Assessing Sample Variability in RNA-seq Datasets: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust and Reproducible Transcriptomic Analysis

This article provides a complete framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to understand, assess, and manage sample variability in RNA-seq experiments.

Assessing Sample Variability in RNA-seq Datasets: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust and Reproducible Transcriptomic Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a complete framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to understand, assess, and manage sample variability in RNA-seq experiments. Covering foundational concepts to advanced validation techniques, it details how biological and technical variability impact differential expression analysis. The guide synthesizes the latest empirical evidence on sample size requirements, offers best practices for normalization and batch effect correction, and provides methodologies for validating findings against orthogonal data and gold-standard benchmarks. By addressing these four core intents, this resource empowers scientists to design and execute RNA-seq studies that minimize false discoveries and maximize reliable biological insights for biomedical and clinical applications.

Understanding the Sources and Impact of RNA-seq Variability

Defining Biological vs. Technical Variability in Transcriptomic Data

In the field of transcriptomics, the accurate interpretation of gene expression data fundamentally hinges on the ability to distinguish between two primary sources of variation: biological variability, which arises from genuine physiological differences between cells or organisms, and technical variability, which is introduced by the measurement technology itself [1]. Next-generation sequencing technologies, particularly RNA-seq and single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq), have revolutionized our capacity to profile transcriptomes, offering a broader dynamic range and the ability to detect novel transcripts compared to earlier methods like microarrays [1] [2]. However, these technologies are not without their own inherent limitations and sources of noise. The precision of these tools is constrained by factors such as the low sampling fraction of the total mRNA pool and platform-specific biases [3]. For single-cell analysis, challenges are further amplified by the minimal starting material, necessitating amplification steps that can introduce significant distortions [1]. Systematically characterizing and accounting for these technical artifacts is a prerequisite for extracting meaningful biological insights, especially in the context of a broader thesis on assessing sample variability in RNA-seq datasets. Failure to do so can lead to the misinterpretation of technical noise as biological signal, thereby compromising the validity of downstream conclusions in basic research and drug development.

Biological Variability

Biological variability refers to the natural differences in gene expression that occur between distinct biological entities, such as different individuals, cells, or even the same cell over time. This variability is the primary source of interest in most studies, as it underpins fundamental biological processes and phenomena [1].

- Cell-to-Cell Heterogeneity: Even within a population of genetically identical cells, individual cells exhibit stochastic gene expression. This heterogeneity can drive processes like cell fate decisions [4].

- Diverse Cell Populations: Complex tissues comprise multiple cell types. Single-cell transcriptomics is powerful for studying this diversity, which is averaged out in bulk RNA-seq [1].

- Developmental Dynamics: During processes like embryonic development or differentiation, cells undergo rapid and coordinated changes in gene expression. Single-cell analyses can reconstruct these trajectories [1].

- Stochastic Expression: Gene expression is an inherently probabilistic process involving transcription and translation, leading to non-genetic heterogeneity in isogenic cell populations [1].

Technical Variability

Technical variability encompasses all fluctuations in measured gene expression levels that are introduced by the experimental and analytical protocols. This type of variability does not reflect the true biological state of the system and must be minimized and controlled for [1] [3].

- Low Starting Material and Amplification Bias: In scRNA-seq, the minute amount of RNA from a single cell requires significant amplification, which can preferentially amplify some transcripts over others and lead to 3' end bias [1].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing Depth: Differences in library construction efficiency and the total number of sequenced reads per sample can create substantial technical variation. A low sequencing depth results in a low sampling fraction, making expression estimates less reliable [3].

- Platform-Specific Biases: The choice of sequencing technology (e.g., full-length Smart-seq2 vs. 3'-end focused 10x Genomics) introduces distinct profiles of technical noise [4].

- Alignment and Quantification Inconsistencies: The bioinformatic processing of raw sequencing data, including the algorithms used for read alignment and transcript quantification, is a significant source of technical variation across samples [2] [5].

Table 1: Characteristics of Biological vs. Technical Variability

| Feature | Biological Variability | Technical Variability |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | inherent biological processes | measurement technology & protocol |

| Reproducibility | reproducible biological signal | stochastic and protocol-dependent |

| Influence of Sequencing Depth | independent | decreases with increasing depth |

| Cell-to-Cell Dependence | can be correlated (e.g., in pathways) | largely independent between cells |

| Primary Interest | the signal of interest | noise to be characterized & removed |

Quantitative Characterization of Technical Variability

Technical variability in transcriptomic data is not merely a theoretical concern but has been quantitatively demonstrated across multiple experimental contexts. In bulk RNA-seq, the sampling fraction—the proportion of mRNA molecules in a library that is actually sequenced—is remarkably low, estimated at approximately 0.0013% per lane on Illumina GAIIx technology [3]. This low fraction is a fundamental source of stochastic sampling noise. Simulation studies modeling this process reveal that technical replicates can show substantial disagreement in the estimated expression levels of genes, even at moderate to high coverage [3]. Empirical data further corroborates this; in scRNA-seq data, the technical variability is often so pronounced that it can mask underlying biological signals. For instance, differences in cell cycle stage across individual cells can act as a major confounding factor, introducing a pattern of variation that is biological in origin but may not be the focus of the study [1]. The impact of technical variability is also highly dependent on expression levels. Exon detection has been shown to be highly inconsistent between technical replicates when the average coverage is less than 5 reads per nucleotide [3].

Table 2: Impact of Technical Factors on RNA-seq Data Quality

| Technical Factor | Impact on Data | Empirical Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Depth | affects detection sensitivity & quantification accuracy | exon detection is inconsistent with <5 reads/nucleotide coverage [3] |

| Sampling Fraction | introduces stochastic noise | ~0.0013% of molecules sequenced leads to substantial variation [3] |

| Quantification Method | influences linearity & inter-sample variability | Kallisto & Salmon TPM show high linearity; raw counts perform poorly [5] |

| Sequencing Platform | creates platform-specific bias | variability differences between full-length & 3'-end protocols [4] |

| Amplification (scRNA-seq) | introduces 3' bias & transcript drop-outs | leads to high technical variability & missing values [1] |

Methodologies for Measuring and Decomposing Variability

Experimental Design for Variability Assessment

A robust experimental design is the first line of defense against the confounding effects of technical variability.

- Incorporation of Technical Replicates: Sequencing the same library across multiple lanes or runs allows for the direct quantification of technical variation introduced by the sequencing process itself [3].

- Use of Spike-In Controls: Adding known quantities of synthetic RNA molecules (e.g., ERCC spike-ins) to each sample provides an external standard to track technical performance and distinguish technical from biological effects [4].

- Balanced Batch Design: When large experiments must be processed in multiple batches, samples from different experimental groups should be distributed evenly across batches to avoid confounding batch effects with biological signals.

Computational Metrics and Tools for Quantifying Variability

Once data is generated, a variety of computational metrics can be applied to quantify expression variability. A systematic evaluation of 14 variability metrics identified scran as a top-performing method for measuring cell-to-cell variability in scRNA-seq data due to its strong all-round performance in handling data sparsity and mean-variance relationships [4]. Other metrics include generic statistical measures like the coefficient of variation (CV) and Fano factor, as well as more specialized methods designed for transcriptomic data.

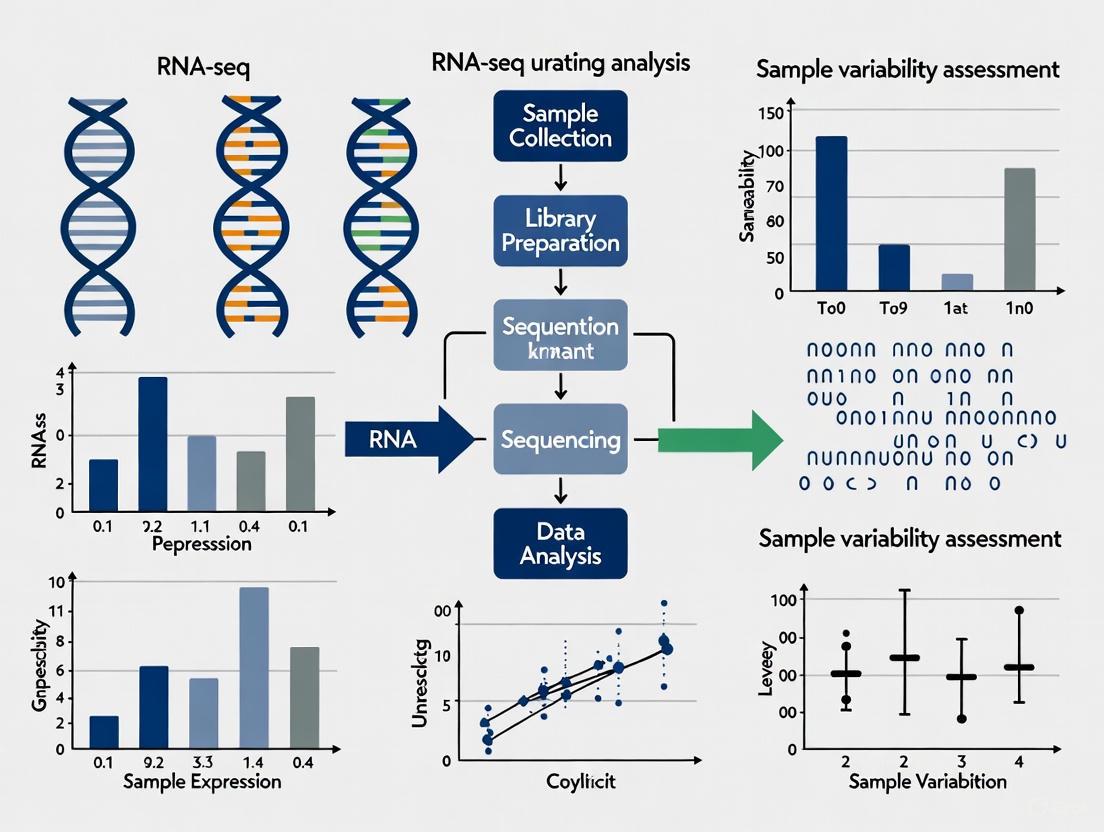

The following workflow diagram illustrates the primary steps for decomposing variability in a single-cell RNA-seq experiment, from experimental design to computational analysis.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Deconvolving Variability in scRNA-seq

Benchmarking of RNA-seq Quantification and Analysis Pipelines

The choice of bioinformatic pipelines significantly impacts the technical variability in the final gene expression estimates. A comprehensive assessment of 192 alternative RNA-seq analysis pipelines revealed that the specific combination of trimming algorithms, aligners, and quantification methods can lead to widely differing results [2]. For studies that rely on linear models, such as deconvolution of bulk tissue data into cell-type-specific signals, the quantification unit is critical. Transcripts Per Million (TPM) from pseudoalignment tools like Kallisto and Salmon demonstrate superior linearity compared to raw counts or FPKM values, making them better suited for such applications [5]. This highlights that the computational workflow is not just a procedural step but an integral part of the technical framework that must be carefully selected and benchmarked.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Tools

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Synthetic RNA molecules added to lysates to monitor technical performance and quantify technical variance [4]. |

| TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit | A common commercial kit for constructing strand-specific RNA-seq libraries, a key source of technical variability between labs [2]. |

| 10x Genomics Chromium Controller | A droplet-based system for high-throughput single-cell RNA-seq library preparation, introducing platform-specific technical biases [4]. |

| Salmon / Kallisto | Alignment-free quantification tools that estimate transcript abundance in TPM with high accuracy and linearity, reducing computational variability [5]. |

| scran R Package | A computational method identified as a top-performing metric for robustly quantifying cell-to-cell variability in scRNA-seq data [4]. |

| TopHat2 / STAR | Alignment-based quantification methods that map reads to a reference genome, with performance varying based on the specific pipeline [2] [5]. |

The distinction between biological and technical variability is fundamental to the rigorous analysis of transcriptomic data. Technical variability, originating from the low sampling fraction of sequencing, amplification biases, and algorithmic differences, is a substantial factor that cannot be ignored [1] [3]. To mitigate its impact and ensure biological conclusions are robust, researchers should adopt a multi-faceted strategy: First, design experiments explicitly to measure technical noise by including technical replicates and spike-in controls. Second, sequence deeply to ensure sufficient coverage, particularly for detecting mid-to-low abundance transcripts. Third, select computational pipelines judiciously, opting for quantification methods like Salmon or Kallisto's TPM that demonstrate superior technical performance for specific tasks like deconvolution [5]. Finally, apply specialized variability metrics like scran for single-cell data to accurately capture cell-to-cell heterogeneity beyond what mean expression levels can reveal [4]. By systematically implementing these practices, researchers can confidently deconvolve the complex sources of variation in their data, paving the way for discoveries that are both biologically meaningful and technically sound.

How Sample Variability Leads to False Positives and Inflated Effect Sizes

In the realm of genomics research, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful tool for measuring gene expression and identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between experimental conditions. However, the reliability of these findings is fundamentally constrained by sample variability—a challenge that permeates study design, statistical analysis, and biological interpretation. Sample variability in RNA-seq experiments arises from multiple sources, including biological heterogeneity between specimens, technical variations in library preparation and sequencing, and environmental factors affecting sample quality. When unaccounted for, this variability systematically distorts research outcomes, leading to an overabundance of false positive findings and inflated estimates of effect sizes.

This phenomenon represents a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals who depend on accurate transcriptomic data for making discovery decisions and advancing therapeutic candidates. The broader thesis of assessing sample variability centers on recognizing that high-dimensional RNA-seq data requires rigorous statistical handling to separate true biological signals from noise. Evidence suggests that underpowered studies with insufficient replicates remain prevalent in the literature, threatening the reproducibility of genomic findings and potentially misdirecting research resources. Understanding how variability propagates through analytical pipelines is therefore essential for designing robust experiments and drawing valid biological conclusions.

Core Statistical Concepts: Error Types and Effect Size Distortion

Fundamental Statistical Errors in Hypothesis Testing

In statistical hypothesis testing for RNA-seq analysis, researchers typically test a null hypothesis (H0) that no expression difference exists between conditions against an alternative hypothesis (H1) that a difference does exist. The outcome of this testing framework is subject to two primary types of statistical errors:

Type I Errors (False Positives): Occur when the null hypothesis is incorrectly rejected, meaning a gene is falsely identified as differentially expressed. The probability of committing a Type I error is denoted by alpha (α), typically set at 0.05 [6].

Type II Errors (False Negatives): Occur when the null hypothesis is incorrectly retained, meaning a truly differentially expressed gene is missed. The probability of a Type II error is denoted by beta (β) [6].

Statistical power, defined as 1-β, represents the probability of correctly detecting a true effect. The ideal power for a study is conventionally set at 0.8 (80%), though many biomedical studies fall dramatically short of this standard, with some fields averaging as low as 21% power [6] [7].

The Mechanism of Effect Size Inflation

Effect size inflation, also known as Type M (magnitude) error, occurs when the estimated magnitude of differential expression is systematically exaggerated relative to the true biological effect [8]. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in studies with high sample variability and small sample sizes due to a statistical selection artifact called the "winner's curse."

When true effect sizes are small or moderate relative to sampling variability, only those experiments that, by chance, observe larger effect sizes will achieve statistical significance. This creates a truncated distribution where only the most extreme estimates are selected for publication, systematically biasing the literature toward inflated effects [9] [8]. As one analysis demonstrated, genes with larger fold changes estimated by DESeq2 and edgeR were more likely to be identified as DEGs even in permuted datasets where no true differences existed [10].

Diagram 1: The pathway from true effects to inflated published estimates due to significance filtering and sampling variability.

Empirical Evidence: Quantitative Findings from RNA-Seq Studies

Impact of Sample Size on False Discovery Rates

Recent large-scale empirical studies have quantified how sample size directly affects false discovery rates (FDR) in RNA-seq experiments. One comprehensive analysis of murine RNA-seq data with sample sizes up to N=30 per group revealed striking patterns:

Table 1: False Discovery Rates at Different Sample Sizes (Based on N=30 Gold Standard)

| Sample Size (N) | Median False Discovery Rate | Variability Across Trials | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=3 | 28-38% depending on tissue | Extremely high (10-100%) | Highly unreliable results |

| N=5 | ~20% | High variability | Fails to recapitulate full signature |

| N=6-7 | <50% (for 2-fold changes) | Marked reduction in variability | Minimum threshold for consistent results |

| N=8-12 | Approaching minimization | Further reduced variability | Significant improvement in recapitulating full experiment |

| N=30 | Gold standard benchmark | Minimal variability | Captures true biological effects most accurately |

This study found that experiments with N=4 or less produced "highly misleading" results with elevated false positive rates and failure to detect genes later identified with larger sample sizes [9]. The variability in false discovery rates across different random subsamples was particularly extreme at low sample sizes—in lung tissue, the FDR ranged between 10% and 100% depending on which N=3 mice were selected for each genotype [9].

Sample Size Recommendations Across Studies

Multiple research groups have independently arrived at similar conclusions regarding minimum sample size requirements:

Table 2: Sample Size Recommendations from Various RNA-Seq Studies

| Study | Recommended Minimum N | Context and Qualifications |

|---|---|---|

| Optimized murine sample sizes [9] | N=6-7 (minimum), N=8-12 (recommended) | For 2-fold expression differences; more is always better within N=30 range |

| Schurch et al. [7] | N=6 (minimum), N=12 (ideal) | Required for robust DEG detection; increases to N=12 to identify majority of DEGs |

| Lamarre et al. [7] | N=5-7 | Based on optimal FDR threshold formula of 2^-N for thresholds of 0.05-0.01 |

| Baccarella et al. [7] | N=7 | Cautioned against fewer than 7 replicates, reporting high heterogeneity between results |

| Ching et al. [7] | N=10 | To achieve ≥80% statistical power given budget constraints |

| Cui et al. [7] | N=10 | Based on TCGA data subsampling; needed for adequate overlap of DEGs |

Despite these recommendations, a survey of the literature reveals that approximately 50% of human RNA-seq studies and 90% of non-human studies use sample sizes at or below six replicates per condition [7]. This demonstrates a concerning gap between empirical evidence and common practice.

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Design and Analytical Strategies

RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow and Quality Control

Proper RNA-seq experimental design involves multiple critical steps where variability can be introduced and potentially mitigated:

Diagram 2: RNA-seq workflow highlighting key points where variability is introduced and should be controlled.

Critical steps for mitigating variability include [11]:

- Experimental Controls: Harvesting cells or sacrificing animals at the same time of day, processing controls and experimental conditions simultaneously, and using intra-animal, littermate, and cage-mate controls when possible.

- Technical Consistency: Performing RNA isolation and library preparation for all samples on the same day by the same researcher to minimize batch effects.

- Sequencing Considerations: Sequencing controls and experimental conditions together in the same run to avoid batch effects.

Statistical Methods for Handling Variability

Normalization Techniques

Normalization addresses technical variability by adjusting raw counts to remove biases such as sequencing depth and library composition:

Table 3: Common Normalization Methods in RNA-Seq Analysis

| Method | Sequencing Depth Correction | Gene Length Correction | Library Composition Correction | Suitable for DE Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPM (Counts per Million) | Yes | No | No | No |

| RPKM/FPKM | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| TPM (Transcripts per Million) | Yes | Yes | Partial | No |

| Median-of-Ratios (DESeq2) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values, edgeR) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

More advanced methods like those implemented in DESeq2 and edgeR correct for differences in library composition, which is particularly important when a few highly expressed genes consume a large fraction of sequencing reads [12].

Differential Expression Analysis Tools

Different statistical methods show varying performance in controlling false positives:

Parametric Methods (DESeq2, edgeR, limma-voom): Assume data follows a specific distribution (typically negative binomial). These methods can show exaggerated false positives in population-level studies with large sample sizes, with actual FDRs sometimes exceeding 20% when the target was 5% [10].

Non-parametric Methods (NOISeq, dearseq, Wilcoxon rank-sum test): Make fewer distributional assumptions but require larger sample sizes for good power. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test has demonstrated superior FDR control in large-sample scenarios, though it has almost no power when sample size is smaller than 8 per condition [10].

Quality Weighting Approaches: Methods like

voomWithQualityWeightsin the limma package model both sample-level and observational-level variability, down-weighting more variable samples to improve power and reduce false discoveries [13].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Variability Control

| Item | Function | Variability Control Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., RNAlater) | Preserves RNA integrity in fresh tissues | Minimizes degradation variability between samples |

| Poly(A) Selection or rRNA Depletion Kits | Enriches for mRNA or removes ribosomal RNA | Reduces technical variability in library composition |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Tags individual mRNA molecules before amplification | Accounts for PCR amplification biases and duplicates |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kits | Maintains transcriptional direction information | Improves annotation accuracy, reduces misassignment errors |

| External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) Spikes | Synthetic RNA controls added to samples | Monitors technical performance across batches |

| Quality Control Instruments (Bioanalyzer, TapeStation) | Assesses RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | Identifies degraded samples before sequencing |

| Normalization Tools (DESeq2, edgeR, limma) | Statistical adjustment of count data | Corrects for technical biases in downstream analysis |

| Batch Effect Correction Software (ComBat, RUV) | Removes systematic non-biological variation | Addresses technical artifacts from processing batches |

The evidence consistently demonstrates that insufficient attention to sample variability systematically distorts RNA-seq findings through false positives and inflated effect sizes. The core solution involves both adequate sample sizes—empirically shown to require at least 6-8 replicates per group, with 8-12 being substantially better—and appropriate statistical methods that account for multiple sources of variability. No analytical sophistication can fully compensate for inadequate biological replication, as underpowered experiments fundamentally lack the ability to distinguish true signals from noise.

Researchers planning RNA-seq experiments should prioritize biological replication over sequencing depth once a reasonable depth (typically 20-30 million reads per sample) is achieved. Additionally, employing quality control measures throughout the experimental workflow and selecting analytical methods that explicitly model sample-level variability can further enhance reproducibility. As the field moves toward more rigorous standards, recognition of how sample variability impacts research validity remains fundamental to generating reliable transcriptomic insights and advancing robust biological discoveries.

The Critical Role of Biological Replicates in Variance Estimation

The high-dimensional and heterogeneous nature of transcriptomics data from RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) experiments presents a substantial challenge for routine downstream analyses, including differential expression and enrichment analysis [14]. In this context, biological replicates—samples collected from distinct biological units (e.g., different animals, patients, or cell culture passages)—are not merely technical repetitions but the fundamental basis for reliable statistical inference. They enable researchers to estimate the natural biological variation present within a population, which is essential for distinguishing true experimental effects from random variability. Without adequate replication, even sophisticated analytical pipelines produce unstable results that fail to validate in subsequent studies. Despite well-established recommendations, RNA-Seq experiments are often limited to a small number of biological replicates due to considerable financial and practical constraints [14]. A survey cited in recent literature indicates that approximately 50% of RNA-Seq experiments with human samples use six or fewer replicates per condition, with this ratio growing to 90% for non-human samples [14]. This tendency toward underpowered studies creates a replicability crisis in the field, compelling a detailed examination of how biological replicates underpin variance estimation and ultimately, research credibility.

The Statistical Foundation of Biological Replication

Biological variability arises from genuine differences among individuals—due to genetics, environment, or stochastic biological processes—unaffected by the measurement technology [3]. In RNA-Seq, the total variability in observed read counts for a gene stems from two primary sources: technical variance (from library preparation, sequencing depth, and alignment) and biological variance (true variation in gene expression across different biological subjects). While technical variability can be reduced through improved laboratory protocols and deeper sequencing, biological variability is an inherent property of the system under study and must be captured through replication.

The statistical power of a differential expression analysis—the probability of correctly detecting a true expression change—depends critically on the accurate estimation of this biological variance. Variance estimates derived from only two or three replicates are highly unstable, leading to unreliable statistical tests. These undersampled estimates can be either too large or too small, directly increasing the rate of both false positives (incorrectly declaring a gene differentially expressed) and false negatives (failing to detect a true difference) [12] [14]. Advanced statistical models used in tools like DESeq2 and edgeR explicitly use the variation between biological replicates to moderate gene-wise variance estimates, shrinking extreme values towards a common trend to provide more stable results [12]. This process, however, requires sufficient degrees of freedom provided by an adequate number of replicates to be effective.

Table 1: Impact of Replicate Number on Statistical Power in RNA-Seq Analysis

| Replicates per Condition | Statistical Power | Variance Estimation Stability | Risk of False Discoveries | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | Very Low | Unstable, often inaccurate | Very High | Exploratory, pilot studies only; not for hypothesis testing |

| 3 | Low to Moderate | Moderately stable but often imprecise | High | Common but sub-optimal minimum; interpret results with caution |

| 5-7 | Moderate | Acceptably stable | Moderate | Often sufficient for experiments with large effect sizes |

| 10+ | High | Stable and reliable | Low | Essential for detecting subtle expression changes or in highly heterogeneous populations |

Quantitative Evidence: How Underpowered Studies Compromise Replicability

Recent large-scale analyses have quantified the severe consequences of inadequate replication. A 2025 study performed 18,000 subsampled RNA-Seq experiments based on real gene expression data from 18 different datasets to systematically evaluate replicability [14]. The findings demonstrate that differential expression and enrichment analysis results from underpowered experiments are unlikely to replicate well. This low replicability, however, does not necessarily imply uniformly low precision; some datasets achieved high median precision despite low recall, indicating that while many true positives are missed, the genes identified as significant are often correct [14].

The relationship between replicate number and outcome reliability is not linear. The same study found that while all datasets showed poor replicability with very small cohorts (n < 5), performance trajectories diverged substantially with increasing replicates. In certain data sets with lower inherent biological variability, just five replicates could achieve reasonable precision, whereas other, more heterogeneous populations required ten or more replicates to achieve comparable reliability [14]. This underscores that "adequate" replication cannot be universally defined but depends on the underlying variability of the biological system.

Table 2: Replicability Metrics from Subsample Analysis of RNA-Seq Datasets

| Cohort Size (n) | Median Replicability (IQR) | Median Precision | Median Recall | Typical Range of DEGs Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0.25 (0.18-0.35) | 0.72 | 0.21 | 150-2000 |

| 5 | 0.41 (0.29-0.55) | 0.81 | 0.38 | 800-3500 |

| 7 | 0.52 (0.38-0.67) | 0.85 | 0.51 | 1200-4500 |

| 10 | 0.64 (0.49-0.77) | 0.88 | 0.65 | 1800-5500 |

Beyond differential expression, the inconsistency propagates to downstream enrichment analyses. When different subsamples from the same population identify different sets of significant genes, the resulting biological interpretations—which pathways or processes are considered affected—also vary dramatically. This fundamentally undermines the ability to draw meaningful biological conclusions from underpowered experiments.

Practical Experimental Design: Mitigating Variance Through Replication

Determining Optimal Replicate Numbers

While three replicates per condition remains unfortunately common in published literature, methodological research suggests this is generally insufficient [12] [14]. Schurch et al. (2016) estimated that at least six biological replicates per condition are necessary for robust detection of differentially expressed genes, increasing to at least twelve replicates when the goal is to identify the majority of DEGs across all fold changes [14]. Other researchers have suggested five to seven replicates for typical false discovery rate thresholds of 0.05-0.01 [14]. The optimal number ultimately depends on several factors:

- Effect size of interest: Smaller expression changes require more replicates for detection

- Biological variability: More heterogeneous systems require greater replication

- Sequencing depth: Deeper sequencing can partially compensate for fewer replicates but is not a substitute

- Financial constraints: Budget-limited optimal design often favors more replicates over deeper sequencing

For standard differential expression analysis, approximately 20-30 million reads per sample is often sufficient, allowing researchers to allocate resources toward additional replicates rather than excessive sequencing depth [12].

Managing Technical Variability and Batch Effects

Technical variability in RNA-Seq arises from multiple sources, including library preparation, sequencing lane effects, and the surprisingly low sampling fraction of the total mRNA pool—estimated at just 0.0013% of available molecules in a typical Illumina GAIIx lane [3]. While biological variation generally exceeds technical variation, both must be controlled through proper experimental design [11].

Batch effects—systematic technical differences between groups of samples processed at different times or by different personnel—represent a particularly insidious source of false positives. To mitigate these effects:

- Process all samples for each experimental group simultaneously whenever possible

- Randomize sample processing order rather than grouping by experimental condition

- Include biological replicates collected and processed at different times

- Record all processing variables (dates, technicians, reagent lots) for inclusion in statistical models

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Variance Studies

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Role in Variance Control |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Kits | Enrichment for messenger RNA from total RNA | Reduces rRNA contamination; minimizes technical variation in library composition |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kits | Construction of sequencing libraries that preserve transcript strand information | Improves annotation accuracy; reduces misassignment errors that inflate perceived variance |

| UMI (Unique Molecular Identifier) Adapters | Molecular tagging of individual RNA molecules during reverse transcription | Enables precise quantification by correcting for PCR amplification bias |

| External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) Spikes | Synthetic RNA molecules added to samples in known quantities | Monitors technical performance across samples and batches; benchmarks sensitivity |

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) Standardization Reagents | Assessment of RNA quality before library preparation | Ensures consistent input material quality; prevents degradation-induced variance |

Methodological Protocols for Variance Assessment

Bootstrapping Procedure for Replicability Estimation

For researchers constrained to small cohort sizes, a simple bootstrapping procedure can help estimate the expected replicability and precision of their data [14]. This method uses resampling to simulate the effects of increased replication:

- Begin with your complete dataset containing all biological replicates

- Randomly subsample without replacement to create smaller cohorts (e.g., select n=3 from your n=6 replicates)

- Perform differential expression analysis on this subsample

- Repeat this process many times (e.g., 100-1000 iterations) with different random subsamples

- Calculate the overlap of significant genes between pairs of subsamples using the Jaccard index or similar metric

- The average overlap across all pairs provides an estimate of expected replicability

This procedure correlates strongly with observed replicability and precision metrics and can help researchers determine whether their current sample size is adequate or if conclusions should be appropriately tempered [14]. A standalone repository to perform these bootstrapped analyses is available via GitHub (https://github.com/pdegen/BootstrapSeq) [14].

Quality Control and Normalization for Variance Stabilization

Proper preprocessing and normalization are essential for accurate variance estimation. The workflow should include:

- Initial Quality Control: Tools like FastQC or multiQC assess sequence quality, adapter contamination, and other potential issues [12]

- Read Trimming: Removal of adapter sequences and low-quality bases using Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, or fastp [12]

- Alignment and Quantification: Mapping to a reference genome/transcriptome using STAR or HISAT2, followed by read counting with featureCounts or HTSeq-count [12]

- Normalization: Advanced methods that correct for both sequencing depth and library composition, such as the median-of-ratios method (DESeq2) or TMM (edgeR) [12]

Different normalization methods address distinct aspects of technical variance. While Counts Per Million (CPM) only corrects for sequencing depth, and RPKM/FPKM correct for both depth and gene length, more advanced methods like those in DESeq2 and edgeR also account for composition biases where highly expressed genes in one sample can distort counts in others [12].

The evidence unequivocally demonstrates that biological replicates are not a luxury in RNA-Seq experimental design but a necessity for scientifically valid conclusions. Based on current research, the following recommendations emerge:

Prioritize Replication Over Sequencing Depth: For a fixed budget, allocating resources to include more biological replicates generally provides better statistical power than increasing sequencing depth beyond 20-30 million reads per sample [12] [14].

Establish Realistic Minimums: While the ideal number depends on biological variability, researchers should aim for a minimum of six biological replicates per condition for hypothesis-driven research, with increased numbers (10+) for heterogeneous populations or when detecting subtle expression changes [14].

Implement Robust Experimental Design: Carefully control for batch effects through randomization and blocking designs. Record all potential confounding variables for inclusion in statistical models [11].

Validate with Resampling: Use bootstrapping procedures to estimate the expected replicability of results from small cohorts and temper conclusions accordingly when replication is limited [14].

Transparently Report Limitations: When practical constraints prevent adequate replication, explicitly acknowledge these limitations in publications and avoid overstating conclusions.

Adequate biological replication remains the most effective safeguard against the replicability crisis in transcriptomics, ensuring that RNA-Seq data yields biologically meaningful insights rather than statistical artifacts.

In the context of RNA-seq research, a fundamental challenge lies in balancing finite resources between two critical parameters: sequencing depth and sample size. This technical guide explores how this balance directly impacts the statistical power to detect true biological signals amidst inherent sample variability. Drawing on recent empirical studies and statistical frameworks, we provide evidence-based recommendations for optimizing experimental designs in transcriptomics research, particularly for researchers and drug development professionals facing budget constraints. The findings emphasize that strategic allocation of resources significantly influences the reliability and reproducibility of differential expression analysis, a cornerstone of modern genomic science.

Next-generation sequencing technologies have revolutionized transcriptomics, but their effective implementation requires careful experimental design. The core challenge stems from the inverse relationship between sequencing depth (number of reads per sample) and sample size (number of biological replicates) under fixed budget constraints. As sample size increases, researchers can better characterize and account for biological variability between individuals—a crucial consideration for assessing sample variability in RNA-seq datasets. Conversely, as sequencing depth increases, the ability to detect low-abundance transcripts and accurately quantify expression improves. This trade-off creates a complex optimization problem that directly impacts the statistical power and false discovery rates in differential expression analysis [15].

The dilemma is further compounded by the unique characteristics of RNA-seq data. Unlike microarray technologies, RNA-seq produces discrete count data that typically follows a negative binomial distribution, requiring specialized statistical approaches for power analysis [16]. Furthermore, the genome-wide distribution of expression levels is markedly skewed, with most sequencing reads mapping to a small fraction of highly expressed genes, while the majority of genes exhibit low counts [15]. These technical and biological considerations make resource allocation between depth and sample size a critical determinant of experimental success.

Quantitative Framework: Statistical Power in RNA-Seq Experiments

Key Parameters Influencing Detection Power

The power to detect differentially expressed genes in RNA-seq experiments depends on several interconnected parameters:

- Effect Size: The magnitude of expression difference between conditions (typically measured as fold-change)

- Biological Variability: Natural variation in gene expression between biological replicates

- Sample Size (N): Number of biological replicates per condition

- Sequencing Depth (R): Number of reads per sample

- False Discovery Rate (FDR): The acceptable proportion of false positives among significant findings

Statistical power analysis for RNA-seq must account for the discrete nature of count data and the over-dispersion commonly observed in gene expression measurements [16]. The negative binomial distribution has become the standard model for RNA-seq data analysis, as it better captures the relationship between mean and variance than the Poisson distribution [16] [15].

The Impact of Sample Size on False Discovery Rates

Recent large-scale empirical studies in murine models provide compelling evidence for adequate sample sizes in RNA-seq experiments. A comprehensive analysis of N = 30 samples per condition revealed that experiments with N ≤ 4 exhibit unacceptably high false positive rates and fail to detect many genuinely differentially expressed genes [9].

Table 1: Sample Size Recommendations from Empirical Murine Studies

| Sample Size (N) | False Discovery Rate | Sensitivity | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| N ≤ 4 | >50% | <30% | Highly misleading results |

| N = 5 | ~40% | ~35% | Inadequate for reliable conclusions |

| N = 6-7 | <50% | >50% | Minimum threshold for acceptable FDR |

| N = 8-12 | ~20-30% | >70% | Optimal range for most studies |

| N > 12 | <20% | >80% | Diminishing returns observed |

This research demonstrated that for a 2-fold expression difference cutoff, a sample size of 6-7 mice per group is required to consistently decrease the false positive rate below 50% and increase detection sensitivity above 50%. Notably, more samples are always better for both metrics, with N = 8-12 performing significantly better in recapitulating results from the full N = 30 experiment [9].

The Role of Sequencing Depth in Detection Sensitivity

Sequencing depth directly influences the ability to detect expression changes, particularly for low-abundance transcripts. Deeper sequencing increases the probability of capturing molecules from rarely expressed genes, thereby improving the accuracy of their quantification. However, the relationship between depth and power follows a law of diminishing returns—initial increases in depth substantially improve detection power, but further increases provide progressively smaller gains [16] [17].

For most applications, sequencing depths between 20-30 million reads per sample provide sufficient coverage for the majority of protein-coding genes. Beyond this threshold, the marginal gain in power becomes relatively small compared to the benefit of adding more biological replicates [16]. However, specific applications such as detecting rare variants or studying low-abundance transcripts may require substantially higher depths [17].

Experimental Design Strategies for Optimal Power

Power Analysis Methodologies

Several statistical frameworks have been developed specifically for power analysis in RNA-seq experiments:

Table 2: Power Analysis Tools for RNA-Seq Experimental Design

| Tool/Approach | Methodology | Key Features | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNASeqDesign | Mixture model fitting | Simultaneous optimization of N and R; FDR control | Bulk RNA-seq with pilot data |

| scPower | Analytical framework | Optimizes for single-cell multi-sample designs | scRNA-seq experiments |

| POWSC | Simulation-based | Evaluates trade-offs between sample size and depth | Single-cell RNA-seq |

| Scotty | Web-based tool | User-friendly interface for power calculation | Bulk RNA-seq |

| SEQPower | Empirical and analytical | Handles complex rare variant association studies | Rare variant detection |

These tools incorporate the key parameters discussed previously and help researchers determine the optimal balance between sample size and sequencing depth for their specific research context and budget constraints [15] [18] [19].

Practical Guidelines for Resource Allocation

Based on comprehensive analyses of multiple RNA-seq datasets, the following strategic guidelines emerge for balancing sequencing depth and sample size:

Prioritize Sample Size for Differential Expression: For standard differential expression analyses, increasing sample size provides greater improvements in statistical power than increasing sequencing depth beyond 20 million reads [16]. This is particularly true for detecting small effect sizes or when biological variability is high.

Targeted Depth Increases for Specific Applications: Higher sequencing depths (>50 million reads) remain beneficial for specific applications including:

- Detection of rare transcripts or low-abundance isoforms

- Identification of low-frequency variants

- Studies focusing on genes with very low expression levels [17]

Consider Pseudobulk Approaches for Single-Cell Studies: For multi-sample single-cell RNA-seq experiments, the pseudobulk approach (summing counts across cells of the same type per individual) provides robust power for inter-individual comparisons. In these designs, shallow sequencing of more cells generally yields higher overall power than deep sequencing of fewer cells [18].

Account for Effect Size Expectations: The optimal design depends heavily on the expected effect sizes. Large expression differences (e.g., >2-fold) can be detected with smaller sample sizes, while detecting subtle changes (<1.5-fold) requires larger sample sizes regardless of sequencing depth [9].

Diagram 1: Resource allocation decision pathway for RNA-seq experimental design under fixed budget constraints, highlighting the key benefits associated with prioritizing either sequencing depth or sample size.

Advanced Considerations in Experimental Design

Batch Effects and Technical Variability

In large-scale RNA-seq studies, batch effects—systematic technical variations introduced during sample processing—can significantly impact results and complicate the depth vs. sample size balance. Batch effects arise from various sources including different reagent lots, personnel, processing times, and sequencing runs [20]. These effects can:

- Introduce noise that obscures biological signals

- Reduce statistical power for detecting true differences

- Lead to false conclusions when confounded with experimental conditions

To mitigate batch effects while maintaining optimal power:

- Randomize Sample Processing: Ensure samples from different experimental groups are distributed across processing batches

- Include Batch Controls: Use reference samples or spike-in controls across batches to monitor technical variability

- Account for Batches in Analysis: Include batch as a covariate in statistical models or apply batch correction algorithms [20] [21]

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Specific Considerations

Single-cell RNA-seq introduces additional dimensions to the depth vs. sample size optimization problem. In multi-sample scRNA-seq studies, researchers must balance:

- Number of individuals (biological replicates)

- Number of cells per individual

- Sequencing depth per cell

For cell type-specific differential expression analysis, the pseudobulk approach has emerged as a statistically robust method. This approach aggregates counts across cells of the same type within each individual, then applies bulk RNA-seq differential expression methods [18]. Power analysis for such experiments reveals that:

- Sequencing more cells at moderate depth generally provides better power than sequencing fewer cells deeply

- The optimal number of cells per individual depends on the frequency of the cell type of interest

- For rare cell types (<5% frequency), substantial cell numbers are needed to ensure adequate representation [18]

Cost-Benefit Optimization Framework

The RNASeqDesign framework formalizes the optimization problem as a two-dimensional search for the best combination of sample size (N) and sequencing depth (R) that maximizes genome-wide power within budget constraints [15]. This approach:

- Utilizes pilot data to estimate key parameters (effect size distributions, dispersion)

- Models the relationship between N, R, and statistical power

- Considers multiple testing correction through false discovery rate control

- Provides power curves for different budget scenarios

Diagram 2: Workflow for computational optimization of RNA-seq experimental design using pilot data and statistical power modeling to balance sample size and sequencing depth.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Experimental Design

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Distinguish true biological variants from technical artifacts | All RNA-seq applications, especially low-input and single-cell |

| Spike-in Controls (e.g., SIRVs) | Monitor assay performance, normalize data, quantify technical variability | Large-scale studies, cross-batch comparisons |

| Library Preparation Kits | Convert RNA to sequence-ready libraries with specific bias profiles | All RNA-seq applications |

| Batch Effect Correction Algorithms | Statistically remove technical variations while preserving biological signals | Multi-batch studies, meta-analyses |

| Power Analysis Software | Estimate statistical power and optimize design parameters | Experimental planning stage |

The optimal balance between sequencing depth and sample size in RNA-seq experiments is not a one-size-fits-all solution but depends on specific research objectives, biological context, and resource constraints. Empirical evidence strongly supports prioritizing sample size for most differential expression applications, with minimum recommendations of 6-8 biological replicates per group for adequate power and false discovery control. Sequencing depth beyond 20-30 million reads per sample provides diminishing returns for standard applications, though deeper sequencing remains valuable for detecting low-abundance transcripts and rare variants.

Future developments in statistical methods and experimental protocols will continue to refine these recommendations, but the fundamental principle remains: thoughtful experimental design that explicitly considers the trade-off between sequencing depth and sample size is essential for generating biologically meaningful and statistically robust results in transcriptomics research. By applying the frameworks and guidelines presented here, researchers can maximize the scientific return on their investment in RNA-seq studies while maintaining rigorous statistical standards.

In RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) research, quality control (QC) is a critical, multi-stage process that ensures the reliability of biological conclusions by identifying technical biases and artifacts within datasets. For researchers and drug development professionals assessing sample variability, QC is not merely a technical formality but a foundational step that safeguards against misleading interpretations [22]. The complexity of RNA-seq data, stemming from multi-layered procedures involving sample preparation, library construction, sequencing, and bioinformatics processing, introduces multiple potential sources of error. Effective QC practices are therefore indispensable for differentiating true biological signal from technical noise, ultimately ensuring the integrity of downstream analyses such as differential gene expression [22] [12].

This guide focuses on three powerful complementary approaches for interpreting QC metrics: FastQC for initial raw data assessment, MultiQC for aggregating results across multiple samples and tools, and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) as a robust indicator of systematic variability. Together, this toolkit provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for evaluating sample quality, identifying batch effects, and understanding the major sources of variation in their datasets, which is crucial for any subsequent biomarker discovery or therapeutic development pipeline.

The QC Toolbox: Functions and Workflow

A rigorous RNA-seq QC pipeline employs specialized tools at various stages of data processing. The sequential application of these tools allows researchers to monitor data quality from raw sequencing output to aligned reads, capturing different dimensions of data integrity.

Table 1: Essential Tools for the RNA-seq QC Pipeline

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Input | Key Output | Stage of Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastQC [23] | Provides initial quality assessment of raw sequence data. | FASTQ files | HTML report with quality graphs | Raw Data QC |

| Trimmomatic/Cutadapt [22] [12] | Removes low-quality bases and adapter sequences. | FASTQ files | "Cleaned" FASTQ files | Preprocessing |

| STAR/HISAT2 [12] | Aligns sequenced reads to a reference genome. | Trimmed FASTQ files | SAM/BAM files | Alignment |

| Qualimap [22] [24] | Provides RNA-seq-specific QC metrics post-alignment. | BAM files | Various metrics (e.g., coverage, bias) | Post-Alignment QC |

| MultiQC [24] [25] | Aggregates and visualizes QC outputs from multiple tools and samples. | Outputs from FastQC, STAR, etc. | Consolidated HTML report | Aggregate Reporting |

| PCA [26] [27] | Identifies major patterns and outliers in gene expression data. | Normalized count matrix | Scatter plot of samples in 2D space | Post-Normalization |

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these tools are integrated into a standard RNA-seq analysis pipeline, highlighting the critical QC checkpoints.

FastQC: Interpreting Raw Sequence Quality

FastQC serves as the first line of defense in RNA-seq QC, providing a preliminary assessment of data quality from the raw FASTQ files generated by the sequencer [23]. Its primary role is to identify any fundamental problems that occurred during sequencing, which could compromise all downstream analyses.

Key FastQC Modules and Their Interpretation

When analyzing a FastQC report, researchers should focus on several key modules to evaluate potential issues. It is crucial not to over-interpret warnings, as some are expected for RNA-seq data, but to use them as flags for deeper investigation [28].

Table 2: Critical FastQC Modules and Their Interpretation in RNA-seq

| Module | What It Measures | Ideal Result | Common RNA-seq Deviations & Causes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per Base Sequence Quality | Average base call quality (Phred score) across all reads at each position. | High quality (Q>30) across all bases, with minimal drop at the 3' end. | Steady quality drop at 3' end (signal decay/phasing) [28]. Sudden quality drops may indicate sequencer failure. |

| Per Base Sequence Content | Proportion of each nucleotide (A,T,C,G) at every position. | Balanced proportions (~25% each) across all bases after the first few. | Systematic bias in the first 10-12 bases due to random hexamer priming [28]. This is expected and typically does not require intervention. |

| Per Sequence GC Content | Distribution of GC content across all reads. | A roughly normal distribution centered on the organism's expected GC%. | Sharp peaks suggest over-represented sequences (e.g., contamination, highly expressed gene). Broad peaks may indicate contamination [28]. |

| Sequence Duplication Levels | The level of duplicate reads in the library. | Low duplication rate, with the curve falling steeply. | High duplication can indicate low library complexity from too little input RNA or PCR over-amplification [28]. |

| Overrepresented Sequences | Sequences that appear in more than 0.1% of all reads. | No overrepresented sequences, or a few explained by biology. | Common contaminants include adapter sequences, spike-ins, or ribosomal RNA (rRNA). Unexplained sequences should be BLASTed [28]. |

Experimental Protocol: Running FastQC

The following protocol outlines the standard methodology for executing FastQC analysis, a critical step for initial data assessment.

- Tool Installation: FastQC is a Java application. Download it from the Babraham Institute website and ensure a Java Runtime Environment is available [23].

- Input Data Preparation: Gather the raw FASTQ files from the sequencing facility. These can be compressed (.gz) or uncompressed.

- Command Line Execution: Run FastQC from the command line. For a single file:

fastqc sample_1.fastq.gzFor all FASTQ files in a directory:fastqc *.fastq.gz - Output Generation: FastQC produces an HTML report file (

sample_1_fastqc.html) and a ZIP file containing the raw data for each input FASTQ file. - Report Interpretation: Transfer the HTML file to a local computer and open it in a web browser. Systematically review each module as summarized in Table 2, paying close attention to "WARNING" and "FAIL" flags, and contextualizing them with known RNA-seq biases [28].

MultiQC: Aggregating and Comparing Metrics

While FastQC is powerful for inspecting individual samples, modern RNA-seq studies often involve dozens or hundreds of samples. Manually comparing individual reports is impractical and error-prone. MultiQC solves this problem by automatically finding results from many bioinformatics tools (including FastQC, STAR, Qualimap, Salmon, and over 150 others) and aggregating them into a single, interactive report [24] [25]. This enables researchers to quickly assess the consistency of their entire dataset and identify outlier samples.

Key Metrics in a MultiQC Report

A MultiQC report provides a "General Statistics" table that summarizes the most critical metrics from various tools, allowing for easy cross-sample comparison [24]. Key columns to configure and monitor include:

- M Seqs (from FastQC): The total number of raw reads (in millions). Large discrepancies between samples can introduce bias and need to be corrected during normalization.

- % Aligned (from STAR): The percentage of reads that uniquely map to the reference genome. A good quality sample typically has at least 75% uniquely mapped reads. Values dropping below 60% warrant investigation into potential contamination, RNA degradation, or reference genome issues [24].

- % Aligned (from Salmon): The percentage of reads mapping to the transcriptome. This is often lower than the genomic alignment rate and is critical for transcript-level quantification.

- % rRNA: The percentage of reads mapping to ribosomal RNA. High rRNA content (>5-10%) indicates inadequate rRNA depletion during library prep, wasting sequencing capacity on non-informative reads [22].

- % Dups: The percentage of duplicate reads. High levels can indicate low library complexity or over-amplification by PCR. Large differences in %Dups between samples can lead to GC bias [24].

- 5'-3' bias: A measure of coverage uniformity across transcripts. A value of 1 indicates perfect balance. Values approaching 0.5 or 2.0 indicate strong 3' or 5' bias, often resulting from RNA degradation or suboptimal library preparation for certain protocols [24].

- % GC: The average guanine-cytosine content. This should be consistent across samples from the same organism. Systematic differences can indicate contamination or technical artifacts.

Experimental Protocol: Running MultiQC

Integrating MultiQC at the end of a computational workflow standardizes the QC review process and is essential for collaborative projects.

- Tool Installation: Install MultiQC via pip:

pip install multiqcor conda:conda install multiqc[25]. - Data Collection: Run your RNA-seq pipeline, ensuring outputs from FastQC, aligners (e.g., STAR

.Log.final.outfiles), and quantifiers (e.g., Salmon directories) are saved in an organized directory structure. - Command Line Execution: Navigate to the directory containing all the pipeline outputs and run:

multiqc .This command will recursively search the current directory for files it recognizes and compile them into a report. - Advanced Execution with Specific Paths: For more control, specify the paths to the results:

- Output and Interpretation: MultiQC generates

multiqc_report.htmland a data directory. Open the HTML report in a browser. Use the "General Statistics" table to sort and filter samples. Click on any plot to explore interactive visualizations that help identify outliers and assess the overall consistency of the dataset [24].

PCA: A Multivariate Indicator of Variability

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a dimensionality reduction technique used to simplify complex datasets while preserving their most important structures [26] [27]. In the context of RNA-seq, PCA is applied to the normalized gene expression matrix to visualize the largest sources of variation between samples. It transforms the high-dimensional expression data (thousands of genes) into a new set of variables, the principal components (PCs), which are ordered by the amount of variance they explain [26]. The first principal component (PC1) captures the greatest variance in the data, PC2 the second greatest, and so on. By plotting samples along the axes of the first two or three PCs, researchers can visually assess:

- The overall similarity and clustering of biological replicates.

- The separation between experimental conditions (e.g., treated vs. control).

- The presence of outlier samples that do not cluster with their group.

- The influence of unwanted technical effects, such as batch, sequencing date, or library preparation batch, which often manifest as strong separations along a principal component [22].

The Mathematics of PCA in RNA-seq

The power of PCA lies in its ability to objectively identify the directions of maximum variance in a high-dimensional dataset. The process can be broken down into five key steps [26]:

- Standardization and Centering: The raw count matrix is normalized and transformed to correct for library size and variance stability (e.g., using a variance-stabilizing transformation in DESeq2). Each gene is then centered to have a mean of zero.

- Covariance Matrix Computation: PCA computes the covariance matrix of the transformed expression data. This matrix captures how the expression of every gene varies with every other gene across all samples.

- Eigendecomposition: The covariance matrix is decomposed into its eigenvectors and eigenvalues. The eigenvectors (principal components) define the new axes of maximum variance, while the eigenvalues quantify the amount of variance captured by each PC.

- Feature Selection: Researchers select the top k PCs that capture a sufficient amount of the total variance (e.g., 70-90%) for visualization and downstream analysis, effectively reducing dimensionality.

- Data Projection (Projection): The original expression data is projected onto the new PC axes to obtain the coordinates ("scores") for each sample in the new, lower-dimensional space. These scores are used to create the PCA plot.

The following diagram illustrates this computational process and its role in identifying sources of variability.

Experimental Protocol: Performing PCA on RNA-seq Data

PCA is typically performed within R or Python environments using standard bioinformatics packages. The following protocol uses R and the DESeq2 package as an example.

- Input Data Preparation: Begin with a raw count matrix, where rows represent genes and columns represent samples. Ensure that normalization and any necessary transformations for count data are applied.

- Data Normalization and Transformation: Use a specialized method like the median-of-ratios normalization in DESeq2 or the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) in edgeR to correct for library size and composition [12]. Following normalization, apply a variance-stabilizing transformation (VST) or a regularized-log transformation (rlog) to ensure that the variance is stable across the dynamic range of expression, a key assumption for PCA.

- Execution in R:

- Interpretation of Results: Examine the resulting PCA plot.

- Clustering: Check if biological replicates cluster tightly together.

- Separation: Assess if the separation between experimental groups (e.g., treated vs. control) is greater than the separation within groups.

- Outliers: Identify any samples that fall far outside the main cluster of their group.

- Batch Effects: If a known batch variable (e.g., sequencing date) correlates with the separation along PC1 or PC2, a batch effect is likely present and should be accounted for statistically.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogs key laboratory and computational reagents essential for generating and analyzing high-quality RNA-seq data.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for RNA-seq

| Item | Function/Description | Example Products/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolves high-quality, intact total RNA from cells or tissues. Essential for preventing degradation bias. | Qiagen RNeasy, TRIzol Reagent |

| rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA to enrich for mRNA and other informative RNA species. | Illumina Ribo-Zero, NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit |

| Library Prep Kit | Converts purified RNA into a sequencing-ready library by fragmenting, reverse transcribing, and adding adapters. | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA, NEBNext Ultra II |

| Sequencing Platform | High-throughput instrument that performs the massive parallel sequencing of the prepared libraries. | Illumina NovaSeq X, Oxford Nanopore PromethION |

| Reference Genome | A curated, annotated genomic sequence for the target organism used for read alignment and quantification. | ENSEMBL, GENCODE, UCSC Genome Browser |

| QC Analysis Software | Computational tools for assessing quality at each stage of the pipeline, as detailed in this guide. | FastQC, MultiQC, RSeQC, Qualimap [22] [23] |

| Alignment Software | Aligns (maps) the sequenced reads to the reference genome to determine their genomic origin. | STAR, HISAT2 [12] |

| Quantification Software | Counts the number of reads mapped to each gene or transcript to generate an expression matrix. | featureCounts, HTSeq, Salmon [12] |

| Statistical Analysis Environment | A programming environment and suite of packages for normalization, differential expression, and visualization. | R/Bioconductor (DESeq2, edgeR), Python (Scanpy) |

A comprehensive QC strategy integrating FastQC, MultiQC, and PCA is non-negotiable for robust RNA-seq analysis, particularly in the context of drug development and biomarker discovery where conclusions directly impact research validity. FastQC provides the foundational check on raw data integrity, MultiQC enables scalable, comparative quality assessment across large cohorts, and PCA serves as a powerful multivariate indicator of both biological and technical variability. By systematically implementing the protocols and interpretations outlined in this guide, researchers can confidently identify and mitigate sources of error, validate sample quality, and ensure that the biological signals driving their conclusions are both real and reliable.

Practical Strategies for Measuring and Controlling Variability

The determination of an appropriate sample size is a critical component in the design of robust and reliable RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) experiments. Insufficient sample sizes lead to an excess of both false positives (type I errors) and false negatives (type II errors), undermining the validity of scientific conclusions [6] [9]. Conversely, excessively large samples waste precious resources and may raise ethical concerns in studies involving animal models or human subjects [6] [9]. Traditional power calculations often rely on simplistic assumptions that do not account for the complex nature of RNA-Seq data, which exhibits wide distributions of gene expression levels and between-sample variations [29]. This whitepaper explores the framework of empirical power calculations, which leverage real data distributions from previous, similar experiments to provide more accurate and reliable sample size estimates, thereby addressing the inherent variability in RNA-seq datasets.

Theoretical Foundations of Power Analysis

Statistical power is the probability that a test will correctly reject a false null hypothesis (i.e., detect a true effect). Power analysis for sample size determination balances several interrelated factors [6]:

- Type I Error (α): The probability of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis (false positive). The significance threshold (α) is typically set at 0.05.

- Type II Error (β): The probability of failing to reject a false null hypothesis (false negative). Power is calculated as 1 - β, with 0.8 (80%) commonly considered adequate.

- Effect Size: The magnitude of the biological effect a researcher aims to detect, such as a fold change in gene expression.

- Variability: The natural biological and technical variation present in the data, often represented as a dispersion parameter in RNA-Seq data models.

The fundamental relationship between these factors means that for a given effect size and variability, a higher power and a more stringent significance level will require a larger sample size [6].

RNA-Seq data are characterized as count-based and are optimally modeled using a negative binomial (NB) distribution, which accounts for both technical replication and the natural biological variation between replicates—a phenomenon known as overdispersion [30] [31]. The negative binomial model is defined by a mean expression value (μ) and a dispersion parameter (ϕ), with the variance given by Var = μ + μ²ϕ [31]. This model forms the statistical backbone of widely used differential expression tools such as edgeR and DESeq2, and consequently, of the power analysis methods derived from them [30] [31].

The Critical Shift from Single-Parameter to Empirical Power Calculations

Limitations of Single-Parameter Approaches

Initial methods for RNA-Seq power calculation often relied on single, conservatively chosen values for key parameters like average read count and dispersion to represent all genes in an experiment [29]. For instance, a method proposed by Hart et al. provides a basic formula for the number of samples per group (n), incorporating the chosen significance level (α), power (1-β), fold change (Δ), per-gene read depth (μ), and the coefficient of variation (σ) [30]:

$$n = \frac{(z{\alpha/2} + z{\beta})^2 \cdot (\sigma^2 + \sigma^2/\mu)}{(\log \Delta)^2}$$

While this provides a useful starting point, this approach is inherently flawed because it oversimplifies the true structure of RNA-Seq data. In reality, gene expression levels and their associated dispersions are not single values but follow wide, continuous distributions across several orders of magnitude [29]. Using a single "minimal" read count and "maximal" dispersion to represent an entire dataset forces an overly conservative and often impractical sample size estimate, potentially inflating the required number of replicates by several-fold [29].

The Empirical Data-Based Approach

Empirical power calculations overcome these limitations by utilizing the actual distributions of read counts and dispersions observed in real-world datasets that are similar to the planned experiment [29]. This methodology involves:

- Leveraging a Reference Dataset: Using a large, high-quality RNA-Seq dataset from a comparable biological context (e.g., from a repository like The Cancer Genome Atlas - TCGA) to estimate the empirical distributions of gene expression and dispersion [29].

- Modeling the Mean-Dispersion Relationship: Acknowledging and modeling the fundamental dependence between a gene's expression level and its dispersion, which typically follows a trend such as ϕ_{tr}(μ) = a₁/μ + a₀ [31].

- Aggregating Power Across Genes: Performing power or sample size calculations for a large number of individual genes based on their specific empirical parameters (mean and dispersion) and then summarizing the overall power for the experiment [29].

This strategy provides a more realistic and often less conservative estimate, ensuring the sample size is adequate for the specific gene expression patterns expected in the research context. Table 1 summarizes the key differences between these two methodological approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Parameter and Empirical Power Calculation Methods

| Feature | Single-Parameter Method | Empirical Data-Based Method |

|---|---|---|

| Key Parameters | Single, conservative values for read count & dispersion | Distributions of read counts & dispersions from real data |

| Data Model | Represents all genes with one low read count & one high dispersion | Accounts for the unique read count/dispersion for each gene |

| Mean-Dispersion Relationship | Often ignored | Explicitly modeled and incorporated |

| Sample Size Output | A single, conservative number for the whole experiment | A distribution of power across genes; overall sample size is a summary |

| Flexibility | Limited; suited for entire transcriptome with uniform parameters | High; can be applied to a specific gene set or pathway |

| Practical Output | Often overestimates required sample size | Provides a more realistic and context-aware estimate |

Practical Implementation and Protocols

Available Software Tools

Several software tools have been developed to implement empirical power analysis for RNA-Seq experiments, making these methods accessible to non-statisticians.

- RnaSeqSampleSize: This R/Bioconductor package is a leading tool that incorporates the empirical approach. It uses real data distributions to estimate sample size and power, controls for the False Discovery Rate (FDR) for multiple testing, and offers unique features like power estimation for specific gene lists or KEGG pathways [29]. A user-friendly web interface is also available.

- RNASeqPower: An earlier Bioconductor package that provides power analysis based on the score test for single-gene differential expression [29].

- PROPER: A simulation-based Bioconductor package that offers prospective power assessment for RNA-Seq experiments, comparing multiple analysis methods [29] [31].

A Generalized Workflow for Empirical Power Calculation

The following workflow, adaptable to tools like RnaSeqSampleSize, outlines the steps for conducting an empirical power analysis.

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for implementing empirical power calculation for an RNA-Seq experiment.

Protocol for Sample Size Estimation Using Real Data

This protocol details the steps for using the empirical approach with a tool like RnaSeqSampleSize [29].

- Define Input Parameters: Specify the desired statistical power (typically 0.8 or 80%), significance level (α = 0.05), False Discovery Rate (FDR, e.g., 0.05), and the minimum fold change of biological interest (e.g., 1.5 or 2.0).

- Obtain and Process a Reference Dataset: Identify and download a relevant RNA-Seq dataset (e.g., from TCGA, GEO). The dataset should be processed to obtain a count matrix (genes x samples) and normalized.

- Execute the Power Calculation:

- In R, load the

RnaSeqSampleSizepackage and your reference data. - Use the appropriate function (e.g.,

estPowerorsampleSize) that allows for the input of the real data matrix alongside the parameters from Step 1. - The software will internally calculate the distributions of read counts and dispersions, perform power calculations for many genes, and return a summary of the required sample size or the achieved power for a given sample size.

- In R, load the

- Interpret the Output: The output will provide the estimated number of biological replicates per group needed to detect the specified fold change with the desired power, given the variability observed in the reference data.

Protocol for Pathway-Focused Sample Size Estimation

Researchers often focus on specific pathways. The empirical method can be tailored for this scenario [29]:

- Define the Gene Set: Provide a list of gene symbols or a KEGG pathway ID relevant to your research question.

- Run a Targeted Analysis: Using