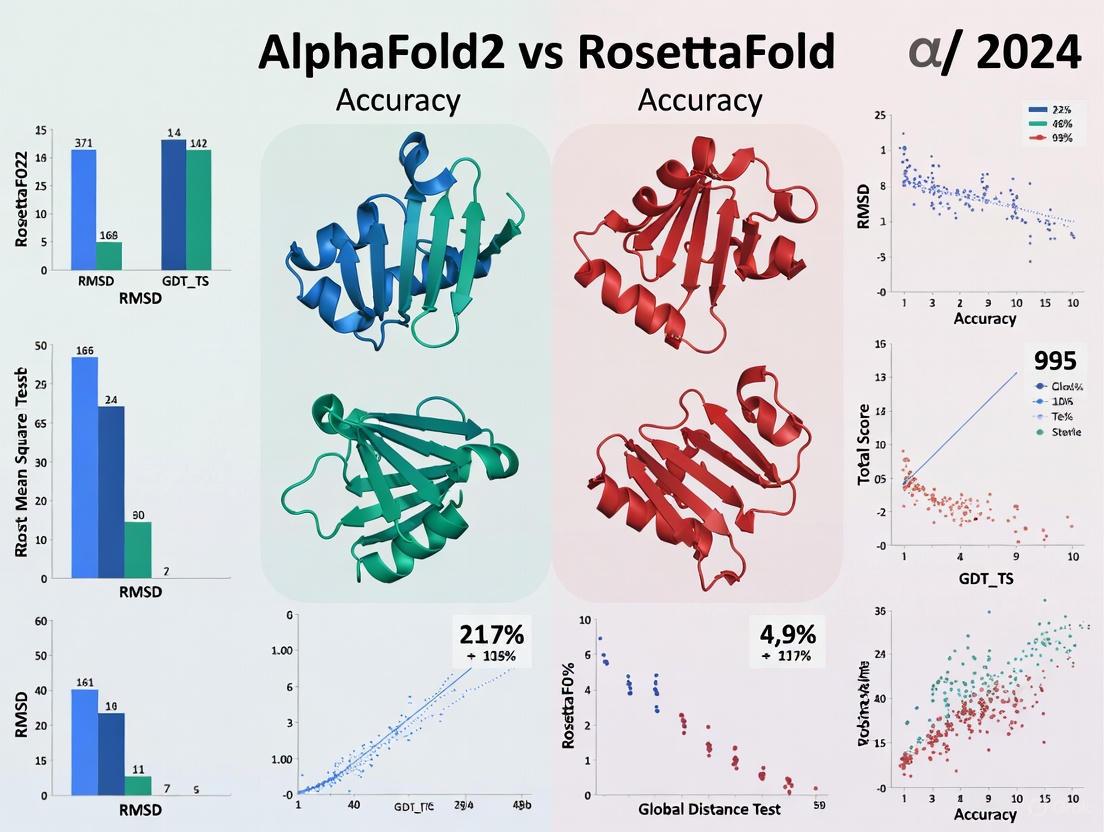

AlphaFold2 vs. RoseTTAFold in 2024: A Definitive Accuracy Comparison for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive 2024 comparison of AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold, two leading AI-powered protein structure prediction tools.

AlphaFold2 vs. RoseTTAFold in 2024: A Definitive Accuracy Comparison for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive 2024 comparison of AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold, two leading AI-powered protein structure prediction tools. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, architectural differences, and real-world performance of each system. We delve into their specific applications across structural biology and drug discovery, address common troubleshooting and interpretation challenges, and present a critical validation of their accuracy against experimental data. The analysis synthesizes key takeaways to offer practical guidance on tool selection and discusses future directions that will impact biomedical and clinical research.

The Foundational Revolution: How AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold Redefined Protein Structure Prediction

The prediction of a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence stands as one of the most challenging problems in computational biology and chemistry. This challenge, often referred to as the "protein folding problem," has puzzled scientists for over 50 years [1]. The significance of this problem stems from the fundamental role that protein structure plays in determining biological function—understanding structure enables researchers to decipher molecular mechanisms in detail, with applications spanning biotechnology, diagnostics, and therapeutic development [2]. For decades, experimental methods like X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and cryo-electron microscopy have been the primary means to determine protein structures, but these approaches are often time-consuming and expensive [1] [3]. The computational prediction of protein structures has therefore emerged as a vital complement to experimental methods, with recent advances in artificial intelligence catalyzing a revolution in the field.

The year 2024 marked a pivotal moment for this field when the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to David Baker, Demis Hassabis, and John Jumper for their groundbreaking work in computational protein design and structure prediction [4]. This recognition underscores the transformative impact that these technologies are having across biological research and drug development. At the forefront of this revolution are two dominant approaches: AlphaFold2, developed by DeepMind, and RoseTTAFold, created by David Baker's team. These systems represent the current state-of-the-art in protein structure prediction, yet they employ distinct architectural strategies and offer different strengths for researchers. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, examining their performance characteristics, underlying methodologies, and practical applications to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate tool for their specific needs.

Architectural Foundations: How AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold Work

Core Algorithmic Principles

AlphaFold2 utilizes an end-to-end deep learning architecture that integrates multiple sequence alignment (MSA) information and an initial set of pairwise distance measurements [5] [1]. Its architecture consists of two primary stages: first, an "Evoformer" module that processes the MSA and pairwise distances through repeated layers of a transformer-based neural network; and second, a "structure module" that represents the rotation and translation for each protein residue [5]. Each residue is represented as a triangle of three backbone atoms (nitrogen, alpha-carbon, carbon), and the neural network learns to position these triangles correctly in 3D space to form the predicted structures [5]. A key innovation is its use of attention mechanisms, which allow the model to focus on relevant relationships between amino acids during the folding process [6].

RoseTTAFold employs a three-track neural network that simultaneously processes information at three levels: 1D (amino acid sequence), 2D (pairwise distances between residues), and 3D (spatial coordinates) [4] [7]. This design enables the network to integrate different types of information throughout the prediction process rather than in sequential stages. The system was inspired by DeepMind's presentations on AlphaFold2 at CASP14, developed at a time when it was uncertain whether AlphaFold2's technical details would be publicly released [5]. While its accuracy was initially slightly lower than AlphaFold2, subsequent implementations have narrowed this gap while offering advantages in computational efficiency [5] [3].

System Architecture Visualization

Architectural comparison between AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold

The architectural differences between these systems lead to distinct performance characteristics. AlphaFold2's sophisticated transformer architecture generally achieves higher accuracy on targets with rich evolutionary information, while RoseTTAFold's three-track design provides strong performance with potentially greater computational efficiency and easier interpretability [5] [4]. Both systems represent significant advances over previous methods that relied primarily on homology modeling or physical simulations.

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Benchmarks

Accuracy Metrics and Validation Studies

Protein structure prediction methods are typically evaluated using metrics such as the Global Distance Test (GDT_TS), which measures the percentage of Cα atoms in the predicted structure that fall within a certain distance threshold of their correct positions in the experimental structure [1]. Additional metrics include Template Modeling Score (TM-score) for assessing structural similarity, and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) for measuring average atomic distance differences [3].

Table 1: Performance Comparison on CASP14 Benchmark Dataset

| Method | Overall GDT_TS | Easy Targets | Medium Targets | Difficult Targets | MSA Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | ~92 | ~95 | ~90 | ~87 | High |

| RoseTTAFold | ~87 | ~92 | ~85 | ~80 | High |

| LightRoseTTA | ~86 | ~90 | ~84 | ~79 | Moderate |

Data compiled from CASP14 assessments and independent evaluations [1] [3]

Independent evaluations consistently show that AlphaFold2 achieves higher accuracy across most target categories, particularly for difficult targets with few homologous sequences or novel folds [1]. However, RoseTTAFold maintains competitive performance while offering advantages in certain scenarios, such as when computational resources are limited or when studying specific protein classes like antibodies [3].

MSA Dependence and Performance on Challenging Targets

Both AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold traditionally rely heavily on multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) to extract co-evolutionary signals that inform structural constraints [5]. This dependence means that proteins with few homologous sequences in databases (such as orphan proteins, rapidly evolving proteins, or de novo designed proteins) present particular challenges [3].

Table 2: Performance on MSA-Insufficient Datasets (TM-score)

| Method | Orphan Dataset | De novo Dataset | Orphan25 Dataset | Design55 Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.81 |

| RoseTTAFold | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.78 |

| LightRoseTTA | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.83 |

Higher TM-score indicates better performance (range 0-1) [3]

Recent developments have sought to reduce MSA dependence. LightRoseTTA, a more efficient variant of RoseTTAFold, incorporates specific strategies to maintain reasonable performance even with limited homologous sequences [3]. Similarly, protein language model-based predictors like ESMFold and OmegaFold have emerged as alternatives that require no MSAs, though their overall accuracy generally lags behind alignment-based methods when MSAs are available [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Frameworks

The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments represent the gold standard for evaluating protein structure prediction methods [1] [6]. These biannual competitions employ double-blind evaluation procedures where predictors submit models for protein sequences whose experimental structures are known but not yet publicly released. The CASP14 competition in 2020 was particularly significant, as AlphaFold2's performance demonstrated unprecedented accuracy, with GDT_TS scores above 90 for approximately two-thirds of the proteins [6].

The standard evaluation protocol involves several key steps:

- Target Selection: Proteins with recently determined experimental structures (via X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, or NMR) but not yet published are selected as targets.

- Sequence-Only Provision: Participants receive only the amino acid sequences without structural information.

- Prediction Phase: Teams have a limited time window (typically 3 weeks) to generate and submit their predicted structures.

- Assessment: Organizers compare predictions to experimental structures using multiple metrics including GDT_TS, RMSD, and TM-score [1].

For continuous assessment outside the CASP cycle, the CAMEO (Continuous Automated Model Evaluation) platform provides weekly evaluations on newly published protein structures [3].

Specialized Assessment for Protein Complexes

With growing interest in predicting structures of protein complexes rather than single chains, specialized assessments like CAPRI (Critical Assessment of PRedicted Interactions) evaluate performance on protein-protein docking [8]. These evaluations present unique challenges, as accurate prediction requires modeling both the individual protein structures and their binding interfaces.

Recent studies indicate that AlphaFold-Multimer (a variant specifically trained on complexes) successfully predicts protein-protein interactions with approximately 70% accuracy [6]. However, performance varies significantly by complex type, with antibody-antigen interfaces proving particularly challenging due to limited evolutionary information across the interface [8]. One study combining AlphaFold with physics-based docking algorithms demonstrated improved performance on these difficult cases, achieving a 43% success rate for antibody-antigen targets compared to AlphaFold-Multimer's 20% success rate [8].

Practical Implementation and Workflow Integration

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Resources for Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource | Type | Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Software | Protein structure prediction | Open source (non-commercial) |

| RoseTTAFold | Software | Protein structure prediction | Open source |

| ColabFold | Web Service | Streamlined AF2/RF implementation | Free online access |

| Protein Data Bank | Database | Experimental structures for validation | Public |

| UniProt | Database | Protein sequences for MSA generation | Public |

| AlphaFold DB | Database | Precomputed predictions for proteomes | Public |

| RosettaAntibody | Specialized Tool | Antibody-specific structure prediction | Open source |

Essential resources for researchers implementing these prediction methods [5] [9] [3]

Implementation Workflow

Typical workflow for protein structure prediction

The selection between AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold often depends on specific research constraints and goals. AlphaFold2 generally provides higher accuracy when sufficient computational resources and deep multiple sequence alignments are available [1]. RoseTTAFold offers a compelling alternative when prioritizing computational efficiency or when working with specific protein classes where its architectural advantages are beneficial [3]. For most researchers, ColabFold provides an accessible entry point, offering modified versions of both AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold that run at reduced computational cost with minimal loss in accuracy [5].

Emerging Developments and Future Directions

The field of protein structure prediction continues to evolve rapidly. In 2024, DeepMind announced AlphaFold 3, which extends capabilities beyond single-chain proteins to predict structures of complexes with DNA, RNA, post-translational modifications, ligands, and ions [10] [6]. This new version introduces a "Pairformer" architecture and employs a diffusion-based approach similar to those used in image generation, demonstrating a minimum 50% improvement in accuracy for protein interactions with other molecules compared to existing methods [10] [6].

Concurrently, efforts to improve efficiency continue, with developments like LightRoseTTA demonstrating that light-weight models can achieve competitive performance while requiring only 1.4 million parameters (compared to RoseTTAFold's 130 million) and training in one week on a single GPU rather than 30 days on eight GPUs [3]. These advances make sophisticated structure prediction more accessible to researchers with limited computational resources.

Future challenges include improving predictions for proteins with significant conformational flexibility, better modeling of protein dynamics, and enhancing accuracy for specific challenging categories like antibody-antigen complexes [2] [8]. The integration of physical constraints with deep learning approaches, as demonstrated in hybrid methods like AlphaRED (AlphaFold-initiated Replica Exchange Docking), shows promise for addressing these limitations [8].

As these technologies continue to mature, their impact across biological research and drug discovery is expected to grow, enabling new approaches to understanding disease mechanisms, designing therapeutics, and exploring fundamental biological processes through the structural lens of proteins.

The revolutionary development of deep learning systems for predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences has fundamentally transformed structural biology. AlphaFold2, introduced in 2020, represented a quantum leap in accuracy, consistently achieving predictions at near-experimental resolution [11]. Its key innovation was an end-to-end deep learning architecture built around attention mechanisms that could directly predict atomic coordinates from sequence data. The open-source release of this technology spurred the development of alternative approaches, most notably RoseTTAFold, which offered a different architectural philosophy with the advantage of being runnable on a single gaming computer in as little as ten minutes [12]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two systems, examining their architectural principles, performance metrics, and practical applications within structural biology and drug development research as of 2024.

Architectural Breakdown: Two Approaches to Deep Learning

AlphaFold2's Evoformer and End-to-End Learning

AlphaFold2 operates as a single, complex neural network that takes as input primarily the amino acid sequence and, crucially, a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of evolutionarily related proteins [13]. Its architecture consists of two main stages. First, the Evoformer block—a novel neural network component—processes the input MSA and residue pair information through a series of attention-based mechanisms [11]. The Evoformer treats structure prediction as a graph inference problem where residues represent nodes and their spatial relationships represent edges [11]. It employs triangular multiplicative updates and axial attention to enforce geometric consistency, allowing the continuous flow of information between the MSA representation and the pair representation [11]. Second, the structure module introduces an explicit 3D structure using rotations and translations for each residue, progressively refining the atomic coordinates through an iterative recycling process where outputs are fed back into the network multiple times [11] [13].

RoseTTAFold's Three-Track Neural Network

RoseTTAFold employs a fundamentally different architecture described as a "three-track" neural network [12]. This system simultaneously processes information at one-dimensional (sequence), two-dimensional (distance maps), and three-dimensional (spatial coordinates) levels, with information flowing back and forth between these tracks [14]. Unlike AlphaFold2's complex Evoformer, RoseTTAFold uses a simpler approach where MSA and pair features are refined individually through attention mechanisms before being used to predict 3D coordinates [14]. The model utilizes axial attention to manage computational resources efficiently, applying attention along single axes of the data tensor to reduce complexity [14]. This architectural efficiency enables RoseTTAFold to achieve significant accuracy while being executable on hardware with limited resources compared to AlphaFold2's substantial computational requirements [12].

Table: Architectural Comparison Between AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold

| Feature | AlphaFold2 | RoseTTAFold |

|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | Evoformer blocks with structure module | Three-track neural network (1D, 2D, 3D) |

| Information Flow | Sequential: Evoformer → Structure module | Simultaneous multi-track processing |

| Key Innovation | Triangular attention mechanisms | Axial attention with pixel-wise attention |

| Computational Demand | High (requires multiple GPUs) | Moderate (runnable on single GPU) |

| MSA Dependence | High (performance degrades with shallow MSAs) | High (but uses co-evolution signals) |

| Structure Representation | Rotation frames and torsion angles | Direct coordinate prediction |

Architectural Workflow Visualization

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Analysis

Accuracy Metrics and Benchmarking

Independent benchmarking studies conducted through 2023-2024 have provided comprehensive performance comparisons between AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold across various protein classes. In the Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP14), AlphaFold2 demonstrated median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å RMSD₉₅, dramatically outperforming other methods which typically achieved 2.8 Å RMSD₉₅ [11]. While RoseTTAFold also shows strong performance, direct comparisons consistently place AlphaFold2 ahead in accuracy metrics, particularly for complex protein folds and those with limited evolutionary information [15].

A 2024 analysis published in Nature Methods provided crucial insights into the real-world performance of these prediction systems. When comparing AlphaFold predictions directly with experimental crystallographic maps, researchers found that even very high-confidence predictions (pLDDT > 90) sometimes differed from experimental maps on both global and local scales [16]. The mean map-model correlation for AlphaFold predictions was 0.56, substantially lower than the 0.86 correlation of experimentally determined models with the same maps [16]. This highlights that while both systems represent tremendous advances, they should be considered as exceptionally useful hypotheses rather than replacements for experimental structure determination [16].

Peptide Structure Prediction Benchmark

A specialized benchmark study examining peptide structure prediction (proteins with 10-40 amino acids) provides detailed comparative data between multiple prediction methods, including both AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold [15]. The study evaluated 588 peptides with experimentally determined NMR structures across six categories: α-helical membrane-associated peptides, α-helical soluble peptides, mixed secondary structure membrane-associated peptides, mixed secondary structure soluble peptides, β-hairpin peptides, and disulfide-rich peptides [15].

Table: Performance Comparison on Peptide Structure Prediction (Cα RMSD Å per residue) [15]

| Peptide Category | AlphaFold2 Performance | RoseTTAFold Performance | Notes on AlphaFold2 Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-helical membrane-associated | 0.098 Å (mean) | Slightly higher | Struggled with helix endings and turn motifs |

| α-helical soluble | 0.119 Å (mean) | Similar range | Bimodal distribution with significant outliers |

| Mixed structure membrane-associated | 0.202 Å (mean) | Similar or slightly lower | Largest variation, failed on unstructured regions |

| β-hairpin peptides | Moderate accuracy | Moderate accuracy | Both methods showed reduced accuracy |

| Disulfide-rich peptides | High accuracy | High accuracy | Sometimes incorrect disulfide bond patterns |

The study concluded that deep learning methods like AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold generally performed the best across most peptide categories but showed reduced accuracy with non-helical secondary structure motifs and solvent-exposed peptides [15]. Both systems demonstrated shortcomings in predicting certain structural features like Φ/Ψ angles and disulfide bond patterns, with the lowest RMSD structures not always correlating with the highest confidence (pLDDT) ranked structures [15].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methods

Standardized Benchmarking Methodology

The protocols for comparing protein structure prediction methods have been standardized through community-wide efforts. The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments, conducted biennially, serve as the gold-standard assessment where predictors blindly predict protein structures for which experimental results are not yet public [9]. In these assessments, accuracy is primarily measured using Global Distance Test (GDTTS) scores, which estimate the percentage of residues that can be superimposed under defined distance cutoffs [9]. A GDTTS score above 90 is considered near-experimental quality [9].

For comparative studies, researchers typically follow this protocol:

- Select diverse protein targets with recently determined experimental structures not included in training sets

- Generate predictions using both AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold with default parameters

- Superimpose predictions on experimental structures using rigid body alignment

- Calculate quantitative metrics including Cα RMSD, GDT_TS, lDDT, and TM-score

- Analyze local accuracy by examining side-chain placement, backbone torsion angles, and confidence metrics

Experimental Validation Workflow

Practical Applications in Research and Drug Development

Use Cases in Structural Biology

Both AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold have been widely adopted in structural biology workflows, significantly accelerating research. A key application is in molecular replacement for X-ray crystallography, where AlphaFold predictions have successfully phased structures in cases where templates from the Protein Data Bank had failed [9]. This includes challenging cases with novel folds or de novo designs [9]. Major crystallography software suites like CCP4 and PHENIX now include specialized procedures for handling AlphaFold predictions, converting pLDDT confidence metrics into estimated B-factors and automatically removing low-confidence regions [9].

In cryo-EM studies, both systems have enabled integrative approaches where predictions are fitted into intermediate-resolution density maps. This combination provides the best of both worlds: experimental data validates the prediction while the prediction provides atomic details [9]. Pioneering work on the nuclear pore complex used AlphaFold models for individual proteins fitted into 12-23 Å resolution electron density maps to reconstitute this massive ~120 MDa assembly [9]. Similar approaches have elucidated structures of the intraflagellar train, augmin complex, and eukaryotic lipid transport machinery [9].

Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction

Although initially trained for single-chain prediction, both systems have been extended to predict protein-protein interactions. AlphaFold-Multimer, a specially trained version, has facilitated the discovery and characterization of novel interactions [9]. Large-scale interaction prediction efforts have screened millions of protein pairs from organisms like Saccharomyces cerevisiae, identifying 1,505 novel interactions and proposing structures for 912 assemblies [9]. These capabilities have profound implications for drug development, enabling rapid mapping of interaction networks and identification of potential therapeutic targets.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Protein Structure Prediction Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Prediction Workflows |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 Open Source | Protein structure prediction | End-to-end structure prediction from sequence; requires substantial computational resources |

| RoseTTAFold | Protein structure prediction | Three-track neural network for structure prediction; more computationally efficient |

| ColabFold | Cloud-based prediction | Integrated AlphaFold2/RoseTTAFold with MMseqs2 for rapid homology searching |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Structural repository | Source of experimental structures for validation and template-based modeling |

| HHsearch | Remote homology detection | Identifies structural templates and generates initial pair features for RoseTTAFold |

| pLDDT | Confidence metric | Per-residue estimate of prediction reliability (scale: 0-100) |

| PAE (Predicted Aligned Error) | Uncertainty estimation | Inter-domain confidence measure for assessing relative domain positioning |

| ChimeraX | Molecular visualization | Fitting predictions into cryo-EM density maps; model validation |

The comparative analysis between AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold reveals two sophisticated but architecturally distinct approaches to protein structure prediction. AlphaFold2's Evoformer-based architecture achieves marginally higher accuracy in most benchmarking studies, while RoseTTAFold's three-track neural network provides a more computationally efficient alternative with competitive performance [11] [12]. Both systems have become indispensable tools in structural biology, accelerating experimental structure determination and enabling studies of previously intractable targets.

As the field progresses, the integration of these prediction tools with experimental methods represents the most promising direction. Rather than replacing experimental determination, both systems serve as powerful hypothesis generators that can be validated and refined through crystallographic and cryo-EM approaches [16]. The development of AlphaFold3 and subsequent iterations continues to expand capabilities into protein-ligand and protein-nucleic acid interactions [10], but AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold remain the established standards for single-chain protein structure prediction as of 2024. Researchers should select between them based on their specific needs—prioritizing maximum accuracy with sufficient computational resources (AlphaFold2) versus balancing efficiency with performance (RoseTTAFold).

The field of structural biology has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the advent of deep learning-based protein structure prediction. For decades, determining the three-dimensional structure of proteins relied on time-consuming and expensive experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). While these methods have provided invaluable insights, they often required years of laboratory work to determine the structure of a single protein. The breakthrough came with the development of AlphaFold2 by DeepMind, which demonstrated unprecedented accuracy in predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences alone. However, in the wake of this breakthrough, researchers from the Baker lab developed RoseTTAFold, an alternative deep learning approach that employs a unique "three-track" neural network architecture. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these two revolutionary methods, examining their architectural differences, performance metrics, and practical applications in scientific research and drug development.

Architectural Foundations: A Tale of Two Networks

RoseTTAFold's Three-Track Architecture

RoseTTAFold employs a distinctive three-track neural network that simultaneously processes information at three different levels:

- 1D Track: Processes patterns in protein sequences and evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs).

- 2D Track: Analyzes amino acid interactions and residue-residue relationships.

- 3D Track: Reasons directly about three-dimensional atomic coordinates.

The key innovation lies in how information flows back and forth between these three tracks, allowing the network to collectively reason about the relationship between a protein's sequence and its folded structure [17] [18]. This integrated approach enables RoseTTAFold to consider sequence, distance, and coordinate information simultaneously rather than sequentially.

AlphaFold2's Two-Track System

AlphaFold2 utilizes a different architectural philosophy based on a "two-track" system:

- Evoformer Block: Jointly embeds evolutionary information from MSAs and spatial relationships using attention mechanisms.

- Structure Module: Uses equivariant transformer architecture with invariant point attention to generate atomic coordinates from the processed representations.

Unlike RoseTTAFold, AlphaFold2's reasoning about 3D atomic coordinates primarily occurs after much of the processing of 1D and 2D information is complete, though end-to-end training does create some linkage between parameters [17].

Table: Architectural Comparison Between RoseTTAFold and AlphaFold2

| Feature | RoseTTAFold | AlphaFold2 |

|---|---|---|

| Network Architecture | Three-track (1D, 2D, 3D) | Two-track (Evoformer + Structure Module) |

| Information Flow | Simultaneous and integrated between tracks | Largely sequential between modules |

| 3D Processing | Continuous throughout the network | Primarily in the final structure module |

| Key Innovation | Communication between 1D, 2D, and 3D data | Attention-based equivariant transformers |

| Computational Demand | Lower - runs on single GPU in minutes | Higher - requires multiple GPUs for days for complex structures |

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental difference in how information flows through RoseTTAFold's three-track architecture compared to a more sequential approach.

Performance Comparison: Accuracy and Capabilities

Single-Chain Protein Prediction Accuracy

Independent benchmarking on CASP15 targets reveals distinct performance characteristics for both methods:

Table: Performance Metrics on CASP15 Targets (69 single-chain proteins)

| Metric | AlphaFold2 | RoseTTAFold | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean GDT-TS | 73.06 | Lower than AlphaFold2 | AlphaFold2 attains best performance with highest mean GDT-TS [19] |

| Topology Prediction (TM-score > 0.5) | ~80% | ~70% | MSA-based methods outperform PLM-based approaches [19] |

| Side-Chain Positioning (GDC-SC) | <50 (best among methods) | Lower than AlphaFold2 | Considerable room for improvement for all methods [19] |

| Stereochemical Quality | Closer to experimental | Closer to experimental | Both MSA-based methods show better stereochemistry than PLM-based methods [19] |

| MSA Dependence | Moderate | Higher | RoseTTAFold exhibits more MSA dependence than AlphaFold2 [19] |

Multi-Domain and Complex Prediction

A critical differentiator emerges in the prediction of multi-domain proteins and complexes. While AlphaFold2 demonstrates remarkable accuracy on single domains, it shows limitations in capturing correct inter-domain orientations in multi-domain proteins [20]. Specific benchmarking on 219 multi-domain proteins revealed:

- DeepAssembly (a method built on RoseTTAFold principles) achieved an average TM-score of 0.922 versus 0.900 for AlphaFold2

- Inter-domain distance precision was 22.7% higher with domain assembly approaches compared to AlphaFold2

- For 164 multi-domain structures with low confidence in the AlphaFold database, accuracy improved by 13.1% using domain assembly methods [20]

This advantage stems from RoseTTAFold's architecture being more amenable to "divide-and-conquer" strategies where proteins are split into domains, modeled individually, and then assembled using predicted inter-domain interactions.

Computational Efficiency and Accessibility

From a practical standpoint, significant differences exist in computational requirements:

- RoseTTAFold can compute a protein structure in as little as ten minutes on a single gaming computer [18]

- AlphaFold2 typically requires several GPUs for days to make individual predictions for complex structures [17]

- This efficiency difference has made RoseTTAFold more accessible to researchers without access to extensive computational resources

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CASP Benchmarking Methodology

The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments provide the gold standard for evaluating protein structure prediction methods. The standard protocol involves:

- Blind Prediction: Participants predict protein structures for which experimental results have not yet been made public

- Standardized Metrics: Structures are evaluated using GDT-TS (Global Distance Test), TM-score (Template Modeling Score), and lDDT (local Distance Difference Test)

- Independent Assessment: Predictions are evaluated by independent assessors against newly determined experimental structures

- Comparative Ranking: Methods are ranked across multiple targets to determine relative performance [9]

Domain Assembly Protocol

For multi-domain protein prediction, the following experimental approach has proven effective:

- Domain Segmentation: Input protein sequence is split into single-domain sequences using domain boundary prediction

- Individual Domain Modeling: Each domain structure is generated using a single-domain structure predictor

- Interaction Prediction: Features from MSAs, templates, and domain boundary information are fed into a deep neural network to predict inter-domain interactions

- Iterative Assembly: Population-based rotation angle optimization assembles domains into full-length structures using atomic coordinate deviation potential derived from predicted interactions [20]

Molecular Replacement Validation

Both algorithms have been validated through practical applications in experimental structure determination:

- Prediction Generation: Protein structures are predicted from sequence alone

- Experimental Phasing: Predictions are used as search models in molecular replacement to phase X-ray crystallography data

- Success Rate Comparison: The ability to solve previously intractable structures demonstrates real-world utility [9] [17]

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository of experimentally determined protein structures | Public [21] |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Precomputed AlphaFold predictions for entire proteomes | Public [9] [21] |

| RoseTTAFold Server | Web Server | Online protein structure prediction using RoseTTAFold | Public [18] |

| ColabFold | Software | Combines fast homology search with AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold | Public [9] |

| Multiple Sequence Alignments | Data | Evolutionary information critical for both methods | Generated from UniProt, MGnify |

| HHsearch | Software | Remote homology detection for template-based modeling | Public [14] |

| PAthreader | Software | Remote template recognition method | Public [20] |

Recent Advancements and Future Directions

RoseTTAFold All-Atom and AlphaFold3

Both platforms have evolved beyond protein-only prediction:

- RoseTTAFold All-Atom can now model assemblies containing proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, metals, and chemical modifications [22]

- AlphaFold3 extends capabilities to predict the joint structure of complexes including proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues [10]

- AlphaFold3 employs a diffusion-based architecture that directly predicts raw atom coordinates, replacing the earlier structure module that operated on amino-acid-specific frames [10]

Limitations and Challenges

Despite remarkable progress, both systems face ongoing challenges:

- Accurate prediction of large multi-domain proteins with complex topology remains challenging [19]

- Side-chain positioning accuracy remains limited for all methods [19]

- Conformational flexibility and multi-state proteins present ongoing challenges [23]

- Accuracy decreases as protein size increases, particularly for targets over 750 residues [19]

The comparison between RoseTTAFold and AlphaFold2 reveals not a simple winner, but rather complementary approaches to protein structure prediction. AlphaFold2 generally provides higher accuracy for single-chain proteins, particularly when sufficient evolutionary information is available. However, RoseTTAFold's three-track architecture offers distinct advantages for multi-domain protein assembly, computational efficiency, and accessibility to researchers with limited resources.

For drug development professionals and researchers, the choice between these tools depends on the specific application. For rapid screening and multi-domain proteins, RoseTTAFold provides an efficient solution. For maximum accuracy on single-chain targets, AlphaFold2 remains the gold standard. As both platforms continue to evolve—with RoseTTAFold All-Atom and AlphaFold3 expanding capabilities—the entire scientific community benefits from these powerful tools that have permanently transformed structural biology.

The field of biomolecular structure prediction has undergone a revolutionary transformation, moving from specialized models for single molecule types to general-purpose architectures capable of modeling the full complexity of biological systems. In 2024, this evolution is characterized by two leading frameworks: AlphaFold, developed by DeepMind, and RoseTTAFold, created by academic researchers. While both systems stem from similar foundational concepts in deep learning, their architectural implementations, scope, and accessibility have diverged significantly. This comparative analysis examines the high-level architectural frameworks of these systems, focusing on their capabilities, underlying neural network structures, and performance across diverse biological complexes. Understanding these architectural differences is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage these tools for specific applications, from basic science to therapeutic design.

Architectural Framework Comparison

Core Architectural Philosophies and Components

The fundamental difference between AlphaFold and RoseTTAFold lies in their architectural philosophy: AlphaFold has transitioned to a diffusion-based approach in its latest version, while RoseTTAFold maintains and extends its three-track network architecture to encompass new molecular types.

AlphaFold 3 introduces a substantially updated diffusion-based architecture that replaces the structure module of AlphaFold 2 [10]. This diffusion module operates directly on raw atom coordinates without rotational frames or equivariant processing, using a denoising task that requires the network to learn protein structure at multiple length scales [10]. The model also reduces MSA processing by replacing AlphaFold 2's evoformer with a simpler pairformer module [10]. This architectural shift allows AlphaFold 3 to predict the joint structure of complexes including proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues within a single unified deep-learning framework [10].

RoseTTAFold All-Atom (RFAA) extends the original three-track architecture to model biological assemblies containing proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, metals, and chemical modifications [22]. Similarly, RoseTTAFoldNA specifically generalizes this three-track architecture for protein-nucleic acid complexes, with extensions to all three tracks (1D, 2D, and 3D) to support nucleic acids in addition to proteins [24]. The 1D track was expanded with additional tokens for DNA and RNA nucleotides, the 2D track was generalized to model interactions between nucleic acid bases and between bases and amino acids, and the 3D track was extended to include representations of each nucleotide using a coordinate frame describing the position and orientation of the phosphate group [24].

Table 1: High-Level Architectural Comparison

| Architectural Component | AlphaFold 3 | RoseTTAFold All-Atom/NA |

|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Diffusion-based | Three-track network (1D, 2D, 3D) |

| Molecular Coverage | Proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, modified residues | Proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, metals, covalent modifications |

| MSA Processing | Pairformer (reduced MSA processing) | Integrated three-track processing |

| Structure Representation | Raw atom coordinates via diffusion | Frames and torsion angles for proteins; phosphate frames and torsion angles for nucleic acids |

| Training Data Composition | Nearly all molecular types in PDB | 60/40 ratio of protein-only to NA-containing structures; physical information incorporation |

| Confidence Estimation | pLDDT, PAE, and distance error matrix (PDE) | Interface PAE, lDDT, native contact recovery |

Performance Comparison Across Complex Types

Experimental validations in 2024 demonstrate that both architectures achieve remarkable accuracy across diverse biomolecular complexes, though with notable differences in specific domains.

AlphaFold 3 shows "substantially improved accuracy over many previous specialized tools: far greater accuracy for protein-ligand interactions compared with state-of-the-art docking tools, much higher accuracy for protein-nucleic acid interactions compared with nucleic-acid-specific predictors and substantially higher antibody-antigen prediction accuracy" [10]. In protein-ligand docking benchmarks, AlphaFold 3 greatly outperforms classical docking tools like Vina even without using structural inputs [10].

RoseTTAFoldNA achieves an average Local Distance Difference Test (lDDT) score of 0.73 on monomeric protein-nucleic acid complexes, with 29% of models achieving lDDT > 0.8 and about 45% of models containing greater than half of the native contacts between protein and nucleic acid [24]. The method correctly identifies accurate predictions, with 81% of high-confidence predictions (mean interface PAE < 10) correctly modeling the protein-nucleic acid interface [24]. Performance on complexes with no detectable sequence similarity to training structures remains strong (average lDDT = 0.68) [24].

Table 2: Performance Metrics Across Complex Types

| Complex Type | AlphaFold 3 Performance | RoseTTAFoldNA Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Protein-Ligand | "Far greater accuracy" than state-of-the-art docking tools; outperforms RoseTTAFold All-Atom [10] | Specific metrics not provided in results |

| Protein-Nucleic Acid | "Much higher accuracy" than nucleic-acid-specific predictors [10] | lDDT = 0.73 avg; 29% models >0.8 lDDT; 45% models FNAT >0.5 [24] |

| Antibody-Antigen | "Substantially higher accuracy" than AlphaFold-Multimer v2.3 [10] | Not specifically benchmarked |

| Multi-subunit Complexes | Not explicitly detailed | lDDT = 0.72 avg; 30% cases >0.8 lDDT; good confidence-accuracy correlation [24] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Training Data Curation and Processing

Both frameworks utilize the Protein Data Bank (PDB) as their primary source of structural information but employ different strategies for data curation and processing.

AlphaFold 3 was trained on "complexes containing nearly all molecular types present in the PDB" [10]. To address the challenge of generative hallucination, the developers used a "cross-distillation method" in which they enriched the training data with structures predicted by AlphaFold-Multimer (v.2.3) [10]. During training, they observed that different model abilities developed at different rates, with local structures learning quickly while global constellation understanding required considerably longer training [10].

RoseTTAFoldNA was trained using a combination of protein monomers, protein complexes, RNA monomers, RNA dimers, protein-RNA complexes, and protein-DNA complexes, with "a 60/40 ratio of protein-only and NA-containing structures" [24]. To compensate for the far smaller number of nucleic-acid-containing structures in the PDB, the developers "incorporated physical information in the form of Lennard-Jones and hydrogen-bonding energies as input features to the final refinement layers, and as part of the loss function during fine-tuning" [24]. The training set included 1,632 RNA clusters and 1,556 protein-nucleic acid complex clusters compared to 26,128 all-protein clusters after sequence-similarity-based clustering to reduce redundancy [24].

Benchmarking Methodologies

Rigorous benchmarking against experimental structures and specialized tools provides the foundation for comparing architectural performance.

AlphaFold 3 performance on protein-ligand interfaces was evaluated on the PoseBusters benchmark set, comprising "428 protein-ligand structures released to the PDB in 2021 or later" [10]. Since the standard training cut-off date was in 2021, the team "trained a separate AF3 model with an earlier training-set cutoff" to ensure fair evaluation [10]. Accuracy was reported as "the percentage of protein-ligand pairs with pocket-aligned ligand root mean squared deviation (r.m.s.d.) of less than 2 Å" [10].

RoseTTAFoldNA was evaluated using "RNA and protein-NA structures solved since May 2020 as an additional independent validation set" [24]. Complexes were not broken into interacting pairs for the validation set and were processed as full complexes, excluding those with "more than 1,000 total amino acids and nucleotides" due to GPU memory limitations [24]. This resulted in a validation set containing "520 cases with a single RNA chain, 224 complexes with one protein molecule plus a single RNA chain or DNA duplex, and 161 cases with more than one protein chain or more than a single RNA chain or DNA duplex" [24].

Visualization 1: Comparative Architecture Workflows. AlphaFold 3 employs a sequential pipeline with a diffusion-based structure module, while RoseTTAFold uses a three-track architecture with continuous information exchange between tracks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing and leveraging these architectures requires specific computational resources and data components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource | Function | AlphaFold 3 Implementation | RoseTTAFoldNA Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) | Provides evolutionary constraints for structure prediction | Substantially reduced processing via Pairformer | Integrated three-track processing with paired MSAs for complexes |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of training structures and validation benchmarks | Contains nearly all molecular types | Augmented with physical information (Lennard-Jones, H-bond energies) |

| Molecular Representation | Encoding diverse molecular types | SMILES for ligands; polymer sequences | Extended 1D tokens (DNA/RNA nucleotides); 3D frames with torsion angles |

| Confidence Metrics | Assessing prediction reliability | pLDDT, PAE, distance error matrix (PDE) | Interface PAE, lDDT, fraction of native contacts (FNAT) |

| Computational Resources | GPU memory and processing capacity | Not specified in results | Limits complex size (~1000 amino acids+nucleotides) for full processing |

Visualization 2: Experimental Validation Workflow. Both architectures follow a similar high-level workflow from input to validation, with architecture-specific processing steps. The iterative refinement cycle uses experimental validation to improve model performance.

The comparative analysis of AlphaFold 3 and RoseTTAFold All-Atom/NA reveals distinct architectural philosophies with complementary strengths. AlphaFold 3's diffusion-based approach demonstrates remarkable performance across diverse biomolecular interactions, potentially offering higher accuracy particularly for protein-ligand complexes. Meanwhile, RoseTTAFold's three-track architecture provides a more physically grounded framework with explicit information exchange between sequence, distance, and coordinate representations. The 2024 landscape shows both architectures converging toward comprehensive biomolecular modeling capabilities while maintaining distinct implementation approaches. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between these frameworks may depend on specific application requirements, with AlphaFold 3 potentially offering superior accuracy for drug-like molecules and RoseTTAFold providing greater interpretability and physical constraints for complex nucleic-acid-protein interactions. As both architectures continue to evolve, the integration of their strengths may further advance the field of computational structural biology.

The field of computational structural biology has entered a transformative phase with the recent emergence of sophisticated artificial intelligence tools capable of predicting the structures of biomolecular complexes. While AlphaFold2 and the original RoseTTAFold revolutionized protein structure prediction in 2021, their capabilities were primarily limited to single proteins or protein-protein interactions [25]. The 2024 release of AlphaFold3 (AF3) and RoseTTAFold All-Atom (RFAA) represents a quantum leap forward, extending prediction capabilities to nearly all molecular components present in the Protein Data Bank [10] [26]. These advancements enable researchers to model complete biological systems involving proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues within a unified deep-learning framework, fundamentally expanding our ability to understand and manipulate cellular machinery at the molecular level.

This comparison guide provides an objective assessment of these next-generation structure prediction tools, focusing on their architectural innovations, performance metrics across diverse biomolecular complexes, and practical applications in research and drug development. By examining experimental data and implementation methodologies, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge needed to select appropriate tools for specific scientific inquiries within the rapidly evolving landscape of computational structural biology.

Architectural Evolution: Technical Foundations Compared

AlphaFold3's Diffusion-Based Architecture

AlphaFold3 introduces a substantially updated architecture that departs significantly from its predecessor. The model replaces AlphaFold2's evoformer with a simpler pairformer module that reduces multiple sequence alignment (MSA) processing burden and focuses on extracting critical evolutionary information more efficiently [10] [27]. Most notably, AF3 implements a diffusion-based structure module that directly predicts raw atom coordinates using an approach similar to generative AI systems like DALL-E and Midjourney [10] [25]. This diffusion process begins with a blurred image of atomic positions that iteratively refines to produce the final structure, enabling the model to learn protein structure at multiple length scales without requiring torsion-based parameterizations or violation losses to enforce chemical plausibility [10].

The diffusion approach provides several advantages: small noise levels train the network to improve local stereochemistry, while high noise levels emphasize large-scale structural organization [10]. To address the hallucination problems common in generative models, AF3 employs a cross-distillation method that enriches training data with structures predicted by AlphaFold-Multimer, teaching the model to represent unstructured regions as extended loops rather than compact structures [10]. Confidence measures are generated through a novel diffusion "rollout" procedure during training, which predicts atom-level errors (pLDDT), pairwise errors (PAE), and distance errors (PDE) to estimate prediction reliability [10].

RoseTTAFold All-Atom's Integrated Approach

RoseTTAFold All-Atom takes a different technical approach, building upon the established three-track network architecture of its predecessor while extending its capabilities to incorporate information on chemical element types of non-polymer atoms, chemical bonds between atoms, and chirality [26] [25]. Rather than implementing a full diffusion approach for structure prediction, RFAA integrates known rules of biochemical interactions into its deep learning framework [25]. However, for protein design tasks, the Baker Lab has developed RoseTTAFold Diffusion All-Atom, which does utilize diffusion methodologies for generating novel biomolecules [23] [25].

The RFAA architecture maintains the integration of information across three tracks: amino acid sequence, distance map, and 3D coordinates [26]. This consistent framework allows the model to process diverse molecular types while preserving the understanding of sequence-structure relationships that made the original RoseTTAFold successful. The model can accept inputs of amino acid sequences, nucleic acid sequences, and small molecule information, producing comprehensive all-atomic biomolecular complexes as output [27].

Table 1: Architectural Comparison Between AlphaFold3 and RoseTTAFold All-Atom

| Architectural Feature | AlphaFold3 | RoseTTAFold All-Atom |

|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | Pairformer with diffusion module | Enhanced three-track network |

| MSA Processing | Simplified MSA embedding | Similar to RoseTTAFold |

| Structure Generation | Diffusion-based, direct coordinate prediction | Non-diffusion (for prediction) |

| Input Handling | Polymer sequences, modifications, ligand SMILES | Amino acid/nucleic acid sequences, chemical element types |

| Equivariance Handling | No global rotational/translational invariance | Maintains architectural consistency |

| Design Capabilities | Structure prediction focused | Separate RoseTTAFold Diffusion All-Atom for design |

Key Architectural Workflows

The fundamental architectural differences between AlphaFold3 and RoseTTAFold All-Atom can be visualized through their distinct computational workflows:

Performance Benchmarking: Experimental Data and Analysis

Protein-Ligand Interaction Accuracy

Experimental evaluations demonstrate that AlphaFold3 achieves substantially improved accuracy over previous specialized tools for predicting protein-ligand interactions. On the PoseBusters benchmark set comprising 428 protein-ligand structures released to the PDB in 2021 or later, AF3 achieved approximately 76% accuracy in predicting structures of proteins interacting with small molecule ligands, defined by the percentage of protein-ligand pairs with pocket-aligned ligand root mean squared deviation (r.m.s.d.) of less than 2 Å [10] [25]. This performance significantly exceeds RoseTTAFold All-Atom, which demonstrated approximately 42% accuracy on the same benchmark, and also outperforms the best traditional docking tools that use structural inputs not available in real-world use cases [10] [25]. Fisher's exact test results show the superiority of AF3 over classical docking tools like Vina is statistically significant (P = 2.27 × 10⁻¹³) and substantially higher than all other true blind docking methods (P = 4.45 × 10⁻²⁵ for comparison with RoseTTAFold All-Atom) [10].

Performance Across Complex Types

Both platforms show distinct performance characteristics across different biomolecular complex types:

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Biomolecular Complex Types

| Complex Type | AlphaFold3 Performance | RoseTTAFold All-Atom Performance | Evaluation Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Ligand | 76% accuracy | 42% accuracy | Pocket-aligned ligand RMSD < 2Å |

| Protein-Nucleic Acid | Far greater accuracy than nucleic-acid-specific predictors | Improved over previous versions | Interface TM-score |

| Antibody-Antigen | Substantially higher than AlphaFold-Multimer v2.3 | Not specifically reported | Interface LDDT |

| Protein-Protein | Improved over AlphaFold-Multimer | Comparable to previous enhanced versions | DockQ score |

| Small Molecule Chirality | Sometimes incorrectly predicted | Generally correct orientation | Structural alignment |

Independent analyses note that while AlphaFold3 exhibits higher overall accuracy in direct prediction-experiment comparisons, both tools demonstrate limitations in specific applications. AF3 occasionally struggles with chirality predictions of small molecules and may hallucinate structures in uncertain regions [25]. RoseTTAFold All-Atom sometimes places small molecules in the correct protein binding pocket but in incorrect orientations [25]. For protein-protein complexes, a critical evaluation revealed that despite high prediction accuracy based on quality metrics such as DockQ and RMSD, both tools show deviations from experimental structures in interfacial contacts, particularly in apolar-apolar packing for AF3 and directional polar interactions [28].

Experimental Validation Workflow

The typical methodology for validating and comparing structure prediction tools involves a standardized workflow:

Practical Implementation: Accessibility and Research Applications

Accessibility and Usage Models

A significant differentiator between these platforms is their accessibility model. AlphaFold3's code has not been released as open-source, though Google DeepMind has provided detailed methodological descriptions and offers access through an AlphaFold server that provides predictions typically within 10 minutes [29] [25]. This approach democratizes access to researchers without extensive computational resources while protecting Google's competitive advantage for its drug discovery arm, Isomorphic Labs [29]. In contrast, RoseTTAFold All-Atom's code is licensed under an MIT License, though its trained weights and data are only available for non-commercial use [29]. This has spurred development of fully open-source initiatives like OpenFold and Boltz-1 that aim to produce programs with similar performance freely available to commercial entities [29].

Research Applications and Limitations

Both tools have demonstrated significant utility across diverse research applications:

Drug Discovery Applications: AlphaFold3 shows particular promise in predicting protein-ligand interactions critical to drug development, offering more accurate representation of binding affinities and pose configurations than traditional docking methods [30]. Its ability to model antibody-antigen interactions with high precision can help generate more specific patent claims for therapeutic antibodies [30]. RoseTTAFold All-Atom provides valuable capabilities for protein-small molecule docking and covalent modification studies [27].

Limitations and Challenges: Both platforms produce static structural images and cannot adequately capture protein dynamics, conformational changes, multi-state conformations, or disordered regions [30] [28]. Molecular dynamics simulations using AF3-predicted structures as starting points show that the quality of structural ensembles deteriorates during simulation, suggesting instability in predicted intermolecular packing [28]. For thermodynamic analyses like alanine scanning, predictions employing experimental structures as starting configurations consistently outperform those with predicted structures, with little correlation between structural deviation metrics and affinity calculation quality [28].

Successful implementation of these structure prediction tools requires specific computational resources and research reagents:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Requirements | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Database Resources | BFD, MGnify, PDB, PDB100, Uniref30 | Multiple sequence alignment and template identification |

| Storage Capacity | ~2.6TB for AlphaFold2 databases | Housing decompressed database files |

| Visualization Tools | LiteMol, PyMOL, ChimeraX | 3D structure visualization and analysis |

| Validation Benchmarks | PoseBusters, CASP datasets | Method performance evaluation |

| Specialized Platforms | DPL3D, Robetta servers | Integrated prediction and visualization |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-performance computing clusters | Running local installations |

Platforms like DPL3D integrate both AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold All-Atom with advanced visualization tools and extensive protein structural databases, providing researchers with comprehensive resources for predicting and analyzing mutant proteins and novel protein constructs [26]. The Robetta server offers continual evaluation through CAMEO and provides both deep learning-based methods and comparative modeling for multi-chain complexes [31].

The emergence of AlphaFold3 and RoseTTAFold All-Atom represents a transformative development in biomolecular structure prediction, extending AI-driven modeling from single proteins to comprehensive biomolecular complexes. While AlphaFold3 currently demonstrates higher accuracy across most categories, particularly for protein-ligand interactions, RoseTTAFold All-Atom remains a powerful open-access alternative with strong performance across diverse molecular types. The field continues to evolve rapidly, with ongoing efforts to address current limitations in predicting protein dynamics, disordered regions, and multi-state conformations.

For researchers and drug development professionals, tool selection depends on specific application requirements, computational resources, and accessibility needs. AlphaFold3's server-based model provides state-of-the-art accuracy with minimal computational investment, while RoseTTAFold All-Atom offers greater customization potential for academic researchers. As these platforms continue to develop and open-source alternatives emerge, the scientific community can anticipate increasingly sophisticated tools that further bridge the gap between computational prediction and experimental structural biology, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and fundamental biological research.

From Algorithm to Application: Practical Use Cases in Drug Discovery and Structural Biology

Speeding Up Experimental Structure Determination with Molecular Replacement

The solution of protein structures via experimental techniques like X-ray crystallography often hinges on solving the "phase problem," a fundamental challenge where critical information is lost during diffraction experiments [32]. Molecular replacement (MR) is the most common method for overcoming this problem, but it traditionally requires a pre-existing structural model (search model) that closely resembles the unknown target structure [33] [34]. The success of MR is historically bottlenecked by the availability of such suitable models.

The advent of highly accurate machine learning-based protein structure prediction tools has dramatically altered this landscape. AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold have emerged as powerful systems that can generate reliable search models de novo from amino acid sequences, thereby accelerating the entire structure determination pipeline [9]. This guide provides an objective comparison of how these two leading AI models are utilized in molecular replacement, framing their performance within the context of experimental structural biology in 2024.

A Primer on Molecular Replacement

Molecular replacement is a computational phasing method used in X-ray crystallography. It relies on placing a known protein structure (the search model) into the crystallographic unit cell of an unknown target structure to derive initial phase information [34] [32].

The MR process, as implemented in software like Phaser in the PHENIX suite, typically involves two key steps [34]:

- Rotation Function: Determines the correct orientation of the search model within the unit cell by comparing the model's calculated Patterson map with the experimentally observed one. This step exploits intramolecular vectors, which depend only on the model's orientation [32].

- Translation Function: Once oriented, the model is shifted to its correct absolute position within the unit cell. This step uses intermolecular vectors that depend on both orientation and position [32].

A successful MR solution is typically indicated by a high Translation Function Z-score (TFZ > 8) and a positive log-likelihood gain (LLG), and is ultimately confirmed by the ability to automatically build and refine a realistic atomic model [34].

The Critical Role of Search Model Quality

The success of MR is exquisitely sensitive to the quality of the search model. Key factors include:

- Sequence Identity: As a rule of thumb, MR is generally straightforward with sequence identity above 40%, becomes difficult between 20-30%, and is very unlikely to succeed below 20% [34].

- Structural Accuracy: The Cα root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the search model and the target is a critical metric. An RMSD of less than 1.5 Å is preferable, and success is very unlikely above 2.5 Å [33] [34].

- Model Completeness: For a successful solution, the search model must typically cover at least 50% of the total structure [33].

AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold: Core Architectures

The high accuracy of AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold stems from their sophisticated deep-learning architectures, which are trained to infer structural constraints from evolutionary information.

AlphaFold2 Architecture

AlphaFold2 uses a novel neural network architecture that incorporates physical, biological, and geometric constraints of protein structures [11] [35]. Its system can be broken down into three main modules:

- Feature Extraction Module: Searches sequence databases (e.g., Uniref90, MGnify) to construct a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) and identifies homologous structures from the PDB to create template information [35].

- Encoder Module (Evoformer): A core innovation of AlphaFold2, the Evoformer, jointly processes the MSA and a pair representation that encodes relationships between residues. It uses attention mechanisms to reason about spatial and evolutionary relationships, allowing a concrete structural hypothesis to emerge and be refined [11] [35].

- Structure Decoding Module: Converts the processed representations from the Evoformer into atomic 3D coordinates. It uses an equivariant transformer and operates on residue frames, iteratively refining the structure through a process called "recycling" [11] [35]. The module outputs a per-residue confidence score (pLDDT) on a scale of 0-100 [36].

RoseTTAFold Architecture

RoseTTAFold, developed by the Baker laboratory, employs a different but equally innovative three-track neural network [22]. This architecture simultaneously processes information in 1D (protein sequence), 2D (inter-residue distances and orientations), and 3D (atomic coordinates) [22]. Information flows back and forth between these tracks, allowing the network to collectively reason about relationships within and between sequences, distances, and coordinates [22].

The molecular replacement workflow leveraging these AI-predicted models is summarized in the diagram below.

Performance Comparison in Molecular Replacement

Both AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold have demonstrated a remarkable ability to produce models sufficient for successful molecular replacement, even in cases where traditional search models from the PDB have failed.

Quantitative Accuracy Benchmarks

Extensive benchmarking studies have quantified the performance of these tools in structural modeling. The following table summarizes key comparative metrics from independent assessments.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold

| Metric | AlphaFold2 | RoseTTAFold | Notes & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone Accuracy (Cα RMSD) | Median of 0.96 Å (r.m.s.d.95) [11] | Similar results to AlphaFold2 in CASP14 [22] | As measured in the blind CASP14 competition. |

| Peptide Structure Prediction (10-40 aa) | Predicts α-helical, β-hairpin, and disulfide-rich peptides with high accuracy [37] | Not specifically benchmarked in search results | Benchmark against 588 experimentally determined NMR structures [37]. |

| Key Architectural Strengths | Evoformer for MSA/pair representation integration; iterative refinement via recycling [11] [35] | Three-track network (1D, 2D, 3D) for integrated reasoning [22] | Different architectural approaches leading to high accuracy. |

| Impact on MR Success | Enables MR where traditional PDB models fail; widely integrated into crystallographic software [9] | Successfully used to predict challenging crystallography structures [22] | Both have demonstrably accelerated experimental structure solution. |

Performance in Challenging MR Scenarios

The true test of an AI-predicted model is its performance in difficult molecular replacement cases where no close homolog exists in the PDB.

- Novel Folds and De Novo Designs: AlphaFold2 has been successfully used for MR in instances where the target protein had a novel fold or was a de novo design, scenarios that are traditionally very challenging for MR [9].

- Low-Sequence Identity Targets: While traditional MR struggles below 30% sequence identity, the high accuracy of AF2 and RoseTTAFold models expands the range of solvable targets. One study noted that AF2 predictions could enable MR even when the Cα RMSD to the target was less than 2 Å, a threshold that is often problematic for traditional methods [33].

Experimental Protocols for MR with AI Models

To ensure the highest chance of success, researchers should follow a structured workflow when using AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold for molecular replacement. The key steps and requisite tools are outlined below.

Step-by-Step Workflow

- Prediction Generation: Submit the target protein's amino acid sequence to either the AlphaFold2 server (via the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database or ColabFold) or the RoseTTAFold server to generate a 3D structural prediction. ColabFold is a popular alternative that offers faster prediction times by using MMseqs2 for MSA construction [36].

- Model Preparation & Truncation: This is a critical step. The raw AI output is rarely the ideal MR search model.

- Remove Low-Confidence Regions: Use the pLDDT score (for AlphaFold2) to identify and remove flexible loops or low-confidence termini. A common practice is to truncate residues with pLDDT < 70 [36] [9].

- Domain Splitting: For multi-domain proteins, use tools like Slice'n'Dice (in CCP4) or processpredictedmodel (in PHENIX) to split the prediction into individual structural domains based on the Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) plot. These domains can be placed separately in MR [9].

- Structural Pruning: Software like Sculptor can automatically prepare and truncate models based on sequence alignment and confidence metrics, which is highly recommended for models with lower predicted accuracy [34].

- Molecular Replacement: Use the prepared model(s) in an MR program.

- Recommended Software: Phaser (within PHENIX or CCP4) is the current gold-standard for likelihood-based MR [34].

- Input Parameters: Provide the processed model and the experimental reflection data. Phaser will require an estimate of the model's deviation from the target; for a high-confidence AF2/RoseTTAFold model, an RMSD of 0.5-1.0 Å is a reasonable starting point [34].

- Validation and Refinement: A successful MR solution (TFZ > 8, LLG > 0) must be followed by rigorous validation.

- Automated Rebuilding: Immediately run automated model-building tools like phenix.autobuild or Buccaneer.

- Refinement: Conduct iterative cycles of refinement (e.g., with phenix.refine) and manual model building in Coot [9].

- Validation Metrics: The final structure should have good stereochemistry and a low R-free factor. The ability to build a complete, chemically sensible model is the single best indicator of a correct solution [34].

The essential computational tools that form the modern structural biologist's toolkit for this workflow are listed below.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Guided Molecular Replacement

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 / ColabFold | Structure Prediction Server | Generates a 3D atomic model from an amino acid sequence. |

| RoseTTAFold Server | Structure Prediction Server | Alternative to AlphaFold2 for generating 3D models. |

| PHENIX/Phaser | Software Suite | Industry-standard software for performing molecular replacement and subsequent structure refinement. |

| CCP4/Slice'n'Dice | Software Suite | Alternative crystallography suite; includes tools for splitting AF2 models into domains. |

| Sculptor | Software Utility | Prepares and truncates search models for MR based on sequence alignment and quality estimates. |

| Coot | Software Application | For manual visualization, model building, and refinement of crystal structures. |

Advanced Applications: Beyond Single Protein Chains

The capabilities of these AI models have expanded beyond single monomeric proteins, opening new frontiers for determining complex structures.

- Protein Complexes with AlphaFold-Multimer: A specialized version of AlphaFold2, AlphaFold-Multimer, was trained to predict the structures of hetero- and homo-multimeric complexes [9]. This has been used in large-scale interaction screens, such as mapping the yeast interactome, and to generate models for multi-subunit complexes that can be used as MR search models [9].

- Integrative Modeling with Cryo-EM: For cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and electron tomography (cryo-ET), which sometimes yield maps with regions of lower resolution, AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold models have proven invaluable. They can be fitted into lower-resolution density maps to provide atomic-level details and validate the experimental map. A landmark example was the determination of the nuclear pore complex structure, where AF2 models of components were fitted into a ~23 Å resolution map [9].

- Ligand and Nucleic Acid Modeling with Next-Gen Tools: 2024 has seen the release of more advanced models capable of predicting complexes with non-protein components.

- AlphaFold3 can predict the joint structure of complexes including proteins, nucleic acids, ions, and small molecule ligands with high accuracy, surpassing many specialized tools [10].

- RoseTTAFold All-Atom is a similar next-generation tool trained to model assemblies containing proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, and metals [22].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for choosing the right tool based on the composition of the assembly being studied.

The data and experimental protocols summarized in this guide unequivocally demonstrate that both AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold have become indispensable tools for accelerating experimental structure determination via molecular replacement. Their ability to generate accurate search models de novo has solved a critical bottleneck in structural biology.

While direct, head-to-head comparisons in large-scale MR trials are still limited, the evidence shows that both systems achieve the level of accuracy (often with Cα RMSD < 1.5 Å) required to phase structures by MR, even for targets with no close structural homologs. The choice between them may often come down to practical considerations like integration into existing lab workflows or the specific biological question—for instance, using AlphaFold-Multimer for protein complexes or exploring the new RoseTTAFold All-Atom and AlphaFold3 capabilities for ligand interactions.

For researchers in drug development, the implications are profound. The speed at which a protein structure can be determined has been drastically increased, facilitating faster target characterization and structure-based drug design. As these AI models continue to evolve and integrate more deeply into structural biology software suites, their role as a foundational technology in biomedical research is firmly established.

Predicting Protein-Protein and Protein-Ligand Interactions

The accurate prediction of biomolecular interactions is a cornerstone of modern structural biology, with profound implications for understanding cellular function and advancing rational drug design. For years, the prediction of protein-protein and protein-ligand interactions relied on specialized computational tools with varying degrees of accuracy. The emergence of deep learning has revolutionized this field, with AlphaFold2 (AF2) and RoseTTAFold (RF) representing landmark achievements in protein structure prediction. The year 2024 has seen significant evolution in this landscape, with the release of more sophisticated models like AlphaFold 3 (AF3) and RoseTTAFold All-Atom (RFAA) that extend capabilities to complex biomolecular interactions. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance, methodologies, and applicability of these tools for predicting protein-protein and protein-ligand interactions, based on the most current research and benchmarking studies.

Performance Comparison of Major Prediction Tools

Quantitative Accuracy Across Interaction Types