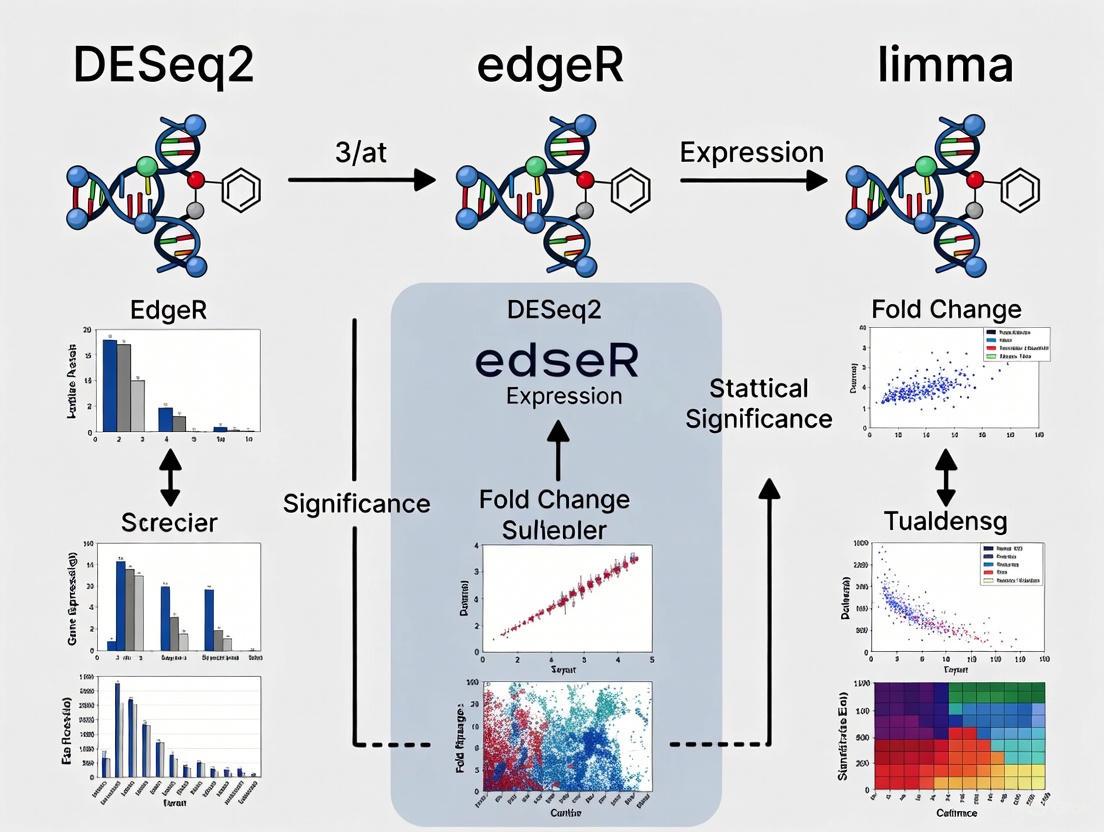

Benchmarking Differential Expression Tools: A Practical Guide to Choosing Between DESeq2, edgeR, and limma

Selecting the optimal tool for differential expression (DE) analysis is a critical decision in RNA-seq studies, directly impacting the biological insights gained.

Benchmarking Differential Expression Tools: A Practical Guide to Choosing Between DESeq2, edgeR, and limma

Abstract

Selecting the optimal tool for differential expression (DE) analysis is a critical decision in RNA-seq studies, directly impacting the biological insights gained. This article provides a comprehensive, evidence-based guide for researchers and bioinformaticians on the three most widely used DE tools: DESeq2, edgeR, and limma (voom). We synthesize findings from recent benchmarking studies to explain the core statistical foundations of each method, provide practical workflows for implementation, address common challenges like small sample sizes and batch effects, and offer direct performance comparisons. Our goal is to empower you to make an informed tool selection for your specific experimental design and data characteristics, thereby ensuring robust, reliable, and interpretable results in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding the Core Statistical Engines: How DESeq2, edgeR, and limma Work

In the field of genomics research, particularly in differential gene expression (DGE) analysis from RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data, the choice of statistical model fundamentally shapes the reliability and interpretation of results. Next-generation sequencing technologies generate complex count-based data that require specialized statistical approaches to distinguish biological signals from technical noise and natural variability. The core methodological division in this domain lies between negative binomial regression and linear modeling frameworks, each with distinct theoretical foundations and practical implications.

RNA-seq data analysis presents unique challenges that demand robust statistical solutions. The data are characterized by their high dimensionality, with tens of thousands of genes measured across typically limited sample sizes, and inherent technical variability introduced during library preparation and sequencing. Furthermore, count-based expression measurements often exhibit overdispersion—where the variance exceeds the mean—violating key assumptions of traditional parametric tests. These characteristics have spurred the development of specialized tools, primarily DESeq2, edgeR, and limma, which implement different statistical approaches to address these challenges while optimizing for power, false discovery control, and computational efficiency.

Theoretical Foundations

Negative Binomial Distribution and Regression

The negative binomial distribution is a discrete probability distribution that models the number of failures in a sequence of independent and identically distributed Bernoulli trials before a specified number of successes occurs. In the context of RNA-seq data analysis, it serves as a flexible extension to the Poisson distribution for modeling count data where the variance exceeds the mean.

The probability mass function of the negative binomial distribution is defined as:

$$f(k; r, p) = \binom{k + r - 1}{k} (1-p)^k p^r$$

Where k is the number of failures, r is the number of successes, and p is the probability of success in each trial. For RNA-seq applications, the distribution is reparameterized in terms of the mean μ and dispersion parameter, providing a more intuitive framework for modeling count data [1].

The key advantage of the negative binomial distribution for genomic applications is its ability to model overdispersed count data through the dispersion parameter, which accommodates the extra-Poisson variation commonly observed in sequencing experiments. The variance of a negative binomial random variable Y is given by:

$$var(Y) = \mu + \mu^2/k$$

where k is the dispersion parameter. As k approaches infinity, the variance converges to the mean, and the negative binomial distribution reduces to the Poisson distribution. This relationship makes the negative binomial model a generalized form that can adapt to the degree of overdispersion present in the data [2].

Negative binomial regression extends this distribution to a regression framework, allowing researchers to model count outcomes as functions of predictor variables while accounting for overdispersion. This approach is particularly valuable in genomics because it explicitly models the mean-variance relationship in count data, providing more accurate inference compared to Poisson regression when overdispersion is present.

Linear Modeling with Empirical Bayes Moderation

Linear models form the foundation of many statistical approaches, assuming a continuous, normally distributed response variable. For RNA-seq data analysis, the limma package employs a modified linear modeling approach that incorporates specific adaptations to handle count-based expression data.

The core linear model can be represented as:

$$Y = X\beta + \epsilon$$

Where Y is the response vector, X is the design matrix of predictors, β is the coefficient vector, and ε represents normally distributed errors with constant variance.

The fundamental challenge in applying linear models to RNA-seq data is the violation of normality and homoscedasticity assumptions. Count data are inherently discrete and often exhibit variance that depends on the mean expression level. To address these limitations, limma employs a voom transformation that converts count data to log-counts per million (log-CPM) values and estimates mean-variance relationships to compute precision weights for each observation. This transformation allows the application of linear modeling frameworks while accounting for heteroscedasticity [3].

A key innovation in limma is the application of empirical Bayes moderation, which borrows information across genes to stabilize variance estimates. This approach is particularly powerful in genomics experiments with small sample sizes, where gene-specific variance estimates would otherwise be unreliable. By shrinking extreme variance estimates toward a common value, limma improves the reliability of statistical inference and increases power to detect differentially expressed genes [3].

Direct Comparative Analysis

Core Methodological Differences

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Negative Binomial and Linear Modeling Approaches

| Aspect | Negative Binomial Approach | Linear Modeling Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Discrete probability distribution for overdispersed count data | Continuous probability distribution with normality assumptions |

| Variance Handling | Explicit modeling via dispersion parameter: $var(Y) = \mu + \mu^2/k$ | Precision weights based on mean-variance relationship (voom) |

| Data Type | Raw counts | Transformated counts (log-CPM) |

| Dispersion Estimation | Gene-specific dispersion with empirical Bayes shrinkage | Mean-variance trend with empirical Bayes moderation |

| Distributional Assumptions | Negative binomial distribution | Normal distribution after transformation |

The negative binomial and linear modeling approaches differ fundamentally in their treatment of count data. Negative binomial models, as implemented in DESeq2 and edgeR, treat RNA-seq counts as realizations of a negative binomial process, explicitly modeling the mean and variance through parameters that capture both expression level and overdispersion. This approach maintains the discrete nature of the data throughout the analysis pipeline, with dispersion parameters estimated through sophisticated shrinkage methods that balance gene-specific and global information [2] [4].

In contrast, the linear modeling approach implemented in limma transforms count data to continuous values that better satisfy normality assumptions. The voom transformation not only converts counts to log-CPM values but also calculates precision weights for each observation based on the predicted mean-variance relationship. These weights ensure that observations with lower expected variability (typically low-count genes) receive less influence in the model fitting process, while observations with higher expected variability receive more weight. This approach effectively handles heteroscedasticity while leveraging the computational efficiency and flexibility of linear model frameworks [3].

Performance Characteristics

Table 2: Performance Comparison of RNA-seq Differential Expression Tools

| Tool | Core Method | Ideal Sample Size | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial regression with empirical Bayes shrinkage | ≥3 replicates, performs better with more | Robust with high biological variability, strong FDR control, automatic outlier detection | Computationally intensive for large datasets, conservative fold change estimates |

| edgeR | Negative binomial regression with flexible dispersion estimation | ≥2 replicates, efficient with small samples | Excellent with low-count genes, multiple testing strategies, technical replicates | Requires careful parameter tuning, common dispersion may miss gene-specific patterns |

| limma-voom | Linear modeling with voom transformation and empirical Bayes moderation | ≥3 replicates per condition | Handles complex designs elegantly, computational efficiency, integrates with other omics | May not handle extreme overdispersion well, requires careful QC of voom transformation |

Benchmarking studies have revealed nuanced performance differences between these approaches. A comprehensive evaluation of five DGE models (DESeq2, voom+limma, edgeR, EBSeq, NOISeq) found that while all methods showed reasonable performance, their relative robustness followed specific patterns. Overall, the non-parametric method NOISeq was most robust, followed by edgeR, voom, EBSeq, and DESeq2. These patterns proved dataset-agnostic and reliable for drawing conclusions when sample sizes were sufficiently large [5].

Another independent benchmarking study comparing StringTie2, bambu, DESeq2, edgeR and limma-voom found that DESeq2, edgeR and limma-voom performed best among differential transcript expression tools tested [6]. The specific advantages of each tool often depend on experimental conditions—limma demonstrates remarkable versatility and computational efficiency, particularly with large-scale datasets, while edgeR excels in analyzing genes with low expression counts where its flexible dispersion estimation better captures variability in sparse count data [3].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Negative Binomial Regression Implementation

The implementation of negative binomial regression in RNA-seq analysis follows a structured workflow with specific steps for normalization, dispersion estimation, and statistical testing. DESeq2 and edgeR, while sharing a common theoretical foundation, differ in their specific algorithmic approaches.

DESeq2 Workflow:

- Data Input: Raw count matrix with genes as rows and samples as columns

- Normalization: Median-of-ratios method to correct for library size and RNA composition biases

- Dispersion Estimation: Gene-wise dispersion estimates followed by empirical Bayes shrinkage toward a fitted trend

- Model Fitting: Generalized linear model with negative binomial family and logarithmic link function

- Hypothesis Testing: Wald tests or likelihood ratio tests with Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction

edgeR Workflow:

- Data Input: Raw count matrix organized as a DGEList object

- Normalization: Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) method to account for compositional differences

- Dispersion Estimation: Common, trended, or tagwise dispersion estimates using empirical Bayes methods

- Model Fitting: Generalized linear models with quantile-adjusted conditional maximum likelihood

- Hypothesis Testing: Exact tests, likelihood ratio tests, or quasi-likelihood F-tests

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in negative binomial-based RNA-seq analysis:

Linear Modeling with Voom Transformation

The limma-voom approach implements a different workflow that transforms count data to enable the application of linear models:

Limma-voom Workflow:

- Data Input: Raw count matrix with genes as rows and samples as columns

- Filtering: Remove lowly expressed genes (e.g., requiring minimum counts per million in a minimum number of samples)

- Normalization: Between-sample normalization using TMM or quantile methods

- Voom Transformation: Convert counts to log-CPM values with precision weights

- Linear Modeling: Fit linear models to transformed data

- Empirical Bayes Moderation: Shrink gene-wise variances toward a common value

- Hypothesis Testing: Moderated t-statistics with Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction

The workflow for limma-voom analysis can be visualized as follows:

Benchmarking Results and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Multiple benchmarking studies have evaluated the performance of negative binomial and linear modeling approaches using both real and synthetic datasets. These evaluations typically assess methods based on sensitivity, false discovery rate control, computational efficiency, and robustness to varying experimental conditions.

Table 3: Benchmarking Results from Comparative Studies

| Study | Dataset Characteristics | Top Performing Methods | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sciencedirect (2022) [5] | Breast cancer data; full and reduced sample sizes | NOISeq > edgeR > voom > EBSeq > DESeq2 | Pattern of robustness was dataset-agnostic; performance consistent with sufficient sample sizes |

| RNA-seq Blog (2022) [6] | Human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines with spike-ins | DESeq2, edgeR, limma-voom | All three methods performed best for differential transcript expression; no clear front-runner |

| BMC Genomics (2024) [7] | Plant pathogenic fungi, animal, and plant data | Tool performance varied by species | No single tool performed optimally across all species; recommendations should be species-specific |

A rigorous evaluation of DGE methods using controlled analyses of fixed count matrices from breast cancer datasets found distinct patterns of robustness across methods. The study evaluated performance at different expression levels (high and low) and used unbiased metrics including test sensitivity estimated as relative false discovery rate (FDR) and concordance between model outputs. The overall robustness pattern showed NOISeq as the most robust, followed by edgeR, voom, EBSeq, and DESeq2. These patterns proved consistent across datasets when sample sizes were sufficiently large [5].

Another benchmarking experiment using human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines with synthetic spike-in RNAs (sequins) created in silico mixture samples to assess performance in the absence of true positives or true negatives. The results demonstrated that DESeq2, edgeR and limma-voom were the best performers among the five differential transcript expression tools tested [6].

Concordance Across Methods

Despite their methodological differences, studies have shown remarkable agreement between the DEGs identified by negative binomial-based tools (DESeq2, edgeR) and linear modeling approaches (limma-voom). One analysis reported substantial overlap in significant DEGs identified by all three methods, strengthening confidence in results when different statistical approaches converge on similar biological conclusions [3].

The agreement between methods tends to be higher for genes with large fold changes and strong statistical support, while discrepancies often occur for genes with subtle expression differences or unusual expression characteristics. This concordance pattern underscores the complementary nature of these approaches and supports the practice of using multiple methods to increase confidence in identified DEGs, particularly for follow-up experimental validation.

Practical Implementation Guidelines

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools and Packages for Differential Expression Analysis

| Tool/Package | Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial-based DGE analysis | R/Bioconductor |

| edgeR | Negative binomial-based DGE analysis | R/Bioconductor |

| limma | Linear modeling framework | R/Bioconductor |

| voom | Mean-variance transformation for count data | Part of limma package |

| FastQC | Quality control of raw sequencing reads | Java application |

| Trimmomatic | Adapter trimming and quality filtering | Java application |

| Salmon | Transcript quantification | C++ application |

| tximport | Import transcript-level estimates | R/Bioconductor |

Selection Criteria for Method Choice

The choice between negative binomial and linear modeling approaches depends on multiple factors related to experimental design, data characteristics, and research objectives:

Sample Size Considerations:

- For very small sample sizes (n < 5 per group), edgeR's robust dispersion estimation often provides advantages

- For moderate to large sample sizes (n > 10 per group), all three methods perform well, with DESeq2 offering strong FDR control

- For complex experimental designs with multiple factors, limma's flexible linear modeling framework excels

Data Characteristics:

- For data with extreme overdispersion, negative binomial approaches (particularly edgeR) may be more appropriate

- For data with strong batch effects or technical artifacts, limma's integration with combat or other batch correction methods is advantageous

- For experiments focusing on low-abundance transcripts, edgeR's handling of low-count genes provides benefits

Computational Considerations:

- For large-scale datasets (thousands of samples), limma offers superior computational efficiency

- For standard-sized experiments (10-100 samples), all three tools have reasonable computational requirements

- For pipeline automation, DESeq2's automated outlier detection and independent filtering can streamline analysis

The field continues to evolve with emerging methodologies that blend aspects of both approaches. Recent developments include improved shrinkage estimators for dispersion parameters in negative binomial models and enhanced variance modeling in transformed linear models. As single-cell RNA-seq technologies become more prevalent, adaptations of both frameworks are being developed to handle the additional zero-inflation and technical variability characteristic of these data.

In RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, the data generated are not absolute measurements but relative abundances [8]. The total number of sequenced reads (library size) is a technical constraint, meaning the count for an individual gene is only interpretable relative to the counts of all other genes in that sample [8]. Normalization is the critical computational process that removes these technical artifacts, such as differences in sequencing depth and RNA composition, to enable accurate biological comparisons [9].

Within the context of benchmarking differential expression tools like DESeq2, edgeR, and limma, the choice of data transformation and normalization method is foundational. These tools employ distinct core strategies: DESeq2 uses the Median of Ratios method, edgeR uses the Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM), and limma, when applied to RNA-seq data, typically uses the voom transformation. Understanding these methodologies is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select the appropriate tool and interpret results reliably for robust biomarker discovery and diagnostic development.

Core Methodologies and Statistical Foundations

The three methods—TMM, Median of Ratios, and voom—represent different philosophical and statistical approaches to preparing RNA-seq count data for differential expression analysis.

Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) - edgeR

TMM normalization is designed to be robust against highly expressed genes and differences in RNA composition between samples [9]. The method operates under the assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed (DE) [10].

- Core Protocol: TMM calculates scaling factors between a test sample and a reference sample (often an actual sample chosen from the dataset). It considers the log-fold-changes (M-values) and absolute expression levels (A-values) for all genes.

- Key Steps:

- M-value Calculation: For each gene, compute the log2 ratio of expression between the test and reference sample ( M = \log2(\frac{test}{reference}) ).

- A-value Calculation: Compute the average log expression ( A = \frac{1}{2} \times \log2(test \times reference) ).

- Trimming: Genes with extreme M-values (differential expression) and extreme A-values (very high or low expression) are trimmed.

- Weighted Average: A weighted average of the remaining M-values is calculated, with weights derived from the inverse of the approximate asymptotic variances. This final average is the TMM scaling factor for that test sample [10].

Median of Ratios - DESeq2

The Median of Ratios method, used by DESeq2, is also predicated on the assumption that the majority of genes are not DE [10]. It is considered a robust method that can handle large variations in expression levels [9].

- Core Protocol: The method computes a scaling factor for each sample by finding the median of the ratios of a gene's count to its geometric mean across all samples.

- Key Steps:

- Geometric Mean Calculation: For each gene, calculate its geometric mean across all samples.

- Ratio Calculation: For each gene in a sample, compute the ratio of its count to the gene's geometric mean.

- Scaling Factor: The scaling factor for a given sample is the median of all gene ratios for that sample, excluding genes with a geometric mean of zero [10].

voom - limma

The voom method differs fundamentally from TMM and Median of Ratios. Rather than being a pure normalization method, it is a data transformation and weighting procedure that adapts the mature empirical Bayes linear modeling framework of limma—originally developed for microarray data—for RNA-seq count data [11].

- Core Protocol: voom estimates the mean-variance relationship of the log-counts and generates a precision weight for each observation, which are then fed into the limma analysis pipeline [11].

- Key Steps:

- Log-Transformation: Counts are converted to log-counts per million (log-cpm) to account for sequencing depth.

- Linear Modeling: A linear model is fitted to the log-cpm values for each gene.

- Mean-Variance Trend: The square-root of the residual standard deviation of each gene is plotted against its average log-count.

- Precision Weights: A smoothed curve is fitted to this mean-variance trend, which is used to assign a precision weight to every single observed log-cpm value. These weights are used in the downstream linear modeling in limma to account for heteroscedasticity [11].

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow of the voom method:

Comparative Analysis and Benchmarking

A systematic comparison of these methods reveals their relative strengths, ideal use cases, and performance characteristics, which is crucial for informed tool selection.

Method Comparison Table

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the normalization and transformation methods used by the three primary differential expression tools.

| Aspect | DESeq2 (Median of Ratios) | edgeR (TMM) | limma (voom) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Statistical Approach | Negative binomial modeling with empirical Bayes shrinkage [3] | Negative binomial modeling with flexible dispersion estimation [3] | Linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation and precision weights (voom) [3] [11] |

| Normalization Philosophy | Geometric-based scaling factor [10] | Weighted trimmed mean of log ratios [10] | Precision weights for log-transformed counts (log-cpm) [11] |

| Key Assumption | Most genes are not differentially expressed [10] | Most genes are not differentially expressed [10] | Correct mean-variance relationship is key, even if exact distribution isn't normal [11] |

| Ideal Sample Size | ≥3 replicates, performs well with more [3] | ≥2 replicates, efficient with small samples [3] | ≥3 replicates per condition [3] |

| Handling of Library Size Variation | Accounts for it via size factors. | Accounts for it via scaling factors for library sizes [10]. | voom is the clear best performer when sequencing depths are substantially different [11]. |

| Computational Efficiency | Can be intensive for large datasets [3] | Highly efficient, fast processing [3] | Very efficient, scales well with large datasets [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To objectively compare the performance of DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom, a standardized benchmarking protocol can be employed. The following methodology, drawn from experimental comparisons, provides a framework for a robust appraisal.

1. Data Acquisition and Preparation:

- Obtain publicly available RNA-seq datasets with a relatively large number of biological replicates to establish a "ground truth" [5]. Two such datasets were used in a 2021 robustness study.

- From the full datasets, create subsets with progressively reduced sample sizes (e.g., n=8, 6, 4 per group) to evaluate performance with limited replication [5].

2. Differential Expression Analysis:

- Run DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom on the full and reduced datasets, following established protocols for each tool [3] [12].

- For DESeq2: Create a

DESeqDataSetfrom the count matrix and metadata, then run theDESeq()function. Results are extracted using theresults()function with a specified false discovery rate (FDR) threshold (e.g., 5%) and fold-change threshold (e.g., 2-fold) [3]. - For edgeR: Create a

DGEListobject, normalize usingcalcNormFactors(which implements TMM), estimate dispersion withestimateDisp, and perform testing usingglmQLFTest(quasi-likelihood F-test) [3]. - For limma-voom: The

voom()function is applied to the count data to transform it and calculate weights. The output is then fed intolmFitfor linear modeling, followed byeBayesfor empirical Bayes moderation [3] [11].

3. Performance Evaluation Metrics:

- Concordance: Assess the overlap of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified by the different methods using Venn diagrams and Jaccard indices [13].

- Robustness/Sensitivity: Estimate the relative False Discovery Rate (FDR) across different library sizes. Generate a 'population' of slopes from linear regressions of relative FDRs against sequencing depth; flatter slopes indicate greater robustness [5].

Benchmarking Results and Comparative Performance

Empirical studies provide insights into how these methods perform in practice. A key finding is that while there is a core set of DEGs identified by all methods, each tool also detects a unique subset of genes, reflecting their different statistical models [13].

Reported Findings:

- Concordance: A comparative analysis showed that DESeq2 and edgeR, both based on negative binomial models, have high overlap. DESeq2 often appears less stringent, calling more DEGs, while edgeR may be more conservative. Limma-voom can be more "transversal," identifying a substantial core of common genes but also a unique set not detected by the other methods [13].

- Robustness: A 2021 study investigating robustness to sequencing alterations and sample size found that the pattern of method performance was consistent across datasets. The non-parametric method NOISeq was the most robust, followed by edgeR, voom, and then DESeq2 [5].

- Error Control: A key advantage of the limma pipelines (both voom and limma-trend) is their accurate control of the Type I error rate (false positives) even with very small sample sizes. Methods based on the negative binomial distribution can sometimes be overly liberal or conservative when sample sizes are small [11].

The diagram below visualizes the typical relationship and overlapping results from the three tools, as often revealed by a Venn diagram of their outputs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The following table details key software solutions and their functions essential for conducting differential expression analysis with DESeq2, edgeR, and limma.

| Tool / Resource | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment | The open-source software platform in which all three packages (DESeq2, edgeR, limma) are run and integrated. |

| Bioconductor Project | A repository for bioinformatics R packages, providing the installation and maintenance framework for DESeq2, edgeR, and limma. |

| DESeq2 Package | Performs differential expression analysis using the Median of Ratios normalization and negative binomial generalized linear models. |

| edgeR Package | Performs differential expression analysis using TMM normalization and negative binomial models with multiple dispersion estimation options. |

| limma Package | Provides the core linear modeling and empirical Bayes moderation framework; when combined with the voom function, it is applied to RNA-seq data. |

| VennDiagram Package | An R tool used to visualize the overlap and differences in DEG lists generated by the different methods, facilitating comparative interpretation [3]. |

The choice between TMM (edgeR), Median of Ratios (DESeq2), and voom (limma) is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific experimental context and data characteristics.

- For very small sample sizes (n=2-3), edgeR is highly efficient and specifically developed for such scenarios [3].

- For moderate to large sample sizes or data with high biological variability, DESeq2 is a strong choice, known for its robust normalization and careful control of false positives [3] [5].

- For complex experimental designs (e.g., multiple factors, time series) or when sequencing depths vary substantially, limma with voom is highly recommended. Its access to the mature limma pipeline allows for sophisticated modeling, and it provides excellent error control [3] [11].

- For maximum confidence in results, a robust strategy is to use two different methods (e.g., DESeq2 and edgeR) and focus on the intersecting set of DEGs, acknowledging that this may increase false negatives while reducing false positives [13].

In the broader thesis of benchmarking these tools, the evidence indicates that while the results from DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom are partly overlapping, each has its own strengths. The decision on which method to use should be informed by the data itself and the specific questions being asked [12].

Accurately estimating variance is a fundamental challenge in the analysis of RNA sequencing data. Unlike microarray data, RNA-seq data consists of count-based readings that exhibit over-dispersion—where variance exceeds the mean—making traditional Poisson models inadequate. The negative binomial model has emerged as the standard approach, as it incorporates a dispersion parameter to account for this extra variance. However, with typically few biological replicates in experiments, estimating gene-specific dispersion reliably becomes statistically problematic. This is where Empirical Bayes shrinkage methods play a crucial role, improving variance estimation by borrowing information across all genes to stabilize dispersion estimates.

Within the context of benchmarking differential expression tools, the approaches taken by DESeq2, edgeR, and limma to handle dispersion estimation represent a core differentiator in their performance. This guide objectively compares their methodologies, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate tool for their experimental context.

Theoretical Foundations of Variance Estimation

The Negative Binomial Model and the Dispersion Parameter

In RNA-seq data analysis, the count of reads mapped to a gene in a given sample is modeled using a negative binomial (NB) distribution. This model is characterized by a mean parameter (μ), representing expected expression, and a dispersion parameter (ϕ), which quantifies the variance relative to the mean. The relationship is defined as Variance = μ + ϕμ² [14]. The first term (μ) represents the variance from Poisson sampling error, while the second term (ϕμ²) represents the variance from biological replication [14]. A key challenge is that in studies with limited replicates, direct gene-specific dispersion estimates are highly unstable.

The Role of Empirical Bayes Shrinkage

Empirical Bayes (EB) shrinkage addresses this problem by partially pooling data across genes. Instead of estimating each gene's dispersion in isolation, the method shrinks gene-specific estimates toward a common prior or a trended value based on the mean expression [14] [15]. This approach stabilizes estimates, particularly for genes with low counts or few replicates, and balances specificity with sensitivity in differential expression detection. Shrinkage prevents false positives from dispersion underestimation and maintains power by avoiding overestimation [16] [15].

Comparative Analysis of DESeq2, edgeR, and limma

Core Methodologies and Dispersion Handling

Table 1: Core Statistical Approaches to Variance Estimation

| Tool | Core Statistical Approach | Dispersion Estimation Strategy | Shrinkage Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Negative binomial GLM with EB shrinkage | Shrinks dispersions toward a trend (mean-expression dependent) [3] | Moderate |

| edgeR | Negative binomial GLM with EB shrinkage | Offers common, trended, and tagwise dispersion; robust options for complex designs [3] | Moderate to flexible |

| limma (voom) | Linear modeling of log-CPM with precision weights | Transforms counts via voom and applies EB moderation of gene variances [3] |

Moderate |

DESeq2 utilizes a parametric curve that models dispersion as a function of the mean expression. It then shrinks gene-wise dispersion estimates toward this predicted trend. This method provides stable estimates even with minimal replicates [14].

edgeR offers a more flexible suite of options. It can estimate a common dispersion for all genes, a trended dispersion dependent on the mean, or gene-specific (tagwise) dispersions that are shrunk toward the overall trend. Its weighted conditional maximum likelihood approach allows for a tunable degree of shrinkage [15].

limma, traditionally used for microarray data, was adapted for RNA-seq through the voom transformation. The voom method converts count data into log-counts per million (log-CPM) and estimates a mean-variance relationship to calculate precision weights for each observation. Subsequently, EB moderation is applied to the gene-level variances, not the dispersions directly, making it a uniquely effective hybrid approach [3].

Performance and Benchmarking Data

Benchmarking studies consistently reveal that no single tool is universally superior; performance is highly dependent on experimental design, sample size, and the underlying biological context.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Based on Benchmarking Studies

| Performance Metric | DESeq2 | edgeR | limma (voom) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Sample Sizes (n < 5) | Good, conservative | Excellent, highly efficient [3] | Requires ≥3 replicates for powerful moderation [3] |

| Large Sample Sizes | Excellent, strong FDR control [3] | Excellent, fast processing [3] | Very efficient, scales well [3] |

| Handling Low-Count Genes | Good | Excellent, flexible dispersion estimation helps [3] | May not handle extreme over-dispersion as well [3] |

| Computational Efficiency | Can be intensive for large datasets [3] | Highly efficient, fast processing [3] | Very efficient, scales well [3] |

| Concordance with Other Tools | High agreement with edgeR and limma in real datasets [3] [17] | High agreement with DESeq2 and limma in real datasets [3] [17] | High agreement with DESeq2 and edgeR in real datasets [3] [17] |

A large-scale, multi-center benchmarking study using the Quartet and MAQC reference materials demonstrated that while inter-laboratory variations exist, there is a remarkable level of agreement in the differentially expressed genes identified by limma, edgeR, and DESeq2. This concordance strengthens confidence in results, as each tool uses distinct statistical approaches yet arrives at similar biological conclusions [17].

Another study highlighted that the choice of dispersion estimation method directly impacts the power and error rate of differential expression tests. Methods employing a moderate degree of shrinkage, such as those in edgeR and DESeq2, were found to maximize test performance, striking an optimal balance between false discoveries and detection power [15].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Typical Differential Expression Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for a differential expression analysis, highlighting the key steps where variance estimation occurs.

Detailed Protocols for Key Experiments

Objective: To assess the accuracy and reproducibility of DEG detection by different tools using samples with known "ground truth."

Materials: Quartet reference materials (samples with small biological differences) and MAQC reference materials (samples with large biological differences), spiked-in ERCC RNA controls.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation and Sequencing: Distribute reference materials to multiple participating laboratories. Each laboratory prepares libraries using their in-house protocols and sequences them on their chosen platform.

- Data Processing: Obtain raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files) from all laboratories.

- Quality Assessment: Use metrics like Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to gauge data quality and the ability to distinguish biological signals from technical noise.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Process the high-quality data through fixed and tool-specific pipelines (DESeq2, edgeR, limma-voom) to identify DEGs between sample groups.

- Performance Evaluation:

- Accuracy: Compare the list of DEGs generated by each tool to the established reference datasets and built-in truths (e.g., ERCC spike-in ratios, known sample mixing ratios).

- Reproducibility: Assess the consistency of DEG lists across different laboratories and pipelines.

Objective: To evaluate the impact of different dispersion estimation methods on the performance of tests for differential expression.

Methodology:

- Parameter Estimation from Real Data: Use a large, well-replicated RNA-seq dataset (e.g., the Cheung data with 41 individuals [14]) to estimate realistic gene-specific mean expressions and dispersions.

- Data Simulation: Generate pseudo-datasets by drawing counts from a negative binomial distribution using the parameters obtained in the previous step. The simulation should include a set of genes that are truly differentially expressed between two groups and a set that is not.

- Dispersion Estimation and Testing: Apply multiple dispersion estimation methods (e.g., DESeq2's and edgeR's EB methods, simple gene-wise MLE) to the simulated data. Then, perform differential expression testing using the respective dispersions.

- Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Calculate the False Discovery Rate (FDR) and the True Positive Rate (TPR) for each method.

- Plot Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves to visualize the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Variance Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Biological Sample | Provide "ground truth" for benchmarking | Enables empirical assessment of tool accuracy using samples like Quartet and MAQC [17]. |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Synthetic RNA | Act as internal controls with known concentrations | Allows for accuracy assessment of absolute gene expression and variance modeling [17]. |

| FastQC | Software | Quality control of raw sequencing reads | Identifies sequencing artifacts and biases that can contribute to unwanted variance [18]. |

| Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) | Algorithm | Normalizes for library composition differences | Corrects for compositional biases across samples, a prerequisite for accurate dispersion estimation [3] [18]. |

| DESeq2 | R/Bioconductor Package | Differential expression analysis | Implements trend-based EB shrinkage for dispersion parameters [3]. |

| edgeR | R/Bioconductor Package | Differential expression analysis | Offers flexible EB shrinkage for dispersion (common, trended, tagwise) [3] [15]. |

| limma-voom | R/Bioconductor Package | Differential expression analysis | Applies EB moderation to gene variances after a count data transformation [3]. |

The handling of variance through Empirical Bayes shrinkage is a sophisticated statistical solution to a fundamental problem in RNA-seq analysis. DESeq2, edgeR, and limma-voom have all integrated this principle into their cores, albeit through different technical implementations.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice of tool should be guided by the specific experimental context:

- For studies with very small sample sizes (n=2-5), edgeR is often the most powerful and efficient choice.

- For analyses requiring complex experimental designs or integration with other omics data types, limma-voom provides exceptional flexibility and performance, provided there are at least three replicates.

- For general use with moderate to large sample sizes, and when strong false discovery rate control is a priority, DESeq2 is an excellent and robust option.

Ultimately, the high concordance often observed between these tools in well-controlled experiments is a testament to the maturity and effectiveness of the EB shrinkage framework. Adhering to best practices in experimental design, normalization, and quality control remains just as critical as the choice of software for achieving reliable biological insights.

Ideal Use Cases and Sample Size Requirements for Each Tool

Differential expression (DE) analysis represents a fundamental step in understanding how genes respond to different biological conditions using RNA sequencing data. When researchers perform RNA sequencing, they essentially take a snapshot of all genes expressed in samples at a given moment, but the real biological insights come from understanding how these expression patterns change between conditions, time points, or disease states. The power of DE analysis lies in its ability to identify these changes systematically across thousands of genes simultaneously while accounting for biological variability and technical noise inherent in RNA-seq experiments [3].

Several sophisticated tools have been developed for DE analysis, each addressing specific challenges in RNA-seq data, including count data overdispersion, small sample sizes, complex experimental designs, and varying levels of biological and technical noise. Among these, DESeq2, edgeR, and limma have emerged as three of the most widely-used and robust methods. DESeq2 and edgeR share a common foundation in negative binomial modeling, while limma utilizes linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation on transformed count data [3] [19]. Understanding their unique approaches, optimal use cases, and sample size requirements helps researchers select the most appropriate tool for specific research questions and experimental designs.

This guide provides an objective comparison of these three popular differential expression analysis tools, focusing on their ideal use cases and sample size requirements based on current literature and benchmarking studies. We present comparative performance data, detailed methodological protocols, and practical recommendations to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their analytical decisions.

Statistical Foundations and Methodological Comparisons

Core Statistical Approaches

Each differential expression tool employs distinct statistical frameworks tailored to handle the characteristics of RNA-seq count data:

DESeq2 utilizes negative binomial modeling with empirical Bayes shrinkage for both dispersion and fold change estimates. This approach improves stability and interpretability of estimates, enabling a more quantitative analysis focused on the strength rather than the mere presence of differential expression. DESeq2 incorporates internal normalization based on geometric means and adaptive shrinkage for dispersion estimates and fold changes [20] [3].

edgeR employs negative binomial modeling with flexible dispersion estimation options. It offers multiple testing strategies, including quasi-likelihood options and fast exact tests. edgeR typically uses TMM (trimmed mean of M-values) normalization by default and provides flexible options for common, trended, or tagged dispersion estimation [3] [21].

limma applies linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation to log-transformed count data. For RNA-seq analysis, limma uses the voom transformation that converts counts to log-CPM (counts per million) values and estimates the mean-variance relationship to generate precision weights. These weights are incorporated into the linear modeling process, allowing the same empirical Bayes moderation framework developed for microarrays to be applied to RNA-seq data [19] [3].

Key Technical Components

Table 1: Core Components of Each Differential Expression Tool

| Component | DESeq2 | edgeR | limma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normalization | Median-of-ratios method | TMM normalization by default | voom transformation to log-CPM |

| Dispersion Estimation | Empirical Bayes shrinkage | Flexible dispersion options | Precision weights from mean-variance trend |

| Statistical Testing | Wald test or LRT | Exact test or GLM/QLF | Empirical Bayes moderated t-tests |

| Handling of Small Samples | Information sharing across genes | Empirical Bayes moderation | Information borrowing through variance shrinkage |

| Fold Change Estimation | Shrunken log2 fold changes | Raw or moderated estimates | Model-based coefficients |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Comparative workflows for DESeq2, edgeR, and limma showing distinct analytical approaches with shared input and output stages.

Sample Size Requirements and Performance

Minimum Sample Size Recommendations

Sample size substantially impacts the performance and reliability of differential expression analysis. Based on comprehensive benchmarking studies:

DESeq2 typically requires at least 3 replicates per condition for reliable results, though it performs better with moderate to large sample sizes (≥6 per group) [3] [22]. With very small sample sizes (n=3), DESeq2 may show slightly conservative behavior, but its performance improves markedly as sample size increases.

edgeR functions efficiently with very small sample sizes, technically working with as few as 2 replicates per condition, though ≥3 replicates are recommended for more reliable results [3] [21]. edgeR demonstrates particular strength when analyzing genes with low expression counts, where its flexible dispersion estimation better captures inherent variability in sparse count data.

limma with voom transformation requires at least 3 biological replicates per condition to reliably estimate the mean-variance relationship [3] [23]. The empirical Bayes moderation in limma effectively borrows information between genes to overcome the problem of small sample sizes, but this approach still requires sufficient data points to estimate variance reliably.

Performance Across Sample Sizes

Table 2: Performance Characteristics by Sample Size Based on Benchmarking Studies

| Sample Size (per group) | DESeq2 | edgeR | limma |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2-3 | Moderate power, conservative FDR control | Good power, reasonable FDR control | Requires n≥3, good FDR control with sufficient replicates |

| n = 6 | Good power, well-controlled FDR | Good power, well-controlled FDR | Good power, well-controlled FDR |

| n = 12+ | High power, stable results | High power, stable results | High power, stable results |

| Large populations (n>50) | FDR inflation concerns in population studies [24] | FDR inflation concerns in population studies [24] | Maintains better FDR control in large samples [24] |

Recent evaluations indicate that for RNA-seq count data with negative binomial distribution, EBSeq (not covered in this guide) performed better than other methods when sample size was as small as 3 in each group, while DESeq2 performed slightly better than other methods when sample sizes increased to 6 or 12 in each group [22]. All methods show improved performance when sample size increases to 12 per group.

Impact of Sample Size on Detection Power

Diagram 2: Relationship between sample size and methodological performance showing how optimal tool selection changes with experimental scale.

Extensive benchmark studies have provided valuable insights into the relative strengths of these tools with varying sample sizes. Research has demonstrated that increasing sample size is more effective for increasing statistical power than increasing sequencing depth, especially when sequencing depth already reaches 20 million reads [25]. This highlights the importance of adequate biological replication rather than excessive sequencing depth in experimental design.

Ideal Use Cases and Application Scenarios

Optimal Applications for Each Tool

Each differential expression method has particular strengths that make it ideally suited for specific research scenarios:

DESeq2 excels in experiments with moderate to large sample sizes and high biological variability. Its robust approach provides strong false discovery rate control and handles subtle expression changes effectively. DESeq2 is particularly valuable when researchers need stable, interpretable fold change estimates through its shrinkage approach [20] [3]. The automatic outlier detection and independent filtering features make it suitable for analyses requiring minimal manual intervention.

edgeR performs optimally with very small sample sizes and in studies focusing on low-abundance transcripts. Its efficient processing makes it suitable for large datasets, and it offers flexibility in handling technical replicates [3] [21]. edgeR provides multiple testing strategies (exact tests, quasi-likelihood F-tests) that can be selected based on experimental design, giving experienced users more analytical options.

limma demonstrates remarkable versatility and robustness across diverse experimental conditions, particularly excelling in handling complex designs and outliers. Its computational efficiency becomes especially valuable when processing large-scale datasets containing thousands of samples [3] [19]. limma integrates well with other omics data types and maintains consistent performance in population-level studies with large sample sizes where other methods may show FDR inflation [24].

Performance in Specific Research Contexts

Table 3: Recommended Tools by Research Scenario

| Research Scenario | Recommended Tool | Rationale | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small pilot studies (n=2-3) | edgeR | Designed for small samples, efficient with minimal replicates | Consider non-parametric methods if distribution assumptions are violated |

| Complex multi-factor designs | limma | Handles complex designs elegantly, flexible model specification | voom transformation must be carefully quality checked |

| Population-level studies (n>50) | limma or non-parametric methods | Maintains FDR control where DESeq2/edgeR may inflate false positives | Wilcoxon rank-sum test recommended for large population studies [24] |

| Studies focusing on low-count genes | edgeR | Better captures variability in sparse count data | Flexible dispersion estimation beneficial for low-expression features |

| Time-series experiments | limma | Handles correlated measurements and complex time dependencies | Linear modeling framework naturally accommodates time series |

| Experiments requiring stable fold changes | DESeq2 | Shrunken fold changes improve interpretability | More conservative for low-count genes |

Specialized Applications and Limitations

limma demonstrates particular strength in multi-factorial experimental designs where researchers need to account for multiple batch effects or covariates. Its linear modeling framework naturally accommodates complex experimental structures that are common in clinical studies or integrated omics analyses [19]. However, limma may not handle extreme overdispersion as effectively as the negative binomial-based methods and requires careful quality control of the voom transformation.

DESeq2 and edgeR share many performance characteristics given their common foundation in negative binomial modeling. Both perform well in benchmark studies using real experimental data and simulated datasets where true differential expression is known [3] [22]. However, recent research has raised concerns about FDR control for both DESeq2 and edgeR in large-sample population studies, where actual false discovery rates sometimes exceeded 20% when the target FDR was 5% [24].

edgeR offers both exact tests and generalized linear model approaches, providing flexibility for different experimental designs. The quasi-likelihood approach in edgeR is particularly useful for data with complex mean-variance relationships or for experiments with multiple factors [21]. However, edgeR requires more careful parameter tuning compared to other methods, and its common dispersion approach may sometimes miss gene-specific patterns.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Data

Standardized Analysis Workflow

To ensure fair comparisons between methods, researchers should follow standardized processing workflows:

Data Preprocessing Protocol:

- Start with a raw count matrix filtered to remove low-expressed genes (typically keeping genes with counts >10 in at least 80% of samples per group)

- Create a metadata data frame with sample information and experimental conditions

- For each method, follow package-specific object creation:

- DESeq2:

DESeqDataSetFromMatrix()with appropriate design formula - edgeR:

DGEList()followed bycalcNormFactors() - limma:

voom()transformation on DGEList object

- DESeq2:

Differential Expression Analysis:

- DESeq2 protocol: Run

DESeq()function on DESeqDataSet object, then extract results usingresults()with independent filtering enabled - edgeR protocol: Estimate dispersions using

estimateDisp(), then conduct testing with eitherexactTest()orglmQLFTest()for complex designs - limma protocol: Apply

voom()transformation, then fit linear model withlmFit(), followed by empirical Bayes moderation witheBayes()

Results Extraction:

- Extract significantly differentially expressed genes using adjusted p-value threshold (typically FDR < 0.05)

- Apply optional fold change threshold if biological significance is a consideration

- Compare results across methods using Venn diagrams or overlap analysis

Benchmarking Methodologies

Comprehensive evaluations of differential expression tools typically employ multiple approaches:

Simulation Studies: Generate count data with known differentially expressed genes using parameters estimated from real datasets. This approach allows precise calculation of false discovery rates and statistical power [25] [22]. The polyester R package provides a widely-used framework for such simulations.

Permutation Analysis: In large-sample studies, randomly permute condition labels to create negative control datasets where no true differential expression should exist. This approach enables empirical FDR estimation without relying on model assumptions [24].

Semi-Synthetic Data: Spike in known differentially expressed genes into real experimental data to create benchmarks with authentic background characteristics while maintaining knowledge of true positives.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Differential Expression Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Differential expression analysis using negative binomial distribution | Primary DE analysis for moderate to large datasets |

| edgeR | Differential expression analysis with robust small-sample performance | DE analysis with limited replicates or for low-count genes |

| limma with voom | Differential expression using linear models on transformed counts | Complex experimental designs or large-sample studies |

| sva/biocParallel | Batch effect correction and parallel processing | Handling technical covariates and improving computational efficiency |

| tximport/tximeta | Transcript-level import and summarization | Preparing count data from transcript-level quantifications |

| IGV/UCSC Genome Browser | Visualization of expression patterns in genomic context | Exploratory analysis and result validation |

Based on comprehensive benchmarking studies and methodological evaluations:

For studies with very small sample sizes (n=2-3 per group), edgeR is generally recommended due to its efficient handling of minimal replicates and good performance with low-count genes. EBSeq also shows excellent performance with small sample sizes but was not the focus of this comparison.

For standard experiments with moderate sample sizes (n=6-12 per group), DESeq2 performs slightly better than other methods in terms of FDR control and power when data follow the negative binomial distribution.

For complex experimental designs or large-scale population studies (n>50), limma with voom transformation maintains better FDR control compared to DESeq2 and edgeR, which may show inflated false discovery rates in these contexts. For very large population studies, non-parametric methods like the Wilcoxon rank-sum test may be most appropriate.

For maximum reliability, many benchmarking studies recommend using multiple methods and focusing on genes identified consistently across pipelines. This consensus approach helps mitigate method-specific biases and provides more robust biological insights.

Tool selection should also consider the biological context, distribution characteristics of the data, and analytical requirements beyond simple two-group comparisons. As sequencing technologies evolve and sample sizes continue to grow in many research domains, understanding these methodological tradeoffs becomes increasingly important for generating valid, reproducible results in transcriptomics research.

From Counts to Insights: Step-by-Step Analysis Workflows

Within the broader objective of benchmarking differential expression tools like DESeq2, edgeR, and limma, the critical importance of data preparation and quality control cannot be overstated. The accuracy of all downstream statistical comparisons is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the input read count data. This guide objectively compares three foundational tools—FastQC, Trimmomatic, and Salmon—that constitute essential stages in a robust RNA-seq preprocessing workflow, synthesizing performance data from recent large-scale pipeline evaluations to inform optimal software selection.

Tool-Specific Analysis and Performance

FastQC: Raw Read Quality Assessment

FastQC is the universal standard for initial quality control of raw sequence data, providing a comprehensive profile of potential issues prior to any downstream processing [26].

- Function: Provides an initial quality check on raw sequence data from high-throughput sequencing pipelines, generating a holistic view of potential problems [26].

- Key Metrics: Assesses per-base sequence quality, sequence length distribution, GC content, sequence duplication levels, overrepresented sequences, and adapter contamination [27] [26].

- Performance Note: While FastQC applies stringent criteria that may frequently generate "warnings" or "failures," these results require careful biological interpretation and are not necessarily a death sentence for the dataset [26].

Trimmomatic: Read Trimming and Filtering

Trimmomatic performs adapter removal and quality trimming to enhance downstream mapping rates and quantification accuracy. Systematic comparisons highlight its utility in standardized workflows.

- Function: A flexible, precise tool for removing adapter sequences and low-quality bases from sequencing reads [28] [26].

- Core Methodology: Employs a pipeline-based approach where each processing step (e.g., adapter removal, quality trimming) is applied sequentially. For paired-end data, it ensures both reads are processed simultaneously to maintain pair integrity [26].

- Typical Parameters: Includes sliding window trimming (e.g., 4-base window, average quality threshold of 15-20) and minimum read length enforcement (e.g., 20-36 bases) [28].

- Performance Context: While a benchmark noted Trimmomatic's "complex parameter setup" and lack of speed advantage compared to some alternatives [7], it remains widely implemented in major community-endorsed pipelines such as nf-core/rnaseq [29].

Salmon: Transcript Quantification

Salmon represents a paradigm shift in RNA-seq quantification, using fast, alignment-free algorithms to estimate transcript abundances.

- Function: Performs "wicked-fast" transcript quantification from RNA-seq data using a pseudoalignment approach, bypassing traditional base-by-base alignment to a reference genome [29].

- Core Methodology: Leverages k-mer matching and a complex statistical model to quantify the likelihood of reads originating from specific transcripts, incorporating considerations for GC content bias, sequence bias, and positional bias [27] [29].

- Key Advantage: Speed and efficiency without significant sacrifice in accuracy; recent benchmarks often classify Salmon as a top-performing quantification tool [27].

- Workflow Integration: In integrated pipelines like nf-core/rnaseq, Salmon can operate either on raw reads (with alignment information optionally generated for QC) or on reads pre-filtered by alignment tools like STAR [29].

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes key experimental findings from comprehensive pipeline comparisons.

Table 1: Experimental Performance Comparison of RNA-seq Tools

| Tool | Performance Metric | Experimental Finding | Benchmark Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trimmomatic | Operational Complexity | Parameter setup is complex with no speed advantage [7]. | Comparison of 288 pipelines for fungal RNA-seq data [7]. |

| fastp | Quality Improvement | Significantly enhanced processed data quality (1-6% Q20/Q30 base improvement) [7]. | Alternative trimmer showing superior speed and integrated reporting [7] [29]. |

| Salmon | Quantification Accuracy | Classified as a high-accuracy, fast tool for transcript quantification [27]. | Part of a benchmark studying 192 alternative methodological pipelines [28]. |

| STAR + Salmon | Workflow Integration | Default alignment/quantification combination in nf-core/rnaseq pipeline [29]. | Community-standard workflow for comprehensive analysis [29]. |

Integrated Workflow and Best Practices

The synergy between quality control, read trimming, and quantification creates a foundational preprocessing pipeline that directly influences the reliability of differential expression results with DESeq2, edgeR, or limma.

Standardized Workflow

A typical integrated workflow proceeds through well-defined stages [26]:

- Raw Read QC: FastQC on untrimmed FASTQ files.

- Read Trimming: Trimmomatic or fastp performs adapter and quality trimming.

- QC Validation: FastQC is re-run on trimmed reads to confirm quality improvements.

- Quantification: Salmon performs transcript-level quantification (optionally with STAR alignment for QC).

- Gene-Level Summarization: Tximport converts transcript abundances to gene-level counts for DESeq2/edgeR.

This process is encapsulated in the following workflow diagram:

Experimental Protocols from Benchmarking Studies

Large-scale evaluations provide validated methodologies for tool assessment:

- Comprehensive Pipeline Comparison (2024): Researchers analyzed 288 distinct pipelines on five fungal RNA-seq datasets. Performance was evaluated based on simulated data, establishing a standardized approach for objectively assessing the accuracy of differential gene expression results produced by different tool combinations [7].

- Systematic Tool Assessment (2020): A study applied 192 alternative methodological pipelines to 18 human cell line samples. Gene expression signals were quantified using non-parametric statistics to measure precision and accuracy, and pipeline performance was validated against qRT-PCR measurements on the same samples [28].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs key computational tools and resources required for implementing the described RNA-seq preprocessing workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function in Workflow | Specific Application |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Initial and post-trimming quality control | Generates quality metrics for raw and processed reads [27] [26]. |

| Trimmomatic | Adapter and quality trimming | Preprocessing of single-end and paired-end reads [28] [26]. |

| Salmon | Transcript-level quantification | Fast, alignment-free quantification of gene expression [27] [29]. |

| STAR | Splice-aware genome alignment | Optional alignment for QC or for use in alignment-based pipelines [29]. |

| MultiQC | Aggregate QC reporting | Summarizes results from multiple tools and samples into a single report [29]. |

| Reference Transcriptome | Sequence and annotation reference | FASTA file of known transcripts required for Salmon quantification [29]. |

The selection of preprocessing tools is a critical, non-trivial decision that directly impacts the validity of downstream differential expression analysis. Evidence from large-scale benchmarks indicates that while Trimmomatic is a robust and widely adopted trimming tool, faster and simpler alternatives like fastp can offer comparable or superior performance in certain contexts. Salmon consistently demonstrates high accuracy and exceptional speed for quantification. Integrating these tools into a standardized workflow, with rigorous quality control checkpoints using FastQC, establishes a reliable foundation for a meaningful benchmarking study of differential expression tools such as DESeq2, edgeR, and limma.

For researchers embarking on a benchmarking study to compare differential expression (DE) tools like DESeq2, edgeR, and limma, a properly configured R environment is the critical first step. This guide provides the essential code and methodologies to install and load the necessary packages, ensuring a reproducible and robust foundation for your analysis.

Package Installation and Management

An efficient R environment setup involves correctly installing packages and managing their dependencies. The following sections detail the primary methods.

Installing from Official Repositories

Most R packages are hosted on the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) or Bioconductor. The install.packages() function is the standard workhorse for CRAN packages [30] [31].

To install a single package, use:

For a benchmarking study, you will need multiple packages. Install them simultaneously using a character vector for greater efficiency [30] [31]:

Since DESeq2 and edgeR are Bioconductor packages, they require a different installer [3]:

Advanced Installation Methods

For a more modern and streamlined installation process that automatically handles dependencies, consider the pak package [30]:

Alternatively, the pacman package offers an efficient way to install and load packages in a single step [31]:

Loading Packages into Your R Session

After installation, packages must be loaded into your R session to make their functions available. Use the library() function for this purpose [30] [32].

Remember: A package needs to be installed only once, but it must be loaded with library() at the beginning of every new R session where you intend to use it [30].

Experimental Setup for Tool Benchmarking

A rigorous benchmark of DE tools requires a standardized experimental protocol. The following workflow outlines the key stages, from data preparation to performance assessment.

Data Preparation and Quality Control

The initial phase involves preparing a high-quality count matrix for downstream analysis [3].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Software Tools for RNA-seq Differential Expression Benchmarking

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Statistical Foundation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 | Bioconductor Package | DE analysis for RNA-seq data | Negative binomial model with empirical Bayes shrinkage [3] |

| edgeR | Bioconductor Package | DE analysis for RNA-seq data | Negative binomial model with flexible dispersion estimation [3] |

| limma | Bioconductor Package | DE analysis for various data types | Linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation on voom-transformed counts [3] |

| performance | CRAN Package | Model performance assessment and comparison | Computes R², AIC, BIC, RMSE, ICC, and other indices [33] |

| FastQC | External Tool | Quality control of raw sequencing reads | Provides quality metrics and visualizations [18] |

| Salmon | External Tool | Transcript quantification from RNA-seq data | Lightweight, alignment-free quantification [18] |

Statistical Foundations of Differential Expression Tools

Understanding the core statistical approaches of each DE tool is crucial for interpreting benchmarking results.

Performance Assessment Methodology

The performance package provides a unified framework for evaluating and comparing statistical models, which is essential for benchmarking DE tools [33].

Computing Model Performance Indices

After running differential expression analyses with each tool, extract results and compute performance metrics.

Key Performance Metrics for DE Tools

The r2(), icc(), and model_performance() functions from the performance package calculate crucial indices for model assessment [33].

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Differential Expression Tool Evaluation

| Performance Metric | Interpretation | Relevance to DE Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| R-squared (R²) | Proportion of variance explained by the model | Indicates how well the model explains expression variability [33] |

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | Relative model quality considering complexity | Useful for model selection; lower values indicate better fit [34] |

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | Similar to AIC with stronger penalty for complexity | Prefers simpler models; lower values better [34] |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | Measure of prediction error | Assesses model accuracy in predicting expression [33] |

| Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | Measure of reliability or agreement | Quantifies consistency in repeated measurements [33] |

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) | Proportion of false positives among significant results | Critical for multiple testing correction in DE analysis [21] |

Comparative Analysis of Differential Expression Tools

Benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated the performance of DE tools across various experimental conditions.

Tool Performance Across Experimental Conditions

Table 3: Comparative Performance of DESeq2, edgeR, and limma Based on Benchmarking Studies

| Performance Aspect | DESeq2 | edgeR | limma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal Sample Size | ≥3 replicates, performs well with more [3] | ≥2 replicates, efficient with small samples [3] | ≥3 replicates per condition [3] |

| Handling of Low-Count Genes | Good, with independent filtering | Excellent, flexible dispersion estimation [3] | Moderate, depends on voom transformation |

| Biological Variability Handling | Excellent with empirical Bayes shrinkage [3] | Good with multiple dispersion options [3] | Good with precision weights [3] |

| Computational Efficiency | Can be intensive for large datasets [3] | Highly efficient, fast processing [3] | Very efficient, scales well [3] |

| Complex Experimental Designs | Good | Good | Excellent, handles multi-factor designs elegantly [3] |

| False Discovery Rate Control | Strong, conservative fold change estimates [3] | Good, with multiple testing strategies [3] | Good, with empirical Bayes moderation [3] |

Practical Implementation of DE Tools

The following code demonstrates how to run each DE tool using the same filtered count data, enabling fair comparisons.

The selection of an appropriate differential expression tool depends on your specific experimental context. DESeq2 and edgeR, sharing a foundation in negative binomial modeling, generally show comparable performance in benchmarks, with edgeR having a slight advantage for low-count genes [3]. Limma, with its voom transformation, excels in complex experimental designs and demonstrates remarkable computational efficiency for large datasets [3].

For comprehensive benchmarking, ensure consistent data preprocessing across all tools and utilize the performance package to calculate standardized metrics. This approach facilitates objective comparisons and strengthens the conclusions of your research on differential expression analysis methods.

Differential expression (DE) analysis is a fundamental step in RNA-sequencing studies, enabling researchers to identify genes whose expression changes significantly between different biological conditions. Among the numerous methods developed for this purpose, DESeq2, edgeR, and limma have emerged as three of the most widely used and cited tools [35]. Each employs distinct statistical approaches to handle the challenges inherent to RNA-seq data, including overdispersion, varying library sizes, and small sample sizes.

DESeq2 and edgeR both model count data using a negative binomial distribution to account for overdispersion, but they differ in their normalization and parameter estimation strategies [3]. In contrast, limma (when used with its voom transformation) applies linear modeling to continuous log-counts-per-million values, using precision weights to account for heteroscedasticity and empirical Bayes methods to stabilize variance estimates across genes [3] [36]. Understanding these foundational statistical approaches is crucial for selecting the appropriate tool for a given experimental context and correctly interpreting the results.

Tool Comparison: Statistical Approaches and Performance Characteristics

Core Methodologies and Normalization Strategies

Table 1: Core Statistical Foundations of DESeq2, edgeR, and limma

| Aspect | DESeq2 | edgeR | limma (with voom) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Statistical Approach | Negative binomial modeling with empirical Bayes shrinkage | Negative binomial modeling with flexible dispersion estimation | Linear modeling with empirical Bayes moderation of log-CPM values |

| Data Transformation | Internal normalization based on geometric mean | TMM normalization by default | voom transformation converts counts to log-CPM values |

| Variance Handling | Adaptive shrinkage for dispersion estimates and fold changes | Flexible options for common, trended, or tagged dispersion | Empirical Bayes moderation improves variance estimates for small sample sizes |

| Key Components | Normalization, dispersion estimation, GLM fitting, hypothesis testing | Normalization, dispersion modeling, GLM/QLF testing, exact testing option | voom transformation, linear modeling, empirical Bayes moderation, precision weights |

DESeq2 employs a normalization technique based on the geometric mean, calculating a "median of ratios" between samples to account for differences in sequencing depth and RNA composition [35]. edgeR typically uses the Trimmed Mean of M-values method, which assumes most genes are not differentially expressed and scales library sizes accordingly [35]. Limma, when processing RNA-seq data, first transforms count data to log2-counts per million using the voom function, which also computes precision weights for each observation to account for the mean-variance relationship in the data [3] [36].

Performance Characteristics and Ideal Use Cases

Table 2: Performance Comparison and Recommended Use Cases

| Characteristic | DESeq2 | edgeR | limma (with voom) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal Sample Size | ≥3 replicates, performs well with more | ≥2 replicates, efficient with small samples | ≥3 replicates per condition |

| Best Use Cases | Moderate to large sample sizes, high biological variability, subtle expression changes, strong FDR control | Very small sample sizes, large datasets, technical replicates, flexible modeling needs | Small sample sizes, multi-factor experiments, time-series data, integration with other omics |

| Computational Efficiency | Can be computationally intensive for large datasets | Highly efficient, fast processing | Very efficient, scales well |