence [19].

- Feature Vector Assembly: Compile all calculated features into a standardized feature vector. Normalize values to account for dependencies like protein sequence length [12].

- Quality Score Prediction: Input the feature vector into the pre-trained model (e.g., Random Forest for MASS, probability density function for Qprob). The model will output a predicted global quality score for the protein model.

- Validation (Benchmarking): To evaluate the method's performance on a set of models with known native structures, calculate the Pearson correlation between the predicted scores and the true GDT-TS scores across the dataset.

The Quasi-Single-Model Approach

Core Principles and Applications

Quasi-single-model methods represent a hybrid approach. They assess a query model primarily on its own but augment this assessment with information derived from known protein structures (templates) found in databases like the PDB, or from a small set of generated reference models [20]. These methods are particularly valuable when some evolutionary or structural information is available for the target protein, but generating a large pool of prediction decoys is not feasible.

A key advantage is their ability to leverage the known quality of experimentally solved structures, which can guide the assessment more reliably than ab initio single-model features alone. They can outperform pure single-model methods when accurate templates are available but are limited by the quality and coverage of the template database [20].

Representative Methods and Performance

- MUfoldQA_S: This method directly uses fragments of known protein structures with similar sequences as templates. It finds these templates via sequence-based searches (using BLAST and HHsearch) against the PDB, scores them based on E-value, sequence identity, and coverage, and then uses the best-matching templates to evaluate the query model without building a full reference model. It introduces a GDT-TS style score calculation that works for variable-length fragments [20].

- Methods for Poor Quality Models: Some specialized quasi-single methods focus on the challenging task of assessing poor-quality models, often generated by ab initio prediction. One such method uses a simple linear combination of only six features, including contact prediction and statistical potentials, to avoid the noise introduced by less reliable features in low-quality decoys [18].

Table 2: Representative Quasi-Single-Model QA Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Source of External Information | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| MUfoldQA_S [20] | Template-based QA using known protein fragments. | Protein Data Bank (PDB), via BLAST/HHsearch. | Uses native protein fragments directly; GDT-TS style scoring for variable lengths. |

| Linear Model for Poor Quality [18] | Linear combination of few features. | Contact predictions and other simple features. | Optimized for poor quality model pools; reduces complexity and feature noise. |

Experimental Protocol for Quasi-Single-Model QA using Template-Based Assessment

This protocol describes the process for a template-based quasi-single method, such as MUfoldQA_S, to evaluate a query protein model.

Materials:

- Input: A query protein model and its amino acid sequence.

- Software: The MUfoldQA_S software. Sequence search tools (BLAST, HHsearch). A curated non-redundant protein structure database (e.g., from PDB).

Procedure:

- Template Acquisition:

- Use the target protein sequence to query a protein structure database (e.g., PDB) using both BLAST and HHsearch to find proteins with similar sequences [20].

- For BLAST, run multiple iterations with an E-value threshold (e.g., 11,000) to ensure sufficient template coverage [20].

- Extract matching protein fragments as potential templates.

- Template Scoring and Selection:

- Calculate a template quality score (T) for each hit. A representative formula is: T = (3 - log10 E) · I · C where E is the E-value, I is the percentage of identical sequences, and C is the coverage ratio (template length / target length) [20].

- Sort all templates from both searches based on their T score.

- Query Model Evaluation:

- For the selected top templates, compute the local similarity between the query model's structure and the template's structure for aligned regions.

- A heuristic function is applied to differentiate accurate templates from poor ones (e.g., using BLOSUM-based metrics) [20].

- Global Score Calculation:

- Combine the local similarity scores from the best-matching templates into a single, global quality score for the query model, typically through a non-linear combination function [20].

The Multi-Model (Consensus) Approach

Core Principles and Applications

Multi-model, or consensus, quality assessment methods are based on the structural principle that similar structural features recurrently predicted by multiple independent methods are more likely to be correct. These methods evaluate a query model by comparing it to a set of other predicted models (a "model pool") for the same protein target [20] [12]. The underlying assumption is that the native structure is the central point in the structural space of predictions, so models closer to the center of the model pool are likely to be more accurate [20].

The primary strength of consensus methods is their high accuracy when the model pool is large and contains a significant number of high-quality models. However, their major weakness is their susceptibility to failure when the model pool is small or dominated by low-quality, but structurally similar, decoys. Their computational cost also scales with the square of the number of models (O(n²)) [18].

Representative Methods and Performance

- Naïve Consensus: This is a foundational method where the quality score for a query model is simply its average similarity (e.g., average GDT-TS) to all other models in the pool. While simple, it is powerful but suffers from the "majority failure" problem [20].

- MUfoldQAC: This method enhances the consensus approach by integrating information from protein templates. It uses the intermediate scores from MUfoldQAS as weights to differentiate high-quality segments of reference models from low-quality ones. This creates a weighted consensus score that is more robust to poor model pools [20].

- MUfoldQAG: A more recent advanced method designed to simultaneously optimize two key QA metrics: Pearson correlation and average GDT-TS difference. It combines two algorithms: one (MUfoldQAGp) that maximizes Pearson correlation by using information from templates and reference models, and another (MUfoldQA_Gr) that uses adaptive retraining to minimize the average GDT-TS difference. This hybrid approach ranked highly in CASP14 [22].

Table 3: Representative Multi-Model QA Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Key Innovation / Robustness Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Naïve Consensus [20] | Average similarity to all models in the pool. | Simple and effective with good pools; fails with poor pools. |

| MUfoldQA_C [20] | Weighted consensus. | Uses template-based (MUfoldQA_S) scores to weight reference models. |

| MUfoldQA_G [22] | Hybrid optimization of correlation and loss. | Combines template-based scoring with adaptive machine learning. |

Experimental Protocol for Multi-Model QA using Weighted Consensus

This protocol details the steps for a weighted consensus QA method, such as MUfoldQA_C, which improves upon the naive consensus by using auxiliary information.

Materials:

- Input: A pool of predicted protein models for the same target.

- Software: A multi-model QA tool (e.g., MUfoldQA_C). A structure alignment tool (e.g., for calculating TM-scores or GDT-TS).

Procedure:

- Reference Model Selection:

- From the input model pool, select a subset of top-ranking models to serve as references. This selection can be based on a preliminary, fast quality assessment method [20].

- Reference Model Weighting:

- Calculate a weight for each selected reference model. This is the critical step that differentiates advanced methods from naive consensus.

- In MUfoldQAC, this is done by running the quasi-single method MUfoldQAS on each reference model. The resulting score determines the model's weight, prioritizing models that are likely accurate based on external template information [20].

- Pairwise Comparison:

- For the query model, perform a structural alignment (e.g., calculating GDT-TS or TM-score) against each of the weighted reference models.

- Consensus Score Calculation:

- Compute the final quality score for the query model as the weighted average of its similarity scores to the reference models, using the weights assigned in Step 2 [20].

- Formula:

Weighted_Score = (Σ (weight_i * similarity_score_i)) / Σ weight_i

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Software and Data Resources for Protein Model QA

| Resource Name | Type / Category | Primary Function in QA |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Primary repository of experimentally solved protein structures used for template-based methods and training [20]. |

| CASP Datasets | Benchmark Data | Community-wide blind test datasets and results used for training new QA methods and benchmarking their performance [21] [12] [19]. |

| PISCES Database | Curated Database | A curated subset of the PDB used for normalizing energy scores and removing sequence-length dependencies in feature calculation [12]. |

| Rosetta | Software Suite | Provides a set of energy functions and terms that are commonly used as features in machine learning-based QA methods [18] [19]. |

| BLAST / HHsearch | Software Tool | Used for sequence-based searches against protein databases to find homologous templates for quasi-single-model methods [20]. |

| LGA | Software Tool | A program for structure alignment and comparison; used to calculate the true GDT-TS score of a model against its native structure for benchmarking [19]. |

| SCRATCH | Software Tool | Predicts secondary structure and solvent accessibility from amino acid sequence; used to generate features related to the agreement between prediction and model [19]. |

| STRIDE | Software Tool | Assigns secondary structure and solvent accessibility from a 3D structural model; used to generate "actual" structural features for comparison [19]. |

The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) is a community-wide experiment that has fundamentally advanced the field of protein structure modeling through rigorous blind testing and independent evaluation. Established in 1994 and conducted biennially, CASP provides an objective framework for assessing the accuracy of computational methods that predict protein three-dimensional structures from amino acid sequences [23]. This experiment serves as both a benchmarking challenge and a catalyst for innovation, particularly in quality assessment (QA) methodologies for protein structural models. By creating a standardized evaluation platform where research groups worldwide test their prediction methods against unpublished experimental structures, CASP has driven remarkable progress in computational structural biology, culminating in recent breakthroughs through deep learning approaches like AlphaFold [24] [25].

The CASP Experimental Framework

Core Principles and Design

CASP operates on a double-blind principle to ensure unbiased evaluation. Target proteins are selected from structures soon-to-be solved by X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy, or from recently solved structures held in confidence by the Protein Data Bank [23]. This guarantees that predictors cannot have prior knowledge of the experimental structures, creating a rigorous testing environment. The experiment attracts over 100 research groups globally, with participants often suspending other research activities for months to focus on CASP preparations [23].

The organizational timeline follows a structured biennial schedule. CASP15, for example, began registration in April 2022, released the first targets in May, concluded the modeling season in August, and held its evaluation conference in December 2022 [26]. This regular cycle allows for continuous assessment of methodological progress while providing the community with standardized performance benchmarks.

Evolution of Prediction Categories

CASP has dynamically adapted its assessment categories to reflect methodological developments and community needs, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Evolution of CASP Assessment Categories

| Category | Initial CASP | Current Status (CASP15) | Key Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tertiary Structure Prediction | Included | Included (core category) | Eliminated distinction between template-based and template-free modeling [26] |

| Secondary Structure Prediction | Included | Dropped after CASP5 | Deemed less critical with advancing methods [23] |

| Structure Complexes | CASP2 only | Continued via CAPRI collaboration | Separated to specialized assessment [23] |

| Residue-Residue Contact Prediction | Starting CASP4 | Not included in CASP15 | Category retired as methods matured [26] |

| Disordered Regions Prediction | Starting CASP5 | Continued | Ongoing importance for complex structures [27] |

| Model Quality Assessment | Starting CASP7 | Expanded scope | Increased emphasis on atomic-level estimates [26] |

| Model Refinement | Starting CASP7 | Not included in CASP15 | Category retired [26] |

| RNA Structures | Not included | New in CASP15 | Pilot experiment for RNA models and complexes [26] |

| Protein-Ligand Complexes | Not included | New in CASP15 | Pilot experiment for drug design applications [26] |

| Protein Ensembles | Not included | New in CASP15 | Assessing conformational heterogeneity [26] |

Quantitative Assessment Metrics and Performance Landscape

Primary Evaluation Metrics

The cornerstone of CASP evaluation is the quantitative comparison between predicted models and experimental reference structures. The primary metric is the Global Distance Test-Total Score (GDT-TS), which measures the percentage of well-modeled residues in the predicted structure compared to the target [23]. GDT-TS calculates the average percentage of Cα atoms that fall within specific distance cutoffs (1, 2, 4, and 8 Å) when superimposed on the experimental structure, providing a comprehensive measure of global fold accuracy [23] [25].

Additional metrics include:

- Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT): A residue-based scoring function that evaluates local structure quality without superposition

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures atomic positional differences after optimal alignment

- Template Modeling Score (TM-score): Metric that emphasizes topological similarity over local deviations

Performance Progression Across CASP Experiments

CASP has documented remarkable progress in prediction accuracy over its three-decade history, with particularly dramatic improvements in recent years, as quantified in Table 2.

Table 2: Evolution of Prediction Accuracy in CASP Experiments

| CASP Round | Year | Key Methodological Advance | Average GDT-TS (Difficult Targets) | Representative Group Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early CASPs | 1994-2004 | Homology modeling, threading | 20-40 (FM targets) | Various academic groups |

| CASP10 | 2012 | Molecular dynamics refinement | Moderate improvement | Limited impact on difficult targets [27] |

| CASP13 | 2018 | Deep learning introduction | ~60 (FM targets) | AlphaFold (group 427) [25] |

| CASP14 | 2020 | Deep learning transformation | ~85 (FM targets) | AlphaFold2 (group 427) [25] |

| CASP15 | 2022 | Widespread AlphaFold adoption | High accuracy across categories | Multiple groups using AF2 derivatives [26] |

The performance leap in CASP14 was particularly noteworthy, with AlphaFold2 achieving GDT-TS scores starting at approximately 95 for easy targets and finishing at about 85 for the most difficult targets [25]. This represented a fundamental shift, as approximately two-thirds of targets reached GDT-TS values where models are considered competitive with experimental structures in backbone accuracy [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for QA Assessment

Target Selection and Preparation

The CASP protocol begins with careful target selection and preparation, following a standardized workflow as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: CASP Experimental Workflow for QA Assessment

Target Identification and Validation:

- Solicitation: CASP organizers solicit protein sequences from structural biology laboratories worldwide for structures that are either soon-to-be solved or recently solved but not yet publicly released [23] [26]

- Confidentiality Assurance: Collaborating experimentalists provide structures that are kept on hold by the Protein Data Bank to prevent prior knowledge [23]

- Diversity Considerations: Targets are selected to represent various structural classes, including membrane proteins, multi-domain proteins, and complexes, with particular emphasis on structurally novel proteins [26]

Target Categorization Protocol:

- Difficulty Assessment: Targets are classified into categories based on similarity to known structures:

- TBM-Easy: Straightforward template-based modeling

- TBM-Hard: Difficult homology modeling

- FM/TBM: Remote structural homology

- FM: Free modeling with no detectable homology [25]

- Domain Parsing: Large proteins are divided into structural domains for granular evaluation [25]

- Evaluation Unit Definition: Targets are organized into evaluation units based on homology and structural integrity considerations [25]

Prediction and Evaluation Protocol

Model Submission Procedure:

- Registration: Participants register as either human-expert teams or automated servers [27]

- Sequence Release: Target sequences are distributed to registered predictors without structural information [23]

- Timed Submission:

- Server predictors: 72-hour deadline

- Human-expert teams: 3-week deadline [27]

- Format Compliance: Models must adhere to standardized file formats specified by CASP organizers [26]

Quality Assessment Methodology:

- Structural Alignment: Predicted models are systematically superimposed on experimental structures using optimal least-squares fitting [23]

- Metric Calculation:

- Statistical Analysis: Perform significance testing to distinguish meaningful methodological differences from random variations

Assessment Specialization by Category:

- Single Domain Structures: Focus on global and local backbone accuracy [26]

- Multimeric Complexes: Evaluate interface accuracy and subunit interactions [26]

- RNA Structures: Pilot assessment of nucleic acid modeling (CASP15) [26]

- Ligand Binding Sites: Assess functional annotation accuracy [27]

Successful participation in CASP requires a comprehensive toolkit of computational resources and methodological approaches, as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Structure QA

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Function in QA Assessment | CASP Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template Identification | HHsearch, BLAST, Protein Threading | Detect structural homologs for comparative modeling | Foundation for TBM category [23] |

| De Novo Structure Prediction | Rosetta, AlphaFold2, RosettaFold | Generate structures without templates | Critical for FM category; revolutionary impact in CASP13/14 [23] [25] |

| Model Refinement | Molecular Dynamics, MODREFINER | Improve initial model accuracy | Former dedicated category; now integrated [27] |

| Quality Estimation | Model Quality Assessment Programs (MQAPs) | Predict accuracy without reference structure | Dedicated category in CASP7-14; now emphasized at atomic level [26] |

| Validation Metrics | GDT-TS, lDDT, TM-score, RMSD | Quantify model accuracy against reference | Standardized evaluation across CASP [23] [25] |

| Specialized Assessment | CAPRI criteria, RNA-specific metrics | Evaluate complexes and nucleic acids | Expanding scope in recent CASPs [26] |

| Data Resources | Protein Data Bank (PDB), UniProt, Structural Genomics Data | Provide templates and training data | Essential for method development [27] |

Impact on Methodological Advancement and Future Directions

Catalyzing Methodological Breakthroughs

CASP's structured evaluation framework has directly driven innovation in protein structure prediction quality assessment. The most notable example is the development of AlphaFold, which first demonstrated breakthrough performance in CASP13 (2018) and achieved experimental-level accuracy in CASP14 (2020) [24] [25]. According to CASP co-founder John Moult, AlphaFold2 scored approximately 90 on a 100-point scale of prediction accuracy for moderately difficult protein targets [23]. This transformation was so profound that in CASP15 (2022), virtually all high-ranking teams used AlphaFold or its modifications, even though DeepMind did not formally enter the competition [23].

The independent assessment process has also refined understanding of remaining challenges. Analysis of CASP14 results revealed that disagreements between computation and experiment increasingly reflect limitations in experimental methods rather than computational approaches, particularly for lower-resolution X-ray structures and cryo-EM determinations [25]. This shift underscores the achievement of computational methods that now rival experimental accuracy for many single-domain proteins.

Evolving Challenges and Research Directions

Despite remarkable progress, CASP continues to identify new frontiers for QA advancement, as visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Evolving Challenges in Protein Structure QA

CASP has strategically adapted its assessment categories to focus on these emerging challenges. CASP15 introduced several new evaluation categories while retiring others that have become essentially solved problems [26]. The new emphasis includes:

- Protein Assemblies: Evaluating accuracy of domain-domain, subunit-subunit, and protein-protein interactions [26]

- RNA Structures: Pilot assessment of RNA models and protein-RNA complexes in collaboration with RNA-Puzzles [26]

- Protein-Ligand Complexes: Assessing binding site prediction accuracy, with implications for drug design [26]

- Protein Conformational Ensembles: Developing methods to predict and assess structural heterogeneity and dynamics [26]

These evolving priorities reflect the field's transition from predicting static single-domain structures to modeling biologically relevant complexes and dynamic conformational states, requiring increasingly sophisticated QA methodologies.

The CASP experiment demonstrates how community-wide benchmarking fundamentally accelerates methodological progress in structural bioinformatics. Through its rigorous blind testing protocols, standardized evaluation metrics, and independent assessment framework, CASP has transformed protein structure prediction from an academic challenge to a practical tool with applications across biomedical research. The experiment's evolving categories continue to identify new frontiers, ensuring that QA methodologies advance to meet emerging needs in structural biology. As computational methods approach and sometimes surpass experimental accuracy for certain protein classes, CASP's role in validating and directing these advances becomes increasingly vital to the research community.

The reliability of computational protein models is paramount for their successful application in biomedical research. Model Quality Assessment (MQA) serves as the critical gateway that determines whether a predicted structure can be trusted for downstream tasks such as function prediction, ligand binding site identification, and drug design. In structural bioinformatics, MQA methods evaluate the local and global accuracy of protein models, providing confidence scores that help researchers prioritize models for further investigation [28]. The connection between model quality and functional insight is bidirectional: while high-quality structures enable accurate function prediction, evolutionary information derived from sequences can in turn inform the identification of functionally important residues, even in the absence of structural data [29]. This interplay forms the foundation for deploying computational models in biomedical applications, where the ultimate goal is to translate structural insights into therapeutic advancements.

Application Notes: From Quality Assessment to Functional Insight

Quantitative Benchmarks for Model Quality and Function Prediction

Table 1: Performance of Protein Function Prediction Methods in Community Assessments

| Assessment | Top Method Performance (Fmax) | Key Advancements | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAFA1 [30] | Molecular Function: ~0.50Biological Process: ~0.40 | Outperformed naive BLAST transfer | Performance varied by ontology and target type |

| CAFA2 [31] | Molecular Function: >0.50Biological Process: >0.40Cellular Component: >0.45 | Expanded to 3 GO ontologies and HPO; introduced limited-knowledge targets | Method performance remains ontology-specific |

| CASP16 EMA [28] | Quality estimates for multimeric assemblies | Assessment of global/local quality for complexes | Handling of conformational flexibility |

The Critical Assessment of Functional Annotation (CAFA) experiments have demonstrated consistent improvement in computational function prediction methods. Between CAFA1 and CAFA2, top-performing methods showed enhanced accuracy in predicting Gene Ontology terms, attributable to both growing experimental annotations and improved algorithms [31] [30]. These assessments reveal that while modern methods substantially outperform first-generation approaches like simple BLAST transfer, their performance remains dependent on the specific ontology being predicted and the nature of the target proteins.

AI-Enhanced Quality Assessment for Experimental Structures

The rise of cryo-electron microscopy has created new challenges for model quality assessment. AI-based approaches such as DAQ now provide residue-level quality estimates for cryo-EM models by learning local density features, enabling identification of errors in regions of locally low resolution where manual model building is most prone to inaccuracies [32]. These tools represent a significant advancement over conventional validation scores that primarily assess map-model agreement and protein stereochemistry, offering automated refinement capabilities that can fix local errors identified during assessment.

Protocols for Assessing Model Quality and Function

Protocol 1: Residue-Level Functional Site Prediction Using PhiGnet

Purpose: To identify functional residues and annotate protein functions directly from sequence using evolutionary information.

Principle: This protocol leverages statistics-informed graph networks to quantify the functional significance of individual residues based on evolutionary couplings and residue communities, enabling function prediction without structural information [29].

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Provide a single protein amino acid sequence in FASTA format.

- Embedding Generation: Process the sequence through the pre-trained ESM-1b model to generate residue embeddings that capture evolutionary information.

- Graph Construction:

- Represent residues as graph nodes using the embedding vectors

- Compute Evolutionary Couplings as edges between co-varying residues

- Identify Residue Communities representing hierarchical interactions

- Dual-Channel Processing: Feed the graph through two stacked Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs):

- Channel 1 processes Evolutionary Coupling edges

- Channel 2 processes Residue Community edges

- Functional Annotation: Pass the processed information through fully connected layers to generate probability scores for Gene Ontology terms and Enzyme Commission numbers.

- Activation Scoring: Calculate gradient-weighted class activation maps to assign functional significance scores to individual residues.

- Validation: Compare high-scoring residues (activation score ≥0.5) against known functional sites in databases like BioLip [29].

Applications: This protocol successfully identified functional residues in multiple test proteins including cPLA2α, Ribokinase, and mutual gliding-motility protein (MgIA), with approximately 75% accuracy in predicting significant sites at the residue level [29].

Protocol 2: Quality Assessment for Protein Complexes (CASP16 EMA Framework)

Purpose: To evaluate the accuracy of predicted protein complex structures through both global and local quality metrics.

Principle: This protocol implements the Evaluation of Model Accuracy framework from CASP16, which assesses multimeric assemblies through multiple modes of quality estimation [28].

Procedure:

- Model Selection:

- For QMODE1: Submit global quality estimates for entire assemblies

- For QMODE2: Provide local quality estimates per residue

- For QMODE3: Identify top 5 models from thousands of candidates

- Reference Structure Preparation: Obtain or generate experimental reference structures when available.

- Structural Alignment: Perform sequence-dependent or sequence-independent superposition using algorithms like LGA.

- Metric Calculation:

- Calculate Global RMSD for Cα atoms (noting limitations with flexible regions)

- Compute Contact-Based Measures (e.g., residue contact maps)

- Determine Interface Quality Scores for complexes

- Statistical Analysis: Compare quality measures against:

- Native structure distributions (0-1.2Å RMSD for experimental pairs)

- Baseline methods (BLAST, naive function transfer)

- Confidence Assignment: Assign local confidence scores for functional site residues.

- Functional Correlation: Map high-quality regions to known functional sites.

Applications: This protocol was successfully applied in CASP16 to evaluate methods like MassiveFold, revealing strengths and limitations in predicting quality for multimeric assemblies [28].

Table 2: Protein Structure Comparison Measures for Quality Assessment

| Measure Type | Specific Metrics | Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance-Based | Global RMSDLocal RMSDDistance-Dependent Scoring | Intuitive units (Å)Easy to calculate | Initial model screeningRigid core assessment |

| Contact-Based | Residue Contact MapsInterface Contact AccuracyAL0 Score | Robust to flexibilityBiologically relevant | Binding site evaluationComplex interface quality |

| Superimposition-Independent | TM-ScoreGDT-TSLocal/Global Alignment (LGA) | Handles domain movementsLess sensitive to outliers | Flexible protein assessmentDomain-level accuracy |

Protocol 3: Experimental-Data Guided Modeling for Challenging Targets

Purpose: To integrate sparse experimental data with computational modeling for structurally challenging proteins.

Principle: This protocol combines experimental constraints from techniques like cryo-EM, NMR, and mass spectrometry with computational sampling to determine structures of disordered proteins, complexes, and rare conformations [33].

Procedure:

- Experimental Data Collection:

- Obtain cryo-EM density maps (medium to low resolution)

- Collect NMR chemical shifts and residual dipolar couplings

- Generate cross-linking mass spectrometry data

- Constraint Processing: Convert experimental data into spatial restraints.

- Computational Sampling:

- Generate initial models using template-based (threading) or template-free (fragment) approaches

- Employ Direct Coupling Analysis for evolutionary constraints

- Utilize molecular dynamics simulations (discrete MD, all-atom MD)

- Ensemble Refinement: Iteratively refine structures against experimental restraints.

- Quality Validation:

- Assess restraint satisfaction statistics

- Evaluate model ensemble diversity

- Calculate free energy landscapes

- Functional Annotation: Map functional sites based on conserved regions in the ensemble.

Applications: This approach has proven particularly valuable for characterizing disordered proteins, molecular complexes with flexible regions, and ligand-induced conformational changes [33].

Table 3: Key Resources for Protein Model Quality Assessment and Function Prediction

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Assessment Servers | ModFOLD4 [28]DAQ [32] | Global/local quality scoresCryo-EM model validation | Initial model screeningExperimental structure validation |

| Function Prediction Tools | PhiGnet [29]CAFA-tested methods [31] | Residue-level function annotationGO term prediction | Functional site identificationGenome annotation |

| Benchmark Data Sets | CASP/CAFA Targets [28] [31]BioLip [29] | Method evaluationExperimental functional sites | Algorithm developmentPrediction validation |

| Structural Databases | PDBAlphaFold DBUniProt [29] | Experimental structuresPredicted modelsSequence information | Template sourcingModel buildingEvolutionary analysis |

The integration of robust model quality assessment protocols into the structural biology workflow is essential for reliable translation of computational predictions to biomedical applications. As demonstrated through the protocols outlined here, modern MQA methods have evolved beyond simple geometric checks to provide sophisticated, AI-enhanced evaluation of both computational models and experimentally determined structures. The critical connection between model quality and functional insight enables researchers to identify confident predictions for downstream applications in drug design and therapeutic development. By implementing these standardized assessment protocols, researchers can make informed decisions about which models to trust for specific biomedical applications, ultimately accelerating the journey from protein sequence to functional understanding to therapeutic intervention.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Modern Quality Assessment Methods and Tools

In the field of computational structural biology, the quality assessment (QA) of predicted protein structures is a critical step for determining their utility in applications such as drug development and functional analysis. Single-model quality assessment methods operate on an individual protein structure model without relying on comparisons to other decoy models, making them computationally efficient and essential when only a few models are available. These methods can be broadly categorized as physics-based (relying on energy force fields) and knowledge-based (derived from statistical observed frequencies in known protein structures). This application note details the use of two prominent knowledge-based statistical potentials—DOPE (Discrete Optimized Protein Energy) and GOAP (Generalized Orientation-dependent All-atom Potential)—within a protocol designed for assessing poor-quality protein structural models, a common challenge in de novo structure prediction [18] [34].

Theoretical Background of Statistical Potentials

Statistical potentials, or knowledge-based scoring functions, are founded on the inverse Boltzmann principle. They derive an effective "potential of mean force" from the observed statistical distributions of structural features (e.g., atomic distances, angles) in a database of experimentally solved, high-quality protein structures. The core assumption is that native-like structures will exhibit features that are more frequently observed in real proteins, and thus receive a more favorable (lower) energy score [35].

- DOPE is a representative statistical potential that uses relevant statistics about atomic distances from known native structures, supported by probability theory [18] [34].

- GOAP is a more advanced, orientation-dependent, all-atom potential that incorporates both distance and angle-related statistical knowledge, serving as a valuable supplement to DOPE [18] [34].

An alternative information gain-based approach has been proposed, which offers a formalism independent of statistical mechanics. This method ranks protein models by evaluating the information gain of a model relative to a prior state of knowledge, and has been shown to outperform traditional statistical potentials in evaluating structural decoys [35].

Performance Benchmarking of QA Methods

The performance of DOPE and GOAP was benchmarked against other methods on a dataset of poor-quality models from CASP13, including ab initio models generated by Rosetta and official team submissions [34]. The standard evaluation metrics were the average per-target Pearson correlation (Corr.) between the predicted score and the actual quality (measured by GDT-TS or TM-score), and the quality of the top-ranked model (Top 1).

Table 1: Performance Comparison on CASP13 FM/TBM-hard Domains (Stage 2) [34]

| QA Method | Corr. (TM-score) | Top 1 TM-score | Corr. (GDT-TS) | Top 1 GDT-TS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours (Linear Combination) | 0.79 | 44.91 | 0.80 | 39.58 |

| ProQ3D | 0.61 | 42.26 | 0.62 | 36.52 |

| DeepQA | 0.55 | 34.23 | 0.55 | 29.33 |

| DOPE | 0.48 | 40.05 | 0.48 | 34.67 |

| GOAP | 0.40 | 33.70 | 0.42 | 28.94 |

| ProQ4 | 0.47 | 32.70 | 0.43 | 27.87 |

Table 2: Performance on Rosetta ab initio Models (Stage 1) [34]

| QA Method | Correlation | Top 1 GDT-TS |

|---|---|---|

| Ours (Random Search) | 0.42 | 27.02 |

| Ours (Linear Regression) | 0.42 | 27.42 |

| DOPE | 0.21 | 23.06 |

| GOAP | 0.21 | 23.48 |

| ProQ3D | 0.22 | 23.88 |

The data demonstrates that while DOPE and GOAP provide a baseline assessment, their performance, particularly in terms of correlation with the true model quality, is significantly lower on poor-quality model pools compared to more modern methods, including simple linear combinations of multiple features [18] [34].

Integrated Protocol for Assessing Poor-Quality Models

The following workflow outlines a protocol that leverages the strengths of multiple scoring functions, including DOPE and GOAP, to select the best models from a pool of predicted structures, such as those generated by ab initio prediction tools like Rosetta [18].

Step-by-Step Protocol

Input: A set of protein tertiary structure models in PDB format for a single target sequence.

Feature Extraction:

- Run the DOPE scoring function on each model to obtain a residue-averaged, whole-model DOPE score. Lower scores indicate more native-like structures [18] [34].

- Run the GOAP scoring function on each model to obtain a whole-model GOAP score. This provides complementary, orientation-dependent information [18] [34].

- Extract additional features. The referenced study used six key features [18]:

- Knowledge-based potentials: DOPE and GOAP.

- Contact prediction: A score evaluating the agreement between the model's contacts and predicted contacts.

- Secondary structure agreement: A score comparing the model's secondary structure to that predicted from sequence (e.g., using PSSpred).

- Physical properties: Features derived directly from the amino acid sequence and model geometry.

- Solvent accessibility: A score comparing predicted and model-calculated solvent accessibility.

Model Scoring:

- Combine the extracted features into a single composite score for each model. The referenced method demonstrates that a simple linear combination can be highly effective [18].

- The weights for the linear combination can be derived through a weighted random search or linear regression on a large dataset of known models (e.g., from CASP12). The study found both methods yielded similar, high-performing weights [18] [34].

- Formula:

Composite_Score = w1*DOPE + w2*GOAP + w3*Contact + w4*SS + w5*PhysChem + w6*SA

Model Ranking and Selection:

- Rank all models based on their composite score (e.g., ascending order if DOPE/GOAP are included, as lower energy is better).

- Select the top N models (e.g., top 5) for further analysis. The model with the best (lowest) composite score is the primary candidate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for the Protocol

| Item Name | Function / Application in Protocol | Source / Availability |

|---|---|---|

| DOPE | Statistical potential for scoring model quality based on atomic distances. | Integrated into MODELLER software suite. |

| GOAP | Orientation-dependent all-atom statistical potential for scoring. | Available as a standalone scoring function. |

| PSSpred | Secondary structure prediction from sequence for feature calculation. | Publicly available server and software. |

| Rosetta | Suite for protein structure prediction; used to generate ab initio decoys for benchmarking. | Academic license available. |

| CASP Datasets | Standardized benchmark datasets (e.g., CASP12, CASP13) for training and testing. | Publicly available from the CASP website. |

DOPE and GOAP are established, valuable knowledge-based potentials for protein model quality assessment. However, as benchmark data shows, their performance can be limited when applied in isolation to pools of poor-quality models, such as those generated by ab initio methods [34]. They remain sensitive to overall model geometry but may lack the granularity to identify the best among many incorrect structures.

The integrated protocol presented here, which uses a linear combination of DOPE, GOAP, and other relevant features like contact prediction, demonstrates that these classical potentials can contribute significantly to a more robust assessment strategy [18]. The key insights are:

- Contact prediction is a particularly informative feature for evaluating poor-quality models, as it provides constraints that are independent of the detailed atomic geometry [18].

- Simpler models like linear regression can outperform complex machine learning when trained on fewer, high-quality features, especially when some input features (e.g., from other prediction tools) are inherently noisy [18].

- This protocol provides a practical and effective framework for researchers and drug development professionals to select the most promising structural models from a large and variable-quality prediction set, thereby increasing the efficiency and reliability of downstream structural analysis.

Protein Model Quality Assessment (QA) is a critical step in computational structural biology, serving to evaluate the reliability of predicted protein models before they are used in downstream applications such as drug design or functional analysis [36]. QA methods are broadly categorized by their input requirements. Single-model methods evaluate a single protein structure, multi-model (or consensus) methods require a pool of decoy models for the same target, and quasi-single-model methods represent a hybrid approach [36]. Quasi-single-model methods, like MUfoldQAS, incorporate the strengths of consensus ideas—assessing how much a model conforms to known structural patterns—without requiring a user-provided model pool. Instead, they automatically generate their own reference set from known protein structures, offering a robust and user-friendly alternative [36]. The PSICA (Protein Structural Information Conformality Analysis) web service makes the MUfoldQAS method publicly available, providing an intuitive interface for researchers to assess their protein models [36].

Performance and Comparative Analysis

In the blind community-wide assessment CASP12, the MUfoldQAS method demonstrated top-tier performance. It ranked No. 1 in the protein model QA select-20 category based on the average difference between the predicted and true GDT-TS values of each model [36]. The closely related consensus method, MUfoldQAC, which uses MUfoldQAS scores as weights, also achieved top rankings in CASP12 [36]. More recently, in the CASP16 assessment, advanced single-model methods like DeepUMQA-X have shown outstanding performance, indicating the rapid evolution of the field [37]. The table below summarizes key quantitative data for MUfoldQAS and a contemporary method for context.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Data for Protein Model Quality Assessment Methods

| Method | Type | CASP Performance (Category) | Key Metric | Score/Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUfoldQA_S | Quasi-Single-Model | CASP12, No. 1 (Select-20) | Average Δ(GDT-TS) | Top Rank [36] |

| MUfoldQA_C | Consensus | CASP12, No. 1 (Select-20) | Top 1 Model GDT-TS Loss | Top Rank [36] |

| DeepUMQA-X | Single-Model & Consensus | CASP16, Top (nearly all tracks) | Performance across QMODE1/2/3 | Top Performance [37] |

Table 2: MUfoldQA_S Template Selection Heuristic (T-score) Components

| Component | Description | Role in Scoring |

|---|---|---|

| E-value | The BLAST expectation value; represents the number of alignments expected by chance. | Incorporated as (3 - log10(E)) to ensure a positive value for E < 1000 [36]. |

| Sequence Identity (I) | The percentage of identical residues at the same positions in the alignment. | A direct multiplier; higher identity increases the T-score [36]. |

| Coverage (C) | The ratio of the template length to the target sequence length. | A direct multiplier; better coverage increases the T-score [36]. |

Workflow and Methodology