A Researcher's Guide to Validating RNA-Seq Results with qPCR: Strategies, Protocols, and Best Practices

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to design and execute robust validation of RNA-Seq data using qPCR.

A Researcher's Guide to Validating RNA-Seq Results with qPCR: Strategies, Protocols, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to design and execute robust validation of RNA-Seq data using qPCR. It covers the foundational principles explaining when and why validation is critical, detailed methodological protocols for reference gene selection and assay optimization, strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls, and a systematic approach for comparative analysis between the two technologies. By synthesizing current methodologies and software tools, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and reproducibility of gene expression studies in biomedical and clinical research.

The Why and When: Establishing the Need for RNA-Seq Validation with qPCR

Table of Contents

- Introduction to the Technologies

- Quantifying the Concordance: A Data-Driven Perspective

- Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

- Factors Influencing Concordance and Discordance

- A Practical Guide for Validation Experiments

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

In the field of transcriptomics, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) are foundational techniques for gene expression analysis. RNA-seq provides an unbiased, genome-wide view of the transcriptome, enabling the discovery of novel transcripts and the quantification of known genes across a wide dynamic range [1] [2]. In contrast, qPCR is a targeted, highly sensitive method used to precisely measure the abundance of a select number of pre-defined genes, and it is often considered the gold standard for gene expression validation due to its maturity and well-understood workflow [3] [4]. The central question this guide addresses is: when these two powerful techniques are used to measure the same biological phenomenon, how closely do their results agree? Understanding the degree and drivers of this concordance is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on these data for making scientific conclusions and clinical decisions.

Quantifying the Concordance: A Data-Driven Perspective

Overall, numerous independent studies report a strong correlation between gene expression measurements obtained from RNA-seq and qPCR. However, the concordance is not perfect, and the level of agreement can be significantly influenced by the specific bioinformatic tools used and the characteristics of the genes being studied.

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from several benchmarking studies that compared various RNA-seq analysis workflows against qPCR.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of RNA-seq Analysis Workflows vs. qPCR

| Metric / Study | Everaert et al. (as cited in [3]) | Soneson et al. [5] | Kumar et al. [1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Concordance | ~80-85% of genes show concordant differential expression (DE) status. | High fold-change correlation (Pearson R² ~0.93) across 5 workflows. | Varies significantly with the DEG tool. |

| Non-Concordant Genes | ~15-20% of genes show non-concordant DE; ~1.8% are severely non-concordant (fold change >2). | 15.1% (Tophat-HTSeq) to 19.4% (Salmon) of genes non-concordant. | High false-positive rate for Cuffdiff2; high false-negative rates for DESeq2 and TSPM. |

| Characteristics of Discordant Genes | Typically lower expressed and shorter. | Smaller, fewer exons, and lower expressed. | Not specified. |

| Tool Performance | Not the primary focus. | All five workflows showed highly similar performance. | edgeR showed the best balance: 76.67% sensitivity, 90.91% specificity. |

These findings highlight that while overall agreement is high, a small but consistent subset of genes may yield discrepant results. The following diagram illustrates the primary factors that lead to this discordance.

Factors Leading to Discordance Between RNA-seq and qPCR

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

To objectively benchmark RNA-seq results against qPCR, a rigorous and standardized experimental approach is required. The following workflow, derived from established validation studies, outlines the key steps.

Table 2: Key Steps for a Robust RNA-seq and qPCR Comparison Study

| Phase | Step | Description & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Experimental Design | Biological Replication | Use a sufficient number of biological replicates (not technical) to capture true biological variation. This is critical for statistical power [1] [4]. |

| Sample Selection | Ideally, use independent biological samples for the RNA-seq and qPCR validation to confirm both the technology and the underlying biology [4]. | |

| 2. RNA-seq Wet Lab | RNA Extraction & QC | Extract high-quality, DNA-free RNA. Assess integrity (e.g., RIN score >9) and quantity using spectrophotometry or bioanalyzer [6]. |

| Library Preparation & Sequencing | Use a standardized, high-throughput protocol (e.g., Illumina). Be aware that different library prep kits can introduce bias [2]. | |

| 3. RNA-seq Dry Lab | Read Alignment & Quantification | Process raw reads (FASTQ) using a benchmarked workflow. Common choices include STAR-HTSeq (alignment-based) or Kallisto/Salmon (pseudoalignment) [5]. |

| Differential Expression Analysis | Apply statistical models (e.g., from edgeR, DESeq2) to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), using an adjusted p-value (e.g., FDR < 0.05) and a minimum fold-change threshold [1]. | |

| 4. qPCR Wet Lab | Gene Selection | Select ~10-20 genes for validation. Include a mix of significantly up-/down-regulated DEGs, genes with varying expression levels and fold-changes, and genes relevant to the study's hypothesis [7]. |

| Reverse Transcription & qPCR | Use the same RNA samples (or independent ones) for cDNA synthesis. Perform qPCR in technical replicates using optimized, efficient primers. Adhere to MIQE guidelines [3] [6]. | |

| Reference Gene Validation | Use a robust statistical approach (e.g., NormFinder) to select stable reference genes from a panel of candidates for reliable normalization. Do not assume stability [6]. | |

| 5. Data Comparison | Correlation Analysis | Calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient between the log₂ fold changes obtained from RNA-seq and qPCR. A correlation of ≥0.7 is generally considered good agreement [7]. |

| Concordance Assessment | Classify genes based on their differential expression status in both methods to determine the percentage of concordant and non-concordant genes, as shown in Table 1 [5]. |

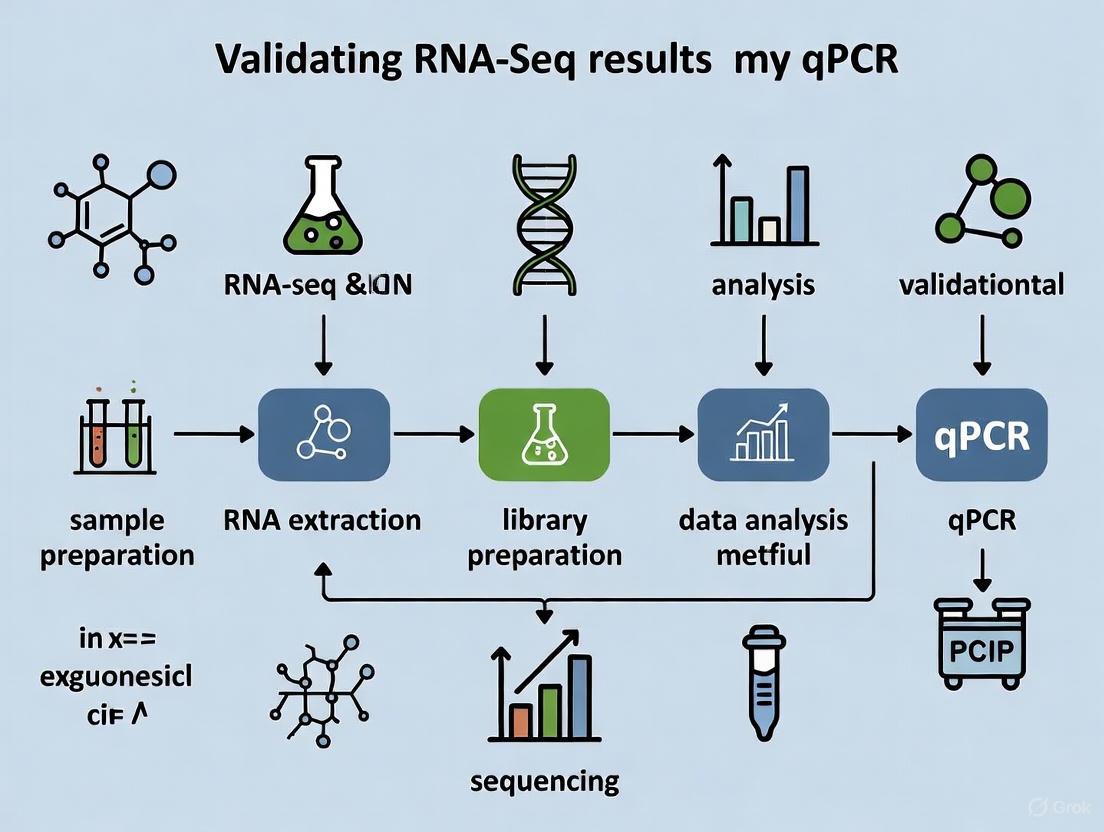

The entire workflow, from sample preparation to data interpretation, is summarized in the following diagram.

Experimental Workflow for RNA-seq and qPCR Comparison

Factors Influencing Concordance and Discordance

As indicated by the data in Table 1, concordance is not universal. Key factors that influence agreement include:

Bioinformatic Tools: The choice of software for differential expression analysis can dramatically impact the results. One study found that the false-positivity rate of Cuffdiff2 and false-negativity rates of DESeq2 were high, whereas edgeR demonstrated a more optimal balance of sensitivity (76.67%) and specificity (90.91%) when validated against qPCR [1]. Normalization methods are also critical, especially in experiments with global expression shifts, where standard assumptions can break down [8].

Gene Features: Discrepancies are not random. Genes that are shorter, have fewer exons, and are expressed at low levels are consistently overrepresented among non-concordant results [3] [5]. For these genes, small absolute changes can lead to large, and potentially unreliable, fold-changes in RNA-seq data.

Complex Loci: Genes with high sequence similarity, such as those in the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) family, present a particular challenge. Standard RNA-seq alignment methods struggle with their extreme polymorphism, leading to mapping errors. While specialized pipelines have been developed, a 2023 study still found only a moderate correlation (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53) between RNA-seq and qPCR for HLA class I genes [9].

Experimental Design: Perhaps the most critical factor is the use of an adequate number of biological replicates. Studies with low replication have low statistical power and are more likely to produce unreliable DEG lists that fail validation. Sample pooling strategies, intended to save costs, have been shown to introduce pooling bias and suffer from very low positive predictive value, making them a poor substitute for increasing biological replication [1].

A Practical Guide for Validation Experiments

The question of whether qPCR validation is necessary does not have a universal answer. The following guidance, synthesized from the literature, helps determine the best path for your research.

qPCR Validation is Recommended When:

- The core biological conclusion of a study rests on the expression changes of only a few key genes [3] [4].

- The RNA-seq experiment was conducted with a small number of biological replicates, limiting statistical power [4].

- You need to confirm findings in an independent cohort of samples, thus validating both the technical result and the broader biological relevance [10] [4].

- You are studying genes known to be problematic, such as low-expressed, short, or highly polymorphic genes [3] [9].

qPCR Validation May Be Unnecessary When:

- The RNA-seq data is of high quality, based on a sufficient number of biological replicates, and has been processed with a robust, modern analysis pipeline [3] [10].

- The RNA-seq results are used as a hypothesis-generating screen that will be followed up with functional studies (e.g., at the protein level) [4].

- The chosen validation path is to perform a second, independent RNA-seq experiment on a new set of samples to confirm reproducibility [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and materials required for conducting the experiments described in this guide.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq and qPCR Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolate high-quality, intact total RNA from biological samples. | Select kits optimized for your sample type (e.g., tissue, cells). Must include a DNase step to remove genomic DNA contamination [6]. |

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) Analyzer | Assess the quality and degradation level of RNA samples. | A RIN score of ≥9 is generally required for reliable RNA-seq and qPCR results [6]. |

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | Prepare sequencing libraries from RNA by converting it to cDNA, fragmenting, and adding platform-specific adapters. | Different kits (e.g., Illumina TruSeq) have varying performance; be consistent within a study. Be aware of biases in amplification and fragmentation [2]. |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA templates for qPCR. | Use a consistent protocol and the same amount of input RNA across samples to ensure comparability. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides the enzymes, nucleotides, and buffer necessary for the PCR amplification and fluorescence detection. | Use a reagent compatible with your detection chemistry (e.g., SYBR Green or TaqMan). Verify primer amplification efficiency [6]. |

| Validated qPCR Primers | Specifically amplify the target and reference genes. | Primers must be designed to be highly specific and efficient. Amplicons should be relatively small (80-150 bp). Sequences should be provided in publications [6]. |

| Stable Reference Genes | Used for normalization of qPCR data to account for technical variation. | Critical: Genes must be empirically validated for stability under your specific experimental conditions (e.g., using NormFinder or GeNorm). Do not rely on presumed "housekeeping" genes [6]. |

In the evolving landscape of molecular biology, RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has become the cornerstone for comprehensive transcriptome analysis, enabling genome-wide quantification of RNA abundance with extensive coverage and fine resolution [11]. However, this powerful technology generates discoveries that require confirmation through independent methods. Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) remains the gold standard for validating transcriptional biomarkers due to its superior sensitivity, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness [12]. The reliability of molecular diagnostics and drug development pipelines depends on recognizing when this validation is most critical—particularly when confronting the challenges of low expression levels and small fold changes where technical artifacts and biological variability most severely compromise data interpretation.

This guide objectively compares validation approaches and provides a structured framework for identifying and addressing critical pitfalls in transcriptional biomarker development.

Why RNA-Seq Requires Validation: Technical Limitations and Biases

While RNA-Seq provides unprecedented transcriptional coverage, its workflow introduces multiple potential biases that can distort expression measurements. Understanding these limitations is fundamental to recognizing when validation becomes essential.

Table 1: Key Technical Challenges in RNA-Seq Affecting Expression Accuracy

| Technical Challenge | Impact on Expression Data | Consequences for Low Expression/Small FCs |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Depth Variation | Samples with more total reads show artificially higher counts [11] | Small true differences can be masked or exaggerated |

| GC Content Bias | Variable amplification based on nucleotide composition [11] | Particularly affects already low-count genes |

| Ambiguous Read Mapping | Reads mapping to multiple genomic locations inflate counts [11] | False positives for genes with homologous family members |

| PCR Amplification Artifacts | Uneven amplification during library preparation [11] | Introduces noise that overwhelms small biological signals |

| RNA Quality Degradation | 3' bias in degraded samples alters transcript representation [11] | Creates systematic errors across experimental groups |

The multi-step RNA-Seq workflow—from RNA extraction to cDNA conversion, sequencing, and bioinformatic processing—accumulates technical variations that normalization strategies cannot fully eliminate [11]. These issues are particularly problematic for genes with low baseline expression or when expecting subtle transcriptional changes (typically fold changes below 1.5), where the signal-to-noise ratio is inherently unfavorable.

When Validation Becomes Critical: Identifying High-Risk Scenarios

The Challenge of Low Expression Genes

Genes with low transcript abundance pose significant detection challenges in RNA-Seq. With limited sequencing depth, the stochastic sampling of rare transcripts leads to high quantitative variability and unreliable fold-change estimates [11]. The minimal information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments (MIQE) guidelines emphasizes that low-copy targets require rigorous validation due to their susceptibility to technical noise [12]. In diagnostic applications, where liquid biopsies often contain minimal RNA, this becomes particularly crucial for avoiding false positives.

The Perils of Small Fold Changes

Biologically relevant but subtle expression differences (typically below 1.5-fold) frequently occur in physiological responses, early disease states, and pharmacodynamic effects. These small effects hover near the technical variability threshold of RNA-Seq, making them highly susceptible to normalization artifacts and batch effects [11]. Without qPCR confirmation, these findings risk representing statistical noise rather than biological reality. The Pfaffl model for relative quantification specifically addresses this by incorporating target-specific amplification efficiencies, providing more accurate measurements of subtle changes [13].

Complex Experimental Conditions

Studies comparing multiple tissue types, time courses, or treatment conditions introduce additional variability that complicates RNA-Seq analysis. Reference genes stable in one condition may vary significantly in another, as demonstrated in sunflower senescence studies where expression stability differed across leaf ages and treatments [14]. Validation becomes critical when biological variability intersects with technical variability, requiring careful reference gene selection across all experimental conditions.

qPCR Validation Approaches: A Comparative Guide

Multiple mathematical approaches exist for relative quantification in RT-qPCR, each with distinct strengths and limitations for addressing validation challenges.

Table 2: Comparison of Relative Quantification Methods for qPCR Validation

| Method | Key Principle | Efficiency Handling | Best Application Context | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Cq (2-ΔΔCq) | Assumes optimal and equal efficiency for all amplicons [13] | Fixed at 2 (100% efficiency) [13] | High-abundance targets with validated primer efficiency | Underestimates true expression when efficiency <2 [13] |

| Pfaffl Model | Efficiency-corrected calculation based on standard curves [13] | Incorporates experimentally-derived efficiency values [13] | Small fold changes and low expression targets | Requires dilution series for each amplicon [13] |

| LinRegPCR | Determines efficiency from the exponential phase of individual reactions [13] | Uses mean fluorescence increase per cycle per sample [13] | Situations with reaction inhibition or variable quality | Sensitive to threshold setting in exponential phase [13] |

| qBase Software | GeNorm algorithm with multiple reference gene normalization [14] [13] | Combines efficiency correction with reference gene stability | Complex experimental conditions with variable stability | Requires specific software and multiple reference genes [14] |

Each method demonstrates good correlation in general application, but their performance diverges significantly when applied to low expression or small fold changes [13]. The Liu and Saint method has shown particularly high variability without careful optimization, while efficiency-corrected models like Pfaffl provide more reliable quantification for critical validation scenarios [13].

Experimental Design for Robust Validation

Reference Gene Selection and Stability Assessment

The foundation of reliable qPCR validation rests on proper reference gene selection. Early studies assumed constant expression of housekeeping genes, but research has demonstrated that stability must be empirically proven for each experimental context [14] [13]. As demonstrated in poplar gene expression studies, multiple evaluation approaches (geNorm, BestKeeper, NormFinder) should be employed as they may identify different genes as most stable [14] [13].

For sunflower senescence research, geNorm identified α-TUB1 as most stable, BestKeeper selected β-TUB, while a linear mixed model preferred α-TUB and EF-1α [14]. This condition-specific variation underscores why using multiple reference genes—rather than a single one—significantly improves normalization reliability [14] [13]. The optimal approach validates candidate reference genes across all experimental conditions using dedicated algorithms like NormFinder before final selection [13].

Efficiency Calculations: The Cornerstone of Accurate Quantification

Amplification efficiency dramatically impacts quantification accuracy, particularly for low expression genes and small fold changes. While the comparative Cq method assumes perfect efficiency, this condition is rarely achieved in practice [13]. Efficiency determination through serial dilutions provides a standard approach, but may be influenced by inhibitor dilution [13]. Alternative methods calculating efficiency from the exponential phase of individual reactions (LinRegPCR) offer advantages for problematic reactions [13].

Sample Size and Replication Strategy

Robust validation requires appropriate biological replication. While three replicates per condition is often considered the minimum standard, studies with high biological variability or seeking small effect sizes require greater replication [11]. With only two replicates, the ability to estimate variability and control false discovery rates is greatly reduced, and single replicates do not allow for statistical inference [11]. Power analysis tools like Scotty can help determine optimal sample sizes based on pilot data and expected effect sizes [11].

Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Experiments

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for qPCR Validation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Critical Selection Criteria | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase | Converts RNA to cDNA for amplification [12] | High efficiency, minimal RNase H activity, uniform representation | Critical for low-input samples; affects all downstream results |

| DNA-Specific Fluorescent Dyes | Detects PCR product accumulation during amplification [13] | Specificity, minimal PCR inhibition, broad dynamic range | SYBR Green requires post-amplification melt curve analysis |

| Target-Specific Primers | Amplifies gene of interest with high specificity [13] | Minimal secondary structure, high efficiency (90-110%), specificity验证 | Require validation of single amplification product |

| Reference Gene Assays | Normalizes technical variation between samples [14] [13] | Stable expression across experimental conditions | Multiple genes (≥3) recommended; stability requires validation |

| RNA Quality Assessment Tools | Evaluates RNA integrity before cDNA synthesis [12] | Accurate quantification of degradation and purity | RIN >7.0 generally required for reliable results |

Successful validation of RNA-Seq results, particularly for challenging scenarios involving low expression or small fold changes, requires a comprehensive strategy addressing multiple potential pitfalls. Key elements include: (1) selecting stable, condition-appropriate reference genes; (2) precisely measuring amplification efficiencies using appropriate mathematical models; (3) implementing sufficient biological replication to detect small effects; and (4) applying efficiency-correct quantification methods like the Pfaffl model rather than assuming optimal amplification. By adopting this rigorous framework and adhering to MIQE guidelines, researchers can confidently translate transcriptomic discoveries into reliable biomarkers for diagnostic and therapeutic applications [12].

The normalization of gene expression data, whether from quantitative PCR (qPCR) or RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), is a critical step that directly impacts the validity of research conclusions. For decades, scientists have relied on a limited set of presumed "housekeeping" genes—such as ACTB (β-actin), GAPDH, and 18S rRNA—as internal controls, operating under the assumption that their expression remains constant across all experimental conditions. However, a growing body of evidence reveals that this assumption is fundamentally flawed, as the expression of these traditional reference genes can vary significantly under different physiological, pathological, and experimental conditions. This guide objectively compares the traditional paradigm of using presumed housekeeping genes against the emerging approach of using experimentally validated controls, providing researchers with data-driven insights to enhance the rigor and reproducibility of their gene expression studies.

The Problem with Traditional Housekeeping Genes

Traditional housekeeping genes encode proteins essential for basic cellular functions, leading to their historical selection as normalization controls for qPCR and other gene expression technologies. The core issue with this approach is that no gene is universally stable across all cell types, developmental stages, or experimental treatments.

Documented Instability of Traditional Controls

Numerous studies have demonstrated that classical reference genes can exhibit significant expression variability, potentially leading to erroneous results:

- ACTB (β-actin) was shown to be downregulated in RNA-seq data following specific experimental treatments, making it invalid for normalization in those contexts [15]. Furthermore, actin is upregulated in chronic allograft dysfunction, compromising its utility in transplantation studies [16].

- 18S rRNA has been identified as a biomarker associated with acute rejection in transplant patients, indicating its variable expression in disease states [16].

- TUBB (β-tubulin) is directly targeted by pharmacological agents like colchicine, which disrupts its function and expression, rendering it unsuitable for drug studies [16].

This evidence underscores a critical limitation: relying on a single or small set of a priori selected genes introduces substantial risk of normalization bias.

Underlying Causes of Variability

The expression instability of traditional housekeeping genes stems from several factors:

- Cellular Context Dependence: Basic cellular maintenance requirements differ across tissue types, disease states, and developmental stages.

- Experimental Perturbations: Treatments that affect cell proliferation, metabolism, or cytoskeleton integrity directly impact genes like GAPDH and ACTB.

- Lack of Systematic Validation: Traditional controls were often adopted based on convention rather than rigorous, condition-specific stability testing.

The Emergence of Experimentally Validated Controls

The paradigm is shifting toward identifying normalization genes through empirical testing rather than presumption. This approach leverages high-throughput technologies like RNA-seq to systematically evaluate gene expression stability across specific experimental conditions.

Methodological Framework for Identification

The process for identifying validated controls typically follows this workflow, which can be adapted for various biological systems:

Key Advantages of Empirically Derived Controls

- Condition-Specific Optimization: Controls are tailored to the exact experimental system being studied.

- Multi-Gene Panels: Utilization of gene sets with complementary stability profiles enhances normalization robustness.

- Reduced Bias: Minimizes the risk of normalizing with genes that respond to experimental treatments.

- Enhanced Reproducibility: Improves the consistency and reliability of gene expression measurements.

Quantitative Comparison: Traditional vs. Validated Controls

The superiority of empirically validated controls is demonstrated through multiple quantitative metrics compared to traditional approaches.

Performance Metrics for Reference Genes

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Traditional vs. Experimentally Validated Control Genes

| Metric | Traditional Controls | Experimentally Validated Controls |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Stability (CV) | Highly variable (e.g., GAPDH CV 52.9%, EF1α CV 41.6% in tomato-Pseudomonas pathosystem) [17] | Significantly more stable (e.g., ARD2, VIN3 with CV 12.2%-14.4% in same system) [17] |

| Condition Dependency | High - expression alters in specific diseases, treatments, and developmental stages [16] | Low - systematically selected for stability across target conditions |

| Number of Genes | Typically 1-3 genes | Often 3+ genes combined as normalization factor |

| Biological Validation | Limited - often based on historical use | Comprehensive - includes stability algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper) [17] |

| Impact on Differential Expression Results | Higher risk of false positives/negatives due to inappropriate normalization | More accurate identification of truly differentially expressed genes |

Concordance Between RNA-seq and qPCR with Proper Normalization

Table 2: Impact of Normalization Strategy on Transcriptome Validation

| Parameter | Traditional Normalization | Experimentally Validated Normalization |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq vs. qPCR Concordance | ~80-85% overall agreement [18] | Improved concordance through appropriate control selection |

| Non-Concordant Genes | 15-20% of genes show discrepancies [19] | Reduced discrepancy rate through optimized normalization |

| Severely Non-Concordant Genes | ~1.8% (typically low-expressed, shorter genes) [19] | Better handling of challenging gene classes |

| Differential Expression Validation | Higher false positive rates with traditional controls [1] | Improved validation rates through stable normalization |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Protocol: Identification of Experimental Controls from RNA-seq Data

Principle: Leverage RNA-seq datasets to identify genes with minimal expression variation across target experimental conditions [16] [17].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Experimental Design

- Include a minimum of 5-8 biological replicates per condition

- Encompass all expected experimental variations in the test dataset

- For human kidney allograft study: include biopsies representing normal function, acute rejection, interstitial nephritis, interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy, and polyomavirus nephropathy [16]

RNA Sequencing

- Library Preparation: Use standardized kits (e.g., Ion Ampliseq Transcriptome Human Gene Expression Kit)

- Sequencing Platform: Illumina HiSeq 2000, SOLiD 5500, or similar

- Sequencing Depth: Minimum 10-20 million reads per sample

- Quality Control: Assess RNA integrity (RIN >7), adapter contamination, and mapping rates

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Alignment: Map reads to reference genome (e.g., hg19) using STAR or TopHat2

- Quantification: Generate read counts or FPKM/RPKM values per gene

- Normalization: Apply multiple algorithms (library size, TMM, RPKM, TPM, DESeq) [16]

- Stability Calculation: Compute coefficient of variation (CV) for each gene across all samples

- CV = (Standard Deviation / Mean) × 100%

- Gene Selection: Identify genes with CV below the 2nd percentile across all transcripts

Validation

- Select top 8-12 candidate genes with lowest CV values

- Design qPCR primers with efficiency 90-110%

- Validate expression stability using algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper)

- Establish optimal normalization factor from combination of top stable genes

Case Study: Tomato-Pseudomonas Pathosystem

A comprehensive study compared traditional and RNA-seq derived reference genes in the tomato-Pseudomonas interaction model [17]:

Experimental Design:

- Evaluated 37 different treatment/time-point conditions

- Included Pseudomonas syringae infections, MAMP elicitors, and mock treatments

- Analyzed 34,725 tomato genes from RNA-seq data

Results:

- Traditional genes (GAPDH, EF1α) showed high variability (CV 41.6-52.9%)

- Nine newly identified genes demonstrated superior stability (CV 12.2-14.4%)

- ARD2 and VIN3 emerged as optimal references for this pathosystem

- Validation across multiple immune response conditions confirmed consistent performance

Case Study: Human Kidney Allograft Biopsies

Research on renal allograft biopsies established condition-specific reference genes [16]:

Methodology:

- Analyzed 47,613 transcripts from 30 biopsies spanning multiple pathologies

- Applied nine normalization methods to identify stable genes

- Defined housekeeping genes as those with CV in the lowest 2nd percentile

Key Findings:

- Universal set of 42 housekeeping transcripts common to all normalization methods

- Pathway analysis revealed enrichment in cell morphology maintenance, pyrimidine metabolism, and intracellular protein signaling

- Traditional controls (18S RNA, actin, tubulin) showed significant variability across pathologies

- Established robust normalization framework for transplant immunology studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Reference Gene Validation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) [20] | High-quality RNA extraction with genomic DNA removal |

| cDNA Synthesis Kits | iScript Advanced cDNA Synthesis (Bio-Rad) [20] | Efficient reverse transcription with optimized priming |

| RNA-seq Library Prep | Ion Ampliseq Transcriptome Human Gene Expression Kit [16] | Targeted whole-transcriptome library construction |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green or TaqMan-based chemistries | Sensitive and specific amplification detection |

| Stability Analysis Software | geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper [17] | Algorithmic assessment of candidate reference genes |

| RNA-seq Alignment Tools | STAR, TopHat2, HISAT2 [18] | Accurate read mapping to reference genome |

| Expression Quantification | HTSeq, featureCounts, Kallisto, Salmon [18] | Transcript abundance estimation from mapped reads |

| Reference Gene Panels | Custom-designed primer sets for candidate genes | Multiplex validation of expression stability |

The evidence overwhelmingly supports a transition from presumed housekeeping genes to experimentally validated controls for gene expression normalization. Key findings from comparative analyses indicate:

Traditional housekeeping genes exhibit significant condition-dependent variability that compromises their utility as normalization factors across diverse experimental contexts.

RNA-seq enabled discovery approaches identify more stable control genes with 3-4 fold lower coefficients of variation compared to traditional references.

Multi-gene normalization factors derived from empirically validated controls enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of both qPCR and RNA-seq data analysis.

Field-specific validated controls are emerging for model organisms, pathological conditions, and experimental treatments, providing researchers with optimized tools for their specific applications.

To ensure robust gene expression quantification, researchers should implement systematic validation of reference genes for their specific experimental systems, leveraging high-throughput transcriptomic data where possible. This evidence-based approach to normalization represents a critical advancement in molecular methodology that will enhance the reliability of gene expression studies across biological and biomedical research domains.

In the evolving landscape of genomic research, high-throughput technologies like RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) have become cornerstone methods for comprehensive gene expression profiling. Despite their power to simultaneously measure thousands of transcripts, these discovery-based platforms introduce analytical challenges that necessitate confirmation through more targeted methods. Within this context, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) maintains its position as the gold standard for gene expression validation, combining precision, sensitivity, and reliability that remains unmatched for focused gene expression studies. This guide objectively examines the performance of qPCR as a validation tool alongside alternative technologies, providing researchers with experimental data and methodological frameworks to strengthen their genomic studies.

The Technological Landscape: A Comparative Analysis of Expression Platforms

How qPCR, Microarrays, and RNA-Seq Stack Up

Understanding the relative strengths and limitations of each gene expression technology is crucial for appropriate experimental design and interpretation of results.

Table 1: Platform Comparison for Gene Expression Analysis

| Feature | qPCR | Microarrays | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low to medium (typically <50 genes) | High (thousands of genes) | Very high (entire transcriptome) |

| Dynamic Range | Widest (up to 10⁷-fold) [21] | Constrained [21] [4] | Broad [21] |

| Sensitivity | Highest (can detect single copies) [22] | Moderate | High |

| Cost per Sample | Low for limited targets | Moderate | High |

| Sample Input | Low [21] | Moderate | Moderate to high |

| Background | Well-established, standardized protocols | Established but being phased out | Rapidly evolving, complex analysis |

| Primary Application | Target validation, focused studies | Whole transcriptome profiling (with reference) | Discovery, splicing, novel transcripts |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Independent studies have directly compared the expression measurements obtained from different platforms, providing empirical evidence for their correlation and discrepancies.

Table 2: Cross-Platform Correlation Data from Comparative Studies

| Comparison | Correlation Level (Gene Level) | Correlation Level (Isoform Level) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq vs qPCR | High (R² = 0.82-0.93) [23] | Not typically measured by qPCR | ~85% of genes show consistent fold-changes between MAQCA and MAQCB samples [23] |

| NanoString vs RNA-seq | Moderate (Median Rₛ = 0.68-0.82) [24] | Lower (Median Rₛ = 0.55-0.63) [24] | Consistency varies significantly between gene and isoform quantification |

| Exon-array vs RNA-seq | Moderate to high | Moderate (Median Rₛ = 0.62-0.68) [24] | Agreement on isoform expressions is lower than agreement on gene expressions [24] |

The Validation Paradigm: When and Why qPCR Confirmation is Essential

Establishing Biological Truth Through Multi-Method Confirmation

The principle of validation rests on confirming findings using a method with different technical principles and potential biases. While RNA-seq provides an unprecedented comprehensive view of the transcriptome, several factors justify qPCR confirmation for critical findings:

- Technical Complementarity: qPCR and RNA-seq employ fundamentally different detection principles—targeted amplification versus hybridization and sequencing—reducing the likelihood that the same technical artifacts would affect both methods [4].

- Measurement Precision: For a limited number of targets, qPCR provides superior quantitative accuracy with a wider dynamic range and lower limit of detection compared to sequencing-based methods [21].

- Statistical Reinforcement: When RNA-seq studies use limited biological replicates to reduce costs, qPCR validation on additional samples provides greater confidence in the observed effects [4].

Decision Framework for Validation Experiments

The following workflow outlines a systematic approach for determining when qPCR validation is warranted in high-throughput studies:

Methodological Excellence: Implementing Rigorous qPCR Validation

Experimental Design Considerations

Robust qPCR validation requires careful planning at each experimental stage to ensure biologically meaningful results:

- Biological Replication: Include multiple biological replicates (ideally ≥3) to account for natural variation, with technical replicates (typically 2-3) to assess assay precision [25].

- Control Selection: Implement no-template controls (NTC) to detect contamination, no-reverse-transcription controls (-RT) to assess genomic DNA contamination, and positive controls to confirm assay functionality [25] [22].

- Reference Genes: Select multiple validated reference genes with stable expression across experimental conditions, as unstable references can substantially distort results [26].

Sample Preparation and Quality Assessment

Proper sample handling and quality control are foundational to reliable qPCR data:

- RNA Integrity: Preserve RNA integrity through rapid sample processing, snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen, and proper storage at -80°C [26]. While mishandling (≤10 minutes) before extraction may not critically compromise RNA quality, consistent handling is recommended [26].

- Extraction Methodology: For human skeletal muscle samples, TRIzol-based extraction with 2-propanol precipitation provides higher yields compared to ethanol precipitation [26]. Column-based purifications offer higher purity suitable for sequencing applications [26].

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate RNA purity using spectrophotometric ratios (A260/A280 of 1.8-2.1 indicates pure RNA), with additional integrity assessment through methods like the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) [26].

Assay Design and Validation

Primer and probe design critically impact assay specificity and efficiency:

- Design Parameters: Aim for amplicons of 70-200 bp, primer TM values of 60-62°C (±2°C), and GC content of 35-65%. The probe should have a TM 4-10°C higher than primers without runs of consecutive Gs [25].

- Specificity Verification: Utilize BLAST analysis against species-specific databases to ensure primer/probe specificity and avoid cross-reactivity with related sequences [25] [27].

- SNP Considerations: Design assays to avoid known single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), particularly at the 3' ends of primers, as a single SNP can cause Cq shifts representing >1000-fold expression errors [25].

- Performance Validation: Establish PCR efficiency (90-110% ideal), dynamic range (3-6 log orders), and limit of detection (theoretically 3 molecules with 95% confidence) through serial dilutions [22] [27].

High-Throughput qPCR Implementation

Advanced platforms like the SmartChip Real-Time PCR System enable medium-to-high throughput validation studies using nanoliter reaction volumes (100-200 nL), significantly reducing reagent costs while maintaining sensitivity [28]. These systems support flexible configurations from 6-768 samples and 12-768 targets per run, with data generation for over 10,000 samples per day [28].

Analytical Framework: From Raw Data to Biological Interpretation

Quality Assessment and Normalization

Implement stringent quality control measures before analyzing expression data:

- MIQE Compliance: Adhere to Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines, reporting critical parameters including PCR efficiency, confidence intervals, and normalization methods [22] [26] [27].

- Data Normalization: Apply appropriate normalization strategies using multiple reference genes or cDNA content (with complete RNA removal from samples) to control for technical variation [26].

- Quality Scoring: Utilize systematic scoring methods like the "dots in boxes" approach that simultaneously evaluates PCR efficiency, dynamic range, specificity, and precision in a single visualization [22].

Analysis Methodologies for Validation Studies

Different analytical approaches can be employed to confirm high-throughput findings:

- Fold-Change Correlation: Compare expression fold changes between experimental conditions across platforms, with high-performing RNA-seq workflows showing Pearson correlations of R²=0.93-0.94 with qPCR data [23].

- Differential Expression Concordance: Assess the agreement in differentially expressed gene calls, recognizing that approximately 15% of genes may show inconsistent results between RNA-seq and qPCR [23].

- Troubleshooting Discrepancies: Investigate genes with inconsistent results for specific features—they tend to be smaller, have fewer exons, and lower expression compared to genes with consistent measurements [23].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of qPCR validation requires specific reagent systems optimized for different experimental needs:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | TRIzol/reagents, RNeasy Plus kits | RNA isolation with DNA elimination, optimized for different sample types [26] |

| Reverse Transcription | Oligo(dT) primers, random hexamers, gene-specific primers | cDNA synthesis with different priming strategies affecting transcript representation [25] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | PrimeTime Mini, Luna qPCR kits | Optimized reaction components for intercalating dyes or probe-based detection [25] [22] |

| Assay Systems | PrimeTime predesigned assays, ZEN Double Quenched Probes | Prequalified primers and probes with modifications enhancing signal-to-noise [25] |

| Quality Assessment | RiboGreen dye, Agilent Bioanalyzer | Precise RNA quantification and integrity assessment [25] [26] |

Within the comprehensive workflow of genomic discovery, qPCR maintains an indispensable role as a validation tool that bridges high-throughput screening and biological confirmation. While RNA-seq and other comprehensive platforms excel at hypothesis generation and transcriptome-wide exploration, qPCR provides the precise, targeted quantification necessary to verify critical findings before drawing biological conclusions. The most robust experimental approaches strategically leverage the complementary strengths of both technologies—using RNA-seq for unbiased discovery and qPCR for focused confirmation—therely maximizing both the breadth of discovery and confidence in results. This integrated approach ensures that genomic studies produce reliable, reproducible findings that can effectively advance scientific understanding and therapeutic development.

From Data to Assay: A Step-by-Step Protocol for qPCR Validation

In the field of gene expression analysis, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the capstone technology for comprehensive transcriptome profiling. However, real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) remains the gold standard for validating RNA-seq findings due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [29] [4]. This validation process is particularly crucial when RNA-seq data is based on a small number of biological replicates or when a second methodological confirmation is necessary for scientific publication [4]. The reliability of RT-qPCR results fundamentally depends on using appropriate reference genes—genes with highly stable expression across the biological conditions being studied [29]. Traditional selection methods often rely on supposedly stable "housekeeping" genes, but evidence shows these can be unpredictably modulated under different experimental conditions [29]. The Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) software addresses this critical bottleneck by providing a systematic, data-driven approach for selecting optimal reference and validation candidate genes directly from RNA-seq datasets.

What is GSV Software? Purpose and Development

GSV is a specialized software tool designed to identify the most stable reference genes and the most variable validation candidate genes from transcriptomic data for downstream RT-qPCR experiments [29] [30]. Developed by researchers at the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz using the Python programming language, GSV features a user-friendly graphical interface built with Tkinter, allowing entire analyses without command-line interaction [29] [30]. The tool accepts common file formats (.xlsx, .txt, .csv) containing transcript expression data, making it accessible to biologists and researchers without advanced bioinformatics training [29].

The software's algorithm implements a filtering-based methodology that uses Transcripts Per Million (TPM) values to compare gene expression across RNA-seq samples [29]. This approach was adapted from methodologies established by Yajuan Li et al. for systematic identification of reference genes in scallop transcriptomes [29]. A key innovation of GSV is its ability to filter out genes with stable but low expression, which might fall below the detection limit of RT-qPCR assays—a critical limitation of existing selection methods [29]. By ensuring selected genes have sufficient expression for reliable detection, GSV improves the accuracy and efficiency of the transcriptome validation process.

How GSV Works: Algorithm and Workflow

The GSV algorithm employs a sophisticated multi-step filtering process to identify optimal reference and validation genes based on their expression stability and level across samples. The workflow branches to select two distinct types of candidate genes: stable reference genes and variable validation genes.

Reference Gene Selection Criteria

For identifying reference genes, GSV applies five sequential filters to the TPM values from RNA-seq data [29]:

- Expression Presence: Genes must have TPM > 0 in all analyzed libraries [29].

- Low Variability: Standard deviation of Log₂(TPM) across samples must be < 1 [29].

- Expression Consistency: No exceptional expression in any library (|Log₂(TPM) - Average(Log₂(TPM))| < 2) [29].

- High Expression: Average Log₂(TPM) > 5 [29].

- Stability: Coefficient of variation < 0.2 [29].

Validation Gene Selection Criteria

For identifying variable genes suitable for validation of differential expression, GSV applies a different set of filters [29]:

- Expression Presence: TPM > 0 in all libraries [29].

- High Variability: Standard deviation of Log₂(TPM) > 1 [29].

- High Expression: Average Log₂(TPM) > 5 [29].

The following diagram illustrates GSV's complete logical workflow for candidate gene selection:

GSV Software Gene Selection Workflow

Tuning and Customization

Despite providing recommended standard cutoff values for optimal gene selection, GSV allows users to modify these thresholds through its software interface [29]. This flexibility enables researchers to loosen or tighten selection criteria based on specific experimental needs or particular characteristics of their transcriptomic data.

Performance Comparison: GSV vs. Alternative Tools

Comparative Advantages of GSV

When evaluated against other gene selection software using synthetic datasets, GSV demonstrated superior performance by effectively removing stable low-expression genes from the reference candidate list while simultaneously creating robust variable-expression validation lists [29]. The table below compares GSV's capabilities with other commonly used tools:

Table 1: Feature Comparison Between GSV and Alternative Gene Selection Tools

| Software Tool | Accepts RNA-seq Data | Filters Low-expression Genes | Selects Reference Genes | Selects Validation Genes | Command-line Interaction | Graphical Interface |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSV | Yes [29] | Yes [29] | Yes [29] | Yes [29] | No [29] | Yes [29] |

| GeNorm | Limited [29] | No [29] | Yes [29] | No [29] | No | Yes |

| NormFinder | Limited [29] | No [29] | Yes [29] | No [29] | Yes (R package) [29] | No |

| BestKeeper | Limited [29] | No [29] | Yes [29] | No [29] | No | Yes |

| OLIVER | Limited (microarrays) [29] | No [29] | Yes [29] | No [29] | Yes [29] | No |

Experimental Validation Data

GSV's performance has been validated through multiple experiments, including application to an Aedes aegypti transcriptome [29] [30]. In this case study, GSV identified eiF1A and eiF3j as the most stable reference genes, which were subsequently confirmed through RT-qPCR analysis [29]. The tool also revealed that traditional mosquito reference genes were less stable in the analyzed samples, highlighting the risk of inappropriate gene selection using conventional approaches [29].

The software has demonstrated scalability in processing large datasets, successfully analyzing a meta-transcriptome with over ninety thousand genes [29]. The quantitative results from performance testing are summarized below:

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of GSV Software

| Performance Metric | Synthetic Dataset Testing | Aedes aegypti Case Study | Meta-transcriptome Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Removal of low-expression stable genes | Effective [29] | Confirmed [29] | Successful [29] |

| Identification of stable references | Superior to alternatives [29] | eiF1A, eiF3j confirmed [29] | Scalable to >90,000 genes [29] |

| Creation of variable validation lists | Effective [29] | Available [29] | Successful [29] |

| Processing time and efficiency | Time-effective [29] | Time-effective [29] | Successful [29] |

Experimental Protocols for GSV Implementation

Step-by-Step GSV Workflow Protocol

- Data Preparation: Compile TPM (Transcripts Per Kilobase Million) values for all genes across all RNA-seq samples into a single file (.xlsx, .txt, or .csv format) [29].

- Software Setup: Download and install GSV from the official GitHub repository (https://github.com/rdmesquita/GSV) [30].

- Parameter Configuration: Input TPM data file and set filtering criteria (standard values recommended: TPM>0, SD<1, |Log2TPM-Mean|<2, Mean>5, CV<0.2 for reference genes) [29].

- Execution: Run analysis through the graphical interface without command-line interaction [29].

- Result Interpretation: Review output tables listing reference candidates (most stable) and validation candidates (most variable) [29].

- Experimental Validation: Select top candidate reference genes for stability confirmation via RT-qPCR using different biological samples [29].

Case Study: Aedes aegypti Transcriptome Analysis

Researchers applied GSV to an Aedes aegypti transcriptome to identify reference genes for studying development and insecticide resistance [29]. The traditional reference genes (e.g., ribosomal proteins) were found to be less stable compared to eiF1A and eiF3j identified by GSV [29]. RT-qPCR validation confirmed the superior stability of GSV-selected genes across different biological conditions, demonstrating the practical utility of the software in real research scenarios [29].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials required for implementing the complete RNA-seq to RT-qPCR validation workflow supported by GSV software:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for RNA-seq Validation Workflow

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Stage |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality RNA from biological samples | Sample Preparation |

| RNA-seq Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries (strand-specific, barcoded) | RNA-seq |

| TPM Quantification Software | Generate transcripts per million values from sequence reads | Data Processing |

| GSV Software | Selection of optimal reference and validation candidate genes | Gene Selection |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesis of cDNA from RNA templates for qPCR | RT-qPCR |

| qPCR Master Mix | Amplification and detection of specific transcripts | RT-qPCR |

| Primer Sets | Gene-specific amplification of target and reference genes | RT-qPCR |

GSV represents a significant advancement in the field of gene expression analysis by providing a systematic, data-driven approach for selecting reference and validation genes from RNA-seq data. By filtering for both stability and adequate expression levels, GSV addresses a critical limitation of traditional methods that often rely on presumptive housekeeping genes without empirical validation [29]. The software's ability to process large datasets efficiently, combined with its user-friendly interface, makes it a valuable tool for researchers validating RNA-seq results through RT-qPCR [29] [30]. As transcriptomic studies continue to expand across diverse biological fields, tools like GSV that enhance the accuracy and reliability of gene expression validation will play an increasingly important role in ensuring robust and reproducible research outcomes.

In the framework of validating RNA-Seq results with qPCR experimental methods, the selection of appropriate genes is a cornerstone for accurate data interpretation. While RNA-Seq provides an unbiased, genome-wide view of the transcriptome, quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains the gold standard for validating specific gene expression changes due to its high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [29] [31]. The reliability of qPCR data, however, hinges on proper normalization using reference genes that demonstrate stable expression across all experimental conditions [6] [32]. The misuse of traditional housekeeping genes without proper validation remains a prevalent issue that can compromise data integrity and lead to biological misinterpretations [29] [32].

The emergence of Transcripts Per Million (TPM) as a standardized unit for RNA-Seq quantification has provided researchers with a robust starting point for identifying candidate genes [33]. TPM values account for both sequencing depth and gene length, enabling more accurate cross-sample comparisons than raw counts alone [33]. This article systematically compares computational approaches for selecting stable reference and variable candidate genes directly from TPM data, providing researchers with evidence-based protocols for strengthening the connection between high-throughput discovery and targeted validation.

Understanding TPM Data and Its Applications in Gene Selection

TPM as a Quantification Measure

TPM (Transcripts Per Million) represents a normalized expression unit that facilitates comparison of transcript abundance both within and between samples. The calculation involves two sequential normalizations: first for gene length, then for sequencing depth. This dual normalization makes TPM particularly valuable for cross-sample comparisons, as the sum of all TPM values in each sample is always constant (1 million), creating a consistent scale across libraries [33]. This property is especially important when selecting reference genes, as it minimizes technical variability that could obscure true biological stability.

Compared to other quantification units, TPM provides distinct advantages. While FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped fragments) applies similar normalizations, it lacks the consistent per-million sum across samples. Normalized counts from tools like DESeq2 effectively handle cross-sample comparison for differential expression but don't intrinsically account for gene length variations [33]. Research comparing quantification measures has demonstrated that TPM offers a balanced approach for initial candidate gene screening from RNA-Seq datasets, though some studies suggest normalized counts may provide slightly better reproducibility in certain contexts [33].

The Critical Distinction Between Reference and Variable Genes

In transcriptomics validation workflows, researchers must identify two distinct classes of genes with opposing expression characteristics:

- Stable Reference Genes: These maintain consistent expression levels across experimental conditions, serving as internal controls for qPCR normalization. They control for technical variations in RNA quality, reverse transcription efficiency, and cDNA loading [6] [32].

- Variable Candidate Genes: These demonstrate significant expression changes between conditions and represent primary targets for biological interpretation and validation. They typically show strong responsiveness to experimental manipulations or disease states [29].

Proper selection of both gene classes is essential for robust validation. Reference genes ensure technical accuracy, while appropriately chosen variable genes confirm biological hypotheses. The MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines emphasize that reference gene utility must be experimentally validated for specific tissues, cell types, and experimental designs rather than assumed from historical precedent [32].

Computational Methods for Selecting Genes from TPM Data

The GSV Software Workflow

The Gene Selector for Validation (GSV) software provides a specialized tool for identifying both stable reference and variable candidate genes directly from TPM data [29]. Developed in 2024, this Python-based application implements a filtering-based methodology adapted from Li et al. that systematically processes transcriptome quantification tables to identify optimal candidates [29].

The software's algorithm employs distinct criteria for reference versus variable gene selection. For reference genes, GSV applies five sequential filters requiring that genes must: (I) have expression >0 in all libraries; (II) demonstrate low variability between libraries (standard deviation of log₂(TPM) <1); (III) show no exceptional expression in any library (expression at most twice the average of log₂ expression); (IV) maintain high expression levels (average log₂(TPM) >5); and (V) exhibit low coefficient of variation (<0.2) [29]. For variable genes, GSV uses modified criteria that prioritize high variability (standard deviation of log₂(TPM) >1) while maintaining detectable expression [29].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete GSV filtering process:

Figure 1: GSV Software Filtering Workflow for Gene Selection

Alternative Statistical Approaches

Beyond dedicated software tools, researchers can implement statistical methods directly to identify candidate genes from TPM data. The coefficient of variation (CV) provides a straightforward metric for assessing gene stability, calculated as the standard deviation divided by the mean of TPM values across samples [6] [33]. Genes with lower CV values represent stronger reference candidates, while those with higher CV values are potential variable genes.

More sophisticated algorithms include NormFinder, which estimates expression variation using analysis of variance models, and GeNorm, which evaluates gene stability through pairwise comparisons [6] [32]. A comprehensive comparison of statistical approaches published in 2022 demonstrated that with a robust statistical workflow, conventional reference gene candidates can perform as effectively as genes preselected from RNA-Seq data [6]. This finding suggests that methodological rigor in statistical validation may outweigh the source of candidate genes.

A particularly innovative approach published in 2024 demonstrated that a stable combination of non-stable genes can outperform individual reference genes for qPCR normalization [32]. This method identifies a fixed number of genes whose individual expressions balance each other across experimental conditions, creating a composite reference with superior stability compared to single genes [32].

Comparison of Computational Methods

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Gene Selection Methods from TPM Data

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSV Software | Automated filtering based on TPM thresholds; identifies both reference and variable genes [29] | User-friendly interface; standardized criteria; efficient processing of large datasets | Limited customization options; fixed expression thresholds | High-throughput screening; researchers with limited bioinformatics expertise |

| Coefficient of Variation | Simple calculation of variation relative to mean expression [6] | Easy to implement; intuitive interpretation; works with any statistical software | Does not account for expression level; sensitive to outliers | Initial screening; small datasets; preliminary candidate identification |

| GeNorm | Pairwise comparison of candidate genes; determines optimal number of reference genes [32] | Established validation method; determines minimal number of required genes | Requires predefined candidate set; not for initial screening from TPM data | Final validation of candidate reference genes |

| NormFinder | Model-based approach considering intra- and inter-group variation [6] [32] | Accounts for sample subgroups; robust against co-regulated genes | Requires predefined candidate set; more complex implementation | Experimental designs with distinct sample groups or treatments |

| Gene Combination Method | Identifies optimal combinations of genes that balance each other's expression [32] | Can outperform single-gene normalizers; creates composite reference standards | Computationally intensive; requires large TPM dataset for discovery | Maximizing normalization accuracy; organisms with comprehensive transcriptome databases |

Experimental Protocols for Gene Validation

From TPM Selection to qPCR Validation

The transition from computational selection to experimental validation requires careful experimental design. For reference gene validation, researchers should select 3-5 top candidate stable genes from TPM analysis plus 1-2 traditionally used reference genes for comparison [32]. These candidates are then measured by qPCR across all experimental conditions, with multiple biological replicates that reflect the full scope of the study design.

The validation process typically employs statistical algorithms like GeNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper to rank candidate stability based on qPCR data [32]. These tools evaluate expression consistency and help determine the optimal number of reference genes required for accurate normalization. Studies consistently show that using multiple reference genes significantly improves normalization accuracy compared to single-gene approaches [32].

For variable genes, selected candidates should represent a range of effect sizes and biological functions. Including both strongly and moderately differentially expressed genes from TPM data helps assess the sensitivity of validation across expression magnitudes. This approach also controls for potential biases in RNA-Seq quantification of lowly expressed genes [6].

qPCR Experimental Design and Execution

The following workflow illustrates the complete experimental pipeline from computational selection to final validation:

Figure 2: Complete Workflow from TPM Analysis to qPCR Validation

Troubleshooting Common Validation Issues

When discordance appears between RNA-Seq and qPCR results, researchers should investigate several potential sources. Genes with shorter transcript lengths and lower expression levels frequently show poorer correlation between platforms due to technical limitations of both methods [6]. RNA-Seq normalization strategies can exhibit transcript-length bias where longer transcripts receive more counts regardless of actual expression levels [6].

For reference genes that demonstrate unexpected variability during qPCR validation, consider experimental factors beyond transcriptional regulation. RNA integrity, reverse transcription efficiency, and primer specificity can all contribute to measured variation. Including RNA quality assessment (e.g., RIN scores) and cDNA quality controls strengthens validation conclusions [34].

When validation fails for variable genes, examine the statistical power of both original RNA-Seq and validation experiments. Small sample sizes in RNA-Seq studies increase false positive rates, necessitating more stringent significance thresholds or additional replication in qPCR validation [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Expression Validation

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Gene Validation Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Selection Criteria | Quality Control Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | Extract high-quality RNA from samples | Compatibility with sample type (cells, tissues, FFPE); yield and purity guarantees | RNA integrity number (RIN) >8.0; clear 260/280 and 260/230 ratios [34] |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | Convert RNA to cDNA for qPCR | High efficiency; minimal bias; ability to process difficult templates | Include genomic DNA removal; verify efficiency with spike-in controls |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Enable quantitative amplification | Efficiency, sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility across targets | Validate with standard curves; ensure efficiency between 90-110% |

| Primer Sets | Gene-specific amplification | High specificity; minimal secondary structure; appropriate amplicon size (70-150 bp) | Verify single amplification product with melt curve analysis [32] |

| Reference Gene Panels | Pre-validated normalization genes | Evidence of stability in similar biological systems; include multiple genes | Confirm stability in your specific experimental system [32] |

| RNA-Seq Quantification Tools | Generate TPM values from raw sequencing data | Accuracy, reproducibility, compatibility with reference annotations | Use standardized pipelines; verify with spike-in controls when available [33] |

| Stability Analysis Software | Evaluate candidate reference genes (GeNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper) | Established validation record; transparent algorithms; appropriate for experimental design | Apply multiple complementary methods for consensus [32] |

The integration of TPM-based computational selection with rigorous qPCR validation represents a powerful framework for transcriptomics research. Through comparative analysis of current methodologies, several best practices emerge. First, leverage TPM data from RNA-Seq as a valuable resource for identifying candidate genes, but always confirm computational predictions with experimental validation. Second, implement multiple statistical approaches rather than relying on a single method, as each offers complementary insights into gene stability. Third, recognize that context matters—the ideal reference genes for one experimental system may perform poorly in another.

The evolving consensus suggests that future directions will focus increasingly on combinatorial approaches rather than single-gene normalizers [32]. As transcriptomic databases expand across diverse biological contexts, researchers will gain unprecedented power to identify optimal gene sets for specific experimental paradigms. By adhering to the rigorous criteria and methodologies outlined in this guide, researchers can maximize the accuracy and reproducibility of their gene expression studies, strengthening the vital connection between high-throughput discovery and targeted validation.

In the rigorous pipeline of validating RNA-Seq results with qPCR, primer design transcends a mere preliminary step to become a fundamental determinant of experimental success. The central challenge in this process involves designing oligonucleotides that achieve perfect specificity when distinguishing between nearly identical sequences—whether differentiating between homologous gene family members or accurately genotyping single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The exponential growth of cataloged genetic variations, with the human genome now containing a SNP approximately every 22 bases, has dramatically intensified this challenge [35]. In diagnostic assays, drug development, and functional genomics research, the failure to account for these factors can produce misleading validation data, compromising downstream conclusions and applications.

This guide provides a systematic comparison of strategies and tools for designing primers that effectively incorporate homologous sequences and manage SNPs. We present supporting experimental data and detailed methodologies to equip researchers with protocols that enhance specificity, ensuring that qPCR validation of RNA-Seq experiments yields biologically accurate and reproducible results.

Understanding the Specificity Challenge

The Impact of SNPs on Primer Binding and Amplification Efficiency

Single nucleotide polymorphisms underlying primer or probe binding sites can destabilize oligonucleotide binding and reduce target specificity through several mechanisms. The positional effect of a mismatch is paramount: SNPs located in the interior of a primer-template duplex are most disruptive, potentially reducing the melting temperature (Tm) by as much as 5–18°C [35]. This destabilization directly impacts qPCR amplification efficiency, particularly when mismatches occur within the last five bases of the primer's 3' end. Experimental data demonstrates that terminal 3' mismatches can alter quantification cycle (Cq) values by as much as 5–7 cycles—equivalent to a 32- to 128-fold difference in apparent template concentration depending on the master mix used [35].

The base composition of the mismatch further influences its impact. Reactions containing purine/purine (e.g., A/G) and pyrimidine/pyrimidine (e.g., C/C) mismatches at the 3' terminal position produce the largest Cq value differences compared to perfect matches [35]. When using primers for SNP detection in genotyping experiments, the strategic introduction of additional mismatches at the penultimate position (N-2) can increase specificity by further destabilizing amplification of the non-target allele [36].

Table 1: Impact of Mismatch Position on qPCR Amplification Efficiency

| Mismatch Position from 3' End | Expected ΔCq Value | Effect on Amplification Efficiency | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terminal (N-1) | +5 to +7 cycles | Severe reduction (32-128 fold) | Avoid in design |

| Penultimate (N-2) | +3 to +5 cycles | Significant reduction | Avoid in design |

| Within last 5 bases | +1 to +3 cycles | Moderate reduction | Avoid if possible |

| Central region (>5 bases from end) | 0 to +2 cycles | Mild reduction | Potentially acceptable |

| 5' end | Minimal effect | Negligible reduction | Generally acceptable |

Homologous Gene Families and Sequence Conservation

Beyond SNPs, homologous gene families present a distinct challenge for primer design. These families contain conserved regions that can serve as potential off-target binding sites, leading to co-amplification of related gene members and compromising quantification accuracy. This problem is particularly acute when designing primers for qPCR validation of RNA-Seq data, where distinguishing between paralogous transcripts with high sequence similarity is often necessary.

The risk extends to pseudogenes—non-functional genomic sequences homologous to functional genes—which can be co-amplified if primers bind to shared conserved regions. Research indicates that approximately 20% of spliced human genes lack at least one constitutive intron, further complicating the design of transcript-specific assays [37]. Effective strategies to address these challenges include targeting alternative splicing junctions, exploiting unique 3' untranslated regions (UTRs), or focusing on exonic sequences that flank long intronic regions not present in mature mRNA or processed pseudogenes.

Comparative Analysis of Primer Design Strategies

SNP-Informed Design Approaches

Avoidance Strategy: The most straightforward approach involves designing primers that avoid known SNP positions entirely. This requires up-to-date knowledge of variation databases such as NCBI dbSNP. Before finalizing designs, researchers should visually inspect their target region using NCBI's BLAST Graphical interface with the "Variation" track enabled to identify documented polymorphisms [35]. The minor allele frequency (MAF) should be considered relative to the study population, as low-frequency SNPs may not warrant design modification in homogeneous populations.

Incorporation Strategy: When avoiding a SNP is impossible due to sequence constraints, strategic incorporation becomes necessary. For genotyping experiments where relevant SNPs occur adjacent to the SNP of interest, using mixed bases (Ns) or inosines in the primer or probe can cover adjacent sites [35]. When a SNP must underlie a primer sequence, positional management becomes critical—positioning the SNP toward the 5' end of the primer minimizes its impact on polymerase extension efficiency [35]. Tools like IDT's OligoAnalyzer enable researchers to predict the Tm of mismatched probe sequences, allowing for informed design decisions [35].

Amplification Refractory Mutation System (ARMS): For applications requiring active discrimination between alleles, the ARMS approach employs primers whose 3' terminal nucleotide is complementary to either the wild-type or mutant sequence. The efficiency of amplification is dramatically reduced when a mismatch occurs at the 3' end. Enhanced specificity can be achieved by introducing an additional deliberate mismatch at the N-2 or N-3 position, which further destabilizes the non-target allele [36]. Experimental data indicates that optimal destabilization varies by mismatch type, with G/A, C/T, and T/T mismatches providing the strongest discriminatory effect [36].

Table 2: SNP-Specific Primer Design Solutions Comparison

| Design Strategy | Best Use Case | Specificity Mechanism | Limitations | Experimental Validation Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP Avoidance | High-frequency SNPs in study population | Eliminates mismatch destabilization | Limited by target sequence flexibility | Moderate |

| 5' Positioning | Unavoidable SNPs in primer binding site | Minimizes polymerase binding disruption | Reduced but not eliminated SNP effects | Moderate |

| Mixed Bases/Inosines | Flanking SNPs adjacent to target site | Accommodates sequence variation | Potential reduction in overall binding affinity | High |

| ARMS Primers | Active allele discrimination | 3' terminal mismatch blocks extension | Requires precise optimization | High |

| Modified ARMS (N-2) | Enhanced allele discrimination needed | Additional mismatch increases specificity | More complex design process | High |

Strategies for Managing Homologous Sequences

Constitutive Exon Targeting: For gene-level expression analysis that aims to be blind to alternative splicing, targeting constitutive exons—those present in all transcript variants—provides an effective strategy. This approach involves identifying introns present in every isoform and designing primers within the flanking exonic segments [37]. Such designs ensure that the expression readout reflects overall gene expression rather than being influenced by drug effects that might alter isoform proportions without changing primary mRNA expression levels.