Addressing Alignment Errors in Template-Based Modeling: From Foundations to AI-Driven Solutions

Template-based modeling (TBM) remains a cornerstone of protein structure prediction, essential for illuminating structure-function relationships and guiding drug discovery.

Addressing Alignment Errors in Template-Based Modeling: From Foundations to AI-Driven Solutions

Abstract

Template-based modeling (TBM) remains a cornerstone of protein structure prediction, essential for illuminating structure-function relationships and guiding drug discovery. However, its accuracy is critically dependent on the quality of sequence-template alignments, with errors propagating to final 3D models and impacting downstream applications. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing alignment errors in TBM. We first explore the fundamental principles of TBM and the critical impact of alignment errors. We then detail cutting-edge methodological advancements, including the integration of deep learning and GPU-accelerated tools. A practical troubleshooting section covers common error identification and optimization strategies, while a final validation segment provides frameworks for benchmarking model quality. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with modern AI-driven applications and validation techniques, this article serves as a definitive resource for improving the reliability and accuracy of computational protein modeling in biomedical research.

The Critical Role of Alignment Accuracy in Template-Based Modeling

Core Principles of Template-Based Modeling

Template-based modeling, also known as homology modeling, is a method for predicting the three-dimensional structure of a protein from its amino acid sequence. The fundamental principle is that if two proteins share a significant sequence similarity, they will adopt similar three-dimensional conformations. A known experimental structure (the template) can therefore be used to model the unknown structure (the query) [1].

The core components of any workflow in this context involve inputs, transformations, and outputs [2] [3]. In template-based modeling:

- Input: The amino acid sequence of the query protein.

- Transformation: The process of aligning the query sequence to the template structure and building the model.

- Output: A three-dimensional atomic model of the query protein [1].

Standard Workflow for Template-Based Modeling

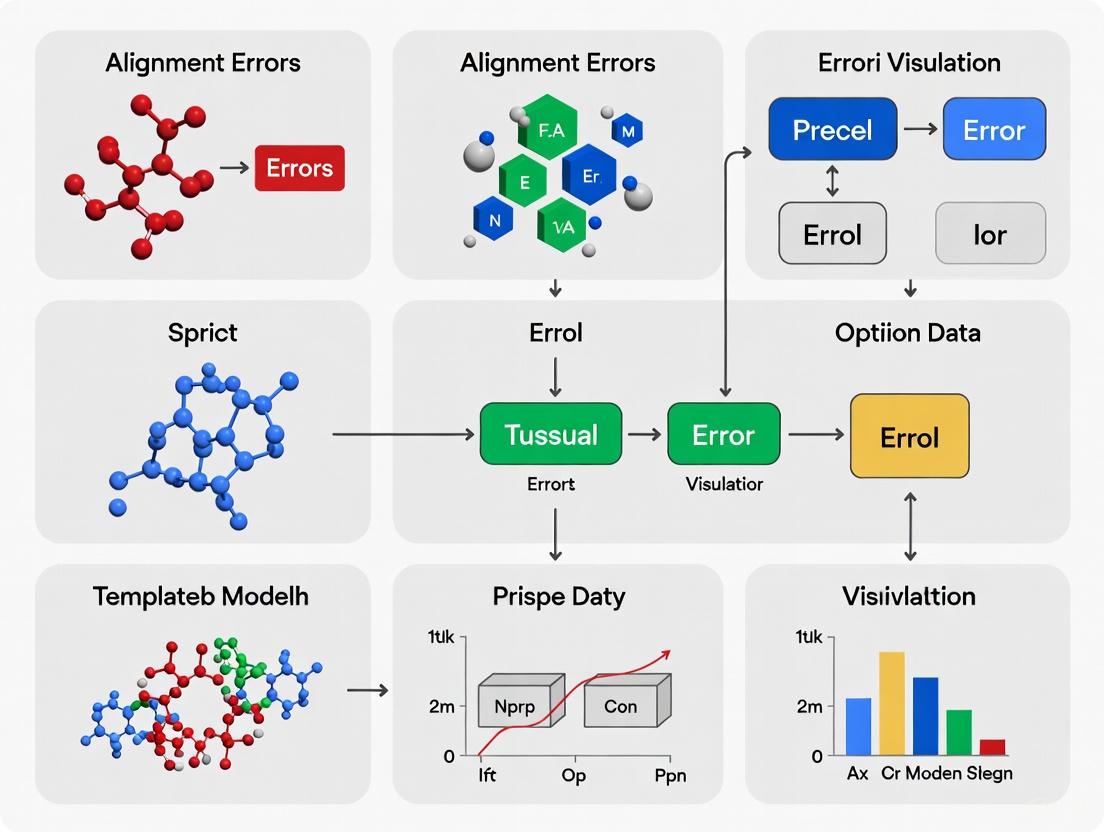

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key decision points in a standard template-based modeling workflow.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Template-Based Modeling

| Item | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Query Sequence | The amino acid sequence of the protein whose structure is being predicted. This is the primary input for the modeling process [1]. |

| Template Structure | A known protein structure (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank, PDB) that is similar in sequence to the query and serves as the scaffold for model building [1]. |

| Template Library (e.g., Phyre2.2) | A comprehensive database of known and predicted protein structures used to search for and identify a suitable template for a given query sequence [1]. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | Represents the evolutionary relationships of the query sequence to others, used to improve the accuracy of the sequence-structure alignment and model quality [1]. |

| Loop Fragment Library | A collection of short protein structure fragments used to model regions where the query and template sequences do not align (indels) [1]. |

| Side-Chain Rotamer Library (e.g., SCWRL4) | A backbone-dependent library of common side-chain conformations used to accurately place the side-chain atoms of the query sequence onto the model [1]. |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol: Template Identification and Selection

Objective: To find the most suitable template structure for the query sequence.

- Step 1: Submit your query sequence in FASTA format to a template modeling server (e.g., Phyre2.2) or perform a search against the PDB using tools like BLASTP or HMM-HMM alignment [1].

- Step 2: Analyze the search results. Key metrics to evaluate include:

- Sequence Identity: A higher percentage generally indicates a more reliable template.

- E-value: A lower E-value indicates a more statistically significant match.

- Coverage: The fraction of the query sequence that can be aligned to the template. Prioritize templates with high coverage [1].

- Step 3: If available, select a template that is in a functionally relevant state (e.g., "apo" for unliganded, "holo" for ligand-bound) for your biological question [1].

Protocol: Model Construction and Refinement

Objective: To build and refine a complete atomic model of the query protein.

- Step 1 (Backbone Construction): For residues aligned between the query and template, copy the backbone coordinates from the template. The backbone of well-aligned regions remains largely unchanged [1].

- Step 2 (Loop Modeling): For regions with insertions or deletions (indels), use a fragment library to build new backbone conformations. The protocol searches for fragments that fit the sequence and can be melded onto the flanking framework [1].

- Step 3 (Side-Chain Modeling): Replace the template side chains with those of the query sequence using a rotamer library (e.g., SCWRL4). The algorithm selects rotamers that optimize hydrogen bonding and van der Waals packing [1].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: What constitutes a "suitable template," and what should I do if I cannot find one?

Answer: A suitable template typically has a sequence identity of >25-30% to the query and provides high coverage over the query's functional domains. If no good experimental template is found, you can use a predicted structure from a database like AlphaFold Protein Structure Database or run your sequence through AlphaFold2/3, RoseTTAfold, or ESMFold. These machine learning-based approaches can generate accurate models even without a clearly identifiable template and can themselves be used as templates in servers like Phyre2.2 [1].

FAQ 2: My model has a region of very low sequence similarity to the template. How reliable is this part of the model?

Answer: Regions of low sequence similarity, especially loops, are much less reliable than well-aligned regions. You should treat these areas with caution. It is advisable to use the model's confidence scores (if provided) and consider running multiple independent modeling simulations to see if the same loop conformation is predicted consistently. For critical functional sites, experimental validation may be necessary.

Answer: Common sources of alignment errors include:

- Sequence Divergence: In remote homologs, the correct alignment may be obscured.

- Inserions/Deletions (Indels): Misplacement of indels can lead to incorrect register and distorted protein cores.

- Low-Complexity Regions: These can lead to spurious, biologically meaningless alignments.

To detect potential errors:

- Inspect the Alignment: Manually check the sequence-structure alignment for conservative vs. non-conservative substitutions in the protein core.

- Check Steric Clashes: Use visualization software to look for unreasonable atom-atom overlaps in the model.

- Verify Conserved Motifs: Ensure known active site or binding motif residues are correctly positioned.

- Use Alternative Methods: Compare your model to one generated by a completely different method (e.g., compare a template-based model to an AlphaFold2 prediction).

FAQ 4: How can I improve a model that has poor stereochemical quality or many atomic clashes?

Answer: Models can be refined using molecular mechanics force fields.

- Step 1: Subject the initial model to energy minimization. This process adjusts atomic positions to relieve steric clashes and improve bond geometry.

- Step 2: For more significant refinements, consider running short molecular dynamics simulations in explicit solvent to allow the model to relax into a more stable conformation.

- Step 3: Always validate the refined model using tools like MolProbity to check for Ramachandran plot outliers, rotamer outliers, and clash scores.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common sources of alignment errors in template-based modeling? The most common sources include using templates with low sequence identity to the target, incorrect selection of substitution matrices (like BLOSUM or PAM), the presence of low-complexity regions in the query sequence that confuse the alignment algorithm, and setting inappropriate E-value cutoffs that can either exclude relevant templates or include too many false positives [4].

Q2: What are the direct consequences of a poor sequence alignment on my final 3D model? A poor alignment directly leads to low-quality 3D models. Specific consequences include the creation of models with significant structural gaps in variable regions, poor stereochemistry (which can be identified via Ramachandran plots), and overall unstable models that may require extensive molecular dynamics for relaxation [4]. The initial alignment quality is a upper limit on final model quality [5].

Q3: My model has gaps in the structure after alignment. How can I fix this? Gaps typically occur in loop regions where the template and target sequence do not align. Standard practice is to perform targeted loop modeling to fill these regions. This can be done manually or by using refinement tools like MODELLER. Additionally, using multiple templates can provide structural information for different regions, allowing you to "mix and match" to create a more complete model [4] [5].

Q4: How do modern methods like AlphaFold impact the problem of alignment errors? Modern methods like AlphaFold2 and its successors have revolutionized the field by often producing accurate models even without an identifiable template, using advanced machine learning [1]. However, template-based modeling, including servers like Phyre2.2 which can use AlphaFold models as templates, remains highly valuable. It provides an alternative for assessment and allows researchers to build models based on specific, user-defined templates (e.g., a specific apo or holo form) that may not be represented in the AlphaFold database [1].

Q5: How can I improve a model that was built from a low-identity template? For models from low-identity templates, refinement is crucial. Advanced protocols involve using a graph-theoretic approach to mix and match optimal segments from multiple initial models created from different templates or alignments. This systematic recombination can yield a final model with higher quality than any of the individual starting models [5].

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide helps you diagnose and fix common alignment-related problems.

| Problem Description | Common Causes | Recommended Solutions & Methodologies |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Alignment Quality | Incorrect substitution matrix; overly strict E-value cutoff [4]. | 1. Choose Proper Matrix: Use BLOSUM45 for distant relationships, BLOSUM62 for general use [4].2. Adjust E-value: Loosen the E-value cutoff and check query coverage [4].3. Use PSI-BLAST: Perform iterative searches to find more distant homologs [1] [4]. |

| Low-Quality Template | Template with low sequence identity to target; single template used for a complex target [4]. | 1. Increase Identity: Find a template with higher sequence identity [4].2. Use Multiple Templates: Employ methods (e.g., MODELLER, clique finding) to combine data from several templates for different domains/regions [5].3. Leverage AlphaFold DB: Use Phyre2.2 to find the closest AlphaFold model as a high-quality starting point [1]. |

| Structure Gaps in Model | Indels (insertions/deletions) in the alignment not properly modeled [1] [4]. | 1. Model Loops: Use dedicated loop modeling protocols (e.g., mcgen_exhaustive_loop in RAMP suite) to sample conformations for gapped regions [5].2. Fragment Replacement: Use a Monte Carlo with simulated annealing procedure to find optimal fragment combinations [5]. |

| Unstable Model / Poor Stereochemistry | Inaccurate atom placement from alignment errors; clashes; unrealistic bond angles/lengths [4]. | 1. Energy Minimization: Perform minimization with adjusted constraints and protonation states [4].2. Validate: Use MolProbity for Ramachandran plots and other stereochemical checks [4].3. Molecular Dynamics: Pre-relax the model with short MD simulations to resolve clashes [4]. |

| Inaccurate Protein Complex Prediction | Failure to capture inter-chain interaction signals; lack of paired Multiple Sequence Alignments (pMSAs) [6]. | 1. Build Deep pMSAs: Use tools like DeepSCFold to predict interaction probabilities and construct biologically relevant paired MSAs [6].2. Integrate Multi-source Data: Combine species annotation, UniProt accessions, and PDB complex data to guide pairing [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Advanced Modeling

Protocol 1: Mixing and Matching Models with a Graph-Theoretic Clique Finding (CF) Approach

This protocol is designed to refine a model by systematically recombining the best segments from multiple initial models [5].

- Generate Initial Models: Create multiple comparative models for your target using different available templates and/or alignment methods. Ensure coverage so all residues have at least one possible conformation [5].

- Define Crossover Points: Superimpose the initial models. Use an automated method (like a median filter on Cα distances) to identify positions in the main chain where segments from different models can be swapped without causing structural clashes. These are your crossover points [5].

- Build a Conformational Graph: Represent every possible residue conformation from all initial models as a node in a graph. Assign node weights based on the local interaction strength (e.g., using an all-atom discriminatory function like RAPDF) [5].

- Establish Consistency Edges: Draw edges between nodes that are structurally consistent: within the same main chain segment, from different segments but spatially close, and not clashing. Weight edges based on inter-residue interaction strength [5].

- Find Optimal Cliques: Use a clique-finding algorithm (e.g., Bron-Kerbosch) to identify the largest sets of completely connected nodes (residue conformations) with the best overall weight. These cliques represent the optimal hybrid models [5].

- Select and Refine: The highest-weighted clique provides the final, refined model. Further side-chain optimization can be performed with tools like SCWRL3 [5].

Protocol 2: Constructing Paired MSAs for Protein Complex Prediction with DeepSCFold

This methodology outlines the construction of paired multiple sequence alignments (pMSAs) to enhance the prediction of protein complex structures by capturing inter-chain interactions [6].

- Generate Monomeric MSAs: Independently build deep multiple sequence alignments for each subunit of the protein complex from multiple sequence databases (UniRef30, UniRef90, Metaclust, etc.) [6].

- Rank by Structural Similarity: For each monomeric MSA, use a deep learning model to predict a protein-protein structural similarity score (pSS-score) between the query sequence and its homologs. Use this score, alongside sequence similarity, to rank and select the highest-quality monomeric MSAs [6].

- Predict Interaction Probabilities: For potential pairs of sequence homologs from different subunit MSAs, use a second deep learning model to predict an interaction probability score (pIA-score) based solely on sequence features [6].

- Construct Paired MSAs: Systematically concatenate monomeric homologs from different subunits into paired MSAs, guided by their high pIA-scores, which indicate a high probability of biological interaction [6].

- Integrate Biological Data: Augment the pMSAs by incorporating multi-source biological information, such as species annotations and known protein complexes from the PDB, to ensure biological relevance [6].

- Predict Complex Structure: Use the final set of high-quality pMSAs as input to a complex structure prediction system like AlphaFold-Multimer to generate the quaternary structure model [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| HHblits | A sensitive, fast tool for hidden Markov model (HMM) based sequence alignment against a database, used for finding remote homologs and generating MSAs [1]. |

| PSI-BLAST | Performs iterative BLAST searches to build a position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM), enabling the detection of more distantly related sequences for a deeper MSA [1]. |

| MODELLER | A widely used program for homology or comparative modeling of protein 3D structures. It can build models from multiple templates and satisfy spatial restraints [5]. |

| SCWRL4 | A software tool for predicting side-chain conformations on a fixed protein backbone, crucial for accurate model building after the backbone is constructed [1]. |

| MolProbity | A structure-validation tool that provides Ramachandran plot analysis, steric clash checks, and other metrics to evaluate the stereochemical quality of a molecular model [4]. |

| DeepSCFold | A pipeline that uses sequence-based deep learning to predict structural similarity and interaction probability, facilitating the construction of paired MSAs for accurate protein complex prediction [6]. |

| RAPDF | A residue-specific all-atom discriminatory function used to evaluate and score the quality of protein conformations, often used in clique-finding and model selection protocols [5]. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | An extension of AlphaFold2 specifically designed for predicting the structures of protein complexes (multimers), which utilizes paired MSAs to infer inter-chain interactions [6]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Standard Template-Based Modeling Workflow

Advanced Refinement by Mixing and Matching Models

Paired MSA Construction for Complexes

Understanding Template-Based Modeling (TBM)

What is Template-Based Modeling? Template-Based Modeling (TBM), which includes both comparative (homology) modeling and threading, is a computational approach that predicts a protein's 3D structure by leveraging its detectable similarity to at least one protein of known structure (the template) [7]. It operates on the principle that protein structure is more conserved through evolution than protein sequence. If two proteins share a detectable sequence similarity, they are likely to share a very similar 3D structure [8] [7].

How does it fit into the wider field of protein structure prediction? With over 80 million protein sequences known but only around 100,000 experimentally determined structures, TBM is a crucial technique for bridging this sequence-structure gap [8]. On average, it allows for the structural modeling of 50-70% of a typical genome, making it the most universally reliable and widely used method for protein structure prediction today [8].

Troubleshooting Common TBM & Alignment Errors

FAQ 1: I received a "Sequence Mismatch Error" in MODELLER. What does it mean and how can I fix it?

- Problem: The error message states:

Alignment sequence not found in PDB file[9]. This is a common issue where the sequence in your alignment file does not perfectly match the sequence of the atom records in the template PDB file you are using. - Solution:

- Verify Template Sequences: Manually check that the sequence in your alignment file for the template (e.g.,

2H5Y_A) exactly matches the residue sequence in the corresponding PDB file. Pay close attention to the starting and ending residues. - Specify Residue Numbers and Chain IDs: Modeller tries to guess the correspondence, but this can fail. Explicitly define the starting and ending residue numbers and chain IDs in your alignment file's PIR format as per Modeller's manual [9].

- Use

allow_alternates=True: In your Modeller script, you can set theallow_alternatesparameter toTrue. This allows Modeller to accept alternate one-letter amino acid code matches (for example, 'B' to 'N' or 'Z' to 'Q') [9].

- Verify Template Sequences: Manually check that the sequence in your alignment file for the template (e.g.,

FAQ 2: My model has poor quality in specific loop regions. What should I do?

- Problem: After generating a model, validation tools indicate that certain loops connecting secondary structure elements have high energy, strange geometry, or clash with the rest of the structure.

- Solution:

- Check the Alignment: Poor loops often stem from an incorrect sequence-structure alignment in the loop region. Visually inspect and manually refine the alignment if necessary.

- Utilize Specialized Loop Modeling: Use dedicated loop modeling servers like MODLOOP, which is integrated into the Modeller package and can refine loop regions independently [7].

- Consider Ab Initio Loop Modeling: For very long loops with no detectable template, ab initio methods within servers like Phyre2's "intensive mode" can be used, though they are less reliable [8].

FAQ 3: Phyre2 only modeled a small part of my protein. How can I get a more complete model?

- Problem: The initial "normal mode" run in Phyre2 produces a model that covers only a single domain or a fraction of your full-length sequence.

- Solution:

- Use "Intensive Mode": If your normal mode search indicates that no single template covers most of your sequence, resubmit your sequence using Phyre2's "intensive mode." This mode uses ab initio techniques to model regions where no clear template is found [8].

- Understand the Limitation: Be aware that for multi-domain proteins, if homology models of separate domains are combined using ab initio techniques, the relative orientation of the domains is very likely to be incorrect. Always check the results table to see which templates were used for different domains [8].

Experimental Protocol: A Standard TBM Workflow

This protocol outlines the key steps for building a protein model using a TBM server like Phyre2, followed by validation.

Step 1: Template Identification and Fold Recognition

- Objective: Find known protein structures (templates) related to your target sequence.

- Method: Submit your target protein sequence to a fold recognition server such as Phyre2, I-TASSER, or HHpred [8] [7]. These servers use advanced remote homology detection methods (e.g., profile-profile comparisons, Hidden Markov Models) to scan your sequence against libraries of known folds.

- Output: A list of potential templates with associated confidence scores.

Step 2: Target-Template Alignment

- Objective: Generate an optimal alignment between your target sequence and the selected template structure(s).

- Method: The server will typically generate the alignment automatically. For advanced users, the alignment can be manually inspected and refined using tools like T-COFFEE or PROMALS3D, incorporating secondary structure prediction to improve accuracy [7].

Step 3: Model Building

- Objective: Construct a full-atom 3D model of your target based on the alignment.

- Method: The server uses the alignment to build the model. This involves copying the coordinates of conserved core regions from the template and then modeling variable regions like loops and side chains. Servers use different techniques, including satisfaction of spatial restraints (e.g., Modeller) and fragment assembly [7].

Step 4: Model Evaluation

- Objective: Assess the quality and reliability of the generated model.

- Method: Use a combination of evaluation tools to check the model's stereochemical quality and overall fold. Key tools include:

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Research Reagent Solutions: Key Tools for TBM

The following table details essential computational tools and servers used in template-based modeling.

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in TBM | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phyre2 [8] [10] | Web Server | Protein fold recognition, 3D model building, and mutation analysis. | User-friendly interface; integrates remote homology detection, ab initio loop modeling, and effect of missense variant prediction. |

| I-TASSER [8] [7] | Web Server | Integrated platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. | Often shows a small performance improvement in difficult modeling tasks as per CASP trials. |

| Modeller [7] | Standalone Program | Comparative modeling of protein 3D structures. | Uses satisfaction of spatial restraints; highly customizable for expert users. |

| PSI-BLAST [7] | Algorithm/Web Tool | Sensitive sequence database search to identify distant homologs. | Constructs a sequence profile via iterative searching, improving sensitivity for remote template identification. |

| SWISS-MODEL [8] [7] | Web Server | Fully automated protein structure homology modeling. | User-friendly; relies on the SWISS-MODEL template library for automated model building. |

| PROCHECK [7] | Analysis Tool | Stereochemical quality check of protein structures. | Generates Ramachandran plots to assess the model's backbone conformation. |

Performance Metrics: Quantitative Data on TBM Servers

The table below summarizes the relative performance of different automated protein structure prediction servers as assessed by the international blind trial, CASP (Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction).

| Server/Method | CASP9 Ranking (out of ~55 groups) | CASP10 Ranking (out of ~45 groups) | Typical Model Quality (GDT_TS) Improvement over Phyre2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phyre2 | 6th [8] | 10th [8] | (Baseline) |

| I-TASSER | Among top 5 [8] | Among top 8 [8] | ~5-8% [8] |

| Other top-performing servers (e.g., Zhang-Server, MULTICOM) | Among top 5 [8] | Among top 8 [8] | ~2.8-3.7% [8] |

Note on Model Quality (GDTTS): A 1% improvement in GDTTS for a 200-residue protein roughly corresponds to 2 extra residues being positioned within 4.5Å of their correct location in the native structure [8].

The Future: AI-Enhanced Servers and Current Limitations

Advancements in AI-Enhanced Servers Modern servers like Phyre2.2 continue to evolve, integrating new features such as direct access to models from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database for one-to-one threading tasks [10]. The upcoming publication for Phyre2.2 highlights its role as a continually updated community resource [10].

Acknowledging Current Limitations Despite advancements, key limitations remain:

- Dependence on Homology: If no homologous structure can be detected, TBM will fail or be highly unreliable [8].

- Point Mutation Modeling: Phyre2 can predict the phenotypic effect of a point mutation but cannot accurately model the wider structural impact beyond a sidechain substitution. The protein backbone remains unchanged [8].

- Multi-domain and Transmembrane Proteins: Combining separate domain models or grafting globular domains onto transmembrane regions can lead to incorrect relative orientations if not guided by a single, overarching template [8].

- Multimer Prediction: As of now, Phyre2 cannot predict the structure of protein complexes (multimers), though this functionality is under development [8].

The logical relationship between a researcher's goal, the chosen tool, and the potential outcomes, including common errors, is illustrated below.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary limitation of sequence-based alignment methods like BLAST for functional annotation? Sequence-based methods often fail to identify functionally relevant similarities when sequence identity is low (typically below 25-30%) [11]. Local sequence homology does not guarantee similarity at the fold or domain level, which are more reliable indicators of function [11]. For accurate functional prediction, especially with remote homologs, structural alignment is superior.

Q2: How do tools like AlphaFold and Phyre2.2 address the template identification problem in homology modeling? These tools leverage deep-learning-predicted protein structures to overcome the lack of experimental templates [11] [1]. Phyre2.2 enhances traditional homology modeling by identifying the most suitable AlphaFold model from databases to use as a template, providing an accessible interface for researchers [1].

Q3: What are uPE1 proteins, and why is their functional annotation challenging? uPE1 proteins are identified human proteins that currently lack any functional annotation [11]. They are often "evolutionarily young genes" and tend to express only in very limited tissues or specific conditions, making them difficult to study in common biological models [11]. Structural alignment strategies like AlphaFun have been key to proposing initial functional annotations for them [11].

Q4: My structural alignment for a suspected enzyme returned a high TM-score but unclear functional insights. What should I check? A high TM-score indicates strong global structural similarity [11]. However, function is often determined by local substructures like active sites. Use a specialized substructure alignment tool like PLASMA, which is designed to identify and compare local functional motifs (e.g., catalytic residues, binding pockets) that might be embedded within different overall folds [12].

Q5: What are the key differences between global and local structural alignment methods?

The table below summarizes the core differences and applications of these approaches.

| Feature | Global Alignment | Local (Substructure) Alignment |

|---|---|---|

| Comparison Focus | Overall 3D structure and fold [12] | Specific, local functional motifs (e.g., active sites) [12] |

| Primary Metric | TM-score [11] | Residue-level similarity score (e.g., from PLASMA) [12] |

| Best For | Identifying homologous proteins, general function prediction [11] | Pinpointing functional mechanisms, engineering specific sites, drug target identification [12] |

| Tool Examples | TM-Align [11] | PLASMA [12] |

Q6: How can I validate the quality of a protein model generated via template-based modeling? Cross-validate your model using multiple methods. If you used a template-based server like Phyre2.2, also run a deep learning-based predictor like AlphaFold2 or ESMFold on the same sequence [1]. Compare the key functional domains and active site geometries between the different models. Significant consensus increases confidence, while major discrepancies require further investigation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor or No Significant Hits in Template Search

Problem: Your query sequence returns no viable templates or templates with very low sequence identity during a homology modeling search.

Solutions:

- Utilize Deep-Learning Structures: If no experimental template is found, use a deep-learning predicted structure (e.g., from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database) as your template. Servers like Phyre2.2 can automate this process [1].

- Refine Your Search with HMM/HMM Matching: Move beyond simple BLAST. Use tools that employ profile hidden Markov models (HMMs) for sequence searching, such as HHblits, which can detect more remote homologies than BLASTp [1].

- Check for Domain-Level Alignment: Your protein may be multi-domain. A lack of full-length hits does not preclude the existence of templates for individual domains. Use domain segmentation tools before your template search.

Issue 2: Low Confidence in Predicted Functional Annotations

Problem: After obtaining a structural alignment, the transferred functional annotation (e.g., Gene Ontology term) seems unreliable or non-specific.

Solutions:

- Establish a Precision Threshold: Based on the AlphaFun methodology, when transferring annotations from top structural matches, use a threshold of the top 7-15 candidate proteins to generate the most accurate functional predictions [11].

- Correlate TM-Score with Precision: Higher TM-scores generally indicate better functional transfer. Analyze the precision of your annotations against the TM-score; a polynomial relationship often exists where precision increases with TM-score [11].

- Leverage Multiple Annotation Tools: Do not rely on a single pipeline. Use complementary tools like DeepFRI (which uses protein structures) or DeepGOWeb (which uses sequences) to corroborate predictions [11].

Issue 3: Inaccurate Loop or Active Site Modeling

Problem: The region of your model corresponding to an indel (insertion/deletion) in the alignment—often a loop or active site—is poorly modeled and clashes with your functional data.

Solutions:

- Investigate Alternative Template States: If your protein is in a "holo" (ligand-bound) state, ensure you are not using an "apo" (unbound) template for the critical region, and vice-versa. Phyre2.2's library includes representatives for both apo and holo structures if available [1].

- Utilize Specialized Loop Modeling: Modern homology modeling servers like Phyre2.2 use fragment-based loop modeling. They search the PDB for fragments that match the local sequence and can be sterically integrated into the template framework [1].

- Focus on Substructure Alignment: For active site issues, use a local alignment tool like PLASMA to specifically compare your model's putative active site against known enzymatic pockets to check for conservation of key residue geometries [12].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: AlphaFun Strategy for Functional Annotation

This protocol outlines a method for large-scale functional annotation of proteins, particularly those without prior annotation (uPE1), using structural alignment [11].

1. Protein Sequence and Structure Collection:

- Input: Obtain protein sequences of interest from a database like neXtProt.

- Structure Prediction: Download the corresponding predicted 3D structures in PDB format from the AlphaFold protein structure database [11].

2. Sequence Alignment and Filtering:

- Tool: BLASTp.

- Action: Perform a local BLAST alignment against a reference protein database (e.g., CCDS).

- Filtering: Remove different protein isoforms and query proteins for which BLAST returns no results or no structurally similar proteins other than itself [11].

3. Structural Alignment:

- Tool: TM-Align.

- Action: For each query protein, perform structural alignment with its BAST-identified candidate proteins to obtain TM-scores [11].

4. Functional Annotation Transfer:

- Tool: GOATOOLS and QuickGO.

- Action: Extract Gene Ontology (GO) terms for the top structural-aligned candidate proteins. These terms are used to annotate the query protein [11].

5. Validation and Precision Analysis:

- Action: Validate the pipeline's precision and recall using proteins with known functions. The number of top candidate proteins used for annotation (e.g., 7 or 15) is optimized to achieve the highest accuracy [11].

AlphaFun Functional Annotation Workflow

Protocol 2: PLASMA for Local Substructure Alignment

This protocol describes the use of the PLASMA framework for identifying and comparing local functional motifs between two protein structures [12].

1. Input Representation:

- Input: Two protein structures (Query and Candidate).

- Feature Extraction: Generate residue-level embeddings for both proteins using a pre-trained protein representation model. These embeddings capture local biochemical and structural context [12].

2. Optimal Transport-Based Alignment:

- Tool: PLASMA's Transport Planner module.

- Cost Matrix: A learnable cost matrix, computed via a siamese network, defines the pairwise similarity between all residues of the two proteins.

- Sinkhorn Iterations: The entropy-regularized optimal transport problem is solved using differentiable Sinkhorn iterations. This produces a soft alignment matrix that highlights residue-level correspondences, even for partial or variable-length matches [12].

3. Similarity Scoring:

- Tool: PLASMA's Plan Assessor module.

- Action: The alignment matrix from the previous step is summarized into a single, interpretable similarity score (κ) that reflects the overall similarity of the matched substructures [12].

PLASMA Substructure Alignment Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and databases essential for conducting structural alignment research.

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Database [11] [1] | Database | Repository of predicted protein structures | Provides high-quality predicted 3D models for template-based modeling and functional annotation when experimental structures are unavailable. |

| TM-Align [11] | Software Algorithm | Protein structural alignment | Calculates TM-scores to quantify global structural similarity between two protein 3D structures. |

| PLASMA [12] | Software Framework | Residue-level substructure alignment | Identifies and aligns local functional motifs (e.g., active sites) using optimal transport, crucial for detailed functional analysis. |

| Phyre2.2 [1] | Web Server | Template-based protein structure modeling | Facilitates easy homology modeling, including using AlphaFold models as templates, and supports batch processing of sequences. |

| HHblits [1] | Software Algorithm | Sensitive sequence homology search | Uses HMM/HMM comparisons to detect remote homologs more effectively than BLAST for template identification. |

| GOATOOLS [11] | Software Library | Gene Ontology (GO) term analysis | Processes and analyzes GO terms for functional enrichment and annotation of query proteins based on alignment results. |

| QuickGO [11] | Web Database | Online Gene Ontology browser | Used to retrieve and validate GO term information for proteins identified as top structural matches. |

Advanced Tools and Techniques for Precision Alignment

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using Phyre2.2 over the previous Phyre2 for template-based modeling?

Phyre2.2 incorporates several key enhancements. The most significant is its direct integration with the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, allowing it to identify and use suitable AlphaFold models as templates for your sequence [10] [13]. It also employs a faster HMM/HMM comparison algorithm (HHBlits) and features a redesigned template library that includes both apo and holo forms of proteins where available, providing more biologically relevant templates for studying ligand binding [1] [14].

Q2: When I run my sequence, Phyre2.2 provides multiple models spanning different domains. How should I interpret these results?

This is a feature of the new ranking system in Phyre2.2. The server analyzes results to distinguish and group models for different domains that may exist within your query sequence [14]. Instead of being presented with a single, potentially poor model that spans the entire sequence, you are shown the best possible models for each distinct domain region. You should inspect these top-ranked domain models individually, as they likely represent the most accurate structural predictions for those specific segments of your protein [13].

Q3: What is "One-to-One Threading" and when should I use it?

One-to-One Threading is a specialized mode that allows you to build a model for your sequence based on a single, user-specified template [10] [14]. Previously, this required you to supply a PDB file. Now, Phyre2.2 enables this function directly against the entire AlphaFold database. You should use this mode when you have a specific structural hypothesis you wish to test—for example, if you believe your protein adopts a fold similar to a particular AlphaFold-predicted structure or a specific experimental structure (like an apo or holo form) that you can select from the expanded template library [13] [1].

Q4: I am modeling a protein complex. Can Phyre2.2 predict quaternary structures, and how does it compare to specialized complex prediction tools?

Phyre2.2 is primarily designed for monomeric (single-chain) protein structure prediction via template-based modeling. For protein complexes (multimers), specialized methods have been developed that show superior performance. For instance, DeepSCFold, a pipeline that uses sequence-derived structural complementarity, has been shown to significantly improve the accuracy of protein complex structure prediction, achieving an 11.6% and 10.3% improvement in TM-score over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively, on CASP15 targets [6]. If your goal is to model a multi-chain complex, using a server specifically designed for multimers is recommended.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Quality Model Due to Remote or No Homology

Problem: The generated model has low confidence, poor coverage, or does not resemble expected folds, often because no closely related experimental templates exist.

Solution: Leverage Phyre2.2's integration with the AlphaFold database.

- Step 1: In a standard "Normal Mode" search, Phyre2.2 will automatically attempt to find the closest AlphaFold model at the EBI database to use as a template [13] [1]. Check your results for models labeled as based on an AlphaFold template.

- Step 2: If "Normal Mode" does not yield a satisfactory model, utilize the "One-to-One Threading" function directly with the AlphaFold DB. This allows you to align your sequence against all entries in the AlphaFold database to find the best fit for use as a dedicated template [10] [14].

- Rationale: The AlphaFold database contains over 200 million predicted structures, vastly expanding the universe of potential templates beyond experimentally solved structures in the PDB [15]. This greatly increases the probability of finding a viable template for proteins without close experimental homologs.

Issue 2: Handling Alignment Errors in Domain-Divided Results

Problem: The results page shows several good models, but each covers a different, non-overlapping part of your sequence. You need a complete model.

Solution: Manually construct a multi-domain model using the provided domain-level alignments.

- Step 1: From the results page, identify the top-performing models for each domain region. Note their respective template PDB IDs and the residue ranges they cover in your sequence.

- Step 2: Use the "Download" options to obtain the atomic coordinates for each domain model.

- Step 3: Use molecular visualization and modeling software (e.g., PyMOL, ChimeraX) to combine these domain models into a single coordinate file. Superimpose or manually orient the domains based on any available biological knowledge or predicted inter-domain contacts.

- Rationale: Phyre2.2's new ranking system highlights different domains to provide the most accurate local models [13]. In the absence of a full-length template, automatically merging these domains is non-trivial. Manual construction gives the researcher control to create a plausible composite structure, though regions connecting domains (linkers) will likely be uncertain.

Issue 3: Selecting the Appropriate Template from Multiple High-Scoring Hits

Problem: The search returns multiple templates with similarly high scores, making it difficult to choose the best one for your biological question.

Solution: Utilize Phyre2.2's enhanced template library and apply biological filters.

- Step 1: Prioritize templates based on biological relevance. Phyre2.2's library now includes separate representatives for apo (ligand-free) and holo (ligand-bound) structures if they exist in the PDB [1]. If you are studying ligand binding, select a holo template. If you are studying the unbound state, an apo template may be more appropriate.

- Step 2: Inspect the alignment details. A template with a slightly lower score but a longer alignment that covers more of your query sequence may yield a better model than one with a high score but partial coverage.

- Step 3: Cross-reference the template with external databases like the PDB or UniProt to understand its biological context (e.g., organism, known function, bound ligands), which can help you make an informed choice.

- Rationale: The "best" template is not always the one with the single highest score; it is the one that is most functionally and structurally relevant to your specific research hypothesis [13].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Benchmarking Performance of Template-Based Modeling

The table below summarizes key quantitative data from recent advancements in the field, providing a benchmark for expected performance.

Table 1: Benchmarking Data for Protein Structure Prediction Methods

| Method | Application Scope | Key Performance Metric | Result | Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSCFold [6] | Protein Complex Structure Modeling | TM-score Improvement | +11.6% over AlphaFold-Multimer | CASP15 Multimer Targets |

| DeepSCFold [6] | Protein Complex Structure Modeling | TM-score Improvement | +10.3% over AlphaFold3 | CASP15 Multimer Targets |

| DeepSCFold [6] | Antibody-Antigen Complexes | Success Rate for Interface Prediction | +24.7% over AlphaFold-Multimer | SAbDab Database |

| AlphaFold2 [16] | Monomer Structure Prediction | Average GDT_TS | >90 for ~2/3 of targets | CASP14 |

Protocol: Standard Workflow for Structure Prediction with Phyre2.2

The following diagram outlines the standard workflow for template-based structure prediction using Phyre2.2.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key digital resources and their roles in the protein structure prediction process using Phyre2.2.

Table 2: Essential Digital Resources for Template-Based Modeling with Phyre2.2

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Database [15] | Structure Database | Provides over 200 million predicted protein structures that can be used as high-quality templates when experimental structures are unavailable. |

| UniRef50 [1] | Sequence Database | Used by Phyre2.2 to generate deep multiple sequence alignments for building the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) of the query sequence. |

| HHBlits [1] [14] | Software Algorithm | Performs fast and sensitive HMM/HMM comparisons to identify remote homologies and generate accurate query-template alignments. |

| SCWRL4 [1] | Software Algorithm | Accurately predicts and places side-chain conformations (rotamers) onto the modeled protein backbone during the final stage of structure building. |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) [1] | Structure Database | The primary source of experimentally determined protein structures that form the core of Phyre2.2's template library, including curated apo/holo forms. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common NDThreader Alignment Errors

This guide addresses specific issues you might encounter during NDThreader experiments, providing solutions to ensure accurate sequence-template alignment.

Problem 1: Poor Alignment Quality on Targets with Low Homology

- Error Message/Symptom: Low alignment score and precision, especially when template structure similarity (TM-score) is below 0.55.

- Possible Cause: The initial alignment generated without distance information is of low quality, limiting the effectiveness of subsequent refinement steps. Older methods using simpler scoring functions (e.g., linear functions, shallow CNNs) struggle to capture complex relationships for distant homologs.

- Solution:

- Leverage the DRNF Module: Ensure the Deep Convolutional Residual Neural Fields (DRNF) module is activated. DRNF integrates deep ResNet with Conditional Random Fields (CRF) to capture context-specific information from sequential features (e.g., sequence profile, predicted secondary structure), leading to better initial alignments even without distance data [17] [18].

- Utilize Predicted Distance Potential: Feed accurate predicted inter-residue distance distributions of the query protein into the second module, which uses the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) and another deep ResNet to refine the DRNF-generated alignments [17] [18].

Problem 2: Suboptimal 3D Models Despite Good Alignment

- Error Message/Symptom: The final 3D model built from a sequence-template alignment is more similar to the template than to the native structure of the target protein.

- Possible Cause: Traditional model construction tools (e.g., MODELLER, RosettaCM) can over-fit the template structure.

- Solution:

- Use the Integrated Model Building Pipeline: Employ NDThreader's full workflow. It feeds the sequence-template alignment and sequence coevolution information into a deep ResNet to predict inter-atom distance/orientation distributions. This distribution is then converted to a potential and minimized through PyRosetta for 3D construction, resulting in models that are more accurate to the target protein [17] [18].

Problem 3: Inaccurate Template Selection

- Error Message/Symptom: The best structural template is not identified, leading to incorrect fold recognition.

- Possible Cause: The scoring function for template ranking is not sensitive enough for distant homology detection.

- Solution: The deep learning-based scoring function in NDThreader's DRNF module is designed to outperform methods like HHpred and CNFpred in recognizing better templates, particularly when sequence similarity is low. Confirm that the feature inputs to the DRNF (sequence profiles, etc.) are generated from high-quality multiple sequence alignments [17] [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core technological advancement in NDThreader compared to its predecessor, DeepThreader?

A: NDThreader introduces two key advancements over DeepThreader. First, it replaces the shallow convolutional neural network (CNFpred) used for initial alignment with a more powerful DRNF (Deep Convolutional Residual Neural Fields) module. DRNF combines deep ResNet and CRF to generate a superior initial alignment without using distance information. Second, it uses a more accurate predicted distance potential during the alignment refinement stage. This two-stage deep learning approach addresses the primary limitations of DeepThreader, leading to significantly improved alignment accuracy and template selection [17] [18].

Q2: How does the integration of ResNet specifically improve template-based modeling?

A: Deep Residual Networks (ResNet) allow for the training of much deeper neural networks without vanishing gradient problems. In NDThreader, ResNet is used to capture complex, context-specific patterns from input features like sequence profiles and predicted structural properties. This deep network can model the intricate relationships between a query sequence and a template far more effectively than the linear scoring functions of older methods (e.g., HHpred) or shallower neural networks, leading to more accurate alignments even for distantly related proteins [17] [18].

Q3: My research involves multidomain proteins. Can NDThreader handle this complexity?

A: While the core NDThreader paper focuses on domain-level alignment, the broader field is advancing with methods designed for multidomain challenges. For complex multidomain proteins, consider pipelines like D-I-TASSER, which incorporates a dedicated domain splitting and assembly protocol. It uses deep-learning-guided iterative threading and spatial restraints to assemble full-chain models from domain-level predictions, and has demonstrated strong performance on multidomain targets [19].

Q4: What evidence validates NDThreader's performance in blind tests?

A: NDThreader was blindly tested during the CASP14 competition as part of the RaptorX server. On the 58 template-based modeling (TBM) targets, the server achieved the best average GDT score among all participating servers. The GDT score is a key metric for assessing the global topology of predicted models, confirming the method's effectiveness in real-world, blind prediction scenarios [17] [18].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following tables summarize key experimental results demonstrating NDThreader's performance against established methods.

Table 1: Alignment Accuracy (Precision & Recall) on In-House Test Set

Performance comparison evaluated using reference-dependent precision and recall across different template similarity bins. Data adapted from [17] [18].

| TM-score Bin | CNFpred (Prec/Rec) | HHpred-local (Prec/Rec) | DRNF-MaxAcc (Prec/Rec) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (0.45, 0.55] | 0.236 / 0.240 | 0.268 / 0.118 | 0.394 / 0.353 |

| (0.55, 0.65] | 0.417 / 0.413 | 0.499 / 0.282 | 0.589 / 0.553 |

| (0.65, 0.8] | 0.628 / 0.626 | 0.673 / 0.525 | 0.757 / 0.748 |

| (0.8, 1.0] | 0.832 / 0.832 | 0.856 / 0.773 | 0.895 / 0.891 |

Table 2: Quality of 3D Models Built from Alignments

Average quality of 3D models constructed by MODELLER from alignments generated by different methods. Higher scores are better. Data from [18].

| Method | Average TM-score | Average GDT |

|---|---|---|

| CNFpred | 0.452 | 0.365 |

| HHpred-global | 0.469 | 0.381 |

| HHpred-local | 0.488 | 0.398 |

| DRNF | 0.525 | 0.432 |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating a Sequence-Template Alignment with NDThreader

Objective: To produce an accurate alignment between a target protein sequence and a structural template from the PDB.

Materials:

- Target amino acid sequence in FASTA format.

- Access to the NDThreader software or server [17].

- Library of protein structural templates (e.g., from PDB).

Methodology:

- Input & Feature Generation: Submit the target sequence. The system will automatically generate deep multiple sequence alignments and sequential features like position-specific scoring matrices (PSSMs), predicted secondary structure, and solvent accessibility.

- Initial Alignment (DRNF Module):

- The sequential features are fed into the DRNF module.

- DRNF uses a deep ResNet to extract high-level, context-specific features from the input.

- A Conditional Random Field (CRF) uses these features to compute the alignment probability and generate the initial sequence-template alignment without using distance information [17] [18].

- Alignment Refinement (ADMM Module):

- A separate deep ResNet predicts the inter-residue distance distribution for the target protein.

- The initial alignment from step 2 and the predicted distance potential are fed into an optimization procedure using the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM).

- The ADMM refines the alignment to be consistent with the predicted distance constraints, producing a final, improved alignment [17] [18].

- Output: The final sequence-template alignment is provided, which can be used for 3D model construction.

Protocol 2: Building a 3D Model from an NDThreader Alignment

Objective: To construct an all-atom 3D model of the target protein using the alignment generated by NDThreader.

Materials:

- Final sequence-template alignment from NDThreader.

- 3D coordinates of the template structure.

- Sequence coevolution information for the target (e.g., from multiple sequence alignments).

- Access to PyRosetta software [17] [18].

Methodology:

- Input Integration: The sequence-template alignment, the template structure, and the sequence coevolution information are fed into a deep ResNet.

- Distance/Orientation Prediction: The deep ResNet predicts a probability distribution for inter-atom distances and orientations for the target protein.

- Potential Conversion: The predicted probability distribution is converted into a spatial restraint potential.

- Model Construction and Refinement: The spatial potential is fed into PyRosetta. The system performs energy minimization and conformational sampling to build a 3D model that satisfies the predicted distance and orientation restraints as well as possible [17] [18].

- Output: One or more all-atom 3D models of the target protein.

Workflow and Diagnostic Diagrams

Diagram Title: NDThreader Alignment Workflow and Problem Points

Diagram Title: Diagnostic Path for Model Quality Issues

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and data resources essential for experiments in deep learning-based template modeling.

| Item Name | Function / Role in the Experiment | Specific Use Case / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| DRNF (Deep Convolutional Residual Neural Fields) | Generates context-aware sequence-template alignments. | Core NDThreader module. Integrates Deep ResNet for feature extraction and CRF for alignment probability calculation, replacing shallow CNNs [17] [18]. |

| Deep ResNet (Residual Network) | Predicts inter-residue distance distributions and structural features. | Used within multiple NDThreader stages. Its depth allows accurate prediction of complex distance potentials from coevolutionary and sequence data [17] [18]. |

| ADMM (Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers) | Optimizes and refines sequence-template alignments. | Mathematical solver used to improve the initial DRNF alignment by incorporating constraints from the predicted distance potential [17] [18]. |

| PyRosetta | Constructs and refines all-atom 3D protein models. | Used in the final NDThreader step to minimize the spatial potential derived from predicted distances/orientations, building the model [17] [18]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary repository of experimentally solved protein structures. | Serves as the essential source of structural templates for the template-based modeling process [17] [20]. |

| Deep Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) | Provides evolutionary and coevolutionary information. | Used to generate sequence profiles (PSSMs) for alignment and to derive residue coevolution signals for distance prediction [17] [19]. |

FAQs: MMseqs2-GPU Installation and Setup

Q1: What are the minimum hardware and software requirements for installing MMseqs2-GPU? MMseqs2-GPU requires an AMD or Intel 64-bit system (x86_64). For optimal performance, we recommend a system supporting at least the SSE4.1 instruction set, with AVX2 support for even faster operation [21]. The key requirement is an NVIDIA GPU of the Turing generation or newer (e.g., Ampere or Ada Lovelace architectures for full speed). You must also have the appropriate NVIDIA drivers installed (version 525.60.13 or newer) [21].

Q2: How can I install MMseqs2-GPU on a Linux system? The fastest method is to download and install the pre-compiled static binary. You can use the following commands [21]:

Alternatively, you can install it via Conda using conda install -c conda-forge -c bioconda mmseqs2 or use Docker with docker pull ghcr.io/soedinglab/mmseqs2 [21].

Q3: How do I verify that the GPU acceleration is functioning correctly after installation?

You can run a simple search test and check the output for GPU-related information. The software will typically indicate if it is using GPU resources. Furthermore, you can use the nvidia-smi command in a separate terminal while a job is running to monitor GPU utilization.

Troubleshooting Common MMseqs2-GPU Workflow Errors

Issue 1: Input database has the wrong type error when running result2msa

- Problem Description: After running

mmseqs search, the tool generates multiple result files (e.g.,result.0,result.1). A subsequentmmseqs result2msacommand fails with an error: "Input database has the wrong type (Generic)" [22]. - Root Cause: The

result2msamodule requires a specific database format that is not directly produced by thesearchcommand. Thesearchcommand outputs a generic result format. - Solution: You must first convert the search results into an alignment database format using the

mmseqs alignmodule before runningresult2msa. The correct workflow sequence is [22]:mmseqs createdb query.fasta qdbmmseqs search qdb targetDB result tmpmmseqs align qdb targetDB result result_ali// <- Critical conversion stepmmseqs result2msa qdb targetDB result_ali result_msa

Issue 2: Low GPU utilization or out-of-memory errors during large database searches

- Problem Description: The job runs slowly, and system monitoring shows low GPU usage, or it fails with a memory error.

- Root Cause: The target database may be too large to fit into the GPU's memory, or the system's available RAM may be insufficient for pre-processing.

- Solution:

- MMseqs2-GPU automatically handles databases that exceed GPU memory by streaming data from the host's RAM. Ensure your system has adequate free RAM [23] [24].

- The memory footprint has been significantly reduced in the GPU version to about 1 byte per target residue [23] [24]. For very large searches, you can use the

--split-memory-limitparameter to control memory usage [21]. - If using multiple GPUs, you can control which GPUs are used with the

CUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICESenvironment variable [21].

Performance Benchmarks and Configuration Guide

The integration of GPU acceleration in MMseqs2 delivers substantial performance improvements. The table below summarizes key benchmark results for homology search and structure prediction workflows.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of MMseqs2-GPU vs. CPU-based Tools

| Metric | Comparison | Experimental Setup |

|---|---|---|

| Homology Search Speed | 177x faster than JackHMMER, 6.4x faster than BLAST on a single NVIDIA L40S GPU [23] [24] [25]. | Single query against a ~30-million-sequence database [23] [24]. |

| Cost Efficiency | 71x cheaper for protein searches on a single L40S GPU vs. a 128-core CPU setup [26]. | Cloud cost estimates based on AWS EC2 pricing [23] [24]. |

| Throughput (Prefiltering) | Up to 100 TCUPS (Trillions of Cell Updates Per Second) across eight GPUs [26] [23]. | Gapless filtering algorithm on NVIDIA L40S GPUs [26]. |

| Structure Prediction (End-to-End) | 31.8x faster than standard AlphaFold2 (JackHMMER+HHblits) pipeline [23] [24]. | ColabFold with MMseqs2-GPU on 20 CASP14 targets [23] [24]. |

| Memory Requirement | Reduced from ~7 bytes to ~1 byte per residue for target databases [23] [24]. | Measurement of memory footprint during database search [23] [24]. |

To achieve optimal results, the sensitivity parameter (-s) is critical. The table below provides a guide for configuring this parameter.

Table 2: Configuring MMseqs2 Search Sensitivity for Your Experiment

Sensitivity (-s) |

Use Case | Impact on Speed & Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0 - 3.0 | Very fast searches for highly similar sequences, initial data screening [21]. | Highest speed, lower sensitivity. |

| 4.0 - 5.0 | Standard balanced search for routine homology detection [21]. | Balanced speed and sensitivity. |

| 6.0 - 7.5 | Very sensitive searches for detecting remote homologs in template-based modeling [21]. | Highest sensitivity, slower speed. Essential for difficult targets. |

| Iterative Profile Search | Maximum sensitivity, approaching the performance of JackHMMER [23] [24]. | 3 iterations achieved ROC1 of 0.669 (vs. JackHMMER's 0.685) [23] [24]. |

Experimental Protocol: Accelerated MSA Generation for Template-Based Modeling

This protocol details the steps for generating high-quality Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) using MMseqs2-GPU, a critical step for template-based protein structure modeling.

Objective: To rapidly generate a sensitive MSA from a query protein sequence against a large reference database (e.g., UniRef90) using GPU acceleration.

Principal Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the core steps of the GPU-accelerated MMseqs2 search and alignment process.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Software and Database Setup

- Install MMseqs2-GPU following the FAQs in Section 1.

- Download and set up a target sequence database (e.g., UniRef90). This can be done manually or using the

databasesworkflow [21]:mmseqs databases UniRef90 uniref90_db tmp_path

Create Input Databases

- Convert your query protein sequence(s) from FASTA format to an MMseqs2 database:

mmseqs createdb query.fasta queryDB - Ensure the target database is also in the MMseqs2 format.

- Convert your query protein sequence(s) from FASTA format to an MMseqs2 database:

Execute GPU-Accelerated Search

- Run the main search command. Use a high sensitivity (

-s 7.5) for detecting remote homologs critical for template-based modeling.mmseqs search queryDB targetDB resultDB tmp -s 7.5 --gpu--gpu: Flag to enable GPU acceleration.-s 7.5: Sets high sensitivity for remote homology detection.- The

tmpdirectory holds temporary files.

- Run the main search command. Use a high sensitivity (

Generate Alignments and MSA

- Critical Step: Convert the search results into alignments.

mmseqs align queryDB targetDB resultDB alignDB tmp - Generate the final MSA in A3M format:

mmseqs result2msa queryDB targetDB alignDB resultMSA

- Critical Step: Convert the search results into alignments.

Output and Validation

- The final output

resultMSAcontains the MSA. You can unpack it to a readable file usingmmseqs unpackdb resultMSA msa_output_dir --unpack-name-mode 1. - Validate the MSA by checking the number of aligned sequences and the presence of diverse homologs, which is a key indicator of alignment quality for downstream structure prediction.

- The final output

Table 3: Key Resources for GPU-Accelerated Sequence Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| MMseqs2 Software Suite [21] | Open-Source Software | Core program for fast and sensitive sequence search and clustering. The GPU module is integrated into this suite. |

| UniRef90 Database [21] | Protein Sequence Database | A comprehensive, clustered non-redundant protein sequence database commonly used as the target for sensitive homology searches. |

| NVIDIA L40S / L4 / A100 / H100 GPU [26] [23] [25] | Hardware (Accelerator) | Graphics Processing Units that provide the massive parallel computation needed to accelerate the gapless filtering and alignment algorithms. |

| NVIDIA CUDA Toolkit | Software Platform | A parallel computing platform and programming model that allows developers to leverage NVIDIA GPUs for general-purpose processing. Essential for running MMseqs2-GPU. |

| ColabFold [23] [25] | Integrated Workflow | A popular protein structure prediction pipeline that integrates MMseqs2 for fast MSA generation and AlphaFold2/OpenFold for folding. |

This guide provides a structured workflow for template-based protein structure modeling, a computational method to predict a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence by using evolutionarily related proteins with known structures as templates [7]. This process is crucial for functional characterization of proteins, as structural insights are highly valuable in determining their biological roles [27]. The workflow is framed within a thesis research context focused on identifying and addressing alignment errors, a primary source of inaccuracy in comparative modeling [7].

The following diagram outlines the core steps of the template-based modeling workflow, from initial sequence analysis to the final refined model.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Template Identification & Selection

Q1: I cannot find a suitable template for my target sequence. What should I do?

- Check Search Parameters and Methods: If simple BLAST searches fail, use more sensitive profile-based methods like PSI-BLAST, HHpred, or threading-based tools like RaptorX that can detect distant homologs by integrating secondary structure predictions and other nonlinear scoring functions [27] [7].

- Lower Sequence Identity Threshold: While a sequence identity above 30% is desirable, templates with lower identity (e.g., 20-30%) can sometimes be used, but expect lower model accuracy. RaptorX is specifically designed to handle remote templates [27] [28].

- Consider Multi-Domain Proteins: If your target is a large, multi-domain protein, you may need to find different templates for individual domains. Use domain parsing tools (like those integrated in RaptorX) to split the sequence before searching [27].

- Explore Updated Databases: Ensure you are searching the most current version of the PDB. Some servers, like Phyre2.2, now also include the vast AlphaFold Database as a source of potential template models [13].

Q2: Multiple potential templates are available. How do I choose the best one?

Your choice of template should be guided by the intended application of your model. Consider the following criteria, which can be prioritized differently depending on your goal (e.g., studying ligand binding vs. overall fold).

Table: Key Criteria for Template Selection

| Criterion | Description | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Identity | Percentage of identical amino acids in the alignment. | Higher sequence identity (>30%) generally leads to more accurate models [28]. |

| Coverage | The fraction of your target sequence that can be aligned to the template. | Maximizing coverage ensures more of your target is modeled. Prefer templates covering >70% of the sequence [29]. |

| Experimental Method & Resolution | Quality of the template structure (e.g., X-ray resolution in Å, NMR, Cryo-EM). | Prefer high-resolution X-ray structures (<2.0 Å) for higher local accuracy [29]. |

| Biological Context | Presence of bound ligands (holo-form), correct oligomeric state, or similar biological environment. | Essential for modeling protein-ligand interactions or protein complexes. Apo vs. holo forms can have significant conformational differences [13] [29]. |

| Global Model Quality Estimate (GMQE) | A composite score provided by servers like SWISS-MODEL that predicts model reliability. | A higher GMQE (closer to 1) indicates a potentially better overall model [29]. |

Alignment and Model Building

Q3: The target-template alignment has low identity in a critical region (e.g., active site). How can I improve it?

- Manual Curation: Automatically generated alignments are a common source of error. Visually inspect the alignment, especially around known functional residues. Use tools like T-COFFEE or MUSCLE for more refined multiple sequence alignments [7].

- Incorporate Secondary Structure Information: Use predicted secondary structure of your target (from tools like PSIPRED) to guide the alignment. Ensure that aligned regions are consistent in their secondary structure type (e.g., helix-to-helix) with the template [7].

- Use Advanced Servers: Servers like RaptorX employ Conditional Random Fields (CRFs) and multiple-template threading (MTT) to generate more accurate alignments for distantly related templates, which can partially correct errors in pairwise alignments [27].

Q4: My initial model has poor loop regions. How can I refine them?

- Dedicated Loop Modeling: Use specialized tools like MODLOOP or ArchPRED to rebuild loops with poor geometry. These tools use conformational sampling and scoring to identify more physically realistic loop structures [7].

- Ab Initio Fragment Assembly: For very long loops (>10 residues), standard loop modeling may fail. Consider using ab initio or fragment-based methods to model these regions, as implemented in composite pipelines like I-TASSER [27] [30].

Model Quality Assessment and Refinement

Q5: How can I objectively assess the quality of my generated model?

Always use independent model quality assessment tools that were not involved in the building process. The following table summarizes key metrics and tools.

Table: Essential Checks for Model Quality Assessment

| Check | Tool Examples | Interpretation of Results |

|---|---|---|

| Stereochemical Quality | PROCHECK, MolProbity | Checks bond lengths, angles, and dihedral angles (Ramachandran plot). A good model will have >90% of residues in the favored regions of the Ramachandran plot. |

| Fold/Global Reliability | QMEAN, ProSA-web | Compares your model's statistical properties to high-resolution experimental structures. A high QMEAN score or a ProSA Z-score within the range of native structures indicates a correct overall fold [29]. |

| Local/Residue-wise Error | QMEAN, Verify3D | Identifies local regions (e.g., specific loops or segments) that are potentially poorly modeled. Residues with low scores require further inspection and refinement [7] [29]. |

| Physical Plausibility | WHAT IF, ANOLEA | Analyzes atomic contacts and interaction energies to detect unrealistic atomic clashes or unfavorable interactions [7]. |

Q6: The model quality assessment tool flags a region as low-quality, but the alignment looks correct. What is the next step?

- Investigate Local Strain: The poor score might result from steric clashes or unfavorable torsion angles in the initial model. Use energy minimization with a molecular mechanics force field to relieve local strain without significantly altering the overall structure.

- Consider Alternative Templates for a Segment: If a specific region (e.g., a single loop) consistently scores poorly, it might be misaligned. Try building a hybrid model using a different, more suitable template for that particular region, if available.

- Functional Validation: If the region is part of a known active site, check if the residues are oriented in a chemically plausible way for catalysis or binding. A model that is structurally imperfect but functionally coherent may still be useful for generating hypotheses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Digital Reagents for Template-Based Modeling

| Resource Type | Example(s) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Search & Alignment | BLAST, PSI-BLAST, HHblits, MUSCLE, T-COFFEE | Identify homologous sequences and build multiple sequence alignments for profile creation [7]. |

| Template Search Servers | HHpred, Phyre2, RaptorX, SWISS-MODEL | Identify suitable structural templates from the PDB using sequence profiles, hidden Markov models, or threading [27] [7] [13]. |

| Structure Modeling Software | MODELLER, SWISS-MODEL, I-TASSER, RaptorX | Build 3D atomic models based on the target-template alignment [7] [30]. |

| Specialized Modeling Tools | SCWRL, MODLOOP | Perform specific modeling tasks like side-chain placement and loop modeling [7]. |

| Quality Assessment Servers | QMEAN, ProSA-web, PROCHECK | Evaluate the geometric and thermodynamic plausibility of the generated models [7] [29]. |

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold Database (AFDB) | Repositories of experimentally determined and predicted protein structures used for template identification [13] [31]. |

Diagnosing and Resolving Common Alignment Pitfalls

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What defines a "low-quality" alignment in template-based modeling? A low-quality alignment is one that, when used to build a 3D model, produces a structure with significant deviations from the native experimental structure. This is often quantified by a low MaxSub score, which measures the fraction of a model's Cα atoms that can be superimposed on the corresponding atoms in the native structure [32]. Such alignments typically result from using non-optimal alignment parameters or from attempting to align a query sequence to a template that is only distantly related.

Q2: Why can't I just use the default parameters in my alignment software? There is no universal alignment parameter option (such as a single best gap penalty) that always generates the optimal alignment for every unique pair of a query and a template protein [32]. The accuracy of sequence alignment can vary significantly depending on the choice of these parameters. Using a one-size-fits-all approach can lead to suboptimal models, especially for targets with lower sequence identity to available templates.

Q3: What are the key warning signs of a problematic alignment? Key warning signs include a low predicted alignment quality score [32], a high degree of variability or inconsistency between alternative alignments generated from different templates or methods [33], and the presence of steric clashes or unnatural bond lengths in the preliminary model built from the alignment [33].

Q4: How can I proactively check my alignment quality before full model building? You can employ machine learning-based prediction methods, such as Support Vector Regression (SVR) models, which are trained to predict alignment quality (e.g., MaxSub scores) based on features derived from the profile-profile alignment and the query length [32]. Additionally, generating a population of alternative alignments and checking for consistent regions can help identify unreliable alignment segments before committing to a full model building cycle [33].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Alignment Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Predicted Quality Score | Non-optimal alignment parameters; Poor template choice. | Use adaptive parameter selection [32]; Re-evaluate template suitability [32]. |

| Inconsistent Alternative Alignments | Low sequence identity; Ambiguous alignment regions. | Use clique-finding to mix/match reliable segments [33]; Employ consensus methods [32]. |

| Steric Clashes in Preliminary Model | Alignment errors in core regions; Incorrect loop modeling. | Graph-theoretic clash detection [33]; Use specialized loop modeling software [33]. |