Advanced Strategies for Refining Low-Quality Structural Models in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the latest computational strategies for refining low-quality protein structural models, a critical step in drug discovery and functional analysis.

Advanced Strategies for Refining Low-Quality Structural Models in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the latest computational strategies for refining low-quality protein structural models, a critical step in drug discovery and functional analysis. It covers foundational concepts, cutting-edge methodologies including AI-enabled quantum refinement and memetic algorithms, practical troubleshooting for common optimization challenges, and rigorous validation techniques. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes recent advances to empower readers in transforming initial predictive models into high-fidelity, reliable atomic structures.

Understanding Structural Refinement: Bridging the Sequence-Structure Gap

The Critical Role of Refinement in Modern Structural Biology

Troubleshooting Guides

My AlphaFold2 predicted model does not fit the experimental electron density. What should I do?

Problem: An AI-predicted model, while accurate in overall fold, shows regions of poor fit to experimental electron density maps from X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM.

Solution:

- Use the AI model for Molecular Replacement (MR): AlphaFold2 (AF2) models can be used as a starting point for molecular replacement to solve the experimental phase problem. The AF2 model provides phases that are often sufficiently accurate to generate an initial electron density map [1].

- Iterative Model Refinement: Manually rebuild the poorly fitting regions in software like Coot by aligning the protein backbone and side chains with the experimental density. Common areas requiring adjustment include flexible loops and side-chain rotamers.

- AI-Driven Refinement: Employ newer AI-enabled quantum refinement tools. These use machine-learned interatomic potentials to mimic quantum mechanical electron distributions, improving chemical geometry at a lower computational cost than traditional methods [2].

- Validate the Final Model: Ensure the refined model stereochemistry is within expected ranges using validation tools like MolProbity.

Experimental Protocol:

- Step 1: Use the AF2 predicted model as a search model in a MR program like Phaser.

- Step 2: Run an initial round of automated refinement using phenix.refine or REFMAC.

- Step 3: Inspect the resulting 2mFo-DFc and mFo-DFc maps in Coot. Identify regions with poor fit (clipped or negative difference density).

- Step 4: Manually rebuild these regions. For loops, use the "Loop Fit" tool. For side chains, rotate to match density.

- Step 5: Conduct multiple rounds of refinement and validation until the model agrees with the density and meets validation standards.

My cryo-EM map has low resolution in a specific protein region. How can I improve it?

Problem: A localized region of your protein (e.g., a flexible domain) appears blurry or poorly resolved in a cryo-EM reconstruction, hindering accurate model building.

Solution:

- Focused Classification and Refinement: Use 3D classification tools in RELION or cryoSPARC to isolate and remove particles where the region of interest is disordered. This focuses refinement on a more homogeneous subset of particles, potentially improving resolution for that region [3].

- Employ Deep Learning Particle Pickers: Tools like CryoPPP use expert-curated micrographs to train deep learning models for improved particle picking, which can enhance the overall quality of the dataset used for reconstruction [2].

- Ligand or Antibody Stabilization: If the flexible region is a binding domain, co-incubate the protein with a ligand or a stabilizing antibody fragment (Fab) before grid preparation. This reduces conformational flexibility, leading to a more ordered structure [1].

- ML-Enhanced Density Modification: Apply machine learning-enhanced density modification workflows, which are now part of cryo-EM map interpretation and can help in improving map quality and interpretability [2].

Experimental Protocol:

- Step 1: Perform a 3D variability analysis (3DVA) in cryoSPARC or multi-body refinement in RELION to identify the flexible region.

- Step 2: Run a 3D classification without alignment, masking the flexible region. Select classes where the density for this region is best defined.

- Step 3: Refine the selected particle subset to generate a new, higher-resolution map.

- Step 4: Rebuild the model into the improved map. If the map does not improve, consider expressing a truncated construct or using a stabilizing binding partner.

How can I handle an Intrinsically Disordered Protein (IDP) for structural studies with NMR?

Problem: IDPs are highly sensitive to proteolysis, difficult to quantify, and their lack of stable structure presents challenges for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) characterization.

Solution:

- Optimize Protein Expression and Handling:

- Use Rich Media for Growth: To increase yield of isotopically labeled protein, grow cells in rich media to high density, then transfer to minimal media for induction [4].

- Add Protease Inhibitors: Always include a cocktail of protease inhibitors during purification to prevent degradation.

- Use Denaturing Conditions: IDPs can be purified under denaturing conditions (e.g., urea or guanidine hydrochloride) without the need for refolding [4].

- Choose the Right NMR Experiments:

- Start with a ( ^{15}N )-heteronuclear single quantum coherence (( ^{15}N )-HSQC) experiment. While useful, be aware that IDPs can have poor chemical shift dispersion.

- For superior results, use the CON series of experiments (e.g., CON, (H)CA(CO)N), which are better suited for disordered proteins [4].

- Supplement with Cross-linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS): XL-MS is highly effective for challenging systems like IDPs. It provides distance restraints that can identify interacting regions and help define the structural ensemble under native conditions [3].

Experimental Protocol:

- Step 1 (Cloning): Consider codon optimization for expression in E. coli and use a fusion tag to improve solubility.

- Step 2 (Expression): Use the Marley et al. method for labeled protein expression [4].

- Step 3 (Purification): Purify using ion exchange or size exclusion chromatography under denaturing conditions if necessary.

- Step 4 (NMR): Acquire a ( ^{15}N )-HSQC followed by CON experiments for backbone assignment.

My membrane protein is unstable and will not crystallize. What are my options?

Problem: Integral membrane proteins (IMPs), such as GPCRs, are often unstable when solubilized and resist crystallization for X-ray studies.

Solution:

- Switch to Cryo-EM: Cryo-EM has become the method of choice for many IMPs as it requires only a small amount of protein and no crystallization. It has demonstrated success rates as high as 86% for IMP drug discovery projects [1].

- AI-Driven Protein Engineering: Use AI algorithms to design soluble, functional analogs of IMPs. These analogs maintain a similar fold but have hydrophilic surfaces, making them amenable to crystallization and X-ray analysis [1].

- Employ Rigid Antibody Fragments: For cryo-EM studies of small IMPs (<50 kDa), stabilize the protein by binding "Rigid-Fabs" (disulfide-constrained antibody fragments). This limits conformational flexibility and enables high-resolution structure determination [1].

- Use Lipidic Mesophases: If pursuing crystallography, use lipidic cubic phase (LCP) methods to crystallize the protein in a more native lipid environment.

Experimental Protocol for Cryo-EM:

- Step 1: Solubilize and purify the membrane protein in a suitable detergent or nanodisc.

- Step 2: Perform grid optimization by screening different detergents, lipids, and freezing conditions.

- Step 3: Collect a large dataset of micrographs automatically.

- Step 4: Process the data (particle picking, 2D/3D classification, refinement) to generate a 3D reconstruction.

- Step 5: Build and refine an atomic model into the cryo-EM density map.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single biggest recent advancement impacting model refinement? The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly AlphaFold2, has revolutionized refinement. AI-predicted models provide highly accurate starting points for Molecular Replacement, effectively solving the phase problem in crystallography and cryo-EM and dramatically accelerating the refinement process [2] [1].

Q2: My model has good R-work/R-free factors but the geometry of a co-factor is poor. How can I fix this? This is a common issue where the force fields used in refinement may not perfectly describe non-protein atoms. Use an AI-enabled quantum refinement tool. These methods use machine-learned interatomic potentials to provide improved chemical geometry for ligands and co-factors at a feasible computational cost [2].

Q3: Are there specific refinement challenges for cryo-EM structures compared to crystal structures? Yes. While cryo-EM avoids the need for crystallization, it can suffer from resolution anisotropy, where the map resolution is not uniform in all directions. This requires careful local refinement and validation. Additionally, model bias can be a significant issue; tools that use experimental maps to improve multiple sequence alignments in generative models can help avoid prediction errors during building and refinement [2].

Q4: How can I refine a structure for a protein-protein complex? Beyond standard refinement, Cross-linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS) is a powerful technique. It provides distance restraints that identify which proteins are interacting and their binding regions, which is crucial for validating and refining the interfaces in a complex [3]. For prediction, AlphaFold-Multimer can be used to screen potential protein-protein interactions [1].

Quantitative Data on Structural Biology Techniques

The following table summarizes the key metrics, strengths, and limitations of the major structural biology techniques, particularly in the context of refinement.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Structural Biology Techniques for Model Refinement

| Technique | Typical Resolution Range | Key Strengths for Refinement | Key Limitations & Refinement Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography [3] | Atomic (~1-3 Å) | - Well-established, high automation.- Fast data processing.- High-throughput (HT) approaches available. | - Requires crystallization, which can alter native structure.- Difficult for membrane proteins and dynamic complexes.- Has a "phase problem". |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) [3] [1] | Near-atomic to atomic (1.5-4 Å) | - No crystallization needed.- Preserves native states.- Ideal for large complexes & membrane proteins.- Can resolve heterogeneous states via 3D classification. | - Expensive instrumentation and data storage.- Arduous sample preparation (vitrification).- Size limitations for small proteins (<50 kDa) without stabilization. |

| NMR Spectroscopy [3] | Atomic (for local structure) | - Studies proteins in solution under near-native conditions.- Provides unique insights into dynamics and flexibility.- No phase problem. | - Low sensitivity; requires isotopic labeling.- Size limitation for solution NMR.- Expensive instrumentation and maintenance. |

| Cross-linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS) [3] | Low resolution (Restraint-based) | - Works under physiological conditions.- No size limit.- Provides powerful distance restraints for validating models and complexes.- Excellent for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs). | - Does not generate a 3D structure on its own.- Requires integration with other techniques (e.g., docking, MD).- Resolution is limited by the cross-linker length. |

| AI/ML Prediction (e.g., AlphaFold) [2] [1] | Varies (Near-atomic for many targets) | - Provides high-quality models in minutes/hours.- Solves the molecular replacement phase problem.- Enables construct design and optimization. | - Accuracy can be lower for regions with few homologous sequences.- May not capture ligand-induced conformational changes.- Dynamics and allostery are not directly predicted. |

Experimental Workflows for Model Refinement

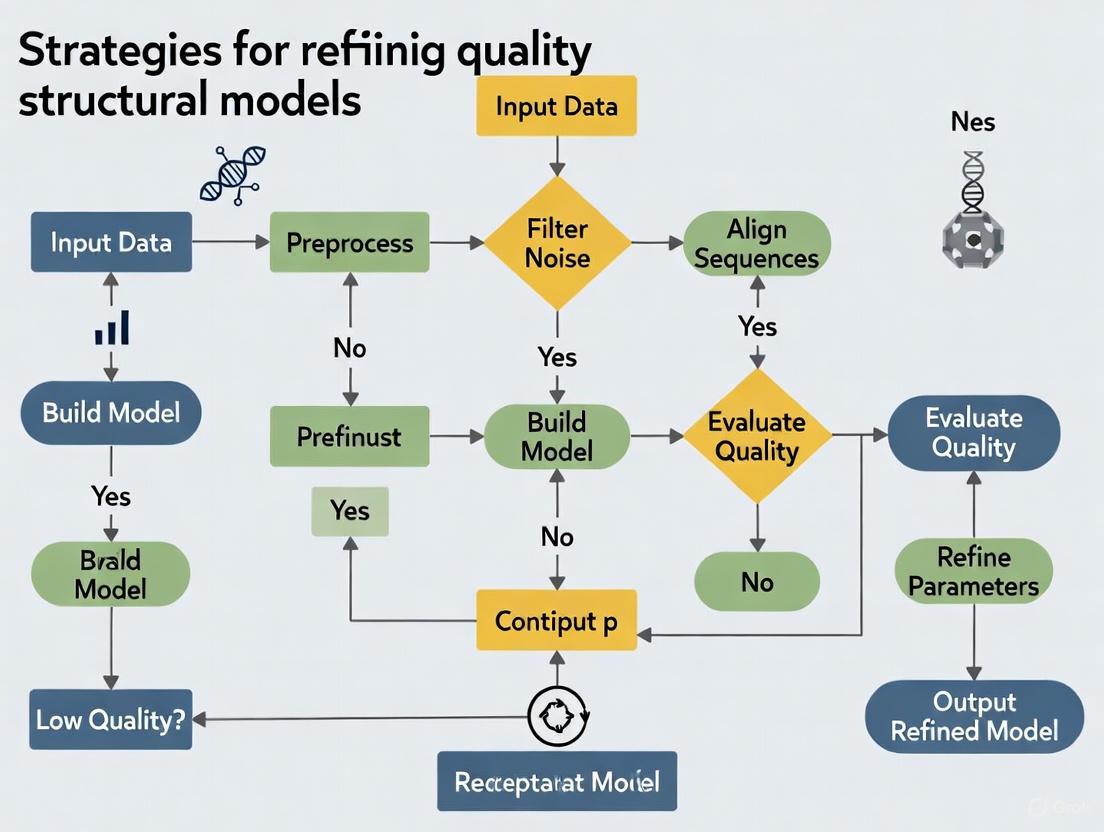

The following diagrams illustrate standard and modern AI-integrated workflows for structural refinement.

Generic Workflow for Experimental Model Refinement

Workflow for Experimental Model Refinement

AI-Integrated Refinement Workflow

AI-Integrated Refinement Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Structural Biology Refinement

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-labeled Nutrients | Enables NMR spectroscopy of proteins by incorporating detectable nuclei (( ^{15}N ), ( ^{13}C )). | ( ^{15}NH_4Cl ) as a nitrogen source in M9 minimal media [4]. |

| Cross-linking Reagents | Provides distance restraints for structural modeling and validation of complexes via XL-MS. | BS3 (bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate) is a common amine-reactive cross-linker [3]. |

| Cryo-EM Grids | Supports the vitrified sample for imaging in the cryo-electron microscope. | Quantifoil or C-flat grids with ultra-thin carbon film. |

| Detergents & Lipids | Solubilizes and stabilizes membrane proteins for crystallization or cryo-EM. | DDM (n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside), LMNG (lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol), Nanodiscs. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevents proteolytic degradation of sensitive proteins (e.g., IDPs) during purification [4]. | Commercial tablets or solutions containing inhibitors for serine, cysteine, aspartic, and metalloproteases. |

| Rigid Fabs | Stabilizes small or flexible proteins for high-resolution structure determination by cryo-EM [1]. | Disulfide-constrained antibody fragments that limit conformational flexibility of the target protein. |

| AI/ML Software Suites | Predicts protein structures, assists in model refinement, and improves experimental data processing. | AlphaFold2/3, RoseTTAFold, ProteinMPNN, CryoPPP, and various ML-enhanced refinement tools [2] [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common types of flaws found in low-quality protein structural models? Low-quality protein models typically exhibit two primary categories of flaws. The first involves backbone inaccuracies, where the main chain trace of the protein is incorrect, leading to a high Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) from the native structure. The second common flaw involves side-chain collisions, where the atoms of amino acid side chains are positioned too close together, resulting in steric clashes and unrealistic atomic overlaps that violate physical constraints [5] [6].

Q2: Why is structure refinement particularly challenging for protein complexes compared to single-chain proteins? Refining protein complexes is more difficult because it requires correcting conformational changes at the interface between subunits without adversely affecting the already acceptable quality of the individual subunit structures. Methods that allow backbone movement risk increasing the interface RMSD, while conservative, backbone-fixed methods focusing only on side-chains may be insufficient for correcting larger interfacial errors [5].

Q3: How can I assess the quality of a refined protein model? Quality assessment uses multiple metrics. The fraction of native contacts (fnat) is a straightforward metric for interface quality in complexes. For backbone accuracy, the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is used, though it is difficult to improve via refinement. Steric clashes are evaluated using tools like the MolProbity clashscore, and overall model quality can be checked with Ramachandran plot analysis and statistical potentials [5] [7] [8].

Q4: My refinement protocol made the side-chains worse. What could have gone wrong? This can occur if the refinement method's energy function or sampling protocol is inadequate. Over-aggressive optimization without proper restraints can lead to side-chain atoms becoming trapped in unrealistic, high-energy conformations or creating new collisions. Using more conservative protocols, applying restraints, or trying a method specifically designed for side-chain repacking like SCWRL or OSCAR-star may yield better results [5].

Q5: Are machine learning methods useful for protein structure refinement? Yes, machine learning is an emerging and powerful tool for refinement. Deep learning frameworks can predict per-residue accuracy and distance errors to guide refinement protocols [6]. Other methods use graph neural networks to directly predict refined structures or estimate inter-atom distances to guide conformational sampling, showing promise in improving both backbone and side-chain accuracy [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Backbone RMSD After Refinement

Description The overall fold or the interface backbone of your model has deviated further from the correct native structure after a refinement procedure.

Diagnosis Steps

- Quantify the Problem: Calculate the global and interface RMSD of your refined model against a known native structure (if available) or a trusted reference model.

- Check Method Type: Determine if you used a backbone-mobile method (e.g., Galaxy-Refine-Complex, PREFMD) or a backbone-fixed method (e.g., Rosetta FastRelax, SCWRL). High RMSD increases are more common with backbone-mobile methods [5].

- Verify Restraints: Check if your refinement protocol allowed for excessive backbone movement without applying sufficient restraints to preserve the overall fold.

Solution

- For critical applications where the initial backbone placement is already good, consider switching to a backbone-fixed refinement method that only repositions side-chains. This prevents the backbone from moving in a wrong direction [5].

- If backbone adjustment is necessary, use methods that incorporate restrained molecular dynamics or evolutionary algorithms for better conformational sampling. Memetic algorithms that combine global search with local optimization can better sample the energy landscape without drastic deviations [6].

- Implement multi-objective optimization strategies that simultaneously optimize different energy functions (e.g., RWplus, Rosetta, CHARMM) to maintain a balance between various structural quality metrics [6].

Problem: Steric Clashes and Side-Chain Collisions

Description The refined model shows atomic overlaps where non-bonded atoms are positioned closer than their van der Waals radii allow, leading to high energy and unstable structures.

Diagnosis Steps

- Identify Clashes: Use validation software like MolProbity to generate a clashscore and visualize specific atomic collisions in a molecular viewer [7].

- Analyze Location: Determine if clashes are localized at the protein-protein interface or scattered throughout the core. Interface clashes are common in unrefined docking models [5].

Solution

- Employ refinement methods with explicit repulsion energy terms (e.g., the

fa_repterm in Rosetta's Ref2015 energy function) that actively penalize atomic overlaps [6]. - Use dedicated side-chain repacking tools like SCWRL or OSCAR-star, which are designed to place side-chains in rotameric conformations that avoid steric clashes [5].

- For persistent clashes, run short cycles of combined side-chain perturbation and restrained relaxation, as implemented in protocols like Galaxy-Refine-Complex [5].

Problem: Refinement Worsens Model Quality Metrics

Description After refinement, key quality metrics like the fraction of native contacts (fnat) decrease, or the model fails a greater number of validation checks.

Diagnosis Steps

- Compare Pre- and Post-Refinement: Systematically calculate a set of quality metrics (fnat, RMSD, clashscore, Ramachandran outliers) for both the initial and refined model.

- Benchmark Method Performance: Consult literature to understand the strengths and weaknesses of your chosen refinement method. Some methods are more adept at improving fnat but may struggle with backbone-dependent metrics like RMSD [5].

Solution

- If the initial model is of high quality, a conservative refinement that primarily optimizes side-chains is often the safest choice to retain the model's merits [5].

- For lower-quality starting models, consider ensemble refinement, where multiple refinement methods are applied, and the best output is selected based on a combination of energy scores and quality metrics [8].

- Utilize quality assessment programs (MQAPs) like GOBA or ProQ that can evaluate the compatibility between the model and the expected protein function or sequence to select the most plausible refined structure [8].

Problem: Refinement of Large Protein Complexes Fails

Description The refinement protocol crashes, produces errors, or yields unrealistic models when applied to multi-chain protein complexes.

Diagnosis Steps

- Check System Size: Large complexes can be computationally prohibitive for some methods. Check the limitations of the software.

- Inspect Subunit Interfaces: Ensure that the initial positioning of the subunits is physically plausible before refinement.

Solution

- For very large complexes, extract a smaller subcomplex containing the key interfaces of interest for refinement, as was done for a homo decamer in a CAPRI benchmark study [5].

- Use refinement methods specifically designed for complexes, such as those incorporating Equivariant Graph Refiner (EGR) models, which can handle the interdependent movements of multiple chains [6].

- Apply interface-specific restraints during refinement to maintain the correct relative orientation of subunits while allowing for flexibility at the interaction surface.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Performance of Refinement Method Categories on Common Flaws

| Method Category | Example Protocols | Strengths | Weaknesses | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone-Mobile | Galaxy-Refine-Complex [5], PREFMD [5], CHARMM Relax [5], Memetic Algorithms (Relax-DE) [6] | Can correct backbone inaccuracies; improves structural flexibility and fnat [5] [6] | High risk of increasing backbone RMSD; computationally intensive [5] | Low-quality models with significant backbone deviations; initial sampling stages |

| Backbone-Fixed | Rosetta FastRelax [5], SCWRL [5], OSCAR-star [5] | Efficiently resolves side-chain collisions; low risk of disrupting correct backbone [5] | Cannot fix backbone errors; limited to side-chain and rotamer optimization [5] | High-quality backbone models requiring side-chain optimization |

| Machine Learning / Deep Learning | ATOMRefine [6], EGR for Complexes [6], RefineD [5] | Rapid prediction of refined structures; can improve both backbone and side-chains [6] | Dependent on training data; "black box" nature can make debugging difficult [6] | Integrating predictive power with sampling-based refinement |

Table 2: Key Quality Metrics for Diagnosing Model Flaws

| Metric | Formula / Calculation | What It Diagnoses | Target Value (Ideal) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD (Backbone) | √[ Σ(atomi - nativei)² / N ] | Overall global or local backbone accuracy. Lower is better [5]. | < 2.0 Å (High Accuracy) |

| Fraction of Native Contacts (fnat) | (Native Contacts in Model) / (Total Native Contacts) | Correctness of inter-subunit interfaces in complexes. Higher is better [5]. | > 0.80 (High Quality) |

| Clashscore | Number of steric clashes per 1000 atoms | Steric hindrance and unrealistic atomic overlaps. Lower is better [7]. | < 5 (High Quality) |

| Ramachandran Outliers | % of residues in disallowed regions of Ramachandran plot | Backbone torsion angle plausibility. Lower is better [7]. | < 1% (High Quality) |

Protocol: Structure Refinement Using a Memetic Algorithm (Relax-DE) [6]

- Initialization: Generate an initial population of structural decoys by applying small perturbations to the atomic coordinates of the low-quality input model.

- Evolutionary Loop:

- Mutation & Crossover: Use Differential Evolution (DE) operators to create new candidate structures by combining and modifying existing ones in the population.

- Local Refinement (Memetic Step): For each new candidate, apply the Rosetta Relax protocol. This performs local energy minimization, focusing on side-chain repacking and backbone adjustments using the full-atom Ref2015 energy function, which includes terms for steric repulsion (

fa_rep), hydrogen bonding, and solvation. - Selection: Evaluate the energy of the refined candidates using the Ref2015 scoring function and select the best-performing structures for the next generation.

- Termination: Repeat the evolutionary loop for a fixed number of generations or until convergence. The lowest-energy structure is selected as the refined model.

Protocol: Gene Ontology-Based Assessment (GOBA) for Model Validation [8]

- Functional Similarity Calculation: For the target protein, obtain a set of functionally similar proteins from databases using its Gene Ontology (GO) terms. Calculate semantic similarity between GO annotations of the target and other proteins using Wang's algorithm.

- Structural Similarity Calculation: Use the Dali structural comparison tool to measure the structural similarity (Z-score) between the model being assessed and each protein in the functionally similar set.

- Quality Score Calculation: The final GOBA score is the weighted sum of the Dali Z-scores, where the weights are the functional similarity scores. A high GOBA score indicates that the model is structurally similar to proteins of similar function, suggesting high quality.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rosetta Relax | Software Suite | Full-atom, energy-based refinement of side-chains and backbone using Monte Carlo and minimization techniques. | [5] [6] |

| Galaxy-Refine-Complex | Web Server / Software | Refinement of protein complexes via iterative side-chain perturbation and restrained molecular dynamics. | [5] |

| SCWRL4 | Software Algorithm | Fast, accurate side-chain conformation prediction and placement based on a graph theory approach. | [5] |

| MolProbity | Validation Service | Structure validation tool that identifies steric clashes, Ramachandran outliers, and other geometry issues. | [7] |

| GOBA | Quality Assessment | Single-model quality assessment program that scores models based on structural similarity to functionally related proteins. | [8] |

| AutoDock Vina | Docking Software | Used for high-throughput virtual screening to generate initial poses for ligands in structure-based drug design. | [9] |

| Modeller | Software | Homology modeling to generate initial 3D structural models from a target sequence and a related template structure. | [9] |

| PDB | Database | Repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids, used as templates and benchmarks. | [7] [6] |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: Protein model refinement and troubleshooting workflow.

The Sampling and Scoring Paradigm in Conformational Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does my docking or structure prediction algorithm fail to identify near-native structures even after extensive sampling?

This common failure often stems from the decoupling of sampling and scoring [10]. Your sampling step may use a simplified, computationally efficient scoring function to explore the conformational space, while your final scoring uses a more sophisticated function. If these two functions are not well-aligned, the low-energy regions identified during sampling may not correspond to the true low-energy, near-native conformations [10] [11]. Essentially, the sampling function may guide the search away from the correct region of the conformational landscape.

- Solution: Aim for better integration between sampling and scoring. Consider using a more accurate energy function during the later stages of sampling or employing a search algorithm like Model-Based Search (MBS), which builds a model of the energy landscape during search to guide exploration more effectively [11].

FAQ 2: What is the difference between "perturbation-based" and "docking-based" decoys, and why does it matter?

Decoys are non-native structures used to test and develop scoring functions. The method used to generate them is critical:

- Perturbation-based decoys are created by slightly misplacing components of a known native structure [10].

- Docking-based decoys are generated by performing actual docking simulations, often starting from the unbound (separately crystallized) structures of the components [10].

- Solution: For developing methods aimed at realistic docking problems, docking-based decoys are superior. Perturbation-based decoys can be artificially easy for scoring functions to discriminate and do not represent the true challenges of a docking search, potentially leading to over-optimistic results and poorly performing scoring functions in practice [10].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the coverage of conformational space for a highly flexible ligand?

A key challenge is the combinatorial explosion of possible conformers as the number of rotatable bonds increases [12]. Traditional systematic methods become computationally infeasible, while purely stochastic methods may yield non-deterministic results.

- Solution: Consider algorithms that treat rotatable bonds unequally based on their contribution to conformational change. The ABCR (Algorithm based on Bond Contribution Ranking) algorithm, for example, ranks and processes rotatable bonds in batches, focusing computational resources on bonds that have the largest impact on the overall conformation, which can lead to more efficient global sampling [12].

FAQ 4: My sampling algorithm finds a low-energy conformation, but it is far from the native structure. What is the likely cause?

This discrepancy often points to an inaccuracy in the energy function itself [11]. If the scoring function does not correctly describe the physical interactions that stabilize the native complex, the global minimum of the in silico energy landscape will not align with the biologically relevant structure.

- Solution: This failure can be used to identify weaknesses in your energy function. Furthermore, to increase confidence in your results, employ a strategy like the "Wisdom of the Crowds"—using multiple docking programs and combining their results can sometimes compensate for the weaknesses of any single program or scoring function [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Performance in Identifying Correct Poses (Low Success Rate)

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak Scoring Function | Check if the correct pose is generated during sampling but poorly ranked [13]. | Use a consensus scoring approach (e.g., United Subset Consensus) or re-train your scoring function on more realistic, docking-based decoy sets [10] [13]. |

| Inadequate Sampling | Analyze if the conformational search is restricted. | Increase sampling diversity; use algorithms like Model-Based Search or check for a high number of ligand rotatable bonds, which can hinder sampling [11] [13]. |

| Use of Bound Decoys | Review the origin of your training/validation decoy set. | Replace decoys generated from bound (co-crystallized) structures with those from unbound docking, as they present a more realistic challenge [10]. |

Issue: Inefficient Sampling (High Computational Cost, Low Yield)

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial Explosion | Monitor the number of generated conformers versus rotatable bonds [12]. | Implement a focused sampling algorithm like ABCR that ranks rotatable bonds by contribution and processes them in batches to optimize the search [12]. |

| Rugged Energy Landscape | Observe if the search gets trapped in local minima frequently. | Utilize search methods like replica exchange Monte Carlo or basin hopping that are designed to escape local minima [11]. |

| Over-reliance on Smoothing | Check if early search stages use an oversimplified energy function. | Integrate more accurate, all-atom energy information earlier in the search process, as demonstrated in Model-Based Search [11]. |

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Docking Programs in Pose Identification Data based on a benchmark of 100 protein-ligand complexes from the DUD-E dataset [13].

| Docking Program | Correct Poses Found (Sampling) | Correct Poses Ranked Top-1 (Scoring) | Correct Poses Ranked Top-4 (Scoring) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surflex | 84 | 59 | 73 |

| Glide | 83 | 68 | 75 |

| Gold | 80 | 61 | 71 |

| FlexX | 77 | 54 | 66 |

| USC Consensus | Information Missing | Information Missing | 87 |

Table 2: Conformer Generation Efficiency of the ABCR Algorithm The ABCR algorithm was evaluated on a dataset of 100 ligands with high flexibility [12].

| Metric | ABCR Performance | Comparative Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RMSD to Crystal Structure | ~1.5 Å (Average, after optimization) | Achieved lower RMSD compared to other methods like Balloon and ETKDG on the same dataset [12]. |

| Number of Conformers Generated | Relationship with rotatable bonds controlled (See Eq. 1 [12]) | Designed to find optimal conformers with fewer generated structures, avoiding combinatorial explosion. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Model-Based Search for Conformation Space Search

This protocol outlines the use of Model-Based Search (MBS) for protein structure prediction, which integrates accurate energy functions with intelligent search [11].

- Initialization: Begin with a set of random or heuristic-based initial protein conformations.

- Iterative Model Building and Sampling:

- Execute Sampling Steps: Perform a limited number of conformational search steps (e.g., using Monte Carlo moves).

- Update the Model: Aggregate information from all sampled conformations to build a model that approximates the energy landscape. This model predicts which regions of the conformation space are most promising.

- Guide Exploration: Use the model to select the next regions for exploration, focusing computational resources on areas with a high probability of containing low-energy, near-native structures.

- Refinement: The final set of promising conformations is refined using a high-fidelity, all-atom energy function.

Protocol 2: United Subset Consensus (USC) for Improved Docking

This protocol uses a consensus strategy to improve the chances of finding a correct pose [13].

- Individual Docking: Run docking simulations for the same ligand-protein system using multiple independent programs (e.g., Gold, Glide, Surflex, FlexX).

- Pose Collection: Collect all generated poses from all programs into a single, unified set.

- Consensus Identification: Identify poses that are geometrically similar across the different programs. These consensus poses are considered more reliable.

- Re-ranking: Create a shortlist of top poses based on their consensus across programs. This method can identify correct poses that individual programs might rank poorly.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 2: The Integrated MBS Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Conformational Optimization Research

| Resource / Tool | Type | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZDOCK/ZRANK | Docking Program & Scoring | Generates decoy sets and provides scoring functions for protein-protein docking [10]. | Decoy sets available online are often generated from unbound structures, making them realistic for method development [10]. |

| RosettaDock | Docking Suite | Provides a flexible framework for protein docking and scoring, including various sampling and scoring protocols [10]. | Includes decoy sets based on both perturbation and unbound docking [10]. |

| DOCKGROUND | Database | Provides a repository of benchmark docking decoy sets for the community [10]. | Useful for obtaining standardized decoy sets for fair comparison of different scoring functions [10]. |

| ABCR | Conformer Generation Algorithm | Optimizes conformer generation for small molecules by focusing on rotatable bonds with the highest impact [12]. | Helps avoid combinatorial explosion and can be used with any user-specified scoring function [12]. |

| Model-Based Search (MBS) | Search Algorithm | A conformation space search method that uses a model of the energy landscape to guide exploration [11]. | Designed to work effectively with accurate, all-atom energy functions, improving prediction accuracy [11]. |

Energy Landscapes and the Thermodynamic Hypothesis of Protein Folding

Theoretical Foundations: FAQs

FAQ 1: What is the thermodynamic hypothesis of protein folding?

The thermodynamic hypothesis, also known as Anfinsen's dogma, states that for a small globular protein under physiological conditions, the native three-dimensional structure is uniquely determined by its amino acid sequence [14]. This native state corresponds to the conformation with the lowest Gibbs free energy, making it the most thermodynamically stable arrangement. The hypothesis requires that the native state is both unique (no other configurations have comparable energy) and kinetically accessible (the protein can reliably find this state without getting trapped) [14].

FAQ 2: How does the energy landscape theory explain the speed of protein folding?

The energy landscape theory visualizes protein folding not as a single pathway, but as a funnel-shaped energy landscape [15] [16]. At the top of the funnel, the unfolded protein has high conformational entropy and high free energy. As it folds, it samples a narrowing ensemble of partially folded structures, progressively losing entropy but gaining stability through native contacts, until it reaches the low-energy native state at the funnel's bottom [16]. This "funnel" concept resolves Levinthal's paradox by showing that proteins do not need to randomly sample all possible conformations; instead, the biased nature of the landscape guides them efficiently toward the native state through a multitude of parallel routes [15] [16].

FAQ 3: What causes protein misfolding and aggregation?

A perfectly "funneled" landscape would lead directly to the native state. However, real landscapes are often rugged, containing non-native local energy minima where folding can become transiently trapped [16] [14]. These kinetic traps arise from conflicting structural interactions, known as frustration [15] [16]. When partially folded structures with exposed hydrophobic surfaces become trapped in these minima, they can interact incorrectly with other molecules, leading to aggregation. In diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, proteins misfold into stable, alternative conformations (e.g., amyloids) that are thermodynamically stable but pathological, representing exceptions to the classic Anfinsen's dogma [14].

Troubleshooting Guides for Structural Refinement

Problem: My experimental structural model has poor stereochemistry and Ramachandran statistics after low-resolution refinement.

Solution: Apply external restraints to stabilize refinement.

- Diagnosis: Low-resolution experimental data (e.g., from cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography) results in a small ratio of observations to adjustable atomic parameters, making refinement unstable [17].

- Action Plan: Utilize automated pipelines like LORESTR (Low-Resolution Structure Refinement), which is designed for such cases [17].

- Generate Restraints: Use a tool like ProSMART to generate external restraints. These can be based on:

- Homologous structures with known high-resolution models.

- Generic geometric restraints for stabilizing secondary structure elements [17].

- Execute Refinement: Feed these restraints into refinement programs such as REFMAC5 [17].

- Protocol Selection: If the optimal protocol is unclear, LORESTR can execute multiple refinement instances in parallel to identify the best-performing one automatically [17].

- Generate Restraints: Use a tool like ProSMART to generate external restraints. These can be based on:

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Low-Resolution Refinement

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Role in Refinement Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| LORESTR | Automated Pipeline | Executes multiple refinement protocols, auto-detects twinning, and selects optimal solvent parameters [17]. |

| ProSMART | Restraint Generation | Generates external restraints using homologous structures or generic geometry to stabilize the model [17]. |

| REFMAC5 | Refinement Program | Performs the atomic model refinement against experimental data, stabilized by the provided restraints [17]. |

| Rosetta | Refinement & Rebuilding | Uses a Monte Carlo method to refine models guided by cryo-EM density maps, capable of extensive rebuilding [18]. |

Problem: I have a low-resolution Cryo-EM map and an initial Cα trace or comparative model that is inaccurate.

Solution: Use a rebuild-and-refine protocol guided by the density map.

- Diagnosis: Initial models, whether from hand-tracing density or comparative modeling, often contain errors in backbone tracing and side-chain placement that cannot be fixed by minor adjustments [18].

- Action Plan: Implement a protocol based on the Rosetta structure refinement methodology [18].

- Guided Sampling: Augment the Rosetta energy function with a term that quantifies the fit between the atomic model and the experimental density map.

- Extensive Rebuilding: The protocol should not just refine but also rebuild regions identified as incompatible with the experimental density.

- Validation: Test this on a benchmark case. For example, refining the equatorial domain of GroEL from a 4.2Å cryo-EM map and a Cα trace improved the Cα RMSD of helical regions from 3.4Å to 2.2Å [18].

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking of Rosetta Refinement into Cryo-EM Maps

| Protein (PDB Code) | Number of Residues | Lowest-RMSD Starting Model (Å) | Lowest-Energy Refined Structure (5Å Map) (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1c2r | 115 | 3.45 / 4.15 | 0.54 / 1.12 |

| 1dxt | 143 | 2.02 / 2.78 | 0.50 / 1.14 |

| 1onc | 101 | 2.23 / 2.97 | 0.81 / 1.92 |

| 2cmd | 310 | 2.50 / 3.42 | 1.80 / 2.63 |

Table note: RMSD values are presented as Cα RMSD / all-atom RMSD relative to the native crystal structure. Data adapted from Rosetta refinement tests using synthesized 5Å density maps [18].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Refining a Comparative Model into a Low-Resolution Density Map

Objective: To improve the accuracy of a protein model built by homology (comparative modeling) using a low-resolution (e.g., 5-10Å) cryo-EM density map.

Materials:

- Software: Rosetta software suite [18].

- Inputs:

- The initial comparative model (e.g., generated by a threading algorithm like Moulder or GenThreader).

- The experimental cryo-EM density map in a standard format (e.g., .mrc).

Method:

- Preparation: Convert the density map to the required format for Rosetta, if necessary.

- Input Configuration: Prepare a Rosetta configuration script that specifies:

- The path to the starting model (PDB format).

- The path to the density map file.

- The resolution of the map.

- The weight of the fit-to-density term relative to the standard Rosetta energy function.

- Refinement Execution: Run the Rosetta refinement protocol. This typically involves:

- Monte Carlo Sampling: The algorithm will make random changes to the protein's conformation (e.g., side-chain rotations, small backbone moves).

- Density-Guided Optimization: Each proposed conformational change is evaluated based on the combined score of the physical energy and the fit-to-density. Moves that improve the score are accepted.

- Focused Rebuilding: Regions with poor fit-to-density are targeted for more extensive conformational sampling and rebuilding.

- Model Selection: Upon completion, Rosetta generates thousands of models. Select the final model based on:

- The lowest combined Rosetta energy and fit-to-density score.

- The best correlation coefficient with the experimental density.

- Good stereochemical quality [18].

Protocol 2: Generating and Using External Restraints for Low-Resolution Refinement

Objective: Stabilize the refinement of an atomic model against low-resolution data using prior information from homologous structures.

Materials:

- Software: LORESTR pipeline, ProSMART, REFMAC5 [17].

- Inputs:

- Your atomic model in PDB format.

- The experimental data (e.g., structure factors for crystallography).

- (Optional) One or more homologous high-resolution structures. If not provided, LORESTR can run an automated BLAST search to fetch them from the PDB [17].

Method:

- Pipeline Setup: Input your model and data into the LORESTR pipeline.

- Automated Analysis: LORESTR will perform:

- Auto-detection of crystal twinning.

- Selection of the optimal data scaling method and solvent model parameters.

- If no homologues are provided, it will automatically search for and download suitable structures.

- Restraint Generation: ProSMART will analyze the provided homologous structures to generate positional restraints for your model, tethering it to geometrically plausible conformations.

- Parallel Refinement: LORESTR will launch multiple instances of REFMAC5, each using a slightly different refinement protocol (e.g., varying restraint weights).

- Output Analysis: The pipeline evaluates all refined models based on R-factors, geometry, and Ramachandran plot statistics, and selects the best-performing one for the user [17].

Conceptual Diagrams

Protein Folding Funnel

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Structural Refinement Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tool / Database | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary repository for experimentally determined macromolecular structures, used for obtaining homologues and prior information for refinement [19]. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Provides over 200 million highly accurate predicted protein structures, useful as starting models or as references for restraint generation [20]. | |

| Refinement Software | Rosetta | A versatile software suite for structural modeling and refinement, particularly powerful for rebuilding and refining models into cryo-EM density maps [18]. |

| REFMAC5 / ProSMART / LORESTR | A combination of refinement program, restraint generator, and automated pipeline specifically optimized for low-resolution data [17]. | |

| Validation & Analysis | PDB Validation Reports | Provides standardized metrics on model quality, including Ramachandran plot statistics, side-chain rotamer outliers, and clashscores, crucial for assessing refinement outcomes [19]. |

| MolProbity | A widely used structure-validation web service that provides comprehensive analysis of stereochemical quality [19]. |

Limitations of Library-Based Stereochemical Restraints in Conventional Refinement

FAQs: Troubleshooting Common Refinement Problems

FAQ 1: Why does my refined model of a novel ligand have poor geometry, even though the electron density fit seems acceptable?

This is a classic symptom of inadequate stereochemical restraints. Conventional refinement relies on a pre-generated CIF (Crystallographic Information File) restraint library for ligands. This library is based on the ligand's ideal, unbound geometry and does not account for protein-induced strain or specific chemical environments in the active site [21] [22]. The refinement forces the ligand to fit the density while adhering to these idealized restraints, often resulting in strained bond lengths and angles.

- Solution: Utilize refinement methods that incorporate more robust energy functionals. Quantum-mechanical (QM) refinement, for example, calculates stereochemical restraints on-the-fly based on the ligand's specific atomic environment, eliminating the need for an a priori CIF file and producing more chemically accurate models [21].

FAQ 2: My low-resolution structure refinement resulted in distorted protein geometry. What went wrong?

At low resolution, the experimental data is insufficient to determine all atomic parameters accurately. The refinement relies more heavily on the prior knowledge encoded in the stereochemical restraints [23]. Standard library restraints are limited to covalent geometry (bonds, angles, etc.) and lack meaningful terms for non-covalent interactions that stabilize secondary and tertiary structures, such as hydrogen bonds and π-stacking [24]. This can lead to distorted backbone torsion angles and implausible side-chain rotamers.

- Solution: Incorporate additional restraints on the protein backbone and side chains. Tools within refinement suites like PHENIX or REFMAC5 allow you to apply restraints for hydrogen bonding, Ramachandran preferences, and rotamer states [24]. For a more fundamental solution, consider AI-enabled quantum refinement (AQuaRef), which uses a machine-learned interatomic potential to maintain superior geometric quality during low-resolution refinement [24].

FAQ 3: How can stereochemical errors in a refined model impact downstream drug discovery efforts?

Inaccurate structural models directly mislead structure-based drug design (SBDD). Errors can create:

- False Positives: The model shows a strong interaction (e.g., a hydrogen bond) that does not exist in reality, causing chemists to waste effort optimizing the wrong part of a molecule [22].

- False Negatives: A genuine productive interaction is missed because the ligand or protein side chain is incorrectly modeled [22].

- Inaccurate Binding Affinity Predictions: Computational predictions of binding affinity (scoring) are critically dependent on precise atomic coordinates. Models from conventional refinement have been shown to yield poorer correlations with experimental affinity compared to QM-refined models [22].

FAQ 4: What are the most common sources of stereochemical errors in biomolecular structures?

The most common sources include:

- Ligand Restraint Files (CIFs): Manual creation is error-prone, and even automated tools use ideal gas-phase geometry [21].

- Model Building at Low Resolution: It is difficult to correctly fit atoms into poor or ambiguous electron density.

- Incomplete Models: Missing atoms or residues can cause local strain as the refinement attempts to compensate.

- Incorrect Chirality or Peptide Bond Isomerization: These errors can severely disrupt secondary structure, as demonstrated in molecular dynamics simulations [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Correcting and Validating Ligand Geometry

Problem: A ligand in the refined model has unusual bond lengths or angles, high B-factors, or poor fit in the density.

Protocol:

- Validate: Run a validation tool like

molprobityor the PDB validation server to identify specific geometric outliers [25]. - Inspect the CIF: Check the ligand restraint file (CIF) for errors. Use a program like

eLBOW(in PHENIX) to generate a new CIF from the ligand's molecular structure [21]. - Consider the Chemistry: Does the strained geometry make chemical sense? Could the ligand be in a different protonation or tautomeric state?

- Re-refine with Advanced Methods:

- Using PHENIX/DivCon: Replace the CIF restraints with a QM/MM functional. This can be done by integrating the DivCon plugin with the standard PHENIX refinement workflow. The QM method will calculate appropriate restraints in real-time [21] [22].

- Using AQuaRef: For a more comprehensive solution, refine the entire structure using the AQuaRef package, which uses a machine-learned quantum potential to guide the refinement without relying on libraries [24].

Guide 2: Improving Protein Geometry in Low-Resolution Refinement

Problem: The refined protein model has poor Ramachandran statistics, many rotamer outliers, or distorted secondary structures.

Protocol:

- Apply Secondary Structure Restraints: In refinement software like REFMAC5 or PHENIX, apply hydrogen-bond restraints and restraints on main-chain φ/ψ angles (Ramachandran restraints) and side-chain χ angles (rotamer restraints) [24] [23].

- Use External Homologous Models: If a high-resolution structure of a homologous protein is available, you can use it to generate external restraints for the low-resolution model, informing the refinement about likely geometries [23].

- Switch to Quantum Refinement: For the most robust results, use a quantum refinement method like AQuaRef. This approach is specifically designed to maintain excellent protein geometry at low resolution, achieving better MolProbity scores and Ramachandran Z-scores than standard methods, with a comparable fit to the experimental data [24].

The table below summarizes quantitative data comparing conventional and advanced refinement methods, demonstrating the impact of moving beyond simple library-based restraints.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Refinement Methods on Protein-Ligand Structures

| Metric | Conventional Refinement | QM/MM Refinement (e.g., PHENIX/DivCon) | AI-Quantum Refinement (AQuaRef) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Ligand Strain | Higher | ~3-fold improvement vs. conventional [22] | Not Specified |

| MolProbity Score | Baseline | On average 2x lower (better) [22] | Superior geometry quality [24] |

| Ramachandran Z-score | Baseline | Not Specified | Systematically superior [24] |

| Handling of Novel Chemistry | Requires error-prone manual CIF creation | No CIF required; handles novel motifs [21] | No library required; handles any chemical entity [24] |

| Key Limitation Addressed | N/A | Fixed, idealized ligand restraints | Limited non-covalent interactions in restraints |

Table 2: Impact of Refinement Method on Drug Discovery Applications

| Application | Outcome with Conventional Refinement | Outcome with QM/MM Refinement |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Affinity Prediction | Poorer correlation with experimental data | Significantly improved correlation [22] |

| Detection of Key Interactions | Prone to false positives and false negatives [22] | More accurate identification of H-bonds and other interactions [22] |

| Proton/Protomer State Determination | Not directly supported | Enabled with tools like XModeScore [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Advanced Structural Refinement

| Tool Name | Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| PHENIX/DivCon [21] [22] | QM/MM X-ray & Cryo-EM Refinement | Replaces CIF restraints with a QM/MM functional during refinement. |

| AQuaRef [24] | AI-Enabled Quantum Refinement | Uses machine-learned interatomic potential for entire-protein refinement. |

| REFMAC5 [23] | Macromolecular Refinement | Bayesian framework allowing use of external restraints from homologous models. |

| MolProbity [24] [25] | Structure Validation | Provides comprehensive validation of stereochemistry, clashes, and rotamers. |

| Coot | Model Building & Fitting | Graphical tool for manual model adjustment and ligand fitting. |

Workflow Visualization: From Conventional to Quantum Refinement

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental differences between the conventional refinement workflow and the advanced quantum refinement workflow.

Diagram 1: Contrasting refinement workflows highlights the manual, iterative nature of conventional methods versus the more automated, chemically-driven quantum approach.

Key Methodologies: Experimental Protocols in Detail

Protocol 1: Quantum Refinement of a Protein-Ligand Structure using PHENIX/DivCon

Purpose: To refine a macromolecular crystal structure containing a ligand, obtaining a model with superior geometry without relying on a pre-defined ligand CIF file.

Detailed Methodology:

- Initial Model Preparation: Begin with your best initial atomic model, solved and partially refined using molecular replacement or other methods.

- Integration with PHENIX: Ensure the DivCon plugin is properly installed and integrated with your PHENIX refinement environment [21].

- Refinement Setup: In the PHENIX refinement interface, select the option to use DivCon for the QM calculations. Define the QM region—typically the ligand and its immediate protein environment (e.g., residues within 5-10 Å).

- Run Refinement: Execute the standard PHENIX refinement macro-cycle. The key difference is that in each micro-cycle, the L-BFGS minimizer will use energy gradients computed by the semiempirical QM (e.g., AM1) method for the defined region instead of gradients from the CIF-based restraints [21]. The target function becomes:

T = Ωxray * Txray + ΩQM * TQM, whereTQMis the QM energy. - Validation: Upon completion, validate the final model using MolProbity. Expect to see lower ligand strain and improved clashscores compared to conventional refinement [22].

Protocol 2: Full-Protein AI-Quantum Refinement using AQuaRef

Purpose: To refine an entire protein structure (e.g., from low-resolution X-ray or cryo-EM data) using a machine-learned quantum potential to achieve optimal geometry.

Detailed Methodology:

- Pre-refinement Checks: The AQuaRef procedure begins with a strict check of the initial model. The model must be atom-complete, correctly protonated, and free of severe steric clashes. Missing atoms must be added, and severe clashes are resolved with quick geometry regularization [24].

- Crystallographic Symmetry Handling (For X-ray): For crystallographic data, the model is expanded into a supercell using space group symmetry operators to account for crystal packing effects. It is then truncated to retain only parts within a specified distance from the main copy [24].

- Refinement Execution: The atom-completed (and potentially expanded) model is refined using the Q|R package within Phenix, which now uses the AIMNet2 machine-learned interatomic potential (MLIP) to calculate restraints. This potential mimics quantum mechanics at a fraction of the computational cost, allowing for linear scaling (O(N)) with system size [24].

- Analysis: The refined model will typically show a superior MolProbity score, better Ramachandran statistics, and a similar or better fit to the experimental data (R-free) compared to models refined with standard or additional restraints [24].

Cutting-Edge Refinement Methodologies: From AI-Driven Potentials to Hybrid Algorithms

AQuaRef Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Initial Refinement Fails Due to Severe Geometric Violations

- Problem: The AQuaRef procedure terminates at the initial check, reporting severe geometric violations like steric clashes or broken covalent bonds.

- Cause: AQuaRef requires a stricter initial atomic model compared to standard refinement. The input model must be atom-complete, correctly protonated, and free of major geometric errors [24].

- Solution: Perform quick geometry regularization using standard stereochemical restraints prior to initiating AQuaRef. This step minimally adjusts atoms to resolve clashes without significantly altering the model [24].

Issue 2: Unacceptable Computational Performance or GPU Memory Exhaustion

- Problem: The refinement process is excessively slow or fails due to insufficient GPU memory.

- Cause: While AQuaRef's AIMNet2 potential scales linearly (O(N)) with system size, very large models (>180,000 atoms) may exceed the memory of a single GPU. Performance can also be suboptimal if hardware does not meet recommendations [24].

- Solution:

- Verify your system meets the recommended hardware specifications (see Section 1.3, Essential Research Reagent Solutions).

- For large systems, ensure you are using a GPU with at least 80GB of memory, such as an NVIDIA H100, to accommodate models up to ~180,000 atoms [24].

- Confirm that the AIMNet2 model is being utilized, as it provides quantum-level fidelity at a fraction of the cost of full QM calculations [24] [26] [27].

Issue 3: Poor Fit to Experimental Data After Quantum Refinement

- Problem: The refined atomic model shows excellent geometry but a worsened fit to the experimental data (e.g., higher R-free).

- Cause: The balance between the fit to the experimental data (Tdata) and the quantum-mechanical restraints (Trestraints) may be suboptimal [24].

- Solution: This is an integral part of the refinement protocol managed by the Quantum Refinement package (Q|R). Ensure you are using the latest version of the Q|R package within Phenix, as it is specifically designed to handle this balance during the minimization process [24].

Issue 4: Handling Crystallographic Symmetry and Static Disorder

- Problem: For crystallographic data, the refinement does not correctly account for symmetry-related interactions or models with alternative conformations.

- Cause: Quantum mechanics codes, including the current AQuaRef implementation, do not inherently handle crystallographic symmetry or static disorder [24].

- Solution: For symmetry, the Q|R package automatically expands the model into a supercell using space group symmetry operators and truncates it to include nearby symmetry copies, ensuring these interactions are considered [24]. Handling static disorder remains a limitation and may require reverting to standard refinement techniques for those specific regions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of using AQuaRef over standard refinement methods? AQuaRef uses machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) to derive stereochemical restraints directly from quantum mechanics, moving beyond limited library-based restraints. This yields models with superior geometric quality, better handles non-standard chemical entities, and improves the modeling of meaningful non-covalent interactions like hydrogen bonds, all while maintaining a comparable fit to experimental data [24] [26].

Q2: My model is derived from a low-resolution Cryo-EM map. Can AQuaRef improve it? Yes. AQuaRef has been tested on 41 low-resolution cryo-EM atomic models. Results demonstrate systematic improvement in geometric quality, as measured by MolProbity scores and Ramachandran Z-scores, without degrading the fit to the experimental map [24].

Q3: How does AQuaRef assist in determining proton positions? The quantum-mechanical approach of AQuaRef is particularly adept at modeling hydrogen bonds and their associated proton positions. This has been successfully illustrated in challenging cases, such as determining the protonation states of short hydrogen bonds in the protein DJ-1 and its homolog YajL [24] [26].

Q4: What is the typical computational time for a quantum refinement cycle? Performance is structure-dependent. However, for about 70% of the models tested, AQuaRef refinement was completed in under 20 minutes. The maximum time observed was around one hour, which is often shorter than standard refinement that includes additional secondary structure and rotamer restraints [24].

Q5: What are the minimum requirements for an atomic model to be suitable for AQuaRef? The model must be atom-complete (all atoms, including hydrogens, must be present), correctly protonated, and free of severe steric clashes or broken bonds. Models with missing main-chain atoms that cannot be automatically added are not suitable for the current workflow [24].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following tables summarize key quantitative data from the AQuaRef study, which refined 41 cryo-EM and 30 X-ray structures for validation [24].

Table 1: Computational Performance Scaling of AIMNet2 Model

| System Size (Atoms) | Calculation Time (seconds) | Peak GPU Memory | Hardware |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~100,000 atoms | 0.5 s (single-point energy/forces) | Fits within 80GB | NVIDIA H100 GPU |

| Scaling Complexity | Linear (O(N)) for time and memory | Linear (O(N)) for time and memory | - |

Table 2: Geometric Quality Assessment of Refined Models

| Validation Metric | Standard Refinement | Standard + Additional Restraints | AQuaRef (QM Restraints) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MolProbity Score | Baseline | Improved vs. Standard | Superior systematic improvement |

| Ramachandran Z-score | Baseline | Improved vs. Standard | Superior systematic improvement |

| CaBLAM Disfavored | Baseline | Improved vs. Standard | Superior systematic improvement |

| Hydrogen Bond Parameters | Baseline | Improved vs. Standard | Superior (better skew-kurtosis plot) |

Table 3: Model-to-Data Fit for X-ray Structures

| Fit Metric | Standard Refinement | AQuaRef (QM Restraints) |

|---|---|---|

| R-free | Baseline | Similar |

| R-work - R-free gap | Baseline | Smaller (indicates less overfitting) |

Experimental Protocol: AQuaRef Workflow

The AQuaRef workflow integrates machine learning interatomic potentials into the quantum refinement pipeline. The following diagram and detailed methodology outline the procedure as applied in the cited research [24].

Detailed Methodology

- Initial Model Preparation: The process begins with an initial atomic model derived from cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography data. This model is checked for atom completeness. Any missing atoms, including hydrogens, are added to create a fully protonated model. This step may introduce steric clashes, which are identified here [24].

- Geometry Regularization: If severe geometric violations (e.g., steric clashes, broken bonds) are detected, a quick geometry regularization is performed. This step uses standard stereochemical restraints to resolve the violations with minimal atomic displacement, preparing the model for stable quantum refinement [24].

- Crystallographic Symmetry Handling (X-ray only): For crystallographic data, the model is expanded into a supercell by applying relevant space group symmetry operators. This supercell is then truncated to retain only the symmetry copies within a specific cutoff distance from the atoms of the main copy. This ensures that intermolecular interactions from crystallographic symmetry are correctly accounted for during the quantum refinement, which the QM code does not handle natively. This step is bypassed for cryo-EM data [24].

- AQuaRef Minimization: The core refinement is performed using the Q|R (Quantum Refinement) package. The refinement target is minimized, which balances the fit to the experimental data (Tdata) with the quantum-mechanical energy of the system (Trestraints) calculated using the AIMNet2 machine-learned interatomic potential. This MLIP mimics high-level quantum mechanics at a substantially lower computational cost, enabling the refinement of entire proteins [24] [26] [27].

- Output: The result is a refined atomic model that exhibits superior geometric quality while maintaining an equal or better fit to the experimental data compared to models refined with standard methods [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Software and Computational Resources for AQuaRef

| Item Name | Function / Role in the Experiment | |

|---|---|---|

| AIMNet2 MLIP | The machine-learned interatomic potential that provides quantum-mechanical energy and forces for the system at a computational cost that scales linearly with system size, making full-protein refinement feasible [24] [26]. | |

| Quantum Refinement (Q|R) Package | The software package (integrated with Phenix) that manages the quantum refinement workflow, including handling symmetry, balancing the experimental data fit with QM restraints, and performing the minimization [24]. | |

| Phenix Software | A comprehensive Python-based software suite for the automated determination of macromolecular structures using X-ray crystallography and other methods. It provides the framework for the Q | R package [24]. |

| NVIDIA H100 GPU (80GB) | High-performance computing hardware recommended for large refinements. Its substantial memory allows single-point energy and force calculations for systems as large as ~180,000 atoms in about 0.5 seconds [24]. |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: The energy of my refined protein model is not decreasing, or the optimization appears stuck. What could be wrong? This is often a sampling issue. The memetic algorithm combines global and local search to escape local minima. Ensure your Differential Evolution (DE) parameters are correctly set. A low population size or improperly scaled mutation step can hinder global exploration. Furthermore, verify that the Rosetta Relax protocol is correctly integrated for local refinement; an incorrect energy function weight can prevent meaningful minimization. The "Relax-DE" approach is specifically designed to better sample the energy landscape compared to Rosetta Relax alone [6].

Q2: How do I balance the computational cost between the global DE search and the local Rosetta Relax step? The memetic algorithm is computationally intensive. For initial tests, use a low number of DE generations (e.g., 10-20) and a limited number of Relax cycles (e.g., 3-5). The runtime should be comparable to the reference method you are benchmarking against. Studies show that the Relax-DE memetic algorithm can obtain better energy-optimized conformations in the same runtime as the standard Rosetta Relax protocol [6].

Q3: My refined model has severe atomic clashes after a DE mutation step. How can this be resolved?

Atomic clashes are expected after global mutation operations. This is precisely why the local search component is critical. The integrated Rosetta Relax protocol should be applied to these perturbed decoys to perform local minimization and resolve steric conflicts by optimizing side-chain rotamers and backbone angles [6]. The fa_rep term in the Ref2015 full-atom energy function is specifically designed to penalize such repulsive interactions [6].

Q4: What is the recommended way to assess the success of a refinement run? Success should be evaluated using multiple metrics. The primary metric is the improvement in the full-atom energy score (e.g., Ref2015). However, since the native structure is unknown during prediction, you must also use spatial quality metrics. Calculate the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) of your refined models against a trusted reference structure, such as one determined experimentally. A successful refinement yields models with lower energy and comparable or better RMSD [6].

Q5: How does this memetic approach compare to new deep learning-based refinement methods? Deep learning methods, such as those using SE(3)-equivariant graph transformers (e.g., ATOMRefine), can directly refine both backbone and side-chain atoms [6]. The memetic algorithm is a sampling-based optimization approach that excels at navigating complex energy landscapes. The two are not mutually exclusive; future work could explore hybrid models where deep learning provides initial refined guesses for the memetic algorithm to further optimize [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Runtime is excessively long.

- Potential Cause 1: Protein target is too large (high number of residues).

- Solution: For large proteins, consider using a coarse-grained representation during the initial DE phases or employing fragmentation approaches [28]. The full-atom refinement with Rosetta Relax can be applied to the most promising decoys in the final stages.

- Potential Cause 2: Population size or number of generations is set too high.

- Solution: Start with smaller values (e.g., population size of 50, 10 generations) and increase gradually as needed. The goal is to find a balance between exploration and computational feasibility.

Issue: Refined models are highly similar (lack diversity).

- Potential Cause: The algorithm has converged to a single local minimum, losing population diversity.

- Solution: Integrate niching methods into the DE algorithm. Techniques such as crowding, fitness sharing, or speciation can maintain a diverse set of optimized conformations, which is crucial for exploring the multimodal energy landscape of protein folding [29].

Issue: Rosetta Relax fails to improve models generated by DE.

- Potential Cause 1: The DE mutation has created a conformation that is too distant from the native fold for local search to recover.

- Solution: Implement a filtering step before applying Relax. Discard decoys with energy scores above a certain threshold or with unrealistic stereochemistry.

- Potential Cause 2: Incorrect setup of the Rosetta Relax protocol.

- Solution: Double-check the configuration files for the refinement protocol. Ensure you are using the appropriate full-atom energy function (Ref2015) and that constraints (if used) are correctly applied [6].

Experimental Protocol: Memetic Algorithm for Protein Refinement

The following workflow details the methodology for refining protein structures using a memetic algorithm that hybridizes Differential Evolution (DE) and the Rosetta Relax protocol [6].

1. Initialization

- Input: A starting 3D structural model of the protein, typically from a low-resolution prediction method like AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold.

- Representation: Convert the structure into a full-atom representation, including all side-chain atoms.

- Population Generation: Initialize the DE population by applying small random perturbations (e.g., via "packing" and "minimization" moves in Rosetta) to the side-chain dihedral angles (χ angles) and backbone torsions of the input model. This creates an initial set of diverse decoys.

2. Evaluation

- Energy Calculation: Score each decoy (protein conformation) in the population using the Rosetta full-atom energy function, Ref2015. This function is a weighted sum of ~19 terms, including fa_rep (atom repulsion), electrostatic interactions, and solvation terms [6].

- Fitness Assignment: The raw energy score is typically used as the fitness value to be minimized. Lower energy indicates a more stable, and potentially more native-like, conformation.

3. Differential Evolution (Global Search) The DE algorithm generates new candidate solutions by combining existing ones. For a target vector in the population, a mutant vector is created:

- Mutation: Select three distinct random vectors from the population. The mutant vector is generated according to: ( V{i,g} = X{r1,g} + F \cdot (X{r2,g} - X{r3,g}) ), where ( F ) is the scaling factor.

- Crossover: Create a trial vector by mixing parameters (e.g., torsion angles) from the target vector and the mutant vector based on a crossover probability (CR).

- Selection: The trial vector is evaluated with the energy function. It replaces the target vector in the next generation if it has a lower (better) energy score.

4. Rosetta Relax (Local Search)

- After the DE selection step, the local search is applied. This can be done on all new population members, a selected subset (e.g., the best), or with a certain probability.

- The Rosetta Relax protocol performs a series of alternating side-chain "packing" (optimizing rotamer choices) and gradient-based energy "minimization" steps. This locally optimizes the atom positions to relieve atomic clashes and find the lowest energy conformation in the immediate neighborhood [6].

5. Termination and Output

- The algorithm iterates between steps 2-4 for a predefined number of generations or until convergence is reached (e.g., no significant fitness improvement over several generations).

- The final output is the lowest-energy conformation found and/or an ensemble of diverse, low-energy structures from the final population.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential computational tools and their functions in memetic algorithm-based protein refinement.

| Item Name | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite | Provides the core energy functions (Ref2015), the Relax protocol for local minimization, and utilities for manipulating protein structures (e.g., perturbing and packing side chains) [6]. |

| Differential Evolution Algorithm | A robust global optimization algorithm that recombines population members to explore the high-dimensional conformational space effectively, helping to avoid local minima [6] [29]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | A repository of experimentally solved protein structures. Used to obtain high-quality reference structures for validating refinement results and for training knowledge-based energy terms [6]. |

| Niching Methods (Crowding, Speciation) | Algorithms integrated into the DE to maintain population diversity. This is crucial for sampling multiple local minima in the deceptive, multimodal energy landscape of protein folding [29]. |

| Full-Atom Energy Function (Ref2015) | A physics- and knowledge-based scoring function used to evaluate protein conformations. It includes terms for van der Waals repulsion (fa_rep), hydrogen bonding, solvation, and torsional preferences [6]. |