A Researcher's Guide to Troubleshooting Poor RNA-seq Data Quality: From QC to Advanced Optimization

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose, troubleshoot, and resolve common and complex issues in RNA-seq data.

A Researcher's Guide to Troubleshooting Poor RNA-seq Data Quality: From QC to Advanced Optimization

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose, troubleshoot, and resolve common and complex issues in RNA-seq data. Covering the entire workflow from foundational principles to advanced validation, it details practical strategies for addressing critical problems like PCR duplicates, library preparation artifacts, and hidden quality imbalances. Readers will learn to implement robust quality control checks, optimize experimental parameters, select appropriate tools, and validate findings across sequencing platforms to ensure the generation of high-quality, biologically-relevant data for confident downstream analysis.

Understanding the Roots of RNA-seq Data Quality Issues

Defining Key RNA-seq Quality Metrics and Their Biological Impact

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the essential RNA-seq quality metrics I should check before downstream analysis?

A: Several key metrics provide a comprehensive picture of your RNA-seq data quality. The table below summarizes these essential metrics, their ideal ranges, and their biological significance. [1]

Table 1: Essential RNA-Seq Quality Metrics and Their Interpretation

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Ideal Range/Value | Biological & Technical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Counts | Mapping Rate | >70-80% | Low rates can indicate contamination or poor-quality reference alignment. [1] |

| rRNA Reads | <4-10% | High percentages indicate inefficient rRNA depletion, wasting sequencing depth. [1] | |

| Duplicate Reads | As low as possible | High rates can indicate low input material or PCR over-amplification artifacts. [2] | |

| Strand Specificity | ~50%/50% (non-strand) or ~99%/1% (strand-specific) | Validates the performance of strand-specific library protocols. [3] | |

| Gene Coverage | Number of Genes Detected | Study-dependent | Indicates library complexity; lower numbers can suggest degradation or low input. [1] |

| 3'/5' Bias | ~1 (uniform coverage) | Deviation can indicate RNA degradation, as the 5' end degrades first. [3] [4] | |

| Base-Level Quality | Q-score (Q30) | >80% of bases ≥ Q30 | Measures sequencing accuracy; low Q-scores increase false variant calls. [5] |

| Expression Profile Correlation | High correlation with reference | Low correlation with expected expression profiles can indicate technical issues. [3] |

Q2: My data has a high duplication rate. Is this a problem, and what caused it?

A: Yes, a high duplication rate is a significant concern. While some duplicates represent highly expressed genes, a high rate often indicates technical artifacts that reduce library complexity and can bias expression quantification. [1]

The primary cause is the combination of low input RNA and excessive PCR amplification cycles during library preparation. A 2025 study systematically demonstrated that for input amounts below 125 ng, the proportion of PCR duplicates increases dramatically, in some cases leading to the discard of 34-96% of reads after deduplication. This artifact was consistently observed across multiple sequencing platforms (Illumina NovaSeq 6000, NovaSeq X, Element AVITI, and Singular Genomics G4). [2]

Table 2: Impact of Input RNA and PCR Cycles on Duplication Rates

| Input RNA Amount | PCR Cycles | Impact on Duplicate Rate & Data Quality |

|---|---|---|

| High (>250 ng) | Standard | Low duplicate rate; data quality plateaus. |

| Low (<125 ng) | High | Dramatically increased duplicate rate; fewer genes detected; increased noise in expression counts. [2] |

| Low (<125 ng) | Low (Recommended) | Significantly lower duplicate rate; higher quality sequencing data preserved. |

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Verify Input Quantity: Use a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit) to accurately quantify RNA before library prep.

- Minimize PCR Cycles: Use the lowest number of PCR cycles recommended for your library prep kit, especially for low-input samples.

- Use UMIs: Employ Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) in your library protocol. UMIs allow for precise bioinformatic identification and removal of PCR duplicates, preserving true biological signals. [2]

Q3: How does RNA degradation impact my gene expression results, and can I use partially degraded samples?

A: RNA degradation has a profound and non-uniform impact on transcript quantification. It is not a simple, uniform loss of signal. Different transcripts degrade at different rates, which can systematically bias your expression measurements. [4]

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) often shows that the largest source of variation (e.g., 28.9% in one study) is driven by the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) rather than biological differences. This means samples may cluster by quality rather than by experimental group, severely confounding results. [4]

Protocol for Assessing and Correcting for Degradation:

- Measure Degradation: Calculate the RIN or similar integrity score (e.g., with TapeStation or Bioanalyzer) for all samples.

- Visualize 3'/5' Bias: Use tools like RNA-SeQC to check for coverage bias along transcript bodies. Degraded samples will show a clear drop in coverage at the 5' end. [3] [4]

- Statistical Correction: If RIN is not confounded with your experimental groups, you can use a linear model framework to explicitly control for the RIN effect during differential expression analysis, potentially recovering a biological signal. [4]

- Set a Threshold: As a best practice, set a pre-defined RIN cutoff for your study (a common threshold is RIN > 7) and exclude samples below it to prevent introducing bias.

Q4: What is "quality imbalance," and why is it a "silent threat" to my analysis?

A: Quality imbalance (QI) occurs when the overall quality of RNA-seq samples is systematically different between the groups you are comparing (e.g., disease vs. control). This is a silent threat because it can create false positives that look like strong biological signals but are actually artifacts of data quality. [6] [7]

A 2024 analysis of 40 clinical RNA-seq datasets found that 35% had significant quality imbalances. The study showed that the higher the QI, the greater the number of falsely identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs). In highly imbalanced datasets, the number of DEGs increased four times faster with dataset size compared to balanced datasets. Furthermore, up to 22% of the top "differential" genes in these studies were actually quality markers associated with sample stress. [6]

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Calculate a QI Index: Use tools like

seqQscorerto automatically assign a quality probability to each sample and calculate an imbalance index between groups. An index near 1 indicates severe confounding. [6] [7] - Check for Quality Markers: Be skeptical if your top DEGs are enriched for known stress-response genes.

- Remove Outliers: If a quality imbalance is detected, consider removing the most severe low-quality outliers from the analysis. The same 2024 study demonstrated that this practice improves the relevance of the resulting DEG list. [6]

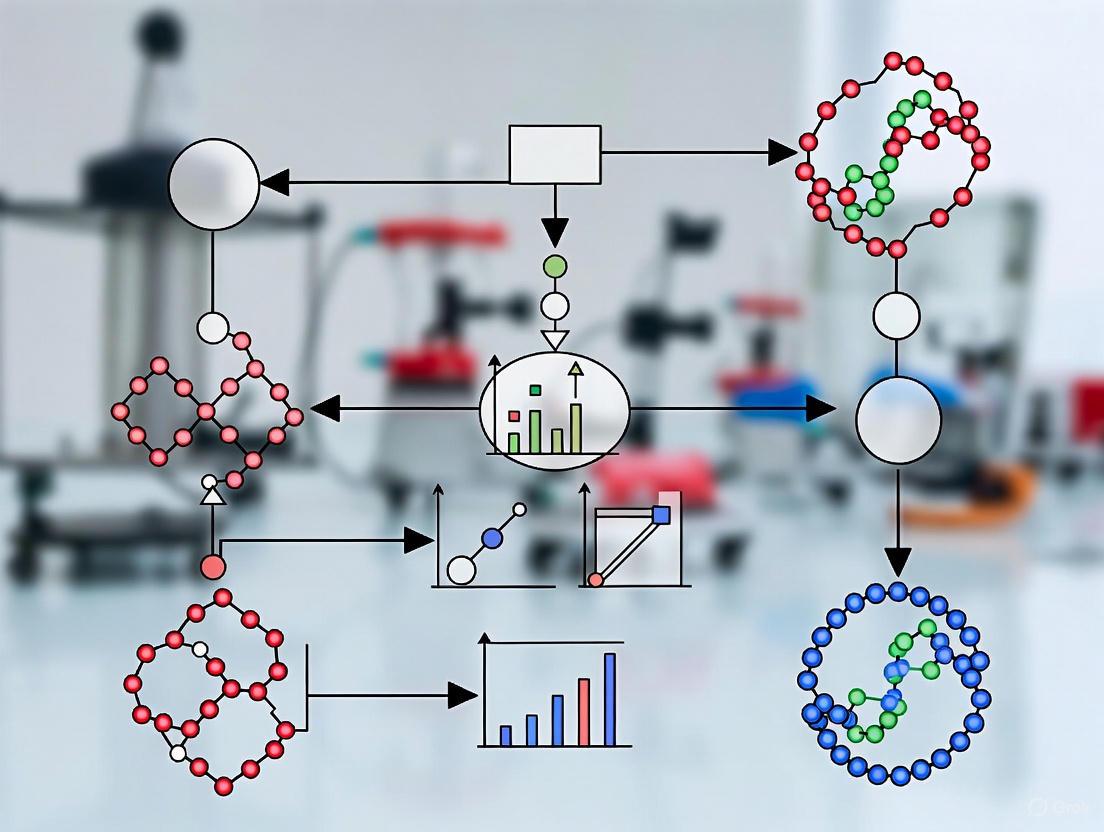

Diagram: The Impact and Solution for Quality Imbalance.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for RNA-Seq Quality Control

| Tool or Reagent | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control Software | Provides a suite of metrics for data assessment and process optimization. | RNA-SeQC [3], RSeQC [8] |

| Machine Learning Quality Scorer | Automatically detects poor-quality samples and quantifies quality imbalance between groups. | seqQscorer [6] [7] |

| Raw Read Quality Assessor | Initial quality check of FASTQ files for base quality, adapter contamination, etc. | FastQC [8], MultiQC [8] |

| Library Prep with UMIs | Enables precise bioinformatic removal of PCR duplicates, crucial for low-input RNA. | UMI-based Kits [2] |

| RNA Integrity Assessor | Measures sample degradation before sequencing. | Bioanalyzer, TapeStation (for RIN) [4] |

Why does my RNA-seq workflow fail between FASTQ and count matrix generation?

Errors in this stage often arise from poor initial data quality, misalignment, or incorrect handling of multi-mapped reads. One study found that 35% of clinically relevant RNA-seq datasets had significant hidden quality imbalances between sample groups, which can drastically inflate false positives in differential expression analysis [7]. Furthermore, for hundreds of genes, particularly those in gene families, standard quantification methods systematically underestimate expression, which can distort biological interpretations [9].

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Analysis

| Item Name | Function |

|---|---|

| FastQC | Generates a detailed quality report for raw sequencing data in FASTQ format, highlighting issues like low-quality bases and adapter contamination [10]. |

| RNA-QC-Chain | A comprehensive pipeline performing sequencing-quality assessment, trimming, ribosomal RNA filtering, and alignment statistics reporting [11]. |

| STAR | A popular spliced aligner for mapping RNA-seq reads to a reference genome [9]. |

| Salmon | A fast, alignment-free tool for transcript quantification that uses unique kmers, bypassing the alignment step [9] [12]. |

| featureCounts | A tool to assign aligned reads to genomic features (like genes) to generate a count matrix [13]. |

| DESeq2 | A widely used R package for differential expression analysis of count data. |

| MultiQC | Aggregates results from multiple tools (like FastQC, STAR, featureCounts) into a single, consolidated report [10]. |

| seqQscorer | A machine learning-based tool that automatically detects quality imbalances in sequencing data [7]. |

Detailed Methodologies and Data

Table: Quantitative Impact of Bioinformatics Tools on Gene Detection (from Robert et al. 2015)

| Method (Aligner + Quantification) | Pearson Correlation (vs. Expected FPKM) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sailfish | 0.95 | Alignment-free quantification [9]. |

| TopHat2 + Cufflinks | 0.95 | Relies on spliced alignment [9]. |

| STAR + Cufflinks | 0.95 | Relies on spliced alignment [9]. |

| STAR + HTSeq (union) | 0.78 | Higher false negative rate for genes with multi-mapped reads [9]. |

| Sailfish (bias-corrected) | 0.08 | Highlights potential issues with bias correction models on certain data [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Two-Stage Analysis for Ambiguous Reads To recover biological signal from data that would otherwise be discarded, consider this protocol:

- Standard Quantification: Process your RNA-seq data through your standard alignment (e.g., STAR) and quantification (e.g., featureCounts) pipeline.

- Group-Level Assignment: Re-process the multi-mapped or ambiguous reads that are typically discarded or randomly assigned. Instead, assign them uniquely to groups of genes (e.g., gene families) that share high sequence similarity.

- Integrated Analysis: Use this group-level expression data to supplement the standard gene-level counts, which can reveal relevant biological signals otherwise missed [9].

Workflow Visualization

This troubleshooting workflow maps logical steps for diagnosing failures in your RNA-seq pipeline.

Key Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: My workflow runs but my final count matrix has many genes with zero counts. What's wrong?

This is a classic symptom of bioinformatics quantification bias. Hundreds of genes, especially those in gene families, can be underestimated. Check if the affected genes have paralogs. Try an alignment-free quantifier like Salmon or use the --multi-read-correct option in Cufflinks to improve counts for these genes [9].

Q2: Why does my workflow fail when processing multiple samples with featureCounts? In workflow management systems like Galaxy, connecting multiple featureCounts outputs directly to the same DESeq2 factor level can cause the workflow to hang. The solution is to ensure each featureCounts output is sent to a distinct factor level in DESeq2, or to organize the data into a single count matrix and a separate sample information file for input into DESeq2 [13].

Q3: My raw data looks good, but my results are biologically implausible. What hidden issues should I check for? Your data may suffer from hidden quality imbalances between sample groups (e.g., cases vs. controls). This is a silent threat that can cause false positives. Use tools like seqQscorer to automatically detect these imbalances. Also, check for batch effects and ensure all samples have comparable alignment statistics (e.g., mapping rates, ribosomal RNA content) [7] [11].

Robust quality control (QC) is the foundation of reliable RNA-seq analysis. Tools like FastQC, MultiQC, and Qualimap help researchers identify issues that can compromise data integrity, from raw sequencing reads to aligned data. Proper interpretation of their reports is crucial, as "Warn" or "Fail" flags do not always mean the data is unusable, but rather that the results must be critically evaluated within the biological context of your experiment [14]. This guide provides troubleshooting advice and FAQs to help you diagnose and resolve common quality issues.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. A FastQC module shows "FAIL." Does this mean my data is unusable? Not necessarily. FastQC's thresholds are tuned for whole genome shotgun DNA sequencing and can be overly strict for RNA-seq data. It is normal and expected for RNA-seq data to "FAIL" certain modules, such as Per base sequence content (due to non-uniform base composition at transcript starts) and Sequence Duplication Levels (due to highly abundant transcripts) [14]. The key is to understand the underlying biology of your sample.

2. MultiQC isn't finding all my samples. What should I do? This is often caused by clashing sample names. MultiQC overwrites previous results if it finds identical sample names. To troubleshoot:

- Run MultiQC with the

-v(verbose) flag to see warnings about name clashes. - Use the

-dor--dirsflag to prepend the directory name to the sample name, preserving the source [15] [16]. - Use the

-sor--fullnamesflag to disable all sample name cleaning and use the full file name [16].

3. Why does my Qualimap report fail to appear in MultiQC?

MultiQC is designed to parse the raw data output from QualiMap BamQC, not the general "statistics" output from QualiMap RNA-Seq QC [17]. Ensure you are running the correct QualiMap module and providing the counts output, or use the QualiMap Counts QC tool to generate a compatible summary [17].

4. What are the key metrics to check for RNA-seq QC? When reviewing a MultiQC report, prioritize these metrics [18]:

- Total Reads: The raw sequencing depth for each sample.

- Percentage of Reads Aligned: A good sample should have at least 75% of reads uniquely mapped to the genome. Values below 60% warrant investigation [18].

- Percentage of Reads Associated with Genes: In a good library for well-annotated organisms like human or mouse, expect over 60% of reads to map to exons. High levels of intergenic reads (>30%) may indicate DNA contamination [18].

- 5'-3' Bias: This metric should be close to 1. Values approaching 0.5 or 2 can indicate RNA degradation or sample preparation issues [18].

5. How can hidden quality imbalances affect my analysis? Quality imbalances between sample groups (e.g., diseased vs. healthy) can be a silent threat, artificially inflating the number of differentially expressed genes and leading to false conclusions [7]. It is crucial to check that QC metrics are consistent across all samples in an experiment and to investigate any outliers [18] [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting FastQC Reports

Understanding the cause of a FastQC warning is the first step toward a solution. The following table outlines common issues and their interpretations.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common FastQC Anomalies in RNA-seq Data

| FastQC Module | Common "Fail" Cause | Is This a Problem? | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per base sequence content | Non-random base composition at the start of reads due to hexamer priming in RNA-seq libraries [14]. | Usually No. Expected for RNA-seq. | Typically ignore if the bias is in the first 10-15 bases and the library is RNA-seq. |

| Per sequence GC content | The distribution of GC content across reads is non-normal for your sample type [14]. | Context-dependent. Expected for RNA-seq due to varying transcript GC content [14]. | Compare the shape of the distribution across samples. If consistent, it is likely biological. |

| Sequence duplication levels | Presence of highly abundant natural transcripts (e.g., actin, hemoglobin) [14]. | Usually No. This is a true biological signal in RNA-seq. | Ignore if the data is RNA-seq. For other assays, it may indicate low library complexity. |

| Adapter Content | Detection of adapter sequence at the 3' end of reads, indicating short library fragments [14]. | Yes, if excessive. Can interfere with alignment. | Quantify the percentage. If significant (>1%), use a trimmer like Trim Galore! or cutadapt [19]. |

| Kmer Content | Overrepresented short sequences at specific positions [14]. | Context-dependent. Can indicate contamination or biological signals. | Check the list of overrepresented kmers against a contaminant database. |

Troubleshooting MultiQC Execution

Table 2: Solving Common MultiQC Operational Problems

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "No analysis results found." | Log files are too large, concatenated, or not in the expected format [15]. | 1. Check the tool is supported and ran correctly [15].2. Increase the file size limit with log_filesize_limit in your config [15].3. Increase the number of lines searched with filesearch_lines_limit [15]. |

| "No space left on device" Error | The temporary directory has insufficient space for processing [15]. | Set the TMPDIR environment variable to a path with more free space: export TMPDIR=/path/to/larger/disk [15]. |

| "Click will abort further execution" Error | The system locale is not properly configured [15]. | Add these lines to your ~/.bashrc or ~/.zshrc file: export LC_ALL=en_US.UTF-8 and export LANG=en_US.UTF-8 [15]. |

Troubleshooting Qualimap Integration

The most common issue is generating the wrong type of output from Qualimap. The workflow below outlines the correct process for generating a MultiQC report from Qualimap RNA-seq data and highlights the critical step for success.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Tools for RNA-seq Quality Control and Troubleshooting

| Tool Name | Function | Role in QC |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Quality control tool for raw sequencing data [14]. | Provides initial assessment of read quality, base composition, adapter contamination, and more [14]. |

| MultiQC | Aggregation and visualization tool [18]. | Parses output from FastQC, STAR, Qualimap, Salmon, and others to create a single, interactive QC report for cross-sample comparison [18]. |

| Qualimap | Alignment-level quality control tool [18]. | Evaluates RNA-seq-specific metrics from BAM files, such as 5'-3' bias, genomic feature coverage, and inside-outside profile [18]. |

| Trim Galore! | Wrapper for Cutadapt and FastQC [19]. | Automates adapter and quality trimming of reads based on FastQC results, producing cleaner FASTQ files for alignment [19]. |

| Salmon | Rapid transcript quantification tool [19]. | Provides mapping statistics and is a primary source for transcript abundance estimates used in differential expression analysis [18]. |

| seqQscorer | Machine learning-based quality scorer [7]. | Uses classification algorithms to automatically detect and statistically characterize quality issues in NGS data, helping to identify hidden quality imbalances [7]. |

Standard Operating Procedure: Comprehensive RNA-seq QC

This protocol describes a standard workflow for generating and interpreting a comprehensive QC report for a bulk RNA-seq experiment using FastQC, STAR, Qualimap, Salmon, and MultiQC [18] [19].

1. Generate Raw Read QC with FastQC

- Input: Raw FASTQ files.

- Process: Run FastQC on all your sequencing files. This can be done in parallel for efficiency.

- Command Example:

fastqc *.fastq.gz - Output: One

_fastqc.htmlfile and one_fastqc.zipfile per FASTQ [19].

2. Perform Read Alignment and Quantification

- Tool Options: Use a splice-aware aligner like STAR [19] or a pseudo-aligner like Salmon [19]. This example uses the common STAR -> Salmon route.

- STAR Command (Simplified):

STAR --genomeDir /path/to/index --readFilesIn sample_1.fastq.gz --runThreadN 8 --outSAMtype BAM Unsorted --quantMode TranscriptomeSAM --outFileNamePrefix sample_1.This produces a transcriptome BAM file for Salmon. - Salmon Quantification: Use the transcriptome BAM from STAR or raw FASTQs to quantify transcript abundances with Salmon [19].

3. Generate Alignment QC with Qualimap

- Input: The genomic BAM file from STAR (not the transcriptome BAM).

- Process: Run Qualimap's RNA-seq QC mode.

- Command Example (Simplified):

qualimap rnaseq -bam sample_1.Aligned.out.bam -gtf annotation.gtf -outdir qualimap_sample_1 - Critical Step: Ensure you collect the "counts" output, as this is what MultiQC requires [17].

4. Aggregate All Reports with MultiQC

- Input: All output directories and files from FastQC, STAR logs, Qualimap counts outputs, and Salmon directories.

- Process: Run MultiQC in the directory containing all these results.

- Command Example:

multiqc -n multiqc_report . - Output: A single

multiqc_report.htmlfile and amultiqc_datadirectory with the underlying data [18].

5. Interpret the MultiQC Report

- Check the General Statistics table for key metrics like total reads, % alignment, and % duplicates [18].

- Examine the STAR: Alignment Scores plot to ensure high, consistent unique mapping rates across samples (aim for >75%) [18].

- In the Qualimap section, check the 5'-3' bias value is close to 1 and the Transcript Position plot shows even coverage [18].

- Verify that the percentage of exonic reads is high (>60%) and intergenic reads are low, indicating minimal DNA contamination [18].

In RNA-seq and PCR-based experiments, technical artifacts can compromise data integrity and lead to erroneous biological conclusions. This guide addresses three common issues—primer dimers, adapter contamination, and high rRNA content—by explaining their causes, implications, and solutions. Recognizing and troubleshooting these artifacts is crucial for ensuring the accuracy and reproducibility of your research.

Primer Dimers

What are primer dimers and what do they reveal about my reaction?

Primer dimers are short, unintended DNA fragments that form when PCR primers anneal to each other instead of the target template. They typically appear as a fuzzy smear or band below 100 bp on an agarose gel [20].

What they reveal: The presence of primer dimers indicates suboptimal reaction conditions. This is often due to factors like inefficient primer design, excessive primer concentration, low annealing temperatures, or polymerase activity at room temperature during reaction setup [20] [21]. In RNA-seq library prep, primer dimers can consume reagents and sequencer capacity, leading to reduced library complexity and lower coverage of your intended targets [22].

How can I troubleshoot and prevent primer dimers?

Prevention through Primer Design and Reaction Setup:

- Design Primers Meticulously: Use trusted software (e.g., Primer3) to create primers with low self-complementarity and 3'-end complementarity. Ensure the annealing temperatures for both primers are within 3°C of each other [21].

- Optimize Reaction Conditions: Lower primer concentrations (typically 10 pM or less), increase annealing temperatures, and use a hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent activity during setup [20] [21].

- Refine Laboratory Practice: Prepare reactions on ice, add polymerase last, and immediately transfer tubes to a pre-heated thermocycler to minimize off-target annealing [21].

Corrective Actions:

- If primer dimers are observed, run a no-template control (NTC). Bands in the NTC confirm primer dimer formation independent of your sample [20].

- Re-optimize the PCR using a temperature gradient to find the optimal annealing stringency [21].

Adapter Contamination

What is adapter contamination and why is it a problem?

Adapter contamination occurs when sequencing adapters are not properly ligated to target fragments or are not adequately removed during library cleanup. This results in reads derived primarily from adapters rather than biological sample [23].

What it reveals: A high level of adapter contamination signals inefficiencies during library construction. This can stem from an incorrect adapter-to-insert molar ratio, inefficient ligation, or failures during the purification and size selection steps meant to remove small fragments [22] [23]. It wastes sequencing cycles on non-informative data, drastically reducing the useful data yield from a sequencing run.

How can I identify and fix adapter contamination?

Identification:

- Quality Control Tools: Tools like FastQC will flag overrepresented sequences, often identifying adapter sequences directly in your raw FASTQ files [24] [25] [26].

- Electropherogram Peaks: Sharp peaks around 70-90 bp on a Bioanalyzer or TapeStation trace are a classic signature of adapter dimers [23].

Prevention and Solutions:

- Optimize Ligation: Titrate the adapter-to-insert ratio to find the optimal balance that maximizes ligation efficiency while minimizing adapter dimer formation [23].

- Thorough Cleanup: Use bead-based cleanup with the correct sample-to-bead ratio to effectively remove short adapter artifacts. Consider a double-sided size selection to exclude both large and small unwanted fragments [23].

- Bioinformatic Trimming: Use tools like Cutadapt or Trimmomatic to trim remaining adapter sequences from reads after sequencing [24] [26].

High rRNA Content

Why is my rRNA content high and how does it impact my RNA-seq data?

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) constitutes over 90% of total RNA in a cell. In RNA-seq, high rRNA content means that a large proportion of your sequencing reads are spent on rRNA instead of informative mRNA or other RNAs of interest [24].

What it reveals: High rRNA reads indicate that the step to remove or deplete rRNA during library preparation was inefficient. This can be due to degraded RNA starting material (which compromises poly(A) selection), using the wrong depletion protocol for the sample type (e.g., using poly(A) selection for bacterial RNA), or using a suboptimal rRNA depletion kit [22] [24]. The primary impact is a severe reduction in sequencing depth for your target transcriptome, lowering the power to detect differentially expressed genes, especially those with low expression [25].

How can I reduce rRNA in my libraries?

Strategy Selection:

- Poly(A) Selection: This is effective for enriching eukaryotic mRNA from high-quality, intact RNA but is unsuitable for prokaryotic samples or degraded RNA (e.g., from FFPE tissues) [24].

- Ribosomal Depletion: Uses probes to hybridize and remove rRNA. This is the only option for prokaryotic RNA and is preferred for degraded eukaryotic samples or when studying non-coding RNAs [22] [24].

Troubleshooting:

- Assess RNA Quality: Always check RNA Integrity (RIN) before library prep. Degraded RNA is a major cause of poly(A) selection failure [22].

- Optimize Depletion: For difficult samples (e.g., low input or highly degraded), consider increasing the input RNA amount or using depletion kits specifically validated for your sample type [22].

Table 1: Summary of Common RNA-Seq Artifacts, Their Causes, and Identification Methods

| Artifact | Primary Causes | How to Identify | Impact on Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer Dimers [20] [21] | Primer complementarity, low annealing temperature, high primer concentration, polymerase activity during setup. | Fuzzy band/smear <100 bp on gel; presence in No-Template Control (NTC). | Reduced amplification efficiency; lower library yield; false positives in qPCR. |

| Adapter Contamination [22] [23] | Improper adapter-to-insert ratio, inefficient ligation, failed cleanup/size selection. | FastQC "Overrepresented Sequences"; sharp ~70-90 bp peak on Bioanalyzer. | Wasted sequencing reads; reduced useful data yield and coverage. |

| High rRNA Content [22] [24] | Failed rRNA depletion, use of poly(A) selection on degraded or prokaryotic RNA. | >30% of reads align to rRNA; low exon mapping rate in QC tools (e.g., RSeQC). | Drastically reduced coverage of mRNA; lower power for differential expression. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Troubleshooting

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase [20] [21] | Inhibits polymerase activity at low temperatures. | Prevents primer dimer formation during PCR reaction setup. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | A pure, uncontaminated reaction solvent. | Ensures reactions are not compromised by RNases, DNases, or other contaminants. |

| Barcoded/Indexed Adapters [27] | Unique oligonucleotide sequences ligated to samples. | Enables multiplexing and detection of cross-contamination or batch effects. |

| Strand-Specific Library Kits [24] | Preserves the original strand information of RNA. | Improves accuracy of transcript assembly and quantification. |

| RNase H-based Depletion Kits [22] | Enzymatically degrades rRNA. | An alternative to probe-based depletion for reducing rRNA in RNA-seq libraries. |

| Magnetic Beads (SPRI) [23] | Solid-phase reversible immobilization for size selection and cleanup. | Critical for removing adapter dimers and selecting the correct insert size. |

Experimental Workflow for RNA-Seq Quality Control

The following diagram outlines a standard RNA-seq workflow with integrated quality checkpoints to identify and prevent common artifacts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can I ignore primer dimers if my target band looks strong? While a strong target band is good, primer dimers should not be ignored. They consume reaction reagents and can reduce the efficiency and yield of your target amplification, especially in later PCR cycles or in qPCR where they can lead to false-positive fluorescence signals [20] [21].

Q2: My RNA is from FFPE tissue. How can I avoid high rRNA content? Poly(A) selection is often ineffective for degraded FFPE RNA. You should use rRNA depletion protocols. Furthermore, using random hexamer primers for reverse transcription (instead of oligo-dT) can help generate more uniform libraries from fragmented RNA [22].

Q3: I see a high duplication rate in my RNA-seq data. Is this related to these artifacts? Yes, high duplication can have several causes related to artifacts. Adapter contamination and primer dimers can produce many identical reads. Alternatively, high duplication can stem from low input RNA leading to over-amplification during PCR, or from an insufficiently complex library where a few highly expressed transcripts dominate [24] [23].

Q4: Are there specific kit recommendations to avoid these problems? For RNA-seq, select kits based on your sample type. For low-input or degraded samples, choose kits with robust rRNA depletion and protocols designed for low inputs to minimize over-amplification bias. Always use hot-start polymerase kits for PCR. For library prep, kits that incorporate dual-index unique barcodes help identify and prevent cross-contamination [22] [21] [23].

The Critical Link Between Experimental Design and Data Quality

This guide addresses the critical connection between robust experimental design and high-quality RNA-seq data. Proper planning is your first and most powerful defense against data quality issues that can compromise your entire study. Here, you will find targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help you identify, resolve, and prevent common problems in your RNA-seq workflow.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High Variation in Gene Expression Data

Problem: High unexplained variation in your data makes it difficult to detect truly differentially expressed genes.

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Check the number of biological replicates. Fewer than three replicates per condition greatly reduces the power to detect real differences and estimate variability reliably [28] [29].

- Examine your Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot. Do samples from the same experimental group cluster together? If not, a hidden batch effect may be present [25].

- Review the raw data quality control (QC) reports for all samples. Are there significant quality imbalances between your experimental groups (e.g., between treated and control samples)? Such imbalances can inflate false positives [7].

Solutions:

- Increase Replication: Always include an adequate number of biological replicates. While three is often a minimum, more may be needed for systems with high inherent variability [28] [29].

- Randomize and Block: During library preparation and sequencing, randomize samples across technical batches (like sequencing lanes) to avoid confounding batch effects with your conditions of interest. Use a blocking design if full randomization isn't possible [29].

- Check for Quality Imbalances: Use tools like

seqQscorerto automatically detect systematic quality differences between groups. Address the root cause, which may lie in sample handling or RNA extraction [7].

Guide 2: Managing PCR Duplicates and Artifacts

Problem: A high rate of PCR duplicates can lead to inaccurate quantification of transcript abundance, especially for lowly expressed genes.

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Check the post-alignment duplication rate from tools like Picard or Qualimap [24] [25].

- Note the amount of input RNA and the number of PCR cycles used during library preparation. Lower input amounts and higher PCR cycle numbers are strongly correlated with increased duplicate rates [2].

Solutions:

- Optimize Input RNA: Use the highest input amount your experiment allows, ideally above 125 ng, to maximize library complexity [2].

- Minimize PCR Cycles: Use the lowest number of PCR cycles necessary for successful library amplification [2].

- Use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Incorporate UMIs into your library prep protocol. UMIs allow for precise identification and removal of PCR-derived duplicates, ensuring that read counts reflect original molecule counts [2].

Guide 3: Resolving Poor Read Mapping and Coverage

Problem: A low percentage of your sequencing reads align to the reference genome or transcriptome, or read coverage across transcripts is uneven.

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Review the raw read QC. Look for high levels of adapter contamination or a dramatic drop in base quality scores towards the ends of reads [28] [25].

- Check the post-alignment QC. A mapping rate below 70-90% is a strong indicator of problems [25]. Also, look for high levels of reads mapping to multiple locations or unusual biases in the

gene body coverageplot [24]. - Verify the RNA extraction and library prep method. Was poly(A) selection or rRNA depletion used? Degraded RNA or an inappropriate selection method can lead to biased representation [24].

Solutions:

- Trim Adapters and Low-Quality Bases: Use tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to clean raw reads before alignment [28] [24].

- Choose the Right Library Kit: For samples with lower RNA integrity (e.g., from FFPE tissues), use ribosomal depletion instead of poly(A) selection to capture a more representative transcriptome [24].

- Select an Appropriate Aligner: Use splice-aware alignment software such as STAR or HISAT2 for eukaryotic transcriptomes to accurately map reads across splice junctions [28] [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most important factor in my experimental design for a successful RNA-seq study? The inclusion of a sufficient number of biological replicates is paramount. Biological replicates, which capture the natural variation in your system, are essential for statistically robust differential expression analysis. Without them, you cannot reliably distinguish biological signal from noise [28] [29] [30].

Q2: My data has a batch effect. Can I fix it bioinformatically?

While batch effect correction tools (e.g., in R packages like sva or limma) can help, they are not a substitute for good experimental design. The most effective strategy is to prevent batch effects by randomizing samples during library prep and sequencing. If a batch effect is present, it can sometimes be corrected post-hoc, but this requires careful statistical handling and should be clearly reported [29] [25].

Q3: How deep should I sequence my RNA-seq libraries? There is no universal answer, as it depends on your goals. For standard differential expression analysis in a well-annotated eukaryote, 20-30 million reads per sample is often sufficient. If you are studying lowly expressed transcripts or doing alternative splicing analysis, you may need significantly deeper sequencing (e.g., 50-100 million reads) [24].

Q4: Should I use single-end or paired-end sequencing? Paired-end (PE) sequencing is generally preferable. It provides more unique and confident mapping of reads, which is especially beneficial for detecting alternative splicing events, novel transcripts, and gene fusions. Single-end (SE) sequencing can be sufficient for basic gene-level quantification in well-annotated genomes and is less expensive [24].

Essential Data and Protocols

Table 1: Key Normalization Methods for RNA-seq Count Data

| Method | Corrects for Sequencing Depth? | Corrects for Gene Length? | Corrects for Library Composition? | Suitable for Differential Expression? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM | Yes | No | No | No | Simple scaling; heavily influenced by highly expressed genes [28] |

| RPKM/FPKM | Yes | Yes | No | No | Allows sample-to-sample comparison for a single gene; not for cross-gene comparison [28] |

| TPM | Yes | Yes | Partial | No | Improves on RPKM/FPKM; better for sample-to-sample comparison of individual genes [28] |

| Median-of-Ratios (DESeq2) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Robust method used by DESeq2; good for DE analysis [28] |

| TMM (edgeR) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Robust method used by edgeR; good for DE analysis [28] |

Table 2: Recommended Sequencing Specifications for Common Goals

| Experimental Goal | Recommended Replicates | Recommended Sequencing Depth | Read Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Gene Expression | Minimum 3, more if high variability [28] [29] | 20-30 million reads/sample [24] | SE or PE |

| Alternative Splicing Analysis | Minimum 3, more if high variability | 50-100 million reads/sample [24] | PE |

| Novel Transcript Discovery | Minimum 3, more if high variability | 50-100 million reads/sample [24] | PE |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq | Multiple cells per condition (e.g., 100s) | 50,000 - 1 million reads/cell [24] | SE or PE |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard RNA-seq Workflow

- Experimental Design & Replication: Define your biological question and determine the appropriate number of biological replicates. Randomize the processing order of samples.

- RNA Extraction & QC: Isolate total RNA and assess its quality and integrity using methods like Bioanalyzer (RIN score) [24].

- Library Preparation:

- rRNA Depletion or poly(A) Selection: Choose based on RNA quality and organism (rRNA depletion is required for bacteria and is better for degraded samples) [24].

- cDNA Synthesis: Convert RNA to cDNA. For strand-specific information, use a protocol like dUTP marking [24].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the library using the minimum number of cycles needed, especially with low input RNA [2].

- Sequencing: Sequence the libraries on an Illumina or other NGS platform to the desired depth and read length.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Use

FastQC/MultiQCon raw FASTQ files [28] [25]. - Read Trimming: Use

TrimmomaticorCutadaptto remove adapters and low-quality bases [28] [24]. - Read Alignment: Map reads to a reference genome/transcriptome using a splice-aware aligner like

STARorHISAT2[28]. - Post-Alignment QC: Use

QualimaporRSeQCto assess mapping statistics and coverage [24] [25]. - Quantification: Generate a count matrix per gene using

featureCountsorHTSeq-count[28]. - Differential Expression: Analyze the count data using specialized tools like

DESeq2oredgeR[28].

- Quality Control: Use

Visual Workflows

RNA-seq Experimental and Analysis Workflow

Quality Control Checkpoints Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA, enriching for other RNA types (mRNA, lncRNA). | Essential for prokaryotic RNA-seq or eukaryotic samples with degraded RNA (e.g., from FFPE) [24]. |

| poly(A) Selection Kits | Enriches for messenger RNA by capturing the poly-adenylated tail. | Requires high-quality, intact RNA. May introduce 3' bias in coverage if RNA is degraded [24]. |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kits | Preserves the information about which DNA strand was transcribed. | Crucial for identifying antisense transcription and accurately quantifying overlapping genes [24]. |

| UMI Adapters | Adds unique random barcodes to each original RNA molecule before PCR amplification. | Enables precise removal of PCR duplicates, improving quantification accuracy, especially for low-input samples [2]. |

| Low-Input Library Prep Kits | Optimized protocols for generating libraries from very small amounts of starting RNA. | Includes modifications to maximize efficiency and minimize losses, often requiring higher PCR cycles which must be optimized [2]. |

Building a Robust RNA-seq QC and Preprocessing Pipeline

In RNA-seq analysis, ensuring data quality is not a mere formality but a critical, non-negotiable step that underpins all subsequent biological interpretations [25]. Raw sequencing data invariable contains artifacts such as adapter sequences, low-quality bases, and overrepresented sequences, which can lead to incorrect differential expression results, low reproducibility, and wasted resources [31]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of four essential tools—FastQC, Trimmomatic, fastp, and Cutadapt—to help you build a robust preprocessing workflow, complete with troubleshooting advice for common pitfalls.

Tool Comparison Table

The following table summarizes the core features, primary strengths, and ideal use cases for each tool to help you make an informed selection.

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Features | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Quality Control | Provides an HTML report with graphs on per-base quality, adapter content, GC content, etc. [32]. | Initial assessment of raw FASTQ files for any sequencing project [25]. | A diagnostic tool only; cannot modify data. |

| Trimmomatic | Read Trimming | Versatile; handles adapter removal (ILLUMINACLIP), sliding window quality trimming, and minimum length filtering [33]. | RNA-seq, WGS, and exome sequencing where flexible, parameter-controlled trimming is needed [31]. | Can be slower than modern alternatives; requires manual creation of custom adapter files for non-standard contaminants [34]. |

| fastp | All-in-one Trimming & QC | Ultra-fast; performs adapter trimming, quality filtering, polyX trimming, and generates a QC report in one step [35]. | Large datasets requiring rapid preprocessing and integrated pre- and post-filtering QC reports [31]. | Less user-customization for complex, non-standard trimming scenarios [31]. |

| Cutadapt | Precise Adapter Trimming | Expert at finding and removing adapter sequences from the ends of reads with high precision [36]. | Small RNA-seq, amplicon sequencing (16S, ITS), and datasets with persistent, known adapter contamination [31]. | Primarily focused on adapter removal; less comprehensive for other trimming types unless combined with other tools [31]. |

Experimental Workflow and Protocol Integration

A standard RNA-seq quality control and preprocessing workflow integrates these tools sequentially. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and data flow between the key steps.

Detailed Preprocessing Protocol

Initial Quality Assessment:

Read Trimming and Filtering:

Select one of the following tools based on your needs:

Option A: Trimmomatic (For controlled, multi-step trimming)

- Command Example (Single-end):

- Parameters:

ILLUMINACLIPremoves adapters,SLIDINGWINDOWtrims low-quality bases, andMINLENdiscards short reads [33].

Option B: fastp (For speed and an all-in-one solution)

- Command Example (Paired-end):

- Parameters:

--detect_adapter_for_peallows automatic adapter detection, and--trim_poly_gis crucial for data from NovaSeq/NextSeq platforms [35].

Option C: Cutadapt (For precise adapter removal)

- Command Example:

- Parameters: Provide the exact adapter sequences for your library prep kit with the

-aand-Aflags [36].

Post-Trimming Quality Assessment:

- Tool: FastQC + MultiQC [32].

- Action: Run FastQC again on the trimmed FASTQ files. Then, use MultiQC to aggregate all reports (from both raw and trimmed data) into a single, easy-to-compare HTML report.

- Command Example:

multiqc . --filename multiqc_report.html

FAQ and Troubleshooting Guide

Why are my adapters still present after running Trimmomatic or Cutadapt?

- Cause: The adapter sequence provided in the command does not perfectly match the one in your data. This can happen with custom library prep kits or if the adapter is located in the middle of the read, requiring a different clipping approach [36] [37].

- Solution:

- Verify Adapter Sequence: Double-check the adapter sequences used in your library preparation kit. Use

grepor look at the "Overrepresented sequences" section in FastQC to find the exact sequence. - Use a Custom Fasta File: For Trimmomatic, create a custom FASTA file containing your specific adapter sequences and reference it in the

ILLUMINACLIPparameter [34]. - Adjust Sensitivity: Lower the seed mismatches (

:2inILLUMINACLIP:adapter.fa:2:30:10) or the accuracy threshold in Cutadapt to allow for more flexible matching.

- Verify Adapter Sequence: Double-check the adapter sequences used in your library preparation kit. Use

Should I remove overrepresented sequences that are not adapters, like rRNA?

- Short Answer: Generally, no, especially for de novo assembly.

- Detailed Explanation: In RNA-seq, certain biological RNAs (like highly expressed genes or rRNA contamination) will naturally be overrepresented. Removing these sequences will discard genuine genes and can fragment your assembly [34].

- Correct Approach:

- Identify the sequence via BLAST.

- If it is a common contaminant (e.g., rRNA) and the level is exceptionally high, it indicates an issue with the library prep's rRNA depletion step. In this case, it is better to address this biologically or note it as a limitation rather than filtering it out bioinformatically, which can introduce bias [34].

A new overrepresented sequence appeared after trimming. What happened?

- Cause: This is often a normalization effect. By removing the most dominant sequences (e.g., adapters), other sequences that were previously "hidden" in the background now constitute a larger relative fraction of the library and are flagged by FastQC [34].

- Solution: This is usually not a cause for alarm. Check the nature of the new sequence. If it is not an adapter or a primer, it is likely a biological signal.

How do I handle persistent poly-G tails in my data?

- Cause: Poly-G tails are a common artifact in Illumina's two-color sequencing systems (like NextSeq and NovaSeq) when the sequencer reads "into the dark" after the insert DNA has ended [36].

- Solution:

- fastp: Use the built-in

--trim_poly_goption [35]. - BBduk (from BBTools): This is a highly effective alternative. A recommended command is:

- fastp: Use the built-in

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and their functions for a standard RNA-seq preprocessing experiment.

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Adapter Sequence File (e.g., TruSeq3-SE.fa) | A FASTA file containing adapter sequences used for their bioinformatic removal during trimming [33]. |

| High-Quality Reference Genome | Essential for post-alignment quality control steps to calculate metrics like mapping rate and coverage uniformity [25]. |

| Quality Control Metrics (Q30, Mapping Rate, etc.) | Quantitative benchmarks (e.g., >70% mapping rate) used to determine data quality and decide on sample inclusion/exclusion [25]. |

Best Practices for Read Trimming and Adapter Removal Without Data Loss

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is read trimming necessary for RNA-seq data? Read trimming is a critical preprocessing step to remove technical sequences that can interfere with downstream analysis. This primarily includes adapter sequences, which are added during library preparation to bind fragments to the sequencing flow cell, and low-quality bases at the ends of reads caused by sequencing errors. If not removed, adapter sequences can lead to inaccurate alignment to the reference genome and skew gene expression estimates. Trimming also involves filtering out very short reads that remain after processing, which can map unreliably to multiple genomic locations [28] [38].

2. Is trimming always required for RNA-seq analysis? Not always. The necessity of trimming can depend on your downstream analysis tools and goals. For standard differential gene expression analysis using modern, splice-aware aligners like STAR or HISAT2, or pseudo-aligners like Kallisto or Salmon, explicit read trimming may be optional. These tools perform "soft-clipping," internally ignoring non-matching sequences at read ends, which can include adapter sequences. However, for applications like de novo transcriptome assembly, variant calling, or genome annotation, trimming is highly recommended for optimal results [39].

3. What are the key steps in a typical read trimming workflow? A standard workflow involves three main actions, which can be performed by a single tool:

- Adapter Trimming: Identification and removal of adapter sequences from the reads.

- Quality Trimming: Trimming of bases from the 3' and/or 5' ends that fall below a specified quality score threshold.

- Length Filtering: Discarding any reads that, after trimming, are shorter than a minimum length (e.g., 35-50 base pairs), as they are difficult to map uniquely [39] [38] [40].

4. How can I minimize the loss of biological data during trimming? To preserve data integrity:

- Use a paired-end mode when trimming paired-end sequencing data. Tools like

fastpandBBdukcan coordinate the trimming of both reads in a pair, ensuring they remain properly synchronized for downstream alignment [39] [40]. - Avoid over-trimming. Excessively aggressive quality trimming can shorten reads unnecessarily and reduce mapping rates. Rely on quality reports from tools like

FastQCto guide your threshold settings [28]. - Set a reasonable minimum length threshold. Discarding only very short reads (e.g., < 50 bp) prevents the retention of reads that would map ambiguously [39].

5. What are polyG tails, and why should they be removed?

PolyG tails are long sequences of G nucleotides (GGGGG...) that are a specific artifact of Illumina sequencing platforms that use two-color imaging chemistry, such as the NextSeq and NovaSeq. They occur when the sequencer encounters a "dark" cycle with no signal and incorrectly calls it as a G. These tails do not represent biological sequence and can prevent reads from mapping correctly to the reference genome. Tools like fastp can detect and remove them automatically [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Alignment Rates After Trimming

Symptoms:

- Low percentage of reads successfully aligning to the reference genome.

- High percentage of reads flagged as unmapped.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Overly aggressive trimming. Trimming too many bases can make reads too short or remove legitimate biological sequence.

- Solution: Re-run trimming with a less stringent quality threshold (e.g., Q20 instead of Q30) or a shorter sliding window. Check the tool's documentation for best practices [28].

- Cause: Incorrect adapter sequences specified. Using the wrong adapter sequence will cause the tool to fail to find and remove the contaminating sequence.

Problem 2: A Large Proportion of Reads Discarded by the Length Filter

Symptoms:

- A high number of reads are removed for being too short after trimming.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: High adapter content. If your RNA fragments are shorter than the read length, the sequencer will read through the fragment and into the adapter on the other side, resulting in a significant portion of the read being adapter sequence. When this adapter is trimmed, the remaining biological sequence may be very short [41] [38].

- Solution: This is often an issue with the library preparation, not the trimming itself. For future experiments, use library quantification methods that select for appropriate fragment sizes. For current data, you may need to accept a lower number of usable reads or consider using an aligner that is more tolerant of short reads for this specific dataset.

Problem 3: Persistent Adapter Contamination in Downstream Analysis

Symptoms:

- Adapter sequences are still detectable in post-trimming quality control reports (e.g., from

FastQC).

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incomplete adapter trimming. Some adapter sequences may be partial or divergent.

- Solution: Use a trimming tool that allows for partial matching. Tools like

BBdukallow you to set parameters likek(k-mer length) andhdist(hamming distance, i.e., number of allowed mismatches) to catch more variants of the adapter sequence [39] [42]. For example, usingk=23 mink=11 hdist=1allows for more sensitive detection.

- Solution: Use a trimming tool that allows for partial matching. Tools like

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Trimming Efficacy

To objectively evaluate the success of your trimming protocol and its impact on data analysis, you can implement the following comparative workflow.

Methodology: Comparative Trimming and Alignment

- Data Splitting: Start with your raw RNA-seq FASTQ files.

- Parallel Processing: Process the data through two paths simultaneously:

- Path A (Trimmed): Perform adapter and quality trimming using your tool of choice (e.g.,

fastp). - Path B (Untrimmed): Skip the trimming step.

- Path A (Trimmed): Perform adapter and quality trimming using your tool of choice (e.g.,

- Alignment: Align the reads from both paths using the same splice-aware aligner (e.g., HISAT2 or STAR) and identical parameters [43].

- Quantification: Generate read counts for each gene using a tool like

featureCounts. - Quality Assessment: Compare the following metrics between the two paths:

- Alignment Rate: The percentage of reads that successfully map to the genome.

- Multi-mapping Rate: The percentage of reads that map to multiple locations.

- Exonic/Intronic Mapping Rate: The distribution of reads across genic features.

- Number of Genes Detected: The count of genes with expression above a minimum threshold.

The diagram below illustrates this experimental setup.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and their functions for managing RNA-seq read quality.

| Tool/Material | Primary Function | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC [28] [43] | Quality control check on raw sequence data. | Generates a visual report to identify issues like adapter contamination and low-quality bases. Essential for deciding if trimming is needed. |

| fastp | All-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. | Performs adapter trimming, quality filtering, polyG removal, and length filtering. Known for its speed and integrated quality reporting [40]. |

| BBduk (BBTools suite) | Trimming and filtering of reads. | Highly configurable for adapter and quality trimming. Effective in paired-end mode and known for its computational efficiency [39] [42]. |

| Trimmomatic | Flexible tool for trimming and filtering. | A well-established tool that uses a sliding window for quality trimming and allows for precise specification of adapter sequences [28] [38]. |

| Cutadapt | Specialized tool for finding and removing adapter sequences. | Particularly effective for removing specific adapter sequences in single-end data or when precise control over adapter matching is required [39] [38]. |

| STAR / HISAT2 | Splice-aware reference genome aligners. | These aligners can "soft-clip" adapter sequences without the need for pre-trimming, making them robust for standard differential expression analysis [39] [43]. |

The table below summarizes the core metrics to assess when evaluating a trimming protocol, based on the comparative methodology described above.

| Metric | Expected Outcome with Optimal Trimming | Potential Pitfall from Over- or Under-Trimmming |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Alignment Rate | Increases or remains high. | Decreases if trimming is too aggressive (reads become too short). |

| Multi-mapping Rate | Decreases. | Increases if reads are trimmed too short, losing unique mapping information. |

| Adapter Content (Post-Trim) | Reduced to near zero. | Remains high if trimming parameters are incorrect (e.g., wrong adapter sequence). |

| Number of Genes Detected | Stable or slightly increased. | Decreases significantly if excessive data is lost during trimming. |

| PCR Duplicate Level | May help reduce artifacts. | Can be inflated if low-quality or adapter-laden reads are not removed [2]. |

Workflow Diagram: Read Trimming Decision Process

The following diagram provides a logical flowchart to guide researchers in deciding whether and how to trim their RNA-seq data.

This guide provides troubleshooting for low mapping rates and coverage uniformity issues in RNA-seq analysis, framed within a broader thesis on poor RNA-seq data quality.

Why is my mapping rate with HISAT2 or STAR so low?

Low mapping rates can stem from data quality issues, contamination, or incorrect analysis parameters. The table below summarizes common causes and evidence.

| Cause Category | Specific Cause | Supporting Evidence from Logs/QC |

|---|---|---|

| Contamination | Sample mislabeling or cross-species contamination [44]. | BLAST of unmapped reads matches unexpected species [44]. |

| Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) contamination [45] [46]. | High percentage of multi-mapping reads; >90% of alignments assigned to rRNA repeats [45]. | |

| Data Quality Issues | Presence of adapter sequences or specific library prep artifacts [44] [47]. | FastQC fails "Per base sequence content"; abnormal nucleotide distribution in first 10-12 bases [44] [47]. |

| High degradation or many short fragments [46]. | High percentage of reads unmapped: "too short" [45] [46]. | |

| Reference Genome & Analysis | Using an incomplete reference genome (e.g., lacking haplotype sequences or rRNA scaffolds) [44] [46]. | Low mapping rate even with high-quality reads; improvement when using "primary assembly" or full "toplevel" genome [44]. |

| Incorrect alignment parameters for the data type [45] [46]. | For total RNA-seq: many multimapping reads discarded due to default limits in aligners like STAR [46]. |

Troubleshooting Protocol for Low Mapping Rates

Follow this systematic workflow to diagnose and resolve the issue.

Step 1: Verify Data Quality

- Run FastQC on raw and trimmed reads. Pay close attention to "Per base sequence content," which may show biased nucleotide composition at the start of reads due to library prep protocols (e.g., Clontech SMARTer kits), indicating a need for 5' trimming [44] [47].

- Use Trimmomatic or similar tools to trim low-quality bases and adapters. For specific biases in the first bases, consider soft-trimming the first 10-12 bases during alignment or before it [44].

Step 2: Check for Contamination

- For cross-species contamination: Randomly select a few dozen unmapped reads and BLAST them against the NCBI nt database. This can quickly reveal if your sample was mislabeled or contaminated (e.g., human cell line data mapping to hamster) [44].

- For rRNA contamination: Align reads to an rRNA sequence database or use tools like RNA-QC-Chain's rRNA-filter to identify and remove ribosomal reads [11]. Tools like featureCounts can quantify the proportion of alignments falling within rRNA annotations [45].

Step 3: Inspect Analysis Parameters

- Reference Genome: Ensure you are using a comprehensive reference, including unplaced and un-localized scaffolds, as these can contain repetitive elements like rRNA genes. Aligners may report reads mapping to these regions as unmapped if the scaffolds are missing from your reference [44].

- Alignment Parameters: For data with high multimapping potential (e.g., total RNA-seq), adjust aligner parameters. In STAR, consider increasing

--outFilterMultimapNmaxfrom the default (10) to allow more multi-mappings [46]. For HISAT2, using the--rna-strandnessparameter correctly is crucial for stranded libraries [48].

Step 4 and 5: Implement Fix and Re-evaluate

- Apply the specific fix (e.g., trimming, changing reference genome, adjusting parameters) and re-run your alignment. The mapping rate should improve if the root cause was correctly identified [44].

How do I check for and improve coverage uniformity across genes?

Non-uniform coverage can bias expression estimates and hinder the detection of genuine differential expression. It is a silent threat that can skew analysis [7].

Diagnostic and Improvement Protocol for Coverage Uniformity

Diagnosis:

- Use RSeQC or the SAM-stats module of RNA-QC-Chain to generate a gene body coverage plot [11]. This plot scales all transcripts to 100 bins and shows the average read coverage at each bin. Ideal coverage is a flat line from 5' to 3'. A downward slope at either end indicates degradation or bias.

Improvement:

- While library prep issues are hard to fix post-sequencing, ensuring rigorous RNA Quality Control during the wet-lab phase is critical. Check RNA Integrity Number (RIN) scores before sequencing.

- In silico, ensure your analysis pipeline uses a splice-aware aligner (HISAT2, STAR) with default parameters that are optimized for detecting spliced reads, which helps ensure reads are correctly distributed across exon-intron boundaries [49].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and tools for performing robust RNA-seq alignment and QC.

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| HISAT2 | A splice-aware aligner that maps RNA-seq reads to a reference genome. It is fast, memory-efficient, and can discover novel splice sites [49]. |

| STAR | Another popular splice-aware aligner that performs accurate alignment of RNA-seq reads, especially useful for detecting splice junctions [45] [49]. |

| FastQC | A quality control tool that provides an overview of sequencing data quality, including base quality scores, adapter contamination, and sequence composition [11] [48]. |

| Trimmomatic | A flexible tool used to trim adapters and low-quality bases from sequencing reads, improving subsequent mapping rates [44]. |

| RNA-QC-Chain | A comprehensive QC pipeline specifically for RNA-Seq data. It performs sequencing-quality assessment/trimming, rRNA/contamination filtering, and alignment statistics reporting [11]. |

| StringTie | Used after alignment for transcript assembly and quantification of expression levels. It works with HISAT2/STAR output to estimate transcript abundance [49]. |

| BLAST | Used to identify the species origin of unmapped reads by comparing them to a large public sequence database, helping diagnose sample contamination [44]. |

| SILVA Database | A curated database of ribosomal RNA sequences. Used with tools like rRNA-filter to identify and remove rRNA contaminants from the dataset [11]. |

I have confirmed rRNA contamination. What should I do next?

If your analysis reveals significant rRNA contamination, you have several options:

- Proceed with Caution: If the proportion of rRNA is not overwhelmingly high and your mapping rate to the target genome is still acceptable for your biological question, you can proceed with downstream analysis. Be sure to document the issue.

- Bioinformatic Filtering: You can subtract the reads that align to rRNA sequences from your FASTQ files before re-running the genome alignment. Tools like RNA-QC-Chain's rRNA-filter are designed for this purpose [11].

- Wet-lab Investigation: For future experiments, investigate more robust rRNA depletion protocols during library preparation to prevent the issue at the source.

Leveraging Spike-in Controls (ERCC, SIRV) for Technical Performance Monitoring

Spike-in controls are synthetic RNA molecules of known sequence and concentration added to RNA samples before library preparation. They undergo the entire RNA-seq workflow alongside endogenous RNA, providing an internal standard to monitor technical performance, quantify biases, and enable accurate normalization [50]. In the context of troubleshooting poor RNA-seq data quality, they provide an objective "ground truth" to diagnose whether issues originate from wet-lab procedures or bioinformatics analysis.

The two most common spike-in systems are the External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) and the Spike-in RNA Variants (SIRV) sets [50] [51]. The ERCC set consists of 92 mono-exonic transcripts that span a wide dynamic range of abundances, making them ideal for assessing sensitivity, dynamic range, and linearity [51] [52]. The SIRV set is designed to mimic complex eukaryotic transcriptomes with multiple alternatively spliced isoforms from a single gene locus, allowing for the evaluation of transcriptome complexity, isoform quantification, and detection of differential splicing [50].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

How do I determine if my RNA-seq experiment has failed technically?

Use the following checklist to diagnose potential technical failures by analyzing your spike-in data.

Table: Diagnostic Checklist for Technical Failures using Spike-in Controls

| Diagnostic Check | How to Assess It | What a Problem Indicates |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in Detection | Check the number of spike-in transcripts detected above a minimum count threshold. | Low detection suggests issues with spike-in addition, library prep efficiency, or insufficient sequencing depth. |

| Correlation with Expected Abundance | Calculate the Pearson correlation between observed spike-in read counts and their known input concentrations [51]. | A low correlation coefficient (e.g., <0.95 for ERCCs [53]) indicates poor accuracy in quantification, potentially from amplification biases or protocol-specific issues. |

| Dynamic Range | Plot observed log2(read counts) against log2(expected concentration) for ERCCs. The slope should be close to 1 [51]. | A compressed dynamic range suggests limited sensitivity, often due to excessive PCR duplication or poor library complexity. |

| Coverage Uniformity (for SIRVs) | Check if coverage across SIRV isoforms is uniform. Use metrics like the coefficient of deviation (CoD) [50]. | Inconsistent coverage indicates sequence-specific biases (e.g., from GC content or fragmentation). |

My spike-in coverage is highly variable. What does this mean, and how can I fix it?

High variability in spike-in coverage, especially for controls of similar expected abundance, points to technical noise and bias introduced during the library preparation.

- Potential Cause 1: Inefficient or Biased Adapter Ligation. This is a common issue in small RNA-seq and can affect all protocols [54].

- Solution: Use a diverse panel of spike-ins with varied GC content and sequences to better capture this bias. Normalize your endogenous data using spike-in-derived size factors to correct for this technical variation [55].

- Potential Cause 2: PCR Amplification Bias. Some molecules are amplified more efficiently than others during PCR.

- Solution: Integrate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) into your workflow. UMIs allow for the accurate identification and correction of PCR duplicates, providing a truer representation of the original transcript abundance [52]. Optimize PCR cycle numbers to use the minimum required.

Should I use spike-ins for normalization, and what are the pitfalls?

Spike-in normalization is a powerful alternative to endogenous gene-based methods (e.g., TMM), especially in single-cell RNA-seq or when global RNA content varies significantly between samples (e.g., in different cell types or drug treatments) [55].

- When to Use It: It is the preferred method when the total mRNA content per cell is not constant across samples, as it does not assume a stable expression profile [55].

- Common Pitfalls and Solutions:

- Pitfall 1: Inconsistent Spike-in Addition. The core assumption is that the same amount of spike-in RNA is added to each sample.

- Solution: A mixture experiment using two different spike-in sets (e.g., ERCC and SIRV) has demonstrated that the variance in added volume is quantitatively negligible in plate-based protocols, validating the reliability of this approach [55]. Always prepare a master mix of spike-ins for your entire experiment to ensure consistency.

- Pitfall 2: Spike-in and Endogenous RNA Behave Differently. Synthetic transcripts may not perfectly mimic endogenous RNA biology.

- Solution: Choose spike-ins that match your RNA class. For mRNA-seq, use polyadenylated controls like SIRVs. Research shows that while not perfect, spike-ins are reliable enough for scaling normalization, and their use has only minor effects on downstream analyses like differential expression [55].

- Pitfall 3: Insufficient Spike-in Reads. If spike-ins are added at too low a level, their counts will be too noisy for reliable normalization.

- Solution: A typical target is for 1% of all NGS reads to map to the spike-in genome. This might be increased to 2-5% for setups with low read depth (< 5 million reads) [50].

Why do my results look different when I use different mRNA-enrichment protocols?

Different mRNA-enrichment protocols (e.g., poly-A selection vs. ribosomal RNA depletion) introduce specific and reproducible biases, which spike-ins can help you identify.

- The Evidence: A large multi-center benchmarking study involving 45 laboratories found that the choice of experimental protocol, particularly mRNA enrichment and strandedness, is a primary source of inter-laboratory variation in gene expression measurements [53].

- The Solution: You cannot directly compare data normalized using spike-ins from different enrichment protocols without batch correction. The spike-in data will reveal this protocol-specific bias. When designing a multi-site study, standardize the library preparation protocol across all laboratories or, if that's not possible, use the same batch of spike-in controls and perform rigorous batch effect correction during analysis [53].

Experimental Protocols & Best Practices

Detailed Protocol: Using Spike-in Controls for RNA-seq

This protocol outlines the key steps for integrating spike-in controls into a standard RNA-seq workflow.

Key Steps Explained:

- Spike-in Addition: Add a predetermined amount of your chosen spike-in mix (ERCC, SIRV, or a combination) to a fixed quantity of your purified total RNA sample. This can be done after RNA extraction or at an upstream stage like cell lysis for single-cell applications [50]. Critical: Use a master mix of spike-ins for all samples in an experiment to ensure consistency.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Proceed with your standard RNA-seq protocol. The spike-in RNAs are polyadenylated and can be used with poly(A)-enrichment protocols [50]. They are compatible with all major sequencing platforms (Illumina, IonTorrent, PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) [50].

- Read Mapping: Map the sequencing reads to a combined reference index. This index should include the standard reference genome for your organism and the "SIRVome" or ERCC genome file, which details the spike-in transcript sequences and annotations [50]. This ensures reads are correctly assigned to their origin.

- Analysis and Quality Control:

- Quality Metrics: Calculate metrics such as the Coefficient of Deviation (CoD) by comparing measured coverage to expected coverage, precision (statistical variability), and accuracy (statistical bias) from the spike-in data. These metrics reflect the situation in the endogenous RNA dataset [50].

- Normalization: Use the spike-in counts to calculate cell-specific or sample-specific scaling factors. A common method is to scale counts such that the total spike-in count is the same across samples [55].

- Performance Dashboard: Use tools like the

erccdashboardR package to generate a standard dashboard of performance metrics. This includes Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves to assess the diagnostic performance of differential expression detection, Limit of Detection of Ratio (LODR) estimates, and plots of ratio measurement variability and bias [51].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Spike-in Controlled RNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-in Mixes (e.g., Ambion ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix) | Assess dynamic range, limit of detection, and linearity of quantification. Acts as a truth set for differential expression [51] [52]. | 92 mono-exonic transcripts; abundances span a 2^20 dynamic range; organized into subpools with defined ratios (e.g., 4:1, 1:1) between Mix A and B. |

| SIRV Spike-in Modules (Lexogen) | Evaluate accuracy of isoform identification, quantification, and differential splicing analysis [50]. | Modular design (isoform module, long module); synthetic transcripts with complex alternative splicing; can be mixed with ERCCs. |

| Sequins (Sequencing Spike-ins) | A competitive synthetic spike-in system representing full-length, spliced mRNA isoforms and fusion genes to benchmark transcript assembly and quantification [50] [56]. | Artificial sequences aligned to an in silico chromosome; emulates alternative splicing and differential expression. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Tag individual mRNA molecules to correct for PCR amplification bias and errors, enabling accurate digital counting [52]. | Short, random nucleotide sequences (4-12 bp); added during reverse transcription; allow bioinformatic collapse of PCR duplicates. |

| ERCCdashboard R Package | A software tool that produces a standardized dashboard of technical performance metrics from ERCC spike-in data [51]. | Generates ROC curves, AUC statistics, LODR estimates, and plots of technical variability and bias. |

The quantitative data derived from spike-ins provides a comprehensive view of your RNA-seq assay's performance.

Table: Key Performance Metrics Derived from Spike-in Controls

| Metric | Description | How it is Calculated | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | The range of abundances over which transcripts can be detected and quantified. | Plot observed ERCC read counts vs. known input concentration over the 2^20 design range [51]. | A compressed range indicates poor sensitivity or high background noise. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The minimum number of input transcript molecules required for reliable detection. | Model the relationship between detection probability and input concentration using ERCC data [54]. | Informs on the ability to detect low-abundance transcripts. |

| Accuracy | A measure of the statistical bias; how close the measured value is to the true value. | Compare the measured abundance (e.g., FPKM, TPM) of each spike-in to its known concentration [50]. | Low accuracy indicates systematic bias in the workflow. |

| Precision | A measure of the statistical variability or technical noise. | Measure the coefficient of variation of spike-in counts across technical replicates [50]. | High precision (low variability) is crucial for reproducible results. |

| Diagnostic Power (AUC) | The ability to correctly identify differentially expressed genes. | Use ERCCs with known fold-changes (e.g., 4:1, 1:2) in a ROC curve analysis [51]. | AUC=1 is perfect, AUC=0.5 is no better than random. High AUC is desired. |