Batch Effect Correction in Validation Studies: A Practical Guide for Robust and Reproducible Biomarker Discovery

Batch effects, the technical variations introduced during data generation, pose a significant threat to the validity and reproducibility of biomedical validation studies.

Batch Effect Correction in Validation Studies: A Practical Guide for Robust and Reproducible Biomarker Discovery

Abstract

Batch effects, the technical variations introduced during data generation, pose a significant threat to the validity and reproducibility of biomedical validation studies. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate the challenges of batch effect correction. We cover foundational concepts, from the profound impact of batch effects on clinical conclusions to their sources in study design and sample preparation. The guide then delves into methodological strategies, comparing popular algorithms and their optimal application points in data workflows. A critical troubleshooting section addresses pervasive issues like overcorrection, under-correction, and the perils of confounded study designs. Finally, we present a rigorous validation framework, introducing novel metrics and sensitivity analyses to ensure that batch correction enhances, rather than obscures, true biological signals. By integrating the latest benchmarking research and consortium efforts, this article aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to implement robust batch correction protocols, thereby accelerating reliable translational discoveries.

Understanding Batch Effects: Why Technical Noise Threatens Validation Study Integrity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a batch effect?

A batch effect is a form of non-biological, technical variation that is systematically introduced into experimental data when samples are processed and measured in different groups or "batches" [1]. These effects are unrelated to the biological variation under investigation and occur due to differences in technical conditions. Batch effects are common in various types of high-throughput sequencing experiments, including those using microarrays, mass spectrometers, and single-cell RNA-sequencing [1].

2. What are the common causes of batch effects?

Batch effects can arise from numerous sources at virtually every stage of a high-throughput study [1] [2]. Key causes include:

- Laboratory conditions: Variations in ambient lab environments.

- Reagent lots: Using different batches or lots of reagents [1].

- Personnel differences: Variations in technique between different technicians [1].

- Equipment: Using different instruments to conduct the experiment [1].

- Experimental timing: Processing samples at different times of day or on different days [1] [3].

- Protocol variations: Differences in sample preparation, storage conditions, or analysis pipelines [2].

3. Why are batch effects problematic in research?

Batch effects can have a profound negative impact on research outcomes [2] [3].

- Incorrect Conclusions: They can lead to false-positive or false-negative findings, skewing analysis and resulting in misleading conclusions. In one clinical trial, a change in RNA-extraction solution caused a shift in gene-based risk calculations, leading to incorrect treatment classifications for 162 patients [2].

- Irreproducibility: Batch effects are a paramount factor contributing to the "reproducibility crisis" in science, potentially resulting in retracted articles and economic losses [2] [3].

- Reduced Statistical Power: They introduce noise that can obscure true biological signals, reducing the power to detect real effects [2].

4. How can I detect batch effects in my data?

Both visualization and statistical methods can be used to detect batch effects.

- Visualization: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots are commonly used. If samples cluster strongly by batch rather than by the biological group of interest, it suggests a batch effect [4].

- Statistical Tests: Methods like guided PCA (gPCA) provide a test statistic (δ) to quantify the proportion of variance due to batch and test for its significance, which is especially useful when the batch effect is not the largest source of variation [4].

5. What should I do if my biological variable of interest is completely confounded with batch?

This is a challenging scenario where all samples from one biological group are processed in one batch, and all samples from another group in a separate batch. In such cases, it is nearly impossible to distinguish true biological differences from technical batch variations [3] [5]. The most effective strategy is prevention through careful experimental design to avoid this confounding. If confronted with confounded data, one of the most robust correction methods is the ratio-based approach, which scales the feature values of study samples relative to those of a common reference material processed in every batch [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Batch Effects in Your Dataset

Follow this workflow to systematically identify potential batch effects.

Guide 2: Choosing a Batch Effect Correction Method

The choice of correction algorithm depends on your data type and experimental design, particularly the level of confounding between your biological groups and batches. The following table summarizes the performance of various methods under balanced and confounded scenarios, based on a large-scale multiomics study [3].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Batch Effect Correction Algorithms (BECAs)

| Correction Method | Principle | Best For | Performance in Balanced Scenarios | Performance in Confounded Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio-Based (e.g., Ratio-G) | Scales feature values relative to a common reference sample processed in all batches [3]. | Multiomics studies, strongly confounded designs [3]. | Effective [3] | Superior performance; remains effective when other methods fail [3]. |

| Harmony | Uses PCA and a clustering approach to integrate datasets [6] [3]. | Single-cell RNA-seq data, balanced or mildly confounded designs [3]. | Good [3] | Performance decreases as confounding increases [3]. |

| ComBat/ComBat-seq | Empirical Bayes framework to adjust for batch effects [1] [7]. | Bulk RNA-seq and microarray data, balanced designs [3] [8]. | Good [3] | Can introduce bias and over-correct in confounded scenarios [3] [8]. |

| Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN) | Identifies mutual nearest neighbors across batches to correct the data [1] [6]. | Single-cell RNA-seq data [1]. | Good | Not recommended for strongly confounded data [3]. |

| Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA) | Estimates and adjusts for unmodeled sources of variation, including unknown batch effects [1]. | Scenarios with unknown or unrecorded batch factors [1]. | Good | Performance is limited in strongly confounded scenarios [3]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Batch Effect Management

| Item | Function in Batch Effect Control |

|---|---|

| Common Reference Materials (CRMs) | A commercially available or internally standardized sample (e.g., purified DNA, RNA, protein, or a synthetic standard) that is processed in every experimental batch. It serves as an anchor to correct for technical variation [3]. |

| Standardized Reagent Lots | Purchasing a single, large lot of critical reagents (e.g., enzymes, buffers, kits) for an entire study to minimize variation introduced by different manufacturing batches [1] [6]. |

| Sample Multiplexing Kits | Kits that allow pooling of multiple samples with unique barcodes into a single sequencing library. This ensures that library-to-library variation is spread across biological groups rather than being confounded with them [6]. |

Table of Contents

- FAQ: What are batch effects and why are they a problem?

- FAQ: How can I detect batch effects in my dataset?

- FAQ: What are the main methods for batch effect correction?

- FAQ: How do I know if I have over-corrected my data?

- Troubleshooting Guide: Solving Common Batch Effect Challenges

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

FAQ: What are batch effects and why are they a problem?

Answer: Batch effects are systematic technical variations in data that are introduced by how an experiment is conducted, rather than by the biological conditions being studied [9]. Think of them as an "experimental signature" that can obscure the true biological signal you are trying to measure.

These effects can originate from almost any step in your workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Different reagent lots, personnel, or protocols [6] [10].

- Instrumentation: Different sequencing runs, machines, or labs [10] [11].

- Time: Experiments conducted on different days, weeks, or months [10].

The stakes for not addressing batch effects are high. They can:

- Generate False Discoveries: Technical variation can be mistaken for biological variation, leading you to identify genes or proteins that are not truly associated with your condition of interest [9] [12].

- Mask True Signals: Real biological differences can be hidden by technical noise, causing you to miss important biomarkers [13].

- Cause Irreproducibility: Findings from one batch may not hold in another, leading to retracted papers and invalidated research [11]. In one documented case, a change in RNA-extraction solution led to incorrect risk classifications for 162 cancer patients, nearly causing incorrect treatment regimens [11].

FAQ: How can I detect batch effects in my dataset?

Answer: Detecting batch effects involves both visualization and quantitative metrics. A combination of the following methods is recommended.

1. Visualization Techniques

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Perform PCA and color the data points by batch. If batches form distinct clusters, especially along the first principal component (PC1), it indicates strong batch effects [14] [12].

- t-SNE/UMAP Plots: Visualize your data using t-SNE or UMAP. If cells or samples cluster by their batch instead of by their biological group (e.g., cell type or disease state), batch effects are present [14] [15].

- Clustering and Heatmaps: Construct a correlation heatmap or dendrogram. If samples group primarily by batch rather than biological condition, it signals a batch effect [12].

2. Quantitative Metrics For a less biased assessment, you can use these metrics, where values closer to 1 generally indicate better integration [14].

Table: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Batch Effects

| Metric Name | What It Measures |

|---|---|

| Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) | The similarity between two clusterings (e.g., by batch vs. by cell type). |

| Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) | The mutual dependence between the batch and cluster assignments. |

| k-Batch Effect Test (kBET) | Tests if batches are well-mixed in a local neighborhood. |

The following workflow outlines the process for identifying batch effects in your data:

FAQ: What are the main methods for batch effect correction?

Answer: Batch effect correction strategies fall into two main categories: those that transform the data and those that model the batch during statistical analysis. The choice depends on your data type and downstream goals.

1. Data Transformation Methods These algorithms actively remove batch effects to create a "corrected" dataset, often used for visualization and clustering.

Table: Common Batch Effect Correction Algorithms (BECAs)

| Method | Primary Use Case | Key Principle | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| ComBat / ComBat-seq [12] [3] | Bulk RNA-seq (ComBat-seq for counts) | Empirical Bayes framework to shrink batch-specific mean and variance. | Assumes batches affect many features similarly. |

| Harmony [6] [14] | scRNA-seq, Multi-sample integration | Iterative clustering in PCA space to maximize diversity and remove batch effects. | Known for fast runtime and good performance [15]. |

| Seurat CCA [6] [14] | scRNA-seq | Uses Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) and Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNNs) as "anchors" to align datasets. | |

| LIGER [14] | scRNA-seq | Integrative Non-negative Matrix Factorization (iNMF) to factorize datasets into shared and batch-specific factors. | |

| Ratio-Based Scaling [3] | Multi-omics | Scales feature values of study samples relative to a concurrently profiled reference material. | Highly effective in confounded designs [3]. |

2. Statistical Modeling Approaches

Instead of altering the data, this approach accounts for batch during analysis. In differential expression tools like DESeq2, edgeR, or limma, you can include batch as a covariate in your statistical model (e.g., ~ batch + condition) [12]. This is often the statistically safest approach as it does not alter the raw data.

FAQ: How do I know if I have over-corrected my data?

Answer: Overcorrection occurs when a batch effect correction method removes biological variation along with technical noise. Key signs include [14] [15]:

- Loss of Biological Separation: Distinct cell types or experimental conditions are merged together in your PCA or UMAP plots after correction.

- Poor Marker Genes: A significant portion of your cluster-specific markers are housekeeping genes (e.g., ribosomal genes) that are widely expressed, rather than canonical cell-type-specific genes.

- Missing Expected Signals: The absence of differential expression in pathways or genes that are known to be associated with your biological condition.

- Complete Overlap of Distinct Samples: Samples from very different biological origins become perfectly mixed, suggesting that all meaningful variation has been removed.

The diagram below illustrates the ideal outcome for batch effect correction and the warning signs of overcorrection:

Troubleshooting Guide: Solving Common Batch Effect Challenges

| Challenge | Symptoms | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Confounded Design [12] [16] | Batch and biological condition are perfectly correlated (e.g., all controls in one batch, all treated in another). Correction removes your biological signal. | This is the most challenging scenario. Prevention via experimental design is key. If unavoidable, ratio-based scaling using a reference material profiled in all batches can be effective [3]. |

| Overly Aggressive Correction [14] [15] | Loss of separation between known cell types; missing expected markers. | Try a less aggressive method (e.g., switch from a strong to a milder algorithm). Use quantitative metrics to compare methods and avoid the one that gives "perfect" mixing if biology is lost. |

| Imbalanced Samples [15] | Cell types or conditions are not represented equally across batches, confusing correction algorithms. | Choose integration methods benchmarked to handle imbalance (e.g., according to benchmarks, scANVI and Harmony can be good choices) [15]. Report the imbalance in your methods. |

| Unknown Batch Effects [9] [12] | Strong clustering in PCA that doesn't align with any known variable. | Use algorithms like Surrogate Variable Analysis (SVA) or Remove Unwanted Variation (RUV) that can infer hidden batch factors from the data itself [9] [12]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Strategic use of reference reagents during experimental design is one of the most powerful ways to combat batch effects.

Table: Essential Reagents for Batch Effect Management

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Batch Effect Control |

|---|---|

| Reference Materials [3] | Commercially available or in-house standardized samples (e.g., certified cell lines, purified nucleic acids) that are processed in every experimental batch. They serve as an internal anchor to quantify and correct for technical variation. |

| Standardized Reagent Lots | For a large study, purchasing a single, large lot of key reagents (e.g., enzymes, buffers, kits) to be used for all samples minimizes a major source of technical variation [6]. |

| Multiplexing Kits | Kits that allow samples from different conditions to be labeled (e.g., with barcodes) and pooled together for processing in a single reaction. This effectively eliminates batch effects for the pooled samples, as they are all exposed to the same technical environment [6] [15]. |

In high-throughput omics studies, batch effects are technical variations introduced during experimental processes that are unrelated to the biological factors of interest [2]. These non-biological variations can profoundly impact data quality, leading to misleading outcomes, reduced statistical power, or irreproducible results if not properly addressed [2] [17]. In clinical settings, severe consequences have occurred, including incorrect patient classification and unnecessary chemotherapy regimens due to batch effects from changes in RNA-extraction solutions [2]. As multiomics profiling becomes increasingly common in biomedical research and drug development, tackling batch effects has become crucial for ensuring data reliability and reproducibility [2]. This guide addresses common sources of batch effects in validation studies and provides practical solutions for their identification and correction.

FAQ: Understanding Batch Effects

Q1: What exactly are batch effects and why are they problematic in validation studies?

Batch effects are systematic technical variations that occur when samples are processed in different batches, under different conditions, or at different times [2] [14]. They represent consistent fluctuations in measurements stemming from technical rather than biological differences [14]. In validation studies, batch effects are problematic because they can:

- Skew analytical results and introduce large numbers of false-positive or false-negative findings [17]

- Mask true biological signals, reducing statistical power to detect real differences [2]

- Lead to incorrect conclusions when batch effects correlate with biological outcomes of interest [2]

- Contribute to the reproducibility crisis in scientific research, resulting in retracted articles and invalidated findings [2]

Q2: How do batch effect challenges differ between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq studies?

While both technologies face batch effect issues, the challenges differ significantly:

| Aspect | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-cell RNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Variation | Lower technical variations [2] | Higher technical variations, lower RNA input, higher dropout rates [2] |

| Data Structure | Less sparse data [14] | Extreme sparsity (~80% zero values) [14] |

| Correction Methods | Standard statistical methods (ComBat, limma) often sufficient [14] [18] | Often require specialized methods (Harmony, fastMNN, Scanorama) [14] [18] |

| Complexity | Less complex batch effects [2] | More complex batch effects due to cell-to-cell variation [2] |

Q3: Can batch correction methods accidentally remove biological signals of interest?

Yes, overcorrection is a significant risk when applying batch effect correction algorithms [2] [14]. Signs of overcorrection include:

- Cluster-specific markers comprising genes with widespread high expression across various cell types (e.g., ribosomal genes) [14]

- Substantial overlap among markers specific to different clusters [14]

- Absence of expected cluster-specific markers that are known to be present in the dataset [14]

- Scarcity of differential expression hits associated with pathways expected based on sample composition [14]

To minimize this risk, always validate correction results using both visualization techniques and quantitative metrics [14] [18].

Source 1: Reagent and Supply Variations

Problem: Different lots of reagents, enzymes, or kits introduce technical variations. For example, a study published in Nature Methods had to be retracted when the sensitivity of a fluorescent serotonin biosensor was found to be highly dependent on the batch of fetal bovine serum (FBS) [2].

Detection Methods:

- PCA visualization: Samples cluster by reagent lot rather than biological group [14] [18]

- Quality control metrics: Signal intensity variations correlated with reagent lot changes

Solutions:

- Standardize reagent sources and lot numbers throughout a study when possible [18]

- Archive sufficient quantities of critical reagents for longer-term studies [18]

- Include reference materials in each batch to enable ratio-based normalization [17]

- Document all reagent lots and catalog numbers meticulously for potential covariate adjustment [19]

Source 2: Personnel Differences

Problem: Variations in technique, sample handling, or timing between different technicians or operators.

Detection Methods:

- Process monitoring: Correlate technical measurements with operator identity

- Sample tracking: Document handling times and specific protocols used by each technician

Solutions:

- Implement standardized protocols with detailed instructions [19]

- Cross-train all personnel and conduct regular technique alignment sessions

- Randomize sample assignment to operators to avoid confounding

- Blind technicians to experimental groups when possible

Source 3: Sequencing Runs and Platform Types

Problem: Technical variations between different sequencing runs, instruments, or platform types.

Detection Methods:

- UMAP/t-SNE visualization: Cells or samples cluster by sequencing run rather than biological identity [14] [18]

- Quantitative metrics: kBET, ARI, or LISI metrics show strong batch separation [14] [18]

Solutions:

- Balance biological groups across sequencing runs whenever possible [18]

- Include technical replicates across different runs to assess variability [18]

- Use reference materials in each sequencing run for cross-batch normalization [17]

- Apply appropriate batch correction methods such as Harmony, ComBat, or ratio-based scaling [14] [18] [17]

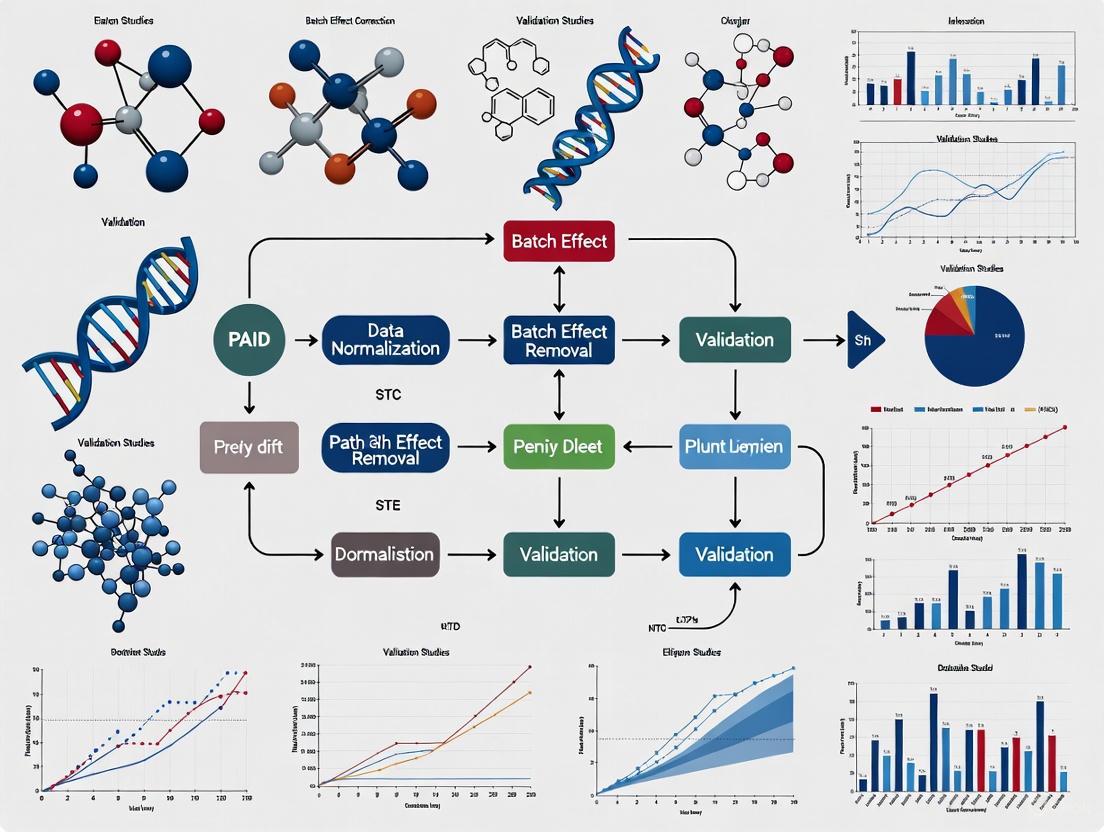

Batch Effect Introduction Pathway

Experimental Protocols for Batch Effect Assessment

Protocol 1: Detecting Batch Effects in Transcriptomics Data

Purpose: Identify the presence and magnitude of batch effects in transcriptomic datasets.

Materials Needed:

- Normalized expression matrix (counts or TPM)

- Metadata table including batch and biological group information

- R or Python environment with appropriate packages (Seurat, scanny, harmony)

Methodology:

- Perform dimensionality reduction using PCA on the normalized expression data [14]

- Visualize the first two principal components coloring points by batch and biological condition [14]

- Examine clustering patterns - separation by batch indicates batch effects [14]

- Apply quantitative metrics such as:

Interpretation: Strong batch effects are indicated when samples cluster primarily by batch rather than biological group in PCA/UMAP plots, and when quantitative metrics show significant batch separation [14] [18].

Protocol 2: Implementing Reference-Based Ratio Correction

Purpose: Correct batch effects using reference materials profiled concurrently with study samples.

Materials Needed:

- Study samples with absolute feature measurements

- Reference material(s) profiled in each batch

- Computing environment for data transformation

Methodology:

- Profile one or more reference materials concurrently with study samples in each batch [17]

- Calculate ratio values for each feature in each study sample relative to the reference material:

Ratio = Feature_study / Feature_reference[17] - Use resulting ratio values for downstream analysis instead of absolute measurements [17]

- Validate correction effectiveness using visualization and quantitative metrics as in Protocol 1

Interpretation: Effective correction is achieved when samples cluster by biological group rather than batch, and quantitative metrics show improved batch mixing while preserving biological signals [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in Batch Effect Management |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Quartet Project reference materials [17] | Provides benchmark for cross-batch normalization using ratio-based methods |

| Quality Control Samples | Pooled QC samples [18] | Monitors technical performance across batches and platforms |

| Resource Identification | Antibody Registry, Addgene [19] | Provides unique identifiers for reagents to ensure reproducibility |

| Internal Standards | Spike-in RNAs, isotopically labeled compounds | Enables normalization for specific assay types |

| Protocol Repositories | Nature Protocols, JoVE, Bio-protocol [19] | Provides detailed methodologies to maintain consistency across laboratories |

Batch Effect Correction Decision Framework

Key Takeaways for Effective Batch Effect Management

Successful management of batch effects in validation studies requires a comprehensive approach that begins with proactive experimental design and continues through to appropriate computational correction. The most effective strategy involves incorporating reference materials directly into study designs when possible, as the ratio-based scaling method has demonstrated superior performance in challenging confounded scenarios where biological variables align completely with batch variables [17]. Additionally, validating correction effectiveness using both visualization techniques and multiple quantitative metrics ensures that technical variations are reduced without sacrificing biological signals of interest [14] [18]. By systematically addressing the common sources of batch effects described in this guide - reagents, personnel, sequencing runs, and platform types - researchers can significantly enhance the reliability, reproducibility, and clinical relevance of their validation studies.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This guide addresses common experimental design challenges in batch effect correction for validation studies, helping researchers ensure data robustness and reliability.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: My multi-batch proteomics data shows strong biological separation after correction, but I suspect over-correction. How can I verify?

- Problem: Batch-effect correction algorithms can be too aggressive, removing biological signal along with technical noise (a phenomenon known as over-correction).

- Solution:

- Use Positive Controls: Leverage known true positive biological variations, such as those from reference materials (e.g., Quartet project materials) [20].

- Benchmark with Simulated Data: Introduce a simulated dataset with a built-in truth of known differential expressions to calculate the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and assess false discoveries [20].

- Validate with External Data: Confirm findings using a separate, well-controlled validation cohort or external dataset.

FAQ 2: In a long-term clinical proteomics study, my batch effects are completely confounded with a patient treatment group. What is the most robust correction strategy?

- Problem: When a specific batch contains only samples from one treatment group, it is impossible to statistically disentangle the batch effect from the biological effect using standard correction methods.

- Solution:

- Apply Protein-Level Correction: Benchmarking studies indicate that performing batch-effect correction at the protein level is the most robust strategy for confounded scenarios, as it is less prone to introducing errors compared to precursor or peptide-level correction [20].

- Employ Ratio-Based Methods: Use a ratio-based BECA (Batch Effect Correction Algorithm) with concurrently profiled universal reference samples. This method has demonstrated superior performance in scenarios where batch effects are confounded with biological groups [20].

- Acknowledge Limitations: Be transparent that causal inference is severely limited in fully confounded designs; results should be considered hypothesis-generating and require independent validation.

FAQ 3: Despite randomization, a confounding variable (e.g., sample storage time) is unevenly distributed between my experimental and control groups. How can I salvage the experiment?

- Problem: A lurking variable was not controlled during randomization, potentially biasing the results.

- Solution:

- Measure the Confounder: Record the data for the confounding variable (storage time) for all samples.

- Use Statistical Control: In your final analysis, include the confounding variable as a covariate in a statistical model (e.g., ANCOVA, linear regression) [21]. This statistically adjusts for its effect, allowing you to isolate the impact of your primary experimental variable.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Batch-Effect Correction Strategies in MS-Based Proteomics

This protocol is designed to systematically evaluate the optimal stage for batch-effect correction [20].

- 1. Experimental Design:

- Scenarios: Design both Balanced (sample groups evenly distributed across batches) and Confounded (sample groups unevenly distributed, tied to batch) scenarios [20].

- Datasets: Use real-world multi-batch data (e.g., from Quartet reference materials) and a simulated dataset with a built-in truth for known positive and negative results [20].

- 2. Data Level Correction:

Apply a chosen set of BECAs at three different data levels:

- Precursor-Level: Correct raw feature intensities.

- Peptide-Level: Correct aggregated peptide intensities.

- Protein-Level: Correct after protein quantification (Most robust strategy) [20].

- 3. Protein Quantification: Generate protein-quantity matrices using different quantification methods (e.g., MaxLFQ, TopPep3, iBAQ) [20].

- 4. Performance Assessment:

- Feature-Based Metrics:

- Calculate the Coefficient of Variation (CV) within technical replicates across batches.

- For simulated data, compute the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and Pearson correlation to evaluate the identification of truly differentially expressed proteins.

- Sample-Based Metrics:

- Calculate the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) from PCA to assess group separation.

- Perform Principal Variance Component Analysis (PVCA) to quantify the contribution of biological vs. batch factors to the total variance.

- Feature-Based Metrics:

Protocol 2: Implementing a Balanced Design to Avoid Confounding

This protocol outlines steps to prevent confounding during the experimental design phase.

- 1. Identify Potential Confounders: Before the experiment, brainstorm factors that could influence your results (e.g., instrument type, operator, sample preparation date, patient age, disease severity) [22] [21].

- 2. Blocking: Group experimental units (samples) into homogenous blocks based on a known confounding factor (e.g., by clinic site or processing day). Within each block, randomly assign samples to all experimental groups [22] [21].

- 3. Randomization: After blocking, randomly assign treatments or conditions to samples within those blocks. This ensures that unknown lurking variables are also likely to be evenly distributed across groups [22] [21].

- 4. Control Groups: Always include a concurrent control group that experiences the same technical procedures as the experimental group, differing only in the variable of interest [22].

Structured Data Comparison

Table 1: Performance of Batch-Effect Correction Levels in Confounded Scenarios

This table summarizes the relative performance of applying correction at different data levels, based on benchmarking studies [20].

| Data Level for Correction | Robustness in Confounded Design | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor-Level | Low | Corrects at the most granular, raw-data level. | High risk of propagating errors during protein quantification; less robust. |

| Peptide-Level | Medium | Addresses variation before protein inference. | May not fully account for protein-level aggregation effects. |

| Protein-Level | High (Recommended) | Most robust; corrects on the final data used for analysis. | Requires complete protein quantification before application. |

Table 2: Balanced vs. Confounded Experimental Scenarios

This table contrasts the features and implications of the two fundamental design scenarios.

| Feature | Balanced Scenario | Confounded Scenario |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Sample groups are evenly distributed across all batches and technical factors [20]. | A technical factor (e.g., Batch) is unevenly distributed across sample groups, making their effects inseparable [20] [22]. |

| Impact on Analysis | Allows for statistical disentanglement of batch and biological effects. | Makes it impossible to determine if differences are due to biology or batch [22]. |

| Risk of False Conclusions | Lower | Very High |

| Recommended BECA | A wider range of BECAs can be effective (e.g., Combat, Harmony). | Ratio-based methods with reference standards are most robust [20]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Batch-Effect Monitoring and Correction

| Item | Function in Validation Studies |

|---|---|

| Universal Reference Materials (e.g., Quartet) | Provides a stable, standardized benchmark across batches and labs to monitor technical performance and enable ratio-based correction [20]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Pooled samples injected repeatedly throughout the batch run to monitor signal drift and evaluate the precision of batch-effect correction. |

| Blocking Variables | A known factor (e.g., processing day) used to structure the experiment into homogenous groups to control for its confounding effect [22]. |

| Batch-Effect Correction Algorithms (BECAs) | Software tools (e.g., Combat, Ratio, RUV-III-C) designed to statistically remove unwanted technical variation from data matrices [20]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

FAQs: Batch Effects and Research Integrity

Q1: How can batch effects in lab data lead to real-world consequences in medicine?

Batch effects can distort scientific findings, leading to false targets and missed biomarkers in drug development [13]. When these distorted findings are incorporated into the broader evidence ecosystem, they can contaminate systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which in turn inform clinical practice guidelines [23]. A 2025 cohort study found that 68 systematic reviews with conclusions distorted by retracted trials were used in 157 clinical guideline documents, demonstrating a direct path from flawed data to clinical practice [23].

Q2: What is the measurable impact of incorporating flawed data from retracted trials into evidence synthesis?

A large-scale 2025 study quantified the impact by re-analyzing 3,902 meta-analyses that had incorporated retracted trials. After removing the retorted trials, the results changed significantly [23]. The table below summarizes the quantitative findings:

Table: Impact of Retracted Trials on Meta-Analysis Results

| Type of Change in Meta-Analysis Results | Percentage of Meta-Analyses Affected |

|---|---|

| Change in the direction of the pooled effect | 8.4% |

| Change in the statistical significance (P value) | 16.0% |

| Change in both direction and significance | 3.9% |

| More than 50% change in the magnitude of the effect | 15.7% |

The study also found that meta-analyses with a lower number of included studies were at a higher risk of being substantially distorted by a retracted trial [23].

Q3: In proteomics, what is the recommended stage for batch effect correction to ensure robust results?

A 2025 benchmarking study in Nature Communications demonstrated that performing batch-effect correction at the protein level is the most robust strategy for mass spectrometry-based proteomics data [20]. This research, using real-world multi-batch data from Quartet protein reference materials, compared correction at the precursor, peptide, and protein levels. The superior performance of protein-level correction enhances the reliability of large-scale proteomics studies, such as clinical trials aiming to discover protein biomarkers [20].

Q4: What are the key signs that my batch effect correction might be too aggressive (over-correction)?

Over-correction risks removing true biological signals, which can be as harmful as not correcting at all. Key signs of over-correction include [14]:

- Clustering of distinct cell types: Biologically distinct cell types are clustered together in visualizations like UMAP plots.

- Loss of expected markers: Canonical cell-type-specific markers are absent in differential expression analysis.

- Non-informative markers: A significant portion of cluster-specific markers are composed of genes with widespread high expression (e.g., ribosomal genes) instead of biologically relevant genes.

Experimental Protocols for Robust Research

Protocol: Quantitative Assessment of Batch Effect Correction Efficacy

This methodology allows researchers to quantitatively benchmark the success of a batch effect correction method, ensuring technical variations are removed without erasing biological truth.

1. Application of Batch Effect Correction: Apply your chosen computational method (e.g., Harmony, ComBat, Seurat) to the dataset with known batch and biological group labels [14] [18].

2. Dimensionality Reduction and Visualization: Generate low-dimensional embeddings (e.g., PCA, UMAP, t-SNE) of the data both before and after correction. Visually inspect the plots to see if samples cluster by biological condition rather than by batch [14] [15].

3. Calculation of Quantitative Metrics: Use the following metrics to objectively evaluate the correction [18]: * Average Silhouette Width (ASW): Measures how similar a cell is to its own cluster compared to other clusters. Higher values indicate better, tighter biological clustering. * Adjusted Rand Index (ARI): Measures the similarity between two clusterings (e.g., before and after correction). It assesses the preservation of biological cell identities. * Local Inverse Simpson's Index (LISI): Measures batch mixing. A higher LISI score indicates better mixing of cells from different batches within a local neighborhood. * k-nearest neighbor Batch Effect Test (kBET): Statistically tests for the presence of residual batch effects by comparing the local batch label distribution around each cell to the global distribution [18].

4. Validation: The correction is successful when batch mixing is high (good LISI/kBET scores) and biological separation is preserved (good ASW/ARI scores) [18].

Diagram: Workflow for validating batch effect correction efficacy, combining visualization and quantitative metrics.

Protocol: Replicating a Meta-Analysis to Check for Contamination by Retracted or Flawed Data

This protocol, derived from a 2025 cohort study, provides a methodology for verifying the robustness of published evidence syntheses [23].

1. Identification of Retracted Trials: Search databases like Retraction Watch to identify retracted randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in your field of interest [23].

2. Forward Citation Searching: Use services like Google Scholar or Scopus to perform a "forward citation search" on each retracted trial. This identifies all subsequent systematic reviews and meta-analyses that have cited and potentially incorporated the flawed data [23].

3. Data Extraction and Replication: For each identified systematic review, extract the quantitative data (e.g., effect sizes, confidence intervals) for all meta-analyses that included the retracted trial [23].

4. Re-analysis: Re-run the meta-analysis, but this time exclude the retracted trial(s). Recalculate the pooled effect size, confidence interval, and p-value for the outcome.

5. Impact Assessment: Compare the new results with the original published results. Assess if the changes are material, focusing on: * A change in the direction of effect. * A loss of statistical significance. * A substantial change (>50%) in the magnitude of the effect [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Computational Tools for Batch Effect Management and Research Integrity

| Tool / Resource Name | Category | Primary Function | Relevance to Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harmony [6] [18] | Batch Correction Algorithm | Integrates single-cell or proteomics data by iteratively clustering cells and removing batch effects. | Effective for single-cell and spatial transcriptomics; recommended for its runtime and performance in benchmarks. |

| ComBat [13] [18] | Batch Correction Algorithm | Uses an empirical Bayes framework to adjust for known batch variables. | Established method for bulk RNA-seq and proteomics data where batch information is clearly defined. |

| Seurat Integration [6] [14] | Batch Correction Tool/Suite | Uses canonical correlation analysis (CCA) and mutual nearest neighbors (MNNs) to find integration "anchors" across datasets. | Popular framework for single-cell data integration, especially when datasets share similar cell types. |

| Retraction Watch Database [23] | Research Integrity Database | Tracks retracted publications across all scientific fields. | Essential for identifying retracted trials during the literature review and evidence synthesis process to prevent data contamination. |

| The Quartet Project [20] | Reference Materials & Data | Provides multi-omics reference materials from four cell lines to benchmark data quality and batch-effect correction methods. | Provides a ground-truth dataset for benchmarking and validating your own batch-effect correction pipelines in proteomics and other omics fields. |

Batch Correction in Practice: Selecting and Applying Algorithms for Multi-Omics Data

Batch effects are technical variations introduced into high-throughput data due to differences in experimental conditions, laboratories, instruments, or analysis pipelines. These unwanted variations are notoriously common in omics data and can lead to misleading outcomes, irreproducible results, and incorrect biological interpretations if not properly addressed. In validation studies and drug development, failure to correct for batch effects can compromise research validity, with documented cases showing how batch effects have even led to incorrect patient treatment decisions. This technical support guide provides troubleshooting assistance for researchers tackling batch effect correction challenges using three prominent algorithmic approaches: location-scale matching, matrix factorization, and deep learning.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How do I determine which batch effect correction algorithm is appropriate for my specific data type and experimental design?

Answer: Algorithm selection depends on your data type, study design, and the nature of batch effects. Use the following decision framework:

1. For multi-omics data integration with reference materials: The ratio-based method (a location-scale approach) has demonstrated superior performance, particularly when batch effects are confounded with biological factors. This method scales absolute feature values of study samples relative to concurrently profiled reference materials [17]. It effectively handles challenging scenarios where biological and technical variables are completely confounded [20].

2. For single-cell RNA sequencing data: Matrix factorization methods like Harmony and Seurat CCA are widely recommended. Benchmarking studies indicate Harmony offers excellent performance with faster runtime, while scANVI performs best though with lower scalability [15]. These methods effectively handle the high technical variations and dropout rates characteristic of single-cell data [2].

3. For large-scale proteomics studies: Recent evidence suggests protein-level correction provides the most robust strategy when combined with ratio-based scaling or other batch effect correction algorithms. Protein-level correction interacts favorably with quantification methods like MaxLFQ, significantly enhancing data integration in large cohort studies [20].

4. When dealing with meta-analyses or heterogeneous data sources: Location-scale models specifically designed for meta-analysis allow researchers to examine not only whether predictor variables are related to the size of effects (location) but also whether they influence the amount of heterogeneity (scale). This dual approach provides enhanced modeling capabilities for complex, variable datasets [24].

Troubleshooting Tip: Always begin by visualizing your data using PCA, t-SNE, or UMAP to assess whether batch effects are present before applying any correction methods. Over-correction can remove biological signals, so validate that distinct cell types remain separable after correction [15].

FAQ 2: What are the key indicators of over-correction, and how can I prevent removing biological signals during batch effect correction?

Answer: Over-correction occurs when batch effect removal algorithms inadvertently eliminate biological variation of interest. Watch for these warning signs:

- Distinct cell types clustering together on dimensionality reduction plots (PCA, t-SNE, or UMAP) that should normally separate [15]

- Complete overlap of samples from very different biological conditions or experiments

- Cluster-specific markers comprised predominantly of genes with widespread high expression across various cell types, such as ribosomal genes

- Loss of expected biological group separation in scenarios where clear differences should persist after correction

Prevention Strategies:

- Utilize reference materials: When available, use well-characterized reference materials processed alongside your samples to guide appropriate correction levels [17]

- Benchmark multiple algorithms: Test different correction methods and compare results to identify potential over-correction artifacts [15]

- Implement negative controls: Maintain samples with known biological differences to verify they remain distinguishable after correction

- Balance aggression parameters: Many algorithms have parameters that control correction strength; start with conservative values and increase gradually [25]

Experimental Protocol for Over-correction Assessment:

- Apply batch effect correction to your data

- Generate UMAP/PCA visualizations coloring points by both batch and biological groups

- Compare pre- and post-correction clustering patterns

- Perform differential expression analysis between known biological groups

- Verify that expected biological markers remain significant after correction

- Check that batch-specific technical markers have been reduced

Assessment Workflow: Systematic approach to identify over-correction in batch effect removal.

FAQ 3: How should I handle severely imbalanced samples across batches, such as when cell type proportions vary significantly?

Answer: Sample imbalance—where cell types, cell numbers, or cell type proportions differ substantially across batches—poses significant challenges for batch correction. This frequently occurs in cancer biology with intra-tumoral and intra-patient heterogeneity [15].

Solution Strategies:

Algorithm Selection for Imbalanced Data:

- For mild imbalance: Harmony or scANVI

- For severe imbalance: LIGER or Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNN)

- Avoid methods that assume balanced group representation across batches

Experimental Design Adjustments:

- Incorporate reference samples in each batch to provide anchor points for correction

- Use sample multiplexing technologies (e.g., cell hashing) when possible

- Stratify sample processing to distribute biological groups across batches

Computational Workflow Modifications:

- Adjust algorithm parameters to account for imbalance

- Implement iterative correction approaches

- Validate with known biological positive controls

Recent benchmarking studies across 2,600 integration experiments demonstrate that sample imbalance substantially impacts downstream analyses and biological interpretation. Follow these field-tested guidelines when working with imbalanced data [15]:

Imbalance Guidelines: Decision workflow for handling sample imbalance in batch correction.

FAQ 4: At which data processing level should I correct batch effects in MS-based proteomics data?

Answer: The optimal correction level depends on your experimental goals and data structure, though recent evidence strongly supports protein-level correction:

Table: Batch Effect Correction Levels in MS-Based Proteomics

| Correction Level | Advantages | Limitations | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor-Level | Early intervention in data pipeline | May not propagate effectively to protein level | When using NormAE requiring m/z and RT features [20] |

| Peptide-Level | Addresses variations before protein quantification | Protein inference may reintroduce batch effects | When specific peptides show consistent batch patterns |

| Protein-Level | Most robust strategy [20]; Directly corrects analyzed features | May miss precursor-specific technical variations | Recommended default approach; Large-scale cohort studies |

Experimental Protocol for Protein-Level Correction:

- Perform standard protein quantification using MaxLFQ, TopPep3, or iBAQ methods

- Aggregate precursor and peptide intensities to protein-level expression values

- Apply batch effect correction algorithms (ComBat, Ratio, RUV-III-C, Harmony, etc.) to the protein-level data matrix

- Validate correction using positive controls and known biological samples

- Assess performance using coefficient of variation (CV) within technical replicates across batches

Performance Insight: The MaxLFQ-Ratio combination at the protein level has demonstrated superior prediction performance in large-scale clinical proteomics studies, making it particularly valuable for Phase 3 clinical trial samples [20].

Algorithm Performance Comparison

Table: Batch Effect Correction Algorithm Performance Characteristics

| Algorithm | Primary Category | Optimal Data Types | Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio-Based Method | Location-Scale | Multi-omics with reference materials | Excellent for confounded designs; Preserves biological signals | Requires reference materials [17] |

| Harmony | Matrix Factorization | scRNA-seq; Multi-omics | Fast runtime; Good for balanced designs [15] | Lower scalability for very large datasets [15] |

| ComBat | Location-Scale | Microarray; Bulk RNA-seq | Established empirical Bayes framework | Assumes balanced batch-group design [17] |

| scANVI | Deep Learning | scRNA-seq | Best overall performance in benchmarks [15] | Computational intensity; Lower scalability [15] |

| RUV Methods | Location-Scale | Bulk RNA-seq | Uses control genes/samples; Flexible framework | Requires negative controls or empirical controls [17] |

| Seurat CCA | Matrix Factorization | scRNA-seq | Effective integration; Widely adopted | Low scalability for massive datasets [15] |

| NormAE | Deep Learning | MS-based proteomics | Handles non-linear batch effects; Uses m/z and RT features | Limited to precursor-level application [20] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Materials for Batch Effect Correction Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Quartet Reference Materials | Multi-omics reference materials from four family members | Provides benchmark datasets for method validation [17] |

| Universal Protein Reference | Quality control samples for proteomics batch monitoring | Enables ratio-based correction in large-scale studies [20] |

| Cell Hashing Reagents | Sample multiplexing for single-cell experiments | Reduces technical variation by processing multiple samples simultaneously [15] |

| Positive Control Samples | Samples with known biological differences | Verification of biological signal preservation after correction [15] |

| Negative Control Samples | Technical replicates across batches | Assessment of pure technical variation independent of biology [25] |

Effective batch effect correction requires careful algorithm selection based on specific experimental designs, data types, and potential confounding factors. Location-scale methods like the ratio-based approach excel in confounded scenarios with reference materials, matrix factorization methods like Harmony provide robust performance for single-cell data, and deep learning approaches like scANVI offer superior accuracy at the cost of computational resources. By implementing the troubleshooting guidelines, experimental protocols, and validation strategies outlined in this technical support document, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and reproducibility of their validation studies and drug development pipelines.

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and performance of the five highlighted batch effect correction methods, based on comprehensive benchmark studies. This overview serves as a quick reference for selecting an appropriate method.

Table 1: Method Overview and Benchmarking Summary

| Method | Core Algorithm | Primary Output | Key Strengths | Considerations / Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harmony [26] [14] | Iterative clustering in PCA space; maximizes batch diversity within clusters. | Low-dimensional embedding. | Fast runtime, high efficacy in batch mixing, handles multiple batches well [26]. | Does not return a corrected expression matrix, limiting some downstream analyses [27] [28]. |

| Seurat 3 [26] [14] | Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) and Mutual Nearest Neighbors (MNNs) as "anchors". | Corrected expression matrix or low-dimensional space. | High accuracy in integrating datasets with shared and distinct cell types; returns corrected matrix [26]. | Can be computationally demanding for very large datasets; risk of overcorrection if parameters are misused [28]. |

| LIGER [26] [14] | Integrative Non-negative Matrix Factorization (iNMF). | Low-dimensional factors (batch-specific and shared). | Distinguishes between technical and biological variation (e.g., from different conditions) [26]. | The multi-step process can be more complex to implement than other methods [26]. |

| ComBat [26] [10] | Empirical Bayes framework to adjust for additive and multiplicative batch effects. | Corrected expression matrix. | Effective systematic batch effect removal; preserves the order of gene expression ("order-preserving") [27] [29]. | Assumes a Gaussian distribution, which can be a limitation for sparse scRNA-seq data; may not handle complex, nonlinear batch effects well [26]. |

| limma [26] [10] | Linear models with batch included as a covariate. | Model-ready data or a corrected expression matrix via removeBatchEffect. |

Well-integrated into the limma differential expression analysis pipeline; simple and effective for balanced designs [26] [10]. | Primarily designed for bulk RNA-seq; performance may be suboptimal for the high sparsity and noise of scRNA-seq data [26]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics from Benchmark Studies [26]

| Method | Computational Speed | Batch Mixing (kBET/LISI) | Cell Type Conservation (ARI/ASW) | Recommended Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harmony | ★★★★★ | ★★★★☆ | ★★★★☆ | First choice for fast, effective integration of multiple batches. |

| Seurat 3 | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★★☆ | ★★★★★ | Datasets with non-identical cell types; when a corrected count matrix is needed. |

| LIGER | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★★☆ | ★★★★☆ | When biological variation across conditions must be preserved. |

| ComBat | ★★★★☆ | ★★☆☆☆ | ★★★☆☆ | Systematic batch effect correction in simpler, less sparse datasets. |

| limma | ★★★★★ | ★★☆☆☆ | ★★★☆☆ | Quick correction in balanced designs, integrated with limma DE analysis. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can I visually detect batch effects in my single-cell RNA-seq dataset before correction? The most common and effective way to identify batch effects is through visualization via dimensionality reduction. You should perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or use methods like t-SNE and UMAP on your raw, uncorrected data. Color the resulting plot by batch. If samples or cells cluster strongly by their batch of origin rather than by their known biological groups (e.g., cell type or experimental condition), this indicates a significant batch effect [14] [10]. Conversely, after successful batch correction, the cells from different batches should be intermingled within biological clusters [14].

Q2: What are the key signs that my data has been overcorrected? Overcorrection occurs when a batch effect method removes not just technical variation but also true biological signal. Key signs include [14] [28]:

- Loss of Canonical Markers: The absence of expected cluster-specific markers (e.g., a known T-cell marker not appearing in the T-cell cluster).

- Poorly Defined Clusters: A significant overlap among markers for different clusters, or clusters becoming poorly separated.

- Non-Biological Marker Genes: Cluster-specific markers comprising genes with widespread high expression (e.g., ribosomal genes) rather than biologically informative ones.

- Scarce Differential Expression: A notable absence of differential expression hits in pathways that are expected based on the experimental design.

- Distorted Biology: Evaluation metrics like RBET may show a biphasic response, where performance first improves with correction strength but then worsens as overcorrection sets in [28].

Q3: Is batch effect correction for single-cell data the same as for bulk RNA-seq data? While the purpose is the same—to mitigate technical variation—the algorithms and their applicability differ. Single-cell RNA-seq data is characterized by high sparsity (many zero counts) and high technical noise. Therefore, techniques designed for bulk RNA-seq, like ComBat or limma, might be insufficient or perform suboptimally on scRNA-seq data [14]. Conversely, single-cell-specific methods (Harmony, Seurat, LIGER) are designed to handle this sparsity and complexity but may be excessive for the smaller, less sparse datasets typical of bulk RNA-seq [14].

Q4: What quantitative metrics can I use to evaluate the success of batch effect correction beyond visual inspection? Relying solely on visualizations like UMAP plots can be subjective. It is recommended to use quantitative metrics [26] [14] [28]:

- kBET (k-nearest neighbor batch effect test): Measures batch mixing on a local level. A lower rejection rate indicates better mixing [26].

- LISI (Local Inverse Simpson's Index): Measures the diversity of batches in the local neighborhood of each cell. A higher LISI score indicates better batch mixing [26].

- ASW (Average Silhouette Width): Measures cluster compactness and separation. It can be used on cell type labels (higher is better) or batch labels (lower is better) [26].

- ARI (Adjusted Rand Index): Measures the similarity between two clusterings, often used to compare cell type clustering before and after integration [26].

- RBET (Reference-informed Batch Effect Test): A newer metric that uses reference genes to evaluate correction and is sensitive to overcorrection [28].

Common Error Scenarios and Resolutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor batch mixing after correction. | Incorrect parameter tuning (e.g., number of anchors, neighbors, or dimensions). | Re-run the method with a focus on key parameters. For Seurat, adjust the k.anchor and k.filter parameters. For Harmony, adjust the theta (diversity clustering) and lambda (ridge regression) parameters. |

| Loss of rare cell populations. | Overcorrection or algorithm parameters that smooth out small, distinct groups. | Use a method known for preserving biological variation, like LIGER. Ensure the parameter for the number of neighbors or anchors is not set too high, which can lead to over-smoothing [28]. |

| Method fails to run or is extremely slow on a large dataset. | Dataset is too large for the memory or computational capacity of the method. | For very large datasets (>100k cells), ensure you are using methods benchmarked for scale, such as Harmony [26]. Alternatively, use tools that support disk-based or out-of-memory operations. |

| Corrected data yields poor downstream differential expression results. | Overcorrection has stripped away biological signal along with batch effects [14]. | Try a less aggressive correction method or adjust parameters. Consider using a method that returns a corrected count matrix (like Seurat or scGen) or including batch as a covariate in your differential expression model instead of pre-correcting the data [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

To rigorously benchmark batch effect correction methods, a standardized workflow and evaluation framework is essential. The following diagram and protocol outline this process.

Workflow for Benchmarking Batch Correction Methods

Protocol 1: Standardized Benchmarking Workflow

This protocol is adapted from large-scale benchmark studies [26] [28].

Data Preparation:

- Input: Select multiple scRNA-seq datasets with known batch effects and validated cell type annotations. Ideal test cases include datasets with identical cell types sequenced using different technologies (e.g., 10x vs. SMART-seq) and datasets with partially overlapping cell types.

- Preprocessing: Follow the standard preprocessing pipeline for each method. This typically includes library size normalization, log transformation, and the selection of Highly Variable Genes (HVGs). For a fair comparison, it is recommended to use a common set of HVGs across all methods where possible [26].

Method Application:

- Apply each batch correction method (Harmony, Seurat, LIGER, etc.) to the integrated datasets according to their official documentation and best practices.

- Record computational resources, including runtime and memory usage, especially for large datasets [26].

Performance Evaluation:

- Visual Inspection: Generate UMAP or t-SNE plots of the integrated data, coloring cells by both batch and cell type. Successful correction will show mixing by batch and separation by cell type [26] [14].

- Quantitative Metrics: Calculate a suite of metrics:

- Batch Mixing: Use kBET (lower is better) or LISI (higher is better) to quantify how well batches are mixed [26] [28].

- Biological Integrity: Use ARI (higher is better) to measure how well the method preserves the original cell type clustering, and ASW (higher for cell type, lower for batch) to measure cluster compactness [26].

- Biological Validation: Perform differential expression analysis on known marker genes after correction. A good method will facilitate the identification of these markers without introducing spurious signals [26] [14].

Protocol 2: Assessing Overcorrection with RBET

The RBET framework provides a robust way to evaluate correction quality and detect overcorrection [28].

Reference Gene (RG) Selection:

- Strategy 1 (Preferred): Curate a list of experimentally validated tissue-specific housekeeping genes from published literature to use as RGs.

- Strategy 2 (Default): Directly select genes from the dataset that are stably expressed both within and across phenotypically different cell clusters.

Batch Effect Detection on RGs:

- Map the integrated dataset (before and after correction) into a two-dimensional space using UMAP.

- Apply the maximum adjusted chi-squared (MAC) statistics to test for batch effect specifically on the RGs. A smaller RBET value indicates better correction.

Interpretation:

- Monitor the RBET value as you adjust correction strength (e.g., by increasing the number of anchors

kin Seurat). A biphasic trend—where RBET first decreases and then increases with stronger correction—signals the onset of overcorrection [28].

- Monitor the RBET value as you adjust correction strength (e.g., by increasing the number of anchors

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Resources for Batch Effect Correction Research

| Item Name | Function / Role | Example Use in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Seurat (v3+) [26] [6] | A comprehensive R toolkit for single-cell genomics. Its integration functions use CCA and MNN "anchors" to align datasets. | The primary tool for performing Seurat-based integration and a common environment for preprocessing data for other methods. |

| Harmony [26] [6] | An R package that rapidly integrates multiple datasets by iteratively clustering cells in PCA space and correcting for batch effects. | Used as a fast, first-pass integration method, especially for large datasets or when computational runtime is a concern. |

| LIGER [26] [14] | An R package that uses integrative non-negative matrix factorization (iNMF) to factorize multiple datasets into shared and dataset-specific factors. | Applied when integrating datasets from different biological conditions to explicitly distinguish technical from biological variation. |

| sva package (ComBat) [26] [10] | An R package containing the ComBat function, which uses an empirical Bayes framework to adjust for batch effects. | Used for correcting systematic batch effects in contexts where data distributional assumptions are met, or as a baseline method in benchmarks. |

| limma [26] [10] | An R package for the analysis of gene expression data, featuring the removeBatchEffect function. |

Employed for simple, linear batch effect adjustment, often within a differential expression analysis pipeline. |

| Scanorama [26] [14] | A method that efficiently finds mutual nearest neighbors (MNNs) across datasets in a scalable manner. | Used for integrating large numbers of datasets and as a high-performing alternative in benchmark studies. |

| Polly | A data processing and validation platform (from Elucidata) that often employs Harmony and quantitative metrics for batch correction [14]. | Example of a commercial platform that incorporates batch correction methods and verification for delivered datasets. |

| kBET & LISI Metrics | Quantitative metrics packaged as R functions to evaluate the success of batch mixing after correction [26] [28]. | Essential for the objective, quantitative evaluation of any batch correction method's performance, moving beyond visual inspection. |

At which data level should I correct for batch effects in my proteomics experiment?

Answer: Current comprehensive benchmarking studies indicate that applying batch-effect correction at the protein level is the most robust strategy for most mass spectrometry-based proteomics experiments [20] [30].

Research comparing correction at precursor, peptide, and protein levels has demonstrated that protein-level correction consistently performs well across various experimental scenarios and quantification methods. This approach effectively reduces technical variations while preserving biological signals of interest in large-scale cohort studies [20].

Table 1: Comparison of Batch-Effect Correction Levels

| Correction Level | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Level | Most robust strategy; preserves biological signals; works well with various algorithms [20] | May not address early-stage technical variations | Recommended for most applications, especially large-scale studies |

| Peptide-Level | Corrects before protein inference | May interact unpredictably with protein quantification algorithms [20] | When specific peptides show strong batch effects |

| Precursor-Level | Earliest correction point in workflow | Limited algorithm support; not all tools accept precursor data [20] | Specialized cases with precursor-specific issues |

Which batch-effect correction algorithm should I choose for confounded experimental designs?

Answer: When your biological groups are completely confounded with batch groups (e.g., all samples from condition A processed in batch 1, all from condition B in batch 2), the ratio-based method has demonstrated superior performance according to multi-omics benchmarking studies [17].

The ratio method scales absolute feature values of study samples relative to those of concurrently profiled reference materials. This approach effectively distinguishes biological differences from technical variations even in challenging confounded scenarios where many other algorithms fail [17].

Table 2: Batch-Effect Correction Algorithm Performance

| Algorithm | Balanced Scenarios | Confounded Scenarios | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio-Based | Good performance [17] | Superior performance [17] | Requires reference materials; scales to reference |

| ComBat | Good performance [17] | Limited effectiveness [17] | Empirical Bayesian framework |

| Harmony | Good performance [17] | Limited effectiveness [17] | PCA-based iterative clustering |

| RUV-III-C | Varies | Varies | Uses linear regression to remove unwanted variation [20] |

| Median Centering | Varies | Varies | Simple mean/median normalization [20] |

What experimental design considerations are crucial for effective batch-effect correction?

Answer: Proper experimental design is fundamental for successful batch-effect correction:

- Include Reference Materials: Profile universal reference samples (e.g., Quartet protein reference materials) in each batch to enable ratio-based correction [20] [17]

- Randomize Samples: Distribute biological groups evenly across batches whenever possible to avoid confounding [31]

- Record Technical Factors: Document all technical variables (reagent lots, instruments, operators) for later correction [31]

- Include Quality Controls: Regularly inject control sample mixes (every 10-15 samples) to monitor technical performance [31]

How do protein quantification methods interact with batch-effect correction?

Answer: The effectiveness of batch-effect correction depends on your protein quantification method. Benchmarking studies reveal significant interactions between quantification methods and correction algorithms [20].

For large-scale proteomic studies, the MaxLFQ quantification method combined with ratio-based correction has shown superior prediction performance, particularly evident in studies involving thousands of patient samples [20].

What quality control metrics should I use after batch-effect correction?

Answer: After applying batch-effect correction, assess these key quality metrics:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Measures biological group separation in PCA space [20] [17]

- Coefficient of Variation (CV): Assesses technical variation within replicates across batches [20]

- Correlation Coefficients: Evaluates agreement with reference datasets [20]

- Cluster Analysis: Checks if samples group by biology rather than batch [17]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Batch-Effect Correction | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quartet Reference Materials | Provides multi-omics reference standards for ratio-based correction | Profile alongside study samples in each batch [20] [17] |

| Universal Proteomics Standards | Enables accuracy assessment of quantification and correction | Use spiked-in standards to evaluate performance [32] |

| Quality Control Samples | Monitors technical performance across batches | Inject control sample mix every 10-15 runs [31] |

| proBatch R Package | Implements specialized proteomics batch correction | Normalization, diagnostic visualization, and correction [31] |

How do I handle completely confounded batch and biological effects?

Answer: When biological and technical factors are completely confounded, most conventional batch-effect correction algorithms fail because they cannot distinguish biological differences from technical variations [17]. In these challenging scenarios:

- Ratio-based correction using reference materials is the only method that maintains effectiveness [17]

- The approach transforms absolute expression values to ratios relative to concurrently profiled reference materials

- This scaling preserves true biological differences while removing batch-specific technical variations

For experimental planning, whenever possible, avoid completely confounded designs through careful sample randomization across batches [31]. When confounding is unavoidable, ensure you include appropriate reference materials in each batch to enable effective correction.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental difference between normalization and batch effect correction?

Normalization and batch effect correction are distinct but sequential steps in data preprocessing. Normalization operates on the raw count matrix and aims to adjust for cell-specific technical biases, such as differences in sequencing depth (library size) and RNA capture efficiency [33] [14]. Its goal is to make gene expression counts comparable within and between cells from the same batch [34].

In contrast, batch effect correction typically acts on the normalized (and often dimensionally-reduced) data to remove technical variations between different experimental batches. These batch effects arise from factors like different sequencing platforms, reagent lots, or handling personnel [6] [33] [14].

2. How do I choose a batch correction method that is compatible with my workflow?

Selecting a batch correction algorithm (BECA) should not be based on popularity alone. It is crucial to prioritize methods that are compatible with your entire data processing workflow, from raw data to functional analysis [9]. Consider the following:

- Assumptions: Check if the BECA's assumptions about the data (e.g., additive or multiplicative batch effects) align with the output of your normalization step [9].

- Data Type: Some methods are designed specifically for the high sparsity and scale of single-cell data, while others may be more suited for bulk analyses [14].

- Downstream Goals: Ensure the corrected data retains the biological variation necessary for your specific downstream analysis, such as identifying subtle subpopulations.

3. What are the signs of overcorrection, and how can I avoid them?

Overcorrection occurs when a batch effect correction method removes genuine biological variation along with technical noise. Key signs include [14] [15]:

- Cluster Merging: Distinct cell types are incorrectly clustered together on a UMAP or t-SNE plot.

- Loss of Markers: A notable absence of expected cell-type-specific marker genes in differential expression analysis.

- Non-informative Markers: Cluster-specific markers are dominated by genes with widespread high expression (e.g., ribosomal genes) rather than defining biological functions.

- Complete Overlap: An implausible, complete overlap of samples from very different biological conditions.

To avoid overcorrection, test multiple BECAs and compare results. If signs appear, try a less aggressive correction method [15].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standardized Workflow for Single-Cell Data Integration (e.g., SCTransform + Harmony)

This industry-standard workflow is available on platforms like the 10x Genomics Cloud Analysis platform [35].

- Input: Requires raw

.cloupefiles fromcellranger countorcellranger multipipelines. Ensure feature sets (genes) are consistent across files [35]. - Normalization & Variance Stabilization: Apply SCTransform to each sample independently. This method uses regularized negative binomial regression to normalize gene expression data, model technical variation, and stabilize variance [35].

- Integration & Batch Correction: Run Harmony on the SCTransform-normalized data. Harmony integrates data from multiple samples by iteratively clustering cells in a low-dimensional space (e.g., PCA) and correcting for batch-specific effects, while preserving biological differences [35].

- Downstream Analysis: The output is a batch-corrected matrix and embeddings ready for clustering, dimensionality reduction (UMAP/t-SNE), and differential expression analysis [35].

Protocol 2: Bulk RNA-seq Batch Effect Correction with Linear Models

For bulk RNA-seq data where the source of variation is known, a common approach uses linear models.

- Input: A normalized count matrix (e.g., using TMM, UQ, or Median normalization from packages like

edgeRorDESeq2) [36] [37]. - Batch Effect Removal: Use functions like

removeBatchEffect()from thelimmaR package orComBat()from thesvapackage [9]. These functions fit a linear model to each gene's expression profile, including batch as a covariate, and then set the batch effect to zero to compute corrected values. - Assumption Check: This method assumes the composition of cell types is similar across batches and that the batch effect is additive [38]. It is most effective for technical replicates.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key software tools and their primary functions in normalization and batch effect correction workflows.

| Tool/Package Name | Primary Function | Brief Description of Role |

|---|---|---|