Ab Initio Protein Structure Prediction: From Physical Principles to AI-Driven Breakthroughs in Biomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of ab initio protein structure prediction, a computational approach that determines 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences based solely on physical principles, without...

Ab Initio Protein Structure Prediction: From Physical Principles to AI-Driven Breakthroughs in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of ab initio protein structure prediction, a computational approach that determines 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences based solely on physical principles, without relying on structural templates. We explore the foundational concepts underpinning these methods, including the thermodynamic hypothesis and the Levinthal paradox. The review systematically compares the evolution of algorithmic strategies, from early physics-based models to modern deep learning architectures like AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold, assessing their accuracy, limitations, and runtime performance. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses persistent challenges, such as predicting orphan proteins, dynamic regions, and membrane proteins. Finally, we outline rigorous validation frameworks, including CASP benchmarks and molecular dynamics simulations, and discuss the transformative impact of reliable ab initio prediction on drug discovery and the interpretation of disease-causing genetic variants.

The Foundations of Protein Folding: From Anfinsen's Dogma to the Levinthal Paradox

Ab initio protein structure prediction refers to computational methods that predict a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence alone, without relying on explicit structural templates from known homologs [1] [2]. The term "ab initio" (Latin for "from the beginning") underscores the foundational principle of these methods: they aim to solve the protein folding problem using only physicochemical principles and the information encoded in the primary sequence [1]. This approach stands in contrast to template-based modeling, which depends on detectable evolutionary relationships to proteins of known structure. The core hypothesis, derived from Anfinsen's thermodynamic hypothesis, posits that the native functional structure of a protein resides at the global minimum of its free energy landscape [3] [4]. Achieving accurate ab initio prediction represents a fundamental challenge in structural biology and computational biology, with significant implications for understanding disease mechanisms and accelerating drug discovery, particularly for proteins lacking homologous structures [3].

Core Principles and the Energy Landscape

The conceptual framework for ab initio prediction treats protein folding as a complex optimization problem [1]. The objective is, given a primary structure, to identify the tertiary structure with the minimum potential energy [1]. This process can be visualized as a search across a vast conformational landscape.

The Optimization Problem

The search space encompasses all possible spatial conformations of a polypeptide chain. Each point in this space represents a specific conformation characterized by an associated potential energy, computed using scoring functions or force fields based on the physicochemical properties of amino acids [1] [2]. The algorithm's goal is to navigate this landscape to locate the conformation with the lowest possible energy, which corresponds to the native state [1]. This is analogous to finding the lowest point in a topographical map where the elevation represents energy [1].

The Challenge of Local Minima

The energy landscape is not smooth but is typically rugged and fraught with numerous local minima—conformations that are stable against small perturbations but do not represent the global minimum [1]. This ruggedness poses a major challenge for search algorithms, which can become trapped in these local energy valleys. As noted in one resource, "an object in a search space that has a smaller value of the optimization function than neighboring points is called a local minimum... we are seeking the lowest valley over the entire landscape, called a global minimum" [1]. This problem is exacerbated by the immense size of the conformational space, a consequence of Levinthal's paradox, which notes that proteins cannot find their native state by a random search of all possible conformations [1].

Strategies for Effective Search

To overcome the challenge of local minima, modern ab initio methods employ sophisticated strategies:

- Multiple Starting Conformations: Running the algorithm from numerous, diverse starting points to sample different regions of the landscape [1].

- Exploratory Algorithms: Incorporating techniques like Replica-Exchange Monte Carlo (REMC) that allow the search to "bounce" out of local minima with a certain probability, thus exploring a broader area of the conformational space [1] [5].

- Smoothing the Landscape: The integration of abundant, accurately-predicted spatial restraints, such as inter-residue distances and orientations, has been shown to smooth the rough energy landscape, making the global minimum more accessible to search algorithms [6] [7].

Evolution of Methodologies and Algorithms

Ab initio protein structure prediction has evolved significantly, driven by advances in force fields, sampling techniques, and the recent integration of deep learning.

Traditional Fragment Assembly and Physical Potentials

Early and enduring methods often rely on fragment assembly and knowledge-based or physics-based potentials. Programs like Rosetta and QUARK operate by assembling structural fragments extracted from a database of known structures, guided by a force field that evaluates the quality of the emerging structure [8] [5]. These methods typically employ stochastic search algorithms like Monte Carlo simulations to navigate the conformational space [3]. While powerful, these approaches can be computationally intensive, especially for larger proteins, because they require extensive sampling to find near-native conformations [6] [7].

The Deep Learning Revolution

A paradigm shift has been catalyzed by deep learning, which has dramatically improved both the accuracy and speed of ab initio prediction [6] [7]. Modern pipelines leverage deep residual neural networks (ResNets) to predict spatial restraints directly from sequence and evolutionary information.

These deep learning systems, such as DeepPotential, analyze Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) to predict a comprehensive set of geometric restraints, including:

- Distance Maps: Specifying distances between residue pairs, providing more precise information than binary contact maps [6] [7].

- Contact Maps: Indicating which residue pairs are in spatial proximity [5].

- Inter-residue Orientations: Defining the dihedral angles between residues, which are critical for accurate backbone construction [6].

- Hydrogen-Bonding Networks: Providing specific constraints for secondary structure formation and stability [9].

The abundance of these high-accuracy restraints (on the order of ~93 per protein residue) effectively smooths the energy landscape, reducing its roughness and funneling the search toward the native state [6] [7]. This has enabled a move from slow, fragment-based sampling to faster gradient-descent optimization methods like L-BFGS, which can rapidly minimize a structure to satisfy the predicted restraints [6] [7]. For example, the DeepFold pipeline demonstrated folding simulations that were 262 times faster than traditional fragment assembly methods while achieving higher accuracy [6].

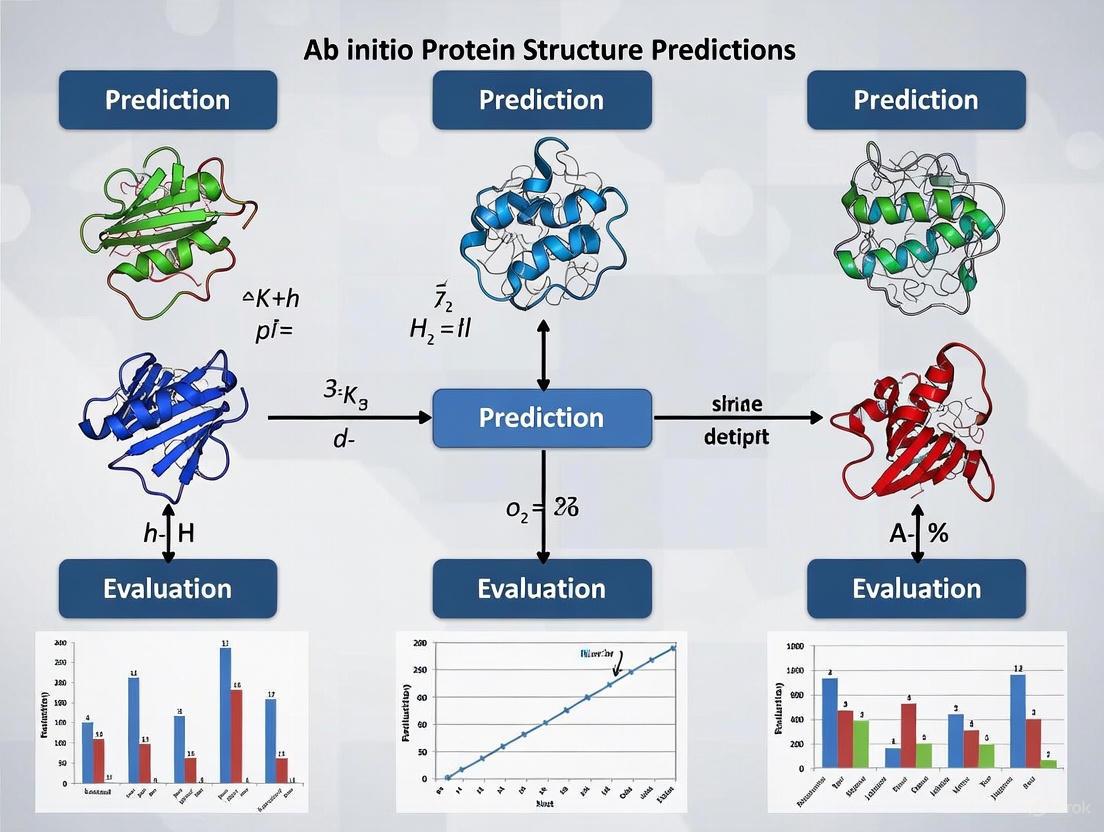

Diagram of a modern deep learning-based ab initio prediction workflow, illustrating the integration of sequence analysis, restraint prediction, and structure optimization.

Quantitative Assessment of Method Performance

The progress in ab initio prediction is quantitatively assessed through community-wide blind trials like the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments and benchmarking on standardized datasets. Performance is typically measured using metrics such as TM-score (a metric for topological similarity, where >0.5 indicates a correct fold) and Global Distance Test (GDT_TS) (a measure of atomic accuracy) [6] [5].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Ab Initio Prediction Methods on Non-Redundant Test Sets

| Method | Type | Average TM-score | Proteins Correctly Folded (TM-score ≥0.5) | Relative Speed | Key Restraints Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepFold | Deep Learning + Gradient-Descent | 0.751 | 92.3% (204/221) | 262x faster | Distances, Orientations, Contacts [6] |

| C-QUARK | Contact-Guided Fragment Assembly | 0.606 (First Model) | 75% (186/247) | - | Contact Maps [5] |

| QUARK | Fragment Assembly | 0.423 (First Model) | 29% (71/247) | 1x (Baseline) | Knowledge-based Force Field [5] |

| Baseline (GE only) | Knowledge-based Force Field | 0.184 | 0% (0/221) | - | General Physical Energy [6] |

The data reveal the transformative impact of deep learning. DeepFold's integration of multiple precise restraints yields a dramatic improvement in both accuracy and computational efficiency. The table also highlights the specific contribution of different restraint types: adding distance restraints alone increased the average TM-score by 157.4% over a baseline force field, and further inclusion of orientation restraints pushed the average TM-score to 0.751 [6]. Furthermore, C-QUARK demonstrates that even lower-accuracy contact maps, when intelligently integrated, can massively boost the performance of traditional fragment assembly, correctly folding 6 times more proteins than other contact-based methods in challenging cases with sparse evolutionary data [5].

Table 2: Impact of Restraint Type on Prediction Accuracy (DeepFold Benchmark) [6]

| Restraint Type | Average TM-score | Percentage of Targets Correctly Folded |

|---|---|---|

| General Physical Energy (Baseline) | 0.184 | 0.0% |

| + Cα and Cβ Contact Restraints | 0.263 | 1.8% |

| + Cα and Cβ Distance Restraints | 0.677 | 76.0% |

| + All Restraints (Including Orientations) | 0.751 | 92.3% |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a practical guide for researchers, this section outlines standard protocols for ab initio structure prediction using modern methods.

Deep Learning Restraint Prediction and Folding

This protocol is based on the DeepFold pipeline described by Pearce et al. [6] [7].

- Input Preparation: Provide the amino acid sequence of the target protein in standard one-letter code.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Generation: Use a tool like DeepMSA2 to search the query sequence against multiple whole-genome and metagenomic sequence databases. This step constructs a deep MSA, which is critical for capturing co-evolutionary signals.

- Spatial Restraint Prediction: Input the resulting MSA into a deep learning model, such as DeepPotential, which uses a deep ResNet architecture. The model will output probability distributions for:

- Cβ-Cβ/Cα-Cα distance maps (converted to continuous distances).

- Inter-residue orientation restraints (dihedral angles).

- A hydrogen-bonding potential defined by C-alpha atom coordinates [9].

- Energy Function Construction: Convert the predicted spatial restraints into a deep learning-based potential. This potential is combined with a general knowledge-based statistical force field to create a composite energy function.

- Structure Optimization (Folding): Initialize a random or extended polypeptide chain. Use a gradient-based optimization algorithm, specifically L-BFGS, to minimize the composite energy function. The algorithm will iteratively adjust the atomic coordinates of the protein model to satisfy the ensemble of predicted spatial restraints and the physical force field.

- Model Selection: The final output of the L-BFGS simulation is the full-length atomic model. For robustness, the process can be repeated from different initializations, and the resulting models can be clustered to select a final representative model.

Contact-Guided Fragment Assembly (C-QUARK)

This protocol details the methodology for integrating contact maps into fragment assembly simulations, as proven effective by C-QUARK [5].

- Input and MSA: Start with the target amino acid sequence and generate an MSA, as in the previous protocol.

- Contact-Map Prediction: Generate multiple contact-maps using both deep-learning and co-evolution-based predictors (e.g., DCA methods).

- Fragment Library Generation: Assemble a library of short (1-20 residues) structural fragments from the PDB. These fragments are selected based on local sequence similarity and predicted secondary structure, providing building blocks with realistic local geometries.

- Replica-Exchange Monte Carlo (REMC) Simulation: Assemble full-length models through REMC simulations. This technique runs multiple parallel simulations ("replicas") at different temperatures, allowing periodic exchanges of conformations between them. This facilitates escape from local minima and a more thorough exploration of the conformational space.

- Energy Function Guidance: The simulation is guided by a hybrid energy function that combines:

- Knowledge-based terms from QUARK.

- A 3-gradient (3G) contact potential that smoothly incorporates the predicted short-, medium-, and long-range contact restraints.

- Contact information derived from the structure fragments themselves.

- Decoy Clustering and Selection: After generating a large ensemble of decoy structures, use a clustering algorithm like SPICKER to identify the largest and most structurally consistent clusters. The center of the largest cluster is selected as the final predicted model.

Table 3: Key Software and Data Resources for Ab Initio Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Ab Initio Prediction | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepMSA2 | Software Tool | Generates deep multiple sequence alignments from genomic and metagenomic databases, providing essential co-evolutionary input features. [6] [7] | Standalone/Web Server |

| DeepPotential | Deep Learning Model | A multi-task ResNet that predicts spatial restraints (distances, orientations, H-bonds) from MSAs. [6] [9] | Standalone/Web Server |

| QUARK/C-QUARK | Folding Pipeline | Performs fragment assembly using Replica-Exchange Monte Carlo simulations, guided by knowledge-based and contact-derived energy functions. [1] [5] | Standalone/Web Server |

| Rosetta | Software Suite | Provides ab initio protocols for fragment assembly and full-atom refinement using Monte Carlo annealing and knowledge-based force fields. [3] [5] | Standalone |

| L-BFGS Optimizer | Algorithm | A gradient-based optimization algorithm used in pipelines like DeepFold for rapid energy minimization against deep learning potentials. [6] [7] | Library within Code |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Source for experimental protein structures used for training deep learning models and extracting fragment libraries. [3] [5] | Public Database |

| SCOPe Database | Database | A curated database of protein structural domains used for benchmarking and testing prediction methods. [6] | Public Database |

Applications in Structural Biology and Drug Development

The ability to predict protein structures reliably from sequence alone has profound implications for biomedical research.

- Functional Annotation of Genomes: Low-resolution ab initio models can be sufficient to infer protein function on a genomic scale, even in the absence of homologous templates, bridging the gap between sequence and function [3] [8].

- Target Identification and Validation in Drug Discovery: For proteins implicated in diseases but with no experimentally solved structure (e.g., many membrane proteins), ab initio models provide a crucial starting point for structure-based drug design [3]. This allows for virtual screening and the identification of potential inhibitor compounds.

- Understanding Misfolding Diseases: Ab initio methods, combined with molecular dynamics, are being used to study the misfolded conformations of proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. For instance, AlphaFold2 has been used to identify β-strand segments in α-synuclein that are involved in pathogenic amyloid fibril formation [4].

- Modeling Protein-Protein Interactions: Accurate models of individual proteins enable the prediction of interaction interfaces and the assembly of complexes, which is vital for understanding signaling pathways and other cellular processes [3].

Ab initio protein structure prediction has matured from a purely theoretical challenge into a powerful, practical tool for structural biology. The field's progress has been driven by a refined understanding of the protein folding energy landscape and the development of sophisticated algorithms to navigate it. The recent integration of deep learning has been a watershed moment, enabling the accurate prediction of spatial restraints that smooth the energy landscape and permit highly efficient structure optimization. While challenges remain—particularly for very large proteins and those with complex multi-domain architectures—modern methods like DeepFold and C-QUARK can now routinely generate correct folds for the majority of single-domain proteins. As these methods become more accessible and are further integrated with experimental data from techniques like cryo-EM, their role in accelerating biological discovery and therapeutic development is poised to expand dramatically.

The Protein Folding Problem and the Thermodynamic Hypothesis

The protein folding problem stands as a fundamental challenge in molecular biology, concerning the process by which a linear amino acid chain folds into a unique, functional three-dimensional structure. At its heart lies the thermodynamic hypothesis, famously articulated by Christian B. Anfinsen, which posits that a protein's native conformation represents the state of minimum free energy for its specific amino acid sequence under physiological conditions [10]. This principle implies that all information required for folding is encoded within the protein's primary structure. For several decades, validating this hypothesis and predicting structure from sequence alone represented one of science's most elusive challenges. This whitepaper examines the classical thermodynamic framework, explores modern experimental methodologies for its validation, and evaluates the revolutionary impact of ab initio structure prediction tools like AlphaFold within this context, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a technical foundation for assessing advances in the field.

The Thermodynamic Hypothesis: Anfinsen's Dogma

Anfinsen's dogma, derived from seminal experiments with ribonuclease A, established three core requirements for a unique native protein structure to be attained [10]:

- Uniqueness: The sequence must not possess any alternative configurations with comparable free energy. The global free energy minimum must be unequivocal.

- Stability: The native state must be robust to minor environmental fluctuations. The free energy landscape should resemble a steep funnel, providing resistance to deformation.

- Kinetical Accessibility: The folding pathway from the unfolded to the folded state must be sufficiently smooth and not involve overly complex conformational rearrangements that would kinetically trap the molecule.

While the thermodynamic hypothesis provides a powerful foundational principle, subsequent research has revealed biological complexities not fully captured by the original formulation. Chaperone proteins assist in the folding of many proteins, primarily by preventing aggregation during the process rather than altering the final energetically favored state [10]. Furthermore, certain proteins exhibit behaviors that constitute exceptions to the dogma. Prion proteins and those involved in amyloid diseases like Alzheimer's can adopt stable, alternative conformations that lead to pathological aggregation [10]. Additionally, an estimated 0.5–4% of proteins in the Protein Data Bank are now believed to be "fold-switching" proteins, capable of adopting distinct native folds in response to cellular signals or environmental changes [10].

Experimental Validation and Quantitative Measurement of Folding

Experimental biophysics provides the critical link between the theoretical thermodynamic hypothesis and empirical observation. The measurement of folding stability and kinetics allows researchers to quantify the energetic landscape implied by Anfinsen's dogma.

Standardized Experimental Conditions

To enable meaningful comparison of folding data across different proteins and laboratories, the field has moved toward establishing consensus experimental conditions. A benchmark set of conditions has been proposed, including [11]:

- Temperature: 25°C is strongly recommended as a standard reference temperature. Folding rates typically exhibit temperature sensitivity of 1.5–3% per degree Celsius due to activation enthalpies of 10–20 kJ/mol [11].

- Denaturants: Urea is preferred over guanidinium salts for denaturation studies, as linear extrapolation is generally more applicable and ionic strength effects are minimized [11].

- Solvent Conditions: A buffer at pH 7.0 (e.g., 50 mM phosphate or 50 mM HEPES) with no added salt beyond the buffer components is recommended to mimic physiological conditions while maintaining experimental simplicity [11].

Key Experimental Parameters and Data Reporting

For proteins exhibiting two-state folding behavior (lacking stable intermediates), the folding process is characterized by several key parameters, which should be prominently reported alongside raw kinetic data [11]:

- Chevron Plots: These diagrams plot the logarithm of the observed rate constant (lnkobs*) against denaturant concentration, typically producing a V-shaped curve.

- m-values: The m-value represents the derivative of the natural logarithm of the folding or unfolding rate constant with respect to denaturant concentration (in units of kJ/mol/M). It reflects the change in solvent-accessible surface area during the folding/unfolding process [11].

- Linear Extrapolation: For phases with linear chevron arms, the folding and unfolding rates in water (zero denaturant) are estimated via linear extrapolation.

For systems displaying non-linear chevron plots ("rollover"), which may indicate intermediate states, transition-state movement, or aggregation, it is recommended to report both polynomial extrapolations and linear fits of the linear regions, along with the raw kinetic data for future re-analysis [11].

High-Throughput Methodologies: cDNA Display Proteolysis

Recent advances have enabled mega-scale experimental analysis of protein folding stability. The cDNA display proteolysis method represents a transformative approach, allowing for the measurement of thermodynamic folding stability for up to 900,000 protein domains in a single experiment [12].

Table 1: Key Components of cDNA Display Proteolysis Workflow

| Component | Function |

|---|---|

| DNA Library | Synthetic oligonucleotides encoding test protein variants. |

| Cell-free cDNA Display | In vitro transcription/translation system producing protein–cDNA fusion molecules. |

| Proteases (Trypsin/Chymotrypsin) | Enzymes that selectively cleave unfolded proteins; using two provides orthogonal data. |

| N-terminal PA Tag | Enables pull-down of intact (protease-resistant) protein–cDNA complexes after proteolysis. |

| Deep Sequencing | Quantifies relative abundance of surviving sequences at each protease concentration. |

The experimental workflow begins with a DNA library, which is transcribed and translated using cell-free cDNA display to produce proteins covalently linked to their encoding cDNA. These complexes are incubated with varying concentrations of protease (trypsin or chymotrypsin). Folded, protease-resistant proteins survive and are purified via their N-terminal PA tag. Deep sequencing of the surviving pool at each protease concentration enables the inference of protease stability (K50) for each sequence [12].

A Bayesian kinetic model, assuming single-turnover protease cleavage kinetics, is used to infer thermodynamic folding stability (ΔG). The model estimates a unique K50,U (protease susceptibility in the unfolded state) for each sequence, uses a universal K50,F for the folded state, and assumes rapid equilibrium between folding, unfolding, and enzyme binding relative to cleavage [12]. The resulting ΔG values show high consistency with traditional purified protein experiments (Pearson correlations > 0.75 for 1,188 variants of 10 proteins) [12].

Diagram 1: cDNA Display Proteolysis Workflow

This method has been applied to generate an unprecedented dataset of 776,298 absolute folding stabilities, encompassing all single amino acid variants and selected double mutants of 331 natural and 148 de novo designed protein domains [12]. The scale of this data provides a powerful resource for quantifying thermodynamic couplings between sites and evaluating the divergence between evolutionary amino acid usage and folding stability.

The Rise ofAb InitioStructure Prediction

The thermodynamic hypothesis implicitly promised that knowing the sequence should be sufficient to predict the structure. For decades, this remained an unsolved challenge until the emergence of artificial intelligence-driven approaches.

The AlphaFold Revolution

A transformative breakthrough occurred in 2020 with the unveillance of AlphaFold2 by Google DeepMind. This AI tool generated stunningly accurate 3D protein models that were in many cases indistinguishable from experimental structures [13]. The subsequent release of the AlphaFold database in partnership with EMBL-EBI, which now contains over 240 million predicted structures, has fundamentally changed the practice of structural biology [13] [14]. The database has been accessed by 3.3 million users in over 190 countries, dramatically expanding global access to structural information [13].

The impact on research has been quantifiably profound. Researchers using AlphaFold submit approximately 50% more protein structures to the Protein Data Bank compared to a non-using baseline [13]. Furthermore, AlphaFold-related research is twice as likely to be cited in clinical articles and is significantly more likely to be cited by patents, indicating its translation into applied and therapeutic contexts [14].

Table 2: AlphaFold Database Impact Metrics

| Metric | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Predicted Structures | >240 million [13] | Covers nearly all catalogued proteins |

| Global Users | 3.3 million [13] | Widespread adoption across 190+ countries |

| Research Papers | ~40,000 [13] | Extensive use in scientific literature |

| PDB Submissions Increase | ~50% [13] | Accelerates experimental structure determination |

Keeping Predictions Current: The AlphaSync Database

A critical challenge in maintaining prediction accuracy is the constant discovery of new protein sequences and corrections to existing ones. The AlphaSync database addresses this by providing continuously updated predicted structures, ensuring researchers work with the most current information [15]. When first deployed, AlphaSync identified a backlog of 60,000 outdated structures, including 3% of human proteins requiring updated predictions [15]. AlphaSync provides not only updated structures but also pre-computed data including residue interaction networks, surface accessibility, and disorder status, formatted for ease of use in machine learning applications [15].

Beyond Monomeric Proteins: AlphaFold3 and Drug Discovery

The evolution of these tools continues with AlphaFold3, which expands predictive capability beyond single proteins to the structures and interactions of DNA, RNA, ligands, and entire molecular complexes [14]. This provides a holistic view of biological systems, such as how a potential drug molecule (ligand) binds its target protein. This capability is being leveraged by Isomorphic Labs to develop a "unified drug design engine," aiming to dramatically accelerate the development of new medicines [14].

EvaluatingAb InitioPredictions Within the Thermodynamic Framework

The success of AlphaFold and similar tools provides a compelling validation of the thermodynamic hypothesis from a computational perspective. The models effectively learn the mapping between sequence and native structure that Anfinsen postulated, implicitly capturing the physical laws and evolutionary constraints that shape the free energy landscape.

Diagram 2: From Sequence to Structure: Computational & Experimental Paths

However, important distinctions remain between computational prediction and the physical folding process:

- Implicit vs. Explicit Thermodynamics: AlphaFold predicts the native structure directly but does not explicitly simulate the folding pathway or compute the absolute free energy of the system. It learns the outcome of folding rather than the thermodynamic process itself.

- The Role of High-Throughput Data: The massive stability datasets generated by methods like cDNA display proteolysis are now serving as critical benchmarks for evaluating and refining computational models. They provide direct thermodynamic measurements against which prediction tools can be validated [12].

- Limitations and Exceptions: Computational models face challenges with the very exceptions that challenge Anfinsen's dogma, such as fold-switching proteins and conformations associated with aggregation diseases. These areas represent the frontier of protein prediction research.

The convergence of high-throughput experimental thermodynamics and AI-based structure prediction creates a powerful feedback loop. Experimental data trains and validates models, while models generate hypotheses about folding stability that can be tested experimentally.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Folding Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Urea | Chemical denaturant | Preferred over guanidinium salts for linear extrapolation in stability assays [11]. |

| 50 mM Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.0) | Standardized solvent | Consensus condition for folding kinetics; buffers well at neutral pH [11]. |

| Trypsin/Chymotrypsin | Site-specific proteases | Used in proteolysis assays to distinguish folded/unfolded states; orthogonal cleavage specificities improve reliability [12]. |

| PA Tag | Epitope tag | Enables immunopurification of intact protein-cDNA fusions in display technologies [12]. |

| AlphaFold Database | Structure prediction repository | Provides immediate access to reliable models for most known proteins; accelerates hypothesis generation [13]. |

| AlphaSync Database | Updated structure database | Ensures access to current predictions as new sequence data emerges; includes pre-computed interaction networks [15]. |

| cDNA Display Kit | In vitro display platform | Enables high-throughput stability mapping for up to 900,000 variants without cellular constraints [12]. |

The protein folding problem, guided by the thermodynamic hypothesis, has evolved from a fundamental biophysical question into a field revolutionized by data-driven discovery. Anfinsen's core principle—that sequence determines structure—has been overwhelmingly validated by the success of ab initio prediction tools like AlphaFold. However, the interplay between classical thermodynamics, high-throughput experimentation, and artificial intelligence continues to deepen our understanding. Mega-scale stability experiments provide the quantitative thermodynamic data needed to dissect the folding code, while continuously updated computational databases translate this understanding into practical tools for researchers worldwide. For drug development professionals and researchers, this integrated toolkit enables a more rapid transition from genetic sequence to functional insight, accelerating the design of therapeutics that target precisely understood molecular structures. The evaluation of ab initio predictions must therefore rest on a foundation that combines computational accuracy with experimental thermodynamic validation, ensuring that models not only predict structure but also reflect the energetic landscape that governs biological function.

The process by which a linear amino acid chain folds into a unique, functional three-dimensional structure is fundamental to molecular biology. This process, however, presents a profound conceptual challenge known as Levinthal's paradox. First articulated by Cyrus Levinthal in 1968 and 1969, this paradox highlights the astronomical disconnect between the vast theoretical conformational space of an unfolded polypeptide and the rapid, reproducible folding observed in nature [16] [17]. For a typical protein of 100 residues, the number of possible conformations is estimated to be at least 2^100 or approximately 10^300, considering just two stable conformations per residue [18]. If a protein were to sample these conformations at the rate of molecular vibrations (every picosecond), the time required to randomly locate the native state would exceed the age of the universe [18] [16]. Yet, in reality, proteins achieve this feat within milliseconds to seconds [17].

This paradox framed one of the most enduring problems in computational biophysics: how can proteins reliably and quickly find their native state without an exhaustive search? For researchers focused on ab initio protein structure prediction—which aims to predict structure from physical principles alone without relying on known templates—this paradox represents the central computational hurdle. Resolving it is not merely a theoretical exercise but a prerequisite for developing efficient and accurate prediction algorithms. This review deconstructs the paradox, outlines the theoretical and experimental evidence for its resolution, and discusses the implications for modern computational approaches.

Deconstructing the Paradox: A Quantitative Analysis

The Foundations: Anfinsen's Dogma and Levinthal's Calculation

The protein folding problem rests on two foundational concepts. First, Anfinsen's thermodynamic hypothesis posits that the native structure of a protein is the one in which its free energy is at a global minimum under physiological conditions [18]. This suggests that the sequence alone determines the structure. Second, Levinthal's thought experiment demonstrated that a random, undirected search for this minimum is kinetically impossible [18] [16]. The core of the paradox lies in reconciling the thermodynamic control implied by Anfinsen with the apparent kinetic impossibility highlighted by Levinthal.

Table 1: Parameters of Levinthal's Paradox for a Model Protein

| Parameter | Value & Explanation | Source / Basis of Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Length | 100 amino acid residues | Representative single-domain globular protein [18] |

| Conformations per Residue | At least 2 (≥10 possible in a more detailed estimate) | Steric constraints and known phi/psi angles [18] [16] |

| Total Possible Conformations | ≥ 2^100 ≈ 1.3 x 10^30 (or 3^200 ≈ 2.7 x 10^95 in a stricter calculation) | Back-of-the-envelope calculation [18] [17] |

| Sampling Rate | 1 conformation per picosecond (10^-12 s) | Time of thermal atomic vibration [18] |

| Time for Exhaustive Search | > 10^10 years (far exceeding the age of the universe) | Calculation based on above parameters [18] [16] |

| Actual Observed Folding Time | Microseconds to seconds | Experimental evidence [18] [17] |

The Implication for ab initio Structure Prediction

Levinthal concluded that proteins cannot fold by a random search and that the native state might not necessarily be the global free energy minimum, but rather a kinetically accessible metastable state [18] [17]. This "kinetic control" hypothesis suggested that evolution has selected for proteins with specific folding pathways. For ab initio prediction, this initially implied that successful algorithms would need to simulate these specific, guided pathways—a daunting task given the immense computational resources required to simulate folding at an atomic level over biologically relevant timescales. The challenge is to design algorithms that can navigate this vast conformational space without exhaustive enumeration, mirroring the efficiency of natural folding.

Resolving the Paradox: The Energy Landscape Theory

The solution to Levinthal's paradox emerged from a shift in perspective: from viewing folding as a search through a vast number of distinct conformations to visualizing it as a funnelled flow through a biased energy landscape [18] [16].

The Folding Funnel and Its Principles

The "folding funnel" theory posits that the energy landscape of a foldable protein is not random or rugged. Instead, it is relatively smooth and biased toward the native state. The key principles are:

- Guided Diffusion: The protein does not sample conformations randomly. The energy landscape is structured so that the formation of local native-like interactions progressively reduces the conformational space that needs to be searched, guiding the chain toward the native state [18] [17].

- Progressive Stabilization: As these local structures (e.g., alpha-helices, beta-hairpins) form, they act as nucleation points that stabilize intermediate structures and guide the formation of subsequent long-range interactions [16].

- Hierarchical Assembly: Folding often proceeds through a hierarchy of steps, where local secondary structures form first, followed by the consolidation of the tertiary fold [19].

This funnel-shaped energy landscape allows a protein to rapidly find its native state without exploring all possible conformations. The theory reconciles Anfinsen's and Levinthal's views: the native state is indeed the global free energy minimum (addressing thermodynamics), and the funnel provides a kinetic pathway that makes reaching this state feasible [18].

Diagram 1: The protein folding funnel concept. The pathway is guided by a biased energy landscape, not random search.

Experimental Validation of the Landscape Theory

Experimental evidence supports this theoretical framework. Key methodologies have been crucial in characterizing folding pathways and intermediates.

Table 2: Key Experimental Methods for Studying Protein Folding

| Method / Reagent | Category | Function in Folding Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Phi-Value (Φ) Analysis | Computational & Biophysical | Identifies the structure of the folding transition state (nucleus) by measuring how mutations affect folding kinetics and stability [18]. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Biophysical | Monitors protein folding in real-time, providing atomic-level resolution on structural changes and intermediate states [18]. |

| Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) | Spectroscopic | Measures changes in distance between specific points in the protein during folding, useful for both in vitro and co-translational studies [18]. |

| Temperature-Sensitive Mutants | Genetic & Biophysical | Decouples folding kinetics from thermodynamic stability, demonstrating that the folding pathway has specific constraints distinct from the final state's stability [17]. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectroscopy | Kinetic | Allows rapid mixing of denaturant and protein solution to initiate folding, enabling measurement of very fast (millisecond) folding kinetics. |

Levinthal's own experiments on alkaline phosphatase mutants provided early evidence. He observed that while the folded mutant protein was as stable as the wild-type at high temperatures, it could only fold correctly at lower temperatures. This demonstrated that the folding pathway itself has specific energetic constraints that are separate from the stability of the final native structure [17]. Furthermore, phi-value analysis has shown that the same folding nucleus is often used during folding on and off the ribosome, indicating a robust and conserved folding pathway for many domains [18].

Implications for ab initio Protein Structure Prediction

The resolution of Levinthal's paradox directly informs the design of computational protein structure prediction methods, particularly the ab initio (or de novo) approaches.

Algorithmic Strategies to Navigate Conformational Space

Instead of a brute-force search, successful ab initio algorithms incorporate strategies that mimic the natural funneling process:

- Fragment Assembly: Local sequence segments (e.g., 3-9 residues long) are used to query databases of known structures. The resulting short fragments, which often represent low-energy local conformations, are assembled into full-length models. This strategy directly implements the concept of rapid local structure formation guiding further folding and has been a key factor in improving prediction performance [20].

- Simplified Protein Representations: To make the computational problem tractable, many algorithms use reduced representations, such as a Cα-trace or unified residue (UNRES) models, which drastically decrease the number of degrees of freedom that need to be optimized [20].

- Restricted Conformational Sampling: Algorithms limit the dihedral angle space sampled by residues to statistically favored regions derived from known structures (e.g., using rotamer libraries), thereby pruning the search tree [20].

- Knowledge-Based Energy Functions: The energy functions used to score candidate structures often incorporate statistical potentials derived from known protein structures, effectively biasing the search toward native-like features, analogous to a natural folding funnel [20].

Performance and Limitations

The performance of ab initio methods has been historically benchmarked in competitions like CASP (Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction). While recent deep learning methods like AlphaFold2 have revolutionized template-based modeling, ab initio approaches remain relevant for proteins with no evolutionary relatives in databases [21] [22]. However, they still encounter difficulties, which may be due to the small free energy differences between a protein's native state and some alternate conformations, making the global minimum hard to identify computationally [19] [20]. The best-performing algorithms balance the complexity of the energy function with efficient search strategies to navigate the conformational space within a reasonable computational time [20].

Diagram 2: A generalized ab initio prediction workflow. The process avoids exhaustive search through iterative sampling and scoring.

Levinthal's paradox was a foundational thought experiment that correctly identified the impossibility of a random conformational search during protein folding. Its resolution through the energy landscape and funnel theory revealed that proteins fold via guided kinetic pathways where local interactions nucleate and direct the search, dramatically reducing the effective conformational space. For the field of ab initio protein structure prediction, this insight is critical. It dictates that successful algorithms must not merely compute physics-based energies but must also incorporate strategic biases—like fragment assembly and restricted sampling—to efficiently navigate the astronomical number of possible conformations. While modern AI-driven methods have achieved remarkable success, the principles derived from solving Levinthal's paradox continue to underpin the physical understanding and computational pursuit of predicting protein structure from sequence alone.

Ab initio protein structure prediction represents a cornerstone of computational biology, aiming to determine the three-dimensional structure of a protein from its amino acid sequence alone, without relying on evolutionary-related structural templates [23] [24]. The ability to accurately predict protein structure is fundamental to biomedicine, as a protein's function is dictated by its structure. This capability accelerates the functional annotation of genomes, enables the study of proteins that are difficult to characterize experimentally, and directly informs drug discovery and protein engineering efforts [24]. For decades, ab initio prediction was a formidable challenge due to the vast conformational space that must be searched. However, the field has been revolutionized by the advent of deep learning methods, most notably AlphaFold2, which have dramatically improved accuracy [25]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the core methodologies, evaluation frameworks, and biomedical applications of ab initio protein structure prediction, with a specific focus on its critical role in functional annotation and novel fold discovery.

Fundamentals of Ab Initio Protein Structure Prediction

The Protein Folding Problem and Energy Landscapes

The "protein folding problem" refers to the challenge of understanding how a linear polypeptide chain folds into its unique, biologically active three-dimensional conformation within milliseconds to seconds [24]. This process is governed by a complex interplay of forces, including hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals forces. Levinthal's paradox highlights the apparent contradiction between the vast number of possible conformations and the rapid, directed folding observed in nature [24]. This paradox is resolved by the energy landscape theory, which visualizes protein folding as a navigation down a funnel-shaped energy surface. The native state resides at the global energy minimum, and the folding pathway is guided by energetically favorable gradients that efficiently lead the protein to its stable structure [24].

Evolution of Computational Approaches

Traditional ab initio methods relied heavily on physics-based principles and sophisticated sampling algorithms to explore the conformational space. Key methodologies included:

- Fragment Assembly: Protein sequences are broken down into short fragments (typically 3-9 residues), whose structures are predicted from libraries of known fragments. These are then assembled into full-length models using search algorithms like Replica-Exchange Monte Carlo (REMC) [26] [5].

- Sampling Algorithms: Techniques like Monte Carlo simulations and simulated annealing were employed to efficiently sample possible conformations, accepting or rejecting new structures based on energy calculations to avoid local minima [24].

- Hybrid Energy Functions: These functions combine physics-based potentials (derived from fundamental chemical principles) with knowledge-based potentials (statistical preferences derived from known protein structures in databases like the PDB) to guide the search toward native-like structures [24].

The development of these methods, exemplified by pipelines like QUARK and Rosetta, steadily improved prediction accuracy for small proteins. However, consistent and accurate prediction for larger, more complex proteins remained a significant challenge until the rise of deep learning [20] [5].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The Deep Learning Revolution: AlphaFold and Beyond

A paradigm shift occurred with the introduction of AlphaFold2, a deep learning system that achieved accuracy competitive with experimental methods in the CASP14 assessment [25]. Its architecture leverages attention mechanisms and evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) to model relationships between residues, even those far apart in the sequence. Unlike traditional methods that simulate folding pathways, AlphaFold2 learns the direct mapping from sequence to structure. Key innovations include:

- Evoformer: A deep learning module that jointly processes sequence and MSAs to reason about the spatial and evolutionary constraints on the protein.

- Structural Module: Uses rotations and translations to build the atomic protein structure iteratively.

- End-to-End Learning: The entire structure is predicted as an output of the neural network, rather than assembled via fragment assembly [25].

Other notable deep learning tools include RoseTTAFold and ESMFold, the latter enabling extremely rapid prediction by training on a large corpus of protein sequences [27].

Integrating Contact Predictions with Fragment Assembly

Even before deep learning, a powerful strategy involved using predicted inter-residue contacts to guide fragment assembly. The C-QUARK pipeline exemplifies this approach, demonstrating how low-accuracy contact maps can be effectively harnessed [5]. Table 1: Key Components of the C-QUARK Folding Pipeline

| Component | Description | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | Generated from whole-genome and metagenome databases. | Provides evolutionary information for contact prediction. |

| Deep-Learning & Coevolution Contact Maps | Predicts spatial proximity of residue pairs using deep learning (e.g., DeepMind's network) and coevolution analysis (e.g., DCA). | Generates restraints to guide the folding simulation. |

| Fragment Library | 1-20 residue fragments extracted from the PDB. | Provides local structural building blocks. |

| Replica-Exchange Monte Carlo (REMC) | A conformational search algorithm. | Assembles fragments into full-length models under the guidance of energy functions and contact restraints. |

| 3-Gradient Contact Potential | A custom energy term with three smooth platforms for different distance ranges. | Integrates noisy contact predictions with the knowledge-based force field. |

Experimental Protocol for C-QUARK:

- Input Preparation: Provide the target protein's amino acid sequence.

- MSA Generation: Build a multiple sequence alignment from relevant databases.

- Contact Prediction: Generate multiple contact maps using deep-learning and coevolution-based predictors.

- Fragment Assembly Simulation:

- Conduct REMC simulations that repeatedly propose new conformations by swapping in fragment structures.

- Score each conformation using a composite force field that includes the knowledge-based energy terms, fragment-derived contacts, and the sequence-based contact-map predictions weighted by the 3-gradient potential.

- Model Selection: Cluster the resulting decoys (e.g., using SPICKER) and select the most representative model from the largest cluster as the final prediction [5].

Workflow Visualization: Traditional vs. Modern Ab Initio Prediction

The following diagram illustrates the core differences between the traditional fragment-based approach and the modern deep learning paradigm.

(Diagram: Comparison of Traditional and Modern Ab Initio Workflows)

Evaluation of Prediction Accuracy

Rigorous evaluation is essential for assessing the quality of predicted protein models and guiding method development. Metrics can be divided into those that require a known native structure and those that are internal to the prediction.

Standard Evaluation Metrics

Table 2: Key Metrics for Evaluating Predicted Protein Structures

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Global Distance Test (GDT_TS) | Measures the percentage of Cα atoms within a defined distance cutoff (e.g., 1-8 Å) after superposition. A higher score is better. | A GDT_TS > 90 is considered competitive with experimental structures; a score > 50 generally indicates a correct fold [27] [5]. |

| Template Modeling Score (TM-score) | A metric for structural similarity that is less sensitive to local errors than RMSD. Ranges from 0-1. | A TM-score > 0.5 indicates a model with the same fold as the native structure. A score < 0.17 corresponds to random similarity [5]. |

| Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) | Measures the average distance between corresponding Cα atoms after optimal alignment. Given in Angstroms (Å). | Lower values are better. Sensitive to large local deviations and domain movements, making it less ideal for assessing global fold [24]. |

| Predicted lDDT (pLDDT) | A per-residue confidence score predicted by AlphaFold2, ranging from 0-100. | pLDDT > 90: Very high confidence. 70-90: Confident. 50-70: Low confidence. <50: Very low confidence, often disordered regions [27]. |

| Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) | A 2D plot from AlphaFold2 predicting the positional error (in Å) for each residue pair after optimal alignment. | Useful for assessing inter-domain confidence and identifying potentially mis-oriented domains or flexible regions [27]. |

Validation Against Experimental Data

While initial assessments compared AlphaFold predictions to existing PDB models, recent work has taken the critical step of comparing predictions directly against unbiased experimental crystallographic electron density maps. This reveals that even high-confidence predictions (pLDDT > 90) can sometimes differ from experimental maps on a global scale (e.g., domain orientation distortions) and locally in backbone or side-chain conformation [28]. A study of 102 such maps found the mean map-model correlation for AlphaFold predictions was 0.56, substantially lower than the 0.86 for deposited models, though morphing the predictions to reduce distortion significantly improved agreement (correlation of 0.67) [28]. This underscores that AlphaFold predictions should be treated as exceptionally useful hypotheses that can accelerate, but not always replace, experimental structure determination, especially for detailing ligand interactions or environmental effects [28].

Functional Annotation via Structural Similarity

A powerful application of ab initio prediction is the functional annotation of proteins, particularly for non-model organisms where sequence similarity to characterized proteins is low.

The MorF Workflow for Cross-Phyla Annotation

The MorF (MorphologFinder) workflow leverages the principle that protein structure is more evolutionarily conserved than sequence [29]. It has been successfully used to annotate the proteome of the freshwater sponge Spongilla lacustris, an early-branching animal.

(Diagram: MorF Structural Annotation Workflow)

Protocol for MorF:

- Structure Prediction: Use a tool like ColabFold to predict 3D structures for all proteins in a proteome.

- Structural Search: Align the predicted structures against structural databases (AlphaFoldDB, PDB, SwissProt) using a fast structural alignment tool like Foldseek.

- Annotation Transfer: Identify the best structural match (the "morpholog") for each query protein and transfer the functional annotation (e.g., preferred name, Gene Ontology terms, Enzyme Commission numbers) from the morpholog to the query protein [29].

This approach annotated ~60% of the Spongilla proteome, a 50% increase over standard sequence-based methods (BLASTp + EggNOG-mapper), and accurately predicted functions for over 90% of proteins with known homology [29]. It uncovered new cell signaling functions in sponge epithelia and proposed a digestive role for previously uncharacterized mesocytes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Database Tools for Ab Initio Prediction and Annotation

| Tool Name | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 / ColabFold | Structure Prediction | ColabFold combines AlphaFold2 with fast homology search (MMseqs2), enabling accelerated predictions without specialized hardware [29] [27]. |

| RoseTTAFold | Structure Prediction | A deep learning-based protein structure prediction tool using a three-track neural network architecture [27]. |

| Rosetta | Software Suite | A comprehensive platform for macromolecular modeling, including the FragmentSampler for classic ab initio structure prediction [26]. |

| Foldseek | Structural Alignment | Rapidly searches and aligns protein structures, enabling large-scale comparison of predicted models against databases [29]. |

| AlphaFold Database | Database | Repository of over 214 million pre-computed AlphaFold2 predictions, allowing researchers to download models without running the software [25]. |

| EggNOG-mapper | Functional Annotation | Tool for fast functional annotation of novel sequences based on orthology assignment, often used in conjunction with structural methods [29]. |

| Phenix & CCP4 | Software Suites | Crystallography toolkits that now incorporate utilities for processing AlphaFold predictions for molecular replacement [25]. |

Impact on Biomedicine and Drug Development

The advancements in ab initio structure prediction are having a tangible impact across multiple domains of biomedicine.

Accelerating Experimental Structure Determination: In X-ray crystallography, AlphaFold predictions are routinely used as search models for Molecular Replacement, a method for phasing diffraction data. This has solved previously intractable cases, such as proteins with novel folds or no close homologs in the PDB [25]. In cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM), predicted models are fitted into lower-resolution density maps to aid in model building and validation, as demonstrated in studies of large complexes like the nuclear pore complex [25].

Drug Discovery and Protein Engineering: Predicted structures enable virtual screening of large compound libraries against protein targets, even in the absence of experimental structures. This is particularly valuable for poorly characterized proteins from non-model organisms or human proteins that are difficult to purify [24]. Furthermore, accurate models guide the rational design of proteins with enhanced stability, novel enzymatic activity, or specific binding properties for therapeutic and industrial applications [24].

Elucidating Protein-Protein Interactions: Specialized versions like AlphaFold-Multimer can predict the structure of protein complexes. This has been used in large-scale screens to identify novel interactions and propose mechanistic models for biological pathways, such as the function of the midnolin-proteasome system in transcription factor degradation [25].

Ab initio protein structure prediction has matured from a formidable theoretical challenge into an indispensable tool for biomedical research. The convergence of sophisticated fragment-based methods, powerful contact-guided restraints, and revolutionary deep learning has enabled the accurate prediction of protein structures from sequence alone. As validated against experimental data, these predictions serve as powerful hypotheses that dramatically accelerate research. The subsequent use of structural similarity for functional annotation, especially for evolutionarily distant organisms, is unlocking a deeper understanding of proteomes and cellular processes. As these tools become more integrated into scientific workflows, their role in driving discovery in basic biology, drug development, and protein design will only continue to expand, solidifying their critical role in modern biomedicine.

Algorithmic Evolution: From Physics-Based Potentials to Deep Learning Architectures

Within the field of computational biology, the "protein folding problem"—predicting a protein's three-dimensional native structure solely from its amino acid sequence—represents a monumental challenge [20]. Ab initio protein structure prediction methods aim to solve this problem using physical principles and computational models without relying on known structural templates [24]. Among these, three historical approaches have fundamentally shaped the discipline: Fragment Assembly, the UNRES (UNited RESidue) model, and the Rosetta protocol. These methodologies form the foundational pillars upon which modern successes, including deep learning systems like AlphaFold, were built [30]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical evaluation of these core approaches, examining their theoretical underpinnings, algorithmic implementations, and performance within the context of ab initio prediction research, offering drug development professionals and scientists a clear understanding of their evolution, capabilities, and limitations.

Core Methodologies and Theoretical Foundations

Fragment Assembly

The Fragment Assembly technique is predicated on the observation that local amino acid sequences exhibit strong preferences for certain local structural features, a concept often described as the "local sequence-structure relationship" [31] [32]. This approach bypasses the insurmountable computational complexity of atom-level simulation by breaking down the target protein sequence into short overlapping segments, typically 3 and 9 residues long [32].

- Fragment Library Construction: For each position in the target sequence, a set of candidate fragments is extracted from a database of known protein structures (e.g., the Protein Data Bank). Selection is based on sequence similarity and predicted secondary structure matching, creating a library of potential local conformations for every part of the protein [31].

- Stochastic Assembly: The global structure is then assembled through a stochastic process that randomly inserts fragments from this library, guided by a knowledge-based scoring function that approximates the protein's free energy [32]. This process employs Monte Carlo sampling and simulated annealing to navigate the vast conformational space efficiently, accepting or rejecting moves based on the Metropolis criterion to escape local energy minima [32].

UNRES Coarse-Grained Model

The UNRES model represents a physics-based, coarse-grained approach that drastically reduces the number of degrees of freedom in the system [33]. In contrast to Fragment Assembly, UNRES is derived from the statistical mechanical potential of mean force of a polypeptide chain, where unwanted degrees of freedom are analytically integrated out [33].

- Model Representation: A polypeptide chain is represented by a sequence of α-carbon (Cα) atoms linked by virtual bonds. Only two types of interaction sites are explicitly modeled: united peptide groups (p) located midway between consecutive Cαs, and united side chains (SC) attached to the Cαs [33]. This representation offers a 1,000-fold or greater extension of simulation time scale compared to all-atom models [33].

- Energy Function: The UNRES energy function is a weighted sum of terms accounting for various interactions and deformations [33]:

U = wSC∑i<jUSCiSCj + wSCp∑i≠jUSCipj + wppVDW∑i<j-1UpipjVDW + wppel f2(T)∑i<j-1Upipjel + wtor f2(T)∑iUtor(γi, θi, θi+1) + wb∑iUb(θi) + wrot∑iUrot(θi, r^SCi) + wbond∑iUbond(di) + ...- The force field includes multi-body terms that are essential for correctly reproducing regular secondary structures, a consequence of its rigorous physics-based derivation [33].

Rosetta Protocol

Rosetta combines principles of both fragment assembly and knowledge-based scoring, emerging as one of the most successful and widely used platforms for de novo structure prediction [30] [32]. Its algorithm is structured in multiple stages of increasing resolution.

- Low-Resolution Sampling (Rosetta Abinitio): The protocol begins with a simplified protein representation where side chains are replaced by a single centroid pseudoatom [32]. The search proceeds through four distinct stages, each employing different scoring functions (score0 to score5) and fragment sizes (9-residue fragments in stages 1-3, 3-residue fragments in stage 4) [32]. A key feature is its use of a Metropolis Monte Carlo sampling strategy with a quenching mechanism—if 150 consecutive fragment insertions are rejected, the temperature parameter is temporarily increased to help escape local minima [32].

- All-Atom Refinement: Promising low-resolution models undergo a final refinement step where full atomic detail is added, and the structure is optimized using more precise energy functions that include side-chain rotamer preferences and explicit hydrogen bonding [32].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Historical Ab Initio Approaches

| Feature | Fragment Assembly | UNRES Model | Rosetta Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Strategy | Knowledge-based; assembles local fragments from PDB | Physics-based; coarse-grained molecular dynamics | Hybrid; fragment assembly with knowledge-based scoring |

| Key Inputs | Target amino acid sequence; PDB-derived fragment libraries | Target amino acid sequence; physics-based force field parameters | Target sequence; PDB-derived fragment libraries; knowledge-based potentials |

| Representation | All-atom or backbone-heavy | United peptide group and side chain centers | Centroid pseudoatom (initial), all-atom (refinement) |

| Sampling Method | Monte Carlo, Simulated Annealing | Molecular Dynamics, Replica Exchange | Monte Carlo with temperature quenching |

| Energy Function | Knowledge-based scoring functions | Physics-based potential of mean force | Hybrid: knowledge-based and physics-based terms |

Performance and Comparative Evaluation

The quantitative assessment of prediction accuracy is typically conducted using metrics like Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and the Global Distance Test - Total Score (GDT-TS) [24]. The biennial CASP (Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction) experiment provides the primary benchmark for objectively comparing different methods [20] [31].

A comparative study of 18 different prediction algorithms reported average normalized RMSD scores ranging from 11.17 to 3.48, identifying I-TASSER (which utilizes fragment assembly) as the best-performing prediction algorithm at the time when considering both RMSD scores and CPU time [20]. The study also found that two algorithmic settings—protein representation and fragment assembly—had a definite positive influence on running time and predicted structure accuracy, respectively [20].

UNRES has demonstrated consistent performance in CASP experiments. In recent iterations, the implementation of a scale-consistent force field significantly improved the modeling of proteins with β and α+β structures, which had previously been a weakness, leading to higher resolution predictions [33].

Rosetta has remained competitive through continuous algorithmic innovations. For instance, a 2018 study demonstrated that redesigned search heuristics, including bilevel optimization and iterated local search, more frequently generated native-like predictions compared to the standard Rosetta Abinitio protocol when using the same fragment libraries [32]. Another strategy showed that customizing the number of fragment candidates based on the local predicted secondary structure could either improve model quality by 6-24% or achieve equivalent performance with 90% fewer decoys, dramatically reducing computational cost [31].

Table 2: Reported Performance of Ab Initio Methods

| Method / Tool | Reported Performance Metrics | Key Strengths | Evolution & Current Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| I-TASSER | Among CASP top performers; balanced RMSD and CPU time [20] | Full-length modeling; active site prediction [30] | Integrated deep learning; extended to protein function prediction |

| UNRES | Improved performance on β and α+β structures in CASP13/14 [33] | Physics-based; massive time-scale extension; can incorporate experimental restraints [33] | Web server with NMR, XL-MS, SAXS data-assisted simulations; nucleic acids extension [34] [33] |

| Rosetta | Superior exploration with high-quality fragments; improved low-resolution models [32] | Robust fragment assembly; active community development; handles various biomolecules | RoseTTAFoldNA extends to protein-DNA/RNA complexes [35]; CS-Rosetta uses NMR data [36] |

| QUARK | Excellent for small proteins; deep learning-based contact prediction [30] | De novo folding; distance-guided fragment assembly | Utilizes deep learning for contact prediction to guide folding |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Rosetta AbinitioRelax Protocol

The following methodology outlines a typical workflow for de novo structure prediction using Rosetta, as detailed in scientific reports [32].

Input Preparation:

- Target Sequence: Provide the amino acid sequence of the protein to be modeled.

- Fragment Library Generation: Use the

nnmakeapplication or a similar tool to generate two fragment libraries from the PDB: one containing 3-residue fragments and another containing 9-residue fragments. This process matches the target sequence segments to known structural fragments based on sequence similarity and secondary structure prediction.

Low-Resolution Phase (Centroid Mode):

- Initialization: Initialize the protein chain in an extended conformation with idealized geometry.

- Stage 1 (Randomization): Perform 2000 fragment insertion attempts (default) using 9-mer fragments to rapidly deviate from the initial extended state.

- Stage 2 (Optimization): Perform 2000 insertion attempts with 9-mer fragments using a scoring function that encourages compactness.

- Stage 3 (Refinement): Execute 10 sub-stages, each with 4000 9-mer fragment insertion attempts. Alternate between two scoring functions and employ a convergence check to terminate stagnant sub-stages early.

- Stage 4 (Fine-tuning): Perform 12,000 insertion attempts with 3-mer fragments. The final 8000 attempts incorporate the Gunn cost to minimize large structural perturbations.

High-Resolution Phase (All-Atom Relax):

- Full-Atom Representation: Convert the best-scoring centroid models from the low-resolution phase to full-atom representation.

- Side-Chain Packing: Optimize side-chain conformations using a rotamer library.

- Energy Minimization: Apply a combination of gradient-based minimization and Monte Carlo moves to relax the model and relieve atomic clashes under a more precise all-atom energy function.

Model Selection:

- Clustering: Cluster the resulting decoy structures based on structural similarity (e.g., using Cα RMSD).

- Selection: Select the center of the largest cluster or the lowest-energy model from the largest cluster as the final predicted structure.

Figure 1: Rosetta AbinitioRelax Workflow

UNRES Server Workflow for Data-Assisted Simulations

The UNRES web server enables coarse-grained simulations, including those restrained by experimental data [33].

Input Preparation:

- Sequence & Parameters: Submit the protein sequence and select simulation parameters (e.g., force field variant, temperature, number of replicas).

- Experimental Restraints (Optional): Provide experimental data in supported formats:

- NMR Restraints: Upload distance (e.g., NOEs) and/or dihedral angle restraints in NMR Exchange Format (NEF). The server handles ambiguous restraints automatically [33].

- Crosslink-MS Restraints: Provide crosslinking data to define spatial proximity constraints.

- SAXS Data: Input Small-Angle X-ray Scattering data for global shape validation.

Simulation Execution:

- Canonical MD or Replica Exchange: Run molecular dynamics (MD) or replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) simulations using the UNRES force field. The optimized code allows for efficient sampling of large systems [33].

- Restraint Incorporation: The server adds penalty terms to the UNRES energy function (Eq. 1) to incorporate the provided experimental data, biasing the simulation toward conformations that satisfy these restraints.

Trajectory Analysis and Model Building:

- Cluster Analysis: Cluster the resulting trajectory to identify representative low-energy structures.

- All-Atom Reconstruction: Use the

unres2pdbtool or similar methods to convert the selected coarse-grained models back to all-atom representations for downstream analysis.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Worldwide repository for 3D structural data of biological macromolecules. Source of known fragments for library construction and force field parameterization [31]. | Foundational resource for all fragment-based and knowledge-based methods. |

| CS-Rosetta | A specialized Rosetta protocol that uses NMR chemical shifts as the primary input for de novo structure generation, replacing or augmenting traditional fragment selection [36]. | Structure determination of small proteins where NMR chemical shift assignments are available. |

| UNRES Web Server | A publicly accessible interface for running coarse-grained simulations with the UNRES force field. Supports data-assisted calculations with NMR, XL-MS, and SAXS restraints [33]. | Physics-based folding simulations and integrative structure modeling. |

| Fragment Library | A collection of 3-mer and 9-mer peptide structures extracted from the PDB, matched to a target sequence. The core input for fragment assembly methods like Rosetta [32]. | Essential initial step for any fragment assembly prediction run. |

| Metropolis Criterion | A probabilistic rule (accepting moves with probability P=exp(-ΔE/kT)) used to decide whether to accept a conformation-changing move during Monte Carlo sampling [32]. | Core component of the search algorithm in Rosetta and other stochastic methods to escape local minima. |

| Scale-Consistent UNRES Force Field | A recent variant of the UNRES energy function derived using a scale-consistent theory, which significantly improves the prediction of β-sheet and α/β proteins [33]. | Production runs with UNRES for higher accuracy, particularly on beta-rich targets. |

| RoseTTAFoldNA | An extension of the RoseTTAFold architecture (related to Rosetta) that can predict protein-nucleic acid complexes from sequence alone [35]. | Modeling structures of protein-DNA and protein-RNA complexes. |

The historical approaches of Fragment Assembly, UNRES, and Rosetta have laid the essential groundwork for modern protein structure prediction. Each pioneered distinct strategies: Fragment Assembly demonstrated the power of leveraging local sequence-structure relationships, UNRES provided a rigorous physics-based framework through coarse-graining, and Rosetta integrated these ideas into a powerful, scalable hybrid platform. Their evolution, driven by community benchmarking like CASP, involved continuous refinement of energy functions, sampling heuristics, and the integration of experimental data. While contemporary AI-based methods have dramatically increased predictive accuracy, understanding these foundational approaches remains critical for researchers. They provide invaluable physical insights into the protein folding problem and continue to be adapted for novel challenges, such as predicting protein-nucleic acid complexes and modeling flexible systems, ensuring their continued relevance in structural biology and drug development.

The problem of protein structure prediction—determining the three-dimensional (3D) atomic coordinates of a protein from its amino acid sequence alone—has stood as a grand challenge in computational biology for over five decades [37]. The thermodynamic hypothesis of protein folding, proposed by Anfinsen, established the theoretical foundation that a protein's native structure resides in a global free energy minimum determined solely by its amino acid sequence [22]. However, the astronomical complexity of conformational space, exemplified by the Levinthal paradox, rendered exact computational solutions intractable for most proteins [22]. Traditional approaches to this problem have historically diverged into two principal paradigms: template-based modeling (TBM), which leverages evolutionary information from structurally characterized homologs, and ab initio or free modeling (FM), which relies purely on physical principles and conformational sampling without template reliance [38] [22].

The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments have served as the gold-standard benchmark for evaluating methodological progress in this domain since 1994 [37]. For years, performance in CASP revealed a stark divide: TBM methods achieved reasonable accuracy when homologous templates were available, while FM methods struggled to attain atomic-level accuracy, especially for larger proteins and those lacking evolutionary relatives [38]. This performance gap underscored fundamental limitations in both approaches—TBM's inherent dependency on known folds and FM's computational intractability for complex systems.

The 2020 CASP14 assessment marked a paradigm shift with the introduction of AlphaFold2 (AF2) by DeepMind [39]. AF2 demonstrated accuracy competitive with experimental methods in a majority of cases and dramatically outperformed all existing computational approaches [39] [37]. This breakthrough was not merely incremental improvement but represented a fundamental architectural revolution, centered on two core innovations: the Evoformer—a novel neural network architecture that jointly reasons about evolutionary and spatial relationships—and a fully end-to-end differentiable model that directly outputs accurate 3D atomic coordinates [39]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these innovations and their transformative impact on the field of ab initio protein structure prediction.

AlphaFold2 System Architecture

AlphaFold2 represents a complete architectural redesign from its predecessor, transitioning from a convolutional neural network that predicted pairwise distances followed by optimization, to an end-to-end differentiable model that directly outputs full-atom 3D coordinates [40] [41]. The overall system can be conceptually divided into three interconnected components: the input embedding processor, the Evoformer stack, and the structure module [40].

Input Preprocessing and Embedding